Abstract

Individuals with serious mental illnesses suffer from obesity and cardiometabolic diseases at high rates, and antipsychotic medications exacerbate these conditions. While studies have shown weight loss and lifestyle interventions can be effective in this population, few have assessed intervention cost-effectiveness. We present results from a 12-month randomized controlled trial that reduced weight, fasting glucose, and medical hospitalizations in intervention participants. Costs per participant ranged from $4,365 to $5,687. Costs to reduce weight by one kilogram ranged from $1,623 to $2,114; costs to reduce fasting glucose by one mg/dL ranged from $467 to $608. Medical hospitalization costs were reduced by $137,500.

Keywords: economic evaluation, behavioral intervention, randomized controlled trial, serious mental illness, weight loss, glucose control

Introduction

Individuals diagnosed with serious mental illnesses are at increased risk of obesity- and cardiovascular-related early morbidity and mortality (Colton & Manderscheid, 2006; Druss, Zhao, Von, Morrato, & Marcus, 2011; Kilbourne et al., 2009). This is complicated by the fact that the antipsychotic medications used to treat these disorders encourage weight gain (Chaggar, Shaw, & Williams, 2011) and metabolic disturbances (Malhotra et al., 2012; Newcomer, 2007). To address this pressing public health issue, researchers and clinicians have developed and tested behavioral trials to reduce obesity and its sequelae in this population. Two recent, large-scale trials of behavioral lifestyle interventions to reduce weight and obesity-related risk factors, for example, have reported clinically significant weight loss among people with serious mental illnesses (Daumit et al., 2013; Green et al., 2015). These trial’s positive outcomes suggest that overweight and obese patients taking antipsychotic medications benefit from behavioral weight loss treatment and implementation in routine care settings is warranted.

Before these interventions can be implemented, however, program managers and policymakers need to fully understand the costs required to deliver the intervention as well as the cost-effectiveness of the intervention. Various cost and cost-effectiveness analyses of behavioral lifestyle interventions targeting populations without mental illnesses are available (e.g., Forster, Veerman, Barendregt, & Vos, 2011; Lehnert, Sonntag, Konnopka, Riedel-Heller, & Konig, 2012; Ritzwoller et al., 2011; Roux, Kuntz, Donaldson, & Goldie, 2006; Tsai et al., 2013). In the general population, for example, research has articulated that the costs associated with increased quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) range from $78K to $148K (2015 dollars) for people with diabetes (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, 2003) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) range from $4K to $123K (2015 dollars) (Lehnert et al., 2012). In contrast, we are aware of only one economic evaluation of an intervention targeting physical activity and weight loss among individuals with serious mental illnesses (Verhaeghe et al., 2014). Using a five-year horizon, Verhaeghe and colleagues reported ICERs ranging from €199K ($249K) to €278K ($348K) per QALY in 2015 dollars (dollar amounts from previous studies were adjusted for inflation [(inflation.eu, 2015; United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2007, 2015). When comparing results from diabetic and general populations with those reported by Verhaeghe and colleagues (2014), it appears that reducing overweight and obesity among people with serious mental illnesses may be more expensive than achieving the same results in the general population. Additional cost-effectiveness evaluations of lifestyle interventions are needed, particularly for those applying longer intervention duration and resulting in better outcomes.

To help fill this gap in the literature, we present the results of cost and cost-effectiveness analyses from the STRIDE study (Green et al., 2015). STRIDE was a randomized controlled trial that evaluated a comprehensive lifestyle intervention among individuals with serious mental illnesses who were taking antipsychotic medications. The intervention used the evidence-based PREMIER weight loss and lifestyle intervention with DASH eating plan (Funk et al., 2006; National Heart, 2006; Svetkey et al., 2003), adapted for people taking antipsychotic medications (Green et al., 2015; Yarborough, Janoff, Stevens, Kohler, & Green, 2011; Yarborough, Leo, Stumbo, Perrin, & Green, 2013). To our knowledge, this is only the second economic analysis of a lifestyle intervention in this population and is the only one that evaluates an intervention of long duration (12 months). This economic analysis provides information needed by decision-makers who are considering implementing STRIDE or other similar programs.

Methods

Settings

The intervention was conducted in two community mental health centers (Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare [Cascadia] and LifeWorks Northwest [LifeWorks]) and a not-for-profit health system (Kaiser Permanente Northwest [KPNW]). KPNW provides integrated medical and mental health care. KPNW members are insured and representative of the Portland, Oregon metropolitan area. Cascadia and LifeWorks provide mental health and addiction treatment and typically serve low-income individuals. Further details about the study protocol and the results are detailed elsewhere (Green et al., 2015; Yarborough et al., 2013). The KPNW Institutional Review Board reviewed, approved, and monitored the study.

Recruitment, Screening, and Randomization

The methods used in the STRIDE trial have been detailed elsewhere (Yarborough et al., 2013). Briefly, we invited individuals 18 years or older who were taking antipsychotic medications for at least 30 days prior to enrollment, and who had a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 27, to participate. We excluded those who were currently breastfeeding or planning a pregnancy, had unstable mental health defined as a psychiatric hospitalization within the past 30 days (although we allowed later participation once stability was achieved), had a history of or planned bariatric surgery, had cancer within the previous two years, had a stroke or heart attack within six months, or who had cognitive impairment that could interfere with consent or participation.

We conducted rolling recruitment (into 8 separate cohorts) from July 2009 through August 2011. Our final 24-month assessments concluded in October 2013. We used electronic medical records (EMRs) at KPNW and Cascadia to identify potential participants. Clinician referral identified these participants at LifeWorks. Initial inclusion criteria included antipsychotic medication use and BMI (if BMI was not available, we included individuals in the recruitment pool). We mailed recruitment letters to potential participants. We then contacted these individuals by telephone to obtain eligibility information and complete a brief inclusion screen. After that screening, we invited eligible participants to attend a group orientation session during which they consented to height and weight measurements. Finally, study staff confirmed BMI eligibility inclusion criteria before conducting full written consent with participants. Participants then attended a second eligibility visit to complete a fasting blood sample, take blood pressure readings, and measure waist circumference.

Participants were randomized to the usual care or intervention condition at the second screening visit after completing all baseline assessments. We used a stratified blocked randomization procedure within sites with gender and BMI categories (BMI = 27.0–34.9 or BMI ≥ 35) as the strata. Staff not involved in data collection informed participants about the results of randomization. Usual care participants received no further intervention, but did complete a physical assessment (i.e., blood pressure, weight, lab values) and completed questionnaires at six and 12 months.

Intervention design

STRIDE was based on: 1) guidelines for obesity treatment for individuals at risk for cardiovascular disease (Jensen et al., 2014) and 2) the PREMIER lifestyle intervention with DASH eating plan (Funk et al., 2006; Svetkey et al., 2003). The intervention’s goal was to reduce weight- and obesity-related risks through improved diet, moderate restriction of calories, and increased moderate physical activity. We tailored intervention content and delivery for people with serious mental illnesses by employing two facilitators (mental health counselor, nutritional interventionist) and using repetition, multiple teaching modalities (e.g., verbal, visual), skill-building exercises, and practice assignments to overcome cognitive barriers. We also linked intervention materials to mental health and added sessions that addressed: 1) effects of psychiatric medications on weight; 2) planning for psychiatric symptom exacerbation; 3) improving sleep; 4) eating healthfully on a budget; and 5) stress management. We also provided case management beyond what was provided as part of PREMIER to help our population stay engaged, particularly when they were experiencing symptom exacerbations or difficult life circumstances (Yarborough et al., 2011).

STRIDE’s core intervention comprised a series of weekly two-hour group meetings that included 20 minutes of physical activity and that were delivered over six months. An additional six months of monthly group meetings supported maintenance of behavior change and weight loss. Participants were taught to keep records of: 1) food, beverages, and calories consumed; 2) servings of fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products; 3) fiber and fat intake; 4) daily minutes exercised; and 5) hours slept each night. The intervention’s goals included: 25 minutes of moderate physical activity per day, primarily through walking; increased fruit, vegetable, and low-fat dairy consumption; and improved sleep quality. We used food, sleep and exercise logs to assess progress and identify barriers to lifestyle change. Interventionists reviewed records to help participants evaluate and modify goals and plans. Participants received a workbook to guide them through the program, a copy of the Calorie King: Calorie, Fat, & Carbohydrate Counter (Borushek, 2012), and a resistance band for strength training.

The first 24 intervention sessions (weekly) were designed to increase awareness of health-related practices through learning to self-monitor, creating personalized plans, reducing energy intake (reducing portions), increasing focus on low-calorie density foods, increasing physical activity (moderately), learning to manage high-risk eating situations (e.g., parties), keeping track of their progress (graphing), and explicitly addressing mental health and how it might affect change efforts. The next six sessions (intervention maintenance phase) included monthly group sessions that focused on maintaining weight loss and reinforcing health-related practices learned in the first six months. Continued problem-solving and motivational-enhancement skills were reviewed in these sessions. Monthly individual telephone consultations with group leaders were available if desired, but this option was seldom used.

Approach to analyses

Intervention cost-effectiveness is usually reported as an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which is the ratio of the change in costs between the intervention and a control condition over the change in outcome units, such as kilograms of weight lost, fasting glucose (mg/dL), or quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), between intervention and control participants. The ICER indicates the intervention cost per incremental outcome unit produced by the intervention, and is calculated as [Ci - Cc] /[Ei - Ec] where Ci (Cc) and Ei (Ec) are the costs and effectiveness associated with the intervention (or control) strategies. ICERs facilitate comparisons of projects or interventions across various disease states and treatments (Gold, Siegel, Russell, & Weinstein, 1996). Through the ICER, cost-effectiveness analysis indicates the tradeoffs involved in choosing among health care interventions, and gives decision makers in diverse settings important data for making informed judgments about interventions. Some policymakers believe that the use of CEA in health care decision making will lead to rationing, though this is not a deficiency of the method, but rather of its use.

Cost assessments

We assessed and assigned intervention costs based on well-established procedures used in previous studies (Gold et al., 1996; Meenan et al., 2009; Meenan et al., 1998; Meenan et al., 2010; Ritzwoller et al., 2013; Ritzwoller, Sukhanova, Gaglio, & Glasgow, 2009; Ritzwoller et al., 2011). Costs included interventionist training, participant recruitment, and intervention delivery. We excluded research-related costs and the costs of following participants for the second 12 months (i.e., to the 24-month assessment) because participants received no active intervention or contact during this period and, as such, this period did not differ from usual care.

Recruitment and enrollment costs

We report the actual recruitment costs associated with STRIDE even though they include the costs of recruiting the sample of 200 individuals, including control participants. We made the decision to include these costs because replicating this intervention within a large health system or clinical setting could require resources to identify and invite the patient population, which might include outreach to a larger number of participants than were recruited for this study.

Determining eligible participants at KPNW and Cascadia required data analysts to identify those who met inclusion criteria. At LifeWorks, clinician panel reports were printed and reviewed by clinicians to identify eligible participants, using the same enrollment criteria as were applied in the EMR-based systems. Counselors consulted with KPNW researchers to ensure that participants met enrollment criteria. Enrollment costs also included screening and review of inclusion criteria and medical safety at all sites, and reviewing and signing letters mailed to the initial 1,866 individuals. Of these, 739 refused participation, 511 screened ineligible by phone, and 208 were unreachable. Thus, 408 individuals were screened eligible by phone and invited to attend the first of two in-person orientation and screening visits. We enrolled and randomized 200 of these individuals. All recruitment costs following identification of eligible individuals were incurred at KPNW (e.g., phone screening, determining eligibility, screening visit). Non-labor costs included supplies, printing, and mailing costs. It is worth noting that less resource-intensive recruitment approaches would likely be used in many settings.

Intervention costs

A co-investigator who is an expert in weight loss interventions provided interventionist training. We report separate costs for the initial training (trainer and trainees), intervention delivery (30 sessions over 12 months for each of the eight rolling cohorts, 240 in total), and the ongoing interventionist supervision that was provided by three project team members. All 30 sessions for each cohort included two interventionists, a mental health counselor, and a counselor with relevant nutritional knowledge. The intervention could be delivered, however, by one person with appropriate training. For KPNW cohorts, both interventionists were KPNW employees. At community mental health clinics, one interventionist was a KPNW employee and one was a clinic employee. Labor costs were calculated as either direct KPNW employment or through subcontracts with community clinics.

Our non-labor costs included interventionist travel as cohorts were conducted across the Portland, Oregon metropolitan area. Additional non-labor costs included supplies (pens, markers, nametag and flipcharts for the sessions, digital scales for weigh-ins, food for demonstrations, inexpensive calculators, exercise bands, and Calorie King books (Borushek, 2012)), printing (200+ pages per participant), and additional postage to remain in contact by sending participants birthday cards. During the active intervention, detailed interventionist logs were kept on time spent coordinating activities with participants (e.g., emailing, calling, and reviewing dietary/activity/sleep logs). We included three additional hours per week for each interventionist to account for interventionist check-ins regarding intervention progress, follow up with participants and processing case notes, and to participate in supervisory meetings with study investigators. One hour of check-in between the mental health and nutritional interventionists was typically conducted in tandem with the regularly scheduled two-hour intervention session (i.e., 30 minutes prior to and following each meeting).

Participant costs

We calculated participant costs using both estimated and directly reported data. First, an average distance of five miles traveled to an intervention session (ten miles round-trip) was assumed based on experience with the population and their proximity to session locations located across the metropolitan area. The value of intervention time based on lost work hours was calculated using the STRIDE baseline data, which showed that one-third of participants were employed. Lost wages were calculated using the average national wage rate (United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics), and we applied 30% of this wage rate to non-working individuals, which is consistent with other economic evaluations (Ritzwoller et al., 2011).

Second, participants reported costs directly on questionnaires at baseline, six months, and 12 months. Participants were asked about average monthly expenditures on 1) self-help materials (e.g., books, videos, or audio recordings); 2) special foods, (e.g., new vegetables added to their diet); 3) vitamins or other dietary supplements (e.g., herbs or teas); and 4) exercise-related costs (e.g., joining a gym or buying new equipment). We summed these reported costs across the four categories. Caregiver resources affected by the intervention were not included because they were considered minimal—most participants traveled to intervention sessions on their own, and changes in meal preparation time by caregivers were expected to be minimal. When we compared the costs reported at the six-month survey with reported baseline costs, only differences between intervention and control participants, and between six months and baseline, were attributable to the intervention. We then multiplied this difference by six (as costs were reported as a monthly average) and again by the number of intervention participants. This gave us the total six-month participant-reported costs. We used the same method for costs associated with 12-month reports (e.g., expenditures from months 7-12 of study participation). Finally, participant savings were similarly collected using a questionnaire item that asked participants if they had reduced or eliminated anything from their lifestyle to maintain good health (e.g. junk food, alcohol, tobacco). We calculated associated monthly savings from those reported changes.

Analytic Framework

While the main economic evaluation presented here is a cost-effectiveness analysis from a health system/payer perspective, we also include participant costs in order to provide a societal perspective. We estimated the ICERs for the study outcomes of weight lost (in kilograms) and reduced fasting glucose levels (in mg/dL). We also examined EQ-5D (EuroQol Group, 2014) change scores between intervention and control groups at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. These scores did not differ statistically at any time point. We also performed univariate sensitivity analyses to examine the influence of uncertainty associated with the measures and the assumptions used in the analysis and generated tornado diagrams based on the study outcomes (Briggs, 2000; Manning, Fryback, & Weinstein, 1996).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the costs of implementing the intervention. Intervention labor is separated into recruitment and delivery activities. We included the labor costs for identifying the initial population as a recruitment cost. Total direct implementation cost was $374K, 95% of which was labor. The interventionist labor alone was 62% of the labor costs. Applying the 58% overhead rate of our research center, the total system-related implementation cost was $591K.

Table 1. Intervention costs and participant cost components.

| Cost domain | Costs | Sub-total | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Program labor | |||

| Recruitment | |||

| Identification of participant pool | $ 20,848 | ||

| Participant contact activities | $ 49,663 | ||

| Recruitment labor subtotal | $ 70,511 | ||

| Intervention delivery | |||

| Training (trainer and trainees) | $ 21,422 | ||

| Interventionist labor | $ 231,720 | ||

| Interventionist supervision | $ 31,974 | ||

| Intervention delivery labor subtotal | $ 285,116 | ||

| Program non-labor | |||

| Interventionist travel | $ 1,359 | ||

| Supplies | $ 10,934 | ||

| Postage | $ 6,397 | ||

| Program non-labor subtotal | $18,690 | ||

| Direct intervention costs | $ 374,317 | ||

| Overhead rate (58%) | $ 217,104 | ||

| Total intervention costs | $ 591,421 | ||

| Value of reduced hospitalizations1 | $ (137,500) | ||

| Total system-related intervention costs | $ 453,921 | ||

| Costs incurred by participants | |||

| Travel costs (financial) | $ 17,472 | ||

| Travel costs (time) | $ 35,440 | ||

| Time in intervention sessions | $ 70,880 | ||

| Other costs (e.g., purchasing exercise equipment) |

$2,851 | ||

| Savings from reduced resource use (e.g., less junk food) |

$ (9,251) | ||

| Participant costs subtotal | $ 117,392 | ||

| Total societal costs of intervention | $ 571,313 |

Value of reduced medical hospitalizations is based on the difference between intervention and control groups and between baseline and 12 months. Intervention participants experienced 11 fewer medically-related hospitalizations during the first 12 months than control participants. The savings are calculated from the H-CUP website using the most recent (2011) estimates.

We observed a statistically significant reduction in hospitalizations between intervention and control participants over the study period. While psychiatric hospitalizations did not differ over the study period, the intervention participants experienced 11 fewer medical hospitalizations than control participants (7 vs. 18) during the 12 active intervention months (Green et al., 2015). This finding echoes those of other intensive lifestyle interventions (Espeland et al., 2014). Crediting the intervention with the value of these reduced hospitalizations lowered the system-related intervention cost by $137,500 based on an external cost estimate for an average hospital stay (Pfuntner, Wier, & Steiner, 2013). Notably, reduced hospitalizations continued over the 12 months following the active intervention period (months 13-24), although these were not included in this 12-month analysis. Intervention participants again experienced 11 fewer hospitalizations compared with controls (5 vs. 16), leading to an estimated savings of an additional $137.5K (not included in the tables below). We found no differences in psychiatric hospitalization rates.

Finally, based on self-reported personal expenditure and time spent attending intervention sessions, intervention study participants incurred an additional $117K in personal costs ($1,129/participant). The majority of these costs were derived from the value of their time traveling to, and participating in, the intervention sessions. Our participants were also credited, however, with a modest offset for lowering self-reported expenditures on items such as junk food during the intervention. Including these participant costs approximates a cost-effectiveness analysis from a societal perspective.

Table 2 presents the values of the primary outcome measures (reductions in fasting glucose and weight) we used in the economic analysis. While the EQ-5D results are included for informational purposes, the difference was not significant and is not included in the subsequent economic results.

Table 2. Adjusted means for primary outcome measures and change over time by intervention and control group.

| Outcome | Baseline | 12 months | 12 month change |

Difference in change |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |||

|

Fasting

glucose (mg/dL) |

||||||

| Control | 106.57 | 1.79 | 110.11 | 2.58 | 3.54 | |

| Intervention | 106.78 | 1.60 | 100.97 | 2.18 | −5.81 | −9.35 |

| Weight (kg) | ||||||

| Control | 106.92 | 2.33 | 105.24 | 2.52 | −1.68 | |

| Intervention | 108.10 | 2.56 | 103.72 | 2.66 | −4.37 | −2.69 |

| EQ-5D | ||||||

| Control | 0.68 | 0.02 | 0.68 | 0.02 | 0.00 | |

| Intervention | 0.70 | 0.02 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

Table 3 summarizes the per-participant intervention costs and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) for fasting glucose (incremental cost per one mg/dL reduced) and weight (incremental cost per one kg reduced). We present four cost scenarios to allow health policy makers to see cost increases or decreases which may be relevant to future implementations of the project. Three of these scenarios are related to the health system/payer perspective: A) intervention delivery alone; B) intervention delivery plus recruitment costs; and C) intervention delivery plus recruitment costs minus the value of reduced hospitalizations. The final scenario (D) is the societal perspective and includes intervention delivery plus recruitment and personal costs to participants minus the value of reduced hospitalizations.

Table 3. Per-participant costs and incremental cost per incremental change in fasting glucose (mg/dL) and weight loss (kg).

| Cost scenarios | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health system perspective | Societal perspective |

|||

|

Scenario A Intervention delivery only |

Scenario B Intervention delivery + recruitment |

Scenario C Intervention delivery + recruitment costs – reduced hospitalizations |

Scenario D Intervention delivery + recruitment and participant costs – reduced hospitalizations |

|

| Total cost (including overhead) |

$ 480,013 | $ 591,421 | $ 453,921 | $ 571,313 |

| Per intervention participant1 | $ 4,616 | $ 5,687 | $ 4,365 | $ 5,493 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Fasting glucose (cost per mg/dL reduced) |

||||

| --87 participants2 | $ 590 | $ 727 | $ 558 | $ 702 |

| --104 participants1 | $ 494 | $ 608 | $ 467 | $ 588 |

| Weight (cost per kg reduced) |

||||

| --87 participants2 | $ 2,051 | $ 2,527 | $ 1,940 | $ 2,441 |

| --104 participants1 | $ 1,716 | $ 2,114 | $ 1,623 | $ 2,042 |

n=104 participants who were randomized to the intervention; these analyses are based on intent to treat.

n=87 participants who are 12 month “completers”; these individuals have relevant weight and questionnaire data at 12 months.

We planned to deliver STRIDE to all 104 participants randomized to intervention. However, only 87 individuals completed the 12-month program. Because of this, we present the ICERs calculated for each primary outcome in two ways: focusing first on the 87 “completers” alone, then second by assuming that all 104 participants randomized to the intervention arm had completed the program (intent-to-treat). Non-completers were assigned the average level of outcome reduction. Under these assumptions, STRIDE generated ICERs ranging from $1,940 (scenario C) to $2,527 (scenario B) per kg lost, and $558 (scenario C) to $727 (scenario B) per mg/dL of fasting glucose reduced. Assigning the average clinical outcome reduction to the 17 individuals who were assigned to intervention but did not complete the program reduced all ICERs by approximately 16%.

Two salient points emerge from these baseline results: First, recruitment expenses add 23% to the intervention delivery cost per relevant outcome unit. If the intervention were implemented in typical clinical settings, these costs would likely be substantially less, and could even be zero. Second, potential savings from reduced hospitalizations are nearly offset by our estimates of participants’ investments of time and money when total costs are considered. From the health system/payer perspective, however, participants’ investments would not be considered. Thus, if recruitment costs and participant investments of time and money were not included, per-participant costs would be $3,937 for completers and $3,293 under intent-to-treat.

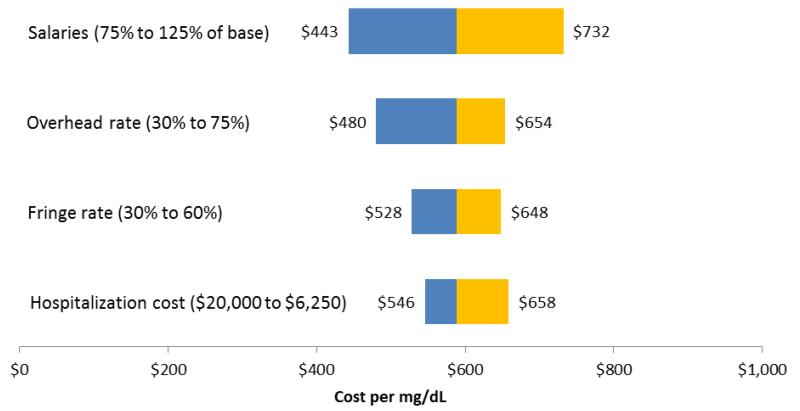

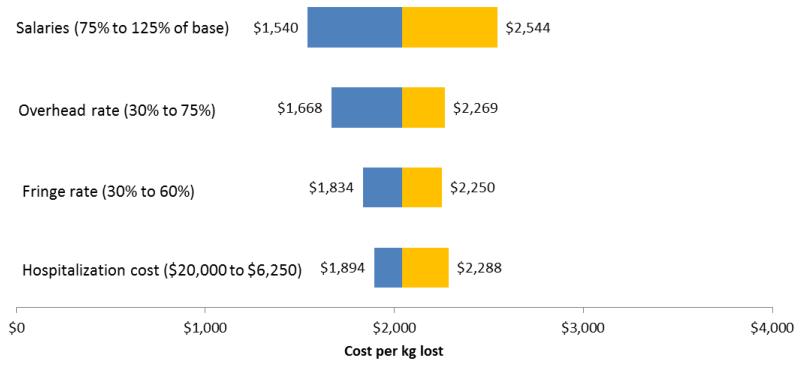

Table 4 presents selected univariate sensitivity analyses to explore the robustness of the baseline results. These analyses provide information about implementation costs in routine clinical settings. For example, we compared overhead rates of 58% and 30% and salary fringe rates reduction of 45% and 30%. Overhead rates in academic research centers are typically higher than those in community settings and even clinical settings. We also report effects of lowering the value of estimated reduced hospitalization costs by 50%, and of raising and lowering overall salaries by 25% relative to the STRIDE baseline. The single largest individual effects on estimated ICERs resulted from lowering the overhead rate and reducing salaries by 25%. Obviously, the combined effect of relaxing two or more of these assumptions (e.g., lowering both the overhead and fringe rates to 30%) would have an even larger effect on the ICERs. Figures 1 and 2 are tornado diagrams illustrating graphically the influence of selected elements on the variability inherent in the ICERs.

Table 4. Univariate sensitivity analyses.

| Cost scenarios | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health system perspective | Societal perspective | |||

|

Scenario A Intervention delivery only |

Scenario B Intervention delivery + recruitment |

Scenario C Intervention delivery + recruitment costs – reduced hospitalizations |

Scenario D Intervention delivery + recruitment and participant costs – reduced hospitalizations |

|

| Overhead rate (reduced to 30% from 58%) | ||||

| Total Cost | $394,948 | $486,612 | $349,112 | $466.504 |

| Fasting glucose (cost per mg/dL reduced) |

||||

| 87 participants1 | 486 | 598 | 429 | 573 |

| 104 participants2 | 406 | 500 | 359 | 480 |

| Weight (cost per kg reduced) | ||||

| 87 participants1 | 1,688 | 2,079 | 1,492 | 1,993 |

| 104 participants2 | 1,412 | 1,739 | 1,248 | 1,668 |

|

Fringe rate (reduced to 30%

from 45%) |

||||

| Total Cost | $433,411 | $533,294 | $395,794 | $513,186 |

| Fasting glucose (cost per mg/dL reduced) |

||||

| 87 participants1 | 533 | 656 | 487 | 631 |

| 104 participants2 | 446 | 548 | 407 | 528 |

| Weight (cost per kg reduced) | ||||

| 87 participants1 | 1,852 | 2,279 | 1,691 | 2,193 |

| 104 participants2 | 1,549 | 1,906 | 1,415 | 1,834 |

| Hospitalization costs (reduced to $6,250 from $12,500) | ||||

| Total Cost | $480,013 | $591,421 | $522,671 | $640,063 |

| Fasting glucose (cost per mg/dL reduced) |

||||

| 87 participants1 | 590 | 727 | 643 | 787 |

| 104 participants2 | 494 | 608 | 538 | 658 |

| Weight (cost per kg reduced) | ||||

| 87 participants1 | 2,051 | 2,527 | 2,233 | 2,735 |

| 104 participants2 | 1,716 | 2,114 | 1,868 | 2,288 |

| Salaries (125% of baseline) | ||||

| Total Cost | $592,634 | $731,893 | $594,393 | $711,785 |

| Fasting glucose (cost per mg/dL reduced) |

||||

| 87 participants1 | 729 | 900 | 731 | 875 |

| 104 participants2 | 609 | 753 | 611 | 732 |

| Weight (cost per kg reduced) | ||||

| 87 participants1 | 2,532 | 3,127 | 2,540 | 3,041 |

| 104 participants2 | 2,118 | 2,616 | 2,125 | 2,544 |

| Salaries (75% of baseline) | ||||

| Total Cost | $367,392 | $450,948 | $313,448 | $430,840 |

| Fasting glucose (cost per mg/dL reduced) |

||||

| 87 participants1 | 452 | 554 | 385 | 530 |

| 104 participants2 | 378 | 464 | 322 | 443 |

| Weight (cost per kg reduced) | ||||

| 87 participants1 | 1,570 | 1,927 | 1,339 | 1,841 |

| 104 participants2 | 1,313 | 1,612 | 1,120 | 1,540 |

n=87 participants who are 12 month “completers”; these individuals have relevant weight and questionnaire data at 12 months.

n=104 participants who were randomized to the intervention; these analyses are based on intent to treat.

Figure 1. Influence of Selected Variables on Incremental Cost per Incremental Unit of Fasting Glucose (mg/dL).

Figure 2. Influence of Selected Variables on Incremental Cost per Incremental Kilogram of Weight Lost (kg).

As noted, we observed no statistically significant difference in EQ-5D scores between intervention and control participants, although the mean EQ-5D score was 0.02 higher for the intervention group, which is modestly suggestive of a possible improvement in quality of life from weight loss and/or control of diabetes risk factors. We adapted analyses conducted in a 2014 meta-analysis of commercial weight loss programs to add context to STRIDE’s clinical results (Finkelstein & Kruger, 2014). In this study, Finkelstein and Kruger used external SF-12 data to apply a widely used algorithm for converting SF-12 (Tunis, Croghan, Heilman, Johnstone, & Obenchain, 1999; Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1995) responses to a health-related quality of life (QOL) metric. This allowed the authors to estimate an ICER (for commercial programs) in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), a health outcome measure that assigns, to a year of life, a 0-1 weight corresponding to the quality of life during that period, where 1 represents perfect health and 0 is equivalent to death. The number of QALYs represents the number of healthy years that are valued equivalently to an actual health outcome. They then used linear regression to assess the impact of weight loss on change in QOL, controlling for basic demographics, and extrapolated to four years from baseline. A crude mapping of the reported weight loss in STRIDE to Finkelstein and Kruger’s regression results suggests that STRIDE would generate an ICER ranging from $233K (scenario C) to $304K (scenario B) per QALY, inclusive of overhead.

Discussion

STRIDE showed that a weight loss and lifestyle intervention tailored for people with serious mental illnesses taking antipsychotic medications can reduce weight and improve glucose control (Green et al., 2015). In the context of constrained health care budgets, understanding the cost and cost-effectiveness of delivering this type of intervention provides essential information for program managers considering implementation and policymakers considering funding for such interventions. Our cost analyses found a total intervention cost of $453,921 using a very conservative health system perspective ($4,365 per participant; $467 per reduced mg/dL fasting glucose; $1,623 per reduced kg). Perhaps a more accurate health system perspective would exclude recruitment costs and include potential cost savings by reduced hospitalizations. Such a perspective would recast the STRIDE results as follows: $342,513 total costs; $3,293 per participant, $352 per reduced mg/dL fasting glucose and $1,224 per reduced kg among participants. These costs include overhead costs, which could be subtracted if the program was implemented using existing infrastructure. Finally, if reduced hospitalizations from 13-24 months were also considered, an additional $137,500 could also be subtracted. Such a cost evaluation would make the costs of STRIDE more comparable to those found in the Diabetes Prevention Program (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, 2003, 2012) trial and in a meta-analysis of lifestyle interventions in the general population (Lehnert et al., 2012).

Our economic evaluation is particularly salient in light of Verhaeghe and colleague’s (2014) recently published cost-effectiveness analysis of a health promotion intervention for individuals with serious mental illnesses. Their base-case analysis with 20-year horizon-generated ICERs of €27K ($34K as of 11/14/2014) per QALY for men and €40K ($50K) per QALY for women. Over a five-year horizon, comparable ICERs were €191K ($239K) per QALY and €267K ($334K) per QALY, respectively. These latter estimates are within the general magnitude of our crude ICERs in QALY terms, assessed over four years. Verhaeghe and colleagues’ (2013) trial was significantly shorter than the STRIDE intervention (10 weekly sessions versus 30 sessions in 12 months), however, and STRIDE resulted in greater weight loss. Verhaeghe and colleagues reported a 0.57 kg loss after the 10-week intervention period; STRIDE participants lost an average of 4.4 kg at the end of the 6-month intensive intervention period, and had maintained a 2.6 kg loss at 12 months, the end of the maintenance intervention period). These differences cast a more favorable light on the costs and cost-effectiveness of the STRIDE intervention.

The paucity of comparable studies among persons with serious mental illnesses complicates our ability to fully place the economic results of STRIDE in the appropriate context. Also, comparisons of lifestyle interventions are confounded by the diversity of intervention aims and targets, some of which are naturally costlier than others. In particular, comprehensive behavioral lifestyle interventions that address diet, physical activity, and behavior change are more expensive to conduct than interventions that target each of those domains separately (Lehnert et al., 2012; Roux et al., 2006). Other than the work conducted by Verhaeghe and colleagues (2013; 2014), the most directly comparable economic assessment of a comprehensive lifestyle intervention (6 months of weekly visits followed by 6 months of bimonthly visits) delivered to a vulnerable population involved an intervention delivered to Latina women (Toobert et al., 2011). In the corresponding cost analyses of that study, the costs of changing BMI by one kg/m2 ranged from $5,076 to $7,723 depending on perspective (Ritzwoller et al., 2011). In STRIDE, we found similar costs associated for reducing weight, ranging from $1,623 to $2,114 per kilogram.

Compared with a recent review of cost-effectiveness analyses of behavioral obesity interventions in the general population (both prevention and weight reduction), STRIDE appears to be more expensive than average (Lehnert et al., 2012). As our analysis is only the second economic evaluation of a weight intervention involving individuals with serious mental illnesses (Verhaeghe et al., 2014), and is the only evaluation of a study of people taking antipsychotic medications, such comparisons may be premature. Moreover, the relative cost of STRIDE may be in part due to the inclusion of costs not reported in other studies, such as recruitment labor costs. Including these costs may have blurred the distinction between research-related recruitment and research-related intervention development and implementation. A second issue that may have led to these findings is that study staff were more highly paid than comparable staff in the Portland, Oregon metropolitan area, something that the sensitivity analyses in Table 4 attempted to illuminate by offering a scenario in which personnel costs are reduced by 25%. A third issue may be in how we valued the time spent in interventions, which is relevant to the societal perspective. At baseline, the STRIDE sample was 30% employed; 35% retired, unemployed, temporarily laid off, or homemakers; and 36% disabled (Yarborough et al., 2013). These rates are typical for individuals with serious mental illnesses. Our methods for calculating the costs of participating included using national wage rates, which are higher than wages in Oregon. Even with non-work time valued at only 30% of the national wage rate, we may be overestimating the personal costs of participating. For these reasons, our group has published a community-based cost analysis which outlined expenses required to implement the intervention in small-scale, community-based health settings (Stumbo et al., 2015).

Finally, STRIDE was more intensive than weight loss interventions conducted in other populations given the complex nature of delivering an intervention to individuals with a range of cognitive processing deficits (Yarborough et al., 2011). This was particularly true of our choice to use two intervention group facilitators, which doubled our labor costs. These costs could be reduced by using a sole facilitator or by limiting recruitment activities to posters and clinician referrals, which is possible for others wishing to conduct this intervention as all materials are being made freely available on the study website (www.kpchr.org/research/public/stride/stride.htm). In addition, the intervention was significantly longer than that reported in Verhaeghe and colleagues (2013) and the comprehensiveness of topics covered was also more in-depth than many other interventions. Further, as noted earlier, a significant reduction in medical hospitalizations between intervention and control groups—noted in other intensive lifestyle interventions as well (Espeland et al., 2014)—was observed not only during the 12 months of active intervention, but during the subsequent 12 months as well, after intervention activity had ended. If such results were sustained over longer periods, costs from the system perspective could be reduced substantially.

Limitations

We were unable to calculate cost-effectiveness planes for these analyses. Intervention and recruitment costs, the large majority of total costs, are fixed averages assigned to all intervention participants. What variability exists is basically confined to the survey-based participant cost and savings data, which were available from only about half of participants (and extrapolated to the other half), and the magnitude of which is dwarfed by intervention and recruitment. Further, we were unable to calculate QALYs for this analysis given the relatively short duration of this study; QALYs are more appropriately analyzed using data from longer-term studies over 5-10 years.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is only the second study assessing the cost-effectiveness of a health promotion intervention targeting weight loss, physical activity, and dietary changes in individuals with serious mental illnesses. STRIDE’s economic performance appears broadly comparable to that of the one other relevant published study (Verhaeghe et al., 2014) and is similar to other intensive interventions in vulnerable populations (Ritzwoller et al., 2011). Additional research with similarly intensive interventions, and among individuals with serious mental illnesses, is needed to produce a full picture of the cost-effectiveness of such interventions. As obesity-related risks, morbidity, and mortality continue to take their toll on the general population, and on individuals with serious mental illnesses in particular, policymakers and health system administrators will need robust economic studies in order to plan and implement appropriate mitigating interventions.

References

- Borushek A. The Calorie King, Calorie, Fat, & Carbohydrate Counter 2013. Family Health Publications; Costa Mesa: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AH. Handling uncertainty in cost-effectiveness models. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17(5):479–500. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200017050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaggar PS, Shaw SM, Williams SG. Effect of antipsychotic medications on glucose and lipid levels. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2011;51(5):631–638. doi: 10.1177/0091270010368678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3(2):A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daumit GL, Dickerson FB, Wang NY, Dalcin A, Jerome GJ, Anderson CA, Appel LJ. A Behavioral Weight-Loss Intervention in Persons with Serious Mental Illness. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368(17):1594–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Within-trial cost-effectiveness of lifestyle intervention or metformin for the primary prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(9):2518–2523. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group The 10-year cost-effectiveness of lifestyle intervention or metformin for diabetes prevention: an intent-to-treat analysis of the DPP/DPPOS. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):723–730. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1468. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Zhao L, Von ES, Morrato EH, Marcus SC. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Medical Care. 2011;49(6):599–604. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820bf86e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeland MA, Glick HA, Bertoni A, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Clark JM, Zhang P. Impact of an intensive lifestyle intervention on use and cost of medical services among overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: the action for health in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(9):2548–2556. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EuroQol Group EQ-5D Website. 2014 from www.euroqol.org/home.html.

- Finkelstein EA, Kruger E. Meta- and cost-effectiveness analysis of commercial weight loss strategies. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22(9):1942–1951. doi: 10.1002/oby.20824. doi: 10.1002/oby.20824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Veerman JL, Barendregt JJ, Vos T. Cost-effectiveness of diet and exercise interventions to reduce overweight and obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2011;2005;35(8):1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.246. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk KL, Elmer PJ, Stevens VJ, Harsha DW, Craddick SR, Lin PH, Appel LJ. PREMIER--A trial of lifestyle interventions for blood pressure control: Intervention design and rationale. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;9(3):271–280. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Green CA, Yarborough BJ, Leo MC, Yarborough MT, Stumbo SP, Janoff SL, Stevens VJ. The STRIDE Weight Loss and Lifestyle Intervention for Individuals taking Antipsychotic Medications: A Randomized Trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):71–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020173. doi: doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inflation.eu Historic harmonised inflation Belgium – HICP inflation. 2015 Inflation.eu Retrieved June 2, 2015, from www.inflation.eu/inflation-rates/belgium/historic-inflation/hicp-inflation-belgium.aspx.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, Hu FB, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Kushner RF, Loria CM, Millen BE, Nonas CA, Pi-Sunyer FX, Stevens J, Stevens VJ, Wadden TA, Wolfe BM, Yanovski SZ, American College of Cardiology. American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Obesity Society 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Jul 1;63(25 Pt B):2985–3023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Morden NE, Austin K, Ilgen M, McCarthy JF, Dalack G, Blow FC. Excess heart-disease-related mortality in a national study of patients with mental disorders: Identifying modifiable risk factors. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert T, Sonntag D, Konnopka A, Riedel-Heller S, Konig HH. The long-term cost-effectiveness of obesity prevention interventions: systematic literature review. Obesity Reviews. 2012;13(6):537–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra AK, Correll CU, Chowdhury NI, Muller DJ, Gregersen PK, Lee AT, Kennedy JL. Association Between Common Variants Near the Melanocortin 4 Receptor Gene and Severe Antipsychotic Drug-Induced Weight Gain. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012 Sep;69(9):904–12. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WG, Fryback DF, Weinstein MC. Reflecting uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. In: Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein WC, editors. Cost effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. Reprinted from: IN FILE. [Google Scholar]

- Meenan RT, Stevens VJ, Funk K, Bauck A, Jerome GJ, Lien LF, Svetkey LP. Development and implementation cost analysis of telephone- and Internet-based interventions for the maintenance of weight loss. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2009;25(3):400–410. doi: 10.1017/S0266462309990018. doi: 10.1017/S0266462309990018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenan RT, Stevens VJ, Hornbrook MC, LaChance PA, Hollis JF, Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E. Cost-effectiveness of a hospital-based smoking-cessation interention. Medical Care. 1998;36(5):670–678. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenan RT, Vogt TM, Williams AE, Stevens VJ, Albright CL, Nigg C. Economic evaluation of a worksite obesity prevention and intervention trial among hotel workers in Hawaii. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2010;52(Suppl 1):S8–13. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c81af9. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c81af9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, L. a. B. I. Your guide to lowering your blood pressure with DASH. 2006 NIH Publication No. 06-4082. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/hbp/dash/new_dash.pdf, NIH Publication No. 06-4082.

- Newcomer JW. Metabolic considerations in the use of antipsychotic medications: A review of recent evidence. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 1):20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Steiner C. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2013. Costs for Hospital Stays in the United States, 2011: Statistical Brief #168. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzwoller DP, Glasgow RE, Sukhanova AY, Bennett GG, Warner ET, Greaney ML, Colditz GA. Economic Analyses of the Be Fit Be Well Program: A Weight Loss Program for Community Health Centers. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013 Dec;28(12):1581–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2492-3. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2492-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzwoller DP, Sukhanova A, Gaglio B, Glasgow RE. Costing behavioral interventions: a practical guide to enhance translation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;37(2):218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzwoller DP, Sukhanova AS, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, King DK, Gaglio B, Toobert DJ. Intervention costs and cost-effectiveness for a multiple-risk-factor diabetes self-management trial for Latinas: economic analysis of Viva Bien! Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2011;1(3):427–435. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0037-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux L, Kuntz KM, Donaldson C, Goldie SJ. Economic evaluation of weight loss interventions in overweight and obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(6):1093–1106. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.125. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumbo SP, Yarborough BJ, Yarborough MT, Janoff SL, Lewinsohn M, Green CA. Costs of implementing a behavioral weight-loss and lifestyle-change program for individuals with serious mental illnesses in community settings. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0322-3. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0322-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetkey LP, Harsha DW, Vollmer WM, Stevens VJ, Obarzanek E, Elmer PJ, Appel LJ. Premier: A clinical trial of comprehensive lifestyle modification for blood pressure control: Rationale, design and baseline characteristics. Annals of Epidemiology. 2003;13(6):462–471. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toobert DJ, Strycker LA, Barrera M, Jr., Osuna D, King DK, Glasgow RE. Outcomes from a multiple risk factor diabetes self-management trial for Latinas: inverted exclamation markViva Bien! Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;41(3):310–323. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9256-7. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9256-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AG, Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, Vetter M, Kumanyika S, Glick HA. Cost-effectiveness of a primary care intervention to treat obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2013;2005;37(Suppl 1):S31–37. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.94. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunis SL, Croghan TW, Heilman DK, Johnstone BM, Obenchain RL. Reliability, validity, and application of the medical outcomes study 36- item short-form health survey (SF-36) in schizophrenic patients treated with olanzapine versus haloperidol. Medical Care. 1999;37(7):678–691. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199907000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Detailed Report; Data for December 2007. Table 28. Historical Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). U.S. city average, by commodity and service group and detailed expenditure categories. 2007 Retrieved June 2, 2015, from www.bls.gov/cpi/cpid0712.pdf.

- United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational employment statistics: May 2013 national occupational employment and wage estimates. 2014 http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm#21-0000.

- United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Detailed Report; Data for April 2015. Table 28. Historical Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). U.S. city average, by commodity and service group and detailed expenditure categories. 2015 Retrieved June 2, 2015, from www.bls.gov/cpi/cpid1504.pdf.

- Verhaeghe N, Clays E, Vereecken C, De Maeseneer J, Maes L, Van Heeringen C, Annemans L. Health promotion in individuals with mental disorders: a cluster preference randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:657. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-657. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe N, De Smedt D, De Maeseneer J, Maes L, Van Heeringen C, Annemans L. Cost-effectiveness of health promotion targeting physical activity and healthy eating in mental health care. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:856. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-856. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; Boston: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yarborough BJ, Janoff SL, Stevens VJ, Kohler D, Green CA. Delivering a lifestyle and weight loss intervention to individuals in real-world mental health settings: Lessons and opportunities. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2011;1(3):406–415. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarborough BJ, Leo MC, Stumbo S, Perrin NA, Green CA. STRIDE: a randomized trial of a lifestyle intervention to promote weight loss among individuals taking antipsychotic medications. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):238. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]