Abstract

Metastatic prostate cancer causes significant morbidity and mortality and there is a critical unmet need for effective treatments. We have developed a theranostic nanoplex platform for combined imaging and therapy of prostate cancer. Our prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) targeted nanoplex is designed to deliver plasmid DNA encoding tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), together with bacterial cytosine deaminase (bCD) as a prodrug enzyme. Nanoplex specificity was tested using two variants of human PC3 prostate cancer cells in culture and in tumor xenografts, one with high PSMA expression and the other with negligible expression levels. The expression of EGFP-TRAIL was demonstrated by fluorescence optical imaging and real-time PCR. Noninvasive 19F MR spectroscopy detected the conversion of the nontoxic prodrug 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC) to cytotoxic 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) by bCD. The combination strategy of TRAIL gene and 5-FC/bCD therapy showed significant inhibition of the growth of prostate cancer cells and tumors. These data demonstrate that the PSMA-specific theranostic nanoplex can deliver gene therapy and prodrug enzyme therapy concurrently for precision medicine in metastatic prostate cancer.

Keywords: prostate cancer, theranostic imaging, TRAIL, gene therapy, prodrug enzyme therapy, PSMA

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer remains the second most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death among men in the United States.1, 2 In particular, there is a critical, unmet need to find effective treatments for castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Advances in theranostics, where detection is combined with therapy, are paving the way for precision medicine in cancer.3, 4 Theranostic nanoparticles are being developed in these strategies as novel platforms to target cancer cells specifically5, 6 with real-time visualization using noninvasive imaging.7–9 These theranostic nanoparticles have been developed to deliver a variety of agents,10, 11 including chemotherapy and nucleic acids such as plasmid DNA (pDNA),10–12 and small interfering RNA (siRNA).13, 14

Our purpose here was to develop a theranostic nanoplex to deliver a prodrug enzyme and pDNA expressing a gene of therapeutic interest with the ultimate goal of targeting advanced, metastatic prostate cancer (Figure 1). Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) provided an attractive target to achieve specificity to castration-resistant prostate cancer.15, 16 PSMA is a type II integral membrane protein that has abundant expression on the surface of prostate cancer, particularly in castration-resistant, advanced, and metastatic disease. Urea-based small molecule inhibitors of PSMA have been applied as targeting moieties for diagnostic imaging probes and drugs for prostate cancer.17–19 Here we used a urea-based small molecular PSMA inhibitor, (2-(3-[1-carboxy-5-[7-(2,5-dioxo-pyrrolidin-1-yloxycarbonyl)-heptanoylamino]-pentyl]-ureido)-pentanedioic acid (MW 572.56) as the targeting moiety linked to the nanoplex through a polyethyl glycol (PEG) chain for targeting PSMA.

Figure 1.

Structure of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) has attracted attention in cancer gene therapy.20, 21 The TRAIL protein belongs to the TNF cytokine superfamily. After binding with death receptors (DR4 and DR5) and decoy receptors (DcR1 and DcR2), the extrinsic apoptotic pathway is triggered by TRAIL through recruitment of the Fas-associated death domain protein to the death domain. The increased expression of death receptors in most cancer cells results in TRAIL inducing apoptosis, with minimal toxicity to normal cells.22, 23 Because the killing activity of TRAIL is cancer-specific and has little effect on most normal cells and tissues, TRAIL is being actively investigated as a promising anticancer protein against a broad range of cancer cells and tissues.24–26 However, rapid clearance in vivo has proven to be a major impediment in achieving effective therapy.27, 28 In contrast to TRAIL protein therapy, TRAIL gene therapy, where TRAIL DNA is delivered into tumor cells through a suitably designed plasmid, provides an attractive alternative through continuous production of TRAIL in situ. We used pEGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein)-TRAIL pDNA in our theranostic nanoplex. The plasmid is expressed as an EGFP-TRAIL fusion protein. The TRAIL component is the therapeutic while EGFP is used as an imaging reporter in cells and ex vivo to monitor the expression and metabolism of EGFP-TRAIL. Polyethylenimine (PEI) was used as the pDNA vector. In addition to pEGFP-TRAIL, the nanoplex delivered the prodrug enzyme bacterial cytosine deaminase (bCD), which converts 5-fluorocytosine (5-FC) to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). 5-FU is a classical chemotherapeutic agent,29, 30 and the conversion of 5-FC to 5-FU is detectable by 19F magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). Although TRAIL31, 32 and 5-FU therapy33 have been applied separately for cancer treatment, non-specific delivery, especially in the case of 5-FU, creates significant collateral damage and normal tissue toxicities. By incorporating bCD in the nanoplex, 5-FU is formed in the immediate proximity of the cancer cells. In addition, TRAIL as a monotherapy may not provide sufficient tumor control.34, 35 A combination of both strategies was therefore incorporated for effective cancer-selective therapy, to mimize damage to normal tissue, and to reduce drug resistance.36, 37 Although yeast CD (yCD) demonstrates higher activity in converting convert 5-FC to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), the higher stability of bCD38 made it an attractive choice for nanoplex synthesis. We used Cy5.5 as the fluorescent moiety of the nanoplex. Due to its emission in the near-infrared (NIR) region (680 – 900 nm) of the electromagnetic spectrum, Cy5.5 enables in vivo optical imaging because of limited auto-fluorescence at these wavelengths. Noninvasive, in vivo, real-time imaging of Cy5.5 was used to detect the temporal and spatial distribution of the nanoplex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All organic chemicals and solvents of analytical grade were from Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Sigma (Milwaukee, WI) unless otherwise specified. N-succinimidyl-S-acetylthiopropionate (SATP), N-[e-maleimidocaproyloxy)-succinimide ester (EMCS), succinimidyl 4-formylbenzoate (SFB) and succinimidyl 6-hydrazinonicotinamide acetone hydrazine (SANH) were obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Maleimide-PEG-NH2 (3.4 kDa) was procured from Nanocs (New York, NY). pEGFP-TRAIL and pEGFP-U6 plasmids were purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA).

Determination of Size Distribution and Zeta Potential of PSMA-targeted Nanoplex 1

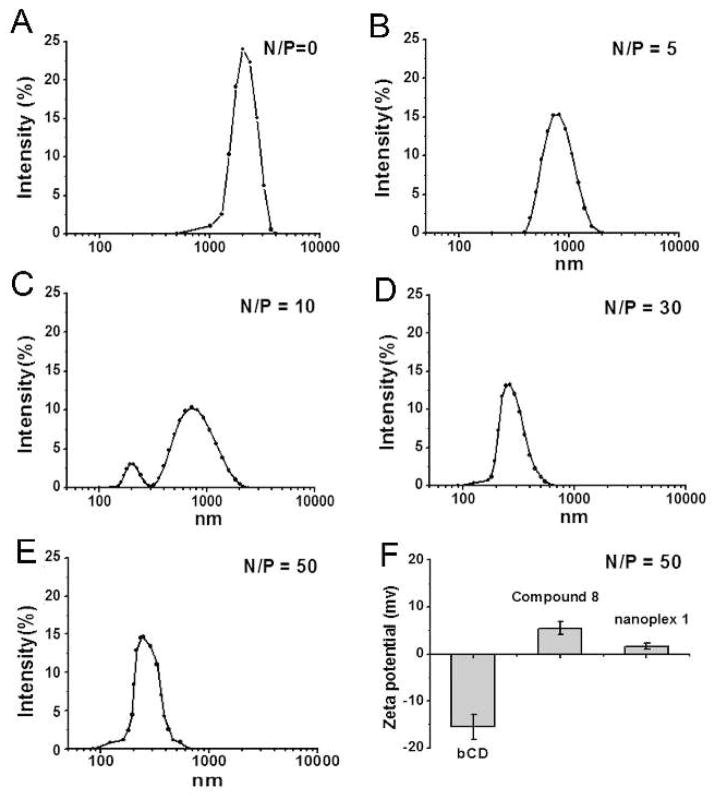

The hydrodynamic radius and size distribution of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS, 10 mW He-Ne laser, 633 nm wavelength). PSMA-targeted Nanoplex 1 was prepared at varying N/P ratios of 5, 10, 30, and 50 by adding a PBS buffer solution (20 mM, pH 7.4) of compound 8 (600 μL, varying concentrations) to a distilled water solution of pDNA (400 μL, 400 μg/mL), followed by vortexing for 5 s and incubating for 10 min at room temperature. The DLS measurements were performed in triplicate. The average zeta potential of bCD alone, compound 8 (carrier alone) and PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 (N/P = 50) in deionized water were measured with a Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern) equipped with a clear standard zeta capillary electrophoresis cell cuvette from 20 acquisitions with a concentration of approximately 1 mg/mL. The measurements were performed in triplicate.

Cell Culture

Human prostate cancer PC3 cells transfected to overexpress PSMA (PC3-PIP) or transfected with the plasmid alone (PC3-Flu) were obtained from Dr. Warren Heston (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH). Fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a humidified incubator at 37°C/5% CO2.

In vitro Cell Culture Studies

In vitro therapeutic efficacy of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 was evaluated in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells by an MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay (Sigma, Milwaukee, WI). PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells (8 × 103 cells/well) in 96-well plates were incubated for 24 hours in RPMI 1640 in a humidified environment with 5% CO2 at 37 °C prior to treatment. To evaluate the efficacy of TRAIL gene therapy, cells were treated with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 (concentration of pDNA: 2 μg/ml, N/P = 50). To test the therapeutic efficacy of the 5-FC/bCD strategy, cells were treated with 5-FC (3 mM) and PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 in which the pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA was replaced with pEGFP-U6 pDNA (concentration of pDNA: 2 μg/ml, N/P = 50). To evaluate the combined therapeutic efficacy of TRAIL gene therapy and 5-FC/bCD strategy, cells were treated with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 (concentration of pDNA: 2 μg/ml, N/P = 50) with the addition of 5-FC (3 mM). The cells were further incubated for 24 and 48 hours at 37 °C. The MTT reagent (in 20 μL PBS, 5 mg/mL) was then added to each well. The cells were further incubated for 5 hours at 37 °C. After incubation, 100 μL sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution (10 mg/mL) was added in each well, and the plates were kept in dark overnight. The absorbance (A) at 490 nm was recorded by a microplate reader (Bio-rad, USA). The cell viability (y) was calculated by y=(Atreated/Acontrol)×100%, where Atreated and Acontrol are the absorbance of the cells cultured with treatment and fresh culture medium, respectively.

In Vitro Transfection

Transfection efficiency of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 with pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA was tested in PC3-PIP and PC3-flu cells. Cells were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells per dish in 6 cm dish (for RT-PCR experiments) or 8,000 cells per well in 8 wells slide chamber (for confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy studies) 24 hours prior to the transfection experiment. The RPMI 1640 medium solution of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 (concentration of pDNA: 2 μg/ml, N/P = 50), prepared as previously described, was added to each well or dish. After 8 hours incubation, the transfection mixture was removed and the cells were collected for further experiments.

Confocal Laser Scanning Fluorescence Microscopy

PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells in 8 well chamber slides were treated with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 and non-PSMA-targeted nanoplex (concentration of pDNA: 2 μg/ml, N/P = 50) for 8 hours. After incubation, the transfection mixture was removed, and cells were washed twice with fresh medium. Fluorescence microscopy images of PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells were generated on a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc. Oberkochen, Germany). The expression of EGFP-TRAIL was visualized by 488-nm excitation and the corresponding emission acquired in the 495–650 nm range at 5-nm wavelength resolution.

Mouse Model and Tumor Implantation

All in vivo studies were carried out in compliance with guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Johns Hopkins University. Mice were purchased from Charles River (Frederick, MD). PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu human prostate cancer cells (2 × 106 cells/mouse) were inoculated subcutaneously in male severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice (SCID/NCr, strain code: 561). Tumors were palpable within one week after implantation and reached a volume of approximately 300 to 400 mm3 within three weeks, at which time they were used for the studies.

In Vivo and Ex Vivo Optical Imaging Studies

In vivo and ex vivo optical images were acquired with a Xenogen IVIS Spectrum scanner (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA), and fluorescence intensities in regions of interest (ROIs) were quantified by using Living Image 2.5 software (Caliper, Hopkinton, MA). For in vivo optical imaging of the distribution of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1, PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumor bearing mice were injected intravenously (IV.) with nanoplex (150 mg/kg in 0.2 ml saline). The images were obtained at 24, 48 and 72 hours after injection. Mice were sacrificed at 72 hours after nanoplex injection for ex vivo imaging studies, and tumors and muscle were excised to obtain the optical images. Tumor tissues were cut into 2 mm thick slices for ex vivo fluorescence imaging studies of EGFP. Cy5.5 fluorescence images were acquired using λex = 615–665 nm and λem = 695–770 nm filter set, 1 s exposure time, and the fluorescence intensity was scaled as units of ps−1cm−2sr−1. A GFP excitation (445–490 nm)) and emission (515–575 nm) filter set (1 s exposure time) was used to acquire the green fluorescence images of EGFP-TRAIL.

RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis and Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from snap frozen PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors or cells grown in 60mm dish that were seeded at 3×105 using QIAshredder and RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was prepared using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). cDNA samples were diluted 1:10 and real-time PCR was performed using IQ SYBR Green supermix and gene specific primers in the iCycler real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The following primers against (a)TRAIL (NM_001190942)- FWD-5′-ttaccaacgagctgaagcag-3′ and Rev-5′-tggggtcccaataactgtcatc-3′, (b) EGFP-Fwd- 5′-agctgaccctgaagttcatctg-3 and Rev- 5′-aagtcgtgctgcttcatgtg-3′ and (c) HPRT1- the house keeping gene- Fwd- 5′-CCTGGCGTCGTGATTAGTGATG-3′ and Rev- 5′-CAGAGGGCTACAATGTGATGGC-3′ were designed using either Beacon designer software 7.8 (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA) or a free web-based software Primer3Plus software39 and were synthesized and obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa). The expression of target RNA relative to the housekeeping gene HPRT1 was calculated based on the threshold cycle (Ct) as R = 2- ( Ct), where Ct= Ct of target - Ct of HPRT1.

In Vivo 19F MRS

PC3-PIP tumor bearing mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (25 mg/kg) and acepromazine (2.5 mg/kg) injected IP before all MR studies. Anesthetized mice were imaged on a 9.4 T Bruker Biospec spectrometer (Bruker Biospin Co., Billerica, MA) using a solenoid coil placed around the tumors. Body temperature of the animals in the magnet was maintained by a thermostat-regulated heating pad. All 19F MRS experiments were done using a solenoid coil tunable to 1H or 19F frequency. Typically, after injection of 5-FC (450 mg/kg), anesthetized mice (n = 3) were placed on a plastic cradle to allow positioning of the tumor in the RF coil. Following shimming on the water proton signal, serial 19F nuclear MR spectra were acquired from the tumor every 30 min for 110 min using a one-pulse sequence (flip angle, 60°; repetition time, 0.8 s; number of average, 2000; spectral width, 10 kHz). 19F MR spectra were processed with an in-house XsOs nuclear magnetic resonance software developed by Dr. D. Shungu (Cornell University, New York, NY). The chemical shift of the 5-FU resonance was set to 0 ppm.

Tumor Growth Inhibition Study and Histological Evaluation

PC3-PIP tumor bearing SCID mice were used to evaluate tumor growth inhibition. When tumor sizes reached 60~70 mm3, the mice were divided into four groups (3 mice per group) randomly, and the following treatments were applied: (a) treatment with saline as control; (b) treatment with nanoplex 1 (100 mg/kg) containing pEGFP-TRAIL DNA; (c) treatment with nanoplex 1 (100 mg/kg) containing pEGFP-U6 DNA and 5-FC (i.v. and i.p. injection, 450 mg/kg); (d) treatment with nanoplex 1 (100 mg/kg) containing pEGFP-TRAIL DNA and 5-FC (i.v. and i.p. injection, 450 mg/kg). The tumor volumes of mice were measured at 3, 6, 8, and 10 days after treatment. The fold increase in average tumor size was obtained by normalizing the tumor volume over the course of the experiment to the initial tumor volume at day zero. At 10 days after treatment, mice were sacrificed for H&E staining histological studies. The tumors were fixed in formalin, sectioned at 5μm thickness, and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images of H&E stained slides were obtained by Aperio ScanScope® CS System at 20× resolution. Necrotic cells were identified by pyknotic nuclei or lack of nuclei that resulted in a decrease of purple staining of chromatin by hematoxylin, leaving a primarily pale pink eosinophilic staining of the cytoplasm in necrotic areas. Adjacent 5μm section was stained for proliferation marker Ki-67 (rabbit polyclonal, Cat. Number-PA1-38032, Thermo Fisher, Rockford, IL, 1:100 dilution) for two hours at room temperature following standard tissue processing. Antigen retrieval was accomplished by boiling the section in citrate buffer solution (pH 6) for twenty minutes, and further processed by addition of biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and ABC reagent (PK-4001, Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Finally, detection was achieved by addition of the chromogen DAB (3, 3′-diaminobenzidine, Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Images were captured by scanning the immunostained sections at high resolution on Aperio ScanScope (Leica Biosystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL).

RESULTS

Preparation and Characterization of PSMA-Targeted Nanoplex 1

The synthesis of the nanoplex is briefly outlined in Figure 2. The bCD was produced as previously described.40 An N-hydroxysuccinamide (NHS) ester of the low-molecular-weight, urea-based PSMA inhibitor (PI) (2-(3-(1-carboxy-5-(7-(2,5-dioxo-pyrrolidin-1-yloxycarbonyl)-heptanoylamino)-pentyl)-ureido)-pentanedioic acid), was used as a precursor for the PSMA-targeting moiety, as previously described.40, 41 PI-NHS was conjugated with maleimide-PEG-NH2 (3.4 kDa) (Nanocs. Inc., NY) to form PI-PEG-maleimide. N-succinimidyl-S-acetylthiopropionate (SATP) was conjugated to PEI (Sigma Milwaukee, WI) (25 kDa) at a SATP/PEI molar ratio of 12:1 followed by reduction of the SATP moiety to the thiol. Reaction between the thiol and PI-PEG-maleimide generated PI-PEG-PEI (compound 2). Compound 2 was labeled with Cy5.5-NHS (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) to form compound 3. Compound 3 was conjugated with succinimidyl 4-formylbenzoate (SFB) in HEPES buffer at pH 8.4 to form compound 4. PLL (poly-L-lysine) (Sigma Milwaukee, WI) (~6 kDa) was conjugated with SATP and succinimidyl 6-hydrazinonicotinamide acetone hydrazine (SANH) to produce compound 5. Conjugation of 4 and 5 at pH 7.4 produced the PEI-PLL copolymer, which was reduced by NH2OH to form 6. Treatment of bCD with N-[e-maleimidocaproyloxy)-succinimide ester (EMCS) produced 7. Equimolar amounts of 6 and 7 were cross-linked through the reaction of maleimide and sulfydryl to obtain 8, which was the pDNA vector. Finally, treatment of pEGFP-TRAIL with 8 gave the PSMA-specific PI-PEI-PLL-bCD/DNA nanoplex 1.

Figure 2.

Synthetic procedure of generating PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1.

NMR spectroscopy indicated that the PI and PEG were conjugated to PEI in a PEG/PEI molar ratio of 11:1. After we obtained compound 8, the amounts of PEI and bCD were measured through the absorption coefficients of Cy5.5 (on PEI) and bCD, and the final molar ratio of bCD and PEI was 1.05:1. Size exclusion chromatography (Figure S4) demonstrated that the molecular weight of 8 was ~ 370 kDa. Following the binding of 8 with pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA (5607 bp), the hydrodynamic radius and zeta-potential of nanoplex 1 were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Figure 3). The size of free pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA was over 1 μm in water. With the addition of 8, the size of the PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 decreased, depending upon the N/P ratio. When the N/P ratio was increased to 30, the size of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 was reduced to ~ 230 nm. The size distribution did not change with increasing N/P ratio for ratios of 30 or higher. We used an N/P ratio of 50 to improve transfection.42 The size of nanoplex 1 was confirmed by TEM as shown in Figure S5. To evaluate the effect of structural modification on the activity of bCD, enzymatic activity was determined using cytosine and 5-FC as substrates. Rate constants were determined by monitoring changes in the absorbance of cytosine and 5-FC at saturating substrate concentrations, as reported previously by us40. A similar Km of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 and free bCD for both substrates (Table S1 and S2) indicated that structural modification of bCD had only a slight effect on the function of bCD.

Figure 3.

A-E. Distribution of the hydrodynamic radius of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 at different N/P ratios. F. Average zeta potential of bCD, PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 without pEGFP-TRAIL DNA (compound 8) and PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 (N/P = 50). Values represent mean ± SEM of three measurements.

In Vitro Expression and Cytotoxicity of PSMA-Targeted Nanoplex 1

Cell viability and imaging studies with the PSMA-targeted nanoplex were performed with PC3 human prostate cancer cells genetically engineered to overexpress PSMA (PC3-PIP). Low-PSMA expressing PC3 cells (PC3-Flu) were used as controls. The pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA was expressed as the EGFP-TRAIL fusion protein, with the green fluorescence of this protein used to detect protein expression levels. Detection of expressed EGFP-TRAIL protein was performed with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Figure 4). After eight hours of incubation, strong green fluorescence was only observed in PC3-PIP cells that were treated with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 (Figure 4A). Weak green fluorescence was observed in PC3-PIP cells treated with non-PSMA-targeted nanoplex (structure shown in Figure S3) that only lacked the PSMA targeting moiety (Figure 4B). Green fluorescence in PC3-Flu cells was weak, with (Figure 4C) or without (Figure 4D) the PSMA targeting moiety.

Figure 4.

A-D. Laser confocal fluorescence microscopy of PC3-PIP (PSMA+ve) and PC3-Flu (PSMA−ve) cells. A. PC3-PIP cells treated with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1; B. PC3-PIP cells treated with non-PSMA-targeted nanoplex; C. PC3-Flu cells treated with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1; D. PC3-Flu cells treated with non-PSMA-targeted nanoplex. (DIC: differential interference contrast imaging; treatment time: 8 hours; concentration of pDNA: 2 μg/mL; N/P ratio: 50; scale bar: 50 μm).

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed to measure EGFP-TRAIL mRNA expression in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells following treatment with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5A, mRNA levels of EGFP and TRAIL were much higher in PC3-PIP than in PC3-Flu cells. Fold-mRNA expression of EGFP and TRAIL relative to the housekeeping gene HPRT1 in PC3-Flu cells were ~ 3.2 × 103 and 5 × 103 respectively, whereas in PC3-PIP cells these were ~ 2.8 × 105 and 2.7 × 105 respectively. The in vitro therapeutic efficacy of pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA alone, 5-FC conversion to 5-FU by bCD alone, and combination therapy of pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA with 5-FC conversion to 5-FU by bCD, in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells are presented in Figures 5B and C. With vector (compound 8) alone, the cell viabilities of PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu were above 90% after 24 and 48 hours of treatment. When PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 that contained pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA was used, it was clearly evident that the viability of PC3-PIP cells (about 40%) was significantly lower than PC3-Flu cells (about 90%) at 24 and 48 hours of treatment, confirming increased formation of TRAIL in PC3-PIP cells. Because the nanoplex in the medium contained bCD, the 5-FU formed when 5-FC was added to the medium caused a significant decrease of cell viability of both PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells even without TRAIL. This effect of 5-FU also outweighed the effect of TRAIL resulting in a similar decrease of viability in both PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells when pEGFP-TRAIL was present in addition to bCD. The efficacy of combination therapy, however, was better than that of TRAIL pDNA or 5-FC/bCD alone.

Figure 5.

A. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR mRNA expression of PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells following treatment with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 for eight hours (concentration of pDNA: 2 μg/mL; N/P ratio: 50; without 5-FC/bCD treatment; ** P < 0.01; bars are SD). B. and C. Cell viability of PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells with different treatments. Cells were treated for 24 and 48 hours (concentration of pDNA: 2 μg/ml; N/P ratio: 50; concentration of 5-FC: 3mM; values are generated from two separate experiments with three wells per experiment per condition; ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05, bars are SD).

Specific Uptake of PSMA-Targeted Nanoplex 1 in PSMA Overexpressing Tumors

In vivo Cy5.5 fluorescence optical images obtained from severe combined SCID mice bearing PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors were used to evaluate the accumulation of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 (Figure 6A). At 24 hours after injection, the accumulation of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 in PC3-PIP tumors was 230% higher than in PC3-Flu tumors. With time, the accumulation of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 decreased, but even at 72 hours after injection, accumulation in PC3-PIP tumors was 90% higher than in PC3-Flu tumors. We also observed significant accumulation of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 in the liver. To confirm uptake specificity, we measured ex vivo Cy5.5 fluorescence in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors and in muscle (Figure 6B). At 72 hours after injection, ex vivo images revealed a significantly higher uptake of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 in PC3-PIP tumors compared to PC3-Flu tumors. When the non-PSMA-targeted nanoplex was injected we observed comparable fluorescence intensities of Cy5.5 in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors. Quantification of the data from the ex vivo imaging studies are presented in Figure 6C. These results indicate that the difference between the integrated fluorescence intensity of PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors was significantly different only following injection of the PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1, but not following injection of the non-PSMA-targeted nanoplex.

Figure 6.

A. Representative longitudinal in vivo Cy5.5 NIR fluorescence optical images of SCID mice bearing PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors. Mouse was injected IV. with nanoplex (150 mg/kg in 0.2 mL saline). B. Ex vivo Cy5.5 NIR fluorescence optical imaging of PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors. Mouse was injected IV. with nanoplex (150 mg/kg in 0.2 mL saline). C. Quantification of Cy 5.5 fluorescence intensity in ex vivo imaging study. (** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05, bars are SEM, n = 3). D. In vivo 19F MR spectra acquired from a PC3-PIP tumor (~400 mm3) at 24 hours after IV. injection of the PSMA-targeted nanoplex (100 mg/kg) carrying bCD. Spectra were acquired after a combined IV. and IP. injection of 5-FC (450 mg/kg), on a Bruker Biospec 9.4 T spectrometer using a 1 cm solenoid coil tunable to 1H and 19F frequency. Following shimming on the water proton signal, serial nonselective 19F MR spectra were acquired starting 20 min after the 5-FC injection and continued every 30 min for 110 min with a repetition time of 0.8 s, a number of scans of 2,000, and a spectral width of 10 KHz.

Non-invasive 19F MRS (Figure 6D) was performed to monitor the in vivo conversion of 5-FC to 5-FU that was formed by the bCD enzymatic activity of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1. Nanoplex 1 displayed high enzymatic activity at 24 hours after injection. As shown in Figure 6D, at 20 minutes after injection of 5-FC there was a strong signal from 5-FC, and a small signal from 5-FU. With time the intensity of the 5-FU peak slowly increased together with a decrease of the 5-FC peak. At 140 minutes after injection of 5-FC, it was apparent that the 5-FU peak was much higher than 5-FC peak, indicating that most of the 5-FC had been converted to 5-FU.

In Vivo Expression of EGFP-TRAIL Protein

Real time PCR studies of mRNA expression were performed to investigate the expression of EGFP-TRAIL mRNA in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors (Figure 7A). In these studies pEGFP-U6 pDNA that had a similar size (5,000 kb) as pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA, but only expressed EGFP was used as a positive control. In the untreated control mice, both EGFP and TRAIL mRNA in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors were within background levels. The ratio of PC3-PIP to PC3-Flu mRNA in these tumors was ~1. When we used PSMA-targeted pEGFP-TRAIL and investigated TRAIL expression, the ratio of PC3-PIP to PC3-Flu tumor TRAIL mRNA was significantly higher compared to pEGFP-U6 treatment and non-treatment control. With PSMA-targeted pEGFP-TRAIL treatment, TRAIL mRNA levels in PC3-PIP tumors were twice as high as in PC3-Flu tumors. With PSMA-targeted pEGFP-U6 treatment, TRAIL mRNA levels in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors were comparable. EGFP mRNA was over two-fold higher in PC3-PIP tumors compared to PC3-Flu tumors with both PSMA-targeted pEGFP-U6 treatment and PSMA-targeted pEGFP-TRAIL treatment. Optical imaging of EGFP detected the expression of pEFGP-TRAIL fusion protein ex vivo (Figure 7B). At 72 hours after injection of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1, green fluorescence was detected in PC3-PIP tumor slices, but not in PC3-Flu tumor slices.

Figure 7.

A. Real time PCR mRNA expression studies of PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors with different treatments (control: non-treatment as the negative control; pEGFP-U6: PSMA-targeted pEGFP-U6 pDNA treatment as the positive control; pEFGP-TRAIL: PSMA-targeted pEFGP-TRAIL pDNA treatment). Tumor tissue was collected at 24 hours after mice were injected with PSMA-targeted nanoplex carrying pEGFP-U6 or pEGFP-TRAIL (dosage of DNA: 3.2 mg/kg; N/P ratio: 50; ** P < 0.01, bars represent SD, n = 3 or 4). B. Ex vivo EGFP fluorescence images of PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumor slices at 72 hours after treatment.

In Vivo Real-Time Noninvasive Imaging of Therapeutic Efficacy of PSMA-Targeted Nanoplex 1

We investigated the in vivo therapeutic efficacy of PSMA-targeted TRAIL pDNA treatment, PSMA-targeted 5-FC/bCD treatment, and the combination of PSMA-targeted TRAIL and 5-FC/bCD treatment in mice bearing PC3-PIP tumors (Figure 8A). With saline-treatment, tumor volumes increased to ~220% that of day 0 at 3 days after injection. In contrast, there was only a 20–30% increase of tumor volumes in mice with different treatments, and the three different treatments demonstrated similar therapeutic efficacy at this time point. At 6, 8 and 10 days after injection, tumor sizes in the mice with PSMA-targeted TRAIL pDNA treatment alone increased significantly, and there was no significant difference between the therapeutic efficacy of saline and PSMA-targeted TRAIL pDNA treatment alone. However, 5-FC/bCD treatment alone and the combination treatment of PSMA-targeted TRAIL pDNA and 5-FC/bCD demonstrated similar effects in growth control in PC3-PIP tumors.

Figure 8.

A. Inhibition of PC3-PIP tumor growth with different treatment (tumor volume was normalized to the pretreatment volume, values represent median ± SD (n =3 or 4), following a combined IV. and IP. injection of 5-FC (450 mg/kg) at 24 hours after IV. injection of the PSMA-targeted nanoplex (100 mg/kg). B. Representative high-resolution scanned images of H&E stained histological sections obtained at 10 days post treatment with NaCl solution, PSMA-targeted pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA only, PSMA-targeted 5-FC only, and combination of PSMA-targeted pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA and 5-FC. Purple hematoxiphilic regions indicate viable tumor tissues, and eosinophilic areas indicated tumor necrosis. C. Representative high-resolution scanned images of Ki-67 immunostained adjacent sections corresponding to the sections in B. Scale bar: 3.0 mm.

As shown in Figure 8B, the therapeutic response was additionally evaluated by histology in PC3-PIP tumors 10 days after treatment. Figure 8B-1 demonstrates the absence of gross necrosis in control tumors mice injected with saline. In the case of PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy alone treatment (Figure 8B-2), there was a slight increase of gross necrosis. In contrast, large necrotic areas were observed in the PC3-PIP tumors treated with 5-FC/bCD therapy alone (Figure 8B-3) and combination therapy (TRAIL pDNA and 5-FC/bCD) group (Figure 8B-4). Proliferating cells were absent or very low in the necrotic areas of the treated tumors as shown in the corresponding magnified Ki-67 immunostained sections (Figure 8C 1–4), in contrast to the non-necrotic saline treated control tumor that had uniformly stained Ki-67 cells.

DISCUSSION

We have generated a PSMA-specific theranostic nanoparticle that combined TRAIL gene therapy and 5-FC/bCD therapy that showed PSMA-specific retention and therapeutic effect in prostate cancer cells and xenografts. Optical imaging demonstrated that the theranostic nanoplex accumulated in PC3-PIP cells and tumors. Encapsulated pDNA expressing TRAIL was released and translocated to the nucleus,43 resulting in the formation of TRAIL that induced apoptosis. The combination of TRAIL gene therapy and 5-FC/bCD therapy achieved significant tumor growth delay and extensive tumor necrosis.

The introduction of polyethylenimine (PEI) as a non-viral vector represents an advantage because of its higher efficiency in promoting gene transfection such as pDNA and siRNA.44, 45 The strong positive charge on PEI can induce severe toxicity, and the aggregation of the bCD protein can result in the failure of the nanoplex synthesis. The use of PEG to shield the strong positive charge of PEI is important to eliminate toxicity and for the efficient nanoplex synthesis. However excess PEG may reduce the binding ability of the nanoplex to DNA or siRNA. We previously optimized the PEG-PEI ratio and determined that a ratio of 11:1 eliminates toxicity but maintains optimum binding of molecular reagents.46 We previously evaluated the immune response of this nanoplex carrier with a PEG-PEI ratio of 11:1 in immune competent mice, and did not detect a measurable immune response.40

Several factors can affect the DNA/PEI complex formation such as PEGylation, shape and length of PEI chain, and the uncomplexed free PEI chain.42, 47, 48 Significant effort was devoted to optimize the structure of the DNA/PEI nanoplex for better stability and transfection efficiency. The 3.4 KDa PEG and a PEG/PEI ratio of 11:1 were applied in the PEGylation of our PEI nanoplex vector (compound 8). The PEG chain is required to separate the targeting moiety from the nanoplex so that it can reach the deep docking site within PSMA, and bind with Zn2+ at the active site. Although the gel-shift assay indicated that the pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA bound completely with the vector (compound 8) at an N/P ratio of 15, the size distribution study indicated that an N/P ratio of 15 was not optimal. The free pDNA had a large size in water due to its loosened shape that was confirmed by the size distribution studies that measured the radius of free pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA to be over 1000 nm. Since the large size of free pDNA prevented it from entering the cells and tumors efficiently, a reduction of pDNA size was essential for efficient transfection. Polymers with positive charges can bind with pDNA through electrostatic interaction, which causes condensation and complexation of DNA and reduces the size of DNA/polymer complex. For this reason, our size distribution studies indicated that the size of nanoplex 1 decreased with increasing N/P ratio. Although the DNA bound with the vector completely at an N/P ratio of 15, the size of nanoplex 1 at this N/P ratio was still too large to enter cells and tumors. Nanoplex 1 achieved a minimal radius of ~230 nm at an N/P ratio of 30 that permitted the nanoplex to enter cells and tumors relatively easily.49 When the N/P ratio was over 30, the size of nanoplex 1 did not change with increasing of N/P ratio. Because the uncomplexed free polymer chains with positive charges were able to improve gene transfection,42 we used an N/P ratio of 50 in our studies to improve transfection efficiency.

A small molecule based on the glutamate-urea-X (X is an α-amino acid derivative) was used as the PSMA-targeting moiety of our nanoplex platform. PSMA, our chosen target, is being widely investigated for diagnostic imaging of prostate cancer. Although the nanoplex can enter cells through endocytosis, which caused the low levels of non-PSMA-specific EGFP-TRAIL expression, our in vitro EGFP-TRAIL expression studies demonstrated that the PSMA targeting moiety was able to improve the transfection efficiency through the enhancement of the uptake of the nanoplex in PC3-PIP cells with high PSMA expression. The transfection efficiency was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy of EGFP expression and by RT-PCR measurements of mRNA levels. Both demonstrated specific expression of EGFP-TRAIL, although the fold changes were different. By counting cells with green fluorescence (Table S3), we found the transfection efficiency with PSMA-targeting was four times as high as that without PSMA-targeting. The PCR studies indicated mRNA levels of TRAIL and EGFP in PC3-PIP cells were over 50 times higher than those in PC3-Flu when the cells were treated with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1. Microscopy detected protein expression and the number of cells expressing GFP, whereas RT-PCR measured mRNA levels.

Although the nanosized complex accumulated in tumors through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect,50 we observed increased retention of the PSMA-targeted nanoplex in PSMA over-expressing PC3-PIP tumors that was detected in vivo and ex vivo with NIR Cy5.5 fluorescence imaging. Recent studies have reported the presence of PSMA on human tumor neovasculature although this has not been shown in mouse vasculature that forms in human tumor xenografts in mice.51 Because we prepared the PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 and non-PSMA-targeted nanoplex in different batches we were not able to incorporate the same quantities of Cy5.5. As a result, a comparison of imaging intensities following treatment with PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 and non-PSMA-targeted nanoplex was not feasible. The in vivo EGFP-TRAIL expression studies, detected higher mRNA level of EGFP and TRAIL in PC3-PIP, compared to PC3-Flu tumors, providing further evidence of the PSMA-specificity of nanoplex 1. The pEGFP-U6 pDNA was used as a positive control. With treatment of pEGFP-U6, we did not find a difference in the expression of TRAIL in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu tumors, which proved our vector did not induce additional expression of TRAIL. The green fluorescence detected in PC3-PIP tumor slices compared to the dark PC3-Flu tumor slices, provided visual confirmation of EGFP expression. These in vivo EGFP-TRAIL expression studies also confirmed that our PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 entered tumor cells efficiently, and did not remain only in the tumor microenvironment.

A high concentration of the nanoplex was observed in the liver. The liver is uniquely equipped to clear 5-FU and because TRAIL does not induce normal cell death, this nanoplex with the components used here did not present significant toxicity issues for the liver. We previously evaluated alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen measurements of this nanoplex carrier and did not detect liver toxicity.40 In contrast, viral vectors that are used in gene therapy can induce an immune response and insertional mutagenesis in normal tissues or organs.52

The therapeutic efficacy of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 was investigated in cultured cells and in tumors. In culture, PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy was effective against PC3-PIP prostate cancer cells. Combination treatment with PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy and 5-FC/bCD was more effective than PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy or 5-FC/bCD alone. A significant difference between the therapeutic efficacy in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells was only observed with the PSMA-targeted pEGFP-TRAIL pDNA treatment. The more effective inhibition of PC3-PIP cell growth confirmed that PSMA-targeting enhanced cell uptake of the nanoplex in a PSMA-dependent manner. When 5-FC was added, the cytotoxicity of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 in PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells was similar. This comparable cytotoxicity was because the bCD prodrug enzyme in nanoplex 1 functioned well in cell culture medium and converted 5-FC to 5-FU not only in cells but also in the medium. PSMA-specificity enhanced the cell uptake of nanoplex 1 but did not provide a significant advantage in terms of cell viability, in PC3-PIP cells because of bCD in the medium. Because the therapeutic efficacy of 5-FC/bCD treatment was much better than that of TRAIL gene treatment, there were no significant differences between the viabilities of PC3-PIP and PC3-Flu cells with the combination of TRAIL gene therapy and 5-FC/bCD therapy.

PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy, 5-FC/bCD therapy, and combination therapy all showed tumor growth inhibition of PC3-PIP tumors in vivo. In vivo, because 5-FC was converted to 5-FU irrespective of whether the nanoplex was intracellular or extracellular, better therapeutic efficacy of PSMA-targeted 5-FC/bCD therapy was observed compared to PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy alone that killed cancer cells only after cellular internalization. The large size of nanoplex 1 may have resulted in a heterogeneous and limited delivery in vivo. Therefore the therapeutic efficacy of PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy alone was not as good as the PSMA-targeted 5-FC/bCD therapy and combination therapy. Significant inhibition of tumor growth with PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy was only observed at 3 days after treatment. It is also possible that cells with TRAIL internalized underwent apoptosis and subsequent tumor growth was from cells not containing TRAIL DNA. Tumor growth inhibition was clearly demonstrated with the combination of PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy and 5-FC/bCD therapy at all time points after treatment. Although PSMA-targeted TRAIL gene therapy was less effective, compared to PSMA-targeted 5-FC/bCD therapy, the combination of both can provide a potential strategy to overcome drug resistance. The imaging reporter on PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 allows the 5-FC injection to be timed during maximum retention in the tumor compared to normal tissues. Effective delivery of PSMA-targeted nanoplex 1 to prostate cancer cells with PSMA expression provides a method for enhancing therapy efficacy and reducing collateral damage to normal tissues.

CONCLUSION

We successfully constructed a prostate cancer targeted theranostic nanoplex that combined TRAIL pDNA gene therapy and prodrug enzyme treatment. In these proof-of-principle studies, the PSMA-targeted nanoplex that we have developed, and which carries imaging reporters together with a PSMA targeting moiety, represents a novel approach in theranostic imaging of metastatic prostate cancer for precision medicine. The approach can be expanded as a platform technology to carry a mixture of pDNA and targeted to other antigens and receptors for different cancers types. The combination of TRAIL gene therapy and 5-FC/bCD treatment demonstrated significant therapeutic effect. In the future, this theranostic nanoplex platform can be extended to combine varieties of therapeutic pDNA and prodrug enzymes with the goal of increasing treatment efficacy, and minimizing damage to normal tissue in precision medicine strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH P50 CA103175, R01 CA138515 and R01 CA134675. We thank Ms. F. Wildes, Ms. Y. Mironchik, and Mr. G. Cromwell for valuable technical support. We thank Dr. Cong Li for useful discussions. We gratefully acknowledge the support of Dr. J. S. Lewin.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Salinas CA, Tsodikov A, Ishak-Howard M, Cooney KA. Prostate cancer in young men: an important clinical entity. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:317–323. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson IM, Jr, Cabang AB, Wargovich MJ. Future directions in the prevention of prostate cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:49–60. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chauhan VP, Jain RK. Strategies for advancing cancer nanomedicine. Nat Mater. 2013;12:958–962. doi: 10.1038/nmat3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng CJ, Saltzman WM. Nanomedicine: Downsizing tumour therapeutics. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7:346–347. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koo H, Huh MS, Sun IC, Yuk SH, Choi K, Kim K, Kwon IC. In vivo targeted delivery of nanoparticles for theranosis. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1018–1028. doi: 10.1021/ar2000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang Y, He S, Cao W, Cai K, Liang XJ. Biomedical nanomaterials for imaging-guided cancer therapy. Nanoscale. 2012;4:6135–6149. doi: 10.1039/c2nr31715j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi KY, Liu G, Lee S, Chen X. Theranostic nanoplatforms for simultaneous cancer imaging and therapy: current approaches and future perspectives. Nanoscale. 2012;4:330–342. doi: 10.1039/c1nr11277e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tassa C, Shaw SY, Weissleder R. Dextran-coated iron oxide nanoparticles: a versatile platform for targeted molecular imaging, molecular diagnostics, and therapy. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:842–852. doi: 10.1021/ar200084x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoo D, Lee JH, Shin TH, Cheon J. Theranostic magnetic nanoparticles. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:863–874. doi: 10.1021/ar200085c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin SY, Feng J, Rong L, Jia HZ, Chen S, Liu XJ, Luo GF, Zhuo RX, Zhang XZ. Theranostic GO-based nanohybrid for tumor induced imaging and potential combinational tumor therapy. Small. 2014;10:599–608. doi: 10.1002/smll.201301613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao D, Li J, Xiao X, Zhang M, Pan Y, Li S, Wang Z, Zhang X, Zheng H, Zhang X, Chen L. Real-time visualizing and tracing of HSV-TK/GCV suicide gene therapy by near-infrared fluorescent quantum dots. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:11082–11090. doi: 10.1021/am503998x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu G, Zheng J, Song E, Donovan M, Zhang K, Liu C, Tan W. Self-assembled, aptamer-tethered DNA nanotrains for targeted transport of molecular drugs in cancer theranostics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7998–8003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220817110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shrestha R, Elsabahy M, Luehmann H, Samarajeewa S, Florez-Malaver S, Lee NS, Welch MJ, Liu Y, Wooley KL. Hierarchically assembled theranostic nanostructures for siRNA delivery and imaging applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:17362–17365. doi: 10.1021/ja306616n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taruttis A, Lozano N, Nunes A, Jasim DA, Beziere N, Herzog E, Kostarelos K, Ntziachristos V. siRNA liposome-gold nanorod vectors for multispectral optoacoustic tomography theranostics. Nanoscale. 2014;6:13451–13456. doi: 10.1039/c4nr04164j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demirkol MO, Acar O, Ucar B, Ramazanoglu SR, Saglican Y, Esen T. Prostate-specific membrane antigen-based imaging in prostate cancer: Impact on clinical decision making process. Prostate. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pros.22956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osborne JR, Akhtar NH, Vallabhajosula S, Anand A, Deh K, Tagawa ST. Prostate-specific membrane antigen-based imaging. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee SR, Pullambhatla M, Byun Y, Nimmagadda S, Green G, Fox JJ, Horti A, Mease RC, Pomper MG. 68Ga-labeled inhibitors of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) for imaging prostate cancer. J Med Chem. 2010;53:5333–5341. doi: 10.1021/jm100623e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerjee SR, Pullambhatla M, Foss CA, Nimmagadda S, Ferdani R, Anderson CJ, Mease RC, Pomper MG. (6)(4)Cu-labeled inhibitors of prostate-specific membrane antigen for PET imaging of prostate cancer. J Med Chem. 2014;57:2657–2669. doi: 10.1021/jm401921j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Zaria ME, Genady AR, Janzen N, Petlura CI, Beckford Vera DR, Valliant JF. Preparation and evaluation of carborane-derived inhibitors of prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) Dalton Trans. 2014;43:4950–4961. doi: 10.1039/c3dt53189a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norian LA, James BR, Griffith TS. Advances in Viral Vector-Based TRAIL Gene Therapy for Cancer. Cancers. 2011;3:603–620. doi: 10.3390/cancers3010603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White SJ, Voelkel-Johnson C. Illuminating TRAIL gene therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1521–1522. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.11.3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonavida B, Ng CP, Jazirehi A, Schiller G, Mizutani Y. Selectivity of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis of cancer cells and synergy with drugs: The trail to non-toxic cancer therapeutics. Int J Oncol. 1999;15:793–802. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vigneswaran N, Wu J, Nagaraj N, Adler-Storthz K, Zacharias W. Differential susceptibility of metastatic and primary oral cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlo-Stella C, Lavazza C, Locatelli A, Vigano L, Gianni AM, Gianni L. Targeting TRAIL agonistic receptors for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2313–2317. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffith TS, Stokes B, Kucaba TA, Earel JK, Jr, VanOosten RL, Brincks EL, Norian LA. TRAIL gene therapy: from preclinical development to clinical application. Curr Gene Ther. 2009;9:9–19. doi: 10.2174/156652309787354612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holoch PA, Griffith TS. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL): a new path to anti-cancer therapies. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walczak H, Bouchon A, Stahl H, Krammer PH. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand retains its apoptosis-inducing capacity on Bcl-2- or Bcl-xL-overexpressing chemotherapy-resistant tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3051–3057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walczak H, Miller RE, Ariail K, Gliniak B, Griffith TS, Kubin M, Chin W, Jones J, Woodward A, Le T, Smith C, Smolak P, Goodwin RG, Rauch CT, Schuh JC, Lynch DH. Tumoricidal activity of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:157–163. doi: 10.1038/5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaliberova LN, Della Manna DL, Krendelchtchikova V, Black ME, Buchsbaum DJ, Kaliberov SA. Molecular chemotherapy of pancreatic cancer using novel mutant bacterial cytosine deaminase gene. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2845–2854. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohila V, Jaiswal A, Ghosh SS. Rationally designed Escherichia coli cytosine deaminase mutants with improved specificity towards the prodrug 5-fluorocytosine for potential gene therapy applications. Medchemcomm. 2012;3:1316–1322. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kagawa S, He C, Gu J, Koch P, Rha SJ, Roth JA, Curley SA, Stephens LC, Fang B. Antitumor activity and bystander effects of the tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) gene. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3330–3338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren XW, Liang M, Meng X, Ye X, Ma H, Zhao Y, Guo J, Cai N, Chen HZ, Ye SL, Hu F. A tumor-specific conditionally replicative adenovirus vector expressing TRAIL for gene therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13:159–168. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher GA, Kuo T, Ramsey M, Schwartz E, Rouse RV, Cho CD, Halsey J, Sikic BI. A phase II study of gefitinib, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin in previously untreated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7074–7079. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang F, Lin J, Xu R. The molecular mechanisms of TRAIL resistance in cancer cells: help in designing new drugs. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:6714–6722. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140929100735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dimberg LY, Anderson CK, Camidge R, Behbakht K, Thorburn A, Ford HL. On the TRAIL to successful cancer therapy? Predicting and counteracting resistance against TRAIL-based therapeutics. Oncogene. 2013;32:1341–1350. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu R, Deedigan L, Albarenque SM, Mohr A, Zwacka RM. Delivery of sTRAIL variants by MSCs in combination with cytotoxic drug treatment leads to p53-independent enhanced antitumor effects. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e503. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto T, Nagano H, Sakon M, Wada H, Eguchi H, Kondo M, Damdinsuren B, Ota H, Nakamura M, Wada H, Marubashi S, Miyamoto A, Dono K, Umeshita K, Nakamori S, Yagita H, Monden M. Partial contribution of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)/TRAIL receptor pathway to antitumor effects of interferon-alpha/5-fluorouracil against Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7884–7895. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yata VK, Gopinath P, Ghosh SS. Emerging implications of nonmammalian cytosine deaminases on cancer therapeutics. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;167:2103–2116. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG. Primer3-new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Z, Penet MF, Nimmagadda S, Li C, Banerjee SR, Winnard PT, Jr, Artemov D, Glunde K, Pomper MG, Bhujwalla ZM. PSMA-targeted theranostic nanoplex for prostate cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2012;6:7752–7762. doi: 10.1021/nn301725w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banerjee SR, Foss CA, Castanares M, Mease RC, Byun Y, Fox JJ, Hilton J, Lupold SE, Kozikowski AP, Pomper MG. Synthesis and evaluation of technetium-99m- and rhenium-labeled inhibitors of the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) J Med Chem. 2008;51:4504–4517. doi: 10.1021/jm800111u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yue YA, Jin F, Deng R, Cai JG, Chen YC, Lin MCM, Kung HF, Wu C. Revisit complexation between DNA and polyethylenimine - Effect of uncomplexed chains free in the solution mixture on gene transfection. J Control Release. 2011;155:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaughan EE, Dean DA. Intracellular trafficking of plasmids during transfection is mediated by microtubules. Molecular Therapy. 2006;13:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hobel S, Aigner A. Polyethylenimine (PEI)/siRNA-Mediated Gene Knockdown In Vitro and In Vivo. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;623:283–297. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-588-0_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park K. PEI-DNA complexes with higher transfection efficiency and lower cytotoxicity. J Control Release. 2009;140:1. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li C, Penet MF, Wildes F, Takagi T, Chen Z, Winnard PT, Artemov D, Bhujwalla ZM. Nanoplex delivery of siRNA and prodrug enzyme for multimodality image-guided molecular pathway targeted cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6707–6716. doi: 10.1021/nn102187v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martello F, Piest M, Engbersen JF, Ferruti P. Effects of branched or linear architecture of bioreducible poly(amido amine)s on their in vitro gene delivery properties. J Control Release. 2012;164:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yue YA, Jin F, Deng R, Cai JG, Dai ZJ, Lin MCM, Kung HF, Mattebjerg MA, Andresen TL, Wu C. Revisit complexation between DNA and polyethylenimine - Effect of length of free polycationic chains on gene transfection. J Control Release. 2011;152:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rauch J, Kolch W, Laurent S, Mahmoudi M. Big Signals from Small Particles: Regulation of Cell Signaling Pathways by Nanoparticles. Chem Rev. 2013;113:3391–3406. doi: 10.1021/cr3002627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maeda H. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature: The key role of tumor-selective macromolecular drug targeting. Adv Enzyme Regul Vol 41. 2001;41:189–207. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(00)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wernicke AG, Edgar MA, Lavi E, Liu H, Salerno P, Bander NH, Gutin PH. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen as a Potential Novel Vascular Target for Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:1486–1489. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2010-0740-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas CE, Ehrhardt A, Kay MA. Progress and problems with the use of viral vectors for gene therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:346–358. doi: 10.1038/nrg1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.