Sir,

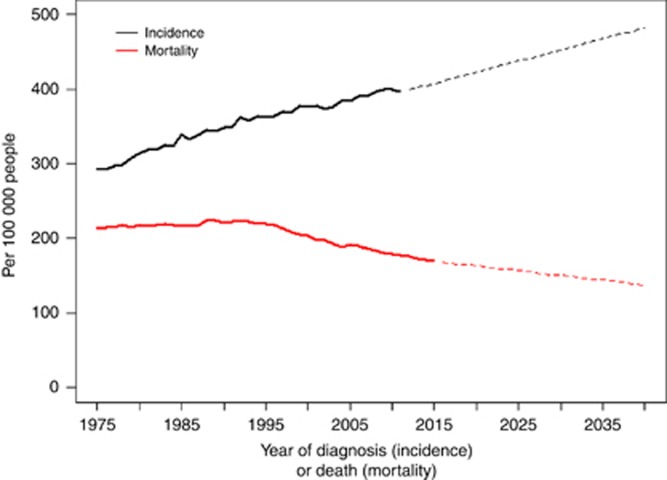

Projections of lifetime risk and cancer incidence for the next 25 years reported by Ahmad et al (2015) are alarming but probably realistic. In the last 30 years, the incidence of all cancers in the United Kingdom has risen from 293 cases per 100 000 persons in 1975 to 396 per 100 000 in 2011 (Cancer Research UK, 2012), a rise of 35%. We were, however, surprised to such limited discussion or analysis of cancer mortality trends over the equivalent time period, which has fallen 21% since 1971 (Cancer Research UK, 2012).

There has been a steady and linear increase over time in cancer incidence (Figure 1, solid black line). Extrapolating this trend forward (black dotted line) using simple linear regression produces incidence rates that generate lifetime and cumulative risks that are broadly in line with Ahmad et al's more sophisticated approach. Using the same method to extrapolate the trend in all-cancer mortality (solid grey line) suggests that all-cancer mortality will continue to decline (grey dashed line). In short, extrapolating current trends forward sends incidence and mortality in different directions, and this suggests a future in which cancer becomes more common but at the same time more benign.

Figure 1.

All-cancer incidence and mortality in the United Kingdom from 1975 to 2011(solid lines) and projected incidence and mortality (dashed lines).

One explanation for detecting increasing levels of cancer on the scale suggested by Ahmad et al without a concomitant increase in mortality is the detection of disease that will not go on to cause symptoms or death: ‘overdiagnosis' (Welch and Black, 2010). This was acknowledged as contributory to the increased incidence in prostate cancer in relation to PSA testing, yet similar trends can be seen for thyroid, kidney, melanoma and breast cancer. Although it is methodologically challenging to take into account the impact of over-diagnosis and its underlying causes, diagnostic drift, increasing test sensitivity and changing competing mortality risks, these are important considerations to note when interpreting incidence data (Carter et al, 2015).

We call on the authors to publish their projected mortality rates to provide greater context to these worrying figures. The public deserve clear information about the drivers behind them, especially given the cumulative risk of over-diagnosis in an ageing population.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad AS, Ormiston-Smith N, Sasieni PD (2015) Trends in the lifetime risk of developing cancer in Great Britain: comparison of risk for those born from 1930 to 1960. Br J Cancer 112: 943–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Research UK (2012) Cancer incidence for all cancers combined. Available from http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/incidence/all-cancers-combined/#UK (accessed on 13 February 2015).

- Cancer Research UK (2012) Cancer mortality for all cancers combined. Available from http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/mortality/all-cancers-combined (accessed on 13 February 2015).

- Carter JL, Coletti RJ, Harris RP (2015) Quantifying and monitoring overdiagnosis in cancer screening: a systematic review of methods. BMJ 350: g7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch HG, Black WC (2010) Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 102(9): 605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]