Abstract

Diarrhea caused by Vibrio cholerae is known to give long-lasting protection against subsequent life-threatening illness. The serum vibriocidal antibody response has been well studied and has been shown to correlate with protection. However, this systemic antibody response may be a surrogate marker for mucosal immune responses to key colonization factors of this organism, such as the toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) and other factors. Information regarding immune responses to TCP, particularly mucosal immune responses, is lacking, particularly for patients infected with the El Tor biotype of V. cholerae O1 or V. cholerae O139 since highly purified TcpA from these strains has not been available previously for use in immune assays. We studied the immune responses to El Tor TcpA in cholera patients in Bangladesh. Patients had substantial and significant increases in TcpA-specific antibody-secreting cells in the circulation on day 7 after the onset of illness, as well as similar mucosal responses as determined by an alternate technique, the assay for antibody in lymphocyte supernatant. Significant increases in antibodies to TcpA were also seen in sera and feces of patients on days 7 and 21 after the onset of infection. Overall, 93% of the patients showed a TcpA-specific response in at least one of the specimens compared with the results obtained on day 2 and with healthy controls. These results demonstrate that TcpA is immunogenic following natural V. cholerae infection and suggest that immune responses to this antigen should be evaluated for potential protection against subsequent life-threatening illness.

Diarrhea caused by Vibrio cholerae is known to give long-lasting protection against subsequent life-threatening illness (2, 3, 15). The serum vibriocidal antibody response has been well studied and has been shown to be correlated with protection (8, 16, 17, 18). However, this systemic antibody response may be a surrogate marker for mucosal immune responses to key colonization factors of this organism, such as the toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP). TCP is essential for V. cholerae colonization of the small intestine both in an infant mouse model of cholera (28) and during human infection (11). The gene encoding the major pilin subunit, TcpA, is located within a larger genetic element termed the Vibrio pathogenicity island or TCP/ACF element (7, 19). Although TcpA is expressed by both classical and El Tor biotypes of V. cholerae O1, as well as by V. cholerae O139, there is only 80% amino acid identity between the TcpA proteins of the two biotypes of V. cholerae O1 (12, 13, 28). TcpA of El Tor V. cholerae O1 and TcpA of V. cholerae O139 are identical (25).

In previous studies of the immune responses to TcpA in patients with V. cholerae infections the workers have examined patients infected with the classical biotype of V. cholerae O1 or have utilized classical TcpA to assess immune responses in patients infected with El Tor V. cholerae O1 (9). Recent studies in which the in vivo-induced antigen technology has been used have shown that TcpA is expressed during human infection with El Tor V. cholerae O1 and is immunogenic (10). Evidence for immunogenicity of El Tor V. cholerae O1 TcpA has also been obtained with convalescent-phase sera by utilizing partially purified El Tor TcpA and a monoclonal antibody-based sandwich assay (1).

Recently, recombinantly produced and purified El Tor TcpA has become available (5), and we utilized this reagent to carry out a detailed and comprehensive study of the mucosal and systemic immune responses to this colonization antigen in specimens obtained from patients with natural infections caused by El Tor V. cholerae O1 and V. cholerae O139 in Bangladesh.

(Preliminary results from this study were presented at the XII Annual Meeting of the International Centers for Tropical Disease Research, Bethesda, Md., May 2003.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study group.

Patients with acute watery diarrhea due to V. cholerae O1 or O139 were recruited to the study (Table 1). These patients included both males and females with cholera caused by the V. cholerae O1 Inaba (n = 30) and Ogawa (n = 30) serotypes, as well as patients with V. cholerae O139 infections. Healthy individuals in the same age range and with the same socioeconomic status but with no history of diarrhea during the previous 3 months were included as controls.

TABLE 1.

Clinical features of study subjects

| Group | n | Age (yr) | No. (%) of males | No. (%) of females | No. (%) infected with V. cholerae strain

|

No. (%) with blood group of:

|

Duration of illness at presentation (h)

|

% with indicated degree of dehydration at presentation

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 Ogawa | 01 Inaba | 0139 | A | B | AB | O | Median | 25 centile, 75 centile | Severe | Mild | |||||

| Patients | 90 | 25 (18, 35)a | 41 (45) | 49 (55) | 30 (33.3) | 30 (33.3) | 30 (33.3) | 19 (21) | 22 (25) | 10 (11) | 39 (43) | 17 | 8, 24 | 88 | 12 |

| Healthy controls | 30 | 29 (24, 35) | 16 (53) | 14 (47) | NAb | NA | NA | 7 (23) | 10 (33) | 2 (7) | 11 (37) | NA | NA | NA | |

Median (25 centile, 75 centile).

NA, not applicable.

Microbiologic work-up.

Cholera was confirmed in patients with acute watery diarrhea by stool culture, and the organisms recovered were differentiated serologically as V. cholerae O1 Ogawa, O1 Inaba, or O139 (24). Stools of patients were also tested for the presence of other enteric pathogens (including Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter spp.) by culture, for the presence of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli by PCR, and for the presence of ova and parasites by direct microscopy, and the results were negative. Stools of healthy controls included in the study were screened for these pathogens and were negative.

Sample collection and preparation.

After microbiological confirmation of cholera, venous blood and feces were collected from patients after they had been rehydrated. This occurred on the second day of hospitalization and was considered to be approximately 2 days after the onset of diarrhea (day 2). Serum and fecal samples were also collected 5 and 19 days later, during convalescence (that is, 7 and 21 days after onset of the disease, respectively). For control patients, single blood and fecal samples were collected.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from blood collected in heparinized vials (Vacutainer system; Becton Dickinson, Rutherford, N.J.) by gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Isopaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Plasma collected from the top of the Ficoll gradient was stored in aliquots at −20°C. Sera separated from blood collected in vials that did not contain any additive were divided into aliquots and stored at −20°C for antibody assays. Fecal extracts were prepared by mixing stools (1 g of feces in 4 ml of buffer) with phosphate-buffered saline containing EDTA (0.05 M), protease inhibitors, soybean trypsin inhibitor (100 μg/ml), and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (10 mM) (23). One milliliter of fecal extract was equivalent to 0.25 g of stool. Fecal extracts were frozen in aliquots at −70°C.

For tests involving stored serum and fecal extracts, samples from all 90 patients were available for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). For studies in which fresh PBMCs were used as the antibody in lymphocyte secretion (ALS) and antibody-secreting cell (ASC) assays, samples were available from only 50 cholera patients (15 patients with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa, 20 patients with V. cholerae O1 Inaba, and 15 patients with V. cholerae O139) and from only 24 cholera patients (10 patients with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa, 10 patients with V. cholerae O1 Inaba, and 4 patients with V. cholerae O139), respectively. Similarly, samples for all assays were not available from all control participants. The specific number of samples analyzed in each assay is indicated below.

Preparation of V. cholerae antigens used for immunologic assays.

TcpA was overexpressed in E. coli BL21 with a histidine tag fused at the amino-terminal end and was prepared as described previously (5). Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (strain X25049) and O1 Inaba (strain 19479) were purified as described previously (30). The major pilin subunit of the mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin (MSHA) was purified from V. cholerae O1 and was prepared by a method described previously (14); MSHA was a gift from Ann-Mari Svennerholm, Goteborg University, Goteborg, Sweden.

Detection of ASC in the circulation.

The ASC assay is a well-established proxy for mucosal immune responses at the gut surface. Ficoll-separated PBMCs recovered from patients on days 2 and 7 after the onset of diarrhea were assayed for TcpA-specific ASC by the ELISPOT technique (6) by using modifications described previously (20, 22). Individual wells of nitrocellulose bottom 96-well plates (Millititer HA; Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) were coated with 0.1 ml of TcpA (5 μg/ml) in 50 mM carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) and kept overnight at room temperature. Cells secreting antibodies of the immunoglobulin A (IgA), IgG, and IgM isotypes specific for bound TcpA were determined as described previously (20, 22). A positive ASC response was defined as more than 10 ASC/107 PBMCs. TcpA-specific ASC responses were studied in 10 patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa, 10 patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Inaba, and 20 healthy controls. Since the incidence of infection caused by V. cholerae O139 was low during the course of the study, ASC responses to TcpA were determined in only four patients with V. cholerae O139 infections.

ALS.

An optimized procedure for an alternate measure of the mucosal immune response to antigens, the ALS assay, has been described recently (4, 23). Since this technique can be used with samples that were previously collected and frozen, we used the ALS assay to compare TcpA-specific responses in patients with V. cholerae O1 and O139 infections, including patients seen in a previous study of O139 infection (23).

For the ALS assay, isolated PBMCs separated from patient samples collected on days 2 and 7 were incubated in 24-well tissue culture plates at a concentration of 1 × 107cells/ml in RPMI medium (with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% glutamine, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% penicillin-streptomycin) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 h by using sterile techniques. After incubation, the plates were centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were collected. A protease inhibitor cocktail containing aprotinin (0.15 μM), leupeptin (10 μM), sodium azide (15 μM), and 4-(aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (0.2 μM) was added to each supernatant (10 μl/ml of supernatant), and the samples were frozen immediately in aliquots at −70°C until they were assayed. The ALS assay was used to determine TcpA-specific IgA antibody responses in an ELISA as described below; the anti-TcpA response was measured in 15 patients with a V. cholerae O1 Ogawa infection, 20 patients with a V. cholerae O1 Inaba infection, and 15 patients with a V. cholerae O139 infection. Twenty healthy volunteers were also tested by the ALS assay.

Detection of TcpA-specific antibodies in sera, feces, and lymphocyte supernatants by ELISA.

Serum samples collected from patients at the acute stage of infection (day 2) and at the convalescent stage of infection (day 7 and day 21 after onset) were tested against TcpA (coating concentration in 50 mM carbonate buffer [pH 9.6], 1 μg/ml) by an ELISA by using previously described procedures (20). The ALS specimens were assayed undiluted, while serum samples were tested at a 1:200 dilution. The optical densities were measured kinetically at 450 nm for 5 min, and the results were expressed as the change in milliabsorbance units per minute (26). Fecal extracts were tested for antibody to TcpA by an ELISA, and the results were expressed as the change in milliabsorbance units per microgram of total IgA in the extract (26). A twofold or greater increase in the ELISA results between day 2 and either day 7 or 21 was considered a positive response.

Detection of LPS- and MSHA-specific IgA responses in sera, fecal extracts, and lymphocyte supernatants from V. cholerae O1 patients.

Immune responses in sera, fecal extracts, and lymphocyte supernatants obtained from patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Inaba (n = 20) and V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (n = 15) to homologous LPS, as well as MSHA, were also studied by utilizing procedures described previously (20-23). ELISA plates were coated with LPS at a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml or with MSHA at a concentration of 1.0 μg/ml.

Statistical analyses.

The Wilcoxon signed rank test, the rank sum test, and the Mann-Whitney U test were used where applicable for statistical analysis. Data were expressed as medians and 25 and 75 centiles or as geometric means. A two-sided P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were carried out by using the SigmaStat statistical software (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, Calif.).

RESULTS

Clinical features of the study subjects.

Patients with cholera most commonly presented with a short history of diarrhea (symptoms for 24 h or less), and 88% had severe diarrhea as determined by World Health Organization criteria (Table 1). The median ages, gender distributions, and ABO blood group distributions were similar for patients and controls.

TcpA-specific ASC responses in blood.

Study subjects had very low TcpA-specific ASC responses on day 2 (Table 2). The TcpA-specific ASC responses of the IgA isotype were significantly elevated by day 7 in all three groups of study subjects (Table 2). Seven of 10 patients with a V. cholerae O1 Ogawa infection showed a positive IgA ASC response at day 7 (P = 0.009), as did 7 of 10 subjects infected with V. cholerae O1 Inaba (P = 0.016). All four patients infected with V. cholerae O139 studied showed an increase in TcpA-specific ASC responses on day 7. ASC responses were also seen in the IgG and IgM isotypes, and the frequencies and magnitudes of the responses were similar. The levels of ASC responses to TcpA were negligible in all 20 healthy controls studied and similar to those seen on day 2 in the study subjects (results not shown).

TABLE 2.

TcpA-specific ASC responses in patients with cholera

| Study subjects | n | IgA

|

IgM

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2

|

Day 7

|

Day 2

|

||||||||

| No. of positive ASC/107 PBMCs | P value compared to day 2a | Response rate compared to day 2 (%)b | No. of positive ASC/107 PBMCs | P value compared to day 2a | Response rate compared to day 2 (%)b | No. of positive ASC/107 PBMCs | P value compared to day 2a | Response rate compared to day 2 (%)b | ||

| Patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa | 10 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01)c | NAd | NA | 67.1 (0.01, 339)c | 0.009 | 70 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01)c | NA | NA |

| Patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Inaba | 10 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | NA | NA | 100 (0.01, 275) | 0.016 | 70 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | NA | NA |

| Patients infected with V. cholerae O139 | 4 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | NA | NA | 100 (70, 160) | 0.029 | 100 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | NA | NA |

Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was determined by the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Response rate indicates a twofold or higher number of antigen-specific ASC at convalescence compared to the number at day 2.

Median (25 centile, 75 centile).

NA, not applicable.

a.

TABLE 2 - Continued

| IgM

|

IgG

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 7

|

Day 2

|

Day 7

|

||||||

| No. of positive ASC/107 PBMCs | P value compared to day 2a | Response rate compared to day 2 (%)b | No. of positive ASC/107 PBMCs | P value compared to day 2a | Response rate compared to day 2 (%)b | No. of positive ASC/107 PBMCs | P value compared to day 2a | Response rate compared to day 2 (%)b |

| 10.0 (0.01, 210) | 0.025 | 60 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01)c | NA | NA | 70.6 (10, 120)c | 0.03 | 80 |

| 15 (0.01, 50) | 0.031 | 60 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | NA | NA | 125 (0.01, 230) | 0.016 | 70 |

| 90 (75,115) | 0.029 | 100 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | NA | NA | 90 (50, 190) | 0.029 | 100 |

TcpA-specific IgA responses in the antibody in the lymphocyte supernatant assay (ALS assay).

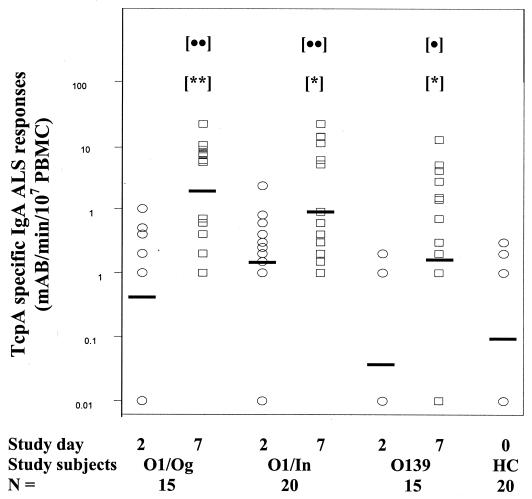

TcpA-specific IgA responses were also seen in the ALS assay in patients on day 7 of illness compared with the responses in patients on day 2 or in healthy controls (Fig. 1). Twelve of 15 patients with a V. cholerae O1 Ogawa infection, 12 of 20 patients with a V. cholerae O1 Inaba infection, and 10 of 15 patients with a V. cholerae O139 infection showed increases in the ALS response at day 7 compared to the response at day 2. The TcpA-specific levels in the ALS assay were low on day 2 and comparable to those seen in healthy controls (the difference was not significant).

FIG. 1.

TcpA-specific IgA responses in ALS assays for patients with cholera due to V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (O1/Og), O1 Inaba (O1/In), or O139. The data points indicate individual values, and the bars indicate geometric means. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between the day 2 responses and the day 7 responses (one asterisk, P < 0.01 to 0.001; two asterisks, P < 0.001). Statistically significant differences between the responses of healthy controls and the responses of patients during convalescence are indicated by dots (one dot, P < 0.01 to P < 0.001; two dots, P < 0.001). mAB, milliabsorbance units; HC, healthy controls.

TcpA-specific antibody responses in sera of patients with cholera.

All three groups of patients infected with V. cholerae showed significant increases in serum IgA antibody responses to TcpA on days 7 and 21 compared to the responses on day 2 (Table 3). Sixty-three percent of the patients with a V. cholerae O1 Ogawa infection showed a significant increase in the level of serum IgA antibody to TcpA at day 7, compared with 60% of the patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Inaba and 73% of the patients infected with V. cholerae O139. The serum IgA antibody levels in 30 healthy controls were low and comparable to those seen at day 2 in patients (median, 3.83 milliabsorbance units/min; range, 2.33 to 5.33 milliabsorbance units/min).

TABLE 3.

TcpA-specific IgA antibody responses in sera and feces of patients with choleraa

| Study subjects | n | Serum

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2

|

Day 7

|

Day 21

|

||||||

| Response | P value compared to day 2b | Response | P value compared to day 2b | Cumulative response rate compared to day 2 (%)c | Response | P value compared to day 2b | ||

| Patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa | 30 | 3.33 (2.5, 4.7)d | NAe | 5.5 (2.7, 31.7)d | 0.007 | 63 | 6.0 (3.5, 10.7)d | 0.006 |

| Patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Inaba | 30 | 4.0 (2.3, 6.3) | NA | 9.35 (3.3, 31.7) | 0.001 | 60 | 5.48 (3.3, 11.7) | 0.010 |

| Patients infected with V. cholerae O139 | 30 | 4.58 (3.3, 5.7) | NA | 15.67 (7, 77.6) | <0.001 | 73 | 10.16 (7, 28.97) | <0.001 |

Serum anti-TcpA IgA responses are expressed in milliabsorbance units per minute. Stool anti-TcpA IgA responses are expressed in milliabsorbance units per minute per microgram of total IgA.

Statistical signifance (P < 0.05) was determined by using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

A twofold or greater increase in the response at convalescence compared to day 2 samples was considered a significant increase.

Median (25 centile, 75 centile).

NA, not applicable.

a.

TABLE 3-Continued

| Feces

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2

|

Day 7

|

Day 21

|

||||

| Response | P value compared to day 2b | Response | P value compared to day 2b | Cumulative response rate compared to day 2 (%)c | Response | P value compared to day 2 |

| 1.0 (0.7, 1.7)d | NA | 3.83 (1.0, 12.3)d | <0.001 | 83 | 3.13 (1.0, 12.7)d | <0.001 |

| 1.49 (0.5, 5.33) | NA | 4.33 (2, 17) | 0.040 | 80 | 5.09 (2, 17.7) | 0.014 |

| 1.0 (0.7, 2) | NA | 4.42 (1.5, 10.7) | 0.001 | 77 | 3.27 (1.3, 7.3) | 0.001 |

TcpA-specific IgA responses in fecal extracts.

Patients with a V. cholerae infection showed significant increases in TcpA-specific antibody in fecal extracts on days 7 and 21 compared with the levels on day 2 (Table 3). Significant increases in the TcpA-specific antibody level in fecal extracts were found in 83% of the patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa, compared with 80% of the patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Inaba and 77% of the patients infected with V. cholerae O139. Low levels of fecal antibodies specific for TcpA were found in healthy controls, and the levels were comparable to those seen on day 2 in infected patients (median, 0.10 milliabsorbance unit/min/μg of total IgA; range, 0.0 1 to 2 milliabsorbance units/min/μg of total IgA).

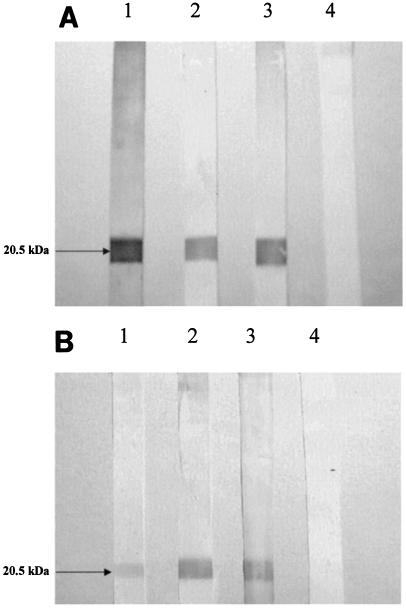

Immunoblot assays for immune responses to TcpA with serum and fecal extracts.

We utilized Western immunoblotting to detect specific antibody responses to the 20.5-kDa purified TcpA protein separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The convalescent-phase sera of V. cholerae patients collected on day 7 or 21 following infection specifically recognized the TcpA protein when Western blotting was used (see representative patient samples in Fig. 2A). Fecal extracts from these patients also specifically detected TcpA protein when Western blotting was used (see representative patient samples in Fig. 2B). Over 80% of the patients with a V. cholerae O1 or O139 infection had antibody in the serum and/or fecal extracts that recognized TcpA by day 7 of infection, whereas none of these patients had antibody to this protein on day 2. In 10 healthy controls, neither sera nor fecal extracts recognized TcpA when immunoblotting was used.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot assay to detect TcpA-specific IgA antibodies in sera and fecal extracts. (A) Sera of patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (lane 1), V. cholerae O1 Inaba (lane 2), and V. cholerae O139 (lane 3) and a healthy control (lane 4); (B) fecal extracts of patients infected with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (lane 1), V. cholerae O1 Inaba (lane 2), and V. cholerae O139 (lane 3) and a healthy control (lane 4).

Comparison of immune responses to TcpA with immune responses to LPS and MSHA.

We compared immune responses to TcpA, LPS, and MSHA in patients infected with V. cholerae (Table 4). The responder frequency rates for TcpA and MSHA in all three assays were similar, whereas the responder frequency rates for LPS were slightly higher in ALS and serum assays. Overall, 93% of the patients with a V. cholerae O1 infection showed an IgA immune response to TcpA in one or more of the assays (ALS, serum antibody, and antibody in fecal extract).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of the TcpA-specific IgA antibody responses to responses to other antigens in patients infected with V. cholerae O1

| Immune assay | Responder frequency (%)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TcpA | MSHA | LPS | |

| ALS | 69 | 69 | 88 |

| Serum | 62 | 69 | 88 |

| Fecal extract | 82 | 69 | 77 |

Responder frequency refers to comparisons of day 2 to either day 7 or day 21 values in individual patients where applicable. For the comparison, individuals with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (n = 15) and O1 Inaba (n = 20) infections were included.

DISCUSSION

The results obtained here demonstrate that the 20.5-kDa subunit of TCP (TcpA) is immunogenic in patients infected with V. cholerae O1 El Tor and V. cholerae O139 in Bangladesh. Previous studies have shown that individuals convalescing from cholera have strong immune responses to the B subunit of cholera toxin and to the LPS of the infecting strain (24). Patients with cholera also have immune responses, albeit weaker, to another type IV pilus of V. cholerae, the 17.4-kDa pilus subunit of the MSHA (22, 23). The immune responses to the B subunit of cholera toxin, to LPS, and to MSHA, however, have not been shown to correlate with protection against subsequent infection with V. cholerae. The vibriocidal antibody response has been shown previously to correlate with protection (8, 16, 17, 18). However, this serum complement-fixing antibody is unlikely to be active at the mucosal surface, where complement is lacking. Therefore, the vibriocidal antibody response may be a surrogate marker of a protective mucosal immune response to another antigen.

Previous studies in which patients with cholera were examined for immune responses to TcpA either have been performed with North American volunteers challenged with the classical biotype of V. cholerae O1 or have utilized classical TcpA for immune assays with patients infected with El Tor V. cholerae O1 (9); these studies have shown that there are low rates of seroconversion. However, given that classical and El Tor TcpA exhibit only 80% amino acid identity (12, 13, 28), these previous studies may have underestimated the immune responses to TcpA in patients infected with El Tor V. cholerae O1. The recent availability of recombinantly produced and purified El Tor TcpA (5) has provided a more suitable reagent for assessing these immune responses. The results reported here demonstrate that both systemic and mucosal immune responses to TcpA occur in patients infected with El Tor V. cholerae O1, as well as in patients infected with V. cholerae O139, and that these responses are comparable in magnitude and frequency to those seen with LPS and MSHA. This dispels previous speculation that TcpA may not be sufficiently antigenic to engender an immune response or that repeated exposure may be needed for an adequate response. The rate of immune responses to TcpA demonstrated here, in fact, is similar to that seen with other V. cholerae antigens studied. It is not yet known, however, whether an immune response to TcpA is protective.

In addition to the ASC assay, we also assessed mucosal immune responses to TcpA with the ALS assay. We have previously shown that the mucosal immune responses to LPS, CtxB, and MSHA assessed by the ALS assay are comparable to the responses seen with the ASC assay. One of the important features of the ALS assay is that supernatants recovered from circulating lymphocytes obtained on day 7 of infection can be stored frozen on a long-term basis and then assayed at a future time. We utilized this property specifically to assess mucosal immune responses to TcpA in patients infected with V. cholerae O139, using samples from a previous study. The results obtained were comparable to those obtained in the ALS and ASC assays for the small number of patients studied acutely. This suggests that supernatants of lymphocytes collected during an outbreak can be recovered and frozen for study of immune responses at a later time, particularly when mucosal immune responses to a newly isolated antigen need to be measured. Since positive results in the ASC or ALS assay differentiate recent infection from past exposure to the pathogen in question, this approach allows measurement of an acute immune response at a later time.

We have an ongoing study in Bangladesh of patients hospitalized with cholera and their household contacts (27). Some of the household contacts develop symptomatic cholera, some are asymptomatically colonized, and some are not infected. Frozen supernatants from circulating lymphocytes obtained from exposed household contacts in the various categories after exposure to V. cholerae are currently being analyzed by the ALS assay to see if a robust mucosal immune response to TcpA after exposure might be responsible for mediating protective immunity.

In conclusion, our study showed that patients infected with El Tor V. cholerae O1 or O139 in Bangladesh mount substantial mucosal and systemic immune responses to the colonization antigen TcpA and that these responses are comparable in magnitude and frequency to the responses to other V. cholerae antigens tested to date. We are currently examining whether immune responses to this key colonization factor may be involved in protective immunity, both in household contacts exposed to V. cholerae and in individuals vaccinated with a live, oral, attenuated cholera vaccine.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant UO1 AI58935 to S.B.C. and grant RO1 AI40725 to E.T.R.), by a training grant from the Fogarty International Center (grant D43 TW05572 to S.B.C.), and by the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B). The ICDDR,B is supported by countries and agencies which share its concern for the health problems of developing countries.

We are grateful to Ann-Mari Svennerholm, Goteborg University, Goteborg, Sweden, for supplying MSHA.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Attridge, S. R., G. Wallerstrom, F. Qadri, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2004. Detection of antibodies to toxin-coregulated pili in sera from cholera patients. Infect. Immun. 72:1824-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cash, R. A., S. I. Music, J. P. Libonati, J. P. Craig, N. F. Pierce, and R. B. Hornick. 1974. Response of man to infection with Vibrio cholerae. II. Protection from illness afforded by previous disease and vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 130:325-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cash, R. A., S. I. Music, J. P. Libonati, M. J. Snyder, R. P. Wenzel, and R. B. Hornick. 1974. Response of man to infection with Vibrio cholerae. I. Clinical, serologic, and bacteriologic responses to a known inoculum. J. Infect. Dis. 129:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, H. S., and D. A. Sack. 2001. Development of a novel in vitro assay (ALS assay) for evaluation of vaccine-induced antibody secretion from circulating mucosal lymphocytes. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:482-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig, L., R. K. Taylor, M. E. Pique, B. D. Adair, A. S. Arvai, M. Singh, S. J. Lloyd, D. S. Shin, E. D. Getzoff, M. Yeager, K. T. Forest, and J. A. Tainer. 2003. Type IV pilin structure and assembly: X-ray and EM analyses of Vibrio cholerae toxin-coregulated pilus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAK pilin. Mol. Cell 11:1139-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czerkinsky, C., Z. Moldoveanu, J. Mestecky, L. A. Nilsson, and O. Ouchterlony. 1988. A novel two colour ELISPOT assay. I. Simultaneous detection of distinct types of antibody-secreting cells. J. Immunol. Methods 115:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everiss, K. D., K. J. Hughes, and K. M. Peterson. 1994. The accessory colonization factor and toxin-coregulated pilus gene clusters are physically linked on the Vibrio cholerae 0395 chromosome. DNA Seq. 5:51-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass, R. I., A. M. Svennerholm, M. R. Khan, S. Huda, M. I. Huq, and J. Holmgren. 1985. Seroepidemiological studies of El Tor cholera in Bangladesh: association of serum antibody levels with protection. J. Infect. Dis. 151:236-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall, R. H., G. Losonsky, A. P. Silveira, R. K. Taylor, J. J. Mekalanos, N. D. Witham, and M. M. Levine. 1991. Immunogenicity of Vibrio cholerae O1 toxin-coregulated pili in experimental and clinical cholera. Infect. Immun. 59:2508-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hang, L., M. John, M. Asaduzzaman, E. A. Bridges, C. Vanderspurt, T. J. Kirn, R. K. Taylor, J. D. Hillman, A. Progulske-Fox, M. Handfield, E. T. Ryan, and S. B. Calderwood. 2003. Use of in vivo-induced antigen technology (IVIAT) to identify genes uniquely expressed during human infection with Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:8508-8513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrington, D. A., R. H. Hall, G. Losonsky, J. J. Mekalanos, R. K. Taylor, and M. M. Levine. 1988. Toxin, toxin-coregulated pili, and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans. J. Exp. Med. 168:1487-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iredell, J. R., and P. A. Manning. 1994. Biotype-specific tcpA genes in Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonson, G., J. Holmgren, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1991. Epitope differences in toxin-coregulated pili produced by classical and El Tor Vibrio cholerae O1. Microb. Pathog. 11:179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonson, G., J. Osek, A. M. Svennerholm, and J. Holmgren. 1996. Immune mechanisms and protective antigens of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O139 as a basis for vaccine development. Infect. Immun. 64:3778-3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine, M. M., D. R. Nalin, M. B. Rennels, R. B. Hornick, S. Sotman, G. Van Blerk, T. P. Hughes, S. O'Donnell, and D. Barua. 1979. Genetic susceptibility to cholera. Ann. Hum. Biol. 6:369-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosley, W. H., S. Ahmad, A. S. Benenson, and A. Ahmed. 1968. The relationship of vibriocidal antibody titre to susceptibility to cholera in family contacts of cholera patients. Bull. W. H. O. 38:777-785. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosley, W. H., A. S. Benenson, and R. Barui. 1968. A serological survey for cholera antibodies in rural east Pakistan. 1. The distribution of antibody in the control population of a cholera-vaccine field-trial area and the relation of antibody titre to the pattern of endemic cholera. Bull. W. H. O. 38:327-334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosley, W. H., W. M. McCormack, A. Ahmed, A. K. Chowdhury, and R. K. Barui. 1969. Report of the 1966-67 cholera vaccine field trial in rural East Pakistan. 2. Results of the serological surveys in the study population—the relationship of case rate to antibody titre and an estimate of the inapparent infection rate with Vibrio cholerae. Bull. W. H. O. 40:187-197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson, K. M., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. Characterization of the Vibrio cholerae ToxR regulon: identification of novel genes involved in intestinal colonization. Infect. Immun. 56:2822-2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qadri, F., F. Ahmed, M. M. Karim, C. Wenneras, Y. A. Begum, M. Abdus Salam, M. J. Albert, and J. R. McGhee. 1999. Lipopolysaccharide- and cholera toxin-specific subclass distribution of B-cell responses in cholera. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6:812-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qadri, F., T. Ahmed, F. Ahmed, R. B. Sack, D. A. Sack, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2003. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral, inactivated enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli plus cholera toxin B subunit vaccine in Bangladeshi children 18-36 months of age. Vaccine 21:2394-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qadri, F., G. Jonson, Y. A. Begum, C. Wenneras, M. J. Albert, M. A. Salam, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1997. Immune response to the mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin in patients with cholera due to Vibrio cholerae O1 and O0139. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:429-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qadri, F., E. T. Ryan, A. S. Faruque, F. Ahmed, A. I. Khan, M. M. Islam, S. M. Akramuzzaman, D. A. Sack, and S. B. Calderwood. 2003. Antigen-specific immunoglobulin A antibodies secreted from circulating B cells are an effective marker for recent local immune responses in patients with cholera: comparison to antibody-secreting cell responses and other immunological markers. Infect. Immun. 71:4808-4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qadri, F., C. Wenneras, M. J. Albert, J. Hossain, K. Mannoor, Y. A. Begum, G. Mohi, M. A. Salam, R. B. Sack, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1997. Comparison of immune responses in patients infected with Vibrio cholerae O139 and O1. Infect. Immun. 65:3571-3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhine, J. A., and R. K. Taylor. 1994. TcpA pilin sequences and colonization requirements for O1 and O139 Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 13:1013-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan, E. T., J. R. Butterton, T. Zhang, M. A. Baker, S. L. Stanley, Jr., and S. B. Calderwood. 1997. Oral immunization with attenuated vaccine strains of Vibrio cholerae expressing a dodecapeptide repeat of the serine-rich Entamoeba histolytica protein fused to the cholera toxin B subunit induces systemic and mucosal antiamebic and anti-V. cholerae antibody responses in mice. Infect. Immun 65:3118-3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saha, D., R.-C. LaRocque, A. I. Khan, J. B. Harris, Y. A. Begum, S. M. Akramuzzaman, A. S. G. Faruque, E. T. Ryan, F. Qadri, and S. B. Calderwood. 2004. Incomplete correlation of the serum vibriocidal antibody titer with protection from Vibrio cholerae infection in urban Bangladesh. J. Infect. Dis. 189:2318-2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun, D. X., J. J. Mekalanos, and R. K. Taylor. 1990. Antibodies directed against the toxin-coregulated pilus isolated from Vibrio cholerae provide protection in the infant mouse experimental cholera model. J. Infect. Dis. 161:1231-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor, R. K., V. L. Miller, D. B. Furlong, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:2833-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westphal, O. J. K. 1965. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide extraction with phenol-water and further application of the procedure. Methods Carbohydr. Chem. 5:83-91. [Google Scholar]