Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to examine whether rejection of novel foods during infancy predicted child behavioral and parent-reported neophobia at 4.5 years of age. Data for the present study were drawn from a longitudinal study following individuals (n = 82) from infancy through early childhood. At 6 and 12 months of age, the infants tasted a novel food (green beans, hummus, or cottage cheese) and their reactions were coded for rejection of the food (i.e. crying, force outs, or refusals). The children returned to the laboratory at 4.5 years of age and participated in a behavioral neophobia task where they were offered three novel foods (lychee, nori, and haw jelly) and the number of novel foods they tasted was recorded. Mothers also reported their own and their children's levels of food neophobia. Regression analyses revealed that rejection of novel foods at 6 months interacted with maternal neophobia to predict parent-rated child neophobia. Infants who exhibited low levels of rejection at 6 months showed higher levels of parent-rated neophobia when their mothers also showed high compared to low levels of neophobia. At 12 months of age, however, infants who exhibited high levels of rejection tended to have high levels of parent-reported neophobia regardless of their mothers’ levels of neophobia. These results provide preliminary evidence that rejection of novel foods during infancy does predict neophobia during early childhood, but the results vary depending on when rejection of new foods is measured.

Introduction

Food neophobia refers to the tendency to reject novel or unknown foods (Birch, 1999; Dovey, Staples, Gibson, & Halford, 2008). This concept originated from research with non-human animals. Omnivores, such as rats and monkeys, do not readily accept new foods. Instead, they tend to show wariness and avoidant behaviors when presented with a novel food. These types of responses serve a protective role by preventing animals from ingesting harmful toxins (Rozin, 1976). Since humans are omnivores, it is believed that they also exhibit food neophobia which emerges during the transition to solid foods during infancy (Birch, 1999). Researchers tend to agree that neophobia appears at rather low levels during weaning, but it increases and reaches a peak during early childhood (Addessi, Galloway, Visalberghi, & Birch, 2005; Birch, 1999; Dovey et al., 2008). However, there are no existing longitudinal studies examining the stability of neophobia from infancy through early childhood. The present study aims to bridge this gap in the literature by investigating whether infants’ rejection of novel foods at 6 and 12 months predicts their behavioral and parent-reported neophobia at age 4.

Previous research has revealed developmental differences in food neophobia across early childhood. Food neophobia emerges in the second half of the first year of life when infants become more mobile and begin the transition to solid foods (Addessi et al., 2005; Birch, 1999; Dovey et al., 2008). Compared to toddlers and preschoolers, infants exhibit relatively minimal neophobic tendencies. Most of infants’ reactions to new foods are positive or very positive as rated by their mothers (Lange et al., 2013; Schwartz et al., 2011). Preschoolers, on the other hand, are very reluctant to taste new foods and often reject them based on appearance alone (Birch & Fisher, 1998; Dovey et al., 2008). There are also differences in the number of exposures required to increase consumption of a novel food in infancy versus early childhood. Only one exposure during infancy can more than double consumption of a novel food on the subsequent offer (e.g. Birch, Gunder, Grimm-Thomas, & Laing, 1998), whereas multiple exposures are required in preschoolers to increase consumption (e.g. Birch, McPhee, Shoba, Pirok, & Steinberg, 1987). Birch and colleagues suggest that less intense reactions to new foods in infancy may be adaptive as parents are in more control of their children's access to food, whereas high levels of food neophobia may be more persistent in older children who are more mobile and independent (Addessi et al., 2005; Birch, 1999).

Despite the adaptive nature of food neophobia, not all children respond negatively to novel foods (Forestell & Mennella, 2012; Moding, Birch, & Stifter, 2014; Pliner & Loewen, 1997. Rather they vary on their reactions with some showing very positive responses to new foods (termed neophilic) (Pliner & Hobden, 1992). These individual differences appear to be driven by underlying temperament or personality characteristics, such as approach/withdrawal. High approach infants, who typically show positive responses to other novel objects (i.e. new toys, new people) also tend to show positive responses to novel foods, including fewer facial expressions of distaste and more acceptance behaviors compared to low approach infants (Forestell & Mennella, 2012; Moding, Birch, & Stifter, 2014). Similarly, children who are high on the temperament dimension of shyness, which is driven by approach/withdrawal processes, tend to have higher levels of food neophobia compared to their peers who are less shy (Pliner & Loewen, 1997). As approach/withdrawal tendencies are moderately stable from infancy through early childhood (e.g. Kagan & Fox, 2006), it is possible food neophobia may also show stability across the same time period.

Other factors, such as maternal neophobia, may also affect the development and stability of neophobia during early childhood. For example, previous research indicates that maternal food neophobia is positively associated with child food neophobia (e.g. Falciglia, Pabst, Couch, & Goody, 2004: Galloway, Lee, & Birch, 2003). This positive association can be explained by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. For example, food neophobia appears to be strongly heritable. In one study, genetic factors accounted for 72% of the variance in neophobia for children ages 4 through 7 (Faith, Heo, Keller, & Pietrobelli, 2013). However, environmental factors, such as food availability, also appear to play a role. Previous research shows that when the parents who are in charge of food purchasing and preparation report high levels of neophobia, they also tend to report being less likely to offer novel foods to their family members (Hursti & Sjoden, 1997). Further, parents who consumed a varied diet were found to have children with lower levels of neophobia (Faith et al., 2013; Galloway et al. 2003). Taken together, these findings suggest that a mother's own level of neophobia may influence the variety of foods she offers her child, and subsequently her child's level of neophobia. The present study will explore whether maternal neophobia moderates the relationship between rejection of novel foods during infancy and neophobia during childhood.

The present study

Two primary questions guided the present study. First, we asked whether the rejection of novel foods during infancy would predict behavioral and parent-reported neophobia at age 4. Although there are no existing longitudinal studies on this topic, previous research suggests that responses to novel foods are related to the temperament dimension of approach (e.g. Forestell & Mennella, 2012; Moding et al., 2014), which is moderately stable across early childhood (e.g. Kagan & Fox, 2006). Thus, we hypothesized that infants who were more rejecting of a novel food at 6 and 12 months of age would also be less willing to try novel foods in the laboratory and as reported by their mothers at age 4.

Second, we investigated whether maternal neophobia would moderate the relationship between rejection of novel foods during infancy and neophobia during childhood. Maternal neophobia may lessen or exacerbate initial child neophobic tendencies, but no previous research has examined this relationship. However, maternal neophobia has been shown to be related to the variety of foods mothers offer their children and subsequently their children's levels of neophobia (e.g. Faith et al., 2013; Galloway et al. 2003). Thus, we hypothesized that maternal neophobia would moderate children's initial tendencies to reject novel foods in the present study. Specifically, we expected infants who exhibited low levels of rejection at 6 and 12 months of age to be more neophobic during early childhood when their mothers had high compared to low levels of neophobia. Conversely, infants who showed high levels of rejection were expected to be less neophobic in early childhood if their mothers reported low compared to high levels of neophobia.

Method

Participants

Infant-mother dyads (N = 115; 52 female infants) were recruited as part of a longitudinal study with data collection occurring when the infants were within 2 weeks of being 4, 6, 12, and 18 months of age1. The present investigation also includes follow-up data collection of the original study sample when the children (n = 82) were 4.5 years of age. The dyads were originally recruited through birth announcements and a local community hospital in central Pennsylvania. Criteria for inclusion in the study were mothers’ full-term pregnancy, ability to read and speak English, and maternal age greater than 18 years. The families were primarily Caucasian (n = 108) and mothers averaged 29.93 years of age (range = 19 - 41) and 14.67 years of education (range = 11 - 20) at the start of the study. The highest percentage of families reported an average annual income of either $40,000 to $60,000 (26%) or $20,000 to $40,000 (25%). The majority of mothers were married (n = 93). All study procedures were approved by The Pennsylvania State University Human Subjects Institutional Review and written consent was obtained from parents for their own and their children's participation in the study.

The present study includes data from laboratory visits when the infants were 6 (n = 103) and 12 months of age (n = 95) and one laboratory visit when the children were 4.5 years of age (n = 82; M = 4.57 years). Primary reasons for study attrition include family relocation and inability to contact families to schedule laboratory visits. In addition, 22 infants were excluded from analyses using the 6-month novel food task: 21 infants were not fed solid foods at the time of the 6-month visit and 1 infant was ill during this laboratory visit. Two infants who completed the 12-month visit were excluded from analyses using the 12-month novel food task: one infant was not eating solid foods at the time of the study and one infant did not take a bite of the novel food. There were no systematic differences between the participants who completed the 4-year visit and those who dropped out of the study on the demographic (e.g., education, family income), and feeding variables (e.g., type of milk feeding, age first introduced to solid foods, 6 month novel food response). Of the infants who completed the 6-month novel food task (n = 81), 27 were exclusively breastfed for 16 or more weeks.

Procedures

Two identical novel food tasks were administered to infants at 6 and 12 months of age where the mothers fed their infants a new food for the first time. During a subsequent laboratory visit when the children were 4.5 years of age, they participated in a novel food task where they were asked if they would be willing to taste three novel and two familiar foods. The novel food tasks were digitally recorded for later behavioral coding. Procedures for each of the tasks are described in detail below. In addition, prior to each visit in the study, mothers completed a variety of questionnaires, providing demographic information about themselves and their family (e.g. years of education, family income), and confirming that their children had not previously tasted the novel foods to be used at the upcoming laboratory visits. Upon arrival to the laboratory, mothers reported on the time their infant or child had last been fed.

Infant novel food task

During the novel food tasks at 6 and 12 months, the infants sat in a high chair across from their mothers. One camera focused on the infant and another camera focused on the mother. An experimenter gave the mother a plastic spoon and a small cup containing a food that was previously identified by the mothers as novel to her infant: hummus (n = 54) or green beans (n = 27) at 6 months and hummus (n = 57) or cottage cheese (n = 36) at 12 months. The experimenter told the mother, “Please try feeding your baby the new food. If your baby accepts it, you may continue to feed the baby as long as you wish. If your baby rejects it, please try to keep feeding him/her until he/she refuses the food three times and then you may stop.” To ensure that infants’ initial response to the food was captured and not satiation, the task ended after three minutes unless the infant rejected the food three times. The experimenter watched from an observation booth for infant rejection of the novel food which included turning away, swatting the spoon, or refusing to take a bite of the food. The task ended when the experimenter observed the infant reject the food three times (6-months: n = 52 and 12-months: n = 61) or when three minutes had elapsed (6-months: n = 29 and 12-months: n = 32). The mother stopped feeding her infant after the experimenter re-entered the room unless she requested to continue feeding her infant.

Child novel food task

The novel food task at the 4.5 year visit was based on the procedures outlined in Pliner and Loewen (1997). First, an experimenter told the child that he/she would taste several foods to see how much he/she liked them, but the child first had to identify which foods he/she wanted to taste. The experimenter assured the children that they did not have to try any foods if they did not wish to. Next, the experimenter presented the child with three novel foods (lychee, nori, and haw jelly) and two familiar foods (graham cracker, carrot) in a semi-random order: familiar food #1 (graham cracker), novel food #1, novel food #2, familiar food #2 (carrot), and novel food #3. The children were always presented with a familiar food (i.e. the graham cracker) first in order to ease them into the task, but the order the novel foods were presented was randomized to control for possible order effects.

As the experimenter presented each of the foods, she asked the child, “Do you know what food this is?” and the child was allowed to respond. If the children did not respond correctly, the experimenter stated the name of the food to them. Next, the experimenter asked, “Would you like to taste the (food name)?” If the child said he/she did not wish to try the food, he/she was asked the same question with slightly different wording, “Would you like to try the (food name)?” If the child indicated that he/she wanted to taste the novel food in response to either question, the food was placed in a box out of view of the child for later tasting. If the child again responded that he/she did not wish to taste the food, the experimenter said, “It is ok. You do not have to try it if you do not want to.” The experimenter then placed the food out of view and did not present that food to the child during the tasting portion of the task. This procedure was followed for each of the study foods and none of the foods were tasted until all of the foods had been presented to the child.

Next, the experimenter presented the child with each of the foods he/she had previously selected to taste. The foods were presented for tasting in the same order they were initially presented to the child. The experimenter said, “Here is the (food name). You can go ahead and take a bite.” The experimenter recorded whether or not the child took a bite of each food and then offered the child a sip of water. This procedure was repeated until all of the selected foods were presented to the child.

Prior to the 4.5 year laboratory visit, mothers confirmed that the three novel foods (i.e. nori, lychee, and haw jelly) were novel to their children. The nori and haw jelly were novel to all children, but a few children (n = 4) had already tasted lychee prior to the laboratory visit. In these cases, another novel fruit was used as a substitute: longan (n = 2) or jackfruit (n = 2).

Measures

Infant novel food rejection

The video recordings of infants’ responses to the novel foods were coded using an interval-based computer program (Better Coding Approach, Danville, PA). Seven behaviors were coded from the videos in response to each offer of food: negative behavior, force out, refusal, positive behavior, neutral response, gagging, and distaste. Brief descriptions of each behavior are presented in Table 1. Trained pairs of coders rated the presence or absence of each behavior in response to each offer of food. An offer began when the mother approached the infant with a spoonful of novel food and ended when she began to approach the infant with another spoonful. In order to better capture infant behaviors within each offer, the offers were coded in 5-second intervals. Multiple codes could be selected for each interval. Inter-rater drift reliabilities were calculated for 20% of the total recordings. Final inter-rater reliability using Cohen's kappa for infant novel food responses can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Infants’ Behavior | Definition | Kappa (6 months) | Kappa (12 months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Behavior* | Crying, fussing, whining, or negative affect | 0.91 | 0.86 |

| Force Out* | Physically removing food from mouth | N/A | 0.81 |

| Refusal* | Swatting spoon, back arching, mouth pursed shut, turning away | 0.87 | 0.83 |

| Positive Behavior | Smiling, reaching toward the spoon, leaning forward, or opening mouth in anticipation of the next bite | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Gagging | Gagging | 0.95 | 0.94 |

| Distaste | Nose wrinkling, lip raises, or shuttering/shivering | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| Neutral Response | A neutral bite in response to the food | 0.89 | 0.85 |

Note. Kappa is a measure of inter-rater drift reliability that takes into account the agreement that may occur by chance between raters. Codes marked with an * were included in the rejection proportion scores. N/A is listed for codes that did not occur during drift reliability files.

Composite variables for analyses

Following the measurement approach used by Moding et al. (2014) in this study sample, a composite variable was created for infant rejection of the novel food at 6 and 12 months of age. In order to ensure that infants’ responses to the novel food were not influenced by satiation, scoring for infants’ responses to the novel food was limited to the first seven offers of food. The rejection proportion scores combined the scores for negative behaviors, force out, and refusal since each of these behaviors indicate a negative response or physical rejection of the food. The frequencies for these three behaviors were summed and divided by the total number of behaviors exhibited in response to the food.

Child behavioral neophobia

In the present study, children's behavioral neophobia was defined as the total number of novel foods the child was willing to taste during the novel food task (range 0 to 3). As Pliner and Loewen (1997) suggest, it is possible that some children's willingness to try new foods in the laboratory setting could be affected by other variables that may be unrelated to food neophobia, such as satiety. For this reason, children who did not taste any of the foods, novel or familiar (n = 5), were excluded from the analyses. Also, the number of familiar foods each child tasted was totaled and used as a covariate in all analyses predicting behavioral neophobia.

Parent-reported child neophobia

Prior to the 4.5 year laboratory visit, mothers completed the Food Neophobia Scale for Children (FNS-C) (Pliner, 1994). This 6-item questionnaire was adapted from the Food Neophobia Scale for adults (Pliner & Hobden, 1992) and assesses the children's willingness to try novel foods (e.g. my child does not trust new foods, my child is afraid to eat things s/he has never had before). Each item was rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher levels of neophobia. Cronbach's alpha showed internal consistency for this scale in the present study (α = .93).

Maternal neophobia

Mothers also reported on their own level of food neophobia using the 10-item Food Neophobia Scale for adults (Pliner & Hobden, 1992). Each item was rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scale included questions such as “At dinner parties, I will try a new food” and “I am constantly sampling new and different foods.” Cronbach's alpha showed internal consistency for this scale in the present study (α = .93).

Data Analysis Plan

In order to test for potential covariates that may affect the relationship between the infants’ responses to the novel foods and their level of neophobia at age 4.5 years, correlations, independent samples t-tests, and one-way ANOVA's were conducted between the behavioral and parent-reported neophobia variables at age 4.5 years and the following variables: maternal education (in years), maternal age (in years), family income, child sex, age the child was introduced to solid foods (in weeks), exclusive breastfeeding for 4 months (yes/no), amount of time since the infant last ate prior to the 6 and 12 month laboratory visits (in minutes), amount of time since the child last ate prior to the 4.5 year laboratory visit (in minutes), and the order the novel foods were presented to the child at the 4.5 year laboratory visit (6 possible presentation orders).

Child sex was significantly related to parent-reported neophobia such that males were reported by their mothers as having higher levels of neophobia (M = 1.53, SD = .76) than females (M = 1.17, SD = .70) (t (81) = 2.28, p < .05). Thus, child sex was entered as a covariate in all analyses predicting parent-reported neophobia. In order to control for the children's general willingness to taste any food in an unfamiliar laboratory setting, the number of familiar foods the children tasted during the lab task was included as a covariate in all analyses predicting behavioral neophobia. No other demographic or feeding history variables were significantly related to neophobia at age 4.5, so they were not considered further.

Preliminary analyses, including descriptive statistics and correlations, were conducted to examine the relationships among infant rejection of the novel foods at 6 and 12 months, child behavioral neophobia, and parent-reported child neophobia at 4.5 years. Next, multiple regression analyses were used to test all study hypotheses. Infant rejection of the novel food at 6 and 12 months and maternal neophobia were used to predict child behavioral and parent-reported neophobia. Interactions between infant rejection and maternal neophobia were also included in the regression models to examine the moderating effect of maternal neophobia on the relationship between rejection of novel foods during infancy and neophobia during early childhood. As approximately 21% of infants (n = 22) were not eating solid foods at the time of the 6 month laboratory visit, regression models were run separately for the 6 and 12 month novel food rejection variables in order to improve the power to predict behavioral and parent-reported child neophobia. This resulted in four total regression models.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics for all study variables can be found in Table 2 and correlations between the infant novel food rejection variables, covariates, and the food neophobia variables can be found in Table 3. The 6 and 12 month rejection variables were not significantly correlated with one another, but both infant rejection variables significantly predicted parent-reported child food neophobia. Infants who were more rejecting of the novel foods at 6 and 12 months were rated by their mothers as more neophobic during early childhood (r = .26, p <.05 and r = .30, p < .01, respectively). Behavioral and parent-reported neophobia were moderately correlated such that children who tried fewer novel foods at the 4.5-year visit were rated by their mothers as being more neophobic (r = −.32, p < .01). However, neither of the infant rejection variables was significantly correlated with the behavioral neophobia measure. Maternal neophobia was also unrelated to infant rejection of the novel foods at 6 and 12 months.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Covariates, Infant Rejection, Maternal Neophobia, and Child Neophobia Variables

| % or M | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates: | ||||

| Infant Sex: | ||||

| Males: | 54.8% | — | — | — |

| Females: | 45.2% | — | — | — |

| # Familiar Foods Tasted | 1.55 | .64 | .00 | 2.00 |

| Infant Rejection: | ||||

| 6 months | .16 | .23 | .00 | 1.00 |

| 12 months | .35 | .34 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Maternal Characteristics: | ||||

| Maternal Neophobia | 2.89 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 6.20 |

| Child Neophobia: | ||||

| Behavioral | 1.43 | 1.07 | .00 | 3.00 |

| Parent-Reported | 1.36 | .75 | .00 | 3.00 |

Table 3.

Correlations between Covariates, Infant Rejection, Maternal Neophobia, and Child Neophobia

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Infant Sex | — | ||||||

| 2. # Familiar Foods Tasted | .20+ | — | |||||

| 3. Infant Rejection: 6 months | −.11 | .00 | — | ||||

| 4. Infant Rejection: 12 months | −.14 | −.17 | .03 | — | |||

| 5. Maternal Neophobia | −.05 | .02 | .17 | .04 | — | ||

| 6. Behavioral Neophobia | .12 | .15 | −.18 | −.17 | −.17 | — | |

| 7. Parent-Reported Neophobia | −.24* | −.26* | .26* | .30** | .19+ | −.32** | — |

Note. Lower behavioral neophobia scores indicate greater food neophobia (i.e. less willingness to taste novel foods).

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

Predictors of Child Behavioral Neophobia

Table 4 contains the results of the four regression models predicting behavioral and parent-reported neophobia. Model 1 predicting behavioral neophobia from the number of familiar foods tasted, 6 month rejection, maternal neophobia, and their interaction was significant (p < .05). However, the only significant predictor in this model was the covariate, number of familiar foods tasted in the laboratory. As expected, children who tasted more familiar foods also tended to taste more novel foods, indicating a general willingness to taste any foods in a laboratory setting. Model 2 including 12 month rejection was non-significant. Neither of the rejection variables (6 or 12 months), maternal neophobia, nor the interactions between rejection and maternal neophobia significantly predicted behavioral neophobia at 4.5 years of age.

Table 4.

Multiple Regression Results for Behavioral and Parent-Reported Neophobia

| B | SE(B) | β | F | R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Behavioral Neophobia | 2.71* | .17 | |||

| # Familiar Foods Tasted | .53 | .21 | .32* | ||

| Infant Rejection 6 Months | −.58 | .54 | −.14 | ||

| Maternal Neophobia | −.09 | .11 | −.10 | ||

| Rejection 6 Months × Maternal Neophobia | −.38 | .33 | −.15 | ||

| II. Behavioral Neophobia | 1.91 | .11 | |||

| # Familiar Foods Tasted | .42 | .21 | .24* | ||

| Infant Rejection 12 Months | −.33 | .36 | −.11 | ||

| Maternal Neophobia | −.15 | .11 | −.16 | ||

| Rejection 12 Months × Maternal Neophobia | .25 | .33 | .09 | ||

| III. Parent-Reported Neophobia | 6.60*** | .31 | |||

| Infant Sex | −.64 | .17 | −.43*** | ||

| Infant Rejection 6 Months | .50 | .35 | .16 | ||

| Maternal Neophobia | .11 | .07 | .18 | ||

| Rejection 6 Months × Maternal Neophobia | −.44 | .21 | −.24* | ||

| IV. Parent-Reported Neophobia | 4.35** | .20 | |||

| Infant Sex | −.36 | .16 | −.24* | ||

| Infant Rejection 12 Months | .57 | .23 | .27* | ||

| Maternal Neophobia | .12 | .07 | .19+ | ||

| Rejection 12 Months × Maternal Neophobia | .19 | .20 | .10 |

Note.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Predictors of Parent-Reported Child Neophobia

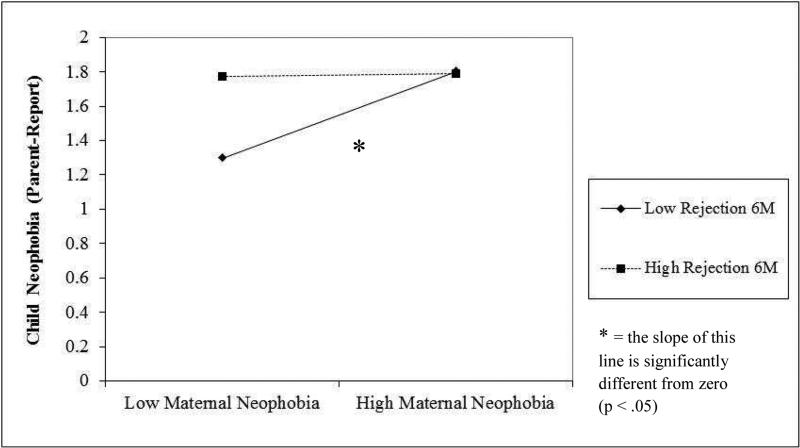

Models 3 and 4 predicting parent-reported child neophobia were significant (p's < .01). Child sex, used as a covariate in the models, significantly predicted parent-reported child neophobia such that males were more neophobic than females (p's < .05). In Model 3, the main effects of 6 month rejection and maternal neophobia were non-significant. However, the interaction between 6 month rejection and maternal neophobia emerged as a significant predictor of parent-reported child neophobia at age 4.5. Following Aiken and West's (1991) guidelines, the relationship between maternal neophobia and parent-reported child neophobia was examined separately for high and low levels of rejection at 6 months (one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively). Figure 1 illustrates this relationship. Follow-up tests revealed the slope for maternal neophobia was significantly different from zero at low levels of infant rejection only, b = 0.21, p = .02 (indicated by an asterisk in Figure 1). Among infants who had previously exhibited low levels of rejection at 6 months, higher levels of maternal neophobia predicted higher levels of parent-reported child neophobia at 4.5 years. On the other hand, infants who had previously exhibited high levels of rejection at 6 months tended to have high levels of parent-reported child neophobia regardless of their mothers’ levels of neophobia.

Figure 1.

Interaction between infant rejection of the novel food at 6 months and maternal neophobia predicting parent-reported child neophobia at 4 years.

In Model 4, 12 month rejection significantly predicted parent-reported child neophobia. Infants who were more rejecting of the novel food at 12 months were rated as more neophobic by their mothers at 4.5 years of age compared to infants who were less rejecting of the novel food. Maternal neophobia also marginally predicted parent-reported child neophobia; mothers who self-reported high levels of neophobia also tended to have children with higher levels of neophobia at age 4.5. The interaction between 12 month rejection of novel foods and maternal neophobia was non-significant.2

Discussion

To date, there are no existing longitudinal studies examining the stability of food neophobia from infancy through early childhood. Further, no studies have examined the role of maternal characteristics, such as maternal neophobia, as a potential moderator of children's responses to novel foods from infancy to early childhood. The present study aimed to address these gaps in the literature by examining whether rejection of novel foods during infancy predicted child behavioral and parent-reported neophobia at age 4.5 years and whether levels of maternal neophobia moderated this relationship. Our study provides preliminary evidence that rejection of novel foods during infancy does predict neophobia during early childhood. However, the results varied depending on when rejection was measured and how neophobia was measured. Rejection during early infancy (i.e. at 6 months of age) appears to be open to moderating effects of maternal neophobia, whereas rejection during later infancy (i.e. at 12 months of age) appears to be relatively stable overtime regardless of maternal neophobia.

Early rejection of novel foods at 6 months of age did not predict later neophobia when considered alone. Instead, the relationship between rejection of novel foods at 6 months and parent-reported child neophobia at age 4.5 years depended on levels of maternal neophobia. Specifically, children who exhibited low levels of rejection at 6 months continued to demonstrate low levels of neophobia when their mothers also had low levels of neophobia; however, children who exhibited low levels of rejection at 6 months were reported by their mothers has having high levels of neophobia when their mothers were highly neophobic. These results suggest that high levels of maternal neophobia may override young infants’ initial tendencies to show low levels of rejection in response to novel foods. One possibility for this effect is that these highly neophobic mothers may not be offering a variety of novel foods to their infants (e.g. Hursti & Sjoden, 1997) thereby limiting their exposure to novel foods. Another explanation is that neophobic mothers may be modeling neophobic behaviors which could influence their children to be more wary of new foods. On the other hand, it is important to note that the moderating influence of maternal neophobia did not appear to be present for infants who exhibited high initial rejection of novel foods. These infants continued to show negative responses to novel foods into early childhood, regardless of their mothers’ levels of neophobia. Future studies should continue to examine the ways in which parental characteristics and practices may moderate infants’ initial responses to novel foods and how these effects may be similar or different for infants exhibiting initially low versus high levels of rejection.

Compared to rejection of novel foods at 6 months, rejection at 12 months appears to be more stable and less open to parental influences. Infants who initially rejected novel foods at 12 months of age showed high levels of child neophobia, as reported by their mothers, regardless of maternal neophobia. Further, infants who had initially exhibited low levels of rejection at 12 months of age continued this pattern into early childhood whether or not their mothers were neophobic. This result for increased stability in response to novel foods is consistent with results found in the temperament literature: approach/withdrawal responses show greater stability into early childhood if they are examined in later versus earlier infancy (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). This is because of the emergence of inhibited approach in the second half of the first year of life. As a group, young infants tend to exhibit approach behaviors (e.g. low rejection, positive facial affect) in response to novelty. After six months of age, likely when they begin locomoting, infants develop the ability to inhibit their initial approach tendencies and individual differences in wariness in response to novelty emerge (e.g. Putnam & Stifter, 2002; Rothbart, 1988). It is after the emergence of these differences in inhibited behavior that approach/withdrawal responses become more stable.

Given the evidence that temperamental approach/withdrawal may underlie responses to novel food (Moding et al., 2014), this developmental pattern may explain why rejection of novel foods during later infancy was a better predictor of childhood neophobia than was rejection of novel foods during earlier infancy in the present study. However, the finding that early rejection at 6 months interacted with maternal neophobia to predict child neophobia is also noteworthy given that neophobia is said to emerge at rather low levels during early infancy (e.g. Addessi et al., 2005; Birch et al., 1998). Thus, our findings suggest that initial responses to novel foods during weaning do play a role in childhood neophobia. It is important to note the 3.5 to 4 year span between the measures of infant rejection and child neophobia. Other factors could have contributed to the stability of high or low neophobia including food availability and parent feeding practices. Further longitudinal research in this area would confirm our findings of relative stability of neophobia from infancy to early childhood.

Although child behavioral and parent-reported neophobia were moderately correlated, none of the infant rejection variables predicted our behavioral measure of child neophobia alone or when interacting with maternal neophobia. The lack of relationships in the present study may be due to the design of our behavioral task. Due to time constraints, our task was limited to the presentation of just three novel foods, whereas previous studies have included up to 10 novel foods (e.g. Pliner & Loewen, 1997). Measuring children's willingness to taste more novel foods could have provided more variability in behavioral neophobia and/or a better measure of how children generally respond to novel foods, not just how they responded to the small number of foods presented in our study. In support of this argument, results emerged for the parent-reported child neophobia measure which asked parents to indicate their children's general tendencies to respond across a variety of novel foods. Future studies should investigate whether infants’ responses to novel foods predict behavioral neophobia during childhood when a variety of novel foods are offered in the laboratory.

The results of this study need to be interpreted with respect to other limitations. In particular, the sample size for the 6 month novel food task was quite small because many of the infants were not currently eating solid foods at the time of the 6 month laboratory visit. This creates two problems. First, the 6 month sample may be artificially limited to only infants who showed low levels of rejection. Criteria for inclusion in the 6 month novel food task was daily use of solid foods in the infants’ diet at the time of the study. Infants who showed extremely high levels of rejection may not have been eating solid foods regularly by the time of their laboratory visit. Second, the models including 6 month rejection may have been underpowered due to the small sample size. Therefore, non-significant results for 6 month rejection may be due to the true lack of a relationship or to a lack of statistical power.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study examining the stability of food neophobia from infancy through early childhood. Our results provide preliminary evidence that greater rejection of novel foods during infancy predicts higher levels of food neophobia during early childhood. However, maternal neophobia played a role in the stability of child food neophobia, particularly for infants who initially showed low levels of rejection at 6 months of age. During early infancy, low levels of rejection of novel foods appeared to be overridden by mothers’ neophobic tendencies. Although future research needs to determine the potential mechanisms for this effect, this is the first study to reveal evidence for the moderating role of maternal neophobia on children's responses to novel foods from infancy to early childhood. Mothers who are neophobic should be encouraged to repeatedly offer a variety of novel foods to their infants in order to increase acceptance despite their own tendencies to be wary of novel foods.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant to the second author from the National Institutes of Digestive Diseases and Kidney (DK081512). This material is also based upon work supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2011-67001-30117. The authors want to thank the families who participated in the study

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Results from this study sample have been previously reported by Moding et al. (2014).

The results of a model combining 6 and 12 month rejection of novel foods, maternal neophobia, and their interactions were similar to the separate models for 6 and 12 month rejection. However, the interaction between 6 month rejection and maternal neophobia, as well as the main effect of 12 month rejection, dropped to marginal significance (p's = .06 and .09, respectively) likely due to reduced power.

References

- Addessi E, Galloway AT, Visalberghi E, Birch LL. Specific social influences on the acceptance of novel foods in 2-5-year-old children. Appetite. 2005;45(3):264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.07.007. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annual Review of Nutrition. 1999;19:41–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Gunder L, Grimm-Thomas K, Laing DG. Infants’ consumption of a new food enhances acceptance of similar foods. Appetite. 1998;30(3):283–295. doi: 10.1006/appe.1997.0146. http://doi.org/10.1006/appe.1997.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, McPhee L, Shoba BC, Pirok E, Steinberg L. What kind of exposure reduces children's food neophobia?: Looking vs. tasting. Appetite. 1987;9(3):171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(87)80011-9. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(87)80011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey TM, Staples PA, Gibson EL, Halford JCG. Food neophobia and “picky/fussy” eating in children: A review. Appetite. 2008;50(2–3):181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.009. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Heo M, Keller KL, Pietrobelli A. Child food neophobia is heritable, associated with less compliant eating, and moderates familial resemblance for BMI. Obesity. 2013;21(8):1650–1655. doi: 10.1002/oby.20369. http://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falciglia G, Pabst S, Couch S, Goody C. Impact of parental food choices on child food neophobia. Children's Health Care. 2004;33(3):217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Forestell CA, Mennella JA. More than just a pretty face. The relationship between infant's temperament, food acceptance, and mothers' perceptions of their enjoyment of food. Appetite. 2012;58(3):1136–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.03.005. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway AT, Lee Y, Birch LL. Predictors and consequences of food neophobia and pickiness in young girls. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103(6):692–698. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50134. http://doi.org/10.1053/jada.2003.50134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursti UK, Sjödén P. Food and general neophobia and their relationship with self-reported food choice: familial resemblance in Swedish families with children of ages 7-17 years. Appetite. 1997;29(1):89–103. doi: 10.1006/appe.1997.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Fox NA. Biology, culture, and temperamental biases. In: Damon W, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Vol. 3. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 167–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lange C, Visalli M, Jacob S, Chabanet C, Schlich P, Nicklaus S. Maternal feeding practices during the first year and their impact on infants' acceptance of complementary food. Food Quality and Preference. 2013;29(2):89–98. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.03.005. [Google Scholar]

- Moding KJ, Birch LL, Stifter CA. Infant temperament and feeding history predict infants' responses to novel foods. Appetite. 2014;83:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.08.030. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P. Development of measures of food neophobia in children. Appetite. 1994;23(2):147–163. doi: 10.1006/appe.1994.1043. http://doi.org/10.1006/appe.1994.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P, Hobden K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite. 1992;19(2):105–120. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90014-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P, Loewen ER. Temperament and food neophobia in children and their mothers. Appetite. 1997;28(3):239–254. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0078. http://doi.org/10.1006/appe.1996.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Stifter CA. Development of approach and inhibition in the first year: Parallel findings from motor behavior, temperament ratings, and directional cardiac response. Developmental Science. 2002;5(4):441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Temperament and the development of inhibited approach. Child Development. 1988;59(5):1241–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Lerner R, Eisenberg, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P. The selection of food by rats, humans, and other animals. In: Rosenblatt JS, Hinde RA, Shaw E, Beer C, editors. Advances in the study of behavior. Academic Press; New York: 1976. pp. 21–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C, Chabanet C, Lange C, Issanchou S, Nicklaus S. The role of taste in food acceptance at the beginning of complementary feeding. Physiology & Behavior. 2011;104(4):646–652. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.04.061. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]