Abstract

Background

The oxytocin (OT) system is known to be implicated in the regulation of complex social behavior, particularly empathy and parenting. The goal of this study was to estimate the gender and population differences in polymorphisms of two oxytocin receptor gene SNPs, rs53576 and rs2254298, in four populations.

Results

These data were compared with each other and with 14 samples from the corresponding regions retrieved from the 1000 Genomes database. Low level of heterozygosity was observed for both SNPs in all populations in this study (rs53576: Catalonian, Hobs = 0.413; Hadza, Hobs = 0.556; sr2254698: Khanty-Mansi, Hobs = 0.250; Datoga, Hobs = 0.550). The amount of variance due to regional variability was almost equal for both SNPs (rs53576: FRT = 0.086, rs2554298: FRT = 0.072), whereas variance for the population level of variability was twice bigger for rs2554298 (rs53576: FST = 0.127, rs2554298: FST = 0.162). Pairwise coefficients of fixation demonstrate that the Hadza were well differentiated from other African populations except of Datoga, the Datoga were weakly differentiated from other African origin populations, the Ob Ugric people were extremely differentiated from all other populations. Catalans were extremely differentiated of Asian populations.

Conclusions

It is hypothesized on the base of spatial distribution of the evolutionary novel A alleles of the both OXTR gene loci, that the spread of alleles of rs22542298 and rs53376 SNPs may be associated to some extant with manipulation of parental investment in humans.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12863-015-0323-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Oxytocin receptor gene, SNP, rs53576, rs2254298, Parental behavior, Hadza, Datoga, Ob Urgic, Catalans

Background

The oxytocin (OT) system is known to be implicated in the regulation of complex social behavior, such as empathy, affiliated behavior and parenting, and response to social stress [1]. OT has been related to attachments between parents and children, intimate partners, relatives and friends, and its level is reported to be stable over time within individuals [2]. Several studies have indicated an association of OT with mental disorders that are characterized by impaired social behavior, such as autism, anxiety, and depression [3]. OT is a peptide of nine amino acids that is produced in the hypothalamus and released into both the brain and bloodstream. Functioning as both a neurotransmitter and hormone, oxytocin’s targets are widespread and include the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, brainstem, heart, uterus, and regions of the spinal cord that regulate the autonomic nervous system, especially the parasympathetic branch [1, 4, 5].

OT is known to regulate social bonds in animals [6], and CD38−/− knockout mice had both decreased plasma OT level and significant social impairments, including poorer maternal nurturing and less effective social behaviors [7]. Recent studies suggest that oxytocin may have similar functions in human well-being [8]. It was found that oxytocin increases trust, generosity [9] and empathy accuracy [10]. Recent neuroimaging evidence suggests that those brain areas involved in emotion processing and social danger monitoring, especially in the amygdala, were found to have decreased activation [11, 12]. Given the known heritability of empathy in humans [13], these data further suggest that genetic variation in the oxytocinergic signaling may have a role in empathy modulation [14]. Variation in the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) gene may partly explain individual differences in OT-related social behavior [15]. In humans, the oxytocin receptor is encoded by the OXTR gene which has been localized to human chromosome 3p25 and has four exons and three introns [5]. Two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the third intron have been suggested to be particularly promising candidates to explain differences in oxytocinergic functioning: rs53576 (G–A) and rs2254298 (G–A) [16].

According to the data for the rs53576 polymorphism of the OXTR gene in 12 nations, the nations with higher frequency of A allele (Japan, China, Korea) are more collectivistic in comparison with those having higher frequency of G allele (USA, UK, Australia, Canada, Netherlands, Italy, Sweden, Germany, Finland) but at the same time the last ones seem to be more predisposed to major depressive disorder [17]. Although, these data should be accepted with cautious. Same authors demonstrated recently that AA and GG carriers of OXTR rs53576 demonstrated different brain activity, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), in reaction to racial ingroup and outgroup faces that received painful or non-painful stimulations, and suggested that these differences are linked to implicit attitude and altruistic motivation [18].

The highly representative study of 7723 British mother’s behavior failed to show the relationship between rs53576 OXTR genotype and emotional loneliness [19]. While in other studies, the G allele carriers in comparison with homozygotes AA appeared to be more prosocial [20]. Positive association of the OXTR gene with autism has been demonstrated in the Chinese Han population [21].

There is less evidence for the SNP rs2254298 associations with behavior qualities and personality features, although Feldman and colleagues have shown that this polymorphism may be associated with plasma levels of oxytocin, particularly individuals with GG having lower levels of OT [22]. Other authors have associated depression and anxiety with the OXTR rs2254298 polymorphism in adults [23], and with autism in children [24]. While the A allele of OXTR rs2254298 was associated with attachment security in the non-Caucasian infants [25].

OXTR demonstrate contrasting patterns of expression in brains in monogamous and polygamous species of voles, particularly, the OXTR in the septum may be associated with social behavior, whereas those in the BNST/amygdala may be associated with parental behavior [26]. Supposedly, in species with high density of OXTR in the nucleus accumbens both females and males demonstrate parental care [27]. But whether any genetic basis exist for above mentioned differences (e.g., differential sex-specific parental care) between populations, practicing monogamous and polygamous mating patterns, still remained to be tested.

It is challenging to look for such associations in human ethnics practicing monogamous and polygamous reproduction behavior. We know two African tribes that fit this criterion and one Eurasian nation that can serve as a control. The Hadza are hunter-gatherers from Northern Tanzania. Population size is about 1500 individuals. They are relatively egalitarian and monogamous and have nominal leadership [28–30]. Hadza men compete in the form of successful hunting, and female mate choice is important [31, 32]. Male reproductive output is positively associated with hunting skills and informal leadership [33, 34]. The Datoga are traditional seminomadic pastoralists of Tanzania [35]. Population size is about 100,000 individuals. They are polygynous, and horizontally divided into generation sets with clear wealth stratification [36]. The social status and number of wives and children sired by a man are correlated with his wealth [37]. To address violence within families or clans, the Datoga have developed judicial institutions based on customary laws [36, 38] that include public assembly, clan moots, and women’s and neighborhood councils. Using a system of fines and ostracizing of habitual aggressors, the Datoga manage within-tribal violence [39].

Ob-Ugric people (Khanty and Mansi) settled on the territory of Russia in Western Siberia and occupied the basins of the Ob and the Irtysh rivers, including their tributaries. According to the census conducted in 2010, Ob-Ugric peoples are just over 43 thousand people (Khanty – 31,000 and Mansi – 12,000). Their languages belong to Ugric subgroup of Finno-Ugric group of the Uralic language family. Many of them are still practicing traditional occupations, such as fishing, hunting reindeer herding, and gathering [40]. Despite the fact that currently most of the Ob-Ugric people living in villages, they still practice nomadic reindeer herding. They are patrilineal, marriages are patrilocal and basically monogamous [41].

The aim of our study was to investigate population specificity in the distributions of allelic frequencies of two SNPs in OXTR gene (rs53576, rs2254298). To meet this goal we selected three populations from traditional culture represented different regions of the world: East Africa (Hadza, Datoga), Asia (Ugric people from Western Siberia), and one modern population of South Europe (Catalonian). Populations we selected for the purpose of our study are of special interest, because they may drop some light on the functionality of rs53576 and rs2254298 polymorphisms. Two of them, Hadza and Ugric people are mainly monogamous, while Datoga are polygynous. Spanish sample has been used for comparative purposes as one of the modern industrial population, monogamous.

Results

Allele and genotype frequency distributions obtained for our four samples were compared with each other as well as to 14 samples (live in and originated from Africa: Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria; Luhya in Webuye, Kenya; African Ancestry in Southwest US (AASUSA); Latin America: Colombian in Medellin; Puerto Rican in Puerto Rico; Mexican Ancestry in Los Angeles, California (MexAn); Asia: Han Chinese in Bejing (Han1), China; Southern Han Chinese (Han2), China; Japanese in Tokyo, Japan; live in and originated from Europe: Finnish in Finland; British in England and Scotland; Iberian populations in Spain; Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry (UNWE)) from the corresponding region retrieved from the 1000 Genomes database. The allele and genotype distributions did not differ significantly between men and women in all samples with p-values ranged from 0.04 (rs53576 and rs2254298) in Spanish to 0.75 (rs2254298) and 0.79 (rs53576) in Datoga (Additional file 1).

Data on distribution of allelic and genotype frequencies of the two studied SNP loci are presented in Table 1. Genotype frequencies for rs53576 and rs2254298 in the all 18 samples including four studied were in accordance with the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium with Benjamini and Hochberg correction (Table 2), corrected p-value was higher 0.05 in both cases (uncorrected p-values for rs53576 and rs2254298 varied from 0.030 to 0.948 and from 0.073 to 0.963, correspondingly.

Table 1.

Allelic and genotype frequencies of SNPs rs53576 and rs2254298 of oxytocin receptor gene in world populations

| Frequencies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Genotype | ||||||

| rs53576 | |||||||

| Population | Number | A | G | Number | AA | AG | GG |

| African All* | 1194 | 0.224 | 0.776 | 597 | 0.057 | 0.333 | 0.610 |

| Americans of African Ancestry in SW USA | 122 | 0.287 | 0.713 | 61 | 0.082 | 0.410 | 0.508 |

| Luhya in Webuye, Kenya | 198 | 0.211 | 0.789 | 99 | 0.052 | 0.320 | 0.629 |

| Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria | 216 | 0.193 | 0.807 | 108 | 0.045 | 0.295 | 0.659 |

| Hadza, Tanzania | 270 | 0.426 | 0.574 | 135 | 0.148 | 0.556 | 0.296 |

| Datoga, Tanzania | 388 | 0.302 | 0.698 | 194 | 0.077 | 0.448 | 0.474 |

| American All* | 524 | 0.343 | 0.657 | 262 | 0.116 | 0.453 | 0.431 |

| Colombians from Medellin, Colombia | 188 | 0.333 | 0.667 | 94 | 0.083 | 0.500 | 0.417 |

| Mexican Ancestry from Los Angeles USA | 128 | 0.386 | 0.614 | 64 | 0.136 | 0.500 | 0.364 |

| Puerto Ricans from Puerto Rico | 208 | 0.300 | 0.700 | 104 | 0.127 | 0.345 | 0.527 |

| Asian All* | 1144 | 0.684 | 0.316 | 662 | 0.472 | 0.423 | 0.105 |

| Han Chinese in Bejing, China | 206 | 0.716 | 0.284 | 103 | 0.505 | 0.423 | 0.072 |

| Southern Han Chinese | 210 | 0.670 | 0.330 | 105 | 0.480 | 0.380 | 0.140 |

| Khanty and Mansi | 700 | 0.571 | 0.429 | 350 | 0.349 | 0.446 | 0.206 |

| Japanese in Tokyo, Japan | 208 | 0.663 | 0.337 | 104 | 0.427 | 0.472 | 0.101 |

| European All* | 1990 | 0.361 | 0.639 | 995 | 0.132 | 0.459 | 0.409 |

| Utah Residents (CEPH) with Northern and Western European Ancestry | 198 | 0.294 | 0.706 | 99 | 0.082 | 0.424 | 0.494 |

| Finnish in Finland | 198 | 0.446 | 0.554 | 99 | 0.151 | 0.591 | 0.258 |

| British in England and Scotland | 182 | 0.393 | 0.607 | 91 | 0.191 | 0.404 | 0.404 |

| Iberian Population in Spain | 214 | 0.250 | 0.750 | 107 | 0.143 | 0.214 | 0.643 |

| Catalonian | 984 | 0.307 | 0.693 | 492 | 0.091 | 0.431 | 0.478 |

| Toscani in Italia | 214 | 0.327 | 0.673 | 107 | 0.102 | 0.449 | 0.449 |

| rs2254298 | |||||||

| African All* | 1112 | 0.238 | 0.762 | 561 | 0.053 | 0.370 | 0.577 |

| Americans of African Ancestry in SW USA | 122 | 0.287 | 0.713 | 61 | 0.049 | 0.475 | 0.475 |

| Luhya in Webuye, Kenya | 198 | 0.191 | 0.809 | 99 | 0.041 | 0.299 | 0.660 |

| Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria | 216 | 0.256 | 0.744 | 108 | 0.068 | 0.375 | 0.557 |

| Hadza, Tanzania | 226 | 0.274 | 0.726 | 113 | 0.053 | 0.442 | 0.504 |

| Datoga, Tanzania | 360 | 0.303 | 0.697 | 180 | 0.078 | 0.450 | 0.472 |

| American All* | 524 | 0.240 | 0.760 | 262 | 0.083 | 0.315 | 0.602 |

| Colombians from Medellin, Colombia | 188 | 0.225 | 0.775 | 94 | 0.083 | 0.283 | 0.633 |

| Mexican Ancestry from Los Angeles USA | 128 | 0.250 | 0.750 | 64 | 0.121 | 0.258 | 0.621 |

| Puerto Ricans from Puerto Rico | 208 | 0.245 | 0.755 | 104 | 0.036 | 0.418 | 0.545 |

| Asian All* | 968 | 0.322 | 0.678 | 484 | 0.101 | 0.441 | 0.458 |

| Han Chinese in Bejing, China | 206 | 0.320 | 0.680 | 103 | 0.103 | 0.433 | 0.464 |

| Southern Han Chinese | 210 | 0.355 | 0.645 | 105 | 0.140 | 0.430 | 0.430 |

| Japanese in Tokyo, Japan | 208 | 0.287 | 0.713 | 104 | 0.056 | 0.461 | 0.483 |

| Khanty and Mansi | 344 | 0.154 | 0.846 | 172 | 0.029 | 0.250 | 0.721 |

| European All* | 2318 | 0.107 | 0.893 | 1159 | 0.016 | 0.182 | 0.802 |

| Utah Residents (CEPH) with Northern and Western European Ancestry | 198 | 0.076 | 0.924 | 99 | 0.000 | 0.153 | 0.847 |

| Finnish in Finland | 198 | 0.081 | 0.919 | 99 | 0.000 | 0.161 | 0.839 |

| British in England and Scotland | 182 | 0.090 | 0.910 | 91 | 0.011 | 0.157 | 0.831 |

| Iberian Population in Spain | 214 | 0.107 | 0.893 | 107 | 0.000 | 0.214 | 0.786 |

| Catalonian | 1312 | 0.168 | 0.832 | 656 | 0.037 | 0.262 | 0.701 |

| Toscani in Italia | 214 | 0.173 | 0.827 | 107 | 0.051 | 0.245 | 0.704 |

*Total data for world region (1000 Genomes database http://www.1000genomes.org/) are calculated including information on our samples presented in bold letters

Table 2.

The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for 18 populations, including our data on Hadza, Datoga, Ob Ugric people and Catalonian

| Pop | DF | ChiSq | Prob | ChiSq | Prob |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs53576 | rs2254298 | ||||

| Hadza | 1 | 2.499 | 0.114 | 1.401 | 0.237 |

| Datoga | 1 | 0.810 | 0.368 | 0.780 | 0.377 |

| AASUSA | 1 | 0.121 | 0.728 | 0.901 | 0.342 |

| Lugya, Kenya | 1 | 0.004 | 0.948 | 1.507 | 0.220 |

| Yoruba, Nigeria | 1 | 0.036 | 0.850 | 0.273 | 0.601 |

| Colombia | 1 | 2.714 | 0.099 | 0.550 | 0.458 |

| MexAn | 1 | 0.040 | 0.841 | 3.218 | 0.073 |

| Puerto_Rico | 1 | 1.614 | 0.204 | 2.137 | 0.144 |

| Khanty-Mansi | 1 | 2.835 | 0.092 | 0.288 | 0.592 |

| Han1 | 1 | 0.086 | 0.769 | 0.002 | 0.963 |

| Han2 | 1 | 2.509 | 0.113 | 0.792 | 0.373 |

| Japanese | 1 | 1.137 | 0.286 | 1.035 | 0.309 |

| Catalans | 1 | 0.081 | 0.776 | 2.415 | 0.120 |

| UNWE | 1 | 0.010 | 0.920 | 0.665 | 0.415 |

| Finnish | 1 | 4.714 | 0.030 | 0.873 | 0.350 |

| British | 1 | 0.168 | 0.682 | 0.150 | 0.698 |

| Iberian | 1 | 0.974 | 0.324 | 2.629 | 0.105 |

| Toscanian | 1 | 1.251 | 0.263 | 2.282 | 0.131 |

our data presented in bold letters; probabilities were corrected in accordance with Benjamini-Hochberg: q > 0.05

We tested the close physical location of the two SNPs – 2143 bp between them with the linkage disequilibrium test with the option of unknown phases. The results obtained were in accordance with physical linkage of the two loci in three out of four studied populations. The probabilities of free allelic combination between the two locus studied were as follows: the Hadza: 0.0000003, the Ob Ugric people: 0.0005; the Catalans: 0.000006. However, in the case of Datoga, these two loci demonstrated free recombination: 0.48. Suggestively this may be due to the bottleneck effect which took place in the 19th century when Datoga were kicked out from Ngoro-Ngoro region by Maasai, the other possibility is related to the hot spot of recombination located between the SNPs. Finally, this may be due to our sample, although it relatively large (178 individuals). This fact remained to be investigated in the future as currently we are unable to explain this result.

For the SNP rs53576 the frequency of A allele in Hadza was much higher compared to other African samples, presented in Tables 2 and 4, and Datoga significantly differed only from Yoruba. Accordingly, the AA genotype frequency was the highest in Hadza. The frequency of A allele in Ob Ugric people was significantly lower compared to other Asian samples presented, same is true for the AA genotype frequency (Tables 1 and 3). Also, Ob Ugric people significantly differed from all Europeans populations presented in this study, but in this case the frequencies of A allele as well as AA genotype were higher in Ugric people compared to Europeans. The Catalonian sample for A allele and AA genotype frequencies fell within the variation of other European groups, with the exception of Finnish population (G = 17.74, d.f. = 1, p = 0.00003), as well as demonstrated no differences from Columbians, Puerto Ricans and Utah residents of European origin (Tables 1 and 3), besides, they did not differ from Datoga (Tables 1 and 3). For the SNP rs2254298 of the OXTR gene, the A allele and AA genotype frequencies for Hadza sample were comparable with the other African groups (Tables 1 and 3), this was true for Datoga as well with the exception of differences between Datoga and Luhya from Kenya (G = 4.26, d.f. = 1, p = 0.039). On the contrary, the A allele and AA genotype frequencies were significantly lower in the Ob Ugric sample compared to other Asian groups: Han1, G = 21.55, d.f. = 1, p = 0.000004; Han2, G = 34.63, d.f. = 1, p = 0.000000004; Japanese, G = 12.25, d.f. = 1, p = 0.0005 (Tables 1 and 3). Catalonian sample have similar frequencies of the A allele and AA genotype with Iberic and Toscani samples, as well as with Colombians and Puerto Ricans, but different compared to Finnish (G = 9.92, d.f. = 1, p = 0.0016), British (G = 8.70, d.f. = 1, p = 0.0032) and Utah samples (G = 12.90, d.f. = 1, p = 0.0003) (Tables 1 and 3).

Table 4.

Pairwise FST values for our studied samples with samples from the 1000 genome database

| Datoga | AASUSA | Luhya | Yoruba | Colombian | MexAn | Puerto_Rican | Khanty-Mansi | Han1 | Han2 | Japanese | Catalonian | UNWE | Finnish | British | Iberian | Toscanian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hadza | 0.017 | 0.039 | 0.065 | 0.083 | 0.045 | 0.016 | 0.049 | 0.093 | 0.083 | 0.068 | 0.066 | 0.088 | 0.094 | 0.072 | 0.071 | 0.065 | 0.053 |

| Datoga | 0.004 | 0.019 | 0.026 | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.169 | 0.144 | 0.122 | 0.121 | 0.073 | 0.070 | 0.088 | 0.067 | 0.040 | 0.029 | |

| Khanty-Mansi | 0.217 | 0.247 | 0.266 | 0.221 | 0.174 | 0.227 | 0.169 | 0.164 | 0.166 | 0.244 | 0.258 | 0.213 | 0.228 | 0.236 | 0.227 | ||

| Catalonian | 0.063 | 0.068 | 0.083 | 0.053 | 0.058 | 0.055 | 0.244 | 0.170 | 0.165 | 0.140 | 0.062 | 0.068 | 0.056 | 0.053 | 0.051 |

Table 3.

Results of G-test for comparison of allele and genotype frequencies in the populations studied

| rs53576 | rs2254298 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop1 | Pop2 | G | df | Chi p | G | df | Chi p |

| Hadza | Datoga | 10.731 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.546 | 1 | 0.460 |

| Hadza | AASUSA | 8.890 | 1 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Datoga | AASUSA | 0.436 | 1 | 0.509 | 0.462 | 1 | 0.497 |

| Hadza | Luhya | 20.577 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.536 | 1 | 0.215 |

| Datoga | Luhya | 3.692 | 1 | 0.055 | 4.255 | 1 | 0.039 |

| Hadza | Yoruba | 33.179 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.849 | 1 | 0.357 |

| Datoga | Yoruba | 10.126 | 1 | 0.001 | 3.035 | 1 | 0.082 |

| Khanty-Mansi | Han1 | 10.234 | 1 | 0.001 | 21.548 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Khanty-Mansi | Han2 | 4.982 | 1 | 0.026 | 34.627 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Khanty-Mansi | Japanese | 4.566 | 1 | 0.033 | 12.254 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Spanish | Colombian | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.320 | 1 | 0.251 |

| Spanish | MexAn | 6.610 | 1 | 0.010 | 5.960 | 1 | 0.015 |

| Spanish | Puerto_Rican | 0.444 | 1 | 0.505 | 1.838 | 1 | 0.175 |

| Spanish | UNWE | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 12.903 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Spanish | Finnish | 17.743 | 1 | 0.000 | 9.919 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Spanish | British | 3.602 | 1 | 0.058 | 8.695 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Spanish | Iberian | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 1.453 | 1 | 0.228 |

| Spanish | Toscanian | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 1.000 |

Legend: Pop1 and Pop2 are populations to be compared for their frequency distributions, G – G-criterion, d.f. – degrees of freedom, Chi p – probability value obtained on the bases of χ2 distribution

Low level of heterozygosity was observed for the both SNPs in all populations in this study. European populations are characterized with the lowest values of observed heterozygosity (Table 1).

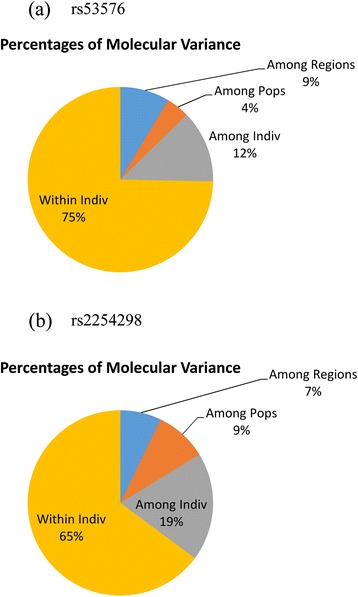

Percentages of molecular variance for both SNPs are presented on Fig. 1. The amount of variance due to regional variability is almost equal for both SNPs (rs53576: FRT = 0.086, p = 0.001; rs2554298: FRT = 0.072, p = 0.001), whereas variance for the population level of variability was twice bigger for rs2554298 (rs53576: FST = 0.127, p = 0.001; rs2554298: FST = 0.162, p = 0.001). Coefficient of fixation demonstrates the degree of population differentiation (Table 4). According to these values, the Hadza are well differentiated from other African populations except of Datoga, and also from the rest of populations except of Mexicans (from LA). The Datoga are weakly differentiated if at all from other African origin populations, including Afro-Americans from our samples, a bit stronger differentiation is observed for Datoga vs Iberians and Toscanians. The Ob Ugric people are extremely differentiated from all other populations (from 0.093 with the Hadza to 0.266 with the Yoruba). Catalonians are moderately differentiated from others except of Asian populations (Han from Bejing, 0.17; Han from South China, 0.17, Japanese from Tokyo, 0.14) (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Diagrams of percentages of molecular variance for rs53576 (a) and rs2254298 (b)

Discussion

The frequency of A allele of rs2254298 in the OXTR gene differs a lot between the populations presented in this paper. In samples of Europeans, particularly of northern origin, the frequency of this allele is minimal, while in Asian populations the A allele frequency is much higher. Africans demonstrating intermediate frequencies but closer to Asian ones. In regards to the rs53376, Europeans and Africans demonstrated comparable A allele frequencies, and in Asian populations it’s frequencies were much higher. The principal component analysis conducted on the basis of allele frequencies of both SNPs generally reveal the distribution of 18 populations in accordance with their geographic distributions (Fig. 2). Principal Coordinate 1 reflected the geographic distribution from West to East, with Yoruba to the most West and Han from Beijing to the East. Coordinate 2 reflects the North to South distribution with Finnish being the Northern, following by British and Utah Residents (CEPH) with Northern and Western European Ancestry. Ob Ugric people being close to Finnish. The Datoga and African Americans and South Chinese located on the most South (Fig. 2). Right top quarter accumulated all African samples, as well as Colombians, and Puerto Ricans. Right low quarter united European populations with the only exception of Finnish sample. All Asian populations located in the Eastern half of space between coordinates 1 and 2 (Fig. 2). The position of Hadza sample in the space of 1 and 2 coordinated deserves special attention. Hadza outstand from other African groups, locating in direction to Asian populations. One of the possible explanations is that current combination of 2 SNP frequencies of OXTR gene may be due to bottleneck effect. It was found recently by Tishkoff with co-authors [42], that the proportion of polymorphic sites as quantified by q, indicated that formally the effective size of Hadza populations could be estimated as about 9200–20,900 individuals, meantime, currently their population has been substantially decreased in size (currently being about 1500 individuals).

Fig. 2.

Ordination of the 18 samples by means of PCA. Two numbers located near markers stand for the A allele frequencies of the rs2254298 (before slash) and the rs53376 (after slash)

A tendency can be easily seeing on the Fig. 2 concerning frequencies of the A alleles of both loci of the OXTR gene. More simple tendency is related to the rs2254298, which consists in decreasing of frequency of A allele when moving down along the Principal Ordinate 2 (from South to North). As for spatial distribution of the populations in regards to the rs53376, African populations are characterized by similar frequencies of A allele, except of Hadza. In Europeans, frequencies of A allele at the rs53376 were at least twice higher compared to the rs2254298. The highest frequencies of the A allele of rs53376 were found in Asians.

The obtained spatial distribution of allele frequencies of both loci of the OXTR gene may be explained in accordance with general information on associations between the level of plasma oxytocin and parental touch and warmness. As demonstrated for the rs2254298 SNP, the A allele being associated with lower plasma oxytocin and lower related parental attachment [22]. According to previous studies, this allele is specific for humans, as primates don’t have it, while G allele is the ancestral for this SNP [43]. Another OXTR gene SNP rs53376 has been associated with individual differences in maternal and empathic behavior as well, with A allele identified as a risk one [44]. Given the fact of distribution of these alleles world-wide in modern humans, we suggest that it is either beneficial, or at least neutral for it’s carriers. It is hypothesized, that selection in favor of A alleles of rs2254298 and rs53376 SNPs may be associated to some extant with manipulation of parental investment in humans [45–47], favoritisms towards sons, being one of possible examples. Practice of infanticide in many human populations being another example of such parental manipulation strategies [48]. Obvious preferences for sons result in sex-biased infanticide, with girls being main targets, are known to be practiced in China, Republic of Korea, India and other countries of East and South Asia [49]. Such behavior may be developed in the process of human evolution along with extension of offspring dependence and development of childhood and adolescence phases of life cycle [50]. Asian samples presented in our study had the lowest frequencies of GG genotypes on rs53576. We suggest that possible increase in frequencies of A allele in this SNP was to some extant associated with intensive practice of selective infanticide for centuries in these populations. Of course we do not mean that infanticidal practice was the only factor favoring the distribution of A alleles. Different marriage patterns, associated with different parental investment, different intensity of same sex cooperation in everyday life may be enumerated as other possible factors associated with population differences in distribution of A and G alleles of rs22542298 and rs53376 SNPs of OXTR gene in humans. In our sample those populations, known to practice selective infanticide had lowest frequencies of rs53376 G allele (China, Japan), while those with highest frequencies of this allele were those, with highest mothers investment in child care (Datoga, Nigerians, Luhya from Kenya, Columbians) and same sex male cooperation. As demonstrated by other authors, on within - population level GG rs53376 SNP male carriers in Han population of Singapore revealed significant association between GG genotype and low 2D:4D ratio (proxy to prenatal androgenization) with higher cognitive abilities in reading others emotional states [51].

Conclusions

In this study, a geographic spatial distribution of the alleles of rs22542298 and rs53376 SNPs of the OXTR gene in human populations was revealed. This regularity in the allele distributions assumes effects of some factors on polymorphism of the OXTR gene. So long as the product of this gene is involved in the regulation of complex social behavior, we hypothesize that the spread of alleles of rs22542298 and rs53376 SNPs may be associated to some extant with manipulation of parental investment in humans.

Methods

Ethics approval and consent

Institutional approvals, including university (Moscow State University Ethics Committee for data collection in Russia, Ob-Ugric people, Hadza and Datoga of Tanzania), local governmental agencies (Tanzanian Commission for Science and Technology for data collection of Hadza and Datoga), were obtained prior to conducting this study. All subjects gave their informed, verbal consent prior to participation. Verbal consent was deemed appropriate given the low literacy rates among traditional Hadza and Datoga, and was specifically approved by university EC and Tanzanian agency. The study on Spanish population was approved by the Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona (Spain) Ethics Committee and confirmed to the Helsinki Declaration. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

The present study included four samples of healthy individuals from different populations: 1) 353 Ob-Ugric people (Khanty and Mansi) from Khanty-Mansiysky Autonomous District of the Nothern-Western Siberia were collected in 2010 – 2011; 2) 135 adult Hadza and 196 adult Datoga were collected in 2006–2007 in the Lake Eyasi region of Northern Tanzania and 3) Catalonian sample, represented by 659 students have been collected at Barcelona University in 2010–2013 (Table 5).

Table 5.

General information about samples

| Population | Age (years) | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hadza | 16–70 | 72 | 63 |

| Datoga | 16–70 | 104 | 92 |

| Khanty-Mansi | 16–71 | 127 | 226 |

| Catalonian | 17–51 | 157 | 502 |

DNA analysis

All the participants provided Buccal samples. Genomic DNA was isolated using Diatom DNA Prep 200 (Isogen Lab, Moscow, Russia) (samples 1 and 2) and Real Extraction DNA kit (Durviz S.L.U., Valencia, Spain) (sample 3). DNA quality from all the samples was assessed by spectrophotometer readings (A260/280) using Nanodrop.

Two polymorphisms in the OXTR gene (rs53676 and rs2254298) were genotyped using Taqman 5′ exonuclease assay (Applied Biosystems). The probes for genotyping were ordered through the TaqMan SNP genotyping Assays (ID: C___3290335_10) and (ID: C__15981334_10) Applied Biosystems assay-on-demand service. The final volume was 5 μl, which contained 5 ng of genomic DNA, 2.5 μl of Taqman Master Mix and 0.25 μl of 40 genotyping assay. Polymerase chain reaction plates were read on an ABI PRISM 7900HT instrument and SDS v2.3 software (Applied Biosystems) was used for the genotype analysis of data.

Statistical analyses

All population statistical data processing was carried out using GenAlEx software v6.5 (http://biology-assets.anu.edu.au/GenAlEx/Welcome.html): genotype and allele frequencies, tests for HWE, test of homogeneity, linkage disequilibrium test, estimations of heterozogosity and FST and their significances, AMOVA.

Supporting data

The genotypic data for the all four studied populations are available by the following DOI: 10.6070/H4V40S6S. Data is deposited in LabArchives in a form that excludes any possibility of participant identification.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Russian Humanitarian Science Foundation (RU) Award Number: 15-36-01027, Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RU) Award Numbers: 13-06-00393 and 13-04-00858, the President RF program of Leading scientific Schools Award Number: 2501.2014.4, the program of the RAS for Molecular and cell Biology, the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness Award Number: PSI2011-30321-C02-01, PSI2011-30321-C02-02, the Comissionat per a Universitats i Recerca of the Generalitat de Catalunya Award Numbers: 2014SGR1070 and 2014SGR1636. Field studies in Tanzania were approved by COSTECH. We thank prof. Audax Mabulla for his support with the field work and our Hadza and Datoga friends for tolerance and understanding.

Abbreviations

- CD38−/−

A strain of CD38-deficient mice

- rs##

A reference SNP ID number is an identification tag assigned by NCBI to a group (or cluster) of SNPs that map to an identical location

- BNST

Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- AMOVA

Analysis of molecular variance

Additional file

Four studied populations. (XLSX 62 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Authors’ contributions

APR and MLB conceived, designed and directed the experiment; DAD, JNF, AR and MLB collected samples from African, Ural and Spanish populations; PRB, EMS, VAV, AR and ENP genotyped all samples; PRB, OEL and MLB analyzed the data; PRB, MLB, and APR wrote the paper. APR, AR and ENP revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Polina R. Butovskaya, Email: butovskaya@hotmail.com

Oleg E. Lazebny, Email: oelazebny@gmail.com

Evgeniya M. Sukhodolskaya, Email: j.suchodolskaya@gmail.com

Vasily A. Vasiliev, Email: shunka@mail.ru

Daria A. Dronova, Email: dariadronova@yandex.ru

Juliya N. Fedenok, Email: fedenok.julia@gmail.com

Aracelli Rosa, Email: araceli.rosa@ub.edu.

Elena N. Peletskaya, Email: epeletskaya@genelex.com

Alexey P. Ryskov, Email: ryskov@mail.ru

Marina L. Butovskaya, Email: marina.butovskaya@gmail.com

References

- 1.Carter CS, Grippo AJ, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Ruscio MG, Porges SW. Oxytocin, vasopressin and sociality. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:331–6. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman R. Oxytocin and social affiliation in humans. Horm Behav. 2012;61:380–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cyranowski JM, Hofkens TL, Frank E, Seltman H, Cai HM, Amico JA. Evidence of dysregulated peripheral oxytocin release among depressed women. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:967–75. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318188ade4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumann ID. Brain oxytocin: a key regulator of emotional and social behaviours in both females and males. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:858–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F. The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:629–83. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross HE, Young LJ. Oxytocin and the neural mechanisms regulating social cognition and affiliative behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:534–47. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin D, Liu HX, Hirai H, Torashima T, Nagai T, Lopatina O, et al. CD38 is critical for social behaviour by regulating oxytocin secretion. Nature. 2007;446:41–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IsHak WW, Kahloon M, Fakhry H. Oxytocin role in enhancing well-being: a literature review. J Affect Disord. 2011;130:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature. 2005;435:673–6. doi: 10.1038/nature03701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartz JA, Zaki J, Bolger N, Hollander E, Ludwig NN, Kolevzon A, et al. Oxytocin selectively improves empathic accuracy. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:1426–8. doi: 10.1177/0956797610383439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans. Neuron. 2008;58:639–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirsch P, Esslinger C, Chen Q, Mier D, Lis S, Siddhanti S, et al. Oxytocin modulates neural circuitry for social cognition and fear in humans. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11489–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3984-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knafo A, Israel S, Darvasi A, Bachner‐Melman R, Uzefovsky F, Cohen L, et al. Individual differences in allocation of funds in the dictator game associated with length of the arginine vasopressin 1a receptor RS3 promoter region and correlation between RS3 length and hippocampal mRNA. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:266–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodrigues SM, Saslow LR, Garcia N, John OP, Keltner D. Oxytocin receptor genetic variation relates to empathy and stress reactivity in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21437–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909579106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebstein RP, Knafo A, Mankuta D, Chew SH, San LP. The contributions of oxytocin and vasopressin pathway genes to human behavior. Horm Behav. 2012;61:359–79. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer-Lindenberg A, Domes G, Kirsch P, Heinrichs M. Oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain: social neuropeptides for translational medicine. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:524–38. doi: 10.1038/nrn3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo S, Han S. The association between an oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism and cultural orientations. Cult Brain. 2014;2:89–107. doi: 10.1007/s40167-014-0017-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo S, Li B, Ma Y, Zhang W, Rao Y, Han S. Oxytocin receptor gene and racial ingroup bias in empathy-related brain activity. Neuroimage. 2015;110:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connelly JJ, Golding J, Gregory SP, Ring SM, Davis JM, Smith GD, et al. Personality, behavior and environmental features associated with OXTR genetic variants in British mothers. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Stead JD, Matheson K, Anisman H. A paradoxical association of an oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism: early-life adversity and vulnerability to depression. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:128. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu S, Jia M, Ruan Y, Liu J, Guo Y, Shuang M, et al. Positive association of the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) with autism in the Chinese Han population. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:74–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldman R, Zagoory-Sharon O, Weisman O, Schneiderman I, Gordon I, Maoz R, et al. Sensitive parenting is associated with plasma oxytocin and polymorphisms in the OXTR and CD38 genes. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa B, Pini S, Gabelloni P, Abelli M, Lari L, Cardini A, et al. Oxytocin receptor polymorphisms and adult attachment style in patients with depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1506–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell DB, Datta D, Jones ST, Lee EB, Sutcliffe JS, Hammock EA, et al. Association of oxytocin receptor (OXTR) gene variants with multiple phenotype domains of autism spectrum disorder. J Neurodev Disord. 2011;3:101–12. doi: 10.1007/s11689-010-9071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen FS, Barth ME, Johnson SL, Gotlib IH, Johnson SC. Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) polymorphisms and attachment in human infants. Front Psychol. 2011;2:200. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Insel TR, Shapiro LE. Oxytocin receptor distribution reflects social organization in monogamous and polygamous voles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5981–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olazábal DE. Comparative analysis of oxytocin receptor density in the nucleus accumbens: an adaptation for female and male alloparental care? J Physiol Paris. 2014;108:213–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodburn JC. Egalitarian societies. Man (new series) 1982;17:431–51. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodburn JC. African hunter-gatherer social organization: Is it best understood as a product of encapsulation? In: Ingold T, Riches TD, Woodburn J, editors. Hunters and gatherers v.1: history, evolution and social change. Oxford: St. Martin’s Press; 1988. pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marlowe FW. The Hadza: hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marlowe FW. The mating system of foragers in the standard cross-cultural sample. Cross Cult Res. 2003;37:282–306. doi: 10.1177/1069397103254008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marlowe FW, Berbesque JC. The human operational sex ratio: Effects of marriage, concealed ovulation, and menopause on mate competition. J Hum Evol. 2012;63:834–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marlowe FW. Mate preferences among Hadza hunter-gatherers. Hum Nat. 2004;15:365–76. doi: 10.1007/s12110-004-1014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butovskaya ML. Aggression and conflict resolution among the Nomadic Hadza of Tanzania as compared with their pastoralist neighbors. In: Fry DP, editor. War, peace, and human nature the convergence of evolutionary and cultural views. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 278–96. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomikawa M. Family and daily life: an ethnography of the Datoga pastoralists in Mangola. Senri Ethnol Stud. 1978;1:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lane C. Pastures lost: Barabaig economy, resource tenure, and the alienation of their land in Tanzania. Nairobi: Initiatives Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butovskaya ML. Reproductive success and economic status among the Datoga – semi-sedentary pastoralists of Northern Tanzania. Ethnographic Rev. 2011;4:85–99. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butovskaya ML, Karelin DV, Burkova VN. Datoga of Tanzania today: ecology and cultural attitudes. Asia Africa Today. 2012;11:51–5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Butovskaya ML. Wife battering and traditional methods of its control in contemporary Datoga pastoralists of Tanzania. J Aggress Confl Peace Res. 2012;4:28–45. doi: 10.1108/17596591211192975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Novikova N. Hunters and Oil workers: studies in legal anthropology. Moscow: Nauka; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulemzin VM. Meet Khanty. Novosibirsk: Nauka; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lachance J, Vernot B, Elbers CC, Ferwerda B, Froment A, Bodo JM, et al. Evolutionary history and adaptation from high-coverage whole-genome sequences of diverse African hunter-gatherers. Cell. 2012;150:457–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chelala C, Khan A, Lemoine NR. SNP nexus: a web database for functional annotation of newly discovered and public domain single nucleotide polymorphisms. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:655–61. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skuse DH, Lori A, Cubells JF, Lee I, Conneely KN, Puura K, et al. Common polymorphism in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) is associated with human social recognition skills. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1987–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302985111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bjorklund DF, Shackelford TK. Differences in parental investment contribute to important differences between men and women. Curr Dir Psychol. 1999;8:86–9. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith EA, Smith SA, Anderson J, Mulder MB, Burch ES, Jr, Damas D, et al. Inuit Sex-ratio variation: population control, ethnographic error, or parental manipulation? [and comments and reply] Curr Anthropol. 1994;35:595–624. doi: 10.1086/204319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trivers RL, Willard DE. Natural selection of parental ability to vary the sex ratio of offspring. Science. 1973;179:90–2. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4068.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harris GT, Hilton NZ, Rice ME, Eke AW. Children killed by genetic parents versus stepparents. Evol Hum Behav. 2007;28:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Das Gupta M, Zhenghua J, Bohua L, Zhenming X, Chung W, Hwa-Ok B. Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea. J Dev Stud. 2003;40:153–87. doi: 10.1080/00220380412331293807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bogin B. Patterns of human growth. 2. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisman O, Pelphrey KA, Leckman JF, Feldman R, Lu Y, Chong A, et al. The association between 2D: 4D ratio and cognitive empathy is contingent on a common polymorphism in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR rs53576) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;58:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]