Abstract

The development of effective vaccines for neonates and very young infants has been impaired by their weak, short-lived, and Th-2 biased responses and by maternal antibodies that interfere with vaccine take. We investigated the ability of Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi and Typhimurium to mucosally deliver tetanus toxin fragment C (Frag C) as a model antigen in neonatal mice. We hypothesize that Salmonella, by stimulating innate immunity (contributing to adjuvant effects) and inducing Th-1 cytokines, can enhance neonatal dendritic cell maturation and T-cell activation and thereby prime humoral and cell-mediated immunity. We demonstrate for the first time that intranasal immunization of newborn mice with 109 CFU of S. enterica serovar Typhi CVD 908-htrA and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 carrying plasmid pTETlpp on days 7 and 22 after birth elicits high titers of Frag C antibodies, previously found to protect against tetanus toxin challenge and similar to those observed in adult mice. Salmonella live vectors colonized and persisted primarily in nasal tissue. Mice vaccinated as neonates induced Frag C-specific mucosal and systemic immunoglobulin A (IgA)- and IgG-secreting cells, T-cell proliferative responses, and gamma interferon secretion. A mixed Th1- and Th2-type response to Frag C was established 1 week after the boost and was maintained thereafter. S. enterica serovar Typhi carrying pTETlpp induced Frag C-specific antibodies and cell-mediated immunity in the presence of high levels of maternal antibodies. This is the first report that demonstrates the effectiveness of Salmonella live vector vaccines in early life.

Attenuated Salmonella strains have been successfully used as live vectors to deliver foreign antigens and induce protective immune responses against bacteria, viruses, and parasites in a variety of animal models (28, 43). A few clinical trials have also shown their suitability in humans (14, 45). These phase 1 studies assessed the safety and immunogenicity of live vector vaccine candidates in adults.

Neonates and young infants are highly sensitive to intracellular pathogens, and they could greatly benefit from bacterial live vector vaccines carrying antigens from diverse microorganisms that can protect them against several diseases. It has been difficult to formulate effective vaccines for human newborns and young infants due to their generally feeble, short-lived, and Th-2-type-biased immune responses and the presence of maternal antibodies that can interfere with vaccine take (42). Despite the fact that neonates have immature B cells and dendritic cells (DC) and a reduced number of T cells (21), they can still generate potent Th1-type immune responses, including adult-like CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes, in response to certain antigens such as live replicating viruses (9, 39) and DNA vaccines (15, 16, 22, 51). In animal models, neonatal cell-mediated immunity can also be enhanced by antigens delivered in the presence of adjuvants such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (6, 18), CpG oligonucleotides (4), activators of innate immunity (48) and Th-1 cytokines such as interleukin-12, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (5, 21, 24). Bacterial LPS (6), Mycobacterium bovis BCG alone (19) or combined with IFN-γ (41), and GM-CSF (17) induce maturation and activation of neonatal DC. It is conceivable that other microbial antigens and cytokines have similar effects.

Attenuated Salmonella strains induce strong and sustained Th1-type responses, with production of GM-CSF, interleukin-12, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IFN-γ in animal models (23, 28) and in humans (38, 44). They are also potent inducers of innate immunity, as they express LPS and flagella and contain stimulatory CpG motifs that stimulate Toll-like receptors (46). We reasoned, therefore, that Salmonella-based live vector vaccines could be excellent candidates to prime immune responses at very early stages of life by delivering foreign antigens directly into antigen-presenting cells (APC), while providing a strong Th-1 cytokine milieu and other immunomodulatory signals with the potential to induce neonatal DC maturation and T-cell activation. The capacity of Salmonella to actively express and, if appropriately engineered, secrete foreign antigens makes it an appealing tool to prime the neonatal immune system, circumventing the inhibitory effect of maternal antibodies.

Only a few studies in animal models have addressed the efficacy of neonatal immunization to protect against bacterial pathogens (7, 32, 36). To date there is no information concerning the usefulness of Salmonella strains as live vectors to induce protective responses early in life. In this study we investigated the ability of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CVD 908-htrA, a live vaccine candidate that has proven to be well tolerated and highly immunogenic in human clinical trials, and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261, a well-characterized strain in the murine typhoid model, both expressing tetanus toxin (TT) fragment C (Frag C), to serve as mucosal live vector vaccines in neonatal mice. Frag C was used as a model antigen known to drive Th-2 type responses, which we hypothesized could be altered by the presence of live vector antigens. We also assessed the ability of Salmonella live vectors expressing Frag C to induce immune responses in the presence of maternal antibodies.

We demonstrated that newborn mice tolerated well vaccine doses of as high as 109 CFU. Two doses of CVD 908-htrA given on days 7 and 22 after birth induced Frag C antibody titers far beyond the protective human level (0.01 IU/ml) and within the range that protect adult mice from TT challenge (10), as well as mucosal and systemic immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG antibody-secreting cells (ASC) and T cell-mediated immunity. These responses were observed in vaccinated neonates born to naive or immune mothers, indicating that this vaccine strategy is useful to generate protective immune responses even in the presence of maternal antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs, bacterial strains, and culture conditions.

S. enterica serovar Typhi strain CVD 908-htrA, which harbors aroC and aroD deletions and a mutation in htrA, and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261, harboring an aroA deletion, were used alone or carrying pTETlpp, a plasmid encoding TT Frag C under the transcriptional control of a powerful constitutive promoter (Plpp) (10, 45). All strains were grown in plant-based medium (PBM) (kindly provided by Guido Dietrich, Berna Biotech Ltd., Berne, Switzerland) supplemented with 1% glucose, 0.001% 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and ampicillin at 50 μg/ml when required. Plasmid pTETlpp was introduced into S. enterica serovar Typhi and serovar Typhimurium strains by electroporation (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) as previously described (13). Frag C expression was confirmed by Western blotting (27). Vaccine inocula were prepared as follows. Five individual colonies were resuspended in 5 ml of PBM-DHB (with ampicillin when needed), grown for 6 h, and subcultured into 250 ml of fresh medium for another 18 h at 37°C and 250 rpm (optical density at 600 nm of ∼1.3). Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 0.2 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a final concentration of ∼109 CFU in 5 μl. The number of viable organisms was determined by plating serial dilutions of the inoculum onto PBM-DHB agar with ampicillin as required.

Mice and immunizations.

BALB/c mice (8 to 10 weeks old) purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, Mass.) were bred to produce pups. Breeding cages were checked daily, and new births were recorded. Experimental groups contained two litters (average of six pups per litter), except for dose-response studies, for which only one litter was used in order to be able to test all doses in parallel. Vaccine doses ranging from 106 to 109 CFU were administered intranasally (i.n.) in a 5-μl volume (2.5 μl/nare) that was gradually introduced into the pup's nare with a micropipette (30). The first dose was given on day 7 after birth, and a second dose was given in an identical manner on day 22 after birth. For immunological comparison, 7-day-old mice are believed to approximate the stage of immune maturation of a newborn human (42). In experiments with neonates born to naive mothers, preimmunization sera were obtained from age-matched pups. Neonates from immune mothers were bled prior to vaccination by tail nick. Further bleedings were performed from the retro-orbital sinus every 2 weeks up to day 64 after birth (6 weeks after boost). In order to assess vaccine take in the presence of maternal antibodies, two litters with eight pups each, born to immune mothers (with high levels of Frag C and LPS antibodies) that had been vaccinated as a neonates with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp), were randomly assorted into two groups and immunized i.n. with 109 CFU of CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) or CVD 908-htrA (control) on days 7 and 22 after birth. Pups were nursed by a seronegative foster mother to avoid additional transfer of maternal antibodies through milk, which occurs in rodents but not in humans (47). Sera were stored at −70°C until tested. Animal studies were approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Colonization and persistence of recombinant Salmonella strains in neonatal tissues.

To determine the ability of Salmonella strains to colonize and persist in neonatal tissues in vivo, newborn mice immunized i.n. with 109 CFU of CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) and SL3261(pTETlpp) were euthanatized on days 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 12 postvaccination. Nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT), cervical lymph nodes (CLN), Peyer's patches (PP), lungs, livers, and spleens from three to eight mice were harvested under sterile conditions. Tissue samples from individual animals were evenly divided and incubated in PBM-DHB with or without antibiotic. Following overnight culture at 37°C, bacteria were centrifuged and plated on salmonella-shigella agar (BBL, Becton Dickinson and Co., Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with DHB and ampicillin when needed. Subsequently, Salmonella isolates were cultured on triple sugar iron agar BBL, Becton Dickinson and Co. and tested for agglutination with serotype-specific antiserum (Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Plasmid integrity in Salmonella vaccine strains colonizing neonatal tissues.

Plasmid pTETlpp was extracted from neonatal tissue-derived positive Salmonella isolates in PBM-DHB-ampicillin agar, using a GenElute plasmid miniprep kit (Sigma). Purified plasmid aliquots were mapped by using the restriction enzymes EcoRI (restriction sites in multiple cloning site and within the Frag C gene) and PstI (unique restriction site in backbone plasmid) and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Measurement of antibodies to LPS and Frag C.

Serum antibody titers against Salmonella LPS and Frag C were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (26) with the following modifications. ELISA plates were coated either with S. enterica serovar Typhi LPS (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) or S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LPS (List Biological Laboratories Inc., Campbell, Calif.) at 10 μg/ml in carbonate buffer or with TT Frag C (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, Ind.) at 5 μg/ml in PBS. Frag C-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a were detected with goat anti-mouse-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugates (Roche Diagnostics Corporation) diluted 1:1,000 in 10% dry milk (Nestle USA Inc., Glendale, Calif.) in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. Linear regression curves were plotted for each serum sample, and titers were calculated (through equation parameters) as the inverse of the serum dilution that produces an optical density of 0.2 above the value for the blank (ELISA units per milliliter). Frag C titers were also calculated in international units per milliliter by interpolating regression-corrected optical density values of serum samples in the curve of a mouse Frag C antiserum calibrated in international units per milliliter in parallel with the World Health Organization anti-TT standard by means of the mouse toxin seroneutralization test. The standard antiserum was obtained from mice immunized i.n. with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) to be identical to the test samples.

ASC.

Mice immunized with S. enterica serovar Typhi or Typhimurium alone or carrying pTETlpp were euthanized on day 15 after birth (8 days after the first dose) or on day 70 after birth (7 weeks after the boost). Tissues were removed under sterile conditions, placed in chilled RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL, Carlsbad, Calif.) containing gentamicin (50 μg/ml; Gibco), and maintained on ice. Cells from the NALT were removed from the roof of the palate as described by Wu et al. (49) and resuspended in complete medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μg of gentamicin per ml, and 10% fetal calf serum [Gibco BRL]). Spleens were homogenized, filtered through sterile gauze, and washed in RPMI 1640. Erythrocytes were eliminated by incubating splenocytes (in pellet) with 2 ml of lysis buffer (Sigma) on ice for 10 min. The cells were then washed and resuspended in complete medium. Lungs were processed similarly, with an additional gradient step in Lympholyte M (Cedarlane, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) to isolate mononuclear cells. Microtiter plates (Nalgene Nunc, Rochester, N.Y.) were coated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg of Frag C per ml, washed with PBS, and blocked with complete medium for 1 h at 37°C with 5%CO2. Cells were then added in serial dilutions from 2.5 × 105 to 3.1 × 104 cells/well and incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells incubated in uncoated wells (without antigen) were also included as controls. The next day, plates were washed with PBS-0.05% Tween 20 and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Roche Diagnostics Corporation) or biotin-labeled anti-mouse IgA (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc. [KPL], Gaithersburg, Md.) diluted 1:100 in PBS-1% bovine serum albumin, followed by streptavidin-HRP (5 μg/ml) (Sigma). Spots were developed by adding 100 μl of True Blue substrate (KPL) in an agarose overlay. Dark blue spots were enumerated by using a stereomicroscope. Results are expressed as mean specific IgA or IgG ASC counts per 106 cells from replicate wells. A positive response was defined as >4 spots per 106 cells.

IFN-γ ELISPOT.

Spleens were harvested from mice immunized with S. enterica serovar Typhi or Typhimurium alone or carrying pTETlpp on day 70 after birth, and single-cell suspensions were prepared as described above. Freshly isolated cells (5 × 105 to 6.25 × 104) were added in duplicate to multiscreen HA 96-well nitrocellulose plates (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) previously coated with 5 μg of anti-mouse IFN-γ (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) per ml and blocked with complete RPMI. Frag C was added to a final concentration of 2 μg/ml in complete medium. Controls included cells incubated with complete medium (negative control) or phytohemagglutinin (2 μg/ml; Sigma). After 36 h of incubation, IFN-γ production was evidenced with a biotin-labeled anti-mouse IFN-γ at 2 μg/ml (PharMingen) followed by streptavidin-HRP (Sigma). True Blue (KPL) was used as substrate. Results are expressed as the mean number of IFN-γ spot-forming cells (SFC) per 106 splenocytes from replicate cultures. The threshold level for a positive response was four spots per 106 splenocytes.

T-cell proliferation.

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens of vaccinated and control mice. Antigen-specific T-cell proliferation was measured by culturing 2 × 105 cells/well (triplicate wells) with TT Frag C or bovine serum albumin (control) at 5 μg/ml and hot-phenol-treated whole S. enterica serovar Typhi cells at 2 × 105 cells/well for 6 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. Each cell population was also cultured for 2 days with 2 μg of concanavalin A per ml under the same conditions. Cultures were pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine per ml and harvested 18 to 20 h later. Cellular proliferation was measured by incorporation of [3H]thymidine with a Microbeta counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland). Results are expressed as the stimulation index, calculated as the ratio of counts per minute in cells incubated with the antigen to counts per minute of cells incubated with medium alone, and reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for replicate cultures.

Statistical analysis.

Antibody titers, frequencies of ASC and IFN-γ SFC, and counts per minute, measured in vaccinated and control mice at different time points, were compared by using the t test or the Mann-Whitney test (if normality failed). Differences with P value of <0.05 were considered significant. All calculations were performed with SigmaStat software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

RESULTS

Optimization of dosing regime for safety and immunogenicity of S. enterica serovar Typhi as a live vector in neonatal mice.

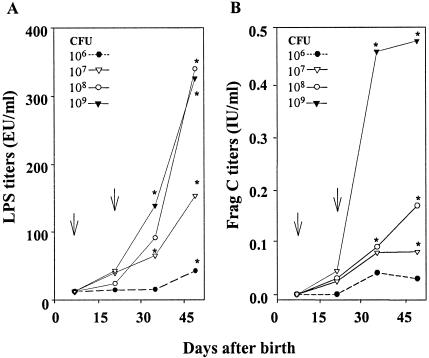

In previous studies with adult mice, we showed that antibody and cell-mediated immune responses induced by recombinant S. enterica serovars Typhi and Typhimurium delivered i.n. were markedly higher than the responses induced by the same vaccines following orogastric delivery. Therefore, we pursued the i.n. route of immunization in neonates. We first sought to determine the highest dose of live attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhi that could be given to newborn mice to induce the strongest immune responses while still being safe and well tolerated. Litters of 5 to 10 mice were inoculated i.n. on day 7 after birth with either 106, 107, 108, or 109 CFU (in 5 μl) of CVD 908-htrA expressing Frag C from the prokaryotic expression plasmid pTETlpp. A second dose was given 15 days later (day 22 after birth) in an identical manner. Pups were monitored daily after vaccination for normal motility, food intake, and any sign of illness. All four dosage levels of live vector were well tolerated, and no signs of adverse effects were observed throughout the immunization schedule. Neonates were able to induce strong IgG responses to both LPS and Frag C (Fig. 1). The highest LPS responses were observed in mice that received either 108 or 109 CFU of CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp), whereas the highest Frag C responses were obtained only with the dose of 109 CFU (Fig. 1). Consequently, doses of 109 vaccine organisms were used in subsequent experiments. Although the first dose was able to successfully prime the immune system, as described below, two doses of vaccine were required to obtain high LPS and Frag C titers.

FIG. 1.

Serum IgG responses to S. enterica serovar Typhi LPS (A) and Frag C (B) induced by newborn mice immunized with increasing doses of CVD 908-htrA carrying pTETlpp. Neonatal BALB/c mice (5 to 10 pups/group) were immunized i.n. on days 7 and 22 after birth with 106 to 109 CFU of CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp). Arrows indicate each immunization. IgG antibodies to LPS and Frag C were measured by ELISA. LPS titers are expressed in ELISA units (EU) per milliliter (end point titers) as described in Materials and Methods. Frag C titers are expressed in international units of TT neutralizing antibodies per milliliter by extrapolation in the curve of a mouse Frag C control serum calibrated in international units per milliliter against the World Health Organization standard by the in vivo neutralization test in mice. The data represent mean titers in each group. Significant differences between pre- and postimmunization titers are indicated (*, P < 0.05).

Antibody responses in neonatal mice immunized with S. enterica serovars Typhi and Typhimurium expressing Frag C.

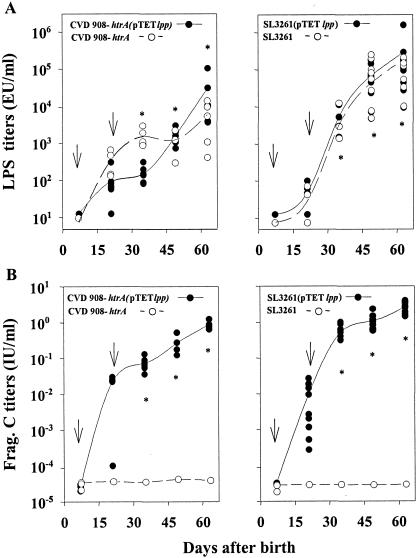

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine candidates have been traditionally tested by using orogastric infection in mice (the “mouse typhoid” model). However, due to the small size of the animals, orogastric inoculation with a gavage needle proved to be technically unfeasible in neonates. Borrowing from our success with S. enterica serovar Typhi, we investigated whether S. enterica serovar Typhimurium could be given i.n. to neonatal mice to induce responses to the foreign antigen. We observed that serovar Typhimurium vaccine strain SL3261 expressing Frag C from pTETlpp delivered i.n. to 7-day-old mice as a single dose of 109 CFU was also well tolerated and highly immunogenic (data not shown). We next compared the kinetics of immune responses in neonates immunized on days 7 and 22 after birth with either serovar Typhi CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) or serovar Typhimurium SL3261(pTETlpp). Control mice received the parent strains alone. The results are summarized in Fig. 2. Both Salmonella vaccines induced remarkably high IgG anti-LPS antibody levels (Fig. 2A). No differences were observed between LPS titers in response to either strain alone or carrying pTETlpp throughout the experiment. LPS responses induced by SL3261 were consistently higher and more steady than those induced by CVD 908-htrA.

FIG. 2.

Serum IgG responses to LPS and Frag C in mice immunized as neonates with Salmonella live vector vaccines. Mice were immunized i.n. on days 7 and 22 after birth with 109 CFU of CVD 908-htrA or SL3261 alone or carrying plasmid pTETlpp. Data represent individual titers in 5 to 10 pups per group. Lines are plotted upon the geometric mean titers for each time point. Arrows indicate each immunization. Significant differences between preimmunization titers and titers achieved after two doses are indicated (*, P < 0.05).

Concerning the Frag C responses, neonates immunized with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) or SL3261(pTETlpp) both induced strong serum IgG titers that were at least 2 orders of magnitude higher than the protective tetanus antitoxin level for humans (0.01 IU/ml) (Fig. 2B). Similar titers have been shown to protect mice from intraperitoneal challenge with 100 50% lethal doses of TT (10). The highest responses, seen in mice immunized with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium expressing Frag C, reached a mean titer of 4 IU/ml on day 64. Mice immunized with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) also attained high Frag C titers (1.0 IU/ml on day 64), although these titers were significantly lower (P = 0.007) than those induced by SL3261(pTETlpp). The ability of recombinant Salmonella SL3261 to prime immune responses against the vector and foreign antigens was particularly noticeable, as shown by the sharp increase in antibody titers that occurred promptly after the boost. No Frag C responses were detected in control groups that received Salmonella parental strains alone. Notably, antibody responses to LPS and Frag C in mice vaccinated as neonates, 64 days after birth, were of a magnitude similar to those measured in adult mice immunized with the same vaccines (data not shown).

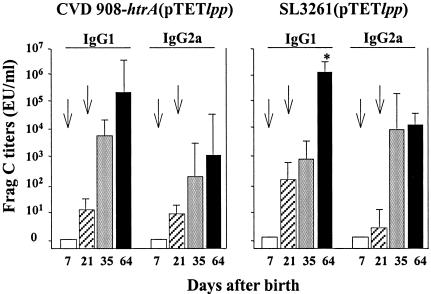

Frag C-specific IgM antibodies were found at equal or slightly higher levels than IgG antibodies 1 week after the first dose, whereas only IgG was observed after the second dose (data not shown). Both IgG1 and IgG2a anti-Frag C antibodies were detected after the booster dose with either vaccine strain (Fig. 3). A slightly higher IgG1/IgG2a ratio was observed in neonates that received SL3261(pTETlpp) after the boost, whereas mice that received CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) showed equivalent levels of IgG1 and IgG2a. The level of Frag C titers and isotype profile described were maintained for at least 4 months (the last time point tested).

FIG. 3.

Serum IgG subclass responses to Frag C in mice immunized neonatally with Salmonella live vector vaccines. Neonatal mice were immunized with CVD 908-htrA or SL3261 carrying pTETlpp as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Serum IgG2a and IgG1 anti-Frag C levels were measured by ELISA and expressed in ELISA units (EU) per milliliter. Arrows indicate each immunization. Data represent the mean titer for each group ± standard deviation. The significant difference between IgG1 and IgG2a on day 64 in mice that received SL3261(pTETlpp) is indicated (*, P < 0.05).

Mucosal immune responses.

Since vaccination through the nasal route has the potential to induce mucosal protective responses, we investigated the induction of IgG and IgA ASC in the nasal tissue and lungs of mice immunized as neonates with Salmonella live vector vaccines. We also compared the frequencies of mucosal and systemic ASC after each vaccine dose. The results are shown in Fig. 4. Both IgG and IgA Frag C-specific ASC were demonstrated in nasal tissue and lungs following neonatal immunization with SL3261 or CVD 908-htrA carrying pTETlpp; responses were readily detected 1 week after the first dose (day 15) and were still present 7 weeks after the boost (day 70 after birth). Equal frequencies of IgG- and IgA-secreting cells were found in the NALT, whereas predominantly IgA-secreting cells were demonstrated in the lungs after each dose. A higher frequency of IgA ASC was observed in lungs from mice immunized with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) than in lungs from those receiving SL3261(pTETlpp). Strong IgA and IgG ASC responses were produced by spleen of mice immunized as neonates with either Salmonella strain, particularly after the booster. No ASC were found in mice immunized with Salmonella parent strains (controls). An important observation was that mucosal and systemic ASC were detected shortly after the first dose, despite the low levels of systemic antibodies, and, surprisingly, they persisted for at least 7 weeks after the second dose.

FIG. 4.

Mucosal and systemic ASC induced by neonatal immunization with Salmonella live vector vaccines. Neonatal mice were immunized with CVD 908-htrA (A) or SL3261 (B) carrying pTETlpp as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Cells from NALT, lungs, and spleens were obtained on day 15 after birth (8 days after the first dose) and on day 70 (7 weeks after the booster). Frag C-specific IgG and IgA ASC responses were measured by ELISPOT with freshly isolated cells. Cells isolated from the same tissues from mice immunized with CVD 908-htrA and SL3261 alone served as control; spots in these wells were <4 ASC/106 cells. Data represent the mean ASC frequency per 106 cells ± standard deviation for replicate cultures.

Cell-mediated immunity.

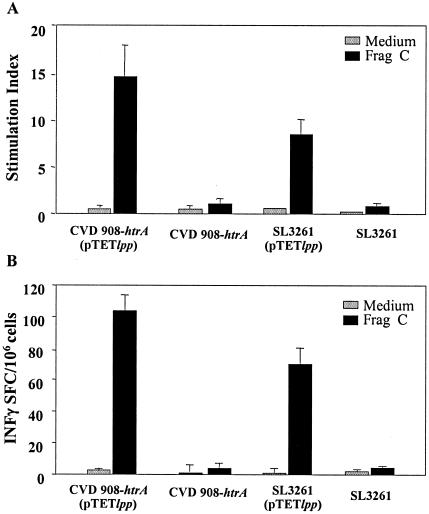

We also examined whether mice immunized as neonates with Salmonella live vectors developed cell-mediated immunity to vaccine antigens. Frag C-specific T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ secreting cells in response to neonatal immunization with SL3261 or CVD 908-htrA carrying pTETlpp were measured in spleen (Fig. 5). Although responses appeared to be higher in mice immunized with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp), this difference was not statistically significant when data from all experiments were analyzed in aggregate. Splenocytes from mice immunized with Salmonella strains alone did not show proliferation or IFN-γ production after Frag C stimulation.

FIG. 5.

Frag C-specific T-cell responses in mice immunized as neonates with Salmonella live vector vaccines. Mice were immunized with CVD 908-htrA or SL3261 alone (control) or carrying pTETlpp as described in the legend to Fig. 2, and spleens were harvested on day 70 after birth. (A) Proliferative responses were measured upon in vitro stimulation with Frag C or medium alone (control) for 6 days. Results are expressed as mean stimulation index, calculated as counts per minute in cells stimulated with antigen/control, ± SEM for triplicate wells. (B) IFN-γ secretion by spleen cells stimulated in vitro with Frag C was measured by ELISPOT. Data represent the mean frequency of IFN-γ SFC/106 splenocytes ± SD for replicate cultures.

In vivo colonization and persistence of Salmonella vaccine organisms and plasmid stability.

The ability of the vaccine organisms to invade and persist in the host tissues and the stability of the plasmid in vivo are considered to be critical elements for live vectors to efficiently prime immune responses against heterologous antigens. We assessed the abilities of S. enterica serovars Typhi and Typhimurium carrying pTETlpp to invade and persist in different tissues following i.n. delivery. Because of the difficulty of working with such small amounts of tissue from individual pups, and to increase the chances of detecting bacteria, we performed an overnight culture enrichment in broth, followed by subculture onto salmonella-shigella agar with and without antibiotic. We also assessed the integrity of pTETlpp purified from in vivo vaccine isolates. Newborn mice immunized i.n. 7 days after birth with 109 CFU of CVD 908-htrA or SL3261 carrying pTETlpp were euthanatized at different time points (days 1 to 12) after vaccination, and NALT, PP, CLN, lungs, spleens, and livers were harvested. The kinetics of recovery of S. enterica serovars Typhi and Typhimurium, alone or carrying plasmid pTETlpp, from three to eight individual mice at each time point are shown in Fig. 6.

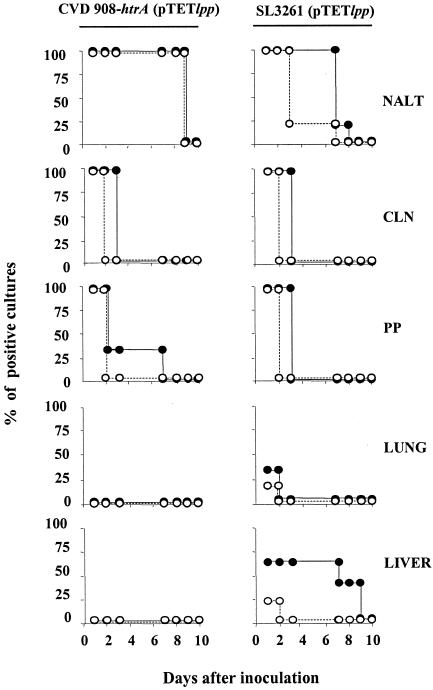

FIG. 6.

In vivo distribution and persistence of mucosally delivered Salmonella live vector vaccines in neonatal mice. Groups of three to eight neonates were immunized i.n. with 109 CFU of CVD 908-htrA or SL3261 carrying pTETlpp. NALT, CLN, PP, lungs, and livers were harvested at different time points from day 1 to 12 postimmunization. The presence of vaccine organisms was determined by culturing tissues from individual mice with or without antibiotic as described in Materials and Methods. Curves indicate the percentages of cultures positive for Salmonella (•) and for Salmonella harboring plasmid pTETlpp (○) for up to 10 days after vaccination.

S. enterica serovar Typhi carrying pTETlpp was recovered from the nasal tissue at all time points until day 8 postvaccination and was also found in the PP and CLN at 24 h after vaccination. Bacteria persisted in the CLN at 48 h after immunization, although the plasmid could no longer be recovered at this time point. Positive bacterial cultures (without plasmid) were found in PP until day 7 in a small proportion of animals. Serovar Typhi was never found in the lungs, liver, or spleen in repeated experiments. Serovar Typhimurium was found in the NALT for up to 7 days after vaccination; however, most of the isolates had lost the plasmid by day 3. Vaccine organisms also colonized the CLN and PP, persisting for up to 3 days, although the plasmid was no longer present after the first day. SL3261 was found in the spleen at 24 h after immunization and in the liver for up 8 days, but again the plasmid was recovered only the day after vaccination. Lung cultures were mostly negative; only one out of six neonates had a positive SL3261(pTETlpp) isolate following vaccination. However, when the volume in which vaccine organisms were delivered was increased from 5 to 8 μl, both serovars Typhi and Typhimurium carrying pTETlpp were readily detected in the lungs. The plasmid recovered from in vivo isolates remained intact. The persistence of vaccine organisms was monitored for 12 days following vaccination, although none of the tissues contained live organisms after day 9. No bacterial growth was observed in control tissues from unvaccinated animals (negative controls).

Immunogenicity of Salmonella live vector vaccines in the presence of maternal antibodies.

Maternally derived passive antibodies are known to interfere with the induction of active immunity, creating an obstacle to early immunization against various pathogens (3). In order to investigate whether live vectors could induce Frag C responses in the presence of maternal antibodies, we bred pups from 3- to 4-month-old females that had been immunized as neonates with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) and had maintained high antibody levels since then.

Our first observation was that Frag C maternal IgG was being transferred to the neonates by placenta as well as milk. Increasing IgG Frag C-specific antibodies were found in sera of naive neonates nursed by immune mothers during the 3 weeks of suckling.

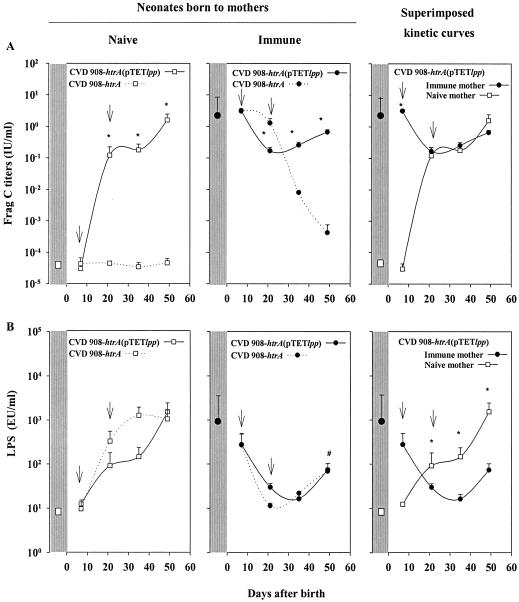

Since humans acquire systemic maternal antibodies exclusively via the placenta (47), we designed our experiment to assess only the potential interference of placentally derived antibodies. Thus, to parallel what occurs in humans, pups from immune mothers were transferred to seronegative (naive) foster mothers at birth. Pups born to a naive mother were used as control. In both cases, half of the litter were immunized on days 7 and 22 after birth with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp), while the other half received CVD 908-htrA as a control. Frag C and LPS antibodies were monitored prior to and every 2 weeks after immunization. The results are presented in Fig. 7.

FIG. 7.

Serum IgG responses to Frag C (A) and S. enterica serovar Typhi LPS and (B) induced by neonates born to naive and immune mothers after immunization with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp). Two litters born to immune or naive mothers were used. Half of each litter received CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) and the other half received CVD 908-htrA (control) on days 7 and 22 after birth as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Pups were nursed by a foster mother to avoid further transference of maternal antibodies through milk. IgG antibodies to LPS and Frag C were measured by ELISA. The left panels show Frag C and LPS titers in neonates born to naive mothers, the central panels show titers in neonates born to mothers that were immune for Frag C and LPS, and the right panels show the superimposed curves of antibody production for neonates born from naive and immune mothers that received CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp). Mean Frag C or LPS titers in maternal sera at the moment of delivery for naive and immune mothers are indicated. Mean Frag C and LPS titers for each vaccinated group are indicated. Arrows indicate each immunization. Statistically significant differences between groups at different time points (*, P < 0.05) and significant differences between LPS titers in vaccinated neonates born to immune mothers on day 49 versus day 7 (#, P < 0.05) are indicated. EU, ELISA units.

Neonates born to naive mothers that received CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) induced Frag C titers at levels similar to those described above. No responses were elicited in control mice that received CVD 908-htrA alone (Fig. 7A). Frag C titers in immune mothers at the time of delivery were almost identical to those found in their offspring on day 7, prior to immunization. Frag C titers declined progressively in mice born to immune mothers that received CVD 908-htrA (control), falling below protective levels at 5 weeks after birth and finally disappearing 2 weeks later. Siblings from the same litter that were immunized with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) showed an initial decrease in Frag C titers during the 2 weeks that followed the first dose. Frag C titers in this group measured prior to the boost (day 21) were significantly lower (P = 0.007) than those in siblings from the same litter that received CVD 908-htrA (control). However, after the booster dose with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp), Frag C antibody responses “turned around,” with a sharp increase. Superimposed kinetics curves of Frag C responses elicited by neonates born to naive and immune mothers are shown in Fig. 7, right upper panel. Despite the fact that one group had preexisting immunity, both groups reached the same titers at 2 weeks after the first dose (day 21 after birth), and the kinetics of antibody increase were identical thereafter.

Neonates born to naive mothers that received CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) or CVD 908-htrA induced high LPS responses that reached similar levels on day 49 after birth (Fig. 7B). The LPS titers measured in immune mothers at the time of delivery were slightly lower than those observed in their progenies, although they were not significantly different. Neonates born to immune mothers vaccinated with CVD 908-htrA or CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) showed an abrupt decrease in LPS titers following the first dose. These titers increased after the second dose in mice receiving either vaccine, but not as prominently as Frag C antibodies. LPS titers remained low and did not reach the levels developed by naive neonates. The kinetics of LPS responses show that neonates born to naive mothers that received either CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) or CVD 908-htrA responded with LPS titers that were 2 log units higher than those of neonates born to immune mothers, and this pattern was maintained at least until day 49 (P = 0.01).

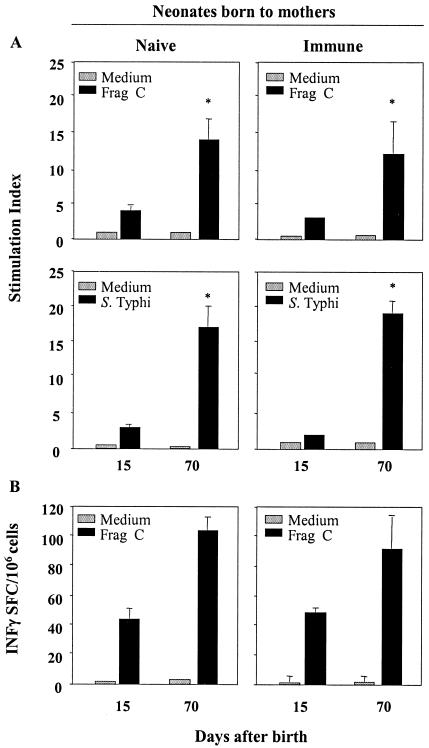

We also investigated the induction of cell-mediated immunity to vaccine antigens in mice born to immune mothers (Fig. 8). T-cell proliferative responses against Frag C and S. enterica serovar Typhi antigens (Fig. 8A) as well as high frequencies of Frag C-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells (Fig. 8B) were elicited by neonates born to immune mothers after the first dose of CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp), despite the high levels of maternal antibodies present at the time. These responses were significantly enhanced by a subsequent vaccine boost. There were no differences in the magnitudes of proliferative responses and cytokine production between neonates born to naive and immune mothers. These data demonstrate that mucosally delivered S. enterica serovar Typhi as a live vector can generate T-cell responses very early in life regardless of the maternal immune status.

FIG. 8.

T-cell responses to bacterial and foreign antigens induced by neonates born to naive and immune mothers after immunization with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp). Neonatal mice from the same litter were immunized with CVD 908-htrA(pTETlpp) or CVD 908-htrA (control) on days 7 and 22 after birth as described in the legend to Fig. 7. Spleens were harvested on day 15 after birth (8 days after the first dose) and on day 70 (7 weeks after the booster). (A) T-cell proliferative responses to S. enterica serovar Typhi antigens and Frag C were measured in mice born to naive or immune mothers after each vaccine dose. Results are expressed as mean stimulation index ± SEM. Significant differences between stimulation indices measured on day 15 and 70 after birth are indicated (*, P < 0.05) (B) The frequency of Frag C-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells was measured by ELISPOT. Data represent mean IFN-γ SFC ± standard deviation for replicate cultures.

DISCUSSION

The novel contribution of this report is the demonstration that two well-characterized Salmonella live vaccine strains, serovar Typhi CVD 908-htrA and serovar Typhimurium SL3261, are well tolerated and can serve as mucosal live vectors to deliver a foreign antigen to neonatal mice, inducing potent mucosal and systemic immune responses. This vaccine strategy was equally efficient in neonates with or without transplacentally acquired antibodies. Surprisingly, newborns tolerated doses of Salmonella of as high as 109 CFU. An interesting observation was made with respect to the relationship between the dose of vaccine given and the immune responses induced. Although peak levels of LPS antibodies were attained with 108 CFU of serovar Typhi, a dose 1 log unit higher was required to maximize Frag C responses. Since LPS abounds on the surface of the bacteria, a lower dose (108 CFU) suffices to reach the maximum response in this model. The responses to the foreign antigen, however, are highly dependent on the amount of protein expressed and therefore required 10-fold more recombinant organisms to reach peak levels.

Mucosal antigen (particularly soluble antigen) encounter early in life often results in a state of systemic nonresponsiveness (tolerance). Such failure to mount a response is a major hurdle to mucosal vaccine development (31). We demonstrate that in neonates, mucosally delivered Salmonella live vectors do not induce tolerance; to the contrary, mucosal and systemic responses were primed after one dose 7 days after birth and were rapidly boosted with a second dose 15 days later. Frag C titers induced by neonatal immunization with Salmonella expressing Frag C were in the range of those that protected adult mice from intraperitoneal challenge with TT (10, 34, 35). It is interesting that neonates responded so efficiently to a shortened immunization schedule consisting of two doses 15 days apart, whereas a 28-day interval was required to achieve similar Frag C responses in adult mice (29, 30).

Neonatal immature CD4+ T cells usually polarize towards a Th2 rather than a Th1 pattern upon immunization (2, 8, 33). A dominant Th2 response to tetanus toxoid has been shown in 4- to 12-month-old human infants who received diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine (37). Frag C or tetanus toxoid delivered intramuscularly also induces Th2-biased responses in adult mice (27). Salmonella vaccines, however, shifted this profile in neonatal mice to a mixed Th1- and Th2-type immune response, characterized by Frag C-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies and IFN-γ secretion. This profile was evident after the first dose and persisted in the form of memory for at least 4 months after the final boost (the last time point assessed). Similarly, BCG vaccination in newborn humans was found to enhance T- and B-cell responses to foreign antigens, promoting the production of both Th1- and Th2-type cytokines (25).

The immune response to both a foreign antigen and the live vector depends on the ability of the mucosally delivered bacterial strain to be taken up by inductive sites, replicate, and persist in immunologically relevant host cells. Another critical factor is the stability of the plasmid to enable vigorous and sustained expression of the foreign antigen to prime immune responses, as discussed above (11). We investigated the neonatal tissues in which Salmonella resides following i.n. delivery, the length of time that vaccine organisms persisted, and the stability of the plasmids in the recovered strains. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, a natural murine pathogen, had a broader distribution and longer persistence than S. enterica serovar Typhi. This could explain the robust humoral immune responses observed. On the other hand, plasmid instability appeared to be more pronounced for serovar Typhimurium, perhaps due to its active replication in murine tissues, which increases the chances of plasmid loss, whereas serovar Typhi is crippled in the murine environment. This explanation is feasible, since pTETlpp does not contain partitioning loci to ensure that both daughter cells inherit the plasmid.

In our model of i.n. delivery, colonization and persistence of vaccine organisms in the nasal tissue appear to be the key events linked to priming of immune responses. Previous observations in our laboratory suggest that the NALT is a critical inductive site of immune responses. Macrophages and dendritic CD11b+ cells are recruited to the NALT at 10 to 16 h after vaccination, and a large proportion of these cells contain Salmonella antigens intracellularly. These cells have the capacity to act as antigen-presenting cells, inducing in vitro proliferation of Salmonella-specific CD3+ T cells (M. F. Pasetti et al., unpublished results).

Neonatal immunization with Salmonella live vectors generated strong mucosal Frag C responses. Frag C-specific mucosal ASC were observed in nasal and lung tissues shortly after the first dose, despite the low systemic antibody responses observed at that time. Mucosal ASC were maintained as memory long after the boost. At later time points the serum antibody levels soared, suggesting that mucosal and systemic antibody responses constitute independent effector mechanisms. A similar lack of correlation between the kinetics of ASC responses with serum antibodies has been reported for adult mice immunized orally with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 expressing Frag C (1). Our results are highly encouraging, as they indicate that the live vector strategy can be useful to raise mucosal responses in young infants to prevent infection from pathogens whose main port of entry is the respiratory or gastrointestinal mucosa.

Another important observation made in this study is that S. enterica serovar Typhi live vectors can induce potent neonatal responses to a foreign antigen, even in the presence of high levels of maternal antibodies that may interfere with other forms of vaccination. The slight decline in Frag C titers observed in neonates from immune mothers following the first dose, 7 days after birth, is likely due to the formation of antigen-antibody complexes that were rapidly cleared from circulation. Nonetheless, Frag C titers rose quickly after the boost given 15 days later, reaching the same levels observed in neonates born to naive mothers (Fig. 7). The mechanisms by which Frag C, which remains intracellularly within the live vector, stimulates B cells without significant interference from maternal antibodies are unclear. Since this antigen is highly immunogenic, only small quantities of free antigen (released from the bacteria or leaked from apoptotic infected cells) could be sufficient to activate B cells. Moreover, antigen released within APC following bacterial infection can be presented to T-helper cells that will drive B-cell differentiation towards FragC-specific ASC.

Maternal LPS antibodies, in contrast, initially inhibited neonatal responses to LPS following S. enterica serovar Typhi vaccination. It was only when maternal antibodies had almost disappeared that neonatal LPS responses started to raise. The reasons for this phenomenon are unknown. Most likely, maternal antibodies bind to LPS B-cell epitopes and prevent B-cell stimulation. It is interesting that placentally transferred maternal LPS antibodies appear to interfere with the responses to live vector but not with the responses to the foreign antigen. Maternal antibodies forming immunocomplexes to LPS on the bacterial surface can rapidly clear vaccine organisms. Presumably, by this time soluble Frag C or, alternatively, vaccine organisms expressing Frag C have already reached the APC, where they are protected from antibody inhibition.

Cell-mediated immunity against Frag C and bacterial antigens was unaffected by maternal immunity. Our results are in line with previous reports showing that vaccine-induced T-cell responses appear to remain intact despite the presence of maternal antibodies (12, 40). This can be attributed to the incapacity of maternal antibodies to interfere with vaccine antigens that, following cell invasion, become available for presentation via major histocompatibility complex molecules (40). It is also likely that maternal antibodies may enhance live vector uptake by APC through opsonophagocytosis.

It has been reported that novel vaccine formulations capable of overcoming passive antibody inhibition, such as DNA vaccines (20) or recombinant viruses (50), entail active antigen expression, whereas inert vaccines, such as proteins, peptides, and killed viruses, or live vaccines displaying target antigens, such as attenuated viruses, are blocked by maternal antibodies.

The results from this study are, to the best of our knowledge, the first to demonstrate that bacterial live vector vaccines can be efficient mucosal delivery vehicles for a foreign antigen, inducing potent immune responses very early in life even in the presence of maternal antibodies. The ability of the live vector to induce such strong humoral and cell-mediated immunity likely reflects the capacity of Salmonella to provide immunomodulatory signals that enhance neonatal DC, B-cell, and T-cell function. These findings are encouraging and support their investigation in human infants.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and NIH grant R01-AI29471 (to M.M.L) and by awards from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, University of Maryland School of Medicine and Department of Pediatrics, and a Research Supplement for Underrepresented Minorities (RSUM) from NIH/NIAID (to M.F.P).

We thank J. Galen and J. Campbell for careful review of the manuscript.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, J. S., G. Dougan, and R. A. Strugnell. 2000. Kinetics of the mucosal antibody secreting cell response and evidence of specific lymphocyte migration to the lung after oral immunisation with attenuated S. enterica var. Typhimurium. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 27:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrios, C., P. Brawand, M. Berney, C. Brandt, P. H. Lambert, and C. A. Siegrist. 1996. Neonatal and early life immune responses to various forms of vaccine antigens qualitatively differ from adult responses: predominance of a Th2-biased pattern which persists after adult boosting. Eur. J. Immunol. 26:1489-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bot, A., and C. Bona. 2002. Genetic immunization of neonates. Microbes Infect. 4:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brazolot Millan, C. L., R. Weeratna, A. M. Krieg, C. A. Siegrist, and H. L. Davis. 1998. CpG DNA can induce strong Th1 humoral and cell-mediated immune responses against hepatitis B surface antigen in young mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15553-15558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capozzo, A. V. C., V. Pistone, G. Dran, G. Fernandez, S. Gomez, L. V. Bentancor, C. Rubel, C. Ibarra, M. Isturiz, and M. S. Palermo. 2003. Development of DNA vaccines against hemolytic-uremic syndrome in a murine model. Infect. Immun. 71:3971-3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dadaglio, G., C. M. Sun, R. Lo-Man, C. A. Siegrist, and C. Leclerc. 2002. Efficient in vivo priming of specific cytotoxic T cell responses by neonatal dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 168:2219-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberg, J. C., S. J. Czinn, C. A. Garhart, R. W. Redline, W. C. Bartholomae, J. M. Gottwein, J. G. Nedrud, S. E. Emancipator, B. B. Boehm, P. V. Lehmann, and T. G. Blanchard. 2003. Protective efficacy of anti-Helicobacter pylori immunity following systemic immunization of neonatal mice. Infect. Immun. 71:1820-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forsthuber, T., H. C. Yip, and P. V. Lehmann. 1996. Induction of TH1 and TH2 immunity in neonatal mice. Science 271:1728-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franchini, M., C. Abril, C. Schwerdel, C. Ruedl, M. Ackermann, and M. Suter. 2001. Protective T-cell-based immunity induced in neonatal mice by a single replicative cycle of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 75:83-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galen, J. E., O. G. Gomez-Duarte, G. A. Losonsky, J. L. Halpern, C. S. Lauderbaugh, S. Kaintuck, M. K. Reymann, and M. M. Levine. 1997. A murine model of intranasal immunization to assess the immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella typhi live vector vaccines in stimulating serum antibody responses to expressed foreign antigens. Vaccine 15:700-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galen, J. E., and M. M. Levine. 2001. Can a ′flawless' live vector vaccine strain be engineered? Trends Microbiol. 9:372-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gans, H. A., Y. Maldonado, L. L. Yasukawa, J. Beeler, S. Audet, M. M. Rinki, R. DeHovitz, and A. M. Arvin. 1999. IL-12, IFN-gamma, and T cell proliferation to measles in immunized infants. J. Immunol. 162:5569-5575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Duarte, O. G., J. Galen, S. N. Chatfield, R. Rappuoli, L. Eidels, and M. M. Levine. 1995. Expression of fragment C of tetanus toxin fused to a carboxyl-terminal fragment of diphtheria toxin in Salmonella typhi CVD 908 vaccine strain. Vaccine 13:1596-1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez, C., D. Hone, F. R. Noriega, C. O. Tacket, J. R. Davis, G. Losonsky, J. P. Nataro, S. Hoffman, A. Malik, and E. Nardin. 1994. Salmonella typhi vaccine strain CVD 908 expressing the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum: strain construction and safety and immunogenicity in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 169:927-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassett, D. E., J. Zhang, M. Slifka, and J. L. Whitton. 2000. Immune responses following neonatal DNA vaccination are long-lived, abundant, and qualitatively similar to those induced by conventional immunization. J. Virol. 74:2620-2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassett, D. E., J. Zhang, and J. L. Whitton. 1997. Neonatal DNA immunization with a plasmid encoding an internal viral protein is effective in the presence of maternal antibodies and protects against subsequent viral challenge. J. Virol. 71:7881-7888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishii, K. J., W. R. Weiss, and D. M. Klinman. 1999. Prevention of neonatal tolerance by a plasmid encoding granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor. Vaccine 18:703-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ismaili, J., M. van der Sande, M. J. Holland, I. Sambou, S. Keita, C. Allsopp, M. O. Ota, K. P. McAdam, and M. Pinder. 2003. Plasmodium falciparum infection of the placenta affects newborn immune responses. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 133:414-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, E., H. K. Law, and Y. L. Lau. 2003. BCG promotes cord blood monocyte-derived dendritic cell maturation with nuclear Rel-B up-regulation and cytosolic I kappa B alpha and beta degradation. Pediatr. Res. 54:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manickan, E., Z. Yu, and B. T. Rouse. 1997. DNA immunization of neonates induces immunity despite the presence of maternal antibody. J. Clin. Invest. 100:2371-2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall-Clarke, S., D. Reen, L. Tasker, and J. Hassan. 2000. Neonatal immunity: how well has it grown up? Immunol. Today 21:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez, X., C. Brandt, F. Saddallah, C. Tougne, C. Barrios, F. Wild, G. Dougan, P. H. Lambert, and C. A. Siegrist. 1997. DNA immunization circumvents deficient induction of T helper type 1 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in neonates and during early life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8726-8731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittrucker, H. W., and S. H. Kaufmann. 2000. Immune response to infection with Salmonella typhimurium in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 67:457-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morein, B., I. Abusugra, and G. Blomqvist. 2002. Immunity in neonates. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 87:207-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ota, M. O., J. Vekemans, S. E. Schlegel-Haueter, K. Fielding, M. Sanneh, M. Kidd, M. J. Newport, P. Aaby, H. Whittle, P. H. Lambert, K. P. McAdam, C. A. Siegrist, and A. Marchant. 2002. Influence of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin on antibody and cytokine responses to human neonatal vaccination. J. Immunol. 168:919-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasetti, M. F., E. M. Barry, G. A. Losonsky, M. Singh, S. M. Medina-Moreno, J. M. Polo, J. B. Ulmer, H. L. Robinson, M. B. Sztein, and M. M. Levine. 2003. Attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and Shigella flexneri 2A strains mucosally deliver DNA vaccines encoding measles virus hemagglutinin, inducing specific immune responses and protection in cotton rats. J. Virol. 77:5209-5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasetti, M. F., R. J. Anderson, F. R. Noriega, M. M. Levine, and M. B. Sztein. 1999. Attenuated ΔguaBA Salmonella typhi vaccine strain CVD 915 as a live vector utilizing prokaryotic or eukaryotic expression systems to deliver foreign antigens and elicit immune responses. Clin. Immunol. 92:76-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasetti, M. F., M. M. Levine, and M. B. Sztein. 2003. Animal models paving the way for clinical trials of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi live oral vaccines and live vectors. Vaccine 21:401-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasetti, M. F., T. E. Pickett, M. M. Levine, and M. B. Sztein. 2000. A comparison of immunogenicity and in vivo distribution of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and Typhimurium live vector vaccines delivered by mucosal routes in the murine model. Vaccine 18:3208-3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pickett, T. E., M. F. Pasetti, J. E. Galen, M. B. Sztein, and M. M. Levine. 2000. In vivo characterization of the murine intranasal model for assessing the immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strains as live mucosal vaccines and as live vectors. Infect. Immun. 68:205-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plant, A., R. Williams, M. E. Jackson, and N. A. Williams. 2003. The B subunit of Escherichia coli heat labile enterotoxin abrogates oral tolerance, promoting predominantly Th2-type immune responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 33:3186-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rayevskaya, M., N. Kushnir, and F. R. Frankel. 2002. Safety and immunogenicity in neonatal mice of a hyperattenuated Listeria vaccine directed against human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 76:918-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridge, J. P., E. J. Fuchs, and P. Matzinger. 1996. Neonatal tolerance revisited: turning on newborn T cells with dendritic cells. Science 271:1723-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts, M., S. Chatfield, D. Pickard, J. Li, and A. Bacon. 2000. Comparison of abilities of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA aroD and aroA htrA mutants to act as live vectors. Infect. Immun. 68:6041-6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts, M., J. Li, A. Bacon, and S. Chatfield. 1998. Oral vaccination against tetanus: comparison of the immunogenicities of Salmonella strains expressing fragment C from the nirB and htrA promoters. Infect. Immun. 66:3080-3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roduit, C., P. Bozzotti, N. Mielcarek, P. H. Lambert, G. Del Giudice, C. Locht, and C. A. Siegrist. 2002. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of neonatal vaccination against Bordetella pertussis in a murine model: evidence for early control of pertussis. Infect. Immun. 70:3521-3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowe, J., C. Macaubas, T. Monger, B. J. Holt, J. Harvey, J. T. Poolman, R. Loh, P. D. Sly, and P. G. Holt. 2001. Heterogeneity in diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine-specific cellular immunity during infancy: relationship to variations in the kinetics of postnatal maturation of systemic th1 function. J. Infect. Dis. 184:80-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salerno-Goncalves, R., T. L. Wyant, M. F. Pasetti, M. Fernandez-Vina, C. O. Tacket, M. M. Levine, and M. B. Sztein. 2003. Concomitant induction of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in volunteers immunized with Salmonella enterica serovar typhi strain CVD 908-htrA. J. Immunol. 170:2734-2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarzotti, M., D. S. Robbins, and P. M. Hoffman. 1996. Induction of protective CTL responses in newborn mice by a murine retrovirus. Science 271:1726-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sedegah, M., M. Belmonte, J. E. Epstein, C. A. Siegrist, W. R. Weiss, T. R. Jones, M. Lu, D. J. Carucci, and S. L. Hoffman. 2003. Successful induction of CD8 T cell-dependent protection against malaria by sequential immunization with DNA and recombinant poxvirus of neonatal mice born to immune mothers. J. Immunol. 171:3148-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shankar, G., L. A. Pestano, and M. L. Bosch. 2003. Interferon-gamma added during Bacillus Calmette-Guerin induced dendritic cell maturation stimulates potent Th1 immune responses. J. Transl. Med. 1:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegrist, C. A. 2001. Neonatal and early life vaccinology. Vaccine 19:3331-3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sirard, J. C., F. Niedergang, and J. P. Kraehenbuhl. 1999. Live attenuated Salmonella: a paradigm of mucosal vaccines. Immunol. Rev. 171:5-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sztein, M. B., S. S. Wasserman, C. O. Tacket, R. Edelman, D. Hone, A. A. Lindberg, and M. M. Levine. 1994. Cytokine production patterns and lymphoproliferative responses in volunteers orally immunized with attenuated vaccine strains of Salmonella typhi. J. Infect. Dis. 170:1508-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tacket, C. O., J. Galen, M. B. Sztein, G. Losonsky, T. L. Wyant, J. Nataro, S. S. Wasserman, R. Edelman, S. Chatfield, G. Dougan, and M. M. Levine. 2000. Safety and immune responses to attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar typhi oral live vector vaccines expressing tetanus toxin fragment C. Clin. Immunol. 97:146-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takeda, K., T. Kaisho, and S. Akira. 2003. Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:335-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van de Perre, P. 2003. Transfer of antibody via mother's milk. Vaccine 21:3374-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vollstedt, S., M. Franchini, H. P. Hefti, B. Odermatt, M. O'Keeffe, G. Alber, B. Glanzmann, M. Riesen, M. Ackermann, and M. Suter. 2003. Flt3 ligand-treated neonatal mice have increased innate immunity against intracellular pathogens and efficiently control virus infections. J. Exp. Med. 197:575-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, H. Y., E. B. Nikolova, K. W. Beagley, J. H. Eldridge, and M. W. Russell. 1997. Development of antibody-secreting cells and antigen-specific T cells in cervical lymph nodes after intranasal immunization. Infect. Immun. 65:227-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiang, Z., Y. Li, G. Gao, J. M. Wilson, and H. C. Ertl. 2003. Mucosally delivered E1-deleted adenoviral vaccine carriers induce transgene product-specific antibody responses in neonatal mice. J. Immunol. 171:4287-4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, J., N. Silvestri, J. L. Whitton, and D. E. Hassett. 2002. Neonates mount robust and protective adult-like CD8+-T-cell responses to DNA vaccines. J. Virol. 76:11911-11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]