Abstract

Pneumocystis species remain an important cause of life-threatening pneumonia in immunocompromised hosts, including those with AIDS. Responses of the organism to environmental cues both within the lung and elsewhere have been poorly defined. Herein, we report the identification of a cell wall biosynthesis kinase gene (CBK1) homologue in Pneumocystis carinii, isolated by differential display PCR, that is expressed optimally at physiological pH (7 to 8) as opposed to more acidic environments. Expression of Pneumocystis CBK1 was also induced by contact with lung epithelial cells and extracellular matrix. Translation of this gene revealed extensive homology to other fungal CBK1 kinases. Pneumocystis CBK1 expression was equal in the cyst and trophic life forms of the organisms. We further demonstrate that Pneumocystis CBK1 expressed in cbk1Δ Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells restored defective cell wall separation during proliferation. Consistent with this, Pneumocystis CBK1 expression also stimulated transcription of the CTS1 chitinase in cbk1Δ mutant yeast cells, an event necessary for cell wall separation. In addition, Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA supported normal mating projection formation in response to α-factor in the cbk1Δ yeast cells. Site-directed mutations of serine-303 and threonine-494, potential regulatory phosphorylation sites in Pneumocystis CBK1, abolished mating projection formation, indicating a role for these amino acid residues in CBK1 activity. These findings indicate that Pneumocystis CBK1 is an environmentally responsive gene that may function in signaling pathways necessary for cell growth and mating.

Pneumocystis jiroveci remains a serious cause of pneumonia in patients with AIDS and other conditions of impaired immunity (17, 22, 36, 43). Pneumocystis carinii, which infects rats, provides a convenient model to study this infection. The life cycle of P. carinii remains elusive but involves progression of smaller trophic forms into thick wall cyst forms, characteristic of the organisms (14, 23, 24). Recent studies indicate the P. carinii cyst wall to be comprised of β-glucans, chitins, and a mannose-rich glycoprotein complex variously termed gpA or MSG (10, 19, 30, 39, 42). Environmental signals that regulate life cycle progression and generation of the glucan-rich cyst form of P. carinii are poorly understood.

Recent studies from our laboratory document that P. carinii assembles its β-glucan cyst wall through the expression of GSC-1, a gene encoding a product homologous to Fks proteins in other ascomycetous fungi (14). GSC-1 catalyzes generation of the β-1,3-glucan core polymer of the cell wall. Furthermore, cell wall integrity in P. carinii appears to involve participation of PHR1, which encodes a protein with both glycosidase and glucosyltransferase functions which have further been implicated in β-1,3/β-1,6 cross-linking of glucans (7, 15). Expression of PHR1 in P. carinii is strongly regulated by environmental pH in a fashion parallel to control of its homologue in Candida albicans (15).

Other environmental signals have further been implicated in life cycle transitions of P. carinii. In particular, binding of P. carinii to alveolar epithelial cells and extracellular fibronectin matrices induces the expression of specific signaling kinases, including the Ste20 kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase of the organism (23). These P. carinii kinases have demonstrated activity in regulating fungal morphology and mating pathways when heterologously expressed in ste20Δ yeast cells. Additional studies further support changes in organism morphology and mating events prior to the generation of P. carinii cyst forms (13, 23, 41).

In an effort to further define the responses of P. carinii to environmental signals, particularly those elements regulating cell wall generation and morphology changes, we performed differential display PCR to isolate transcripts expressed at physiological pH (pH 7 to 8) as opposed to those expressed in more acidic environments (pH 4 to 5), as might be found external to the host lung. In this manner, we isolated CBK1 from P. carinii, a gene with extensive homology to the cell wall biosynthesis kinases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other fungi (2, 25, 31). Additional studies were undertaken to further characterize the environmental responsiveness of Pneumocystis CBK1 and to determine its potential roles in fungal cell wall morphology changes and mating pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and materials.

In these studies, P. carinii refers to P. carinii organisms originally derived from American Type Culture Collection stocks and propagated in corticosteroid-treated rats as reported previously (16), (10). Whole populations of P. carinii containing both trophic forms and cysts were purified from chronically infected rat lungs by homogenization and filtration through 10-μm filters and further fractionated into enriched populations of trophic forms (99.5% pure) and cysts (>40-fold enriched) by differential filtration through 3-μm filters, as previously described (35). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal use.

S. cerevisiae strains with the prefix YSB were derived from strain S288C. Strains with the prefix DDY were from the W303 genetic background (Table 1). Deletions of yeast CBK1 protein coding regions have been reported previously (32). For complementation studies, the yeast expression plasmid pYES2.1 TOPO (Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, Calif.) under the control of the GAL1 promoter was used either alone as a control or with the complete Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this studya

| Strain | Relevant genotype |

|---|---|

| DDY757-pYES2.1 | MATaade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 pYES2.1-URA3 |

| YSB2080-pYES2.1 | MATacbk1Δ::KanMX3 ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 pYES2.1-URA3 |

| YSB2080-PcCBK1 | MATacbk1Δ::KanMX3 ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 pYES2.1-PCCBK1-URA3 |

| YSB2080-PcCBK1V5 | MATacbk1Δ::KanMX3 ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 pYES2.1-PCCBK1V5-URA3 |

| YSB127-pYES2.1 | MATa/MATαleu2Δ98/leu2Δ98 ura3-52/ura3-52 lys2-801/lys2-801 ade2-101/ade2-101 his3-Δ200/his3-Δ200 |

| YSB209-pYES2.1 | MATa/MATαcbk1-mTn3F1/cbk1-mTn3F1α leu2Δ98/leu2Δ98 ura3-52/ura3-52 lys2-801/lys2-801 ade2-101/ade2-101 his3-Δ200/his3-Δ200 pYES2.1-URA3 |

| YSB209-PcCBK1 | MATa/MATα cbk1-mTn3F1/cbk1-mTn3F1α leu2Δ98/leu2Δ98 ura3-52/ura3-52 lys2-801/lys2-801 ade2-101/ade2-101 his3-Δ200/his3-Δ200 pYES2.1-PCCBK1-URA3 |

Strains DDY757 and DDY2080 were provided by Eric Weiss, and strains YSB127 and YSB209 were provided by Scott Bidlingmaier.

Media and growth conditions.

For testing P. carinii transcriptional response at specified pHs, P. carinii organisms (mixed populations of trophic forms and cysts) were purified by homogenization and filtration (6). Total P. carinii organisms were resuspended in Ham's F-12 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum at the specified pH for a period of 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. For selection of transformants and maintenance of plasmids in yeast cells, complete synthetic medium (Q BIOgene, Inc., Montreal, Canada) was used with the appropriate dropout components. For analyzing expression of cbk1Δ yeast cells expressing Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA, cultures were incubated overnight with 2% galactose. All yeast cultures were performed at 30°C.

Differential PCR and Northern blotting.

Differential display PCR of P. carinii mRNA obtained from organisms exposed to different pHs was conducted with the GeneFishing DEG101 system (Seegene, Inc., Del Mar, Calif.). Briefly, total RNA was isolated from P. carinii maintained at pH 6 to 8 compared to organisms maintained at pH 4 to 5 over 2 h with the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Prior experiments have shown 2 h as an optimal time point to evaluate P. carinii responses to environmental cues (13). Total RNA was treated with DNase I, and reverse transcription was performed at 42°C over 90 min. The cDNA was purified from the reaction mixture, and an aliquot (50 ng) used in differential display PCR with the following primer pairs: arbitrary ACP A1 primer, 5′GTCTACCAGGCATTCGCTTCATXXXXXGCCATCGACC-3′, and anchor ACP-T primer, 5′CTGTGAATGCTGCGACTACGATXXXXXTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′. ForPCR, an initial 3-min hot start at 94°C was followed by 50°C for 3 min, and another 3 min at 72°C, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 65°C for 40 s, 72°C for 40 s, and a final 72°C 5-min extension. Aliquots of the differential PCR were examined on a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide, and upregulated genes were identified and further sequenced according to the manufacturer's directions.

The pH-regulated expression of PCR products identified by the differential display strategy was confirmed by Northern blotting. P. carinii organisms were maintained over 2 h at various pHs, and total RNA was isolated. Equal RNA (5.0 μg) was separated through a 1.0% agarose gel in the presence of 2.2 M formaldehyde, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with the identified 650-bp amplicon labeled with [α-32P]dATP (Amersham, Inc., Piscataway, N.J.). Following hybridization, membranes were washed four times and visualized by autoradiography. To further evaluate the expression of the identified 650-bp amplicon in response to contact with lung cells and extracellular matrix, P. carinii organisms were incubated for 2 h on either uncoated plastic surfaces or surfaces coated with fibronectin or A549 lung epithelial cells, as described (13). Following contact stimulation, RNA was isolated from the organisms and subjected to Northern hybridization with the 650-bp probe.

Identification of the Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA.

Initial analysis of the 650-bp amplicon identified by differential display PCR revealed the sequence to be homologous to a family of cell wall biosynthesis kinases expressed in other fungi and to contain the entire 3′ coding region for the putative Pneumocystis CBK1. To isolate the remainder of the remaining 5′ coding portion, a 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) strategy was employed (GeneRacer kit; Invitrogen) with the known antisense primers. To verify that the gene sequence identified was truly of P. carinii origin, Southern blotting was performed with the 650-bp amplicon being hybridized to EcoRI-, HindIII-, XbaI-, or XhoI-digested P. carinii genomic DNA by published methods (13, 15).

Complementation of cell wall and morphology defects of cbk1Δ yeast cells through heterologous expression of Pneumocystis CBK1.

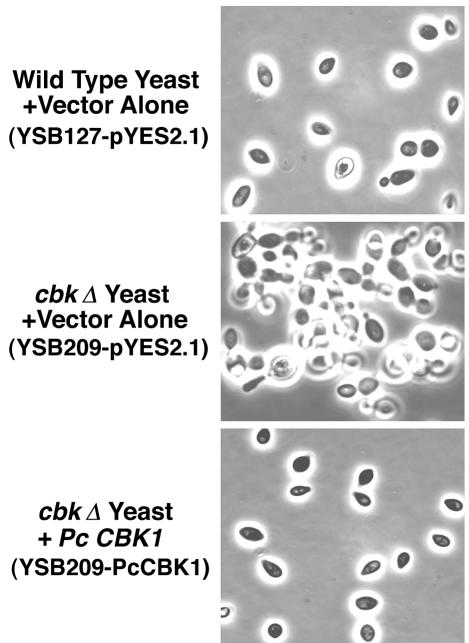

To evaluate the potential activities of P. carinii CBK1 in complementing cell wall separation and morphology defects, the cbk1Δ yeast strain YSB209 was transformed with either the pYES2.1 vector alone or the same vector containing full-length Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA. The cbk1Δ yeast strain exhibits growth in clumps due to defective cell separation during proliferation. Exponentially growing yeast cells were induced to express the transgene by culture in the presence of 2% galactose overnight and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were washed three times with 0.1 M potassium phosphate and resuspended in 1.2 M sorbitol in phosphate-buffered saline. Cells were visualized microscopically and photographed. More than 200 cells were examined for each condition.

To further analyze the formation of mating projections, which are deficient in cbk1Δ yeast cells, deficient YSB2080 yeast cells transformed with either Pneumocystis CBK1 or vector alone were further treated with α-factor pheromone (10 μM; Zymos Research, Inc., Orange, Calif.) for 6 h, fixed, and photographed. In additional studies, serine-303 and threonine-494 of Pneumocystis CBK1 were mutated to alanine (QuickChange reagent; Stratagene, Inc., La Jolla, Calif.). These phosphorylation sites have been implicated in activation of CBK family kinases in related fungi (27).

Activity of Pneumocystis CBK1 on the expression of native chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase in cbk1Δ yeast cells.

CBK family kinases have been reported to regulate the expression of chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase necessary to remodel the cell wall of proliferating fungi. Accordingly, cbk1Δ yeast cells transformed with either Pneumocystis CBK1 or vector alone were grown overnight with 2% galactose. Total RNA was isolated and separated through a 2.2 M formaldehyde gel as above. The membrane was probed with a 340-bp S. cerevisiae CTS1 probe, recognizing the native yeast chitinase. Similarly, the yeast mRNA was also analyzed with both a 512-bp S. cerevisiae probe for ENG1 and a 426-bp probe for SCW11, which recognize two unique β-1,3-glucanases in S. cerevisiae.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete cDNA sequences for P. carinii CBK1 have been deposited in GenBank (accession no. AY422071).

RESULTS

Isolation of Pneumocystis CBK1, a gene differentially expressed in response to pH and contact with lung epithelial cells.

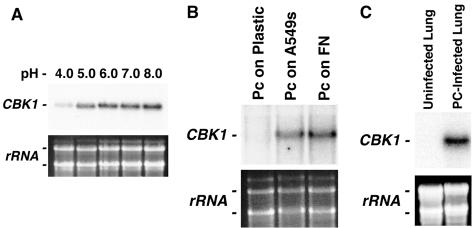

A modified differential display PCR strategy was used to identify a partial cDNA that was maximally expressed at physiological pH levels (7 to 8) in comparison to more acidic pH conditions (4 to 5). The isolated 650-bp amplicon displayed considerable homology to cell wall biosynthesis kinase (CBK) genes in other fungi (2, 25). This partial cDNA of Pneumocystis CBK1 was used as a probe to hybridize to total P. carinii RNA isolated from organisms treated under various pH conditions (Fig. 1A). Northern hybridization reconfirmed this differential expression pattern, with optimal Pneumocystis CBK1 expression observed at pH 6 through 8. Our prior work had previously revealed similar regulation of P. carinii PHR1 expression, a gene also implicated in cell wall integrity at physiological pH (15).

FIG. 1.

Pneumocystis CBK1 is an environmentally responsive gene. (A) Pneumocystis CBK1 is differentially expressed in response to pH. Total Pneumocystis life forms were isolated and resuspended in Ham's F-12 medium with 10% fetal calf serum at pH 4.0 to 8.0 at 37°C over 2 h. Transcript levels were detected by Northern hybridization with the 650-bp Pneumocystis CBK1 amplicon originally identified by differential display PCR. The top panel shows hybridization of P. carinii CBK1 to the nylon membrane. The bottom panel is a photograph of the two Pneumocystis major ribosomal subunits, demonstrating equal RNA loading. (B) A549 lung cells and fibronectin induce Pneumocystis CBK1 expression in the organism. P. carinii cells were cultured on either A549 cells or tissue culture inserts coated with fibronectin, or on uncoated plastic inserts (control). Total RNA was isolated and examined for Pneumocystis CBK1 expression. A549 cells and fibronectin-coated surfaces induced expression of CBK1. In contrast, uncoated plastic surfaces failed to induce expression of this gene. (C) Pneumocystis CBK1 is expressed in infected rat lung. Northern hybridization was performed, comparing total RNA prepared from freshly isolated Pneumocystis-infected and normal rat lung (20 μg each), probed with the Pneumocystis CBK1 probe. As anticipated, abundant Pneumocystis CBK1 expression was observed in RNA freshly obtained from the Pneumocystis-infected lung, compared to no detectable expression in uninfected rat lung.

Recent studies have indicated that P. carinii interactions with lung epithelial cells and extracellular fibronectin matrices serve as important stimuli for expression of signaling pathways and proliferation of the organism (13, 23). To address whether Pneumocystis CBK1 expression was also induced by these stimuli, P. carinii cells were cultured for 2 h on A549 lung epithelial cells or fibronectin. Total RNA was isolated and examined for CBK1 (Fig. 1B). Both A549 lung epithelial cells and fibronectin-coated surfaces strongly induced expression of Pneumocystis CBK1. In contrast, uncoated plastic surfaces failed to induce transcription of this gene.

Additional studies were undertaken to demonstrate that Pneumocystis CBK1 was actually expressed at detectable, steady-state levels during infection. To accomplish this, a Northern blot was performed comparing total RNA prepared from freshly isolated P. carinii-infected lung and normal rat lung (20 μg each), probed with the Pneumocystis CBK1 probe (Fig. 1C). As anticipated, abundant CBK1 expression was observed in RNA freshly obtained from P. carinii-infected lung compared to no detectable expression in uninfected rat lung. Together, these results indicate that Pneumocystis CBK1 is an environmentally responsive gene, actively expressed during infection with regulation by conditions of pH and host cell contact.

Characterization of Pneumocystis CBK1, a unique serine/threonine kinase gene.

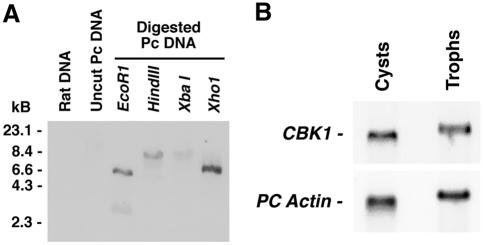

To isolate the remaining 5′ gene portion of the differentially expressed Pneumocystis CBK1 gene, RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends was performed. Amplification from Pneumocystis 5′ dephosphorylated and decapped mRNA-generated cDNA yielded a PCR product of 1,750 bp which contained the remaining 5′ portion of Pneumocystis CBK1 as well as a region of 5′ untranslated sequence. To verify that Pneumocystis CBK1 was specifically represented within the organism's genome and not an amplified host cell contaminant, the original 650-bp Pneumocystis CBK1 probe was hybridized to digested P. carinii genomic DNA, demonstrating strong localization to a single band following the representative restriction digests (Fig. 2A). The 650-bp Pneumocystis CBK1 probe failed to hybridize to host rat lung cell DNA, indicating that the amplification product was specifically represented within the P. carinii genome. Complete cDNA sequences for P. carinii CBK1 have been deposited in GenBank (accession no. AY422071).

FIG. 2.

Basal expression of CBK1 by P. carinii. (A) The 650-bp Pneumocystis CBK1 gene fragment specifically hybridizes to P. carinii genomic DNA. P. carinii was freshly isolated, and genomic DNA was isolated and digested with the indicated restriction endonucleases. The digestion products were separated by electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose. The 650-bp CBK1 amplicon specifically hybridized to Pneumocystis genomic DNA but failed to hybridize to rat genomic DNA. These results indicate that Pneumocystis CBK1 is specifically represented within the Pneumocystis genome and is not the result of amplification of contaminating rat sequences. (B) Pneumocystis CBK1 is equally expressed in cystic and trophic life forms of the organism. To examine whether CBK1 expression is differentially regulated over the life cycle of P. carinii, organisms were separated into cystic and trophic populations and total RNA was isolated. The top panel shows hybridization of the Pneumocystis CBK1 probe, while the bottom panel shows repeat hybridization of the membrane with Pneumocystis actin to confirm equal loading. Pneumocystis CBK1 mRNA appears to be expressed equally in both life forms of the organism.

Past observations from our laboraotry have indicated that the P. carinii GSC-1 transcript, which encodes a β-1,3-glucan synthetase mediating cell wall generation, is largely restricted to the cystic form of the organism (14). Having observed this difference in mRNA expression, we next investigated whether Pneumocystis CBK1 gene expression was also differentially regulated over the organism's life cycle. Cystic and trophic forms were separated, and Pneumocystis CBK1 mRNA expression was evaluated by Northern hybridization (Fig. 2B). Strikingly different from Pneumocystis GSC-1 expression, CBK1 mRNA appears to be equally expressed in both life forms of P. carinii under basal conditions. The slight differences observed in overall migration of RNA isolated from separated trophic forms versus cyst forms is likely related to differences in salt concentration in the nucleic acid isolates. However, the net relative migration of the CBK1-reactive bands observed in trophic forms and cysts was identical compared to the actin control bands, as demonstrated in the lower panel of Fig. 2B. Moreover, the level of expression of Pneumocystis CBK1 was quite similar in comparing trophic forms and cysts.

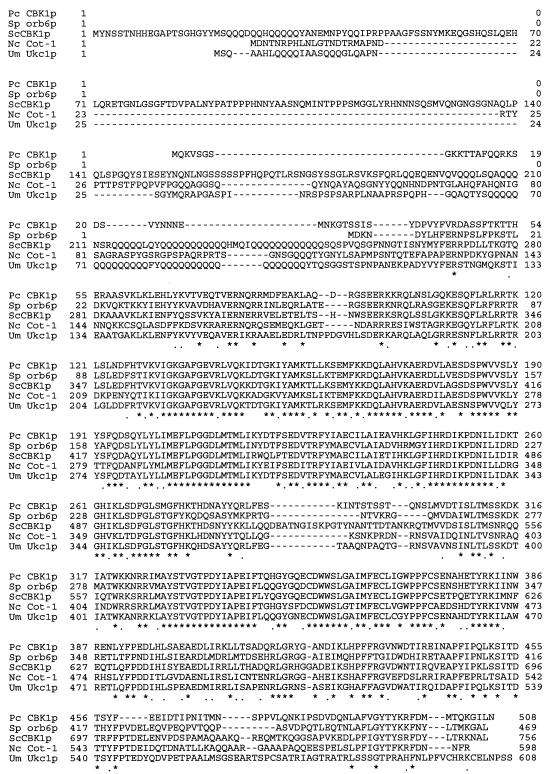

Translation of the complete Pneumocystis CBK1 open reading frame yielded a predicted full-length peptide with sequence homology to the Schizosaccharomyces pombe orb6 product (67% identity by BlastX analysis) followed by S. cerevisiae CBK1 (64% identity). The predicted Pneumocystis CBK1 protein has an estimated mass of 58.6 kDa and pI of 8.74. Protein sequence alignments of Pneumocystis CBK1 with other CBK1 fungal homologues are shown in Fig. 3. Sequence analysis of the translated Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA revealed similarities with other CBK1-related fungal kinases. Between translated amino acids 125 and 431, a serine/threonine protein kinase catalytic domain was detected (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md.). The activity of CBK protein kinases is usually controlled by specific residues in this domain (11). At amino acids 109 to 126, Pneumocystis CBK1 possesses a CaM/S100 binding site similar to that of other fungal CBK1 kinases (2). In the CBK1-related mammalian kinase Ndr, this region is responsible for Ca2+-dependent binding and activation of Ndr by the Ca2+ receptor S100 (26). Finally, the Pneumocystis CBK1 translated protein contains both the serine (position 303) and threonine (position 494) phosphorylation sites of the CBK1-related kinases, which are required for activation. Abolishing these two activation sites in the human Ndr protein eliminates the ability of the kinase to phosphorylate target proteins (28).

FIG. 3.

Pneumocystis CBK1 is homologous to other fungal CBK1 and CBK1-like proteins involved in cell wall morphogenesis and remodeling. Multiple-sequence alignment of the CBK-related kinases was performed with ClustalW (MacVector 6.0). *, similar amino acids;., similarly charged amino acids. Pc, P. carinii; Sp, S. pombe; Sc, S. cerevisiae; Nc, Neurospora crassa; Um, Ustilago maydis.

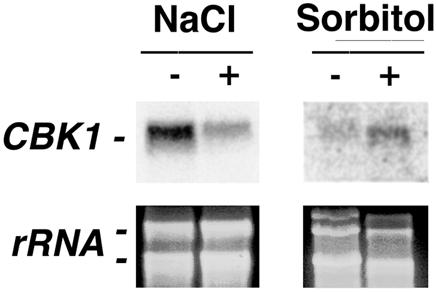

Pneumocystis CBK1 expression in response to osmolarity and ionic stress.

Cell wall integrity and signaling pathways may also be modulated in response to other environmental factors, including osmolarity and ionic stresses. P. carinii placed in medium containing 1.2 M sorbitol, an environmental condition shown to stimulate the high-osmolarity growth pathway (12), resulted in markedly increased Pneumocystis CBK1 transcript levels compared to growth in basal medium without sorbitol (Fig. 4). However, P. carinii exposed to high ionic concentrations (0.8 M NaCl) revealed decreased CBK1 expression (Fig. 4). These findings add further support to our contention that Pneumocystis CBK1 responds differentially to environmental cell wall stresses under specific conditions.

FIG. 4.

Expression of Pneumocystis CBK1 is differentially regulated by osmolarity and ionic stress. Total Pneumocystis forms were placed in Ham's F-12 medium with 10% fetal calf serum in the presence or absence of 0.8 M NaCl or 1.2 M sorbitol over 2 h. Northern analysis was used to determine Pneumocystis CBK1 expression. The bottom panel demonstrates major Pneumocystis ribosomal subunits to confirm equal loading of RNA.

P. carinii CBK1 can restore normal morphology and cell wall separation defects in cbk1Δ (deficient) yeast cells.

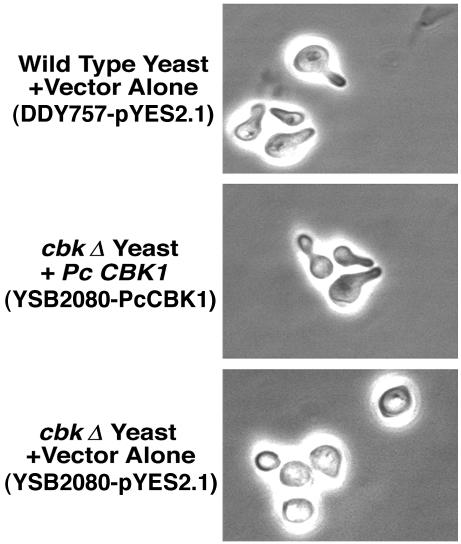

Studies were next performed to determine the potential functions of Pneumocystis CBK1 in promoting normal morphology and cell wall separation during growth. Due to the inability to culture and transform P. carinii, conventional methods used to study gene function in this organism are not currently possible. However, recent investigations have used heterologous expression and complementation of genetic knockouts in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe to analyze the potential function of P. carinii genes (9, 15, 16, 29). With this technique, the biological activity of Pneumocystis CBK1 was assessed for its ability to complement S. cerevisiae cbk1Δ cells. Taking advantage of the cbk1Δ strain's inability to grow on uracil, Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA was subcloned into the yeast expression vector pYES2.1 TOPO. Yeast cbk1Δ cells were transformed with this construct and isolated. In liquid culture, yeast cbk1Δ cells grow as large aggregates of cells, due to defective cell separation (2, 31). However, ckb1Δ yeast cells expressing Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA were restored to the normal phenotype indistinguishable from wild-type control yeast cells containing vector alone compared to cbk1Δ yeast cells transformed with vector alone (Fig. 5). Thus, the majority of cbk1Δ cells expressing Pneumocystis CBK1 were observed as individual cells rather than as clumps. Therefore, Pneumocystis CBK1 can function in promoting normal cell wall separation following heterologous expression in cbk1Δ yeast cells.

FIG. 5.

Restoration of the cell wall separation defect in proliferating cbk1Δ yeast cells by Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA. Wild-type yeast cells with the vector control (YSB127-pYES2.1), cbk1Δ-deficient mutant yeast cells with the vector control (YSB209-pYES2.1), and cbk1Δ yeast cells expressing Pneumocystis CBK1 (YSB209-PcCBK1) were grown overnight to the early logarithmic phase in minimal medium without uracil but containing 2% glucose. The following day, the cells were induced to express the transgene by incubation in minimal medium containing 2% galactose until mid-logarithmic growth was reached. The yeast cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and photographed. The cbk1Δ (deficient) mutant yeast cells grew in clumps, demonstrating defective cell wall separation. In contrast, wild-type yeast cells grew as a separated cell suspension. Pneumocystis CBK1 restored the separated cell suspension phenotype in the cbk1Δ (deficient) yeast.

Pneumocystis CBK1 can restore chitinase but not β-1,3-glucanase expression in cbk1Δ yeast cells.

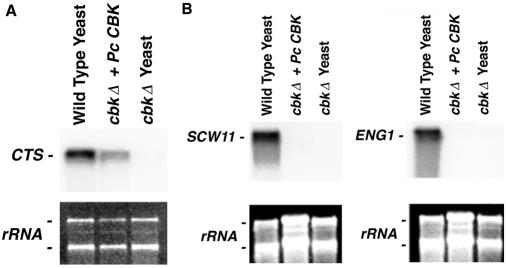

Previous studies have shown that yeast cells deficient in CBK proteins are unable to separate from the parent cell due to impaired expression of CTS1 chitinase (2, 31). Indeed, yeast cells deficient in CBK1 protein exhibit a 12-fold decrease in the CTS1 transcript (2). Therefore, to further determine whether complementation of normal yeast cell wall separation by Pneumocystis CBK1 was associated with restoration of CTS1 expression, we evaluated CTS1 mRNA levels in cbk1Δ cells transformed with Pneumocystis CBK1 compared to vector alone (Fig. 6A). Consistent with the morphological observations of cell separation, Pneumocystis CBK1 induced upregulated CTS1 chitinase expression required for cell wall remodeling and separation, though not to levels observed in wild-type yeast cells.

FIG. 6.

Pneumocystis CBK1 induces expression of yeast chitinase but not β-1,3-glucanase mRNA in cbk1Δ cells. (A) Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA enhances expression of the yeast chitinase CTS1 mRNA levels in cbk1Δ yeast cells. Northern blot analysis of yeast CTS1 mRNA levels in wild-type control yeast cells (YSB127-pYES2.1), cbk1Δ cells with Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA (YS209-PcCBK1), and cbk1Δ cells (YSB209-pYES2.1). All strains were grown overnight in minimal medium without uracil and 2% galactose until the mid-logarithmic phase was reached. Pneumocystis CBK1 increased the expression of yeast CTS1 chitinase, though not to the level observed in wild-type yeast cells. The bottom photograph shows the S. cerevisiae major ribosomal subunits to indicate relative loading. (B) Pneumocystis CBK1 expression does not affect expression of yeast β-1,3-glucanases encoded by SCW11 and ENG1 in cbk1Δ yeast cells. Northern analysis of SCW11 (left panel) and ENG1 (right panel) mRNA levels is shown. In contrast to expression of chitinase, Pneumocystis CBK1 did not alter the expression of either yeast cell wall β-1,3-glucanase.

Having observed that Pneumocystis CBK1 expression in yeast cells restored CTS1 expression necessary for chitin degradation, we further examined the possibility of whether Pneumocystis CBK1 expression in cbk1Δ cells might also alter the expression of the yeast β-1,3-glucanases encoded by ENG1 and SCW11. In previously published studies of wild-type S. cerevisiae cells, ENG1 (open reading frame YNR067C) and SCW11 were shown to be expressed 2.4- and 4.8-fold higher than in cbk1Δ yeast cells (2). SCW11 is believed to participate in yeast cell separation (4, 17). Recently, ENG1 mutants have also been shown to be defective in cell separation (1). Interestingly, however, in our studies, neither SCW11 nor ENG1 transcription was significantly altered in cbk1Δ yeast cells expressing Pneumocystis CBK1 (Fig. 6B). Thus, Pneumocystis CBK1 can regulate chitinase expression but not the expression of β-1,3-glucanases when heterologously expressed in ckb1Δ-deficient yeast cells.

Pneumocystis CBK1 expression in cbk1Δ yeast cells can support the formation of pheromone-driven mating projections.

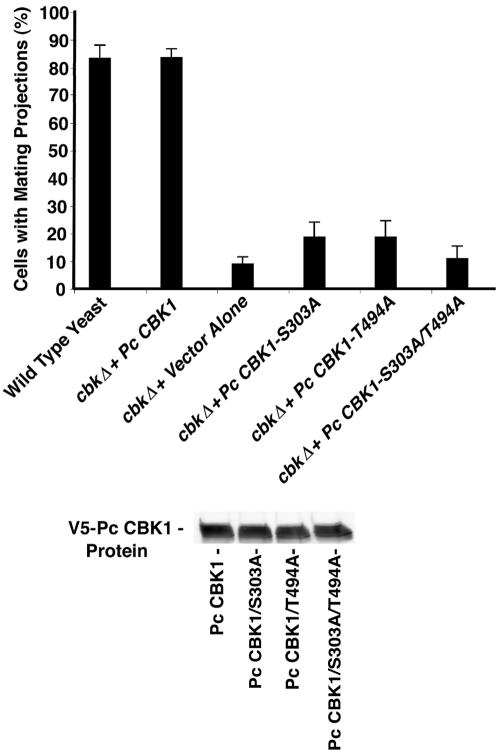

It has been described that yeast cells lacking functional CBK proteins are unable to maintain normal mating projections in response to α-factor pheromone. The cbk1Δ yeast cells form small bumps on their surface that are unable to develop into the longer normal protrusions that participate in mating (2). To further determine whether Pneumocystis CBK1 could restore normal mating projection formation, cbk1Δ yeast cells expressing Pneumocystis CBK1 were grown overnight and subjected to 10 μM α-factor for 6 h. Similar to wild-type controls, Pneumocystis CBK1 expression in cbk1Δ yeast cells restored the development of longer mating projections, consistent with normal polarized growth (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Pneumocystis CBK1 expression in cbk1Δ yeast cells can restore normal pheromone-induced mating projection formation. Exponentially growing yeast cells induced to express the transgene by overnight incubation with 2% galactose were then treated with the α-factor pheromone (10 μM) for 6 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and photographed. The cbkΔ yeast cells with vector alone were unable to form normal mating projections in the presence of α-factor. However, Pneumocystis CBK1 supported the formation of normal mating projections similar to those in wild-type yeast cells.

Next, Pneumocystis CBK1 mutants in which either serine-303 or threonine-494 was replaced with alanine were created. These phosphorylation sites have been found to be necessary to maintain activity in other CBK proteins (28). Mating projection of each of these alanine mutants was measured following yeast cell treatment with α-factor for 6 h. An epitope-tagged Pneumocystis CBK1 construct (YSB2080-PCCBK1V5) expressed in cbk1Δ yeast cells was as able to generate mating projection formation as the parental wild-type S. cerevisiae strain transformed with the vector alone (Fig. 8). However, both the alanine-303 and alanine-494 mutants exhibited greatly reduced mating projection formation (75 to 80% reduction). Furthermore, combined mutations of both the serine-303 and threonine-494 sites reduced mating projection formation by approximately 90%. Western analysis confirmed that the various mutant proteins were expressed equally (Fig. 8). These results indicate that Pneumocystis CBK1 requires serine-303 and threonine-494 for normal activity following heterologous expression in cbk1Δ-deficient yeast cells.

FIG. 8.

Pneumocystis CBK1 residues serine-303 and threonine-494 are required for mating projection formation following heterologous expression in cbk1Δ yeast cells. Mutant cbk1Δ cells expressing either wild-type V5-tagged Pneumocystis CBK1 or the indicated mutants were treated for 6 h with α-factor (10 μM). A total of 100 cells were counted, and the data are the means ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments. In the lower panel, protein extracts (40 μg) were analyzed by immunoblotting with the V5 antibody to verify similar expression levels of each Pneumocystis CBK1 construct.

DISCUSSION

P. carinii is a preferential intra-alveolar opportunistic pathogen. Productive ongoing replication of this organism outside of the lung has not been conclusively demonstrated (21, 33), yet the environmental signals that the organism receives within the alveolar spaces and elsewhere remain poorly defined. In that light, we have undertaken a series of investigations to define P. carinii responses to the lung environment. In the current study, we used a modified differential display PCR strategy to isolate mRNA transcripts that were preferentially upregulated upon P. carinii exposure to physiological pH. With this approach, we isolated a 1.5-kb cDNA with considerable homology to the cell wall biosynthesis kinases of other fungi, including S. cerevisiae CBK1 and S. pombe orb6. These data demonstrate for the first time that a fungal CBK1-related kinase responds to environmental pH, being maximally expressed at physiological pH (7 to 8). The Pneumocystis CBK1 gene also exhibits enhanced expression following contact of the organisms with alveolar epithelial cells and extracellular fibronectin matrix, potent stimuli for organism proliferation and life cycle progression (13, 20, 23). P. carinii expression of CBK1 was also differentially regulated by various osmotic stresses. Taken together, these observations indicate that Pneumocystis CBK1 is an environmentally responsive gene expressed in response to various external stimuli.

We have previously observed another mRNA transcript in P. carinii that is upregulated in this pH range, PHR1 (15). Pneumocystis PHR1 expression is needed for optimal cell wall integrity, likely through glucan cross-linking, and was also maximally expressed at physiological pH present within the lung (15). In addition, our previous genetic screens designed to identify genes maximally expressed after interactions of P. carinii with lung epithelial cells and extracellular matrix proteins (fibronectin, vitronectin, and collagens) demonstrated enhanced expression of P. carinii STE20 following these stimuli (13). P. carinii STE20 exhibits activities in mating and growth signaling as well as in pathways mediating morphology changes in fungi (13).

Cell wall biosynthesis kinases exert multiple regulatory functions in other fungi. Specifically, S. cerevisiae CBK1 is involved in pathways necessary for polarized cell growth, cell separation, and normal mating projection formation (2, 31). Given the vital role of other fungal CBK1-related proteins in mediating cell growth and separation, it is intriguing to postulate that Pneumocystis CBK1 may further participate in proliferation of this organism within the lung. Interestingly, our investigations demonstrate that the Pneumocystis CBK1 transcript is expressed equally by the cystic and trophic life forms of the organism. In contrast, Pneumocystis GSC-1, encoding a β-1,3-glucan synthetase, is expressed to a substantially greater degree in the cyst form of the organism (14). Therefore, P. carinii exhibits the ability to differentially control various cell wall-regulatory transcripts over the course of its life cycle and in response to various environmental stimuli.

Fungal morphology changes and associated cell wall remodeling are not only of importance for life cycle transitions but may also impact pathogenicity. For instance, Candida albicans can alternate between yeast and hyphal forms depending upon the environmental pH that the organism encounters. Recently, it was observed that a conserved serine/threonine kinase encoded by the C. albicans CBK1 gene regulates transcription of the pH-dependent gene PHR2, encoding a putative β-1,3-glycosidase thought to be involved in β-1,3/β-1,6 cross-linking (7). PHR2 is maximally expressed at pH 4.0 and is required for pathogenesis in a mouse model of vaginal infection (5). Disruption of CBK1 leads to increased levels of PHR2 transcripts at pH 7.0, a pH condition normally causing repression of PHR2, thus supporting a role for CBK1 in the cell wall remodeling required for virulence (25). The role of CBK1 in the pathogenesis of P. carinii pneumonia is not yet defined.

Currently, an efficient culture and transformation system to study gene function in P. carinii is not available. To circumvent this, we examined potential functions of Pneumocystis CBK1 in a heterologous fungal expression system, with cbk1Δ (deficient) S. cerevisiae cells. This approach demonstrated that Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA restores the cell wall separation defect seen in cbk1Δ yeast cells. In addition, we observed that CTS1, a gene encoding a yeast chitinase needed to break down the chitin component of the yeast cell wall, was also increased following expression of Pneumocystis CBK1. Although we were unable to achieve quite the mRNA transcript levels of wild-type cells (Fig. 6A), Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA expression in cbk1Δ cells yielded enough chitinase activity to provide a cell wall separation phenotype very similar to that of wild-type control yeast cells (Fig. 5).

Although Pneumocystis CBK1 could restore CTS1 transcription in cbk1Δ yeast cells, the protein was unable to alter expression of the β-1,3-glucanases ENG1 and SCW11. These two genes have been shown previously to be upregulated in CBK1 wild-type cells and are thought to participate in cell wall glucan degradation prior to the cell separation event (1, 2). While a definitive explanation is not yet available, it is plausible that the organism compensates for the lack of glucanases by the upregulation of other components in the cell wall. In addition, our data may also provide initial evidence for distinct domains on CBK1 family members that differently regulate chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase activity. Further studies will be needed to identify the specific CBK kinase sequence(s) that modulates particular cell wall active proteins.

In response to α-factor, cbk1Δ yeast cells containing Pneumocystis CBK1 cDNA were also able to form normal mating projections similar to those of wild-type control yeast cells. Mutations of serine-303 and threonine-494 resulted in a dramatic decrease in the number of mating projections and therefore appear to be critical for Pneumocystis CBK1 activity. These data further suggest that Pneumocystis CBK1 can support pheromone-induced polarization and mating events. Recent identification of P. carinii pheromone receptors and the presence of a possible mitogen-activated protein kinase mating pathway in this organism further support the likelihood of sexual reproduction in this species (34, 37, 38).

To date, CBK1 regulation in S. cerevisiae cells and related fungi has focused on the function of this protein in cell morphogenesis and events leading to cell separation (2, 31, 40). Our analysis suggests that, in P. carinii, CBK1 can be regulated through environmental cues that may further affect the ability of the organism to mate and proliferate. We anticipate that further studies of the Pneumocystis CBK1 homologue will provide new insights into the life cycle, cell wall remodeling events, and mating pathways of this important opportunistic fungus.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by NIH grants R01 HL55934 and R01 HL62150 to A.H.L.

We thank Charles Thomas, Jr., and Crystal Icenhour for many helpful discussions. We acknowledge the efforts of Zvezdana Vuk-Pavlovic and Joseph Standing in the generation of the P. carinii organisms used in these studies. We also thank Kathy Streich for considerable assistance during the final preparation of the manuscript.

Editor: T. R. Kozel

REFERENCES

- 1.Baladron, V., S. Ufano, E. Duenas, A. B. Martin-Cuadrado, F. del Rey, and C. R. Vazquez de Aldana. 2002. Eng1p, an endo-1,3-beta-glucanase localized at the daughter side of the septum, is involved in cell separation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 1:774-786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bidlingmaier, S., E. L. Weiss, C. Seidel, D. G. Drubin, and M. Snyder. 2001. The Cbk1p pathway is important for polarized cell growth and cell separation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2449-2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell, W. G. 1972. Ultrastructure of Pneumocystis in human lung. Arch. Pathol. 93:312-330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappellaro, C., V. Mrsa, and W. Tanner. 1998. New potential cell wall glucanases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their involvement in mating. J. Bacteriol. 180:5030-5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Bernardis, F., F. A. Muhlschlegel, A. Cassone, and W. A. Fonzi. 1998. The pH of the host niche controls gene expression in and virulence of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 66:3317-3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durkin, M. M., M. M. Shaw, M. S. Bartlett, and J. W. Smith. 1991. Culture and filtration methods for obtaining Pneumocystis carinii trophozoites and cysts. J. Protozool. 38:210S-212S. [PubMed]

- 7.Fonzi, W. A. 1999. PHR1 and PHR2 of Candida albicans encode putative glycosidases required for proper cross-linking of beta-1,3- and beta-1,6-glucans. J. Bacteriol. 181:7070-7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox, D., and A. G. Smulian. 1999. Mitogen-activated protein kinase Mkp1 of Pneumocystis carinii complements the slt2Delta defect in the cell integrity pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 34:451-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gustafson, M. P., C. F. Thomas, Jr., F. Rusnak, A. H. Limper, and E. B. Leof. 2001. Differential regulation of growth and checkpoint control mediated by a Cdc25 mitotic phosphatase from Pneumocystis carinii. J. Biol. Chem. 276:835-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn, P. Y., S. E. Evans, T. J. Kottom, J. E. Standing, R. E. Pagano, and A. H. Limper. 2003. Pneumocystis carinii cell wall beta-glucan induces release of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 from alveolar epithelial cells via a lactosylceramide-mediated mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 278:2043-2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanks, S. K., and T. Hunter. 1995. Protein kinases 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 9:576-596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohmann, S. 2002. Osmotic stress signaling and osmoadaptation in yeasts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:300-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kottom, T. J., J. R. Kohler, C. F. Thomas, Jr., G. R. Fink, and A. H. Limper. 2003. Lung epithelial cells and extracellular matrix components induce expression of Pneumocystis carinii STE20, a gene complementing the mating and pseudohyphal growth defects of STE20 mutant yeast. Infect. Immun. 71:6463-6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kottom, T. J., and A. H. Limper. 2000. Cell wall assembly by Pneumocystis carinii. Evidence for a unique gsc-1 subunit mediating beta-1,3-glucan deposition. J. Biol. Chem. 275:40628-40634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kottom, T. J., C. F. Thomas, Jr., and A. H. Limper. 2001. Characterization of Pneumocystis carinii PHR1, a pH-regulated gene important for cell wall integrity. J. Bacteriol. 183:6740-6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kottom, T. J., C. F. Thomas, Jr., K. K. Mubarak, E. B. Leof, and A. H. Limper. 2000. Pneumocystis carinii uses a functional cdc13 B-type cyclin complex during its life cycle. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 22:722-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovacs, J. A., V. J. Gill, S. Meshnick, and H. Master. 2001. New insights into transmission, diagnosis, and drug treatment of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 286:2450-2460. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kuranda, M. J., and P. W. Robbins. 1987. Cloning and heterologous expression of glycosidase genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:2585-2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebron, F., R. Vassallo, V. Puri, and A. H. Limper. 2003. Pneumocystis carinii cell wall beta-glucans initiate macrophage inflammatory responses through NF-kappaB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:25001-25008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limper, A. H., M. Edens, R. A. Anders, and E. B. Leof. 1998. Pneumocystis carinii inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase activity in lung epithelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 101:1148-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Limper, A. H., and S. Merali. 2003. Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Opportunistic Protists. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 50(Suppl.):602-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limper, A. H., K. P. Offord, T. F. Smith, and W. J. Martin, 2nd. 1989. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Differences in lung parasite number and inflammation in patients with and without AIDS. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 140:1204-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Limper, A. H., C. F. Thomas, Jr., R. A. Anders, and E. B. Leof. 1997. Interactions of parasite and host epithelial cell cycle regulation during Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 130:132-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long, E. G., J. S. Smith, and J. L. Meier. 1986. Attachment of Pneumocystis carinii to rat pneumocytes. Lab. Investig. 54:609-615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNemar, M. D., and W. A. Fonzi. 2002. Conserved serine/threonine kinase encoded by CBK1 regulates expression of several hypha-associated transcripts and genes encoding cell wall proteins in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 184:2058-2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Millward, T., P. Cron, and B. A. Hemmings. 1995. Molecular cloning and characterization of a conserved nuclear serine(threonine) protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5022-5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millward, T. A., C. W. Heizmann, B. W. Schafer, and B. A. Hemmings. 1998. Calcium regulation of Ndr protein kinase mediated by S100 calcium-binding proteins. EMBO J. 17:5913-5922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Millward, T. A., D. Hess, and B. A. Hemmings. 1999. Ndr protein kinase is regulated by phosphorylation on two conserved sequence motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33847-33850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morales, I. J., P. K. Vohra, V. Puri, T. J. Kottom, A. H. Limper, and C. F. Thomas. 2003. Characterization of a lanosterol 14{alpha}-demethylase from Pneumocystis carinii. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 29:232-238. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.O'Riordan, D. M., J. E. Standing, and A. H. Limper. 1995. Pneumocystis carinii glycoprotein A binds macrophage mannose receptors. Infect Immun. 63:779-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Racki, W. J., A. M. Becam, F. Nasr, and C. J. Herbert. 2000. Cbk1p, a protein similar to the human myotonic dystrophy kinase, is essential for normal morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 19:4524-4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross-Macdonald, P., A. Sheehan, G. S. Roeder, and M. Snyder. 1997. A multipurpose transposon system for analyzing protein production, localization, and function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:190-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sloand, E., B. Laughon, M. Armstrong, M. S. Bartlett, W. Blumenfeld, M. Cushion, A. Kalica, J. A. Kovacs, W. Martin, E. Pitt, et al. 1993. The challenge of Pneumocystis carinii culture. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 40:188-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smulian, A. G., T. Sesterhenn, R. Tanaka, and M. T. Cushion. 2001. The ste3 pheromone receptor gene of Pneumocystis carinii is surrounded by a cluster of signal transduction genes. Genetics 157:991-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas, C. F., R. A. Anders, M. P. Gustafson, E. B. Leof, and A. H. Limper. 1998. Pneumocystis carinii contains a functional cell-division-cycle Cdc2 homologue. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 18:297-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas, C. F., Jr., and A. H. Limper. 1998. Pneumocystis pneumonia: clinical presentation and diagnosis in patients with and without acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Semin. Respir. Infect. 13:289-295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas, C. F., J. G. Park, A. H. Limper, and V. Puri. 2001. Analysis of a pheromone receptor and MAP kinase suggest a sexual replicative cycle in Pneumocystis carinii. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 50(Suppl.):141S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Thomas, C. F. J., T. J. Kottom, E. B. Leof, and A. H. Limper. 1998. Characterization of a mitogen activated protein kinase from Pneumocystis carinii. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 275:L193-L199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vassallo, R., J. E. Standing, and A. H. Limper. 2000. Isolated Pneumocystis carinii cell wall glucan provokes lower respiratory tract inflammatory responses. J. Immunol. 164:3755-3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verde, F., D. J. Wiley, and P. Nurse. 1998. Fission yeast orb6, a ser/thr protein kinase related to mammalian rho kinase and myotonic dystrophy kinase, is required for maintenance of cell polarity and coordinates cell morphogenesis with the cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7526-7531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vohra, P. K., V. Puri, T. J. Kottom, A. H. Limper, and J. Thomas. C.F. 2003. Pneumocystis carinii STE11, an HMG-box protein, is phosphorylated by the mitogen activated protein kinase PCM. Genes Dev. 312:173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu, Z., B. Lance, C. Vargas, B. Arpinar, S. Bhandarkar, E. Kraemer, K. J. Kochut, J. A. Miller, J. R. Wagner, M. J. Weise, J. K. Wunderlich, J. Stringer, G. Smulian, M. T. Cushion, and J. Arnold. 2003. Mapping by sequencing the pneumocystis genome using the ordering DNA sequences v3 tool. Genetics 163:1299-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yale, S. H., and A. H. Limper. 1996. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: associated illness and prior corticosteroid therapy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 71:5-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]