Abstract

This study investigates the relation between parental verbal punishment and externalizing and internalizing behavior problems in Filipino children, and the moderating role of parental warmth in this relation, for same-sex (mothers-girls; fathers-boys) and cross-sex parent-child groups (mothers-boys; fathers-girls). Measures used were the Rohner Parental Acceptance-Rejection and Control Scale (PARQ/Control), the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBC), and a discipline measure (DI) constructed for the study. Participants were 117 mothers and 98 fathers of 61 boys and 59 girls who responded to a discipline interview, the Parental Acceptance-Rejection and Control scale (PARQ/Control) and the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist via oral interviews. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses (with Bonferroni-corrected alpha levels) revealed that maternal frequency of verbal punishment was positively related to internalizing and externalizing outcomes in boys and girls whereas paternal frequency of verbal punishment was positively related to girls’ externalizing behavior. Significant interactions between verbal punishment and maternal warmth in mother-girl groups were also found for both internalizing and externalizing behaviors. While higher maternal warmth ameliorated the impact of low verbal punishment on girls’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors, it exacerbated the effect of high verbal punishment on negative outcomes.

Keywords: verbal punishment, parental warmth, internalizing and externalizing behaviors, gender, Filipino parenting

Verbal punishment (e.g., yelling, the use of frequent negative commands, name-calling, and threatening) is a parenting practice that has not been extensively explored (Davidov, Grusec, & Wolfe, 2012) but is continuously experienced by children across the globe (Chang, Dodge, Schwartz, & McBride-Chang, 2003; Vissing, Straus, Gelles, & Harrop, 1991). To illustrate, in a study with a sample of 2,582 parents and their 5th and 6th grade children, Mckee, Roland, Coffelt and colleagues (2007) found that use of harsh verbal discipline (i.e., yelling, shouting, or screaming) is higher for both mothers and fathers than use of physical discipline. In another study, Straus and Field (as cited in Hutchinson & Mueller, 2008) discovered that 10–20% of toddlers and 50% of teenagers in the United States have experienced severe forms of belittlement by their parents such as, but not limited to, cursing, threatening to send the child away, and calling the child dumb.

Similarly, in the Philippines, where parental attitudes towards childrearing are thought to be more authoritarian than progressive (Alampay & Jocson, 2011), sanctions are usually made in the form of both verbal and physical punishment (De la Cruz et al., 2001, as cited in Alampay & Jocson, 2011). Esteban’s (2005) research on college students revealed that of the 294 respondents, 48% reported being highly abused verbally at least 3 times a week, 34% were verbally abused at least once a week, and only 18% were non-abused (once a month or almost never). In another study composed of street adolescents in Davao city, verbal and psychological abuse (i.e., humiliation, constant scolding, and nagging) was among the types of abuse reported (TAMBAYAN, 2003). Notably, such maltreatment was often inflicted in the context of parental discipline (TAMBAYAN, 2003).

Yet, like most research conducted in other countries (see Gershoff, 2002), most local literature has focused on parental physical punishment, and physical and sexual abuse (Marcelino et al., 2000, as cited in Esteban, 2005). Worth mentioning, too, is that majority of theories on various discipline techniques and their corresponding effects on child development have been proposed by researchers based in the West, particularly the United States (see Gershoff et al., 2010).

This paper aims to address the aforementioned research gaps by determining the relation between parental verbal punishment and behavior problems in Filipino children. Whether parental warmth moderates this relation is also investigated, as well as whether these relations vary among same-sex versus cross-sex parent-child groups (i.e., mothers and girls versus mothers and boys).

Verbal Punishment and Child Outcomes

Despite its prevalence, there does not seem to be a standard definition of verbal punishment, aggression, or of other related concepts like psychological abuse or maltreatment (Hutchinson & Mueller, 2008). For instance, verbal punishment has been defined as “scolding, yelling or derogating” (Berlin, Ispa, Fine, et al., 2009, p. 1404). Wang and Kenny (2013), on the other hand, have defined it as the use of psychological force, causing the child emotional pain, for the purpose of correcting misbehavior. Some past research exploring verbal punishment has used different single items to measure this construct (i.e., tell the child he won’t be loved anymore or scream, yell or shout at; see Lansford, Malone, Dodge, et al., 2010; Mckee et al., 2007) while others have utilized more than one (see Evans, Simons, & Simons, 2012).

For this study, the conceptual definition of verbal punishment will be patterned after Vissing et al.’s (1991, p. 224) definition: “a communication intended to cause psychological pain to another,” which may be used as a means to an end (i.e., to stop child misbehavior) or as an end in itself (i.e., an expression of anger). This paper focuses on verbal punishment in the context of parental discipline but given its varying definitions, the researchers also draw from the literature on related concepts such as verbal aggression, maltreatment, and abuse in proposing hypotheses and considering implications.

Like physical aggression, verbal aggression, even in the context of discipline, has been thought to predict children’s internalizing (problem behavior directed towards the self such as depression and anxiety) and externalizing behavior (outward expressions of aggression, destructiveness, and opposition to authority) (see Burbach, Fox, & Nicholson, 2004; Mckee et al., 2007). Vissing et al. (1991) found that parents who were verbally aggressive tended to have aggressive children regardless of whether these parents were also physically aggressive. Children were also found to be at greater risk of becoming physically aggressive, delinquent, or having interpersonal problems as experiences of parental verbal aggression increased. Teicher, Samson, Polcari, and McGreenery (2006) found associations between childhood exposure to parental verbal aggression and depression, anxiety, dissociation, and hostility. Finally, Evans et al. (2012) found that higher frequencies of verbal abuse, measured as anger, shouting/yelling, swearing, and threatening to harm, was related to increased delinquency among African American teenagers over a period of two years.

A number of theoretical perspectives account for how verbal punishment is related to negative child outcomes. Parental verbal hostility, which includes excessive criticism, repeated blaming, insults, threats and mean comments, can be damaging because it signifies parental rejection or violence (Wolfe & McIsaac, 2011) and affects the child’s social, cognitive, and behavioral development (Wekerle et al., 2006, as cited in Wolfe & McIsaac, 2011). Attachment theory, in particular, posits that attachment experiences with parents are the basis for children’s internal working models of themselves and others in relationships (Dodge & Pettit, 2003; Wu, 2007). Exposure to secure attachment experiences, such as appropriate and consistent parental responsiveness, leads children to view themselves as worthy of love and perceive the world as dependable and predictable (Wu, 2007). Alternatively, insecure attachments stemming from inconsistency in or lack of parental responsiveness lead children to deem themselves as unlovable and view the world as untrustworthy and unpredictable (Wu, 2007). Harsh verbal punishment may be one expression of parental insensitivity or lack of responsiveness (Hoeve et al., 2009), and exposure to such may place children at greater risk for being disordered or challenging (O’Gorman, 2012).

Dodge and Pettit’s (2003) biopsychosocial model likewise maintains that the experience of harsh discipline causes children to develop biased hostile relational schemas and working models resulting in the development of future chronic conduct problems. Similarly, according to Wolfe and McIsaac’s (2011) continuum of parental emotional sensitivity and expression, coercive and emotionally abusive practices, including excessive criticism and verbal harassment, are believed to undermine children’s sense of self and their representations of healthy relationships and hamper the development of emotion regulation skills.

Undeniably, the research revealing the relation between verbal punishment and psychosocial problems is compelling and suggests that the use of harsh words can be equally or more harmful than using physical force (Evans et al., 2012).

Parental Warmth as Moderator

The psychosocial functioning and development of children and adults is determined significantly by the overall quality of the parent-child relationship (Rohner & Veneziano, 2001). Children respond to the experience of being loved or unloved by their parents (Rohner & Khaleque, 2010). Rohner’s parental acceptance-rejection theory (PARTheory) postulates that child adjustment is largely dependent on children’s perceived acceptance or rejection by their parents (Rohner & Khaleque, 2010). Parental acceptance and rejection comprise the warmth dimension of the PARTheory, which has to do with the “quality of the affectional relationship between parents and their children and with the physical, verbal and symbolic behaviors parents use… to express these feelings and behaviors” (Rohner, 2004, p. 2). Perceptions of parental acceptance or warmth are associated with physical and psychological health, social competence, and the internalization of parental values (Rohner & Veneziano, 2001). Children who perceive rejection, on the other hand, are marked by the absence of parental warmth, nurturance, support, or love, are more likely to develop problems like the inability to manage aggression and hostility, negative self-esteem, and emotional instability (Rohner & Khaleque, 2010).

Of particular relevance to this study is the evidence suggesting that parental warmth moderates the relation between parenting practices and negative child outcomes (Rohner & Veneziano, 2001). More specifically, Deater-Deckard and Dodge (1997) maintain that if used in the context of a warm parent-child relationship, the detrimental effects of physical punishment would be decreased. Inversely, if physical discipline were used in the context of a cold parent-child relationship, its detrimental effects would be magnified. This position is consistent with Darling and Steinberg’s (1993) integrative parenting model, which asserts that the context within which parenting practices (including parental discipline) occur communicates the parent’s emotional attitude not only towards the child’s behavior but also towards the child. This quality of the parent-child relationship acts to diminish or intensify the effects of negative parenting practices in two ways: (a) transforming the nature of the parent-child interaction and (b) affecting the child’s openness to parental intervention.

McLoyd and Smith (2002), whose study showed support for this viewpoint, found that in the context of high maternal emotional support, spanking was not associated with increased problem behaviors. However, in the context of low maternal support, spanking was associated with problem behaviors over time. Likewise, Deater-Deckard, Ivy, and Petril (2006) discovered that among low warmth mother-child dyads, harsher discipline was positively linked with greater externalizing problems. Among the high warmth mother-child dyads however, these associations were almost always nonsignificant. Notably, these results were similar among biological and adoptive mother-child pairs.

However, most research where warmth as moderator is considered explores its relation with physical punishment (see Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Deater-Deckard et al., 2006; McLoyd & Smith, 2002). Although it is likely that this same principle will apply to other forms of harsh discipline (Lansford et al., 2010), differential relations with parental warmth across the various forms of punishment and child outcomes may exist. Mckee et al. (2007) for instance found that parental warmth moderated the detrimental effects of harsh physical punishment on internalizing and externalizing behaviors in children but not the effects of harsh verbal punishment. Yet, the authors’ use of single items to measure both physical and verbal punishment, as well as the lower reported rates of physical punishment (as opposed to the higher rates of verbal punishment), might have affected the results of the investigation. This study intends to build on this work by focusing specifically on the moderating effect of parental warmth on the relation between verbal punishment and negative child outcomes.

Same-sex and Cross-sex Parent-child Groups

It is necessary to examine the role of gender in parent-child transactions as this variable often uncovers psychological processes that are not otherwise detected especially when the genders of both parent and child are considered (Chang et al., 2003). To illustrate, in socialization processes, parents naturally serve as role models to their children (Vanassche, Sodermans, Matthijs, & Swicegood, 2014). The social learning theory, from which this position was derived, proposes that gender aids the modeling effect in that a child would be more likely to look up to and emulate his/her same-sex parent (Bandura & Walters, 1959, as cited in Chang et al., 2003).

Applying this principle of modeling to parental discipline, Deater-Deckard and Dodge (1997) asserted that discipline events involving the same-sex parent and child will be more strongly represented and have greater impact compared to discipline events where the parent and child are of the opposite sex. They reported that mothers’ harsh discipline was more strongly correlated with externalizing problems of girls than of boys. Fathers’ harsh discipline was also more strongly correlated with externalizing problems of boys than of girls.

There is also evidence to suggest that parent and child gender play a role in facilitating the internalization of values through the overall quality of the parent-child relationship. Although some past studies proposed that parental warmth buffers the deleterious effects of harsh punishment (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Rohner & Veneziano, 2001), others have also highlighted the specific significance of parental warmth from the same-sex parent. For example, Vanassche et al. (2014) found that a good relationship with the same-sex parent lowers the likelihood of delinquent behavior. Conversely, Hoeve et al. (2009) reported that poor support of parents towards the same-sex child was more strongly associated to delinquency than poor support from the opposite-sex parent.

However, other studies also present contradicting results. For instance, Chang et al. (2003) found that while fathers’ harsh discipline was more strongly correlated with sons’ aggression than with daughters’, mother’s harsh discipline did not yield gender differential effects (see also Gershoff, 2002; Webster-Stratton, 1996). The authors argued that parental attachment, being relevant to the emotional channeling of harsh discipline (Chang et al., 2003), has not been found to vary as a function of child gender (Ainsworth, 1979). Furthermore, qualitative distinctions of parental treatment toward sons and daughters (i.e., sons experiencing more harsh discipline than daughters) as well as quantitative factors (i.e., amount of time fathers and mothers spend with children) could possibly account for the discrepancies in the literature (see Chang et al., 2003; Mckee et al., 2007). Ultimately, the role of parent and child gender in parent-child interactions still warrants further study.

Investigating the influence of parent and child gender in specific cultural contexts is beneficial as gender roles and expectations vary from one society to another. In their review of gender socialization in the Philippines, Liwag, de la Cruz, and Macapagal (1998) found that children are raised according to parents’ differential gender expectations, which run parallel to what society dictates as masculine or feminine. Liwag et al. (1998) also cited some studies that have documented the strong identification girls have with their mothers (i.e. Lapuz, 1987), and others that have reported tendencies of parents to form closer attachments to and favor their opposite-sex child (i.e. Mendez & Jocano, 1979; Ramirez, 1988). Thus, the very nature of childrearing in the Philippine context calls for a better understanding of the role of parent and child gender in socialization, particularly with regard to parental discipline and its effects.

The Present Study

The present study investigates the relationship between verbal punishment and child outcomes in three respects: (a) does parental verbal punishment predict the internalizing and externalizing behaviors of Filipino children; (b) does parental warmth moderate the relation between verbal punishment and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors; and (c) do main and moderating effects vary for same-sex and cross-sex parent-child groups?

It is hypothesized that: (a) verbal punishment predicts internalizing and externalizing behaviors in Filipino children, and (b) parental warmth moderates this relation by ameliorating the relation of verbal punishment to internalizing and externalizing behavior. No a priori hypothesis is proposed for the gender question, given the inconsistencies in the literature.

METHOD

Participants

The data for this study was taken from the Philippine sample of the first wave of the Parenting Across Cultures (PAC) project. To date, PAC is the largest longitudinal and cross-cultural investigation of different parenting dimensions and their subsequent effects on child development. One hundred seventeen mothers and 98 fathers of 120 children (61 males and 59 females) were recruited to participate in the first wave of data collection. To secure a fair representation of the urban Quezon City population, nonrandom quota sampling was utilized. Of the sample, 59% of the families came from the low-income demographic, 23% came from the mid-income demographic, and 18% came from the high-income demographic. Same-sex and cross-sex groups were comprised of 54 father-boy pairs, 44 father-girl pairs, 60 mother-boy pairs, and 57 mother-girl pairs. Mean ages for fathers, mothers and children were 40.24 (SD = 7.09), 37.93 (SD = 6.18), and 8.02 (SD = 0.34) respectively. All data were obtained from parent reports.

Procedure

Letters inviting parents to participate in the PAC project were sent to the parents of 8-year old Grade 2 and 3 students in 11 private and public schools in Quezon City. If parents indicated interest in their reply slips, they were called by trained research assistants to provide more information and schedule the structured interviews. Interviews with mothers and fathers were conducted mostly simultaneously, but separately with different interviewers. Parents signed consent forms before the interviews began. Respondents were given the choice to answer either the English or Filipino version of the questionnaires. The questions were orally administered to the respondents. Flash cards indicating the response scales were made available to aid them in answering. The interviews lasted about 1–2 hours. At the end of the interview, each parent was given a gift card for his or her participation.

Responses were encoded in an MS ACCESS database specially developed for the PAC project. Data were encoded twice by two different encoders to check for discrepancies in encoding. Data were then transferred to SPSS for analyses.

Measures

Verbal punishment

The Discipline Interview (DI; Lansford et al., 2005) assesses parents’ use of 18 specific discipline strategies. Frequency of use of each strategy was recorded using a 5-point Likert-scale (1 = never, 5 = almost everyday). The verbal punishment score was calculated by obtaining the mean frequencies of use of the following items: argue and quarrel with the child; raise (one’s) voice, yell, or scold the child; threaten to punish the child; scare the child into behaving; and telling the child he/she should be ashamed of himself/herself. Cronbach’s alphas for the mothers’ and fathers’ reports were .67 and .76, respectively.

Parental warmth

The 8-item Warmth and Affection subscale of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire (PARQ/Control) was used to measure parental warmth in the parent-child relationship (Rohner, 2005). Using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, 4 = everyday), parents were asked how well certain statements described the way they treated their children. Examples of items included in the subscale are “I say nice things about my child” and “I make my child feel wanted and needed.” Cronbach’s alpha for mothers’ reports was .57 while Cronbach’s alpha for the fathers’ reports was .65.

Internalizing and externalizing behaviors

Achenbach’s (1991) Child Behavior Checklist (CBC; short version) is a widely used 58-item parent-report measure of internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Internalizing behavior were determined by taking the sum of the items on the Withdrawn, Somatic, and Anxious/Depressed subscales while externalizing behaviors were determined by taking the sum of the items in the Delinquent and Aggressive subscales. Parents were asked to rate whether specific behaviors such as “worries a lot” (for internalizing) and “physically attacks others” (for externalizing), were “0 = not true”, “1 = sometimes true”, or “2 = very true” of their child in the last six months. Cronbach’s alphas for mothers’ and fathers’ reports of internalizing behavior were .88 and .87 while the alphas for mothers’ and fathers reports externalizing behavior were .86 and .88, respectively.

Overview of Analyses

Hierarchical regression analyses, following Aiken and West’s (1991) methods for analyzing interactions, were used to predict child internalizing and externalizing behavior from parent behavior. To guard against multicollinearity, mothers’ and fathers’ reports of verbal punishment and parental warmth were mean-centered (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Mean frequency of use of verbal punishment was entered in the model in the first step; mean parent-reported warmth was included in the second step; and at the third step, the cross-product of the centered variables (verbal punishment and warmth) was added to determine moderating effects. Separate models were analyzed for internalizing and externalizing child behavior outcomes and for same-sex and cross-sex parent-child groups. A total of eight regression models were generated. Given the large number of predictors and models that were analyzed, and given that the models are not independent (i.e., the subsamples of mothers, fathers, boys, and girls are used in more than 1 model) a Bonferroni correction was applied to control for Type I error. The alpha level of .05 was divided by the total number of models run, resulting in a critical p-value of .00625 that was applied to evaluate statistical results (Gelman, Hill, & Yajima, 2012).

RESULTS

Descriptive Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and Table 2 presents the correlations for the variables in this study. The means for mothers’ and fathers’ report of verbal punishment are similar and relatively low in frequency. With regard to parental warmth, the means of the mothers’ and fathers’ reports are similar and generally high. Independent samples t-tests were run to compare mothers’ and fathers’ reports of verbal punishment and parental warmth for male and female children. No significant differences were found between mothers’ and fathers’ use of verbal punishment and parental warmth with boys and girls. A significant difference was found, however, for father-reported externalizing behavior of boys and girls (t(96) = 2.147, p = .034), with boys being reported as exhibiting higher externalizing behavior.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations Among Variables With Respect to Same-sex and Cross-sex Groups

| Variable | N | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal Punishment- Father-Boys | 54 | 2.73 | 0.93 |

| Verbal Punishment- Father-Girls | 44 | 2.49 | 0.97 |

| Verbal Punishment- Mother-Boys | 60 | 2.89 | 0.81 |

| Verbal Punishment- Mother-Girls | 57 | 2.88 | 0.95 |

| Warmth- Father-Boys | 54 | 3.71 | 0.34 |

| Warmth - Father-Girls | 44 | 3.67 | 0.36 |

| Warmth - Mother-Boys | 60 | 3.78 | 0.26 |

| Warmth - Mother-Girls | 57 | 3.85 | 0.21 |

| Father-reported Internalizing - Boys | 54 | 10.31 | 7.30 |

| Father-reported Internalizing - Girls | 44 | 10.23 | 6.72 |

| Father-reported Externalizing - Boys | 54 | 13.48 | 8.42 |

| Father-reported Externalizing - Girls | 44 | 10.30 | 5.63 |

| Mother-reported Internalizing - Boys | 60 | 11.42 | 7.44 |

| Mother-reported Internalizing - Girls | 57 | 12.26 | 7.98 |

| Mother-reported Externalizing - Boys | 60 | 13.60 | 6.80 |

| Mother-reported Externalizing - Girls | 57 | 13.01 | 7.81 |

Table 2.

Correlations Among Verbal Punishment, Warmth, Internalizing Behavior and Externalizing Behavior With Respect to Mother and Father Reports

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Father verbal punishment | -- | |||||||

| 2. Mother verbal punishment | .210* | -- | ||||||

| 3. Father-warmth | .010 | .048 | -- | |||||

| 4. Mother-warmth | −.0230 | −.041 | .303** | -- | ||||

| 5. Father-report internalizing | .319** | .195 | −.263** | −.086 | -- | |||

| 6. Father-report externalizing | .360** | .180 | −.248* | −.278** | .645** | -- | ||

| 7. Mother-report internalizing | .172 | .552** | −.203* | −.155 | .342** | .240* | -- | |

| 8. Mother-report externalizing | .265** | .555** | −.195 | −.178 | .187 | .423** | .682** | -- |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01.

Positive correlations were found between fathers’ use of verbal punishment and father-reported internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Mothers’ use of verbal punishment was also positively correlated with mother-reported internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Father-reported warmth was negatively correlated with internalizing behavior and externalizing behavior. Mother-reported warmth was negatively correlated to father-reported externalizing behavior. Father-reported warmth was negatively correlated to father-reported internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Generally, associations among variables were as expected with the exception of the absence of a correlation between maternal warmth and mother-reported negative outcomes.

Predicting Externalizing Behavior in Boys and Girls

Model 1: Predicting boys’ externalizing behavior from fathers’ verbal punishment and warmth

The model statistics at each step are presented in Table 3. The final model, which included all predictor variables as well as the cross-product of father-reported warmth and verbal punishment, was significant (F(3, 50) = 4.749, p < .01) and explained about 22% of the variance (adjusted R2 = 17.5%) in the externalizing behavior of boys. Father-reported warmth significantly and negatively predicted boys’ externalizing behavior (β = −10.163, SE = 3.127, t(50) = −3.250, p < .00625). Fathers’ verbal punishment and the interaction between verbal punishment and warmth did not yield significant associations with boys’ externalizing behavior.

Table 3.

Model 1: Hierarchical Regression Predicting Boys’ Externalizing Behavior With Fathers’ Frequency of use of Verbal Punishment as Predictor and Father-reported Warmth as Moderating Variable

| Predictors | Boys’ Externalizing Behavior

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F(df) | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 2.145 | 1.216 | .238 | .056 | .056 | 3.112(1,52) |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 2.516 | 1.121 | .279 | .221 | .165 | 7.238(2,51)* |

| Father-reported Warmth | −10.168* | 3.097 | −.408 | |||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 2.373 | 1.322 | .263 | .222 | .001 | 4.749(3,50)* |

| Father-reported Warmth | −10.163* | 3.127 | −.408 | |||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment X Father-reported Warmth | 1.179 | 5.654 | .030 | |||

Note.

p < .00625.

Model 2: Predicting girls’ externalizing behavior from fathers’ verbal punishment and warmth

The final model was significant (F(3, 40) = 7.082, p < .00625) and explained approximately 35% (adjusted R = 29.8%) of the variance in girls’ externalizing behavior. Fathers’ use of verbal punishment significantly predicted girls’ externalizing behavior (β = .383, SE = .757, t(40) = 4.470, p < .00625). Fathers’ warmth did not significantly predict girls’ externalizing behavior and neither did it moderate the effect of verbal punishment on girls’ externalizing outcomes. See Table 4 for model statistics at each step.

Table 4.

Model 2: Hierarchical Regression Predicting Girls’ Externalizing Behavior With Fathers’ Frequency of Use of Verbal Punishment as Predictor and Father-reported Warmth as Moderator

| Predictors | Girls’ Externalizing Behavior

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F(df) | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 3.212* | .747 | .553 | .306 | .306 | 18.484(1,42)* |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 3.192* | .760 | .549 | .307 | .001 | 9.065(2,41)* |

| Father-reported Warmth | −0.503 | 2.055 | −.032 | |||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 0.383* | .757 | .582 | .347 | .040 | 7.082(3.40)* |

| Father-reported Warmth | −0.382 | 2.020 | −.024 | |||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment X Father-reported Warmth | −4.085 | 2.601 | −.203 | |||

Note.

p < .00625.

Model 3: Predicting boys’ externalizing behavior from mothers’ verbal punishment and warmth

The final model, where all predictor variables and interaction term were entered, was significant (F(3, 56) = 9.927, p < .00625) and explained about 34.7% (adjusted R = 31.2%) of the variance in boys’ externalizing behaviors. Mothers’ use of verbal punishment significantly predicted boys’ externalizing behavior (β = 4.920, SE = .913, t(56) = 5.391, p < .00625). Mothers’ warmth did not significantly predict boys’ externalizing behavior. Also, the interaction between mothers’ verbal punishment and warmth did not reach significance. Table 5 illustrates the model statistics at each step of the regression analysis.

Table 5.

Model 3: Hierarchical Regression Predicting Boys’ Externalizing Behavior With Mothers’ Frequency of Use of Verbal Punishment as Predictor and Mother-reported Warmth as Moderator

| Predictors | Boys’ Externalizing Behavior

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F(df) | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 4.804* | .906 | .571 | .327 | ..327 | 28.123(1,58)* |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 4.923* | .906 | .586 | .345 | .018 | 14.986(2,57)* |

| Mother-reported Warmth | −3.593 | 2.866 | −.135 | |||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 4.920* | .913 | .585 | .347 | .003 | 9.927(3,56)* |

| Mother-reported Warmth | −3.066 | 3.097 | −.115 | |||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment X Mother-reported Warmth | 2.014 | 4.293 | .054 | |||

Note.

p < .00625.

Model 4: Predicting girls’ externalizing behavior from mothers’ verbal punishment and warmth

Presented in Table 6 are the model statistics at each step of the regression analysis. The final model was significant (F(3, 53) = 13.634, p < .00625), explaining about 44% (adjusted R = 40.4%) of the variance in girls’ externalizing behavior. Mothers’ use of verbal punishment significantly predicted girls’ externalizing behavior (β = 4.068, SE = .871, t(53) = 4.672, p < .00625). Mother-reported warmth significantly moderated the relation between mothers’ use of verbal punishment and girls’ externalizing behavior (β = 12.466, SE = 3.939, t(53) = 3.165, p < .00625).

Table 6.

Model 4: Hierarchical Regression Predicting Girls’ Externalizing Behavior With Mothers’ Frequency of Use of Verbal Punishment as Predictor and Mother-reported Warmth as Moderator

| Predictors | Girls’ Externalizing Behavior

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F(df) | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 4.484* | .936 | .543 | .294 | .294 | 22.950(1,55)* |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 4.172* | .940 | .505 | .329 | .035 | 13.324(2,54)* |

| Mother-reported Warmth | −6.965 | 4.180 | −.190 | |||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 4.068* | .871 | .492 | .436 | .107 | 13.634(3,53)* |

| Mother-reported Warmth | −7.581 | 3.874 | −.206 | |||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment X Mother-reported Warmth | 12.466* | 3.939 | .327 | |||

Note.

p < .00625.

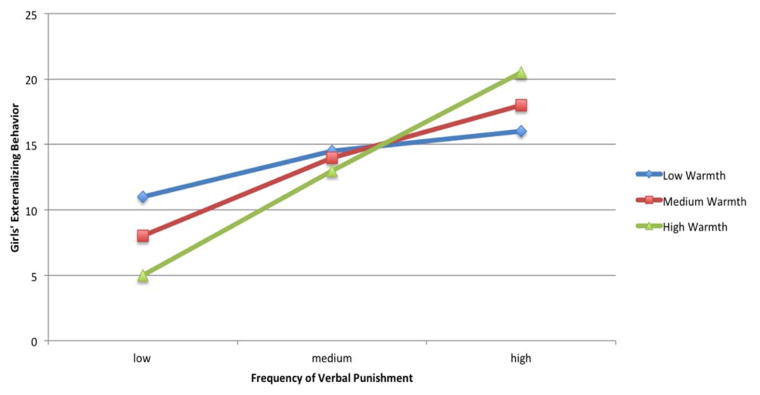

To interpret the interaction, girls’ externalizing behavior was plotted at low, medium, and high levels of mothers’ frequency of use of verbal punishment and mother-reported warmth (see Figure 1). Simple slopes analysis revealed that the association between mothers’ frequency of use of verbal punishment and girls’ externalizing behavior was significant at high levels of mother-reported warmth (t(53) = 5.669, p < .00625). Specifically, low frequencies of mothers’ verbal punishment resulted in girls’ lower externalizing behavior when maternal warmth was high. However, higher frequencies of mothers’ verbal punishment resulted in higher externalizing behavior in girls even when maternal warmth was high.

Figure 1.

The relation between mothers’ frequency of use of verbal punishment and girls’ externalizing behavior as a function of maternal warmth and affetion.

Predicting Internalizing Behavior in Boys and Girls

Model 5: Predicting boys’ internalizing behavior from fathers’ verbal punishment and warmth

Table 7 presents the model statistics at each step of the regression analysis. The third step, which included all predictor variables as well as the cross-product of father-reported warmth and verbal punishment, was significant (F(3, 50) = 5.143, p < .00625), and explained approximately 24% of the variance in boys’ internalizing behavior (adjusted R = 19.0%). Fathers’ use of verbal punishment did not predict boys’ internalizing behaviors. Father-reported warmth significantly and negatively predicted boys’ internalizing behavior (β = −8.255, SE = 2.683, t(50) = −3.076, p < .00625). Father warmth did not significantly moderate the relation between verbal punishment and internalizing outcomes.

Table 7.

Model 5: Hierarchical Regression Predicting Boys’ Internalizing Behavior with Fathers’ Frequency of Use of Verbal Punishment as Predictor and Father-reported Warmth as Moderating Variable

| Predictors | Boys’ Internalizing Behavior

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F(df) | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 2.300 | 1.036 | .294 | .087 | .087 | 4.928(1,52) |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 2.601 | .965 | .333 | .231 | .144 | 7.650(2,51)* |

| Father-reported Warmth | −8.243* | 2.666 | −.382 | |||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 2.938 | 1.135 | .376 | .236 | .005 | 5.143(3,50)* |

| Father-reported Warmth | −8.255* | 2.683 | −.382 | |||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment X Father-reported Warmth | −2.788 | 4.853 | −.083 | |||

Note.

p < .00625.

Model 6: Predicting girls’ internalizing behavior from fathers’ verbal punishment and warmth

The final model for predicting internalizing behavior with respect to the fathers-girls group was not significant. Fathers’ use of verbal punishment and warmth did not significantly predict girls’ internalizing behavior. Likewise, father-reported warmth did not significantly moderate this relation. See Table 8 for model statistics at each step.

Table 8.

Model 6: Hierarchical Regression Predicting Girls’ Internalizing Behavior with Fathers’ Frequency of Use of Verbal Punishment as Predictor and Father-reported Warmth as Moderating Variable

| Predictors | Girls’ Internalizing Behavior

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F(df) | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 2.472 | .998 | .357 | .127 | .127 | 6.129(1,42) |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 2.380 | 1.008 | .344 | .142 | .015 | 3.391(2,41) |

| Father-reported Warmth | −2.275 | 2.724 | −.122 | |||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 2.632 | 1.004 | .380 | .192 | .050 | 3.158(3,40) |

| Father-reported Warmth | −2.114 | 2.679 | −.113 | |||

| Fathers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment X Father-reported Warmth | −5.402 | 3.449 | −.226 | |||

Note.

p < .00625.

Model 7: Predicting boys’ internalizing behavior from mothers’ verbal punishment and warmth

Table 9 presents the model statistics for each step of the analysis. The final model, where all predictor variables and the cross-product of mother-reported warmth and verbal punishment were entered, was significant (F(3, 56) = 10.939, p < .00625) and explained around 37% (adjusted R=33.6%) of the variance in boys’ internalizing behavior. Mothers’ use of verbal punishment was found to be a significant predictor (β = 5.429, SE= .982, t(56) = 5.529, p < .00625) of internalizing behavior in boys. Mothers’ warmth did not predict internalizing behavior nor did it moderate the relation between verbal punishment and boys’ internalizing behavior.

Table 9.

Model 7: Hierarchical Regression Predicting Boys’ Internalizing Behavior with Mothers’ Frequency of Use of Verbal Punishment as Predictor and Mother-reported Warmth as Moderator

| Predictors | Boys’ Internalizing Behavior

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F(df) | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 5.220* | .995 | .567 | .322 | .322 | 27.511(1,58)* |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 5.430* | .973 | .590 | .369 | .047 | 16.679(2,57)* |

| Mother-reported Warmth | −6.372 | 3.078 | −.219 | |||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 5.429* | .982 | .590 | .369 | .000 | 10.939(3,56)* |

| Mother-reported Warmth | −6.173 | 3.331 | −.212 | |||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment X Mother-reported Warmth | 0.762 | 4.617 | .019 | |||

Note.

p < .00625.

Model 8: Predicting girls’ internalizing behavior from mothers’ verbal punishment and warmth

The final model, which included all predictor variables as well as the cross-product between mother-reported warmth and verbal punishment, significantly explained about 40% (adjusted R = 36.4%) of the variance in girls’ internalizing behavior (F(3, 53) = 11.675, p < .00625). Mothers’ use of verbal punishment significantly predicted girls’ internalizing behavior (β = 4.361, SE = .918, t(53) = 4.751, p < .00625) and mother-reported warmth significantly moderated this relation (β = 12.230, SE = 4.153, t(53) = 2.945, p < .00625). Table 10 shows the model statistics at each step of the regression analysis.

Table 10.

Model 8: Hierarchical Regression Predicting Girls’ Internalizing Behavior with Mothers’ Frequency of Use of Verbal Punishment as Predictor and Mother-reported Warmth as Moderator

| Predictors | Girls’ Internalizing Behavior

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | R2 | ΔR2 | F(df) | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 4.580* | .955 | .543 | .295 | .295 | 22.990(1,55)* |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 4.464* | .980 | .529 | .299 | .005 | 11.538(2,54)* |

| Mother-reported Warmth | −2.600 | 4.360 | −.069 | |||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment | 4.361* | .918 | .517 | .398 | .099 | 11.675(3,53)* |

| Mother-reported Warmth | −3.204 | 4.085 | −.085 | |||

| Mothers’ Frequency of Verbal Punishment X Mother-reported Warmth | 12.230* | 4.153 | .314 | |||

Note.

p < .00625.

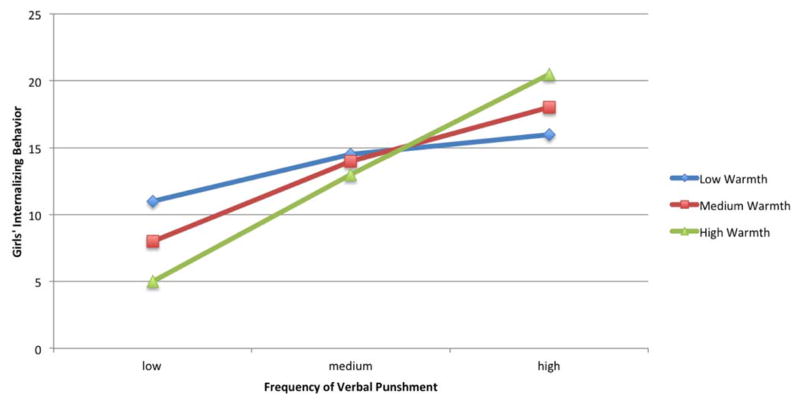

Girls’ internalizing behavior was plotted at low, medium, and high levels of mothers’ frequency of use of verbal punishment and mother-reported warmth (Figure 2). Again, the use of a simple slopes analysis revealed that the association between mothers’ frequency of use of verbal punishment and girls’ internalizing behavior was significant at high levels of mother-reported warmth (t(53) = 5.571, p < .00625) to interpret the interaction effect. Similar to the results for externalizing behavior, it was found that low frequencies of mothers’ use of verbal punishment resulted in lower internalizing behavior in girls when maternal warmth was high. However, high frequencies of mothers’ use of verbal punishment resulted in higher externalizing behavior in daughters when levels of maternal warmth were high.

Figure 2.

The relation between mothers’ frequency of use of verbal punishment and girls’ internalizing behavior as a function of maternal warmth and affetion.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to examine the relation of parental verbal punishment and externalizing and internalizing behaviors of Filipino children, the moderating role of parental warmth, and whether relations differed according to parents’ and children’s gender (same or opposite-sex). Seven out of the eight regression models produced significant results in predicting negative outcomes for boys and girls from frequency of verbal punishment. Moderating effects of parental warmth were found for the mothers and girls group for both internalizing and externalizing behavior.

Parental Verbal Punishment Predicts Negative Child Outcomes

Models 2, 3, 4, 7, and 8 supported the first hypothesis. Mothers’ use of verbal punishment predicted internalizing and externalizing behaviors in both girls and boys, while fathers’ use of verbal punishment predicted girls’ externalizing behavior. These results are consistent with past research such as that of Vissing et al. (1991), who found strong positive correlations between verbally aggressive parents and children who are physically aggressive, delinquent, or experience interpersonal problems (see also Hutchinson & Mueller, 2008; Teicher et al., 2006). These results also corroborate theoretical perspectives which assert that parenting practices that include the use of coercion, threats, insults, and frightening tone, increase the risk of child maltreatment and “sets the stage for similar patterns in subsequent relationships” (Wolfe & McIsaac, 2011, p. 4). Negative verbal interactions, and the corresponding negative affect and poor communication strategies learned from parents, are detrimental to the development of emotion regulation and influence children’s interactions with their peers (Parke et al., 1992, as cited in Chang et al., 2003). Such processes set the stage for the development of biased and hostile relational schemas and externalizing behaviors (Dodge & Pettit, 2003; Wolfe & McIsaac, 2011).

More specific to internalizing behavior, the propositions of attachment theory are consistent with the findings in that verbal punishment represents an inappropriate parental response that shapes children’s view of themselves as unlovable and the world as untrustworthy and unpredictable (Wu, 2007). Such negative representational models of oneself and others result in poorer social adjustment, lower self-esteem, and perceived incompetence (Toth & Cicchetti, 1996). It must be emphasized that children’s views of themselves are largely dependent on what significant others say about them (Carandang & Lee-Chua, 2008). This development of self-concept will in turn determine the kind of attitude with which they will face the world (Carandang & Lee-Chua, 2008). Hence, the messages and labels given to children are what they identify themselves with and eventually live out (Vissing et al., 1991).

Differing Results for Same-Sex and Cross-Sex Groups

That mothers’ verbal punishment significantly predicted both girls and boys’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors highlights the importance of maternal parenting. Generally, a mother’s relationship with her child predates other social relationships (Bowlby, 1969, 1982, as cited in Toth & Cicchetti, 1996) and up until middle childhood, mothers spend more time parenting their children than fathers (Russell & Russell, 1987). Moreover, perhaps due to the fact that boys and girls have similar needs from infancy to early childhood, mothers’ attitudes and behaviors toward children are less dependent on child gender (Maccoby, 1992). Thus, the mother-child relationship is particularly salient in the development of children’s working models for future interactions with others (Bowlby, 1969/1982, as cited in Toth & Cicchetti, 1996).

On the other hand, fathers’ use of verbal punishment predicted girls’ externalizing behavior, but was not associated with boys’ negative outcomes. The result for girls is consistent with Hart et al. (1998; as cited in Chang et al., 2003), who found that father coercion was more strongly associated with girls’ overt aggression compared to sons. It might be that females’ relatively greater tendency to attend to relationships and emotional cues (Gilligan, 2005), in part, explain the evident effects of verbal punishment from both mothers and fathers on girls’ outcomes.

That fathers’ verbal punishment did not predict boys’ negative outcomes runs contrary to previous research. It must be borne in mind that children’s reactions to parental discipline are influenced by their interpretations of the discipline event (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997). In the Philippines, boys are generally expected to occupy roles of authority in the household and society whereas females are viewed as more delicate and in need of protection (Garo-Santiago, Mansukhani, & Resurreccion, 2009). This perception may lead parents and children to believe that sons must toughen up in order to be strong and responsible adults in the future (Sanapo & Nakamura, 2011). Indeed, Filipino fathers were found to be more punitive compared to mothers and boys were found to receive more harsh punishment than girls (Sanapo & Nakamura, 2011). Thus, perhaps, the lack of associations among paternal verbal punishment and boys’ negative outcomes is due to the acceptance and normativeness of harsher punishment from fathers.

The Moderating Role of Maternal Warmth for Girls

The moderating role of warmth on the relation between parental verbal punishment and negative outcomes was evident only for mothers and girls. Girls’ sensitivity towards relational cues (Gilligan, 2005), as well as gender role modeling, may cause them to be more sensitive to how they are treated especially by their mothers (Reinert & Edwards, 2009). Filipino mothers and daughters have been noted to develop very close relationships, with daughters often modeling their mothers’ behaviors (Lapuz, 1987, as cited in Liwag et al., 1998).

The data revealed that mothers’ high warmth resulted in girls’ lower internalizing and externalizing behaviors when levels of verbal punishment were low. This result extends previous research in that a warm relationship between mothers and daughters decreases the negative effects of not only physical punishment, but also mild verbal punishment.

This effect, however, is considered alongside the finding that high maternal warmth exacerbates the effects of high verbal punishment on girls’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Perhaps this reflects inconsistencies in parenting practices and parenting styles (i.e., warm mother but also verbally punishing mother), which strain the security of the parent-child relationship and leave the child susceptible to later problems (O’Gorman, 2012). Consistency in caregiving has been linked to the development of self-control and compliance to social rules (Schaffer, 1996; as cited in Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). On the other hand, anti-social children have often been found to have a history of harsh, rejecting, and inconsistent parenting (Coie & Dodge, 1998, as cited in Masten & Coatsworth, 1998).

Another possible explanation for the aggravated effects of verbal punishment in the context of high parental warmth among mothers and girls may also be found in social learning theory. Straus and Gelles as as well as Straus and Smith have proposed that parenting behavior teaches children about how to treat and be treated by those they love (as cited in Simons, Simons, Lei, Hancock, & Fincham 2012). Though experiences of hostility in the context of a cold parent-child relationship may serve as a model for distant affiliations, experiences of hostility in the context of a warm parent-child relationship may communicate that negative behaviors (such as aggression) are normative in loving relationships (Simons et al., 2012). Moreover, because imitation more likely occurs when the observer identifies with the person modeling the behavior, children who feel a bond or attachment toward their parents will naturally be more likely to emulate them (Simons et al., 2012). Hence, when a parent is both highly warm and highly punitive, it would be reasonable to suppose that internalizing and externalizing behaviors in the child would intensify.

The Role of Paternal Warmth on Boys

An unexpected result is that father-reported warmth did not significantly moderate the association between verbal punishment and boys’ and girls’ negative outcomes.

However, higher paternal warmth (but not maternal warmth) predicted lower internalizing and externalizing behaviors in boys (but not girls). This is notable moreso because Filipino fathers are more emotionally distant with sons (Lapuz, 1987, as cited in Liwag et al., 1998) and generally spend less time with their children (NFO-Trends, 2001). These results require further study to corroborate, but certainly support the idea that both paternal and maternal parenting behaviors significantly influence child outcomes uniquely (Rohner & Veneziano, 2001).

Limitations and Recommendations

The sample was divided into same-sex and cross-sex groups, thereby reducing the sample size for each regression analysis and decreasing statistical power. Moreover, the application of the Bonferroni adjustment may have increased the likelihood of Type II error. Examining within-family relations (i.e., parent-child same-sex or cross-sex dyads within families) would provide a more nuanced perspective on the role of gender role identification and socialization processes on the relations examined here, analyses which would entail multilevel modeling.

Causal conclusions are not warranted given that a correlational design was used. Longitudinal designs would bolster the evidence that harsh verbal punishment predicts subsequent behavior problems in children. Low internal consistencies of the Warmth and Affection subscale of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire qualifies the results and limits generalizations based solely on the results of this study. This paper also made use of only parent reports to test the hypotheses; it is recommended that future studies examine parental discipline and problem behaviors from the children’s points of view.

Conclusions

In sum, the use of verbal punishment is significantly associated with negative outcomes in children. Children who are exposed to verbal punishment (from mothers for both girls and boys, and from the fathers for girls) exhibit higher behavioral problems. High maternal warmth was found to buffer the negative effects of low verbal punishment for girls, but it was also found to exacerbate the negative effects of high verbal punishment.

Results are nuanced by the sex of the parent and child. The direct effect of paternal warmth on boys’ outcomes, the absence of associations with paternal verbal punishment (for boys), and the absence of moderating effects for paternal warmth might be explained by the delineation of expected gender and societal roles and responsibilities of Filipino mothers and fathers and boys and girls, as well as the sensitivity of females to emotional and relational cues. These propositions require further study.

This paper builds on previous work in a number of ways. In exploring same-sex and cross-sex parent-child groups, this study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the relations among verbal punishment, parental warmth, gender, and child outcomes in the Philippine context. Specifically, it was found that the use of verbal punishment, regardless of the sex of the parent, is detrimental to positive child development. This complements the extant literature on the negative effects of physical punishment. The nature of the moderating effect of parental warmth in connection with high verbal punishment and child outcomes reinforces the necessity to eliminate or at least decrease experiences of verbal punishment. Parenting programs would do well to educate mothers and fathers about the ill effects of the use of verbal punishment, as well as emphasize the importance of cultivating a warm parent-child relationship.

Acknowledgments

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [Grant RO1-HD054805]. We thank the families who participated in the study.

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL 14–18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist. 1979;34:932–937. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.34.10.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alampay L, Jocson R. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in the Philippines. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11:163–176. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin L, Ispa J, Fine M, Malone P, Brooks-Gunn J, Brady-Smith C, Bai Y. Correlates and consequences of spanking and verbal punishment for low-income White, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development. 2009;80(5):1403–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbach A, Fox R, Nicholson B. Challenging behaviors in young children: The fathers’ role. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2004;165(2):169–183. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.165.2.169-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carandang MLA, Lee-Chua Q. The Filipino family surviving the world. Pasig City, Philippines: Anvil; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Dodge K, Schwartz D, Mcbride-Chang C. Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(4):598–606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Grusec J, Wolfe J. Mothers’ knowledge of their children’s evaluations of discipline: The role of type of discipline and misdeed, and parenting practices. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2012;59(3):314–340. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge K. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8(3):161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Ivy L, Petril S. Maternal warmth moderates the link between physical punishment and child externalizing problems: A Parent-offspring behavior genetic analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2006;6(1):59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge K, Pettit G. A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(2):349–371. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban E. Parental verbal abuse: Culture-specific coping behavior of college students in the Philippines. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2005;36(3):243–259. doi: 10.1007/s10578-005-0001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Simons L, Simons R. The effect of corporal punishment and verbal abuse on delinquency: Mediating mechanisms. Journal of Youth Adolescence. 2012;41:1095–1110. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9755-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garo-Santiago MA, Mansukhani R, Resurreccion R. Adolescent identity in the context of the Filipino family. Philippine Journal of Psychology. 2009;42(2):175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Hill J, Yajima M. Why we (usually) don’t have to worry about multiple comparisons. Journal of Research on Education Effectiveness. 2012;5:189–211. doi: 10.1080/19345747.2011.618213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(4):539–579. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.128.4539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Lansford J, Chang L, Zelli A, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge K. Parent discipline practices in an international sample: Associations with child behaviors and moderation by perceived normativeness. Child Development. 2010;81(2):487–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. From a different voice to the birth of pleasure: An intellectual journey. Paper presented at the University of Milan; Milan, Italy. 2005. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas J, Eichelsheim V, van der Laan P, Smeenk W, Gerris J. The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-0099310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson L, Mueller D. Sticks and stones and broken bones: The influence of parental verbal abuse on peer related victimization. Western Criminology Review. 2008;9(1):17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Chang L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Palmerus K, Quinn N. Physical discipline and children’s adjustment: Cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development. 2005;76:1234–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford J, Malone P, Dodge K, Chang L, Chaudary N, Tapanya S, Deater-Deckard K. Children’s perceptions of maternal hostility as mediator of the link between discipline and children’s adjustment in four countries. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34(5):452–461. doi: 10.1177/0165025409254933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liwag EC, De La Cruz AS, Macapagal ME. How we raise our daughters and sons: Child-rearing and gender socialization in the Philippines. Philippine Journal of Psychology. 1998;31:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E. The role of parents in the socialization of children: An historical overview. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28(6):1006–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Masten A, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckee L, Roland E, Coffelt N, Olson A, Forehand R, Massari C, Zens M. Harsh discipline and child problem behaviors: The roles of positive parenting and gender. Springer Science + Business Media. 2007;22:187–296. doi: 10.1016/j.avv.2008.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V, Smith J. Physical discipline and behavior problems in african american, european american, and hispanic children: Emotional support as a moderator. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:40–53. [Google Scholar]

- NFO-Trends. Youth study 2001. Manila: Society of Jesus; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- O’Gorman S. Attachment theory, family system theory, and the child presenting with significant behavioral concerns. Journal of Systemic Therapies. 2012;31(3):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert D, Edwards C. Childhood physical and verbal mistreatment, psychological symptoms, and substance abuse: Sex differences and the moderating role of attachment. Journal of Family Violence. 2009;24:589–596. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9257-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner R. The parental “acceptance-rejection” syndrome: Universal correlates of perceived rejection. American Psychologist. 2004;59(8):830–840. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner R. Parental acceptance-rejection/control questionnaire (PARQ/Control): Test manual. In: Rohner RP, Khaleque A, editors. Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection. 4. Storrs, CT: Center for the Study of Parental Acceptance and Rejection, University of Connecticut; 2005. pp. 137–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner R, Khaleque A. Testing central postulates of Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory (PARTheory): A meta-analysis of cross-cultural studies. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2010;2:73–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00040.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner R, Veneziano R. The importance of father love: History and contemporary evidence. Review of General Psychology. 2001;3(4):382–405. doi: 10.1037//1089-2680.5.4.382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell G, Russell A. Mother-child and father-child relationships in middle childhood. Child Development. 1987;58:1573–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Sanapo M, Nakamura Y. Gender and physical punishment: The Filipino children’s experience. Child Abuse Review. 2011;20:39–56. doi: 10.1002/car.1148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LG, Simons RL, Lei M, Hancock DL, Fincham FD. Parental warmth amplifies the negative effect of parental hostility on dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(13):2603–2626. doi: 10.1177/0886260512436387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- TAMBAYAN . Kuyaw! Street adolescents in street gangs in Davao City. Davao; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Teicher M, Samson J, Polcari A, McGreenery C. Sticks, stones, and hurtful words: Relative effects of various forms of childhood maltreatment. American Journal of Psychology. 2006;163:993–1000. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth S, Cicchetti D. Patterns of relatedness, depressive symptomatology, and perceived competence in maltreated children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(1):32–41. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanassche S, Sodermans AK, Matthijs K, Swicegood G. The effect of family type, family relationships and parental role models on delinquency and alcohol use among Flemish adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23:128–143. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9699-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vissing Y, Straus M, Gelles R, Harrop J. Verbal aggression by parents and psychosocial problems of children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1991;15:223–238. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90067-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MT, Kenny S. Longitudinal links between fathers’ and mothers’ harsh verbal discipline and adolescents’ conduct problems and depressive symptoms. Child Development. 2013;85(3):908–923. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Early-onset conduct problems: Does gender make a difference? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(3):540–551. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, McIsaac C. Distinguishing between poor/dysfunctional parenting and child emotional maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2011;35:802–813. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. The interlocking trajectories between negative parenting practices and adolescent depressive symptoms. Current Sociology. 2007;55:579–597. doi: 10.1177/00113921070776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]