Abstract

Background

Previous studies on the relation of chronic bronchitis to incident airflow limitation and all-cause mortality have provided conflicting results, with positive findings reported mainly by studies that included populations of young adults. We sought to determine whether having chronic cough and sputum production in the absence of airflow limitation is associated with onset of airflow limitation, all-cause mortality, and serum levels of CRP and IL-8, and whether subjects’ age influences these relations.

Methods

We identified 1412 participants in the long-term Tucson Epidemiological Study of Airway Obstructive Disease who at enrollment (1972–73) were 21–80 years old and had FEV1/FVC≥70% and no asthma. Chronic bronchitis was defined as cough and phlegm production on most days for ≥three months in ≥two consecutive years. Incidence of airflow limitation was defined as the first follow-up survey with FEV1/FVC<70%. Serum IL-8 and CRP levels were measured in cryopreserved samples from the enrollment survey.

Results

After adjusting for covariates, chronic bronchitis at enrollment increased significantly the risk for incident airflow limitation and all-cause mortality among subjects <50 years old (Hazard Ratios, 95% CI: 2.2, 1.3–3.8; and 2.2, 1.3–3.8; respectively), but not among subjects ≥50 years old (0.9, 0.6–1.4; and 1.0, 0.7–1.3). Chronic bronchitis was associated with increased IL-8 and CRP serum levels only among subjects <50 years old.

Conclusions

Among adults <50 years old, chronic bronchitis unaccompanied by airflow limitation may represent an early marker of susceptibility to the effects of cigarette smoking on systemic inflammation and long-term risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and all-cause mortality.

Keywords: All-cause mortality, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CRP

Introduction

Chronic bronchitis (i.e., chronic cough and sputum production) is a common clinical feature associated with cigarette smoking and it can precede by years the development of any spirometric abnormalities indicative of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among smokers. Whether mucus hypersecretion has independent effects on predisposing to chronic airflow limitation has been long debated(1) and recent studies have indeed provided conflicting results on the subject. In the Copenhagen City Heart Study, participants who had productive cough were found to have a non-significant increase in their risk of incident airflow limitation over a 15 year follow-up, although their FEV1 decline was on average 23 ml per year steeper than that of subjects with no chronic bronchitis(2). In that study, the mean age of subjects with no COPD at baseline was 52 years. In contrast, in the younger cohort of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) conducted among adults 20 to 44 years old at enrollment, subjects who reported chronic cough and/or phlegm at baseline had a more than two-fold increased risk of developing incident airflow limitation over the 9 years follow-up, as compared with subjects with no chronic cough and phlegm(3). This association was confirmed after adjustment for multiple covariates. In a third study from Sweden, the presence of chronic productive cough was found to be associated with a significant 46% increase in the risk of incident airflow limitation over 10 years of follow-up in an adult population that included three cohorts of subjects who were 36–37, 51–52, and 66–67 years old at enrollment(4). Results were reported for the three cohorts combined and it was not possible to determine whether these associations were different across different age groups.

In addition to COPD risk, chronic bronchitis may also increase all-cause mortality risk. However, much like for the case of the association between chronic bronchitis and incident COPD, studies have produced inconsistent findings also on the effects of chronic bronchitis on all-cause mortality(5–11), with the strongest links reported by studies that included younger study populations.

Taken together, these observations suggest that conflicting evidence emerging from previous studies on clinical outcomes of chronic bronchitis may be partly explained by differences in the age distributions of the subjects studied(12), with the impact of chronic bronchitis on both incident airflow limitation and mortality being stronger among young as compared with older adults.

The exact mechanisms by which chronic cough and phlegm production may affect incidence of COPD and mortality risk remain largely unknown. Phlegm hypersecretion has been long associated with airway inflammation(13). There is now convincing evidence that in COPD airway inflammation may extend beyond the lung to systemic inflammation(14–20), which, in turn, has been implicated in the systemic manifestations and excess mortality risk of this disease(21). In this framework, it is reasonable to hypothesize that chronic bronchitis represents an early marker of susceptibility to both the pro-inflammatory effects and the long-term health consequences of cigarette smoking and, thus, that the same factors that influence inflammatory response in subjects with chronic bronchitis will, in turn, affect also the risk for incident COPD and mortality associated with this phenotype.

In the current study, we sought to determine whether having chronic cough and sputum production is associated with subsequent incidence of airflow limitation, risk for all-cause mortality, and increased serum levels of Interleukin 8 and C-reactive protein. We also sought to determine whether these associations differed significantly between adults < 50 and ≥ 50 years old.

Methods

Study population and definition of exposure at the enrollment survey

The Tucson Epidemiological Study of Airway Obstructive Disease (TESAOD) is a population-based prospective cohort study initiated in Tucson, AZ in 1972. Details of the enrollment process have been previously reported(22). At the enrollment survey, 2754 white participants (age range: 6 to 95 years) completed both a standardized respiratory questionnaire and spirometric lung function tests with a pneumotachygraphic device. Twelve additional follow-up surveys were completed approximately every two years between 1974 and 1996, in which participants completed questionnaires and, with the exception of survey 4, performed follow-up spirometric lung function tests. Protocols for lung function testing were consistent across surveys and ATS guidelines were integrated into the protocols after their publication in 1979(23). Methods used to perform lung function tests before 1979 are described elsewhere(24).

For the present study, we used data from participants who at the enrollment survey in 1972–73: 1) were 21 to 80 years old (2135 of the total 2754 subjects, 78%); 2) did not report a physician-confirmed diagnosis of asthma (1893 of the remaining 2135 subjects, 89%); 3) did not report having ever had lung/chest surgery (1852/1893, 98%); 4) were not pregnant (1831/1852, 99%); 5) had an FEV1/FVC ratio ≥ 70% (1599/1831, 87%). In addition, to be included in the present study subjects also had to have at least one lung function follow-up test (1412 of the remaining 1599 subjects, 88%).

Participants were considered to have chronic bronchitis at enrollment if they reported cough and sputum production on most days for at least 3 months in at least two consecutive years. Chronic cough was defined as a cough meeting the above temporal criteria regardless of the presence of accompanying phlegm production.

Pack-years at enrollment were computed for each participant based on responses to a series of smoking questions. We categorized subjects as ever smokers if they had at least 1 pack-year at the enrollment survey.

Skin prick tests, serum IgE measurements (PRIST method), and blood eosinophil counts were also performed at the enrollment survey (see Online Repository).

Assessment of outcomes

Incident airflow limitation was defined as an FEV1/FVC ratio < 70% in any of the follow-up surveys. Because the FEV1/FVC ratio declines significantly with aging, sensitivity analyses were also repeated after defining incident airflow limitation as the first survey with an FEV1/FVC ratio below the sex- and age-specific lower limit of normal(25).

Vital status of TESAOD participants as of January 2005 was determined through direct contact with the family or designated next of kin of the participant, linkage with the Social Security Death Index(26), and – for deaths that occurred after 1978 – linkage with the National Death Index, which has been shown to be a reliable and specific means of establishing vital status of study participants(27).

Molecular assays

We measured levels of Interleukin 8 (IL-8) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in cryopreserved serum samples that were collected during the enrollment survey. IL-8 levels were measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (HyCult Biotechnology b.v., Cell Sciences Inc, Norwood, MA). CRP levels were measured with the enzymatic solid-phase chemiluminescent immunometric assay supported by Immulite 2000 (Siemens Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY).

Statistical analyses

Standard parametric tests and χ2 tests were used to compare baseline characteristics of subjects with and without chronic bronchitis. IgE and CRP values were log-transformed to achieve normalization. Because IL-8 levels were undetectable (i.e., < 4.09 pg/ml) in 14% of the analyzed serum samples, they were categorized into quartiles. Elevated IL-8 levels were defined as IL-8 levels above median (top two quartiles). The relation of chronic bronchitis to IL-8 and CRP levels was also tested after adjustment for covariates in multiple logistic regression and multiple linear regression models, respectively.

The relation of chronic bronchitis to incident airflow limitation and to all-cause mortality was investigated in Cox proportional hazards models. In analyses on incident airflow limitation, the end date was the first survey with an FEV1/FVC ratio < 70% for incident cases and the last survey with completed spirometry for subjects who did not develop airflow limitation. In mortality analyses, the end date was the date of death for deceased subjects and January 1st, 2005 for subjects who were still alive as of that date. In Cox models, effect modification by smoking and age was tested by including interaction terms between chronic bronchitis and smoking (ever smoked ≥ 1 pack-year versus never smoked 1 pack-year) and between chronic bronchitis and age (< 50 years versus ≥ 50 years). The age cut-off of 50 years was selected because it was the median age of the study population.

For illustrative purposes, Kaplan-Meier survival curves for incident airflow limitation and all-cause mortality were produced for “combinatorial groups” that were generated based on 1) the combination of smoking status and chronic bronchitis at enrollment, and 2) the combination of age and chronic bronchitis at enrollment.

Additional details on the study methods are provided in an online data repository.

Results

Comparison of TESAOD participants included and excluded from the present study

Among the 1599 TESAOD participants who, at enrollment, met the inclusion criteria for the present analyses, 1412 (88%) had at least one follow-up lung function test and were included in the present study, whereas 187 (12%) did not and were excluded from all subsequent analyses. The only significant difference between subjects included and excluded from the present study was that, as compared with the latter, those included were more likely to have more than 12 years of formal education (45% versus 35% respectively, p = 0.008). The two groups were comparable for all other demographic and clinical factors, supporting the representative nature of the study population.

Comparison of subjects with and without chronic bronchitis at enrollment

Of the 1412 subjects included in the present study, 97 (6.9%) reported chronic bronchitis at the enrollment survey. As compared with subjects with no chronic bronchitis, participants with chronic bronchitis were more likely to be males and smokers, had fewer years of formal education and slightly lower FEV1/FVC ratio at enrollment (Table I). No significant differences between the two groups were found in terms of age, BMI, skin tests, total IgE levels, or eosinophilia.

Table I.

Characteristics of TESAOD participants with and without chronic bronchitis at enrollment. N is 1412 unless otherwise specified.

| Participants with chronic bronchitis at enrollment (N = 97) | Participants without chronic bronchitis at enrollment (N = 1315) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex: % male | 51.5 | 40.8 | 0.04 |

| Age in years: mean ± SD | 50 ± 14 | 49 ± 18 | 0.54 |

| Body Mass Index (n = 1363): mean ± SD | 25.0 ± 4.8 | 24.4 ± 3.7 | 0.13 |

| Years of formal education: % with more than 12 years | 26.8 | 46.8 | <0.001 |

| Pack-Years (n = 1411): | |||

| % < 1 pack-year | 15.5 | 50.5 | |

| % 1–19.9 pack-years | 27.8 | 27.4 | <0.001 |

| % 20–49.9 pack-years | 42.3 | 16.4 | |

| % ≥ 50 pack-years | 14.4 | 5.7 | |

| Allergy skin tests ** (n = 1393): % positive | 31.2 | 35.7 | 0.38 |

| Total IgE in IU/ml (n = 1284): geometric mean (95% CI) | 28 (20 – 38) | 23 (21 – 25) | 0.31 |

| Eosinophilia ^ (n = 1067): % positive | 12.5 | 6.8 | 0.07 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio: mean ± SD | 81.3 ± 6 | 83.0 ± 7 | 0.02 |

P value for the comparison between the two groups.

Wheal at least two mm larger than the control wheal for at least one of five tested allergens (house dust; Bermuda grass; tree mix; weed mix; and Dematiaceae mold mix)

Eosinophils were measured as percentages from stained blood smears and blood eosinophilia was defined as eosinophils > 4%.

Effects of chronic bronchitis on incident airflow limitation

Participants with and without chronic bronchitis at enrollment completed on average a similar number of lung function tests during the study follow-up (mean number of tests, SD: 6.2, 3 versus 6.4, 3; p = 0.48). During follow-up, 42% (41/97) of subjects with chronic bronchitis developed airflow limitation versus 23% (304/1315) of subjects with no chronic bronchitis (p < 0.001). The relation of chronic bronchitis to the risk of developing incident airflow limitation was further investigated in Cox proportional hazards models (Table II). In univariate analyses, participants with chronic bronchitis had a significant 94% increased risk for developing airflow limitation (95% CI: 40%–169%). However, after adjusting for age and the other covariates that were found to be significantly associated with chronic bronchitis in Table I (i.e., sex, education, packyears, and the FEV1/FVC ratio at enrollment), this association became marginal (hazard ratio from multivariate model 1: 1.37, 0.98–1.92). An interaction term between chronic bronchitis and ever smoking was tested and found non-significant, although the adjusted HR for the increased risk of airflow limitation associated with chronic bronchitis tended to be higher among smokers (1.50, 1.05–2.13) than never smokers (0.86, 0.27–2.72) (data not shown in the Table). In contrast, we found a significant interaction between chronic bronchitis and age (model 2 in the Table), with the adjusted HR associated with chronic bronchitis being significantly higher among subjects < 50 years of age (2.24, 1.33–3.76) than among subjects ≥ 50 years of age (0.92, 0.59–1.43; data computed with linear contrasts and not shown in the Table). Inclusion of usual number of cigarettes per day as an additional covariate in the model left results unchanged. These results thus indicate that chronic bronchitis increases by more than 2-fold the risk of developing airflow limitation among adults < 50 years, whereas it is associated with no increased risk among older adults.

Table II.

Cox Proportional Hazards models predicting incident airflow limitation. All predictors were measured at the enrollment survey (1972–73). N is 1410 because two subjects had missing information.

| UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS | MULTIVARIATE Model 1 | MULTIVARIATE Model 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR* | 95% CI | P | HR* | 95% CI | P | HR* | 95% CI | P | |

| Sex: male | 1.36 | (1.10 – 1.68) | 0.004 | 1.16 | (0.92 – 1.45) | 0.20 | 1.12 | (0.89 – 1.40) | 0.32 |

| Age in years | 1.04 | (1.03 – 1.04) | <0.001 | 1.03 | (1.02 – 1.04) | <0.001 | |||

| Formal Education: > 12 years | 0.58 | (0.46 – 0.72) | <0.001 | 0.85 | (0.68 – 1.07) | 0.17 | 0.82 | (0.65 – 1.03) | 0.09 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio in % | 0.88 | (0.86 – 0.89) | <0.001 | 0.89 | (0.88 – 0.91) | <0.001 | 0.89 | (0.87 – 0.91) | <0.001 |

| Packyears | |||||||||

| < 1 pack-year | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| 1–19.9 pack-years | 1.19 | (0.90 – 1.59) | 0.22 | 1.50 | (1.12 – 2.01) | 0.007 | 1.31 | (0.98 – 1.76) | 0.07 |

| 20–49.9 pack-years | 2.79 | (2.14 – 3.64) | <0.001 | 1.75 | (1.32 – 2.32) | <0.001 | 1.73 | (1.30 – 2.29) | <0.001 |

| ≥ 50 pack-years | 3.78 | (2.64 – 5.40) | <0.001 | 2.28 | (1.57 – 3.32) | <0.001 | 2.22 | (1.52 – 3.24) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 1.94 | (1.40 – 2.69) | <0.001 | 1.37 | (0.98 – 1.92) | 0.07 | 2.24‡ | (1.33 – 3.76) | 0.002 |

| Categorical Age: ≥ 50 years | 2.22 | (1.71 – 2.89) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Interaction Term: Chronic Bronchitis * Age ≥ 50 years | 0.41 | (0.21 – 0.80) | 0.009 | ||||||

Hazard Ratios

This Hazard Ratio represents the increase in risk associated with chronic bronchitis among subjects < 50 years old

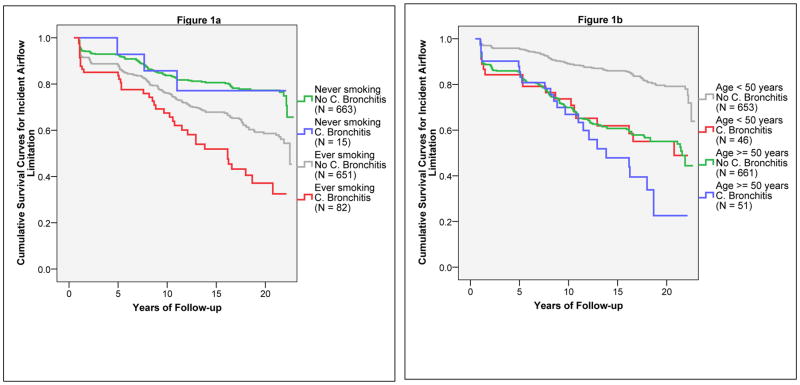

Participants were also divided into subgroups based on 1) the combination of smoking status (ever smoked ≥ 1 pack-year versus never smoked 1 pack-year) and chronic bronchitis at enrollment; and 2) the combination of age (< 50 years versus ≥ 50 years) and chronic bronchitis at enrollment. As shown in Figure 1, the effects of chronic bronchitis on incident airflow limitation were strong among smokers (Figure 1a) and subjects < 50 years old (Figure 1b), whereas no effects were found among never smokers and subjects ≥ 50 years old.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for incident airflow limitation. Figure 1a shows survival curves for the four groups generated by the combination of smoking status (ever smoked at least one pack-year versus never smoked one pack-year) and chronic bronchitis at enrollment. Figure 1b shows survival curves for the four groups generated by the combination of age (< 50 years versus ≥ 50 years) and chronic bronchitis at enrollment.

Because the FEV1/FVC ratio declines significantly with aging, the effect modification by age on the association between chronic bronchitis and incident airflow limitation could be due to the different sensitivity and specificity of a fixed FEV1/FVC ratio < 70% in identifying true COPD cases among younger as compared to older adults. To rule out this possibility, we repeated Cox models and confirmed the main findings after defining incident airflow limitation as the first survey with an FEV1/FVC ratio below the lower limit of normal(25). In these sensitivity analyses, the adjusted HRs for chronic bronchitis were 1.58 (1.05–2.39) in the total population, 2.34 (1.37–4.00) among subjects < 50 years old, and 1.13 (0.61–2.09) among subjects ≥ 50 years old. The p value associated with the interaction term between chronic bronchitis and age was 0.08.

In the online repository, results are also presented from sensitivity analyses 1) adding to the study population the 145 subjects with physician-confirmed diagnosis of asthma at enrollment (30 of whom with chronic bronchitis at enrollment) who were excluded from the main analyses (Table E1 and Figure E1) and 2) using chronic cough (N of cases = 162) instead of chronic bronchitis as the main predictor (Table E2 and Figure E2). In all cases, both the association of chronic bronchitis/chronic cough with incident airflow limitation and their interaction with age were confirmed.

Effects of chronic bronchitis on mortality risk

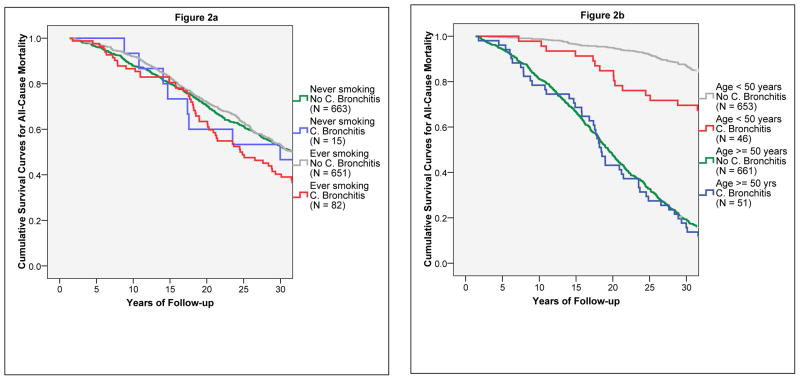

As of January 2005, 63% of the subjects who had chronic bronchitis at enrollment had died as compared with 50% of the subjects with no chronic bronchitis (p = 0.02), despite the similar age distribution of the two groups at enrollment. In Cox models, after adjusting for sex, age, education, packyears, and FEV1/FVC ratio at enrollment, the presence of chronic bronchitis was still associated with a significant 31% increased risk of all-cause mortality (adjHR: 1.31, 1.00–1.71). Much like for incident airflow limitation, the risk for all-cause mortality associated with chronic bronchitis was stronger among smokers (adjHR: 1.50, 1.12–2.01) than non-smokers (0.80, 0.40–1.62), and among subjects < 50 years of age (2.22, 1.30–3.79) than among subjects ≥ 50 years of age (0.96, 0.70–1.31). When tested in Cox models, the interaction term between chronic bronchitis and smoking was borderline significant (p = 0.10), whereas the interaction term between chronic bronchitis and age was highly significant (p = 0.007) and remained significant (p = 0.005) after inclusion of usual number of cigarettes per day as an additional covariate in the model. Figure 2 shows the survival curves for the combinatorial groups, which confirmed that chronic bronchitis had effects on all-cause mortality among subjects < 50 years old, but not among subjects ≥ 50 years old. Replacing the FEV1/FVC ratio with FEV1 percent predicted in Cox models produced similar results.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all-cause mortality. Figure 2a shows survival curves for the four groups generated by the combination of smoking status (ever smoked at least one pack-year versus never smoked one pack-year) and chronic bronchitis at enrollment. Figure 2b shows survival curves for the four groups generated by the combination of age (< 50 years versus ≥ 50 years) and chronic bronchitis at enrollment.

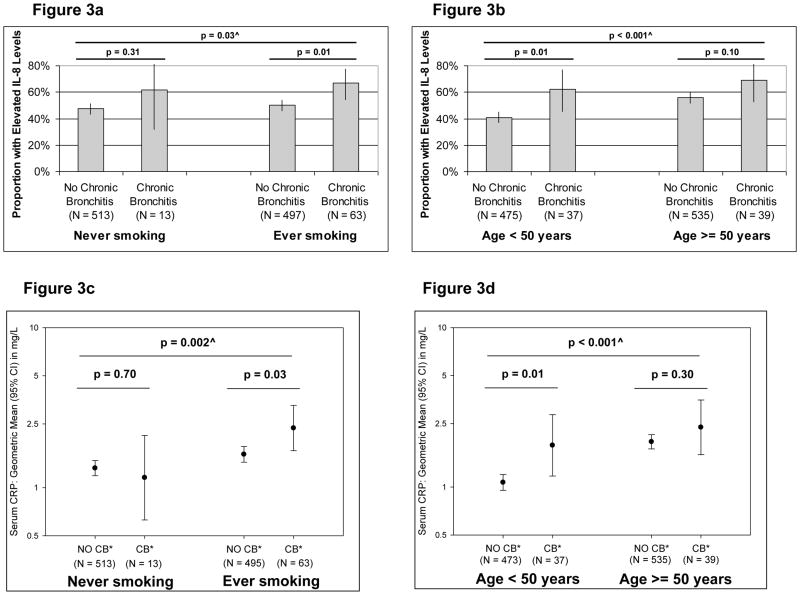

Chronic bronchitis and serum levels of IL-8 and CRP

Cryopreserved serum samples from the enrollment survey were available for 1087 of the 1412 subjects (77%) included in the present study. The distribution by IL-8 quartiles differed significantly between subjects with and without chronic bronchitis (p = 0.02), with 66% of subjects with chronic bronchitis having elevated serum IL-8 levels (i.e., above median) versus 49% of subjects with no chronic bronchitis. After adjusting for sex, age, education, packyears, and the FEV1/FVC ratio at enrollment, having chronic bronchitis remained associated with increased odds of having elevated IL-8 levels (adjOR: 1.88, 1.13–3.12). Similarly, serum CRP levels were higher among subjects with chronic bronchitis than subjects with no chronic bronchitis (geometric means: 2.09 versus 1.46 mg/L, respectively; p = 0.02), although this association was no longer significant after adjusting for covariates (p = 0.2).

In Figure 3, the proportion of subjects with elevated IL-8 levels and the geometric means (with 95% CIs) of CRP levels are shown for each of the combinatorial groups. Consistent with the associations of chronic bronchitis with both incident airflow limitation and mortality risk, levels for both markers were significantly associated with chronic bronchitis among smokers and adults < 50 years, but not among never smokers and adults ≥ 50 years of age.

Figure 3.

Proportion (and 95% CIs) of subjects with elevated IL-8 levels – defined as IL-8 levels above median – (Figures 3a and 3b) and geometric means (and 95% CIs) of serum CRP levels (Figures 3c and 3d) in each of the combinatorial groups generated by the combination of smoking status and chronic bronchitis, and by the combination of age and chronic bronchitis.

* CB = Chronic Bronchitis.

^ P value refers to the statistical comparison across the four groups

Discussion

In this study we found that chronic bronchitis was an independent risk factor for incident airflow limitation and all-cause mortality among subjects younger than 50 years, but not among subjects ≥ 50 years old. Only among the former, chronic bronchitis was also significantly associated with serum markers indicative of increased systemic inflammation.

These findings offer an explanation to reconcile some of the inconsistencies that have emerged from previous studies on the effects of chronic bronchitis on incident COPD and mortality risk. Taken together, observations from those studies hint that the effects of chronic bronchitis on both outcomes may be stronger among young than older adults. However, ours is the first study to address systematically and demonstrate the existence of this effect modification by age within the same population, with the important advantage of removing or reducing critical sources of inter-study variation in terms of methodological approaches, genetic background of study populations, and different levels of exposure to environmental factors.

There are several possible explanations for the effect modification by age on the relation of chronic bronchitis to incident airflow limitation and mortality. First, using a fixed FEV1/FVC cut-off of 70% to define airflow limitation is likely to result in under-diagnosing COPD among young adults and over-diagnosing it among older subjects. Therefore, it is possible that the age modification is simply due to the different sensitivity and specificity of an FEV1/FVC ratio < 70% in identifying true COPD cases in different age groups. We consider this possibility unlikely because findings were confirmed when analyses were repeated after defining airflow limitation based on lower limit of normal equations for FEV1/FVC(25), which control for the age effects. Second, it is possible that the negative effects of chronic bronchitis are detected only among young adults because, among older subjects, other environmental exposures accumulate with aging and – by mid, late adult life – affect clinical outcomes in such a predominant way that they can “mask” the relatively modest effects of chronic bronchitis. While this explanation may apply to all-cause mortality (Figure 2b), it is not as plausible in relation to incident airflow limitation (Figures 1b) because older subjects did not appear to be at substantially greater risk for COPD than young adults with chronic bronchitis.

An alternative explanation is that among smokers before age 50 years – when the level of exposure to pack-years is usually lower and clearance and defense systems in the lungs more effective than at older ages – the onset of chronic bronchitis represents an “early” marker of susceptibility to the effects of cigarette smoking that will, in turn, lead to subsequent tobacco-related development of COPD and risk of premature death. Of note, these subjects would be excluded from a study on incident COPD like ours if they are enrolled in the study later in life when they have already developed airflow limitation and, thus, prevalent COPD. Therefore, in prospective studies on incident COPD like ours, subjects with chronic bronchitis who entered the study over age 50 years will be mainly represented by individuals who developed this phenotype late in adult life as a marker of weak susceptibility to smoking. This scenario is indirectly supported by the observation that, if the absence of airflow limitation at enrollment is removed from the inclusion criteria of our study, the association between chronic bronchitis and concurrent airflow limitation becomes very similar among subjects < 50 and ≥ 50 years old (OR: 3.7 and 4.2, respectively; data not shown). These observations have important public health implications because they indicate that, among smokers in their mid- to late adult life, screening for individuals with chronic bronchitis may allow identification and treatment of subjects who have developed COPD, but only among younger smokers will it also have a critical impact on identifying subjects at risk for COPD.

Our findings are also consistent with a scenario in which, among smokers with chronic bronchitis, susceptibility to clinical outcomes is at least partly mediated by a systemic inflammatory response because – much like for the association between chronic bronchitis and clinical outcomes (i.e., airflow limitation and mortality) – also the relation of chronic bronchitis to IL-8 and CRP levels appeared stronger among young than older adults. Thus, in this scenario young smokers who develop chronic bronchitis are also predisposed to mount an inflammatory response to cigarette smoking, which – in turn – puts them at increased risk for both COPD and all-cause mortality. These hypotheses could not be conclusively tested in our study because of the concurrent assessment of chronic bronchitis and molecular markers.

As expected, chronic bronchitis was strongly associated with cigarette smoking in our study and its effects on incident airflow limitation, mortality risk, and systemic inflammation appeared stronger among smokers than never smokers. Indeed, no significant association between chronic bronchitis and any of the above outcomes was found among never smokers. However, it should be noted that we had very limited statistical power to test any interaction between chronic bronchitis and smoking in our analyses because only 15 non-smokers had chronic bronchitis at enrollment. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether the effects of chronic bronchitis on these outcomes are truly absent among never smokers or if we could not detect them in this group simply because of sample size issues.

Other limitations of our study are the absence of data on lung function after bronchodilator and the possibility of residual confounding. As with most large epidemiological studies, post-bronchodilator lung function tests were not available for the vast majority of TESAOD surveys. Thus, to what extent incident airflow limitation in our study can be used as a surrogate of GOLD-defined COPD (which uses post bronchodilator lung function tests) is not known, although the exclusion of asthma cases and the strong association between smoking and airflow limitation suggest that the majority of incident cases in our study do represent subjects with COPD. In addition, it should be noted that, although analyses were adjusted for smoking status and packyears at enrollment, no information on temporal changes of smoking habits during the study follow-up was included in Cox models. However, this limitation could have inflated the association between chronic bronchitis and COPD/mortality only in the unlikely event that smokers with chronic bronchitis were more likely to continue to smoke and/or to increase the number of cigarettes smoked during the study follow-up than were smokers with no chronic bronchitis. In addition, the potential confounding effect of smoking per se appeared to have little impact on the age modification of the relation of chronic bronchitis to incident airflow limitation and mortality because inclusion of the usual number of cigarettes per day as an additional covariate in the models had virtually no effect on the interaction terms.

Strengths of our study are the population-based prospective nature of the TESAOD cohort; the multiple long-term assessments of incident airflow limitation in up to 12 follow-up surveys; the exhaustive search for information on vital status of participants via direct contact with family/next of kin as well as linkage with two national death indexes; and the availability of data on systemic biomarkers and phenotypic information. This information allowed us to adjust analyses for multiple demographic and clinical factors that are independently linked to chronic bronchitis and may act as confounders. In our study, survival analyses for incident airflow limitation (as well as those for all-cause mortality) were also adjusted for levels of the FEV1/FVC ratio at the enrollment survey, suggesting that subjects with chronic bronchitis are not at increased risk for developing COPD (or for earlier mortality) simply because they started the study with already lower levels of lung function.

In conclusion, among adults < 50 years old, chronic bronchitis represents an early marker of susceptibility to the effects of cigarette smoking. This susceptibility appears to be partly mediated by systemic inflammation and is associated with long-term increased risk for developing COPD and for all-cause mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the TESAOD research team, the study nurse Bobbe Boyer, RN, and the study participants for their extraordinary dedication to the study. We are also thankful to Susan Solomon and Stefania Scott for data management and IT support and to Robert Bilgrad for his support during the collection of mortality data from the National Death Index.

Funding

This study was funded by grants HL14136 and HL085195 by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, a grant award by the American Thoracic Society/Alpha1 Foundation, grant 0660059Z by the American Heart Association, and an unrestricted grant from the Barry and Janet Lang Donor Advised Fund.

Dr Guerra is the recipient of a Parker B. Francis Fellowship.

Footnotes

This article has an online data repository

Licence

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in THORAX editions and any other BMJPG Ltd products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in the licence at (http://thorax.bmj.com/ifora/licence.pdf).

References

- 1.Fletcher CM, Peto R, Tinker CM, Spizer FE. The natural history of chronic bronchitis and emphysema. New York: Oxford University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vestbo J, Lange P. Can GOLD Stage 0 provide information of prognostic value in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(3):329–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2112048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Marco R, Accordini S, Cerveri I, Corsico A, Anto JM, Kunzli N, et al. Incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort of young adults according to the presence of chronic cough and phlegm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(1):32–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-381OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindberg A, Jonsson AC, Ronmark E, Lundgren R, Larsson LG, Lundback B. Ten-year cumulative incidence of COPD and risk factors for incident disease in a symptomatic cohort. Chest. 2005;127(5):1544–52. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Annesi I, Kauffmann F. Is respiratory mucus hypersecretion really an innocent disorder? A 22-year mortality survey of 1,061 working men. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134(4):688–93. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.4.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekberg-Aronsson M, Pehrsson K, Nilsson JA, Nilsson PM, Lofdahl CG. Mortality in GOLD stages of COPD and its dependence on symptoms of chronic bronchitis. Respir Res. 2005;6:98. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelkonen M, Notkola IL, Nissinen A, Tukiainen H, Koskela H. Thirty-year cumulative incidence of chronic bronchitis and COPD in relation to 30-year pulmonary function and 40-year mortality: a follow-up in middle-aged rural men. Chest. 2006;130(4):1129–37. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lange P, Nyboe J, Appleyard M, Jensen G, Schnohr P. Relation of ventilatory impairment and of chronic mucus hypersecretion to mortality from obstructive lung disease and from all causes. Thorax. 1990;45(8):579–85. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.8.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krzyzanowski M, Wysocki M. The relation of thirteen-year mortality to ventilatory impairment and other respiratory symptoms: the Cracow Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1986;15(1):56–64. doi: 10.1093/ije/15.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebi-Kryston KL. Respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function as predictors of 10-year mortality from respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and all causes in the Whitehall Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(3):251–60. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stavem K, Sandvik L, Erikssen J. Can global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage 0 provide prognostic information on long-term mortality in men? Chest. 2006;130(2):318–25. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vestbo J. Chronic cough and phlegm in young adults: should we worry? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(1):2–3. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1458ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullen JB, Wright JL, Wiggs BR, Pare PD, Hogg JC. Reassessment of inflammation of airways in chronic bronchitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291(6504):1235–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6504.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gan WQ, Man SF, Senthilselvan A, Sin DD. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004;59(7):574–80. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wouters EF. Local and systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(1):26–33. doi: 10.1513/pats.200408-039MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walter RE, Wilk JB, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Keaney JF, Jr, Lipinska I, et al. Systemic Inflammation and COPD: The Framingham Heart Study. Chest. 2008;133(1):19–25. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agusti A. Systemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: what we know and what we don’t know (but should) Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(7):522–5. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-004FM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sevenoaks MJ, Stockley RA. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, inflammation and co-morbidity--a common inflammatory phenotype? Respir Res. 2006;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabbri LM, Rabe KF. From COPD to chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome? Lancet. 2007;370(9589):797–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61383-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sin DD, Man SF. Systemic inflammation and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85(1):141–7. doi: 10.1139/y06-093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghe B, Rabe KF. Complex chronic comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(1):204–12. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebowitz MD, Knudson RJ, Burrows B. Tucson epidemiologic study of obstructive lung diseases. I: Methodology and prevalence of disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1975;102(2):137–52. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ATS statement--Snowbird workshop on standardization of spirometry. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;119(5):831–8. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.119.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knudson RJ, Slatin RC, Lebowitz MD, Burrows B. The maximal expiratory flow-volume curve. Normal standards, variability, and effects of age. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;113(5):587–600. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.113.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schisterman EF, Whitcomb BW. Use of the Social Security Administration Death Master File for ascertainment of mortality status. Popul Health Metr. 2004;2(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis KB, Fisher L, Gillespie MJ, Pettinger M. A test of the National Death Index using the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) Control Clin Trials. 1985;6(3):179–91. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(85)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.