Abstract

Purpose of review

Despite tremendous promise as a female-controlled HIV prevention strategy, implementation of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women has been limited, in part because of disparate efficacy results from randomized trials in this population. This review synthesizes existing evidence regarding PrEP efficacy for preventing HIV infection in women and considerations for delivering PrEP to women.

Recent findings

In three efficacy trials, conducted among men and women, tenofovir-based oral PrEP reduced HIV acquisition in subgroups of women by 49–79% in intent-to-treat analyses, and by >85% when accounting for PrEP adherence. Two trials did not demonstrate an HIV prevention benefit from PrEP in women, but substantial evidence indicates those results were compromised by very low adherence to the study medication. Qualitative research has identified risk perception, stigma, and aspects of clinical trial participation as influencing adherence to study medication. Pharmacokinetic studies provide supporting evidence that PrEP offers HIV protection in women who are adherent to the medication.

Summary

Tenofovir-based daily oral PrEP prevents HIV acquisition in women. Offering PrEP as an HIV prevention option for women at high risk of HIV acquisition is a public health imperative and opportunities to evaluate implementation strategies for PrEP for women are needed.

Keywords: HIV prevention, pre-exposure prophylaxis, women, efficacy, effectiveness, adherence

Introduction

HIV/AIDS is the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age, and a combination of biological, behavioral, and sociocultural factors result in women bearing a disproportionate burden of the global HIV epidemic [1, 2]. HIV prevention strategies available to women at risk of sexual transmission include abstinence from sexual activity, female and male condoms, and antiretroviral therapy (ART) use or voluntary male medical circumcision by their partners; however, all of these strategies depend on male partner cooperation. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)-based pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a novel prevention strategy in which HIV uninfected individuals use an oral antiretroviral medication as chemoprophlaxis to reduce HIV acquisition [3]. PrEP holds tremendous promise as a female-controlled prevention approach, and international normative bodies recommend PrEP for persons at substantial HIV risk, including women [4–8]. However, the delivery of PrEP to women at high risk of HIV is underdeveloped due to complicated results from clinical trials that assessed PrEP efficacy among women. In addition, cost, policies, infrastructure, and limited availability of antiretroviral medications are logistical factors limiting the scale-up of PrEP in areas of high HIV burden. In order to maximize the impact of PrEP, it is important to understand the different PrEP efficacy results across trials, draw a definitive conclusion about the HIV prevention benefit of PrEP for women, and identify elements from clinical trials and open-label studies that are important to address within programs delivering PrEP to women.

Text of Review

Randomized Clinical Trials of PrEP among Women

Five double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials of daily oral TDF-based PrEP that included heterosexual women were conducted [9–15] (Table 1). All trials were carried out in settings with high HIV burden and study subjects received a comprehensive package of HIV prevention services including frequent HIV testing, risk reduction and adherence counselling, condoms, and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STI). Participants received intensive adherence counselling to take study drug once per day, and multiple methods were used to measure adherence, including self-report, daily diaries, clinic-based counts of returned pills and bottles, and testing archived blood samples for tenofovir. Despite similarities in study design and analytic approach, the primary intent-to-treat efficacy results varied substantially across trial populations.

Table 1.

Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Randomized Trials that Included HIV Uninfected Heterosexual Women to Assess the Efficacy of Daily Oral Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF)-Based Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Prevention

| Study Characteristics | Benefit of PrEP (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Study Population | Sample Size | Oral PrEP Agent | Plasma TDF in a Random Sample of Participants | Overall Efficacy | Female Subgroup Efficacy | Additional Analyses among Women |

| Partners PrEP Study Baeten et al. (9, 14, 15) |

Heterosexual HIV-1 uninfected persons in HIV-1 serodiscordant relationships: Kenya, Uganda | 4,747 serodiscordant couples (including 1,785 in which the HIV uninfected partner was female) | TDF-FTC | 81% | 75% (55, 87%) | 66% (28, 84%) | Tenofovir > 40 ng/mL: 94% (−17, 100%) Age < 30 years: 72% (25, 90%) Partner viral load > 50,000 copies/mL: 72% (13, 91%) |

| TDF | 83% | 67% (44, 81%) | 71% (37, 87%) | Tenofovir > 40 ng/mL: 85% (−90, 99%) Age < 30 years: 77% (29, 92%) Partner viral load > 50,000 copies/mL: 84% (29, 96%) |

|||

| TDF2 Thigpen et al. (11) |

Heterosexual men and women: Botswana | 1,219 (557 women) | TDF-FTC | 79% | 62% (22, 83%) | 49% (−22, 81%) | With censoring after self-reported discontinuation of study medication: 75% (24, 94%) |

| Bangkok Tenofovir Study Choopanya et al. (13) |

Male and female injection drug users: Thailand | 2,413 (489 women) | TDF | 67% | 49% (10, 72%) | 79% (17, 97%) | |

| FEM-PrEP Van Damme et al. (12) |

Heterosexual women: Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa | 2,120 women | TDF-FTC | 24% | 6% (−52, 41%) | NA | |

| VOICE Marrazzo et al. (10) |

Heterosexual women: South Africa, Uganda, Zimbabwe | 3,019 women (an additional 2,010 women were assigned to tenofovir gel) | TDF-FTC | 29% | −4% (−49, 27%) | NA | |

| TDF | 30% | −49% (−129, 3%) | NA | ||||

Three of the five studies found that daily oral PrEP reduced the risk of HIV acquisition overall and in subgroup analyses of women. In the Partners PrEP Study, which included 1,785 Kenyan and Ugandan women with a mutually disclosed HIV-infected partner, PrEP efficacy among women was 66% and 71% for the two PrEP medications tested, and PrEP efficacy did not differ substantially between men and women [9]. In further analyses, the protective effect of PrEP was consistent in subgroups of women at high risk for HIV acquisition [10]. PrEP efficacy among women in the TDF2 study in Botswana was 49%, although the small sample size limited statistical precision [12]. Although women comprised only 20% of participants in the Bangkok Tenofovir Study (BTS), PrEP efficacy among this subgroup was 79% [13]. In contrast, two trials among African women, (FEM-PrEP, conducted among 2,120 women from Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa and VOICE, conducted among 3,019 women from South Africa, Zimbabwe and Uganda), demonstrated no effect of daily oral PrEP on HIV acquisition [14, 15].

Data from all five trials consistently demonstrated that HIV acquisition occurred during periods of low or no adherence to PrEP. Having tenofovir detected in blood samples was associated with ≥85% protection from PrEP [11] and the frequency of tenofovir detection in each overall trial population strongly paralleled the HIV protection observed in each study. In the three trials that demonstrated a protective effect from PrEP, tenofovir was detected in 67–83% of samples from a random subset of participants [9, 12, 13], compared to 24–30% in the two trials with null results [14–16], leading to the conclusion that PrEP protects women from HIV infection when it is used.

Biological Factors Influencing PrEP Efficacy among Women

A number of biological factors have been hypothesized to influence the protective effect of PrEP in women. Foremost among these is the presence of adequate PrEP medication at the time of HIV exposure. Preventing HIV acquisition through sexual contact likely depends on sufficient adherence to achieve tenofovir levels in genital (or rectal) tissues that can prevent viral replication and dissemination. Men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women, for whom rectal exposure carries the greatest HIV risk, appear to benefit from near-complete HIV protection with blood levels reflecting as few as four doses of TDF-based PrEP per week [17]. MSM who used an event-driven, coitally-dependent PrEP regimen achieved high rectal concentrations of tenofovir and reduced HIV acquisition by 86% [18]. The body of evidence to define the level of tenofovir and number of doses required to confer this level to women is limited, particularly studies linking pharmacokinetics to in vivo pharmacodynamics. Available data suggest that more consistent dosing is required to achieve sufficient levels of tenofovir in vaginal tissue than rectal tissues [14, 19–21]; however, as demonstrated in the efficacy clinical trials of PrEP, women who were generally adherent to a daily PrEP regimen were strongly protected against HIV.

Additional hypotheses have questioned whether the benefits of PrEP may be compromised in younger women who are more susceptible to HIV because of immature genital mucosa, in women with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), in women who encounter a high viral inoculum (i.e., due to high viral concentrations or acute HIV infection in partners), and due to interactions with hormonal contraceptives [14, 22–24]. Physiological features, including a higher proportion of exposed cervico-vaginal epithelium tissues, and increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in genital secretions and inflammatory immune cells in cervicovaginal fluid, may put younger women at higher risk of HIV acquisition [25]. On average, HIV-uninfected participants in the Partners PrEP Study, TDF2, and BTS were older than women in FEM-PrEP and VOICE [9, 14, 15]; however, the protective effect of tenofovir-based PrEP was 72–77% in a subgroup analysis of women <30 years old in the Partners PrEP Study [10]. The baseline prevalence of bacterial STIs was lower in the Partners PrEP Study, as compared to VOICE and FEM-PrEP [14, 15, 26], and differences in recurrent and undiagnosed STIs or vaginal washing and drying, may have heightened women’s susceptibility to HIV [27]. However, in the Partners PrEP Study the protective effect of PrEP was 67–71% in a subgroup analysis of couples diagnosed with an STI in the past three months, and 83% of all HIV-uninfected women in the study reported daily vaginal washing [10, 26].

HIV incidence among women in the Partners PrEP placebo arm was 2.8 per 100 person years, substantially lower than incidence rates seen in FEM-PrEP (5.0 per 100 person years) and VOICE (4.2–4.6 per 100 person years) [9, 14, 15]. One proposed explanation for this difference is that women in the Partners PrEP Study were primarily exposed to HIV by chronically infected men, who were potentially less infectious than acutely infected men [27]. While infectivity is a strong predictor of HIV transmission, the majority of infections in generalized HIV epidemics are transmitted from persons with chronic HIV [28, 29], and thus it is likely that the majority of transmissions in FEM-PrEP and VOICE were as well. The overall protective effect of PrEP was 76–78% among all HIV uninfected participants and 72–84% among women whose partner had a viral load ≥50,000 copies/mL in the Partners PrEP Study, providing evidence that the prevention benefit of PrEP was not attenuated with exposure to high HIV viral load [10]. Animal models have demonstrated that the protective effect of TDF-based PrEP does not diminish over time, regardless of the number of challenges, suggesting that there may not be a threshold effect of PrEP when taken with sufficient adherence [30, 31].

The high pregnancy incidence rate among women initiating oral contraceptives during FEM-PrEP initially suggested a potential interaction between oral contraceptives and PrEP [32, 33]. However, low adherence to oral contraceptives, especially among new users, is thought to be the driving factor behind this pregnancy incidence and women who adopted oral contraceptives at study enrollment were also less likely to adhere to study drug [16, 34]. TDF-based PrEP does not interact with oral, injectable or implantable contraception to reduce either the effectiveness of contraceptives to prevent unintended pregnancy nor the HIV prevention benefit of PrEP [33, 35]. Indeed, PrEP is one strategy that could mitigate concern regarding the potential increased risk for HIV acquisition among women using progestin-based injectable contraception [36].

Behavioral Factors Influencing PrEP Effectiveness among Women

Although challenging to accurately measure, motivation to prevent HIV acquisition is likely tied to self-perceived risk, which in turn influences adherence to HIV prevention strategies [37]. Despite inclusion criteria based on objective measures of HIV risk and the high observed HIV incidence among placebo arm participants [38], 50% of women enrolled in FEM-PrEP thought they had “no chance” of acquiring HIV in the next 12 weeks and seroconverters described underestimating their risk and rationalizing their risk behavior(s) [14, 37, 39]. Adherence was highest among older participants in BTS, VOICE, and the Partners PrEP Study [15, 40, 41]; younger participants in VOICE and FEM-PrEP were likely less experienced navigating personal risk and this may have influenced their HIV prevention decision-making [24]. In qualitative interviews, VOICE participants acknowledged that their trial participation was motivated by increased HIV risk from male partners with additional sexual partners, however women often had to compromise study drug adherence and keep their trial participation covert to maintain these relationships [42].

Across trials, personal assessment of high HIV risk, coupled with social and clinic-based support, facilitated greater self-efficacy to adhere to daily oral PrEP. HIV uninfected participants in the Partners PrEP Study had known exposure to HIV from their mutually-disclosed HIV infected study partner and both partners received adherence counselling during the trial [39]. PrEP provided a solution to the “discordance dilemma” by simultaneously preventing HIV acquisition and maintaining the partnership, especially prior to ART initiation by the HIV infected partner [43]. Low or no adherence to PrEP in the Partners PrEP Study was associated with no or infrequent sex with a study partner, suggesting that participants modified their PrEP use based on fluctuations in their sexual activity and perceived HIV risk [11, 41]. Participants in the BTS were self-identified injection drug users attending drug treatment centers who had potential for parenteral and sexual exposure and 93% of participants elected to attend daily study visits [40]. Although participants did receive compensation for each study visit, these characteristics also suggest a high motivation for risk reduction.

Despite PrEP being a discrete female-controlled prevention method, community-level stigma related to HIV infection impacted women’s adherence to study drug [44, 45]. Women in VOICE described the importance of taking their study drugs secretly in order to preserve their healthy, HIV uninfected image [45]. Women perceived stigma associated with HIV and encountered suspicion from community members about why an HIV uninfected person would take antiretrovirals [45]. Men expressed concerns about possible undisclosed HIV positive status and additional sexual partners when their female partners used PrEP. Some male partners felt threatened by women’s participation in research and exercising autonomy to access health care [42, 44, 46]. It was taxing for women to manage social relationships while participating in the VOICE study; these challenges contributed to women concealing study participation and missing PrEP doses [45, 47].

Features of clinical trials also influenced the behaviors of trial participants. Overall study retention in FEM-PrEP and VOICE was 82–91%, and quality clinical care, education, and modest financial reimbursement in settings with limited opportunity for income generation, motivated women to maintain their participation [9, 12–15, 42, 47–49]. However, retrospectively, participants in FEM-PrEP and VOICE expressed ambivalence about research and the importance of adhering to study medication, including reluctance to use investigational drugs with the potential for side effects and unknown levels of HIV protection [15, 42, 49]. Inaccurate self-reported adherence was common in the trials. Participants in FEM-PrEP cited perceived consequences, such as trial termination, negative reactions from study staff, and additional time needed to explain their non-adherence during study visits, as reasons for over-reporting adherence [42, 49]. Some VOICE participants believed that tenofovir testing would rectify inaccurate self-reported adherence, and poor adherence by some women could be overcome by high adherence from others [42].

The HIV Prevention Benefit of PrEP Requires Adherence

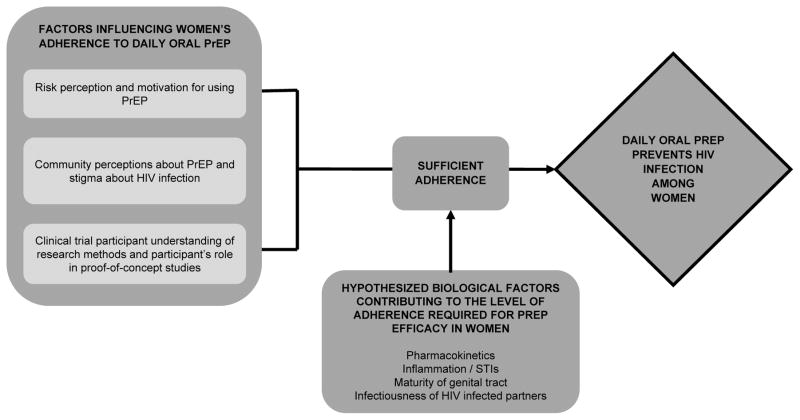

The conflicting results across trials regarding the benefit of PrEP for women have challenged the HIV prevention community. However, when analyzed collectively, there is a clear conclusion that daily oral TDF-based PrEP is protective for women, established through subgroup analyses, consistency across studies when adherence is evaluated, and bolstered by analogous data from men. Like any medication, adherence is required for PrEP to be efficacious. Pharmacokinetic studies suggest that consistent adherence is required to achieve sufficient concentrations of tenofovir in vaginal tissues and a substantial proportion of women across studies attained this level of high adherence. The lack of a protective effect observed in FEM-PrEP and VOICE can be attributed to overall low adherence to study medication and is not due to biological features unique to women [50, 51]. While adherence challenges observed across all trials have important implications for PrEP delivery to women, they should not detract from the overall conclusion that PrEP protects women from HIV acquisition when taken with sufficient adherence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic depicting the totality of evidence for tenofovir-based oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV among women

Delivering PrEP to Women

The next steps for PrEP delivery to women include implementation within routine healthcare, in the context of a now-proven protective benefit from PrEP and without the incentives of clinical trials. Clinical trial data suggest that PrEP is tolerant of some missed doses, and additional research is needed to understand how many doses can be missed and still provide HIV protection for women, as well as whether that differs in the presence of cofactors influencing HIV susceptibility.

Integrating Time-Limited PrEP into Existing Reproductive Health Services

Integrating HIV risk assessment and PrEP dispensation into established sexual and reproductive health services that women access routinely, including HIV/STI testing and counselling, antenatal care, and contraceptive counselling is a natural strategy to maximize the impact of PrEP [24]. Delivery strategies for time-limited PrEP use during periods when a woman’s HIV risk is greatest – including new partnerships with men of unknown HIV status, with HIV infected male partners prior to ART initiation, during pregnancy and pregnancy attempts when condom use is reduced - are feasible, safe, and cost-effective [52–59]. Providers can use risk scoring tools to identify women with the highest risk for HIV acquisition using routinely collected clinical and demographic data [60, 61].

Facilitating Adherence in Public Health Settings

Individuals’ adherence patterns changed relatively little during the clinical trials: in general, those who initiated PrEP maintained their adherence, especially if they adhered through the end of the first month [11, 15]. Greater public health impact may come from prioritizing PrEP for those who will achieve this sustained high adherence, directing adherence support to the subset with adherence challenges, and assisting women to assess their risk and match PrEP use with their most vulnerable periods [58]. PrEP delivery to women must be coupled with realistic expectations of and mechanisms to facilitate adequate adherence, including personal risk assessment and social support [24, 62–64]. Community sensitization regarding antiretroviral medications for prevention, not just treatment, of HIV may create a context that is more receptive to PrEP use. When it is safe for a woman to share her desire for HIV prevention, her invitation to a male partner to participate in decision-making about PrEP may facilitate her high adherence.

Initial data suggest that adherence to and HIV protection from PrEP is higher in open label-studies when the HIV prevention benefit is well understood by users. Among MSM enrolled in the PROUD study, high self-reported adherence to daily oral TDF-based PrEP was substantiated by blood tenofovir levels and provided 86% protection from HIV [65]. Among HIV serodiscordant couples enrolled in the Partners Demonstration Project using PrEP as a “bridge” until the HIV infected partner sustains ART use, tenofovir was detected in 86% of samples tested and contributed to an estimated 96% reduction in HIV [66, 67].

Open-label studies also suggest that adherence to daily dosing may be preferred over intermittent or event-driven dosing, perhaps because it fits into daily routines and does not require anticipating sex [68, 69]. In ADAPT (HPTN 067), an open-label study of oral PrEP dosing frequency among young South African women, adherence was assessed through Wisepill monitoring. Women randomized to a daily dosing schedule had higher adherence overall and 75% of sexual acts covered by PrEP, as compared to 52–56% of sex acts among women randomized to less than daily or intermittent dosing to align with sexual activity [68]. Long-acting formulations of PrEP delivered as injectables or vaginal rings, including multi-purpose technologies that provide dual protection against HIV and unintended pregnancy, are currently being evaluated and may provide alternative strategies to daily oral PrEP in the future [70–73]. Analogous to contraception, for which multiple methods permit choices to accommodate individual women’s needs, multiple delivery mechanisms for PrEP may allow more women to achieve HIV protection [74].

Conclusion

Tenofovir-based oral PrEP is an effective HIV prevention strategy for heterosexual women. Significant public health impact from PrEP will require delivery strategies that integrate PrEP into existing health services and address the individual, community, and structural level factors that influence adherence. More than thirty years into the HIV epidemic, oral PrEP is the first intervention that women can control themselves and it offers highly efficacious prevention against HIV.

Key Points.

Clinical trial data demonstrate that daily tenofovir-based oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) prevents HIV acquisition among women when taken with sufficient adherence.

Pharmacokinetic studies provide evidence that daily dosing of tenofovir-based oral PrEP reaches concentrations in vaginal tissues that are consistent with levels needed for HIV prevention.

Evidence from clinical trials and emerging data from open-label studies demonstrate that women who are at risk of HIV and motivated to use PrEP can adhere sufficiently to the daily regimen and be protected against HIV.

Innovative strategies to motivate women at risk to use daily PrEP and scalable adherence support strategies need to be identified and integrated into delivery models.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the dedication of the thousands of men and women who have participated in the PrEP clinical trials and open-label demonstration projects.

Footnotes

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Kerry A. Thomson, Email: thomsonk@uw.edu.

Jared M. Baeten, Email: jbaeten@uw.edu.

Nelly R. Mugo, Email: rwamba@csrtkenya.org.

Linda-Gail Bekker, Email: Linda-Gail.Bekker@hiv-research.org.za.

Connie L. Celum, Email: ccelum@uw.edu.

Renee Heffron, Email: rheffron@uw.edu.

References

- 1.Adimora AA, Ramirez C, Auerbach JD, et al. Preventing HIV infection in women. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;63:S168–S173. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318298a166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramjee G, Daniels B. Women and HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Research and Therapy. 2013;10 doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeten JM, Haberer JE, Liu AY, Sista N. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: Where have we been and where are we going? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;63:S122–S129. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182986f69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *4.United States Public Health Service. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States: 2014 Clinical Practice Guideline. 2014 These guidelines recommend daily oral PrEP as TDF/FTC for heterosexual women who are at substantial risk of HIV acquisition, including during the periconception and pregnancy periods. [Google Scholar]

- *5.United States Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Treatment of Hiv-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1- Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. 2014 These guidelines state that PrEP is not contraindicated during pregnancy and is a recommended strategy for HIV uninfected women who are at high risk of HIV acquisition before and during pregnancy, including PrEP as a safer conception strategy for HIV serodiscordant couples. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Guidance on pre-exposure oral prophylaxis (PrEP) for serodiscordant couples, men and transgender women who have sex with men at high risk of HIV: Recommendations for use in the context of demonstration projects. Geneva: 2012. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidance_prep/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marrazzo JM, Del Rio C, Holtgrave DR, et al. HIV prevention in clinical care settings: 2014 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312:390–409. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DK, Thigpen MC, Nesheim SR, et al. Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of hiv infection in heterosexually active adults. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61:586–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **10.Murnane PM, Celum C, Mugo N, et al. Efficacy of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among high-risk heterosexuals: subgroup analyses from a randomized trial. AIDS. 2013;27:2155–2160. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283629037. This study presents robust estimates of daily oral PrEP efficacy among subgroups of HIV uninfected women enrolled in the Partners PrEP Study that facilitate comparison to female study populations enrolled in other PrEP efficacy trials. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **11.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, et al. HIV Protective Efficacy and Correlates of Tenofovir Blood Concentrations in a Clinical Trial of PrEP for HIV Prevention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;66:340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000172. This paper presents estimates of TDF-based oral PrEP efficacy within subgroups of the Partners PrEP Study defined by plasma tenofovir levels. High adherence to TDF-based PrEP provided high protection (>88%) from HIV among both men and women, and patterns of adherence were consistent throughout follow-up. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:2083–2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **15.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. This article presents the primary intent-to-treat analysis from the VOICE double-blind placebo controlled randomized clinical trial of tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among young African women. Specifically, the study did not demonstrate that daily oral PrEP prevents HIV acquisition, however adherence to daily study medication was very low (<30%) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **16.Corneli AL, Deese J, Wang M, et al. FEM-PrEP: Adherence patterns and factors associated with adherence to a daily oral study product for pre-exposure prophylaxis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;66:324–331. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000158. In this subcohort analysis from 3 FEM-PrEP trial sites, oral TDF-based PrEP concentrations, as measured by plasma tenofovir levels, were 28.5% at all visits. Only 12% of participants achieved good adherence throughout the study and adherence was lower among women initiating oral contractive pills at the time of trial enrollment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *17.Grant RM, Anderson PL, Mcmahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014;14:820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. Uptake of daily oral TDF-based PrEP was high among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women enrolled in the open-label iPrEX study. Adherence was higher during periods of increased HIV risk, and taking four or more daily doses per week provided near complete protection from HIV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *18.Molina J-M. How Would You Like Your PrEP?: Updates on PrEP efficacy in Ipergay IAS 2015. 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis Treatment and Prevention; Vancouver, Canada. 2015; Men who have sex with men enrolled in the open-label Ipergay study achieved high rectal concentrations of TDF-based PrEP and reduced HIV acquisition by 86% with an event-driven, coitally-dependent dosing schedule. [Google Scholar]

- **19.Cottrell ML, Srinivas N, Kashuba AD. Pharmacokinetics of antiretrovirals in mucosal tissue. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2015;11:893–905. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2015.1027682. This article presents a comprehensive of review of antiretroviral pharmacokinetics, including evidence that suggests higher and/or more consistent dosing of antiretrovirals is needed to achieve HIV protection in the female genital tract as compared to rectal tissues. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cottrell Ml YK, Prince Ha, Sykes C, White N, Malone S, Dellon Es, Madanick Rd, Shaheen Nj, Nelson Ja, Swanstrom, Patterson Kb, Kashuba Adm. Predicting Effective Truvada® PrEP Dosing Strategies With a Novel PK-PD Model Incorporating Tissue Active Metabolites and Endogenous Nucleotides HIV Research for Prevention (R4P) Cape Town, South Africa: 2014. Results from a Phase I study and population pharmacokinetic models indicate that higher and/or more consistent dosing of oral PrEP is needed to achieve sufficient levels of tenofovir in vaginal or cervical tissues, as compared to rectal tissues. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landovitz RJ. PrEP for HIV Prevention: What We Know and What We Still Need to Know for Implementation. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle, WA. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, Jha P, Stirling B, et al. Sexual risk factors for HIV infection in early and advanced HIV epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic overview of 68 epidemiological studies. PloS One. 2007;2:e1001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilcher CD, Tien HC, Eron JJ, Jr, et al. Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;189:1785–1792. doi: 10.1086/386333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24.Celum CL, Delany-Moretlwe S, Mcconnell M, et al. Rethinking HIV prevention to prepare for oral PrEP implementation for young African women. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:20227. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.4.20227. This review article describes a range of options for HIV prevention specific to young African women, and summarizes barriers and opportunities to implementing PrEP among this population. Importantly, this article comprehensively draws upon behavioral, behavioral economic, and biomedical approaches to HIV prevention and includes discussion on the relationship between cognitive development and risk perception among young women. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yi TJ, Shannon B, Prodger J, et al. Genital immunology and HIV susceptibility in young women. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2013;69(Suppl 1):74–79. doi: 10.1111/aji.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ngure K, Heffron R, Mugo N, et al. Intravaginal washing practices and the risk of BV among Kenya and Uganda HIV-1 uninfected and infected women. 20th International AIDS Conference; Melbourne, Austrailia. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR. Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS. 2012;26:F13–19. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller WC, Rosenberg NE, Rutstein SE, Powers KA. Role of acute and early HIV infection in the sexual transmission of HIV. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2010;5:277–282. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a0d3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abu-Raddad LJ, Longini IM., Jr No HIV stage is dominant in driving the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1055–1061. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f8af84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Tsegaye TS, Butler K, Luo W, et al. Repeated Vaginal SHIV Challenges in Macaques Receiving Oral or Topical Preexposure Prophylaxis Induce Virus-Specific T-Cell Responses. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015;69:385–394. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000642. This study demonstrated that female macaques developed T-cell responses while on oral or topical PrEP and exposed to multiple SHIV vaginal challenges, suggesting that PrEP can confer protection in vaginal tissues over time, even when faced with repeat challenges. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia-Lerma JG, Heneine W. Animal models of antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2012;7:505–513. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328358e484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International FH. FEM-PrEP June 2011 Update. 2011 http://femprep.fhi360.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/FEMPrEPFactSheetJune20111.pdf.

- *33.Murnane PM, Heffron R, Ronald A, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention does not diminish the pregnancy prevention effectiveness of hormonal contraception. AIDS. 2014;28:1825–1830. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000290. This analysis provides evidence that TDF-based oral PrEP did not attenuate the effectiveness of hormonal contraception among HIV uninfected women enrolled in the Partners PrEP Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **34.Callahan R, Nanda K, Kapiga S, et al. Pregnancy and contraceptive use among women participating in the FEM-PrEP trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015;68:196–203. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000413. This study identified that women who initiated oral contraceptive pills at enrollment into the FEM-PrEP trial had a higher pregnancy incidence rate and lower adherence to study medication than women who initiated injectable contraception, suggesting that adherence to both daily pill regimens was challenging for trial participants. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *35.Heffron R, Mugo N, Were E, et al. PrEP Is Efficacious for HIV Prevention Among Women Using DMPA for Contraception. Topics in Antiviral Medicine. 2014;22:498. This analysis provides evidence that injectable hormonal contraception did not attenuate the efficacy of TDF-based oral PrEP among HIV uninfected women enrolled in the Partners PrEP Study, suggesting that PrEP is an efficacious HIV prevention strategy for women to use concurrently with injectable hormonal contraception. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Hormonal contraceptive methods for women at high risk of HIV and living with HIV: 2014 guidance statement. Geneva: 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128537/1/WHO_RHR_14.24_eng.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **37.Corneli AL, Mckenna K, Headley J, et al. A descriptive analysis of perceptions of HIV risk and worry about acquiring HIV among FEM-PrEP participants who seroconverted in Bondo, Kenya, and Pretoria, South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17 doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.3.19152. This study presents quantitative results of self-perceived HIV risk assessments that were conducted quarterly among a subgroup of women at two sites of the FEM-PrEP trial who acquired HIV during follow-up, as well as qualitative interviews that assessed risk perception retrospectively after HIV seroconversion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Headley J, Lemons A, Corneli A, et al. The sexual risk context among the FEM-PrEP study population in Bondo, Kenya and Pretoria, South Africa. PloS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106410. This mixed methods study identified multiple and concurrent sexual partners, transactional sex, low condom use, and unknown HIV status of male partners as risk factors that contributed to the high HIV incidence rate observed among female participants in the FEM-PrEP Trial. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **39.Corneli A, Wang M, Agot K, et al. Perception of HIV risk and adherence to a daily, investigational pill for HIV prevention in FEM-PrEP. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;67:555–563. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000362. This study describes the self-perceived HIV risk among a sub-cohort of women enrolled in the FEM-PrEP trial, and identifies that having some level of self-perceived HIV risk was associated with higher adherence to study medication during follow-up. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *40.Martin M, Vanichseni S, Suntharasamai P, et al. The impact of adherence to preexposure prophylaxis on the risk of HIV infection among people who inject drugs. AIDS. 2015;29:819–824. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000613. Adherence to daily oral TDF-based PrEP was higher among females and older injection drug users enrolled in the Bangkok Tenofovir Study, and higher adherence was associated with a higher degree of protection from HIV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haberer JE, Baeten JM, Campbell J, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a substudy cohort within a clinical trial of serodiscordant couples in East Africa. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10:e1001511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **42.Van Der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, et al. Women’s experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PloS One. 2014;9:e89118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089118. This qualitative sub-study nested within the VOICE PrEP trial analyzes female particpant experiences navigating individual, household, organizational, and community level factors in order to adhere to study medication Although blood tenofovir-levels later revealed that < 30% of women had adhered to study medication, few women were willing to acknowledge their own extended low or non-use. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, et al. What’s love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-serodiscordant couples. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2012;59:463–468. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824a060b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **44.Montgomery ET, Van Der Straten A, Stadler J, et al. Male Partner Influence on Women’s HIV Prevention Trial Participation and Use of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis: the Importance of “Understanding”. AIDS and Behavior. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0950-5. Using data from both men and women, this qualitative sub-study nested within the VOICE PrEP trial discusses the direct and indirect influences that male partners had on their female partner’s trial participation and adherence to study medication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **45.Van Der Straten A, Stadler J, Luecke E, et al. Perspectives on use of oral and vaginal antiretrovirals for HIV prevention: the VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19146. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.3.19146. This qualitative sub-study nested within the VOICE PrEP trial highlighted community level factors that influenced female participants adherence to study medication, including stigma associated with HIV infection, the importance of preserving a healthy, HIV uninfected image, and confusion over taking antiretrovirals tablets as an HIV prevention strategy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venkatesh KK, Lurie MN, Triche EW, et al. Growth of infants born to HIV-infected women in South Africa according to maternal and infant characteristics. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2010;15:1364–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **47.Magazi B, Stadler J, Delany-Moretlwe S, et al. Influences on visit retention in clinical trials: insights from qualitative research during the VOICE trial in Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14:88. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-88. This qualitative sub-study nested within the VOICE PrEP trial explores the tension between attending clinical trial participation and the socioeconomic context of women’s lives. Competing priorities such as work, school, and caregiving made it difficult for women to attend study visits and refill prescriptions of study medications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mastro TD, Sista N, Abdool-Karim Q. ARV-based HIV prevention for women - Where we are in 2014. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17 doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.3.19154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *49.Corneli AL, Mckenna K, Perry B, et al. The science of being a study participant: FEM-PrEP participants’ explanations for overreporting adherence to the study pills and for the whereabouts of unused pills. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015;68:578–584. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000525. This qualitative follow-up study among women enrolled in the FEM-PrEP trial includes an explanation of the negative consequences participants perceived to accurately report their study drug adherence, and details what participants did to dispose of study medication they did not ingest. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hendrix CW. Exploring concentration response in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis to optimize clinical care and trial design. Cell. 2013;155:515–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hendrix CW. The clinical pharmacology of antiretrovirals for HIV prevention. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2012;7:498–504. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32835847ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dimitrov D, Boily MC, Marrazzo J, et al. Population-Level Benefits from Providing Effective HIV Prevention Means to Pregnant Women in High Prevalence Settings. PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walensky RP, Park JE, Wood R, et al. The cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection in South African women. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;54:1504–1513. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hallett TB, Baeten JM, Heffron R, et al. Optimal uses of antiretrovirals for prevention in HIV-1 serodiscordant heterosexual couples in South Africa: a modelling study. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8:e1001123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *55.Matthews LT, Heffron R, Mugo NR, et al. High medication adherence during periconception periods among HIV-1-uninfected women participating in a clinical trial of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;67:91–97. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000246. This sub-group analysis found that HIV-uninfected women who became pregnant during the Partners PrEP Study had high adherence to study medication in the 3 months prior to pregnancy. There was no difference in adherence between women who became pregnant and those who did not, providing evidence that PrEP may be an acceptable HIV prevention strategy for women who are attempting pregnancy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *56.Mugo NR, Hong T, Celum C, et al. Pregnancy incidence and outcomes among women receiving preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:362–371. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8735. Results from this study show that pregnancy incidence, birth outcomes, or infant growth did not differ between women randomized to the active TDF-based PrEP arms vs. placebo in the Partners PrEP Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *57.Ying R, Sharma M, Heffron R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis targeted to high-risk serodiscordant couples as a bridge to sustained ART use in Kampala, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:20013. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.4.20013. This study estimates the cost effectiveness of and number of HIV infections averted by providing PrEP and ART to HIV serodiscordant couples in both an open-label demonstration project setting and a government program setting in Uganda. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *58.Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR, Baeten JM, et al. Defining success with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a prevention-effective adherence paradigm. AIDS. 2015;29:1277–1285. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000647. This review includes a comprehensive overview of considerations for prevention-effective adherence to PrEP in the context of public health programs, including a comparison of tools to measure adherence and guidance on counseling messages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang L, Kourtis AP, Ellington S, et al. Safety of tenofovir during pregnancy for the mother and fetus: a systematic review. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2013;57:1773–1781. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balkus J, Zhang J, Nair G, et al. Development of a Risk Scoring Tool to Predict HIV-1 Acquisition in African Women. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2014:A214. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kahle EM, Hughes JP, Lingappa JR, et al. An empiric risk scoring tool for identifying high-risk heterosexual HIV-1-serodiscordant couples for targeted HIV-1 prevention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;62:339–347. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e622d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Amico KR. Adherence to preexposure chemoprophylaxis: The behavioral bridge from efficacy to effectiveness. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2012;7:542–548. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283582d4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Amico KR, Mansoor LE, Corneli A, et al. Adherence support approaches in biomedical HIV prevention trials: experiences, insights and future directions from four multisite prevention trials. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:2143–2155. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0429-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amico KR, Stirratt MJ. Adherence to preexposure prophylaxis: current, emerging, and anticipated bases of evidence. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2014;59(Suppl 1):S55–60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **65.Mccormack S, Dunn D. Pragmatic Open-Label Randomised Trial of Preexposure Prophylaxis: The PROUD Study. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle, WA. 2015; p. 22LB. Self-reported adherence to daily oral TDF-based PrEP was high among men who have sex with men enrolled in the open-label PROUD study and confirmed by blood tenofovir levels. Daily oral PrEP provided 86% protection from HIV. [Google Scholar]

- **66.Baeten J, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, et al. Near Elimination of HIV Transmission in a Demonstration Project of PrEP and ART. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle, WA. 2015; Preliminary results from HIV serodiscordant couples enrolled in the open-label Partners Demonstration Project show a 96% reduction in HIV when the HIV uninfected partner uses daily oral PrEP as a “bridge” until the HIV infected partner sustains ART use. [Google Scholar]

- **67.Heffron R, Morton J, Kidoguchi L, et al. Sustained PrEP Use Among High-Risk African HIV Serodiscordant Couples Participating in a PrEP Demonstration Project. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); Seattle, WA. 2015; Among HIV serodiscordant couples followed in the open-label Partners Demonstration Project, 95% of HIV uninfected partners initiated PrEP at enrollment, and 91% and 84% of participants whose HIV infected partner had not yet initiated ART continued to use PrEP at 6 and 12 months, respectively. These data provide evidence that PrEP as a “bridge” is an acceptable and feasible risk reduction strategy until the HIV infected partner achieves and sustains viral suppression. [Google Scholar]

- **68.Bekker L, Hughes J, Amico R, et al. HPTN 067/ADAPT Background and Methods and Cape Town Results. IAS 2015: 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis Treatment and Prevention; Vancouver, Canada. 2015; Overall adherence was higher and a higher proportion of sex acts were protected by oral TDF-based PrEP among women who were randomized to a daily dosing regimen in the open label ADAPT study, as compared to women who were randomized to less frequent dosing regimens. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kibengo FM, Ruzagira E, Katende D, et al. Safety, adherence and acceptability of intermittent tenofovir/emtricitabine as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among HIV-uninfected Ugandan volunteers living in HIV-serodiscordant relationships: a randomized, clinical trial. PloS One. 2013;8:e74314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clinicaltrials.Gov. Observational Study of HIV Infection in Participants of Seroconvert During Dapivirine Vaginal Ring Trials (# NCT01618058) 2015 Jun 23; www.clinicaltrials.gov.

- 71.Clinicaltrials.Gov. Phase 3 Safety and Effectiveness Trial of Dapivirine Vaginal Ring for Prevention of HIV-1 in Women (ASPIRE) Jun 23, 2015. # NCT01617096. [Google Scholar]

- *72.Spence P, Bhatia Garg A, Woodsong C, et al. Recent work on vaginal rings containing antiviral agents for HIV prevention. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2015;10:264–270. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000157. Given the very low adherence to daily oral study medication observed in two PrEP efficacy trials alternate delivery mechanisms are needed to offer women additional choices. This review summarizes recent and ongoing studies of PrEP delivered as a vaginal ring. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *73.Boffito M, Jackson A, Owen A, Becker S. New approaches to antiretroviral drug delivery: Challenges and opportunities associated with the use of long-acting injectable agents. Drugs. 2014;74:7–13. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0163-7. Given the very low adherence to daily oral study medication observed in two PrEP efficacy trials alternate delivery mechanisms are needed to offer women additional choices. This review summarizes recent and ongoing studies of PrEP delivered as a long acting injectables, including the potential challenges and opportunities for implementing injectables in public health settings. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Myers JE, Sepkowitz KA. A pill for HIV prevention: Déjà vu all over again? Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2013;56:1604–1612. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]