Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the toxic effects and associated mechanisms in corneal tissue exposed to vesicating agent, nitrogen mustard (NM), a bi-functional alkylating analog of chemical warfare agent sulfur mustard (SM).

Methods

Toxic effects and associated mechanisms were examined in maximal affected corneal tissue employing corneal cultures and human corneal epithelial (HCE) cells exposed to nitrogen mustard (NM).

Results

Analysis of ex vivo rabbit corneas showed that NM exposure increased apoptotic cell death, epithelial thickness, epithelial-stromal separation and levels of VEGF, COX-2 and MMP-9. In HCE cells, NM exposure resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability and proliferation, which was associated with DNA damage in terms of an increase in p53 ser15, total p53 and H2A.X ser139 levels. NM exposure also induced caspase-3 and PARP cleavage, suggesting their involvement in NM-induced apoptotic death in rabbit cornea and HCE cells. Similar to rabbit cornea, NM exposure caused an increase in COX-2, MMP-9 and VEGF levels in HCE cells, indicating a role of these molecules and related pathways in NM-induced corneal inflammation, epithelial-stromal separation and neovascularization. NM exposure also induced activation of AP-1 transcription factor proteins and upstream signaling pathways including MAPKs and Akt, suggesting that these could be key factors involved in NM-induced corneal injury.

Conclusion

Results from this study provide insight into the molecular targets and pathways that could be involved in NM-induced corneal injuries laying the background for further investigation of these pathways in vesicant–induced ocular injuries, which could be helpful in the development of targeted therapies.

Keywords: Nitrogen mustard, corneal injury, rabbit cornea, cell death, vesication, neovascularization

INTRODUCTION

Vesicating agents cause debilitating dermal, ocular and pulmonary injuries. The ease of synthesis and the severe manifestations caused by them make these agents a potential threat as warfare agents and as terrorist weapons 1, 2. Among the vesicating agents, sulfur mustard (SM) is the most widely used warfare agent 1–4. SM penetrates ocular tissue more rapidly than skin and pulmonary tissues, causing a biphasic injury; an acute phase, expressed clinically by photophobia and inflammation, followed by delayed pathology including epithelial defects, chronic inflammation, corneal erosions, corneal opacity and corneal vascularization 5.

Despite imminent threats and devastating ocular injuries by vesicating agents 6–11, effective therapies suitable in case of a mass casualty are not established. This is primarily due to the lack of defined mechanisms contributing to pathological and clinical progression of ocular injuries by vesicants in relevant animal models. The rapid alkylating effects, and long-term deficiency of limbal stem cells have further added to the complication of developing effective therapies 12, 13. A role of oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in vesicant-induced ocular injuries has been reported 5, 14–17. Though anti-inflammatory, anti-VEGF and anti-proteolytic treatments have been shown to reduce the severity of injuries to varying degrees; mostly they are insufficient to effectively treat the vesicant-induced ocular injuries 13, 18.

NM [(Bis (2-chloroethyl)methylamine], was developed during World War I and is a highly reactive bi-functional alkylating analog of SM. Similar to SM, it covalently modifies major biomolecules (DNA, Proteins and other macromolecules) within the cell and causes ocular and dermal injuries similar to SM exposure, though the severity might differ 14, 16, 19–21. NM is commercially available and has been used by us and others to study vesicant-induced ocular injuries as an alternative to SM; this is due to limitation of easy access and use of SM in laboratory settings 16, 17, 22–25. In our previous reported study, we have shown that 24 h NM exposure caused cell death, epithelial-stromal separation and increase in the levels of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), proteolytic mediator MMP-9 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in cultured rabbit corneas 17. The present study was designed to further examine the dose- and time-response of NM exposure on these effects in freshly isolated rabbit corneas, as well as to delineate related mechanisms and underlying pathways employing human corneal epithelial (HCE) cells. Being the outermost layer of the eye, corneal epithelial layer is highly susceptible to vesicant-related injuries, which is the focus of our study 6. Furthermore, examining the early toxic effects and associated molecular events in NM-induced corneal injury both ex vivo and in cell culture would help in better understanding the injury mechanisms that could lead to the early and late injury pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Corneal organ culture (rabbit) and HCE cells

New Zealand white rabbits (8–12 weeks old) were house and acclimatized before the experiments under standard conditions, and eyes were isolated as per the protocol approved by the Institutional IACUC. The separated corneas from the eyes were cultured and NM exposed as reported earlier 17. In brief, to induce corneal injury, 50–200 nanomoles NM [(Bis (2-chloroethyl)methylamine, Mechlorethamine hydrochloride, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO] in 10 μL media applied drop wise on central cornea (n=3–6) for 2 h, and then washed and cultured for up to 48 h. At the end, 1/4th cornea was fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin and remainder was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. HCE cells (Gibco, Life technologies, NY) were cultured in Keratinocyte-SFM media supplemented with bovine pituitary extract and human recombinant epidermal growth factor and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution under standard cell culture conditions. At 50–60% confluency, cells were exposed with different doses of NM (1–200 μM) for 12–48 h. For NM washout studies, cells were exposed to NM for 2 h, and thereafter NM was removed and cells were washed and cultured for desired time. Thereafter, cell lysates were prepared and stored at −80°C as reported earlier 26.

Apoptosis, cell viability and proliferation assays

Apoptotic cell death was quantified using TUNEL system as reported 27. HCE cells (2×103 cells/well) were plated in 96-well plates, and after overnight, exposed to NM. Thereafter, MTT and BrdU assays were carried out in triplicate to measure cell viability and proliferation, respectively, as detailed recently 28.

Measurement of epithelial thickness and epithelial-stromal separation

Corneal tissues were fixed, processed and stained with H&E and evaluated microscopically for epidermal thickness and epithelial-stromal separation (microbullae formation) as detailed recently 27, 29.

Immunohistochemistry for VEGF

Corneal sections were processed, and IHC for VEGF was carried out as reported earlier 17. Brown colored cytoplasmic staining for VEGF was analyzed in 10 randomly selected fields (400× magnification), and scored as 0 (no staining), +1 (weak staining), +2 (moderate staining), +3 (strong staining), and +4 (very strong staining).

Western Immunoblotting

Lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked and probed with appropriate primary antibodies followed by incubation with peroxidase conjugated appropriate secondary antibody as reported earlier 28, 30. Protein loading was confirmed by stripping and re-probing the membranes with β-actin (whole cell/cytosolic lysates) or TBP (nuclear lysates) antibody. All the bands were scanned using Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA) and densitometric analysis were carried out by measuring the integrated density using the ImageJ Program (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey or Benferroni t-test for multiple comparisons (SigmaStat 2.03). Differences were considered significant if the p was ≤ 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM).

RESULTS

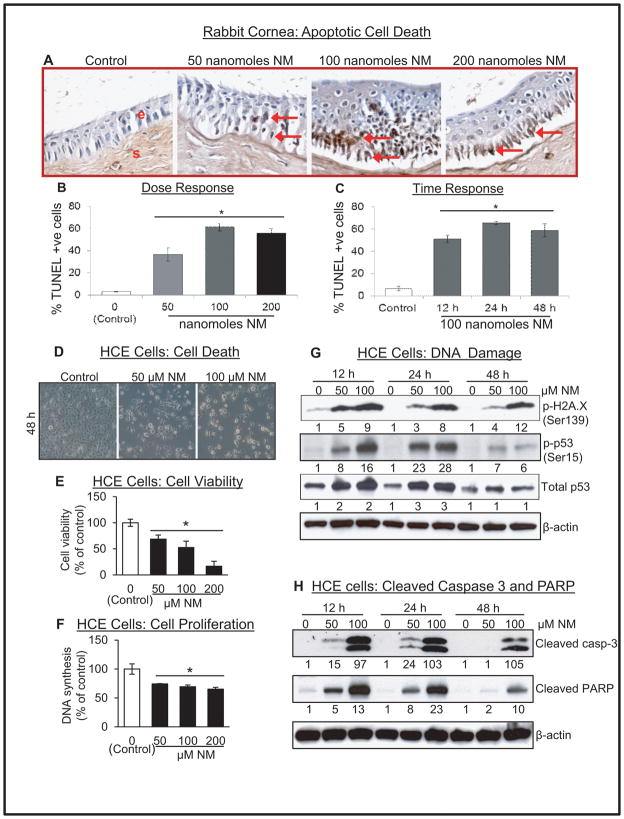

NM exposure caused apoptotic death in cornea, and reduced viability and proliferation together with DNA damage and activation of caspase-3 and PARP in HCE cells

NM exposure resulted in a significant apoptotic cell death in rabbit cornea (Fig. 1A, red arrows). Quantitation showed a maximum effect at 100 nanomoles NM (Fig. 1B), where 51, 65 and 58% apoptotic cell death was observed at 12, 24 and 48 h post exposure respectively, in the corneal epithelium compared to ~7% in vehicle control (Fig. 1C). Evidenced by morphological changes, NM induced a significant dose-dependent decrease in HCE cell viability (Fig. 1 D), which was further supported by MTT assay showing 32–87% reduction in cell viability by 50–200 μM NM exposure (Fig. 1 E). Similar NM exposures for 48 h, also resulted in a dose-dependent decrease (28–40%) in DNA synthesis compared to control cells (Fig. 1F).

Figure 1.

Effect of NM exposure on apoptotic cell death in rabbit cornea, and cell viability and proliferation, and molecular responses related to DNA damage and apoptotic cell death in HCE cells. The excised rabbit corneas were exposed to 50–200 nmol NM for 2 h, washed and cultured for 12 h or exposed to 100 nmol NM for 2 h, washed and cultured for 12, 24 or 48 h. Thereafter, the corneas were collected, processed, sectioned and subjected to TUNEL staining as detailed under Materials and methods. Representative TUNEL stained corneal sections (A) were further quantified (B & C) as brown colored TUNEL positive cells in 10 randomly selected fields at 400× magnification, and apoptotic cell index was calculated as number of apoptotic cells ×100 divided by total number of cells. HCE cells were either not exposed or exposed to 1–200 μM concentrations of NM and then examined under the light microscope for morphological analysis (D). After similar treatments, HCE cells were subjected to MTT assay (E) or BrdU assay (F) as detailed under the Materials and method section. HCE cells were either not exposed or exposed to 1–200 μM concentrations of NM and cell lysates were prepared. About 60 μg of protein sample was loaded and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by western immunoblotting for H2A.X phosphorylation, and P53 phosphorylation and accumulation (G), and cleaved caspase-3 and PARP as detailed under Materials and Methods. Protein loading was checked by stripping and re-probing the membranes with β-actin antibody and the results obtained were quantified by densitometric analysis of the immunoblots. Data presented are mean±SEM (n=3–6); *, p<0.05 as compared to control group; NM, nitrogen mustard; e, epithelial layer; s, stromal layer; red arrows, TUNEL +ve cells.

Since DNA damage could be a key event in vesicant-induced cell death, we next examined the effect of NM on DNA damage in HCE cells. DNA damage marker, H2A.X, showed an NM-induced dose-dependent increase in its phosphorylation. At 100 μM NM dose, an 8–12 fold induction was observed 12–48 h post-exposure, compared to control cells (Fig. 1G). Similarly, NM exposure also resulted in a strong dose-dependent increase in p53 phosphorylation and its accumulation at 12 and 24 h post-exposure, which decreased at 48 h (Fig. 1G). Maximal (28 fold) increase in p53 phosphorylation was observed at 100 μM NM exposure for 24 h (Fig. 1G). Subsequently, we examined the activation of caspase-poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), the main executor of apoptosis. NM exposure led to a strong dose-dependent increase in cleaved caspase-3 and PARP levels at all the study time points (Fig, 1H).

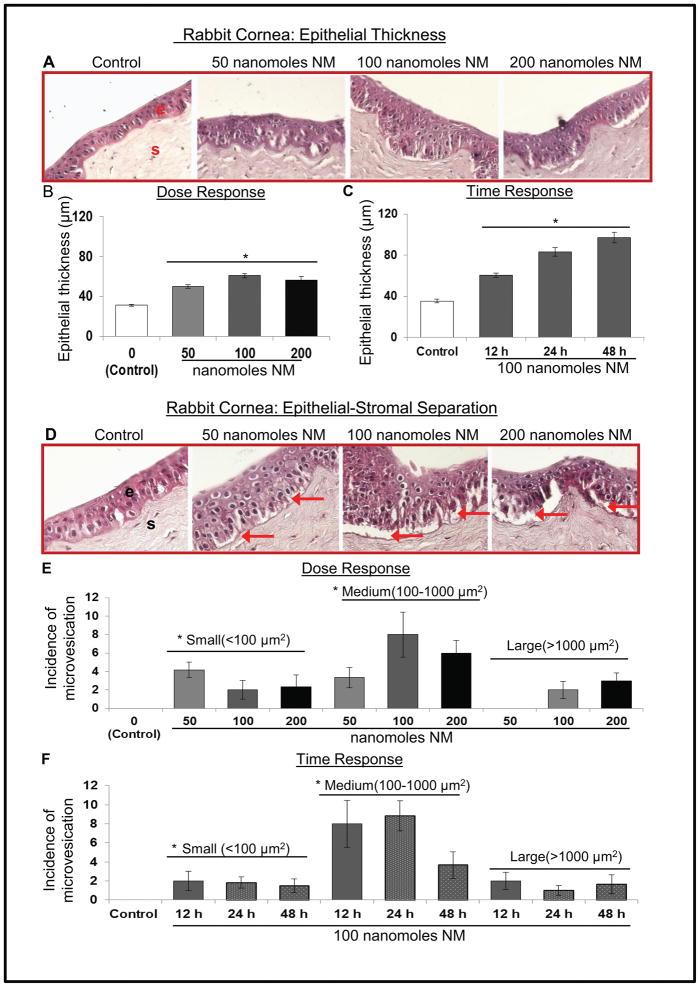

NM exposure caused an increase in epithelial thickness and induced epithelial-stromal separation in rabbit cornea

Microscopic analysis of H&E stained cornea showed an increase in epithelial thickness upon NM exposure (Fig. 2A). Quantitative analysis of the results showed an over 2 fold increase in the corneal epithelial thickness at 24 and 48 h post-100 nanomoles NM exposure (Fig. 2B), which was also a time-dependent effect (Fig. 2C). NM exposure induced epithelial-stromal separation at all the exposure concentrations and time points (Fig. 2D, red arrows). Quantitative analysis (Fig. 2E and F) showed that exposure of corneas to NM results in significantly higher incidences of small (<100μm2) and medium (100–1000μm2) sized separations at all doses, but large (>1000μm2) separations were seen only at higher doses (100 and 200 nanomoles).

Figure 2.

Effect of NM exposure on epithelial thickness and epithelial-stromal separation in rabbit cornea. The excised rabbit corneas were exposed to 50–200 nmol NM for 2 h, washed and cultured for 12 h or exposed to 100 nmol NM for 2 h, washed and cultured for 12, 24 or 48 h. Thereafter, the corneas were collected, processed, sectioned and subjected to H&E staining as detailed under Materials and methods. H&E stained sections were evaluated for epithelial thickness (A–C) and epithelial-stromal separation (D-F). Representative H&E stained corneal sections epithelial thickness (A) were quantified (B and C) as detailed under Materials and methods. Representative H&E stained corneal sections showing the incidence of epithelial-stromal separations (D) were measured at 400× magnification and classified into small (less than 100 μm2), medium (100–1000 μm2) or large (more than 1000 μm2) epithelial-stromal separations (E & F). Data presented are mean±SEM (n=3–6); *, p<0.05 as compared to control group; NM, nitrogen mustard; e, epithelial layer; s, stromal layer; red arrows, epithelial-stromal separation.

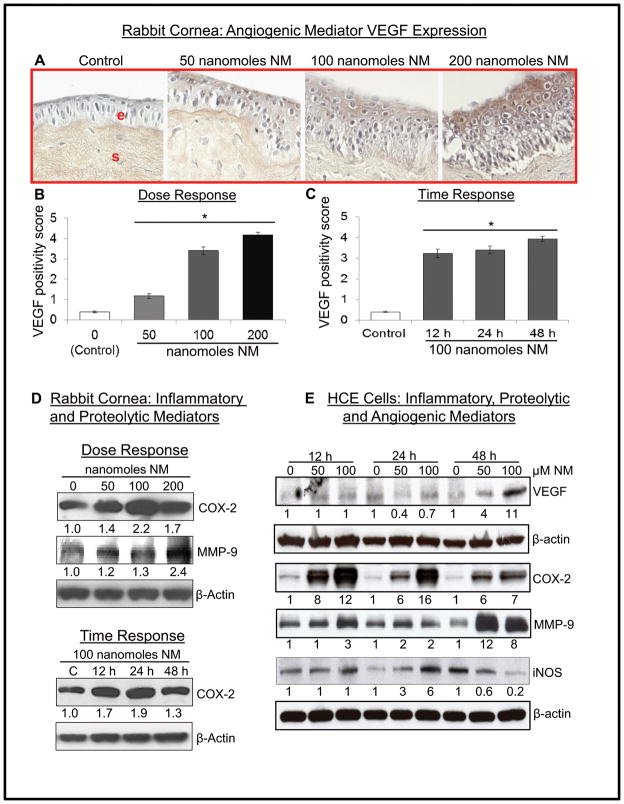

NM exposure caused an increase in VEGF, COX-2, MMP-9 and iNOS levels in rabbit cornea and HCE cells

Neovascularization is a major sign of SM-induced ocular injury where angiogenic mediator VEGF is upregulated 31. Exposure of corneas to 50, 100 and 200 nanomole NM resulted in a significant dose-dependent increase in VEGF expression in the epithelial layer (Fig. 3A and B). NM (100 nanomoles)-induced increase (~3 fold) in VEGF positivity score was evident as early as 12 h post-exposure which was maximal at 48 h (Fig. 3C). In HCE cells, NM caused a dose-dependent increase in VEGF protein levels at 48 h post-exposure (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Effect of NM exposure on inflammatory, proteolytic and angiogenic mediators in rabbit cornea and HCE cells. The excised rabbit corneas were exposed to 50–200 nmol NM for 2 h, washed and cultured for 12 h or exposed to 100 nmol NM for 2 h, washed and cultured for 12, 24 or 48 h. Thereafter, the corneas were collected, processed, sectioned and subjected to VEGF staining as detailed under Materials and methods. Representative VEGF stained cells in corneal sections (A) were scored for the brown color cytoplasmic staining (B and C). Following desired NM exposures, lysates were prepared from corneal tissue and equal amount of protein was subjected to western immunoblotting for COX-2 and MMP-9 expression (D). HCE cells were either not exposed or exposed to 50 or 100 μM concentrations of NM and cell lysates were prepared. About 60 μg of protein sample was loaded and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by western immunoblotting for VEGF COX-2, MMP-9 and iNOS levels in HCE cells (E) as detailed under Materials and methods. Protein loading was checked by stripping and re-probing the membranes with β-actin antibody and the results obtained were quantified by densitometric analysis of the immunoblots as detailed in Materials and methods. Data presented are mean±SEM (n=3–6); *, p<0.05 as compared to control group; NM, nitrogen mustard; e, epithelial layer; s, stromal layer.

As epithelial thickness and epithelial-stromal separation were evident upon NM exposure of corneas, we next assessed inflammatory and proteolytic mediators for their possible role in NM-induced responses. Both cornea and HCE cell lysates showed a dose-dependent increase in COX-2 protein levels following NM exposure (Fig. 3D and E). In time-response study, exposure to 100 nanomoles NM resulted in ~2 fold increase in COX-2 level at 24 h post-exposure (Fig. 3D). Similar result was observed in HCE cells where 100 μM NM for 12, 24 and 48 h resulted in 12, 16 and 7 fold increase in COX-2 levels, respectively, compared to control (Fig. 3E).

In rabbit cornea, exposure to 200 nanomoles NM resulted in maximal (2.4 fold) increase in proteolytic mediator MMP-9 levels compared to control at 24 h post-exposure (Fig. 3D). In HCE cells, NM exposure (50 and 100 μM) for 48 h resulted in maximal (12 and 8 fold, respectively) increase in MMP-9 levels (Fig. 3E). iNOS, which is reported to play an important role in vesicant-induced skin injury29, showed a 6 fold increase compared to controls at 24 h study time point following 100 μM NM exposure (Fig. 3E).

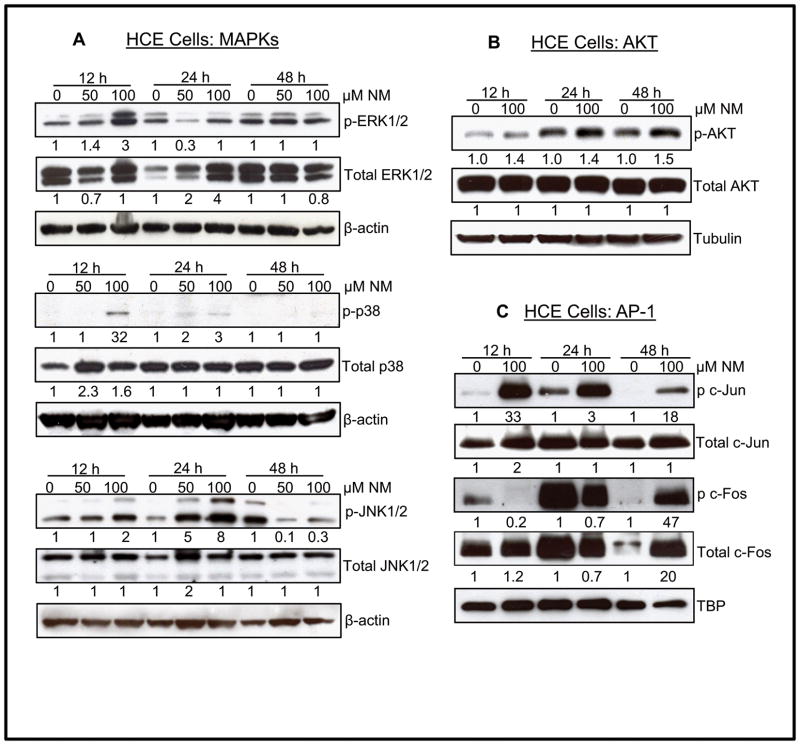

NM exposure caused an increase in the phosphorylation of MAPKs, AKT and AP-1 family proteins in HCE cells

Earlier studies have shown the role of MAPKs in SM analogs-induced skin injury 30, 32. Therefore, the involvement of MAPKs in vesicant-related ocular injury was next investigated in NM exposed HCE cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, exposure to NM (50 and 100 μM) resulted in a dose-dependent increase in phosphorylation of ERK1/2 at 12 h time point. Interestingly, whereas 12 and 48 h NM exposure times did not show noticeable changes in total ERK1/2 levels, an increase in total ERK1/2 was observed at 24 h post-exposure. NM exposure also resulted in a strong phosphorylation of stress-associated MAPKs, p38 and JNK1/2, without changing their total protein levels at 12 and 24 h time points (Fig. 4A). A maximal (32 fold) NM (100 μM)-induced phosphorylation of p38 was observed at 12 h post-exposure. However, maximal (8 fold) NM-induced increase in JNK1/2 phosphorylation was observed at 24 h post-exposure (Fig. 4A). The proto-oncogene Akt, a serine/threonine kinase involved in the regulation of cell survival and apoptosis33, was next assessed in HCE cells (Fig. 4B). A 1.4–1.5 fold increase in the phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 was observed in NM exposed (100 μM) cells as compared to controls at all the time points, without alteration in the total Akt protein levels. A strong NM-induced increase in the downstream targets (c-Jun and c-Fos) of MAPKs and Akt was also observed., Exposure of HCE cells to NM resulted in a strong c-Jun phosphorylation with the maximal increase (33 fold) at 12 h post exposure without any noticeable change in total c-Jun protein level (Fig. 4C). However, a 47 fold increase in c-Fos phosphorylation and 20 fold increase in total c-Fos levels, compared to controls, was observed only at 48 h after 100 μM NM exposure (Fig. 4C). An enhanced expression of c-Fos was also observed in control tissue, especially at 24 h, which needs to be further investigated for a possible explanation.

Figure 4.

Effect of NM exposure on phosphorylation of MAPKs, AKT and AP-1 transcription factor in HCE cells. HCE cells were either not exposed or exposed to 50 or 100 μM concentrations of NM and cell lysates were prepared. About 60 μg of protein sample was loaded and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by western immunoblotting for phosphorylated and total MAPKs: ERK, p38, SAPK/JNK (A), AKT (B), AP-1 subunits c-jun and c-fos (C) as detailed under Materials and Methods. Protein loading was checked by stripping and re-probing the membranes with β-actin, tubulin or TBP antibody and the results obtained were quantified by densitometric analysis of the immunoblots as detailed in Materials and methods. NM, Nitrogen mustard.

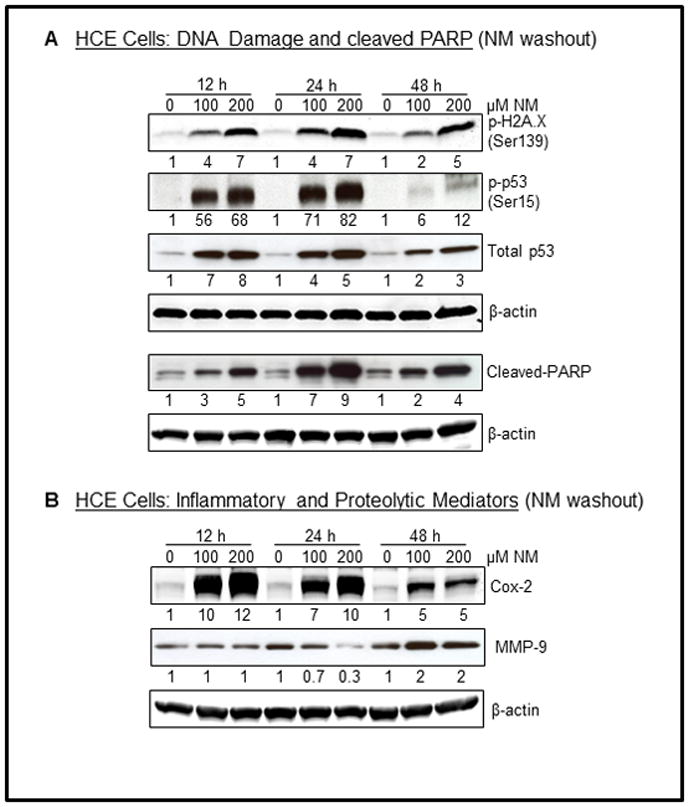

Short-term NM exposure followed by washout also caused a strong increase in DNA damage and apoptosis markers, and COX-2 and MMP-9 levels

In our results shown in Figures 1–4 above, corneas were exposed to NM for 2 h, washed and cultured for 12–48 h prior to any analyses. Conversely, HCE cells were exposed to NM continuously for 12–48 h. Therefore, we also treated HCE cells for 2 h (just like rabbit corneas) and then after washing out NM, cultured them for 12–48 h followed by the analysis of the key molecules that were up-regulated by continuous NM exposure in these cells (Figs. 1–4). As shown in Fig. 5A, similar to the results in continuously exposed HCE cells, NM exposure for 2 h also showed a dose-dependent increase in H2A.X phosphorylation at 12 h post-exposure, which sustained at later time points of 24 and 48 h. Similarly, p53 phosphorylation and its total levels also increased in a dose-dependent manner at 12 h post-NM (2 h) exposure, and remained high at 24 and 48 h time-points (Fig. 5A). Corroborating with these findings, cleaved-PARP levels also showed a dose-dependent increase as early as 12 h post-NM exposure, which increased further up to 24 h and then declined but remained higher than controls at 48 h (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B, 2 h NM exposure was sufficient to cause a strong increase in COX-2 levels at 12 h post-exposure that remained up-regulated at 24 and 48 h. However, upregulated MMP-9 levels were observed only at 48 h post-2 h NM exposure (Fig. 5B). Together, these results clearly show that irrespective of its exposure duration, NM caused a strong dose-dependent DNA damage, apoptotic death, and an increase in inflammatory and proteolytic mediators.

Figure 5.

Effect of NM exposure on DNA damage and cleaved PARP levels, and on inflammatory and proteolytic mediators in HCE cells. HCE cells were exposed to NM (100 and 200 μM) for 2 h and the cells were washed cultured for 12, 24 and 48 h time period. Thereafter, cell lysates were prepared and about 60 μg of protein sample was loaded and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by western blotting for H2A.X and p53 phosphorylation and accumulation (A), cleaved PARP (A), and COX-2 and MMP-9 levels (B) as detailed under Materials and methods. Protein loading was checked by stripping and re-probing the membranes with β-actin antibody and the results obtained were quantified by densitometric analysis of the immunoblots as detailed under Materials and methods. NM, Nitrogen mustard.

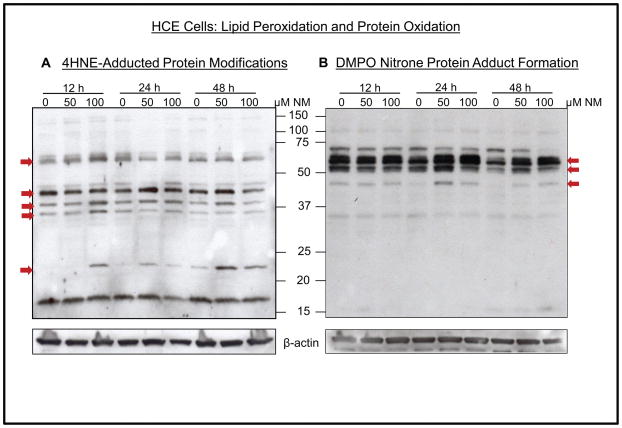

NM exposure caused lipid peroxidation and protein adduct formation in HCE cells

4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE; lipid peroxidation) and 5,5, dimethyl-2-(8-octanoic acid)-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO; nitrone protein adduct formation) were next analyzed to assess if oxidative stress was also involved in NM-induced responses 30. An increase in 4-HNE adducts was evidenced with at least five discrete and rather broad bands between molecular masses of 20–75 kDa (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 6B, NM exposure also caused an increase in DMPO staining of some bands; molecular weight markers demonstrated the most intense bands of DMPO nitrone protein adducts between 37 and 75 kDa. These results indicate a role of oxidative stress in the activation of pathways that could be involved in vesicant ocular injury.

Figure 6.

Effect of NM exposure on lipid peroxidation and DMPO nitrone protein adduct formation in HCE cells. HCE cells were either not exposed or exposed to 50 or 100 μM concentrations of NM and cell lysates were prepared. About 60 μg of protein sample was loaded and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by western immunoblotting with 4-HNE antibody (A) or anti-DMPO antibody (B). Protein loading was checked by stripping and re-probing the membranes with β-actin antibody as detailed in Materials and methods. NM, nitrogen mustard; red arrows, protein adducts.

DISCUSSION

The mechanism of ocular injury upon vesicant exposure remains poorly understood hampering the development of effective therapies to counter ocular injury in a mass casualty scenario. Restrictions with the use of SM, except in designated approved facilities, make the search for therapeutics more difficult and costly. Therefore, NM, an analogue of SM, was used in the present study to investigate the molecular mechanisms involved in vesicant-induced ocular injuries. Results from the present study corroborate with earlier published study from our lab and further for the first time show both dose- and time-dependent effects of NM on cultured rabbit corneal tissue and possible mechanism of NM-caused ocular injury. The findings reported here indicate a role for oxidative stress and DNA damage, MAPKs, COX-2, MMP-9 and VEGF in NM-induced corneal inflammation, epithelial-stromal separation and neovascularization. In addition, results from this study also show that continuous or 2 h NM exposure in HCE cells led to the activation of similar pathways. The molecules and related pathways (DNA damage, MAPKs, COX-2, MMP-9, VEGF and oxidative stress) in NM-induced ocular injury, identified in present study, are comparable to those associated with SM and NM-induced skin injury 20, 34.

In the present study, the DNA damage was observed as early as 12 h NM exposure in both cornea and HCE cells which is in line with earlier reports of DNA damage being an early event in SM exposure and related injuries 34, 35. DNA damage could be identified with an increase in histone variant H2A.X and tumor suppressor p53 phosphorylation and accumulation of total p53 36. Phosphorylation of H2A.X at Ser139 is triggered by double strands breaks in DNA while phosphorylation of p53 at Ser15 as well as total p53 level goes up following DNA damage that results in cell cycle arrest for DNA repair or apoptosis if the damage is beyond repair 37, 38. Though there is one previous report showing histopathological changes including activation of p53 with SM in rabbit cornea 9, the present study strongly suggests the role of H2A.X and p53 in NM-induced DNA damage that could be involved in corneal injury. Since NM exposure in HCE cells led to DNA damage, and activation of p53 and caspase-PARP pathways, these could be the main executors of apoptotic cell death observed in the rabbit cornea by NM. Notably, alkylation of cellular DNA and formation of DNA breaks and subsequent activation of PARP has been reported with SM exposure 39.

The present study shows both dose- and time-dependent effects of NM on the corneal tissue which further support the previous reported changes of SM-induced corneal injury, cell death, inflammation and vesication in rabbit eye 6, 10, 16, 17. Hence, this study further corroborates these biomarkers as important endpoints following NM exposure in corneal organ culture. COX-2 and iNOS are reported as key mediators in SM- and NM-induced skin inflammation and injury 20, 21, and results from present study also show their involvement in NM-induced corneal injury. Activation of proteolytic enzymes, especially MMPs, which degrade the components of extracellular matrix has been shown to result in blister formation upon vesicant exposure 40, 41. Data here showing NM-induced activation of MMP-9 in rabbit cornea as well as HCE cells, further supports its role in vesicant-induced corneal injury. Neovascularization, a significant lesion following vesicant exposure, is a delayed event observed weeks after exposure and angiogenic factor VEGF is reported to promote ocular neovascularization in animal ocular exposures 7–9, 11, 16. The early increase in VEGF expression seen here is in line with the earlier report of SM-induced increase in VEGF expression within 48 h of exposure. VEGF could have a role in repair mechanisms by increasing limbal vessel permeability and attracting monocytes apart from its role in inducing angiogenesis. This could be suggestive of an early corneal would healing event since VEGF up-regulation has been reported in corneal wound healing and might increase scarring edema and inflammation even in the absence of new blood vessels 12, 31.

MAPK/Akt-AP-1 pathway is activated by growth factors, inflammatory cytokines, stress stimuli and oxidative stress. In our study, we observed the phosphorylation of MAPKs and Akt, together with cJun and cFos in NM-exposed HCE cells, which belong to the AP-1 and CRE binding protein family of transcription factors. This indicates a role of MAPK/Akt-AP-1 pathway in the induction of COX-2, MMP-9 and VEGF in NM-induced corneal injury. Our results corroborate with the earlier report by Zheng et. al., showing the involvement of Erk1/2, JNK, PI3IK/Akt and p38 MAP kinases in UV and NM-induced ocular injury 15.

Along with DNA damage, oxidative stress is a key initiating event after vesicant exposure that possibly activates complex signal transduction pathways leading to the induction of mediators, eventually resulting into inflammatory and vesicating responses 30, 42. The generation of 4-HNE and DMPO adducts observed in the present study indicates that NM-induced oxidative stress could lead to significant lipid peroxidation and nitrone-protein adduct formation, respectively, causing activation of pathways that cause the inflammatory, proteolytic and angiogenic responses in the rabbit corneal tissue. The current study supports an earlier report that 4-HNE could be an important biomarker of vesicant-induced ocular injury and that oxidative stress might be an important mechanism mediating NM-induced corneal injury 15. Apart from oxidative stress, nitrosative stress involving nitric oxide (NO), an oxidizing agent, has also been associated with vesicant toxicity 42, 43. NO is formed via NO synthesizing enzymes including iNOS, reported to be regulated by MAPK signaling pathway. In this study, an increase in inflammatory mediator iNOS after NM exposure in HCE cells can be due to the activation of MAPK pathways; however, further studies to elaborate on the roles of oxidative or nitrosative stress in vesicant-induced mechanism of ocular toxicity are required.

The present study further supports previous reports which suggest that a therapeutic approach would be successful in treating vesicant-induced ocular injury if multiple pathways involved in injury are targeted. Apart from inflammation and corneal damage associated with the pathogenesis of vesicant-induced ocular injury, which are also seen in other disorders of ocular surface, early alkylating effects on macromolecules and vesicating properties of these agents can lead to additional modifications, adduct formation, and activation of pathways causing cell death and vesication. Hence, our studies to delineate the complex early mechanistic alterations in rabbit corneal and HCE cells that could lead to the acute as well as late chronic vesicant-induced corneal injuries are of specific importance to identify early targeted therapies. The current findings further support the rabbit corneal organ culture injury model with NM as a valuable tool to screen and identify therapies to rescue corneal injuries from vesicant exposure 17.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Countermeasures Against Chemical Threats (CounterACT) Program, Office of the Director National Institutes of Health (OD) and the National Eye Institute (NEI), [Grant Number U01EY023143]. The study sponsor had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publications.

Abbreviations

- AP-1

activator protein 1

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxy-uridine

- CEES

2, chloroethyl ethyl sulfide

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- DMPO

5,5-dimethyl-2-(8-octanoic acid)-1-pyrroline N-oxide

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- HCE cells

Human Corneal Epithelial cells

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- JNK

Jun-N terminal kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NM

nitrogen mustard

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase-9

- MTT

3-(4, 5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- PARP

poly ADP ribose polymerase

- SM

sulfur mustard

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (tdt)-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Geraci MJ. Mustard gas: imminent danger or eminent threat? Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:237–246. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saladi RN, Smith E, Persaud AN. Mustard: a potential agent of chemical warfare and terrorism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith KJ, Skelton H. Chemical warfare agents: their past and continuing threat and evolving therapies. Part I of II. Skinmed. 2003;2:215–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2003.02509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg MR. Public health, law, and local control: destruction of the US chemical weapons stockpile. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1222–1226. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruff AL, Jarecke AJ, Hilber DJ, et al. Development of a mouse model for sulfur mustard-induced ocular injury and long-term clinical analysis of injury progression. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:140–149. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2012.731666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milhorn D, Hamilton T, Nelson M, et al. Progression of ocular sulfur mustard injury: development of a model system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1194:72–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNutt P, Hamilton T, Nelson M, et al. Pathogenesis of acute and delayed corneal lesions after ocular exposure to sulfur mustard vapor. Cornea. 2012;31:280–290. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0B013E31823D02CD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadar T, Turetz J, Fishbine E, et al. Characterization of acute and delayed ocular lesions induced by sulfur mustard in rabbits. Curr Eye Res. 2001;22:42–53. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.22.1.42.6975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrali JP, Dick EJ, Brozetti JJ, et al. Acute ocular effects of mustard gas: ultrastructural pathology and immunohistopathology of exposed rabbit cornea. J Appl Toxicol. 2000;20 (Suppl 1):S173–175. doi: 10.1002/1099-1263(200012)20:1+<::aid-jat679>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javadi MA, Yazdani S, Sajjadi H, et al. Chronic and delayed-onset mustard gas keratitis - Report of 48 patients and review of literature. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safarinejad MR, Moosavi BGSA, Montazeri B. Ocular injuries caused by mustard gas: Diagnosis, treatment, and medical defense. Mil Med. 2001;166:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadar T, Amir A, Cohen L, et al. Anti-VEGF therapy (bevacizumab) for sulfur mustard-induced corneal neovascularization associated with delayed limbal stem cell deficiency in rabbits. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39:439–450. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2013.850098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwitz V, Dachir S, Cohen M, et al. The beneficial effects of doxycycline, an inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases, on sulfur mustard-induced ocular pathologies depend on the injury stage. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39:803–812. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2013.874443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banin E, Morad Y, Berenshtein E, et al. Injury induced by chemical warfare agents: characterization and treatment of ocular tissues exposed to nitrogen mustard. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2966–2972. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng R, Po I, Mishin V, et al. The generation of 4-hydroxynonenal, an electrophilic lipid peroxidation end product, in rabbit cornea organ cultures treated with UVB light and nitrogen mustard. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;272:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon MK, DeSantis A, Deshmukh M, et al. Doxycycline Hydrogels as a Potential Therapy for Ocular Vesicant Injury. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2010;26:407–419. doi: 10.1089/jop.2010.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tewari-Singh N, Jain AK, Inturi S, et al. Silibinin, dexamethasone, and doxycycline as potential therapeutic agents for treating vesicant-inflicted ocular injuries. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;264:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amir A, Turetz J, Chapman S, et al. Beneficial effects of topical anti-inflammatory drugs against sulfur mustard-induced ocular lesions in rabbits. J Appl Toxicol. 2000;20 (Suppl 1):S109–114. doi: 10.1002/1099-1263(200012)20:1+<::aid-jat669>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morad Y, Banin E, Averbukh E, et al. Treatment of ocular tissues exposed to nitrogen mustard: beneficial effect of zinc desferrioxamine combined with steroids. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1640–1646. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar D, Tewari-Singh N, Agarwal C, et al. Nitrogen mustard exposure of murine skin induces DNA damage, oxidative stress and activation of MAPK/Akt-AP1 pathway leading to induction of inflammatory and proteolytic mediators. Toxicol Lett. 2015;235:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shakarjian MP, Heck DE, Gray JP, et al. Mechanisms mediating the vesicant actions of sulfur mustard after cutaneous exposure. Toxicol Sci. 2010;114:5–19. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardej D, Billack B. Ebselen protects brain, skin, lung and blood cells from mechlorethamine toxicity. Toxicology & Industrial Health. 2007;23:209–221. doi: 10.1177/0748233707083541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pino MA, Billack B. Reduction of vesicant toxicity by butylated hydroxyanisole in A-431 skin cells. Cutaneous and Ocular Toxicology. 2008;27:161–172. doi: 10.1080/15569520802092070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain AK, Tewari-Singh N, Inturi S, et al. Histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of nitrogen mustard-induced cutaneous effects in SKH-1 hairless and C57BL/6 mice. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2014;66:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tewari-Singh N, Jain AK, Orlicky DJ, et al. Cutaneous injury-related structural changes and their progression following topical nitrogen mustard exposure in hairless and haired mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhanalakshmi S, Mallikarjuna GU, Singh RP, et al. Dual efficacy of silibinin in protecting or enhancing ultraviolet B radiation-caused apoptosis in HaCaT human immortalized keratinocytes. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:99–106. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tewari-Singh N, Rana S, Gu M, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers of sulfur mustard analog 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide-induced skin injury in SKH-1 hairless mice. Toxicol Sci. 2009;108:194–206. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tewari-Singh N, Gu M, Agarwal C, et al. Biological and molecular mechanisms of sulfur mustard analogue-induced toxicity in JB6 and HaCaT cells: possible role of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated/ataxia telangiectasia-Rad3-related cell cycle checkpoint pathway. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:1034–1044. doi: 10.1021/tx100038b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain AK, Tewari-Singh N, Gu M, et al. Sulfur mustard analog, 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide-induced skin injury involves DNA damage and induction of inflammatory mediators, in part via oxidative stress, in SKH-1 hairless mouse skin. Toxicol Lett. 2011;205:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pal A, Tewari-Singh N, Gu M, et al. Sulfur mustard analog induces oxidative stress and activates signaling cascades in the skin of SKH-1 hairless mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1640–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kadar T, Dachir S, Cohen L, et al. Ocular injuries following sulfur mustard exposure--pathological mechanism and potential therapy. Toxicology. 2009;263:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Black AT, Joseph LB, Casillas RP, et al. Role of MAP kinases in regulating expression of antioxidants and inflammatory mediators in mouse keratinocytes following exposure to the half mustard, 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;245:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romashkova JA, Makarov SS. NF-kappaB is a target of AKT in anti-apoptotic PDGF signalling. Nature. 1999;401:86–90. doi: 10.1038/43474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kehe K, Balszuweit F, Steinritz D, et al. Molecular toxicology of sulfur mustard-induced cutaneous inflammation and blistering. Toxicology. 2009;263:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jowsey PA, Williams FM, Blain PG. DNA damage, signalling and repair after exposure of cells to the sulphur mustard analogue 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulphide. Toxicology. 2009;257:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inturi S, Tewari-Singh N, Gu M, et al. Mechanisms of sulfur mustard analog 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide-induced DNA damage in skin epidermal cells and fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:2272–2280. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansson J, Lewensohn R, Ringborg U, et al. Formation and removal of DNA cross-links induced by melphalan and nitrogen mustard in relation to drug-induced cytotoxicity in human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1987;47:2631–2637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grillari J, Katinger H, Voglauer R. Contributions of DNA interstrand cross-links to aging of cells and organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7566–7576. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith WJ, Gross CL. Sulfur mustard medical countermeasures in a nuclear environment. Mil Med. 2002;167:101–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shakarjian MP, Bhatt P, Gordon MK, et al. Preferential expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in mouse skin after sulfur mustard exposure. J Appl Toxicol. 2006;26:239–246. doi: 10.1002/jat.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ray P, Chakrabarti AK, Broomfield CA, et al. Sulfur mustard-stimulated protease: a target for antivesicant drugs. J Appl Toxicol. 2002;22:139–140. doi: 10.1002/jat.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laskin JD, Black AT, Jan YH, et al. Oxidants and antioxidants in sulfur mustard-induced injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1203:92–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paromov V, Suntres Z, Smith M, et al. Sulfur mustard toxicity following dermal exposure: role of oxidative stress, and antioxidant therapy. J Burns Wounds. 2007;7:e7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]