Introduction

Primary hepatic neoplasms represent only 0.5%–2.0% of all paediatric neoplasms.1 The most common hepatic neoplasm in children is metastasis. Most primary liver tumours in children are malignant, but one-third are benign.2 Mesenchymal hamartoma (MH) of the liver, though rare is the second most frequent benign liver mass in children after infantile haemangioendothelioma and is characterized by cystic hamartomatous mesenchymal proliferation.2 This article discusses the aetiopathogenesis and pathologic features, and describes the role of imaging in the diagnosis and management of this unusual entity.

Case report

A 10 month old male infant patient, an issue of non-consanguineous marriage and born normally at full-term, was brought to hospital with a painless right upper abdominal lump. This lump was noted over the last one month. There was no history of fever, vomiting, jaundice or haematuria. The baby's weight gain and achievement of milestones had been normal. On examination, the baby was active, playful and weighed 9.0 kg. He had a protuberant abdomen. There was hepatomegaly with a span of 13.0 cm. A firm, non-tender mass with a smooth surface was evident arising from the right lobe of the liver. There was no splenomegaly. The liver function tests and enzymes including serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) were normal. All haematological and other biochemical tests were also normal. Test for echinococcal antigen was negative. Ultrasonography (USG) revealed a large well-circumscribed multicystic mass measuring 10.0 cm × 10.0 cm × 11.0 cm in the right lobe of the liver. The cysts measured 2.0 cm–5.0 cm in size. The cyst walls were 2.0 mm–4.5 mm thick with areas of irregularity; however there were no mural nodules or calcific foci. Debris was noted in the dependent part of the larger cysts (Fig. 1). A few small solid areas that were heterogeneously hypoechoic were noted between the cysts. On colour-Doppler flow imaging, there was no evidence of increased vascularity. A subsequent non-contrast and contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed a well-defined multicystic mass measuring 10.0 cm × 11.0 cm × 12.0 cm involving almost the entire right hepatic lobe. The central and peripheral cysts had an attenuation of 4 Hounsfield Units (HU) and 17 HU, respectively. The cyst walls revealed contrast-enhancement. A few small solid areas of enhancement were also noted between the cysts (Fig. 2). The rest of the abdomen was normal. Based on the clinical presentation and imaging findings, a diagnosis of hepatic MH was made. The infant underwent surgical intervention in the form of marsupialization with uneventful post-surgical recovery. Biopsy from the lesion at surgery confirmed the imaging diagnosis.

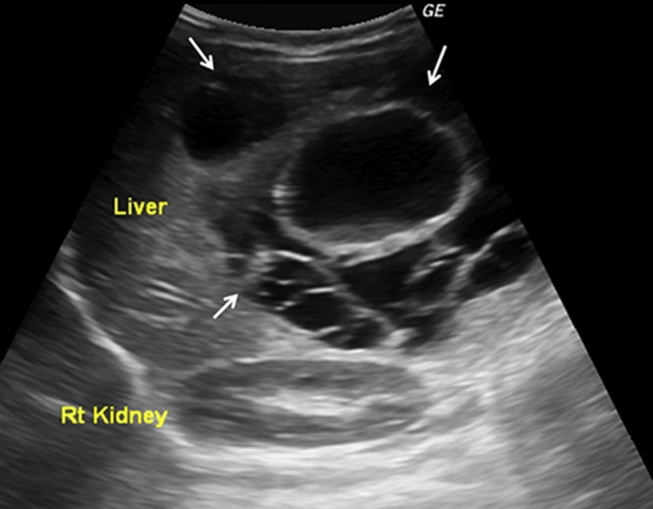

Fig. 1.

Ultrasonographic image showing a large multiloculated cystic hepatic mass (white arrows). Cysts of variable sizes and echogenic debris noted within the large central cyst.

Fig. 2.

Axial and coronal CT images show a large multicystic hepatic lesion. The attenuation of the central cyst is lower than the peripheral cysts. Contrast-enhancement is noted anteriorly and in the septae (white arrows).

Discussion

MH is the second most common benign liver mass in children. A PubMed search revealed about 260 reported cases till 2013.

MH occurs due to uncoordinated proliferation of periportal primitive mesenchymal tissue. It had hitherto been considered a congenital lesion, attributed to factors like ductal plate malformation, bile duct obstruction, ischaemia or degeneration of Ito cells, and lymphatic duct obstruction.2 However, cytogenetics and flow cytometry have revealed balanced translocations at 19q13.4 and aneuploidy that suggest a neoplastic process.1, 2 The mass grows along the portal tracts, compressing the adjacent parenchyma resulting in atrophy, degeneration and subsequent intralesional fluid accumulation. MH shares several histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and cytogenetic features with undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma (UES).2, 3 UES has also been reported in a background of MH.2

MH generally occurs in children less than 2 years of age with a male preponderance (male: female, 2:1). The right lobe of liver is more frequently involved (right: left = 6:1). It has also been reported in foetuses, older children and adults. There is no racial predilection.2, 4 The usual presentation is a large (>10 cm), progressively increasing, painless abdominal mass.5, 6 Others may present with respiratory distress, fever, vomiting, high-output cardiac failure or lower limb oedema.1 Serum AFP and GGT may be elevated.5, 6 AFP levels are higher in patients with solid MH than cystic MH.7 The natural history of MH is to initially enlarge and then stabilize or continue to grow. Some spontaneously regress and calcify.8 Intranatal complications include polyhydramnios, foetal hydrops, abdominal dystocia and foetal demise.9

On gross pathology, MH appears as a large, well-defined, unifocal cystic mass. 85% are multilocular and composed of variable sized cysts containing clear amber fluid or gelatinous material. Others have a mixed solid-cystic or solid appearance2, 5, 6 and these are immature forms of the former.7 Solid lesions tend to occur in younger patients.2 Histologically, MH reveals mesenchymal stellate cell proliferation in a loose mucopolysaccharide-rich matrix and hepatocyte cords surrounding vessels and bile ducts. Mesenchymal collagen fibrils separate to form pseudocysts. The bile ducts constitute the proliferating component and displace the hepatocytes peripherally; however some immature hepatocytes develop as a component of the lesion.2, 7 Necrosis, haemorrhage and calcification are rare.2, 6, 10

The imaging spectrum of MH parallels the gross pathologic appearances. At USG, the cystic areas have thin or thick echogenic septae and debris. The solid portions appear echogenic. Colour-Doppler flow imaging shows minimal vascularity in the solid areas and septae. Areas with very small cysts that appear solid may reveal a sieve-like appearance at high-frequency USG.2, 3 Intraoperative USG may be used to aspirate cysts and reduce the tumoral volume, guide resection and define vascular anatomy.3 On CT, MH appears as a complex cystic mass. The cyst contents are isodense to water, and the stromal elements are hypodense to liver. At magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the appearances depend on the relative predominance of cystic versus stromal elements and the cyst protein content.11 The cystic areas are markedly hyperintense on T2-weighted images and variable in signal intensity on T1-weighted images. The solid areas appear hypointense on both T1-and T2-weighted images due to fibrosis11; however interspersed areas of hyperintensity on T2-weighted images have been observed.10 Mild contrast-enhancement of the septae and stromal components is seen on both CT and MRI; however no capsule is seen.

There are many diagnostic considerations for a hepatic mass in a young child (Table 1). Hepatoblastoma is characterized by a markedly elevated serum AFP, solid appearance and calcification; however, infrequently serum AFP may be low in hepatoblastoma or mildly raised in MH, and MH may appear predominantly solid. Also, histopathologic ambiguity may result due to sampling from the peripheral hepatocyte-rich part of MH. Focal infantile haemangioendothelioma with stromal myxoid change can be distinguished from the hypovascular MH by the enlarged vessels, peripheral nodular enhancement with centripetal fill-in, and calcifications. UES occurs in older children (6–10 years of age) and is distinguished by the frankly malignant stroma and frequent haemorrhage and necrosis.

Table 1.

Common paediatric hepatic masses and their distinguishing features.

| Serial number | Lesion/Mass | Age at presentation | Sex | AFP levels | Characteristic imaging features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Infantile haemangioendothelioma | <6 months | M:F = 1:1.4–2 | Normal or mildly elevated |

|

| 2 | Mesenchymal hamartoma | <2 years | M:F = 2:1 | Normal or mildly elevated |

|

| 3 | Hepatoblastoma | <3 years | M:F = 2:1 | Markedly elevated |

|

| 4 | Undifferentiated embryonic sarcoma | 6–10 years | M:F = 1:1 | Normal |

|

| 5 | Hepatic cyst (congenital or acquired) | – | – | Normal |

|

| 6 | Intrahepatic choledochal cyst (Todani type 4a) | – | M:F = 1:3–4 | Normal |

|

| 7 | Echinococcal cyst type II (cyst with daughter cysts and matrix) | – | – | Normal |

|

| 8 | Pyogenic abscess | – | – | Normal |

|

| 9 | Haematoma | – | – | Normal |

|

| 10 | Biloma | – | – | Normal |

|

For predominantly cystic MH, differential considerations include simple cyst, hydatid disease, and abscess if the mass is intrahepatic and choledochal cyst, enteric duplication cyst, and mesenteric lymphangioma if the mass is pedunculated. Simple cysts do not show any internal enhancement. The collagen-rich pericyst of hydatid cyst is hypointense on all MR sequences and its enhancement is restricted to the periphery. In type II hydatid cysts (cyst with daughter cysts and matrix), the attenuation of the central mother cyst is higher than that of daughter cysts on CT.12 Moreover it takes several years for a hydatid cyst to reach the average size of a cystic MH, hence an unlikely diagnosis in infants. Abscesses would be associated with fever and other signs of sepsis. Choledochal cyst is located at the porta hepatis and its communication with the biliary tree may be demonstrable on cholangiography or scintigraphy. The walls of enteric duplication cysts demonstrate ‘gut signature’ and peristalsis on ultrasonography.

The treatment of MH is surgical. The four surgical options available are enucleation, marsupialization of cysts, excision of hamartoma and formal hepatic lobectomy. The procedure chosen must be individualized. Orthotopic liver transplantation has also been reported.2 Adequate resection is curative and long-term follow-up is satisfactory.1

Conclusion

Hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma is a rare, benign, congenital paediatric tumour. It usually presents as a large painless right upper quadrant mass and on imaging reveals a multicystic appearance. Due to its rarity, incompletely understood aetiopathogenesis, relationship with undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma and the wide spectrum of imaging appearances, it may simulate a variety of benign and malignant lesions and often presents a diagnostic dilemma. Radiology not only has a vital role in suggesting the diagnosis but also in the surgical management.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Pandey A., Gangopadhyay A.N., Sharma S.P. Long-term follow-up of mesenchymal hamartoma of liver – single centre study. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:20–22. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.74449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung E.M., Cube R., Lewis R.B., Conran R.M. From the archives of the AFIP. Pediatric liver masses: radiologic-pathologic correlation Part 1. Benign tumors. Radiographics. 2010;30:801–826. doi: 10.1148/rg.303095173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakheja D., Margraf L.R., Tomlinson G.E., Schneider N.R. Hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma with translocation involving chromosome band 19q13.4: a recurrent abnormality. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;153:60–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stocker J.T., Ishak K.G. Mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver: report of 30 cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Pathol. 1983;1:245–267. doi: 10.3109/15513818309040663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anil G., Fortier M., Low Y. Cystic hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma: the role of radiology in diagnosis and perioperative management. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:e91–e94. doi: 10.1259/bjr/41579091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim S.H., Kim W.S., Cheon J. Radiological spectrum of hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma in children. Korean J Radiol. 2007;8:498–505. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2007.8.6.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang H.J., Jin S.Y., Park C. Mesenchymal hamartomas of the liver: comparison of clinicopathologic features between cystic and solid forms. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:63–68. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narsimhan K.L., Radotra B.D., Harish J., Rao K.L.N. Conservative management of giant mesenchymal hamartoma. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kodandapani S., Pai M.V., Kumar V., Pai K.V. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital mesenchymal hamartoma of liver: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/932583. 932583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye B., Hu B., Wang L. Mesenchymal hamartoma of liver: magnetic resonance imaging and histopathologic correlation. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5807–5810. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i37.5807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horton K.M., Bluemke D.A., Hruban R.H., Soyer P., Fishman E.K. CT and MR imaging of benign hepatic and biliary tumours. Radiographics. 1999;19:431–451. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.2.g99mr04431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polat P., Kantarci M., Alper F., Suma S., Koruyucu M.B., Okur A. Hydatid disease from head to toe. Radiographics. 2003;23:475–494. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]