Abstract

Objective

To determine if physicians find clinical decision support alerts for pharmacogenomic drug-gene interactions useful and assess their perceptions of usability aspects that impact usefulness.

Materials and Methods

52 physicians participated in an online simulation and questionnaire involving a prototype alert for the clopidogrel and CYP2C19 drug-gene interaction.

Results

Only 4% of participants stated they would override the alert. 92% agreed that the alerts were useful. 87% found the visual interface appropriate, 91% felt the timing of the alert was appropriate and 75% were unfamiliar with the specific drug-gene interaction. 80% of providers preferred the ability to order the recommended medication within the alert. Qualitative responses suggested that supplementary information is important, but should be provided as external links, and that the utility of pharmacogenomic alerts depends on the broader ecosystem of alerts.

Principal Conclusions

Pharmacogenomic alerts would be welcomed by many physicians, can be built with minimalist design principles, and are appropriately placed at the end of the prescribing process. Since many physicians lack familiarity with pharmacogenomics but have limited time, information and educational resources within the alert should be carefully selected and presented in concise ways.

Keywords: Genomic medicine, pharmacogenomics, electronic medical records, clinical decision support, clinical informatics

1. Introduction

As gene sequencing costs decrease and the body of literature supporting genomic-guided therapies grows, pharmacogenomic biomarkers are becoming more relevant to standard medical practice. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has identified over 43 pharmacogenomic biomarkers associated with a total of 139 medications commonly used in cardiac, oncological, surgical, and psychiatric care.[1] Black box warnings are included on the labels of several such drugs to alert providers to pharmacogenomic effects, yet disseminating this information for use at the point of care remains a formidable challenge.

EMR1 systems and their CDS2 features may prove crucial in the application of pharmacogenomics to patient care.[2] The increasing prevalence of EMR systems makes CDS a potentially ubiquitous tool. In addition, CDS can interact dynamically with patient-specific information in the EMR, allowing it to draw on genomic data stored in an individual's record.[3–6] Point of care alerts are one form of CDS that may be a convenient option for pharmacogenomics as they can be driven by rules engines already in use for drug-drug or drug-allergy interactions. Yet, while drug-genome alerts are a theoretically simple way to inform providers about their patients' pharmacogenomic test results, they should be implemented with caution.

Ill-conceived and poorly-designed alerts can distract health care providers from other important aspects of a patient's care.[7] Alert fatigue is a growing concern as providers are frequently inundated with low-priority and irrelevant alerts in day-to-day clinical activities.[8] Novel alerts should be considered useful by physicians and designed to quickly and accurately aid them in understanding the information and its implications.[9,10] The usefulness of alerts depends on their visual aesthetics, content composition, and timing within the clinical workflow.[11,12] Past research highlights the importance of these features for the success of drug-drug or drug-allergy alerts, but little has been studied specifically for pharmacogenomic alerts.

Early efforts to assess the usability of pharmacogenomic alerts have begun at the UW3. Devine and Overby performed a multi-methods study of pharmacogenomic alerts that were created in a simulation version of PowerChart® (Cerner Millenium®) and exposed to ten fellows in cardiology and oncology specialties.[13] Qualitative results aided in refinement of the alerts and survey results showed the participants found the alerts to be overall useful. In 2013, work began to create similar pharmacogenomic alerts in the university's live Cerner EMR system for colorectal cancer patients in a clinical trial comparing exome sequencing driven care to usual care. In the current study, our goal was to determine if this sample of physicians found the pharmacogenomic alert useful and to ascertain their perspectives on elements of usability including visual design, content choice and workflow placement. To address these goals, we created a simulation and questionnaire that could be performed online and was specific to a single drug-gene interaction between clopidogrel and CYP2C19 variants.

2. Methods

2.1 Recruitment

Physicians were recruited from the UW's major medical centers, outpatient and specialty clinics, and emergency departments. Inclusion criteria required participants to be in the UW Physicians Network or residency training program with the credentials to prescribe medications. A recruitment e-mail was sent to a random sample of 457 attending physicians, fellows, and residents that linked them to an online consent form. Physicians that consented proceeded to the online simulation portion of the study. A reminder e-mail was sent to physicians who did not respond within one week. Recruitment occurred between April 28th 2014 and May 28th 2014. Internal Review Board approval was obtained from the UW Human Subjects Division (#46932).

2.2 Simulation

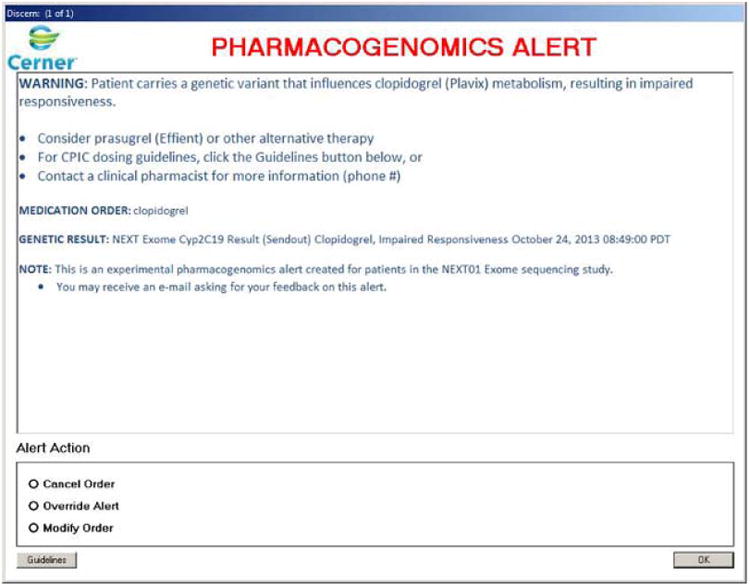

A case scenario was presented in which the participant was responsible for prescribing dual anti-platelet therapy to a patient recovering from a coronary stent placement procedure (Appendix A). The participant was given a choice of therapies to select: aspirin and clopidogrel, aspirin and ticagrelor, aspirin and prasugral, or “other” drug. Medication choices were consistent with current American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association guidelines for management of myocardial infarction.[14] Regardless of the participant's therapy of choice, he or she was then directed to an image of a pharmacogenomic alert for clopidogrel and the CYP2C19 variant. The image was created from an actual pharmacogenomic alert created in the UW Cerner® EMR for patients who were participating in the New EXome Technology (NEXT) CSER trial (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screenshot of prototype clopidogrel and CYP2C19 alert.

The prototype variant-drug alert was created in Cerner® with the Discern® rules engine. Concise information is provided explaining the variant-drug interaction and several possible actions. The “Guidelines” button loads the CYP2C19 and clopidogrel Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines in a browser window.

Development of the alert has been described in detail elsewhere.[15] Briefly, the variant-drug alert was created with input from physicians, pharmacists and lab geneticists to function similarly to drug-drug interaction (DDI) alerts, triggering when a provider submits a medication request through the Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE) for a medication that is influenced by genetic variants documented in the patient's record as a lab result. Color, font sizes, and indentation were refined to bring attention to important elements and provide subtext to shorter, bolded statements. A guidelines button was incorporated to provide access to guidelines from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium in a web browser, external to the alert. Alert text stated that the patient was a research subject in an exome sequencing study and had pharmacogenomic incidental findings stored in his EMR as discrete lab reports.

The participant was asked a series of questions about how he or she would respond to the alert in an actual clinical interaction, then proceeded to the questionnaire portion of the study.

2.2 Questionnaire

The questionnaire was a 15-item survey designed in the Catalyst WebQ® system, a UW propriety web-based, IRB-approved survey system optimized for research, to address participant perspectives of four main topics: usefulness of the alert in general, quality of the alert's visual design, appropriateness of the alert in a clinical workflow, and usefulness of the pharmacogenomic content (Appendix B). The survey was based partially on the Post-Study Systems Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ) previously used to assess pharmacogenomic clinical decision support.[13,16] The survey also included questions specific to our alerts that were not formally validated, however, we attempted to enhance validity by seeking feedback and consensus on our survey items from a variety of physicians, pharmacists, and decision support experts at our institution. Responses to the questions were provided in a 5 point Likert-scale format (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree), A/B, multiple choice and free-text response format. The A/B question format ascertained participant preferences for modifications that could be made to the alert's visual design by providing side-by-side comparison of the original alert and the modified alert.

Responses were stored in a secure, de-identified table within Catalyst WebQ®. After completing the questionnaire, participation was recognized with an online gift certificate and entry into a raffle for a larger gift certificate to a local restaurant.

2.3 Analysis

Data analysis was performed after the recruitment period closed. Data were downloaded from the Catalyst system into Microsoft Excel® (Redmond, WA). We coded qualitative responses as emerging themes. Descriptive statistics were performed using Excel or Stata 11® (College Station, TX).

3. Results

3.1 Demographics

55 physicians enrolled in the study and completed the simulation and questionnaire (12.0% recruitment rate; Table 1). The majority of study participants were between 30-39 years old, had been in practice for fewer than four years, and had practiced fewer than four years at the University of Washington. 58% of the participants were attending physicians. The most frequently represented specialties were general internal medicine, anesthesiology, family medicine, and psychiatry.

Table 1. Background Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Age in Years (N = 55) | Specialty (N = 54) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 15% | General Internal Medicine | 24% |

| 30-39 | 55% | Anesthesiology | 11% |

| 40-49 | 16% | Family Medicine | 7% |

| 50-59 | 13% | Psychiatry | 7% |

| ≥60 | 1% | General Surgery | 5% |

| Level of Training (N = 55) | Obstetrician/Gynecology | 5% | |

| Attending | 58% | Ophthalmology | 5% |

| Resident | 29% | Pediatrics | 5% |

| Fellow | 13% | Cardiology | 4% |

| Years in Practice (N = 55) | Emergency Medicine | 4% | |

| 0-4 | 55% | Hematology/Oncology | 4% |

| 5-9 | 22% | Diagnostic Radiology | 2% |

| 10-14 | 9% | Gastroenterology | 2% |

| 15-19 | 2% | Infectious Disease | 2% |

| 20-24 | 7% | Neurology | 2% |

| ≥25 | 5% | Neurosurgery | 2% |

| Years at UW (N = 55) | Orthopedic Surgery | 2% | |

| 0-4 | 73% | Otolaryngology | 2% |

| 5-9 | 16% | Pulmonology | 2% |

| ≥10 | 11% | Rehabilitation Medicine | 2% |

3.2 Simulation Behaviors

After seeing the pharmacogenomic alert the majority of participants stated they would either cancel (40%) or modify (49%) their initial order for aspirin and clopidogrel (Table 2). 4% stated they would override the alert. 7% said they would perform an “Other” option. In a free-text response, these subjects wrote that the action would be to contact a pharmacist.

Table 2. Simulation Responses Indicating Desired Behaviors.

| Action upon seeing alert (N = 55) | |

|---|---|

| Cancel Order | 40% |

| Override Alert | 4% |

| Modify Order | 49% |

| Other (call pharmacist) | 7% |

| Would use pharmacist number in alert (N = 55) | 62% |

| Would use guidelines button in alert (N = 55) | 65% |

| Would modify prescription to: (N = 51) | |

| Aspirin + Clopidogrel, altered dose | 10% |

| Aspirin + Ticagrelor | 0% |

| Aspirin + Prasugrel | 84% |

| Other (depends on team/pharmacist discussion) | 6% |

Most respondents indicated they would call the clinical pharmacist number provided in the alert, as well as use the guidelines button. After interacting with the alert, 84% stated they would change their order to aspirin and prasugrel; 10% stated they would change the dose of clopidogrel. Those who stated they would take an “Other” action wrote they would feel uncomfortable making a decision until speaking with the pharmacist or the rest of the patient's medical team.

Theme 1: Physicians wanted the option for more information when presented with the alert; whether or not they would utilize the information depended on the availability of time in their schedules

Respondents were asked to explain their choice of actions in a free-text response. Common themes included a desire for more information either about the patient or pharmacogenomic recommendations. 28 respondents stated they would want “more information” either through the listed web resources or clinical pharmacist. A number of respondents also noted their choice of actions would depend on the “flow of the day”:

“My answer(s) above would largely depend on how busy I was with other clinical duties. I would either call the pharmacist to inquire about the need for alternate dosing or consider an alternate medication than clopidogrel.”

“I would use another agent. I don't have time to do the other things”

One respondent that overrode the alert made a comment that suggests a reliance on clinical knowledge obtained through other, non-alert means:

“I would not change my standard practice based on a computerized automatic alert alone.”

Similarly, another respondent felt that a decision depended on more than the alert's recommendation:

“Next step would be possible review of more information and definite discussion with attending/team, this is an important decision that should not be made alone on the day of discharge.”

3.3 Questionnaire Responses

3.3.1 Usefulness of the Alert

92% agreed or strongly agreed that the alert was helpful in choosing an appropriate medication in the simulation scenario (Figure 2-D); 92% also agreed or strongly agreed that the alert was applicable to the case patient's medical condition. A smaller majority agreed or strongly agreed that the alert increased their confidence in their prescription choice (77%).

Figure 2. Results of Likert Scale Questionnaire Assessing Physician Perspectives.

Block A shows that most participants felt the alerts were helpful and applicable to the simulation patient. Block B shows most participants approve of interface design features and Block C shows they approved of the alerts place in the prescribing workflow. Block D shows that the majority were unfamiliar with the drug-gene interaction presented and were unsure about the evidence backing it.

Theme 2: The utility of a pharmacogenomic alert is impacted by the broader ecosystem of alerts. Some qualitative responses addressed alert usefulness directly

“The usefulness of this type of alert is largely determined/limited by the volume and usefulness of other alerts…”

This respondent felt that the alert's usefulness depended on the broader ecosystem of alerts in the UW EMR system. Similarly, another respondent felt that the utility of the alert would depend on the type of provider who encountered it:

“Those who routinely prescribe medications with these type of support tools will be familiar with the data/controversies etc. and will not benefit from the information. Those who prescribe less frequently will likely find the content very useful.”

3.3.2 Visual Interface

87% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the text provided in the alert was helpful in the decision making process; the same percentage felt that the font, color and use of bullet points was appropriate (Figure 2-A).

Theme 3: Alerts should be concise, but provide access to additional information through recommendation resources rather than guidelines

The conciseness of our alert's text, with additional information available through external sources, was appreciated by some of the participants:

“ “Make alert as simple as possible with [the] least amount of information that is needed.”

80% agreed or strongly agreed that the guidelines button was a useful element:

“[I] prefer availability of links to additional information in alerts without bogging down the alert with actual content or text of additional information.”

Though the majority also favored a version of the alert with more detailed guideline text, the consensus was less strong (67%). A small majority of participants stated that links to recommendation resources such as UpToDate® or Dynamed® should be included (60%), as well as a link to the patient's genetic lab report (52%). Conversely, most respondents did not want the patient's allele information (79%), calculators to help adjust dosing (62%), or links to additional guidelines (58%). There was ambivalence about linking to scientific literature through PubMed.

3.3.3 Appropriateness in Workflow

Most providers indicated that the alert occurred at an appropriate point in the prescribing process (91% agreed or strongly agreed; Figure 2-B). Similarly, most felt that they could easily resume their workflow after seeing the alert (95% agreed or strongly agreed).

Theme 4: Pharmacogenomic alerts are appropriately placed at the end of a prescribing process, but should be designed in a way that does not disrupt other orders

One respondent commented on how the alert could be inconvenient if it impacted the prescription process for other concurrent medications:

“Most important of all, make sure delaying decision making about this one medication does NOT prevent you from being able to continue with the rest of discharge medication reconciliation/prescribing.”

When asked about potential modifications that could be made to the alerts, 80% of respondents preferred an option to allow drug/dose modification within the alert itself (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Responses Regarding Potential Alert Modifications.

The top half of figure 3 shows the original alert (B) as well as a proposed modification (A), in which providers can change their drug/dose of choice within the alert itself. 80% of respondents preferred this option. The lower half shows another potential modification (C), in which additional CPIC guidelines are included in the text portion of the alert. A less strong majority of 67% preferred this option to the original alert.

3.3.4 Usefulness of Pharmacogenomics

While the majority of physicians felt that pharmacogenomic data, in general, would be useful in their practice, a sizeable number were unsure (30%; Figure 2-C). One provider identified a potential use for pharmacogenomic alerts based on existing tests in his/her practice:

“In [infectious disease], we already incorporate data of this nature in our practice, in that we test patients for certain HLA alleles that are associated with hypersensitivity to one of the HIV drugs, abacavir, if we are considering using this drug. There are no alerts, though. We have to know this information and proactively order the HLA test before prescribing. We work closely with a clinical pharmacist but not all areas at UW can be staffed with a pharmacist, so I think these alerts would be fantastic! Alerts could also prompt clinicians to order important testing before prescribing, as with the abacavir example.”

75% of our respondents were unfamiliar with the pharmacogenomic interaction of clopidogrel and CYP2C19 variants. Similarly, a large percentage (71%) of respondents were unsure about the level of evidence in the medical literature regarding clopiodgrel and CYP2C19.

Theme 5: Learning about pharmacogenomics at the point-of-care is acceptable to most physicians

Participants were asked to identify the most appropriate time to learn more about the pharmacogenomics of clopidogrel and CYP2C19 variants. 62% felt that learning more upon seeing the alert would be appropriate. Smaller percentages of respondents felt that it would be better to learn before the prescribing process (33%), soon after the clinical encounter (22%), or on their own time in an unrelated setting (24%). One respondent stated in a free-text response that learning at a medical conference would be ideal.

4. Discussion

The primary goal of our study was to determine if physicians found a pharmacogenomic alert useful when prescribing anti-platelet therapy for patients with CYP2C19 variants; our sample of physicians almost unanimously did. This finding is consistent with the positive response that participants in Devine and Overby's study had toward prototype pharmacogenomic decision support.[17] While “usefulness” is an admittedly vague term, it is an important starting place in establishing a gestalt for physician receptiveness to these novel alerts. If we discovered that most physicians did not find pharmacogenomic alerts to be generally useful, we would be reticent about implementing them in a live setting.

Another indicator of the usefulness of alerts is the override rate. High override rates for an alert suggest that it is has a low specificity. In other words, the alert frequently fires in situations in which it is unnecessary. Overrides can occur when the alert's content is not applicable to a given clinical scenario or when the physician wishes to proceed regardless of the alert's message. Based on our participants' stated actions in the simulation, the alert's override rate was much lower than the rates cited in CDS literature: 4% as opposed to 52-96%, respectively.[18] Drug-gene interaction alerts benefit from being inherently patient-specific. Furthermore, they can be selected to fire for only the most actionable concerns. Though our alert's override rate is likely underestimated due to the simulation-based nature of our study, it is also likely that the rate in a live setting would remain low due to the high specificity of the alert.

One of our major concerns in developing our alert interface was the amount and type of content to display. We decided to use language that was as concise as possible while still providing sufficient, actionable information. When comparing our alerts to other pharmacogenomic alerts that have been created, we were concerned that we had erred too much on the side of brevity.[19]

However, the majority of our participants found the amount of text reasonable – some respondents even lauded the conciseness. A small majority of participants indicated that additional details (e.g., guidelines for managing heterozygous vs homozygous patients) would be appropriate in the alert, but a handful stated that such information would be cumbersome. It seems reasonable to conclude that most participants were content to access additional information through the use of the guidelines button, which was considered an unobtrusive but helpful part of the display. This finding is consistent with those of Devine and Overby, in which participants strongly supported access to such resources through an “Infobutton” feature.[17]

There was ambivalence about other types of links providers would want displayed in the alert. For the most part, it seems that overloading the alert with additional links is unnecessary as most providers have resources with which they are already familiar. However, one popular request was for a link directly to the patient's pharmacogenomic lab results. Such a link would be valuable given that the new nature of pharmacogenomic lab tests may make them difficult to find in certain EMR systems. Unfortunately, we were unable to include such a link because of the restrictions of our vendor-based decision support system. Hopefully, future alert engines in major vendor EMRs will include such genomic-specific capabilities.

Another important finding was that our participants did not find the alerts to be inconveniently placed in the workflow. Alerts that hinder or disrupt a physician's normal workflow are less likely to be found useful,[7] and pharmacogenomic alerts are no exception. Others have proposed that pharmacogenomic information may be better placed in other parts of the EMR, such as the problem list or allergies list.[20] However, an important role of an alert is to serve as a reminder when such sources of knowledge acquisition have failed or been forgotten. Based on our results, pharmacogenomic alerts could be useful at the point of care.

80% of respondents supported a design in which they could modify the medication or dosage within the alert itself, as opposed to canceling the order and starting a new prescription. While this might seem to be an obvious preference, our design team was initially reluctant to include the option in the initial prototype as it increases the amount of text in the alert. Such a system may also require a large degree of maintenance from IT staff to update the available options as guidelines change. Furthermore, it requires firm decisions about which medication or dosage alternatives to present in the alert. Such choices can be difficult to make given patient specific considerations and the fluctuating evidence-base for pharmacogenomics, it also raises concerns about liability in the case of an adverse drug event. Researchers implementing pharmacogenomic CDS as a part of Vanderbilt's Pharmacogenomic Resource for Enhanced Decisions in Care and Treatment (PREDICT) project have similarly recognized that institutional support for staffing may be required to maintain accurate and timely knowledge-bases for CDS tools.[19]

One of the strongest factors desired by respondents to increase the usefulness of alerts is strengthening the evidence base for pharmacogenomics. The majority of our respondents were ambivalent or unsure about whether there was sufficient evidence to support genetically-guided anti-platelet therapy. Based on the existing literature, this is a fairly reasonable response. While our alerts are driven by Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines, the topic is far from settled in the medical literature. A recent article highlighted that the high number needed to treat of altered therapy juxtaposed with its increased risk of bleeding and higher costs makes the use of individualized therapy in low-risk percutaneous coronary intervention patients unclear.[21] Randomized control trials and meta-analyses for such interventions do not exist, so a solid evidence base is not available to help guide such decisions. Thus, the ambivalence our respondents showed is quite understandable.

Another major hindrance to the usefulness of pharmacogenomic alerts identified by our research is the lack of awareness many providers have of pharmacogenomic's role in medicine. Most of our respondents were unfamiliar with the pharmacogenomic interaction of clopidogrel and CYP2C19 variants. A small majority felt that learning about this interaction upon seeing the alert was appropriate, but sizeable numbers felt that it would be more convenient to learn about the issue at another time. Given the novelty of pharmacogenomics in patient care, it is important to consider if pharmacogenomic alerts should serve as educational tools rather than just reminders.

Our study offers early data for designing and implementing pharmacogenomic alerts. These results will be useful to institutions seeking to implement active forms of pharmacogenomic CDS. We have also described a methodology for quickly and effectively obtaining physician input on clinical informatics interventions. However, pharmacogenomic alerts may need to be studied in real medical environments for accurate assessment. Additionally, our questionnaire was not formally validated. We were unable to reuse an existing validated usability questionnaire as there were a number of nuances specific to pharmacogenomic alerts that were not addressed in such standardized surveys. However, we adapted questions from validated surveys that have been used recently to assess similar pharmacogenomic alerts. [13,16] We further sought to improve validity with feedback on our questionnaire from a number of physicians, pharmacists, and decision support experts.

Another limitation was that our sample size was not large enough to be considered representative and was limited to one institution. While we cannot state that our findings are generalizable to all physicians, we can make use of the data to hone our alerts in a user-centered design process – similar to the way one might utilize results from a focus group. Though our results may not be completely replicable in all institutions, they offer useful suggestions, insights and starting points for the development of future PGx CDS tools. A final limitation is that we only tested the alert for one drug-gene interaction. Though we did this intentionally to maximize the depth of input from our sample, we cannot be sure that the results will be applicable to alerts for other pharmacogenomic interactions. The ideal components of alerts that we have studied, such as visual design, timing in workflow or content choices may vary between alerts. Thus, caution should be practiced in applying our results to other types of pharmacogenomic alerts. The low response rate may result in selection bias. Unfortunately, we did not track data on non-respondents and thus are unable to quantify the degree of bias

Future usability studies for pharmacogenomic alerts would do well to expand their inclusion criteria to assess perspectives from other health professionals with prescribing abilities, such as nurse practitioners and pharmacists. Such studies would also benefit from exploring mixed-methods approaches to study the elements of Human-Computer Interaction.[22] In addition, research methodologies such as cluster randomized control trials and step-wedge designs that allow for the study of pharmacogenomic alerts on patient-based clinical outcomes, like morbidity and mortality, should be utilized.

Pharmacogenomics is a form of genomic medicine that is beginning to impact clinical care and could be disseminated through existing CDS alert systems. However, effective use of alerts is dependent on a variety of factors such as visual design, timing in the provider's workflow and content choice. We report findings from a study examining physician perspectives of pharmacogenomic alerts. We found that, among a sample of physicians from the University of Washington, many participants felt that such tools could be useful in prescribing medications to patients. The majority also approved of the alert's visual design and timing within the prescribing workflow. Consistent with the current state of the pharmacogenomic literature, our study revealed that many physicians were unfamiliar with the CYP2C19 and clopidogrel interactions and were ambivalent about the existing evidence base for interventions based on the interaction. The results of our study will serve as an early step toward addressing one of the many challenges facing the integration of genomics into EMR systems.

Supplementary Material

Table 3. Emerging Themes from Qualitative Responses.

| • Theme 1: Physicians wanted the option for more information when presented with the alert; whether or not they would utilize the information depended on the availability of time in their schedules. |

| • Theme 2: The utility of a pharmacogenomic alert is impacted by the broader ecosystem of alerts. |

| • Theme 3: Alerts should be concise, but provide access to additional information through external recommendation resources. |

| • Theme 4: Pharmacogenomic alerts are appropriately placed at the end of a prescribing process, but should be designed in a way that does not disrupt other orders. |

| • Theme 5: Learning about pharmacogenomics at the point-of-care is acceptable to most physicians. |

Summary Points.

What was known before this study

Electronic medical record (EMR) systems and their clinical decision support (CDS) features are likely to prove crucial in the application of pharmacogenomics to patient care.

Ill-conceived and poorly-designed alerts can distract health care providers from other important aspects of a patient's care.

Past research highlights important facets of user-centered design for successful drug-drug or drug-allergy alerts, but little has been studied specifically for pharmacogenomic alerts.

What this study adds

After interacting with a prototype pharmacogenomic alert, a sample of physicians at our institution felt that similar alerts would be a useful tool in patient care, occur at an appropriate point in the prescribing process, and preferably have concise content.

The sample of physicians provided feedback to refine the alert, for example, by allowing prescribers to change medications and doses within the alert box.

The majority of participants were unfamiliar with the pharmacogenomic interaction between CYP2C19 variants and clopidogrel metabolism.

Feedback can be efficiently ascertained from large numbers of end-users of clinical decision support alerts through accessible, online methods.

Acknowledgments

NEXTU01 faculty and staff: Gail Jarvik (University of Washington Genome Sciences), Michael Dorschner (University of Washington Genome Sciences), Laura Amendola (University of Washington Medicine), Martha Horike-Pyke.

UW Information Technology Services: Aidan Garver-Hume (University of Washington Information Technology Services), Tony Shaver (University of Washington School of Pharmacy), Thomas Payne (University of Washington Medicine).

UW Laboratory Medicine: Chuck Rohrer (University of Washington Laboratory Medicine)

Funding: Research reported in this presentation was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number TL1TR000422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

National Institute of Health, National Human Genome Research Institute:

U01 HG006507 CSER NextMed Study

U01 HG007307 The CSER Coordinating Center

Appendix A. Simulation and Questionnaire

Case Scenario

ID/CC

Mr. X is a 56 year old Korean male on your service who is in recovery following percutaneous coronary intervention with a drug-eluting stent for an ST-elevation myocardial infarction two days ago.

Current Status

The recovery has been uneventful and his current condition is stable. On physical exam he has a BP of 152/110, RR of 12, and normal O2 saturation. ECG shows inverted T waves, no new Q waves, no dysrhythmia, axis shift or conduction defects. On echo LVEF was 0.57. No recurrent ischemia, heart failure or hemodynamic compromise. There is no indication for future CABG.

Mr. X appears fatigued but in a pleasant mood.

Past Medical History

Mr. X has a history of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. He has not suffered from gastric ulcers.

You inform Mr. X of his status and tell him that he will be discharged shortly. After providing him the appropriate patient education, you log into the Cerner CPOE to prescribe him anti-platelet therapy medications to be taken at home.

Question

Which of the following dual anti-platelet therapy regimens would you prescribe Mr. X?

Required.

Aspirin + Clopidogrel (Plavix)

Aspirin + Ticagrelor (Brilinta)

Asprin + Prasugrel (Effient)

Other:

Simulation Questions

If you had ordered clopidogrel through the UW CPOE system, an alert would have appeared on the screen.

Mr. X has lab results in his electronic medical record created from genomic sequencing data he had performed as a part of a clinical trial. The sequencing revealed that Mr. X has a diminished ability to metabolize certain drugs.

Please read the alert and answer the following questions.

At this point, what action would you take?

Required.

Would you call the clinical pharmacist number listed in the alert for more information?

Yes

Yes

No

No

Would you access more information from the "Guidelines" button? The button would take you to the CPIC guidlines on PharmGKB.org

Yes

Yes

No

No

Briefly explain your choice of action(s) and elaborate your next steps in completing the prescription process for Mr. X's discharge. (Ex: I overrode the alert because…)

If you chose to modify the order, which of the following dual anti-platelet therapy regimens would you now prescribe Mr. X?

You have completed the simulation scenario. After providing background information, there are 15 questions to answer.

Appendix B – Questionnaire

Alert Helpfulness

The alert was helpful in choosing an appropriate medication for this patient.

The alert was applicable to my patient's medical condition.

I felt more confident in my prescription choice after seeing the alert.

Pharmacogenomics Helpfulness

Before this study, I was familiar with the impact of CYP2C19 variations on clopidogrel metabolism.

There is sufficient evidence supporting the use of genetic data to direct anti-platelet therapy.

Patient-specific pharmacogenomic data would be useful in my normal practice.

The Alert in Your Workflow

The alert would have occurred at an appropriate point in my prescribing process.

I would easily be able to resume the prescribing process after seeing the alert.

If you felt you needed to learn more about CYP2C19 variants and clopidogrel management, when would be the ideal time to do so?

The alert you saw is a prototype alert being built for the UW EMR system. It is likely to change based on the results of this survey. Please provide your perspective on a modified alert with different functionality.

Modified alerts could allow you to change your choice of medication or dosing in the alert itself. The images below show how this would be different from what you saw in the scenario.

This is the original alert you saw:

An alternative format allos you to alter ther prescription within the alert:

Some people might find this feature convenient, while some would find it confusing or distracting. Which type of alert would be more useful in your daily work routine?

Alert A (original) - Modify drug/dose outside of alert

Alert A (original) - Modify drug/dose outside of alert

Alert B (second) - Modify drug/dose within the alert

Alert B (second) - Modify drug/dose within the alert

No preference

No preference

Alert Contents

The text-based information in the alert helped me make a prescription decision.

The “Guidelines” button was important in helping me understand the alert.

The use of color, bullet-points, and font sizes are appropriate for this alert.

What additional information should be included in this pharmacogenomic alert?

Patient's allele information

Patient's allele information

Links to patient's genetic lab report

Links to patient's genetic lab report

Links to PubMed articles

Links to PubMed articles

Links to additional guidelines

Links to additional guidelines

Links to UpToDate, Dynamed or similar resources

Links to UpToDate, Dynamed or similar resources

Dosing calculators

Dosing calculators

Other:

Other:

For certain medications, the FDA and/or Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) provide alternative dosing suggestions depending on a patient's genetic variants. An example below shows how alerts would look without, and with the suggestions in the alert.

This is the original alert you saw:

An alternative format might include the following. Notice that it includes additional guideline information in the text to help with prescribing drug choice and dosing decisions.

Some providers would find the information helpful, while others would deem it unnecessary, irrelevant or untrustworthy. Which type of alert would be more useful in your daily work routine?

Alert A (original) - No guideline text in the alert

Alert A (original) - No guideline text in the alert

Alert B (second) - Guideline text within the alert

Alert B (second) - Guideline text within the alert

No preference

No preference

You're all done! If you have any other comments regarding decision support pop-up alerts, pharmacogenomics, or this survey, please provide them below

Footnotes

Electronic medical record

Clinical decision support

University of Washington

Author Contributions: Adam A. Nishimura: Primary author. Significant participation in the conceptualization of project, creation of the intervention, devising of the survey, administration of the survey, analysis of results, composition of the manuscript, and editing of the manuscript.

Brian H. Shirts: Significant participation in the conceptualization of project, creation of the intervention, devising of the survey, administration of the survey, and editing of the manuscript.

Joseph Salama: Significant participation in devising of the survey, analysis of results, composition of the manuscript, and editing of the manuscript.

Joe W. Smith: Significant participation in creation of the intervention and editing of the manuscript.

Beth Devine: Significant participation in the devising of the survey, analysis of results, composition of the manuscript, and editing of the manuscript.

Peter Tarczy-Hornoch: Primary Investigator. Significant participation in the conceptualization of project, creation of the intervention, devising of the survey, administration of the survey, analysis of results, composition of the manuscript, and editing of the manuscript.

Competing Interests: None to declare

References

- 1.FDA. Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling. 2014 http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm.

- 2.Overby CL, Tarczy-Hornoch P, Hoath JI, Kalet IJ, Veenstra DL. Feasibility of incorporating genomic knowledge into electronic medical records for pharmacogenomic clinical decision support. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11(Suppl 9):S10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S9-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell GC, Crews KR, Wilkinson MR, Haidar CE, Hicks JK, Baker DK, et al. Development and use of active clinical decision support for preemptive pharmacogenomics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:e93–9. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shuldiner AR, Palmer K, Pakyz RE, Alestock TD, Maloney Ka, O'Neill C, et al. Implementation of pharmacogenetics: The University of Maryland personalized anti-platelet pharmacogenetics program. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bielinski SJ, Olson JE, Pathak J, Weinshilboum RM, Wang L, Lyke KJ, et al. Preemptive genotyping for personalized medicine: design of the right drug, right dose, right time-using genomic data to individualize treatment protocol. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Donnell PH, Danahey K, Jacobs M, Wadhwa NR, Yuen S, Bush A, et al. Adoption of a clinical pharmacogenomics implementation program during outpatient care-initial results of the University of Chicago “1,200 Patients Project,”. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ash J, Sittig D, Poon E. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2007;14:415–423. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2373.Introduction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carspecken CW, Sharek PJ, Longhurst C, Pageler NM. A clinical case of electronic health record drug alert fatigue: consequences for patient outcome. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1970–3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horsky J, Schiff GD, Johnston D, Mercincavage L, Bell D, Middleton B. Interface design principles for usable decision support: A targeted review of best practices for clinical prescribing interventions. J Biomed Inform. 2012;45:1202–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartzler A, McCarty C. Stakeholder engagement: a key component of integrating genomic information into electronic health records. Genet Med. 2013;15:792–801. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.127.Stakeholder. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phansalkar S, Desai A, Choksi A, Yoshida E, Doole J, Czochanski M, et al. Criteria for assessing high-priority drug-drug interactions for clinical decision support in electronic health records. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:65. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung M, Riedmann D, Hackl WO, Hoerbst A, Jaspers MW, Ferret L, et al. Physicians' Perceptions on the usefulness of contextual information for prioritizing and presenting alerts in computerized physician order entry systems. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:111. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devine EB, Lee CJ, Overby CL, Abernethy N, McCune J, Smith JW, et al. Usability evaluation of pharmacogenomics clinical decision support aids and clinical knowledge resources in a computerized provider order entry system: A mixed methods approach. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Chung MK, de Lemos Ja, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e78–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura AA, Shirts BH, Dorschner MO, Amendola LM, Smith JW, Jarvik GP, et al. Development of clinical decision support alerts for pharmacogenomic incidental findings from exome sequencing. 2015:8–11. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis JR. Psychometric Evaluation of the PSSUQ Using Data from Five Years of Usability Studies. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2002;14:463–488. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2002.9669130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devine E, Lee C, Overby C. Pharmacogenomics Clinical Decision Support Aids and Clinical Knowledge Resources in a Computerized Provider Order Entry System: A Mixed Methods Approach. [accessed June 7, 2014];Int J Med Inform. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.04.008. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1386505614000689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Van Der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, Berg M, Paper R. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2006;13:138–148. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1809.Computerized. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pulley JM, Denny JC, Peterson JF, Bernard GR, Vnencak-Jones CL, Ramirez aH, et al. Operational implementation of prospective genotyping for personalized medicine: the design of the Vanderbilt PREDICT project. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:87–95. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overby C, Kohane I, Kannry J. Opportunities for genomic clinical decision support interventions. Genet Med. 2013;15:1–13. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.128.Opportunities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angiolillo D, Ferreiro J, Price M, Kirtane A, Stone G. Platelet function and genetic testing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:S21–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russ AL, Zillich AJ, Melton BL, Russell Sa, Chen S, Spina JR, et al. Applying human factors principles to alert design increases efficiency and reduces prescribing errors in a scenario-based simulation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.