Abstract

The current ethical dilemmas met by healthcare professionals were never compared with those 15 years ago when the palliative care system was newly developing in Taiwan.

The aim of the study was to investigate the ethical dilemmas met by palliative care physicians and nurses in 2013 and compare the results with the survey in 1998.

This cross-sectional study surveyed 213 physicians and nurses recruited from 9 representative palliative care units across Taiwan in 2013. The compared survey in 1998 studied 102 physicians and nurses from the same palliative care units. All participants took a questionnaire to survey the “frequency” and “difficulty” of 20 frequently encountered ethical dilemmas, which were grouped into 4 domains by factor analysis. The “ethical dilemma” scores were calculated and then compared across 15 years by Student's t tests. A general linear model analysis was used to identify significant factors relating to a high average “ethical dilemma” score in each domain.

All of the highest-ranking ethical dilemmas in 2013 were related to insufficient resources. Physicians with less clinical experience had a higher average “ethical dilemma” score in clinical management. Physicians with dissatisfaction in providing palliative care were associated a higher average “ethical dilemma” score in communication. Nurses reported higher “ethical dilemma” scores in all items of resource allocation in 2013. Further analysis confirmed that, in 2013, nurses had a higher average “ethical dilemma” score in resource allocation after adjustment for other relating factors.

Palliative care nursing staff in Taiwan are more troubled by ethical dilemmas related to insufficient resources than they were 15 years ago. Training of decision making in nurses under the framework of ethical principles and community palliative care programs may improve the problems. To promote the dignity of terminal cancer patients, long-term fundraising plans are recommended for countries in which the palliative care system is in its early stages of development.

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care relieves the suffering of terminally ill patients and provides them with physical, psychosocial, and spiritual care. It has been recognized as an essential part of cancer care by World Health Organization.1 As cancer has been ranked the highest among the top 10 leading causes of Taiwanese death in 1983, the number of cancer patients has continued to rise. In order to reduce the suffering of terminal cancer patients, Taiwan followed the footsteps of other countries and set up a palliative care system in the early 1990s. After decades of effort, the Economist Intelligence Unit ranked Taiwan's Quality of Death Index first in Asia and sixth in the world in 2015.2 However, our pursuit of high-quality end-of-life care may inevitably be hindered by ethical dilemmas in daily practice.3

The most frequently encountered ethical dilemmas and difficult decisions in palliative care, as previously reported by studies conducted in United Kingdom4 and the United States,5 included truth telling, survival prediction, side effects of pain control by morphine, treatment of abnormal biochemistry level in blood, and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment such as antibiotics. Despite different cultural background, a pilot study in Taiwan showed that place of care, truth telling, hydration and nutrition were the top 3 dilemmas that troubled terminal cancer patients. Some dilemmas remain unresolved even in the last week of hospitalization.6 Continuous communication is important in good decision-making processes among patients, families, and medical teams.

To understand the ethical dilemmas faced by healthcare professionals in palliative care units 15 years ago, our team conducted a nationwide survey in 1998 (Chinese version only). The results demonstrated that “frustration in guiding the desperate patients,” “families’ refusal to leave the hospital,” and “families concealing the truth from the patients” were ranked the most difficult issues. Fifteen years later, new challenges have arisen with the rapid growth of palliative care in Taiwan. Therefore, in 2013, we investigated the ethical dilemmas encountered by current nationwide palliative care teams. The comparison between the surveys serves as a valuable lesson to countries attempting to build a sustainable palliative care system.

METHODS

Design

This Study is a Cross-Sectional Survey Using the Clustering Sampling Method

A well-structured questionnaire, including informed consent, was sent to potential respondents from August 2012 to March 2013. The return and completion of the questionnaire were regarded as an agreement of participation.

Subjects

The study subjects included healthcare professionals (physicians and nurses) recruited from 9 representative palliative care units across Taiwan. All of them are experienced in actively providing care to terminal cancer patients under Taiwanese National Health Insurance System. These units were established before 1998 and met the standards set by Department of Health. The study design and subject selection were approved by the National Science Council in Taiwan.

Questionnaire

All participants completed the 2-part questionnaire, which contained questions on demographics and frequently encountered ethical dilemmas. The questionnaire was devised after a careful analysis of the literature in this field by a panel of 5 healthcare experts including physicians, a nursing supervisor, and senior nurses. Jury's opinions of the panel helped to determine the content validity of the questionnaire. Each item was evaluated on a scale of 1 (low) to 5 (high) for applicability and relevance to clinical practice. Only items with a rating of at least 4 and with a standard deviation <1 were adopted. The final questionnaire had 20 questions, and Cronbach's coefficient was 0.898.

The demographic characteristics included gender (men or women), age, current workplace (palliative care unit or shared-care team), profession (physician or nurse), clinical experience in palliative care (<1 year, 1–5 years, or >5 years), number of terminal patients cared in the past 3 years (<100 patients or >100 patients), religion (not-specified, Christianity, Catholicism, Taoism, Buddhism, or other), and satisfaction with providing palliative care in the past 3 years (very dissatisfied, dissatisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, satisfied, or very satisfied).

The main body of the questionnaire surveyed the “frequency” and the “difficulty” of the frequently encountered ethical dilemmas perceived by healthcare professionals. In our study, the scoring system for the “frequency scale” was a 5-point Likert Scale that ranged from “never encountered” (0) to “at least once per week” (4). The “difficulty scale” ranged from “not at all” (1) to “extremely difficult” (5). Bartlett's test of sphericity for the “frequency scale” was 2914.04, the significant value was <0.01, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure was 0.88. The scale was therefore suitable for exploratory factor analysis.

We analyzed the 20 questions using principal component factor analysis followed by orthogonal varimax rotation. Four factors with eigenvalues >1 were extracted. The measures of ethical dilemmas were reconstructed accordingly into 4 domains: “goal of care,” “clinical management,” “communication,” and “resource allocation.” Internal consistency of the “frequency scale” in the 4 domains was demonstrated with Cronbach coefficients of 0.82, 0.81, 0.88, and 0.73. The Cronbach coefficients of the “difficulty scale” in the 4 domains were 0.75, 0.75, 0.85, and 0.72.

To look into the frequently encountered ethical dilemmas 15 years ago, a previous study was conducted in 1998. The questionnaire used in the previous study was also devised by a panel of 5 healthcare experts through the same process and was then distributed to potential responders from August 1998 to July 1999. It comprised 39 questions with a Cronbach's coefficient of 0.92. To examine the changes of ethical dilemmas in palliative care, we compared the results of the same 20 questions in the current survey and the survey in 1998.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software version 16.0.2 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for the statistical analyses. Frequency and chi-square tests were used to describe the distribution of each variable in demographic characteristics. The scores of the “frequency scale” and the “difficulty scale” in each item were multiplied to obtain an “ethical dilemma” score. The average “ethical dilemma” score was calculated by multiplying the average scores of the “frequency scale” and the “difficulty scale” in each domain. Student's t tests were adopted to compare the “ethical dilemma” scores in different years. A general linear model analysis was conducted to identify significant factors relating to a high average “ethical dilemma” score. The relating factors used were the demographic characteristics including year of the survey, gender, religion, current workplace, clinical experience in palliative care, number of terminal patients cared in the past 3 years, and satisfaction with providing palliative care in the past 3 years. The statistical significance was set at a P value <0.05.

RESULTS

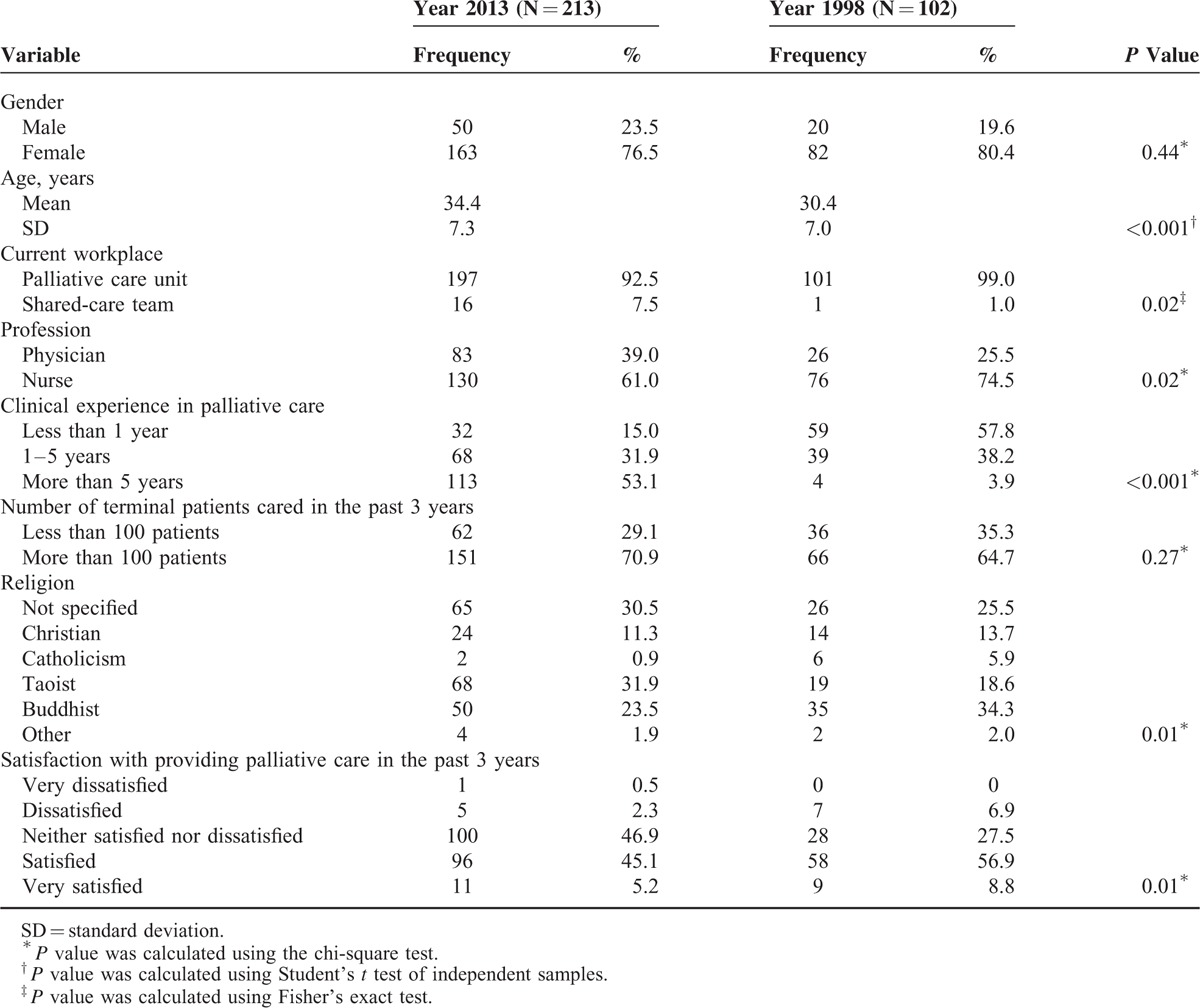

After excluding duplicate names, 213 healthcare professionals were enrolled into the final analysis in 2013. The response rate was 72.9% in the current survey. In 1998, 102 healthcare professionals took part in the survey, and the response rate was 88.0%. In comparison with the survey in 1998, healthcare professionals in 2013 were significantly older and had more clinical experience. The participants’ background information and demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Data of the Healthcare Professionals

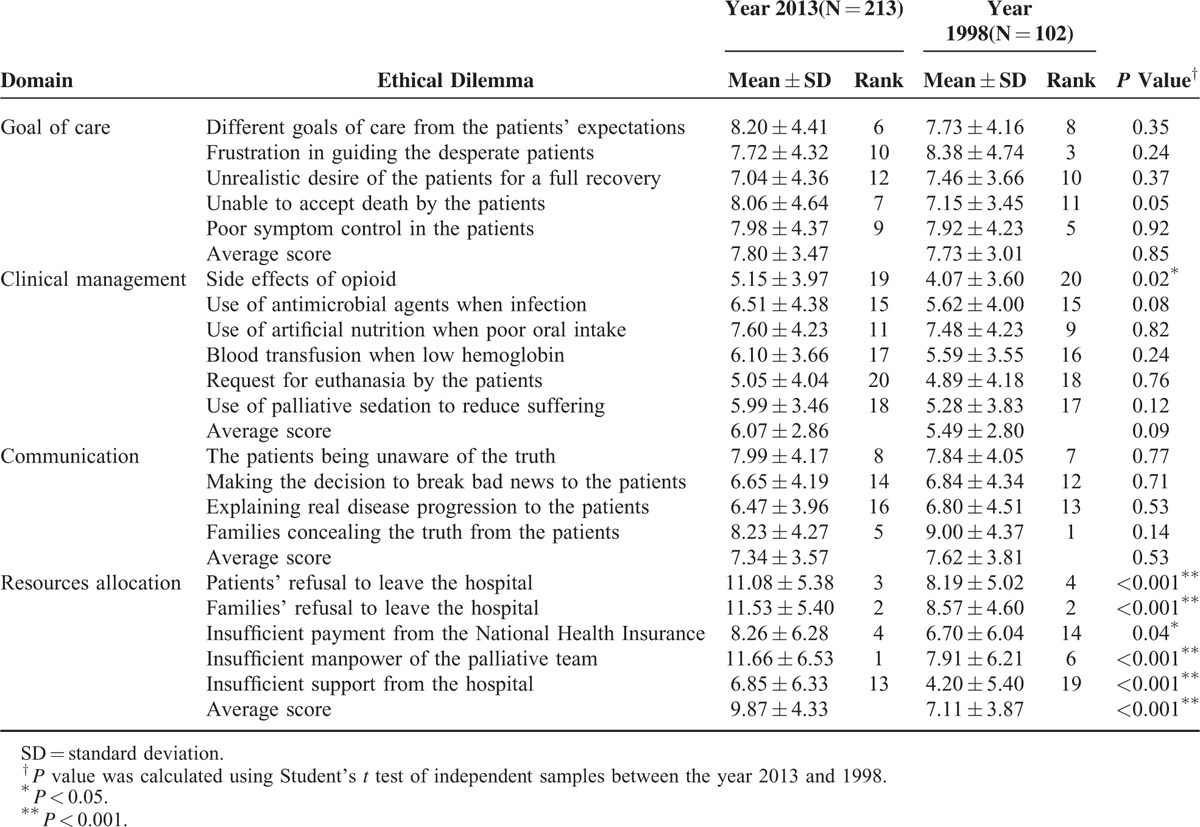

Table 2 compares the “ethical dilemma” scores in 2013 and in 1998. The mean, standard deviation, and rank of each ethical dilemma are listed. The top 3 ethical dilemmas in 1998 were “families concealing the truth from the patients” (9.00 ± 4.37), “families’ refusal to leave the hospital” (8.57 ± 4.60), and “frustration in guiding the desperate patients” (8.38 ± 4.74). These 3 ethical dilemmas were distributed in the domains of communication, resources allocation, and goal of care, respectively. However, the top 3 ethical dilemmas in 2013 centered on resource allocation. They were “insufficient manpower of the palliative care team” (11.66 ± 6.53), “families’ refusal to leave the hospital” (11.53 ± 5.40), and “patients’ refusal to leave the hospital” (11.08 ± 5.38). Additionally, the scores of all 5 ethical dilemmas in the domain of resource allocation were significantly higher in 2013 than in 1998. Interestingly, the score of “side effects of opioid” in 2013 was significantly higher than it was 15 years ago (5.15 ± 3.97 vs 4.07 ± 3.60, P value: 0.02). This might reflect the inappropriate use of opioid in general wards during recent years, which made pain relief after transferring to palliative care units more difficult than before.

TABLE 2.

The “Ethical Dilemma” Scores in the Year 2013 and 1998

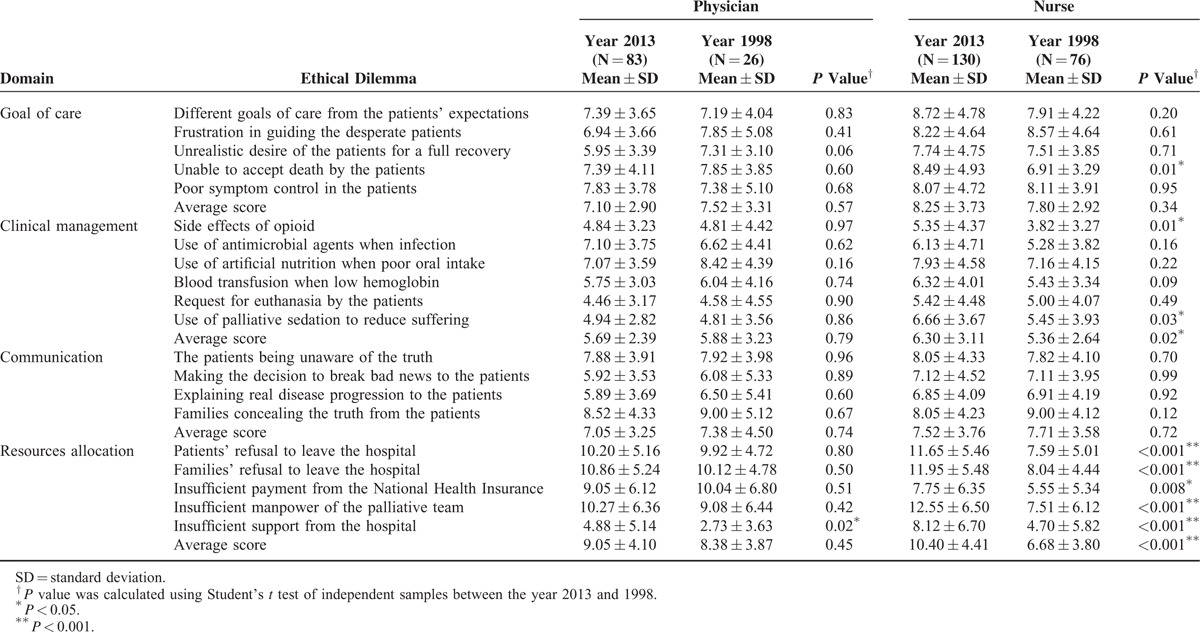

Table 3 compares the physicians’ and nurses’ “ethical dilemma” scores categorized by the different years of the survey. In physicians, only the score of “insufficient support from the hospital” was significantly higher in 2013 (4.88 ± 5.14 vs 2.73 ± 3.63, P value: 0.02). However, several “ethical dilemma” scores rated by nurses were significantly higher in 2013, including all 5 ethical dilemmas and the average score in the domain of resource allocation. Nurses also had a significantly higher average “ethical dilemma” score in 2013 in the domain of clinical management (6.30 ± 3.11 vs 5.36 ± 2.64, P value: 0.02).

TABLE 3.

The Physicians’ and Nurses’ “Ethical Dilemma” Scores Categorized by the Different Years of the Survey

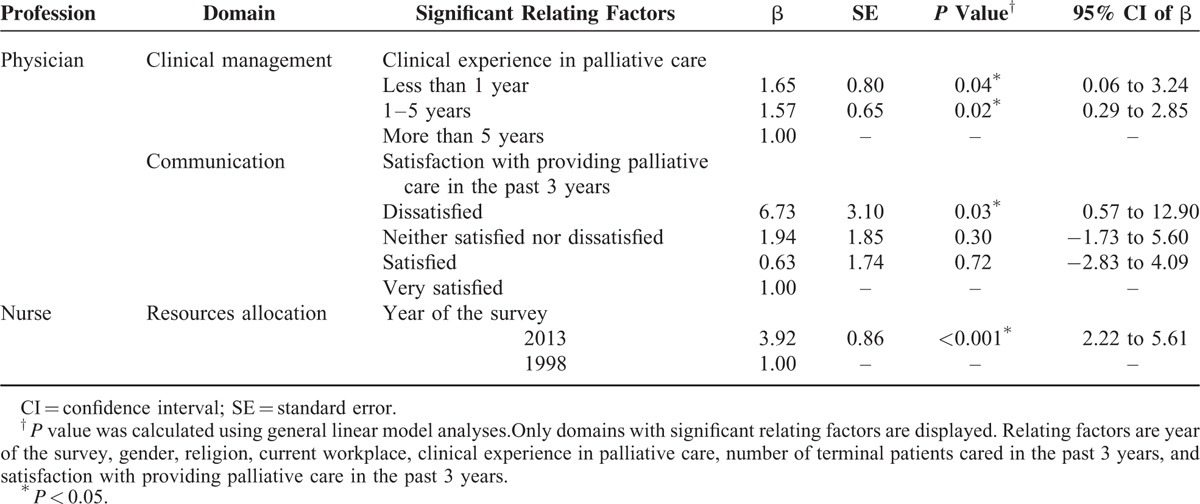

Table 4 reveals the results of general linear model analysis. Only the domains with significant relating factors are displayed. In the submodels of physicians, less clinical experience in palliative care was significantly related to a higher average “ethical dilemma” score in clinical management (β: 1.65, 95% CI: 0.06–3.24). Physicians who were dissatisfied with providing palliative care in the past 3 years also had a higher average “ethical dilemma” score in communication (β: 6.73, 95% CI: 0.57–12.90). Further analysis confirmed that nurses in 2013 reported a higher average “ethical dilemma” score in resource allocation after adjustment for other relating factors (β: 3.92, 95% CI: 2.22–5.61).

TABLE 4.

Significant Relating Factors Associated With a High Average “Ethical Dilemma” Score in Respective Domains

DISCUSSION

This study is the first nationwide investigation to compare the ethical dilemmas encountered by healthcare professionals in different stages of palliative care system development. Though our palliative care staff were more experienced in 2013 than they had been in 1998, they were facing more problems related to resource shortages than they had been 15 years earlier. Our findings showed that insufficient resources had become a main cause of ethical dilemmas in palliative care, and this is a major drawback for the continuous development of a sound palliative care system. Furthermore, nurses perceived the insufficiency of resources more than physicians did, which highlighted the difficulties met by first-line nursing staff. As palliative care has been viewed as an international human right,7 our findings may have important implications to providing better end-of-life care under current resource constraints.

Because nurses are direct responders who address the pain and suffering of terminal cancer patients, the quality of nursing is an important factor in patient's satisfaction.8 The challenges of being emotionally affected and having negative thoughts inevitably arise with a heavy workload.9 Working to satisfy the needs of every terminal patient also places nurses at high risk of professional compassion fatigue.10 The anxiety of patients and families further increases nurses’ stress, particularly when all available treatments have been applied in vain.9 In Taiwan, the quality of palliative care is worsened by insufficient manpower and the low salary of palliative care workers, which may lead nurses to question their career choice and ultimately quit their job. To address the problem of insufficient manpower, efforts should be directed to training in ethics and sharing nurses’ workload. As Ablett et al noted, nurses who were willing to keep their career in palliative care found their job meaningful.11 Thus, the training of decision making under the framework of ethical principles may be incorporated into nursing school curricula to strengthen nurses’ faith in palliative clinical management.12 Increasing the number of palliative care team members other than nurses (for example, psychologists, religion specialists, and voluntary workers) also helps more nurses to choose palliative care as a career option.

Regarding the dilemma of “patients’ and families’ refusal to leave the hospital”, it might seem that Taiwanese terminal cancer patients prefer to die at the hospital, but the truth is the opposite. In fact, dying at home implies a good death, according to Taiwanese culture, and a home death has been advocated in recent years.13 However, people want to stay in the hospital because the hospital offers better quality care, they are unable to manage emergent medical conditions at home, and they have an insufficient number of family caregivers.14 To respect terminal cancer patients’ preference for place of death, we propose better community palliative care programs with effective referral systems.15,16 Evidence suggests that such programs account for a higher quality of life and reduced hospitalizations.17,18 With the continuity of care provided by family physicians, the use of acute medical resources can be reduced at the end of life.19 Home visits to cancer patients by general practitioners also allow for the choice of a home death.20 This is an important step to respect the autonomy of those who desire to spend their last days at home.

Since Taiwan started a National Health Insurance (NHI) system in 1995, the comprehensive coverage of NHI has increased life expectancy,21 but the length of hospital stay and medical costs have also increased. A lot of “futile treatment” is administered to patients with multiorgan failure in their final days. However, discontinuation of futile treatment is ethically acceptable if the treatment may be harmful to the terminal patients.22 Palliative care has also been proved to save medial expenditure both in the United States and Taiwan.23,24 Thus, we promote palliative care to raise the quality of end-of-life care without increasing medical costs. This is particularly important because Taiwan is an ageing society with insufficient medical resources in the near future. Given the circumstances, directing medial resources from futile treatment to palliative care fits the distributive justice. We also suggest that long-term fundraising plans should be initiated as early as possible to build a sustainable palliative care system.

The major strength of our study is the comparison of ethical dilemmas >15 years, which corresponds to the period when palliative care became an indispensable part of cancer care in Taiwan. Thus, the lessons learned are valuable to countries with a developing palliative care system. The response rate was fairly high (72.9% in the present survey and 88.0% in the previous survey). The findings of prominent resource shortages perceived more by nurses today were found in 2 different statistical analyses, which made our results more reliable.

Our study was limited by the questionnaire-based surveys, which were subject to recall bias; however, the questionnaire was answered by first-line healthcare professionals whose responses provided the most accurate pictures of the ethical dilemmas encountered in daily practice. Because Buddhism and Taoism are the main religions in Taiwan, the findings in our study should be applied with cautions to countries with other predominant religions. We did not incorporate the measurement of medical knowledge into our questionnaire; thus we could not discuss the “ethical dilemma” scores caused by different medical knowledge levels between physicians and nurses. Our future studies should investigate the impact of medical knowledge on the ethical dilemmas encountered.

In conclusion, palliative care nursing staff in Taiwan are more troubled by ethical dilemmas related to insufficient resources than they were 15 years ago. We propose training of decision making in nurses under the framework of ethical principles and better community palliative care programs to improve the problems. To promote the dignity of terminal cancer patients, long-term fundraising plans are recommended for countries in which the palliative care system is in its early stages of development.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the physicians and nurses who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Funding: this study was supported by grants (NSC 102-2314-B-002-147-MY3) from the National Science Council in Taiwan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, et al. Palliative care: the World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002; 24:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray S. The 2015 Quality of Death Index: Ranking palliative care across the world. The Economist Intelligence Unit 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiu TY, Hu WY, Huang HL, et al. Prevailing ethical dilemmas in terminal care for patients with cancer in Taiwan. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:3964–3968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlay I. Difficult decisions in palliative care. Br J Hosp Med 1996; 56:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinzbrunner BM. Ethical dilemmas in hospice and palliative care. Support Care Cancer 1995; 3:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiu TY, Hu WY, Cheng SY, et al. Ethical dilemmas in palliative care: a study in Taiwan. J Med Ethics 2000; 26:353–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gwyther L, Brennan F, Harding R. Advancing palliative care as a human right. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 38:767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park CH, Shin DW, Choi JY, et al. Determinants of family satisfaction with inpatient palliative care in Korea. J Palliat Care 2013; 29:91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu HL, Volker DL. Living with death and dying: the experience of Taiwanese hospice nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum 2009; 36:578–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melvin CS. Professional compassion fatigue: what is the true cost of nurses caring for the dying? Int J Palliat Nurs 2012; 18:606–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ablett JR, Jones RS. Resilience and well-being in palliative care staff: a qualitative study of hospice nurses’ experience of work. Psychooncology 2007; 16:733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ke LS, Chiu TY, Hu WY, et al. Effects of educational intervention on nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward supplying artificial nutrition and hydration to terminal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2008; 16:1265–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin HC, Lin CC. A population-based study on the specific locations of cancer deaths in Taiwan, 1997–2003. Support Care Cancer 2007; 15:1333–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu WY, Chiu TY, Cheng YR, et al. Why Taiwanese hospice patients want to stay in hospital: health-care professionals’ beliefs and solutions. Support Care Cancer 2004; 12:285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao CA, Hu WY, Lai YF, et al. Does dying at home influence the good death of terminal cancer patients? J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 34:497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munday D, Dale J. Palliative care in the community. BMJ 2007; 334:809–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:4457–4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso-Babarro A, Astray-Mochales J, Domínguez-Berjón F, et al. The association between in-patient death, utilization of hospital resources and availability of palliative home care for cancer patients. Palliat Med 2013; 27:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almaawiy U, Pond GR, Sussman J, et al. Are family physician visits and continuity of care associated with acute care use at end-of-life? A population-based cohort study of homecare cancer patients. Palliat Med 2014; 28:176–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng JK, Hu WY, Hung SH, et al. What can family physicians contribute in palliative home care in Taiwan? Fam Pract 2009; 26:287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen CP, Tsai SP, Chung WS. A 10-year experience with universal health insurance in Taiwan: measuring changes in health and health disparity. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148:258–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chih AH, Lee LT, Cheng SY, et al. Is it appropriate to withdraw antibiotics in terminal patients with cancer with infection? J Palliat Med 2013; 16:1417–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pyenson B, Connor S, Fitch K, et al. Medicare cost in matched hospice and non-hospice cohorts. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004; 28:200–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin WY, Chiu TY, Hsu HS, et al. Medical expenditure and family satisfaction between hospice and general care in terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2009; 108:794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]