Abstract

Recent longitudinal studies in the aftermath of natural disasters have shown that resilience, defined as a trajectory of consistently low symptoms, is the modal experience, although other trajectories representing adverse responses, including chronic or delayed symptom elevations, occur in a substantial minority of survivors. Although these studies have provided insight into the prototypical patterns of postdisaster mental health, the factors that account for these patterns remain unclear. In the current analysis, we aimed to fill this gap through a mixed-methods study of female participants in the Resilience in Survivors of Katrina (RISK) study. Latent class growth analysis identified six trajectories of psychological distress in the quantitative sample (n=386). Qualitative analysis of in-depth interviews with 54 participants identified predisaster, disaster-related and postdisaster experiences that could account for the trends in the quantitative data. In particular, preexisting and gains in psychosocial resources (e.g., emotion regulation, religiosity) and positive postdisaster impacts (e.g., greater neighborhood satisfaction, improved employment opportunities) were found to underlie resilience and other positive mental health outcomes. Conversely, experiences of childhood trauma, and pre and postdisaster stressors (e.g., difficulties in intimate partner relationships) were common among participants in trajectories representing adverse psychological responses. Illustrative case studies that exemplify each trajectory are presented. The results demonstrate the utility of mixed-methods analysis to provide a richer picture of processes underlying postdisaster mental health.

Keywords: Hurricane Katrina, Natural disasters, Trajectory analysis, Mental health, Resilience, Mixed-methods analysis, Case studies

Several recent studies have explored trajectories of psychological symptoms in the aftermath of natural disasters and other traumatic events using quantitative methods (e.g., Nandi et al. 2009; Norris et al. 2009). A common finding among these studies is that the most common response is resilience, defined as experiencing a trajectory of consistently few symptoms or problems, with minimal elevations limited to the time during the trauma and its immediate aftermath. Although less common, other symptom trajectories have been detected, including trajectories of chronic or delayed symptoms, and symptom recovery.

Although trajectory analysis has provided insight into the range of psychological responses to disasters, the factors that underlie these responses remain unclear. A handful of disaster studies have explored quantitative predictors of membership in one trajectory versus another (e.g., Self-Brown et al. 2013; Self-Brown et al. 2014). The small number of participants in the less common trajectories, however, limits the statistical power to detect factors that discriminate them from other patterns of postdisaster mental health. For example, Self-Brown and colleagues (2014) documented three trajectories among a sample of 360 mothers exposed to Hurricane Katrina: Resilience (n=237, 66 %); Recovery (n=109, 30 %) and Chronic (n=14, 4 %). Prior exposure to traumatic events was predictive of Recovery, versus Resilience. In contrast, no factors discriminated the small number of Chronic participants from Resilience or Recovery participants.

A mixed-methods analytic approach has the potential to overcome this limitation by providing insights into the lived experiences of survivors experiencing different postdisaster trajectories and a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between risk and protective factors and psychological functioning (e.g., Creswell and Plano Clark 2011; Luthar and Cushing 1999; Small 2011). Several studies have demonstrated the advantages of qualitative disaster research by elucidating the processes underlying experiences of displacement, mobilization of social capital, and adaptive coping, and giving voice to survivors (e.g., Hawkins and Maurer 2010; Lawson and Thomas 2007; Tuason et al. 2012). Yet, no study to our knowledge has combined trajectory analysis with qualitative analysis in a disaster context.

In the current study, we conducted a mixed-methods study of disaster mental health among a sample of low-income mothers who survived Hurricane Katrina. We previously documented six trajectories of pre to postdisaster psychological distress and explored quantitative predictors of trajectory membership in this sample (Lowe and Rhodes 2013). We expanded on this work by triangulating the quantitative data with in-depth interview data for a subset of participants, using a nested mixed-methods study design wherein multiple forms of data are collected from the same individual (Small 2011). In doing so, we aimed to provide insight into the additional factors and complex processes that accounted for the trajectories observed in the quantitative data, and information about the broader context of participants' lives.

Methods

Participants were initially part of a larger investigation of an intervention aimed at increasing community college retention among low-income parents (Richburg-Hayes et al. 2009). Two community colleges in the larger study were located in the New Orleans area, damaged due to Katrina, and closed for the Fall 2005 academic semester. Participants from these colleges were dropped from the larger investigation, and are now being followed as part of the Resilience in Survivors of Katrina (RISK) study, which aims to examine the ways in which Katrina affected their physical and mental health, social relationships, and educational and employment activities (Rhodes et al., 2010). Institutional Review Boards from (Harvard University, Princeton University, University of Massachusetts Boston, and Washington Sate University) approved all study procedures.

Quantitative Data

Participants were enrolled in the original study between 2004 and 2005, and 492 had been enrolled in the program long enough to have completed a 12-month follow-up survey prior to Hurricane Katrina (Wave 1; W1). Approximately a year after Hurricane Katrina, between May 2006 and March 2007, 402 of the 492 W1 participants (81.7 %) were successfully located and surveyed (Wave 2; W2). Approximately four years after the hurricane, between April 2009 and March 2010, 409 of the W1 participants (83.1 %) completed an additional follow-up survey (Wave 3; W3). At each wave, trained interviewers conducted the surveys via telephone, and participants were sent $20 gift cards at W1 and $50 gift cards at W2 and W3 for their participation. Participants provided oral informed consent.

Psychological distress was assessed at each wave using the K6 Scale, a six-item screening measure of non-specific psychological distress (Kessler et al. 2003). Items on this scale (e.g., “During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel so depressed that nothing could cheer you up?”) are rated from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time), and severity scores are computed as the sum of all items, with scores 0–7 indicative of a probable absence of mental illness, 8–12 probable mild or moderate mental illness, and 13 and above probable serious mental illness (Kessler et al. 2003). Cronbach's alpha reliability of the K6 scale in this study ranged from .70 to .81.

In addition to the K6 Scale, participants provided demographic information, such as their age, race/ethnicity, and number of children, at W1. At W2, participants completed a module of hurricane-related exposure, which included an inventory of hurricane-related stressors (e.g., lack of food, water, and access to medical care) and items assessing bereavement, pet loss, and the number of residential moves that had made since the hurricane. At each wave, participants also reported on access to social benefits (e.g., welfare, food stamps) and completed a measure of perceived social support, the Social Provisions Scale (Cutrona and Russell 1987). More detailed information on these measures can be accessed elsewhere (Lowe and Rhodes 2013).

Quantitative Analytic Strategy

The RISK trajectory study is described in a previously published manuscript (Lowe and Rhodes 2013). In brief, latent class growth analysis (LCGA) of psychological distress (i.e., K6 scale severity scores) was conducted in Mplus 6.0 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2010) and both statistical and theoretical considerations were taken into account when selecting the best-fitting model (Jung and Wikrama 2008). The most likely class membership for each participant was exported as a categorical variable. A series of bivariate oneway analyses of variance (ANOVAs), chi-square tests, and Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests were then conducted in SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp. 2010) to assess differences among the trajectories in demographic characteristics, hurricane-related exposures, access to social benefits, and perceived social support.

Qualitative Data

In-depth interviews with 63 participants took place four to seven years postdisaster. The purposes of the interviews were (a) to provide an in-depth understanding of the participants' experiences during the hurricane and its aftermath, and (b) to ascertain participants' perspectives on how the hurricane led to changes in their functioning, relationships, and goals. The interview protocol covered a range of topics that were informed by previous research on postdisaster adversity and resilience, and was designed to ascertain information on concepts similar to those in the quantitative survey in order to facilitate mixed-methods analysis of hurricane recovery in multiple spheres of respondents' lives. Examples of topics included childhood family life, predisaster employment and education, experiences in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane, postdisaster decisions about employment, education, and housing, postdisaster physical and mental health, and changes in relationships with family members, intimate partners, and friends since the hurricane.

A professor of sociology who lived and worked in New Orleans throughout Katrina and its aftermath and five doctoral students in sociology and psychology served as interviewers for the study. Interviewees were purposively sampled in three ways. First, interviewees' predisaster residence had to have been in Orleans or Jefferson Parish, and damaged due to the storm. The latter qualification was to ensure that the hurricane had a significant impact on participants' lives. Second, the interviewees were selected to include a comparable number of participants who had returned to New Orleans after the storm on one hand, and participants who had relocated elsewhere (e.g., Baton Rouge, Houston, or Dallas) on the other. Third, efforts were made to ensure that members of the trajectories derived from the quantitative analysis were represented in the interview sample. The target number of interviews was initially set at 50, with the goal of capturing a wide range of postdisaster experiences. To fulfill our three sampling criteria, however, we surpassed this target, and the final interview subsample consisted of 63 participants.

Interviews were conducted in mutually convenient locations (e.g., the interviewee's home, the interviewer's office, a coffee shop) and typically lasted between 1 and 2 hours. Interviewers explained the study and answered participants' questions, and participants provided written informed consent. With the participants' permission, the interviews were audio-recorded. The interviewers compensated participants with $50 gift cards. The interviews were semi-structured. Interviewers all had the same interview guide and were told to ask all interviewees the same questions, yet they were also trained to let the interview unfold as a conversation, without sticking rigidly to a protocol. Thus all interviews covered the same topics and questions, although not necessarily in the same order or with the same use of interview probes (Scott and Garner 2013; Weiss 1994). Interviewers were blind to the respondents' quantitative trajectories.

Qualitative Analytic Strategy

Prior to qualitative analysis, administrative staff transcribed the interviews. Accuracy of transcripts was established in two ways. First, the interviewers read the transcripts while listening to the audio recordings and made corrections as needed. Second, graduate student coders went back and forth between the interview transcripts and recordings to ensure accuracy.

Qualitative coding took place in two steps. First, graduate student coders coded data using Atlas.ti qualitative software (Muhr 1997) following procedures that facilitate mixed-methods analysis (Creswell and Plano Clark 2011). The research team created a list of topic codes based on prior research on disasters and the investigators' interests, and in alignment with the constructs assessed in the quantitative survey (e.g., mental health; education; neighborhoods). Coders applied these topic codes to the transcripts, indexing the data by interview question. To establish intercoder reliability, independent coders coded transcripts, discussed discrepancies until consensus was reached, and refined codes accordingly.

Second, for the current analysis, the three authors sorted the interviews according to the empirically derived trajectory groups and reviewed the topic codes for each group. We then read and reread each of the case studies within each trajectory, sorting the data within each case into reports related to three time periods: 1) the predisaster period, 2) the period during the disaster and its immediate aftermath, and 3) the longer-term postdisaster period. Based on all three authors' reading of the interviews, the first author coded each interview, following standard methodology for combining quantitative trajectories and qualitative case studies (Small 2011; Suárez-Orozco et al. 2010) and for coding data when only one coder is involved (Scott and Garner 2013). Thematic codes were created and applied based on patterns detected in the data using a grounded theory approach (Miles and Huberman 1994) and internal validity was established using pattern matching (Yin 2003). A summary of the patterns within each time period for each trajectory was created, and an illustrative case study that best represented the experiences of each group was selected. The results thus combine a thematic (variable-centered) analysis and a narrative (person-centered) analysis (Small 2009).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participants in the quantitative sample included female participants who had completed both the W1 and W2 surveys (n= 386). The small number of male participants (n=16) was dropped in light of documented gender differences in psychological responses to disasters (e.g., Norris et al. 2002). The mean age of the 386 women upon enrollment in the study was 26.60 years old (SD=4.43), and the majority of participants (84.8 %) identified as African American, 10.4 % as White, 3.2 % as Hispanic, and 1.8 % as “other.”

Of the 63 interviewees in the qualitative sample, 54 women were included in the quantitative trajectory analysis, whereas nine participants had been dropped due missing data. The mean age of the 54 upon enrollment was 25.63 years (SD=4.56), and the majority (84.6 %) identified as African American, 9.6 % as White, and 5.8 % as Hispanic. No demographic differences were detected between the 54 interviewees and the 332 other participants in quantitative sample.

Quantitative Results

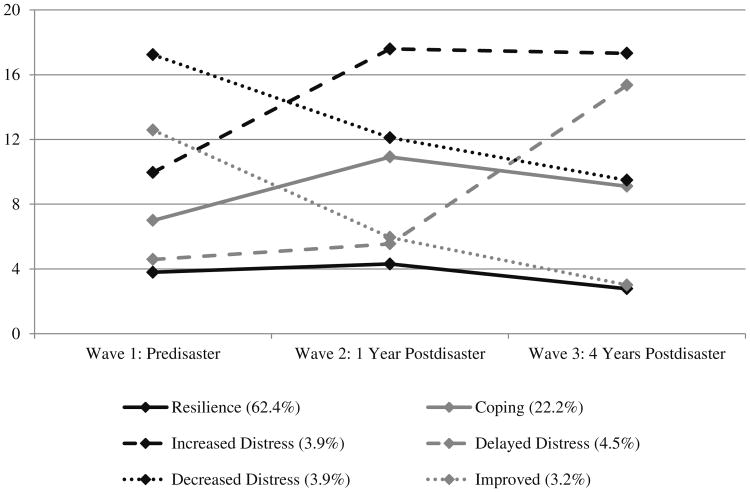

The full results of the quantitative analyses are detailed in our previously published paper (Lowe and Rhodes 2013). In brief, the model that was selected as best representing the data included six trajectories, which are depicted in Fig. 1. Descriptive data on levels of psychological distress (i.e., K6 scale severity scores) for each trajectory are also provided in Table 1. The most common trajectory was Resilience (n=241, 62.4 %) and was characterized by a probable absence of mental illness across all three waves, an increase in psychological distress between W1 and W2, and a decrease between W2 and W3. The second most common trajectory was labeled Coping (n=86, 22.2 %) and had a similar pattern as Resilience, but at a higher level of distress at each wave. At W1, Coping participants had a probable absence of mental illness, whereas as at both W2 and W3 they evidenced probable mild or moderate mental illness.

Fig. 1.

RISK psychological distress trajectories. Psychological distress was measured with the K6 scale (Kessler et al. 2003). Scores of 0–7 are indicative of a probable absence of mental illness, 8–12 moderate mental illness, and 13 or greater serious mental illness. Additional information on the quantitative analysis can be found elsewhere (masked for blind review)

Table 1. Summary of findings from quantitative and qualitative analyses.

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Trajectory | Pattern and predictors of psychological distress | Pre-disaster | Disaster | Post-disaster |

| Resilience (Quant. n=241, Qual. n=18) |

|

|

|

|

| Coping (Quant. n=86, Qual. n=11) |

|

|

|

|

| Increased distress (Quant. n=15, Qual. n=7) |

|

|

|

|

| Delayed distress (Quant. n=17, Qual. n=7) |

|

|

|

|

| Decreased distress (Quant. n=15, Qual. n=8) |

|

|

|

|

| Improved (Quant. n=12, Qual. n=3) |

|

|

|

|

Quant. quantitative; Qual. qualitative; W1 wave 1 (pre-disaster); W2 wave 2 (approximately one year post-disaster); W3 wave 3 (approximately four years post-disaster). MI mental illness. (+) = Predictor positively associated with trajectory membership; (−) = Predictor negatively associated with trajectory membership. Quantitative analysis based of 386 female participants. Psychological distress was measured with the K6 Scale (Kessler et al. 2003), with scores 0–7 indicative of probable MI, 8–12 of probable mild-moderate MI, and 13 and above serious MI. Trajectory were derived through latent class growth analysis. Predictors were explored in bivariate one-way analyses of variance and chi-square tests, with Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests. Qualitative analysis based on in-depth interviews with 54 female participants

Two less frequent trajectories were marked by increases in distress. First, the Increased Distress trajectory (n=15, 3.9 %) reported distress consistent with probable mild or moderate mental illness at W1, and consistent with serious mental illness at W2 and W3. Second, the Delayed Distress trajectory (n=17, 4.5 %) had low levels of distress W1 and W2, but reported distress consistent with probable serious mental illness at W3.

Finally, the two remaining trajectories, again representing small percentages of participants in the sample, had decreases in distress over the course of the study. The first, labeled Decreased Distress (n=15, 3.9 %) evidenced probable mental illness at each wave, but had consistently decreasing levels of distress throughout the study. At W1, their distress was in the probable serious mental illness range, and at W2, in the mild or moderate range. From W2 to W3, their distress further decreased, albeit still within the mild or moderate range. The second, labeled Improved (n=12, 3.2 %) also had probable serious mental illness at W1, but were differentiated by their probable absence of mental illness at W2 and W3.

In bivariate analyses exploring differences among the trajectories, no significant demographic differences were detected. Resilience participants had significantly higher perceived social support at W1 (relative to Decreased Distress participants), W2 (relative to Coping and Increased Distress participants), and W3 (relative to Increased Distress participants). At W2 only, Decreased Distress participants had access to significantly more social benefits (relative to Resilience, Coping, Delayed Distress, and Improved participants). In terms of hurricane exposure, Resilience participants experienced significant fewer hurricane-related stressors and were less likely to experience bereavement, relative to Coping and Decreased Distress participants. Increased Distress participants were significantly more likely to have experienced pet loss, relative to Resilience, Coping, and Delayed Distress participants.

Qualitative Results

The thematic codes generated during the qualitative analysis for the current study included the following: distal predisaster experiences (e.g., childhood trauma), proximal predisaster experiences (e.g., intimate partner strain), predisaster psycho-social resources (e.g., social support), hurricane-related exposures and stressors (e.g., housing damage, living conditions), postdisaster impacts and outcomes (e.g., psychological distress, neighborhood satisfaction), and pre to postdisaster changes in psychosocial resources (e.g., emotion regulation skills). Table 1 presents an overview of the trends observed in the qualitative data. Next, we summarize the findings and present an illustrative case study for each trajectory.

Resilience

Analyses of the case studies of Resilience participants (n=18) revealed a continuity of psychosocial and economic resources from pre to postdisaster that promoted participants' mental health. Although some women reported stressful childhood experiences (e.g., financial hardship), they emphasized that they had grown through them, with the help of many supportive others, including relationships with immediate and extended family members, mentors, teachers, church members, and friends. They also had several additional resources in place prior to the hurricane, including stable employment, financial savings, car ownership, and supportive intimate relationships. During the hurricane and its immediate aftermath, they drew on these resources to shield themselves from exposure and to maintain contact with family and friends. In the aftermath of the storm, these resources helped Resilience participants to reestablish their lives, for example by finding stable housing in safe neighborhoods, making further progress in their education and careers, identifying good schools for their children, and establishing new friendships. They also tended to emphasize the importance of religion in their lives, and to state that the hurricane had increased their sense of faith. Although some Resilience participants reported adverse experiences during the hurricane and its aftermath, including damage to their predisaster homes, loss of personal possessions, dissatisfaction with postdisaster neighborhoods, and conflicts with previous or current intimate partners, they emphasized that their experiences could have been much worse and that they were fortunate compared to other Katrina survivors. In evaluating their experiences, they generally stated that they had both recovered from the hurricane and had grown through their experiences. Resilience participants' tendency to generate and make use of resources, positively evaluate their experiences, and grow through adversity is evident in the illustrative case study of Keanna.

Keanna,1 a 34-year old African American woman, had lived in New Orleans East for her entire life. She grew up with both parents and two siblings, and was very involved at a church where her father was the pastor. At the time of the hurricane, she was living in an apartment with her husband and five children. She and her husband were in the process of purchasing a new home and, although the deal did not go through after the hurricane, Keanna reflected that this “may have been for the best.” Prior to the hurricane, Keanna had earned a certificate in medical assistance and was working in the field. Her husband was employed as a truck driver.

Keanna and her extended family evacuated to Houston prior to the hurricane. The family stayed in a hotel for three weeks and, although the room was small, the family “made the best of it.” A family friend helped find them a house in Houston to rent in a quiet, racially diverse neighborhood. She quickly found a job working for a Katrina assistance organization, for which she conducted intake assessments and referred survivors to case managers and relief agencies. This position gave her the perspective that her experience could have been much worse. At the same time, their stories took an emotional toll, and Keanna saw a mental health counselor to help her cope with the secondary trauma. Her children also saw a counselor, although she believes that have adjusted very well. Another stressor in the immediate aftermath of Katrina was a temporary separation from her husband in December 2005. However, they reunited the following spring and she now considers him her closest confidant. Moreover, Keanna saw the separation as a “turning point” in that she gained a greater sense of self-reliance.

Keanna noted other positive changes in her life since the immediate aftermath of Katrina. After her job with the Katrina assistance organization ended, she found a medical assistant job and reenrolled in higher education to advance her career. To make extra money, she started a small catering business and surprised herself with her success. Her relationship with her husband continued to improve, and she continued to have the support of family and friends, most of whom have also made Houston their permanent home. She had become an active member of a church, where she volunteered as a Bible studies teacher and mentor. She herself had found a mentor there, an older woman who was especially helpful when she was separated from her husband. She believed that her faith and relationship with God had become stronger. Overall, she saw herself as recovered, which meant to her “that I'm over it, that I've moved on, and that I've been able to reestablish my life somewhere else.”

Coping

Compared to participants in the Resilience trajectory, Coping participants (n=11) generally reported higher exposure to stressors from the pre to postdisaster periods. Although their greater exposure seemed to increase risk for moderate psychological distress, Coping participants' active approach to securely and maintaining resources prevented such distress from escalating into serious mental illness. Some Coping participants recalled stable and happy childhoods, while others reported major early stressors, including parental divorce, death, and drug addiction, sexual abuse, and financial strain. Others reported stressors more proximal to the hurricane, including intimate relationship strain, partner incarceration, bereavement, familial drug addiction, and health ailments. Despite these stressors, Coping participants generally reported several predisaster resources, including residence in safe neighborhoods, progress in their education and careers, and support from family members and intimate partners.

Although most Coping women evacuated before Katrina and were able to stay with family temporarily, they reported several hurricane-related stressors, including cramped living conditions, severe housing damage, loss of sentimental possessions, difficulty getting in touch with loved ones, and children's adjustment difficulties. Many also reported significant stressors in the postdisaster year period, such as the death of a loved one, relationship strain or dissolution, and exposure to crime, violence, and discrimination. Consistently, however, Coping participants made substantial efforts to overcome these stressors, identifying various sources of postdisaster financial support, securing new employment, making progress in their educational pursuits, and finding schools to meet their children's needs. The women also benefitted from social support – relationships that they had established both pre and postdisaster with friends, mentors, and members of their churches. They reported using their faith as a major coping resource, through praying, reading religious texts, and attending services. Some women reported moderate psychological symptoms (e.g., depression, alcohol and drug abuse, binge eating) despite these resources, whereas others stated that their Katrina experience “could have been worse,” and that they had coped well and changed for the better in its aftermath.

The illustrative case of LeShawn, a 25-year old, non-Hispanic Black lesbian woman exemplifies the Coping participants' persistence in pursuing resources and improving their lives despite enduring significant stressors.

LeShawn grew up with her mother and eight siblings. Her mother worked full-time, yet continued to struggle financially, and LeShawn started selling drugs at age 15 to help out. At age 19, LeShawn gave birth to her daughter, 6-years old at the time of the interview. She reported that childbirth was a major turning point in her life, making her more responsible and goal-oriented. Since then, LeShawn had completed two years of full-time coursework in nursing at a community college. She also worked full-time as a security guard. Aweek prior to Hurricane Katrina, LeShawn, her daughter, and her mother had moved into a new apartment in a quiet, convenient, and safe neighborhood, and were very excited about this change.

LeShawn and her family did not evacuate New Orleans during the hurricane, but were able to stay at a hotel where her mother was working. The family later took a bus to Irving, Texas, where they lived in a crowded church gymnasium for a month. While in Irving, LeShawn found a job in security through a family she met there. Eventually, a non-profit organization was able to secure housing for LeShawn in Fort Worth, where she found another job in security. LeShawn did not like her neighborhood in Fort Worth, citing crime and discrimination against New Orleans evacuees. Less than a year later, she moved to Houston, where she lived in an apartment complex that she found unsatisfactory for the same reasons.

At the time of the interview, LeShawn was living in that same apartment with her daughter and a female roommate, and continued to be dissatisfied with it. She reported that she did not like Houston, and was thinking of moving to Atlanta. Although her mother also lived in Houston, in the same apartment complex, LeShawn reported that they were not close and mostly discussed LeShawn's daughter. LeShawn also reported strained relationships with her siblings, and added that her daughter's father had also become a major stressor in her life. About a year after the hurricane, he discovered that LeShawn is a lesbian and, believing her sexual orientation made LeShawn an unfit parent, kidnapped LeShawn's daughter. LeShawn's daughter lived with her father and his new girlfriend for a year and a half. LeShawn did not know of her daughter's whereabouts until about six months prior to the interview, when her father returned her because his girlfriend had become pregnant and did not believe that they could care for both children. LeShawn's daughter had not seen her father since and missed him, and was confused about LeShawn's relationship with her girlfriend, who LeShawn had been dating for the past year.

During the interview, LeShawn stated that she had not recovered from the hurricane. She continued to struggle with intrusive thoughts about the hurricane, homesickness, nightmares, and “anger issues.” Two weeks prior to the hurricane, LeShawn had started seeing a counselor, which she hoped would help her cope with her symptoms. Despite her distress, however, it was evident that LeShawn had made some major strides in her life. She had received a certificate in phlebotomy, was employed full-time in the field, and reported enjoying her job despite working long hours. She spoke of the practical and emotional support that she received from her roommate, a close friend from New Orleans, and her girlfriend. Her girlfriend in particular had helped her to cope with her anger and to maintain a positive attitude. She also helped LeShawn care for her daughter, for example by taking the daughter to church services while LeShawn worked. LeShawn also reported that her daughter has adjusted quite well since the hurricane, and that LeShawn had found her a wonderful school with strong teachers and diverse students.

Increased Distress

Similar to Coping participants, Increased Distress participants (n=7) reported relatively high levels of stressors throughout the pre and postdisaster periods. However, Increased Distress participants had a relative absence of psychosocial resources, which seemed to increase their risk for mental health problems over the course of the study. Traumatic childhood experiences, including physical and sexual abuse, exposure to domestic violence, and parental substance abuse, were common. Several recent traumatic events were also noted, including the violent death of a family member, as was significant financial strain and persistent unemployment.

Women in the Increased Distress trajectory also noted difficult experiences during the hurricane – losses of sentimental possessions and beloved pets, unfavorable living conditions, and arguments with family members. These difficulties continued into the postdisaster period, as women reported persistent financial strain, struggles to find adequate employment, demanding work schedules, and impediments to educational success. Others noted constant tensions in their intimate relationship, including partners' drug use and criminal behavior. Although most of the women reported at least one close relationship, usually with a family member, they generally described their social relationships as stressful and unfulfilling. They also tended to report a sense of social isolation or alienation, as well as difficulty trusting others. Further traumatic events were also evident, including family bereavement and exposure to community violence. Increased Distress participants tended to report a variety of psychological symptoms – anxiety, panic, depression, mood instability, guilt, and anger. None reported being in treatment.

The illustrative case of Kayla, a 24-year old African American single mother of two, demonstrates the psychological toll of repeated exposure to traumatic events and stressors in the absence of adequate resources. In recounting her childhood, Kayla recalled the sadness she felt when her parents separated, as well as exposure to domestic violence and paternal alcohol dependence. At 16-years old, she had her first child, a daughter, with an older man that she had since come to think of as “a loser.” At the time of the hurricane, Kayla and her daughter were living with Kayla's mother, and Kayla was enrolled in college and struggling to live off of student loans and food stamps.

Kayla cried intermittently when discussing her experience with Katrina and its aftermath. She evacuated before the storm, but worried about loved ones she had left behind, especially her sister, who was then eight-months pregnant. Kayla imagined her sister going into labor and being unable to access medical care. Kayla also described a feeling of horror when she returned to New Orleans. Her mother's house had been reduced to a “concrete slab,” and a neighbor's house sat in the middle of the street. She also grieved the death of a beloved uncle due to a heart attack, which Kayla surmised was related to the stress of the hurricane.

In the wake of the storm, Kayla relocated to Slidell, Louisiana, and twice reenrolled in community college. She dropped out both times, however, which she attributed to an inability to afford textbooks, lack of empathy from her instructors, and overwhelming worry about friends and family members who were still missing. Eventually, she completed a degree in cosmetology at a school in Atlanta, but in doing so, endured living apart from her mother and children. She also described being betrayed by a friend while in Atlanta, and a similarly strained relationship with her childhood best friend. In general, she described little support in her life, aside from her mother and a new friend she had made at her current job at a department store.

Her intimate partner relationships were also a source of strain. In the aftermath of the hurricane, Kayla reconnected with her predisaster boyfriend and became pregnant with her second child. She and her boyfriend temporarily lived together, but argued frequently due to his infidelity and drug use. At the time of the interview, her boyfriend was incarcerated and Kayla noted that she did not plan on continuing the relationship upon his release. She had also recently discovered that her first child's father had robbed a bank on the same day that he had taken her children out shopping – a series of events that she found horrifying.

In reflecting upon her current situation, Kayla noted some positive aspects. Her children brought her much joy and she was happy with their schooling. She also noted that her current neighborhood, peaceful and safe, was an improvement over her predisaster neighborhood. Still, Kayla stated that she did not consider herself a success, that she had been unable to cope with the hurricane and its aftermath, and that she remained financially unable to support her family.

Delayed Distress

Unlike women in the Increased Distress trajectory, those in the Delayed Distress trajectory (n=7) tended to report predisaster psychosocial and economic resources. These resources, however, were undermined by stressors endured both during Katrina and, especially, its longer-term aftermath. Although Delayed Distress participants tended to report some childhood stressors (e.g., parental divorce, neighborhood violence), they spoke fondly of their early family lives and their general assessment was that the good outweighed the bad. They also evidenced significant predisaster accomplishments, such as progress in higher education, home ownership, or satisfying employment. All but one of the Delayed Distress participants were able to evacuate before Katrina, but reported at least some degree of stress, including cramped living conditions, worries about friends and families, and difficulties accessing postdisaster resources, including housing, financial support, and insurance reimbursement.

Most striking about the women in the Delayed Distress trajectory were the many chronic stressors they endured during the postdisaster period, including persistent neighborhood dissatisfaction among both those who stayed in New Orleans and those who relocated elsewhere, and concerns about children's safety and family members' physical and mental health. Intimate relationship strain was also evident, with participants reporting tensions and prolonged separations, as well as partners' health problems, criminal activity, and lack of financial support. Although women tended to report close relationships with family members, they noted that these relationships could be stressful, that they overwhelmingly found themselves in a caretaker role, and that they did not want to burden distressed loved ones with their problems. Psychological distress was evident in their reports, with women reporting intrusive thoughts about the hurricane and severe depression; however, none of the women reported being engaged in ongoing mental health treatment. In assessing their postdisaster experiences, Delayed Distress participants tended to state that the hurricane and postdisaster stressors had halted progress toward valued life goals, such as graduating college and building a career.

The illustrative case of Belinda, a 31-year old non-Hispanic Black mother of five, demonstrates the negative impact of postdisaster stressors on Delayed Distress participants' mental health and role functioning. Belinda grew up with her mother and grandparents, and described several happy childhood memories. She recalled that the hardest part of her childhood was her grandparents' deaths, but reported that she had come to understand that loss was a part of life. Prior to the hurricane, Belinda was working part-time and pursuing a degree in criminal justice.

Belinda evacuated before Katrina with her mother, sisters, and children to a friend's house in Springdale, Arkansas. The family stayed in Arkansas for nearly a year and, despite having to move frequently, Belinda described her experience as “like a vacation.” She received funds from FEMA, the Red Cross, and Sallie Mae, which she used to buy new furniture and clothing for the family. Belinda's partner joined her in Arkansas and she became pregnant. Dissatisfied with the medical care in Arkansas, she decided to move her family back to New Orleans, so that the family doctor could deliver the baby.

Belinda's postdisaster experience in New Orleans was mixed. She struggled to find housing, but was eventually able to get a Section 8 apartment. Her mother's house, on the other hand, continued to be in disrepair due to a legal dispute with Belinda's father, who she had hired to lead the construction efforts. Belinda stated that she wished she were back in school, but enjoyed her job at a government agency, where she did administrative work and had received on-the-job training. She believed that she would be financially stable if it were not for her two sisters, who were both unemployed and relied on her for financial support. Although she would usually lean on her mother for emotional support, she thought that her mother was depressed and did not want to burden her. Another postdisaster stressor in Belinda's life was her relationship with her partner, who had been unfaithful and had moved to Texas. She reported that her children were generally doing well, but that her son had been diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and had to drop out of therapy because the family could no longer afford it.

In summing up her experience, Belinda stated that she had not yet achieved success, nor had she recovered from the hurricane. She reported that she is an emotional and financial caretaker in her family, but that she herself does not have anyone on whom she can rely. At the time of the interview, she was struggling with depression and recent weight gain, both of which she attributed to recent stressors. Despite her struggle, she expressed hope that she would gain happiness, make progress in her education and career, reunite with her partner, and lose weight.

Decreased Distress

Like the case studies from the Delayed Distress trajectory, case studies of women from the Decreased Distress trajectory (n=8) evidenced a great degree of exposure to disaster-related and postdisaster stressors. However, the impact of these risk factors was buffered somewhat by novel opportunities and resources in the postdisaster environment. Decreased Distress participants described difficult childhoods, for example with drug addicted or absent parents, and taking on adult responsibilities at a young age. Many had endured traumatic events prior to Hurricane Katrina, including rape, robbery, and the violent death of a loved one. Their predisaster support systems were limited, with strained family relationships and few close friends. High levels of predisaster distress were also apparent, including symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress.

The Decreased Distress women also endured high levels of disaster-related stressors. They tended to move around a lot in the first post-hurricane year and to stay in shelters or otherwise crowded living conditions. Many had homes that were completely destroyed or robbed during Hurricane Katrina. Not surprisingly, Decreased Distress women reported suffering psychologically from the storm and receiving limited support from friends and family. Some talked about how the hurricane had further strained family and intimate relationships, either due to living far apart or to postdisaster conflicts. Others spoke of difficulty finding adequate employment or worries about their children's physical and mental health.

Although the Decreased Distress women continued to struggle, it was evident that each of their lives had improved in some way since the hurricane. A few got mental health treatment, which allowed them to confront painful experiences from their pasts and to cope with their postdisaster stressors. Others reported accessing suitable housing, improved employment opportunities, and better schools for their children.

In the illustrative case study of Tiffany, a 31-year old, non-Hispanic Black woman, such improvements in the context of considerable predisaster and disaster-related stressors is evident.

When Tiffany was an infant, her father abandoned the family and her mother sold drugs to make ends meet. While her grandmother raised Tiffany's younger sibling, Tiffany was left with her mother and took care of herself. She recalled feeling alone and abandoned, and experiencing physical and sexual abuse in her mother's home. She described having little support growing up, other than from an aunt, who, like Tiffany, suffered from depression and could relate to her struggles. Tiffany left high school at age 18 to have a son, but reenrolled and graduated two years later. The father of her first child was killed in a car accident, and her next partner had been unfaithful, further compromising her ability to trust others.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Tiffany moved around a lot, often living in cramped conditions. She faced other stressors as well, including exposure to gang violence, perceived racism at her son's high school, and fears that he would drop out. Members of her support system added more stress to Tiffany's life. She left her children under the care of a family member while she looked for work, and became dismayed when she perceived the temporary guardian as being neglectful. She also reported concern that her mother was stealing money from her. The stress of the hurricane and its aftermath took a toll on Tiffany's psychological functioning. She reported feeling “numb” and “stressed,” and initially coped with her symptoms by abusing marijuana.

Since the initial aftermath of the hurricane, Tiffany reported that her situation had improved somewhat. For the first time, she sought out mental health services and took antidepressants until she experienced sustained improvement in her mood. She also benefitted from her religious faith, both in reading the Bible to cope with her stress and in receiving support from a local church. In reflecting on her experience, Tiffany stated that she felt that she had recovered from the hurricane and had coped well compared to others. Although she continued to have dissatisfaction with her post-Katrina neighborhood and difficulty finding employment, she expressed hope that she would be able to achieve her goals of financial stability and homeownership.

Improved

Like the Decreased Distress participants, participants in the Improved trajectory (n=3) tended to report several predisaster, disaster-related and postdisaster stressors – as well as new opportunities and resources in the postdisaster environment. What distinguished the Improved participants was that their disaster-related and postdisaster stressors tended to be less severe, and their postdisaster support networks were generally stronger.

Improved participants reported difficulties in childhood, including exposure to domestic violence, parental divorce, sexual and physical abuse, and general tensions within their families. They also reported problematic and stressful relationships with their children's fathers. In speaking of their histories, the women reflected on how events from their past were even more stressful than Hurricane Katrina and contributed to predisaster mental health problems, such as depression and drug abuse.

The Improved women's level of exposure to the hurricane varied, ranging from very mild to extreme. All of the women endured some postdisaster stressors, including parental death and relationship tension, and some reflected on how their symptoms increased in the first postdisaster year, with one of the women even considering suicide. On the other hand, the women discussed the support they received from people in their lives – family members, friends, church members, and strangers – during the immediate aftermath. They also reported having at least one person in their lives – a friend or family member – that continued to provide them support. The Improved women also perceived some positive changes in the aftermath of disaster, such as positive employment and educational experiences, improved health, and mental health services for their children or themselves.

Strong postdisaster social support and positive changes are evident in the illustrative case study of Sandra, a 27-year old non-Hispanic Black mother.

Sandra discussed a chaotic childhood in which she endured two house fires, her mother's drug addiction, and frequent arguments between her parents. Her parents divorced when she was 16 and she got pregnant two years later. Although her father was initially disappointed about Sandra's pregnancy, he eventually became as excited as she was, and Sandra was able to finish high school with the support of family and friends. Sandra reported that the most stressful experience of her life to date came a few years later, when she discovered that her boyfriend, the father of her child, had been unfaithful and gotten one of her close friends pregnant. They engaged in a custody battle that was ongoing at the time of the hurricane.

Sandra evacuated prior to the hurricane and stayed in Florida with family for three weeks before returning to her home, where she lives with her father and son. She emphasized how lucky she was compared to other Katrina survivors, that her home had minimal damage, and that she did not lose any of her belongings. Sandra reported feeling as if she had fully recovered from the hurricane and that she had made great progress toward her life goals. Since the hurricane, she had attained a salaried position with on-the-job training that she enjoyed. She reported that her positive attitude, motivation, and interpersonal skills helped her achieve, as did the support of her father, a beloved aunt, and many close friends. The one postdisaster stressor that she reported was a recent breakup with her boyfriend of four years; however, she said that this was a positive change, given that he was a drug user and unmotivated. Moreover, the breakup has given her the opportunity to pursue a new relationship with a man, who, like her, is both family- and career-oriented.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine qualitative case studies corresponding to six trajectories of psychology distress documented in a previously published quantitative analysis of RISK study participants (Lowe and Rhodes 2013). In-depth interviews with participants from each trajectory were conducted and analyzed for common themes related to mental health, and risk and protective factors. We found that reports of mental health among the qualitative sample generally aligned with the quantitative trajectories, such that, for example, Resilience interviewees reported a consistent absence of psychological symptoms throughout their lives. The risk factors for psychological adversity identified in the quantitative analysis (e.g., exposure to more hurricane-related stressors, lower social support) were also evident in participant reports. In addition, we noted a host of risk and protective factors that were not included in the quantitative analysis, but that seemed to influence the patterns observed in the data. Case studies provided insight into how these factors operate in disaster survivors' lives to shape mental health and other outcomes.

Here, we highlight three key risk factors that were not identified in the quantitative analysis. First, prior exposure to childhood trauma (e.g., experiences of child abuse, parental drug use, and community violence) were especially apparent in the trajectories defined by higher predisaster distress (Increased Distress, Decreased Distress, Improved), and seemed to exert the greatest impact in the absence of protective factors, particularly support from friends and family. These observations are consistent with prior research showing that childhood trauma enhances risk for psychopathology following trauma exposure in adulthood (e.g., McLaughlin et al. 2010), as well as research on the benefits of supportive relationships in contexts of childhood adversity (e.g., Rhodes 2002).

Second, more recent traumatic events (e.g., sexual assault) and stressors (e.g., financial strain, relationship tensions) were apparent in trajectories that begin with high predisaster distress, aligning with prior quantitative research showing positive associations between these exposures and postdisaster mental health (Tracy et al. 2011). The Increased Distress case studies suggested that these predisaster exposures might have exerted long-term effects on mental health by increasing risk for additional stressors during the hurricane (e.g., crowded living conditions, separations from loved ones), as well as preventing survivors from reestablishing their lives in its aftermath.

Third, issues related to intimate partner relationships – prolonged separations, tensions, and partners' infidelity, alcohol and drug abuse, and incarceration – were consistent contributors to pre and postdisaster mental health. More generally, whereas the quantitative findings focused exclusively on the protective nature of social support, the interviews highlighted that social relationships were at times a source of stress, as has been observed among low-income women in non-disaster contexts (e.g., Kawachi and Berkman 2001). This was especially evident in the Delayed Distress trajectory, with interviewees describing themselves as caretakers who did not in turn receive the support of loved ones, perhaps accounting for their emergent symptoms in the longer-term postdisaster period.

In addition to these risk factors, at least three protective factors were evident that were not included in the quantitative analysis. First, participants' adaptive coping skills offset the potential psychological impact of stress. For example, Resilience participants reframed their stressful hurricane-related experiences by emphasizing the ways in which they had grown through them or by comparing themselves to others who were worse off. These techniques are reflective of emotion regulation strategies that have been associated with mental health (John and Gross 2004). Coping participants' tendency to take action in the face of stressors also emerged as a strategy that could have shielded them against psychological adversity. A similarly broad range of coping strategies was previously identified in a qualitative analysis of older adults in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina (Henderson et al. 2010).

Second, religiosity served a protective role for women in the Resilience and Coping trajectories. Women coped through their religion (e.g., through prayer, attending services), secured resources (e.g., housing, finances) from churches during the hurricane, and established supportive relationships with congregation members. In their analysis of older Katrina survivors, Henderson et al. (2010) similarly showed that survivors drew on their religion in a variety of ways to cope with the hurricane. Previous analyses of the RISK data showing higher self-reported religiosity to be associated with lower psychological distress (Chan et al. 2012), and more positive forms of religious coping (e.g., seeking spiritual support, using religion to positively reappraise a situation) with higher posttraumatic growth (Chan and Rhodes 2013) are also consistent with the current findings.

Finally, analysis of the Decreased Distress and Improved cases suggested that the hurricane sometimes presented new opportunities (e.g., employment, education, residence in safer neighborhoods, mental health services) that helped bolster the functioning of the women and their families. The aid offered to disaster victims including cash transfers from FEMA and the Red Cross, housing vouchers, and access to mental health counseling, as well as the reduction in neighborhood poverty among those who moved, provided supports that had not been available to these women before the disaster. Consistent with theory on posttraumatic growth (e.g., Tedeschi and Calhoun 1995), survivors' sense of these new possibilities in the aftermath of the disaster could have contributed to positive mental health outcomes.

The results of the study show the utility of triangulating trajectory analysis with qualitative case studies. As in our quantitative analysis, statistical models that best represent the data can yield psychological trajectories with few participants, limiting statistical power to determine which factors might account for these patterns. Furthermore, quantitative analysis is necessarily limited by the measures included in a given study, as well as the measures available to assess a given construct. By supplementing our quantitative analysis with qualitative case studies, we identified several additional risk and protective factors that could be explored in further research. Additionally, the case studies provided richer information about how risk and protective factors operated mechanistically in participants' lives to shape mental health and other outcomes.

Clinically, the results demonstrate the importance of taking a life course perspective to understand disaster survivors' presenting problems (Cherry 2009). It was clear from our analysis that sources of participants' distress were not limited to the period during Katrina and its initial aftermath and that, for some participants, the hurricane led to the opportunity to access mental health services for the first time, leading to alleviation of symptoms that were present prior to the disaster. In addition to helping patients overcome predisaster and disaster-related traumatic experiences, clinicians could assess and attend to difficulties in survivors' interpersonal relationships, especially those with intimate partners, and help them identify resources to alleviate postdisaster stressors. Efforts to build survivors' coping skills and identify new opportunities in the postdisaster environment could also facilitate positive psychological outcomes.

Although this study has the potential to inform further research and practice, it has at least three limitations. First, although generalizability is not a goal of qualitative research, it is nonetheless worth noting that the sample of low-income, primarily non-Hispanic Black mothers is not representative of the population of Katrina survivors. Moreover, the sample is unique in that all participants were community college students upon enrollment in the larger study. Second, some of the smaller trajectories from the quantitative study were represented by only a few participants in the qualitative subsample. It is possible that additional or different trends in the data would have been evident had we been able to successfully locate and interview more participants in these trajectories. Lastly, a related issue is that, in part because some of the trajectories had so few participants, the interview process spanned over three years. The mental health of participants interviewed later on might have diverged from what would be predicted by their quantitative trajectory.

Despite these limitations, this is the first study to analyze qualitative case studies alongside quantitative trajectories in the context of a major disaster. By combining these two sources of data, we illuminated how the quantitative patterns of distress manifested in survivors' lived experiences, and the ways in which risk and protective factors operated together to shape mental health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants R01 HD057599 and T32 MH013043, the National Science Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Center for Economic Policy Studies at Princeton University. We thank Thomas Brock, MDRC, Christina Paxson, and Elizabeth Fussell.

Footnotes

All participants names have been changed to pseudonyms.

References

- Chan CS, Rhodes JE. Religious coping, posttraumatic stress, psychological distress, and posttraumatic growth among female survivors four years after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:257–265. doi: 10.1002/jts.21801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CS, Rhodes JE, Pérez JE. A prospective study of religiousness and psychological distress among female survivors of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;49:168–181. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9445-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry KE. Lifespan perspectives on natural Disasters: Coping with Katrina, Rita and other storms. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell D. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In: Jones WH, Perlman D, editors. Advances in personal relationships. Vol. 1. Greenwich: JAI Press; 1987. pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins RL, Maurer K. Bonding, bridging and linking: how social capital operated in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. British Journal of Social Work. 2010;40:1777–1793. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcp087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson TL, Roberto KA, Kamo Y. Older adults' responses to Hurricane Katrina: Daily hassles and coping strategies. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2010;29:48–69. doi: 10.1177/0733464809334287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk: IBM Corp; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1301–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Wikrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:302–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78:458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Groerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Zaslavsky AM. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson EJ, Thomas C. Wading in the waters: spirituality and older Black Katrina survivors. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved. 2007;18:341–354. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe SR, Rhodes JE. Trajectories of psychological distress among low-income, female survivors of Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83:398–412. doi: 10.1111/ajop.12019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cushing G. Measurement issues in the empirical study of resilience. In: Glantz MD, Johnson JJ, editors. Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 1999. pp. 129–160. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T. ATLASti version 4.1. Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 6th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A, Tracy M, Beard JR, Vlahov D, Galea S. Patterns and predictors of trajectories of depression after an urban disaster. Annals of Epidemiology. 2009;19:761–770. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris F, Friedman M, Watson P, Byrne C, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak. Part I: an empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Tracy M, Galea S. Looking for resilience: understanding the longitudinal trajectories of responses to stress. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:2190–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE. Stand by me: The risks and rewards of mentoring today's youth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE, Chan CS, Paxson C, Rouse CE, Waters MC, Fussell E. The impact of Hurricane Katrina on the mental and physical health of low-income parents in New Orleans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:237–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01027.x. doi:0.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richburg-Hayes L, Brock T, LeBlanc A, Paxson C, Rouse CE, Barrow L. Rewarding persistence: Effects of a performance-based scholarship program for low-income parents. New York: MDRC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Scott G, Garner R. Doing qualitative research: Designs, methods and techniques. Boston: Pearson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Self-Brown S, Lai BS, Harbin S, Kelley ML. Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories following Hurricane Katrina: an initial examination of the impact of maternal trajectories on the well-being of disaster-exposed youth. International Journal of Public Health. 2014;59:957–965. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0596-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self-Brown S, Lai BS, Thompson JE, McGill T, Kelley ML. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories in Hurricane Katrina affected youth. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;147:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small M. How many cases do I need? On science and the logic of case selection in field based research. Ethnography. 2009;10:5–38. doi: 10.1177/1466138108099586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small M. How to conduct a mixed method study: recent trends in a rapidly growing literature. Annual Review of Sociology. 2011;37:55–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Gaytán FX, Bang HJ, Pakes J, O'Connor EO, Rhodes JE. Academic trajectories of newcomer immigrant youth. Developmental Psychopathology. 2010;46:602–618. doi: 10.1037/a0018201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma and transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tuason TG, Güess CD, Carroll L. The disaster continues: a qualitative study on the experiences of displaced Hurricane Katrina survivors. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012;43:288–297. doi: 10.1037/a0028054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy M, Norris FH, Galea S. Differences in the determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression after a mass traumatic event. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:666–675. doi: 10.1002/da.20838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS. Learning from strangers: The art and method of qualitative interview studies. New York, NY: The Fress Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods. 3rd. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]