Abstract

Purpose

Nearly half of all adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer struggle to adhere to oral chemotherapy or antibiotic prophylactic medication included in treatment protocols. The mechanisms that drive non-adherence remain unknown, leaving health care providers with few strategies to improve adherence among their patients. The purpose of this study was to use qualitative methods to investigate the mechanisms that drive the daily adherence decision-making process among AYAs with cancer.

Methods

Twelve AYAs (ages 15–31) with cancer who had a current medication regimen that included oral chemotherapy or antibiotic prophylactic medication participated in this study. Adolescents and young adults completed a semi-structured interview and a card sorting task to elucidate the themes that impact adherence decision-making. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and coded twice by two independent raters to identify key themes and develop an overarching theoretical framework.

Results

Adolescents and young adults with cancer described adherence decision-making as a complex, multi-dimensional process influenced by personal goals and values, knowledge, skills, and environmental and social factors. Themes were generally consistent across medication regimens but differed with age, with older AYAs discussing long-term impacts and receiving physical support from their caregivers more than younger AYAs.

Conclusions

The mechanisms that drive daily adherence decision-making among AYAs with cancer are consistent with those described in empirically-supported models of adherence among adults with other chronic medical conditions. These mechanisms offer several modifiable targets for health care providers striving to improve adherence among this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Adolescent, Young Adult, Medication Adherence, Decision Making

Cancer is the leading cause of disease-related death among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) ages 15 to 39 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010; National Cancer Institute, 2013). Advances in clinical care and treatment have substantially improved health outcomes for children and older adults with cancer (Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group, 2006). In contrast, survival rates for 12 of the 20 most common AYA cancers have not improved since 1985 and are up to 33% lower than those in younger children (Bleyer, 2011; Bleyer, O'Leary, Barr, & Ries, 2006; Khamly et al., 2009). Even when survival rates have improved (e.g., acute myeloid leukemia), AYAs demonstrate particularly poor outcomes, evidencing treatment-related mortality rates more than twice those of children under 15 years of age (25% versus 12%) (Canner et al., 2013).

Experts hypothesize that a primary cause of treatment failure and mortality among AYAs with cancer may be non-adherence to the oral chemotherapy and/or antibiotic prophylactic medication included in cancer treatment protocols (Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group, 2006; Bleyer, 2002). Youth who are non-adherent to oral chemotherapy, or miss more than 5% of prescribed doses, are 2.5 times more likely to relapse than adherent youth (Bhatia et al., 2012). In addition, a study of 44 adolescents with cancer found that survival rates were lower among adolescents who were non-adherent to oral antibiotic prophylactic medication than the survival rates among adolescents who were adherent (Kennard et al., 2004). As nearly half of all AYAs with cancer demonstrate non-adherence to oral chemotherapy (44%) or antibiotic prophylaxis (48%), more than 30,000 of the 69,000 AYAs diagnosed with cancer each year are likely at increased risk for devastating consequences (Bhatia et al., 2012; Festa, Tamaroff, Chasalow, & Lanzkowsky, 1992; Kondryn, Edmondson, Hill, & Eden, 2011; National Cancer Institute, 2013). Understanding and improving medication adherence may be one method of preventing relapse and reducing the survival deficit faced by AYAs with cancer (Bleyer et al., 2006).

The reasons why AYAs with cancer are non-adherent to potentially life-saving medications are not well understood (Butow et al., 2010; Kondryn et al., 2011). The few studies examining this question have identified broad constructs including deficits in information (i.e., lack of medication knowledge), limited family social support, and psychosocial difficulties (i.e., depressive symptoms) that predict non-adherence among AYAs with cancer (Hullmann, Brumley, & Schwartz, 2014; Kennard et al., 2004; Tebbi et al., 1986). While these studies identify predictors of adherence behavior, the use of broad measures and single point assessments of adherence prevent conclusions as to the mechanisms that account for these relationships (Quittner, Modi, Lemanek, Ievers-Landis, & Rapoff, 2008). Specifically, the mechanisms that explain how or why factors like social support lead AYAs with cancer to be non-adherent remain unknown. This is problematic as mechanism identification is a necessary first step in evidence-based intervention development (Kok, Schaalma, Ruiter, van Empelen, & Brug, 2004).

Identifying the mechanisms that result in non-adherence, thus, has the potential to inform clinical care and can be accomplished by conceptualizing the daily adherence decision as the result of a complex process in which AYAs consider multiple factors and make trade-offs among them (Wamboldt et al., 2011). Researchers have successfully used this approach to guide qualitative research that has elucidated how beliefs, feelings, and behaviors may lead to non-adherence among AYAs with asthma (Wamboldt et al., 2011). Extending this line of research to AYAs with cancer could clarify how medical teams can best help AYAs with cancer improve their adherence. Answering this question is critical as the only empirically-based adherence-promotion intervention for AYAs with cancer is a videogame that demonstrates limited effectiveness (d = .05–.19) (Kato, Cole, Bradlyn, & Pollock, 2008). As a result, without novel efforts to understand the adherence decision-making process, medical teams will be left with few empirically-based strategies to improve adherence among their AYA patients.

The purpose of this study was to use a grounded theory approach to develop a novel theoretical model representing how various mechanisms (including those identified in previous research) impact adherence decision-making among AYAs with cancer. To achieve this aim, semi-structured interviews were used to explore the research question: “What are the mechanisms that drive the daily adherence decision-making process among AYAs with cancer?” In addition, AYAs were asked to complete a sorting task to provide additional information on the relative importance of each mechanism and further explore the question: “How do these mechanisms influence adherence decision-making?” Results were used to generate a novel model of adherence decision-making among AYAs with cancer. Implications for future research and efforts to enhance the effectiveness of adherence-promotion interventions for AYAs with cancer are also discussed.

Materials and Methods

A grounded theory approach was used to develop a theoretical model of factors driving adherence decision-making among AYAs with cancer from the data (Holloway & Todres, 2003). Theory development began with a review of the existing literature. The literature review was conducted a priori to ensure that similar studies had not yet been conducted and identify gaps in the existing knowledge about the adherence decision-making process (Dunne, 2011). As detailed below, potential mechanisms identified from the previous literature were integrated into the semi-structured interview. Results of the interviews were then used to modify initial mechanisms and add new mechanisms as appropriate.

Participants

Participants for this study were recruited from an oncology clinic in a Midwestern Children’s Hospital in the United States. Adolescents and young adults (ages 15–39 years) with a diagnosis of cancer and a prescription for oral antibiotic prophylaxis or chemotherapy were eligible to participate. Exclusion criteria included the presence of a significant cognitive deficit, a medical status that precluded study completion, or a lack of fluency in English. Purposive sampling was used to contact patients with a wide range of diagnoses and medical regimens (oral chemotherapy or oral antibiotic prophylaxis). Thirteen AYAs were approached during an outpatient oncology clinic visit. Twelve AYAs (92% recruitment rate) agreed to participate and completed a semi-structured qualitative interview, a demographic questionnaire, and a card sorting task directly following their clinic appointment. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board and age-appropriate consent and assent (i.e., parental permission for AYAs < 18 years) were obtained.

Measures

Demographic and clinical information

Participants completed a demographic form including items assessing: patient age, gender, ethnicity, education, employment, and household composition. Cancer diagnosis, date of diagnosis, and current medical regimen were obtained via chart review. To ensure accuracy, data were entered independently by two individuals. Inconsistencies were resolved via consultation with the Principal Investigator (first author) and the medical record until 100% agreement was reached.

Qualitative interviews

One author conducted all interviews using a semi-structured guide to ensure that the same potential topics were covered for all AYAs while still allowing for the introduction of new relevant constructs. The semi-structured interview guide was developed based on previously published interview guides and expert consensus. Specifically, the authors obtained a copy of the semi-structured interview developed to identify themes influencing the decision to use infection prophylaxis among children with cancer and their caregivers and health care providers (Diorio et al., 2012). With permission, the semi-structured interview guide was modified by members of the authorship team who are experts in adherence and AYA oncology to include constructs relevant to the unique developmental period of adolescence and young adulthood (i.e., increased importance of peers, transition to independent living) that may impact adherence decision-making. An expert in decision-making serving as an outside consultant reviewed the revised interview guide and provided additional suggestions for modification.

The resulting semi-structured interview guide included questions related to: goals and priorities, patient preferences, and barriers and facilitators to adherence (e.g., “Tell me a little bit more about how you decide whether or not to take your medication each day,” “What are the types of things that influence or impact how or when you take your medication?”) and is available from the authors upon request. Consistent with the aim of grounded theory to develop a theory explaining how concepts fit together to explain a behavior (Holloway & Todres, 2003), follow-up prompts were used to encourage AYAs to describe the relevance of each factor to medication adherence decision-making and discuss the inter-relationships between each relevant mechanism.

Given the wide variability in the number and type of medications prescribed for cancer treatment, AYAs were instructed to answer questions as related to their oral chemotherapy (N = 7) or oral antibiotic prophylactic medication (N = 5). These medications were selected as previous research suggests that non-adherence to either medication may be associated with significant health consequences (Bhatia et al., 2012; Kennard et al., 2004). Follow-up prompts were used to encourage AYAs to share additional information as necessary. Interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim, and checked by an additional author for accuracy.

Card sorting task

Following the qualitative interview, AYAs were provided with a stack of cards describing mechanisms that may influence adherence decision-making. Mechanisms listed on the cards included those supported by previous studies of adherence among AYAs (i.e., Hullmann et al., 2014) and adherence decision-making (i.e., Sung et al., 2003) (see Table 3). In addition, AYAs were provided with a stack of blank cards and asked to create a card for any mechanism that impacted adherence decision-making not listed on a previous card (e.g., “my husband’s support”). Participants were then asked to classify each mechanism as “not important,” “somewhat important,” or “very important” to their adherence decision-making process. No limitations were placed on the number of mechanisms that could be classified within each category. This sorting task has been previously used by decision-making researchers (Diorio et al., 2012). In addition to providing an alternative format for generating mechanisms that influence adherence decision-making, the card sorting task provides insight into the number of factors simultaneously considered by AYAs during adherence decision-making. Specifically, the card sorting task may begin to illuminate whether adherence decision-making is driven by a single factor or a combination of factors.

Table 3.

Importance ratings of mechanisms identified in previous research

| Importance N(%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Most | Somewhat | Least | |

| Side effects that keep me from spending time with my friends | 6 (50) | 2 (17) | 4 (33) |

| Side effects from medication | 5 (42) | 4 (33) | 3 (25) |

| How much I trust my doctor | 5 (42) | 4 (33) | 3 (25) |

| Whether my caregiver encourages me to take it | 4 (33) | 7 (58) | 1 (8) |

| Whether my caregiver reminds me to take it | 4 (33) | 6 (50) | 2 (17) |

| What I’m physically feeling like that day | 4 (33) | 6 (50) | 2 (17) |

| How effective I think the medication will be for me | 4 (33) | 4 (33) | 4 (33) |

| Side effects that keep me from participating in activities | 4 (33) | 3 (25) | 5 (42) |

| What I know about how the medication works | 3 (25) | 5 (42) | 4 (33) |

| How much I trust Children’s Hospital | 3 (25) | 5 (42) | 4 (33) |

| Side effects that keep me from going to school or work | 3 (25) | 4 (33) | 5 (42) |

| The taste of the medication | 3 (25) | 2 (17) | 7 (58) |

| How effective the medication has been for other people† | 2 (18) | 3 (27) | 6 (54) |

| How many times a day I have to take it | 2 (17) | 7 (58) | 3 (25) |

| What I’m doing when it’s time to take my medication | 1 (8) | 7 (58) | 4 (33) |

| The number of pills I have to take | 1 (8) | 4 (33) | 7 (58) |

| What my friends think about me taking medication | 1 (8) | 2 (17) | 9 (75) |

| How hard it is to swallow the medication | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 10 (83) |

| What my significant other thinks about me taking medication | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 10 (83) |

| What my medication involves (e.g., taking with food) | 0 (0) | 7 (58) | 5 (42) |

| Cost of medication | 0 (0) | 5 (42) | 7 (58) |

| What kind of mood I’m in that day | 0 (0) | 3 (25) | 9 (75) |

N=11

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the clinical and demographic characteristics of the sample as well as the results of the card sorting task. To facilitate age-related comparisons, AYAs were characterized by age as “younger AYAs” (ages 15–19, N = 7) or “older AYAs” (ages 20–39, N = 5). This classification has been used previously by the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group (2006). All transcriptions were entered into NVivo 10 and coded by two independent raters (first two authors) using a grounded theory approach (NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, 2012; Holloway & Todres, 2003). All transcripts were coded twice. First, line-by-line open coding was used to define the actions and events in each line of data (Charmaz, 2000; Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Use of line-by-line coding ensures that themes are built inductively and limits the imposition of investigator beliefs/theories on the interpretation of the data (Charmaz, 2000).

Once initial coding was completed, the two raters met and presented their results. Themes were sorted into categories and sub-categories to develop an overarching theoretical framework detailing the mechanisms that influence adherence-related decision-making. For example, themes indicating that AYAs were non-adherent to avoid missing activities with friends or prevent short-term consequences were merged to create the mechanism “short-term impacts.” Discrepancies between the two raters regarding theme categorization were resolved via discussion.

The first two authors then independently coded all transcripts a second time using the established themes. Consistent with expert recommendations (Kottner et al., 2011), Cohen’s K and percentage of agreement were examined to provide a “detailed impression of the degree of reliability and agreement.” Initial inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s ) was .70 and agreement was 97%.

Discrepancies in coding style (e.g., one rater coding the entire sentence vs. one rater coding only the relevant words within that sentence) were resolved via introduction of standard procedures (code entire sentence). The raters then discussed and resolved remaining discrepancies via re-classification of a theme or modification of an existing theme until 100% agreement was reached. The frequency of each theme was described using the number of AYAs describing that theme and the percent of overall text referring to that theme (percent of text coverage).

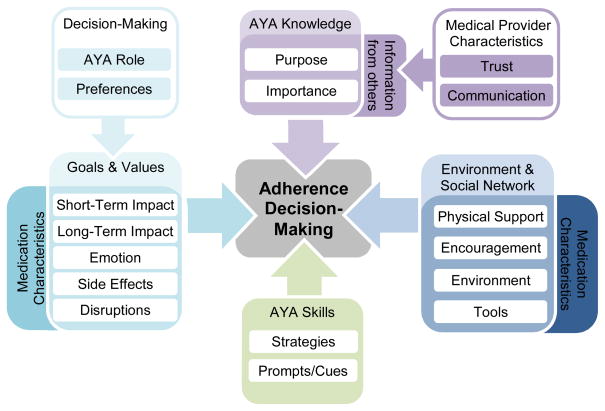

A diagram was created to detail the hypothesized relationships between themes. All three authors then independently reviewed the diagram and developed a conceptualization to describe the adherence decision-making process as depicted by the data. The authors then discussed their conceptualization, revising the diagram until consensus on an overarching theoretical model was reached (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms related to adherence decision-making among AYAs with cancer

When using a grounded theory approach to data analysis, enrollment is ended when saturation is reached, or all “new data fit into the categories already devised” (Charmaz, 2000). The ninth and tenth interviews did not result in any new themes, suggesting saturation may have been reached. This hypothesis was confirmed when the eleventh and twelfth interviews also did not provide new themes and recruitment was ended (Morse, 1995).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Study participants included 12 AYAs who ranged in age from 15 to 31 years (M = 19.91, SD = 4.86, N = 7 “younger” AYAs, N = 5 “older” AYAs) and were primarily male (N = 8, 67%). Cancer diagnoses included leukemia (N = 7, 58%, i.e., precursor B lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia), solid tumor (N = 2, 17%, i.e., pelvic rhabdomyosarcoma), brain tumor (N = 2, 17%, i.e., low grade glioma), and lymphoma (N =1, 8%, Hodgkin’s lymphoma). Time since initial cancer diagnosis ranged in time from .15 years to 9.90 years (M = 3.62, SD = 2.91).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| N(%) | M(SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 19.91 (4.86) | 15.00 – 31.08 | |

| Gender, Male | 8 (67%) | ||

| Race | |||

| White or Caucasian | 11 (92%) | ||

| Black or African-American | 1 (8%) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino, yes | 1 (8%) | ||

| Primary Caregiver | |||

| Biological mother | 9 (75%) | ||

| Biological father | 1 (8%) | ||

| Significant other | 1 (8%) | ||

| Sibling | 1 (8%) | ||

| Residing with parents, yes | 11 (92%) | ||

| Educational Level | |||

| High school student | 5 (42%) | ||

| High school graduate | 5 (42%) | ||

| College graduate | 2 (16%) | ||

| Diagnosis Group | |||

| Leukemia | 7 (58%) | ||

| Solid Tumor | 2 (17%) | ||

| Brain Tumor | 2 (17%) | ||

| Lymphoma | 1 (8%) | ||

| Time Since Diagnosis, years | 3.62 (2.91) | .15 - 9.90 | |

| Prescribed Medications | 7.33 (3.57) | 2 - 15 | |

Seven participants answered questions as related to their oral chemotherapy medication (58%) and five AYAs (42%) answered questions as related to oral antibiotic prophylactic medication. Prescribed oral chemotherapy medications included Mercaptopurine (N = 4, 57%), Dasatinib (N = 1, 14%), Everolimus (N = 1, 14%), and an investigational medication (ABT-199, N = 1, 14%). All AYAs answering questions related to an oral antibiotic prophylactic medication were prescribed Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole. On average, AYAs were prescribed a total of 7.33 medications (SD = 3.57, Range = 2–15).

Four main themes (represented in italics) and 18 subthemes (represented in parentheses) were identified in the data (see Table 2). The first main theme captured the interplay between medication characteristics and the goals and values of AYAs. AYAs were motivated to be adherent when taking a medication resulted in short-term rewards or prevented a short-term consequence (short-term impacts), helped them achieve a long-term goal or prevented a long-term consequence (long-term impacts), or prevented them or their caregivers from experiencing negative emotions (emotion). Conversely, AYAs were less motivated to be adherent when taking their medication resulted in side effects (side effects) or other factors (disruptions) that inhibited normal activities.

Table 2.

Themes and Subthemes Identified from Interviews

| Theme (N AYAs) | Definition | Sample Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Medication Characteristics and the Goals and Values of AYAs | ||

| Short-Term Impacts (N = 10) | Adhering to a medication regimen can result in short-term rewards (e.g., spending time with friends) or prevent short- term consequences (e.g., feeling sick) | “Um like, I’m pretty sure I would notice a difference with it if I stopped taking it…like I definitely like want to take those medicines because I feel like if I’m gonna take out with my friends, like oh I want to take this, because I want to feel good. I don’t want to feel like, really bad.” |

| Long-Term Impacts (N = 8) | Adhering to a medication regimen can help AYAs achieve long-term goals (e.g., returning to college) or prevent long-term consequences (e.g., being hospitalized) | “I would like to be able to get these treatments done as quickly as possible to recover as quickly as possible to get back to normal as quickly as possible…So that’s kind a what motivates me to take it.” “So for me it’s getting back to school…so I take it so I feel better” |

| Emotion (N = 9) | Adhering to a medication regimen can prevent AYAs and their caregivers from experiencing negative emotions | “When I didn’t take it I kind a felt guilty.” “So she [mother] could just feel comfortable knowing that I took it or something.” |

| Side Effects (N = 9) | Medication regimens can result in side effects that inhibit normal activities | “There have been moments when food has not tasted well to me…because if you’re out in a group, what do you normally do with people? You eat, you drink…” “During the day I would just be so tired I wouldn’t really be able to interact with people.” |

| Disruptions (N = 12) | Medication regimens can disrupt AYA’s normal activities | “Because honestly, I more commonly forget the nighttime ones because I’m, like by that time of day I’m making plans. So, you know, if I’m feeling good, then I’ll go out with friends…It just, it slips my mind.” “Well, last Saturday I was swimming with my friends…Well I know I should have grabbed it, but I was just like ‘Well, I’m already here and that’s all the way at my house…’” “Well yea, if I wake up late or just want to sleep a little bit longer, then I might put it off. Or if I’m like doing something at night or you know, like I’m out of the house or something like that then I’ll just take them when I get home. I don’t necessarily like take them with me or anything.” “Some days I feel like my whole morning is geared around finding something to eat and taking these pills.” |

| Moderators of Relationship between Rewards and Negative Consequences and Adherence | ||

| Role in Decision- Making (N = 12) | Being involved in decision-making can reduce the disruptions in daily activities caused by adherence | “I think it was just like um, I think it was basically the doctors that told us like, this is how, this is how we have our patients take this kind of med, and then that’s how I did it.” “When I first started out on Bactrim, they said just do it on weekends, twice a day on weekends. And…but for some reason they changed it to Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, morning…[but if I could change it] I might have it go back to weekends just because it’s easier to remember it that way.” |

| Patient Preferences (N = 10) | AYAs prefer to take medications that fit into their daily schedule | “That’s kinda where they recommended to take it, either in the morning or at night depending on like when you dinner and when you eat breakfast. So I just thought that would fit in my lifestyle better.” |

| AYA Knowledge | ||

| Purpose (N = 12) | The purpose of medications is to prevent relapse, mortality, or infections | “I know if I didn’t take it, if a relapse happened, I’d probably die.” “I need that medication to survive.” |

| Importance (N = 4) | Missing a few doses of a medication does not impact outcomes | “My doctors were like ‘if you forget it it’s not that big of a deal as long as you don’t like over and over again do it.’ So I never really like thought twice about it I guess if I forgot.” “Um, I think it was like more ‘Have I forgotten lately, have I skipped one recently?’. Like if I had missed one in the past like three or four days then I would, I would take it even if I had eaten. But then if I’m like ‘Oh, I haven’t missed in a couple weeks,’ then I would just be like ‘Oh it’s fine, I’ll just skip this one.’… But I think in the long run of things, I’ve gotten so much chemotherapy that I don’t think three or four doses would really affect it. At least that’s what I’m hoping.” |

| Medical Provider Characteristics Related to AYA Knowledge | ||

| Trust (N = 3) | Trust in the medical team can be a sufficient reason to take medication | “I’ve never really hesitated when someone tells me ‘you need to take this or something’ you just take it right then.” |

| Communication (N = 6) | Medication knowledge was attributed to provider communication skills | “I feel like, they know what they’re talking about, but I’m just like 'when did you start speaking a different language?’” “They just explained to me at the time that while in just sort of like as an interim chemo to fill any long periods without going inpatient. That’s really what I was taught.” |

| Skills | ||

| Strategies (N = 9) | AYAs use strategies (i.e., problem-solving, habit formation) to address barriers to adherence | “I take it before I go out…If I know I’m going overnight somewhere. Like um, I headed up to XX on a Wednesday and I knew I had to take it Wednesday night so I brought it, you know brought it with me.” “And then, especially when I was taking a lot like at the beginning of treatment and I had to take them every night. It created that habit…” |

| Prompts/Cues (N = 2) | Pairing medication taking with a regular activity served as a prompt or cue | “I think it went, went well. I just started instead of keeping them in my bathroom like right by my sink. So that, that I would remember. Like I would take a shower and then go brush my teeth and then take it.” |

| Environment and Support | ||

| Physical Support (N = 8) | Caregivers and significant others provided physical assistance (e.g., refilling pill box) | “And I would say on the days that I didn’t feel very well having help was a big reason I took some of the medications…So my husband was waking up at 3:00 am, setting the med out, you know doing all of that. I was just so tired…So that was very instrumental. Because I probably wouldn’t, to be honest, I just didn’t have the energy to do it.” “My sister…Well she’s the one who sets out like my weekly meds because I have no idea what meds I’m taking or when I’m taking them. I barely know the names of any of them. So she keeps on me track and makes sure I take the right ones when I need to.” |

| Encouragement (N = 8) | Caregivers and significant others provided reminders and encouragement | “It’s [oral chemotherapy] definitely a lot more important compared to the others. And because of that, I have her [mom] remind me to take it. So I usually, she’ll always remind me to take it if I don’t remember to take it myself. And I mean she would never let me miss that one.” |

| Environment (N = 6) | Modifying the physical environment can facilitate adherence | “So, and I always have them like sitting out on like the counter as opposed to a cabinet so that I can see it and remember it.” |

| Tools (N = 8) | Tools and systems can facilitate adherence | “Like the pill container’s bright orange. It’s just like on the table next to my bed, so it stands out being there. But I think it being a bright color definitely helps because then I like notice that it’s there” “I’ve got it pretty easy where I can just dump out my little daily box and take whatever I need to. I don’t have to really think about it.” |

Given the number of academic, social, and vocational activities AYAs are engaged in, it is not surprising that medication administration schedules that were convenient for some AYAs were disruptive for others. AYAs expressed preferences for medication regimens that “fit” their lifestyle (patient preferences). For some AYAs, being involved in the decision-making process (role in decision-making) enabled them to create a medication administration schedule that was consistent with their preferences.

Older AYAs discussed long-term impacts more than younger AYAs (90% of text coverage by 5/5 older AYAs vs. 10% of text coverage by 3/7 younger AYAs), citing the desire to return to college, obtain a job, start a family, and avoid hospitalizations. Younger AYAs may be more influenced by the impact of the medication regimen on their daily activities, discussing disruptions (younger AYAs: 55% of text coverage by 7/7 AYAs, older AYAs: 45% of text coverage by 5/5 AYAs) and the importance of a medication regimen that fits their lifestyle (patient preferences, younger AYAs: 56% of text coverage by 6/7 AYAs, older AYAs: 44% of text coverage by 4/5 AYAs) more than older AYAs.

The second main theme reflected AYA knowledge about why they were prescribed the medication (purpose) and what would happen if they missed or skipped a dose (importance). Notably, AYAs often cited the medical team as the source of their knowledge related to the medication regimen. Five AYAs (42%) reported that they “didn’t know” the purpose of their medication but took it because their caregivers or medical team “told [them] to.” The AYAs who provided information regarding the purpose of their medication (N = 7, 58%) cited its ability to prevent relapse, mortality, or infections (purpose). Four AYAs (33%) were unsure as to the consequences of missed doses and two AYAs (17%) reported that “nothing” would happen if they skipped or missed a dose of their oral chemotherapy (importance). In some instances, AYAs attributed their lack of knowledge to difficulties understanding information provided by the medical team (communication). Others, typically younger AYAs (79% of text coverage), reported a limited desire for additional information as the trust in their medical team was a sufficient reason to take medication (trust).

The third theme detailed the skills used by AYAs to facilitate adherence. When they faced barriers to adherence, nine AYAs (75%) reported the use of problem-solving and habit formation (strategies) to help them to continue to take their medication as prescribed. In addition, two AYAs (17%) reported pairing their medication with a regular activity like brushing their teeth (prompts/cues).

The final theme reflected the external factors that influence decision-making, namely environment and support. All AYAs reported that physical assistance (physical support, N = 8, 67%; i.e., refilling pill box, setting out medications) or emotional support (encouragement, N = 8, 67%; i.e., verbal reminders) from their caregivers or significant others made them more likely to decide to take their medication. Interestingly, older AYAs (ages 20–39 years) discussed receiving physical support more frequently than younger AYAs (ages 15–19 years; older AYAs: 81% vs. younger AYAs: 19% of text coverage). Conversely, younger AYAs discussed receiving reminders more than older AYAs (61% of text coverage). In addition to social support, AYAs reported that using pill boxes or containers (tools) and modifying the physical environment by placing pill boxes or containers in easily accessible and visible locations (environment) facilitated adherence.

An additional subtheme represented the complexity of the adherence decision-making process (trade-offs, not represented in Figure 1 or Table 2). Throughout the interviews, AYAs discussed weighing each of the aforementioned factors when deciding whether or not to take their medication. For example, one AYA reported significant side effects that prevented her from spending time with friends. To her, the long-term impact of the medication outweighed the negative consequence of missing social activities: “Um, it kinda makes me feel better. Like, ‘Oh this is working toward it not coming back.’ So even if it like has bad side effects or whatever, I think it’s worth it.” Results of the card sorting task further supported this hypothesis as all AYAs rated at least 4 mechanisms (Range = 4–17) as “somewhat” or “most” important to the adherence decision-making process.

Discussion

Results of this study advance science by providing a novel conceptual model of the mechanisms that may influence the adherence decision-making process among AYAs with cancer. The proposed model integrates previously-supported predictors of non-adherence among AYAs (i.e., information, social support, emotional functioning) with novel predictors (e.g., impact of side effects on daily activities) and departs from previous research by emphasizing the concurrent role of each of these factors in adherence decision-making. Specifically, the decision to take a medication was supported when adherence resulted in rewards or prevented consequences, or aligned with factors the AYA and was viewed as important. Social support, tools, strategies, and environmental modifications helped AYAs to follow-through with their decision to take a medication. Conversely, the decision to skip or forgo medication was attributed to side effects, disruptions, and the perception that skipping doses did not impact treatment outcomes.

The mechanisms related to adherence decision-making identified in this study are consistent with previous theoretical models of health behavior. Among adults with HIV, adherence decision-making is driven by motivation, information, skills, and social support (Amico et al., 2009; Fisher, Fisher, Amico, & Harman, 2006). The four primary themes emerging from this study: goals and values, knowledge, skills, and environment and support, closely mirror these predictors. Understanding each of these domains and how AYAs make trade-offs between them may help clinicians to improve adherence.

In general, AYAs conceptualized the impact of their medication regimen as it related to their specific goals and values. Consistent with normative development, older AYAs considered the long-term impacts of their medication when deciding whether or not to take a dose while younger AYAs primarily focused on the extent to which the medication would disrupt their normal daily activities (Steinberg, O’Brien, Caufman, Graham, Woolard, & Banich, 2009). Understanding the goals, values, and daily activities of a given AYA, thus, may provide insight as to the most salient method of explaining a medication. For example, one AYA described his daily decision-making as driven by his desire to return to college and the belief that taking his medication as prescribed would help him reach that goal faster.

Across both age groups and medication regimens, AYAs demonstrated gaps in their understanding of the purpose of their medication and the consequences of missed doses. Even when AYAs comprehended the treatment protocol, many struggled to understand the biological impacts of a missed medication dose. Multiple AYAs in this study rationalized intermittent non-adherence by citing the minimal consequences of skipping “a few” doses. As demonstrated by a recent study, nearly all nurses caring for patients prescribed oral chemotherapy provide information about the medication protocol as necessary (93%) but less than half (42%) ask about the patient’s understanding of the medication effectiveness (Komatsu, Yagasaki, & Yoshimura, 2014). Thus, ensuring AYAs with cancer understand the importance of consistent adherence may represent a possible intervention target.

Similar to a qualitative study of AYAs with asthma, AYAs in this study described pairing medication taking with a regular activity (e.g., brushing teeth before bed) as a major factor in promoting adherence (Wamboldt et al., 2011). Because this strategy assumes that the activity occurs at the same time each day and AYAs frequently shift their schedules (e.g., brushing teeth before bed at 10:00 pm on school days and 12:00 am on weekends), it is not surprising that AYAs often changed the activities they paired medication taking with (e.g., initially paired with brushing teeth before bed then changed regimen to pair with eating dinner) before finding an optimal strategy. This ability to problem-solve and adapt to the multiple social, academic, and occupational demands of the AYA period is a pivotal predictor of adherence among adolescents with type 1 diabetes (Wysocki et al., 2008). Importantly, AYAs often engaged in problem-solving at the suggestion of the medical team and appeared receptive to receiving adherence-promotion strategies from health care providers. As adherence-promotion interventions delivered by health care providers demonstrate promising effect sizes (Wu & Pai, 2014), researchers may wish to consider developing adherence-promotion interventions for AYAs with cancer that can be delivered by nurses or other health care providers.

Adolescents and young adults of all ages emphasized the role of caregivers and significant others in adherence decision-making. The specific role of caregivers and significant others may shift with age as younger AYAs described reminders and encouragement as helpful while older AYAs cited the importance of physical support (e.g., caregiver refilling pill box) and often described a support network including individuals beyond their parents (i.e., significant other, sibling). These findings suggest that an AYA’s preferences and relationships are likely to dictate the impact of social support on adherence, and should be considered when allocating treatment responsibility.

Throughout the interviews, AYAs emphasized the interplay between the aforementioned factors. Goals and values, knowledge, skills, or environmental and social factors in isolation are unlikely to result in optimal adherence (Amico et al., 2009). Instead, adherence decision-making among AYAs with cancer appears to involve factors that result in their intention to take the medication (goals and values, knowledge) and factors that help them follow-through with this plan (skills, and environmental and social factors). This interdependent relationship has been well-documented in the adult literature and explains why some AYAs who are either motivated to be adherent or possess the necessary social support still struggle with non-adherence (Schwarzer, 2008).

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, as the purpose of this study was to identify over-arching mechanisms that impact adherence decision-making among AYAs with cancer, differences between diagnostic groups were not examined. Caution should be used when applying these findings to diagnoses not represented in this sample and future research should examine the applicability of the proposed model within specific diagnostic groups. Second, as actual adherence behavior was not assessed, longitudinal research is needed to determine if the identified mechanisms predict adherence decision-making over time. Third, the cross-sectional nature of this research precluded the observation of developmental changes. Longitudinal cohort studies following individuals as they undergo the significant transitions of young adulthood (i.e., independent living) are needed to explore the age-related differences noted here. The novel conceptualization of adherence as a decision-making process used in this study elucidated mechanisms that may explain why AYAs with cancer struggle with non-adherence. These findings provide direction for researchers and clinicians striving to improve adherence in this at-risk population.

Highlights.

The mechanisms driving adherence decision-making were explored.

Adherence decision-making is a complex, multi-dimensional process.

Adolescent and young adult goals and values, knowledge and skills impact adherence.

Environmental and social factors also impact adherence decision-making.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: The design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation of the manuscript were supported in part by grant T32HD068223 for M.E.M.

Abbreviations

- AYA

Adolescent and young adult

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adolescent and Young Adults Oncology Progress Review Group. [accessed 07/11/14];Closing the gap: Research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer. 2006 Available at: http://planning.cancer.gov/library/AYAO_PRG_Report_2006_FINAL.pdf.

- Amico KR, Barta W, Konkle-Parker DJ, Fisher JD, Cornman DH, Shuper PA, Fisher WA. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model of ART adherence in a Deep South HIV+ clinic sample. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(1):66–75. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9311-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S, Landier W, Shangguan M, Hageman L, Schaible AN, Carter AR, et al. Nonadherence to oral mercaptopurine and risk of relapse in hispanic and non-hispanic white children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(17):2094–2101. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.38.9924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleyer A. Latest estimates of survival rates of the 24 most common cancers in adolescent and young adult Americans. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. 2011;1(1):37–42. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2010.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleyer A, O'Leary M, Barr R, Ries L. Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, including SEER incidence and survival: 1975–2000. National Cancer Institute; Maryland: 2006. NIH Pub. No. 06-5767. [Google Scholar]

- Bleyer WA. Cancer in older adolescents and young adults: Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, survival, and importance of clinical trials. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 2002;38(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butow P, Palmer S, Pai A, Goodenough B, Luckett T, King M. Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(32):4800–4809. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.22.2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canner J, Alonzo TA, Franklin J, Freyer DR, Gamis A, Gerbing RB. Differences in outcomes of newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia for adolescent/young adult and younger patients: A Report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer. 2013;119(23):4162–4169. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. [accessed 07/11/14];United States Cancer Statistics, 1999–2010 Mortality Request. 2010 Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/CancerMort-v2010.html.

- Charmaz . Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2. Sage Publications, Inc; California: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3. Sage Publications, Inc; California: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Diorio C, Tomlinson D, Boydell KM, Regier DA, Ethier MC, Alli A, et al. Attitudes toward infection prophylaxis in pediatric oncology: A qualitative approach. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne C. The place of the literature review in grounded theory research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2011;14(2):111–124. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2010.494930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Festa RS, Tamaroff MH, Chasalow F, Lanzkowsky P. Therapeutic adherence to oral medication regimens by adolescents with cancer. I. Laboratory assessment. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1992;120(5):807–811. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychology. 2006;25(4):462–473. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway I, Todres L. The status of method: Flexibility, consistency and coherence. Qualitative Research. 2003;3(3):345–357. doi: 10.1177/1468794103033004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hullmann SE, Brumley LD, Schwartz LA. Medical and psychosocial associates of nonadherence in adolescents with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2014 Nov 3; doi: 10.1177/1043454214553707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato PM, Cole SW, Bradlyn AS, Pollock BH. A video game improves behavioral outcomes in adolescents and young adults with cancer: A randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e305–317. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennard B, Stewart S, Olvera R, Bawdon R, hAilin A, Lewis C, et al. Nonadherence in adolescent oncology patients: Preliminary data on psychological risk factors and relationships to outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2004;11(1):31–39. doi: 10.1023/B:JOCS.0000016267.21912.74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khamly KK, Thursfield VJ, Fay M, Desai J, Toner GC, Choong PF, et al. Gender-specific activity of chemotherapy correlates with outcomes in chemosensitive cancers of young adulthood. International Journal of Cancer. 2009;125(2):426–431. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok G, Schaalma H, Ruiter RAC, Van Empelen P, Brug J. Intervention mapping: A protocol for applying health psychology theory to prevention programmes. Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9(1):85–98. doi: 10.1177/1359105304038379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Yoshimura K. Current nursing practice for patients on oral chemotherapy: a multicenter survey in Japan. BMC Research Notes. 2014;7:259. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondryn HJ, Edmondson CL, Hill J, Eden TOB. Treatment non-adherence in teenage and young adult patients with cancer. Lancet Oncology. 2011;12:100–108. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottner J, Audige L, Brorson S, Donner A, Gajewski BJ, Hróbjartsson A, Roberts C, Shoukri M, Streiner DL. Guidelines for reporting reliability and agreement studies were proposed. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2011;49:661–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse The Significance of Saturation. Qualitative Health Research. 1995;5(2):147–149. doi: 10.1177/104973239500500201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. [accessed: 07/11/14];A snapshot of adolescent and young adult cancers. 2013 Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/researchandfunding/snapshots/adolescent-young-adult.

- NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 10) QSR International Pty Ltd; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Quittner AL, Modi AC, Lemanek KL, Ievers-Landis CE, Rapoff MA. Evidence-based assessment of adherence to medical treatments in pediatric psychology. The Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33(9):916–936. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm064. discussion 937–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohan JM, Drotar D, Alderfer M, Donewar CW, Ewing L, Katz ER, Muriel A. Electronic monitoring of medication adherence in early maintenance phase treatment for pediatric leukemia nad lymphoma: Identifying patterns of non-adherence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2015;40(1):75–84. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology. 2008;57(1):1–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00325.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, O’Brien L, Cauffman E, Graham S, Woolard J, Banich M. Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Development. 2009;80(1):28–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung L, Alibhai SM, Ethier M, Teuffel O, Cheng S, Fisman D, Regier DA. Discrete choice experiment produced estimates of acceptable risks of therapeutic options in cancer patients with febrile neutropenia. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2012;65(6):627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebbi CK, Cummings KM, Zevon MA, Smith L, Richards M, Mallon J. Compliance of pediatric and adolescent cancer patients. Cancer. 1986;58(5):1179–1184. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860901)58:5<1179::aid-cncr2820580534>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamboldt FS, Bender BG, Rankin AE. Adolescent decision-making about use of inhaled asthma controller medication: Results from focus groups with participants from a prior longitudinal study. The Journal of Asthma. 2011;48(7):741–750. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.598204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YP, Pai AL. Health care provider-delivered adherence promotion interventions: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1698–1707. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki T, Harris MA, Buckloh LM, Mertlich D, Sobel Lochrie A, Taylor A, Sadler M, White NH. Randomized, controlled trial of a behavioral family systems therapy for diabetes: Maintenance and generalization of effects on parent-adolescent communication. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]