Abstract

Background:

Studies document that magnesium is inversely associated with the risk of diabetes, which is a risk factor of pancreatic cancer. However, studies on the direct association of magnesium with pancreatic cancer are few and findings are inconclusive. In this study, we aimed to investigate the longitudinal association between magnesium intake and pancreatic cancer incidence in a large prospective cohort study.

Method:

A cohort of 66 806 men and women aged 50–76 years at baseline who participated in the VITamins And Lifestyle (VITAL) study was followed from 2000 to 2008. Multivariable-adjusted Cox regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of pancreatic cancer incidence by magnesium intake categories.

Result:

During an average of 6.8-year follow-up, 151 participants developed pancreatic cancer. Compared with those who met the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for magnesium intake, the multivariable-adjusted HRs (95% CIs) for pancreatic cancer were 1.42 (0.91, 2.21) for those with magnesium intake in the range of 75–99% RDA and 1.76 (1.04, 2.96) for those with magnesium intake <75% RDA. Every 100 mg per day decrement in magnesium intake was associated with a 24% increase in the incidence of pancreatic cancer (HR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.50; Ptrend=0.03). The observed inverse associations appeared not to be appreciably modified by age, gender, body mass index, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use but appeared to be limited to those taking magnesium supplementation (from multivitamins or individual supplement).

Conclusions:

Findings from this prospective cohort study indicate that magnesium intake may be beneficial in terms of primary prevention of pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: Magnesium intake, pancreatic cancer, VITAL study, prospective cohort

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in both men and women in the United States (Strimpakos et al, 2010; Klein, 2012). The overall incidence of pancreatic cancer has not significantly changed since 2002 but the mortality rate has increased an average of 0.4% annually from 2002-2011 (National Cancer Institute, 2014). It was estimated that about 46 420 people in the United States would be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and about 39 590 would die of this disease in 2014 (Siegel et al, 2014).

Approximately 80% of pancreatic cancer patients have concomitant diabetes (Morrison, 2012). Studies show that pancreatic tumour cells have receptors for insulin and have high levels of insulin as in type-2 diabetes and insulin resistance. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) promote pancreatic tumour cell growth (Fisher et al, 1996; Giovannucci, 2003). Because epidemiological studies suggest that magnesium intake is inversely associated with the risk of type-2 diabetes (Kao et al, 1999; Lopez-Ridaura et al, 2004; Song et al, 2004; van Dam et al, 2006; Bo and Pisu, 2008; Villegas et al, 2009; Dong et al, 2011) – a risk factor of pancreatic cancer (Everhart and Wright, 1995; Michaud, 2004; Huxley et al, 2005; Ben et al, 2011; Li et al, 2011), it is reasonable to hypothesise that magnesium intake may decrease the risk of pancreatic cancer. However, data directly relating magnesium intake to the incidence of pancreatic cancer are sparse and the findings are inconsistent. Two case–control studies reported that magnesium intake was inversely associated with the risk of pancreatic cancer (Jansen et al, 2013), whereas another case–control study (Manousos et al, 1981) found no association. Two recent prospective cohort studies, one from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS; Kesavan et al, 2010) conducted only in men and the other from the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC) study, (Molina-Montes et al, 2012) found no association between magnesium intake and the incidence of pancreatic cancer in the total cohort, but both observed an inverse association (borderline in EPIC study) among overweight men. Therefore, we aimed to (1) investigate the longitudinal association between magnesium intake and the incidence of pancreatic cancer, and (2) explore whether age, gender, body mass index (BMI, kg m−2), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use and magnesium supplementation are effect modifiers in this large prospective cohort study.

Materials and Methods

Study participants and design

The authors obtained the data set for this study from the VITamins And Lifestyle (VITAL) study, which was previously described in detail elsewhere (White et al, 2004). In brief, the participants in the VITAL study cohort were recruited from men and women aged above 50 years and living in the 13-county area in Western Washington State covered by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program cancer registry. Baseline recruitment was conducted from Oct 2000 to Dec 2002. During this period, a total of 364 418 questionnaires were mailed for the VITAL study to residents in the covered counties, out of which 79 300 (21.8%) mail recipients responded. Of these, 77 719 questionnaires passed quality control checks in the VITAL study. For the present study, the authors excluded participants with a positive history of pancreatic cancer (n=49) or missing data on history of pancreatic cancer (n=213) at baseline. The authors also excluded individuals with missing data on family history of pancreatic cancer (n=922), education (n=1284), alcohol consumption (n=1215), height and weight (n=2565), or who failed to quality control checks on the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ; n=4657). In addition, the authors excluded eight cases of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour in the analyses. The final sample consisted of 66 806 participants.

Data collection

Data were collected at baseline using a 24-page, self-administered, sex-specific, optically scanned questionnaire that covered three content areas: diet, supplement use, and health history and risk factors.

Diet assessment

Diet was assessed using a FFQ that included adjustment questions on types of foods and preparation techniques. The FFQ was adapted from the one used in the Women's Health Initiative and other studies (Patterson et al, 1999). Participants were asked about their usual consumption frequency and portion size of 120 food items and beverages over the past year. The FFQ analytic program based on nutrient values from the Minnesota Nutrient Data System was used to estimate average dietary nutrient intake per day (Schakel et al, 1997). Total nutrient intake was computed by combining the data on dietary intake and average 10-year daily supplement intake.

Supplement use assessment

Data on supplement use were collected using items of the VITAL questionnaire that covered supplement use during the 10 years before baseline. For multivitamin use, participants were asked about frequency (times per week) and duration of use over the previous 10 years, and either selected one of 16 common brand names or provided dose information on vitamins and minerals in the brand they used. For individual supplements and other combinations (e.g., magnesium plus calcium), closed-ended questions were used to enquire about current vs past use, frequency and duration of use, and average dose per day. The 10-year average daily supplemental intake of each nutrient was computed as (dose used per day) × (number of days used per week/7) × (number of years used/10), and summed over multivitamin intake and individual nutrient supplemental intake.

The VITAL supplement study questionnaire was validated by a study of 220 participants by comparing it with repeated administration of the questionnaire 3 months after baseline and a detailed home interview and supplement inventory (White et al, 2004). Excellent reliability of the questionnaire on mean supplementary magnesium intake over the past 10 years administered at baseline and 3 months later was documented with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.74 and a correlation of 0.69 for current supplemental magnesium intake from the questionnaire compared with the in-home interview and transcription of supplement bottle labels (Satia-Abouta et al, 2003).

Covariate assessment

Participants provided information on personal characteristics including age, gender, ethnicity (White and non-White), education, BMI, recreational physical activity, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, family history of pancreatic cancer, and medical history as part of the baseline questionnaire. The average total metabolic equivalent (MET) hours per week over the past 10 years were estimated based on duration, frequency, and published energy expenditure for different activities in the Compendium of Physical Activities. Smokers were classified as never, current, quit 10 years ago or longer, or quit <10 years ago. Duration and doses of smoking were estimated by the reported number of years of smoking and by the usual number of cigarettes smoked per day, respectively. Pack-years were computed as duration × cigarettes per day/20 (Macleod et al, 2013). Alcohol consumption and intakes of energy, total calcium, selenium, and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids were categorised into tertiles. Diabetes mellitus status, family history of pancreatic cancer, and NSAID use were dichotomised (yes or no).

Outcome ascertainment

Participants were followed from the time of enrolment to 31 Dec 2008. The median follow-up time in the present study was 6.8 years. Participants were followed up passively for outcomes including cancer and death by linking to public databases. Incident cases of pancreatic cancer were ascertained by linking the study cohort to the Western Washington SEER cancer registry, maintained by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center under contract to the National Cancer Institute.

All incident cases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma were identified based on the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) with codes C25.0–C25.3 or C25.7–C25.9. We excluded neuroendocrine tumours (C25.4). The remaining participants were right censored from the analysis at the earliest date of the following events: withdrawal, emigration from SEER catchment area, death or the end of the follow-up period.

Statistical analysis

To increase statistical power, we categorised total magnesium intake into three groups, that is, ⩾100% recommended dietary allowance (RDA) (⩾320 mg per day for females and ⩾420 mg per day for males), 75–99% RDA, and <75% RDA (<240 mg per day for females and <315 mg per day for males) for assessing hazard ratios (HRs) of pancreatic cancer (Institute of Medicine of National Academics, 2015). Baseline characteristics of participants were expressed as means (s.d.), median (interquartile ranges), or proportions and were compared among the three groups using analysis of variance, Kruskal–Wallis, or χ2-test, respectively. Multivariable-adjusted HRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the incidence of pancreatic cancer associated with magnesium intake were calculated using Cox proportional hazard models. The proportional hazard assumption was tested by graphical method and the supremum test (Lin et al, 2002) and it generally holds for all the exposure variables and the potential covariates. To examine the dose–response relationship, we calculated HR with every 100 mg per day decrement in magnesium intake. To control for potential confounders, we used a sequential covariates-adjusted strategy in the Cox models. In model 1, we considered four key demographic variables including age (continuous), gender, race (White or non-White), and education (less than high school graduate, some college, college or advanced degree); in model 2, we additionally adjusted for BMI (<25, 25–29, or ⩾30 kg m−2), physical activity (0, tertiles of MET hours per week), smoking (0, tertiles of pack-years), alcohol consumption (tertiles), diabetes mellitus (yes or no), family history of pancreatic cancer (yes or no), NSAIDs use (yes or no), and total intakes (tertiles) of calcium, selenium, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, and total energy intake. P-values for linear trend were calculated using the continuous variable of magnesium intake excluding the extreme values that were greater than its 99th percentile.

In addition, we examined whether age, gender, BMI (<25 or⩾25kg m−2), NSAIDs use (yes or no), or magnesium supplementation (from multivitamins or individual supplements; users or non-users) was an effect modifier. The P-value for interaction was calculated from the likelihood ratio test by comparing models with and without the interaction term of magnesium intake (continuous) and the potential effect modifiers of interest.

All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All reported P-values are two sided and those that were ⩽0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of participants included in the study according to total magnesium intake. Participants in the present analysis were 51% female and 6% non-White. The average age of participants was 62 years old. Compared with those who met the RDA for magnesium intake, participants with magnesium intake below 75% RDA tended to be males, non-Whites, smoked more, more overweight and were more likely to be diabetic patients. They had lower levels of education and physical activity, and lower intakes of alcohol, calcium, selenium, omega-3 fatty acids, and total energy.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of overall study participants and by levels of total magnesium intake, VITAL Cohort Study, 2000–2008a.

|

Levels of magnesium intake |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total (n=66 806) |

⩾100% RDA (n=35 348) |

75–99% RDA (n=17 063) |

<75% RDA (n=14 395) |

||||||||||

| Characteristics | Mean (s.d.) | Median (IQR) | % | Mean (s.d.) | Median (IQR) | % | Mean (s.d.) | Median (IQR) | % | Mean (s.d.) | Median (IQR) | % | P-valueb |

| Magnesium intake (mg per day) | 405.09 (169.75) | 518.51 (148.94) | 326.74 (50.79) | 219.43 (53.53) | |||||||||

| Calcium intake (mg per day) | 914.0 (510.4) | 1130.3 (552.8) | 769.5 (326.4) | 554.0 (251.0) | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Selenium (mcg per day) | 114.5 (52.4) | 135.9 (55.3) | 101.4 (37.5) | 77.4 (29.9) | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids (g per week) | 1.8 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.1) | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.7) | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Total calories (kcal per day) | 1860.6 (773.6) | 2190.1 (800.8) | 1661.4 (555.8) | 1287.4 (440.3) | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Age, years | 61.7 (7.4) | 61.8 (7.4) | 61.7 (7.4) | 61.6 (7.5) | 0.09 | ||||||||

| BMI (kg m−2) | 27.4 (5.2) | 27.3 (5.2) | 27.5 (5.1) | 27.6 (5.2) | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Female (%) | 50.5 | 52.7 | 47.8 | 48.6 | <0.01 | ||||||||

| White (%) | 93.6 | 94.6 | 93.6 | 91.1 | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Education (%) | <0.01 | ||||||||||||

| High school graduate or less | 18.7 | 16.0 | 19.1 | 24.9 | |||||||||

| Some college | 38.0 | 36.5 | 38.8 | 40.6 | |||||||||

| College or advanced degree | 43.3 | 47.5 | 42.1 | 34.5 | |||||||||

| Physical activity (MET hours per week) | 6.1 (1.3–15.5) | 7.3 (2.0–17.5) | 5.4 (1.2–14.6) | 3.9 (0.6–11.7) | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Smoking (pack-years) | 0.9 (0.0–22.5) | 0.3 (0.0–20.0) | 0.9 (0.0–25.0) | 1.9 (0.0–25.0) | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Alcohol consumption (g per day) | 1.6 (0.0–10.6) | 2.1 (0.0–11.0) | 1.6 (0.0–10.4) | 1.2 (0.0–8.7) | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 6.6 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 7.5 | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Family history of pancreatic cancer (%) | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 0.19 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; IQR=interquartile range; MET=metabolic equivalent; RDA=recommended daily allowance; VITAL=Vitamins and Lifestyle.

The magnesium intake RDA cutoff points used are in females 240 mg (75% RDA) and 320 mg (100% RDA) and in males 315 mg (75% RDA) and 420 g (100% RDA).

Magnesium intake includes both dietary and supplemental sources.

P-values for any difference across the three groups were calculated using analysis of variance (continuous variables that are normally distributed), Kruskal–Wallis test (continuous variables that are not normally distributed or ordinal variables) or χ2-test (proportions) as appropriate.

Table 2 shows the association between total magnesium intake and pancreatic cancer incidence. Compared with those who met the RDA for magnesium intake, the multivariable-adjusted HRs (95% CI) of pancreatic cancer were 1.42 (0.91, 2.21) and 1.76 (1.04, 2.96) for those with magnesium intake at 75–99% RDA and below 75% RDA, respectively. After excluding cases that occurred in the first 2 years, the inverse association generally remained, but somewhat attenuated 1.82 (0.995, 3.31), P=0.052, comparing those below 75% RDA to those who met the RDA. For dose–response analysis, every 100 mg per day decrement in magnesium intake resulted in 24% elevation in incidence of pancreatic cancer (HR (95% CIs): 1.24 (1.02, 1.50), P for linear trend=0.03).

Table 2. Multivariable-adjusted HRs and 95% CIs of incidence of pancreatic cancer by levels of total magnesium intake, VITAL Cohort Study, 2000–2008a.

| Linear trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ⩾100% RDA | 75–99% RDA | <75% RDA | ↓100 mg per day | P-valueb | |

|

Total magnesium intake | |||||

|

Magnesium (mg per day) | |||||

| Mean (s.d.) | 518.51 (148.94) | 326.74 (50.79) | 219.43 (53.53) | ||

| Range | 320–1805 | 240–420 | <315 | ||

| No. of participant at risk | 35 348 | 17 063 | 14 395 | ||

| No. of events | 64 | 43 | 44 | ||

| Model 1c | 1 (Reference) | 1.39 (0.94, 2.05) | 1.71 (1.16, 2.52) | 1.23 (1.06, 1.41) | <0.01 |

| Model 2d | 1 (Reference) | 1.42 (0.91, 2.21) | 1.76 (1.04, 2.96) | 1.24 (1.02, 1.50) | 0.03 |

|

Magnesium supplement users | |||||

|

Magnesium (mg per day) | |||||

| Mean (s.d.) | 529.99 (156.02) | 325.85 (50.94) | 242.62 (43.27) | ||

| Range | 320–1805 | 240–420 | <315 | ||

| No. of participant at risk | 27 016 | 8838 | 3201 | ||

| No. of events | 45 | 21 | 11 | ||

| Model 1c | 1 (Reference) | 1.44 (0.85, 2.43) | 2.13 (1.09, 4.16) | 1.30 (1.04, 1.63) | 0.02 |

| Model 2d | 1 (Reference) | 1.51 (0.80, 2.84) | 2.21 (0.93, 5.26) | 1.33 (0.98, 1.80) | 0.07 |

|

Magnesium supplement non-users | |||||

|

Magnesium (mg per day) | |||||

| Mean (s.d.) | 481.30 (115.39) | 328.04 (50.55) | 213.12 (54.37) | ||

| Range | 320–1309 | 240–420 | <315 | ||

| No. of participant at risk | 8166 | 8112 | 11 010 | ||

| No. of events | 18 | 20 | 30 | ||

| Model 1c | 1 (Reference) | 1.07 (0.56, 2.02) | 1.12 (0.62, 2.03) | 1.05 (0.83, 1.31) | 0.70 |

| Model 2d | 1 (Reference) | 0.99 (0.47, 2.12) | 0.92 (0.34, 2.43) | 0.93 (0.65, 1.33) | 0.88 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; MET=metabolic equivalent; NSAIDs=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; RDA=recommended dietary allowance; VITAL=Vitamins and Lifestyle.

The magnesium intake RDA cutoff points used are in females 240 mg (75% RDA) and 320 mg (100%RDA) and in males 315 mg (75% RDA) and 420 mg (100% RDA).

All models were constructed using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis.

P for trend was calculated using the continuous values (after deleting the extreme values above the 99th percentile) of the exposure.

Model 1: adjusted for age (time variable), gender, ethnicity (White and non-White), and education (high school graduate or less, some college, college or advanced degree).

Model 2: additionally adjusted for body mass index (<25, 25–29, or ⩾30 kg m−2), physical activity (0, tertiles of MET hours per week), smoking (0, tertiles of pack-years), alcohol consumption (tertiles), diabetes mellitus (yes or no), family history of pancreatic cancer (yes or no), use of NSAIDs (yes or no), and total intakes (tertiles) of calcium, selenium, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, and total calories.

When participants were stratified by use of supplemental magnesium (from multivitamins or individual supplements), the linear association became borderline significant in supplement users (HR=1.33 (0.98, 1.80), P for linear trend=0.07, with every 100 mg per day decrement in magnesium intake) and disappeared in supplement non-users (HR=0.93 (0.65, 1.33), P for linear trend=0.88). However, the interaction between supplement use (users vs non-users) and magnesium intake (continuous) was not statistically significant (P for interaction=0.21).

None of age, gender, BMI status, and NSAID use appreciably modified the linear inverse association (data not shown).

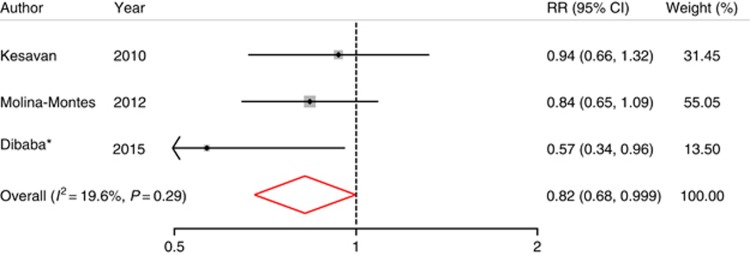

To increase the statistical power, we pooled the relative risk of pancreatic cancer in our study with that of two other cohort studies (Kesavan et al, 2010; Molina-Montes et al, 2012) comparing the highest magnesium intake with the lowest (Table 3). We observed that the pooled result is consistent with our finding (RR=0.82 (0.68, 0.999), P=0.049; Figure 1).

Table 3. Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Source | Participants (n) | Follow-up (years) | Person-years of follow-up | No of cases | Age at baseline (years) | Male (%) | Exposure assessment | Exposure categories | Outcome assessment | Adjusted variables | Measures of association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cohort studies | |||||||||||

| Dibaba TD, 2014, USA | 66 806 | 6.8 | 451 560 | 151 | 50–76 | 49.5 | 120-item FFQ, plus supplement use | Three groups based on RDA: <75% RDA; 75–99% RDA; ⩾100% RDA | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma was identified based on the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) | Age, gender, ethnicity, education, BMI, physical activity, smoking (pack-years smoked), alcohol intake, diabetes, family history of pancreatic cancer, NSAID use, and intakes of calcium, selenium, omega-3 fatty acids, and calories | HR (95% CIs) for total magnesium intake: highest versus lowest: 0.569 (0.338, 0.960). Per 100 mgper day increase: 0.806 (0.667, 0.980) |

| Molina-Montes et al, 2012, Europe | 477 202 | 11.3 | 1 591 205 (men); 3 671 100 (women) | 865 (396 in men and 469 in women) | 25–70 | 29.8 | Country-specific FFQ were used | Quintiles of energy-adjusted magnesium intake (mg per day) <292.9; 292.9–329.8; 329.9–360.8; 360.9–399.9; >399.9 | Linkage with regional or national population-based cancer registries and national mortality registries (ICD-O-3 was used) | Energy intake from fat source, energy intake from non-fat sources, smoking, height, weight, and self-reported diabetes | HR (95% CIs) for energy-adjusted magnesium intake: highest versus lowest: 0.84 (0.65, 1.10). Per 100 mg per day increase: 1.00 (0.82, 1.22) |

| Kesavan et al, 2010, USA | 47 893 | 20 | 851 476 | 300 | 40–75 | 100.0 | Semiquantitative FFQ was used, plus supplement and multivitamin use | Quintiles of total magnesium intake (median, mg per day) 263; 307; 343; 384; 457 | Self-report, and medical record with confirmed with complete histology | Age, BMI, height, history of diabetes (yes/no), physical activity (quintiles of metabolic equivalent task hours per week), smoking history (categories), total caloric intake (quintiles) | RR (95% CIs) for total magnesium intake: 0.94 (0.66, 1.32) |

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; FFQ=food frequency questionnaire; HR=hazard ratio; ICD-O-3=International Classification of Disease 3rd edition, NA=not available; NSAIDs=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OR=odds ratio; RDA=recommended dietary allowance; RR=relative risk; T=tertile.

Figure 1.

Multivariable-adjusted RRs and 95% CIs of pancreatic cancer incidence comparing those in the highest to those in the lowest magnesium intake group from prospective cohort studies. The summary estimate was obtained by using a fixed-effects model. The dots indicate the adjusted RRs. The size of the shade square is proportional to the weight of each study. The horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. The diamond marker indicates the pooled RRs. *The current study. CI=confidence interval; RR=relative risk.

Discussion

Findings from this large prospective cohort study indicate that magnesium intake is modestly and inversely associated with the incidence of pancreatic cancer. This potential benefit is not appreciably modified by age, gender, BMI status, Mg supplement use, or NSAIDs.

Results from the present study are generally consistent with findings from two case–control studies (Jansen et al, 2013), which reported an inverse association between magnesium intake and the risk of pancreatic cancer. In addition, HPFS (Kesavan et al, 2010) found a significant inverse association between magnesium intake and the incidence of pancreatic cancer in overweight men, but not in men with normal weight. However, the study observed a statistically non-significant inverse relation between magnesium intake and the incidence of pancreatic cancer in the entire cohort. The EPIC study (Molina-Montes et al, 2012) found a borderline inverse association between magnesium intake and the incidence of pancreatic cancer in overweight men. In EPIC study, the incidence of pancreatic cancer was reduced by 21% with a 100 mg per day increment in magnesium intake among overweight men. Although findings in the present study are generally in concordance with the two previous cohort studies, we did not observe effect modification by gender or weight status.

None of the previous studies considered effect modification by supplementation. In the present study, we found that the inverse association between magnesium intake and the incidence of pancreatic cancer disappeared in supplement non-users, presumably due to a relatively lower and narrow range of magnesium intake. This observation suggests that, to gain the benefit of magnesium intake, at least meeting the recommended daily allowance for magnesium intake may be needed and dietary magnesium intake alone may not be sufficient.

Magnesium is suggested to have several potential mechanisms of preventing cancer. Epidemiological evidence indicates that magnesium deficiency is a risk factor of insulin resistance and type-2 diabetes (Ma et al, 1995; Rosolova et al, 2000; Wang et al, 2013). A clinical trial indicated that magnesium supplementation improved insulin sensitivity (Guerrero-Romero and Rodriguez-Moran, 2011). Further, studies also suggest that glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, and high insulin concentration, which increase IGF levels by reducing IGF-binding proteins or activating IGF-receptors, may play an important role in carcinogenesis (Giovannucci, 2003; Salvatore et al, 2015). Some pancreatic cancer cell lines including MIA PaCa-2 and Panc-1 tumours possess IGF-1 receptors and are promoted by IGF-1 in vitro (Fisher et al, 1996). A study showed in IGF-1-deficient mice model the burden of pancreatic tumour cell line JC101 was significantly reduced (Lashinger et al, 2011). In magnesium deficient states, a high level of insulin secretion due to type-2 diabetes may thus have a deleterious effect on pancreatic exocrine cells, leading to mutation and transformation to a tumour (Jansen et al, 2012). This is supported by several previous studies. Binding studies have shown pancreatic cancer cells have insulin receptors and high affinity for insulin (Fisher et al, 1996). In vitro studies also showed that insulin promotes growth of hamster pancreatic cancer cell line H2T (Fisher et al, 1998), and rat acinar pancreatic cancer cell lines AR42J (Mossner et al, 1985) and several human pancreatic cell lines including Capan-1, Capan-2, CFPAC-1, HS766T, MIA PaCa-2, Panc-1, ASPC-1,COLO-357, and BxPC-3 (Beauchamp et al, 1990; Takeda and Escribano, 1991; Fisher et al, 1996; Kornmann et al, 1998; Ding et al, 2000). These evidences suggest that the link between magnesium deficiency and pancreatic cancer might be through insulin resistance and type-2 diabetes. In addition, magnesium is required for genomic stability (Anastassopoulou and Theophanides, 2002; Mahabir et al, 2008), DNA duplication and repair (Sahmoun and Singh, 2010), apoptosis (Tam et al, 2003), inhibition of chemical carcinogenesis (Kasprzak and Waalkes, 1986), and reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress (Mazur et al, 2007; Castiglioni and Maier, 2011). A study reported that magnesium ions actively bind to DNA polymerase, altering its structure, and also create a magnesium substrate scaffold to which the enzymes bind during structural conformations before and after chemical reactions for DNA repair and synthesis (Yang et al, 2004). Another study reported that magnesium cations stabilise nucleic acid duplexes and facilitate their folding into the biologically active secondary and tertiary structures and are necessary cofactors for many enzymatic reactions involving nucleic acids (Owczarzy et al, 2008). Magnesium deficiency is associated with increased levels of free radicals and inflammation that might lead to DNA damage and carcinogenesis (Blaszczyk and Duda-Chodak, 2013). Studies (Durlach et al, 1986; Anastassopoulou and Theophanides, 2002) have found that magnesium also acts as a competitive antagonist against some weak carcinogenic chemicals such as lead and cadmium and as a non-competitive antagonist against nickel.

Our study has several strengths that need to be highlighted. First, this study is a fairly large sample size with a long period of follow-up, though we may still have insufficient statistical power in some analyses. Second, information on magnesium supplementation was collected in this study through a validated questionnaire (Satia-Abouta et al, 2003), which enables us to examine the potential effect modification of supplement use. The VITAL study had detailed information on magnesium supplemental intake from multivitamins and individual supplements, allowing a more accurate estimate of total magnesium intake in both male and female participants, compared with prior studies that were either only in males (Kesavan et al, 2010) or collected only dietary magnesium intake (Molina-Montes et al, 2012). However, our study also has limitations. First, we acknowledge that pancreatic cancer is a rare disease, and more incident cases of pancreatic cancer may be needed to achieve sufficient statistical power for some examinations, for example, to test the interactions between magnesium intake and potential effect modifiers. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with the combined results when pooled with the other two studies. Second, measurement errors of diet assessment are inevitable. However, the dietary measurement instruments that we used have been validated and used in other established cohorts. Also, in a prospective study, the bias due to measurement error of the estimated association between magnesium intake and pancreatic cancer would be expected to be toward the null. Finally, because of bioavailability, biomarkers of magnesium status such as ionised serum magnesium levels or cellular magnesium level will help us better understand the potential benefit of magnesium intake with respect to pancreatic cancer prevention.

In conclusion, a high level of magnesium intake (that meet RDA) may be beneficial in terms of primary prevention of pancreatic cancer. Adhering to the RDA for magnesium intake is recommended. To achieve that level, dietary magnesium intake alone may not be sufficient. Magnesium supplementation may help achieve the RDA for magnesium, especially for those who may have an elevated risk of pancreatic cancer, such as those with family history of pancreatic cancer or diabetes mellitus. Further research is needed to confirm our findings and to establish causal inference.

Key messages

The study indicates 100 mg per day decrement in magnesium intake resulted in 24% increase in incidence of pancreatic cancer.

Compared to those who met the RDA for magnesium intake there was 76% increase in incidence of pancreatic cancer in those with <75% RDA magnesium intake.

The observed inverse association was not modified by BMI, gender, and age.

Magnesium intake may be beneficial in the primary prevention of pancreatic cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant to KH from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), (R03CA139261). EW was supported by a grant from National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Health Office of Dietary Supplements (K05CA154337).

Author contributions

All the authors have read and made significant contribution to the study.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

References

- Anastassopoulou J, Theophanides T (2002) Magnesium-DNA interactions and the possible relation of magnesium to carcinogenesis. Irradiation and free radicals. Crit Rev Oncol Hemat 42(1): 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp RD, Lyons RM, Yang EY, Coffey RJ Jr, Moses HL (1990) Expression of and response to growth regulatory peptides by two human pancreatic carcinoma cell lines. Pancreas 5(4): 369–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Q, Xu M, Ning X, Liu J, Hong S, Huang W, Zhang H, Li Z (2011) Diabetes mellitus and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Cancer 47(13): 1928–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczyk U, Duda-Chodak A (2013) Magnesium: its role in nutrition and carcinogenesis. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 64(3): 165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo S, Pisu E (2008) Role of dietary magnesium in cardiovascular disease prevention, insulin sensitivity and diabetes. Curr Opin Lipidol 19(1): 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni S, Maier JA (2011) Magnesium and cancer: a dangerous liason. Magnes Res 24(3): S92–S100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding XZ, Fehsenfeld DM, Murphy LO, Permert J, Adrian TE (2000) Physiological concentrations of insulin augment pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and glucose utilization by activating MAP kinase, PI3 kinase and enhancing GLUT-1 expression. Pancreas 21(3): 310–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong JY, Xun P, He K, Qin LQ (2011) Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care 34(9): 2116–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlach J, Bara M, Guietbara A, Collery P (1986) Relationship between magnesium, cancer and carcinogenic or anticancer metals. Anticancer Res 6(6): 1353–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everhart J, Wright D (1995) Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. A meta-analysis. JAMA 273(20): 1605–1609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WE, Boros LG, Schirmer WJ (1996) Insulin promotes pancreatic cancer: evidence for endocrine influence on exocrine pancreatic tumors. J Surg Res 63(1): 310–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WE, Muscarella P, Boros LG, Schirmer WJ (1998) Variable effect of streptozotocin-diabetes on the growth of hamster pancreatic cancer (H2T) in the Syrian hamster and nude mouse. Surgery 123(3): 315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannucci E (2003) Nutrition, insulin, insulin-like growth factors and cancer. Horm Metab Res 35(11-12): 694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Romero F, Rodriguez-Moran M (2011) Magnesium improves the beta-cell function to compensate variation of insulin sensitivity: double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Eur J Clin Invest 41(4): 405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Barzi F, Woodward M (2005) Type-II diabetes and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer 92(11): 2076–2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine of National Academics (2015) Dietary Reference Intakes Tables and Application.

- Jansen RJ, Robinson DP, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Bamlet WR, de Andrade M, Oberg AL, Hammer TJ, Rabe KG, Anderson KE, Olson JE, Sinha R, Petersen GM (2012) Nutrients from fruit and vegetable consumption reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer. Am J Epidemiol 175: S62–S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen RJ, Robinson DP, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Bamlet WR, de Andrade M, Oberg AL, Rabe KG, Anderson KE, Olson JE, Sinha R, Petersen GM (2013) Nutrients from fruit and vegetable consumption reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer 44(2): 152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao WH, Folsom AR, Nieto FJ, Mo JP, Watson RL, Brancati FL (1999) Serum and dietary magnesium and the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Arch Intern Med 159(18): 2151–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzak KS, Waalkes MP (1986) The role of calcium, magnesium, and zinc in carcinogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol 206: 497–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavan Y, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Michaud DS (2010) A prospective study of magnesium and iron intake and pancreatic cancer in men. Am J Epidemiol 171(2): 233–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AP (2012) Genetic susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. Mol Carcinog 51(1): 14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornmann M, Maruyama H, Bergmann U, Tangvoranuntakul P, Beger HG, White MF, Korc M (1998) Enhanced expression of the insulin receptor substrate-2 docking protein in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 58(19): 4250–4254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashinger LM, Malone LM, McArthur MJ, Goldberg JA, Daniels EA, Pavone A, Colby JK, Smith NC, Perkins SN, Fischer SM, Hursting SD (2011) Genetic reduction of insulin-like growth factor-1 mimics the anticancer effects of calorie restriction on cyclooxygenase-2-driven pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Prev Res (Philia) 4(7): 1030–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Tang H, Hassan MM, Holly EA, Bracci PM, Silverman DT (2011) Diabetes and risk of pancreatic cancer: a pooled analysis of three large case-control studies. Cancer Causes Control 22(2): 189–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z (2002) Model-checking techniques based on cumulative residuals. Biometrics 58(1): 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ridaura R, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Liu S, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Hu FB (2004) Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. Diabetes Care 27(1): 134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Folsom AR, Melnick SL, Eckfeldt JH, Sharrett AR, Nabulsi AA, Hutchinson RG, Metcalf PA (1995) Associations of Serum and Dietary Magnesium with Cardiovascular-Disease, Hypertension, Diabetes, Insulin, and Carotid Arterial-Wall Thickness–the Aric Study. J Clin Epidemiol 48(7): 927–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod LC, Hotaling JM, Wright JL, Davenport MT, Gore JL, Harper J, White E (2013) Risk factors for renal cell carcinoma in the VITAL study. J Urol 190(5): 1657–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahabir S, Wei Q, Barrera SL, Dong YQ, Etzel CJ, Spitz MR, Forman MR (2008) Dietary magnesium and DNA repair capacity as risk factors for lung cancer. Carcinogenesis 29(5): 949–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manousos O, Trichopoulos D, Koutselinis A, Papadimitriou C, Polychronopoulou A, Zavitsanos X (1981) Epidemiologic characteristics and trace elements in pancreatic cancer in Greece. Cancer Detect Prev 4(1-4): 439–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur A, Maier JA, Rock E, Gueux E, Nowacki W, Rayssiguier Y (2007) Magnesium and the inflammatory response: potential physiopathological implications. Arch Biochem Biophys 458(1): 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud DS (2004) Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer. Minerva Chir 59(2): 99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Montes E, Wark PA, Sanchez MJ, Norat T, Jakszyn P, Lujan-Barroso L, Michaud DS, Crowe F, Allen N, Khaw KT, Wareham N, Trichopoulou A, Adarakis G, Katarachia H, Skeie G, Henningsen M, Broderstad AR, Berrino F, Tumino R, Palli D, Mattiello A, Vineis P, Amiano P, Barricarte A, Huerta JM, Duell EJ, Quiros JR, Ye W, Sund M, Lindkvist B, Johansen D, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Roswall N, Li K, Grote VA, Steffen A, Boeing H, Racine A, Boutron-Ruault MC, Carbonnel F, Peeters PH, Siersema PD, Fedirko V, Jenab M, Riboli E, Bueno-de-Mesquita B (2012) Dietary intake of iron, heme-iron and magnesium and pancreatic cancer risk in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition cohort. Int J Cancer 131(7): E1134–E1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison M (2012) Pancreatic cancer and diabetes. Adv Exp Med Biol 771: 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossner J, Logsdon CD, Williams JA, Goldfine ID (1985) Insulin, via its own receptor, regulates growth and amylase synthesis in pancreatic acinar AR42J cells. Diabetes 34(9): 891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (2014) A Snapshot of Pancreatic Cancer: Incidence and Mortality.

- Owczarzy R, Moreira BG, You Y, Behlke MA, Walder JA (2008) Predicting stability of DNA duplexes in solutions containing magnesium and monovalent cations. Biochemistry 47(19): 5336–5353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, Carter RA, Bolton MP, Agurs-Collins T (1999) Measurement characteristics of the Women's Health Initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol 9(3): 178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosolova H, Mayer O, Reaven GM (2000) Insulin-mediated glucose disposal is decreased in normal subjects with relatively low plasma magnesium concentrations. Metabolism 49(3): 418–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahmoun AE, Singh BB (2010) Does a higher ratio of serum calcium to magnesium increase the risk for postmenopausal breast cancer? Med Hypotheses 75(3): 315–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore T, Marfella R, Rizzo MR, Sasso FC (2015) Pancreatic cancer and diabetes: a two-way relationship in the perspective of diabetologist. Int J Surg 21(Suppl 1): S72–S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satia-Abouta J, Patterson RE, King IB, Stratton KL, Shattuck AL, Kristal AR, Potter JD, Thornquist MD, White E (2003) Reliability and validity of self-report of vitamin and mineral supplement use in the vitamins and lifestyle study. Am J Epidemiol 157(10): 944–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schakel SF, Buzzard IM, Gebhardt SE (1997) Procedures for Estimating Nutrient Values for Food Composition Databases. J Food Comp Anal 10(2): 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A (2014) Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64(1): 9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Manson JE, Buring JE, Liu S (2004) Dietary magnesium intake in relation to plasma insulin levels and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 27(1): 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strimpakos AS, Syrigos KN, Saif MW (2010) Translational research in pancreatic cancer. Highlights from the "2010 ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium". Orlando, FL, USA. January 22-24, 2010. JOP 11(2): 124–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y, Escribano MJ (1991) Effects of insulin and somatostatin on the growth and the colony formation of two human pancreatic cancer cell lines. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 117(5): 416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam M, Gomez S, Gonzalez-Gross M, Marcos A (2003) Possible roles of magnesium on the immune system. Eur J Clin Nutr 57(10): 1193–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam RM, Hu FB, Rosenberg L, Krishnan S, Palmer JR (2006) Dietary calcium and magnesium, major food sources, and risk of type 2 diabetes in U.S. black women. Diabetes Care 29(10): 2238–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas R, Gao YT, Dai Q, Yang G, Cai H, Li H, Zheng W, Shu XO (2009) Dietary calcium and magnesium intakes and the risk of type 2 diabetes: the Shanghai Women's Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 89(4): 1059–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JS, Persuitte G, Olendzki BC, Wedick NM, Zhang ZY, Merriam PA, Fang H, Carmody J, Olendzki GF, Ma YS (2013) Dietary magnesium intake improves insulin resistance among non-diabetic individuals with metabolic syndrome participating in a dietary trial. Nutrients 5(10): 3910–3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E, Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Thornquist M, King I, Shattuck AL, Evans I, Satia-Abouta J, Littman AJ, Potter JD (2004) VITamins And Lifestyle cohort study: study design and characteristics of supplement users. Am J Epidemiol 159(1): 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Arora K, Beard WA, Wilson SH, Schlick T (2004) Critical role of magnesium ions in DNA polymerase beta's closing and active site assembly. J Am Chem Soc 126(27): 8441–8453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]