Abstract

Inhibition of centromere-associated protein-E (CENP-E) has demonstrated preclinical anti-tumor activity in a number of tumor types including neuroblastoma. A potent small molecule inhibitor of the kinesin motor activity of CENP-E has recently been developed (GSK923295). To identify an effective drug combination strategy for GSK923295 in neuroblastoma, we performed a screen of siRNAs targeting a prioritized set of genes that function in therapeutically tractable signaling pathways. We found that siRNAs targeted to extracellular signal-related kinase 1 (ERK1) significantly sensitized neuroblastoma cells to GSK923295-induced growth inhibition (p = 0.01). Inhibition of ERK1 activity using pharmacologic inhibitors of mitogen-activated ERK kinase (MEK1/2) showed significant synergistic growth inhibitory activity when combined with GSK923295 in neuroblastoma, lung, pancreatic and colon carcinoma cell lines. Synergistic growth inhibitory activity of combined MEK/ERK and CENP-E inhibition was a result of increased mitotic arrest and apoptosis. There was a significant correlation between ERK1/2 phosphorylation status in neuroblastoma cell lines and GSK923295 growth inhibitory activity (r = 0.823, p = 0.0006). Consistent with this result we found that lung cancer cell lines harboring RAS mutations, which leads to oncogenic activation of MEK/ERK signaling, were significantly more resistant than cell lines with wild-type RAS to GSK923295-induced growth inhibition (p = 0.047). Here we have identified (MEK/ERK) activity as a potential biomarker of relative GSK923295 sensitivity and have shown the synergistic effect of combinatorial MEK/ERK pathway and CENP-E inhibition across different cancer cell types including neuroblastoma.

Keywords: CENP-E, GSK923295, ERK, MEK, neuroblastoma, Ras

Centromere-associated protein-E (CENP-E) is a kinesin motor protein involved in the attachment of chromosomes to mitotic spindle microtubules.1 CENP-E plays a critical role in regulating the mitotic checkpoint by ensuring proper chromosome alignment prior to the transition from metaphase to anaphase.2 Inhibition of CENP-E using dominant-negative proteins, siRNA or antibodies leads to a prolonged mitotic arrest in cells that is often accompanied by the presence of lagging and misaligned chromosomes at the metaphase plate.3–5 GSK923295 was recently discovered as a potent and selective small molecule inhibitor of the ATPase activity of human CENP-E. GSK923295 had broad growth inhibitory activity in a panel of 237 cancer cell lines and produced significant tumor growth-delay in 8 of the 11 mouse xenograft tumor models that were tested.6

We have previously reported the discovery of CENP-E as a promising therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. CENP-E was identified as a candidate target through a cross-species integrative genomics analysis of tumor progression in transgenic TH-MYCN mice and human tumors with MYCN amplification.7 Target validation studies demonstrated significant growth inhibitory activity of CENP-E-targeted siRNA and GSK923295 in a panel of neuroblastoma cell lines.7 GSK923295 also caused significant growth delay in mice harboring xenograft tumors of three different neuroblastoma cell lines.7

A number of next-generation anti-mitotic compounds are already in clinical trials for various tumor types. Most notable are agents targeting the Aurora kinases A and B as well as inhibitors of Polo-like Kinase 1 (PLK1).8 Clinical responses have been achieved in certain tumor types; however, dose-limiting toxicities have also been observed, sometimes at or below the effective dose level.9 To maximize the clinical utility of these next-generation anti-mitotic drugs and perhaps also circumvent mechanisms for acquired resistance, rational and synergistic drug combinations must be developed. Here, we have performed preclinical proof-of-principle studies to establish an efficacious drug combination strategy for the small molecule CENP-E inhibitor, GSK923295. We tested GSK923295 in combination with a standard neuroblastoma chemotherapeutic regimen of irinotecan and temozolomide in vitro to establish its potential benefit in the relapse setting. We also performed a screen to identify which emerging molecularly targeted drugs may be most beneficial when used in combination with CENP-E inhibitors moving forward. The data from these studies could be used as a basis for the clinical development of GSK923295 or other CENP-E inhibitors in neuroblastoma and other cancers.

Material and Methods

siRNA transfection

Twenty-four hours after seeding in 96-well plates, neuroblastoma cells were transfected with gene target-specific SMARTpool siRNA (Dharmacon, Thermo Scientific, Chicago, IL) at a final concentration of 75 nM using DharmaFECT1 lipofection reagent (Dharmacon, Thermo Scientific, Chicago, IL). Non-targeted control (NTC) and Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) targeted siRNA were used as negative controls. Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection, cells were treated with GSK923295 and cell growth was then followed for an additional 72 hr. Real-time cell proliferation was measured using the RT-CES system (ACEA Biosciences, Roche, San Diego, CA).

Western blotting

Cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and lysed directly into 1× cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Antibodies for extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK1/2) and phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (E10) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) were diluted 1:1,000 in 5% non-fat dry milk. Protein band densitometry of Western blots was performed using Photoshop software (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Real-time PCR analysis

Total cellular RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed with pre-designed TaqMan gene expression assay for ERK1/mitogen-activated protein kinase-3 (MAPK3) (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, California). Relative target gene mRNA expression was determined by normalization to β-actin expression.

Flow cytometry Sub-G1 analysis

At each specified timepoint following drug treatment the media was removed and cells were washed in cold PBS and detached using 0.05% trypsin-Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Media and trypsin fractions were combined and spun. Cells were fixed overnight with ice cold 95% ethanol then permeabilized using phosphate-citric acid buffer (0.2M Na2HPO4 + 0.1M citric acid, pH 7.8). Cells were spun and resuspended in propidium iodide (50 μg/mL) and RNase A (250 μg/mL) for 30 min and analyzed by flow cytometry using an LSR-II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California). The percentage of cells with Sub-G1 DNA content was quantified using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Flow cytometry phospho-Histone H3 analysis

Cells and media were collected and spun. Pellets were resuspended into 3% formaldehyde for 10 min at 37°C then chilled on ice. To permeabilize membranes cells were pelleted and resuspended in 90% methanol at −20°C overnight. Tubes were spun and cells were washed with 3 mL of 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Cells were incubated with phospho-Histone H3 (Ser10) antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) diluted 1:1,600 in 0.5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature followed by anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 Conjugate IgG diluted (1:1,000) in 0.5% BSA for an additional 30 min at room temperature. Cells were spun and resuspended in propidium iodide (50 μg/mL) and RNase A (250 μg/mL) for 30 min and analyzed by flow cytometry using an LSR-II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California).

Quantification of cell viability and apoptosis

Cells were seeded at appropriate seeding densities estimated from previous studies of each cell line into 384-well black-sided clear-bottom plates. Seventy-two hours after drug treatment cell viability was quantified in triplicate with CellTiter Glo reagent (Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA) using a GloMax multi detection system (Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA). For apoptosis detection cells were plated into 96-well plates. Twenty-four hours after drug treatment apoptosis was quantified in triplicate with Caspase-3/7 Glo reagent (Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA) and normalized for cell density using CellTiter Glo.

Quantification of drug synergy

Evaluation of synergy was determined using CalcuSyn Software (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom) which uses the combination index (CI) equation based on the multiple drug-effect equation derived by Chou and Talalay.

Isobolograms were generated at two dose effect levels ED50 and ED75. Values for fraction of cells affected (fa) were calculated by using the mean of triplicate CellTiterGlo measurements at each corresponding dose. Any (fa) values ≤ 0 or = 1 were adjusted to 0.001 and 0.99, respectively, to allow for CI calculation. The goodness of fit for the data to the median-effect equation is represented by the linear correlation coefficient (r) of the median-effect plot.

Statistical analysis

Significance was determined using the Student’s t-test assuming unequal variance (heteroscedastic t-test) in the Prism v5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA). All p values below 0.05 were considered significant. Dose response curves in Figure 1c were analyzed for significance using a two-way ANOVA and the Bonferroni multiple comparison test which showed significance for the interaction between both treatments with a p value of 0.0003

Figure 1.

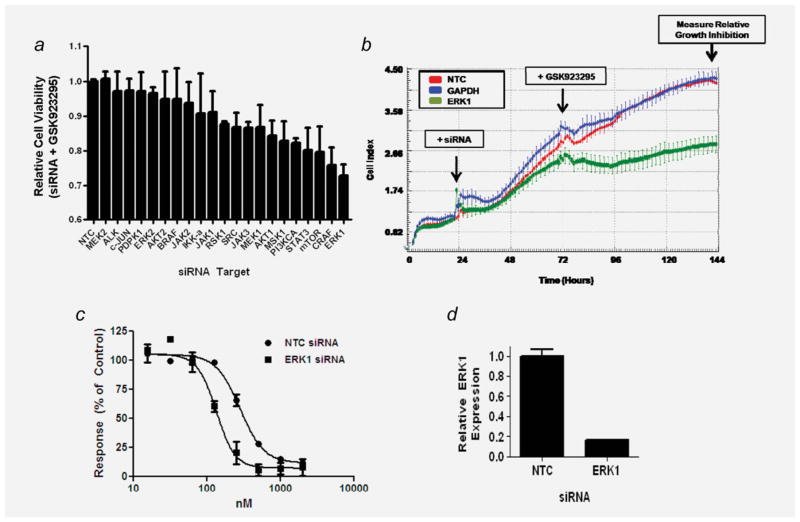

A siRNA screen identifies gene targets that sensitize neuroblastoma cells to GSK923295. (a) Relative growth inhibition of target-specific pooled siRNA (75 nM) when combined with GSK923295 (125 nM) in SK-N-FI cells. Relative growth is normalized to the cell index at 72 hr to eliminate the growth inhibitory effects of siRNA treatment alone. Bars represent mean relative viability ± (S.E.M.). (b) Real-time growth curves of SK-N-FI cells treated with pooled siRNAs (75 nM) targeted to ERK1, with intervention/read-out time points noted. Cells were significantly more sensitive to GSK923295 (125 nM) than treatment with non-targeting control (NTC) or GAPDH siRNA (p < 0.0001). (c) SK-N-FI cells treated with a dose range of GSK923295 after transfection with NTC or ERK1 siRNA (75 nM). (d) Relative ERK1 mRNA expression 48 hr after siRNA transfection normalized to β-actin expression.

Results

Inhibition of ERK1 significantly sensitizes neuroblastoma cells to GSK923295

We sought to identify novel molecular drug combinations that may strongly synergize with GSK923295 in neuroblastoma. We first performed studies assessing its combinatorial activity with irinotecan and temozolomide, two drugs commonly used for patients with progressive disease following induction therapy.10,11 For combinatorial analysis we selected two cell lines (NB-1691 and SK-N-FI) that were the least sensitive to single agent GSK923295 from our panel of 19 neuroblastoma lines.7 The triple combination of GSK923295, temozolomide and SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan, was administered concurrently in both resistant cell lines. The triple combination was moderately synergistic in NB-1691 cells and ranged from moderately synergistic to additive at higher doses in SK-N-FI cells as compared to single agent treatments (Supporting Information Fig. 1 and Supporting Information Table 1). However, in both cell lines the three drug combination of SN-38/Temozolomide/GSK923295 was not significantly more effective than the two drug combination of SN-38 and temozolomide (Supporting Information Fig. 1). In addition, the two drug combination of GSK923295 and SN-38 demonstrated moderate antagonism in SK-N-FI cells (Supporting Information Table 1).

In order to identify more optimal molecular drug targets for combination with GSK923295, we performed a screen of siRNAs targeted to 21 genes that function in therapeutically tractable signaling pathways (Fig. 1a). The siRNA pool targeted to ERK1 resulted in the most significant increase in GSK923295-mediated growth arrest as compared to NTC or GAPDH siRNA (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1b). We confirmed the sensitizing effect of ERK1 siRNA using an expanded dose range of GSK923295 (15.6 nM–2,000 nM) in SK-N-FI cells. Cells pretreated with ERK1 siRNA had a 2.1-fold decrease (134 nM vs. 283 nM) in the IC50 of GSK923295 (p = 0.0003; Fig. 1c). Treatment with ERK1 siRNA resulted in a greater than 80% reduction in ERK1 mRNA at the time of GSK923295 treatment (Fig. 1d).

Pharmacologic MEK/ERK inhibition sensitizes neuroblastoma cells to GSK923295-induced cell death

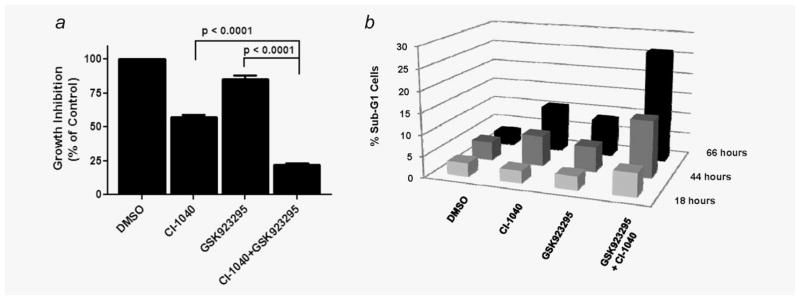

To achieve pharmacologic ERK1 inhibition in neuroblastoma cells we used a small molecule inhibitor of mitogen-activated ERK kinase-1/2 (MEK1/2) (CI-1040/PD184352). Three neuroblastoma cells lines (SK-N-FI, NB-1691 and NB-1771) were treated with a fixed-ratio (1:0.64) combination of CI-1040 and GSK923295. This ratio was chosen to align the approximate effective single agent concentrations for each drug. Cells were concurrently treated with a nine-point dose range of CI-1040 in 2-fold dilutions from (0.6 nM–25,000 nM) and GSK923295 from (0.4 nM–16,000 nM). The combination of CI-1040 and GSK923295 was synergistic in all three neuroblastoma cell lines tested (Table 1). We also performed a sequential combination of CI-1040 and GSK923295 in SK-N-FI cells to more closely recapitulate the design of the ERK1 siRNA and GSK923295 combination experiment. The sequential combination of CI-1040 and GSK923295 was moderately synergistic (Table 1) and resulted in significantly more growth inhibition and an increase in cell death as compared to both single agent treatments (p < 0.0001) in SK-N-FI cells (Figs. 2a and 2b). The increased cell death caused by GSK923295/CI-1040 combination was associated with an increase in the accumulation of cells in G2/M phase at 18 hr after treatment (Supporting Information Fig. 2).

Table 1.

The combination of CI-1040 and GSK923295 has synergistic activity in neuroblastoma cells

| 1 C.I. values at | 2r | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ED50 | ED75 | ||

| GSK923295/CI-1040 (Concurrent) | |||

| NB-1691 | 0.25577 | 0.30817 | 0.82963 |

| NB-1771 | 0.13599 | 0.11783 | 0.89631 |

| SKNFI | 0.64344 | 0.37958 | 0.95194 |

| GSK923295/CI-1040 (Sequential) | |||

| SKNFI | 0.83404 | 0.75683 | 0.97991 |

| Range of C.I. | Effect | ||

| < 0.3 | Strong Synergism | ||

| 0.3–0.7 | Synergism | ||

| 0.7–0.9 | Moderate Synergism | ||

| 0.9–1.10 | Additive | ||

| > 1.10 | Antagonistic | ||

Combination index (C.I.) values are listed for the 50% and 75% Effective Dose (ED50 and ED75) in each cell line.

r-values represent the linear correlation coefficient for the median-effect plot.

Figure 2.

Pharmacologic MEK/ERK inhibition sensitizes neuroblastoma cells GSK923295. (a) Combined CI-1040 (1.25 μM) and GSK923295 (125 nM) treatment for 72 hr results in significantly more growth inhibition than treatment with either agent alone (p <0.001) Bars represent mean % viability relative to DMSO control ± (S.E.M.). (b) Percentage of cells with sub-G1 (<2N) DNA content 18, 44 and 66 hr after treatment with CI-1040 (1.25 μM) and GSK923295 (125 nM).

Combined inhibition of MEK/ERK and CENP-E is also effective in cell lines from other tumor types with common RAS/RAF/MEK pathway activation

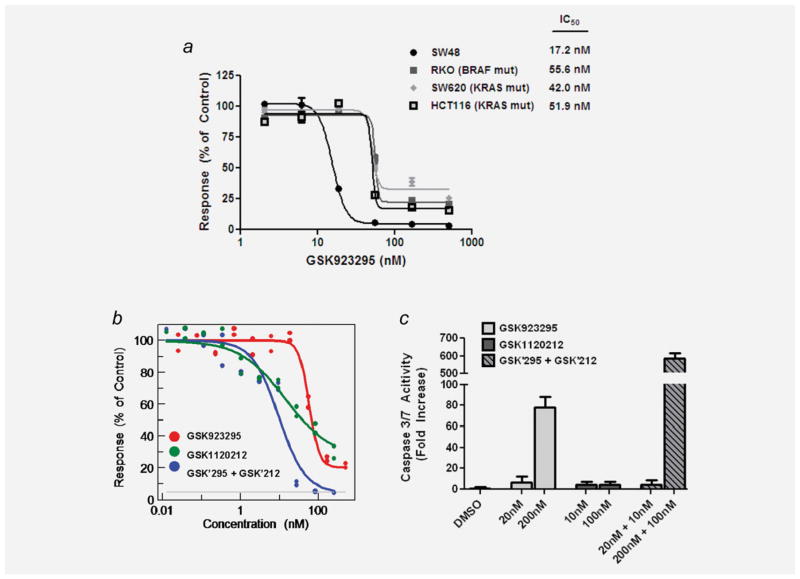

To determine whether MEK/ERK pathway inhibition sensitizes cell lines from tumor types other than neuroblastoma to GSK923295, we tested a panel of lung (n = 14), pancreatic (n = 8) and colon (n = 4) cancer cell lines. Many of the cell lines in this panel have oncogenic activation of the MEK/ ERK pathway either through RAS or RAF mutations (Table 2). Cells were treated with a specific small molecule inhibitor of MEK (GSK1120212) in combination with the CENP-E inhibitor GSK923295. The combination of GSK1120212 and GSK923295 was synergistic at the ED50 in all cell lines that were tested and was synergistic in all but two lines (H2030 and YAPC) at the ED75 (Table 2). In the panel of colon carcinoma cell lines, we found that GSK923295 was more potent and had a greater maximum growth inhibitory effect in the RAS/RAF wild-type colon cancer cell line (SW48) as compared to the three RAS or RAF mutant colon cancer cell line-sRKO, SW620 andHCT116 (Fig. 3a). We next combined GSK923295 with GSK1120212 in the B-Raf mutant cell line RKO, which resulted in both a decrease in the IC50 of growth inhibition and an increase in the maximal growth inhibitory effect (Fig. 3b). We also analyzed the potential apoptotic response to GSK1120212/GSK923295 combination, which showed a 7.5-fold increase in the caspase-3/7 activity of GSK1120212/GSK923295 combination compared to single agent GSK923295 treatment (p ≤ 0.0001) (Fig. 3c). The significant increase in caspase-3/7 activity is an explanation for the increase in maximal growth inhibition (y-min) observed with GSK1120212/GSK923295 combination compared to GSK923295 single agent treatment in Figure 3b.

Table 2.

The combination of MEK inhibitor (GSK1120212) and GSK923295 has synergistic activity across different tumor types

| C.I. values at | r | 1 KRAS | NRAS | BRAF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED50 | ED75 | |||||

| Lung | ||||||

| H460 | 0.25062 | 0.29455 | 0.88845 | c.183A>T | WT | WT |

| H23 | 0.25882 | 0.23436 | 0.94317 | WT | WT | WT |

| H2030 | 0.30845 | 2.32903 | 0.93202 | c.34G>T | WT | WT |

| H2228 | 0.31718 | 0.40462 | 0.97727 | WT | WT | WT |

| H2170 | 0.37052 | 0.62459 | 0.89425 | WT | WT | WT |

| H1299 | 0.38288 | 0.51188 | 0.98585 | WT | c.181C>A | WT |

| H1563 | 0.40538 | 0.24393 | 0.69512 | WT | WT | WT |

| H358 | 0.41642 | 0.46758 | 0.95043 | c.34G>T | WT | WT |

| H1792 | 0.4847 | 0.48282 | 0.9727 | c.34G>T | WT | WT |

| Calu-6 | 0.55652 | 0.53344 | 0.95357 | c.181C>A | WT | WT |

| A549 | 0.61431 | 0.40223 | 0.97239 | c.34G>A | WT | WT |

| SW900 | 0.70479 | 0.65336 | 0.99526 | c.35G>T | WT | WT |

| H520 | 0.84162 | 0.71559 | 0.87107 | WT | WT | WT |

| H2122 | 0.84993 | 0.79601 | 0.93092 | c.34G>T | WT | WT |

| Pancreatic | ||||||

| Capan-1 | 0.0532 | 0.0909 | 0.98591 | c.35G>T | WT | WT |

| SW1990 | 0.17643 | 0.10296 | 0.98554 | c.35G>A | WT | WT |

| Capan-2 | 0.29845 | 0.15331 | 0.85484 | c.35G>T | WT | WT |

| MiaPaCa | 0.39423 | 0.31149 | 0.93241 | c.34G>T | WT | WT |

| HUP-T4 | 0.45213 | 0.89233 | 0.94958 | c.35G>T | WT | WT |

| ASPC-1 | 0.5657 | 0.32264 | 0.97633 | c.35G>A | WT | WT |

| HPAF-II | 0.56738 | 0.47358 | 0.97667 | c.35G>A | WT | WT |

| YAPC | 0.65917 | 1.31043 | 0.9122 | c.35G>T | WT | WT |

| Colon | ||||||

| SW48 | 0.35998 | 0.0913 | 0.94221 | WT | WT | WT |

| RKO | 0.3735 | 0.2063 | 0.93505 | WT | WT | c.1799T>A |

| SW620 | 0.52101 | 0.2887 | 0.96998 | c.35G>T | WT | WT |

| HCT116 | 0.6946 | 0.38435 | 0.96442 | c.38G>A | WT | WT |

The K-RAS, N-RAS and B-RAF mutation status is listed as nucleotide base change for each cell line. Wild-type (WT).

Figure 3.

Pharmacologic MEK/ERK inhibition significantly increases GSK923295-activity in colon cancer cell lines. (a) The IC50 of colon cancer cell lines with differential oncogenic activation of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway 72 hr after treatment with GSK923295 (doses of 3-fold dilutions ranging from 2.05nM–500nM). (b) Dose response curves of GSK923295, GSK1120212 and the two drug combination in RKO cells as measured by Cell-TiterGlo 96 hr after treatment. (c) Caspase-3/7 activity relative to DMSO 24 hr after treatment with indicated doses of drug in RKO cells. Caspase-3/7 bioluminescence intensity is normalized to Cell-TiterGlo bioluminescence intensity to control for cell density. Bars represent mean Caspase 3/7 activity ± (S.E.M.).

MEK/ERK pathway activity is predictive for GSK923295 sensitivity

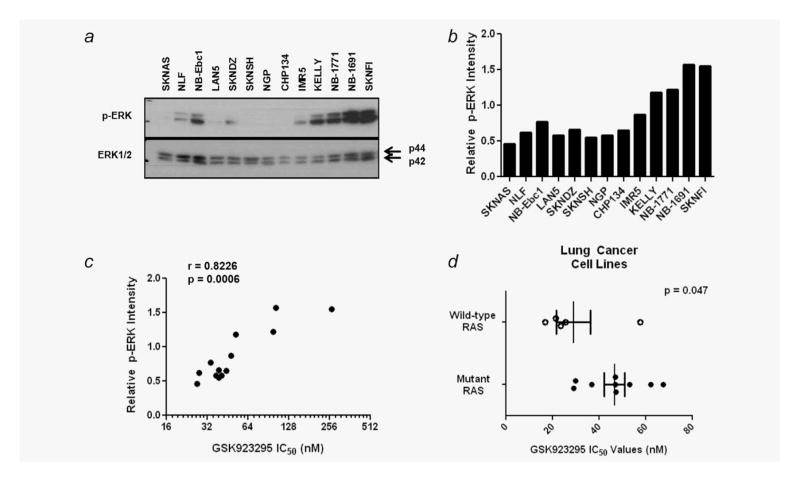

We next examined whether MEK/ERK pathway activity is a predictive marker for the relative sensitivity to GSK923295. Western blot analysis of ERK phosphorylation status in neuroblastoma cells showed a wide range of MEK/ERK pathway activity (Figs. 4a and 4b). SK-N-FI cells were among the neuroblastoma cell lines with the highest relative ERK phosphorylation which is likely explained by a homozygous loss of NF1 in this cell line.12 Interestingly, the relative ERK phosphorylation status showed a strong correlation with the GSK923295 sensitivity of neuroblastoma cell lines (r = 0.8226; p = 0.0006) (Fig. 4c). To determine whether the correlation between MEK/ERK pathway activity and GSK923295 sensitivity in neuroblastoma is true for other tumor types we tested a panel of 14 lung cancer cell lines that harbored either mutant or wild-type RAS oncogene. Eight of the cell lines had mutant K-RAS and one had an N-RAS mutation. None of the cell lines tested was mutant for B-RAF (Table 2). Although all of the lung cancer cell lines in the panel are relatively sensitive to GSK923295; those with a RAS mutation (n = 9) were on average significantly more resistant than those with wild-type RAS (n = 5; p = 0.047; Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

MEK/ERK pathway activity is predictive for the relative GSK923295 sensitivity. (a) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated ERK1/ 2 and total ERK1/2 in a panel of neuroblastoma cell lines. (b) Phospho-ERK1/2 intensity relative to total ERK1/2 intensity as measured by densitometry of bands from Western blot in (a). (c) Relative phospho-ERK1/2 intensity versus GSK923295 IC50 values of neuroblastoma cell lines. X-axis shown as Log2. (d)The GSK923295 IC50 values in lung cancer cell lines with wild-type RAS are on average significantly less than those with mutant RAS (p = 0.047). Markers represent mean ± (S.E.M.).

Discussion

Combinatorial drug regimens are intended to provide additive or supra-additive anti-tumor activity while avoiding acquired resistance to individual agents. The treatment of patients with advanced neuroblastoma exemplifies this approach, as patients receive an intensive induction regimen which includes cytotoxic chemotherapies as well as a combination of biologic therapies including 13-cis-retinoic acid, an anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and Interleukin-2.13,14 Despite this aggressive treatment regimen, a majority of patients either fail to respond or eventually show disease relapse. Salvage therapy for these patients often includes the combination of a camptothecin and an alkylator, with irinotecan and temozolomide being a most common salvage regimen currently used in North America.11,15 In addition, with more than a dozen new molecularly-targeted therapies currently being tested in clinical trials for the treatment of patients with advanced neuroblastoma (www.clinicaltrials.gov), the well-tolerated combination of irinotecan and temozolomide is designed as a backbone regimen upon which molecularly targeted agents can be tested.11,16 We suggest that translational advances in this disease should seek novel combinatorial therapies, as well as exploring, in parallel, integration with commonly used chemotherapy regimens.

In this report, we examine the activity of the CENP-E inhibitor (GSK923295) when combined with standard chemotherapies as well as other emerging molecularly targeted drugs, to determine a combination strategy for GSK923295 in patients with neuroblastoma and other cancers. The combination of GSK923295 with irinotecan and temozolomide showed synergistic activity in two neuroblastoma cell lines (NB-1691 and SK-N-FI) that are relatively resistant to GSK923295 monotherapy (Supporting Information Table 1). However, there was limited growth inhibitory benefit of GSK923295/irinotecan/temozolomide combination compared to the current standard-of-care irinotecan/temozolomide dual-combination (Supporting Information Fig. 1). Furthermore, the combination of GSK923295 and irinotecan was moderately antagonistic in SK-N-FI cells. This antagonism may be the result of DNA-damage induced by irinotecan, which prevents or delays entry into mitosis, the cell cycle phase where cells are sensitive to CENP-E inhibition. Further studies should be aimed at optimizing dosing schedules for the use of GSK923295, and perhaps other anti-mitotic agents, when used in combination with standard neuroblastoma chemotherapy regimens.

Our functional screen of siRNAs targeted to genes in therapeutically tractable signaling pathways identified ERK1 inhibition as a potent sensitizer to GSK923295-induced growth inhibition (Fig. 1). ERK1 is a member of the MAPK family that is activated by MEK1/2. The RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway plays a clear role in the regulation of G1/S cell-cycle transition leading to cell proliferation in response to growth factor signaling or cell adhesion.17 However, the role of MEK-ERK signaling in the regulation of mitosis is less well established. A number of reports have shown that RAF-MEK-ERK signaling is required for satisfaction of the spindle assembly checkpoint and promotion of the meta-phase–anaphase transition.18–20 Interestingly, ERK1/2 activity has also been shown to increase during mitosis21 and co-localize with CENP-E at the kinetochores during metaphase.22 These investigators also demonstrated in vitro phosphorylation of CENP-E by ERK at a site known to regulate CENP-E binding to microtubules during mitosis.22 Therefore, the synergistic activity of combinatorial ERK and CENP-E inhibition may be partially explained by the direct regulation of CENP-E activity by MEK-ERK signaling during mitosis.

Hyperactivation of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway is one of the most common oncogenic features of human cancer. Activating point mutations of RAS family members have been identified in ~20% of human tumors with much higher percentages in pancreas, lung, colon and thyroid tumors.23 Mutational activation of the RAF family member (B-RAF) is also a common feature of specific cancer types including melanoma and colon carcinoma. The pathway can also be activated upstream of RAS through overexpression or mutation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs).24 In the present study, we tested cell lines from three tumor types (pancreatic, lung and colon) that have high percentages of oncogenic RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway activation (Table 2). We chose these cancer types because they represent the tumor types most likely to benefit from pharmacologic MEK inhibition either alone or in combination with other drugs including GSK923295. Unlike pancreatic, lung and colon tumors, frequent mutations in canonical RAS/RAF/MEK/ ERK signaling pathway proteins have not yet been discovered in neuroblastoma. N-RAS mutations and inactivation of neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF1), a protein with RAS-GAP activity, have been observed in small percentages of neuroblastomas (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic/).12 In this regard, SK-N-FI cells harbor a homozygous deletion of NF1 which likely explains the high ERK activity and corresponding GSK923295 insensitivity that we observed in this cell line (Fig. 4). Increased activation of MEK-ERK signaling can also occur in neuroblastoma as a result of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) hyperactivation through gene amplification, mutation or overexpression,25–29 as well as hyperactive neurotrophin receptor signaling.30,31 Future studies will define the precise molecular mechanisms other than RAS and RAF mutation for MAPK pathway activation in neuroblastoma, and whether or not phospho-ERK or phospho-MEK levels are predictive biomarkers for treatment response.

To achieve pharmacologic inhibition of MEK-ERK signaling, we used two different small molecule inhibitors of MEK. CI-1040 (PD184352) is an allosteric inhibitor of MEK that results in a dose-dependent decrease in ERK1/2 phosphorylation.32 GSK1120212 is a potent and highly selective inhibitor of MEK1 that also demonstrates efficient inhibition of ERK1/ 2 phosphorylation. Preclinical studies have shown that GSK1120212 causes inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in some cancer types and oral administration in mice results in tumor regression in multiple xenograft models.33 As a result, GSK1120212 is currently being tested in clinical trials for multiple cancer types and in combination with several other drugs (www.clinicaltrials.gov). We found that both CI-1040 and GSK1120212 resulted in synergistic growth inhibitory activity when combined with GSK923295 in four different cancer cell types including neuroblastoma (Table 1 and 2). In line with our findings, MEK/ERK pathway inhibition has been previously shown to sensitize cancer cells to various pharmacologic mitotic inhibitors.34,35 A recent report showed that co-administration of CI-1040 sensitized two different colon carcinoma mice xenograft models to TZT-1027 or vinorelbine-induced tumor growth inhibition.36 These results suggest that combinatorial MEK/ERK and mitotic inhibition is a potential anticancer therapeutic strategy.

Here we show that high RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway activity is a negative predictor for response to the CENP-E inhibitor GSK923295 across different tumor types. In 13 neuroblastoma cell lines tested there was a strong correlation between high ERK phosphorylation and insensitivity to GSK923295-induced growth inhibition (p = 0.0006). Likewise, among the 14 lung cancer cell lines we tested, those with a RAS mutation were on average significantly more resistant to GSK923295 than those with wild-type RAS (p = 0.047). In cancer types where oncogenic activation of specific MEK-ERK pathway proteins, such as RAS and RAF, are common it may be possible to select GSK923295 responsive patient populations based upon the absence of these alterations. However, since MEK-ERK signaling is activated by a wide range of both genetic and epigenetic alterations, it may be necessary to directly assay MEK/ERK phosphorylation status for this purpose.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that combinatorial inhibition of MEK/ERK signaling and CENP-E motor function is a promising anticancer therapeutic strategy. We performed preclinical proof-of-concept studies which established the synergistic activity of MEK and CENP-E inhibitor combinations in a panel of 29 cell lines across four different tumor types. Importantly, the synergistic activity of dual-inhibition does not appear to be restricted to cancer cells with known oncogenic activation of MEK-ERK signaling. Our results also establish MEK-ERK activity as a predictive biomarker of relative sensitivity of tumor cells to CENP-E inhibition. Future experiments will be designed to test MEK/ERK and CENP-E dual-inhibition in preclinical animal models of neuroblas-toma and other tumors. These findings as well as ongoing experiments will provide preclinical rationale to help guide the continued clinical development of pharmacologic inhibitors of MEK and CENP-E.

Supplementary Material

What’s new?

One goal of current chemotherapy research is to discover drug combinations that have a synergistic effect against malignant tumors. In this study, the authors used a panel of siRNAs to search for compounds that sensitize tumor cells to the small-molecule drug GSK923295, which blocks CENP-E activity. They found that inhibitors of the MEK-ERK signaling pathway yielded potent synergistic activity against various types of cancer cells when combined with GSK923295. This type of combination regimen is therefore a promising therapeutic strategy. The results also revealed that RAS/RAF/MEK signaling can provide a predictive biomarker for sensitivity to GSK923295.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsors: GlaxoSmithKline, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, Andrew’s Army Foundation

Research was funded through a research collaborative agreement between GlaxoSmithKline and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (J.M.M), and grants from Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation (J.M.M) and the Andrew’s Army Foundation (J.M.M.). P.A.M, Y.Y.D, C.M and R.W. are current employees and stockholders of GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Wood KW, Chua P, Sutton D, et al. Centromere-associated protein E: a motor that puts the brakes on the mitotic checkpoint. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7588–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao Y, Abrieu A, Cleveland DW. Activating and silencing the mitotic checkpoint through CENP-E-dependent activation/inactivation of BubR1. Cell. 2003;114:87–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaar BT, Chan GK, Maddox P, et al. CENP-E function at kinetochores is essential for chromosome alignment. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1373–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanudji M, Shoemaker J, L’Italien L, et al. Gene silencing of CENP-E by small interfering RNA in HeLa cells leads to missegregation of chromosomes after a mitotic delay. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3771–81. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu C, Zhao J, Bibikova M, et al. Functional analysis of human microtubule-based motor proteins, the kinesins and dyneins, in mitosis/ cytokinesis using RNA interference. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3187–99. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood KW, Lad L, Luo L, et al. Antitumor activity of an allosteric inhibitor of centromere-associated protein-E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5839–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915068107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balamuth NJ, Wood A, Wang Q, et al. Serial transcriptome analysis and cross-species integration identifies centromere-associated protein E as a novel neuroblastoma target. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2749–58. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson JR, Patrick DR, Dar MM, et al. Targeted anti-mitotic therapies: can we improve on tubulin agents? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:107–17. doi: 10.1038/nrc2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degenhardt Y, Greshock J, Laquerre S, et al. Sensitivity of cancer cells to Plk1 inhibitor GSK461364A is associated with loss of p53 function and chromosome instability. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2079–89. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner LM, Villablanca JG, Stewart CF, et al. Phase I trial of oral irinotecan and temozolomide for children with relapsed high-risk neuroblastoma: a new approach to neuroblastoma therapy consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1290–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagatell R, London WB, Wagner LM, et al. Phase II study of irinotecan and temozolomide in children with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: a children’s oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:208–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holzel M. NF1 is a tumor suppressor in neuroblastoma that determines retinoic acid response and disease outcome. Cell. 2010;142:218–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, et al. Neuroblastoma. Lancet. 2007;369:2106–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, et al. Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1324–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.London WB, Frantz CN, Campbell LA, et al. Phase II randomized comparison of topotecan plus cyclophosphamide versus topotecan alone in children with recurrent or refractory neuroblastoma: a Children’s Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3808–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maris JM. Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2202–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sebolt-Leopold JS, Herrera R. Targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to treat cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:937–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borysova MK, Cui Y, Snyder M, et al. Knockdown of B-Raf impairs spindle formation and the mitotic checkpoint in human somatic cells. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2894–901. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matkovic K, Lukinovic-Skudar V, Banfic H, et al. The activity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase is required during G2/M phase before metaphase-anaphase transition in synchronized leukemia cell lines. Int J Hematol. 2009;89:159–66. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu X, Yan S, Zhou T, et al. The MAP kinase pathway is required for entry into mitosis and cell survival. Oncogene. 2004;23:763–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright JH, Munar E, Jameson DR, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase activity is required for the G(2)/M transition of the cell cycle in mammalian fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11335–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zecevic M, Catling AD, Eblen ST, et al. Active MAP kinase in mitosis: localization at kinetochores and association with the motor protein CENP-E. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1547–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gschwind A, Fischer OM, Ullrich A. The discovery of receptor tyrosine kinases: targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:361–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janoueix-Lerosey I, Lequin D, Brugieres L, et al. Somatic and germline activating mutations of the ALK kinase receptor in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:967–70. doi: 10.1038/nature07398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.George RE, Sanda T, Hanna M, et al. Activating mutations in ALK provide a therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:975–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosse YP, Wood A, Maris JM. Inhibition of ALK signaling for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5609–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YY, Takita J, Choi YL, et al. Oncogenic mutations of ALK kinase in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:971–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marzec M, Kasprzycka M, Liu X, et al. Oncogenic tyrosine kinase NPM/ALK induces activation of the rapamycin-sensitive mTOR signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2007;26:5606–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eggert A, Ikegaki N, Liu X, et al. Molecular dissection of TrkA signal transduction pathways mediating differentiation in human neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:2043–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodeur GM, Minturn JE, Ho R, et al. Trk receptor expression and inhibition in neuroblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3244–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sebolt-Leopold JS, Dudley DT, Herrera R, et al. Blockade of the MAP kinase pathway suppresses growth of colon tumors in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:810–16. doi: 10.1038/10533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilmartin AG, Bleam MR, Groy A, et al. GSK1120212 (JTP-74057) is an inhibitor of MEK activity and activation with favorable pharmacokinetic properties for sustained in vivo pathway inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:989–1000. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDaid HM, Lopez-Barcons L, Grossman A, et al. Enhancement of the therapeutic efficacy of taxol by the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor CI-1040 in nude mice bearing human heterotransplants. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2854–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKeigan JP, Collins TS, Ting JP. MEK inhibition enhances paclitaxel-induced tumor apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38953–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe K, Tanimura S, Uchiyama A, et al. Blockade of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway enhances the therapeutic efficacy of microtubule-destabilizing agents in human tumor xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1170–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.