Abstract

The study of retinal hemodynamics plays an important role to understand the onset and progression of diabetic retinopathy which is a leading cause of blindness in American adults. In this work, we developed an interactive retinal analysis tool to quantitatively measure the blood flow velocity (BFV) and blood flow rate (BFR) in the macular region using the Retinal Function Imager (RFI-3005, Optical Imaging, Rehovot, Israel). By employing a high definition stroboscopic fundus camera, the RFI device is able to assess retinal blood flow characteristics in vivo even in the capillaries. However, the measurements of BFV using a user-guided vessel segmentation tool may induce significant inter-observer differences and BFR is not provided in the built-in software. In this work, we have developed an interactive tool to assess the retinal BFV as well as BFR in the macular region. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) data from commercially available devices were registered with the RFI image to locate the fovea accurately. The boundaries of the vessels were delineated on a motion contrast enhanced image and BFV was computed by maximizing the cross-correlation of pixel intensities in a ratio video. Furthermore, we were able to calculate the BFR in absolute values (μl/s) which other currently available devices targeting the retinal microcirculation are not yet capable of. Experiments were conducted on 122 vessels from 5 healthy and 5 mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) subjects. The Pearson's correlation of the vessel diameter measurements between our method and manual labeling on 40 vessels was 0.984. The intraclass correlation (ICC) of BFV between our proposed method and built-in software were 0.924 and 0.830 for vessels from healthy and NPDR subjects, respectively. The coefficient of variation between repeated sessions was reduced significantly from 22.5% in the RFI built-in software to 15.9% in our proposed method (p<0.001).

Keywords: Hemodynamics, retina, blood flow rate, blood flow velocity, vessel segmentation, optical coherence tomography, retinal function imager, diabetic retinopathy

Introduction

As a leading cause of blindness in American adults (Mohamed et al., 2007), diabetic retinopathy (DR) is related to the damage of retinal blood vessels and retinal neuronal cell death (Barber, 2003; DeBuc, 2013; National Eye Institute, 2012). Early diagnosis of DR by retinal imaging plays an important role in arresting the progression of the disease and slowing the loss of vision. However, the disturbance of retinal hemodynamics involved in the onset and progression of DR is not yet fully understood (Kur et al., 2012; Pemp and Schmetterer, 2008)

Various techniques have been developed to assess the retinal circulation, including video fluorescein angiography (Arend et al., 1995), ultrasound flowmetry (Bohdanecka et al., 1999), laser speckle flowgraphy (Sugiyama et al., 2010), retinal vessel analyzer (Garhofer et al., 2010), color Doppler imaging (Harris et al., 1998; Stalmans et al., 2011), laser Doppler velocimetry (Riva et al., 1979) and scanning laser Doppler flowmetry (Petrig et al., 1999; Riva, 2001; Kimura et al., 2003; Nagaoka et al., 2004; Polska et al., 2003). However, these methods all suffered from the drawbacks of either being invasive, having high variability or only providing the measurement of the larger retinal vessels while the capillary hemodynamics play a vital role in tissue oxygenation.

By employing a high definition stroboscopic fundus camera, the Retinal Function Imager (RFI-3005, Optical Imaging, Rehovot, Israel) is able to assess retinal blood flow characteristics in vivo to the resolution of single red blood cells moving through capillaries (Nelson et al., 2005) using a non-invasive approach. Under red-free illumination, the retinal blood flow velocity (BFV) is calculated by using cross-correlation matching to determine the relative offset of path segments in sequential images that contain approximately the same pattern of moving blood cells. (Izhaky et al., 2009) Moving red blood cells provide the contrast between adjacent frames and a noninvasive capillary perfusion map (nCPM) is generated without the need of injection of a contrast agent. The RFI built-in software provides a user-guided vessel tracking tool, which traces the mouse cursor movement controlled by the operator. With the input of user defined fovea location, the vessel type (artery or vein) is identified and the retinal BFV is calculated automatically. If the coefficient of variation (COV) of BFV value in multiple sessions is greater than 45%, the labeled vessel is invalid and is hence excluded from the final analysis (Izhaky et al., 2009; Optical Imaging, 2010). Several studies have been conducted using the RFI built-in software in DR (Burgansky-Eliash et al., 2013, 2010; Landa et al., 2011) and various other pathologies. (Barak et al.; Beutelspacher et al., 2011; Böhni et al., 2015; Burgansky-Eliash et al., 2014; Landa and Rosen, 2010)

Despite the promising potential of the RFI, there are a few drawbacks in the built-in analysis software of our current research model (RFI 3005) that could impair the accuracy of the hemodynamic measurements. First, the segmentation of the vessel depends on the operator's cursor movement, which may, in our experience, induce significant inter-observer difference. Second, the location of the fovea is also depending on the user input, which is challenging to identify accurately. Third, the diameters of the vessels are not provided and thus blood flow rate information at each vessel is not available to the end users. Finally, there is a lack of widely accepted labeling systems for the retinal vessels and hence the results from different subjects are hard to compare. The BFV changes depend on the vessel type, length, hierarchy (e.g. secondary or tertiary vessel) and distance to the fovea. Without careful control of the vessel labeling task, the results of the particular clinical studies are hard to compare and reproduce.

In this work, we introduce an interactive tool to assess the retinal BFV as well as blood flow rate (BFR) in the macular region. The boundaries of the vessels are delineated by using Dijkstra's algorithm (Dijkstra, 1959) on a motion contrast enhanced image and BFV is computed by maximizing the cross-correlation of pixel intensities in a ratio video. Furthermore, we are able to calculate the blood flow rate (BFR) in absolute values (μl/s) which other currently available devices targeting the retinal microcirculation are not yet capable of. In addition, Optical coherence tomography (OCT) data from Cirrus HD-OCT 5000 (Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) or Spectralis SD-OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Germany) are registered with the RFI image to locate the fovea accurately with the following benefits:

Accurate vessel type identification: If the starting point of a vessel is closer to the fovea, then the vessel is a vein and vice versa.

Precise tracking of functional changes: Vessels can be separated into different grids or rings in the macular region to track the functional changes more precisely;

Multimodal image analysis advantage: A link between structural features (e.g. total retinal layer thickness in map format) with the functional features, i.e. BFV and BFR may add another dimension for the understanding of retinal pathologies.

We report measurements of BFV and BFR in normal healthy as well as in pathological subjects and demonstrate how retinal hemodynamic measurements are combined with OCT measurements to yield a quantitative multimodal platform for measuring the retinal disturbances in diabetic complications. These multimodal measures in the normal retina may serve as standards against which altered retinal hemodynamics in disease states can be evaluated.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This study was approved by an Institutional Review Board at the University of Miami. Prior to enrollment informed consents were obtained according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients underwent RFI and OCT scanning at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami, FL, USA. Five eyes from four healthy control subjects and five eyes from four mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) subjects were included in this study. All study subjects underwent routine ophthalmic examination with indirect ophthalmoscopy. Healthy control subjects had no history of retinal diseases, primary or secondary glaucoma, intraocular inflammation, intraocular surgery, diabetes mellitus or uncontrolled arterial hypertension. The diagnosis of the subjects in the mild NPDR group were based on indirect fundus examination by an expert retina specialist. For both groups, ophthalmic exclusion criteria were ocular media opacity, any previous intraocular surgery except uneventful cataract extraction at least 6 months prior to enrollment and myopia of more than 6 diopters. The demographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the study subjects.

| Group | OD/OS | Age | Gender | Mean visual acuity (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | 4/1 | 46-53 | 5 Female | 1.0 |

| Mild NPDR | 3/2 | 56-68 | 4 male, 1 female | 0.56 (0.1-1.0) |

Note that all healthy subjects had a visual acuity of 1.0

Image Acquisition

The RFI system is deployed based on a standard fundus camera extended by a customized stroboscopic flash lamp system. A green (“red-free”) light with a spectrum of 548±75nm is used for illumination and the interval between consecutive flashes is typically 17.5 milliseconds. One session of RFI data consists of 8 images with a resolution of 1024×1024 pixels in an area of 4.3×4.3 mm or 7.2×7.2 mm depending on the choice of field of view (20° or 35°) during the imaging acquisition. The setting of 50° field of view is also available in the device but is unsuitable for the BFV measurement assessment as the retinal blood cells are hardly visible due to the limited resolution. In this study, all of the images were captured with the setting of 35° field of view. The heartbeats of the patient were monitored with a nail probe sensor and the image acquisition was synchronized with the cardiac cycle to neutralize the effects of pulsation on arterial blood flow velocity. After the image acquisition, the RFI built-in software generated (a) the flow movie (a.k.a. “ratio video”) through differential processing so that the motion of individual clusters of red blood cells can be followed by the human eye; and (b) the non-invasive capillary perfusion map (nCPM) was generated through analyzing the difference of pixel intensities in adjacent frames. (Izhaky et al., 2009; Nelson et al., 2005).

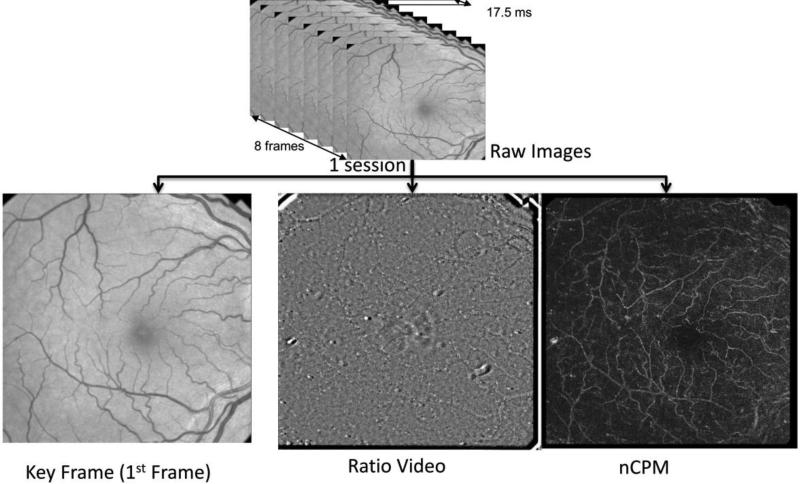

A good quality scanning session is characterized by sharp vessel borders on the raw fundus images, clear red blood cell movement along the vessels on ratio videos and a visible capillary network on the nCPM. Each subject was scanned repeatedly for 8-10 times and five good quality sessions were chosen for our proposed algorithm. In this work, each input RFI data session consisted of (a) the first frame of raw image (or Key Frame) used for registration, (b) ratio video used for BFV calculation and (c) nCPM image used for vessel tracking, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig.1. Data Structure of one RFI Session.

The raw data contains 8 fundus images captured with a stroboscopic light of 548±8.5nm flashed at every 17.5 ms.

After image registration, the built-in software provided the ratio video and non-invasive capillary perfusion map (nCPM), which revealed the blood flow information and capillary perfusion network, respectively. The above two were used as an input for our analysis system, along with a Key Frame (1st Frame).

Besides the RFI assessment, each patient was also scanned by Cirrus HD-OCT 5000 (Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc, Dublin, CA) or Spectralis SD-OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) after dilation. The volumetric data from Cirrus HD-OCT 5000 consisted of 200×200 A-scans on a 6×6 mm area while each scanning session for Spectralis SD-OCT consisted of 61×768 A-scans on an 8.9 × 8.9 mm area with the setting of Automatic Real Time (ART) equal to 10. The input OCT data were both the SLO image and the video with marked boundaries which were used for registration and thickness map calculation, respectively.

Image Analysis

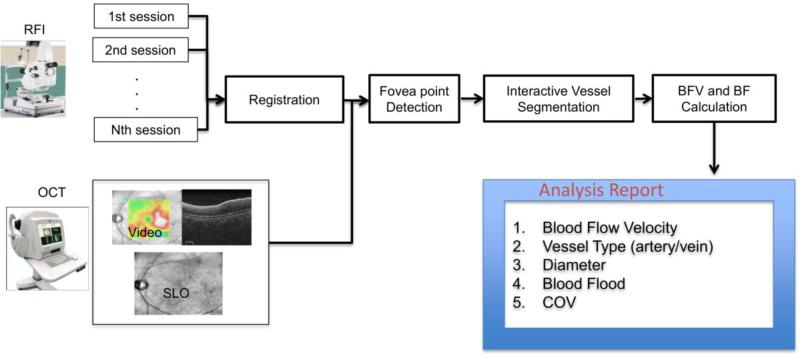

The proposed image analysis software was implemented using Matlab 2014a consisting of four main blocks, which are (a) registration, (b) fovea detection, (c) vessel tracking and (d) BFV and BFR calculation. The overview of the algorithm is illustrated in Fig. 2. For each analyzed vessel, we could automatically get the vessel type (artery or vein), vessel diameters, BFV, BFR, and coefficient of variation (COV) of BFV among sessions.

Fig. 2. System overview of our proposed image analysis method.

Multiple RFI sessions were registered using I2k Retina software (DualAlign LLC, Clifton Park, NY). OCT data were augmented to the RFI images for fovea detection. Vessel segmentation was performed and blood flow velocities (BFVs) were computed with its coefficients of variation between different sessions. Blood Flow rate (BF) was computed as the multiplication of BFV with the vessel cross sectional area.

The details of each block are explained in the following subsection.

a) Registration

First, the input RFI data sessions were registered to align the vessel structure so that the BFV and BFR could be easily analyzed simultaneously for different sessions. The registration block was implemented by incorporating I2k Retina ® software (DualAlign™ LLC, Clifton Park, NY) to register the key frames from RFI input sessions. Affine transformation was selected as layout option. (Stewart, 2009)

b) Detection of the Fovea Point Location

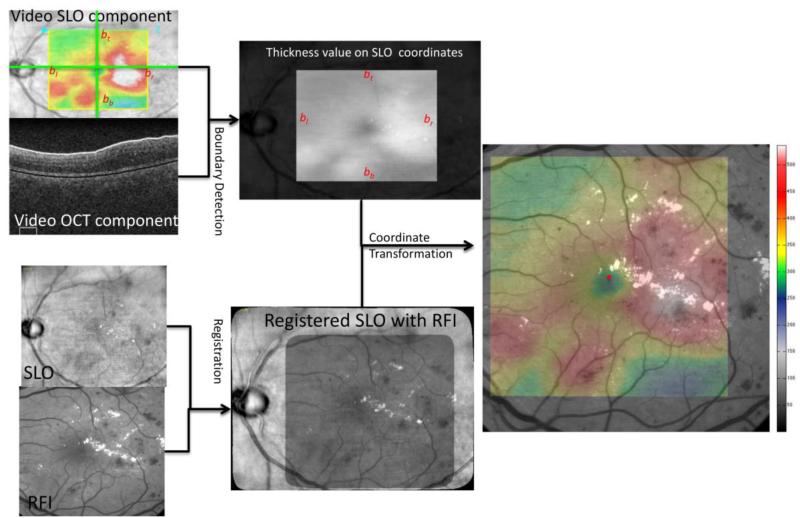

The process of fovea detection is shown in Fig. 3. Each frame in the OCT video data consists of two components, the SLO and OCT B-scan. The SLO component of the video contains a colored box representing the retinal thickness surface, which can be detected automatically by finding the borders on the color mask M defined as follows.

where R(x,y), G(x,y), and B(x,y) represents the RGB channels of the SLO image. The 1s on Mslo indicate the pixels have non-gray color and “white” region shows the corresponding location of the color box. To avoid the pitfall of possible gray color (0-150 microns) on the overlay part, morphological closing is applied to the mask M. The first 1's and the last 1's on the mask M along the vertical center scan are the top and bottom border bt and bb, respectively. Similarly, the leftmost and rightmost border bl and br can be detected.

Fig.3. Illustration of the Fovea Detection process.

The color box in the SLO component of the video is detected first and the annotated boundary in the OCT B-scan is also extracted. The SLO is aligned with the RFI key frame and the OCT thickness surface map is transformed into the RFI coordinates. The smallest retinal thickness value is determined as the fovea point location (red dot).

For each OCT B-scan (IOCT), the white boundary is corresponding to the vitreo-retinal border or Inner Limiting Membrane (ILM) and is detected by using the shortest-path graph search (Chiu et al., 2010) on the mask MILM

Similarly, Bruch's membrane is detected as the black boundary. The retinal layer thickness surface map is now reproduced and overlaid on the SLO image, which is registered with the RFI image using the I2K Retina Software. The OCT thickness surface map can be transformed into the RFI image coordinates and a similar pseudo color pattern is overlaid on the RFI image. The lowest value on the retinal thickness data is detected as the fovea point location as illustrated in Fig. 3.

(c) Vessel Tracking

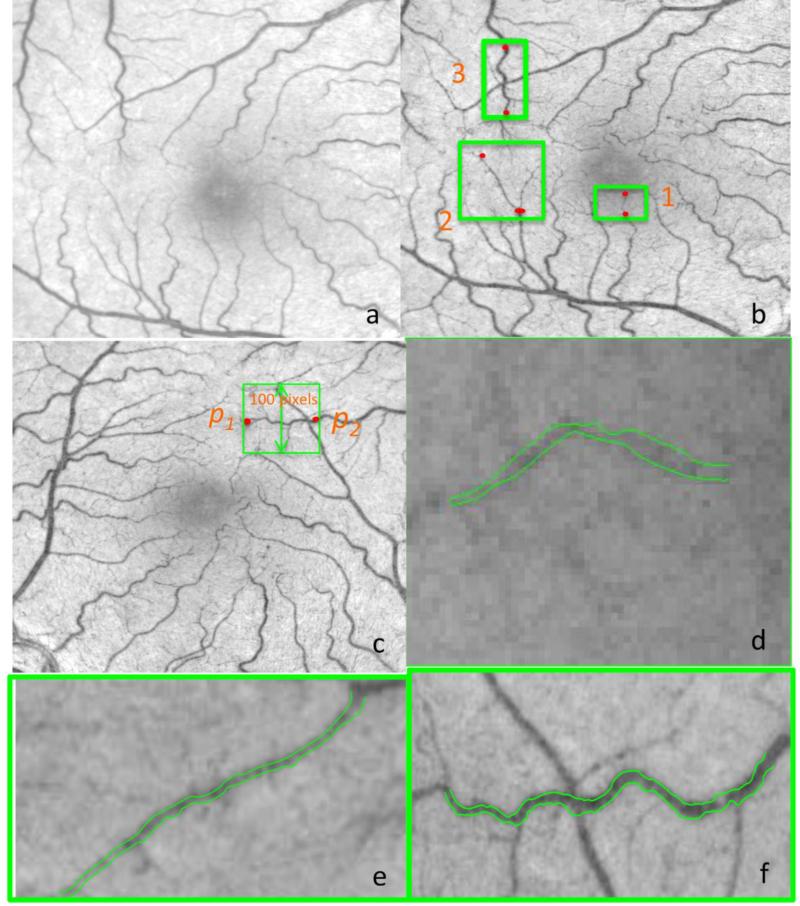

In this section, an interactive vessel tracking tool that can delineate both major and small vessels on RFI images is presented.

As the small vessels close to the fovea point have weak contrast on the key frame, the image used for segmentation denoted as Ie is defined by linearly combining the key frame with the nCPM image as

where InCPM and Ikey are the nCPM and key frame images normalized to [0,1], respectively. Because the nCPM image contains the motion contrast between 8 frames, the small vessels or even the capillaries that are hardly visible on the original fundus image can be seen clearly. Hence, the vessels near the fovea point are better visualized in the enhanced image (see Fig. 4(b)) as compared to the original fundus image in Fig. 4 (a). The vessel boundary delineation method is similar to the one proposed in Chiu et al., 2010, which detects the boundary using the short-path graph search on an edge-weighted graph. The only alteration is demonstrated in Fig. 4 (c) and explained as follows: Once the user clicks two end points, the image is rotated such that the two end points p1 and p2 are horizontally located. Assuming the vessel boundary to be segmented has smooth transitions, the rectangular region of interest is defined as:

where (xp1, yp1) and (xp2, yp2) are the user defined end points on the rotated image, and

Then, an edge-weighted graph can be constructed to detect the upper and lower boundary of the vessels. Assuming the vessel diameter is constant between two points, the diameter of the vessel is the average of the distance between the upper boundary and lower boundary. Three vessel tracking examples are shown in Fig. 4 (d), (e) and (f) which shows the boundary detection results for a capillary along with a tiny and tortuous vessel, respectively.

Fig. 4. Vessel tracking examples.

(a) Example RFI key frame obtained from a healthy subject. (b) The enhanced image is obtained by combining the key frame with the nCPM. The vessel structure near the fovea point is greatly enhanced. Three green rectangles are highlighted as regions of interest with the example vessels to be detected and the red dots are the end points clicked by the user. The vessel detection results are shown in (d), (e) and (f). (c) The enhanced image is rotated such that the end points are horizontal. All the pixels within the rectangle of 100 pixels in height are taken as the region of interest along the vessel path to be detected. (d) Vessel border detection results for the capillary in Region 1 (e) Vessel border detection results for the tiny vessel in Region 2 (f) Vessel border detection results for the tortuous vessel in Region 3.

(d) BFV and BFR Calculation

The measurement of BFV is based on the tracking of moving blood cells along the vessel centerline in the ratio video. The centerline of the vessel is defined as

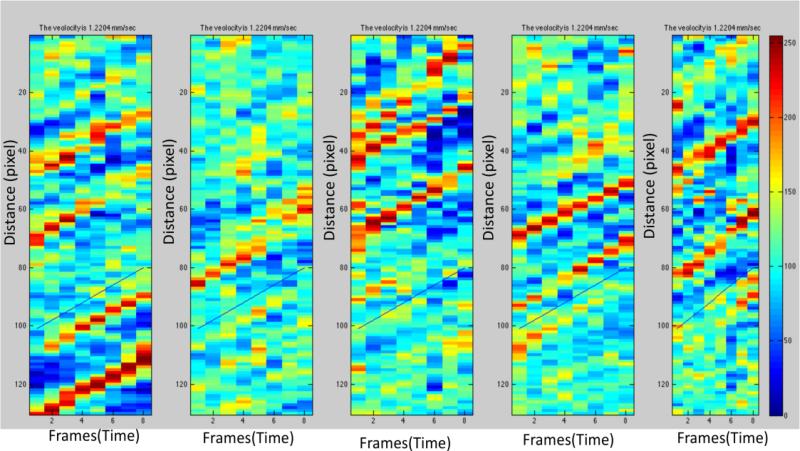

where El and Er denote the detected left and right boundaries of the vessel. Because adjacent pixels on the centerline are not uniformly distributed, intensities of the pixels along the centerline on the ratio volume are then resampled according to the path length from the starting point using linear interpolation. The example space-time diagram on five different sessions is shown in Fig. 5, where the horizontal and vertical axes denote the path distance and frame number, respectively. The BFVs are calculated by computing the gradient of “stripes”. If the gradient is positive, the red cells in the vessel are flowing from the starting point p1 towards the end point p2, otherwise, the starting and end points are p2 and p1, respectively. Once the starting and end points are determined, the vessel is identified as the vein if the starting point is closer to the fovea, as the red blood cell is moving back to the peripheral vessels. The arteries could be determined in a similar manner. In our method, the BFV is calculated by maximizing cross-correlation of intensity profiles between adjacent frames. The calculated gradients are shown as the blue line on Fig. 5. We assume that within the end points, the BFV and vessel diameter are constant along the path (i.e. assuming Poiseuille's law for steady flow (Sutera, 1993)). Hence, the BFR is computed by multiplying the BFV with the cross-sectional area. We noticed that the BFVs were not measured reliably in the vessels which were not focused sharply due to the lack of motion contrast. Hence, our custom-built algorithm allows the users to reject the unreliable sessions in each vessel so that the BFV measurements are still reliable even if some of the RFI key frames are not sharply focused. This is an added advantage as compared with the RFI built-in software as the vessels which were rejected by RFI built-in software due to the rule of COV<45% (RFI manual 2010) could be included in our methods when the unreliable sessions were excluded.

Fig.5. Blood flow velocity calculation.

The space-time diagram of five RFI sessions is shown. The BFV is calculated by maximizing the cross-correlation of intensity profiles between adjacent frames. The gradients of the annotated blue lines are the results of BFV calculation.

Experimental Setup and Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Matlab 2014a (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts, USA) and SPSS v21 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA). To verify our proposed image analysis method, two experiments were conducted as follows:

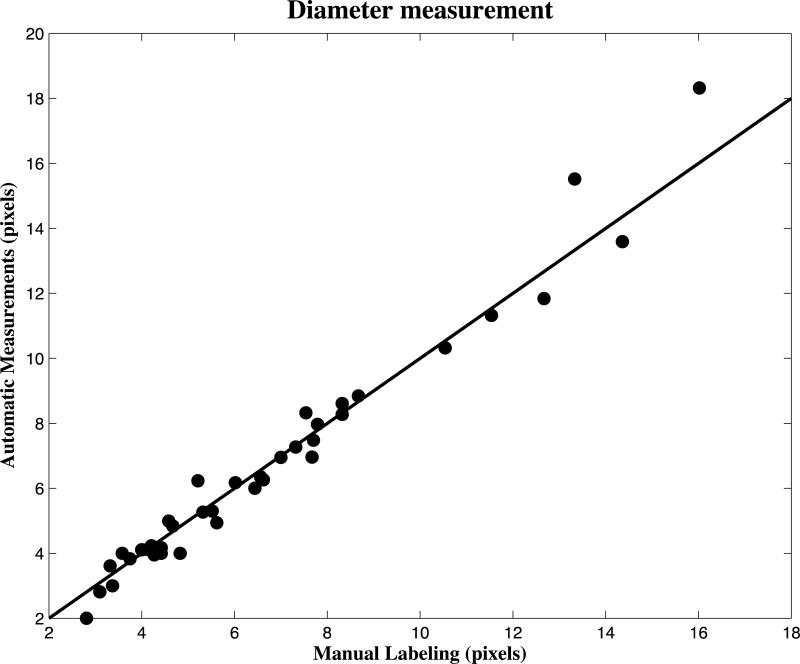

Comparison of vessel diameter measurements with manual labeling by Image J: To evaluate the result of vessel tracking by our proposed method, forty vessels with various diameters, i.e. secondary, tertiary and capillary vessels were randomly selected from ten RFI subjects. For each vessel, the diameter was measured three times with calipers in Image J, and the average of the measurements was taken as the ground truth for comparison. Pearson's correlation was used to measure the similarity between our proposed automatic measurement and the manual labeling.

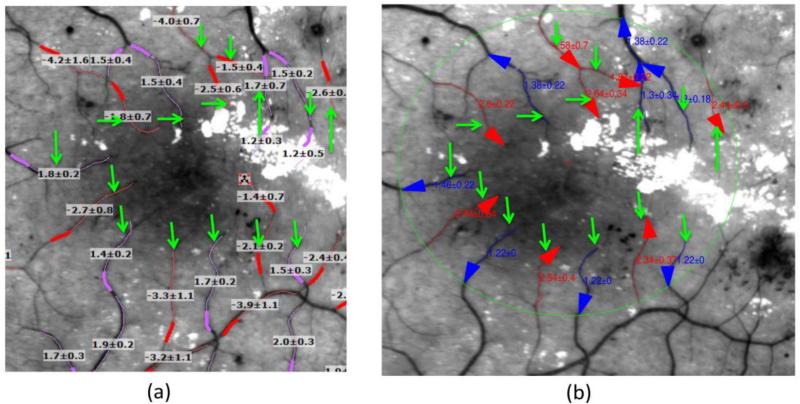

Comparison of BFV measurements with the RFI's built-in software: The built-in software of the RFI device was compared with our proposed algorithm in the same 10 subjects and the vessel labeling task was performed on the same set of sessions. The two operators for both the RFI built-in software and our proposed software were instructed to start labeling the vessel segment on the 3 mm ring centered at the fovea and stop the labeling at the branching point or the end of vessels. The vessel length was instructed to be kept in the range of 100-150 pixels. As there is no 3 mm ring visible on the RFI built-in software, the operator performed the labeling of vessels for the entire RFI images and the vessels drawn outside the ring were discarded during the comparison. There were a total of 122 vessels for pairwise comparisons from the ten subjects. An example of corresponding vessels is demonstrated in Fig. 6. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979) and Bland-Altman Plots (Altman and Bland, 1983) were used to evaluate the agreement between the BFV values measured by our method and the RFI built-in software. Two way mixed model, also known as ICC (3,1), was chosen to measure ICC in our experiment as the patients were random but the raters were fixed. Therefore, each measurement was assessed by each rater and the reliability was calculated from a single measurement. As all the RFI sessions were acquired at the same visit and synchronized with the heart cycle, the BFV values measured at each session was supposed to be the same or in good agreement. Hence, the coefficient of variation (COV) between different sessions of each subject was reported to assess the reliability of the RFI built-in software and our proposed algorithm. In both statistical analyses the level of significance was set to be 0.001 due to the high number of comparisons.

Fig. 6. Comparison of the BFV calculations between the built-in software of the RFI device and our proposed image analysis algorithm in (a) and (b), respectively.

The green arrow points to the corresponding vessel between two methods. The vessels are marked around the 3 mm ring centered at the fovea point. (a) Red and pink colors annotate the arteries and veins on the RFI image, respectively. (b) Red and blue arrows annotate the arteries and veins on RFI images in our software environment, respectively.

Results

1. Results of the comparisons between our vessel diameter measurement method and the manual labeling by Image J

A Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.984 was obtained between the proposed automatic vessel diameter method and the manual labeling. The scatterplot of our measurements is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. The scatterplot of diameter measurements obtained by manual labeling and our proposed automatic method on randomly selected 40 vessels.

The Pearson Correlation is equal to 0.984

2. Results of the comparisons between BFV measurements obtained by our proposed automatic method and the built-in software of the RFI device

The ICC results for the blood flow velocity measurements of vessels in healthy subjects and mild NPDR subjects are shown in Table 2. The BFV values measured by both methods are in good agreement for both healthy and mild NPDR subjects.

Table 2.

ICC results for vessels labeled from healthy subjects (Two way mixed, ICC(3,1))

| Group | ICC | 95% Confidence Interval |

Significance in F Fest with True Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Higher bound | |||

| Mild NPDR | .924 | .874 | .954 | .000 |

| Healthy | .830 | .735 | .893 | .000 |

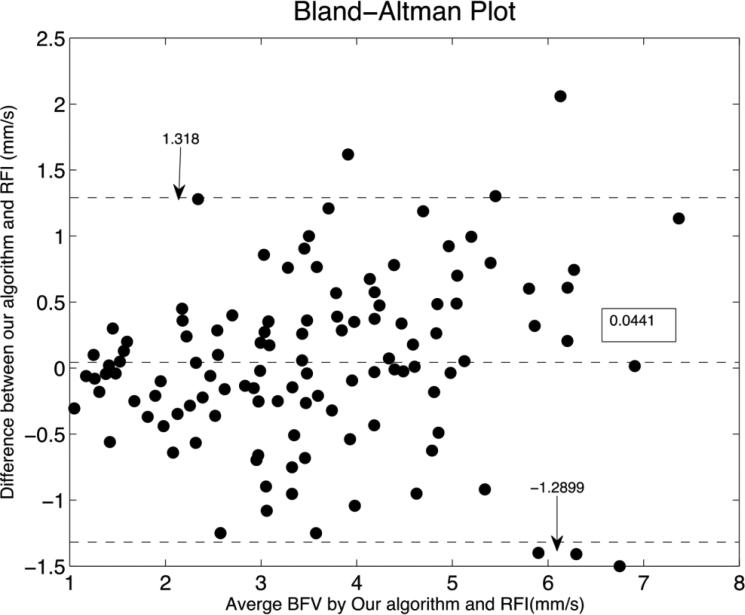

The Bland-Altman Plot of the comparisons is shown in Fig. 8. The difference between the proposed software and the RFI built-in software was small when the BFV were low (approximately below 2mm/s) and were higher above approximately 5mm/s.

Fig.8. Bland-Altman Plot of BFV measurements between the built-in software of the RFI and our proposed image analysis algorithm.

The vessels with lower BFV (below approximately 2mm/s) showed relatively smaller differences between the two methods while the differences were higher above approximately 5mm/s.

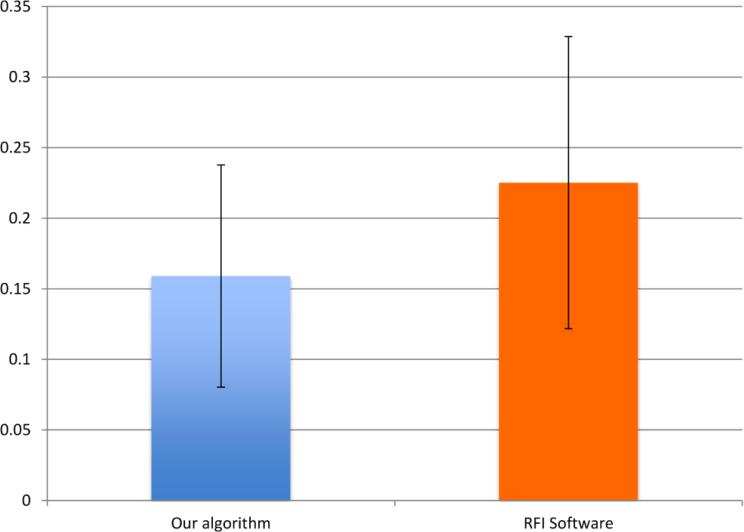

Coefficients of variations using both methods are shown in Fig. 9. The BFV measurements using our proposed method have a significant smaller COV between different sessions (p<0.001).

Fig.9. Coefficient of variation (COV) of BFV measurements between 5 RFI sessions computed by our algorithm and the RFI built-in software.

The COV value by our proposed algorithm is significantly lower (p<0.001) than the RFI built-in software.

Discussion

This paper presents an interactive image analysis algorithm that enables the assessment of functional hemodynamics information, such as BFR and BFV measures from a noninvasive fundus imaging-based device (RFI). Although the built-in software of the RFI device can calculate the BFV, the results of the analysis for each subject have high variability due to the inter-observer difference in fovea identification, vessel tracking, and vessel locations. Furthermore, the diameters of the vessels are not provided and hence BFR information remains unexploited. Our image analysis algorithm takes the key frame, ratio video and nCPM image as input and automatically computes the BFV, vessel diameter, BFR and vessel type once the users labeled the end points of the vessel. The algorithm consists of four operational blocks named as registration, fovea point detection, vessel tracking and BF calculation. As in the built-in software of the RFI, the registration block aligns the key frame using I2K Retina software so that the measurements are completed simultaneously in multiple sessions. The fovea point detection procedure takes advantage of the retinal thickness information from OCT data so that the fovea point can be located precisely. In the case when there is no OCT data or the foveal retinal structure is distorted by the macular edema, the user can manually select the fovea point based on the foveal retinal width (i.e. maximum retinal thickness nearest to the foveal reflex on the nasal and temporal side) extracted from OCT images. Note that our proposed image analysis method works with all types of OCT devices provided that the imaging modality supports the export of the SLO image and the B-Scans Video. Besides vessel type identification, the OCT data may add another dimension to the microvascular research of the retina and may provide useful insights into the diagnosis of retinal diseases. In addition, local analysis of zone specific measures is possible with our algorithm since the retina could be separated into different regions or rings (like the ETDRS regions or the 3 mm ring used in our analyses) based on the fovea location. Our current study only uses the total retinal thickness information from the built-in segmentation software of the Cirrus HD-OCT or Spectralis HRA+OCT but it can be further developed to use other devices as well for foveal width input. Thickness information from other retinal layers, such as the RNFL and photoreceptor layer could also be added to the final outputs in future work. This may facilitate a more robust non-invasive measure of presumed and definite retinal nonperfusion areas as seen on OCT-based thickness and RFI-based hemodynamic data, respectively. Therefore, the multimodal measurement advantage of our method would not only provide details of the retinal pathophysiology, but could also possibly aid as a biomarker in disease state.

Our vessel tracking block only detects the targeted vessels and measures their diameters with high accuracy after the user indicates the starting and end points of the vessels. Although various vessel segmentation techniques classify all the vessel pixels automatically as reviewed in Fraz et al., 2012, the results from existing vessel classification techniques cannot be directly used due to the lack of vessel growing path which is necessary for the construction of the space-time diagram and the BFV calculation. Numerous vessel tracking algorithms (Can et al., 1999; Gao et al., 2001; Quek and Kirbas, 2001) and image databases (DRIVE 2004, ARIA 2006) have been developed. However, these studies are customized for fundus images focused on the optic nerve and do not handle the vasculature in the fovea very well. Vessel tracking in the macular region remains challenging due to the weak contrast of tiny vessels. Our vessel tracking method employs Dijkstra's algorithm (Dijkstra, 1959) to detect vessel boundaries on a motion contrast enhanced image. The proposed vessel tracking approach works well for tortuous and even tiny vessels. Our results were in good agreement with manual labeled diameter results from image J in forty random selected vessels with a high Pearson's correlation. Similarly to the built-in software of the RFI, our BFV calculation is based on maximizing the cross-correlation of pixel intensities along the detected vessel center path (Izhaky et al., 2009). We performed a study to verify the accuracy of BFV calculation on 5 healthy and 5 mild NPDR eyes using 122 labeled vessels by two operators. The results of BFV calculations from our proposed method were in good agreement with those by the built-in software of the RFI, while the coefficient of variation between repeated scans was significantly smaller with our method. These results indicate that we have achieved a better reliability for BFV measurements compared to that of the built-in analysis software of our current research model (RFI 3005).

We noted that smaller ICCs were obtained in healthy subjects, as compared with mild NPDR, which can be explained theoretically as follows: the BFV estimate employed the same method as the delay estimation in ultra-sound imaging. Hence, higher blood flow velocity values in the healthy subjects degraded the performance of the cross-correlation maximization due to the finite vessel length [(Walker and Trahey, 1995)]. The same accuracy decreased trend was observed in the experiments conducted in the phantom eye by the RFI built-in software [(optical imaging, 2008)]. Clinically, it implies the BFV values were measured more reliably in the vessels with smaller velocity values, i.e. the retinal blood vessels of mild NPDR subject and capillaries, etc. To achieve better performance in the main vessels of healthy subjects, higher imaging frequency of the capturing device is desired. In addition, the higher ICC values obtained for the diabetic group may be related to the image quality affected by pathology and the variability of the BFV values among diabetic individuals as a result of physiological conditions.

Our work facilitates the understanding of the hemodynamics of the retina, i.e. blood flow and capillary perfusion, which has become an emerging area of research to study the onset and progression of retinal diseases. Another major development trend in this area is OCT angiography (OCTA) which does not require any dye injection, similarly to the RFI (Jia et al., 2015). In OCTA, as blood flows through vessels, the reflectance is changing with time and hence a lower correlation is observed between OCT B-Scans from the same location. The split-spectrum amplitude decorrelation method is able to visualize the vessel networks even down to the level of capillaries at different retinal layers. The currently existing imaging speed of 70,000 A-scans per seconds requires 4 seconds to produce one OCTA volume which limits the area of interest to a small field of view (3×3 mm). Motion artifacts are unavoidable in the image acquisition process and thus degrade the quality of OCTA. In contrast, the RFI can complete the acquisition process in 0.13 seconds and the nCPMs have a wider field of view (7.2×7.2 mm). Eye motion during scanning with the RFI can be easily corrected by the image registration algorithm. However, the drawback of RFI is that it does not provide information of the deep retinal layer network and it requires relatively clear ocular media, brighter flashes, and pupil dilation in order to generate good quality nCPMs due to the shorter penetration depth in green light (548nm) as compared to infrared light (840nm). In our opinion, the advantages of RFI imaging, i.e. the ultrafast image acquisition speed and the widefield nCPM capability, outweigh its drawbacks related to the lack of depth information and the need of pupil dilation.(Grinvald et al., 2004; Izhaky et al., 2009; Witkin et al., 2012)

Despite the promising results, our study has a few limitations. First, we lack a real ground truth for the comparison of vessel diameter measurements and BFV calculations. Ideally, the experiments should be conducted on a phantom to verify the accuracy of the algorithm. Unfortunately, there is no commercially available phantom customized for the RFI device. Instead, we benchmarked our results with the BFV readings from RFI built-in software, which was calibrated with a model eye simulation by fixed flow rates of human blood through a pipette of 80 micron inner diameter (optical imaging, 2008). Particularly, in this benchmark study, results suggested that the velocity determined by the RFI is slightly higher (6.5%) than the actual but highly correlated. However, a widely accepted method, such as manual labeling and the built-in software of the RFI, were used for the comparisons in our study. Second, inconsistency is a key concern related with all techniques that assess blood flow in the eye (Luksch et al., 2009). Similarly to other systems that measure retinal blood flow, one of the limitations of our study are the unknown sources of variability in the measurements. Retinal vessel diameter in an individual may change, even over a short period of time, due, for example, to the pulse cycle. However, the RFI imaging is synchronized with the patient pulse phase. Therefore, the velocity is always measured at the same certain fixed fraction of the heartbeat cycle (67% after the beginning of the systole). A previous study investigated the reproducibility of the RFI measurements and found that age, heart rate, and mean arterial pressure influence the velocity measured and should be accounted for when assessing velocity under pathological conditions (Burgansky-Eliash, et al., 2013). Another limitation is that the experiments were conducted in a relatively small sample of subjects. The measurement of BFV and BFR on more subjects and longitudinal studies are planned as a future work.

In conclusion, we have presented an interactive retinal analysis tool to quantitatively measure the blood flow velocity and blood flow rate in the macular region. An advantage of our proposed methodology is the use of a second imaging modality (OCT) to enable a more precise quantification of the functional RFI parameters. The capability to combine these different optical imaging techniques will enable an integrated view of the retinal tissue information. RFI-based studies of retinal vessels are advantageous and provide quantitative parameters that enable us to identify subtle vascular changes both in normal subjects and those with ocular and systemic risk factors with greater precision and detail. The RFI technology may hold promise for measurements of retinal abnormalities with exquisite detail using objective and quantitative functional parameters that facilitate the diagnosis of diseases and its progression as well as the optimization and management of their treatments. Future improvements in the multimodal capability of the retinal function imaging technology will prevent the use of many different invasive diagnostic retinal instruments that are currently used to obtain various hemodynamic and structural parameters in clinical settings.

Highlights.

An interactive tool to assess the retinal blood flow value and blood follow rate in the macular region was developed;

Optical coherence tomography data was registered with Retinal function imager image to locate the fovea accurately;

The boundaries of the vessels were delineated on a motion contrast enhanced image and BFV was computed by maximizing the cross-correlation of pixel intensities in a ratio video;

The coefficient of variation between repeated sessions was reduced significantly from 22.5% in the RFI built-in software to 15.9% in our proposed method (p<0.001).

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by a NIH Grant No. NIH R01EY020607, a NIH Center Grant No. P30-EY014801, by an unrestricted grant to the University of Miami from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., by a research fellowship of the Helen Keller Foundation for Research and Education and by an Eotvos Scholarship of the Hungarian Scholarship Fund. The authors would like to thank Sandra Pineda, B.S. for her assistance with the recruitment of study subjects and clinical coordination.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Measurement in Medicine : the Analysis of Method Comparison Studies. Stat. 1983;32:307–317. doi:10.2307/2987937. [Google Scholar]

- Arend O, Harris A, Sponsel WE, Remky A, Reim M, Wolf S. Macular capillary particle velocities: a blue field and scanning laser comparison. Graefe's Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1995;233:244–249. doi: 10.1007/BF00183599. doi:10.1007/BF00183599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARIA Online Retinal Image Archive. 2006 http://www.eyecharity.com/aria online/

- Barak A, Burgansky-Eliash Z, Barash H, Nelson DA, Grinvald A, Loewenstein A. The effect of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) injection on retinal blood flow velocity in patients with choroidal neovascularization. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 22:423–30. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000074. doi:10.5301/ejo.5000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber AJ. A new view of diabetic retinopathy: a neurodegenerative disease of the eye. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;27:283–290. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00023-X. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutelspacher SC, Serbecic N, Barash H, Burgansky-Eliash Z, Grinvald A, Jonas JB. Central serous chorioretinopathy shows reduced retinal flow circulation in retinal function imaging (RFI). Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:e479–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02136.x. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohdanecka Z, Orgül S, Meyer AB, Prünte C, Flammer J. Relationship between blood flow velocities in retrobulbar vessels and laser Doppler flowmetry at the optic disk in glaucoma patients. Ophthalmol. J. Int. d'ophtalmologie. Int. J. Ophthalmol. Zeitschrift f{ü}r Augenheilkd. 1999;213:145–149. doi: 10.1159/000027409. doi:27409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhni SC, Howell JP, Bittner M, Faes L, Bachmann LM, Thiel M. a, Schmid MK. Blood flow velocity measured using the Retinal Function Imager predicts successful ranibizumab treatment in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: early prospective cohort study. Eye. 2015;29:630–636. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.10. doi:10.1038/eye.2015.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgansky-Eliash Z, Barash H, Nelson D, Grinvald A, Sorkin A, Loewenstein A, Barak A. Retinal blood flow velocity in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Curr. Eye Res. 2014;39:304–11. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2013.840384. doi:10.3109/02713683.2013.840384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgansky-Eliash Z, Lowenstein A, Neuderfer M, Kesler A, Barash H, Nelson DA, Grinvald A, Barak A. The correlation between retinal blood flow velocity measured by the retinal function imager and various physiological parameters. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina. 2013;44:51–8. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20121221-13. doi:10.3928/23258160-20121221-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgansky-Eliash Z, Nelson DA, Bar-Tal OP, Lowenstein A, Grinvald A, Barak A. Reduced retinal blood flow velocity in diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2010;30:765–73. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181c596c6. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181c596c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can AH, Shen H, Turner JN, Tanenbaum HL, Roysam B. Rapid automated tracing and feature extraction from retinal fundus images using direct exploratory algorithms. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 1999;3:125–138. doi: 10.1109/4233.767088. doi:10.1109/4233.767088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu SJ, Li XT, Nicholas P, Toth CA, Izatt JA, Farsiu S. Automatic segmentation of seven retinal layers in SDOCT images congruent with expert manual segmentation. Opt. Express. 2010;18:19413–19428. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.019413. doi:10.1364/OE.18.019413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBuc D. Identifying Local Structural and Optical Derangement in the Neural Retina of Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2013;04 doi:10.4172/2155-9570.1000289. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra EW. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer. Math. 1959;1:269–271. doi:10.1007/BF01386390. [Google Scholar]

- Fraz MM, Remagnino P, Hoppe a., Uyyanonvara B, Rudnicka a. R., Owen CG, Barman S. a. Blood vessel segmentation methodologies in retinal images - A survey. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2012;108:407–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2012.03.009. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XGX, Bharath A, Stanton A, Hughes A, Chapman N, Thom S. A method of vessel tracking for vessel diameter measurement on retinal images. Proc. 2001 Int. Conf. Image Process. 2001 (Cat. No.01CH37205) 2. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2001.958635. [Google Scholar]

- Garhofer G, Bek T, Boehm AG, Gherghel D, Grunwald J, Jeppesen P, Kergoat H, Kotliar K, Lanzl I, Lovasik JV, Nagel E, Vilser W, Orgul S, Schmetterer L. Use of the retinal vessel analyzer in ocular blood flow research. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:717–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01587.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinvald A, Bonhoeffer T, Vanzetta I, Pollack A, Aloni E, Ofri R, Nelson D. High-resolution functional optical imaging: From the neocortex to the eye. Ophthalmol. Clin. North Am. 2004;17:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ohc.2003.12.003. doi:10.1016/j.ohc.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Kagemann L, Cioffi GA. Assessment on human ocular hemodynamics. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:509–33. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(98)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izhaky D, Nelson D. a., Burgansky-Eliash Z, Grinvald A. Functional imaging using the retinal function imager: Direct imaging of blood velocity, achieving fluorescein angiography-like images without any contrast agent, qualitative oximetry, and functional metabolic signals. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2009;53:345–351. doi: 10.1007/s10384-009-0689-0. doi:10.1007/s10384-009-0689-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Bailey ST, Hwang TS, McClintic SM, Gao SS, Pennesi ME, Flaxel CJ, Lauer AK, Wilson DJ, Hornegger J, Fujimoto JG, Huang D. Quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography of vascular abnormalities in the living human eye. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:E2395–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500185112. doi:10.1073/pnas.1500185112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura I, Shinoda K, Tanino T, Ohtake Y, Mashima Y, Oguchi Y. Scanning laser Doppler flowmeter study of retinal blood flow in macular area of healthy volunteers. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1469–1473. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.12.1469. doi:10.1136/bjo.87.12.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kur J, Newman EA, Chan-Ling T. Cellular and physiological mechanisms underlying blood flow regulation in the retina and choroid in health and disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2012;31:377–406. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.04.004. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa G, Amde W, Haileselassie Y, Rosen RB. Cilioretinal arteries in diabetic eyes are associated with increased retinal blood flow velocity and occurrence of diabetic macular edema. Retina. 2011;31:304–11. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181e91108. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181e91108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa G, Rosen RB. A new vascular pattern for idiopathic juxtafoveal telangiectasia revealed by the retinal function imager. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging. 2010;41:413–7. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20100325-04. doi:10.3928/15428877-20100325-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luksch A, Lasta M, Polak K, et al. Twelve-hour reproducibility of retinal and optic nerve blood flow parameters in healthy individuals. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:875–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01388.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeijer M, Staal JJ, Ginneken B.v., Loog M, Abramoff MD. DRIVE: digital retinal images for vessel extraction. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Q, Gillies MC, Wong TY. Management of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:902–916. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.8.902. doi:10.1001/jama.298.8.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka T, Kitaya N, Sugawara R, Yokota H, Mori F, Hikichi T, Fujio N, Yoshida a. Alteration of choroidal circulation in the foveal region in patients with type 2 diabetes. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1060–1063. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.035345. doi:10.1136/bjo.2003.035345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Eye Institute Facts About Diabetic Eye Disease [WWW Document] 2012 URL http://www.nei.nih.gov/health/diabetic/retinopathy.asp.

- Nelson D. a, Krupsky S, Pollack A, Aloni E, Belkin M, Vanzetta I, Rosner M, Grinvald A. Special report: Noninvasive multi-parameter functional optical imaging of the eye. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging. 2005;36:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RFI 3005 System Operation Manual. 2010 Optical Imaging. [Google Scholar]

- 510(k) Summary: Retinal Function Imager 3000. 2008 optical imaging. [Google Scholar]

- Pemp B, Schmetterer L. Ocular blood flow in diabetes and age-related macular degeneration. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2008;43:295–301. doi: 10.3129/i08-049. doi:10.3129/i08-049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrig BL, Riva CE, Hayreh SS. Laser Doppler flowmetry and optic nerve head blood flow. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1999;127:413–425. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polska E, Ehrlich P, Luksch A, Fuchsjäger-Mayrl G, Schmetterer L. Effects of adenosine on intraocular pressure, optic nerve head blood flow, and choroidal blood flow in healthy humans. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:3110–3114. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1133. doi:10.1167/iovs.02-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva CE, Falsini B, Logean E. Flicker-evoked responses of human optic nerve head blood flow: luminance versus chromatic modulation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001;42:756–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva CE, Feke GT, Eberli B, Benary V. Bidirectional LDV system for absolute measurement of blood speed in retinal vessels. Appl. Opt. 1979;18:2301–2306. doi: 10.1364/AO.18.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quek FKH, Kirbas C. Vessel extraction in medical images by wave- propagation and traceback. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2001;20:117–131. doi: 10.1109/42.913178. doi:10.1109/42.913178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalmans I, Vandewalle E, Anderson DR, Costa VP, Frenkel RE, Garhofer G, Grunwald J, Gugleta K, Harris A, Hudson C, Januleviciene I, Kagemann L, Kergoat H, Lovasik JV, Lanzl I, Martinez A, Nguyen QD, Plange N, Reitsamer HA, Sehi M, Siesky B, Zeitz O, Orgul S, Schmetterer L. Use of colour Doppler imaging in ocular blood flow research. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:e609–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02178.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CV. The i2k Align and i2k Align Retina Toolkits: Correspondence and Transformations. Clifton Park, NY.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Araie M, Riva CE, Schmetterer L, Orgul S. Use of laser speckle flowgraphy in ocular blood flow research. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01586.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutera S. The History of Poiseuille's Law. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1993 doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.25.1.1. [Google Scholar]

- Walker WF, Trahey GE. Fundamental limit on delay estimation using partially correlated speckle signals. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1995;42:301–308. doi:10.1109/58.365243. [Google Scholar]

- Witkin AJ, Alshareef RA, Rezeq SS, Sampat KM, Chhablani J, Bartsch D-UG, Freeman WR, Haller JA, Garg SJ. Comparative analysis of the retinal microvasculature visualized with fluorescein angiography and the retinal function imager. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2012;154:901–907. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.052. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]