Abstract

We report a rare case of lung adenocarcinoma in a 54-year-old man, in whom osteoclast-like giant cells (OCGCs) were found only in metastases. Autopsy revealed that metastases involving the tongue, gallbladder, stomach, intestines, right adrenal gland, and bones contained numerous OCGCs. Some metastases to the lungs and liver also contained OCGCs, but the primary tumor and metastases to the right atrium, spleen, left adrenal gland, and lymph nodes did not. Primary lung carcinoma cells were positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), and Napsin A, but were negative for vimentin and CD68. Frequently poorly cohesive metastatic carcinoma cells admixtured with OCGCs showed weak CK7/EMA positivity, no TTF-1/Napsin A staining, and newly expressed vimentin. OCGCs were positive only for CD68 and vimentin, implying reactive cells. OCGCs can develop only in metastatic lesions, possibly associated with their anaplastic changes or epithelial mesenchymal transition.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, immunohistochemistry, lung carcinoma, metastasis, osteoclast-like giant cells

Introduction

Lung carcinoma containing osteoclast-like giant cells (OCGCs) is a rare neoplasm. There are only eight previously reported cases,1–6 and the clinicopathological characteristics remain unclear. This tumor should be distinguished from giant cell carcinoma with multinucleated tumor cells of an epithelial nature, also called pleomorphic carcinoma,6,7 and a true giant cell tumor without epithelial differentiation as a counterpart to giant cell tumor of the bone.8 Recently, we encountered an autopsy case of lung carcinoma in which OCGCs were detected only in its metastases. We herein described the clinicopathological features of this case.

Case report

A 54-year-old man presented with rib metastasis-related left chest pain. Imaging examination revealed a right lung tumor and other multiple bone metastases. He underwent only radiotherapy for bone metastases and died of the disease eight months after onset.

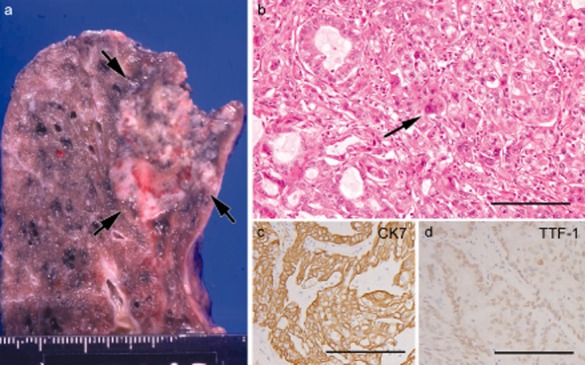

Autopsy revealed a 3.2 cm primary lung tumor in the right upper lobe (Fig 1a) and its generalized metastases. The primary tumor was chiefly composed of nested polygonal cells with faintly eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm containing mucin, consistent with adenocarcinoma of solid predominant with mucin production type (Fig 1b).9 Multinucleated bizarre cells (Fig 1b, arrow) were occasionally found, but OCGCs were not detected. Metastases consisted of polygonal or rounded carcinoma cells, closely resembling primary lung cancer. Moreover, metastases involving the tongue, stomach, small intestine, rectum, liver, gallbladder, right adrenal gland, and bones (sternum, thoracic vertebrae, and left seventh rib) were commonly hemorrhagic, and were accompanied by numerous OCGCs. OCGCs tended to be present centrally in the nodules (Fig 2a) and/or near the hemorrhages. Metastatic carcinoma cells adjacent to OCGCs were frequently poorly cohesive (Fig 2b), and the isolated cells were infrequently phagocytized by giant cells (Fig 2c). Some of the lung and liver metastases contained OCGCs. However, metastases to the right atrium, spleen, left adrenal gland, and lymph nodes (mediastinum, paraaorta, and mesentery) were not hemorrhagic and did not have OCGCs.

Figure 1.

Primary lung carcinoma. (a) Gross features of primary lung cancer in the right upper lobe. (b) Nested adenocarcinoma cells with focal acinar structure, occasionally containing multinucleated carcinoma cell (arrow) (bar = 100 μm). (c and d) Carcinoma cells diffusely and strongly positive for cytokeratin 7 (c) and focally positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (d) (c and d, bars = 100 μm)

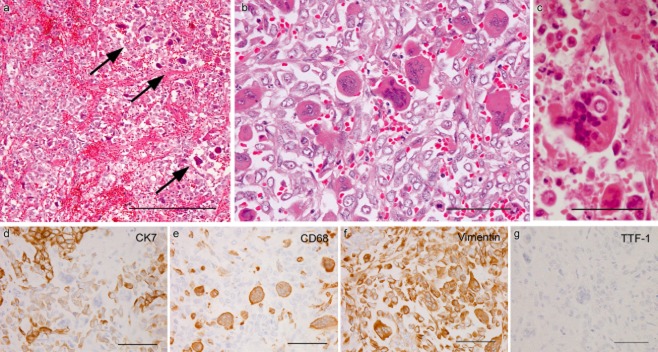

Figure 2.

Metastases containing osteoclast-like giant cells (OCGCs). (a) OCGCs chiefly distributed in the central portion (arrows) of gastric metastasis (bar = 200 μm). (b) Poorly cohesive carcinoma cells intermingled with numerous OCGCs in gallbladder metastasis (bar = 50 μm). (c) Giant cell phagocytizing an isolated carcinoma cell in rectal metastasis (bar = 50 μm). (d–g) Immunohistochemical findings in the same area of a small intestinal metastasis. Cytokeratin 7 (CK7) expression is strong in nested carcinoma cells, but weak in poorly cohesive carcinoma cells admixtured with CK7-negative OCGCs (d). CD68 staining only in OCGCs and a few histiocytes (e). Vimentin expression in OCGCs and many isolated carcinoma cells (f). No expression of thyroid transcription factor 1 in metastatic lesion (G) (d–g, bars = 50 μm)

Primary lung cancer cells were diffusely positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7; OV-TL 12/30; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) (Fig 1c), and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA; E29; Nichirei Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), focally positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1; SPT24; Novocastra, Newcastle, UK) (Fig 1d) and Napsin A (IP64; Novocastra), but negative for the beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG; C6405; Nichirei), vimentin (V9; Nichirei), and CD68 (PG-M1; Nichirei). Metastatic carcinoma cells were positive for CK7 and EMA, but were negative for TTF-1 (Fig 2g), Napsin A, β-hCG, and CD68. Metastatic carcinoma cells admixtured with OCGCs were often poorly cohesive and showed weak expression for CK7 (Fig 2d) and EMA, and expression for vimentin (Fig 2f). OCGCs were positive for CD68 and vimentin (Fig 2e, f), but negative for other antibodies.

Discussion

In the current case, the primary lung adenocarcinoma did not contain OCGCs. However, many generalized nodules containing OCGCs also had CK7/EMA-positive adenocarcinomatous components resembling a lung tumor. No other primary tumor with OCGCs was found. These features suggested that these nodules were metastases from lung carcinoma, and excluded a diagnosis of a true giant cell tumor.8 OCGCs were positive only for CD68 and vimentin, implying reactive cells. We concluded that OCGCs can develop only in metastases. To our knowledge, no similar cases have been reported, although Love et al.2 found that OCGCs were more numerous in metastases than in primary lung carcinoma.

The main clinicopathological features of eight reported cases of primary lung carcinoma with OCGCs are summarized in Table 1.1–6 In three cases, the histiocytic natures of multinucleated giant cells were not confirmed immunohistochemically, but they showed distinct benign-looking features, closely resembling osteoclasts. Three patients with anaplastic carcinoma, described as sarcomatoid, undifferentiated, or large cell carcinoma, and one with squamous cell carcinoma died of disease within 19 months after surgery, while two with squamous cell carcinoma and one with adenocarcinoma were alive 15–60 months after the surgery.1–5 Hence, the prognosis appeared to depend on the histology of the lung carcinoma, rather than the presence of OCGCs. In our case, the aggressive course was influenced by widespread metastases of adenocarcinoma. Therefore, we consider that the presence of OCGCs in lung carcinoma is not a prognostic factor.

Table 1.

Main clinicopathological findings of previously reported cases of primary lung carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells

| Case No. | Age/Gender | Location | Size (cm) | Histology of main lung carcinoma | Immunohistochemistry of osteoclast-like giant cells | Metastasis of lung carcinoma | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Autopsy | |||||||

| 11 | 57/M | RLL | 4.5 | Squamous cell carcinoma | Not done | None | – | 5 years, ANED |

| 22 | 60/M | RLL | 3 | Squamous cell carcinoma | Lyso- | – | Present§ | 7 days, DOD |

| 33 | 60/F | RLL | 9 | Undifferentiated carcinoma† | Not done | None | Present§ | 75 days, DOD |

| 44 | 61/M | LUL | 6 | Squamous cell carcinoma | CK-/EMA-/CEA-/CD68+/vim+/S-100- | None | – | 15 months, ANED |

| 55 | 67/M | Unknown | 6.5 | Sarcomatoid carcinoma | CK‡-/EMA-/CD68+/vim+ | None | Unknown | 19 months, DOD |

| 65 | 61/F | Unknown | 1.5 | Sarcomatoid carcinoma† | CK‡-/EMA-/CD68+/vim+ | None | Unknown | 12 months, DOD |

| 75 | 75/F | Unknown | 1.1 | Adenocarcinoma | CK‡-/EMA-/CD68+/vim+ | None | – | 19 months, AWD |

| 86 | 58/M | RUL | 1.4 | Large cell carcinoma | CAM5.1-/CD68+ | Present§ | Unknown | Unknown |

Also containing foci of adenocarcinoma.

Including keratin AE1/AE3, keratin MAK6, and keratin CAM5.2.

Metastatic lesions also containing osteoclast-like giant cells. ANED, alive with no evidence of disease; AWD, alive with disease; ca, carcinoma; CK, cytokeratin; DOD, dead of disease; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen; Lyso, lysozyme; LUL, left upper lobe; RLL, right lower lobe; RUL, right upper lobe; S-100, S-100 protein; vim, vimentin.

In the present case, metastatic carcinoma cells admixtured with OCGCs were frequently poorly cohesive and showed weak CK7/EMA expression and no TTF-1/Napsin A expression. They expressed vimentin, which was not found in the primary tumor. These findings indicate anaplasia or epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT)10,11 of metastatic carcinomas. Moreover, 50% of the eight reported lung carcinomas with OCGCs showed anaplastic features.1–6 Hence, we speculate that anaplastic changes or EMT of metastases are related to the induction of OCGCs. Furthermore, the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) is known to be associated with the development of OCGCs in some extra-osseous tumors.12–14 Therefore, the increased levels of RANKL in the current metastases may play a role in the development of OCGCs, although further investigations are required.

Thus, this report is the first to indicate that OCGCs are present only in lung carcinoma metastases. We believe that the awareness of this possible occurrence is important in diagnosing or assessing the metastases of lung carcinoma.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- Oyasu R, Battifora HA, Buckingham WB, Hidvegi D. Metaplastic squamous cell carcinoma of bronchus simulating giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer. 1977;39:1119–1128. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197703)39:3<1119::aid-cncr2820390317>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love GL, Daroca PJ., Jr Bronchogenic sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:1004–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(83)80181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahashi H, Tsuneyoshi M, Ishida T, et al. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the lung with osteoclast-like giant cells. Jpn J Surg. 1987;17:199–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02470600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orosz Z, Tóth E, Viski A. Osteoclastoma-like giant cell tumor of the lung. Pathol Oncol Res. 1996;2:84–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02893957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocklage TJ, Dail D, Colby TV. Primary lung tumors infiltrated by osteoclast-like giant cells. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1998;2:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s1092-9134(98)80012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung CS, Morava-Protzner I. Large cell carcinoma of lung with osteoclast-like giant cells. Histopathology. 1998;32:482–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.0358f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC(eds) World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics:Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M, Oka T, Horiuchi H, Ishida T, Machinami R, Hebisawa A. Giant cell tumor of the lung: an autopsy case report with immunohistochemical observations. Pathol Int. 1994;44:158–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1994.tb01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauphin M, Barbe C, Lemaire S, et al. Vimentin expression predicts the occurrence of metastases in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Lung Cancer. 2013;81:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda T, Seki S, Maki M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells: possibility of osteoclastogenesis by hepatocyte-derived cells. Pathol Int. 2003;53:450–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2003.01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa CET, Annels NE, Faaij CMJM, Forsyth RG, Hogendoorn PCW, Egeler RM. Presence of osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells in the bone and nonostotic lesions of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Exp Med. 2005;201:687–693. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons CL, Sun SG, Vlychou M, et al. Osteoclast-like cells in soft tissue leiomyosarcomas. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-0882-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]