Abstract

This work examines cocrystal solubility in biorelevant media, (FeSSIF, fed state simulated intestinal fluid), and develops a theoretical framework that allows for the simple and quantitative prediction of cocrystal solubilization from drug solubilization. The solubilities of four hydrophobic drugs and seven cocrystals containing these drugs were measured in FeSSIF and in acetate buffer at pH 5.00. In all cases, the cocrystal solubility (Scocrystal) was higher than the drug solubility (Sdrug) in both buffer and FeSSIF; however, the solubilization ratio of drug, SRdrug = (SFeSSIF/Sbuffer)drug, was not the same as the solubilization ratio of cocrystal, SRcocrystal = (SFeSSIF/Sbuffer)cocrystal, meaning drug and cocrystal were not solubilized to the same extent in FeSSIF. This highlights the potential risk of anticipating cocrystal behavior in biorelevant media based on solubility studies in water. Predictions of SRcocrystal from simple equations based only on SRdrug were in excellent agreement with measured values. For 1:1 cocrystals, the cocrystal solubilization ratio can be obtained from the square root of the drug solubilization ratio. For 2:1 cocrystals, SRcocrystal is found from (SRdrug)2/3. The findings in FeSSIF can be generalized to describe cocrystal behavior in other systems involving preferential solubilization of a drug such as surfactants, lipids, and other drug solubilizing media.

Introduction

Pharmaceutical cocrystals have emerged as a useful strategy to improve the aqueous solubility of inherently poorly soluble drugs to improve their oral absorption and bioavailability1–6. Cocrystal solubility can be orders of magnitude higher than that of the constituent drug in aqueous solutions; however, in biorelevant media the change in solubility of the cocrystal and the constituent drug can be very different. In the presence of a solubilizing agent, a cocrystal can display higher, equal, or lower solubility than the constituent drug, depending on the concentration of the additive7–9.

The underlying mechanism for this behavior is the preferential solubilization of the drug constituent over the coformer7–9. Generally, drugs are much more hydrophobic than coformers and therefore preferential drug solubilization is often observed with solubilizing agents in aqueous media7–11. This behavior leads to a nonlinear dependence of cocrystal solubility on solubilizing agent concentration as illustrated in Figure 1. As surfactant is added to aqueous media the solubility of the drug will increase at a higher rate compared to a cocrystal, so that the solubility curves of cocrystals and drug may intersect. Cocrystal solubility (1:1 cocrystal stoichiometry) has been shown to have a square-root dependence on conventional surfactant concentration, whereas the drug has a linear dependence. As surfactant concentration is increased, the cocrystal solubility can reach a point where it is equal to the drug solubility, and above this surfactant concentration the cocrystal solubility is lower than the drug solubility. This intersection point is a cocrystal transition point, characterized by a solubilizing agent concentration (CSC, or critical stabilization concentration) and a solubility at which both drug and cocrystal are in equilibrium (S*)12. Failing to take such behavior into account when designing cocrystal dosage forms could lead to unanticipated variability in cocrystal performance and unnecessary risks for cocrystals of poorly soluble drugs selected as the preferred crystalline for further development.

Figure 1.

Transition point (S* and CSC) for a 1:1 cocrystal (red line) and its constituent drug (blue line) in the presence of solubilizing agent. The curves represent the theoretical cocrystal and drug solubility dependence on solubilizing agent concentration when only drug, not coformer, is solubilized by solubilizing agent. Cocrystal maintains its solubility advantage over drug, below the transition point.

Physiologically relevant surfactants composed of bile salts and phospholipids have been shown to greatly influence the solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs13–17; however, the effect of physiologically relevant surfactants on the solubility of cocrystals of poorly soluble drugs remains to be established. The in-vivo exposure of cocrystals to varying concentrations of the ubiquitous surfactants present in biological fluids supports the need for improved understanding of cocrystal solubility in biorelevant media. The central hypothesis of the research presented here is that physiological surfactants such as those encountered in intestinal fluids will solubilize cocrystals to a lesser extent than drugs when the drug (not the coformer) is preferentially solubilized in biorelevant media.

The aim of this work is to derive simple mathematical models that predict cocrystal solubilization in biorelevant media based on the underlying solubilization mechanisms. The solubilities of seven cocrystals comprised of hydrophobic drugs, several of which are reported to exhibit food effects18–20were measured in fed state simulated intestinal fluid (FeSSIF) and pH 5 acetate buffer (blank FeSSIF). FeSSIF was chosen due to its relatively high concentration of sodium taurocholate (NaTC) and the phosopholipid lecithin which are known to form mixed micelles in solution and significantly solubilize poorly water-soluble drugs17. The cocrystals include both 1:1 and 2:1 cocrystal stoichiometries and cover a range of ionization behaviors for both drug and coformers (Table 1). Nonionic drugs include carbamazepine and danazol. Ionizable drugs include the acidic drug indomethacin and the zwitterionic drug piroxicam. All coformers are acidic except for 4-aminobenzoic acid (4ABA), which is amphoteric.

Table 1.

Cocrystals studied and pKa values of their constituents.

| Cocrystal | API:CF | Drug (API) | Coformer (CF) | pKa API | pKa CF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 CBZ-SAC | 1:1 | carbamazepine | saccharin | - | 1.6–2.221,22 |

| 2 CBZ-SLC | 1:1 | carbamazepine | salicylic acid | - | 3.021 |

| 3 CBZ-4ABA (H) | 2:1 | carbamazepine | 4-aminobenzoic acid | - | 2.6 and 4.823 |

| 4 PXC-SAC | 1:1 | piroxicam | saccharin | 1.86 and 5.4624 | 1.6–2.221,22 |

| 5 IND-SAC | 1:1 | indomethacin | saccharin | 4.225 | 1.6–2.221,22 |

| 6 DNZ-HBA | 1:1 | danazol | 4-hydroxybenzoic acid | - | 4.4826 |

| 7 DNZ-VAN | 1:1 | danazol | vanillin | - | 7.427 |

Theoretical

Estimation of cocrystal solubilization based on drug solubilization in surfactant media

The addition of drug solubilizing agents to aqueous media will increase the solubility of both a cocrystal and its constituent drug, but the magnitude of solubilization will be different for each solid form. The relative increase in solubility for each crystal form in aqueous media compared to media containing drug solubilizing agents can be characterized by a solubilization ratio (SR). This solubilization ratio for cocrystal or drug, SRcocrystal or SRdrug, in media containing drug solubilizing agents has been previously described7,28. SR for a 1:1 cocrystal can be estimated from knowledge of the constituent drug solubility increase in such media at a given pH according to

| (1) |

SR is defined as the total solubility in surfactant media (ST) divided by the aqueous solubility (Saq). ST represents the sum of the concentrations of all species dissolved (ST = Saq + Ss). Saq represents the cocrystal aqueous solubility at a given pH in the absence of solubilizing agent (Saq = Snonionized,aq + Sionized,aq) and is the sum of the nonionized and ionized contributions to the aqueous solubility. Ss represents the cocrystal solubilized by solubilizing agents (Ss = Snonionized,s + Sionized,s) and contributions from the nonionized and ionized species as appropriate.

For 2:1 cocrystal the relationship between SRcocrystal and SRdrug becomes

| (2) |

For a cocrystal AxBy, where A and B are the drug and coformer, the general form of this relationship is7

| (3) |

These equations apply to the condition that solubilizing agents only solubilize the drug and not the coformer. Such a condition is justified as cocrystals are generally composed of poorly water-soluble, hydrophobic drugs and soluble, hydrophilic coformers. Coformers, therefore, interact to a far lesser extent with solubilizing agents than the drug constituents. The significantly higher affinity of the drug for the solubilizing agent compared to the coformer is the primary reason why cocrystals and their constituent drugs display such large differences in solubility as a function of surfactant concentration.

The above relationships are derived from the solubility equations for drug and cocrystal in media containing solubilizing agents12. For the case of a 1:1 cocrystal of a nonionizable drug and an ionizable (monoprotic) acidic coformer, the cocrystal solubility in micellar surfactant media is

| (4) |

Ksp is the cocrystal solubility product, Ks stands for solubilization constants of cocrystal constituents, and [M] is solubilizing agent concentration. For the case of a micellar surfactant, [M] is the total surfactant concentration minus the critical micellar concentration (CMC). Ka represents the dissociation constant of a monoprotic acidic coformer. When the solubilizing agent enhances drug solubility and not coformer solubility, (Kscoformer = 0), the cocrystal total solubility equation becomes

| (5) |

The above equation can be written in terms of Scocrystal,aq as

| (6) |

Combining the equation that describes the drug solubility in micellar solutions

| (7) |

with equation (6) and solving for the cocrystal solubilization ratio (ST/Saq)cocrystal gives

which is equation (1). Relationships for other cocrystal stoichiometries and ionization properties of constituents are similarly derived from equations that describe cocrystal and drug solubilities as a function of ionization and solubilization7.

As this analysis shows, cocrystal solubilization in media containing micellar surfactants is not equal to that of drug. The cocrystal solubility increase in surfactant media is predicted to be equal to the square-root of the drug solubility increase and is expected to be constant for a series of cocrystals of a given drug.

In the absence of any experimental measurement of cocrystal solubilities, this simple equation (equation 3) provides a theoretical framework that facilitates a discussion of the general features of cocrystals exposed to media containing solubilizing surfactants. Figure 2 illustrates the influence of a drug solubilizing agent on the solubility of a hypothetical drug and three different (1:1) cocrystals of the drug. All cocrystals are shown to be more soluble than the drug in aqueous media (Scocrystal,aq are 2, 3, and 4 times higher than Sdrug,aq), but this is not the case in the presence of a drug solubilizing agent. In this specific hypothetical case, the solubilizing agent increases the drug solubility by a factor of 9 (SRdrug = 9) and all three 1:1 cocrystals have increased solubility by a factor of 3 at the same solubilizing agent concentration. According to equation (1), thus .

Figure 2.

Solubility values for a drug and three 1:1 cocrystals of that drug in aqueous buffer (blue) and in the presence of a solubilizing agent (red). All cocrystals are more soluble than the drug in buffer, but not in the solubilizing agent. For cocrystal 1, the solubility advantage over drug in aqueous buffer is not maintained in the presence of solubilizing agent.

Another important observation from Figure 2 is that even though all three cocrystals are more soluble than the drug in the absence of a solubilizing agent, not all cocrystals have a solubility higher than the drug in the presence of the solubilizing agent: Scocrystal1,T < Sdrug,T, Scocrystal2,T = Sdrug,T, and Scocrystal3,T > Sdrug,T. Preferential drug solubilization in the presence of a drug solubilizing agent can lead to a cocrystal transition point at which Scocrystal,T = Sdrug,T. Above the transition point, a cocrystal that is more soluble than the drug in aqueous buffer becomes less soluble. Thus, cocrystal 2 is at the transition point, whereas cocrystals 1 and 3 are above and below the transition point, respectively. We have previously investigated the nature of cocrystal transition points for a series of drugs and cocrystals in the presence of conventional synthetic surfactants and lipids7–12. Excellent correlations were observed between the drug solubilization provided by the solubilizing agents and the transition points. The higher the solubilization of the drug by the solubilizing agent, the lower the concentration of the solubilizing agent required to achieve the transition point (CSC).

The FeSSIF media used in this study is an accepted way to simulate the higher concentrations of solubilizing agents present in the gastrointestinal tract in the “fed” state16, 29. A cocrystal tested in-vivo could potentially be exposed to a wide range of surfactant concentrations, from zero surfactant if the cocrystal is dosed suspended in a buffer solution, to the surfactant levels in FaSSIF (fasted state simulated intestinal fluid) or to the higher concentrations in FeSSIF. Physiologically relevant surfactants can increase drug solubilities by orders of magnitude, compared to the solubility measured in aqueous solution. For example, if drug solubilization was increased 100 to 1000 times in surfactant media, one would expect cocrystals of these drugs to have solubilization ratios in such media that are at least an order of magnitude lower than the drug ( to ).

The influence of physiologically relevant surfactants on drug and cocrystal solubilities will be analyzed in the results section. The increase in drug solubilization in FeSSIF compared to buffer (SRdrug) will be measured and the ability of this limited yet experimentally accessible data obtained from simple drug solubility measurements will be used to characterize the impact of FeSSIF on cocrystal solubility using equation 3. The insight from this analysis can play an important role in the design of effective strategies for utilizing cocrystals in solid oral dosage forms.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Cocrystal constituents

Anhydrous carbamazepine form III (CBZ), anhydrous indomethacin form γ (IND) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) and used as received. Anhydrous piroxicam form I was received as a gift from Pfizer (Groton, CT) and used as received. Anhydrous danazol was received as a gift from Renovo Research (Atlanta, GA) and used as received.

Anhydrous saccharin (SAC), 4-aminobenzoic acid (4ABA), and salicylic acid (SLC), were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) and used as received. Anhydrous 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (HBA) was purchased from Acros Organics (Pittsburgh, PA) and used as received. Anhydrous vanillin was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ) and used as received. Carbamazepine dihydrate (CBZ (H)), piroxicam monohydrate (PXC (H)), and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid monohydrate (HBA (H)) were prepared by slurrying CBZ, PXC, and HBA in deionized water for at least 24 hours. All crystalline drugs and coformers were characterized by X-ray power diffraction (XRPD) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) before carrying out experiments.

Solvents and buffer components

Ethyl acetate and ethanol were purchased from Acros Organics (Pittsburgh, PA) and used as received, and HPLC grade methanol and acetonitrile were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Trifluoroacetic acid spectrophometric grade 99% was purchased from Aldrich Company (Milwaukee, WI) and phosphoric acid ACS reagent 85% was purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Water used in this study was filtered through a double deionized purification system (Milli Q Plus Water System) from Millipore Co. (Bedford, MA).

FeSSIF and acetate buffer were prepared using sodium taurocholate (NaTC) purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO), lecithin purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), sodium hydroxide pellets (NaOH) purchased from J.T. Baker (Philipsburg, NJ), and acetic acid and potassium chloride (KCl) purchased from Acros Organics (Pittsburgh, PA).

Methods

FeSSIF and acetate buffer preparation

FeSSIF and acetate buffer were prepared according to the protocol of Galia and coworkers29. Acetate buffer was prepared as a stock solution at room temperature by dissolving 8.08 g NaOH (pellets), 17.3 g glacial acetic acid and 23.748 g NaCl in 2 L of purified water. The pH was adjusted to 5.00 with 1 N NaOH and 1N HCl. FeSSIF was prepared by dissolving 0.41 g sodium taurocholate in 12.5 mL of pH 5.00 acetate buffer. 0.148 g lecithin was added with magnetic stirring at 37 °C until dissolved. The volume was adjusted to exactly 50 mL with acetate buffer.

Cocrystal synthesis

Cocrystals were prepared by the reaction crystallization method30 at 25°C. The 1:1 indomethacin-saccharin cocrystal (IND-SAC) was synthesized by adding stoichiometric amounts of cocrystal constituents (IND and SAC) to nearly saturated SAC solution in ethyl acetate. The 1:1 carbamazepine saccharin cocrystal (CBZ-SAC) was prepared by adding stoichiometric amounts of cocrystal constituents (CBZ and SAC) to nearly saturated SAC solution in ethanol. The 1:1 carbamazepine-salicylic acid cocrystal (CBZ-SLC) was prepared by adding stoichiometric amounts of cocrystal constituents (CBZ and SLC) to nearly saturated SLC solution in acetonitrile. The 2:1 carbamazepine-4-aminobenzoic acid monohydrate cocrystal (CBZ-4ABA (H)) was prepared by suspending stoichiometric amounts of cocrystal constituents (CBZ and 4ABA) in a 0.01M 4ABA aqueous solution at pH 3.9. The 1:1 piroxicam-saccharin cocrystal (PXC-SAC) was prepared by adding stoichiometric amounts of cocrystal constituents (PXC and SAC) to nearly saturated SAC in acetonitrile. The 1:1 danazol-hydroxybenxoic acid cocrystal (DNZ-HBA) was prepared by adding stoichiometric amounts of cocrystal constituents (DNZ and HBA) to nearly saturated HBA solution in ethyl acetate. The 1:1 danazol-vanillin cocrystal (DNZ-VAN) was prepared by adding stoichiometric amounts of cocrystal constituents (DNZ and VAN) to nearly saturated VAN solution in ethyl acetate. Prior to carrying out any solubility experiments, solid phases were characterized by XRPD and DSC and stoichiometry verified by HPLC. Full conversion to cocrystal was observed in 24 hours.

Solubility measurements of cocrystal constituents

Cocrystal constituent solubilities were measured in FeSSIF and pH 5.00 acetate buffer (FeSSIF without NaTC and lecithin). Solubilities of cocrystal constituents were determined by adding excess solid (drug or coformer) to 3 mL of media (FeSSIF or buffer). Solutions were magnetically stirred and maintained at 25.0 ± 0.1°C using a water bath for up to 96 h. At 24 hr intervals, 0.30 mL of samples were collected, pH of solutions measured, and filtered through a 0.45 µm pore membrane. After dilution with mobile phase, solution concentrations of drug or coformer were analyzed by HPLC. The equilibrium solid phases were characterized by XRPD and DSC.

Cocrystal solubility measurements

Cocrystal equilibrium solubilities were measured in FeSSIF and pH 5.00 acetate buffer (FeSSIF without NaTC and lecithin) at the eutectic point, where drug and cocrystal solid phases are in equilibrium with solution31,32. The eutectic point between cocrystal and drug was approached by 1) cocrystal dissolution (suspending solid cocrystal (~100 mg) and drug (~50 mg) in 3 mL of media (FeSSIF or buffer)) and by 2) cocrystal precipitation (suspending solid cocrystal (~50 mg) and drug (~100 mg) in 3 mL of media (FeSSIF or buffer) nearly saturated with coformer). In the first case, cocrystal dissolved and partially precipitated to drug solid phase, and in the second case, drug dissolved and reacted with coformer in solution to partially precipitate to cocrystal. Solutions were magnetically stirred and maintained at 25 ± 0.1°C using a water bath for up to 96 h. At 24 hr intervals, 0.30 mL aliquots of suspension were collected, pH was measured, before filtration through a 0.45 µm pore membrane. Solid phases were also collected at 24 hr intervals to ensure the sample was at the eutectic point (confirmed by presence of both drug and cocrystal solid phases and constant [coformer] and [drug] solution concentrations). After dilution of filtered solutions with mobile phase, drug and coformer concentrations were analyzed by HPLC. The equilibrium solid phases were characterized by XRPD and DSC.

The cocrystal stoichiometric solubility was calculated from measured total eutectic concentrations of drug and coformer ([drug]T,eu and [coformer]T,eu) according to the following equations for 1:1 and 2:1 cocrystals31:

| (8) |

| (9) |

This method of calculating the stoichiometric solubility of cocrystals from equilibrium solubility measurements under nonstoichiometric conditions is well established in the literature7–10,31–33.

X-ray powder diffraction

X-ray powder diffraction diffractograms of solid phases were collected on a benchtop Rigaku Miniflex X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Danverse, MA) using Cu Kα radiation (λ= 1.54Å), a tube voltage of 30 kV, and a tube current of 15 mA. Data were collected from 5 to 40° at a continuous scan rate of 2.5°/min.

Thermal analysis

Solid phases collected during solubility studies were dried at room temperature and analyzed by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using a TA instrument (Newark, DE) 2910MDSC system equipped with a refrigerated cooling unit. DSC experiments were performed by heating the samples at a rate of 10 °C/min under a dry nitrogen atmosphere. A high purity indium standard was used for temperature and enthalpy calibration. Standard aluminum sample pans were used for all measurements.

High performance liquid chromatography

Solution concentrations were analyzed by a Waters HPLC (Milford, MA) equipped with an ultraviolet-visible spectrometer detector. For the IND-SAC and CBZ-SAC, CBZ-SLC, CBZ-4ABA (H) cocrystals and their components, a C18 Thermo Electron Corporation (Quebec, Canada) column (5µm, 250 × 4.6 mm) at ambient temperature was used. For the IND-SAC cocrystal, the injection volume was 20 µl and analysis conducted using an isocratic method with a mobile phase composed of 70% acetonitrile and 30% water with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Absorbance of IND and SAC were monitored at 265 nm. For the CBZ cocrystals, the injection volume was 20 µl and analysis conducted using an isocratic method with a mobile phase composed of 55% methanol and 45% water with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Absorbance was monitored as follows:

CBZ and 4ABA at 284 nm, SAC at 265 nm, and SLC at 303 nm. For the PXC-SAC, DNZ-HBA, and DNZ-VAN cocrystals and their components, a C18 Waters Atlantis (Milford, MA) column (5 µM 250 × 6 mm) at ambient temperature was used. For PXC-SAC, the injection volume was 20 µL and analysis was conducted using an isocratic method with a mobile phase composed of 70% methanol and 30% water with 0.3% phosphoric acid and a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Absorbance of PXC was monitored at 340 nm and SAC at 240 nm. For the DNZ cocrystals, the injection volume was 20 µL in FeSSIF experiments, and 100 µL in buffer experiments due to the extremely low solubility of DNZ in aqueous solutions. Analysis was conducted using an isocratic method composed of 80% methanol and 20% water with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Absorbance of DNZ was monitored at 285 nm, HBA at 242 nm, and VAN at 300 nm. For all cocrystals, the Waters’ operation software Empower 2 was used to collect and process data.

Results

Cocrystal solubilization in FeSSIF

Solubilization ratios in FeSSIF and buffer for cocrystals and theirs constituent drugs are shown in Figure 3. Results indicate that cocrystals and drugs are solubilized to different extents in FeSSIF. Drugs are solubilized to a greater extent than cocrystals in FeSSIF, as indicated by SRdrug values that are higher than SRcocrystal as expected from equation 3. Such behavior is mainly due to the preferential solubilization of drug over coformer. The ionization contribution to SR appears to be small for this set of cocrystals based on the observed pH variation for the systems studied (drug and cocrystals in FeSSIF and buffer) (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Solubilization ratios in FeSSIF for cocrystals and constituent drugs at 25°C and experimental pH values indicated in Table 2. Error bars represent standard errors of measurements.

Table 2.

Experimentally determined and predicted SRcocrystal values from measured SRdrug values in FeSSIF and buffer with initial pH of 5.00.

| Cocrystal | SRdrug, expa |

pHb FeSSIF |

pHb buffer |

SRcocrystal, predc |

SRcocrystalcexpd | pHb FeSSIF |

pHb buffer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBZ-SAC (1:1) |

1.8 ± 0.1 | 4.86±0.05 | 4.95±0.01 | 1.3 | 1.03±0.04 | 3.11±0.02 | 3.08±0.03 |

| CBZ-SLC (1:1) |

1.8 ± 0.1 | 4.86±0.05 | 4.95±0.01 | 1.3 | 1.33±0.05 | 4.29±0.02 | 4.37±0.02 |

| CBZ-4ABA (H) (2:1) |

1.8 ± 0.1 | 4.86±0.05 | 4.95±0.01 | 1.5 | 1.49±0.06 | 4.94±0.02 | 4.84±0.03 |

| PXC-SAC (1:1) |

2.0 ± 0.2 | 5.02±0.02 | 4.98±0.01 | 1.4 | 1.40±0.03 | 3.79±0.02 | 3.64±0.02 |

| IND-SAC (1:1) |

16 ± 1 | 4.98±0.06 | 4.96±0.03 | 4.0 | 4.5±0.3 | 3.65±0.05 | 3.66±0.02 |

| DNZ-HBA (1:1) |

766 ± 80 | 5.01±0.05 | 4.96±0.01 | 27 | 23±3 | 4.46±0.06 | 4.47±0.04 |

| DNZ-VAN (1:1) |

766 ± 80 | 5.01±0.05 | 4.96±0.01 | 27 | 24±4 | 5.00±0.01 | 4.96±0.01 |

Experimentally measured in absence of coformer.

pH at equilibrium.

Predicted from experimental SRdrug values using equation (1) for 1:1 cocrystals and (2) for 2:1 cocrystals.

Determined from Scocrystal measurement at eutectic points, extrapolated to stoichiometric conditions according to equations (8) and (9) in the methods section.

For the four drugs studied, SRdrug was as high as 766 (DNZ) and as low as 1.8 (CBZ), whereas the associated SRcocrystal values ranged from about 24 (DNZ cocrystals) to about 1.3 (CBZ cocrystals). High values of SRdrug resulted in large reductions in SRcocrystal (766 vs 24 for DNZ and its cocrystals). Low SRdrug values corresponded with SRcocrystal values that were much closer to SRdrug (1.8 vs 1.3 for CBZ and its cocrystals). The observed SRcocrystal values also appear to be in excellent agreement with estimates from the simple relationship (equation 1 or 2 depending on stoichiometry). For example for the 1:1 cocrystals of DNZ and CBZ and using equation 1

predicts SRcocrystal of 28 (experimental 23 and 24) for DNZ cocrystals and 1.3 (experimental 1.03 and 1.3) for CBZ cocrystals.

These results highlight the order of magnitude reduction in cocrystal solubilization that is possible compared to the constituent drugs. DNZ showed the largest solubilization by FeSSIF and most extreme difference in constituent drug and cocrystal solubilization among the cocrystals studied. IND-SAC also exhibited a large decrease in solubilization compared to IND. SRdrug for IND was 16 while SRcocrystal for the IND-SAC cocrystal was only 4.5.

PXC and CBZ exhibited a less pronounced decrease in SRcocrystal compared to SRdrug since these drugs are solubilized to a lower extent in FeSSIF. The SRdrug for PXC (H) was 2.0, and the SRcocrystal for PXC-SAC cocrystal was only 1.4. SRdrug for CBZ (H) was 1.8 and SRcocrystal for its cocrystals ranged from 1.03–1.33 for the 1:1 cocrystals CBZ-SAC and CBZ-SLC and 1.49 for the 2:1 cocrystal CBZ-4ABA (H).

Cocrystal and drug solubilities in FeSSIF and in buffer are plotted in Figure 4. These cocrystal solubilities were determined from equilibrium solubility measurements at eutectic points as described in the methods section and data presented in the Supporting Information. Results in Figure 4 indicate that cocrystals of the more hydrophobic drug DNZ show a large solubility advantage over the drug in buffer and that this cocrystal solubility advantage is reduced in FeSSIF. Similar trends are observed for cocrystals of the less hydrophobic drugs but the magnitude of the differences is much smaller and would have a correspondingly smaller impact on cocrystal performance in-situ compared to DNZ.

Figure 4.

Drug and cocrystal solubilities measured in FeSSIF and buffer at 25°C for (a) danazol, (b) indomethacin, (c) piroxicam, and (d) carbamazepine. The number above each FeSSIF value indicates the solubilization ratio (SR=SFeSSIF/Sbuffer). The initial pH was 5.00 in both buffer and FeSSIF. The final pH of solubility measurements in FeSSIF and buffer are as follows: DNZ (5.01±0.05 and 4.96±0.01), DNZ-VAN (5.00±0.01 and 4.96±0.01), and DNZ-HBA (4.46±0.06 and 4.47±0.01). IND (4.98±0.06 and 4.96±0.03), and IND-SAC (3.65±0.05 and 3.66±0.02). PXC (H) (5.03±0.02 and 4.98±0.01), and PXC-SAC (3.79±0.02 and 3.64±0.02). CBZ (H) (4.86±0.05 and 4.95±0.01), CBZ-4ABA (H) (4.94±0.02 and 4.84±0.03), CBZ-SLC (4.29±0.02 and 4.37±0.02), and CBZ-SAC (3.11±0.02 and 3.08±0.03).

The pH at equilibrium was often lower than the initial pH of 5.00 (the pH of FeSSIF and the aqueous buffer) by as much as 2 pH units for cocrystals of SAC. This shift in pH is not expected to influence the drug solubilization ratio under conditions where drug is nonionized, as long as the associated equilibrium parameters (such as solubilization constants, Ks) are not altered. For more accurate predictions under shifting pH and varying drug ionization conditions, the solubilization ratio dependence on pH can be taken into account.

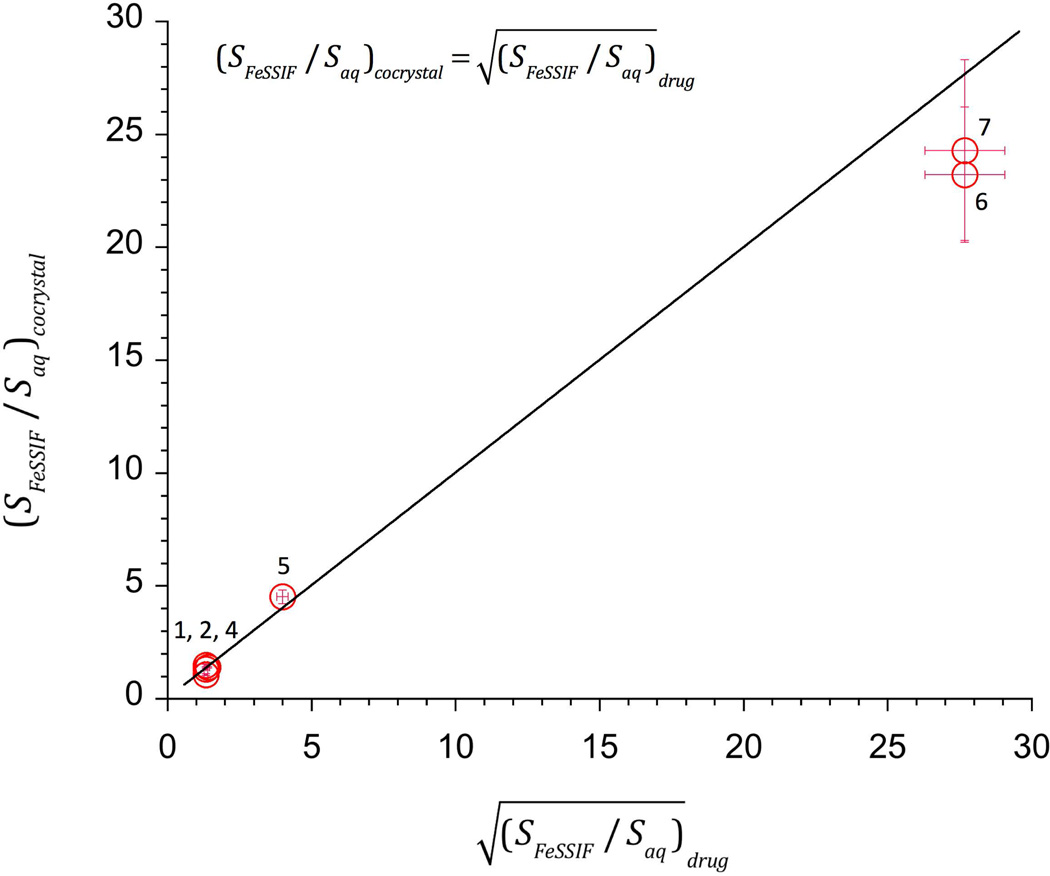

Figure 5 shows excellent agreement between predicted and experimental SRcocrystal values in FeSSIF. As predicted by the models, SRcocrystal for a given drug did not significantly vary for the systems studied (DNZ cocrystals 23 and 24 and CBZ 1:1 cocrystals 1.03 and 1.3).

Figure 5.

SRcocrystal dependence on for 1:1 cocrystals. Data points represent experimental values. Line represents the theoretical relationship according to equation (1). Numbers refer to cocrystals in Table 1.

The simple relationships used in these calculations were derived from the more rigorous solubility equations for cocrystal and drug that consider cocrystal Ksp and the pKa and Ks values of cocrystal constituents under the assumption that coformer Ks is negligible. Calculating the extent of solubilization, or solubility increase for a cocrystal at a desired surfactant concentration can be accomplished using the simple equations presented here (equations 1–3) if the experimentally accessible SRdrug value at the desired surfactant concentration is known.

Estimation of cocrystal solubility in FeSSIF

The actual cocrystal solubility values in FeSSIF or surfactant media can be estimated from

| (10) |

for a 1:1 cocrystal if the cocrystal solubility in aqueous solution is known. This equation is obtained from equation 1. For a 2:1 cocrystal the equation becomes

| (11) |

Predictions of Scocrystal, FeSSIF according to equations (10) and (11) are compared with measured values in Figure 6. Measured values of Scocrystal,aq were determined in this work or reported in the literature. There is good agreement between the predicted and observed cocrystal solubilities in spite of the simplicity of the models. For the set of cocrystals studied, the variability in the predicted values appears to be associated with that of the cocrystal solubility in aqueous media. The predictions show large fluctuations for the CBZ-SAC cocrystal. This may be a result of the high coformer concentrations during solubility measurements as well as the changes in pH from initial conditions leading to supersaturated conditions with respect to cocrystal. Future studies will address the sources of variability in these simple predictions.

Figure 6.

Predicted and observed cocrystal solubilities in FeSSIF. Numbers refer to cocrystals in Table 1. Cocrystal solubility predictions from equations (1) and (2) using measured drug solubilization and cocrystal solubility in aqueous solutions. Circles represent predictions with cocrystal aqueous solubilities measured in this work. Squares represent predictions with aqueous solubilities reported in reference 22 (cocrystals 1 and 5) and reference 33 (cocrystals 2 and 3).

Coformer solubilization in FeSSIF is negligible

One of the assumptions that contribute to the simplicity of the SR equations is the assertion that only the drug is solubilized by the surfactant and the coformer is not solubilized. This is referred to as ‘preferential solubilization’ of the drug. This assumption was tested by comparing coformer solubilities measured in FeSSIF and in buffer. Results (Supporting Information) show very low to negligible coformer solubilization by FeSSIF, with solubilization ratios less than 1.2. Thus the assumption of negligible coformer solubilization by FeSSIF is justified for the cocrystals studied and for use of the SR equations for prediction of SRcocrystal from SRdrug.

Discussion

The type and utility of the information obtained when using the SR equations (equations (1) and (2)) is dependent on the specific experimental data available. As an example, the SR equations will be used to evaluate the seven cocrystal containing four poorly soluble drugs that are the subject of this work, first in the absence of experimental information, then with the addition of the solubility data for only the constituent drug, and finally by adding the cocrystal solubility data in buffer. This sequential approach to investigating the impact of exposing a cocrystal to surfactant media can be applied to other cocrystals in a similar manner. The results can inform the decision-making and experimental approach used to advance cocrystals of drug development candidates.

There are assumptions that must be met for the SR equations to be applicable to a particular cocrystal system. The drug should be poorly soluble and surfactants should increase the drug solubility. The coformer in the corresponding cocrystal should be relatively water soluble and should not be solubilized by surfactants. All four of the drugs studied and their seven corresponding cocrystals are appropriate for use in the predictions of the SR equations.

In the absence of any experimental data it is a given that exposure to surfactant will increase the solubility of both the drug and cocrystal. The drug solubility will increase linearly with surfactant concentration while the cocrystal will have a lower corresponding increase in solubility. Cocrystal solubility will vary according to SRcocrystal = (SRdrug)1/2 for a 1:1 cocrystal and SRcocrystal = (SRdrug)2/3 for a 2:1 drug:coformer cocrystal. Drugs that are highly solubilized (large SRdrug) will lead to large decrease in SRcocrystal. The opposite is also true, drugs that are not well solubilized (low SRdrug) will have correspondingly smaller decreases in SRcocrystal. These trends established by an analysis of equation 3 can provide some guidance for cocrystal development even in the absence of any data. For example, equation 3 suggests that cocrystals, in general, have the potential to minimize food effects. A higher cocrystal solubility at low surfactant concentrations can result in higher bioavailability compared to the poorly soluble form of the drug, but at higher surfactant concentrations the square root dependence of cocrystal solubility will still maintain high bioavailability but limit the solubility increase of the cocrystal and thus limit the high variability in bioavailability that is characteristic of the food effect. Danazol has been shown to have a large food effect18 and the validated model system reported here supports the concept of investigating danazol cocrystals as an approach for avoiding this problem.

In order to begin to quantify the results from the simpler SR equations the next logical step would be to determine the solubilization ratio of the drug (SRdrug). The solubilization ratio of the cocrystal (SRcocrystal) can then be calculated directly. One of the benefits of using SR equations is that the cocrystal solubilization ratio can be calculated in the absence of any data on the cocrystals. Indeed, the SRcocrystal can even be calculated before any cocrystal of the drug is contemplated or discovered because the same SRcocrystal value applies universally to all cocrystals of the drug. This approach may be used to estimate what level of risk or benefit might be associated with developing a cocrystal before investing time and resources in a cocrystal screen. For example, the four drugs used in this study can be qualitatively categorized according to risk based on the order of magnitude of the measured value of SRdrug (Table 3). The ‘risk’ in this case is the potential for the cocrystal solubility compared to the drug solubility to vary significantly when the cocrystal is exposed to surfactant media.

Table 3.

Experimental data categorized by order of magnitude of SRdrug

| SRdrug | SRcocrystal, 1:1 | SRcocrystal, 2:1 | Impact | Drugs (SRdrug) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 10 | 1 to 3.2 | 1 to 4.7 | Low | CBZ (1.8), PXC (2.0) |

| 10 to 100 | 3.2 to 10 | 4.7 to 21.9 | Medium | IND (16) |

| >100 | >10 | >21.9 | High | DNZ (766) |

SRdrug of 766 for danazol (DNZ) is high, indomethacin (IND) is medium at 16, piroxicam (PXC) is low at 2.0, and carbamazepine (CBZ) is also low at 1.8. The high SRdrug value of 766 for DNZ results in significantly lower SRcocrystal values of 23 to 24, and the large difference in SRdrug and SRcocrystal would be expected to have a correspondingly large impact on the behavior of the cocrystal in FeSSIF. On the other hand, the low SRdrug value of 1.8 for CBZ results in very similar SRcocrystal values of 1.03 to 1.49 and thus the solubilization of both CBZ and the CBZ cocrystals are quite similar in both buffer and FeSSIF. There is a significantly lower risk with exposure of CBZ cocrystals to surfactant media compared to DNZ cocrystals.

The values of SRdrug and SRcocrystal indicate the magnitude of change in drug and cocrystal solubility in the presence of a surfactant, but they do not indicate how soluble the cocrystal is relative to the drug in the presence or absence of surfactant. In order to quantify the solubility of the cocrystal in surfactant media an additional piece of data is required. The simplified equations can be rearranged by solving for the solubility of the cocrystal in the surfactant media (Equation 10). Calculating Scocrystal,T requires a value for the solubility of the cocrystal in buffer (Scocrystal,aq) in addition to the data used to determine SRdrug. Measuring the cocrystal solubility can be accomplished as previously described12 and the cocrystal solubility in the presence of the surfactant, Scocrystal,T can be calculated at the same surfactant concentration used to determine SRdrug.

The magnitude of the solubility difference between drug and cocrystal in buffer and in FeSSIF has been calculated using equations (10) and (11) for the seven cocrystals in this study. All seven cocrystals have cocrystal solubility values that are higher than the drug solubility in FeSSIF and thus they maintain their solubility advantage over the constituent drug in both buffer and FeSSIF. The solubility advantage refers to how much more soluble the cocrystal is compared to the drug. Maintaining this solubility advantage in-vivo is essential if the reason for investigating a cocrystal is bioavailability improvement.

The relationship between SRdrug and SRcocrystal in buffer and in FeSSIF is critical to anticipate the effect drug solubilizing media on the cocrystal solubility advantage. For example, with danazol, a large SRdrug of 766 results in a smaller SRcocrystal of 24. This corresponds to a large solubility advantage in buffer of 393 times DNZ-VAN in buffer and a smaller solubility advantage of 13 times in FeSSIF. These values are calculated from experimentally determined solubilities (Supporting Information). With carbamazepine, a relatively small SRdrug of 1.8 results in a small SRcocrystal of 1.3 for CBZ-SLC. This corresponds to a solubility advantage in buffer of 12 times and in FeSSIF of 9 times. This behavior can lead to a reversal in the cocrystal solubility advantage over drug for some systems, as previously shown for pterostilbene in a lipid-based formulation12, 34.

The cocrystal behavior in FeSSIF and the SR equations presented here can be generalized to other drug solubilizing media. The ability to determine the cocrystal solubility in different formulations can guide the development of enabling cocrystal formulations, by limiting the amount of empirical effort required to identify and optimize a suitable formulation.

Conclusions

This work demonstrates that the extent of solubilization in FeSSIF is different for cocrystals and their constituent drugs. Simplified equations allow for the quantitative prediction of cocrystal solubilization ratios based only on the solubilization ratio of drug, with calculated values in excellent agreement with observed values. For 1:1 cocrystal, the cocrystal solubilization ratio can be obtained from the square root of the drug solubilization ratio. The decrease in SRcocrystal in FeSSIF compared to SRdrug ranges from 24 fold for the DNZ cocrystals to about 2 fold or less for the CBZ cocrystals. Large decreases in SRcocrystal over SRdrug for cocrystals of the more hydrophobic drugs is a result of the higher drug solubilization provided by FeSSIF. This finding has important implications for poorly soluble, lipophilic drugs that show large food effect, like DNZ. Cocrystals of BCS Class II (low solubility/high permeability) drugs like DNZ are solubilized to a lesser extent than the constituent drugs, which can lead to smaller differences between fed and fasted state solubilities. For these drugs, cocrystallization may be a promising approach to diminish food effects while simultaneously increasing overall bioavailability. The presented models can be used with drug solubilization descriptors that are measured independently or reported in the literature to predict SRcocrystal and cocrystal solubility. The hope is that these simple yet realistic models can support cocrystal development by predicting cocrystal characteristics that influence cocrystal performance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01GM107146. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We also gratefully acknowledge partial financial support from the AFPE Pre-doctoral Fellowship in Pharmaceutical Sciences, as well as the Gordon and Pamela Amidon Fellowship in Pharmaceutics, Chhoutubhai and Savitaben Patel Fellowship, Everett Hiestand Scholarship Fund, Fred Lyons Jr. Fellowship, Lilly Endowment Pharmacy Fellowship, Norman Weiner Graduate Scholarship Fund, and the Upjohn Fellowship in Pharmaceutics from the College of Pharmacy at the University of Michigan.

Abbreviations and terms

See Table 1 for cocrystal and drug abbreviations

- SR

solubilization ratio, SR≡ST/Saq

- ST

total solubility in media with solubilizing agents, ST = Saq + Ss

- Saq

aqueous solubility at a given pH, Saq = Snonionized,aq + Sionized,aq

- Ss

solubility by solubilizing agents, Ss = Snonionized,s + Sionized,s

- SRcocrystal

solubilization ratio for cocrystal, (ST/Saq)cocrystal

- SRdrug

solubilization ratio for drug, (ST/Saq)drug

- Scocrystal,aq

cocrystal solubility in aqueous media

- Scocrystal,T

cocrystal solubility in solubilizing agent media

- Sdrug,aq

drug solubility in aqueous media

- Sdrug,T

drug solubility in solubilizing agent media

- Scocrystal,FeSSIF

cocrystal solubility in FeSSIF

- CSC

critical stabilization concentration

- CMC

critical micellar concentration

- S*

solubility at which both drug and cocrystal have equal solubilities

- FeSSIF

fed state simulated intestinal fluid

- Ksp

solubility product

- Ks

solubilization constant

- [M]

micellar surfactant concentration

- Ka

dissociation constant

- API

active pharmaceutical ingredient

- CF

coformer

References

- 1.Cheney ML, Weyna DR, Shan N, Hanna M, Wojtas L, Zaworotko MJ. Coformer Selection in Pharmaceutical Cocrystal Development: a Case Study of a Meloxicam Aspirin Cocrystal That Exhibits Enhanced Solubility and Pharmacokinetics. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;100(6):2172–2181. doi: 10.1002/jps.22434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AJ, Kavuru P, Wojtas L, Zaworotko MJ, Shytle RD. Cocrystals of Quercetin with Improved Solubility and Oral Bioavailability. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2011;8(5):1867–1876. doi: 10.1021/mp200209j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung MS, Kim JS, Kim MS, Alhalaweh A, Cho W, Hwang SJ, Velaga SP. Bioavailability of indomethacin-saccharin cocrystals. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;62(11):1560–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickey MB, Peterson ML, Scoppettuolo LA, Morrisette SL, Vetter A, Guzman H, Remenar JF, Zhang Z, Tawa MD, Haley S, Zaworotko MJ, Almarsson O. Performance comparison of a co-crystal of carbamazepine with marketed product. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;67(1):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bak A, Gore A, Yanez E, Stanton M, Tufekcic S, Syed R, Akrami A, Rose M, Surapaneni S, Bostick T, King A, Neervannan S, Ostovic D, Koparkar A. The co-crystal approach to improve the exposure of a water-insoluble compound: AMG 517 sorbic acid co-crystal characterization and pharmacokinetics. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2008;97(9):3942–3956. doi: 10.1002/jps.21280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNamara DP, Childs SL, Giordano J, Iarriccio A, Cassidy J, Shet MS, Mannion R, O'Donnell E, Park A. Use of a glutaric acid cocrystal to improve oral bioavailability of a low solubility API. Pharm Res. 2006;23(8):1888–1897. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang N, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Engineering Cocrystal Solubility, Stability, and pH(max) by Micellar Solubilization. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;100(12):5219–5234. doi: 10.1002/jps.22725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang N, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Engineering cocrystal thermodynamic stability and eutectic points by micellar solubilization and ionization. Crystengcomm. 2011;13(17):5409–5422. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang N, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Effect of Micelliar Solubilization on Cocrystal Solubility and Stability. Crystal Growth & Design. 2010;10(5):2050–2053. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy L. Engineering Cocrystal and Cocrystalline Salt Solubility by Modulation of Solution Phase Chemistry. University of Michigan (Doctoral Dissertation) 2013 Retrieved from Deep Blue. ( http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/98067). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy L, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. A Rational Approach for Surfactant Selection to Modulate Cocrystal Solubility and Stability. Poster presentation at the 2010 AAPS Annual Meeting and Exposition; November 14–18, 2010; New Orleans, LA. 2010. Poster R6072. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipert MP, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Cocrystal transition points: Role of cocrystal solubility, drug solubility, and solubilizing agents. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charman WN, Porter CJH, Mithani S, Dressman JB. Physicochemical and physiological mechanisms for the effects of food on drug absorption: The role of lipids and pH. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86(3):269–282. doi: 10.1021/js960085v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courtney R, Wexler D, Radwanski E, Lim J, Laughlin M. Effect of food on the relative bioavailability of two oral formulations of posaconazole in healthy adults. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2004;57(2):218–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kostewicz ES, Brauns U, Becker R, Dressman JB. Forecasting the oral absorption behavior of poorly soluble weak bases using solubility and dissolution studies in biorelevant media. Pharm Res. 2002;19(3):345–349. doi: 10.1023/a:1014407421366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwebel HJ, van Hoogevest P, Leigh MLS, Kuentz M. The apparent solubilizing capacity of simulated intestinal fluids for poorly water-soluble drugs. Pharm Dev Technol. 2011;16(3):278–286. doi: 10.3109/10837451003664099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mithani SD, Bakatselou V, TenHoor CN, Dressman JB. Estimation of the increase in solubility of drugs as a function of bile salt concentration. Pharm Res. 1996;13(1):163–167. doi: 10.1023/a:1016062224568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sunesen VH, Vedelsdal R, Kristensen HG, Christrup L, Mullertz A. Effect of liquid volume and food intake on the absolute bioavailability of danazol, a poorly soluble drug. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2005;24(4):297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charman WN, Rogge MC, Boddy AW, Barr WH, Berger BM. Absorption of danazol after administration to different sites of the gastrointestinal-tract and the relationship to single-peak and double-peak phenomena in the plasma profiles. J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;33(12):1207–1213. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb03921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winstanley PA, Orme MLE. The effects of food on drug bioavailability. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1989;28(6):621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newton DW, Kluza RB. pKa values of medicinal compounds in pharmacy practice. Drug Intelligence & Clinical Pharmacy. 1978;12(9):546–554. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alhalaweh A, Roy L, Rodriguez-Hornedo N, Velaga SP. pH-Dependent Solubility of Indomethacin-Saccharin and Carbamazepine-Saccharin Cocrystals in Aqueous Media. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2012;9(9):2605–2612. doi: 10.1021/mp300189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson RA, Biggs AI. The ionization constants of para-aminobenzoic acid in aqueous solution at 25-degrees-c. Aust J Chem. 1957;10(2):128–134. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernhard E, Zimmermann F. Contribution to the Understanding of Oxicam Ionization-Constants. Arzneimittel-Forschung/Drug Research. 1984;34-1(6):647–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mooney KG, Mintun MA, Himmelstein KJ, Stella VJ. Dissolution Kinetics of Carboxylic-Acids .1. Effect of Ph under Unbuffered Conditions. J Pharm Sci. 1981;70(1):13–22. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600700103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swatloski RP, Visser AE, Huddleston JG, Rogers RD. Room temperature ionic liquids as alternatives to organic solvents in liquid/liquid extraction of dilute organic contaminants. Abstr Pap Am Chem Soc. 1999;217:U881–U882. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson RA, Kiang AK. The ionization constants of vanillin and 2 of its isomers. Transactions of the Faraday Society. 1955;51(10):1398–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipert MP, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Cocrystal Solubilization and Shifting Transition Points in the Presence of Drug Solubilizers. Poster presentation at the 2014 AAPS Annual Meeting and Exposition; November 2–6, 2014; San Diego, CA. 2014. Poster W4108. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galia E, Nicolaides E, Horter D, Lobenberg R, Reppas C, Dressman JB. Evaluation of various dissolution media for predicting in vivo performance of class I and II drugs. Pharm Res. 1998;15(5):698–705. doi: 10.1023/a:1011910801212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez-Hornedo N, Nehru SJ, Seefeldt KF, Pagan-Torres Y, Falkiewicz CJ. Reaction crystallization of pharmaceutical molecular complexes. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2006;3(3):362–367. doi: 10.1021/mp050099m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Good DJ, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Solubility Advantage of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals. Crystal Growth & Design. 2009;9(5):2252–2264. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Good DJ, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Cocrystal Eutectic Constants and Prediction of Solubility Behavior. Crystal Growth & Design. 2010;10(3):1028–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bethune SJ, Huang N, Jayasankar A, Rodriguez-Hornedo N. Understanding and Predicting the Effect of Cocrystal Components and pH on Cocrystal Solubility. Crystal Growth & Design. 2009;9(9):3976–3988. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh S, Seadeek C, Andres P, Zhang H, Nelson J. Development of Lipid-Based Drug Delivery System (LBDDS) to Further Enhance Solubility and Stability of Pterostilbene Cocrystals. Poster presentation at the 2013 AAPS Annual Meeting and Exposition; November 10–14, 2013; San Antonio, TX. 2013. Poster W5296. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.