Abstract

Quality-based care is a hallmark of physical therapy. Treatment effectiveness must be evident to patients, managers, employers, and funders. Quality indicators (QIs) are tools that specify the minimum acceptable standard of practice. They are used to measure health care processes, organizational structures, and outcomes that relate to aspects of high-quality care of patients. Physical therapists can use QIs to guide clinical decision making, implement guideline recommendations, and evaluate and report treatment effectiveness to key stakeholders, including third-party payers and patients. Rehabilitation managers and senior decision makers can use QIs to assess care gaps and achievement of benchmarks as well as to guide quality improvement initiatives and strategic planning. This article introduces the value and use of QIs to guide clinical practice and health service delivery specific to physical therapy. A framework to develop, select, report, and implement QIs is outlined, with total joint arthroplasty rehabilitation as an example. Current initiatives of Canadian and American physical therapy associations to develop tools to help clinicians report and access point-of-care data on patient progress, treatment effectiveness, and practice strengths for the purpose of demonstrating the value of physical therapy to patients, decision makers, and payers are discussed. Suggestions on how physical therapists can participate in QI initiatives and integrate a quality-of-care approach in clinical practice are made.

Like other health professions, physical therapy must move from quantity-based care or a fee-for-service model to quality-based care. It is increasingly common for both public and private payers to require some measure of effectiveness before approving treatment or payment.1,2 National benchmarking and public reporting on the quality of care are seen in many countries. In the United States, the movement toward high-quality, physician-focused health care is well established. Numerous government, nonprofit, and independent agencies have identified areas of population health and health care in which changes are needed; have established standards of care and health outcomes; and have created tools with which to measure, monitor, and report on quality of care at system, organization, facility, and individual provider levels.3,4 Similar quality reporting programs also are operating in Canada,5 the United Kingdom,6 Australia,7 and other European countries.8 To encourage clinicians to meet clinical benchmarks, some countries have instituted financial incentives to providers, in the form of “pay-for-performance” systems.4,9,10 One approach to promoting high-quality care and achieving benchmarks is the implementation of quality indicators (QIs) that specify the minimum standard of care. Although the majority of available and endorsed QIs have been developed for physicians and medical interventions and are applicable to hospital and primary care settings, various indicators are relevant to physical therapy and rehabilitation practice.

In 2013, the chief executive officer of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association (CPA), Michael Brennan, stated that “while this change [to quality-based care] is inevitable for the entire profession, the decision to move forward belongs to each practitioner.”11 Brennan further encouraged clinicians to make a personal commitment to increase accountability and quality of care rather than rely solely on extrinsic drivers, such as payers' refusal of payment or financial penalties in the absence of documented treatment outcomes and quality data. It is widely accepted that the quality of health care, including rehabilitation, should be systematically assessed and evaluated.12 At present, provincial health insurance plans or national health insurance programs in Canada do not have quality reporting requirements for physical therapists. However, the reporting of standardized outcome measure data by physical therapists is mandated in at least one province and, to a limited extent, among some third-party payers (Kate Rexe, Manager, Policy and Government Relations, CPA; personal correspondence; January 22, 2015). Physical therapists must be motivated and ready to embrace the quality-of-care movement individually and as a profession.

The aims of this perspective article are to introduce the value and use of QIs to guide clinical practice and health service delivery; to outline a framework to develop, select, implement, measure, and report QIs; and to describe the application of this framework and lessons learned in the development of QIs for total joint arthroplasty (TJA) rehabilitation. Our group recently completed the initial steps in developing QIs for rehabilitation across the continuum of care for patients undergoing elective TJA (results are to be published elsewhere).

Quality Health Care and QIs

Physical therapists can use QIs to adopt a quality-of-care approach in practice.13 Quality indicators are specific, measurable aspects of health care that define the minimum standard of care patients can expect to receive for a given health condition or treatment intervention. In the United States, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) define QIs as “tools that help us measure or quantify health care processes, outcomes, patient perceptions, and organizational structure and/or systems that are associated with the ability to provide high-quality health care and/or that relate to one or more quality goals for health care.”4 The Institute of Medicine in the United States defines quality health care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”3 Quality indicators can be used to identify care gaps, inform health care policy and health service delivery, support accountability, promote transparency in health care, and prioritize quality improvement initiatives.14,15

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine identified 6 national health care quality reporting categories that represent high-quality health care: safety, timeliness, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and patient centeredness.3 International health care agencies have adopted similar quality-of-care domains in their prioritization of health care planning, funding, and benchmarking initiatives.5–8 When creating QIs, developers typically link the quality statement to one or more of these domains. A health care system that achieves major gains in these 6 areas will be far better at meeting the needs of patients.3 Patients will benefit from care that is safe, reliable, accessible, coordinated, and responsive to their needs. Clinicians will also benefit by providing better care for their patients and achieving greater job satisfaction for themselves.3

In the field of knowledge translation, QIs are considered a tertiary knowledge product that helps to mobilize other knowledge products (ie, practice guidelines) into practice and evaluate the impact of their implementation.16 Quality indictors differ from practice guidelines or best-practice recommendations in that they permit the assessment and monitoring of gaps related to the structures (eg, rehabilitation provider staffing levels, availability of equipment), processes (eg, adherence to rehabilitation best practices, delivery of services), or outcomes (eg, functional status, quality of life, mortality) of care.16,17 Quality indicators operationalize practice guidelines by transforming recommendations into actionable and measurable statements, often identifying the clinical context, timing, and target audience in the process. For example, the 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for the management of knee osteoarthritis (OA) recommend “strongly” that patients with knee OA should lose weight if they are overweight.18 In contrast, in an earlier QI set for OA, the Arthritis Foundation stated, “IF a patient has symptomatic OA of the knee or hip and has been overweight for 3 years THEN he/she should receive referral to a weight loss program.”19(p539) Compared with the guideline statement, the QI statement is less open to interpretation and is more amenable to objective measurement and reporting of whether the process indicator was met.

Indicators for arthritis and related conditions have been developed and validated for the pharmacological and nonpharmacological management of OA,19–22 hip and knee OA,23 integrated knee OA care,24 rheumatoid arthritis,22,25,26 gout,27 osteoporosis,28 and surgical and medical processes of care for hip and knee TJA.29 Rehabilitation-specific QIs also have been developed for other chronic conditions.30,31

Value and Use of QIs in Physical Therapist Practice

Physical therapists can use QIs as a tool to guide clinical decision making, implement guideline recommendations, evaluate treatment effectiveness, and report achievement of benchmarks to key stakeholders, including third-party payers and patients. Patients and their family members can use QIs to make informed decisions about their health care options, select providers and programs, and monitor the quality of care received. Rehabilitation managers and senior decision makers can use QIs to assess care gaps and benchmark achievement; guide quality improvement initiatives; undertake strategic planning; and compare health service delivery across providers, clinical settings, and regions. Policy makers can use QIs to set national benchmarks, determine resource allocation and pay-for-performance metrics, and inform health care policy.14,16

Despite the growing availability of QIs relevant to physical therapy in the past decade, Jette and Jewell32 reported low use (4%–51%) of Medicare-approved QIs pertaining to primary and secondary prevention activities among 2,544 members of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). They concluded that physical therapists, despite working as direct-access health care professionals, did not perceive themselves as key providers of these prevention services and thus saw less value in integrating them into practice. With the growing movement toward performance-based practice and compensation, it is important that physical therapists understand the value of incorporating and reporting QIs relevant to their practices, patients, and third-party payers.

Evidence from mostly medically focused quality improvement initiatives shows that implementing and measuring QIs result in improvements in patient outcomes attributable to improved processes of care.33 For instance, QIs developed for low back pain showed that better adherence to the Dutch physical therapy low back pain guidelines was associated with less pain, disability, and costs.34 The implementation of medical and rehabilitation QIs in an acute stroke care unit resulted in fewer serious complications and improved patient independence at discharge.35 Auditing and reporting of QI data to nurses in a National Health Services hospital in the United Kingdom reduced patient falls (26%) and increased adherence to infection control measures (90% adherence).36 According to data from more than 8,000 electronic medical records of patients treated by primary care physicians in the Netherlands, meeting process QIs for lipid-lowering treatment predicted lower risks of cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes.37 Although these initiatives have shown effectiveness, the impact of regular QI monitoring and reporting on health care policy development and health care system reform is less clear.38

Framework for Developing QIs

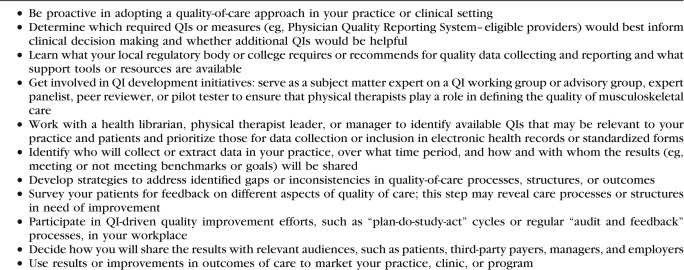

The involvement of physical therapists in the development of rehabilitation-specific QIs is imperative. For physical therapists to participate, they must have an understanding of the QI process. The main steps in QI development and implementation are defining the target audience; determining the clinical area to evaluate; identifying existing QIs or, in their absence, developing QIs; assessing existing or new QIs; and collecting and reporting QI data (Tab. 1).13–15 The decision about the clinical area for which QIs are to be developed and implemented is based on a number of factors, including regulatory requirements, payer demands, public concerns, and importance of the health care issue.13,14,39 A health care area is important and may be prioritized for QI development if it affects many patients (ie, prevalence and number of medical procedures), is associated with high mortality or morbidity rates, shows variations in care and outcomes, and is costly to the health care system.14,39,40 Other important considerations include whether there are opportunities to change clinical practice and improve quality of care and patient outcomes within the clinical area and whether related interventions are within the control of providers whose performance is being measured.39

Table 1.

a AGREE II-QI=modified version of the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation.

Developing QIs

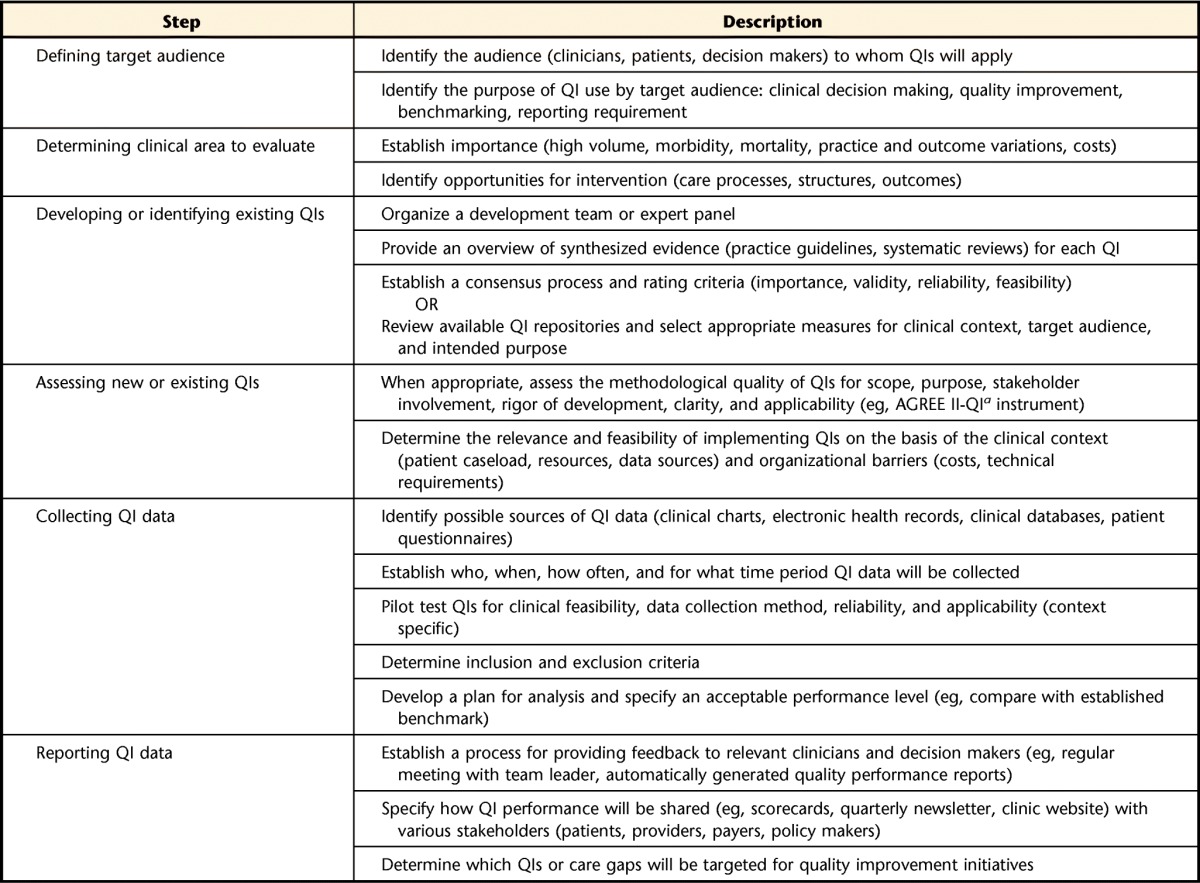

Quality indicators should be based on a rigorous, transparent, and systematic approach to ensure the development of high-quality measures, as they are used to judge the quality of care provided and, in some cases, to determine provider compensation.17,41 The most widely researched, rigorous, and transparent method of soliciting and synthesizing expert opinion and evidence17 to generate QIs is the RAND Health and University of California—Los Angeles (RAND/UCLA) Appropriateness Method.42 In this approach, the synthesized evidence is used to generate QI statements with the “if-then-because” format to specify context, clinical characteristics, process of care, and expected outcomes.42 The candidate QIs are then provided to an expert panel of all relevant stakeholders, including the clinicians involved in providing the care, decision makers, and patients, to ensure diverse perspectives.14,42 Panelists are instructed to rate each QI on the basis of one or more criteria, such as importance, validity, and reliability, using a 9-point or similar rating scale (Tab. 2).42 The traditional RAND/UCLA approach next involves a moderated, face-to-face meeting (round 2) in which initial results are discussed, with a focus on the indicators with the greatest variability in ratings. The panel then participates in another, anonymous round of rating (round 3) to determine the final set of QIs. Other well-established methodological approaches to developing QIs include extracting QI statements directly from existing clinical practice guidelines,17,41 generating QIs from systematic reviews,43 and combining various forms of high-quality evidence with expert consensus.44 Quality indicators with high ratings for importance, validity, and other predetermined criteria are then pilot tested in clinical settings and with targeted practitioners to further establish feasibility and applicability.14,15,42

Table 2.

Identifying Existing QIs

The process of developing QIs is time-consuming and expensive because of the numerous steps required. Therefore, clinicians and decision makers are encouraged to identify and select existing, endorsed QIs relevant to their health care area (eg, primary care, prevention), practice setting (eg, acute care, outpatient care), and patient demographics (eg, older adults, children) and diagnoses (eg, OA, osteoporosis). For QIs and quality measures to be endorsed by most federal agencies and to be widely accepted and implemented, they must adhere to the same basic criteria as those applied to their development (Tab. 2).5,39,45

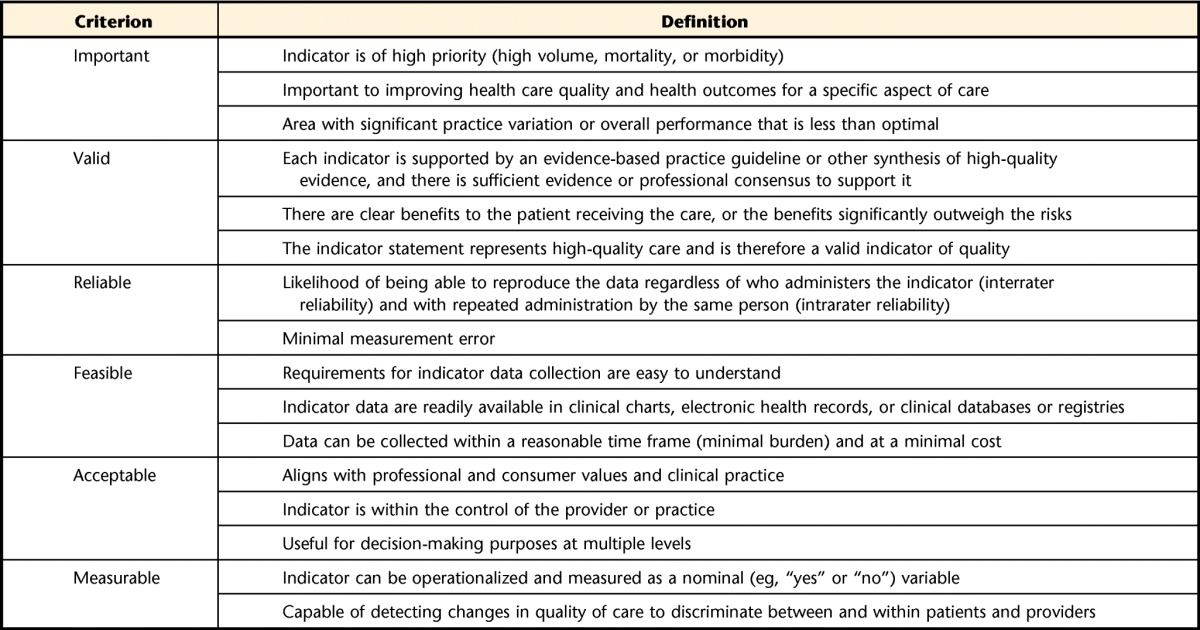

In the United States, the main repositories from which physical therapists can select QIs and quality measures are the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),45 CMS,4 National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (NQMC),46 and National Quality Forum (NQF).39 Each is briefly described below. Other international quality-of-care organizations and sources of QIs relevant to physical therapist practice are listed in Table 3. Clinicians are encouraged to evaluate the processes through which international QIs were developed and to consider their target audience, as some indicator sets were developed on the basis of evidence created only in a particular country or region22 and thus may be less applicable to other health care systems and clinical contexts.

Table 3.

Sources of Quality Indicators Relevant to Physical Therapist Musculoskeletal Practice

The AHRQ QIs use hospital inpatient administrative data and thus are less relevant to clinicians working in outpatient and community-based settings. The currently available AHRQ QI modules represent 4 aspects of health care quality: prevention, inpatient care, patient safety, and pediatric care.45 The prevention QIs can be used with hospital inpatient discharge data to identify high-quality care for “conditions for which good outpatient care can potentially prevent the need for hospitalization or for which early intervention can prevent complications or more severe disease.”45

The CMS uses quality measures in its various quality initiatives, including quality improvement, pay for reporting, and public reporting for specific health care providers.4 Jette and Jewell32 examined QIs related to primary and secondary prevention and aimed at outpatient processes of care that were eligible for (at that time) incentive payments through the CMS Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). In 2015, the CMS changed the program from a 0.5% incentive payment to a 1.5% negative payment adjustment to promote reporting of quality information and as a requirement for full compensation for professional services provided by eligible professionals. In 2012, approximately 48,300 physical therapists and occupational therapists were eligible to participate in the PQRS (Heather L. Smith, PT, MPH, Director, Quality, APTA; personal correspondence; January 13, 2015).

The NQMC is an initiative of the AHRQ and includes measures in the US Department of Health and Human Services Measure Inventory that meet NQMC criteria.46 Some QIs within this repository are relevant to physical therapist practice, yet physical therapists are rarely identified as professionals involved in the delivery of given health services. For example, in a QI endorsed by the American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons and NQMC (“percentage of patient visits for patients aged 21 and older with a diagnosis of OA with assessment for function and pain”), only advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, and physicians are listed as professionals involved in the delivery of this health service.20

The NQF was established in 1999 as a United States–based nonprofit organization that “promotes patient protections and health care quality through measurement and public reporting.”39 The NQF is under contract with the US government and has more than 400 member organizations representing “consumers, health plans, medical professionals, employers, government and other public health agencies, pharmaceutical and medical device companies, and other quality improvement organizations.”39 Quality measures developed by both public and private measure developers, including the CMS, are endorsed by the NQF if they are freely available in the public domain and meet specific criteria, including importance to measure and report, validity, and feasibility.39

Assessing the Methodological Quality of QIs

Just as there is no universally accepted approach or tool for developing QIs, there is no such approach or tool for evaluating the methodological quality of QIs.41 On the basis of the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) instrument, which is widely used to assess the quality of clinical practice guidelines,47 Abrahamyan et al48 developed a modified version (AGREE II-QI) to appraise QIs with regard to 6 domains: (1) scope and purpose, (2) stakeholder involvement, (3) rigor of development, (4) clarity of presentation, (5) applicability, and (6) editorial independence. If it is necessary to consider a number of related QIs for a given patient population or health service, physical therapists are encouraged to evaluate a given set of QIs against such criteria to determine their appropriateness for the patient population and clinical context.

Collecting and Reporting QI Data

Ideally, a QI is written with or accompanied by additional information that specifies appropriate data collection tools, a scoring process, and acceptable performance.15 The developers of the aforementioned QI endorsed by the American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons for measuring OA-related pain and function recommended using “a standardized scale or the completion of an assessment questionnaire” and suggested the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire (SF-36) as the first such standardized measure.20 Although widely used for research purposes and in administrative databases and longitudinal patient registries, this questionnaire is not a feasible tool for routine clinical practice.49 Physical therapists are encouraged to examine the details of the published QI to determine whether data can be readily collected with the recommended method or tool.

Current Developments in QI Reporting

The APTA and the CPA have both made the development of an online outcome measure database a priority for their members in 2015. Because the standardized assessment of patient outcomes is a common quality-of-care metric, these initiatives will serve as a good starting point for clinicians when reporting QIs. In the United States, APTA members and nonmembers will be able to contribute their patient outcome data to the Physical Therapy Outcomes Registry for an annual fee, with a full public launch planned for January 2016 (http://www.ptoutcomes.com). The APTA is applying for Qualified Clinical Data Registry status, which will enable eligible professionals to meet PQRS data reporting requirements through the same platform (Heather L. Smith, PT, MPH, Director, Quality, APTA; personal correspondence; January 13, 2015). In April 2015, the CPA launched an electronic outcome measure database using the Focus on Therapeutic Outcomes system (http://www.fotoinc.com) with the aim of providing real-time data on quality of care in outpatient settings (Michael Brennan, CEO, CPA; personal correspondence; January 23, 2015). Both systems will enable participating clinicians to access point-of-care data on the progress of patients, treatment effectiveness, and practice strengths and demonstrate the value of physical therapy to patients, decision makers, and payers. Furthermore, these professional organizations believe that the routine administration, reporting, viewing, and comparison of such data within and across patient types, diagnostic groups, providers, and clinics is an important starting point for physical therapists to accept the quality reporting and improvement movement (Kate Rexe, Manager, Policy and Government Relations, CPA; personal correspondence; January 22, 2015).

In the field of rheumatology, members of the American College of Rheumatology and the Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals, including physical therapists, can register to use the free Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE) to submit PQRS and other quality measure data (Melissa Francisco, Director of Registries, American College of Rheumatology; personal correspondence; November 16, 2014). As a Qualified Clinical Data Registry, the Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness meets CMS requirements for reporting QI data directly through electronic health records; therefore, providers are able to avoid the 1.5% payment adjustment starting in 2015. Like some of the other outcome measure and quality reporting registries, this system allows providers to access detailed and aggregate data at the individual patient, provider, and practice level as well as comparisons with national and, eventually, international benchmarks.

Other methods for collecting and reporting QI data can be used when electronic data are not readily available or care processes of interest are simply not recorded, as is often the case in rehabilitation practice. Although audit and feedback can be effective means of assessing the quality of care and gaps in care and reporting this information to the provider or decision maker to inform change in practice,16,36 manual chart audits can be costly and time-consuming and are subject to extractor bias and missing information.14–16,35,50 Surveys also have been used to collect QI data from practitioners23 and patients51,52; however, these methods are performed retrospectively—often, months after the episode of care—and are subject to recall bias.15 Ideally, QI data collection will be part of routine care through the standardization of clinical documentation or embedding of QIs in electronic health records14 or other digital applications and will be made available at the point of care to guide clinical decision making and inform treatment planning in real time.15

Implementing QIs in Physical Therapist Practice

Although there are numerous sources of QIs with various degrees of applicability to physical therapist practice, there are few resources and little guidance on how to apply these tools in routine clinical practice. As noted earlier, the AGREE II-QI instrument includes the domain applicability, and, within this domain, there is an item addressing whether the indicators are supported with tools for clinical use.48 These include data collection forms, manuals, and training materials.

The European Musculoskeletal Conditions Surveillance and Information Network created—as part of the development of standards for medical and rehabilitation care and QIs for OA and rheumatoid arthritis—an audit tool to help clinicians and decision makers implement quality measures.22 This tool includes initial questions regarding the applicability of QIs to a given institution (relevance) and whether data can be collected for the specific indicator (feasibility). This European consortium also developed consumer-friendly instruments that can be used by patients to assess the quality of care they have received and discuss treatment options.22 Although the clinician tool falls short of providing a means to collect and monitor QI data during an ongoing encounter with a patient, the audit and feedback process can be useful for self-reflective practice and for identifying inconsistencies or gaps in care within or across providers.

In the United States, the AHRQ offers a toolkit to help hospital staff members understand AHRQ QIs and to support them in implementing these indicators to improve quality and patient safety in hospital settings. The toolkit focuses on patient safety and inpatient QIs and provides guidance on planning, improving, and sustaining improvement strategies related to specific QIs.45 Suggestions on how physical therapists can actively participate in efforts regarding QIs and begin to implement them in practice are given in the Appendix.

Barriers to Implementing QIs

Physical therapists and other health care professionals can encounter challenges when selecting and implementing QIs in routine clinical practice. A clinical logistical concern is that many older patients will have more than one health problem, making it difficult to decide which problems and QIs to prioritize. In some cases, patients with certain comorbidities will be excluded from measurement because their conditions are not appropriate for the care process or another health condition will confound the outcomes.14,15,42 In such circumstances, more generic QIs with broad applicability, such as those pertaining to effective patient-provider communication, care coordination and transfers, minimizing fall risk, and assessing patients' experiences (satisfaction), may be more appropriate.4,39,46 However, because evidence suggested that a larger number of comorbidities was associated with better quality of care across 3 cohorts of older adults,53 multiple comorbidities do not appear to prevent the successful implementation of QIs.

Other challenges to using QIs at the point of care include time constraints, perceived burdens on clinicians and patients, limited access to appropriate QIs, lack of knowledge about and tools for applying measures, limited management support, and lack of perceived value and importance.32,54

Applying the QI Development Framework to TJA Rehabilitation

As noted earlier, a health care topic may be prioritized for QI development if it affects many patients, is associated with significant disability rates, shows variations in care and outcomes, is costly to the health care system, and provides opportunities to change practice.14,39,40 On the basis of these criteria and building on our previous research,55–58 we determined that TJA rehabilitation is an important area for the development of QIs, with tremendous room for improvement in care delivery and outcomes. In Canada, in 2012 and 2013, more than 93,000 primary total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty procedures were performed to treat changes caused by advanced OA in these joints.59 In the United States, the number of such procedures is more than 10-fold higher and is projected to surpass 4 million annually by 2030.60 With aging of the population and rising obesity rates, the prevalence of OA and TJA procedures will continue to grow,61 despite recent economic downturns.62 Physical therapy can reduce pain and improve function and quality of life in patients undergoing TJA, with current evidence emphasizing the need for rehabilitation to optimize patient outcomes before and after surgery,55,56,63,64 reduce health care costs,65 and increase patients' satisfaction.57

Despite the evidence supporting TJA rehabilitation for improved patient outcomes and the availability of best-practice recommendations,58 there are marked variations in clinical practice.66–68 Variations in other areas of health care practice, such as rates of back surgery, have been linked to excessive health care costs and outcome variability.69 Inadequate rehabilitation is likely a major contributor to the residual pain, muscle weakness, functional limitations, and poor quality of life reported in approximately 25% of patients after TJA.70–72 Quality of care also varies across surgical settings. In a retrospective review of charts for 224 patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty at 3 affiliated hospitals in the United States, the overall adherence to 31 surgical and medical process QIs was found to be 53%, with statistically significant differences in pass rates across sites.50

For patients not planning to have surgery and patients before TJA, an examination of quality of care for OA in older adults dwelling in the community in the United States revealed various levels of performance on 8 QIs, with median pass rates ranging from 67% for OA treatment to 50% for medication prescription and safety.73 In a postal survey of 1,349 adults with physician-diagnosed hip or knee OA and living in one Canadian province, the overall pass rate for 4 Arthritis Foundation OA process QIs was 22.4%; the lowest adherence (6.9%) was noted for the assessment of nonambulatory function, including self-care activities, and the highest adherence (29.2%) was noted for the assessment of ambulatory function.51 Similar care gaps for hip and knee OA treatment outside of North America were reported when patients were surveyed with the OsteoArthritis Quality Indicator questionnaire immediately after a visit to their primary care provider.52

Because of the aging population, the increased prevalence of OA, and the growing demand for high-volume procedures, TJA procedures and related rehabilitation will have an increasingly greater impact on health care systems and thus warrant the development of QIs.61,74

Developing QIs for TJA Rehabilitation

To develop QIs for TJA rehabilitation, we applied a modified version of the RAND/UCLA approach. We used high-quality evidence, including QI sets and practice guidelines for OA care, and systematic reviews; when necessary for certain rehabilitation topics, we conducted rapid reviews of the literature. The QI statements were converted to the “if-then-because” format and, together with the synthesized evidence, were provided to an 18-member expert panel of clinicians, researchers, methodologists, and patients in a Web-based survey. In the initial round, each panelist independently rated the importance and validity (scientific soundness) of 82 candidate QIs by using a 9-point Likert scale. The aggregated ratings were given to the panelists along with their own ratings of each QI. Next, the panelists were asked to participate in a moderated online discussion forum over a 2-week period and then another round of online rating. Conducting an online discussion rather than an in-person meeting is less expensive, provides participants with greater flexibility in scheduling their participation, and allows for wider geographic representations on an expert panel. Quality indicators with a median rating of greater than or equal to 7 of 9 for both importance and validity and no disagreement, as indicated by calculation of the interpercentile range adjusted for symmetry,42 were accepted in the final sets.

To collect and report TJA QI data, we converted the accepted indicators into a clinician-friendly checklist that can be used during encounters with patients. In addition, for QIs pertaining to the assessment or use of outcome measures, we specified that clinicians should use a “standardized approach” or “standardized tool,” as appropriate, to collect QI data rather than a specific tool. With further refinement of these QIs, we will identify tools and measures that are valid, reliable, responsive, and feasible in clinical rehabilitation settings to provide further guidance to clinicians.

To implement the QIs, we will use various tools and approaches, including integrating the QIs into standardized TJA patient education booklets and provincial clinical pathways and embedding them in electronic health records and clinical assessment forms. Barriers to implementing the QIs will be explored through semistructured interviews with clinicians and decision makers to determine whether barriers exist at the level of the QI tool itself, the clinician, or the organization.

Several lessons have been learned through our efforts to develop and pilot test one method of collecting QI data for TJA rehabilitation. First and foremost, early and ongoing engagement of patients, frontline clinicians, clinical leaders, decision makers, and other stakeholders is important to fully appreciating a clinical area and confronting issues for which QIs are being proposed. By understanding the clinical context, defining QIs for key stakeholders, and engaging in dialogue on the ramifications of implementing QIs, practitioners are more likely to support their use in clinical settings. We have learned that it is imperative for QIs to be formatted in a way that permits consistent interpretation and widespread application across various practice settings and that requires minimal effort on the part of clinicians. In the field of TJA rehabilitation, there are many gaps in the literature and few rehabilitation QIs on which to build. This situation necessitated a very broad, comprehensive search for all supporting evidence and identification of sources of related QIs and quality measures (Tab. 3).

Conclusion

As evidence-based practitioners who have clinical postgraduate degrees and who operate as direct-access health care professionals in most US states and all of Canada, physical therapists are ideally suited to incorporating quality-of-care initiatives into their routine practice. For physical therapists to engage in both discipline-specific and team-based QI efforts, they must understand the value and role of QIs in health care delivery and be familiar with methods used to develop or identify, collect, report, and implement QIs. Physical therapists are encouraged to contribute to the identification and implementation of QIs in their clinical settings or health care organizations to ensure that the selected measures are relevant, feasible, clinically meaningful, and within their control.

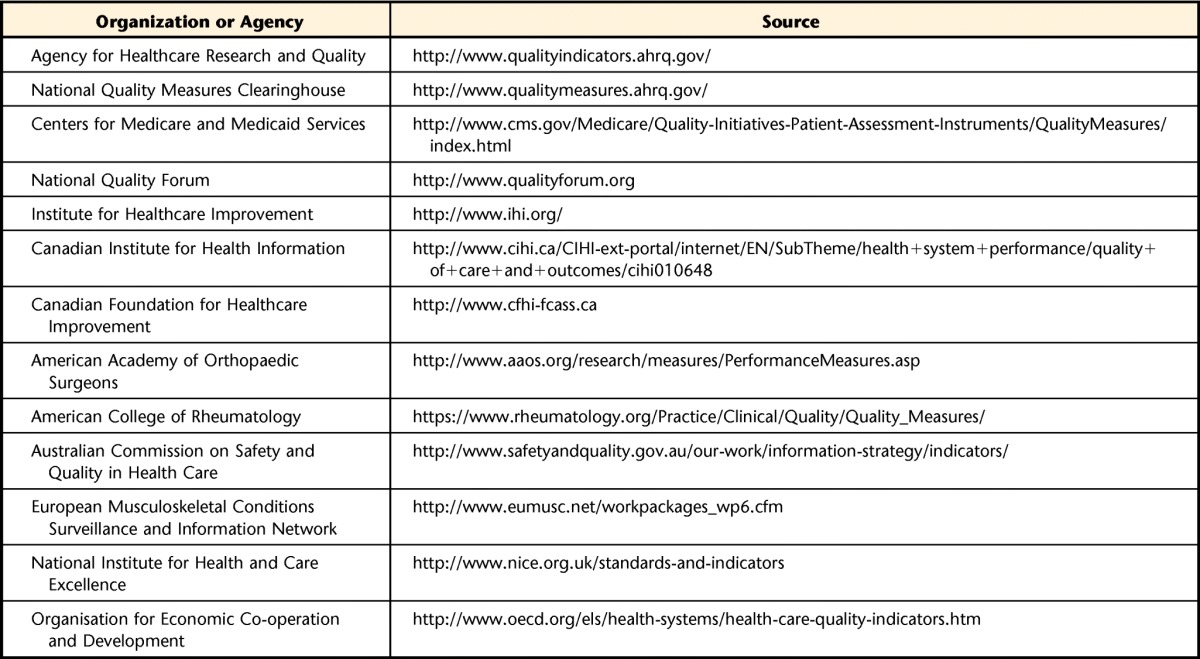

Appendix.

Appendix.

Strategies for Integrating Quality Indicators (QIs) and Quality of Care in Physical Therapist Practice

Footnotes

Dr Westby, Dr Li, and Dr Jones provided concept/idea/project design. All authors provided writing. Dr Westby provided project management. Dr Li provided facilities/equipment. Ms Klemm, Dr Li, and Dr Jones provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission). The authors thank the following people for providing valuable information regarding quality improvement and reporting initiatives for their respective professional organizations: Michael Brennan, CEO, Canadian Physiotherapy Association (CPA); Kate Rexe, Manager, Policy and Government Relations, CPA; Heather L. Smith, PT, MPH, Director, Quality, American Physical Therapy Association (APTA); Justin Moore, Executive Vice President, Public Affairs, APTA; and Melissa Francisco, Director of Registries, American College of Rheumatology.

Dr Westby was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research postdoctoral fellowship.

References

- 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2013 National Healthcare Quality Report. AHRQ Publication No 14-0005. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; May 2014. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqr13/index.html Accessed June 18, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baker GR, Denis JL, Pomey MP, Macintosh-Murray A. Effective governance for quality and patient safety in Canadian healthcare organizations: a report to the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation and the Canadian Patient Safety Institute. June 2010. Available at: http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/Migrated/PDF/ResearchReports/CommissionedResearch/11505_Baker_rpt_FINAL.pdf Accessed July 15, 2015.

- 3. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality measures. CMS.gov website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/index.html Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 5. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Quality of care and outcomes. Canadian Institute for Health Information website. Available at: http://www.cihi.ca/en/health-system-performance/quality-of-care-and-outcomes Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 6. Care Quality Commission website. Available at: http://www.cqc.org.uk/ Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 7. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care website. Available at: http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 8. European Commission. European core health indicators (ECHI). European Commission Public Health website. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health/indicators/echi/index_en.htm Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 9. Health & Social Care Information Centre. Quality and Outcomes Framework. Health & Social Care Information Centre website. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/qof Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 10. Greengarten M, Hundert M. Individual pay-for-performance in Canadian healthcare organizations. Healthc Pap. 2006;6:57–61, 72–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brennan M. Personal leadership in time of change. Physiother Pract. 2013;3:7. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mainz J. Quality measurement can improve the quality of care—when supervised by health professionals. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117:321–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stelfox HT, Straus SE. Measuring quality of care: considering measurement frameworks and needs assessment to guide quality indicator development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1320–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mainz J. Developing evidence-based clinical indicators: a state of the art methods primer. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(suppl 1):i5–i11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rubin HR, Pronovost P, Diette GB. From a process of care to a measure: the development and testing of a quality indicator. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13:489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham ID, eds. Knowledge Translation in Health Care: Moving from Evidence to Practice. 2nd ed West Sussex, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:358–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pencharz JN, MacLean CH. Measuring quality in arthritis care: the Arthritis Foundation's quality indicator set for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2004;51:538–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons/Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. Osteoarthritis Physician Performance Measurement Set. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2010. Available at: http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=28034 Accessed December 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacLean CH. Quality indicators for the management of osteoarthritis in vulnerable elders. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. European Musculoskeletal Conditions Surveillance and Information Network. Musculoskeletal conditions health care quality indicators. eumusc.net website. Available at: http://www.eumusc.net/workpackages_wp6.cfm Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 23. Peter WF, van der Wees PJ, Hendriks EJ, et al. Quality indicators for physiotherapy care in hip and knee osteoarthritis: development and clinimetric properties. Musculoskelet Care. 2013;11:193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grypdonck L, Aertgeerts B, Luyten F, et al. Development of quality indicators for an integrated approach of knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1155–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khanna D, Arnold EL, Pencharz JN, et al. Measuring process of arthritis care: the Arthritis Foundation's quality indicator set for rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:211–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American College of Rheumatology. Rheumatoid arthritis quality indicators. American College of Rheumatology website. Available at: http://www.rheumatology.org/Practice-Quality/Clinical-Support Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 27. Mikuls TR, MacLean CH, Olivieri J, et al. Quality of care indicators for gout management. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:937–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sampsel SL, MacLean CH, Pawlson LG, Hudson Scholle S. Methods to develop arthritis and osteoporosis measures: a view from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(suppl 47):22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. SooHoo NF, Lieberman JR, Farng E, et al. Development of quality of care indicators for patients undergoing total hip or total knee replacement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grube MM, Dohle C, Djouchadar D, et al. Evidence-based quality indicators for stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 2012;43:142–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nijkrake MJ, Keus SH, Ewalds H, et al. Quality indicators for physiotherapy in Parkinson's disease. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;45:239–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jette DU, Jewell DV. Use of quality indicators in physical therapist practice: an observational study. Phys Ther. 2012;92:507–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ryan AM, Doran T. The effect of improving processes of care on patient outcomes: evidence from the United Kingdom's Quality and Outcomes Framework. Med Care. 2012;50:191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rutten GM, Degen S, Hendriks EJ, et al. Adherence to clinical practice guidelines for low back pain in physical therapy: do patients benefit? Phys Ther. 2010;90:1111–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cadilhac DA, Pearce DC, Levi CR, et al. Improvements in the quality of care and health outcomes with new stroke care units following implementation of a clinician-led, health system redesign programme in New South Wales, Australia. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hinchliffe S. Implementing quality care indicators and presenting results to engage frontline staff. Nurs Times. 2009;105:12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sidorenkov G, Voorham J, de Zeeuw D, et al. Do treatment quality indicators predict cardiovascular outcomes in patients with diabetes? PLoS One. 2013;8:e78821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cadilhac DA, Amatya B, Lalor E, et al. Is there evidence that performance measurement in stroke has influenced health policy and changes to health systems? Stroke. 2012;43:3413–3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. National Quality Forum website. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 40. McGlynn EA. Choosing and evaluating clinical performance measures. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:470–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kötter T, Blozik E, Scherer M. Methods for the guideline-based development of quality indicators: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2012;7:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguila MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User's Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2001. Available at: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monograph_reports/2011/MR1269.pdf Accessed July 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bonfill X, Roqué M, Aller MB, et al. Development of quality of care indicators from systematic reviews: the case of hospital delivery. Implement Sci. 2013;8:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Saag KG, Yazdany J, Alexander C, et al. Defining quality of care in rheumatology: the American College of Rheumatology white paper on quality measurement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. AHRQ Quality Indicators. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. Available at: http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/ Accessed June 18, 2015. [PubMed]

- 46. National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. Available at: http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov Accessed June 18, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–E842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Abrahamyan L, Boom N, Donovan LR, et al. An international environmental scan of quality indicators for cardiovascular care. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. SF-36.org “Community News.” SF-36.org website. Available at: http://www.sf-36.org/ Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 50. Soohoo NF, Tang EY, Krenek L, et al. Variations in the quality of care delivered to patients undergoing total knee replacement at 3 affiliated hospitals. Orthopedics. 2011;34:356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li LC, Sayre EC, Kopec JA, et al. Quality of nonpharmacological care in the community for people with knee and hip osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2230–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Grønhaug G, Østerås N, Hagen KB. Quality of hip and knee osteoarthritis management in primary health care in a Norwegian county: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Higashi T, Wenger NS, Adams JL, et al. Relationship between number of medical conditions and quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2496–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Swinkels RA, van Peppen RP, Wittink H, et al. Current use and barriers and facilitators for implementation of standardised measures in physical therapy in the Netherlands. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Westby MD, Carr S, Kennedy D, et al. Post-acute physiotherapy after primary total hip arthroplasty: a Cochrane systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:S424–S425. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Westby MD, Kennedy D, Jones DL, et al. Post-acute physiotherapy after primary total knee arthroplasty: a Cochrane systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:S425. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Westby MD, Backman CL. Patient and health professional views on rehabilitation practices and outcomes following total hip and knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a focus group study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Westby MD, Brittain A, Backman CL. Expert consensus on best practices for post-acute rehabilitation after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a Canada and United States Delphi study. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:411–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hip and knee replacements in Canada: Canadian Joint Replacement Registry 2014 Annual Report. Available at: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/CJRR%202014%20Annual%20Report_EN-web.pdf Accessed June 18, 2015.

- 60. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, et al. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tian W, DeJong G, Brown M, et al. Looking upstream: factors shaping the demand for postacute joint replacement rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1260–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wallis JA, Taylor NF. Preoperative interventions (non-surgical and non-pharmacological) for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis awaiting joint replacement surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:1381–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gill SD, McBurney H. Does exercise reduce pain and improve physical function before hip or knee replacement surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:164–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fancott C, Jaglal S, Quan V, et al. Rehabilitation services following total joint replacement: a qualitative analysis of key processes and structures to decrease length of stay and increase surgical volumes in Ontario, Canada. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lingard EA, Berven S, Katz JN, Kinemax Outcomes Group. Management and care of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: variations across different health care settings. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Roos EM. Effectiveness and practice variation of rehabilitation after joint replacement. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:160–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Ku LJ, et al. Disparities in post–acute rehabilitation care for joint replacement. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:1020–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mulley AG. The need to confront variation in practice. BMJ. 2009;339:1007–1009. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, et al. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Meier W, Mizner RL, Marcus RL, et al. Total knee arthroplasty: muscle impairments, functional limitations, and recommended rehabilitation approaches. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:246–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bhave A, Mont M, Tennis S, et al. Functional problems and treatment solutions after total hip and knee joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(suppl 2):9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ganz DA, Chang JT, Roth CP, et al. Quality of osteoarthritis care for community-dwelling older adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hawker GA, Badley EM, Croxford R, et al. A population-based nested case-control study of the costs of hip and knee replacement surgery. Med Care. 2009;47:732–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]