Abstract

In clinical practice, respiratory function tests are difficult to perform in Morquio syndrome patients due to their characteristic skeletal dysplasia, small body size and lack of cooperation of young patients, where in some cases, conventional spirometry for pulmonary function is too challenging. To establish feasible clinical pulmonary endpoints and determine whether age impacts lung function in Morquio patients non-invasive pulmonary tests and conventional spirometry were evaluated.

The non-invasive pulmonary tests: impulse oscillometry system, pneumotachography, and respiratory inductance plethysmography in conjunction with conventional spirometry were evaluated in twenty-two Morquio patients (18 Morquio A and 4 Morquio B) (7 males), ranging from 3 and 40 years of age.

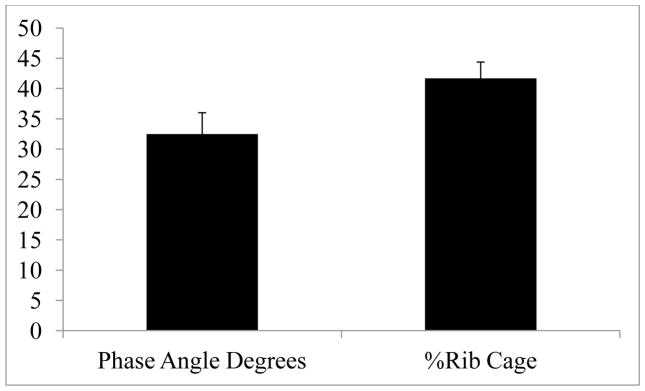

Twenty-two patients were compliant with non-invasive tests (100%) with exception of IOS (81.8%–18 patients). Seventeen patients (77.3%) were compliant with spirometry testing. All subjects had normal vital signs at rest including > 95% oxygen saturation, end tidal CO2 (38–44 mmHg), and age-appropriate heart rate (mean=98.3, standard deviation=19) (two patients were deviated). All patients preserved normal values in impulse oscillometry system, pneumotachography, and respiratory inductance plethysmography, although predicted forced expiratory volume total (72.8 ± 6.9 SE%) decreased with age and was below normal; phase angle (35.5 ± 16.5 Degrees), %Rib Cage (41.6 ± 12.7%), resonant frequency, and forced expiratory volume in one second/forced expiratory volume total (110.0 ± 3.2 SE%) were normal and not significantly impacted by age.

The proposed non-invasive pulmonary function tests are able to cover a greater number of patients (young patients and/or wheel-chair bound), thus providing a new diagnostic approach for the assessment of lung function in Morquio syndrome which in many cases may be difficult to evaluate. Morquio patients studied herein demonstrated no clinical or functional signs of restrictive and/or obstructive lung disease.

Keywords: Non-invasive pulmonary function test, Morquio syndrome, impulse oscillometry system, pneumotachography, respiratory inductance plethysmography

Introduction

Morquio syndrome is autosomal recessive disorders caused by deficiency of N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase (GALNS) (Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA, MPS IVA) and β-Galactosidase (GLB1) (Mucopolysaccharidosis IVB, MPS IVB). Theses enzymes are required for the catabolism of the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs): chrondroitin-6-sulfate (C6S) and keratan sulfate (KS) [1,2,3]. The incidence varies among different populations from 1:76,000 to 1:640,000 live births [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Morquio syndrome includes skeletal dysplasia with short stature, kyphoscoliosis, platyspondyly, odontoid hypoplasia, genu valgum, pectus carinatum, and dental abnormalities. Other findings are ligamentous laxity, corneal clouding, cardiac, and pulmonary complications without neurological involvement [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Autopsied trachea showed tracheomalacia but little evidence of narrow airway due to storage materials [9]. Difficulty of intubation and extubation was observed during the surgical procedure, which could be associated with tracheomalacia. Tracheomalacia can cause twisting, tortuous trachea, leading a high risk of anesthesia.

It has been reported that respiratory issues in patients with Morquio syndrome is associated with two conditions: 1) restrictive lung disease (inability to inspire) due to short stature and thoracic cage deformity; [18,19,15,17,20,21] 2) obstructive lung disease (inability of expire) due to tracheobronchial abnormalities, large tongue, adenoidal, tonsillar, and vocal cord hypertrophy. These respiratory issues lead to a high mortality rate or high risk during anesthesia [18, 17, 21]. The functional signs of restrictive and obstructive lung disease are that the patients cannot breath synchronously and cannot effectively maintain normal gas exchange even at rest.

However, we do not know whether the flows are actually less or greater than normal individuals when normalized for smaller volumes and stature.

Spirometry clearly evaluates several assessments of static and dynamic volume measurements; however, this approach is considered an effort dependent test requiring cooperation between subject and examiner [22]. Young patients and wheel-chair bound, and/or post-operative with severe muscle weakness cannot perform such physical assessments.

In the last two decades, pulmonary function tests (PFTs) have been revised to analyze tidal breathing in patients who are minimally cooperative due to age or clinical condition. These include impulse oscillometry (IOS), pneumotachography (PNT), and respiratory inductance plethysmography (RIP), which have been used extensively in the minimally cooperative neonate and pediatric populations [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. In addition, the IOS provides more information about the total respiratory system resistance [29].

A number of studies have shown the significance of using measurements of airway resistance and reactance at different oscillation frequencies such as IOS in various clinical settings, for detecting chest wall abnormalities, lung compliance disorders, airway obstruction, assessment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma [29,30,31,32]. Furthermore, the use of non-invasive PFT would accommodate a broader spectrum of patients (young and or/wheel-chair bound).

In contrast, to our knowledge, no systemic study has been performed to evaluate age-dependent oscillometry measurements for patients with Morquio syndrome or other skeletal dysplasias in comparison with conventional spirometry studies.

In the present study, we sought to elucidate age-dependent changes in pulmonary function utilizing non-invasive PFTs correlated with conventional spirometry (when possible) in patients with Morquio syndrome. In addition, we hypothesized that the age-dependent alterations in lung function can be correlated with the “small lungs” (compared to age-matched controls from a database group with normal stature) as measured with Spirometry.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This was an open, non-controlled, single center, assessment study of patients diagnosed as Morquio A and B who were pulmonary asymptomatic at the time of the study. The study assessed the key thoracopulmonary features. Patients with Morquio syndrome had one visit for clinical evaluation of lung function. All tests were clinically indicated and conducted on an out-patient basis at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children. This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki and it was approved by the institutional review board from the institution (750932). Informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their guardians.

Twenty-two subjects with Morquio (18 Morquio A and 4 Morquio B), from 3 to 40 years of age were tested (mean= 16.5 yrs). Part of the physical examination included measuring height, weight, and systemic skeletal examinations. We used Morquio A growth charts [14] as reference for height, weight, and BMI. Measurement of standing height in patients was difficult due to skeletal deformities, which limited patients’ ability to stand erect. To obtain consistent data, we performed several established measurements at least twice per patient. The patient lied on a flat surface with knees flattened to fully extend the legs. Standing height was also measured. For pulmonary function, arm length conversion to height was performed to determine predicted values for pulmonary standards, often used in our outpatient PFT laboratory for patients with skeletal deformities [33]. Finally, of the 22 patients, 17 (77.3%) were able to perform spirometry, leading to a limited profile of spirometry (3 young patients, 1 patient unable to perform and 1 non-cooperative patient). Data in the control subjects were derived from previous studies (National health and nutrition examination survey -NHANES III) [34].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The subjects were diagnosed as Morquio A and B by enzyme analysis. There were no exclusion criteria related to sex, age, ethnic background, scheduled operation, or physical ability.

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs)

1.1 Spirometry

All spirometry (Medgraphics Ultima PF; BreezeSuite Software; and PreVent Flow Sensor; St. Paul, MN) determinations were performed in our PF outpatient laboratory utilizing our standard operating procedures. As noted above, predicted values for individual of normal stature were determined based on arm length [33] and evaluated in the BreezeSuite Software for the NHAINES III data base [34]. Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), Forced expiratory total volume (FEVTOT)/Forced Vital capacity (FVC)/Vital capacity (VC), predicted Forced expiratory total volume (%FEVTOT), FEV1/FEVTOT (timed forced expiratory volume/forced expiratory total volume), and %Predicted (FEV1/FEVTOT) were determined from the best of 3 spirometric tracings.

1.2 Impulse Ocillometry System (IOS)

IOS measures resistance (R) at different frequencies (R5-peripheral airway resistance; R20-central airway resistance) and reactance (movement of the air in the airways) (Komarow et al., 2011). The device used for the oscillatory measurements was the Master Screen-IOS device (E. Jaeger; Höchberg, Germany) [35,36,37]. For each impulse, 32 sample points were analyzed. Daily calibration using a calibration pump (3.0 ± 0.01 L SD, Jaeger; Höchberg, Germany) and a reference impedance of 0.2–2.5 kPa/l/s were performed. Briefly, small mechanical impulses were superimposed on the spontaneous breathing pattern. Through the phase relationship, the Zrs was partitioned into resistance (Rrs) and reactance (Xrs). Rrs included the airway, lung tissue, and chest wall resistance, whereas Xrs represented the balance of two (an elastic and an inertial) components, or the net effect of two opposite (a compliant and an inertial) components.

After a brief explanation, patients performed some practice trials. When the patient was feeling comfortable, study testing started. Subjects performed the test in a sitting position, breathing quietly for 15 to 30 seconds using an oval mouthpiece with the head in a neutral position, nose clips in place, and supporting both cheeks with help by the staff. The following parameters were measured: Rrs at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 35 Hz and resonant frequency (fRES) (i.e., the frequency at which the reactance crosses zero). Three replicate oscillatory values were used to calculate the mean and the coefficient of variation (CV) for Rrs5. Coherence value were used as a quality control parameter and the CV for Rrs5 is used as a reliability index. Measurements were discarded if the time-flow and volume pattern showed interruption of the oscillatory signal. It should be noted that the Jaeger software has established predicted values as a function of age, height and gender for individuals of typical stature [38].

1.3 Pneumotachography (PNT)

Air flow, CO2 graphs and oximetry signals were recorded using a pediatric/adult monitoring system (Novametrix Medical Systems, Wallingford, CT). Testing was performed to collect at least 10 uniform breaths and the data was stored for analysis, the breaths were collected from a long epoch (2–4 min). Measurements were recorded over time at the airway opening using a pneumotachometer via face mask; mask integrity was monitored for leaks (less than 10% tidal volume change throughout each breath) and a constant tidal volume breathing frequency history was observed for at least 10 breaths [25,26,27].

Airflow was measured with a low dead space volume pneumotachometer and integrated pressure transducer. End-tidal CO2 was calculated by algorithms incorporated into the monitoring system unit. Flow and CO2 graphs were analyzed in real time and after each measurement [22]. CO2 graphs were used for assessing airway obstruction. As an additional safety measurement, the transcutaneous saturation of oxygen (SpO2) was monitored simultaneously with a small sensor on the finger of the patient.

1.4 Respiratory Inductance Plethysmography (RIP)

RIP is a noninvasive respiratory evaluation approach which determines pulmonary ventilation or breathing by using thoracoabdominal motion analysis with markers of thoracoabdominal asynchrony (TAA).

Previous studies demonstrated how much degree of chest and abdominal excursions are out of phase due to respiratory abnormalities such as chest wall dysfunction, lung compliance abnormalities, and/or airway obstruction [39,40,41].

Changes in thoracicabdominal motion (TAM) correlated with changes in resistance and compliance in infants/children/adults with airflow obstruction and/or restrictive disorders. These changes in TAM and other TAM indices expressed the degree to which chest and ABD excursion are out of phase, or thoracoabdominal asynchrony (TAA). The size of the bands was chosen to fit comfortably; yet snug enough to obtain adequate recordings; any excess of band material was folded and pressed together using a plastic forceps (Devon, tyco/Healthcare, Princeton, NJ) in each band to avoid any unintentional change in position. Real-time raw signals and Konno–Mead loops were monitored during the test to ensure proper signal and adequate quality using RespiEvents software 5.2 g (Nims, Inc., Miami, FL). Figure-of-eight loops were discarded. Phθ, phase relation during total breath (PhRTB) and the percentage of rib cage contribution to the tidal volume (%RC) were analyzed. For the %RC, an appropriate sized pneumotachometer were used along with a CO2SMO (Carbon dioxide and respiratory rate) PFT monitor (Respironics, Wallingford, CT) to measure actual tidal in milliliters. PFT methods included RIP using the SomnoStarPT Unit (Sensormedics, Yorba Linda, CA) and inductance bands (RespiBands Plus; VIASYS Respiratory Care, Yorba Linda, CA).

Initially, patients underwent RIP, in which the relationship between thoracic and abdominal contributions to the respiratory effort was assessed [38,42,43,25,26]. Bands containing inductive coils were carefully placed around the ribcage at the level of the axillae and around the abdomen mid-way between the xiphisternal junction and the umbilicus. We used an uncalibrated RIP method for phase and synchrony evaluations. The Respitrace device was used to construct Lissajous loops and for calculation of phase angle between the ribcage and abdominal movement associated with respiration.

Reported phase angle measurements and other indices of asynchrony were based on the average of at least 10 uniform Lissajous loops. The signals from the RIP bands around the rib cage and the abdomen were treated mathematically as sine waves. The phase angle was calculated with RespiEvents software 5.2 (NIMS, Miami, FL). This parameter and other thoracoabdominal markers expressed the degree to which chest and abdominal excursion was out of phase. Normally, the rib cage moved outward during inspiration completely in phase with the outward movement of the abdomen (in phase). With progressive increase in the work of breathing, like in airflow obstruction, the rib cage lagged behind abdominal movement (out of phase) becoming asynchronous [27].

Recordings were made with the patient in the sitting position. During the test, raw signals and Konno-Mead (Lissajous) loops were monitored to ensure adequate signal quality and to select suitable breathing sequences for analysis with RespiEvents. Phase angle (delay between the thoracic and abdominal excursions), and rib cage % of tidal volume (%RC) were measured.

Statistical analysis

The influence of age on pulmonary resistance (Rrs5 and Rrs20) was described using the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. To specifically assess the effect of puberty on each of pulmonary resistance, phase angle and % rib cage, we categorized patients into pre- and post-puberty groups and assessed the mean pulmonary resistance between these two age groups for each of the three aforementioned outcomes using the two sample unpaired student t test assuming unequal variance at two time points: Rrs5 and Rrs20. The same hypothesis test was also used to contrast the difference between all Morquio patients’ performance at Rrs5 and Rrs20, regardless of age. To simultaneously examine the relationship between resistance at Rrs5 and Rrs20 among the two age groups, we performed a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All tests were two-sided. The statistical significance for the individual tests was set at 5%. The relationship between the resistance (at each of Rrs5 and Rrs20) and % predicted vital capacity was modeled using the exponential model. The analyses were made using R software (R Core Team 2014) [44].

Results

Twenty-two patients participated in this study ranged in age from 3 to 40 years old (7 males, 15 females). Of these patients, 22 (100%) were compliant for RIP and PNT, 18 (81.8%) for IOS and 17 (77.3%) were compliant with spirometry testing.

Vital signs

All subjects had normal vital signs at rest including > 95% oxygen saturation, end tidal CO2 (38–44 mmHg), and age-appropriate heart rates (mean= 98.3, standard deviation=19) (two patients older than 18 years of age were deviated- 121 and 131). Normal predicted values (NHANES III) were matched for age, gender, and height (as converted from arm length due to the skeletal dysplasia of the patients) as compared to individuals of normal stature [33].

Spirometry

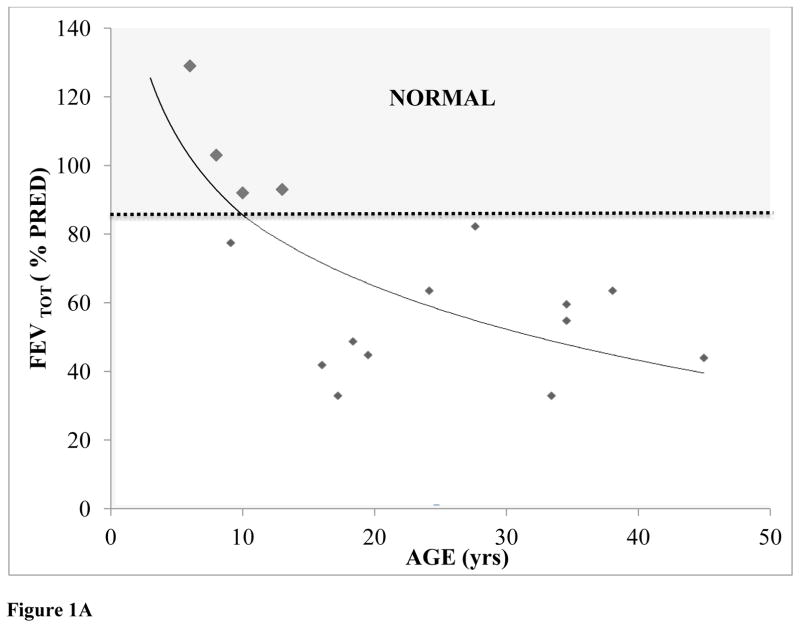

Predicted forced expiratory volume total (%FEVTOT) was normal until 10 years of age; however, %FEVTOT decreased with age, showing a significant negative correlation between %FEVTOT and age (FEVTOT=−33.16 ln(Age)+161.88; R2=0.475) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Figure 1A: % Predicted FEVTOT plotted as a function of patient age (N=16).

* Not all 22 patients were compliant for spirometry

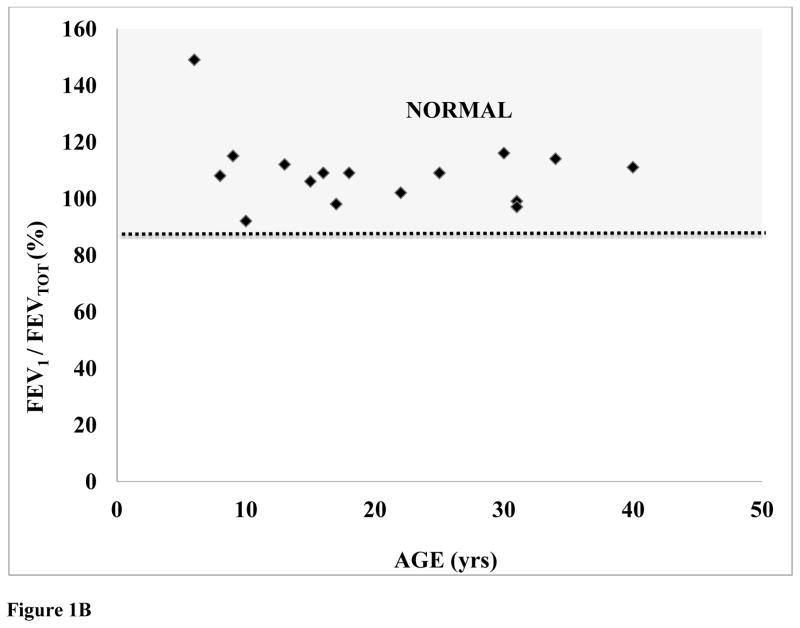

Figure 1B: %Predicted (FEV1 / FEVTOT) plotted as a function of patient age (N=16).

FEV1/FEVTOT ratio was not correlated with age (p=0.354386). Furthermore, %FEVTOT was negatively correlated with body weight, indicating that the higher BMIs in patients with Morquio syndrome provide a detrimental impact on overall respiratory function. However, in all ages and both genders, the patients with Morquio syndrome had similar values of FEV1/FEVTOT, compared with those of age- and gender-matched controls (Fig. 1B).

This finding is more enhanced when we observed that patients with Morquio syndrome as a group (all ages and both genders) have reduced %FEVTOT (72.8 ± 6.9 SE%) but normal FEV1/FEVTOT (110.0 ± 3.2 SE %).

Impulse Ocillometry System (IOS)

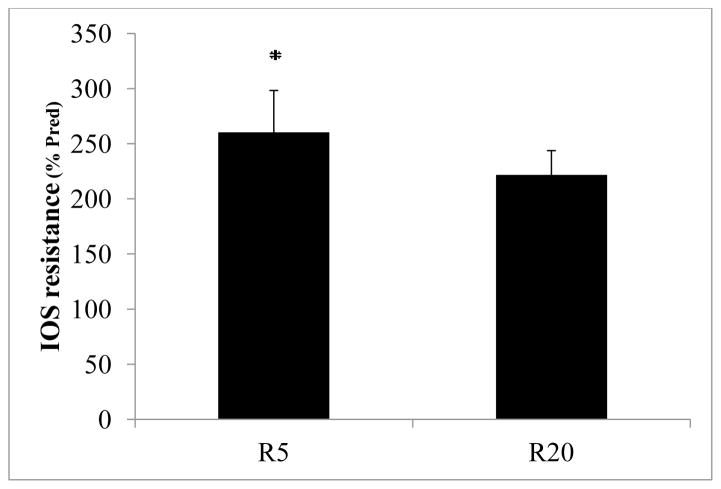

18 patients were combined (pre and post puberty) since there was no effect of age on R5 or R20. Independent of gender, the results of IOS resistance demonstrated a frequency dependence (change in resistance with aging such that resistance at higher frequencies is less than resistance at lower frequencies) in that R20 was less (p< 0.001) than R5, where R20 is 2.2 fold and R5 is 2.5 fold predicted values, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

IOS Resistance (%Pred; Mean ± SE) plotted for 5 Hz and 20 Hz representing peripheral and central resistance, respectively (n = 18) (p< 0.001)

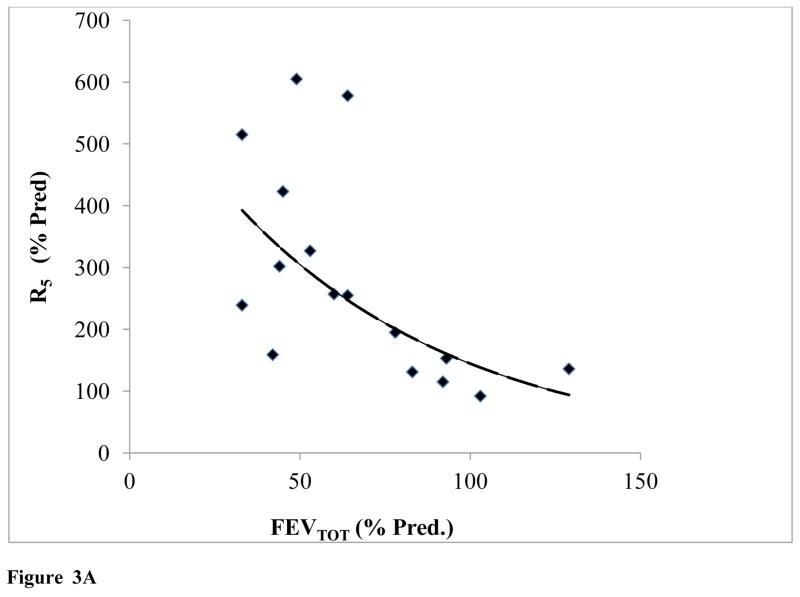

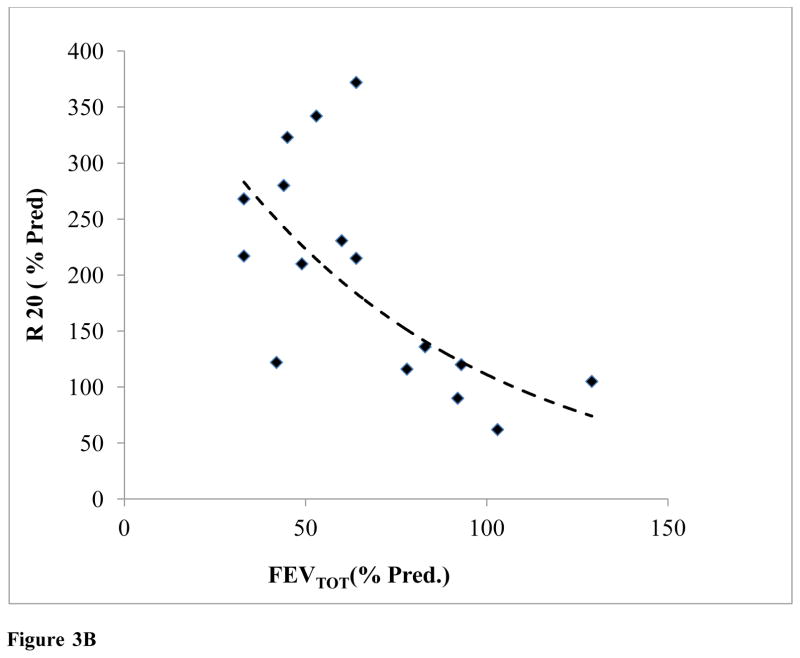

It should be noted that predicted resistance standards for IOS values, were generated for individuals of average stature, age, and gender for each patient; as such there was a clear relationship between IOS R5 and R20 with %FEVTOT (Fig. 3A, 3B).

Figure 3.

Figure 3A: IOS Resistance (R5) plotted as a function of FEVTOT (N=16) (y=777.92e−0.018x; R2=0.57)

Figure 3B: IOS Resistance (R20) plotted as a function of FEVTOT (N=16) (y=493.14e-0.015x; R2=0.57)

As lung volume increased, both R5 and R20 decreased exponentially, R5= 777.92e−0.018Age (R2 = 0.57) and R20 = 493.14e−0.015Age (R2 = 0.57).

Pneumotachography (PNT)

All parameters analyzed by PNT (air flow, CO2 and oximetry) were normal in comparison with age and gender matched controls. As noted above, oxygen saturations measured by pulse oximetry was > 95% oxygen saturation, end tidal CO2 was in the range of (38–44 mmHg), and age-appropriate heart rates were seen in all subjects (mean=98.3, standard deviation= 19; apart from 2 patients-121 and 131).

Respiratory Inductance Plethysmography (RIP)

Mean ± SEM results were as follows: Phase angle (32.5 ± 16.5 Degrees), %RC (41.6 ± 12.7%), f RES (average = 25.5 ± 6.8). The resonant frequency, phase angle (Ø) and %RC were all within normal limits when compared with normal healthy values (corrected with average stature, gender, and age) (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

RIP Summary (Phase angle degrees and % RIB cage)

Discussion

Conventional spirometry may not be an appropriate approach to assess lung function in young children and children with disabilities [18,29]. Also, spirometry is considered and effort-dependent test. In the Morcap study 66.3% of the patients were compliant with spirometry (FVC) [45]. Further, the predicted values are based on age-matched controls for normal height and normal chest wall. These data does not include unusual chest development, which makes the interpretation of spirometry even harder in Morquio patients.

Herein we have performed non-invasive and conventional PFTs in patients with Morquio syndrome, which provides a unique “experimental model” associated with severe skeletal dysplasia. We have demonstrated the following:1) all 22 Morquio syndrome patients have normal vital signs at rest including oxygen saturation, end tidal CO2, and age-dependent heart rate (apart from 2 patients), 2) there are reductions in FEVTOT starting at age 10 [45] 3) the FEV1/FEVTOT ratios are within normal predicted range, 4) non-invasive assessment of IOS resistance demonstrated that peripheral (R5) and central airway resistance (R20) was not a function of age (pre vs. post puberty), where R5 was higher than R20 5) air flow and CO2 values were normal, 6) IOS resistances were consistent with normal respiratory physiology when correlated with lung volume, and 7) RIP reveals that the skeletal dysplasia, a characteristic finding in Morquio syndrome, provides a limited impact to the worsening respiratory function with age if corrected for stature. Our results were consistent with higher values of R5 in younger patients than R20 due to frequency dependence [46,47]. As expected, as lung volume increases, resistance (R5 and R20) decreases due to the increase in airway caliber [48]. A greater number of Morquio patients should be analyzed to elucidate the age effect on resistance in this patient population. Nonetheless, there is a trend of worsening lung function in young patients to adulthood.

Morquio syndrome patients display restrictive lung characteristics due to their small lungs, stature and skeletal dysplasia, compared with the age-matched controls; however, there were no clinical symptoms or dysfunction consistent with restrictive/obstructive lung disease (normal oxygen saturation, CO2 values, synchronous breathing pattern- abdomen and rib cage move simultaneously in concert). Based on predicted values for spirometry, without taking into account that Morquio patients do not have normal structure nor normal chest wall, the patients would present a restrictive lung disease pattern, however considering these issues and the results from the non-invasive PFTs our results are not consistent with restrictive and obstructive lung disease, suggesting that the Morquio patients analyzed here have “small lungs” due to their small thoracic size.

The present series of pulmonary function tests demonstrated that the Morquio patients studied herein have normal functional lungs. However, it should be noted that since all of the testing procedures were analyzed at rest, these patients might not have a substantial oxygen reserve in the event the patients are stressed due to exercise or respiratory disorders.

According to our findings of normal lungs in this patient’s population, some of the associated complications in Morquio syndrome as: difficulty during anesthesia, cervical spinal cord compression, tracheobronchial abnormalities with tortuous airways, large tongue, adenoidal, tonsillar and vocal cord hypertrophies; could be associated with tracheal/anatomical abnormalities and obstructive narrow upper airways.

Non-invasive assessment of IOS resistance demonstrated that R5 and R20, indicative of peripheral and central resistances, respectively, were higher than predicted compared to normal values for patients with average stature. As previously demonstrated by Briscoe et al. (1958) [48] resistance is correlated with lung volume such that as lung volume increases, resistance decreases. Both R5 and R20 demonstrated a similar relationship with lung volume. Finally, with respect to non-invasive RIP studies, we have demonstrated that the resonant frequency, phase angle (Ø) and %RC in Morquio syndrome patients were within normal limits when compared to normal healthy values (average stature, gender, age). Typically, when any of these parameters are out of range, it is associated with mechanical dysfunction of the lungs and chest wall due to compliance or resistance abnormalities [27].

Hence, the validation of non-invasive testing with vital signs has provided valuable clinical information about the pulmonary status of Morquio patients. All the non-invasive PFTs were validated with conventional spirometry, and for the patients that were not able to perform spirometry (younger, unable or lack of cooperation) we would not have any clinical evaluation in pulmonary function.

This study has illustrated the first systematic study of non-invasive pulmonary testing in Morquio syndrome, a prototypical skeletal dysplasia, with deformed upper airway, small rib cage, and short stature [49]. Taken together, these data support the concept that Morquio syndrome patients have small, but normal functioning lungs, as previously demonstrated in patients with achondroplasia in which the lung function was normal for small adults of similar age [50,51, 52]. The small lung is most likely as a result of the skeletal dysplasia providing an impact on the developing lung and chest wall. Thus, we hypothesize that the lungs may not be the main tissue affected by Morquio syndrome nor the organ that would most likely respond to therapeutic approaches (ERT and HSCT) which may not demonstrate a marked impact in lung function unless the treatment results in an improvement in lung/chest growth or prevention of lung disease associated with aging. This study is limited by the overall small population of Morquio patients in the United States and it may not be representative of the entire MPS IV population; however, we were successful in testing 22 patients ranging in age from 3 to 40 years of age.

Therefore, a greater number of patients with broad clinical phenotypes (from mild to severe) and with various stages of the disease need to be studied to further strengthen our results, and in order to minimize risk of surgery and anesthesia. It is also critical to expand the population to conclude how frequent patients with Morquio syndrome have obstructive and/or restrictive disease.

In conclusion, patients with Morquio syndrome have small lungs, but do not always exhibit signs and dysfunction of restrictive and obstructive lung disease as presented in prior case reports [18, 19, 15, 45, 20, 21]. The proposed non-invasive pulmonary function testing program provides physicians and the Morquio community critical information to clarify key clinical conditions and to monitor therapeutic effects, which can be applied to other types of MPS and skeletal dysplasia.

Highlights.

Non-invasive PFT are tested for patients with Morquio syndrome.

Non-invasive PFT covers younger and/or physically handicapped patients.

Results of conventional spirometry and non-invasive PFT were correlated.

Morquio patients do not always present restrictive and/or obstructive lung disease.

Proposed PFT can be applied to other types of MPS

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Austrian MPS Society and International Morquio Organization (Carol Ann Foundation). T.S. and S.T. were supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of NIH under grant number P20GM103464. F.K. was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico from Brazil (CNPq).

Abbreviation list

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BMI

body mass index

- CO2

carbon dioxide

- CS

chrondroitin sulfate

- C6S

chrondroitin-6-sulfate

- CV

coefficient of variation

- ERT

enzyme replacement therapy

- FDA

food and drug administration

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in one second

- FEVTOT

forced expiratory volume total

- FVC

forced Vital capacity

- GAGs

glycosaminoglycans

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- IOS

impulse oscillometry

- KS

keratan sulfate

- MPS

mucopolysaccharidosis

- MPS IVA

mucopolysaccharidosis IVA

- MPS IVB

mucopolysaccharidosis IVB

- NHANES

National health and nutrition examination survey

- GALNS

N-acetyl-galactosamine-6-sulfate-sulfatase

- PhRTB

phase relation during total breath

- %FEVTOT

predicted Forced expiratory volume total

- PFTs

pulmonary function tests

- PNT

pneumotachography

- Xrs

reactance

- Rrs

resistance

- Rrs5

resistance at 5 Hertz

- Rrs20

resistance at 20 Hertz

- fRES

resonant frequency

- RIP

respiratory inductance plethysmography

- TAA

thoracoabdominal asynchrony

- TAM

thoracicabdominal motion

- FEV1/FEVTOT

timed forced expiratory volume/forced expiratory volume total

- TLC

total lung capacity

- SpO2

transcutaneous saturation of oxygen

- VC

vital capacity

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Francyne Kubaski, Shunji Tomatsu, Pravin Patel, Tsutomu Shimada, Li Xie, Eriko Yasuda, Robert W. Mason, William G. Mackenzie, Mary Theroux, Michael Bober, Helen M. Oldham, Tadao Orii, Thomas H. Shaffer declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Compliance with Ethics guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their guardians and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institution (750932).

Contributions to the Project:

Francyne Kubaski: She has contributed to the concept of project, the planning, data analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article.

Shunji Tomatsu: He is a Principal Investigator and is responsible for the entire project. He has contributed to the concept of the project, planning, analysis of data, and reporting of the work described in the article.

Pravin Patel: He has contributed to the planning, data analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article.

Tsutomu Shimada: He has contributed to the planning, data analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article.

Li Xie: She has contributed to data analysis of the work described in the article.

Eriko Yasuda: She has contributed to the planning, data analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article.

Robert W. Mason: He has contributed to the planning, data analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article.

William G. Mackenzie: He has contributed to recruiting the patients, data analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article.

Mary Theroux: She has contributed to recruiting the patients, data analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article. She is an anesthesiologist.

Michael Bober: He has contributed to recruiting the patients, data analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article. He is a clinical geneticist.

Helen M. Oldham: She is a respiratory therapist with extensive pulmonary function experience and is responsible for testing all subjects in this study.

Tadao Orii: He has contributed to the planning, data analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article.

Thomas H. Shaffer: He is a Principal Investigator and is responsible for the entire project. He has contributed to the concept of the project, planning, analysis of data, and reporting of the work described in the article.

The content of the article has not been influenced by the sponsors. Editorial assistance to the manuscript was provided by Michelle Stofa at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children. The views and opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies and had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All the authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflict of Interest. T.H.S. and S.T. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Morquio L. Sur une forme de dystrophie osseuse familial. Archives de médicine des infants, Paris. 1929;32:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brailsford JF. Chondro-osteo-dystrophy. Roentgenopgraphic & clinical features of a child with dislocation of vertebrae. Am J Sur. 1929;7:404–410. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, et al. Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. JAMA. 1999;281:249–254. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Applegarth DA, Toone JR, Lowry RB. Incidence of inborn errors of metabolism in British Columbia, 1969–1996. Pediatrics. 2000;105:e10. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson J. Incidence of the mucopolysaccharidoses in Northern Ireland. Hum Genet. 1997;101:355–358. doi: 10.1007/s004390050641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poorthuis BJ, Wevers RA, Kleijer WJ, et al. The frequency of lysosomal storage diseases in The Netherlands. Hum Genet. 1999;105:151–156. doi: 10.1007/s004399900075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinto R, Caseiro C, Lemos M, et al. Prevalence of lysosomal storage diseases in Portugal. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:87–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dung VC, Tomatsu S, Montaño AM, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA: Correlation between genotype, phenotype and keratan sulfate levels. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2013;110:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuda E, Fushimi K, Suzuki Y, et al. Pathogenesis of Morquio A syndrome: an autopsied case reveals systemic storage disorder. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomatsu S, Montaño AM, Oikawa H, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IVA (Morquio A Disease): Clinical Review and Current Treatment: A Special Review. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2011;12:931–45. doi: 10.2174/138920111795542615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomatsu S, Mackenzie WG, Theroux MC, et al. Current and emerging treatments and surgical interventions for Morquio A Syndrome: A review. Research and Reports in Endocrine Disorders. 2012;2:65–77. doi: 10.2147/RRED.S37278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Northover H, Cowie RA, Wraith JE. Mucopolysaccharidosis type IVA (Morquio Syndrome): a clinical review. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1996;19:357–65. doi: 10.1007/BF01799267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montaño AM, Sukegawa K, Kato Z, et al. Effect PF ‘attenuated’ mutations in mucopolysaccharidosis IVA on molecular phenotypes of N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:758–767. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0702-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montaño AM, Tomatsu S, Brusius A, et al. Growth charts for patients affected with Morquio A disease. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146:1286–1295. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendriksz CJ, Harmatz P, Beck M, et al. Review of clinical presentation and diagnosis of mucopolysaccharidosis IVA. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2013;110:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Möllmann C, Lampe CG, Müller-Forell W, et al. Development of a Scoring System to evaluate the severity of Craniocervical spinal cord compression in patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio A Syndrome) JIMD Rep. 2013;11:65–72. doi: 10.1007/8904_2013_223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmatz P, Mengel KE, Giugliani R, et al. The Morquio A Clinical assessment program: baseline results illustrating progressive, multisystemic clinical impairments in Morquio A subjects. Mol Genet Metabol. 2013;109:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muhlebach MS, Wooten W, Muenzer J. Respiratory manifestations in Mucopolysaccharidoses. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 2011;12:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger KI, Fagondes SC, Giugliani R, et al. Respiratory and sleep disorders in mucopolysaccharidosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36:201–210. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9555-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomatsu S, Alméciga-Díaz CJ, Barbosa H, et al. Therapies of Mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio A Syndrome) Expert Opinion on Orphan Drugs. 2013;1:805–818. doi: 10.1517/21678707.2013.846853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin SP, Shih SC, Chuang Ck, et al. Characterization of pulmonary function impairments in patients with mucopolysaccharidoses-changes with age and treatment. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2014;49:277–284. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller TL, Blackson TJ, Shaffer TH, et al. Tracheal gas insufflation-augmented continuous positive airway pressure in a spontaneously breathing model of neonatal respiratory distress. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2004;38:386–395. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beydon N, Davis SD, Lombardi E, et al. An official American thoracic society/european respiratory society statement: pulmonary function testing in preschool children. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2007;175:1304–1345. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-642ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Ent CK, Brackel HJL, van Laag JD, et al. Tidal breathing analysis as a measure of airway obstruction in children three years of age and older. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1996;153:1253–1258. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.4.8616550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagaman MJ, Shutack JG, Moomjian AS, et al. Improved oxygenation and lung compliance with prone positioning of neonates. Journal of Pediatrics. 1979;94:787–791. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfson MR, Greenspan JS, Deoras KS, et al. Effect of position on the mechanical interaction between the rib cage and abdomen in preterm infants. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1992;72:1032–1038. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.3.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen JL, Greenspan JS, Deoras KS, et al. Interaction between chest wall motion and lung mechanics in normal infants and infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1991;11:37–43. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950110107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer OH, Clayton RG, Sr, Jawad AF, et al. Respiratory inductance plethysmography in healthy 3- to 5-year-old children. Chest. 2003;124:1812–1819. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van der Wiel E, Postma DS, van der Molen T, et al. Effects of small airway dysfunction on the clinical expression os asthma: a focus on asthma symptons and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Allergy. 2014;69:1681–8. doi: 10.1111/all.12510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mineshita M, Shikama Y, Nakajima H, et al. The application of impulse oscillation system for the evalutation of treatment effects in patients with COPD. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 2014;202:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crim C, Celli B, Edwards LD, et al. Respiratory system impedance with impulse oscillometry in healthy and COPD subjects: ECLIPSE baseline results. Respiratory Medicine. 2011;105:1069–78. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka H, Hozawa S, Kitada J, et al. Impulse Oscillometry; Therapeutic impacts of transdermal long-acting beta-2 agonist patch in elderly asthma with inhaled corticosteroid alone. Allergology International. 2012;61:385–92. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.12-RAI-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chhabra SK. Using arm span to derive height: impact of three estimates of height interpretation of spirometry. Ann Thorac Med. 2008;3:94–9. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.39574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NHANES III, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Spirometry Training Program. 2010 http://http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/spirometry/nhanes.html.

- 35.Hellinckx J, De Boeck K, Bande-Knops J, et al. Bronchodilator response in 3–6.5 years old healthy and stable asthmatic children. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:438–443. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berdel D, Magnussen H, Bockler M. Normal values of respiratory resistance in childhood (oscillation method) (author’s transl) Prax Klin Pneumol. 1979;33:35–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith HJ, Reinhold P, Goldman MD. Forced oscillation technique and impulse oscillometry. Eur Respir Mon. 2005;31:72–105. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaffer TH, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M, Arcinue E, et al. Pulmonary function in premature lambs during the first few hours of life. Respir Physiol. 1976;28:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(76)90037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poole KA, Thompson JR, Hallinan HM, et al. Respiratory inductance Plethysmography in healthy infants: a comparison of three calibration methods. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:1084–90. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16f11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown K, Aun C, Jackson E, et al. Validation of respiratory inductance plethysmography using the qualitative diagnostic calibration method in anesthetized infants. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:935–943. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12040935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neumann P, Zinserling J, Haase C, et al. Evaluation of Respiratory Inductance Plethysmography in controlled ventilation. Chest. 1998;113:443–51. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shephard RJ. Pneumotachographic measurement of breathing capacity. Thorax. 1955;10:258–268. doi: 10.1136/thx.10.3.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grenvik A, Hedstrand U, Sjögren H. Problems in pneumotachography. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1966;10:147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1966.tb00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2014. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harmatz PR, Mengel KE, Valayannopoulos V, et al. Longitudinal analysis of endurance and respiratory function from a natural history study of Morquio A syndrome. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2015;114:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stanescu D, Moavero NE, Veriter C, et al. Frequency dependence of respiratory resistance in healthy children. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1979;47:268–72. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cuijpers CE, Wessling G, Swaen GM. Frequency dependence of oscillatory resistance in healthy primary school children. Respiration. 1993;60:149–54. doi: 10.1159/000196191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Briscoe WA, DuBois AB. The relationship between airway resistance, airway conductance and lung volume in subjects of different age and body size. J Clin Invest. 1958;37:1279–1285. doi: 10.1172/JCI103715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Semenza GL, Pyeritz RE. Respiratory complications of mucopolysaccharide storage disorders. Medicine (Baltimore) 1988;67:209–19. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198807000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stokes DC, Pyeritz RE, Wise RA, et al. Spirometry and Chest Wall Dimensions in Achondroplasia. CHEST. 1988;93:365–369. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berkowitz ID, Raja SN, Bender KS, et al. Dwarfs: Pathophysiology and Anesthetic implications. Anesthesiology. 1989;73:739–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stokes DC, Wohl MEB, Wise RA, et al. The Lungs and Airways in Achondroplasia. Chest. 1990;98:145–152. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]