Hepatitis C genotype-1 patients with early-stage fibrosis who relapsed after short-course combination direct-acting antiviral therapy with high-level resistant hepatitis C strains were retreated with ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 12 weeks. More than 90% achieved sustained virologic response.

Keywords: hepatitis C, direct-acting antiviral agents, retreatment, sofosbuvir, ledipasvir

Abstract

Background. The optimal retreatment strategy for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients who fail directly-acting antiviral agent (DAA)-based treatment is unknown. In this study, we assessed the efficacy and safety of ledipasvir (LDV) and sofosbuvir (SOF) for 12 weeks in HCV genotype-1 (GT-1) patients who failed LDV/SOF–containing therapy.

Methods. In this single-center, open-label, phase 2a trial, 34 participants with HCV (GT-1) and early-stage liver fibrosis who previously failed 4–6 weeks of LDV/SOF with GS-9669 and/or GS-9451 received LDV/SOF for 12 weeks. The primary endpoint was HCV viral load below the lower limit of quantification 12 weeks after completion of therapy (sustained virological response [SVR]12). Deep sequencing of the NS3, NS5A, and NS5B regions were performed at baseline, at initial relapse, prior to retreatment, and at second relapse with Illumina next-generation sequencing technology.

Results. Thirty-two of 34 enrolled participants completed therapy. Two patients withdrew after day 0. Participants were predominantly male and black, with median baseline HCV viral load of 1.3 × 106 IU/mL and Metavir fibrosis stage 1 and genotype-1a. Median time from relapse to retreatment was 22 weeks. Prior to retreatment, 29 patients (85%) had NS5A-resistant variants. The SVR12 rate was 91% (31/34; intention to treat, ITT) after retreatment. One patient relapsed.

Conclusions. In patients who previously failed short-course combination DAA therapy, we demonstrate a high SVR rate in response to 12 weeks of LDV/SOF, even for patients with NS5A resistance-associated variants.

Clinical Trials Registration. NCT01805882.

Recent advances in therapy have dramatically improved the prognosis for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The safety and efficacy of combination directly-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have been demonstrated in patients with a broad range of disease stages, from those naive to HCV therapy with minimal liver fibrosis to those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis who have failed previous interferon (IFN)-based therapies [1–4].

While DAA-only regimens have dramatically improved treatment of chronic HCV, they are expensive, and treatment still requires several months of therapy. As a result, there has been intense interest in shortening courses of DAA therapy in patients with favorable baseline characteristics, including those without advanced fibrosis. Kowdley et al demonstrated similar rates of sustained virological response (SVR) after 8 weeks compared with 12 weeks of ledipasvir (LDV) and sofosbuvir (SOF) [5] for patients without cirrhosis and naive to HCV treatment. Encouraged by high rates of response to these new shorter DAA regimens, our group has studied whether adding additional DAAs can further reduce the treatment duration in select patients [6, 7].

Combination DAA therapy for 6 weeks was successful in select populations (treatment naive and noncirrhotic patients) [6], while treatment for 4 weeks was successful for only a minority of patients [7]. Retreatment options for patients who fail short-course therapies have not been well defined.

One study of LDV and SOF for retreatment of patients who failed early, single DAA therapies in combination with IFN and ribavirin demonstrated high SVR rates [8], with an excellent safety profile [9, 10]. However, data from one study of patients with and without cirrhosis who failed 8 to 12 weeks of LDV/SOF and were retreated with 24 weeks of LDV/SOF demonstrated varied efficacy, from 100% (in patients without resistance-associated variants [RAVs]) to as low as 60% in patients who had RAVs to NS5A inhibitors [11]. Other recent data from large trials of combination DAA therapy showed that the kinetics of HCV RAVs varied by the selective pressure exerted by the drug as well as overall viral fitness [12, 13]. NS5A mutations persisted out to at least post-treatment week 48 in patients who had been treated with the NS5A inhibitor ombitasvir and up to 96 weeks after completion in patients who had failed therapy with LDV in the absence of SOF. The persistence of these RAVs for almost 2 years in the absence of selective pressure exerted by DAAs indicates that these variants replicate well and that these resistance mutations exert little fitness cost. The response of preexisting or emergent NS5A mutants to retreatment with DAA therapy is unknown. Here, we report, for the first time, highly successful retreatment with LDV/SOF in patients without liver cirrhosis who had previously failed short-course combination DAA-only LDV/SOF–containing regimens, despite high frequencies of NS5A RAVs.

METHODS

Study Design

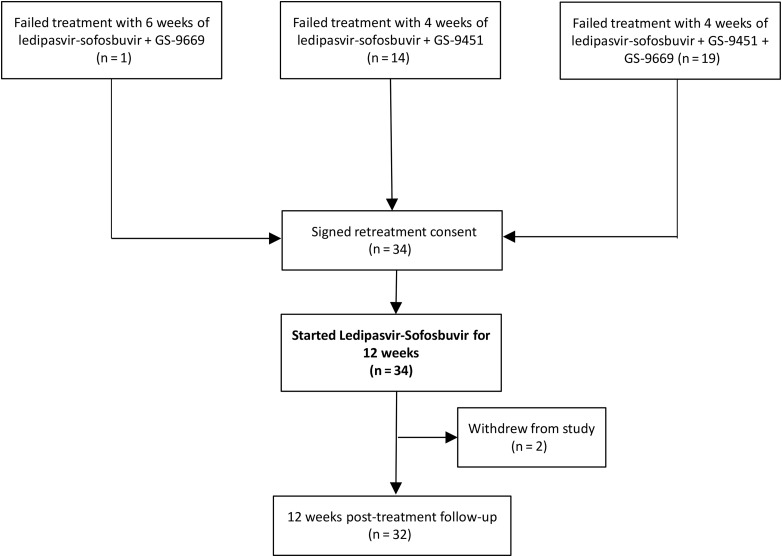

This study was conducted as a separate arm of an ongoing, phase 2a, open-label study, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) SYNERGY study (Clinical Trials.gov number NCT01805882). Patients who relapsed after 6 weeks of treatment with LDV/SOF plus GS-9669, an investigational nonnucleoside NS5B inhibitor (n = 1); after 4 weeks of LDV/SOF plus GS-9451, an investigational NS3 protease inhibitor (n = 14); or after 4 weeks of LDV/SOF plus GS-9451 and GS-9669 (n = 19) were screened at the Clinical Research Center of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) between September 2014 and December 2014. Written informed consent was attained from all study participants. Key eligibility criteria were documented infection with HCV genotype-1 (GT-1) and treatment relapse in earlier arms of the SYNERGY study, details previously published [6, 7]. The absence of cirrhosis was determined by liver biopsy within 3 years or a combination of FibroTest of <0.48 [14] and aspartate transaminase-to-platelet ratio index <1 [15] within 6 months of enrollment into the initial short course treatment arms of the NIAID SYNERGY study. Study visits were conducted primarily at the NIAID/CCMD HIV/Hepatitis C Clinic and also in community clinics in the District of Columbia as part of the Washington, DC, Partnership for AIDS Progress.

Study Oversight

The study was approved by the NIAID institutional review board and was conducted in compliance with the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and regulatory requirements. The Regulatory Compliance and Human Participants Protection Branch of NIAID served as the study sponsor and medical monitor. Gilead Sciences, Inc. provided drug and scientific input.

Efficacy Assessment

Plasma HCV RNA levels were measured using the RealTime HCV Assay (Abbott), with a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 12 IU/mL. Serum HCV RNA levels were also measured at select time points using the COBAS TaqMan HCV RNA assay, version 2.0 (Roche), with an LLOQ of 25 IU/mL.

Safety Assessment

All study participants were monitored frequently for adverse events, and clinical laboratory results were recorded while on study drugs (weeks 4, 8, and 12 after initiation of study drugs) and afterward (weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 after stopping therapy). Adverse events were graded from 1 (mild) to 4 (severe) according to the NIAID Division of AIDS toxicity table (version 1.0) [16]. Adherence was measured throughout the study using pill counts obtained by the study team members. Adherence was measured at 4-, 8-, and 12-week (end of treatment) time points.

Interleukin-28B and Interferon-Lambda 4 Genotyping

Interleukin-28B (IL-28B) genotype (rs12979860) and IFN-lambda 4 (IFN-L 4) genotype (rs368234815) were determined as previously described [17].

Deep Sequencing

Deep sequencing of the HCV NS3/NS4, NS5A, and NS5B genes (at a minimum of 5000 reads) was performed by DDL (DDL Diagnostics Laboratory, Rijswijk, Netherlands) to identify RAVs. This sequencing was completed using samples collected at baseline in all patients, at the time of relapse after short-course therapy, prior to retreatment, and at time of virologic failure in the patient who relapsed. All 3 regions were amplified by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using genotype-specific primers. PCR products were further deep-sequenced using Illumina MiSeq technology as previously described [17].

Clinical Endpoints

The primary study endpoint was the proportion of participants with plasma HCV viral load below the level of quantification 12 weeks after treatment completion (SVR12) as measured using the Roche assay. Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of participants with unquantifiable HCV viral load at specified time points during and after treatment. Safety endpoints included frequency and severity of adverse events, discontinuations due to adverse events, and safety laboratory changes.

Statistical Analyses

The primary safety and efficacy data were analyzed using an intention-to-treat population (all patients who received at least 1 dose of study medication). All missing data points were counted as successful only if the preceding and succeeding time points were obtained. Baseline demographics were described using frequency statistics. Comparisons were calculated using nonparametric tests and t tests. Data analysis was performed using PRISM 6.0 software.

RESULTS

Thirty-four patients were screened and enrolled in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants

Baseline characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1. Study participants were primarily African American (28/34, 82.4%) and male (28/34, 82.4%), with IL-28B unfavorable non-CC genotype (30/33, 90.9%). Twenty-six (76.5%) participants were infected with HCV GT-1a, and 4 (11.8%) had baseline HCV RNA >6 000 000 IU/mL. The majority of patients (33/34, 97.1%) had early-stage liver disease (stage 0–2), predominantly determined by biopsy (31/33, 93.9%). One patient (2.9%) had stage 3 fibrosis by liver biopsy. Patients initiated retreatment at an average of 25.1 (range 5–32) weeks after the end of initial therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Ledipasvir–Sofosbuvir (N = 34) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 58.9 ± 7.5 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 28 (82.3) |

| Female | 6 (17.7) |

| Race,a n (%) | |

| Black | 28 (82.3) |

| White | 6 (17.7) |

| Ethnicity,a n (%) | |

| Hispanic | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic | 34 (100) |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD | 27.3 ± 4.2 |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | |

| 1a | 26 (76.5) |

| 1b | 8 (23.5) |

| HCV RNA >800 000 IU/mL, n (%) | 21 (61.8) |

| Interleukin-28B genotype, n (%) | |

| CC | 3 (9.1) |

| CT, TT | 30 (90.9) |

| Interferon-lambda 4 genotype, n (%) | |

| TT/TT | 1 (3.0) |

| ΔG/TT, ΔG/ΔG | 32 (97.0) |

| HAI-Knodell, Metavir, or Fibrosure Fibrosis Score,b n (%) | |

| 0–2 | 33 (97.1) |

| 3 | 1 (2.9) |

| Weeks to retreatment, mean ± SD | 25.1 ± 5.5 |

| Resistance-associated variants ≥25-fold resistance, n (%) | N = 34 |

| NS5A, n (%) | 29 (85.3) |

| NS5B, n (%) | 1 (2.9) |

| NS5A and NS5B, n (%) | 1 (2.9) |

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; SD, standard deviation.

a Race and ethnicity were self-reported.

b Two (5.9%) patients had FibroTest/aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index for eligibility, 32 (94.1%) patients completed liver biopsies scored using the histology activity index-Knodell or Metavir systems.

Virologic Response

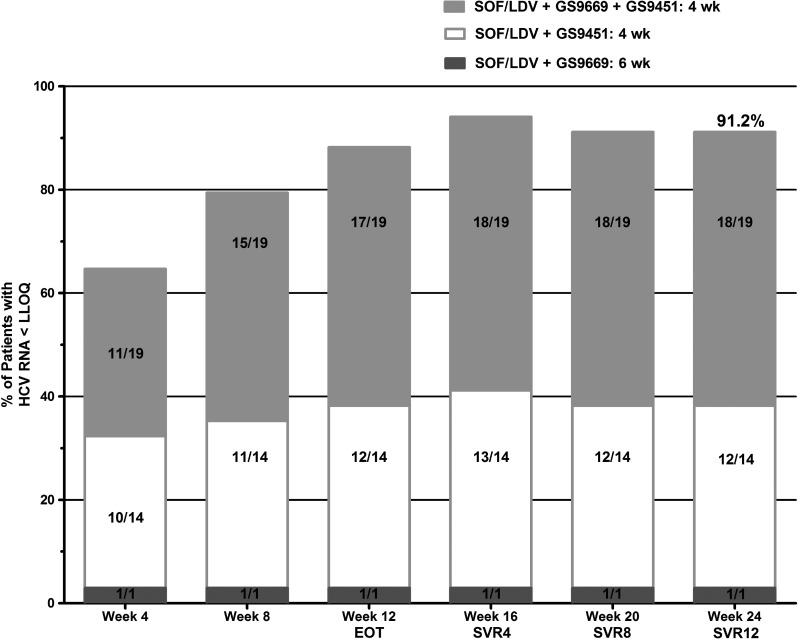

Thirty-one participants (91.2%) treated with LDV/SOF had HCV RNA levels below LLOQ at week 4 as measured by the Roche assay (Supplementary Table 1). Two patients were lost to follow-up after their day 0 visit and subsequently withdrew from the study. One patient had HCV RNA below LLOQ at week 4 followed by a quantifiable HCV RNA of 48 886 IU/mL at week 8 but went on to achieve SVR12. This patient admitted to nonadherence to at least 2 doses of study medication prior to the week 8 visit and did not return for a week 12 end-of-treatment visit. At the end of treatment (week 12), 31 patients (91.2%) had HCV RNA levels below LLOQ as measured by the Roche assay. Three patients did not attend the week 12 visit, including the 2 patients who were lost to follow-up. The third patient (described above) had transitory viral rebound at week 8 but went on to achieve SVR12.

Overall, 91.2% (31/34) of patients retreated with 12 weeks of LDV/SOF achieved SVR12. One patient experienced viral relapse (Supplementary Table 1). The participant who relapsed had suppressed HCV viremia by week 4 on therapy, maintained through the end of treatment and week 4 post-treatment, but had quantifiable HCV RNA of 181 737 IU/mL at week 8 post-treatment (only Abbott assay available). This patient denied any reexposure or high-risk behavior and reported 100% adherence with study medications.

For treatment response, as measured by the Abbott assay, by original short-course combination DAA regimen in an intention-to-treat analysis, see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA lower than the level of quantification (LLOQ). Treatment response, as measured by HCV RNA <LLOQ by the Abbott assay, was included in this intention-to-treat analysis of all 34 participants. Note: Two patients were lost to follow-up after their day 0 visits and were categorized as having HCV RNA >LLOQ at all subsequent visits. One patient missed the week 12, end-of-treatment (EOT), visit. Because that patient's HCV viral load was detectable at the preceding visit, the HCV viral load was counted as detectable at week 12. This participant did go on to achieve sustained virological response (SVR) 12. Abbreviations: LDV, ledipasvir; SOF, sofosbuvir.

Analysis of HCV Resistance–Associated Variants

Prior to initial therapy, 9 (9/33, 27.3%) participants had NS5A RAVs, although in only 6 (6/33, 18.2%) did this comprise a majority of the viral population. Prior to retreatment with LDV/SOF, and similar to the time of initial relapse, the NS5A RAVs K24R, M28T, Q30H/R/L/T, L31M/V/I, and Y93H/N were observed in 29/34 patients (85%). These NS5A RAVs have been reported to confer high levels of resistance (>25-fold in all 29, >100-fold in 28/29, and >1000 in 8/29 patients, respectively) to LDV in vitro [18]. All but 3 of these 29 patients with baseline RAVs went on to achieve SVR12. Two of these 3 patients withdrew from the study prior to week 4. Among the 27 patients who had NS5A RAVs prior to retreatment and completed the study, SVR was achieved in 20/20 and 6/7 patients with NS5A RAVs conferring <1000-fold and >1000-fold reduced susceptibility to LDV, respectively. The patient who experienced viral relapse had an L31M NS5A RAV at baseline and developed a Y93H NS5A RAV in addition to maintaining the L31M at relapse after short-course therapy. The double-mutant L31M/Y93H confers >1000-fold reduced susceptibility to LDV. Both of these mutations persisted for 23 weeks in the absence of therapy and were detected again prior to retreatment. At relapse, these RAVs were again documented along with 2 emergent NS5B RAVs: S282T and V321I at 17.7% and 9.3% of viral sequence reads, respectively. Selected NS5A and NS5B resistance profiles to LDV and SOF of all study participants are shown in Table 2. Of note, variants within NS3/4 were unchanged throughout retreatment (data not shown).

Table 2.

Selected NS5A and NS5B Resistance-Associated Variants by Study Participant

| Patient | Genotype | Previous Treatment | NS5A Mutant (% Population) |

NS5B Mutant (% Population) |

Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Relapse | Prior to Retreatment |

Relapse | Baseline | Relapse | Prior to Retreatment | Relapse | |||||

| Resistance-Associated Variants | Fold Resistance | |||||||||||

| D15 | 1b | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | Y93H (1.1%) Y93C (2.0%) | Y93H (1.0%) Y93C (3.9%) | >1000 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D16 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9669 | ND | ND | K24R (8.0%) M28T (75.0%) Q30L (24.5%) Q30H (74.4%) | >100 | N/A | ND | ND | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D17 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | Q30R (28.4%) L31M (70.9%) | Q30R (17.1%) L31M (79.8%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | Withdrawn |

| D18 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | None | None | N/A | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D19 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | L31M (98.7%) | L31M (>99%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D20 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | Q30H (>99%) Y93H (>99%) | Q30H (>99%) Y93H (97.0%) | >1000 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D21 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | None | None | N/A | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D22 | 1b | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | L31V (6.2%) L31M (45.9%) L31I (47.9%) | L31I (31.9%) L31M (67.0%) | >25 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D23 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | Q30R (10.5%) Q30K (13.1%) L31V (2.3%) L31M (74.7%) | L31M (>99%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D24 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | Q30R (20.1%) L31M (70.8%) | Q30R (3.4%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D25 | 1b | LDV/SOF + GS-9451a | L31M (94.1%) | L31M (>99%) Y93H (>99%) | L31M (>99%) Y93H (28.6%) | >1000 | L31M (>99%) Y93H (>99%) | None | None | None | S282T (17.7%) V321I (9.3%) | Relapse |

| D26 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | None | None | N/A | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D27 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | L31M (>99%) | L31M (>99%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D28 | 1b | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | Y93H (>99%) | Y93H (>99%) | Y93H (>99%) | >1000 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | Withdrawn |

| D29 | 1b | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | None | None | N/A | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D30 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | L31M (>99%) | L31M (>99%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D31 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | M28T (1.4%) Q30H (2.6%) Q30R (56.8%) L31M (34.3%) S38F (2.3%) | Q30H (1.2%) Q30R (57.8%) L31M (11.9%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D32 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | Q30R (89.2%) | Q30R (4.4%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D33 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | Q30R (1.2%) Q30H (22.7%) | Q30R (1.7%) Q30H (60.8%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D34 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | L31M (65.8%) | L31M (>99%) | L31M (>99%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D35 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | L31M (14.3%) | L31M (>99%) | L31M (>99%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D36 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | Y93N (45.0%) | Y93N (>99%) | Y93N (>99%) | >1000 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D37 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | Q30H (1.2%) | Q30H (2.7%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D38 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | L31M (>99%) | L31M (>99%) | L31M (98.9%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D39 | 1b | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | L31M (8.1%) Y93H (>99%) | Y93H (>99%) | Y93H (>99%) | >1000 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D40 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | None | None | N/A | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D41 | 1b | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | Y93H (>99%) | Y93H (>99%) | >1000 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D42 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | M28T (1.6%) Q30H (45.9%) Q30R (53.9%) | Q30R (24.9%) Q30H (74.6%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D43 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 | None | L31M (98.9%) | Q30H (56.1%) L31M (43.8%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D44 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | K24R (89.5%) L31M (>99%) |

K24R (75.6%) L31M (>99%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D45 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | L31M (1.9%) | L31M (98.9%) | L31M (>99%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D46 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | Q30R (>99%) | Q30R (8.6%) L31M (26.7%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D47 | 1a | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | None | Q30H (1.4%) Q30R (10.9%) L31M (84.4%) |

Q30R (1.2%) L31M (98.1%) | >100 | N/A | None | None | None | N/A | SVR12 |

| D48 | 1b | LDV/SOF + GS-9451 + GS-9669 | Q30T (>99%) L31V (>99%) Y93H (>99%) | Q30T (>99%) L31V (>99%) Y93H (>99%) |

Q30T (>99%) L31V (>99%) Y93H (>99%) | >1000 | N/A | None | None | L159F (3.1%) | N/A | SVR12 |

Abbreviations: LDV, ledipasvir; N/A, not applicable; ND, not done; SOF, sofosbuvir; SVR, sustained virological response.

a Received therapy for 6 weeks; all others treated for 4 weeks.

Safety

Of the 34 patients who started study medications, 2 were lost to follow-up after day 0 and later withdrew. Eighty-eight percent (30/34) of patients experienced adverse events, most of which were mild in severity. The most common adverse event was grade 1 constipation (n = 2, 5.9%; Table 3). One serious adverse event occurred: a single episode of chest pain in a patient who had used cocaine. This was deemed to be unrelated to the study drug.

Table 3.

Adverse Events and Laboratory Abnormalities Related to Study Drug During Treatment Period

| Adverse Event or Laboratory Abnormality | Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir (n = 34) |

|---|---|

| Any AE during treatment,a n (%) | 30 (88) |

| Grade 3 | 7 (21) |

| Grade 2 | 21 (62) |

| Treatment-related AEb | |

| Grade 3 | 3 (9) |

| Grade 2 | 7 (21) |

| Any serious AE during treatment, n (%) | 1 (3) |

| Treatment-relatedb | 0 (0) |

| AE leading to permanent study drug discontinuation | 0 (0) |

| Death | 0 (0) |

| Common AE,c n (%) | |

| Constipation | 2 (6) |

| All graded lab abnormalities during treatment, n (%) | 30 (88) |

| Elevated cholesterol | 9 (29) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 3 (9) |

| Hypoglycemia | 4 (12) |

| Hyperglycemia | 6 (18) |

| Elevated serum creatinine | 3 (9) |

| Blood pancreatic amylase increased | 3 (9) |

| Absolute neutrophil count decreased | 2 (6) |

Abbreviation: AE, adverse event.

a Treatment period includes time on study medication and 30 days after discontinuation.

b As assessed by the study team.

c Common AEs were those occurring in ≥5% of patients in any treatment group.

No grade 4 laboratory abnormalities occurred, but 3 patients experienced grade 3 laboratory abnormalities. Hyperglycemia was detected while on study medications in one patient with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Two patients, one of whom had an elevated cholesterol measurement at baseline, developed grade 3 cholesterol elevations while on study medications.

DISCUSSION

In this proof-of-concept study, patients with HCV (GT-1) infection who had accumulated RAVs during previous short-course combination DAA therapy containing LDV/SOF achieved an SVR12 rate of 91% when retreated with 12 weeks of LDV/SOF. Presence of high-level RAVs, regardless of their proportion of the overall viral population, has been associated with reduced efficacy of short-course therapy [19, 20]. Here, the response rate was high in patients with NS5A RAVs. Of the 27 patients with mutations associated with >25-fold baseline NS5A resistance in vitro who completed 12 weeks of therapy, 26 (96.2%; n = 20 <1000-fold and n = 6 >1000-fold reduced susceptibility to LDV) went on to achieve SVR12. These specific RAVs have been previously identified in patients who failed LDV-containing regimens [21, 22] and also demonstrated in in vitro phenotypic assays to have diminished binding to LDV [23]. The patient who relapsed had HCV with >1000-fold NS5A RAVs L31M and Y93H prior to retreatment and NS5B RAVs S282T and V321I emerged following retreatment, both of which have been shown to reduce in vitro susceptibility to SOF [18, 24]. The S282T, in particular, has rarely been reported in clinical trials in patients who failed SOF-based regimens in clinical trials [24, 25].

Retreatment was safe and extremely well tolerated. No patient discontinued the drugs due to adverse events. Side effects were generally mild and consistent with previously published studies of LDV/SOF [1, 2].

Our patient population was predominantly composed of black men, a population often underrepresented in clinical trials, and an important population to confirm efficacy of HCV therapeutic options. Our cohort also was predominantly (>70%) infected with genotype-1a infection, the predominant HCV genotype in the US HCV epidemic and 91% IL-28B non-CC genotype.

As DAAs are used more widely, the relevance of NS5A RAVs will have to be better delineated. Some of these RAVs will be preexisting and part of the natural variation (quasispecies) that exist within an infected but DAA-naive patient and some will be the result of selection, that is, RAVs that emerge in patients who relapse. Whether RAVs will be important for determining the success of specific drug therapies or will influence the optimal duration of therapy remains to be seen. This study did not assess the efficacy of retreatment for patients with cirrhosis or for patients who failed 8, 12, or 24 weeks of therapy. The influence of duration of initial treatment on emergence or persistence of RAVs, which was shown to be a factor in the success of retreatment by Lawitz et al [11], could predict response to retreatment regimens. Our data do suggest, however, that the presence of RAVs identified here do not preclude successful retreatment with some or all of the drugs used in the initial regimen.

In summary, our data support that retreatment with LDV/SOF is a safe, effective, and tolerable option for HCV-infected patients with early-stage hepatic fibrosis who have previously failed short-course combination DAA therapy containing LDV/SOF. If successful, short 4–6 week durations of combination DAA therapy are developed and approved, retreatment of select failures with 12 weeks of LDV and SOF may be part of a reasonable treatment strategy.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://cid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. Study drugs were provided by Gilead. We thank Erin Rudzinski for clinical monitoring support; Judith Starling for pharmacy; John Tierney for regulatory support; Richard Williams and Mike Mowatt for technology transfer support; Marc Teitelbaum, the sponsor medical monitor; Mary Hall for protocol support; Cathy Rehm and Sara Jones for laboratory support; and Senora Mitchell for clinic support.

Contributors. E. M. W. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. E. M. W. and S. Kattakuzhy searched the published literature. A. K., S. Kottilil, A. N., M. M., and H. M. contributed to the study design. E. M. W., S. Kattakuzhy, A. K., Z. S., M. M., S. S., A. P., A. N., R. S., C. G., and E. A. collected data. E. M. W., S. Kattakuzhy, A. K., S. S., Z. S., and M. M. analyzed the data. E. M. W., S. Kattakuzhy, A. K., H. Mo, A. O., and H. Masur interpreted the data. E. M. W., Z. S., M. M., and S. S. contributed to the figure design. E. M. W. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors participated in the review of the article.

Disclaimer. The views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services are not necessarily reflected in this content. The U.S. Government does not endorse any trade names, commercial products, or organizations mentioned.

Financial support. The study sponsor was the Regulatory Compliance and Human Participants Protection Branch of NIAID. The study sponsor also reviewed and approved the study through a peer-review process and study management. The study sponsor did not design nor play a role in designing the study; collecting, analyzing, or interpreting the data; or preparing, reviewing, approving, or submitting the manuscript. This research was supported, in part, by a collaborative research and development agreement between NIAID, Clinical Center, NIH, and Gilead Sciences, Inc., and by the German Research Foundation, clinical research unit KFO 129. These entities did not have a role in the writing of the manuscript or decision to submit for publication.

Potential conflicts of interest. H. Mo, P. S. P., G. M. S., A. O. and J. M. are employed by Gilead Sciences. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1483–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1889–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferenci P, Bernstein D, Lalezari J et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1983–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poordad F, Hezode C, Trinh R et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1973–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1879–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohli A, Osinusi A, Sims Z et al. Virological response after 6 week triple-drug regimens for hepatitis C: a proof-of-concept phase 2A cohort study. Lancet 2015; 385:1107–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kattakuzhy S, Sidharthan S, Wilson EM et al. Predictors of sustained viral response to 4–6 week duration therapy with ledipasvir + sofosbuvir + GS-9451 +/− GS-9669 in early and advanced fibrosis (NIH/UMD synergy trial). J Hepatology 2015; 62(S2):S669. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourliere M, Bronowicki JP, de Ledinghen V et al. Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin to treat patients with HCV genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis non-responsive to previous protease-inhibitor therapy: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial (SIRIUS). Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alqahtani SA, Afdhal N, Zeuzem S et al. Safety and tolerability of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with and without ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection: analysis of phase III ION trials. Hepatology 2015; 62:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osinusi A, Kohli A, Marti MM et al. Re-treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection after relapse: an open-label pilot study. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161:634–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawitz E, Flamm S, Yang JC et al. Retreatment of patients who failed 8 or 12 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir-based regimens with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for 24 weeks. J Hepatology 2015; 62(S2):S192. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dvory-Sobol H, Wyles D, Ouyang W et al. Long-term persistence of HCV NS5A variants after treatment with NS5A inhibitor ledipasvir. J Hepatology 2015; 62(S2):S221. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan P, Tripathi R, Schnell G et al. Long-term follow-up of treatment-emergent resistance-associated variants in NS3, NS5A and NS5B with paritaprevir/r-, ombitasvir- and dasabuvir-based regimens. J Hepatology 2015; 62(S2):S220. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poynard T, Lebray P, Ingiliz P et al. Prevalence of liver fibrosis and risk factors in a general population using non-invasive biomarkers (FibroTest). BMC Gastroenterol 2010; 10:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin ZH, Xin YN, Dong QJ et al. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatology 2011; 53:726–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of AIDS. Division of AIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events, Version 1.0. [Updated August 2009]. Available at: http://rsc.tech-res.com/Document/safetyandpharmacovigilance/Table_for_Grading_Severity_of_Adult_Pediatric_Adverse_Events.pdf. Accessed 19 October 2015.

- 17.Osinusi A, Meissner EG, Lee YJ et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C genotype 1 in patients with unfavorable treatment characteristics: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 310:804–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lontok E, Harrington P, Howe A et al. Hepatitis C virus drugs resistance-associated substitutions: state of the art summary. Hepatology 2015; doi:10.1002/hep.27934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohli A, Kattakuzhy S, Sidharthan S et al. Four-week directly acting anti-HCV regimens in HCV genotype-1 patients without cirrhosis: a phase 2a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kattakuzhy S, Wilson EM, Sidharthan S et al. Six-week combination directly acting anti-HCV therapy induces moderate rates of sustained virologic response in patients with advanced liver disease. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:440–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong KA, Worth A, Martin R et al. Characterization of hepatitis C virus resistance from a multiple-dose clinical trial of the novel NS5A inhibitor GS-5885. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57:6333–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng G, Peng B, Corsa A et al. Antiviral activity and resistance profile of the novel HCV NS5A inhibitor GS-5885. J Hepatology 2012; 56(S2):S464. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon HJ, Xing W, Chan K et al. Direct binding of ledipasvir to HCV NS5A: mechanism of resistance to an HCV antiviral agent. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0122844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Svarovskaia ES, Dvory-Sobol H, Parkin N et al. Infrequent development of resistance in genotype 1–6 hepatitis C virus-infected subjects treated with sofosbuvir in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1666–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gane EJ, Stedman CA, Hyland RH et al. Nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:34–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.