Abstract

Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs) are school-based youth settings that could promote health. Yet, GSAs have been treated as homogenous without attention to variability in how they operate or to how youth are involved in different capacities. Using a systems perspective, we considered two primary dimensions along which GSAs function to promote health: providing socializing and advocacy opportunities. Among 448 students in 48 GSAs who attended six regional conferences in Massachusetts (59.8% LGBQ; 69.9% White; 70.1% cisgender female), we found substantial variation among GSAs and youth in levels of socializing and advocacy. GSAs were more distinct from one another on advocacy than socializing. Using multilevel modeling, we identified group and individual factors accounting for this variability. In the socializing model, youth and GSAs that did more socializing activities did more advocacy. In the advocacy model, youth who were more actively engaged in the GSA as well as GSAs whose youth collectively perceived greater school hostility and reported greater social justice efficacy did more advocacy. Findings suggest potential reasons why GSAs vary in how they function in ways ranging from internal provisions of support, to visibility raising, to collective social change. The findings are further relevant for settings supporting youth from other marginalized backgrounds and that include advocacy in their mission.

Keywords: Gay-Straight Alliances, Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, Youth programs, Positive youth development, Social justice, Social support, Advocacy

There has been a growing interest in factors that promote the healthy development of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth (LGBT; Saewyc, 2011). Some studies have looked to social settings, one being Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs; Griffin, Lee, Waugh, & Beyer, 2004; Heck, Flentje, & Cochran, 2011; Poteat, Sinclair, DiGiovanni, Koenig, & Russell, 2013; Walls, Kane, & Wisneski, 2010). Based in an increasing number of schools across the U.S., GSAs serve multiple functions, from socializing, to providing support, to engaging in advocacy (Griffin et al., 2004; Russell, Muraco, Subramaniam, Aarti, & Laub, 2009). Historically, GSAs formed as an extension of community-based youth programs with the purpose of protecting and supporting students who faced violence and discrimination (Uribe, 1994). Advocacy efforts in the form of awareness-raising and challenging institutional discrimination have since been integrated (Miceli, 2005; Russell et al., 2009). The functions of GSAs and their approaches are consistent with youth program and positive youth development models (Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Damon, 2004). Namely, GSAs are safe and supportive settings that also seek to cultivate youths’ strengths by providing them with opportunities for leadership with adult support. These types of youth settings foster healthy development, including among youth from certain marginalized groups (Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Fredricks & Simpkins, 2012). Nevertheless, there has been little attention to settings such as GSAs that serve sexual and gender minority populations.

Non-experimental comparisons show that youth in schools with GSAs report less substance use, truancy, victimization, and safer climates than youth in schools without GSAs (Heck et al., 2011; Poteat et al., 2013; Szalacha, 2003; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, & Russell, 2011; Walls et al., 2010). Few studies have noted how GSA members actually participate in their GSA; others have treated members as homogenous when comparing them to non-members. Yet, youth in GSAs likely are involved in different capacities. Further, studies have treated GSAs as essentially uniform. This, too, is problematic, as GSAs likely vary in how they operate. Thus, GSAs warrant closer attention, particularly from a systems perspective that considers specific dimensions of how GSAs function as youth settings (Shinn & Yoshikawa, 2008; Tseng & Seidman, 2007) and that attends to the varied experiences among youth involved in them.

GSAs as Settings for Socializing and Advocacy

GSAs tend to share a common mission, but they are not standardized programs. There are common activities and events that many GSAs sponsor, but these are largely determined by the members of each GSA, in line with the general youth-led approach. As such, GSAs could vary in their activities. We consider variability across GSAs and among their members on their engagement in organized socializing and advocacy activities beyond standard GSA meetings. For example, some GSAs as a whole may pursue more advocacy than others, while variability among members within a given GSA also may exist.

Essentially, GSAs may differ from one another in how much they promote internally-focused group support and socializing activities and in how much they promote externally-focused advocacy activities. We focus on socializing and advocacy activities, broadly conceived, because these two dimensions provide different opportunities for community building. Specifically, they can be tied to the frameworks of bonding social capital and bridging social capital (Almedom, 2005; Kim, Subramanian, & Kawachi, 2006; Warren & Mapp, 2011). Bonding social capital serves to strengthen networks internally (Kim et al., 2006). Socializing activities in GSAs (e.g., dances, parties, or movie nights) can be considered ways to build bonding social capital among members. Bridging social capital aims to strengthen ties to other networks and to exert an influence beyond the immediate network (Kim et al., 2006). Advocacy activities (e.g., Day of Silence, Ally Week, or classroom presentations) are ways for GSAs to foster bridging social capital. GSA advocacy often reflects efforts to enhance visibility and thus challenge heterosexist norms or assumptions that systematically make non-heterosexual identities, issues, or concerns invisible, as well as efforts to challenge systemic inequality such as discriminatory school policies or widespread homophobic harassment (Mayberry, 2006; Mayo, 2004; Miceli, 2005; Russell et al., 2009).

Apart from standard meetings, socializing and advocacy encompass the majority of GSA activities and aim to promote healthy development (Griffin et al., 2004; GSA Network, n.d.). Socializing events are important because GSAs often are one of few safe places for LGBT youth to interact (Griffin et al., 2004). Many LGBT youth continue to face school-based victimization and perceive unsafe school climates (Birkett, Russell, & Corliss, 2014). Such activities are pertinent, as during adolescence peers become a strong source of support (Berndt, 2002) and extracurricular settings are a major context for social development (Feldman & Matjasko, 2005). Also, more youth settings now feature advocacy in their mission (Fields & Russell, 2005; Ginwright, 2007; Inkelas, 2004). Because advocacy involves working with others or addressing issues external to the GSA, it may foster more bridging social capital (e.g., to other groups in schools or the wider community) that also benefits GSA members. Indeed, advocacy is related to empowerment, belonging, and purpose (Poteat et al., 2015; Russell et al., 2009; Toomey & Russell, 2013). These activities also may benefit non-members (e.g., engender hope, promote their safety) because these efforts seek larger scale changes on concerns that affect students who are not immediate members of the GSA.

Beyond simply documenting variability in the socializing and advocacy dimensions of GSAs, a systems perspective considers predictors of such variation (Shinn & Yoshikawa, 2008; Tseng & Seidman, 2007). This arena of youth development is understudied – studies that link settings as a whole to youth outcomes far outweigh those that seek to understand variability in the functions of settings themselves. Without knowing what individual and social factors predict variation across settings, we cannot adequately build theories to guide or improve interventions (Shinn & Yoshikawa, 2008). Based on the youth programs literature, we test factors that could contribute to youth and GSAs engaging in more of these activities. Identifying these potential factors would aid in theory and model building to show how GSAs and similar groups may be tailored to meet the needs of diverse members.

Variability across GSAs in Overall Socializing and Advocacy

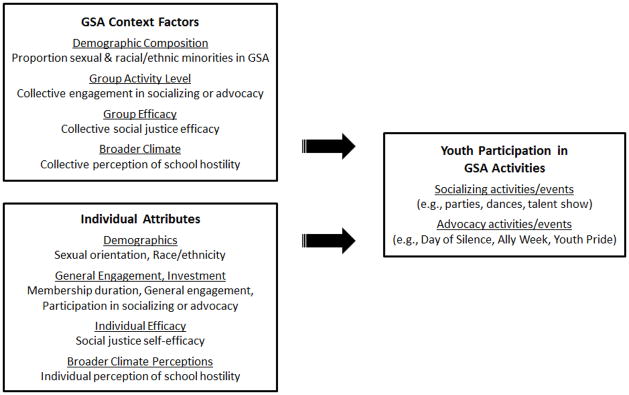

A systems perspective highlights the need to consider contextual factors contributing to how settings function and youths’ experiences in these settings (Tseng & Seidman, 2007). We draw from the general youth programs literature for some factors, while including others based on the unique nature of GSAs and other groups that serve marginalized populations (see Figure 1). Among these factors, compositional differences may be important. Other literatures suggest compositional effects of programs, schools, and communities on youth outcomes (Fauth, Roth, & Brooks-Gunn, 2007). The representation of LGBT or racial/ethnic minority youth in a GSA could relate to the activities done because GSAs often decide collectively on their activities (Poteat et al., 2015) and preferences may differ based on sexual orientation or race/ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of group and individual factors accounting for variability in socializing and advocacy.

GSA functions could vary based on the school settings in which they are embedded. Although youth in schools with GSAs report safer climates (Heck et al., 2011), some advisors still report facing hostility from teachers, administrators, and students (Watson, Varjas, Meyers, & Graybill, 2010). Indeed, school systems sometimes attempt to prohibit the formation of GSAs (Fetner & Kush, 2008; Mayo, 2008). Some politically and religiously conservative schools have sought to ban GSAs, using abstinence-only policies to justify their actions; or, they have required parental notification, largely meant to discourage student GSA membership (Mayo, 2008). GSAs in settings more hostile to LGBT issues may be those engaging in more advocacy, which could be a reaction to advocacy or the cause for advocacy. Hostility from the broader environment has been given less attention in the general youth programs literature, as it may be assumed that schools or communities support, or at least are not openly hostile toward, youth programs. However, for settings that work with stigmatized populations such as LGBT youth, a hostile external context may matter and may bring about youth activism (Fine & Jaffee-Walter, 2007). Therefore, school-level hostility to LGBT youth could be a key factor that shapes the activities and experiences of GSAs and similar groups that engage in activism to challenge systems of inequality (e.g., through deliberate awareness-raising efforts to challenge heterosexism and invisibility or by directly countering acts of discrimination; Mayberry, 2006; Miceli, 2005).

Finally, the collective social justice efficacy of the GSA may distinguish GSAs doing more advocacy. Social justice self-efficacy reflects individuals’ perceived ability to discuss and engage in actions to address social inequality (Torres-Harding, Siers, & Olson, 2012). This factor could be critical for GSAs and other programs that include advocacy in their mission. GSA social justice promotion can include advocating for school non-discrimination policies, countering homophobic bullying, or raising awareness of LGBT youths’ experiences (GSA Network, n.d.). Notably, advocacy events (e.g., Day of Silence, Ally Week) often require the effort of many youth. Thus, it may require multiple members with high social justice self-efficacy, not simply one individual’s high self-efficacy, for such actions to come to fruition.

Variability within GSAs in Members’ Socializing and Advocacy

In addition to distinctions across GSAs in their socializing and advocacy, there could be key markers for which youth in these GSAs engage in more socializing or advocacy than others. We first consider sexual orientation and race/ethnicity differences. The youth programs literature has emphasized the need to ensure that youth programs adequately serve marginalized youth (Fredricks & Simpkins, 2012). As such, it is critical to consider these potential differences to ensure that GSAs provide relevant opportunities for youth from all backgrounds.

Youth who are more engaged at their GSA meetings (e.g., speak up more, take on leadership) may participate in more socializing or advocacy events that take place outside standard meetings. These youth may be more invested in the GSA and thus they may participate in more supplemental activities. Youth who are more engaged in youth programs derive more benefits from their involvement (Hansen & Larson, 2007; Weiss, Little, & Bouffard, 2005). This marks a shift from comparing GSA members to nonmembers to now capturing nuance in how youth engage in these settings (e.g., in relation to the activities or programs done along the dimensions of socializing or advocacy).

GSA members’ own social justice self-efficacy may be related to their own level of advocacy, though not necessarily with their level of socializing. Youth in GSAs are motivated to engage in advocacy to promote social justice (Russell et al., 2009); yet, not all youth may engage in advocacy to the same degree. These events require significant effort and entail multiple challenges relative to socializing activities. Thus, youths’ self-efficacy, particularly social justice-related, may be a key factor underlying their amount of advocacy.

The Current Study

There is an increased need for research to focus on settings that serve youth from marginalized backgrounds. This focus has been especially absent for GSAs and other groups for sexual and gender minorities. We addressed this issue by testing for differences across and within GSAs in Massachusetts in their socializing and advocacy, which are critical dimensions of their functioning and that fall within the bonding and bridging social capital framework to promote health and wellbeing (Almedom, 2005). We hypothesized that there would be significant variability among GSAs and youth in their amount of socializing and advocacy.

We tested several group-level factors that could account for variability across GSAs along their dimensions of socializing and advocacy: proportional representation of LGBT and racial/ethnic minority youth, collective perceptions of school hostility, and collective social justice efficacy of GSA members. We considered proportional representation of LGBT and racial/ethnic minority youth for exploratory purposes, given the limited attention to variability among GSA members in the extant literature. We hypothesized that collective perceptions of greater school hostility and social justice efficacy would be associated with GSAs engaging in more advocacy activities, but would be unrelated to socializing activities.

We tested several individual factors that could account for youths’ own variability in socializing and advocacy: sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, personal engagement and investment in the GSA, and social justice self-efficacy. First, we considered sexual orientation- and race/ethnicity-based differences for exploratory purposes, similar to our approach at the group level. Second, we hypothesized that youth who were more engaged and invested in GSA meetings would do more activities and events outside standard meetings. Third, we hypothesized that youth who reported greater social justice self-efficacy would engage in more advocacy-based activities, but not socializing activities. In these models, we controlled for how long youth had been members of their GSA.

Method

Data and Procedures

Data come from the 2013 Massachusetts GSA Network statewide survey of GSA youth members. The data include GSAs from rural and urban locations, liberal and conservative districts, and low and high SES areas. This Network is modeled on the original California GSA Network (www.gsanetwork.org) and is jointly supported by the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth and the Massachusetts Safe Schools Program for LGBTQ Students. As with the California GSA Network, which provides school climate surveys for youth and then works with various researchers to analyze these data, there is a strong assessment component to the Massachusetts GSA Network. It regularly gathers data as a part of needs assessments, program evaluations, and to identify best practices for GSAs.

We partnered with the Massachusetts GSA Network to analyze data from their survey of youth who attended their 2013 regional meetings held at six locations: the greater Boston area, Northeastern, Southeastern, Central, and Western Massachusetts, and Cape Cod. Youth volunteered to complete a short, anonymous survey, provided their GSA advisor granted adult consent. The GSA Network used adult consent over parent consent to avoid potential risks of inadvertently outing LGBT youth to parents. This is a common method in LGBT youth research to protect their safety and confidentiality (Mustanski, 2011). Students were told that their responses would be anonymous and that data are used for program evaluation and potentially for research purposes to produce reports or articles. Students who did not want to participate were able to do other activities (e.g., view resources). Surveys were given during a 15-minute period at the start of the meetings. Participating GSAs receive reports that cover the topics in the survey. We secured IRB approval for our secondary data analysis.

Participants

There were 448 students (Mage = 15.83, SD = 1.24) from 48 GSAs in Massachusetts. Students were distributed across high school grade levels (Grade 9: n = 94; Grade 10: n = 134; Grade 11: n = 108; Grade 12: n = 96) and a few students were in Grade 8 from several high schools with expanded grade structures (n = 8); 8 students did not report their grade level. Of the students, 314 identified as cisgender female, 101 as cisgender male, 10 as transgender male, 2 as transgender female, and 14 reported other identities (e.g., gender queer, gender fluid). Most students identified as LGBQ (n = 268) or as heterosexual (n = 158), while 22 students did not report their sexual orientation identity. Most students identified as White, non-Hispanic (n = 313), followed by biracial or multiracial (n = 51), Latino/a (n = 27), African American (n = 18), Asian or Asian American (n = 13), Middle Eastern, Arab, or Arab American (n = 7), and Native American (n = 3), while 8 students stated “other” and 8 students did not report their racial or ethnic identity.

Measures

Demographics

Students reported their age, grade, school, gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation (heterosexual, lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning, or other write-in response). Because of the limited number of youth in each sexual minority category, we dichotomized the responses as heterosexual or LGBTQ (those who identified as “other” indicated non-heterosexual identities, nearly all either “queer” or “pansexual”). We include transgender youth within this category because all but two participants who identified as transgender also identified as LGBQ. Because of many commonalities in discriminatory experiences of LGBQ and transgender youth, and because sexual and gender minority youth often are considered together in LGBTQ research, we included the two transgender youth who identified as heterosexual within the LGBTQ category. For the same reason of limited representation of each specific racial/ethnic minority group, we dichotomized the responses as white or racial/ethnic minority. Students also reported how long (in years and months) they had been a member of their GSA.

GSA engagement and investment

The survey included five items to assess students’ level of engagement and investment in GSA meetings (e.g., “I participate in conversations during GSA meetings,” “I tend to speak up during GSA meetings”). We conducted an exploratory factor analysis that indicated a unidimensional factor structure for these items (eigenvalue = 3.13; variance accounted for = 62.62%; factor loadings ranged from .61 to .85). Response options were never, rarely, sometimes, often, and all the time. Higher average scores represent greater GSA engagement and investment. Coefficient alpha reliability was α = .85.

Social justice self-efficacy

The survey included a 5-item subscale from the Social Justice Scale (Torres-Harding et al., 2012) that assesses self-efficacy to engage in social justice action (e.g., “I feel confident in my ability to talk to others about social injustices and the impact of social conditions on health and wellbeing”). Response options range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher average scores represent greater self-efficacy to engage in social justice action. Coefficient alpha reliability was α = .92.

School hostility

We combined three items from the survey that generally assessed students’ perceptions of school hostility to LGBT issues: (a) I feel pressured by teachers and administrators to remain silent about LGBT issues at school; (b) I feel uncomfortable voicing support for LGBT students and LGBT issues at school; and, (c) I have experienced backlash from other students for standing up for LGBT students or LGBT issues. Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher average scores represent greater perceived school hostility to LGBT issues. Coefficient alpha reliability was α = .62.

Socializing and advocacy engagement

Students reported their involvement in a list of some of the most common GSA socializing and advocacy activities and events, with space to write in others. The directions stated: “Below are a list of common school and community GSA sponsored or co-sponsored activities. Please check any of the ones you were personally involved in this year or last year.” Appendix A includes the full list. In consulting with the GSA Network, we classified each activity as socializing or advocacy. Although many advocacy activities involve a socializing function, we viewed advocacy as the higher-order function and therefore coded them as advocacy. The socializing activities did not contain a clear or intentional advocacy function. In total, there were 9 socializing and 12 advocacy activities or events, as well as the additional ones reported by students. Two researchers separately coded these additional activities or events as socializing or advocacy, with perfect agreement except for one item that ultimately was excluded (it reflected a student’s membership in a separate club). We summed the number of socializing and advocacy activities/events marked by students from the list or that they wrote. This produced a total socializing score and a total advocacy score (the number of socializing activities that students reported ranged from 0 to 7; the number of advocacy activities that students reported ranged from 0 to 10). Higher scores represent more socializing and advocacy activities/events done.

Results

Preliminary Analyses and Bivariate Associations

Prior to testing our proposed models, we tested for demographic differences among our measures and examined correlations for descriptive purposes. We computed MANOVAs to test for sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and gender differences on: membership duration, engagement and investment level, social justice self-efficacy, perceived school hostility, and amount of socializing and advocacy done. The MANOVA for sexual orientation was significant, Wilks’ Λ = .96, F (6, 362) = 2.70, p = .01, . Follow-up ANOVAs indicated only one significant difference: LGBTQ youth reported greater GSA engagement and investment than heterosexual youth, F (1, 367) = 6.41, p < .05, (LGBTQ: M = 2.78, SD = 0.86; Heterosexual: M = 2.54, SD = 0.93). The MANOVAs for race/ethnicity, Wilks’ Λ = .98, F (6, 372) = 1.17, p = .32, and gender, Wilks’ Λ = .99, F (6, 363) = 0.49, p = .82, were not significant. We present the bivariate correlations among the variables in Table 1 for descriptive purposes. The variables were correlated in ways that were conceptually consistent.

Table 1.

Correlations among Individual Variables

| Membership duration | Engagement level | School LGBT hostility | Social justice efficacy | Socializing activities | Advocacy activities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membership duration | — | |||||

| Engagement level | .42** | — | ||||

| School LGBT hostility | -.03 | -.01 | — | |||

| Social justice efficacy | .18** | .27** | -.07 | — | ||

| Socializing activities | .22** | .20** | .05 | .11* | — | |

| Advocacy activities | .42** | .41** | .07 | .21** | .43** | — |

Note. Membership duration = duration of individual’s GSA membership; Engagement level = individual’s overall engagement level in their GSA; School LGBT hostility = individual’s perception of school’s hostility to LGBT individuals or issues; Social justice efficacy = individual’s sense of social justice self-efficacy; Socializing activities = amount of engagement in socializing activities/events; Advocacy activities = amount of engagement in advocacy activities/events.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Predicting Socializing and Advocacy Engagement

We used multilevel modeling to test our series of primary research questions related to GSA and individual variability along dimensions of socializing and advocacy. First, we tested our hypothesis that there would be significant variability across GSAs in their amount of socializing and advocacy. Second, we tested factors at the individual-level and group-level to account for variability in youths’ and GSAs’ engagement in both types of activities.

For these analyses, we only included GSAs with more than three members represented. We did so in order to avoid complications with limited or no variability in scores within GSAs. This led to the exclusion of 8 GSAs and 12 participants. As such, our multilevel analyses included 40 of the original 48 GSAs. We followed standard multilevel modeling procedures (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) for our analyses using the SAS PROC MIXED procedure.

Variability across GSAs

We tested for significant variability across GSAs on youths’ socializing and advocacy based on fully unconditional null models. As hypothesized, there was significant variability across GSAs in levels of socializing (Z = 2.94, p < .01) and advocacy (Z = 3.61, p < .01). Using the variance components at Level 1 (i.e., amount of variance in scores within GSAs) and Level 2 (i.e., amount of variance in scores between GSAs), we calculated intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs). The ICCs represent the proportion of variance in socializing and advocacy existing between GSAs. As we expected, GSAs were distinct in their amount of socializing (ICC = .18) and advocacy (ICC = .33).

Accounting for variability in socializing and advocacy

To test our research hypotheses related to factors accounting for variability in youths’ and GSAs’ engagement in socializing and advocacy, we constructed multilevel models with these factors included as predictors. Our individual factors (at Level 1 in these models) were sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, membership duration (as a control variable), engagement and investment level, social justice self-efficacy, amount of advocacy (for the socializing model) or socializing (for the advocacy model), and perceived school hostility. We group-mean centered scores on our continuous variables at this level (Kreft, de Leeuw, & Aiken, 1995). Factors at this level essentially account for variability within GSAs in youths’ amount of socializing and advocacy. Our group factors (at Level 2 in these models) were the proportional representation of LGBTQ and racial/ethnic minority youth, members’ collective perceptions of school hostility, and their collective social justice efficacy. We included these factors as predictors of the Level 1 intercept (i.e., the mean levels of socializing and advocacy of GSAs). Factors at this level essentially account for variability across GSAs in levels of socializing and advocacy. Below is the model for socializing. The model for advocacy was identical, with the exception that “socializing activities” was included at Level 1 and Level 2 as a predictor in place of “advocacy activities”.

We identified several significant associations for our socializing model. At the individual level, engaging in more advocacy activities was associated with engaging in more socializing activities (b = 0.23, p < .01). At the group level, GSAs that collectively engaged in more advocacy also reported engaging in more socializing activities (γ = 0.19, p < .01). The coefficients for all independent variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Individual and GSA-Level Factors Associated with Amount of Socializing and Advocacy

| Socializing

|

Advocacy

s |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | |

| Level 1: Individual-Level Factors | ||||

| Sexual orientation | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.19 |

| Race/ethnicity | −0.09 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.18 |

| Membership duration | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.40** | 0.09 |

| Engagement level in GSA | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.43** | 0.10 |

| Perceived school LGBT hostility | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.10 |

| Socializing done | — | — | 0.52** | 0.10 |

| Advocacy done | 0.22** | 0.04 | — | — |

| Social justice self-efficacy | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Level 2: GSA-Level Factors | ||||

| Proportion sexual minorities | −0.003 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Proportion racial/ethnic minorities | 0.00 | 0.005 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Collective perceived school hostility | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.98** | 0.34 |

| Collective socializing done | — | — | 0.53* | 0.23 |

| Collective advocacy done | 0.19** | 0.07 | — | — |

| Collective social justice efficacy | −0.38 | 0.32 | 1.21* | 0.47 |

|

| ||||

| Fit Indices | ||||

| AIC | 1003.7 | 1303.3 | ||

| BIC | 1029.0 | 1328.7 | ||

| −2Ln(Likelihood) | 973.7 | 1273.3 | ||

Note. Unstandardized coefficients are presented with their standard errors (SE). AIC = Akaike Information Criteria; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion. At Level 1 and 2, advocacy done was included as the predictor in the socializing model, while socializing done was included as the predictor in the advocacy model.

p < .05.

p < .01.

As anticipated, we identified a greater number of significant associations for our advocacy model. At the individual level, youth who had been members for a longer duration (b = 0.40, p < .01), who reported greater engagement and investment in GSA meetings (b = 0.43, p < .01), and who also did more socializing activities (b = 0.52, p < .01) reported engaging in more advocacy activities. At the group level, GSAs whose members collectively perceived greater school hostility to LGBT issues (γ = 0.98, p < .01), whose members collectively engaged in more socializing activities (γ = 0.53, p < .05), and whose members collectively reported greater social justice efficacy (γ = 1.21, p < .05) engaged in more advocacy activities. The coefficients for all independent variables are presented in Table 2.

Discussion

Our study aimed to shift from treating GSAs and their members as homogenous to directly consider their diversity. In doing so, we focused on two critical dimensions of GSAs – socializing and advocacy – that correspond with providing ways to build bonding and bridging social capital (Almedom, 2005; Griffin et al., 2004). We found that GSAs and youth varied significantly along these dimensions. Several factors accounted for this variability, with distinct patterns for socializing and advocacy. These findings highlight the utility of applying a systems perspective to the continued study of GSAs and other similar youth settings.

Beyond Uniformity: GSAs Vary in Socializing and Advocacy

GSAs varied substantially along the dimensions of socializing and advocacy. In essence, neither GSAs nor youth members were homogenous, though comparison studies tend to treat GSAs as monolithic and having a singular influence on youth. GSAs were more distinct from one another on advocacy than socializing. Socializing is common and the primary purpose in many youth settings (Eccles & Gootman, 2002). In addition, support and socializing historically have been the focus of GSAs (Griffin et al., 2004). Thus, most GSAs may have sought to prioritize these types of activities, leading to less variability across GSAs.

Levels of socializing and advocacy were associated, which may reflect that some youth simply participate more than others in GSA events. This is not unlike findings for other youth programs (Hansen & Larson, 2007). Similarly, some GSAs may simply be more active than others. This could be due to differences in available resources across socioeconomically diverse schools or to hostility toward some GSAs. Indeed, some advisors report pushback to securing GSA funding, which is a major barrier to their GSA’s functioning (Watson et al., 2010).

Our cross-sectional data limit our ability to test the directionality of the association between socializing and advocacy. However, we suspect socializing and support precede and then co-occur with eventual advocacy such as awareness-raising events or activism to counter systemic discrimination. Socializing may serve first to meet internal needs among members. These activities may build the bonding social capital and “team environment” that make it capable for members to engage in advocacy that further yields bridging social capital. This issue has not been examined well in the literature, but it is now quite relevant as more settings add advocacy initiatives to their mission (Fields & Russell, 2005).

Predicting GSA Variability in Socializing

Though GSAs and youth varied in their levels of socializing, no factors beyond advocacy levels were associated with variability in socializing. Nevertheless, other unmeasured factors may be instrumental. For instance, scheduling conflicts or personal interests may be relevant. Research should distinguish youth who face barriers to involvement from those who selectively access opportunities from multiple sources, one being GSAs. This could be important for GSAs and other groups whose members face adversity (e.g., discrimination) and would benefit from the safety of these settings (Griffin et al., 2004).

The fact that patterns of results differed for socializing and advocacy suggests that it may be insufficient for programs to only consider youths’ overall involvement. This general approach may mask different barriers that impede participation in certain types of activities, and factors that contribute to youths’ engagement in socializing may be distinct from those contributing to their advocacy. Programs may need to attend differentially to facilitating these activities. The bonding and bridging social capital framework (Kim et al., 2006) provides a way to classify and study youths’ participation in these activities in GSAs and other youth programs.

Predicting GSA Variability in Advocacy

A growing number of programs now include advocacy in their focus (Fields & Russell, 2005; Ginwright, 2007; Inkelas, 2004). Yet, few studies have considered what factors account for some settings’ and youths’ greater involvement in advocacy than others. Given that advocacy is associated with wellbeing (Toomey & Russell, 2013), it is essential to ensure that such activities match the needs and abilities of youth so that they can derive the most benefit.

As hypothesized, youth who were more engaged in GSA meetings reported doing more advocacy activities. Greater investment may be critical for youth to engage in advocacy, though not socializing, because advocacy often requires more effort, time, and a high level of public visibility (Russell et al., 2009). There were no sexual orientation or race/ethnicity differences in youths’ advocacy or socializing. With regard to socializing, youth may have engaged in these activities equally, irrespective of sexual orientation or race/ethnicity, because peer bonding is a drive for adolescents in general (Berndt, 2002). Similarly, whether in marginalized or privileged positions, youth in GSAs may be internally motivated to engage in advocacy either in solidarity as an ally or to counter the discrimination they face being in a marginalized population.

GSAs whose youth collectively perceived greater school hostility did more advocacy than other GSAs. Youth in schools with GSAs report greater safety (Heck et al., 2011), but not all schools in which GSAs are based are equally welcoming (Watson et al., 2010). Advocacy often challenges institutional inequality (Fine & Jaffee-Walter, 2007; Russell et al., 2009). In relation to our findings, these efforts from GSAs could have prompted hostility from their schools. Alternatively, pre-existing hostility may have led GSAs to engage in more advocacy. Longitudinal data would aid in understanding this dynamic and inform how GSAs might address hostility, whether as an antecedent or consequent of advocacy. The association points to the need for research on youth settings that serve marginalized populations to attend to how the hostile contexts in which some are embedded shape the experiences of these groups. This issue that has been given much less attention in the general youth programs literature, though it continues to affect GSAs in conservative schools and districts (Mayo, 2008).

GSAs whose youth collectively reported greater social justice efficacy engaged in more advocacy. Collective efficacy, rather than any one individual’s sense of efficacy, may have accounted for variability in advocacy because it likely required many youth with high social justice efficacy to conduct these types of events. Attention to social justice has been limited in the general youth programs literature and in models specifying factors that promote youth participation in these programs (Eccles & Gootman, 2002). Considering the benefits of advocacy not only for GSA members but also non-members in their schools who may face discrimination (Russell et al., 2009; Toomey & Russell, 2013), more attention should be given to youths’ efficacy to engage in advocacy. Adult advisors should not assume youth feel as capable to lead these types of events as they do others (e.g., socializing). Youth training and appropriate adult guidance may be a prerequisite for youth and GSAs to move toward an advocacy focus.

Strengths, Limitations, and Implications

The primary strength of this study was to begin to highlight GSA variability on their two main dimensions of activities: socializing and advocacy. This is also one of the first studies to account for such variability across and within GSAs. These strengths begin to advance our understanding of GSAs and how they function.

We also note limitations to our study. Our data were cross-sectional and non-experimental; thus, we cannot make causal attributions regarding the associations we identified. There could be bi-directional causal relations that build upon one another (e.g., greater social justice efficacy could lead to more advocacy, which could raise youths’ efficacy). Although we could not address this process, our findings do highlight previously unexamined factors to consider in this work. In addition, all data were youth-reported; research should incorporate data from other sources such as GSA advisors. Despite our sample size, there was limited representation of racial/ethnic minority youth and we lacked the ability to disentangle the experiences of particular racial/ethnic groups. Other demographic factors also should be considered such as students’ socioeconomic background or sexual orientation identity disclosure. Future research should also add more robust assessments, as our school hostility index showed lower reliability. Similarly, while our assessment of advocacy included examples of raising awareness and activism meant to challenge engrained systemic oppression (e.g., homophobic harassment), other specific forms of advocacy that directly challenge oppressive policies or that promote affirming policies should be considered. Finally, our sample was limited to students in GSAs that were able to attend regional meetings across Massachusetts. There could be even more variability across GSAs than we documented when considering the reasons other GSAs may have been unable to attend (e.g., facing greater hostility, having fewer financial resources). Because participants were from Massachusetts, it is not a nationally representative sample. Greater distinctions may exist across GSAs when making broader geographic comparisons.

Our findings carry implications for research on GSAs and similar programs. Research on GSAs is at a juncture to take an increasingly nuanced approach to how they and their members are studied. This approach should attend to the diverse experiences of youth who are members of their GSAs and to the varied ways in which GSAs operate. For instance, how do GSAs balance their internal provision of support to members as well as their focus on advocacy that extends beyond immediate members? Research should consider mechanisms by which involvement in various types of activities (e.g., socializing or advocacy) lead to healthy developmental outcomes for youth in GSAs. Finally, research should consider how even broader social systems affect youths’ experiences in GSAs. As examples, studies should consider the effects of the political climate of the community, presence of LGBT protective policies, or level of support from district administrators. As a practical implication, our findings suggest the value of a network of GSAs to provide support and strategies for how these settings may meet the varied needs and interests of diverse members. Ultimately, the movement of research to address these broader and more complex processes will contribute to the identification of best practices for GSAs and related youth settings that stand to benefit the diverse range of youth who participate in them.

Appendix A

Below is the full list of socializing and advocacy activities/events in which students reported their involvement. These were randomly ordered in the survey. Students also were provided space to write in additional activities/events that were coded as socializing or advocacy.

Socializing Activities/Events

BAGLY Prom

Coffee House

Dances

Facebook Page

Halloween Dance

Movie Nights

Poetry Slam

Talent Show

Valentine’s Day Dance

Note. BAGLY (Boston Alliance of LGBT Youth) is a large statewide network of LGBT community-based youth groups in Massachusetts not limited to Boston.

Advocacy Activities/Events

Ally Week

Classroom Presentations

Day of Silence

Decorating School Bulletin Board

Diversity Week

National Coming Out Day

Tabling at Open Houses

Tabling in Cafeteria

T-Shirts/Sweatshirts

Workshops or Conferences

Wristbands/Buttons

Youth Pride

Note. Although T-shirts/sweatshirts and wristband/buttons are not as large-scale or as prominent as school- or community-wide events such as Day of Silence or National Coming Out Day, we confirmed with the GSA Network and GSA advisors that these activities are done with the express intent to raise awareness of LGBT issues in the school, and thus we classified them as advocacy.

Contributor Information

V. Paul Poteat, Boston College.

Jillian R. Scheer, Boston College

Robert A. Marx, Vanderbilt University

Jerel P. Calzo, Boston Children’s Hospital

Hiro Yoshikawa, New York University.

References

- Almedom AM. Social capital and mental health: An interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:943–964. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, Mayes LC. Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Friendship quality and social development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Russell ST, Corliss HL. Sexual-orientation disparities in school: The mediational role of indicators of victimization in achievement and truancy because of feeling unsafe. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:1124–1128. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon W. What is positive youth development? Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;591:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Gootman JA. Community programs to promote youth development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fauth RC, Roth JL, Brooks-Gunn J. Does the neighborhood context alter the link between youth’s after-school time activities and developmental outcomes? A multilevel analysis. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:760–777. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AF, Matjasko JL. The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development: A comprehensive review and future directions. Review of Educational Research. 2005;75:159–210. [Google Scholar]

- Fetner T, Kush K. Gay-Straight Alliances in high schools: Social predictors of early adoption. Youth & Society. 2008;40:114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Fields J, Russell ST. Queer, sexuality, and gender activism. In: Sherrod LR, Flanagan CA, Kassimir R, editors. Youth activism: An international encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 2005. pp. 512–514. [Google Scholar]

- Fine M, Jaffe-Walter R. Swimming: On oxygen, resistance, and possibility for immigrant youth under siege. Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 2007;38:76–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Simpkins SD. Promoting positive youth development through organized after-school activities: Taking a closer look at participation of ethnic minority youth. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gamson J. Silence, death, and the invisible enemy: AIDS activism and social movement “Newness”. Social Problems. 1989;36:351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S. Black youth activism and the role of critical social capital in Black community organizations. The American Behavioral Scientist. 2007;51:403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P, Lee C, Waugh J, Beyer C. Describing roles that Gay-Straight Alliances play in schools: From individual support to social change. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education. 2004;1:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- GSA Network. National directory. n.d Retrieved from http://www.gsanetwork.org.

- Hansen DM, Larson RW. Amplifiers of developmental and negative experiences in organized activities: Dosage, motivation, lead roles, and adult-youth ratios. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:360–374. [Google Scholar]

- Heck NC, Flentje A, Cochran BN. Offsetting risks: High school Gay-Straight Alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. School Psychology Quarterly. 2011;26:161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Inkelas KK. Does participation in ethnic cocurricular activities facilitate a sense of ethnic awareness and understanding? A study of Asian Pacific American undergraduates. Journal of College Student Development. 2004;45:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. Bonding versus bridging social capital and their associations with self rated health: A multilevel analysis of 40 US communities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60:116–122. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.038281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft I, de Leeuw J, Aiken LS. The effect of different forms of centering in hierarchical linear models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30:1–21. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry M. The story of a Salt Lake City Gay-Straight Alliance: Identity work and LGBT youth. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Issues in Education. 2006;4:13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo C. Obscene associations: Gay-straight alliances, the Equal Access Act, and abstinence-only policy. Sexuality Research and Social Policy: A Journal of the NSRC. 2008;5:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo C. Queering school communities: Ethical curiosity and Gay-Straight Alliances. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Issues in Education. 2004;1:23–36. [Google Scholar]

- McCready LT. Some challenges facing queer youth programs in urban high schools: Racial segregation and de-normalizing whiteness. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Issues in Education. 2004;1:37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Miceli M. Standing out, standing together: The social and political impact of Gay-Straight Alliances. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with LGBT adolescents: A call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:673–686. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Sinclair KO, DiGiovanni CD, Koenig BW, Russell ST. Gay-Straight Alliances are associated with student health: A multi-school comparison of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2013;23:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Yoshikawa H, Calzo JP, Gray ML, DiGiovanni CD, Lipkin A, Mundy-Shephard A, Perrotti J, Scheer JR, Shaw MP. Contextualizing Gay-Straight Alliances: Student, advisor, and structural factors related to positive youth development among members. Child Development. 2015;86:176–193. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Russell GM. Motives of heterosexual allies in collective action for equality. Journal of Social Issues. 2011;67:376–393. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST. Queer in America: Citizenship for sexual minority youth. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Muraco A, Subramaniam A, Laub C. Youth empowerment and high school Gay-Straight Alliances. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:891–903. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9382-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM. Research on adolescent sexual orientation: Development, health disparities, stigma, and resilience. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:256–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Yoshikawa H, editors. Towards positive youth development: Transforming schools and community programs. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA. Safer sexual diversity climates: Lessons learned from an evaluation of Massachusetts Safe Schools Program for gay and lesbian students. American Journal of Education. 2003;110:58–88. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Russell ST. Gay-Straight Alliances, social justice involvement, and school victimization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer youth: Implications for school well-being and plans to vote. Youth & Society. 2013;45:500–522. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11422546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Russell ST. High school gay-straight alliances (GSAs) and young adult well-being: An examination of GSA presence, participation, and perceived effectiveness. Applied Developmental Science. 2011;15:1–11. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2011.607378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Harding SR, Siers B, Olson BD. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Social Justice Scale. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;50:77–88. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng V, Seidman E. A systems framework for understanding social settings. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;39:217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe V. Project 10: A school-based outreach to gay and lesbian youth. High School Journal. 1994;77:108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Walls NE, Kane SB, Wisneski H. Gay-Straight Alliances and school experiences of sexual minority youth. Youth and Society. 2010;41:307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Warren MR, Mapp KL. A match on dry grass: Community organizing as a catalyst for school reform. Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Watson LB, Varjas K, Meyers J, Graybill EC. Gay-Straight Alliance advisors: Negotiating multiple ecological systems when advocating for LGBTQ youth. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2010;7:100–128. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HB, Little PMD, Bouffard SM. More than just being there: Balancing the participation equation. New Directions for Youth Development. 2005;105:15–31. doi: 10.1002/yd.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]