Both phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation may allow widely distributed plant species to either acclimate or adapt to environmental heterogeneity. Given the typically low genetic variation of clonal plants across their habitats, phenotypic plasticity may be the primary adaptive strategy allowing them to thrive across a wide range of habitats. In this study, we used field investigation and controlled experiments to test this. We found that plasticity in water use efficiency (reflected by foliar δ13C) is more important than local adaptation in allowing the studied clonal plants to occupy a wide range of habitats.

Keywords: δ13C, ecotype, genetic differentiation, Leymus chinensis, phenotypic plasticity, species distribution, water use efficiency

Abstract

Both phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation may allow widely distributed plant species to either acclimate or adapt to environmental heterogeneity. Given the typically low genetic variation of clonal plants across their habitats, phenotypic plasticity may be the primary adaptive strategy allowing them to thrive across a wide range of habitats. In this study, the mechanism supporting the widespread distribution of the clonal plant Leymus chinensis was determined, i.e. phenotypic plasticity or local specialization in water use efficiency (WUE; reflected by foliar δ13C). To test whether plasticity is required for the species to thrive in different habitats, samples were collected across its distribution in the Mongolian steppe, and a controlled watering experiment was conducted with two populations at two different sites. Five populations were also transplanted from different sites into a control environment, and the foliar δ13C was compared between the control and original habitats, to test for local specialization in WUE. Results demonstrated decreased foliar δ13C with increasing precipitation during controlled watering experiments, with divergent responses between the two populations assessed. Change in foliar δ13C (−3.69 ‰) due to water addition was comparable to fluctuations of foliar δ13C observed in situ (−4.83 ‰). Foliar δ13C differed by −0.91 ‰ between two transplanted populations; however, this difference was not apparent between the two populations when growing in their original habitats. Findings provide evidence that local adaptation affects foliar δ13C much less than phenotypic plasticity. Thus, plasticity in WUE is more important than local adaptation in allowing the clonal plant L. chinensis to occupy a wide range of habitats in the Mongolian steppe.

Introduction

A major question in ecology and evolution is why plants are distributed across a wide range of environmental conditions. Phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation are two complementary mechanisms that allow plants to adjust to environmental heterogeneity. Phenotypic plasticity is the ability of a single genotype to produce different phenotypes in response to environmental variation (Bradshaw 1965; Sultan 1987; Lortie and Aarssen 1996; Murren et al. 2015). Several empirical studies have suggested that species can adapt to diverse habitats via phenotypic plasticity (Sultan 2001; Ayrinhac et al. 2004; Hulme 2008). However, the capacity of individual genotypes to perform well across all habitats is often limited (DeWitt et al. 1998). Geographic variation can lead to the evolution of different adaptations to the local environment, and thus generate ecotypic differentiation in important functional traits (Kawecki and Ebert 2004; Savolainen et al. 2007). Therefore, widespread plant species are often characterized by both phenotypic plasticity and local specialization to particular environmental conditions (Van Tienderen 1990; Joshi et al. 2001), though the relative contribution of these strategies to their distributions may be species specific.

Leymus chinensis is a perennial rhizomatous clonal C3 grass, widely distributed across eastern areas of the Eurasian steppe (Liu et al. 2007; Chen and Wang 2009; Wang et al. 2011). The species has a very broad distribution in China as a dominant or co-dominant plant (Liu et al. 2007). As an economically and ecologically important grass species, the question as to why L. chinensis can thrive across such a large range of arid and semi-arid regions has received considerable attention in recent years. For example, several studies have assessed the impacts of large-scale climatic variables on responses ranging from variation in population density, plant height, leaf size, biomass and biomass allocation to anatomical and physiological plasticity (Wang and Gao 2003; Wang et al. 2003, 2011). However, the relative importance of plasticity and local adaptation in water use efficiency (WUE) to support the persistence of L. chinensis across variable environments has not been extensively studied. As water is typically the most limiting factor for growth and community productivity across a plant's distribution (Huxman et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2005), selecting an indicator related to WUE can help to better understand whether, and to what extent, phenotypic plasticity versus local adaptation influences the distribution of a species thriving in arid and semi-arid regions. Foliar δ13C is an important indicator of plant long-term WUE (Farquhar et al. 1982; Ehleringer 1993; Saurer et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2013) and, therefore, can be used to assess water adaptation strategies of L. chinensis across its distribution.

In this study, we determined whether plasticity or local specialization in WUE (reflected by foliar δ13C) supports the widespread distribution of the clonal plant L. chinensis. Given the typically low genetic variation of clonal plants across their habitats, phenotypic plasticity may be the most important adaptive strategy allowing them to thrive (Parker et al. 2003; Geng et al. 2007; Riis et al. 2010). However, Chen and Wang (2009) reported that two ecotypes of L. chinensis occur across its distribution, with divergent anatomies and physiologies. Therefore, local specialization in WUE of this clonal plant may also be apparent across its distribution. We hypothesized that both plasticity and local specialization in WUE contribute to the widespread distribution of this clonal species, and that plasticity is the primary adaptive mechanism. If so, foliar δ13C of this clonal plant would be rapidly changed in response to changes in habitat water conditions, potentially to the extent of variations in foliar δ13C apparent across its entire distribution. Additionally, local specialization in foliar δ13C would also be apparent among populations dominating different habitats.

Methods

Response of L. chinensis foliar δ13C to natural environments in the Mongolian steppe

In order to investigate natural variations in L. chinensis foliar δ13C, a large-scale field study in the Mongolian steppe was conducted; half of the study region was located in Mongolia and half in Inner Mongolia, China. The study area extended ∼15° longitude, from 106.4° to 121.7° longitude, and 6° latitude, from 43.72° to 49.43° latitude. The climate was predominantly arid and semi-arid continental, and mean annual precipitation (MAP) ranged from ∼190 to 400 mm. The main vegetation types distributed from west to east across the study area were desert steppe, typical steppe and meadow steppe.

Mature leaves of L. chinensis were collected from 24 sites across west to east Mongolia in 2008, and 18 sites across west to east Inner Mongolia in 2011 [see Supporting Information—Table S1]. The majority of sampling sites were located far from cities and were considered to be under natural conditions, without significant human influence. In order to adequately sample environmental heterogeneity and avoid biased sampling of, for example, one specific microhabitat, the topography of each site was assessed, and samples collected systematically from lower to higher elevations along the hillside aspect at each site. The sampling area at each site was 50 m2 (1 × 50 m). In the 2008 field campaign, samples were collected across the 50-m2 sampling area and pooled at each site, resulting in one sample for each site assessed. In the 2011 field campaign, five samples were systematically collected from five 1 × 1 m plots, extending in 10-m intervals from a low to high position along the hillside aspect at each site, resulting in five samples per site assessed in 2011. For each sample, all mature leaves (except withered leaves) of five to eight randomly chosen L. chinensis individuals were collected and pooled for later analyses.

Plasticity in L. chinensis foliar δ13C in two controlled watering experiments

In order to assess changes in L. chinensis foliar δ13C due to precipitation, two controlled watering experiments were conducted at two sites in Inner Mongolia in 2011: a desert steppe site MDLT and a typical steppe site ABGQ [see Supporting Information—Table S1]. These experiments formed part of a larger experiment for other purposes (see Liu et al. 2014). At each site, 18 plots (1 × 1 m) were established, and 6 levels of supplementary watering (0, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 % of local MAP [MDLT, ∼215 mm; ABGQ, ∼263 mm]) were assigned to triplicate plots. The total amount of water per treatment level was divided into five equal parts, and evenly applied five times during the growing season, from 18 June to 7 August. During each watering event, water was applied evenly to each plot using a portable 1-m2 plot boundary, constructed of mild steel, and a watering can, used as a simple rainfall simulator. Some soil was piled up around the metal frame to minimize any leakage from the plot. In late August 2011, after one season of watering, mature L. chinensis leaves (except withered leaves) were collected from both sites for subsequent analyses.

Variation among different L. chinensis populations in a transplant experiment

In order to assess potential adaptive variations in foliar δ13C among different populations of L. chinensis originating from various locations, four populations of L. chinensis were transplanted to a field station, and the foliar δ13C compared with plants from the source populations. In 2009, we chose four sites from west to east Inner Mongolia: MDLT, XLHT, XWQ and HH [see Supporting Information—Table S1]. Leymus chinensis ramets were collected from each site and transplanted to a field experimental site located at the Maodeng Grassland Ecology Research Station (MDMC), in central Inner Mongolia. Twelve plots (2 × 2 m) were established, though only three were used in this study; the remainder were used for the study of Liu et al. (2013). Ten L. chinensis ramets were transplanted into each plot and were watered until the end of the growing season (late September 2009) to ensure survival. Transplants were not watered during 2010, and in late September 2010, all mature leaves (except withered leaves) of the transplanted ramets were collected across plots, and pooled to make one sample for each plots. Individual ramets of local L. chinensis populations were also randomly selected for mature leaf collection, resulting in the overall collection of samples from five L. chinensis populations. In order to investigate variations in foliar δ13C among these five populations under natural conditions, comparative sampling was also performed in their respective original collection sites in 2011.

Carbon isotope measurement

All leaves were immediately microwaved (500 W, 2 min) after collection to ensure deactivation of plant enzymes, and subsequently air-dried. Once back in the laboratory, samples were further dried in a drying oven at 65 °C for 48 h. All collected plant material was ground to a homogenous powder using a ball mill (MM200; Retsch, Haan, Germany).

Aliquots of ∼2.5 mg of plant material were weighed into tin capsules for foliar δ13C measurement. For samples collected during the transplant experiment, foliar δ13C was measured using continuous-flow gas isotope ratio mass spectrometry (CF-IRMS) with Vario PYRO Cube (IsoPrime100; Isoprime Ltd, Stockport, UK) at the Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development in Agriculture, CAAS, China. Reproducibility was high, with the standard deviation of repeated measurements <0.20 ‰. For all other samples assessed in this study, foliar δ13C was measured using CF-IRMS with Flash EA1112 and the interface Conflo III (MAT 253; Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) at the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China. Reproducibility was high, with the standard deviation of repeated measurements <0.15 ‰. Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite was used as the reference standard for carbon isotopic analyses.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R v.3.1.3 (R Development Core Team 2015). For both in situ investigations and controlled watering experiments, the correlation between foliar δ13C and precipitation was examined using linear regression. This correlation reflects the plasticity of foliar δ13C to changes in precipitation. To test for local specialization in foliar δ13C plasticity between the two populations of the controlled watering experiment, differences between the regression slopes of the two populations were tested using the smatr package (Warton et al. 2012). For the transplantation experiment, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences between L. chinensis populations originating from various locations. Tukey's honest significant differences (Tukey's HSD) analysis was used to examine significant differences highlighted by ANOVAs. One-way ANOVA was also used to test for differences between respective transplanted (data from 2010) and field (data from 2011) populations.

Results

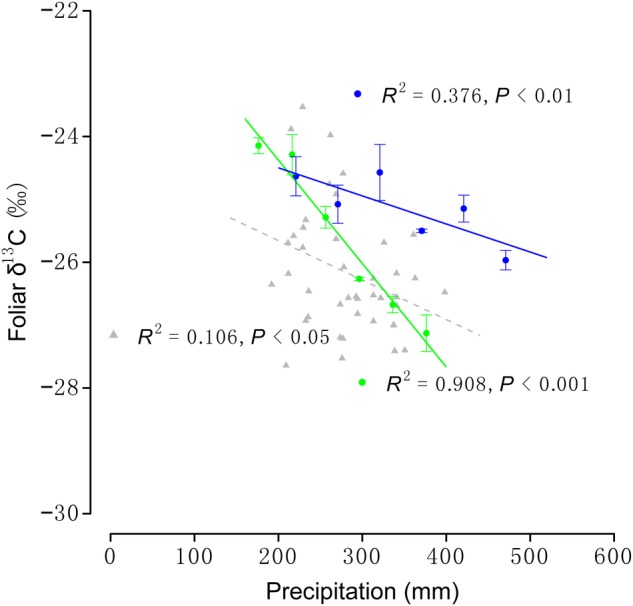

In the field investigation, L. chinensis foliar δ13C decreased with increasing precipitation across its distribution (Fig. 1; F1,40 = 4.755, R2 = 0.106, P < 0.05). Comparable responses were observed for L. chinensis populations at MDLT (F1,16 = 158.3, R2 = 0.908, P < 0.001) and ABGQ (Fig. 1; F1,16 = 9.655, R2 = 0.376, P < 0.01). Data obtained from transects in the Mongolian steppe showed a range in L. chinensis foliar δ13C of −4.83 ‰, from −27.92 to −23.09 ‰. Water addition induced change in foliar δ13C values of −3.69 ‰, from −27.43 to −23.74 ‰, for the two populations examined during the controlled watering experiments. Significant differences between the two population's responses to water treatments were observed (Fig. 1; χ2 = 13.32, df = 1, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

The response of L. chinensis foliar δ13C to precipitation during field investigations and controlled watering experiments. Grey triangles and dashed line represent field investigation data. Circles and solid lines represent data from the controlled watering experiment conducted in MDLT (green) and ABGQ (blue). Each point represents mean (±SE) foliar δ13C (n = 5).

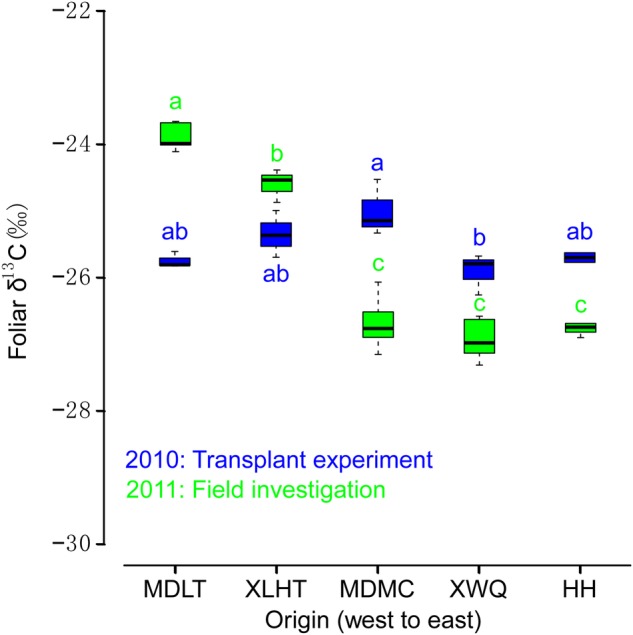

In the transplant experiment, a significant difference in L. chinensis foliar δ13C was observed in relation to original collection site (F4,9 = 4.230, P < 0.05), i.e. there was local specialization in foliar δ13C among populations (Fig. 2). However, Tukey's HSD analysis revealed that statistically significant differences were apparent only between populations originating from MDMC and XWQ, the former exhibiting significantly higher foliar δ13C; no other significant differences were apparent between populations (Fig. 2). Mean foliar δ13C differed by −0.91 ‰ between MDMC and XWQ populations. In the field investigation, significant differences in foliar δ13C were observed for the five populations assessed in 2011 (F4,27 = 142.4, P < 0.001). Tukey's HSD analysis showed that the MDLT population exhibited higher foliar δ13C than the XLHT population, which exhibited higher foliar δ13C than all others. Significant differences in foliar δ13C were also observed between field collected and transplanted specimens, for each of the five populations (MDLT: F1,6 = 194.6, P < 0.001; XLHT: F1,6 = 16.46, P < 0.01; MDMC: F1,13 = 57.65, P < 0.01; XWQ: F1,6 = 19.23, P < 0.01 and HH: F1,5 = 33.27, P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Foliar δ13C values of five L. chinensis populations from different geographical regions assessed during the 2010 transplant experiment (blue) and 2011 field investigation (green). Box plots show median (solid line) values. Lowercase letters indicate homogeneous subsets identified by ANOVA and Tukey's HSD analyses (P < 0.05).

Discussion

It has recently been suggested that phenotypic plasticity may be the primary adaptive strategy for clonal plant species surviving in a wide range of habitats (Parker et al. 2003; Riis et al. 2010). Our experimental evidence suggests that this may indeed be the case for L. chinensis. Based on foliar δ13C, we have provided evidence of local specialization in L. chinensis WUE; however, WUE plasticity was more important to allow this clonal plant to occupy a wide range of habitats in the Mongolian steppe.

Plasticity in L. chinensis WUE could allow the clonal plant to thrive in the majority of habitats across its distribution. Our study demonstrated that foliar δ13C values of L. chinensis decreased with increasing precipitation, both in the field investigation and controlled watering experiments (Fig. 1). It means that the clonal plant L. chinensis favours higher WUE in drier environment. This negative relationship between plant foliar δ13C and precipitation is consistent with the findings of several previous studies (Diefendorf et al. 2010; Prentice et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2015), and indicated that this clonal plant has the ability to respond to changing water conditions by altering its WUE (i.e. plasticity). The study area investigated during the present study covered the majority of L. chinensis' distribution in the Mongolian steppe, and we can, therefore, assume that the range of foliar δ13C determined by our field investigation (−4.83 ‰) is representative of the natural variation in foliar δ13C apparent in situ. During the controlled watering experiment, precipitation was applied at two sites, and we can assume that changes in foliar δ13C were solely due to the plasticity of each population at each site. The change in foliar δ13C observed during the controlled watering experiment (−3.69 ‰) was lower than, but comparable to, variation in foliar δ13C observed across different field conditions in the Mongolian steppe; the difference between these two values was −1.14 ‰. Given these data, we can conclude that WUE plasticity allows L. chinensis to thrive across most habitats, though there are some differences in foliar δ13C of the clonal plant that cannot be explained by plasticity.

Based on the coefficient of determination (i.e. R2), the strength of the relationship between L. chinensis foliar δ13C and precipitation was shown to be weaker in the field investigation than during the controlled watering experiments (Fig. 1). This indicated that other factors might affect the relationship between foliar δ13C and precipitation across the in situ distribution of L. chinensis. One likely explanation is the contribution of genetic variation to differences in foliar δ13C (Kohorn et al. 1994; Lauteri et al. 2004; Corcuera et al. 2010), although other environmental parameters, such as temperature, light, CO2 and altitude, can also affect the foliar δ13C of plants (Körner et al. 1988; Tazoe et al. 2011; Cernusak et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2015). During the controlled water experiments of the present study, differential plasticity in foliar δ13C responses to precipitation was demonstrated for the two L. chinensis populations growing in their native habitats. Whereas differences in plasticity could be caused by other environmental parameters, and thus our results do not conclusively demonstrate differential specialization in WUE between these two populations, the results of our transplant experiment confirm that this is the case.

Given that several studies have indicated that local adaptation allows plants to successfully occupy different habitats (Ramirez-Valiente et al. 2010; Grassein et al. 2014; Si et al. 2014), local adaptation could also contribute to the wide distribution of the clonal plant L. chinensis. During our transplant experiment, different populations of L. chinensis were transplanted into the same environment to identify whether variations in foliar δ13C across different populations were caused by local adaptation. In this study, significant differences in foliar δ13C were observed between different populations grown for 2 years in the same habitat (Fig. 2). The mean foliar δ13C difference between MDMC and XWQ populations was −0.91 ‰, highly comparable to the unaccountable fluctuation in foliar δ13C (−1.14 ‰) observed under natural conditions in situ. This suggests that variations in WUE observed during the field investigation in the Mongolian steppe may also partially be accounted for by local adaptation. However, our data highlight that the contribution of local adaptation is small relative to plasticity (Fig. 2). In 2011, we investigated the foliar δ13C of the same five populations growing in their original collection habitats. Comparison of foliar δ13C between each transplanted and in situ population revealed a significant difference between the two growth conditions for all populations (Fig. 2). No significant differences in foliar δ13C were observed between MDMC and XWQ populations in situ, whereas significant variations were apparent after 2 years of growth under transplant conditions (Fig. 2). We also identified significant differences between MDLT, XLHT and HH in situ populations, whereas these populations demonstrated no difference during transplant experiments (Fig. 2). Taken together, these findings indicated that plasticity might be more important than local adaptation in affecting L. chinensis WUE across its distribution.

Conclusions

In summary, plasticity causes a greater divergence in L. chinensis foliar δ13C than local adaptation, although local specialization in foliar δ13C exists. Thus, WUE plasticity might be more important than local adaptation in allowing the clonal plant L. chinensis to occupy a wide range of habitats in the Mongolian steppe. In order to make a stronger inference that phenotypic plasticity is more important than local adaptation to allow the clonal plant widely distribute in the steppe, more studies focussing on other functional traits or plant fitness are needed in the future.

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (40871032 and 41071209) and the Bureau of Science and Technology for Resources and Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences (KZCX2-EW-QN604). Y.L. was funded by a scholarship from the China Scholarship Council.

Contributions by the Authors

All authors together conceived and designed the experiment. Y.L. and L.Z. performed the experiment. Y.L. analysed the data. Y.L. and H.N. wrote the manuscript with comments and help from the other authors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

Supporting Information

The following additional information is available in the online version of this article –

Table S1. Characteristics of all sites used in this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful and detailed suggestions, which helped us to improve the manuscript. We thank the Maodeng Grassland Ecology Research Station for providing the experimental field site and accommodation.

Literature Cited

- Ayrinhac A, Debat V, Gibert P, Kister AG, Legout H, Moreteau B, Vergilino R, David JR. 2004. Cold adaptation in geographical populations of Drosophila melanogaster: phenotypic plasticity is more important than genetic variability. Functional Ecology 18:700–706. 10.1111/j.0269-8463.2004.00904.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw AD. 1965. Evolutionary significance of phenotypic plasticity in plants. Advances in Genetics 13:115–155. 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60048-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Ubierna N, Winter K, Holtum JAM, Marshall JD, Farquhar GD. 2013. Environmental and physiological determinants of carbon isotope discrimination in terrestrial plants. New Phytologist 200:950–965. 10.1111/nph.12423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wang R. 2009. Anatomical and physiological divergences and compensatory effects in two Leymus chinensis (Poaceae) ecotypes in Northeast China. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 134:46–52. 10.1016/j.agee.2009.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Bai Y, Lin G, Han X. 2005. Variations in life-form composition and foliar carbon isotope discrimination among eight plant communities under different soil moisture conditions in the Xilin River Basin, Inner Mongolia, China. Ecological Research 20:167–176. 10.1007/s11284-004-0026-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corcuera L, Gil-Pelegrin E, Notivol E. 2010. Phenotypic plasticity in Pinus pinaster δ13C: environment modulates genetic variation. Annals of Forest Science 67:812P1–812P11. 10.1051/forest/2010048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dewitt TJ, Sih A, Willson DS. 1998. Costs and limits of phenotypic plasticity. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 13:77–81. 10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01274-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefendorf AF, Mueller KE, Wing SL, Koch PL, Freeman KH. 2010. Global patterns in leaf 13C discrimination and implications for studies of past and future climate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 107:5738–5743. 10.1073/pnas.0910513107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR. 1993. Variation in leaf carbon isotope discrimination in Encelia farinosa: implications for growth, competition, and drought survival. Oecologia 95:340–346. 10.1007/BF00320986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, O'leary MH, Berry JA. 1982. On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 9:121–137. 10.1071/PP9820121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y, Pan X, Xu C, Zhang W, Li B, Chen J, Lu B, Song Z. 2007. Phenotypic plasticity rather than locally adapted ecotypes allows the invasive alligator weed to colonize a wide range of habitats. Biological Invasions 9:245–256. 10.1007/s10530-006-9029-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grassein F, Lavorel S, Till-Bottraud I. 2014. The importance of biotic interactions and local adaptation for plant response to environmental changes: field evidence along an elevational gradient. Global Change Biology 20:1452–1460. 10.1111/gcb.12445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme PE. 2008. Phenotypic plasticity and plant invasions: is it all Jack? Functional Ecology 22:3–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01369.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huxman TE, Smith MD, Fay PA, Knapp AK, Shaw MR, Loik ME, Smith SD, Tissue DT, Zak JC, Weltzin JF, Pockman WT, Sala OE, Haddad BM, Harte J, Koch GW, Schwinning S, Small EE, Williams DG. 2004. Convergence across biomes to a common rain-use efficiency. Nature 429:651–654. 10.1038/nature02561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi J, Schmid B, Caldeira MC, Dimitrakopoulos PG, Good J, Harris R, Hector A, Huss-Danell K, Jumpponen A, Minns A, Mulder CPH, Pereira JS, Prinz A, Scherer-Lorenzen M, Siamantziouras ASD, Terry AC, Troumbis AY, Lawton JH. 2001. Local adaptation enhances performance of common plant species. Ecology Letters 4:536–544. 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00262.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawecki TJ, Ebert D. 2004. Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters 7:1225–1241. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohorn LU, Goldstein G, Rundel PW. 1994. Morphological and isotopic indicators of growth environment: variability in δ13C in Simmondsia chinensis, a dioecious desert shrub. Journal of Experimental Botany 45:1817–1822. 10.1093/jxb/45.12.1817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Körner C, Farquhar GD, Roksandic Z. 1988. A global survey of carbon isotope discrimination in plants from high altitude. Oecologia 74:623–632. 10.1007/BF00380063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauteri M, Pliura A, Monteverdi MC, Brugnoli E, Villani F, Eriksson G. 2004. Genetic variation in carbon isotope discrimination in six European populations of Castanea sativa Mill. originating from contrasting localities. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 17:1286–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Niu H, Xu X. 2013. Foliar δ13C response patterns along a moisture gradient arising from genetic variation and phenotypic plasticity in grassland species of Inner Mongolia. Ecology and Evolution 3:262–267. 10.1002/ece3.453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang L, Niu H, Sun Y, Xu X. 2014. Habitat-specific differences in plasticity of foliar δ13C in temperate steppe grasses. Ecology and Evolution 4:648–655. 10.1002/ece3.970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Li Y, Zhang L, Xu X, Niu H. 2015. Effects of sampling method on foliar δ13C of Leymus chinensis at different scales. Ecology and Evolution 5:1068–1075. 10.1002/ece3.1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Li X, Li H, Yang Q, Liu G. 2007. The genetic diversity of perennial Leymus chinensis originating from China. Grass and Forage Science 62:27–34. 10.1111/j.1365-2494.2007.00558.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lortie CJ, Aarssen LW. 1996. The specialization hypothesis for phenotypic plasticity in plants. International Journal of Plant Sciences 157:484–487. 10.1086/297365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murren CJ, Auld JR, Callahan H, Ghalambor CK, Handelsman CA, Heskel MA, Kingsolver JG, Maclean HJ, Masel J, Maughan H, Pfennig DW, Relyea RA, Seiter S, Snell-Rood E, Steiner UK, Schlichting CD. 2015. Constraints on the evolution of phenotypic plasticity: limits and costs of phenotype and plasticity. Heredity 115:293–301. 10.1038/hdy.2015.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker IM, Rodriguez J, Loik ME. 2003. An evolutionary approach to understanding the biology of invasions: local adaptation and general-purpose genotypes in the weed Verbascum thapsus. Conservation Biology 17:59–72. 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.02019.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice IC, Meng TT, Wang H, Harrison SP, Ni J, Wang GH. 2011. Evidence of a universal scaling relationship for leaf CO2 drawdown along an aridity gradient. New Phytologist 190:169–180. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valiente JA, Sanchez-Gomez D, Aranda I, Valladares F. 2010. Phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation in leaf ecophysiological traits of 13 contrasting cork oak populations under different water availabilities. Tree Physiology 30:618–627. 10.1093/treephys/tpq013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. 2015. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; http://www.Rproject.org/ (22 March 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Riis T, Lambertini C, Olesen B, Clayton JS, Brix H, Sorrell BK. 2010. Invasion strategies in clonal aquatic plants: are phenotypic differences caused by phenotypic plasticity or local adaptation? Annals of Botany 106:813–822. 10.1093/aob/mcq176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurer M, Siegwolf RTW, Schweingruber FH. 2004. Carbon isotope discrimination indicates improving water-use efficiency of trees in northern Eurasia over the last 100 years. Global Change Biology 10:2109–2120. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00869.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen O, Pyhäjärvi T, Knürr T. 2007. Gene flow and local adaptation in trees. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 38:595–619. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Si C, Dai Z, Lin Y, Qi S, Huang P, Miao S, Du D. 2014. Local adaptation and phenotypic plasticity both occurred in Wedelia trilobata invasion across a tropical island. Biological Invasions 16:2323–2337. 10.1007/s10530-014-0667-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan SE. 1987. Evolutionary implications of phenotypic plasticity in plants. Evolutionary Biology 21:127–178. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan SE. 2001. Phenotypic plasticity for fitness components in Polygonum species of contrasting ecological breadth. Ecology 82:328–343. 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0328:PPFFCI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, Von Caemmerer S, Estavillo GM, Evans JR. 2011. Using tunable diode laser spectroscopy to measure carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion dynamically at different CO2 concentrations. Plant, Cell and Environment 34:580–591. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02264.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tienderen PH. 1990. Morphological variation in Plantago lanceolata: limits of plasticity. Evolutionary Trends in Plants 4:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Xu SS, Jia X, Gao J, Zhang WP, Qiu YP, Wang GX. 2013. Variations in foliar stable carbon isotopes among functional groups and along environmental gradients in China—a meta-analysis. Plant Biology 15:144–151. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00605.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Gao Q. 2003. Climate-driven changes in shoot density and shoot biomass in Leymus chinensis (Poaceae) on the North-east China Transect (NECT). Global Ecology and Biogeography 12:249–259. 10.1046/j.1466-822X.2003.00027.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Gao Q, Chen Q. 2003. Effects of climatic change on biomass and biomass allocation in Leymus chinensis (Poaceae) along the North-east China Transect (NECT). Journal of Arid Environments 54:653–665. 10.1006/jare.2002.1087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Huang W, Chen L, Ma L, Guo C, Liu X. 2011. Anatomical and physiological plasticity in Leymus chinensis (Poaceae) along large-scale longitudinal gradient in northeast China. PLoS ONE 6:e26209 10.1371/journal.pone.0026209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warton DI, Duursma RA, Falster DS, Taskinen S. 2012. smatr 3—an R package for estimation and inference about allometric lines. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 3:257–259. 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00153.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.