Abstract

Statins possess potent immunomodulatory effects that may play a role in preventing acute GVHD (aGVHD) following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT). We performed a Phase II study of atorvastatin for aGVHD prophylaxis when given to allo-HCT recipients and their HLA-matched sibling donors. Atorvastatin (40mg/day) was administered to sibling donors, beginning 14 days before the anticipated start of stem cell collection. Allo-HCT recipients (n=40) received atorvastatin (40mg/day) in addition to standard aGVHD prophylaxis. The primary endpoint was cumulative incidence of grades 2-4 aGVHD at day 100. Atorvastatin was well tolerated and there were no attributable grade 3-4 toxicities in donors or their recipients. Day 100 and 180 cumulative incidences of grade 2-4 aGVHD were 30% (95% CI 17- 45%) and 40% (95% CI 25-55%), respectively. One-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD was 43% (95% CI 32- 69%). One year non-relapse mortality and relapse incidences were 5.5% (95% CI 0.9-16.5%) and 38% (95% CI 18- 47%), respectively. One-year progression-free survival and overall survival were 54% (95% CI 38-71%) and 82% (95% CI 69-94%). One-year GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS) was 27% (95% CI 16-47%). These results did not differ from our historical controls (N=96). While safe and tolerable, the addition of atorvastatin did not appear to provide any benefit to standard GVHD prophylaxis alone.

Keywords: Atorvastatin, Allogeneic hematopoeitic stem cell transplant, graft-versus-host-disease

Introduction

Acute graft-versus-host-disease (aGVHD) is the major complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT), developing in 30-50% of patients undergoing a matched-related or unrelated allo-HCT following standard aGVHD prophylaxis1-3. The pathophysiology of aGVHD is complex but involves the activation of host antigen presenting cells (APCs) by recipient conditioning which in turn activate transplanted donor T lymphocytes that expand and differentiate into effector cells that mediate cytotoxicity against recipient tissues through Fas-Fas ligand interactions, perforin-granzyme B, and cytokine production1,3-5. When severe, aGVHD carries a poor prognosis, with only 25% long term survival for grade III and 5% for grade IV2.

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), the cholesterol lowering medications, exhibit a variety of immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties that are relevant in the context of aGVHD6,7. Reduced mevalonate production by statins, not only inhibits the synthesis of cholesterol but also that of key isoprenoid intermediate molecules required for the isoprenylation of GTP-binding cell signaling proteins such as Ras, Rho and Rac7. Inhibiting Ras leads to development of T helper 2 (TH-2) cells and regulatory T (Treg) cells8 while inhibiting pro-inflammatory TH-1 driven responses9,10. Statins also indirectly decrease T-cell activation by reducing the expression of CD80 and CD86, inhibiting the proliferation of alloreactive T cells in response to simvastatin-treated CD40-activated B cells11.

In an MHC mismatched murine model, simultaneous administration of atorvastatin to both donor and recipient mice showed protective effects against aGVHD when compared to treatment of donor or recipient alone due to the reduction of TH-1 cytokines, proliferation of TH-2 cytokines, and down regulation of co-stimulatory molecules and MHC-II expression on APCs 12. Recently, a single institution prospective phase II clinical study used the same strategy as in the mouse model (atorvastatin given to donors and recipient) and showed an impressive 3.3% cumulative incidence of aGVHD at day 100 in patients undergoing sibling-matched allo-HCT13. We now present the results of a phase II prospective trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of atorvastatin for the prophylaxis of aGVHD in patients undergoing HLA-matched related donor allo-HSCT at our institution, with inclusion/exclusion criteria and treatment plan virtually identical to the above study.

Patients and Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ohio State University. Written informed consent was obtained from both donor and patient before enrollment. The study was listed in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01491958).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients ≥18 years with hematologic malignancies requiring a myeloablative (MA) or reduced-intensity (RIC) conditioning allo-HCT who had an HLA-matched (10/10 HLA-A,B,C, DQ, and DRB1 matched by high resolution) sibling donor were eligible. Donors and patients were required to have a Karnofsky performance status ≥ 70, adequate renal function (creatinine clearance of ≥ 40% of normal), bilirubin, AST, and ALT < 2× upper limit of normal, and no other serious organ dysfunction or medical conditions. Ex-vivo or in-vivo T-cell depleted allo-HCT including anti-thymocyte globulin were excluded.

GVHD prophylaxis and Conditioning regimen

Consenting donors received atorvastatin 40 mg daily orally starting at least 14 days before anticipated first day of peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) collection via leukapheresis (LP) until a target CD34+ cell dose of 4×10^6/kg recipient weight was reached. Donor stem cells were mobilized with filgrastim (10μg/kg/day) and infused fresh into patients. Recipients were given atorvastatin 40 mg daily orally starting at least 7 days before initiation of transplant conditioning. In addition patients uniformly received our standard prophylaxis GVHD regimen of methotrexate (15 mg/m2 on day +1 after stem cell infusion, and at a dose of 10 mg/m2 on Days + 3, +6, and +11 if MA, and 5mg/m2 on days +1, +3, and +6 for patients receiving RIC allo-HCT), and tacrolimus (0.02 mg/kg every 24 hours as a continuous intravenous infusion or 0.03 mg/kg orally beginning on Day −2, adjusted to target dose level of 8-12 ng/ml). Atorvastatin was continued until day +180, or until cessation of immunosuppression, significant toxicity, grade 2-4 aGVHD, or severe chronic GVHD (cGVHD). Fungal, viral and Penumocystic jiroveci prophylaxis were routinely instituted. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was only used in cases of infections with neutropenia.

End Points

Primary outcomes were incidence of grades 2-4 aGVHD at day +100 and safety of atorvastatin administration in both donor and recipient. Secondary outcomes included rates of late-onset aGVHD (d+101-180), cGVHD, disease relapse, non-relapse mortality (NRM), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). Grading of aGVHD and cGVHD were done using the consensus conference criteria14 and the National Institute of Health Consensus Development Project Criteria, respectively15,16. While not required, the diagnosis of aGVHD was histologically confirmed whenever possible. Compliance with atorvastatin among donors and patients was monitored by reviewing diaries and assessing pill bottles. Adverse events and toxicities in both donors and patients were monitored using the NCI CTCAE V 4.0 criteria.

Donor-cell Chimerism, Immune Reconstitution and cytokine analysis

Lineage-specific (myeloid (CD33+) and T-lymphoid (CD3+) donor cell chimerism analysis was performed on days +30, +100,+180 and +365 post allo-HCT. For immune reconstitution assays, detailed flow cytometric analysis of B and T lymphocytes and NK cells were performed on allograft samples (day 0) and Peripheral blood (PB) collected on days +30 and +100 (details in data supplement and Table 1S). For cytokine analysis, PB were collected from patients before start of conditioning regimen, on days 0 (allograft infusion day), +30 and +100 post allo-HCT. Plasma was extracted and levels of 27 cytokines were measured (details in data supplement).

Statistical Analysis

We utilized Simon’s minimax two-stage design to assess if the use of atorvastatin reduced the incidence of grade 2-4 aGVHD at day +100. Our hypothesis was that use of atorvastatin would reduce the proportion of patients with Grade 2-4 aGVHD at day +100 from 35% to 15% (90% power, α=0.05, details in supplemental). Time to neutrophil engraftment was calculated based on an ANC >= 0.5×10^9/L for 3 days, and platelet engraftment based on platelet count>=20×10^9/L for 7 days without transfusion. Progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were each defined from the time of transplant, and these estimates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Cumulative incidence of aGVHD was evaluated within the first 180 days post-transplant, whereas cGVHD was evaluated within the first 12 months post-transplant given that patients were followed for at least 100 days and without early progression or death. aGVHD was defined as GVHD occurring within the first 100 days of allo-HCT and late aGVHD was aGVHD occurring after day 100 post-transplant. Cumulative incidence of aGVHD, cGVHD, relapse, and non-relapse mortality (NRM) were analyzed using Gray’s test and accounting for competing risks; competing risks for aGVHD and cGVHD were relapse or death, the competing risk for relapse was death from any cause, and the competing risk for NRM was death due to disease. For all analyses, patients without an event were censored at the time last evaluated for a particular endpoint. McNemar’s test was used to evaluate agreement between paired reviewers for GVHD incidence and grading. All p-values presented are from 2-sided tests, where statistical significance was determined at α = 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.3 or the cmprsk package in R, version 2.15.0 (http://www.r-project.org).

Comparison Control Cohort

For historical context, we compared our defined endpoints between patients on this trial with patients undergoing a 10/10 HLA matched sibling PB allo-HCT where neither the patient nor the matched donor received cholesterol-lowering medications. Between August/2006 and February/2012, the time period consistent with current protocols for transplant and prophylaxis, 96 patients and donors who had provided consent for data collection were identified.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Forty patient/donor pairs were enrolled between March/2012 and January/2014. All patients received PBSC from a 10/10 HLA matched sibling donors. Patient and donor baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age of patients was 51 years (range 27-71) and of donors 50 years (range 25-68). Five patients (13%) and 14 donors (35%) were receiving some form of statin medication prior to enrollment which was discontinued and switched to atorvastatin 40 mg at study initiation. Intermediate/high risk disease constituted 23 patients (57.5%) by ASBMT criteria17 and 36 patients (90%) by disease risk index18. Twelve patients (30%) received a MA regimen. Eighteen of the transplants (46%) were sex-mismatched. Sixty-five percent of patients were in complete remission and 12.5% in partial remission at the time of transplant.

Table 1. Baseline Patient Characteristics at the Time of Transplantation.

| Characteristic | N = 40(%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Patient age at transplant: Median (range) | 51 (27-71) |

|

| |

| Patient Sex | |

| Male | 20 (50) |

| Female | 20 (50) |

|

| |

| Donor age at transplant: Median (range) | 50(25-68) |

| Donor Sex | |

| Male | 20 (50) |

| Female | 20 (50) |

|

| |

| Donor/patient sex | |

| M/F | 9 (23) |

| F/M | 9 (23) |

| Match | 22 (50) |

|

| |

| Diagnosis | |

| ALL | 6 (15) |

| AML | 13 (33) |

| CML | 3 (8) |

| MDS/CMML | 7 (18) |

| NHL/Hodgkin | 6 (15) |

| Others | 5 (13) |

|

| |

| ASBMT Risk Category17 | |

| Low | 15 (37.5) |

| Intermediate | 12 (30) |

| High | 11 (27.5) |

| other | 2 (5) |

|

| |

| Disease Risk Index18 | |

| Low | 4 (10) |

| Intermediate | 23 (57.5) |

| High | 11 (27.5) |

| Very high | 2 (5) |

|

| |

| Karnofsky performance Score Median (range) |

90 (70-100) |

| 100 | 5 (13) |

| 90 | 26 (65) |

| 80 | 5 (13) |

| 70 | 4 (10) |

|

| |

| Co-morbidity Index score Median (range) |

3 (0-8) |

| 0 | 3 (8) |

| 1-2 | 16 (40) |

| 3-4 | 17 (43) |

| 5+ | 4 (10) |

|

| |

| Conditioning Regimen and Type | |

| Myeloablative (MA) | 12 (30) |

| Fludarabine/Busulfan | 6 |

| Total Body Irradiation/Etoposide (VP16. TBI) | 4 |

| Total Body Irradiation/Etoposide | 2 |

| Reduced Intensity Conditioning (RIC) | 28 (70) |

| Fludarabine/Busulfan | 26 |

| Fludarabine/Melphalan | 2 |

|

| |

| Patient Prior Statin Use | |

| Yes | 5 (13) |

| No | 35 (88) |

|

| |

| Donor Prior Statin Use | |

| Yes | 14 (35) |

| No | 26 (65) |

|

| |

| HLA Match (high resolution) | |

| 10/10 | 40 (100) |

|

| |

| Donor Stem Cell Source | |

| Peripheral Blood | 40 (100) |

|

| |

| ABO Mismatch | |

| Yes | 14 (35) |

| No | 26 (65) |

|

| |

| EBV seropositivity match at screening (D/R) | |

| EBV−/EBV+ | 5 (13) |

| EBV−/EBV− | 1 (3) |

| EBV+/EBV− | 2 (5) |

| EBV+/EBV+ | 32 (80) |

|

| |

| CMV seropositivity match at screening (D/R) | |

| CMV−/CMV+ | 6 (15) |

| CMV−/CMV− | 18 (45) |

| CMV+/CMV− | 6 (15) |

| CMV+/CMV+ | 10 (25) |

|

| |

| Prior Auto | |

| Yes | 5 (13) |

| No | 35(88) |

|

| |

| Remission status at Transplant | |

| CR | 26 (65) |

| PR | 5 (12.5) |

| PD | 0 |

| Other* | 9 (22.5) |

|

| |

| Stem cell Mobilization | |

| Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor | 40 (100) |

|

| |

| CD34+ cell × 10^6 infused | |

| Median | 5.90 |

| Range | 2.20-15.02 |

|

| |

| CD3+ cells × 10^8 infused | |

| Median | 2.65 |

| Range | 1.14-7.29 |

Abbreviations: M male; F female; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia, AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; NHL, Non-hodgkins lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; SLL small lymphocytic leukemia; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein barr virus; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission, PD, progression of disease.

(2 chronic phase chronic phase myelogenous leukemia, 3 CMML, 1 myelofibrosis, 1 MDS, 1 each chemosensitive Hodgkins and NHL)

Compliance and Toxicity

Atorvastatin was generally well tolerated by the donors, with no more than grade 2 toxicity attributable to atorvastatin observed. The median duration of atorvastatin use in donors was 14 days (range 13-27). Seventeen (43%) donors received atorvastatin for more than 14 days. Atorvastatin was held for 2 days in one donor 16 days after starting drug due to grade 2 myalgia. The drug was restarted at 20 mg for 5 more days without any further toxicity. Atorvastatin did not adversely affect stem cell collection with a median CD34+ collection of 5.9×10^6/kg (range 2.2-15.02) and median collection day of 1(range 1-3).

Patients received atorvastatin for a median of 127 days (range 32-287). Atorvastatin was held in 5 patients, temporarily in 4. One patient developed posterior Reversible Encephalopathic Syndrome on day 24 post-transplant. Atorvastatin was held for 7 days and restarted at full dose for a total use of 196 days. Two patients had grade 2 elevated liver enzymes for which atorvastatin was held briefly and restarted at full dose for a total use of 126 and 285 days, respectively. One patient relapsed just prior to conditioning following 7 days of atorvastatin. After achieving a second complete remission, atorvastatin was restarted and given for a total of 196 days. The fifth patient had grade 4 asymptomatic elevated liver enzymes with normal bilirubin after being on atorvastatin for 146 days. A liver biopsy showed mixed portal and lobular inflammation with a range of differential diagnosis including medications and infections. The patient did not receive steroids and had no evidence of aGVHD. None of these was attributable to atorvastatin by the treating physician. There were no other toxicities attributable to atorvastatin.

Engraftment and Chimerism

The median time to neutrophil and platelet engraftment were 18 days (range 13-26) and 14 days (range 9-29) respectively. Median myeloid-cell donor chimerism was 100% at all time points analyzed. Median T-cell chimerism was 100% from day+180 onward (Table 2S). Primary or secondary graft failure did not occur.

Graft versus Host disease

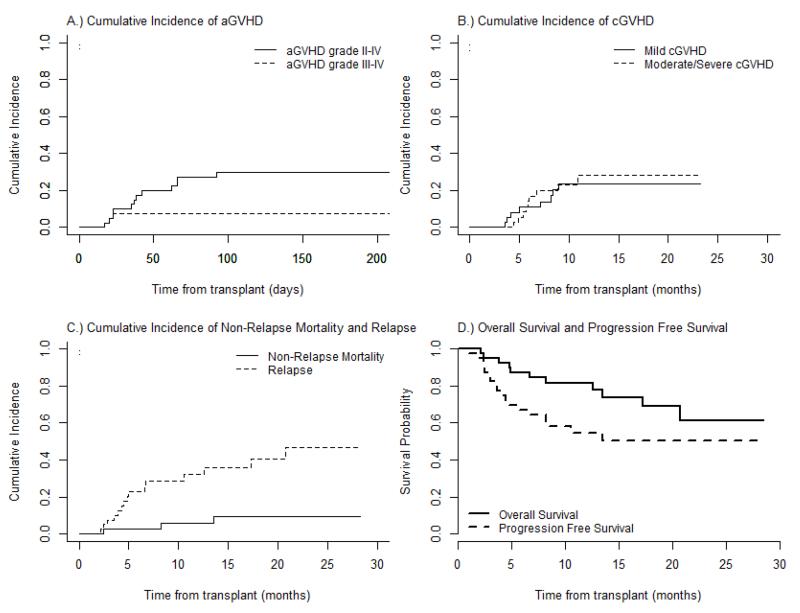

All patients were evaluable for aGVHD. Two patients developed grade 1 aGVHD of the skin and were treated with topical steroids. The cumulative incidences of grade 2-4 aGVHD at Days +100 and +180 were 30% (95% CI 17- 45%) and 40% (95% CI 25-55%), respectively. Corresponding incidence of grades 3-4 aGVHD was 8% (95% CI 1.9-18.4%) at both 100 and 180 days (Figure 1A). The median day of onset of aGVHD was 42 (range 17-172). Six of the 12 patients with aGVHD had at least 2 organs involvement. While not required, the diagnosis of aGVHD was histologically confirmed whenever possible. All patients except 4 had histologic confirmation or evidence of aGVHD. The 4 patients who did not have biopsies were UGI (2 patients) and skin (2 patients). All patients with suspected lower GI GVHD had histologic confirmation with assessment for CMV and adenovirus infection. CMV and adenovirus were negative in all biopsy samples.

Figure 1.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) prophylaxis with Atorvastatin: (A) Cumulative incidences of aGVHD grade II-IV and III-IV. (B) Cumulative incidences of chronic GVHD (cGVHD), mild/moderate and severe. (C) Cumulative incidences of Non-relapse mortality and relapse. (D) progression free and overall survival curves.

No patient was tapered off tacrolimus before day 100 unless if relapse or toxicity. Only one patient was taken off tacrolimus before day 100 due to renal toxicity and started on mycophenolate. Four patients developed aGVHD after day 100 - one patient who developed skin aGVHD at day 141 did not take tacrolimus for 3-4 days before onset of GVHD; A second patient had persistent cytogenetic abnormality post HSCT evaluation (day 100) for MDS and tacrolimus was tapered off. The patient developed aGVHD two months later (day 165) with initial skin, then lower GI; The third patient who had diffuse large B cell lymphoma and had persistent disease at transplant, was taken off immune suppression at day 105 and developed skin GVHD day 115. The fourth patient was taken off tacrolimus on day 77 due to worsening renal insufficiency. Mycophenolate was started on same day and aGVHD was diagnosed on day 108 with nausea/vomiting, and weight loss.

The cumulative incidence of cGVHD at one year was 43% (95% CI 32- 69%). The distribution of organ involvement is listed in Table 2. Cumulative incidences of mild and moderate/severe cGVHD were 23.6% (95% CI, 10.7 – 39.5%) and 28.2% (95% CI, 12.8 – 45.9%); limited and extensive: 19% (95% CI 8.71-36.1%) and 25% (95% CI 15-48.9%) respectively (Figure 1B) (Table 3). To mitigate any biases in GVHD grading due to lack of blinding, four authors performed a retrospective review of patient charts and assigned GVHD grades without knowledge of the original assessment. There was good concordance between the original GVHD grading and that of the independent reviewers for aGVHD (p=0.5637) and cGVHD (p=0.3173) with some minor discordance for late aGVHD (p=0.0833) (Table 4).

Table 2. Organ Involvement in chronic GVHD for Statin Patients.

| Organ involvement | Number of Patients N=17 (43%) |

|---|---|

| Oral | 13 (76%) |

| Skin | 6 (35%) |

| Liver | 3 (18%) |

| Eyes | 3 (18%) |

| Lungs | 3 (18%) |

| Genital | 2 (12%) |

| 2 or more organ involvement | 9 (53%) |

Table 3. Pattern of Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) of Statin vs. Non-Statin group.

| Cumulative Incidence: aGVHD | Statin group =4 0 n (% of total) |

Non-Statin group =96 n (% of total) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Grade II – IV, Day 100 | |||

| Number of Events | 12 (30) | 27 (28) | 0.83 |

| Cumulative Incidence at Day 100 (95% CI) | 0.30 (0.17-0.45) | 0.28 (0.20-0.37) | |

|

| |||

| Grade III – IV, Day 100 | |||

| Number of Events | 3 (8) | 9 (9) | 0.78 |

| Cumulative Incidence at Day 100 (95% CI) | 0.075 (0.019-0.184) | 0.094 (0.046-0.163) | |

|

| |||

| Grade II – IV, Day 180 | |||

| Number of Events | 16 (40) | 30 (31) | 0.38 |

| Cumulative Incidence at Day 180 (95% CI) | 0.40 (0.25-0.55) | 0.31 (0.22-0.41) | |

|

| |||

| Grade III – IV, Day 180 | |||

| Number of Events | 3 (8) | 6 (6) | 0.75 |

| Cumulative Incidence at Day 180 (95% CI) | 0.075 (0.019-0.184) | 0.0625 (0.025-0.123) | |

|

| |||

| Cumulative Incidence: cGVHD | |||

|

| |||

| Any cGVHD | |||

| Number of events | 17 (43) | 46 (48) | |

| Cumulative incidence at 12 months (95% CI) | 0.52 (0.32-0.69) | 0.50 (0.39-0.60) | 0.91 |

|

| |||

| Extensive cGVHD | |||

| Number of Events | 10 (25) | 44 (46) | |

| Cumulative incidence at 12 months (95% CI) | 0.31 (0.15-0.48) | 0.48 (0.36-0.58) | 0.0495 |

|

| |||

| Severe cGVHD | |||

| Number of Events | 5 (13) | 11 (11) | |

| Cumulative incidence at 12 months (95% CI) | 0.15 (0.05-0.29) | 0.13 (0.07-0.22) | 0.91 |

|

| |||

| Limited vs extensive cGVHD | |||

| Number evaluable | 37 | 83 | |

| Number of Events | |||

| Limited | 7 (19) | 2 (2) | |

| Extensive | 10 (27) | 44 (53) | |

| Estimated cumulative incidence of limited cGVHD at 12 months (95% CI) |

0.207 (0.087-0.361) | 0.024 (0.005-0.078) | 0.0008 |

| Estimated cumulative incidence of extensive cGVHD at 12 months (95% CI) |

0.312 (0.15-0.489) | 0.476 (0.363-0.58) | 0.065 |

|

| |||

| Mild vs. mod/severe cGVHD | |||

| Number evaluable | 37 | 83 | |

| Number of Events | |||

| Mild | 8 (22) | 6 (7) | |

| Moderate/Severe | 9 (24) | 20 (24) | |

| Estimated cumulative incidence of mild cGVHD at 12 months (95% CI) |

0.236 (0.107-0.395) | 0.074 (0.03-0.146) | 0.008 |

| Estimated cumulative incidence of mod/severe cGVHD at 12 months (95% CI) |

0.282 (0.128-0.459) | 0.221 (0.137-0.317) | 0.75 |

Table 4. Concordance Between Original GVHD Grading and Independent Review of Statin Group.

| Original | Independent Review | Totals | McNemar’s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aGVHD | Grade 0 or 1 | Grade2+ | 0.5637 | |

| Grade 0 or 1 | 26 | 2 | 28 | |

| Grade 2+ | 1 | 11 | 12 | |

| Totals | 27 | 13 | 40 | |

| Late aGVHD | Grade 0 or 1 | Grade2+ | 0.0833 | |

| Grade 0 or 1 | 32 | 0 | 32 | |

| Grade 2+ | 3 | 5 | 8 | |

| Totals | 35 | 5 | 40 | |

| cGVHD | Extensive | Limited | 0.3173 | |

| Extensive | 11 | 0 | 11 | |

| Limited | 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| Totals | 12 | 5 | 17 | |

Relapse and Survival

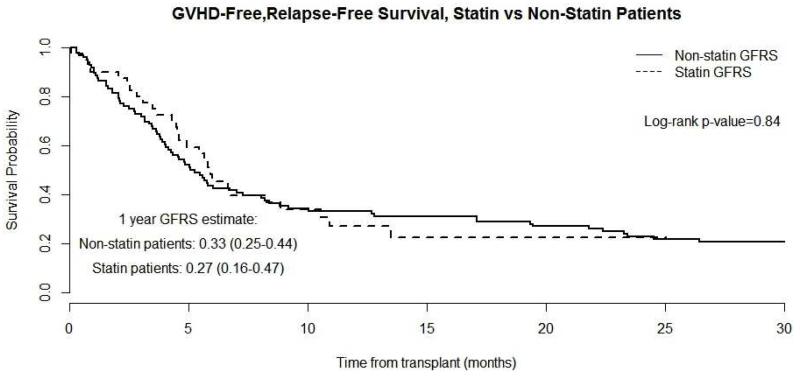

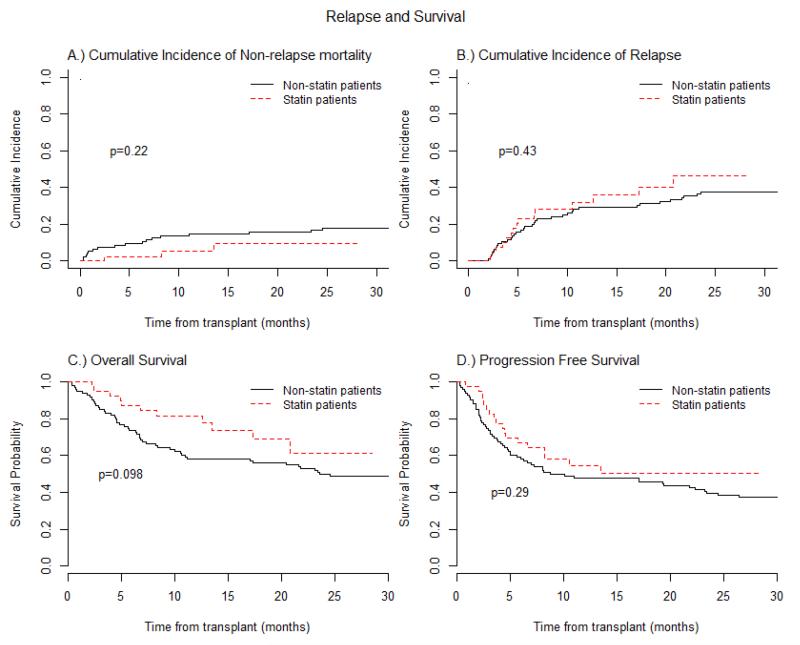

The median follow up of surviving patients was 13 mos (range 2.2 – 28.5), where 11 patients (27.5%) have died, eight from relapsed disease, two from complications of GVHD, and one from respiratory failure (Table 3S). One-year cumulative incidence estimates of NRM and relapse were 5.5% (95% CI 0.9-16.5%) and 32% (95% CI, 18 -47%), respectively (Figure 1C). One-year PFS and OS were 54% (95% CI 38-71%) and 82% (95% CI 69-94%), respectively (Figure 1D). The one-year GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS) was 27% (95% CI 16-47%) (Figure 4). GFRS events were defined as grade 3-4 aGVHD, cGVHD requiring systemic immune suppressive treatment, disease relapse, or death from any cause during the first 12 months after allo-HCT19.

Figure 4.

Composite Graft-versus-host disease-Free, Relapse-Free Survival (GRFS) of Atorvastatin compared to Non-Statin group (control): Dash-line represents Statin group and solid line Non-statin group.

Comparison with Control Cohort

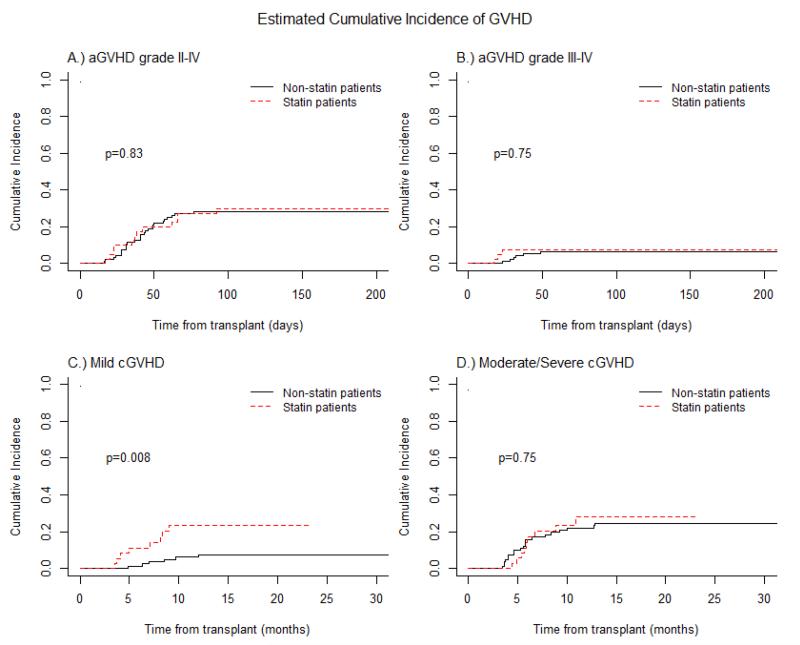

The intensity of conditioning regimen, patient age, and donor sex were all evaluated and were found to be comparable between the study patients and the historical control cohort (non-statin group, Table 4S). aGVHD prophylaxis in controls consisted of methotrexate/tacrolimus only and neither patients nor their corresponding donors had been exposed to cholesterol lowering medications. Significant differences between atorvastatin and non-statin patients included a higher number of MDS/CMML patients (p=0.0374) and increased use of fludarabine/busulfan conditioning regimen in the statin group (p=0.0288) (Table 4S). Donor-cell chimerism was not significantly different between the groups (Table 2S) as well as CMV and EBV reactivation, BK viremia, fungal or bacterial infections (Table 5S). Moreover, we did not find any significant differences in the incidence rates of aGVHD (p=0.8303), cGVHD (p=0.915), relapse (p=0.4311), PFS (p=0.2862), OS (p=0.098) and GFRS (p=0.84) (Figures 2-4, Table 3, Table 3S).

Figure 2.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) prophylaxis with Atorvastatin compared to Non-Statin group (control): (A) Cumulative incidences of aGVHD grade II-IV .: (B) Cumulative incidences of aGVHD grade III-IV. (C) Cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD(cGVHD), mild/moderate. (D) Cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD(cGVHD) severe. Dash-line represents Statin group and solid line Non-statin group.

We analyzed the PBSC allograft (day 0) and PB samples at days +30 and +100 of statin patients compared to 25 non-statin patients to determine the effect of atorvastatin on allograft composition and immune reconstitution. The statin group allografts contained less NK and T-reg cells than the non-statin group. This reduction in NK-cell and T-reg cells appeared to affect the reconstitution of these subsets post-transplant as reflected by their continued decrease on days 30 and 100 post-transplant compared to the non-statin group (Table 5). Cytokine analysis performed on 20 statin and 16 non-statin patients matched to age, conditioning regimen, and evidence/no evidence of GVHD, found no significant differences in the levels of most cytokines, with the exception of RANTES (CCR1/CCR5) (Figure 1S).

Table 5. Immune Reconstitution Analysis Statin vs. Non-Statin Group.

| Marker Allograft(day 0) |

Percent Median (range) Statin N=40 |

Percent Median (range) Non-statin N=25 |

Wilcoxon test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD3−/CD5616+ (NK cell) | 8.00 (2.30-26.90) | 10.75 (4.7-20.0) | 0.0374 |

| CD3+/CD134+ ( mid activation T cell) | 1.40 (0.30-8.70) | 3.1 (0.5-11.2) | 0.0367 |

| CD3+ / CD86+ (activation molecule) | 0.20 (0.05-0.56) | 0.3 (0.1-0.5) | 0.0148 |

| CD4+/CD25+/CD127-(T regs) | 0.10 (0-1.60) | 1.0 (0-4.7) | <0.0001 |

| CD4+/CD25+/CD127-ALT (T regs) | 0.25 (0-1.20) | 0.6 (0.2-1.5) | 0.0072 |

| CD3−/CD5616+/CD158b+ (NK cell) | 1.70 (0.30-5.40) | 2.7 (0.4-9.7) | 0.0225 |

| CD3−/CD5616+/CD159a+(NK cell activation) | 1.60 (0.20-5.30) | 3.4 (0.8-8.3) | 0.0003 |

| Day 30 | |||

| CD19+ | 1.20 (0-21.10) | 0.7 (0-5.8) | 0.0194 |

| CD3+/CD134+ | 0.60 (0-9.60) | 3.4 (0.2-7.3) | 0.0010 |

| CD4+/CD25+/CD127− | 0.20 (0-2.30) | 0.9 (0-3.6) | 0.0010 |

| CD3−/CD5616+/CD69+ (early activated NK-cell ) | 0.30 (0-2.10) | 0.8 (0-18.9) | 0.0010 |

| CD3−/CD5616+/CD159a+ | 13.80 (0.50-28.10) | 20.9 (1.3-48.3) | 0.0220 |

| CD3−/CD5616+/CD314+(NK cell activation) | 5.90 (0.60-28.60) | 15.1 (2.1-39.3) | 0.0021 |

| CD3−/CD5616+/CD63+/CD314+(NK cell activation) | 0.30 (0-3.40) | 2.7 (0.3-17.6) | <0.0001 |

| CD16+/CD56+/CD3−/CD117−(NK cell activation) | 9.90 (0.70-38.20) | 21.6 (3.9-47.8) | 0.0009 |

| Day 100 | |||

| CD3+ / CD86+ | 0.2 (0-1.3) | 0.5 (0.1-1.3) | 0.0158 |

| CD4+/CD25+/CD127− | 0.1 (0-0.9) | 0.8 (0.1-1.8) | 0.0002 |

| CD3−/CD5616+/CD63+/CD314+ | 0.3 (0-6.3) | 1.9 (0.2-14.8) | 0.0003 |

| CD16+/CD56+/CD3−/CD117− | 8.6 (0-28.8) | 11.5 (6.6-51.3) | 0.0660 |

Discussion

While atorvastatin was well tolerated by donors and patients, we did not observe any reduction in the incidence of grades 2-4 aGVHD compared with similar historical controls treated at our institution, with incidence of aGVHD at day +100 of 30% compared with 28% in controls. Moreover, we did not observe any differences in the incidence of cGVHD, relapse, PFS, OS and GRFS between these groups. Our GRFS, a new composite endpoint, was similar to that reported by the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network and others19. While there was not a statistically significant difference, there was a trend towards decreased NRM (1 year cumulative 5.5% vs 14.7%, p=0.2217) and improved OS (1 year cumulative 82% vs 58%) for the atorvastatin group compared to control. The reasons for the differences are not very apparent except that significant differences between atorvastatin and non-statin patients included a higher number of MDS/CMML patients (p=0.0374), an increased use of fludarabine/busulfan conditioning regimen and a decreased use of cyclophosphamide based conditioning regimen in the statin group (p=0.0288). The MDS/CMML patients mostly fell under the CIBMTR intermediate risk category. Whether atorvastatin itself has any effect on NRM and OS is very difficult to address without a randomized control study using same conditioning regimen for specific disease groups.

Our results contrast with those reported by the West Virginia University (WVU) group, who observed an encouragingly low rate of grades 2-4 aGVHD of only 3.3% 13. The reasons for these differences are not immediately apparent. Several factors which could have contributed may only be tested by a randomized multicenter control trial. Both studies used identical treatment plan, inclusion/exclusion criteria, donor/recipient match, same dose of atorvastatin and standard GVHD prophylactic drugs, doses and schedule. There were no differences in the median age of patients (51yrs our study vs 54), age of donor (50 yrs. vs. 52.5), female donor to male recipient (23% vs 30%), allograft source, and duration of donor atorvastatin use. While 30% of our patients and 43.2% of the WVU patients received a MA conditioning regimen, half of the MA patients in our study received total body irradiation (TBI) compared to none in the WVU study, and in some studies TBI is a risk factor for aGVHD20,21. A potentially important difference in the two studies was the duration of patient atorvastatin use (median of 127 days in our study compared to 192 days). However, considering the primary objective in both studies was the incidence of aGVHD at day +100, duration of exposure alone should not explain these differences. Caveats apply to the interpretation of the results of both studies, given the single center nature and degree of subjectivity inherent in grading grade 2 aGVHD in an open label study. We attempted to mitigate this bias by having the final grading of aGVHD made by four independent reviewers, but bias may still be a factor. The one year cumulative incidence of moderate/severe cGVHD did not seem to be different between the two studies (43.5% (95% CI 20.7-64.4% vs 28.2% (95% CI 12.8-45.9% our study) with a total cGVHD occurrence of 13 and 17 patients (43% each) respectively

The rationale for using atorvastatin 40 mg rather than a higher dose was that in healthy volunteers the plasma pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin (AUC and Cmax) becomes nonlinear and similar at doses of 40mg or above22. In addition, any potential effect of increase liver enzymes with the concurrent use of tacrolimus and methotrexate was thought to be lower with 40mg than 80mg.

An area of discussion is in the assessment of grade 2 aGVHD and in particular the scoring of isolated UGI symptoms. Should grade 2 GVHD be treated differently than 3 and 4? Does isolated UGI GVHD exist? Nine (75%) of our 12 patients with day +100 aGVHD were grade 2, and 5 patients had isolated UGI symptoms for which high dose steroids (at least 1 mg/kg/day prednisone or equivalent) were instituted for aGVHD. Three of the 5 UGI patients had endoscopy which showed rare apoptotic cells that could represent aGVHD. Endoscopy could not be obtained on the other 2 patients due to being admitted on the week/end and resolution of symptoms before endoscopy could be done. A retrospective analysis of 1723 patients by MacMillan et al showed an isolated UGI aGVHD of 6.7%23. Several differences compared to our study are 1: MacMillan is a retrospective study and aGVHD patients were selected if they had received prednisone 2 mg/kg/day or equivalent IV methylprednisolone compared to ours and conventional use of prednisone 1 mg/kg/day or greater; 2: Almost 25% of patients in the Macmillan study are children who have completely different symptom threshold. A prospective study by Wakui et al showed that 7 of 19 patients (37%) with confirmed UGI aGVHD had no other organ involvement and this was much higher than the 14% noted in their retrospective analysis24 thus stressing the need for a larger multicenter prospective study. The development of biomarkers that may help us understand and guide us in the clinical diagnosis and management of aGVHD are being studied in our institution as well as many others and should be of considerable benefit25-27. Standardized monitoring of symptoms, with early review and adjudication of GVHD has led to improved accuracy of aGVHD staging among some centers28.

In one large retrospective study, statin use was only effective when combined with cyclosporine as GVHD prophylaxis.29 In this analysis, patients who received cyclosporine as GVHD prophylaxis and whose donors were on a statin (n=54) had a reduced incidence of grade 3-4 aGVHD compared to non-statin patients/donors (n=417, p=0.003), however, this effect was not seen in the tacrolimus group(p=0.44)29. The limitation of this study was the small number of statin donors whose recipient received tacrolimus (n=21). Our initial retrospective analysis found a positive correlation with statin use and aGVHD reduction in tacrolimus recipients, prompting us to pursue this study using tacrolimus-based aGVHD prophylaxis30. Our current findings correlate with those of Rotta et al29.

The statin treated allografts contained less NK and T-regs compared to the non-statin group. However, this did not translate into an overall higher rate or severity of aGVHD and cGVHD as has been described by others31,32. The statin group did have a higher incidence of mild/moderate cGVHD (p=0.0173), but this did not translate to increase infections or mortality. Further analysis of the significance of these differences is ongoing.

We found no effect of atorvastatin on 26 cytokines, specifically IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4 and IL-10 when compared to samples not exposed to statin. IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 are pro-inflammatory cytokines, elevation of which are associated with GVHD33,34 while IL-4 and IL-10 are Th-2 driven anti-inflammatory cytokines proT-regs, associated with reduced GVHD35-37. We found a marked elevation of RANTES in the statin patients compared to non-statin patients (p<0.0001). RANTES elevation and polymorphism, through binding with chemokine CCR1 has been shown to be associated with increased GVHD38-40. The elevation in the presence of statin without an increased incidence of GVHD suggests that GVHD is a constellation of many mechanism and processes, and that the abnormality of one process may be off-set by the enhancement of another process.

In conclusion, in our phase II study and in comparison with our matched control patients, we did not observe any added benefit with atorvastatin as prophylaxis against aGVHD in matched-related allo-HCT. Given the inherent limitations of single institution aGVHD prophylaxis studies, it seems prudent that trials evaluating novel strategies to prevent aGVHD be adequately controlled, blinded if possible, and involve multiple sites at an early phase of development.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Atorvastatin did not reduce incidence of grades 2-4 aGVHD in matched-related allo-HSCT

Atorvastatin was well tolerated by both sibling donors and patients

Atorvastatin affects Natural Killer and T-regulatory cells compared to control

Atorvastatin did not affect cytokine expression compared to control

Figure 3.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) prophylaxis with Atorvastatin compared to Non-Statin group (control): (A) Cumulative incidences of Non-relapse Mortality. (B) Cumulative incidences of Relapse. (C) Progression-free Survival curve. (D) Overall Survival curves. Dash-line represents Statin group and solid line Non-statin group.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support includes the National Cancer Institute K12, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute R21.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: YE is the Principal Investigator of the study, analyze data and wrote the manuscript. SD is senior author, Co-investigator, evaluated data and edited manuscript.SG and AB did the statistical analysis and edited the manuscript. LA, SV, SJ were the independent reviewers of aGVHD endpoints, WB, RK,CH,DB,SM enrolled patients in the study, PE is BMT data coordinator, KC is research coordinator, RK and GL performed immunome analysis, LO, BD,HB isolated and stored patients whole blood serum, plasma and mononuclear cells for cytokine and other correlative assessments, JZ, XC, and JH performed the cytokine analysis, PR, XY, JH and RG provided controlled samples for cytokine analysis, SS performed apheresis stem cell collection on sibling donors, KC,SG,AB,RK, PE, SD,GL and YE were on Statin committee that helped structured how data and manuscript should be presented. All authors reviewed and edited manuscript

References

- 1.Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E. Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet. 2009;373:1550–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60237-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deeg HJ. How I treat refractory acute GVHD. Blood. 2007;109:4119–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-041889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Socie G, Blazar BR. Acute graft-versus-host disease: from the bench to the bedside. Blood. 2009;114:4327–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-204669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graubert TA, Russell JH, Ley TJ. The role of granzyme B in murine models of acute graft-versus-host disease and graft rejection. Blood. 1996;87:1232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piguet PF, Grau GE, Allet B, Vassalli P. Tumor necrosis factor/cachectin is an effector of skin and gut lesions of the acute phase of graft-vs.-host disease. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1280–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broady R, Levings MK. Graft-versus-host disease: suppression by statins. Nat Med. 2008;14:1155–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1108-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao JK, Laufs U. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:89–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mausner-Fainberg K, Luboshits G, Mor A, et al. The effect of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T cells. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:829–39. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenwood J, Steinman L, Zamvil SS. Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation. Nature reviews Immunology. 2006;6:358–70. doi: 10.1038/nri1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn SE, Youssef S, Goldstein MJ, et al. Isoprenoids determine Th1/Th2 fate in pathogenic T cells, providing a mechanism of modulation of autoimmunity by atorvastatin. J Exp Med. 2006;203:401–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Liebig T, von Bergwelt-Baildon M. Statins inhibit human APC function: implications for the treatment of GVHD. Blood. 2008;112:1544–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeiser R, Youssef S, Baker J, Kambham N, Steinman L, Negrin RS. Preemptive HMG-CoA reductase inhibition provides graft-versus-host disease protection by Th-2 polarization while sparing graft-versus-leukemia activity. Blood. 2007;110:4588–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamadani M, Gibson LF, Remick SC, et al. Sibling Donor and Recipient Immune Modulation With Atorvastatin for the Prophylaxis of Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease. J Clin Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.8747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;1995;15:825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:945–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavletic SZ, Lee SJ, Socie G, Vogelsang G. Chronic graft-versus-host disease: implications of the National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:645–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation Disease Risk Classification. 2014 http://cymcdncom/sites/wwwasbmtorg/resource/resmgr/Docs/ASBMT_RFI_2014_Translation_tpdf.

- 18.Armand P, Kim HT, Logan BR, et al. Validation and refinement of the Disease Risk Index for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2014;123:3664–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-552984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holtan SG, DeFor TE, Lazaryan A, et al. Composite end point of graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2015;125:1333–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-609032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xun CQ, Thompson JS, Jennings CD, Brown SA, Widmer MB. Effect of total body irradiation, busulfan-cyclophosphamide, or cyclophosphamide conditioning on inflammatory cytokine release and development of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease in H-2-incompatible transplanted SCID mice. Blood. 1994;83:2360–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill GR, Crawford JM, Cooke KR, Brinson YS, Pan L, Ferrara JL. Total body irradiation and acute graft-versus-host disease: the role of gastrointestinal damage and inflammatory cytokines. Blood. 1997;90:3204–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cilla DD, Jr., Whitfield LR, Gibson DM, Sedman AJ, Posvar EL. Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of atorvastatin, an inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase, in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60:687–95. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacMillan ML, Robin M, Harris AC, et al. A refined risk score for acute graft-versus-host disease that predicts response to initial therapy, survival, and transplant-related mortality. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:761–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakui M, Okamoto S, Ishida A, et al. Prospective evaluation for upper gastrointestinal tract acute graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:573–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ranganathan P, Heaphy CE, Costinean S, et al. Regulation of acute graft-versus-host disease by microRNA-155. Blood. 2012;119:4786–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paczesny S, Krijanovski OI, Braun TM, et al. A biomarker panel for acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:273–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-167098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paczesny S, Braun TM, Levine JE, et al. Elafin is a biomarker of graft-versus-host disease of the skin. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:13ra2. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.levine JEHW, Harris AC, Litzow MR, Efebera YA, Devine SM, et al. Improved accuracy of Graft-versus-host disease staging among multiple centers. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotta M, Storer BE, Storb RF, et al. Donor statin treatment protects against severe acute graft-versus-host disease after related allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240358. blood-2009-08-240358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamadani M, Awan FT, Devine SM. The impact of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition on the incidence and severity of graft-versus-host disease in patients with acute leukemia undergoing allogeneic transplantation. Blood. 2008;111:3901–2. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaidos A, Patterson S, Szydlo R, et al. Graft invariant natural killer T-cell dose predicts risk of acute graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;119:5030–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-389304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu SY, Huang XJ, Liu KY, Liu DH, Xu LP. High frequency of CD4+ CD25− CD69+ T cells is correlated with a low risk of acute graft-versus-host disease in allotransplants. Clinical transplantation. 2012;26:E158–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2012.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dustin ML. Role of adhesion molecules in activation signaling in T lymphocytes. J Clin Immunol. 2001;21:258–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1010927208180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shlomchik WD, Couzens MS, Tang CB, et al. Prevention of graft versus host disease by inactivation of host antigen-presenting cells. Science. 1999;285:412–5. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3921–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pillai AB, George TI, Dutt S, Strober S. Host natural killer T cells induce an interleukin-4-dependent expansion of donor CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells that protects against graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:4458–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levings MK, Sangregorio R, Galbiati F, Squadrone S, de Waal Malefyt R, Roncarolo MG. IFN-alpha and IL-10 induce the differentiation of human type 1 T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5530–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim DH, Jung HD, Lee NY, Sohn SK. Single nucleotide polymorphism of CC chemokine ligand 5 promoter gene in recipients may predict the risk of chronic graft-versus-host disease and its severity after allogeneic transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:917–25. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000284583.15810.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin DY, Kim I, Kim JH, et al. RANTES polymorphisms and the risk of graft-versus-host disease in human leukocyte antigen-matched sibling allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Acta Haematol. 2013;129:137–45. doi: 10.1159/000343273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi SW, Hildebrandt GC, Olkiewicz KM, et al. CCR1/CCL5 (RANTES) receptor-ligand interactions modulate allogeneic T-cell responses and graft-versus-host disease following stem-cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;110:3447–55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-087403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.