Abstract

Context:

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) increases the risk of most non-communicable diseases; gathering information about its prevalence can be very effective in formulating preventive strategies for metabolic diseases. There are many different studies about the prevalence of MetS in Iran, but the results and the study populations of these studies are very different; therefore, it is very important to have an overall estimation of its prevalence in Iran.

Objectives:

This study systematically reviewed the findings of all available studies on MetS in the adult Iranian population and estimated the overall prevalence of MetS in this population.

Data Sources:

International databases (Scopus, ISI Web of Science, and PubMed) were searched for papers published from January, 2000 to December, 2013 using medical subject headings (MeSH), Emtree, and related keywords (metabolic syndrome, dysmetabolic syndrome, cardiovascular syndrome, and insulin resistance syndrome) combined with the words “prevalence” and “Iran.” The Farsi equivalent of these terms and all probable combinations were used to search Persian national databases (IranMedex, Magiran, SID, and Irandoc).

Study Selection:

All population-based studies and national surveys that reported the prevalence of MetS in healthy Iranian adults were included.

Data Extraction:

After quality assessment, data were extracted according to a standard protocol. Because of between-study heterogeneity, data were analyzed by the random effect method.

Results:

We recruited the data of 27 local studies and one national study. The overall estimation of MetS prevalence was 36.9% (95% CI: 32.7 - 41.2%) based on the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) criteria, 34.6% (95% CI: 31.7 - 37.6%) according to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), and 41.5% (95% CI: 29.8 - 53.2%) based on the Joint Interim Societies (JIS) criteria. The prevalence of MetS determined by JIS was significantly higher than those determined by ATP III and IDF. The prevalence of MetS was 15.4% lower in men than in women (27.7% versus 43.1%) based on the ATP III criteria, and it was 11.3% lower in men based on the IDF criteria; however according to the JIS criteria, it was 8.4% more prevalent in men.

Conclusions:

There is a high prevalence of MetS in the Iranian adult population, with large variations based on different measurement criteria. Therefore, prevention and control of MetS should be considered a priority.

Keywords: Metabolic Syndrome, Prevalence, Meta-Analysis, Iran

1. Context

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) (1) is a collection of interrelated disorders, namely obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and hypertension. Each MetS component increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and all-cause mortality. According to a study conducted by Gami et al., the synergistic effects of these disorders increase the risk of further disease and mortality much more than the sum of the risk increases from each component (2). However, other studies have provided different results (3-5). MetS increases total mortality from cardiovascular disease by 1.5 fold and risk for cardiovascular death by 2.5 fold (6). Moreover, individuals with MetS are five times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes (7). The main causes of MetS remain to be determined. However, it seems that abdominal obesity and insulin resistance are the key components (6-8). The most commonly used definitions for MetS are those provided by the world health organization (WHO), the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III), the international diabetes federation (IDF), and the joint interim societies (JIS), as presented in following sections.

MetS is a common disorder, and given that its predisposing factors including obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and exposure to some environmental factors are escalating in many countries, the incidence of MetS is increasing as well (9). Therefore, MetS is now an emerging health problem at the public and individual levels. Because programs for primary prevention of non-communicable diseases emphasize appropriate evaluation and management of risk factors, (10) gathering reliable information about the prevalence of MetS in various populations can be very effective in the planning and use of preventive strategies for such diseases.

The prevalence of MetS is not only influenced by excess weight but also by ethnic predisposition, gender, age, race, cultural and lifestyle habits, and environmental factors; thus, its prevalence has large variations in different societies (11, 12). Grundy reported that between 20% and 30% of the adult population in most countries have MetS (13). Asians have an ethnic predisposition to MetS (14, 15), and it is of special concern for Middle Eastern populations, which are predicted to experience the greatest global burden of diabetes by 2020 (14). As a country in this region, Iran is reported to have one of the highest prevalence rates of MetS worldwide (16). The nationwide prevalence of MetS is reported to be 35.6% based on ATP III criteria (14). In metropolitan Tehran, 42% of women and 24% of men have MetS, with a total age-standardized prevalence of 33.7% (16). Iran is a vast country with about 70 million people and different ethnicities including Turkish, Kurdish, Arab, Fars, Turkmen, and Baluch living in different regions of the country. The difference in their cultures, socioeconomic status, lifestyle habits, and environmental factors may cause variation in the prevalence of MetS (17-23), so it is very important to have an overall estimation of its prevalence in Iran.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to systematically review the findings of available studies and to combine them to estimate the overall prevalence of MetS in Iran. The other objective of this study was to explore potential sources of heterogeneity in the study findings.

3. Data Sources

The English-language medical literature was searched from January, 2000 to December, 2013 in Scopus, ISI Web of Science, and PubMed. Using medical subject headings (MeSH), Emtree, and related keywords, we searched for “metabolic syndrome,” “dysmetabolic syndrome,” “cardiovascular syndrome,” and “insulin resistance syndrome” combined with “prevalence” and “Iran,” including all subheadings. The Farsi equivalent of these terms and all probable combinations were used to search in Persian databases (i.e., IranMedex, Magiran, SID, and Irandoc). Moreover, the references of selected citations and non-published national surveys were hand-searched. In addition, when articles had incomplete data, at least three e-mails were sent to corresponding authors.

4. Study Selection

All types of studies, including local and national surveys that reported the prevalence of MetS and were conducted in Iran were reviewed. However, the final review was limited to studies with random sampling on healthy adults and/or on the general population who were aged 18 years and over. The studies that were conducted on subjects with known health disorders were excluded. In the case of multiple publications from the same population, only the largest study was included. The STROBE (strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) statement was used for quality control of the studies (24). The quality of studies was assessed according to variables related to the study objectives, characteristics of the study population, clearly explained inclusion/exclusion criteria, data collection method, as well as the validity, explicit findings, and appropriate data analysis methods of the studies. Non-qualified studies were excluded. Moreover, duplicated citations were not included.

5. Data Extraction

After determining the qualified papers, data were extracted according to a standard protocol. To improve accuracy and critical appraisal, data extraction was conducted by two independent researchers, and disputes between researchers were resolved by consensus. The following items were extracted from the studies:

General information: first author’s name, study location, study date, publication date, definition used for MetS

Population characteristics: sex groups, mean age, and age range

Methodological information: sampling method, sample size, scope of study (urban, rural, or survey)

Study outcomes: reported prevalence of MetS extracted by sex (men, women, and total), and its 95% confidence interval (CI) concerning the prevalence of MetS components.

5.1. Statistical Analysis

Prevalences are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A Chi-square-based Q test was used to analyze the heterogeneity of reported prevalences and was regarded to be statistically significant at P < 0.1. Tau-square (τ2) was estimated (using the restricted likelihood method) as the indicator of heterogeneity. After using the heterogeneity test, we found significant variations between study findings; thus, in order to obtain better results, the random effect model was used to estimate the overall prevalence of MetS in Iran. The findings are described in forest plots (the point estimations and their 95% CI). In the next step, meta-regression was used to check the effects of age and publication date as possible sources of heterogeneity among the study findings. The analyses were conducted with STATA software, version 11.0.

6. Results

In our primary search, and after removing duplicates, we found 379 relevant articles. After excluding non-eligible studies, we recruited the data of 27 local studies and one national study, which included all provinces of Iran. The details of our study selection method are shown in Figure 1. In each selected study, the prevalence of MetS was reported according to different criteria. Among the 28 studies, we found 21 reports given according to ATP III (including 12 based on ATP III (25) and nine based on modified ATP III (26)), six reports according to IDF (7), and one report according to the Iranian modified IDF (27), one report according to the WHO criteria, (28) and five reports according to the JIS criteria (29).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of the Study Selection Process.

The findings of this systematic review are summarized in Table 1. For data analysis, we merged the ATP III and modified ATP III reports. The reports of IDF and Iranian modified IDF (27) were also merged; the meta-analysis was performed on three groups of reports: ATP III, IDF, and JIS. The only study that had used the WHO criteria for MetS was excluded from the analysis. If an article reported the prevalence of MetS according to both ATP III and modified ATP III, both were used as separate reports in the analysis.

Table 1. The Prevalence (95% CI) of Metabolic Syndrome in Iranian Adults in Population-Based Studies.

| Reference | Location and Study Type | Study Population | Sampling Method | Study Date | Publication Date | Age Range, Y | Mean Age (Mean ± SD) | Gender | Urban/Rural | Sample Size | Criteria | Considerations | Prevalence of MetS (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faam et al. (30) | Tehran (TLGS, phase 3), local study | Healthy adults | Random sampling | 2005 - 2008 | 2013 | 20 - 70 | T: 40.7 ± 13.9 | Both | U | T: 4,665; M: 1,976; F: 2,689 | JIS | Participants who had diabetes mellitus (n = 390) or body mass index (BMI) less than 18 kg/m (n = 152) were exclude.Waist circumference cut-off points were not mentioned | T: 31.5 (30.1 - 32.8) |

| Ziaee et al. (31) | Mindoodar district of Qazvin, local study | Healthy adults | Multistage random cluster sampling | 2010 - 2011 | 2013 | 20 - 78 | T: 40.08 ± 10.33; M: 42.31 ± 10.56; F: 38.02 ± 9.69 | Both | R | T: 1,107; M: 529; F: 578 | JIS | Waist circumference cut-off points were ≥ 94 cm in men or ≥ 80 cm in women | T: 39.3 (36.4 - 42.2) |

| Movahed et al. (32) | Bushehr Port, (Iranian Multicentral Osteoporosis Study), local study | Postmenopausal women | Randomcluster sampling | 2006 | 2012 | 50 - 83 | F: 58.78 ± 7.8 | F | U | T: 382 | ATP III | T: 68.32 (63.3 - 72.9) | |

| Yousefzadeh et al. (33) | Kerman,local study | Healthy adults | Random sampling | 2012 | 15 - 75 | T: 46.52 ± 14.76 | Both | U | T: 200; M: 81; F: 119 | Modified ATP III | T: 60 (52.8 - 66.8) | ||

| Azimi-Nezhad et al. (34) | Greater Khorasan province, (National Survey on Non-communicable Disease), local study | Healthy adults | Multistage random sampling | 2003 | 2012 | 35 - 55 | Both | T: 1,194; M: 58; F: 605 | Modified ATP III | T: 42.66 (39.8 - 45.4); M: 30.1 (26.3 - 33.9); F: 55.0 (50.9 - 59.0) | |||

| Hadaegh et al. (35) | Tehran (TLGS, phase 1), local study | Subjects free of CVD | Random sampling | 1999 - 2001 | 2012 | 40 ≤ | T:54 ± 9.8; M: 55.3 ± 10.5; F: 53.0 ± 9.3 | Both | U | T: 4,248; M:1,856 F:2,392 | JIS | Waist circumference cut-off point was ≥ 94.5 cm for both Iranian men and women | T: 51.6 (50 - 53.1); M: 45.7 (43.4 - 47.9); F: 56.2 (54.1 - 58.1) |

| Talaei et al. (36) | Isfahan, Arak and Najafabad, local study | Healthy adults | Multistage random sampling | 2001 | 2012 | ≥ 35 | T: 50.7 ± 11.6; M: 51.1 ± 11.9; F: 50.3 ± 11.3 | Both | Both | T: 6,323; M: 3,068; F: 3,255 | Modified ATP III | T: 37.1 (35.9 - 38.3); M: 21.5 (20.0 - 23.0); F: 51.7 (49.9 - 53.4) | |

| Zarkesh et al. (37) | Tehran, (TLGS, phase III), local study | Healthy adults | Random sampling | 2006 - 2008 | 2012 | ≥ 19 | T: 46.1 ± 16.1 | Both | U | T: 365; M: 134; F: 231 | JIS | Waist circumference cut-off point was > 89 cm in men and > 91 cm in women | T: 43.8 (38.6 -49) |

| Ghorbani et al. (38) | Semnan, local study | Healthy adults | Multistage random sampling | 1384 | 2012 | 30 - 70 | T: 45.7 ± 10.06; M: 46.6 ± 10.4; F: 45.1 ± 9.8 | Both | Both | T: 3,799; M: 1,695; F: 2,104 | Modified ATP III; IDF | T: 28.5 (27.1 - 29.9); M: 17 (15.2 - 18.8); F: 37.8 (35.7 - 39.8). T: 35.8 (34.3-37.3); M: 25.4 (23.3-27.5); F: 44.1 (41.9-46.2) | |

| Rezaianzadeh et al. (39) | Yazd (phase I of Yazd Healthy Heart Program) | Healthy adults | Cluster sampling | 2004 - 2005 | 2012 | 20 - 74 | T: 48.75 ± 15; M: 48.8 ± 15; F: 48.6 ± 15 | Both | U | T: 2,000 | IDF | T: 30.16 (0.02); M: 31.6 (0.02); F: 30.2 (0.02) | |

| Hosseinpanah et al. (40) | Ghazvin, Kermanshah, Golestan, and Hormozgan (Iranian PCOS Prevalence Study), multicity study | Females | Stratified, multistage cluster sampling | 2009 - 2010 | 2011 | 18 - 45 | T: 36 ± 7.5 | F | U | T: 423 | JIS | Waist circumference cut-off point was ≥ 91 cm | T: 18.3 (15.1 - 21.5) |

| Esteghamati et al. (27) | Tehran, (the Third National Surveillance of Risk Factors of Non-communicable Diseases), local study | Individuals with body mass index < 18.5 kg/m2 were excluded | Random Cluster sampling | 2007 | 2011 | 25 - 64 | T: 43.18 ± 0.3; M:43.4 ± 0.3; F: 43.0 ± 0.3 | Both | U | T: 2,660; M: 1,245; F: 1,415 | Modified ATP III; Iranian modified IDF (waist circumference cut-off point was ≥ 90 cm for both men and women) | Individuals with self-reported diabetes were excluded | T: 38.09 (36.23 - 39.9); M: 29.9 (27.3 - 32.5); F: 45.3 (42.6 - 47.9). T: 38.4 (36.5-40.2); M: 39.1 (36.3-41.8); F: 37.8 (35.2-40.3) |

| Sahebari et al. (41) | Great Khorasan province, local study | Healthy adults | 2011 | T: 45.6 ± 12; M: 44.7 ± 12; F: 44.1 ± 13 | Both | Both | T: 500; M: 69; F: 431 | ATP III; IDF | T: 53.8 (49.3 - 58.2); M: 21.7 (12.7 - 33.3); F: 51 (46.2 - 55.8). T: 34.2 (30 - 38.5); M: 29 (18.6 - 41.1); F: 57.8 (52.9 - 62.4) | ||||

| Esmaillzadeh et al. (42) | Tehran, local study | Female teachers | Multistage random cluster sampling | 2007 | 2011 | 40 - 60 | T: 49 ± 6 | F | U | T: 486 | ATP III | Subjects taking antihypertensive, lipid lowering, or antidiabetic medications were excluded | T: 30 (25.9 - 34.3) |

| Esteghamati et al. (43) | All 30 provinces of Iran (the Third National Surveillance of Risk Factors of Non-Communicable Diseases ) (SuRFNCD), national study | Healthy adults | Random cluster sampling | 2007 | 2011 | 25 - 64 | T: 43.59 ± 11.2; M: 43.69±11.6; F: 43.5 ± 10.9 | Both | Both | T: 3,045; M: 1,468; F: 1,577 | IDF | Waist circumference cut-off point was ≥ 90 cm in both males and females | T: 39.9 (38.1 - 41.6); M: 38.2 (35.7 - 40.7); F: 41.5 (39 - 43.9) |

| Ramezani et al. (44) | Ghazvin, Kermanshah, Golestan, and Hormozgan, multicity study | Healthy adults | Multistage random cluster sampling | 2011 | 18 - 45 | F | U | T: 914 | Modified ATP III | T: 17.5 (15.09 - 20.1) | |||

| Ghasemi et al. (45) | Tehran, (TLGS, phase 3), local study | Healthy adults | Multistage, stratified random cluster sampling | 2007 - 2008 | 2010 | 60 - 90 | Both | U | T: 137; M: 89; F: 48 | ATP III | T: 43.8 (35.3 - 52.5); M: 30.3 (21.03 - 40.99); F: 68.8 (53.6 - 61.3) | ||

| Delavari et al. (14) | All 30 provinces in Iran, national study | Healthy adults | Multistage Random cluster sampling | 2007 | 2009 | 25 - 64 | T: 41.3 ± 3.81; M: 41.5 ± 2.64; F: 41.2 ± 2.74 | Both | Both | T: 2,966 M: 1,431; F: 1,535 | ATP III; Modified ATP III | T: 35.6 (34.1 - 37.1); M: 28.8 (27.0-30.5); F: 42.8 (40.4 - 45.1). T: 42.3 (40.7-43.8); M: 36.3 (34.4-38.1); F: 48.5 (46.2-50.9) | |

| Jalali et al. (46) | Akbar abad Koar Fars near Shiraz, local study | Healthy adults | Simple random sampling | 2008 | 2009 | 18 - 90 | T: 38.7 ± 14.3; M: 40.5 ± 15.9; F: 37.4 ± 13.7 | Both | R | T: 1,402; M: 360; F: 1,042 | ATP III; Modified ATP III; IDF | T: 25.6 (23.3 - 27.9); M: 29.16 (24.5 - 34.1); F: 24.28 (21.7 - 27.0). T: 29 (26.5 - 31.4). T: 33 (30.4 - 35.4) | |

| Delavar et al. (47) | Babol, local study | Female adults | Systematic random sampling | 2009 | 30 - 50 | F: 40.2 ± 0.2 | F | U | T: 944 | ATP III | T: 31 (28.1-33.9) | ||

| Sharifi et al. (48) | Zanjan, local study | Healthy adults | Stratified, multistage random sampling | 2002 - 2003 | 2009 | > 20 | Both | U | T: 2,941; M: 1,396; F: 1,545 | Modified ATP III | T: 23.7 (22.1 - 25.2); M: 23.1 (20.8 - 25.2); F: 24.4 (22.2 - 26.5) | ||

| Sarrafzadegan et al. (49) | Isfehan, Irak, and Najaf-Abad, local study | Healthy adults | Two-stage random cluster sampling | 2000 - 2001 | 2008 | ≥ 19 | Both | Both | T: 12,514; M: 6,123; F: 6,391 | ATP III | T: 23.3 (22.5 - 24.0); M: 10.7 (9.9 - 11.4) F: 35.1 (33.9 - 36.2) | ||

| Hadaegh et al. (50) | Tehran, (TLGS, phase 1), local study | Healthy adults | Multistage random cluster sampling | 1999 - 2001 | 2008 | ≥ 20 | T: 42.6 ± 13.6 | Both | U | T: 4,568; M: 1,882; F: 2,686 | WHO | Diabetes patients were excluded | T: 9.2 (8.3 - 10.0) |

| Zabetian et al. (51) | Tehran, (TLGS, phase 1), local study | Healthy adults | Multistage random cluster sampling | 1999 - 2001 | 2007 | ≥ 20 | T: 42.7 ± 15.0 ; M: 44.1 ± 15.6; F: 41.7 ± 14.4 | Both | U | T: 10,368 M: 4,397; F: 5,971 | IDF | T: 31 (30.1 - 31.8); M: 21 (19.7 - 22.2); F: 41 ; (39.7 - 42.2) | |

| Nabipour et al. (52) | Bushehr, Genaveh, and Deilam, local study | Healthy adults | Random Cluster sampling | 2003 - 2004 | 2007 | ≥ 25 | Both | Both | T: 3,723; M: 1,746; F: 1,977 | ATP III | T: 52.1 (47.3 - 50.6); M: 54.6 (50.3 - 53.6); F: 49.9 (44.5 - 48.5) | ||

| Sadrbafghi et al. (53) | Yazd, local study | Healthy adults | Random Cluster sampling | 2004 | 2006 | 20 - 74 | T:49 ± 18; M: 48.9 ± 15.4; F: 49.2 ± 21.4 | Both | U | T: 1,110; M: 550; F: 557 | ATP III | T: 32.1 (29.3 - 34.9); M: 37.8 (33.7 - 42.0); F: 62.2 (57.9 - 66.1) | |

| Fakhrzadeh et al. (54) | Tehran, local study | Healthy adults | Single-stage cluster sampling | 2003 | 2006 | 25 - 64 | T: 41.26 ± 12.06 | Both | U | T: 1,480; M: 571; F: 909 | ATP III | T: 29.9 (27.6 - 32.2); M: 20.3 (17.08 - 23.85); F: 35.9 (32.74 - 39.07) | |

| Azizi et al. (16) | Tehran, (TLGS, phase 1), local study | Healthy adults | Multistage, stratified random cluster sampling | 1999 - 2001 | 2003 | ≥ 20 | Both | U | T: 10,368; M: 4,397; F: 5,971 | ATP III | T: 33.7 (32.8 - 34.6); M: 24 (22.7 - 25.2); F: 42 (40.7 - 43.2) |

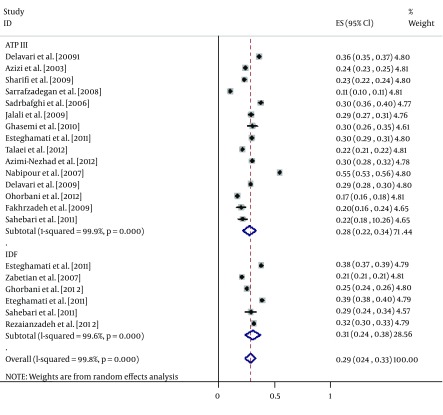

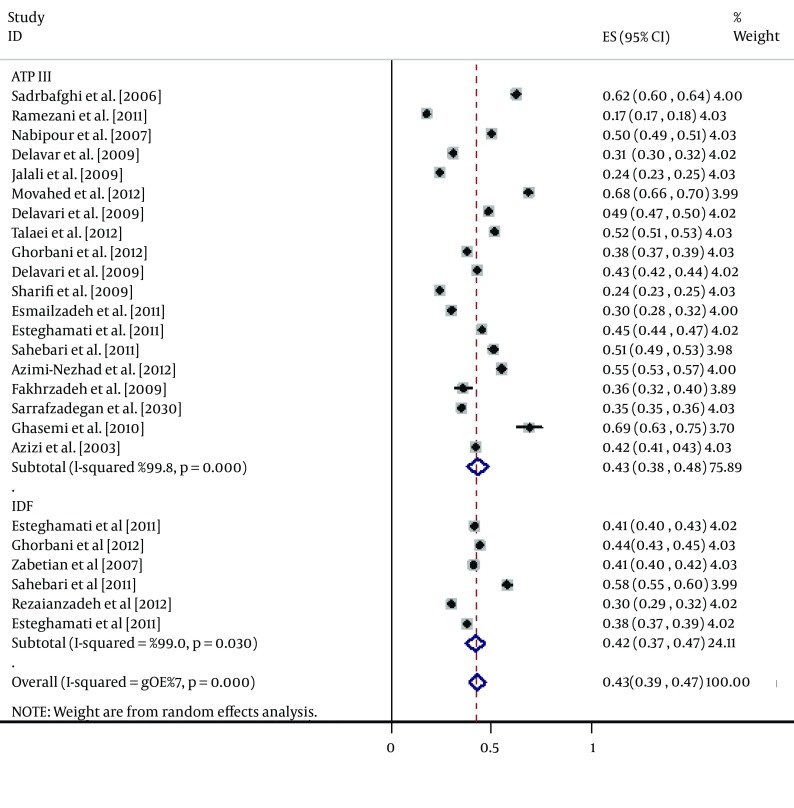

The total sample sizes of studies using the criteria of ATP III, IDF, and JIS were 54,043, 23,774, and 1,088, respectively (Table 2). For ATP III criteria, the maximum and minimum sample sizes were 12,514 (in Isfahan) and 137 (in Tehran), respectively. Maximum and minimum sample sizes for IDF were 10,368 and 486 (both in Tehran) and for JIS, they were 4,665 and 365 (both in Tehran), respectively. The overall estimation of MetS prevalence was 36.9% (95% CI: 32.7 - 41.2%) according to ATP III, 34.6% (95% CI: 31.7 - 37.6%) for IDF, and 41.5% (95% CI: 29.8 - 53.2%) based on the JIS criteria (Table 2 and Figure 2). The prevalence of MetS measured by JIS was higher than those measured by the ATP III and IDF definitions (41.5% versus 36.9% and 34.6%); however, this difference was not statistically significant. Maximum and minimum prevalence rates of MetS were 60% and 23% based on the ATP III criteria, 40% and 30% for the IDF criteria, and 52% and 31% for the JIS criteria, respectively (Figure 2).

Table 2. The Overall Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the Iranian Adult Population According to Different Criteria and Sex Using Random Effect Meta-Analysis of Data From Population-based Studies.

| Criteria | Extracted articles (n) | Sample size (n) | Prevalence (%) | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP III | ||||

| Male | 15 | 24,760 | 27.7 | 21.8 - 33.6 |

| Female | 19 | 32,046 | 43.1 | 37.9 - 48.4 |

| Total | 17 | 54,043 | 36.9 | 32.7 - 41.2 |

| Heterogeneity ATP III (I-square) | ||||

| Male | 99.9% | P < 0.001 | ||

| Female | 99.8% | P < 0.001 | ||

| Total | 99.8% | P < 0.001 | ||

| IDF | ||||

| Male | 6 | 9,874 | 30.7 | 23.9 - 37.5 |

| Female | 6 | 12,498 | 42.0 | 37.4 - 46.6 |

| Total | 7 | 23,774 | 34.6 | 31.7 - 37.6 |

| Heterogeneity IDF (I-square) | ||||

| Male | 99.6% | P < 0.001 | ||

| Female | 99% | P < 0.001 | ||

| Total | 98.9% | P < 0.001 | ||

| JIS | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1,856 | 45.7 | 44.6 - 46.8 |

| Female | 2 | 2,815 | 37.3 | 32.4 - 42.2 |

| Total | 4 | 10,385 | 41.5 | 29.8 - 53.2 |

| Heterogeneity JIS (I-square) | ||||

| Male | - | |||

| Female | 99.9% | P < 0.001 | ||

| Total | 99.8% | P < 0.001 |

Figure 2. Forest Plot of the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the Iranian Adult Population.

According to the ATP III criteria, the prevalence of MetS was significantly (15.4%) lower in men than in women (27.7% versus 43.1%, respectively). The same trend was obtained for the IDF definition, which found MetS to be 11.3% less prevalent in men than in women (30.7% versus 42.0%, respectively). However, the reverse was true for the JIS definition, which showed a significantly higher (8.4%) prevalence in men than in women (45.7% versus 37.3%, respectively) (Table 2, Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Forest Plot of the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the Iranian Male Adult Population.

Figure 4. Forest Plot of the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the Iranian Female Adult Population.

The results of the meta-regression show that the main source of heterogeneity in findings was the mean age of participants. The results show that by each year increase in the mean age of individuals after the age of 18, the prevalence of MetS increased by 0.004% (coefficient: 0.0048792, P = 0.005).

Nine studies reported the prevalence of MetS components according to different criteria (Table 3). Among these studies, in six the prevalence of components was calculated in subjects with MetS. Most of the subjects with MetS had three components (54.7% - 95%). The prevalences of four and five components in MetS subjects were 0.6 - 34% and 0 - 11.8%, respectively.

Table 3. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome Components in the Iranian Adult POPULATION in Population-Based Studiesa.

| Reference | Location and type of study | Study population | Sampling method | Study date | Publication date | Age range (years) | Mean age (mean ± SD) | Sex | Urban/rural | Sample size | Criteria | Prevalence of MetS components (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tohidi et al. (44) | Ghazvin, Kermanshah, Golestan, and Hormozgan, multicity study | Healthy adults | Multistage random cluster sampling | 2011 | 18 - 45 | F | U | T: 914 | Modified ATP III | 3 components: 11.4; 4 components: 5.1; 5 components: 1 | ||

| Fakhrzadeh et al. (54) | Isfahan (cohort study), local study | Healthy adults | Random stratified sampling | 2011 | 43 - 82 | 56.42 ± 9.52 | Both | Both | T: 468; M: 236; F: 232 | ATP III | 3 components: 55.2; 4 components: 34; 5 components: 10.8 | |

| Jalali et al. (46) | Akbar abad Koar Fars near Shiraz, local study | Healthy adults | Simple random sampling | 2008 (1387) | 2009 | 18 - 90 | T: 38.7 ± 14.3; M: 40.5 ± 15.9; F: 37.4 ± 13.7 | Both | R | T: 1,402; M: 360; F: 1,042 | ATP III; Modified ATP III; IDF | Total, 3 components: 95; 4 components : 0.6; 5 components: 4.5; male, 3 components: 99; 4 components: 0; 5 components:1; female, 3 components: 93.4; 4 components: 0.6; 5 components: 6. Total, 3 components: 66.3; 4 components: 27.1; 5 components: 6.7; male, 3 components: 71.4; 4 components: 26.1; 5 components: 2.5; female, 3 components: 64.1; 4 components: 27.5; 5 components: 8.4. Total, 3 components: 54.7; 4 components: 33.4; 5 components: 11.8; Male, 3 components: 38.4; 4 components: 44.8; 5 components: 16.8; Female, 3 components: 59; 4 components: 30.5; 5 components: 10.5 |

| Delavar et al. (47) | Babol, local study | Female adults | Systematic random sampling | 2009 | 30 - 50 | F: 40.2 ± 0.2 | F | U | T: 944 | ATP III | 1 component: 30.8; 2 components: 28.9; 3 components: 22.6; 4 components: 7.4; 5 components: 0.8 | |

| Sharifi et al. (48) | Zanjan, local study | Healthy adults | Stratified, multistage random sampling | 2002 - 2003 | 2009 | > 20 | Both | U | T: 2,941; M: 1,396; F: 1,545 | Modified ATP III | 3 components: 75.6; 4 components: 24.4; 5 components: 0 | |

| Nabipour et al. (52) | Bushehr, Genaveh, and Deilam, local study | Healthy adults | Random cluster sampling | 2003 - 2004 | 2007 | ≥ 25 | Both | Both | T: 3,723; M: 1,746; F: 1,977 | ATP III | 0 components: 4.0; 1 component: 15.1; 2 components: 28.7; 3 components: 30.8; 4 components: 17.7; 5 components: 3.6 | |

| Sadrbafghi et al. (53) | Yazd, local study | Healthy adults | Random cluster sampling | 2004 (1383) | 2006 | 20 - 74 | T: 49 ± 18; M: 48.9 ± 15.4; F: 49.2 ± 21.4 | Both | U | T: 1,110; M: 550; F: 557 | ATP III | 0 components: 19.2; 1 component: 21.1; 2 components: 27.6; 3 components: 20.8; 4 components: 9; 5 components: 2.3 |

| Fakhrzadeh et al. (54) | Tehran, local study | Healthy adults | Single stage cluster sampling | 2003 | 2006 | 25 - 64 | T: 41.26 ± 12.06 | Both | U | T: 1,480; M: 571; F: 909 | ATP III | 0 component: 12; 1 component: 29; 2 components: 29.1; 3 components: 22.7; 4 components: 7.1; 5 components: 0.2 |

| Azizi et al. (16) | Tehran, (TLGS, phase 1), local study | Healthy adults | Multistage stratified random cluster sampling | 1999 - 2001 | 2003 | ≥ 20 | Both | U | T:10,368; M: 4,397; F: 5,971 | ATP III | Total, 3 components: 58; 4 components: 33; 5 components: 9; Male, 1 component: 29; 2 components: 32; 3 components: 16; 4 components: 7; 5 components: 1; Female, 1 component: 28; 2 components: 23; 3 components: 20; 4 components: 14; 5 components: 4 |

aAbbreviations: F, female; M, male; T, total.

7. Conclusions

Our findings show that the prevalence of MetS is relatively high in Iran according to all three definitions (ATP III: 36.9%, IDF: 34.6%, and JIS: 41.5%). These observed prevalence rates are noticeably higher than the estimated prevalence around the world, which is between 20% and 25% (7). The mean prevalence of MetS in Iran was found to be higher than in many other countries (e.g., Portugal [27.6%], (55) Spain [26.6%], (56) France [25% in males and 15.3% in females], (57) and Italy [22% in males and 18% in females]) (3). It was also higher than in the United States of America (22.9%) (58). The prevalence of MetS in Iran is much closer to that in North Africa (30%), (59) Asia-China (33.9%), (60) Turkey (36.6%), (60) and some Latin American countries such as Colombia (34.8%) (61)and Venezuela (35.3%) (62). Therefore it can be assumed that some reasons other than urbanization and inactivity have resulted in this relatively high prevalence of MetS in Iran. In a study conducted by Delavari et al., greater waist circumference values and lower HDL cholesterol have also been reported in Iranian communities than in Western populations, which support the idea of an ethnic predisposition of the Iranian community to MetS (14).

It is noteworthy to acknowledge that comparisons between Iran and other countries must be made with caution. First, because most of these studies were conducted in a small area or a city, they cannot be representative of the entire country. Thus, generalizing the estimated prevalence to a country is a point of concern. Second, it has been shown that MetS is highly age-dependent (63). This was also found in our study; the prevalence of MetS in the Iranian population increased around 0.004% by each year of age increase after the age of 18. Therefore, even in a study with population-based sampling, comparing countries with different age pyramids might result in different prevalence rates, even with comparable risks of MetS. In recent years, the population of Iran has been growing older, and this might be one of the reasons for such a high prevalence of MetS in this country.

Another finding of this study was the significantly higher prevalence of MetS and its reverse sex distribution according to JIS compared to the other two definitions. According to the ATP III and IDF definitions, MetS prevalence was significantly higher in women (15.4% and 11.3% higher than the prevalence in men, respectively). However, based on the JIS criteria, MetS was 8.4% more prevalent in men, which was also significant. The lack of consensus on MetS definitions and the cutoff points used for its components, especially regarding waist circumference, has resulted in these differences. In the JIS definition, the cut-off point for waist circumference is usually higher than those of ATP III and IDF for women and lower for men, which may have resulted in a higher prevalence of MetS being measured in men according to the JIS definition, and contrary to the ATP III and IDF definitions. These differences influence health policies and clinical practice, in which underestimation or overestimation may result in inappropriate distribution of health services. Barbosa et al. performed a cross-sectional study on 1,439 adults in Brazil and concluded that NCEP-ATP III (64) underestimated the prevalence of MetS, particularly in men. This study showed that MetS is a public health problem in Iran. It has a high prevalence and it is expected to have an increasing trend in coming years as the mean age of the Iranian population grows. Therefore, by implementing an appropriate screening and treatment system, many metabolic diseases (such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease) that are costly to society can be prevented.

The main limitation of this study is that estimated prevalences were not adjusted based on the size of the target populations. Regarding this point, the results of a cluster analysis method are much more reliable, but cluster sampling is not practical because it is very difficult and expensive to perform. It seems that meta-analysis could be an efficient substitute strategy.

The prevalence of MetS is relatively high in the Iranian adult population. The lack of consensus on MetS definitions has resulted in different reports of its prevalence. However, even considering the lowest prevalence of 34.6%, the prevalence of MetS in Iran is considerably higher than the estimated prevalence around the world (20 - 25%). Therefore, applying an appropriate screening and treatment system for MetS could prevent many chronic diseases that are costly to society.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Study concept and design: Mostafa Qorbani, Hossein Fakhrzadeh; acquisition of data: Bahareh Amirkalali, Tahereh Samavat; analysis and interpretation of data: Mostafa Qorbani, Bahareh Amirkalali; drafting of the manuscript: Bahareh Amirkalali; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Roya Kelishadi, Farhad Zamani, Farshad Sharifi and Saeid Safiri; statistical analysis: Mostafa Qorbani; administrative, technical, and material support: Hossein Fakhrzadeh, Hamid Asayesh; study supervision: Hossein Fakhrzadeh.

Funding/Support:This study was supported by the Endocrinology and Metabolism Population Sciences Institute at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Reaven GM. Banting Lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. 1988. Nutrition. 1997;13(1):65. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(96)00380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, Erwin PJ, Gami LA, Somers VK, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(4):403–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giampaoli S, Stamler J, Donfrancesco C, Panico S, Vanuzzo D, Cesana G, et al. The metabolic syndrome: a critical appraisal based on the CUORE epidemiologic study. Prev Med. 2009;48(6):525–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scuteri A, Najjar SS, Morrell CH, Lakatta EG, Cardiovascular Health S. The metabolic syndrome in older individuals: prevalence and prediction of cardiovascular events: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(4):882–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeill AM, Rosamond WD, Girman CJ, Golden SH, Schmidt MI, East HE, et al. The metabolic syndrome and 11-year risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(2):385–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sociedade Brasileira de H, Sociedade Brasileira de C, Sociedade Brasileira de Endocrinologia e M, Sociedade Brasileira de D, Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos da O. [I Brazilian guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of metabolic syndrome]. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2005;84 Suppl 1:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International diabetes federation tIcwadotms. Available from: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/IDF_Meta_def_final.pdf.

- 8.Salaroli LB, Barbosa GC, Mill JG, Molina MC. [Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in population-based study, Vitoria, ES-Brazil]. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;51(7):1143–52. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302007000700018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topic Pmbvb E, editor. New trends in classification, monitoring and management of metabolic syndrome.; The 6th FESCC Continuous Postgraduate Course in Clinical Chemistry.; 2006; [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Pyorala K. Assessment of coronary heart disease risk in populations with different levels of risk. Eur Heart J. 2000;21(5):348–50. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287(3):356–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bender R, Jockel KH, Richter B, Spraul M, Berger M. Body weight, blood pressure, and mortality in a cohort of obese patients. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(3):239–45. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(4):629–36. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delavari A, Forouzanfar MH, Alikhani S, Sharifian A, Kelishadi R. First nationwide study of the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and optimal cutoff points of waist circumference in the Middle East: the national survey of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases of Iran. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1092–7. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelishadi R, Ardalan G, Gheiratmand R, Adeli K, Delavari A, Majdzadeh R, et al. Paediatric metabolic syndrome and associated anthropometric indices: the CASPIAN Study. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(12):1625–34. doi: 10.1080/08035250600750072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azizi F, Salehi P, Etemadi A, Zahedi-Asl S. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an urban population: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;61(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(03)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derakhshan Davari R, Khoshnood A. Evaluation of abdominal obesity prevalence in diabetic patients and relationships with metabolic syndrome factors. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2010;2010(3, Summer):143–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saki F, Karamizadeh Z. Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and Fatty liver in obese Iranian children. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(5):e24723. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.6656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khoshdel A, Jafari SMS, Heydari ST, Abtahi F, Ardekani AA, Lak FJ. The prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors, and metabolic syndrome among iranian military parachutists. Int Cardivas Res J. 2012;6(2):51–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iravani SH, Sabayan B, Sedaghat S, Heydari ST, Javad P, Lankarani KB, et al. The association of elevated serum alanine aminotransferase with metabolic syndrome in a military population in southern iran. Int Cardivas Res J. 2010;30(108):74–80. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paknahad Z, Ahmadi Vasmehjani A, Maracy MR. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels with markers of metabolic syndrome in adult women in Ramsar, Iran. Women Health. 2014;1(1):e24723 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabatabaei-Malazy O, Fakhrzadeh H, Sharifi F, Mirarefin M, Badamchizadeh Z, Larijani B. Gender differences in association between metabolic syndrome and carotid intima media thickness. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2012;11(1):13. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amirkalali B, Poustchi H, Keyvani H, Khansari MR, Ajdarkosh H, Maadi M, et al. Prevalence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Its Predictors in North of Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(9):1275–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. [The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology [STROBE] statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies]. Gac Sanit. 2008;22(2):144–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman DS, Hulley SB, Clark LT, Davis CE, Fuster V, LaRosa JC, et al. Report of the national cholesterol education program expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148(1):36–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(3):720–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esteghamati A, Zandieh A, Zandieh B, Khalilzadeh O, Meysamie A, Nakhjavani M, et al. Leptin cut-off values for determination of metabolic syndrome: third national surveillance of risk factors of non-communicable diseases in Iran (SuRFNCD-2007). Endocrine. 2011;40(1):117–23. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Definition WHO, editor. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: Report of a WHO consultation.; 1999; Geneva. World Health Organization; [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faam B, Hosseinpanah F, Amouzegar A, Ghanbarian A, Asghari G, Azizi F. Leisure-time physical activity and its association with metabolic risk factors in Iranian adults: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study, 2005-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E36. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ziaee A, Esmailzadehha N, Ghorbani A, Asefzadeh S. Association between Uric Acid and Metabolic Syndrome in Qazvin Metabolic Diseases Study (QMDS), Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5(1):155–65. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n1p155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Movahed A, Larijani B, Nabipour I, Kalantarhormozi M, Asadipooya K, Vahdat K, et al. Reduced serum osteocalcin concentrations are associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus and the metabolic syndrome components in postmenopausal women: the crosstalk between bone and energy metabolism. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30(6):683–91. doi: 10.1007/s00774-012-0367-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yousefzadeh G, Shokoohi M, Yeganeh M, Najafipour H. Role of gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) in diagnosis of impaired glucose tolerance and metabolic syndrome: a prospective cohort research from the Kerman Coronary Artery Disease Risk Study (KERCADRS). Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2012;6(4):190–4. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azimi-Nezhad M, Herbeth B, Siest G, Dade S, Ndiaye NC, Esmaily H, et al. High prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Iran in comparison with France: what are the components that explain this? Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2012;10(3):181–8. doi: 10.1089/met.2011.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hadaegh F, Zabetian A, Khalili D, Safarkhani M, James WPT, Azizi F. A new approach to compare the predictive power of metabolic syndrome defined by a joint interim statement versus its components for incident cardiovascular disease in Middle East Caucasian residents in Tehran. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(5):427–32. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.117697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talaei M, Thomas GN, Marshall T, Sadeghi M, Iranipour R, Oveisgharan S, et al. Appropriate cut-off values of waist circumference to predict cardiovascular outcomes: 7-year follow-up in an iranian population. Int Med. 2012;51(2):139–46. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarkesh M, Faam B, Daneshpour MS, Azizi F, Hedayati M. The relationship between metabolic syndrome, cardiometabolic risk factors and inflammatory markers in a tehranian population: The tehran lipid and glucose study. Inte. Med. 2012;51(24):3329–35. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.8475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghorbani R, Naeini BA, Eskandarian R, Rashidy-Pour A, Khamseh ME, Malek M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome according to ATPIII and IDF criteria in the Iranian population. Koomesh. 2012;14(1):Pe65–75. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rezaianzadeh A, Namayandeh SM, Sadr SM. National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Versus International Diabetic Federation Definition of Metabolic Syndrome, Which One is Associated with Diabetes Mellitus and Coronary Artery Disease? Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(8):552–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hosseinpanah F, Barzin M, Tehrani FR, Azizi F. The lack of association between polycystic ovary syndrome and metabolic syndrome: Iranian PCOS prevalence study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;75(5):692–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahebari M, Goshayeshi L, Mirfeizi Z, Rezaieyazdi Z, Hatef MR, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, et al. Investigation of the association between metabolic syndrome and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:1195–205. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L. Dietary energy density and the metabolic syndrome among Iranian women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(5):598–605. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esteghamati A, Noshad S, Khalilzadeh O, Morteza A, Nazeri A, Meysamie A, et al. Contribution of serum leptin to metabolic syndrome in obese and nonobese subjects. Arch Med Res. 2011;42(3):244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tohidi M, Rostami M, Asgari S, Azizi F. The association between sub-clinical hypothyroidism and metabolic syndrome: A population based study. Iran J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;13(1):98–105. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghasemi A, Zahediasl S, Syedmoradi L, Azizi F. Low serum magnesium levels in elderly subjects with metabolic syndrome. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2010;136(1):18–25. doi: 10.1007/s12011-009-8522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jalali R, Vasheghani M, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Ranjbar Omrani GH. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults in a rural area. Iran JEndocrinol Metab. 2009;11(4):405–14. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delavar MA, Lye MS, Khor GL, Hanachi P, Hassan ST. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among middle aged women in Babol, Iran. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40(3):612–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharifi F, Mousavinasab SN, Saeini M, Dinmohammadi M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an adult urban population of the west of Iran. Exp Diabetes Res. 2009;2009:136501. doi: 10.1155/2009/136501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarrafzadegan N, Kelishadi R, Baghaei A, Hussein Sadri G, Malekafzali H, Mohammadifard N, et al. Metabolic syndrome: an emerging public health problem in Iranian women: Isfahan Healthy Heart Program. Int J Cardiol. 2008;131(1):90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hadaegh F, Ghasemi A, Padyab M, Tohidi M, Azizi F. The metabolic syndrome and incident diabetes: Assessment of alternative definitions of the metabolic syndrome in an Iranian urban population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;80(2):328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zabetian A, Hadaegh F, Azizi F. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Iranian adult population, concordance between the IDF with the ATPIII and the WHO definitions. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77(2):251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nabipour I, Amiri M, Imami SR, Jahfari SM, Shafeiae E, Nosrati A, et al. The metabolic syndrome and nonfatal ischemic heart disease; a population-based study. Int J Cardiol. 2007;118(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sadrbafoghi SM, Salari M, Rafiee M, Namayandeh SM, Abdoli AM, Karimi M. Prevalence and criteria of metabolic syndrome in an urban population: Yazd healthy heart project. Tehran Uni Med J. 2006;64(10):90–6. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fakhrzadeh H, Ebrahimpour P, Pourebrahim R, Heshmat R, Larijani B. Metabolic Syndrome and its Associated Risk Factors in Healthy Adults: APopulation-Based Study in Iran. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2006;4(1):28–34. doi: 10.1089/met.2006.4.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fonseca MJ, Gaio R, Lopes C, Santos AC. Association between dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in a sample of Portuguese adults. Nutr J. 2012;11:64. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corbaton-Anchuelo A, Martinez-Larrad MT, Fernandez-Perez C, Vega-Quiroga S, Ibarra-Rueda JM, Serrano-Rios M, et al. Metabolic syndrome, adiponectin, and cardiovascular risk in Spain (the Segovia study): impact of consensus societies criteria. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11(5):309–18. doi: 10.1089/met.2012.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wagner A, Dallongeville J, Haas B, Ruidavets JB, Amouyel P, Ferrieres J, et al. Sedentary behaviour, physical activity and dietary patterns are independently associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab. 2012;38(5):428–35. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beltran-Sanchez H, Harhay MO, Harhay MM, McElligott S. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome in the adult U.S. population, 1999-2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(8):697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belfki H, Ben Ali S, Aounallah-Skhiri H, Traissac P, Bougatef S, Maire B, et al. Prevalence and determinants of the metabolic syndrome among Tunisian adults: results of the Transition and Health Impact in North Africa (TAHINA) project. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(4):582–90. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang GR, Li L, Pan YH, Tian GD, Lin WL, Li Z, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among urban community residents in China. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:599. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pinzon JB, Serrano NC, Diaz LA, Mantilla G, Velasco HM, Martinez LX, et al. [Impact of the new definitions in the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in an adult population at Bucaramanga, Colombia]. Biomedica. 2007;27(2):172–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Florez H, Silva E, Fernandez V, Ryder E, Sulbaran T, Campos G, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome and dyslipidemia in White, Black, Amerindian and Mixed Hispanics in Zulia State, Venezuela. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69(1):63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park YW, Zhu S, Palaniappan L, Heshka S, Carnethon MR, Heymsfield SB. The metabolic syndrome: prevalence and associated risk factor findings in the US population from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(4):427–36. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barbosa PJ, Lessa I, de Almeida Filho N, Magalhaes LB, Araujo J. Criteria for central obesity in a Brazilian population: impact on metabolic syndrome. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2006;87(4):407–14. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2006001700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]