Abstract

The obligate intracellular bacterium, Wolbachia pipientis (Rickettsiales), is a widespread, vertically transmitted endosymbiont of filarial nematodes and arthropods. In insects, Wolbachia modifies reproduction, and in mosquitoes, infection interferes with replication of arboviruses, bacteria and plasmodia. Development of Wolbachia as a tool to control pest insects will be facilitated by an understanding of molecular events that underlie genetic exchange between Wolbachia strains. Here, we used nucleotide sequence, transcriptional and proteomic analyses to evaluate expression levels and establish the mosaic nature of genes flanking the T4SS virB8-D4 operon from wStr, a supergroup B-strain from a planthopper (Hemiptera) that maintains a robust, persistent infection in an Aedes albopictus mosquito cell line. Based on protein abundance, ribA, which contains promoter elements at the 5′-end of the operon, is weakly expressed. The 3′-end of the operon encodes an intact wspB, which encodes an outer membrane protein and is co-transcribed with the vir genes. WspB and vir proteins are expressed at similar, above average abundance levels. In wStr, both ribA and wspB are mosaics of conserved sequence motifs from Wolbachia supergroup A- and B-strains, and wspB is nearly identical to its homolog from wCobU4-2, an A-strain from weevils (Coleoptera). We describe conserved repeated sequence elements that map within or near pseudogene lesions and transitions between A- and B-strain motifs. These studies contribute to ongoing efforts to explore interactions between Wolbachia and its host cell in an in vitro system.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00203-015-1154-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Wolbachia, LC–MS/MS, Proteomics, Mosaic genes, T4SS, RibA, RibB, WspB

Introduction

Wolbachia pipientis (Rickettsiales; Alphaproteobacteria) is an obligate intracellular bacterium that infects filarial nematodes and a wide range of arthropods including ≥60 % of insects and ≈35 % of isopod crustaceans, but does not infect vertebrates (Hilgenboecker et al. 2008). Wolbachia is considered to be a single species classified into clades by multilocus sequence typing and designated as supergroups A to N (Baldo et al. 2006b; Comandatore et al. 2013; Lo et al. 2007). The C- and D-strains that infect filarial worms have phylogenies concordant with those of nematode hosts, consistent with strict vertical transmission as obligate mutualists (Comandatore et al. 2013; Dedeine et al. 2003; Li and Carlow 2012; Strubing et al. 2010; Taylor et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2004). Although arthropod-associated A- and B-strains may provide subtle fitness benefits to hosts (Zug and Hammerstein 2014), they are best known as reproductive parasites, causing phenotypes that maintain or increase Wolbachia infection frequencies, including feminization, parthenogenesis, and cytoplasmic incompatibility (Saridaki and Bourtzis 2010; Werren et al. 2008). Interference with host immune mechanisms and replication of arboviruses, bacteria and malarial plasmodia (Kambris et al. 2009; Pan et al. 2012; Zug and Hammerstein 2014) has encouraged efforts to exploit Wolbachia for biocontrol of arthropod vectors of vertebrate pathogens and/or crop pests (Bourtzis 2008; Rio et al. 2004; Sinkins and Gould 2006; Zabalou et al. 2004). An understanding of molecular differences between A- and B-strains, and how they have been influenced by horizontal transmission and genetic exchange (Newton and Bordenstein 2011; Schuler et al. 2013; Werren et al. 2008; Zug and Hammerstein 2014) will facilitate manipulation of Wolbachia.

Wolbachia’s interaction with host cells likely involves the type IV secretion system (T4SS), a macromolecular complex that transports DNA, nucleoproteins and “effector” proteins across the microbial cell envelope into the host cell, where they mediate intracellular interactions (Alvarez-Martinez and Christie 2009; Zechner et al. 2012). Homologs of all genes except virB5 of Agrobacterium tumefaciens T4SS have been identified in Wolbachia and other members of the Rickettsiales (Gillespie et al. 2009, 2010), including Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Neorickettsia, Orientia and Rickettsia. Among sequenced Wolbachia genomes, T4SS genes are organized in two operons: virB3-B6 containing virB3, virB4 and four virB6 paralogs and virB8-D4 containing virB8, virB9, virB10, virB11, virD4 and, in some genomes, the wspB paralog of the wspA major surface antigen (Pichon et al. 2009; Rances et al. 2008). In the supergroup B-strain wPip from Culex pipiens mosquitoes, wspB is disrupted by a transposon and is presumably inactive (Sanogo et al 2007). T4SS effector proteins that manipulate host cells have been identified from Anaplasma and Ehrlichia (Liu et al. 2012; Lockwood et al. 2011; Niu et al. 2010), and Wolbachia express both vir operons in ovaries of arthropod hosts, wherein T4SS effectors are suspected to play a role in cytoplasmic incompatibility and other reproductive distortions (Masui et al. 2000; Rances et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2004). Although WspA and WspB are likely components of the Wolbachia outer membrane, their functions remain unknown. In the case of wBm, WspB is excreted/secreted into filarial host cells (Bennuru et al. 2009) and co-localizes with the Bm1_46455 host protein in tissues that include embryonic nuclei (Melnikow et al. 2011). WspB is therefore itself a candidate T4SS effector that may play a role in reproductive manipulation of the host.

The Wolbachia strain wStr in supergroup B causes strong cytoplasmic incompatibility in the planthopper, Laodelphax striatellus (Noda et al. 2001a), and in addition maintains a robust, persistent infection in a clonal Aedes albopictus mosquito cell line, C/wStr1 (Fallon et al. 2013; Noda et al. 2002). Because in vitro studies with wStr provide advantages of scale and ease of manipulation for exploring mechanisms that may facilitate transformation and genetic manipulation of Wolbachia, we have undertaken proteomics-based studies that provide strong support for expression of T4SS machinery in cell culture. Here, we report the sequence of the virB8-D4 operon, including flanking genes ribA, upstream of virB8, and wspB downstream of virD4. We show that wspB is intact, describe protein structure predicted from the deduced WspB sequence, and verify co-transcription of wspB with upstream vir genes. Relative abundance levels of WspB and the VirB8-D4 proteins in wStr are well above average, while RibA is among the least abundant of MS-detected proteins. In wStr, ribA and wspB are mosaics of sequence motifs that are differentially conserved in supergroup A- (WOL-A) and B- (WOL-B) strains, and they contain conserved 8-bp repeat elements that may be associated with genetic exchange. Finally, we discuss implications for functional integration of the Wolbachia T4SS with WspB and with the riboflavin biosynthesis pathway enzymes GTP cyclohydrolase II (RibA) and dihydroxybutanone phosphate synthase (RibB).

Materials and methods

Cultivation of cells

Aedes albopictus C7-10 and C/wStr1 cells were maintained in Eagle’s minimal medium supplemented with 5 % fetal bovine serum at 28–30 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere (Fallon et al. 2013; Shih et al. 1998). Cells were harvested during exponential growth, under conditions favoring maximal recovery of Wolbachia (Baldridge et al. 2014).

Polymerase chain reaction, cloning and DNA sequencing

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to amplify wStr genes from DNA extracts prepared from Wolbachia enriched by fractionation of C/wStr1 cells on sucrose density gradients and recovered from the interface between 50 and 60 % sucrose (Baldridge et al. 2014). Template DNA was used to obtain 21 PCR products using a panel of 31 primers (Table S1), GoTaq™ DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI), and a Techne TC-312 cycler (Staffordshire, UK). Cycle parameters were: 1 cycle at 94 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles at 94 °C for 35 s, 53 °C for 35 s, 72 °C for 1 min, followed by 1 cycle at 72 °C for 5 min. Extension time was increased to 2 min for products ≥1000 bp. PCR products were cloned in the pCR4-TOPO vector with the TOPO-TA Cloning Kit for Sequencing (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), and two or more clones each were sequenced at the University of Minnesota BioMedical Genomics Center.

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was purified from A. albopictus C7-10 and C/wStr1 cells using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies) and treated with DNase I (RNase-free; Life Technologies) followed by heat inactivation, as suggested by the manufacturer. RT-PCR was executed with primers virD4F1764–1784 and wspBR152–172 (Table S1) using the RNA PCR Core Kit (Life Technologies) as suggested by the manufacturer with the exception that synthesized cDNA was treated with DNase-inactivated RNaseA before the final PCR reaction. The PCR reaction included 1 cycle at 95 °C for 4 min, 35 cycles at 95 °C for 35 s, 56 °C for 40 s, 72 °C for 40 s, followed by 1 cycle at 72 °C for 3 min. Reaction products were electrophoresed on 1 % agarose gels, cloned, and sequenced as above.

Sequence alignments and protein structure prediction

DNA and protein sequence alignments were executed with the Clustal Omega program (Sievers et al. 2011). Alignments were edited by visual inspection and modified in Microsoft Word. WspB protein structure predictions were obtained using tools available at www.predictprotein.org, including the PROFtmb program (Dell et al. 2010) for prediction of bacterial transmembrane beta barrels (Bigelow et al. 2004) and per-residue prediction of up-strand, down-strand, periplasmic loop and outer loop positions of residues. The PROFisis program (Ofran and Rost 2006) was used to predict WspB amino acid residues that are potentially involved in protein–protein interactions. Trees were produced using PAUP* version 4 (Swofford 2002). Amino acids were aligned with Clustal W, using pairwise alignment parameters of 25/0.5 and multiple alignment parameters of 10/0.2 for gap opening and gap extension, respectively. The protein weight matrix was set to Gonnet. The alignment was saved as a nexus file and loaded into PAUP*, and the trees were created using a heuristic search with the criterion set to parsimony. Bootstrap 50 % majority-rule consensus trees are based on 1000 replicates, with wBm (WOL-D) as the outgroup.

Mass spectrometry, peptide detection, protein identification and statistical analysis

Mass spectrometry data, generated using LC–MS/MS on LTQ and Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometers as four data sets, were described previously (Baldridge et al. 2014). The MS search database was modified to include deduced ORFs from wStr sequence data described herein. All tests of association were performed with SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC; http://www.sas.com/en_us/home.html/).

Results

Structure of the wStr virB4-D8 operon

The robust, persistent infection of A. albopictus mosquito cell line, C/wStr1 with BwStr (in the text below, strain designations are denoted by superscripts), isolated from the planthopper L. striatellus, provides an in vitro model to identify proteins that modulate the host–microbe interaction. A potential role for the T4SS is supported by strong representation of peptides from VirB8, VirB9, VirB10, VirB11, VirD4 (Table 1) and associated proteins in the BwStr proteome (Baldridge et al. 2014). Despite its emergence as a useful strain that grows well in vitro, the BwStr genome is not yet available. In Wolbachia strains for which genome annotation is available, gene order within the virB8-D4 operon is conserved. Based on transcriptional analyses in the related genera, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia (Pichon et al. 2009), the promoter likely maps within the 3′-end of ribA extending into the intergenic spacer (Fig. 1a, black horizontal arrow at left) and is followed by five consecutive vir genes (Fig. 1b). In BwPip from Culex pipiens mosquitoes, wspB is disrupted by insertion of an IS256 element that encodes a transposase on the opposite strand (Fig. 1a, at right; Sanogo et al. 2007). Because VirB8-D4 proteins were highly similar to homologs from BwPip (Baldridge et al. 2014), we evaluated wspB in BwStr and its potential expression as a virB8-D4 operon member, as is the case in AwMel and AwRi from Drosophila spp. and AwAtab 3 from the wasp Asobara tabida (Rances et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2004). In the original proteomic analysis, three WspB peptides (Fig. 1a, tall black and gray arrows represent 95 and 94 % confidence peptides, respectively) mapped proximal and distal to the transposon insertion in BwPip, while the absence of peptides corresponding to the transposon suggested that wspB is intact in BwStr.

Table 1.

MS-detected peptides from wStr proteins encoded by ribA, ribB and the virB8-D4 operon

| Protein | akDa | bPep(1) | bPep(2) | bPep(T) | cCov. | dRAL | eSR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RibA | 41 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0.5 | −2.30 |

| RibB | 24 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 89 | 7.0 | 1.20 |

| VirB8 | 26 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 58 | 5.0 | 0.59 |

| VirB9 | 31 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 45 | 6.2 | 0.84 |

| VirB10 | 54 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 53 | 8.8 | 0.94 |

| VirB11 | 37 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 42 | 7.0 | 0.82 |

| VirD4 | 77 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 26 | 6.2 | 0.45 |

| WspB | 31 | 2f | 11 | 50 | 7.2 | 1.08 |

aProtein mass in kilodaltons. b Number of 95 % confidence unique peptides; (1) designates original search [7]; (2) designates a refined search in which the database included peptides based on the present wStr nucleotide sequence data; (T) combined total peptides from both searches. c Percent protein sequence coverage represented by detected peptides. d Mean number of peptides from four independent MS data sets. e Studentized residual based on the modified univariable model of the refined search (Table S3, column R); SR value 0 indicates average abundance protein, 0–1 above average, 1–2 abundant and >2 highly abundant. Values below 0 indicate lower than average abundance. f A 94 % confidence peptide indicated in Fig. 1A did not meet the threshold for proteome inclusion in the original search. For VirB10, one originally detected peptide was absent from the refined search

Fig. 1.

Schematic map of the Wolbachia T4SS virB8-D4 operon and cloning strategy for the ribA to topA sequence from B wStr. a Left expanded view of the B wStr ribA ORF depicted as an arrow showing the direction of transcription. Black horizontal arrow indicates a putative promoter that extends into an intergenic spacer (black rectangle). Black arrowheads indicate positions of MS-detected unique peptides (95 % confidence). Gradient shading from white to black designates 5′-sequence identity resembling WOL-A transitioning to 3′-sequence more closely resembling WOL-B-strains. a Right expanded view of the interrupted wspB homolog in B wPip. Black ellipses indicate positions of IS256 inverted repeat elements flanking a 1.2-kb insertion encoding a MULE domain superfamily transposase (gi|190571636; pfam10551) on the opposite strand (indicated by the direction of the open arrow); flanking gray shading indicates wspB. Tall vertical black and gray arrowheads indicate positions of unique peptides (95 and 94 % confidence, respectively) identified in the original MS data search. Small gray arrows indicate 95 % confidence peptides matched in a refined data set (including the B wStr sequence described here) that are conserved in WOL-B-strains, and open arrowheads with stars indicate peptides unique to B wStr. b Schematic depiction of the Wolbachia virB8-D4 operon and flanking genes with arrows designating the direction of transcription. Vir genes are designated in white font on a black background; black squares indicate intergenic spacers. Gradient shading indicates mosaic structure of an intact wspB in B wStr. c Filled lines above the 10-kb scale marker represent cloned PCR amplification products (see Table S1 for primers) that were sequenced and assembled into the B wStr ribB and ribA–topA consensus sequence. The double slash symbols at left indicate that ribB is not contiguous with downstream genes. The open box indicates the RT-PCR amplification product from Fig. 2. d BLASTn alignment of the 9133-bp B wStr ribA–topA sequence to corresponding sequences in B wVitB B wPip, B wVulC, A wRi, A wMel and D wBm genomes. Dark filled lines indicate sequence identity >70 %; light lines indicate low sequence identity, and the open space in B wPip represents an alignment gap

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence comparisons

To examine the virB4-D4 operon in BwStr, we sequenced overlapping PCR products from 20 primer pairs (Table S1) spanning 9.1 kb beginning 43 bp downstream of the 5′-end of ribA in other Wolbachia strains and ending within topA encoded immediately downstream of the operon on the opposite strand (Fig. 1b, c). With the notable exception of the BwPip transposon, the nucleotide sequence aligned most closely to homologous sequences from BwVitB and BwPip. In addition, we noted variability in an ~0.3-kb region of virB10 in BwStr that was conserved in BwVitB, BwPip and AwRi, but not in BwVulC, AwMel and DwBm (Fig. 1d; see Table S2 for GenBank Accessions).

Pairwise sequence comparisons of the virB8-D4 operon from BwStr to homologs from Wolbachia supergroup A, B, C, D and F strains (Table 2) confirm that virB10, with nucleotide identities ranging from 74–99 %, is the least conserved of the five vir genes, and we note that Klasson et al. (2009) attributed divergence of virB10 in AwMel and AwRi to genetic exchange with a WOL-B-strain. Collectively and as individuals, the vir genes from BwStr have the highest nucleotide identities (~99 %) with BwVitB and BwPip. Identities with five A-strains are lower (range 87–91 %), lower yet (range 80–89 %) with the F-strain, FwCle and fall to a range of 74–88 % with three nematode-associated strains, DwBm, CwOo and CwOv. At the 5′-end of the operon, ribA was distinct, with approximately equivalent nucleotide identity with homologs from A- and B-strains (range 91–94 %), while the partial sequence of topA downstream of the operon had a conservation pattern similar to that of the vir genes. In some comparisons, virB8, virB11, virD4 and topA amino acid identities exceed nucleotide identities. Although ribB is not physically adjacent to the virB8-D4 operon in annotated Wolbachia genomes, ribB from BwStr is most similar to homologs from BwNo (97 % nucleotide identity) and AwMel (90 %), but was exceptional because identities with three other insect-associated A- and B-strains (~80 %) were lower than with F-, C- and D-strains (range 85–87 %). Consistent with earlier proteomic data (Baldridge et al. 2014), in all comparisons that discriminate between A- and B-strains, BwStr resembled WOL-B, while variability in ribA and wspB flanking the virB8-D4 genes exceeded that of the vir genes themselves.

Table 2.

Pairwise nucleotide and amino acid comparisons

| Gene | B wPiP | B wVitB | B wNo | BwTai | B wVulC | A wMel | A wRi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | |

| ribAa | 94 | 89 | 94 | 89 | 93 | 88 | 94 | 90 | 93 | 92 | 93 | 91 | 92 | 89 |

| virB8 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 94 | 94 | 88 | 86 | 88 | 87 |

| virB9 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 98 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 94 | 93 | 91 | 89 | 91 | 89 |

| virB10 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 98 | 90 | 86 | 98 | 96 | 88 | 74 | 87 | 74 | 88 | 85 |

| virB11 | 99 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 96 | 98 | 97 | 99 | 90 | 93 | 89 | 95 | 89 | 95 |

| virD4 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 94 | 97 | 89 | 92 | 89 | 93 |

| wspB | 56 | xx | 98 | 96 | 85 | 68 | – | – | – | – | 85 | 70 | 85 | 70 |

| topAa | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 99 | – | – | – | – | 88 | 87 | 87 | 86 |

| ribB a | 81 | 80 | – | – | 97 | 96 | – | – | – | – | 90 | 91 | 79 | 78 |

| Gene | A wAna | A wKue | A wAtab3 | F wCle | D wBm | C wOo | CwOv | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | N | AA | |

| ribAa | 91 | 88 | 93 | 91 | – | – | 84 | 81 | 83 | 80 | 82 | 74 | 82 | 75 |

| virB8 | 88 | 87 | 88 | 86 | 88 | 88 | 85 | 83 | 85 | 81 | 83 | 81 | 84 | 82 |

| virB9 | 91 | 89 | 91 | 89 | 91 | 89 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 82 | 76 | 81 | 76 |

| virB10 | 88 | 84 | 87 | 74 | 87 | 73 | 80 | 71 | 84 | 70 | 76 | 64 | 74 | 64 |

| virB11 | 89 | 95 | 89 | 95 | 89 | 95 | 89 | 95 | 88 | 94 | 86 | 89 | 87 | 89 |

| virD4 | 89 | 93 | 89 | 93 | 88 | 92 | 87 | 92 | 87 | 87 | 86 | 91 | 88 | 94 |

| wspB | 83 | 68 | 85 | 70 | 85 | 70 | 72 | xx | 73 | 61 | 72 | 49 | 71 | 49 |

| topAa | 86 | 85 | – | – | – | – | 88 | 92 | 86 | 88 | 84 | 83 | 84 | 88 |

| ribB a | 80 | 88 | – | – | – | – | 87 | 87 | 86 | 87 | 85 | xx | 85 | xx |

Wolbachia strains from supergroups A, B, C, D and F are indicated by superscripts, with percentages of nucleotide (N) and amino acid (AA) sequence identities to B wStr. Dashes indicate sequences not available, and xx indicates pseudogenes; GenBank Accession numbers are given in Table S2

aPartial gene and protein sequences: ribA 1040 bp, ribB 592 bp; topA 825 bp. Host associations: wPip, Culex pipiens—mosquito; wVitB, Nasonia vitripennis—wasp; wTai, Teleogryllus taiwanensis—cricket; wVulC, Armadillidium vulgare—isopod; wMel, wRi, wAna, wNo, Drosophila spp.—fruit fly; wKue, Ephestia kuehniella—moth; wAtab 3 Asobara tabida—wasp; wBm, wOo and wOv from filarial nematodes Brugia malayi, Onchocerca ochengi and O. volvulus, respectively. In the comparison, values of 97 % or greater are shown in italics

Expression and relative abundances of the BwStr virB4-D8 proteins

To refine an earlier original proteomic analysis (Baldridge et al. 2014), we incorporated the PCR-amplified BwStr sequences described here to the database for peptide identification [Table 1, see column labeled Pep(2)]. Statistical analysis indicated that in a univariable model, protein molecular weight was weakly (r2 = 0.2221) but significantly (p < 0.0001) associated with peptide count: log(peptides) = −0.40247 + 0.4953 × log(MW). Estimations of protein relative abundance levels (RAL) based on peptide counts were therefore normalized to protein length using studentized residuals (SR), a measure of deviance from expected values adjusted for estimated SD from the mean. All peptide data and SR values in the univariable and multivariable models of the original and refined searches are detailed in Table S3.

In the refined search, we identified eight new peptides from Vir proteins [Table 1, compare columns labeled Pep(2) to Pep(1)], including three from the most divergent VirB10. In aggregate, the five Vir proteins had a mean (SD) SR of 0.73 (0.2) and are expressed at above average abundance. We identified five new peptides from RibB, but none from RibA (Table 1). RibB has an SR of 1.2 and is an abundant protein, while RibA has an SR of −2.3 and is among the least abundant of MS-detected proteins. Nine new peptides from the highly divergent WspB (see below) generated an SR of 1.08, slightly above the threshold (>1.0) for an abundant protein and roughly equivalent to SR values (range 1–1.17) of housekeeping proteins such as isocitrate dehydrogenase, ftsZ, ATPsynthase F0F1 α subunit, and ribosomal proteins S2, S9, L3, L7/L12 and L14 (Table S3). In comparison, WspA with an SR of 2.17 (Table S3, entry 63) ranked as highly abundant, and the most abundant protein in the proteome was the GroEL chaperone (entry 586), with an SR of 3.66.

Reverse transcriptase PCR confirms co-transcription of wspB with vir genes

Similar SR values for WspB, relative to VirB8-D4, were consistent with evidence that wspB is co-transcribed with virB8-D4 in AwMel, AwRi and AwAtab 3 (Rances et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2004). We used RT-PCR with RNA template verified by PCR to be free of DNA contamination (Fig. 2b, lanes 2 and 3) to amplify a 528-bp product that was produced in reactions containing RNA from C/wStr1 cells (Fig. 2a, lane 4), but not in negative control reactions (lanes 1 and 2) or those with RNA from C7-10 cells (lane 3). Its sequence matched the expected BwStr genomic sequence (Fig. 1c, RT-PCR box at right), confirming that in BwStr, wspB is a member of the virB8-D4 operon.

Fig. 2.

Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analysis shows co-transcription of wspB with virD4. a Lanes 1 and 2 RT-PCR negative controls with no RNA or with no reverse transcriptase, respectively. Lanes 3 and 4 RT-PCR of RNA from uninfected C7-10 and infected C/wStr1 cells, respectively, with virD4 forward and wspB reverse primers. Lane 5 RT-PCR positive control with C/wStr1 RNA and Wolbachia primers S12F/S7R, which amplify portions of a ribosomal protein operon described previously (Fallon 2008). b Lane 1 PCR negative control with no Taq enzyme. Lanes 2 and 3 negative control lacking RT, with RNA from uninfected C7-10 and infected C/wStr1 cells, respectively

In BwStr, ribA is a mosaic of conserved WOL-A and WOL-B sequence motifs

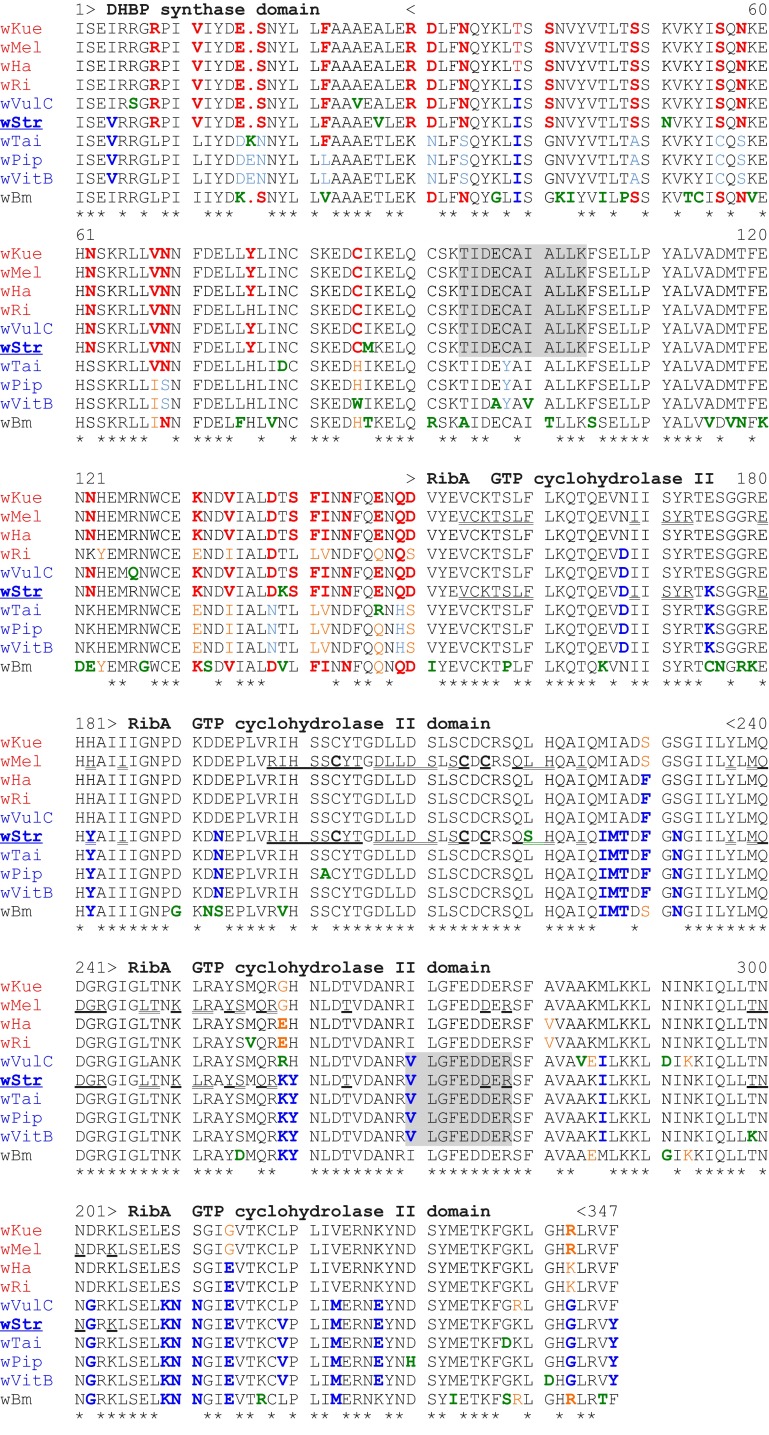

The ribA nucleotide sequence has been shown to contain regulatory elements for expression of the T4SS operon in Anaplasma and Ehrlichia (Ohashi et al. 2002; Pichon et al. 2009). In contrast to highest homologies of BwStr virB8-D4 genes to WOL-B-strains, ribA sequence identities showed little difference between WOL-A and -B homologs (Table 2), but the two MS-detected peptides corresponded to AwMel and BwPip homologs, respectively (Fig. 1a). Alignment of amino acids from 10 RibA homologs (Fig. 3; WOL-A and WOL-B-strains are identified at left in red and blue, respectively) suggested that BwStr RibA is a two-part mosaic, each containing a protein functional domain.

Fig. 3.

Amino acid sequence alignment of RibA homologs from B wStr and Wolbachia supergroups A (red), B (blue) and D (black) respectively. Asterisks below the alignment indicate universally conserved residues. Unique residues are in green font. Residues conserved in B wStr and a majority of B-strains are in dark blue, bold font, while those in dark red, bold font are conserved with a majority of A-strains. Residues conserved in two to four strains are in light blue, orange or orange bold font. Residues highlighted in gray correspond to 95 % confidence peptides detected by LC–MS/MS. The dihydroxybutanone phosphate synthase (RibB) and GTP cyclohydrolase II domains (RibA) are indicated above the alignment within greater than less than symbols. Bold underlined residues in A wMel and B wStr indicate conserved active site amino acids, including critical cysteine residues. Double underlined residues indicate amino acids involved in the dimerization interface. See Tables 2 and S2 for host associations and GenBank Accessions. The PCR-amplified B wStr sequence does not encode the N-terminal amino acids; position 1 corresponds to the 15th amino acid

The amino terminal 150 residues in BwStr RibA (Fig. 3) include a short dihydroxybutanone phosphate synthase domain and the first detected peptide (residues 94–104). This portion of BwStr RibA matched sequences from the four A-strains and a single B-strain, BwVulC, at 29 of 36 variable amino acids (shown in red), while only three (4, 39 and 168 in blue) matched the other three B-strains and four (in green) were unique. In contrast, the C-terminal 151–347 residues, encompassing the second peptide (residues 250–258) within a GTP cyclohydrolase domain, included a single amino acid unique to BwStr, while 23 (in blue) uniformly matched B-strains except BwVulC, which continued to resemble the A-strains until residue 239. Among the four A-strains, the BwRi homolog is most similar throughout the alignment to the B-strains, but within residues 129–150 immediately preceding the cyclohydrolase domain, it closely matched BwTai, BwPip and BwVitB, while BwStr and BwVulC matched the other three A-strains. In aggregate, the alignment suggested that the BwStr and BwVulC homologs are two-part mosaics, each containing a protein functional domain, with an N-terminal WOL-A motif and a C-terminal WOL-B motif. We note that the C-terminal B-strain motif is consistent with the B-strain identity of the downstream virB8-D4 operon (Table 2) and includes the predicted promoter region (Ohashi et al. 2002; Pichon et al. 2009). Likewise, in a phylogenetic comparison (Fig. 4), trees representing the full length and N-terminal regions (top and bottom left) show BwVulC and BwStr in adjacent positions, and grouped more closely with WOL-A-strains. In the C-terminus, where the amino acid alignment shows an overall higher consensus (Fig. 3), BwStr grouped with the B-strains including BwPip, while BwVulC appears more closely related to A-strains.

Fig. 4.

Phylogenic relationships of B wStr RibA protein with homologs from WOL-A- and WOL-B-strains. Consensus trees show bootstrap values based on 1000 replicates, with D wBm (WOL-D) as the outgroup. WOL-A-strains are shown in black font boxed against a white background. WOL-B-strains are shown in white font on a black background. Open arrows designate BwVulC and closed arrows indicate B wStr. The N-terminal alignment corresponded to the first 150 residues in Fig. 3; the remainder of the protein was included in the C-terminal alignment

Nucleotide alignment and phylogenetic comparisons show that ribA is a mosaic gene in BwStr and BwVulC

A nucleotide alignment (Fig. S1) confirmed that ribA from BwStr is a two-part mosaic of WOL-A and WOL-B sequence motifs that correspond to the N- and C-terminal halves of the protein. In the first 522 nucleotides of ribA, 45 (in red font) of 56 variable nucleotides in BwStr match the A-strain sequences (Fig. S1), but only six (in blue) match the majority of B-strains and two are unique to BwStr (in green). In the downstream 522 nucleotides of ribA, 51 (in blue) of 54 variable nucleotides in BwStr match B-strains, while a single nucleotide (684 in red) matches the A-strains and two (in green) are unique to BwStr. In BwVulC, ribA has a similar two-part mosaic structure but does not firmly transit from the WOL-A to the WOL-B sequence motif until position 775, consistent with the amino acid alignment. Among the A-strains, ribA from AwRi is again most similar to the B-strain sequences. Within nucleotides 387–453 encoding amino acids 129–150 just before the cyclohydrolase domain and the A/B-strain sequence motif transition in BwStr, 13 of 18 WOL-A/B variable nucleotides in AwRi are shared with BwTai, BwPip and BwVitB, but those of BwStr and BwVulC are conserved with the other A-strains (orange and black vs. red residues, respectively).

WspB in BwStr is strikingly similar to a AwCobU4-2 homolog

Having shown that wspB is intact in BwStr, we mapped 11 peptides onto amino acid sequences encoded by 12 homologs (Fig. 5), including sequences deduced from three open reading frames (ORFs) in the wspB pseudogene from BwPip (Sanogo et al. 2007) and two overlapping ORFs in a pseudogene from AwCobU4-2, one of several WOL-A variants associated with the weevil, Ceutorhynchus obstrictus. Of two BwStr peptides (Fig. 5) detected at 95 % confidence in the original search (Baldridge et al. 2014), the first (residues 105–115 in gray) was identical in all strains except BwNo, which has unique M/I and V/I substitutions (residues in green). The second peptide (residues 209–220) is identical in all but the two AwCob strains that share an M/R substitution (215 in orange), while AwCobU4-2 has a unique Y/C substitution (219 in green). Five additional BwStr peptides (highlighted in cyan) were identical with BwVitB and BwMet (residues in blue), but not with BwPip and BwNo, which have many residues that are unique (in green) or shared (in orange) only with AwCobU5-2 and AwAna. Thus, with the exception of AwCobU5-2, cyan peptides of BwStr match other WOL-B-strains.

Fig. 5.

Amino acid sequence alignment of WspB homologs. At left, font color designates WOL-A (red) and B (blue) strains, and the B wStr sequence is the top listed Wol-B-strain. Asterisks below alignment indicate universally conserved residues; three hypervariable regions (HVRs) are doubly underlined above the alignment. Blocks of coloring designate peptides detected by LC–MS/MS at the 95 % confidence level. Those in gray were conserved in A- and B-strains. Cyan designates peptides conserved in B-strains, and yellow, those conserved in B wStr and A wCobU4-2. Olive peptides were unique to B wStr. Residues conserved between B wStr and a majority of A-strains are in red font (a single proline at residue 193) and residues conserved with a majority of B-strains are in blue font. Unique residues are in green font, and residues conserved between two or three homologs are in orange font. Underlined residues below the alignment denote the breakpoints between contiguous peptides within sequence regions. The greater than and less than symbols below the alignment indicate a transposon insertion in the wspB pseudogene of B wPip, followed by two additional deduced ORFs—see Fig. S2. PROFtmb (prediction of transmembrane beta barrels) symbols for individual residues below the alignment are: U—up-strand, D—down-strand, I—periplasmic loop, O—outer loop. PROFisis (prediction of protein–protein interaction residues) symbol P designates interaction residues. Wolbachia strain host associations: A wAtab 3, A. tabida—wasp; A wCob, C. obstrictus—weevil; B wMet, Metaseiulus occidentalis—predatory mite. See Tables 2 and S2 for other host associations and GenBank Accessions. The first 20 residues of theA wCob and B wMet sequences are not available

Two peptides underscore a striking similarity between the BwStr and AwCobU4-2 homologs. The first (Fig. 5, residues 133–140 highlighted in yellow) contains an alanine residue (138 in bold orange) shared only with AwCobU4-2. The second (residues 169–186 highlighted in olive) has a unique F/L substitution (in green) and a V/I substitution (in orange) shared with AwCobU4-2 and AwAna. Overall, the BwStr and AwCobU4-2 sequences differ at only five residues (59, 172, 193, 215 and 219), of which four occur within hypervariable regions. Throughout the alignment, AwAtab 3, AwKue, AwMel and AwRi form a conserved group, but the divergent AwAna and AwCobU4-2 and U5-2 strains have multiple residues (in blue, as in 42–77 and 224–277) that are conserved with the B-strains, suggesting genetic exchange between supergroups.

WspB domain structure and hypervariable regions (HVRs)

WspB is a paralog of the better-known WspA major surface antigen, which is anchored in the cell envelope by a transmembrane β-barrel domain (Koebnik et al. 2000), while surface-exposed loop domains contain HVRs with high recombination frequencies within and between strains (Baldo et al. 2010). The PROFtmb program predicted 10 transmembrane down (D)- and up (U)-strands and six periplasmic space (I) strands in WspB from BwStr (Fig. 5; residues indicated by D, U and I, respectively; Z score of 6.8 supports designation as transmembrane β-barrel protein). HVR1 and HVR2 each contain a predicted outer loop (residues 38–86 and 115–156 indicated by O) with high proportions of amino acids that are potentially charged at physiological pH; HVR3 contains two outer loops. Finally, a small predicted loop that is not within an HVR contains a proline (residue 193) that is conserved in BwStr and four WOL-A-strains. It is one of the 20 amino acids, most with hydrophilic or potentially charged side chains and within HVRs or adjacent to periplasmic space strands, predicted by the PROFisis program to be potentially involved in protein–protein interactions (P below alignment).

HVR1 amino acids

In HVR1 (Fig. 5, residues 41–77), eight residues are universally conserved among all homologs, while the majority of variable residues are differentially conserved in the B-strains (residues in blue) versus the A-strains. However, the sequences from the AwAna and AwCobU5-2 A-strains are mosaics in which eight of the first 20 residues (in blue) are conserved with all B-strains, while eight others are either conserved mutually or with BwNo or BwPip (in orange). Within the remaining 17 residues of HVR1, the AwAna and AwCobU5-2 sequences are better conserved with the other A-strains, while BwNo and BwPip have multiple unique residues (in green). The AwCobU4-2 and BwStr sequences differ only at residue 59.

HVR2 amino acids

Within HVR2 (Fig. 5, residues 121–150), AwCobU5-2 and AwAna sequences have alignment gaps at four residues, five or six unique residues respectively (in green), and eight residues that are either conserved mutually (in orange) or with BwNo. The BwPip pseudogene has only the first two residues of HVR2 due to a transposon insertion (indicated below alignment by greater than less than symbols). The AwCobU4-2 pseudogene contains a nucleotide sequence duplication (see below) that results in an overlap of the first and third ORFs beginning at the seventh residue of HVR2, but their spliced sequences, as shown, are identical to that of BwStr. The BwNo sequence has eight alignment gaps and nine unique residues.

HVR3 amino acids

In HVR3, five of 52 residues (Fig. 5, residues 224–277) are conserved among all strains. Throughout HVR3, sequences from the upper cluster of four A-strains are identical, including an alignment gap. However, the AwAna sequence has 22 unique residues (in green) and is partially conserved with BwNo (nine residues in orange). In striking contrast to differences in HVR1 and HVR2, the AwCobU4-2 and U5-2 homologs have identical HVR3 sequences that are conserved with the B-strains, particularly BwStr (residues in blue), differing only at residues 241 and 244.

Nucleotide sequence alignment confirms a mosaic wspB and identifies a conserved repeated sequence

Nucleotide sequence alignment of eleven wspB homologs confirmed that WOL-A/B genetic mosaicism is concentrated in the HVR regions and revealed three copies of a repeated sequence element within or near HVR2. Further analyses identified three copies of the repeated sequence element in ribA at the 5′-end of the virB8-D4 operon and four copies in vir genes.

HVR1

HVR1 (Fig. S2, nucleotides 117–241) from BwStr begins with two nucleotides (117 and 120 in red) that are conserved in BwStr and all WOL-A-strains except AwCobU5-2 and AwCobU4-2. Downstream, the BwStr sequence includes 47 of 48 nucleotides (in blue) within a sequence motif characteristic of BwStr and the other B-strains. The AwCobU5-2 and AwAna sequences are initially similar to the WOL-B motif, but beginning at an alignment gap in the other A-strains they have 11 nucleotides (in orange, nucleotides 152–207) that are conserved with BwNo and BwPip at positions in which those strains diverge from the WOL-B consensus. Thus, HVR1 in BwStr begins with nucleotides from a conserved WOL-A sequence motif but transitions to the conserved WOL-B motif, while HVR1 from the AwCobU4-2 A-strain differs from that WOL-B motif at a single nucleotide (176). In contrast, the AwAna and AwCobU5-2 sequences are mosaics of the WOL-A and WOL-B consensus motifs and share nucleotides with the divergent BwNo and BwPip B-strains, which also closely resemble each other upstream of HVR1 (23 nucleotides in light blue and one in orange).

HVR2 contains conserved repeat elements

HVR2 (Fig. S2, nucleotides 361–450) contains a conserved WOL-B sequence motif that differs at 20 nucleotides (in blue), from the WOL-A motif, while the divergent sequences from BwNo, BwPip, AwAna and AwCobU5-2 share an alignment gap and are again similar (nucleotides in orange). A tandem repeated sequence at nucleotides 365–379, CAAGTAATCAAGTAAC, in the B-strains BwStr, BwVitB and BwMet occurs with slight variation (underlined residues) as CAAGTAGCCAAATAAC, in the A-strains AwAtab 3, AwKue, AwMel and AwRi. We designated the eight-bp sequence, CAARTARY, where R = A or G, and Y = C or T, as an HVR2-repeat. The pseudogene from AwCobU4-2 contained a third copy of CAAGTAAT that interrupted ORF1 and was removed from the alignment (indicated by upwards arrow below alignment) to shift to ORF3, which maintains identity to the deduced amino acid sequence from BwStr. Just downstream of HVR2 at nucleotides 457–463, a truncated copy of the HVR2-repeat lacking the 3′-terminal pyrimidine is conserved in BwStr, BwVitB, BwMet and AwCobU4-2 and corresponds to the position (indicated by greater than less than symbols below alignment) of the transposon insertion in BwPip. Finally, we noted that the most divergent HVR2 sequences from AwAna, AwCobU5-2, BwNo and BwPip have T/C and A/G substitutions (in orange, light blue and green) that disrupt the HVR2-repeat consensus.

HVR3

Within HVR3 (Fig. S2, nucleotides 670–831), conserved sequence motifs occur in the upper cluster of four A-strains and in the B-strains (nucleotides in blue), with the exceptions of BwPip (HVR3 absent) and BwNo. Sequences from AwCobU4-2 and AwCobU5-2 are identical despite their major differences in HVR1 and HVR2 and differ from the B-strain consensus only at nucleotides 722 and 773 (in orange). The AwAna and BwNo sequences are the most divergent but share 43 variable nucleotides (in orange) and have 67 and 18 unique residues (in green), respectively.

HVR2-repeats also occur in ribA and ribB

Based on a DNA pattern search (http://bioinformatics.org/sms/), three HVR2-repeats occur in ribA, two in virD4, and single copies in virB8 and virB9 (Table 3). In addition, a reverse complement of the CAARTARY sequence occurs at the same position in ribB from three WOL-A-strains and BwPip (see gray shading in Fig. S3). The BwPip homolog contains a second copy at residues 7–14 just downstream of the start codon (not shown) and is a WOL-A/B mosaic (see below). Although repeat frequencies in individual ribA (0.29) and wspB (0.34) genes are ~sixfold higher than in the whole genomes of AwMel and BwPip (0.05) from flies (Diptera), it will be important to re-evaluate these frequencies when a BwStr genome (Hemipteran host) becomes available.

Table 3.

Distribution of HVR2-repeats in B wStr virB8-D4 operon and genomes of A wMel and B wPip

| Repeat | ribA | virB8 | virB9 | virD4 | wspB | wMel | wPip |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAAGTAAT/C | 118/145 | – | – | −5943b | 7610/7618 | 154 | 239 |

| CAAATAAT/C | 672 | – | −2485 | −5919b | – | 275 | 360 |

| CAAGTAGC | – | 1288 | – | – | 7702b | 187 | 104 |

| Total | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 616 | 703 |

| Frequencya | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

Values indicate 5′-nucleotide positions of HRV2-repeats in the 9133-bp ribA to topA sequence from B wStr (see Fig. 1; Acc. KF43064.1). Negative values indicate reverse complement positions. Copy numbers in the complete A wMel (NC_002978.6) and B wPip (NC_010981.1) genomes are shown at right

aFrequency is defined as number repeats/total nucleotides in each individual gene (or complete genome) indicated at the top of the panel, ×100

bSee underlined nucleotides 457–463 in Fig. S2, which lack the 3′-terminal pyrimidine

Although RibA and RibB are involved in riboflavin biosynthesis, ribB is not contiguous with ribA and the virV8-D4 operon, and it has higher variability than ribA (Table 2). Among the WOL-B-strains, ribB in BwStr and BwNo is conserved with the AwAu and AwMel A-strains (Fig. S3; note especially the bold blue residues downstream of nucleotide 181, as well as additional residues in orange). In contrast, the BwPip homolog is best-conserved (nucleotides in red) with WOL-A-strains, AwAna, AwHa and AwRi, including an alignment gap at residue 483 encompassing an identical 15-nucleotide “island” with the reverse complement CAARTARY repeat. Downstream of the gap, at residue 511, the BwPip sequence shifts to a predominantly WOL-B motif conserved in BwStr, BwNo, but also in AwMel (nucleotides in blue), while AwAna, AwRi and AwHa are mutually conserved (nucleotides in orange) versus all other strains. Within the 3′-end of the alignment (nucleotides 541–600), the BwPip sequence is conserved with BwStr, BwNo and DwBm (nucleotides in blue), while AwAu and AwMel are the most divergent (nucleotides in green).

Discussion

Although the status of Wolbachia as a species remains unclear (Baldo et al. 2006b; Lo et al. 2007), a notable distinction between WOL-C-/D-strains that associate with nematodes as mutualists and WOL-A-/B-strains that occur as reproductive parasites in insects relates to genome stability and phylogenetic congruence between Wolbachia and its host. In insect hosts, Wolbachia appears to engage in frequent horizontal gene transfer, resulting in a lack of phylogenetic congruence manifested by gene structures that represent mosaic recombinations from genomes now considered distinct strains. Coinfections with two or more Wolbachia strains and activities of bacteriophages that reside in genomes of WOL-A/B-strains likely contribute to this genetic plasticity (Bordenstein and Reznikoff 2005; Newton and Bordenstein 2011), which may reflect what some authors suggest is a worldwide Wolbachia pandemic (Zug et al. 2012). Examples of natural coinfections include AwAlbA and BwAlbB in A. albopictus mosquitoes (O’Neill et al. 1997), AwVitA and BwVitB in the parasitoid wasp, N.vitripennis (Perrot-Minnot et al. 1996; Raychoudhury et al. 2008) and AwHa and BwNo in the phytophagous D. simulans (James et al. 2002). A particularly interesting example in C. obstrictus weevils involves infection with a single AwCob strain, in which polymorphisms in wspA and wspB indicate that three distinct variants coexist in all host populations (Floate et al. 2011) and it will be of interest to explore other genetic similarities and differences among these variants following separation in vitro and/or in uninfected hosts. Wolbachia coinfections have also been documented in insects such as fig wasps (Yang et al. 2012), tephritid flies (Morrow et al. 2014) and planthoppers (Zhang et al. 2013) whose interactions with parasitoids, parasites and predator arthropods may facilitate horizontal transmission (Cordaux et al. 2001; Werren et al. 2008; Zug et al. 2012). In nature, the BwStr strain occurs in two planthopper hosts (Noda et al. 2001a) and in the strepsipteran endoparasite Elenchus japonicus (Noda et al. 2001b; Zhang et al. 2013). In the present study, BwStr has been artificially introduced into a cultured cell line, which has not been achieved with BwPip or nematode-associated strains. Adaptation of BwStr to cell lines (Noda et al. 2002; Fallon et al 2013) will provide an in vitro system for examining mechanisms of genetic exchange if conditions for maintenance of doubly infected cells can be developed through coinfection or somatic cell fusion. We note that high rates of recombination and transposition in Wolbachia (Baldo et al. 2006a; Cordaux et al. 2008) are consistent with expression of an abundant RecA protein (SR 1.05; Table S3, entry 146) as well as 18 transposases and/or proteins with transposase domains in BwStr (Baldridge et al. 2014).

Genetic plasticity of wspB in the virB8-D4 operon

An intact wspB that maps to the 3′-end of the virB8-D4 operon in most WOL-A genomes (Wu et al. 2004) is absent from 17 of 21 WOL-B-strains, including BwVulC and nearly all other isopod-associated strains (Pichon et al. 2009), and is interrupted by a transposon in BwPip (Sanogo et al. 2007). Here, we verify that in BwStr, an intact wspB is co-transcribed with virD4 and is expressed in C/wStr1 cells as an abundant protein at levels similar to those of many housekeeping proteins. The wspB structure closely resembles that of its better-studied wspA paralog, encoding a major surface antigen that has four HVR regions with sequence motifs that have been shuffled by recombination within and between Wolbachia WOL-A- and -B-strains (Baldo et al. 2005, 2010). Likewise, most sequence variation in wspB alleles occurs in the three HVR regions, with distinctive patterns for each region. HVR1 underscores WOL-A/B mosaicism in AwAna and AwCobU5-2, and in addition it shows a high level of identity between AwCobU4-2 and BwStr. Similarity between AwAna and AwCobU5-2 and between BwStr and AwCobU4-2 also occurs in HRV2, while BwNo stands out as distinctive. In BwPip, HVR2 is disrupted by a transposon insertion and we identified an eight-nucleotide HRV2-repeat (CAARTARY) that correlates with transitions between WOL-A-/B-strain motifs and the pseudogene lesions in BwPip and AwCobU4-2. Finally, we noted that high identity of AwCobU5-2, AwCobU4-2 and BwStr is unique to HVR3.

The remarkable similarity of the wspB homologs from BwStr and AwCobU4-2 (>98 % nucleotide identity Fig. S2) is consistent with exchange of an apparently intact gene between members of distinct Wolbachia supergroups by a mechanism that requires further investigation. Intensive analysis of the wspA paralog demonstrates that intragenic recombination breakpoints are concentrated in conserved regions outside of the HVRs (Baldo et al. 2005, 2010). CAARTARY repeats are not present in wspA, and in wspB, they occur only within and directly adjacent to HVR2 at positions that correspond to pseudogene lesions in AwCobU4-2 and in BwPip (due to a transposition event in BwPip; Sanogo et al. 2007). Furthermore, Pichon et al. (2009) suggested that transposition events may explain absence of wspB in the virB8-D4 operons of many WOL-B-strains. In a practical sense, CAARTARY repeats at wspB pseudogene lesions and WOL-A/B sequence motif transitions (Figs. S1, S2, S3) suggest their involvement in genetic exchange. Because transformation of Wolbachia has not yet been achieved, engineering of CAARTARY repeats into vectors used successfully to introduce selectable markers into other members of the Rickettsiales (see Beare et al. 2011) merits investigation.

Potential functions of WspB

Although bacterial outer membrane proteins are important mediators of interactions with host cells and specific function(s) of both WspA and WspB remain to be identified, they may have unique functions as porin proteins in Wolbachia, which lack cell walls. The virB8-D4 operons of Wolbachia and its sister genera, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia, are similarly organized (Gillespie et al. 2010; Hotopp et al. 2006) with 3′- terminal genes encoding major surface proteins that, analogous to wspB, are co-transcribed with the vir genes (Ohashi et al. 2002). In A. marginale, a family of msp2 pseudogenes undergo “combinatorial gene conversion” at the expression site (Brayton et al. 2002) and MSP2 variants change during growth in different host cell types, which likely reflects a response to host immunity mechanisms (Chávez et al. 2012). Similarly, Baldo et al. (2010) proposed that changes in WspA HVR regions play a role in host adaptation and innate immunity interactions, consistent with variation in the higher-order structure of the protein in different hosts (Uday and Puttaraju 2012). HVR sequence changes in the wspB paralog may reflect a similar dynamic. Additional evidence indicates that MSP2 proteins are glycosylated (Sarkar et al. 2008), which is now an established process in post-translational modification in bacteria (Dell et al. 2010; Nothaft and Szymanski 2010), and we note that WspB contains potential glycosylation sites. Although an inactivated pseudogene or absence of wspB in virB8-D4 operons of some Wolbachia strains indicates that it is not absolutely required for survival, a secretome analysis of Brugia malayi showed that WspB from DwBm is excreted/secreted into filarial host cells (Bennuru et al. 2009). Furthermore, it co-localizes with the Bm1_46455 host protein in tissues that include embryonic nuclei (Melnikow et al. 2011). WspB is therefore itself a candidate T4SS effector that may play a role in reproductive manipulation of the host. Mosaicism in wspB and its high rate of evolution (Comandatore et al. 2013) may thus reflect genetic changes that optimize adaptation to particular host cells such as those in reproductive tissues and facilitate exploitation of new arthropod niches by Wolbachia.

Genetic plasticity of ribA in the virB8-D4 operon

Aside from wspB at the 3′-end of the T4SS virB8-D4 operon, ribA exhibits genetic plasticity at its 5′-end. In both BwStr and BwVulC, ribA is a two-part mosaic of N-terminal WOL-A and C-terminal WOL-B motifs. In contrast, the internal virB8-D4 genes have typical B-strain identities, and in some strain comparisons, amino acid identities slightly exceed nucleotide identities, which Pichon et al. (2009) attribute to strong selection against non-synonymous codon substitutions. Among the internal virB8-D4 genes, however, Klasson et al. (2009) suggest that in AwRi, an especially variable region in virB10 is likely derived from genetic exchange with a B-strain. We note here that ribA from AwRi closely resembles B-strain homologs within a variable region that immediately precedes the GTP cyclohydrolase domain, where its homolog in BwStr transitions from WOL-A to WOL-B sequence motifs (Fig. S1, positions 387–450).

In contrast to DwBm, in which ribA and virB8 are co-transcribed and bind common transcription factors (Li and Carlow 2012), relative abundance levels suggest that in BwStr, ribA is transcribed independently of the virB8-D4 operon. Some WOL-B-strains, such as BwVulC, lack wspB at the 3′-terminus of the virB8-D4 operon, while our data confirm that in BwStr, wspB is co-transcribed with the vir genes, consistent with similar relative abundances of WspB and the five Vir proteins. In aggregate, these observations suggest that WOL-D and WOL-A-/B-strains may differ in how RibA and WspB expression interfaces with T4SS-mediated transport of effectors in filarial worms and arthropod hosts (Felix et al. 2008; Masui et al. 2000; Rances et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2004), and it will be of interest to explore whether such differences relate to riboflavin provisioning. In filarial nematodes (Li and Carlow 2012; Strubing et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2009) and bedbugs (Hosokawa et al. 2010), evidence suggests that Wolbachia provisions host with riboflavin, the precursor of flavin cofactors that are essential for many cellular redox reactions. In contrast, riboflavin depletion reduces BwStr abundance in C/wStr1 cells, suggesting that BwStr utilizes host riboflavin and does not augment riboflavin levels in mosquito host cells (Fallon et al. 2014).

Potential functions of RibA and RibB

In initial commitment steps in riboflavin biosynthesis, enzymatic activities encoded by the ribA and ribB functional domains use GTP and ribulose-5-phosphate as substrates to catalyze riboflavin biosynthesis, consuming 25 molecules of ATP per molecule of riboflavin (Bacher et al. 2000). We note that in Wolbachia genomes, ribA is the annotated homolog of ribBA in Escherichia coli (Brutinel et al. 2013) and encodes a dihydroxybutanone phosphate synthase domain with putative RibB function near the N-terminus, upstream of a GTP cyclohydrolase II domain with conserved dimerization and active site residues (RibA function). As in E. coli, Wolbachia genomes also encode ribB, but at a distinct chromosomal locus, suggesting that ribA and ribB are not coordinately expressed. In Sinorhizobium meliloti (Rhizobiales; Alphaproteobacteria), knockout mutations of ribBA decreased flavin secretion but did not cause riboflavin auxotrophy or block establishment of symbiosis, suggesting that RibBA may have an undefined role in molecular transport (Yurgel et al. 2014). As is the case with BwStr, RibB is at least threefold more abundant than RibA in the bacterium Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (Knegt et al. 2008). In yeast, RibB has thiol-dependent alternative redox states (McDonagh et al. 2011), partially localizes to the mitochondrial periplasm, and has an unexplained function in oxidative respiration that is independent of riboflavin biosynthesis (Jin et al. 2003). These observations raise the possibility that in Wolbachia, RibA and RibB may have functions other than riboflavin biosynthesis that integrate with pathways involved in cellular oxidative state, such as iron metabolism. Intracellular bacteria are challenged by host-imposed oxidative stress and iron starvation (reviewed by Benjamin et al. 2010) and riboflavin biosynthesis is associated with iron acquisition in bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori (Worst et al. 1998) and Campylobacter jejuni (Crossley et al. 2007). Wolbachia interferes with iron metabolism and sequestration in insects (Brownlie et al. 2009; Kremer et al. 2009) and influences iron-dependent host processes such as heme metabolism, oxidative stress, apoptosis and autophagy (Gill et al. 2014). We note that the periplasmic iron-binding component of a membrane transporter is an abundant protein in BwStr (Table S3, entry 778 and Baldridge et al. 2014).

Electronic supplementary material

Polymerase chain reaction primers and amplification products obtained from the B wStr genes, ribA, ribB, virB8-D4, wspB and topA. (DOCX 108 kb)

Genbank accession numbers for all Wolbachia homologs of ribA, ribB, virB8-D4, wspB and topA, including those from B wStr. N/A: not applicable either because the sequences are not available or were not used in the comparisons reported in the tables and figures. The C wOv genome is not annotated and the numerical values refer to genome coordinates determined by BLAST comparisons to B wStr. (XLSX 177 kb)

Results of univariable and multivariable analyses after log transformation of the outcome, Peptide Count, and predictor, Molecular Weight. This table reports results for the refined search of the MS data sets with inclusion of sequences of cloned B wStr genes reported here and highlighted in yellow within the Table. Results of the original search of the four MS data sets were detailed previously (Baldridge et al. 2014). See tabs at bottom: Sheet 1 reports Mean SR values for all proteins in original and refined models in columns M and R; Univariable model and Multivariable Model (adjusted for functional class and MS Dataset) for results of tests of association. Runs 1, 2, 3 and 4 correspond to MS data sets D, E, F and G, respectively. (XLS 283 kb)

Nucleotide alignment of ribA homologs from B wStr and WOL-A, B- and D-strains at left in red, blue and black font, respectively. Nucleotides encoding the dihydroxybutanone phosphate synthase and GTP cyclohydrolase II domains are indicated above the alignment within greater than less than symbols. Asterisks below alignment indicate universally conserved nucleotides. Unique nucleotides are in green font. Nucleotides conserved in B wStr and a majority of B-strains are in dark blue bold font, while those in dark red bold font are conserved with a majority of A-strains. Nucleotides conserved in two to four strains are in light blue, orange or orange bold font. Nucleotides highlighted in gray and cyan indicate the MS-detected A wMel and B wPip 95% confidence peptides shown in Fig. 1, with amino acids indicated at top. Underlined nucleotides correspond to the CAARTARY repeat. See Tables 2 and S2 for host associations and Genbank Accessions. (DOCX 292 kb)

Nucleotide sequence alignment of wspB homologs from B wStr and WOL-A and B-strains as indicated by red and blue font at left. Nucleotides conserved between B wStr and a majority of A-strains are in red font and residues conserved with a majority of B-strains are in blue font. Asterisks below alignment indicate universally conserved nucleotides and double underlines above the alignment indicate three hypervariable regions (HVRs). Unique nucleotides are in green font and residues conserved between two to four strains are in light blue, orange or bold orange font. The greater than less than symbols below alignment indicate a transposon insertion in the wspB pseudogene of B wPip, which is aligned as three discontinuous sequence blocks corresponding to nucleotides 1334165 - 1334594; 1335958 - 1336167; 1336271 – 1336326 from Accession NC_010981.1. The three CAARTARY repeats are underlined (nucleotides 365–379 and 457–463). Highlighted residues correspond to 95% confidence peptides detected by LC–MS/MS (amino acids indicated at top; lower case indicates additional matched peptides not unique to WspB) that were conserved in most strains (gray), conserved in B-strains (cyan), conserved in B wStr and A wCobU4-2 (yellow), or unique to B wStr (olive). See Tables 2 and S2 for host associations and Genbank Accessions. (DOCX 271 kb)

Nucleotide sequence alignment of ribB homologs from B wStr and WOL-A, B- and D-strains at left in red, blue and black font, respectively. Asterisks below the alignment indicate universally conserved nucleotides. Unique nucleotides are in green font. Nucleotides conserved in B wStr and a majority of B-strains are in dark blue bold font, while those in dark red bold font are conserved with a majority of A-strains. Nucleotides conserved in two to four strains are in light blue, orange or orange bold font. See Tables 2 and S2 for host associations and Genbank Accessions. (DOCX 250 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant AI 081322 from the National Institutes of Health and by the University of Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station, St. Paul, MN.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Alvarez-Martinez CE, Christie PJ. Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:775–808. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00023-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher A, Eberhardt S, Fischer M, Kis K, Richter G. Biosynthesis of vitamin B2 (riboflavin) Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:153–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo L, Lo N, Werren JH. Mosaic nature of the Wolbachia surface protein. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5406–5418. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5406-5418.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo L, Bordenstein S, Werengreen JJ, Werren JH. Widespread recombination throughout Wolbachia genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:437–449. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo L, Dunning Hotopp JC, Jolley KA, Bordenstein SR, Biber SA, Choudhury RR, Hayashi C, Maiden MC, Tettelin H, Werren JH. Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7098–7110. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00731-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo L, Desjardins CA, Russell JA, Stahlhut JK, Werren JH. Accelerated microevolution in an outer membrane protein (OMP) of the intracellular bacteria Wolbachia. BMC Evol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldridge GD, Baldridge AS, Witthuhn BA, Higgins L, Markowski TW, Fallon AM. Proteomic profiling of a robust Wolbachia infection in an Aedes albopictus mosquito cell line. Mol Microbiol. 2014;94:537–556. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beare PA, Sandoz KM, Omsland A, Rockey DD, Heinzen RA. Advances in genetic manipulation of obligate intracellular bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:97. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin JA, Desnoyers G, Morissette A, Salvail H, Massé E. Dealing with oxidative stress and iron starvation in microorganisms: an overview. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;88:264–272. doi: 10.1139/Y10-014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennuru S, Semnani R, Meng Z, Ribeiro JMC, Veenstra TD, Nutman TB. Brugia malayi excreted/secreted proteins at the host/parasite interface: stage-and gender-specific proteomic profiling. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow HR, Petrey DS, Liu J, Przybylski D, Rost B. Predicting transmembrane beta-barrels in proteomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2566–2577. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordenstein SR, Reznikoff WS. Mobile DNA in obligate intracellular bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:688–699. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis K. Wolbachia-based technologies for insect pest population control. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;627:104–113. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78225-6_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayton KA, Palmer GH, Lundgren A, Yi J, Barbet AF. Antigenic variation of Anaplasma marginalemsp2 occurs by combinatorial gene conversion. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:1151–1159. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlie JC, Cass BN, Riegler M, Witsenburg JJ, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, McGraw EA, O’Neill SL. Evidence for metabolic provisioning by a common invertebrate endosymbiont, Wolbachia pipientis, during periods of nutritional stress. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000368. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutinel ED, Dean AM, Gralnick JA. Description of a riboflavin biosynthetic gene variant prevalent in the phylum proteobacteria. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:5479–5486. doi: 10.1128/JB.00651-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez AS, Felsheim RF, Kurtti TJ, Ku PS, Brayton KA, Munderloh UG. Expression patterns of Anaplasma marginale Msp2 variants change in response to growth in cattle, and tick cells versus mammalian cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comandatore F, Sassera D, Montagna M, Kumar S, Darby A, Blaxter M, et al. Phylogenomics and analysis of shared genes suggest a single transition to mutualism in Wolbachia of nematodes. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:1668–1674. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordaux R, Michel-Salzat A, Bouchon D. Wolbachia infection in crustaceans: novel hosts and potential routes for horizontal transmission. J Evol Biol. 2001;14:237–243. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00279.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordaux R, Pichon S, Ling A, Perez P, Delaunay C, Vavre F, Bouchon D, Greve P. Intense transpositional activity of insertion sequences in an ancient endosymbiont. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1889–1895. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley RA, Gaskin DJ, Holmes K, Mulholland F, Wells JM, Kelly DJ, van Vliet AH, Walton NJ. Riboflavin biosynthesis is associated with assimilatory ferric reduction and iron acquisition by Campylobacter jejuni. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7819–7825. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01919-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedeine F, Bandi C, Bouletreau M, Kramer L. Insights into Wolbachia obligatory symbiosis. In: Bourtzis K, Miller TA, editors. Insect symbiosis. Florida: CRC Press; 2003. pp. 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Dell A, Galadari A, Sastre F, Hitchen P. Similarities and differences in the glycosylation mechanisms in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Int J Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/148178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon AM. Cytological properties of an Aedes albopictus mosquito cell line infected with Wolbachia strain wAlbB. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2008;44:154–161. doi: 10.1007/s11626-008-9090-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon AM, Baldridge GD, Higgins LA, Witthuhn BA. Wolbachia from the planthopper Laodelphax striatellus establishes a robust, persistent, streptomycin-resistant infection in clonal mosquito cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2013;49:66–73. doi: 10.1007/s11626-012-9571-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon AM, Baldridge GD, Carroll EM, Kurtz CM. Depletion of host cell riboflavin reduces Wolbachia in cultured mosquito cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2014;50:707–713. doi: 10.1007/s11626-014-9758-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix C, Pichon S, Braquart-Varnier C, Braig H, Chen L, Garrett RA, Martin G, Greve P. Characterization and transcriptional analysis of two gene clusters for type IV secretion machinery in Wolbachia of Armadillidium vulgare. Res Microbiol. 2008;159:481–485. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floate KD, Coghlin PC, Dosdall L. A test using Wolbachia bacteria to identify Eurasian source populations of Cabbage Seed Pod Weevil, Ceutorhynchus obstrictus (Marsham), in North America. Environ Entomol. 2011;40:818–2011. doi: 10.1603/EN10315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill AG, Darby AC, Makepeace BL. Iron necessity: the secret of Wolbachia’s success? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;16:e3224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JJ, Ammerman NC, Dreher-Lesnick SM, Rahman MS, Worley MJ, Setubal JC, Sobral BS, Azad AF. An anomalous type IV secretion system in Rickettsia is evolutionarily conserved. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JJ, Brayton KA, Williams KP, Quevado Diaz MA, Brown WC, Azad AF, Sobral BW. Phylogenomics reveals a diverse Rickettsiales type IV secretion system. Infect Immun. 2010;78:1809–1823. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01384-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenboecker K, Hammerstein P, Schlattmann P, Telschow A, Werren JH. How many species are infected with Wolbachia? A statistical analysis of current data. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;281:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa T, Koga R, Kikuchi Y, Meng X-Y, Fukatsu T. Wolbachia as a bacteriocyte-associated nutritional mutualist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:769–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911476107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotopp JC, Lin M, Madupu R, Crabtree SV, Angiloui SV, et al. Comparative genomics of emerging human ehrlichiosis agents. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AC, Dean MD, McMahon ME, Ballard JW. Dynamics of double and single Wolbachia infections in Drosophila simulans from New Caledonia. Heredity. 2002;88:182–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Barrientos A, Tzagoloff A. Yeast dihydroxybutanone phosphate synthase, an enzyme of the riboflavin biosynthetic pathway, has a second unrelated function in expression of mitochondrial respiration. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14698–14703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300593200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambris Z, Cook PE, Phuc HK, Sinkins SP. Immune activation by life-shortening Wolbachia and reduced filarial competence in mosquitoes. Science. 2009;326:134–136. doi: 10.1126/science.1177531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasson L, Westberg J, Sapountzis P, Naslund K, Lutnaes Y, Darby AC, Veneti Z, Chen L, Braig HR, Garret R, et al. The mosaic structure of the WolbachiawRi strain infecting Drosophila simulans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5725–5730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810753106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knegt FH, Mello LV, Reis FC, Santos MT, Vicentini R, Ferraz LF, Ottoboni LM. ribB and ribBA genes from Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans: expression levels under different growth conditions and phylogenetic analysis. Res Microbiol. 2008;159:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebnik R, Locher KP, Van Gelder P. Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: barrels in a nutshell. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:239–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer N, Voronin D, Charif D, Mavingui P, Mollereau B, Vavre F. Wolbachia interferes with ferritin expression and iron metabolism in insects. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000630. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Carlow CKS. Characterization of transcription factors that regulate the type IV secretion system and riboflavin biosynthesis in Wolbachia of Brugia malayi. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Bao W, Lin M, Niu H, Rikihisa Y. Ehrlichia type IV secretion effector ECH0825 is translocated to mitochondria and curbs ROS and apoptosis by upregulating MnSOD. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1037–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo N, Paraskevopoulos C, Bourtzis K, O’Neill SL, Werren JH, Bordenstein SR, Bandi C. Taxonomic status of the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia pipientis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:654–657. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood S, Voth DE, Brayton KA, Beare PA, Brown WC, Heinzen RA, Broschat SL. Identification of Anaplasma marginale type IV secretion system effector proteins. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui S, Sasaki T, Ishikawa H. Genes for the type IV secretion system in an intracellular symbiont, Wolbachia, a causative agent of various sexual alterations in arthropods. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6529–6531. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.22.6529-6531.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh B, Reguejo R, Fuentes-Almagro CA, Ogueta S, Bárcena JA, Padilla CA. Thiol redox proteomics identifies differential targets of cytosolic and mitochondrial glutaredoxin-2 isoforms in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Reversible S-glutathionylation of DHBP synthase (RIB3) J Proteomics. 2011;74:2487–2497. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikow E, Xu S, Liu J, Li L, Oksov Y, Ghedin E, et al. Interaction of a Wolbachia WSP-like protein with a nuclear-encoded protein of Brugia malayi. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow JL, Frommer M, Shearman DC, Riegler M. Tropical tephritid fruit fly community with high incidence of shared Wolbachia strains as platform for horizontal transmission of endosymbionts. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:3622–3637. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton LG, Bordenstein SR. Correlations between bacterial ecology and mobile DNA. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62:198–208. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9693-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H, Kozjak-Pavlovic V, Rudel T, Rikihisa Y. Anaplasma phagocytophilum Ats-1 is imported into host cell mitochondria and interferes with apoptosis induction. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000774. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H, Koizumi Y, Zhang Q, Deng K. Infection density of Wolbachia and incompatibility level in two planthopper species, Laodelphax striatellus and Sogatella furcifera. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;31:727–737. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H, Miyoshi T, Zhang Q, Watanabe K, Deng K, Hoshizaki S. Wolbachia infection shared among planthoppers (Homoptera: Delphacidae) and their endoparasite (Strepsiptera: Elenchidae): a probable case of interspecies transmission. Mol Ecol. 2001;10:2101–2106. doi: 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H, Myoshi T, Koizumi Y. In vitro cultivation of Wolbachia in insect and mammalian cell lines. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2002;38:423–427. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2002)038<0423:IVCOWI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothaft H, Szymanski CM. Protein glycosylation in bacteria: sweeter than ever. Nat Rev. 2010;8:775–778. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofran Y, Rost B. ISIS: interaction sites identified from sequence. Bioinformatics. 2006;23:e13–e16. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi N, Zhi N, Lin Q, Rikihisa Y. Characterization and transcriptional analysis of gene clusters for a type IV secretion machinery in human granulocytic and monocytic ehrlichiosis agents. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2128–2138. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2128-2138.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill SL, Pettigrew MM, Sinkins SP, Braig HR, Andreadis TG, Tesh RB. In vitro cultivation of Wolbachia pipientis in an Aedes albopictus cell line. Insect Mol Biol. 1997;6:33–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1997.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Zhou G, Wu J, Bian G, Lu P, Raikhel AS, Xi Z. Wolbachia induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent activation of the toll pathway to control dengue virus in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E23–E31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116932108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrot-Minnot MJ, Guo LR, Werren JH. Single and double infections with Wolbachia in the parasitic wasp Nasonia vitripennis: effects on compatibility. Genetics. 1996;143:961–972. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon S, Bouchon D, Cordaux R, Chen L, Garret RA, Greve P. Conservation of the type IV secretion system throughout Wolbachia evolution. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rances E, Voronin D, Tran-Van V, Mavangui P. Genetic and functional characterization of the type IV secretion system in Wolbachia. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5020–5030. doi: 10.1128/JB.00377-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raychoudhury R, Baldo L, Oliveira DCSG, Werren JH. Modes of acquisition of Wolbachia: horizontal transfer, hybrid introgression, and convergence in the Nasonia species complex. Evolution. 2008;63:165–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio R, Hu Y, Aksoy S. Strategies of the home-team: symbioses exploited for vector-borne disease control. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanogo YO, Dobson SL, Bordenstein SR, Novak RJ. Disruption of the Wolbachia surface protein gene wspB by a transposable element in mosquitoes of the Culex pipiens complex (Diptera, Culicidae) Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:143–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saridaki A, Bourtzis K. Wolbachia: more than just a bug in insect genitals. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar M, Troese MJ, Kearns SA, Yang T, Reneer DV, Carlyon JA. Anaplasma phagocytophilum MSP2(P44)-18 predominates and is modified into multiple isoforms in human myeloid cells. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2090–2098. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01594-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]