Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about the prevalence of combined anxiety and depressive symptoms (CADS) in breast cancer patients. Purpose was to evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics and quality of life (QOL) prior to breast cancer surgery among women classified into one of four distinct anxiety and/or depressive symptom groups.

Methods

A total of 335 patients completed measures of anxiety and depressive symptoms and QOL prior to and for 6 months following breast cancer surgery. Growth Mixture Modelling (GMM) was used to identify subgroups of women with distinct trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms. These results were used to create four distinct anxiety and/or depressive symptom groups. Differences in demographic, clinical, and symptom characteristics, among these groups were evaluated using analyses of variance and Chi square analyses.

Results

A total of 44.5% of patients were categorized with CADS. Women with CADS were younger, non-white, had lower performance status, received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy, had greater difficulty dealing with their disease and treatment, and reported less support from others to meet their needs. These women had lower physical, psychological, social well-being, and total QOL scores. Higher levels of anxiety with or without subsyndromal depressive symptoms were associated with increased fears of recurrence, hopelessness, uncertainty, loss of control, and a decrease in life satisfaction.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that CADS occurs in a high percentage of women following breast cancer surgery and results in a poorer QOL. Assessments of anxiety and depressive symptoms are warranted prior to surgery for breast cancer.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, breast cancer, surgery, subsyndromal depression, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Population-based studies suggest that depression and anxiety disorders affect about 6.7% and 18% of Americans, respectively (Kessler et al., 2003; Kessler et al., 2010) . What is less clear, particularly in primary care settings, is the percentage of individuals who have mixed anxiety and depression disorders (Means-Christensen et al., 2006; Roy-Byrne et al., 1994; Zbozinek et al., 2012). Part of this uncertainty comes from ambiguity in the definitions of anxiety and depression, each of which refers to several different types and levels of disorders that vary in terms of the severity of the symptoms experienced (Katon and Roy-Byrne, 1991).

Both depression and anxiety are more common in oncology patients than in the general population. These two symptoms are often assessed together and referred to as psychological distress (Brintzenhofe-Szoc et al., 2009). Previous psychological treatment, lack of an intimate confiding relationship, younger age, and severely stressful non-cancer life experiences were associated with the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer (Burgess et al., 2005). Additionally, in oncology patients, these two treatable conditions are associated with non-adherence to treatment recommendations; increased time in the hospital; and impaired physical, social, and family functioning (Mitchell et al., 2011). Finally, findings suggest that anxiety and depression are associated with a poorer prognosis and increased mortality (Jones, 2001).

Several systematic reviews have noted wide variations in the prevalence rates for anxiety and depression in oncology patients (Mitchell et al., 2011; Singer et al., 2010; van't Spijker et al., 1997). Although many studies mention the co-occurrence of anxiety and depression in these patients, only three studies were identified that provided information on the exact prevalence rates for combined anxiety/depressive symptoms (CADS) in patients with breast cancer (Brintzenhofe-Szoc et al., 2009; So et al., 2010; Van Esch et al., 2012). In a large epidemiological study that assessed patients at the time of diagnosis or prior to the initiation of cancer treatment (n=8,175), using the Brief Symptom Inventory (Brintzenhofe-Szoc et al., 2009), 10.8% of the patients with breast cancer had CADS, 14.9% had only anxiety symptoms, 2.8% had only depressive symptoms, and 71.5% had neither symptom.

In the second study that assessed Chinese patients (n=218) midway through chemotherapy (CTX) or radiation therapy (RT) for breast cancer, using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (So et al., 2010), 15.6% of the sample had CADS. In the third longitudinal study that assessed CADS in patients prior to the diagnosis of breast cancer (n=482) and again at 12 and 24 months after the diagnosis, using the short-form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale (Van Esch et al., 2012), the occurrence rates for CADS were 28%, 14%, and 10%, respectively. The occurrence of CADS at the time of cancer diagnosis was associated with higher levels of fatigue and poorer quality of life (QOL) at 12 and 24 months after cancer diagnosis.

While findings from these studies suggest that CADS occurs in 10% to 28% of patients with breast cancer depending on the time of the assessment (Brintzenhofe-Szoc et al., 2009; So et al., 2010; Van Esch et al., 2012), the demographic and clinical characteristics associated with CADS as well as its impact on QOL outcomes have not been evaluated rigorously. In addition, single assessments of anxiety and depressive symptoms were used to diagnosis CADS. However, significant heterogeneity exists in the trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms over the course of patients’ cancer treatment (Kyranou et al., 2014a; Kyranou et al., 2014b).

Our research team evaluated anxiety (Miaskowski et al., 2015) and depressive (Dunn et al., 2011) symptoms in women (n=398) prior to and for six months following breast cancer surgery. Our detailed characterization of anxiety and depressive symptoms in these patients provided an opportunity for us to evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as QOL outcomes prior to breast cancer surgery among women who were classified into one of four distinct groups (i.e., Lower Anxiety and Resilient; Lower Anxiety and Subsyndromal Depressive symptoms; Higher Anxiety and Resilient; Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal Depressive symptoms). Knowledge of preoperative characteristics associated with the co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms can be used by nurses to identify higher risk patients and initiate pre-emptive or postoperative interventions to reduce psychological distress in these patients.

METHODS

Patients and Settings

This descriptive, study is part of a larger study that evaluated for neuropathic pain, lymphedema, and other symptoms in a sample of women who underwent breast cancer surgery. A detailed description of the methods are published elsewhere (Dunn et al., 2011; McCann et al., 2012; Miaskowski et al., 2014; Van Onselen et al., 2013). In brief, patients were recruited from Breast Care Centers located in a Comprehensive Cancer Center, two public hospitals, and four community practices.

Patients were eligible to participate if they were >18 years of age; would undergo breast cancer surgery on one breast, were able to read, write, and understand English; agreed to participate; and gave written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were having breast cancer surgery on both breasts or had distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis.

A total of 516 patients were approached and 410 were enrolled in the study (response rate 79.5%). For those who declined participation, the major reasons for refusal were: too busy, overwhelmed with the cancer diagnosis, or insufficient time available to do the assessment prior to surgery. A sample of 335 patients was available to be used in the creation of the anxiety and depressive symptom groups.

Study Procedures

The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco and the Institutional Review Boards at each of the study sites approved the study. During the patients’ preoperative visit, a staff member explained the study to the patient and introduced the patient to the research nurse who met with the women, determined eligibility, and obtained written informed consent prior to surgery. After providing consent, patients completed the enrollment questionnaires. Patients were contacted two weeks after surgery to schedule the first post-surgical appointment. The research nurse met with the patients either in their home or in the Clinical Research Center at one, two, three, four, five, and six months after surgery.

Instruments

A demographic questionnaire obtained information on age, education, ethnicity, marital status, employment, and financial status. Medical records were reviewed to obtain information on disease and treatment characteristics.

Patient's functional status was assessed using the KPS scale, which ranges from 30 (I feel severely disabled and need to be hospitalized) to 100 (I feel normal, I have no complaints or symptoms). The KPS has well established validity and reliability (Karnofsky, 1977).

The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaires (SCQ) is a short and easily understood instrument that was developed to measure comorbidity in clinical and health service research settings (Sangha et al., 2003). The questionnaire consists of 13 common medical conditions. Patients were asked to indicate if they had the condition; if they received treatment for it; and did it limit their activities (indication of functional limitations). For each condition, a patient can receive a maximum of 3 points. The SCQ has well-established validity and reliability and was used in studies of patients with a variety of chronic conditions (Brunner et al., 2008; Cieza et al., 2006; MacLean et al., 2006).

The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventories (STAI-T, STAI-S) consist of 20 items each that are rated from 1 to 4. Scores for each scale are summed and can range from 20 to 80. A higher score indicates greater anxiety. The STAI-T measures an individual's predisposition to anxiety determined by his/her personality and estimates how a person generally feels. The STAI-S measures an individual's transitory emotional response to a stressful situation. It evaluates the emotional responses of worry, nervousness, tension, and feelings of apprehension related to how a person feels “right now” in a stressful situation. Cutoff scores of >31.8 and >32.2 indicate high levels of trait and state anxiety, respectively (Kennedy et al., 2001; Spielberger et al., 1983). In this study, Cronbach's alphas for the STAI-T and STAI-S were .88 and .95, respectively.

The CES-D consists of 20 items selected to represent the major symptoms in the clinical syndrome of depression. Scores can range from 0 to 60, with scores of >16 indicating the need for individuals to seek clinical evaluation for major depression. The CES-D has well-established concurrent and construct validity (Radloff, 1977; Sheehan et al., 1995). In this study, Cronbach's alpha for the CES-D was 0.90.

The Quality of Life Scale-Patient Version (QOL-PV) is a 41-item instrument that measures four dimensions of QOL in cancer patients (i.e., physical well-being, psychological well-being, spiritual well-being, social well-being), as well as a total QOL score. Each item was rated on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale (NRS) with higher scores indicating a better QOL. The QOL-PV has well established validity and reliability (Ferrell et al., 1989; Padilla and Grant, 1985; Padilla et al., 1983). In this study, Cronbach's alpha for the QOL-PV total score was .86. For the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being subscales, the coefficients were 0.70, 0.79, 0.75, and 0.61, respectively.

Selected items from the QOL-PV were used to assess a number of psychosocial adjustment characteristics. Singular items asked patients to provide ratings of life satisfaction, sense of purpose/mission in life, and hopefulness. In addition, patients were asked to rate the amount of isolation caused by their illness and the degree of uncertainty they felt about the future. Fear was assessed with three questions: fear of future diagnostic tests, fear of a second cancer, and fear of metastasis. One question asked patients to rate the level of control they felt over their lives and another asked patients to rate their difficulty coping as a result of the cancer and its treatment. The final item asked patients to rate whether the amount of support they received from others was sufficient to meet their needs. Each item was rated using a 0 to 10 NRS with higher scores indicating a more positive appraisal of a particular characteristic. The specific items were chosen based on the review of the literature of psychosocial adjustment and depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer (Dean, 1987; Dunn et al., 2014; Epping-Jordan et al., 1999; Gallagher et al., 2002; Henselmans et al., 2010; Hinnen et al., 2008; Maunsell et al., 1989; Millar et al., 2005; Nosarti et al., 2002).

Data Analysis

GMM Analyses of the Anxiety and Depression Classes

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 20 (SPSS, 2012) and Mplus Version 6.11 (Muthen and Muthen, 1998-2010). The specific details regarding the identification of the anxiety (Miaskowski et al., 2015) and depression (Dunn et al., 2011) latent classes using growth mixture modeling (GMM) are published elsewhere. In brief, for each symptom, a single growth curve that represented the “average” change trajectory was estimated for the total sample. Then the number of latent growth classes that best fit the data was identified using published guidelines (Jung and Wickrama, 2008; Nylund et al., 2007; Tofighi and Enders, 2008). Separate GMM analyses were done for anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Using GMM to evaluate patients’ ratings of state anxiety using the STAI, two distinct latent classes were identified. The Lower Anxiety class (36.9%) had state anxiety scores of 31.9 at enrollment that gradually decreased over the 6 months of the study. The Higher Anxiety class (63.1%) had state anxiety scores of 49.5 at enrollment that gradually decreased over the 6 months of the study. When CES-D scores were analyzed using GMM, four distinct latent classes were identified (i.e., Resilient (38.9%), Subsyndromal (45.2%), Delayed (11.3%), and Peak (4.5%)). The Delayed and Peaked Depressive symptom classes were not included in the subsequent analyses because the number of patients in each class was too small for meaningful comparisons.

Creation of the Four Groups of Patients

For the purposes of this study, the results of the GMM analyses for anxiety (i.e., Lower and Higher Anxiety latent classes) and depressive symptoms (i.e., Resilient and Subsyndromal latent classes) were cross-tabulated to create the four groups of patients (i.e., Lower Anxiety and Resilient; Lower Anxiety and Subsyndromal Depressive symptoms; Higher Anxiety and Resilient; Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal Depressive symptoms).

Evaluation of differences among the anxiety/depression groups

Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were generated on the sample characteristics using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 (SPSS, 2012). Differences in demographic, clinical, and psychological adjustment characteristics and QOL outcomes at enrollment [unless specified in the Tables], among the four groups, were evaluated using analyses of variance, Kruskal-Wallis, and Chi Square analyses. Adjustments were not made for missing data. Therefore, the cohort for each analysis was dependent on the largest set of available data across groups. A p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Post hoc contrasts were done using the Bonferroni correction to control the overall family alpha level of the six possible pairwise contrasts for the four anxiety/depression groups at .05. For any one of the six possible pairwise contrasts, a p-value of <.008 (.05/6) was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Creation of the Four Anxiety/Depression Groups

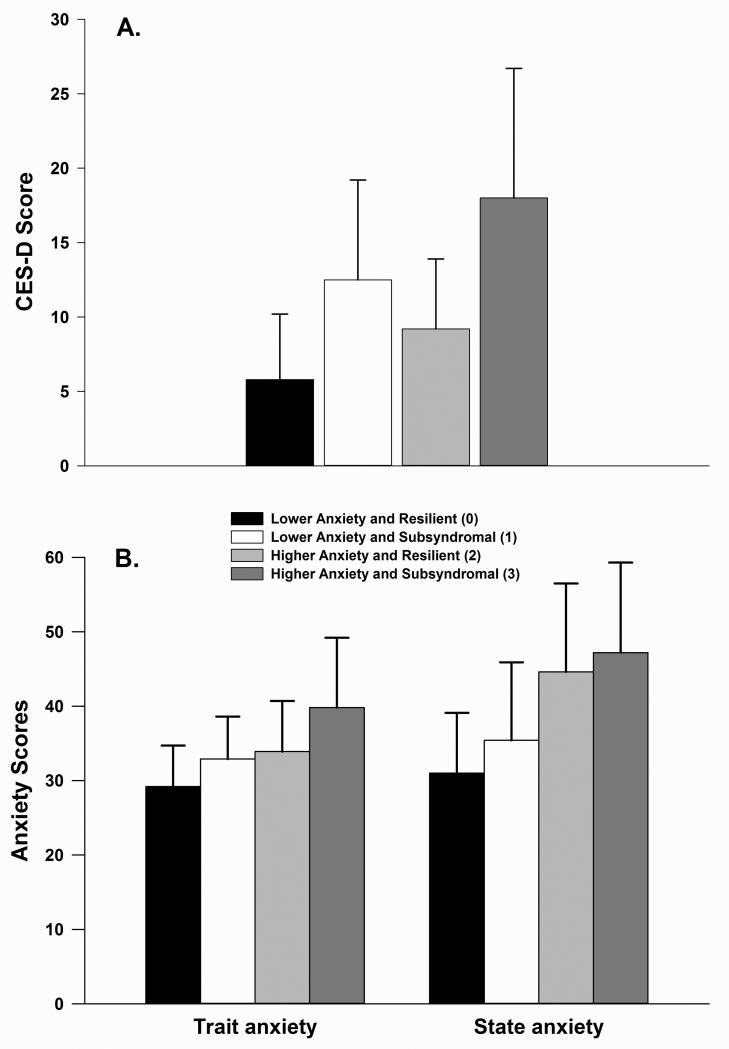

Four groups of patients (n=355) were created by combining the results from the GMM analyses for anxiety (Miaskowski et al., 2015) and depressive (Dunn et al., 2011) symptoms. As shown in Table 1, the largest percentage of patients was classified in the Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal group (n=149, 44.5%; group 3). The second largest group was called the Lower Anxiety and Resilient group (n=109, 32.5%; group 0). The third largest group was called the Higher Anxiety and Resilient group (n=46, 11.6%; group 2). The smallest percentage of patients were in the Lower Anxiety and Subsyndromal group (n=31, 9.3%; group 1). The CES-D and Trait Anxiety and State Anxiety scores prior to surgery, for each of the groups are shown in Figures 1A and 1B, respectively.

Table 1.

Differences in Demographic Characteristics Among the Depression and Anxiety Groups at Enrollment (N=335)

| Characteristic | Lower Anxiety and Resilient (0) % (N) 32.5 (109) | Lower Anxiety and Subsyndromal (1) % (N) 9.3 (31) | Higher Anxiety and Resilient (2) % (N) 11.6 (46) | Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal (3) % (N) 44.5 (149) | Statistics and post hoc contrasts* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 58.3 (11.2) | 53.6 (12.6) | 54.9 (10.1) | 52.8 (11.8) | F=4.97, p=.002 3<0 |

| Education (years) | 15.8 (2.3) | 16.2 (3.2) | 15.9 (2.8) | 15.8 (2.7) | F=.25, p=.864 |

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | ||

| Ethnicity | X2=15.92 | ||||

| White | 76.9 (83) | 80.6 (25) | 52.2 (24) | 58.8 (87) | p=.001 |

| Non-white | 23.1 (25) | 19.4 (6) | 47.8 (22) | 41.2 (61) | 0< 2 and 3 |

| Lives alone | |||||

| Yes | 18.3 (20) | 32.3 (10) | 31.1 (14) | 21.1 (31) | X2=4.84 |

| No | 81.7 (89) | 67.7 (21) | 68.9 (31) | 78.9 (116) | p=.184 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/partnered | 31.2 (34) | 51.6 (16) | 44.4 (20) | 45.9 (68) | X2=7.44 |

| Single, separated, widowed, divorced | 68.8 (75) | 48.4 (15) | 55.6 (25) | 54.1 (80) | p=.059 |

| Currently working for pay | |||||

| Yes | 54.1 (59) | 38.7 (12) | 41.3 (19) | 48.3 (71) | X2=3.53 |

| No | 45.9 (50) | 61.3 (19) | 58.7 (27) | 51.7 (76) | p=.317 |

| Total annual household income | |||||

| <$30,000 | 13.6 (12) | 17.9 (5) | 20.0 (8) | 26.8 (33) | KW=7.21 |

| $30,000 to $99,999 | 37.5 (33) | 46.4 (13) | 52.5 (21) | 37.4 (46) | p=.066 |

| ≥$100,000 | 48.9 (43) | 35.7 (10) | 27.5 (11) | 35.8 (44) | |

Abbreviations: KW = Kruskal-Wallis, SD = standard deviation

For the interpretation of the post hoc contrasts: Group 0 = lower anxiety and resilient group; Group 1 = lower anxiety and subsyndromal group; Group 2 = higher anxiety and resilient group; and Group 3 = higher anxiety and subsyndromal group.

Figure 1.

Differences among the four anxiety and depressive symptom groups in Center for Epidemiological Studies Scale (CES-D) scores (A) and Trait and State Anxiety scores (B) at enrollment. All values are plotted as means ± standard deviations. For CES-D scores, post hoc contrasts revealed that group 0 < 1, 2, and 3 (all p≤.001) and that groups 1 and 2 < 3 (both p≤.031). For State Anxiety scores, post hoc contrasts revealed that group 0 < 2 and 3 (both p<.0001) and group 1 < 2 and 3 (both p≤.003). For Trait Anxiety, post hoc contrasts revealed that group 0 < 2 and 3 (both p≤.004) and that group 1 < 2 and 3 (both p<.0001).

Differences in demographic characteristics among the anxiety and depression groups

As shown in Table 1, except for age and ethnicity, no significant differences were found among the four groups in any demographic characteristics at enrollment. Patients in the Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal group were younger than those in the Lower Anxiety and Resilient group. Compared to the Lower Anxiety and Resilient group, a higher percentage of Non-white women were in the Higher Anxiety and Resilient and Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal groups.

Differences in clinical characteristics among the anxiety and depression groups

As shown in Table 2, except for KPS scores, the occurrence of high blood pressure, the receipt of neoadjuvant or adjuvant CTX, and the use of complementary therapies, no significant differences in any of the other clinical characteristics were found among the four groups. In terms of enrollment KPS scores, patients in both Subsyndromal groups had lower KPS scores than those in the Lower Anxiety and Resilient group.

Table 2.

Differences in Clinical Characteristics Among the Depression and Anxiety Groups at Enrollment and Following Breast Cancer Surgery

| Characteristic | Lower Anxiety and Resilient (0) % (N) 32.5 (109) | Lower Anxiety and Subsyndromal (1) % (N) 9.3 (31) | Higher Anxiety and Resilient (2) % (N) 11.6 (46) | Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal (3) % (N) 44.5 (149) | Statistics and post hoc contrasts* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.4 (6.3) | 27.1 (5.4) | 27.7 (6.5) | 27.1 (6.3) | F=.53, p=.665 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 96.1 (8.6) | 90.6 (11.8) | 93.9 (8.8) | 91.3 (11.0) | F=5.54, p=.001 0>1 and 3 |

| Self-Administered Comorbidity Scale score | 3.9 (2.4) | 3.9 (2.4) | 4.3 (2.6) | 4.7 (3.2) | F=2.17, p=.092 |

| Number of breast biopsies | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.6 (0.9) | F=1.19, p=.313 |

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | ||

| Occurrence of comorbid conditions (% and number of women who reported each comorbid condition from the Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire) | |||||

| Heart disease | 5.5 (6) | 0.0 (0) | 2.2 (1) | 2.7 (4) | X2=3.10, p=.378 |

| High blood pressure | 36.7 (40) | 16.1 (5) | 43.5 (20) | 27.5 (41) | X2=8.89, p=.031 |

| NS pairwise contrasts | |||||

| Lung disease | 0.9 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 4.3 (2) | 4.7 (7) | X2=4.37, p=.224 |

| Diabetes | 3.7 (4) | 12.9 (4) | 15.2 (7) | 8.1 (12) | X2=7.00, p=.072 |

| Ulcer | 2.8 (3) | 3.2 (1) | 6.5 (3) | 4.0 (6) | X2=1.28, p=.735 |

| Kidney disease | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 2.0 (3) | X2=3.78, p=.286 |

| Liver disease | 3.7 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 2.2 (1) | 2.0 (3) | X2=1.63, p=.654 |

| Anemia | 8.3 (9) | 3.2 (1) | 4.3 (2) | 10.1 (15) | X2=2.65, p=.449 |

| Depression | 17.4 (19) | 12.9 (4) | 15.2 (7) | 26.2 (39) | X2=5.44, p=.142 |

| Osteoarthritis | 13.8 (15) | 22.6 (7) | 17.4 (8) | 15.4 (23) | X2=1.51, p=.679 |

| Back pain | 23.9 (26) | 38.7 (12) | 21.7 (10) | 30.2 (45) | X2=3.96, p=.266 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2.8 (3) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 4.7 (7) | X2=3.90, p=.273 |

| Gone through menopause | |||||

| Yes | 68.5 (74) | 58.1 (18) | 66.7 (30) | 60.6 (86) | X2=2.29 |

| No | 31.5 (34) | 41.9 (13) | 33.3 (15) | 39.4 (56) | p=.515 |

| Received neoadjuvant chemotherapy | X2=8.58 | ||||

| Yes | 12.0 (13) | 19.4 (6) | 28.3 (13) | 25.5 (38) | p=.035 |

| No | 88.0 (95) | 80.6 (25) | 71.7 (33) | 74.5 (111) | 0<3 |

| On hormonal replacement therapy prior to surgery | |||||

| Yes | 18.5 (20) | 16.1 (5) | 8.7 (4) | 14.9 (22) | X2=2.45 |

| No | 81.5 (88) | 83.9 (26) | 91.3 (42) | 85.1 (126) | p=.485 |

| Stage of disease | |||||

| Stage 0 | 19.3 (21) | 22.6 (7) | 10.9 (5) | 18.1 (27) | |

| Stage 1 | 45.9 (50) | 38.7 (12) | 39.1 (18) | 28.2 (42) | X2=14.41 |

| Stage IIA and IIB | 30.3 (33) | 32.3 (10) | 37.0 (17) | 42.3 (63) | p=.109 |

| Stage IIIA, IIIB, IIIC, and IV | 4.6 (5) | 6.5 (2) | 13.0 (6) | 11.4 (17) | |

| Type of surgery | |||||

| Breast conserving | 80.7 (88) | 83.9 (26) | 84.8 (39) | 77.9 (116) | X2=1.41 |

| Mastectomy | 19.3 (21) | 16.1 (5) | 15.2 (7) | 22.1 (33) | p=.703 |

| Sentinel lymph node biopsy | |||||

| Yes | 87.2 (95) | 80.6 (25) | 82.6 (38) | 79.9 (119) | X2=2.44 |

| No | 12.8 (14) | 19.4 (6) | 17.4 (8) | 20.1 (30) | p=.486 |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | |||||

| Yes | 30.6 (33) | 41.9 (13) | 41.3 (19) | 46.3 (69) | X2=6.56 |

| No | 69.4 (75) | 58.1 (18) | 58.7 (27) | 53.7 (80) | p=.087 |

| Reconstruction at the time of surgery | |||||

| Yes | 20.4 (22) | 25.8 (8) | 13.0 (6) | 22.1 (33) | X2=2.34 |

| No | 79.6 (86) | 74.2 (23) | 87.0 (40) | 77.9 (116) | p=.506 |

| Received radiation therapy during the 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 59.6 (65) | 51.6 (16) | 60.9 (28) | 53.0 (79) | X2=1.81 |

| No | 40.4 (44) | 48.4 (15) | 39.1 (18) | 47.0 (70) | p=.614 |

| Received adjuvant chemotherapy during the 6 months | X2=9.94 | ||||

| Yes | 22.9 (25) | 35.5 (11) | 37.0 (17) | 41.6 (62) | p=.019 |

| No | 77.1 (84) | 64.5 (20) | 63.0 (29) | 58.4 (87) | 0<3 |

| Received hormonal therapy during the 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 46.8 (51) | 38.7 (12) | 45.7 (21) | 40.3 (60) | X2=1.46 |

| No | 53.2 (58) | 61.3 (19) | 54.3 (25) | 59.7 (89) | p=.692 |

| Received biological therapy during the 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 9.2 (10) | 9.7 (3) | 13.0 (6) | 12.8 (19) | X2=1.02 |

| No | 90.8 (99) | 90.3 (28) | 87.0 (40) | 87.2 (130) | p=.796 |

| Received complementary therapy during the 6 months | X2=9.76 | ||||

| Yes | 21.1 (23) | 38.7 (12) | 17.4 (8) | 34.2 (51) | p=.021 |

| No | 78.9 (86) | 61.3 (19) | 82.6 (38) | 65.8 (98) | NS pairwise contrasts |

| Received physical therapy during the 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 14.7 (16) | 9.7 (3) | 19.6 (9) | 17.4 (26) | X2=1.72 |

| No | 85.3 (93) | 90.3 (28) | 80.4 (37) | 82.6 (123) | p=.633 |

| Had breast reconstruction during the 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 5.5 (6) | 9.7 (3) | 0.0 (0) | 7.4 (11) | X2=4.25 |

| No | 94.5 (103) | 90.3 (28) | 100.0 (146) | 92.6 (138) | p=.236 |

| Had re-excision or mastectomy during the 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 27.5 (30) | 29.0 (9) | 34.8 (16) | 25.5 (38) | X2=1.54 |

| No | 72.5 (79) | 71.0 (22) | 65.2 (30) | 74.5 (111) | p=.674 |

| Evidence of metastatic disease during the 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 2.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | X2=6.30 |

| No | 100.0 (109) | 100.0 (31) | 97.8 (45) | 100.0 (149) | p=.098 |

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation, NS= no significant

For the interpretation of the post hoc contrasts: Group 0 = lower anxiety and resilient group; Group 1 = lower anxiety and subsyndromal group; Group 2 = higher anxiety and resilient group; and Group 3 = higher anxiety and subsyndromal group.

For both receipt of neoadjuvant and adjuvant CTX, compared to the Lower Anxiety and Resilient group, a higher percentage of patients in the Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal group received these treatments. For both high blood pressure and the use of complementary therapy, while the overall Chi square tests were significant, the pairwise contrasts were not significant.

Differences in psychosocial adjustment characteristics among the anxiety and depression groups

For each of the psychosocial adjustment characteristics that were evaluated prior to surgery (Table 3), statistically significant differences were found among the groups. For the uncertainty item and the four fear items (i.e., future diagnostic tests, second cancer, recurrence, metastasis), post hoc contrasts revealed the same pattern of between group differences (i.e., group 2 < 0 and group 3 < 0 and 1). For the satisfaction with life and sense of control items, post hoc contrasts revealed the same pattern of between group differences (i.e., group 2 < 0 and group 3 < 0, 1, and 2). The remaining items’ post hoc contrasts are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Differences in Psychosocial Adjustment Characteristics Among the Depression and Anxiety Groups at Enrollment

| Characteristic | Lower Anxiety and Resilient (0) % (N) 32.5 (109) | Lower Anxiety and Subsyndromal (1) % (N) 9.3 (31) | Higher Anxiety and Resilient (2) % (N) 11.6 (46) | Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal (3) % (N) 44.5 (149) | Statistics and post hoc contrasts* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| How satisfying is your life? (0 = not at all to 10 = completely satisfied) | 8.7 (1.3) | 7.8 (1.6) | 7.7 (1.4) | 6.3 (2.5) | F=30.06, p<.001 2<0, 3<0,1 and 2 |

| Do you have a purpose/mission for your life or a reason for being alive? (0 = none at all to 10 = a great deal) | 9.0 (1.8) | 8.5 (2.0) | 7.8 (3.0) | 8.2 (2.2) | F=3.67, p=.013 2<0 |

| How hopeful do you feel? (0 = not hopeful at all to 10 = extremely hopeful) | 9.1 (1.2) | 8.6 (1.5) | 8.3 (1.7) | 7.7 (2.2) | F=14.55, p<.001 2 and 3 <0 |

| How much isolation is caused by your illness? (0 = a great deal to 10 = none) | 9.0 (1.9) | 8.9 (2.3) | 8.3 (2.9) | 7.2 (2.9) | F=11.81, p<.001 3<0 and 1 |

| How much uncertainty do you feel about your future? (0 = extreme uncertainty to 10 = not at all uncertain) | 7.0 (2.7) | 5.6 (2.9) | 4.5 (3.2) | 3.9 (2.9) | F=24.94, p<.001 2<0, 3<0 and 1 |

| To what extent are you fearful of future diagnostic tests? (0 = extreme fear to 10 = no fear) | 6.4 (3.1) | 5.9 (3.4) | 4.0 (3.2) | 3.9 (3.1) | F=15.88, p<.001 2<0, 3<0 and 1 |

| To what extent are you fearful of a second cancer? (0 = extreme fear to 10 = no fear) | 5.5 (3.2) | 4.9 (3.7) | 3.9 (3.5) | 2.9 (3.0) | F=14.07, p=<.001 2<0, 3<0 and 1 |

| To what extent are you fearful of recurrence? (0 = extreme fear to 10 = no fear) | 5.7 (3.2) | 4.6 (3.5) | 3.7 (3.5) | 2.8 (3.1) | F=15.72, p=<.001 2<0, 3<0 and 1 |

| To what extent are you fearful of metastasis? (0 = extreme fear to 10 = no fear) | 5.6 (3.5) | 4.9 (3.8) | 3.6 (3.7) | 2.9 (3.4) | F=13.19, p<.001 2<0, 3<0 and 1 |

| Do you feel like you are in control of things in your life? (0 = not at all to 10 = completely in control) | 7.8 (1.8) | 7.2 (2.0) | 6.4 (2.5) | 5.1 (2.6) | F=27.34, p<.001 2<0, 3<0,1 and 2 |

| How difficult is it for you to cope as a result of your disease and treatment? (0 = extremely difficult to 10 = not at all difficult) | 8.4 (1.8) | 7.3 (2.6) | 7.3 (2.6) | 5.6 (2.5) | F=29.87, p<.001 3 < 0,1 and 2 |

| Is the amount of support you receive from others sufficient to meet your needs? (0 = not at all sufficient to 10 = completely sufficient) | 9.3 (1.3) | 8.9 (2.1) | 8.8 (2.0) | 8.1 (2.2) | F=9.26, p<.001 3<0 |

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation

For the interpretation of the post hoc contrasts: Group 0 = lower anxiety and resilient group; Group 1 = lower anxiety and subsyndromal group; Group 2 = higher anxiety and resilient group; and Group 3 = higher anxiety and subsyndromal group.

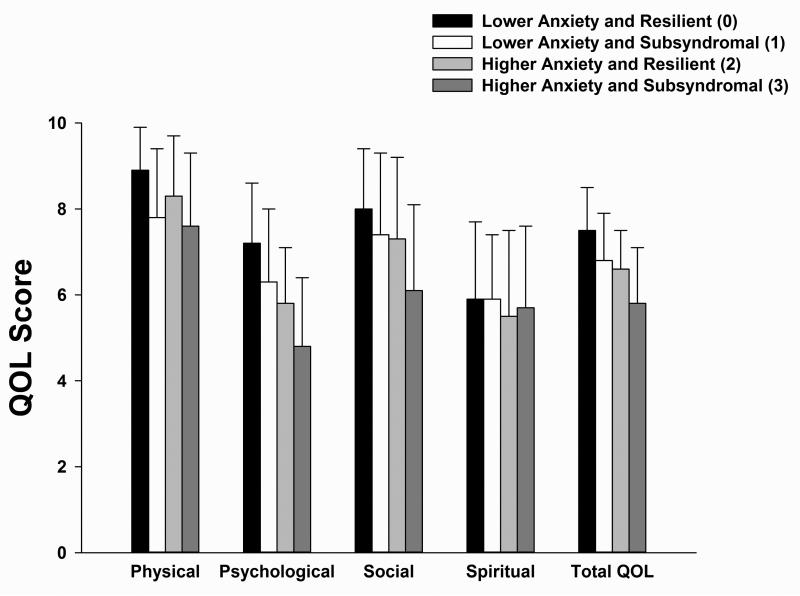

Differences in QOL subscale and total scores among the anxiety and depression groups

For three of the four QOL subscales that were evaluated prior to surgery (Figure 2), statistically significant differences were found among the four groups. Overall, patients in the Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal group reported lower physical, psychological, and social well-being scores, as well as total QOL scores, compared to patients in the other three groups. No significance differences were found among the four groups in spiritual well-being scores. The remaining post hoc contrasts are presented in the legend for Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Differences among the four anxiety and depressive symptom groups in physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and total quality of life (QOL) scores at enrollment. All values are plotted as means ± standard deviations. For the physical well-being subscale, post hoc contrasts revealed that group 0 > 1 and 3 (both p ≤.003) and that group 2 > 3 (p = .018). For the psychological well-being subscale, post hoc contrasts revealed that group 0 > 1, 2, and 3 (all p≤.028) and that groups 1 and 2 > 3 (both p≤.002). For the social well-being subscale, groups 0, 1, and 2 > 3 (all p≤.002). For the total QOL score, groups 0, 1, and 2 > 3 (all p<.0001).

Discussion

This study is the first to combine data from the GMM analyses of anxiety (Miaskowski et al., 2015) and depressive (Dunn et al., 2011) symptoms in patients with breast cancer to characterize women with and without CADS. In our previous reports on these GMM analyses (Dunn et al., 2011; Miaskowski et al., 2015), as well as in analyses done for pain (Miaskowski et al., 2014), fatigue (Dhruva et al., 2013), sleep disturbance (Alfaro et al., 2014), and attentional function (Merriman et al., 2014), in these same patients, we suggest that the use of this analytic approach with longitudinal data identifies patients with persistent symptom phenotypes. Therefore, this novel approach to the identification of four subgroups of women with distinct profiles for anxiety and depressive symptoms provides new insights into risk factors for CADS in women with breast cancer.

In the current study, nearly half of the patients (44.5%) were classified in the Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal group which represented the largest subgroup in this sample. Prior to surgery, this groups anxiety (47.2 ± 12.1) and depressive (18.0 ± 8.7) symptom scores were above the clinically meaningful cut-off scores. This percentage is higher than the three previous reports of CADS in patients with breast cancer in which prevalence estimates ranged from 10.8% (Brintzenhofe-Szoc et al., 2009) to 28% (Van Esch et al., 2012). These differences may be related to differences in the measures used to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms, the timing of the assessments, the definitions of CADS, and the characteristics of the patients who were evaluated.

Only two demographic characteristics (i.e., age, ethnicity) distinguished among the anxiety and depression groups. Consistent with previous studies (Burgess et al., 2005; Hartl et al., 2010; Hong and Tian, 2014; Jehn et al., 2012; Linden et al., 2012; Parker et al., 2007; Thomas et al., 2010), patients with Higher Anxiety and Subsydromal Depression were younger than women with neither symptom. As noted in two previous reviews (Compas et al., 1999; Mosher and Danoff-Burg, 2005), a number of factors may explain these age-related differences. For example, younger women may have more concerns about disfigurement and feelings of loss of womanhood (Thomas et al., 2010). In addition, younger women may have more concerns about their sexuality, their ability to become pregnant, and their ability to care for their children (Sheppard et al., 2014) or differences in social support and coping strategies (Mosher and Danoff-Burg, 2005).

In terms of ethnicity, our findings are consistent with those of Sheppard and colleagues (2014) who found that about one third of their sample of African American women with breast cancer met cut-off criteria for either depression or anxiety. Of note, younger age, distrust of the medical system, and barriers to care were associated with higher levels of both anxiety and depression in this sample. In addition, Yoo and colleagues (2014) noted that in women of color, increased anxiety and depressive symptoms were associated with more advanced breast cancer at the time of diagnosis, as well as increased mortality. However, additional research is warranted because some studies failed to identify racial/ethnic differences in the occurrence of CADS (Culver et al., 2002; Giedzinska et al., 2004; Janz et al., 2011).

In terms of clinical characteristics, only functional status and receipt of neoadjuvant or adjuvant CTX were associated with anxiety and depression group membership. In terms of functional status, women in both Subsyndromal depressive symptom groups had lower preoperative KPS scores than women in the Resilient groups. Of note, the differences in KPS scores between the two Subsyndromal groups versus the Lower Anxiety and Resilient group represent not only statistically significant, but clinically meaningful differences in functional status (i.e., for both comparisons the effect size was d=0.5) (Osoba et al., 1998; Sloan, 2005). Our finding is consistent with work by Lansky et al (1985) who found that performance status and a history of depression were the strongest predictors of the severity of depressive symptoms in women with cancer. More recently, Hong and Tian (2014) reported that performance status, measured using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale, and younger age were risk factors for both depression and anxiety.

In our study, receipt of neoadjuvant or adjuvant CTX were associated with CADS. Findings regarding the associations between receipt of CTX prior to or following breast cancer surgery and depression and anxiety are inconclusive. While some studies found associations between these treatments and psychological symptoms (Cheung et al., 2011; So et al., 2010; Torres et al., 2013), other studies failed to demonstrate these associations (Kissane et al., 2004; Lam et al., 2007).

Several interesting patterns are worth noting from our evaluation of the differences among the anxiety/depression groups in the scores for the various psychosocial adjustment characteristics that were assessed preoperatively. For all of the characteristics listed in Table 4, except purpose and mission in life, patients who were classified in the Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal Depressive symptoms group reported significantly lower scores than patients in the Lower Anxiety and Resilient group. In addition, for the majority of the psychosocial adjustment characteristics, patients classified in the Higher Anxiety and Resilient group had lower scores than patients in the Lower Anxiety and Resilient group. These findings suggest that higher levels of anxiety with or without Subsyndromal Depressive symptoms are associated with fears of recurrence, hopelessness, uncertainty, loss of control, and a decrease in life satisfaction.

An evaluation of the four fear of recurrence items (see Table 4) suggests that regardless of anxiety or depression group membership, all of the women had concerns regarding recurrence that were present prior to surgery. This finding is consistent with two recent reviews that noted that fear of recurrence is a significant problem for oncology patients (Crist and Grunfeld, 2013; Simard et al., 2013). In addition as noted in these reviews, anxiety and depressive symptoms are well-established correlates of fear of recurrence. In the current study, women in the two lower anxiety groups reported moderate severity scores for the four fear of recurrence items. However, patients in both higher anxiety groups reported severity scores in the severe range for these same four items. As our team hypothesized in a recent report on the predictors of fear of recurrence in the same sample (Dunn et al., 2014), a woman's sense of her ability to cope (i.e. coping self-efficacy) may play a role in patients’ level of adjustment to cancer in the months following surgery. In the social cognitive theory of coping self-efficacy (Benight and Bandura, 2004), both adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies are posited to influence coping self-efficacy.

Therefore, it is interesting to note that patients in the Higher Anxiety and Subsyndromal Depressive symptoms group reported the worst scores for the items related to loss of control, difficulty coping, and social support. These associations are consistent with previous reports that found that decreases in sense of control (Barez et al., 2007; Gallagher et al., 2002; Henselmans et al., 2010); alterations in coping mechanisms (Epping-Jordan et al., 1999; Stanton et al., 2005); and decrements in social support (Gallagher et al., 2002) were associated with CADS in women following breast cancer surgery. Additional research is warranted to determine which types of pharmacologic (e.g., anti-anxiety or antidepressant medications) and nonpharmacologic (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness) interventions would be most effective to decrease anxiety and depressive symptoms in these patients.

As shown in Figure 2, compared to patients in the Lower Anxiety and Resilient group, patients with CADS reported significantly lower physical, psychological, and social well-being, as well as, total QOL scores. This observation is consistent with a number of studies in patients with breast cancer that found that increased severity of each of these psychological symptoms is associated with significant decrements in various dimensions of QOL (Alacacioglu et al., 2010; Hutter et al., 2013; Karakoyun-Celik et al., 2010; So et al., 2010).

Several limitations need to be acknowledged. Self-report measures were used to evaluate for anxiety and depressive symptoms. Future studies need to use a Structured Clinical Interview to confirm the co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in these patients. In addition, previous psychiatric conditions, as well as the use of medications for anxiety and depressive symptoms, were not evaluated at enrollment. Lastly, since the majority of the patients were well-educated, Caucasian women, the findings from this study may not generalize to more ethnically diverse samples of women with breast cancer.

Despite these limitations, findings from this study suggest that CADS occurs in a relatively high percentage of women with breast cancer. Prior to surgery, patients with CADS reported increased fear of recurrence; decreased ability to cope as a result of their disease and treatment; a greater sense of isolation; and less life satisfaction. In addition, their QOL was relatively poor. Clinicians need to assess breast cancer patients for the co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and refer these patients for mental health services. In addition, nurses can use the information on preoperative characteristics associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms to identify higher risk patients and initiate pre-emptive or postoperative interventions to reduce psychological distress in these women. Nurses can evaluate some of the specific concerns listed in Table 3 (e.g., fear of recurrence) and educate patients about unrealistic fears and appropriate coping strategies. Successful treatment of psychological symptoms may lead to improvements in patients’ QOL, as well as reductions in hospitalizations and associated health care costs.

Highlights.

The exact prevalence of combined anxiety and depressive symptoms (CADS) in breast cancer patients is not known.

Almost 50% of the patients with breast cancer had CADS.

Women with CADS were younger age, more likely to be a member of an ethnic minority group; had a lower functional status score, and had greater difficulty dealing with her disease and treatment.

In these women, higher levels of anxiety with or without subsyndromal depressive symptoms were associated with increased fears of recurrence, hopelessness, uncertainty, loss of control, and a decrease in life satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI, CA107091 and CA118658). Dr. Miaskowski is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor and is funded by a K05 award from the NCI (CA168960). This project is supported by NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI grant number UL1 RR024131. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest- The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Alacacioglu A, Binicier O, Gungor O, Oztop I, Dirioz M, Yilmaz U. Quality of life, anxiety, and depression in Turkish colorectal cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2010;18:417–421. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0679-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro E, Dhruva A, Langford DJ, Koetters T, Merriman JD, West C, Dunn LB, Paul SM, Cooper B, Cataldo J, Hamolsky D, Elboim C, Kober K, Aouizerat BE, Miaskowski C. Associations between cytokine gene variations and self-reported sleep disturbance in women following breast cancer surgery. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2014;18:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barez M, Blasco T, Fernandez-Castro J, Viladrich C. A structural model of the relationships between perceived control and adaptation to illness in women with breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2007;25:21–43. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benight CC, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: the role of perceived self-efficacy. Behavioral Research and Therapy. 2004;42:1129–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brintzenhofe-Szoc KM, Levin TT, Li Y, Kissane DW, Zabora JR. Mixed anxiety/depression symptoms in a large cancer cohort: prevalence by cancer type. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:383–391. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner F, Bachmann LM, Weber U, Kessels AG, Perez RS, Marinus J, Kissling R. Complex regional pain syndrome 1--the Swiss cohort study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2008;9:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2005;330:702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung WY, Le LW, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C. Age and gender differences in symptom intensity and symptom clusters among patients with metastatic cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011;19:417–423. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Ustun BT, Stucki G. Identification of candidate categories of the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF) for a Generic ICF Core Set based on regression modelling. BMC Medical Research Methodologies. 2006;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Stoll MF, Thomsen AH, Oppedisano G, Epping-Jordan JE, Krag DN. Adjustment to breast cancer: age-related differences in coping and emotional distress. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 1999;54:195–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1006164928474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JV, Grunfeld EA. Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2013;22:978–986. doi: 10.1002/pon.3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver JL, Arena PL, Antoni MH, Carver CS. Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: comparing African Americans, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. Psychooncology. 2002;11:495–504. doi: 10.1002/pon.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C. Psychiatric morbidity following mastectomy: preoperative predictors and types of illness. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1987;31:385–392. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhruva A, Aouizerat BE, Cooper B, Paul SM, Dodd M, West C, Wara W, Lee K, Dunn LB, Langford DJ, Merriman JD, Baggott C, Cataldo J, Ritchie C, Kober K, Leutwyler H, Miaskowski C. Differences in morning and evening fatigue in oncology patients and their family caregivers. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2013;17:841–848. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LB, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J, West C, Paul S, Aouizerat B, Abrams G, Edrington J, Hamolsky D, Miaskowski C. Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2011;30:683–692. doi: 10.1037/a0024366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LB, Langford DJ, Paul SM, Berman MB, Shumay DM, Kober K, Merriman JD, West C, Neuhaus JM, Miaskowski C. Trajectories of fear of recurrence in women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2513-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epping-Jordan JE, Compas BE, Osowiecki DM, Oppedisano G, Gerhardt C, Primo K, Krag DN. Psychological adjustment in breast cancer: processes of emotional distress. Health Psychology. 1999;18:315–326. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Wisdom C, Wenzl C. Quality of life as an outcome variable in the management of cancer pain. Cancer. 1989;63:2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2321::aid-cncr2820631142>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J, Parle M, Cairns D. Appraisal and psychological distress six months after diagnosis of breast cancer. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7:365–376. doi: 10.1348/135910702760213733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedzinska AS, Meyerowitz BE, Ganz PA, Rowland JH. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:39–51. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl K, Engel J, Herschbach P, Reinecker H, Sommer H, Friese K. Personality traits and psychosocial stress: quality of life over 2 years following breast cancer diagnosis and psychological impact factors. Psychooncology. 2010;19:160–169. doi: 10.1002/pon.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henselmans I, Helgeson VS, Seltman H, de Vries J, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV. Identification and prediction of distress trajectories in the first year after a breast cancer diagnosis. Health Psychology. 2010;29:160–168. doi: 10.1037/a0017806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnen C, Ranchor AV, Sanderman R, Snijders TA, Hagedoorn M, Coyne JC. Course of distress in breast cancer patients, their partners, and matched control couples. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JS, Tian J. Prevalence of anxiety and depression and their risk factors in Chinese cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22:453–459. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1997-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter N, Vogel B, Alexander T, Baumeister H, Helmes A, Bengel J. Are depression and anxiety determinants or indicators of quality of life in breast cancer patients? Psychology Health and Medicine. 2013;18:412–419. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.736624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Hawley ST, Mujahid MS, Griggs JJ, Alderman A, Hamilton AS, Graff JJ, Jagsi R, Katz SJ. Correlates of worry about recurrence in a multiethnic population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1827–1836. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehn CF, Flath B, Strux A, Krebs M, Possinger K, Pezzutto A, Luftner D. Influence of age, performance status, cancer activity, and IL-6 on anxiety and depression in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2012;136:789–794. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RD. Depression and anxiety in oncology: the oncologist's perspective. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 8):52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008;2:302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Karakoyun-Celik O, Gorken I, Sahin S, Orcin E, Alanyali H, Kinay M. Depression and anxiety levels in woman under follow-up for breast cancer: relationship to coping with cancer and quality of life. Medical Oncology. 2010;27:108–113. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnofsky D. Performance scale. Plenum Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Roy-Byrne PP. Mixed anxiety and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:337–345. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BL, Schwab JJ, Morris RL, Beldia G. Assessment of state and trait anxiety in subjects with anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychiatry Quarterly. 2001;72:263–276. doi: 10.1023/a:1010305200087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS, National Comorbidity Survey, R. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ruscio AM, Shear K, Wittchen HU. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Current Topics in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;2:21–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Love A, Clarke DM, Bloch S, Smith GC. Psychiatric disorder in women with early stage and advanced breast cancer: a comparative analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;38:320–326. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyranou M, Puntillo K, Aouizerat BE, Dunn LB, Paul SM, Cooper BA, West C, Dodd M, Elboim C, Miaskowski C. Trajectories of depressive symptoms in women prior to and for six months after breast cancer surgery. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2014a;19:79–105. doi: 10.1111/jabr.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyranou M, Puntillo K, Dunn LB, Aouizerat BE, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Neuhaus J, West C, Dodd M, Miaskowski C. Predictors of initial levels and trajectories of anxiety in women before and for 6 months after breast cancer surgery. Cancer Nursing. 2014b;37:406–417. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam WW, Chan M, Ka HW, Fielding R. Treatment decision difficulties and post-operative distress predict persistence of psychological morbidity in Chinese women following breast cancer surgery. Psychooncology. 2007;16:904–912. doi: 10.1002/pon.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansky SB, List MA, Herrmann CA, Ets-Hokin EG, DasGupta TK, Wilbanks GD, Hendrickson FR. Absence of major depressive disorder in female cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1985;3:1553–1560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1985.3.11.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;141:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean CD, Littenberg B, Kennedy AG. Limitations of diabetes pharmacotherapy: results from the Vermont Diabetes Information System study. BMC Family Practice. 2006;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunsell E, Brisson J, Deschenes L. Psychological distress after initial treatment for breast cancer: a comparison of partial and total mastectomy. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1989;42:765–771. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann B, Miaskowski C, Koetters T, Baggott C, West C, Levine JD, Elboim C, Abrams G, Hamolsky D, Dunn L, Rugo H, Dodd M, Paul SM, Neuhaus J, Cooper B, Schmidt B, Langford D, Cataldo J, Aouizerat BE. Associations between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine genes and breast pain in women prior to breast cancer surgery. Journal of Pain. 2012;13:425–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.02.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means-Christensen AJ, Sherbourne CD, Roy-Byrne PP, Schulman MC, Wu J, Dugdale DC, Lessler D, Stein MB. In search of mixed anxiety-depressive disorder: a primary care study. Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23:183–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriman JD, Aouizerat BE, Cataldo JK, Dunn L, Cooper BA, West C, Paul SM, Baggott CR, Dhruva A, Kober K, Langford DJ, Leutwyler H, Ritchie CS, Abrams G, Dodd M, Elboim C, Hamolsky D, Melisko M, Miaskowski C. Association between an interleukin 1 receptor, type I promoter polymorphism and self-reported attentional function in women with breast cancer. Cytokine. 2014;65:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Elboim C, Paul SM, Mastick J, Cooper BA, Levine JD, Aouizerat BE. Polymorphisms in tumor necrosis factor alpha are associated with higher levels of anxiety in women following breast cancer surgery. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Cooper B, West C, Levine JD, Elboim C, Hamolsky D, Abrams G, Luce J, Dhruva A, Langford DJ, Merriman JD, Kober K, Baggott C, Leutwyler H, Aouizerat BE. Identification of patient subgroups and risk factors for persistent arm/shoulder pain following breast cancer surgery. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar K, Purushotham AD, McLatchie E, George WD, Murray GD. A 1-year prospective study of individual variation in distress, and illness perceptions, after treatment for breast cancer. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2005;58:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncology. 2011;12:160–174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CE, Danoff-Burg S. A review of age differences in psychological adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2005;23:101–114. doi: 10.1300/j077v23n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User's Guide. 6th ed. Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nosarti C, Roberts JV, Crayford T, McKenzie K, David AS. Early psychological adjustment in breast cancer patients: a prospective study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16:139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla GV, Grant MM. Quality of life as a cancer nursing outcome variable. Advances in Nursing Science. 1985;8:45–60. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla GV, Presant C, Grant MM, Metter G, Lipsett J, Heide F. Quality of life index for patients with cancer. Research in Nursing and Health. 1983;6:117–126. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker PA, Youssef A, Walker S, Basen-Engquist K, Cohen L, Gritz ER, Wei QX, Robb GL. Short-term and long-term psychosocial adjustment and quality of life in women undergoing different surgical procedures for breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2007;14:3078–3089. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P, Katon W, Broadhead WE, Lepine JP, Richards J, Brantley PJ, Russo J, Zinbarg R, Barlow D, Liebowitz M. Subsyndromal (“mixed”) anxiety--depression in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1994;9:507–512. doi: 10.1007/BF02599221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2003;49:156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan TJ, Fifield J, Reisine S, Tennen H. The measurement structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;64:507–521. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6403_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard VB, Harper FW, Davis K, Hirpa F, Makambi K. The importance of contextual factors and age in association with anxiety and depression in Black breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2014;23:143–150. doi: 10.1002/pon.3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, Ozakinci G. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2013;7:300–322. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer S, Das-Munshi J, Brahler E. Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care--a meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21:925–930. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan JA. Assessing the minimally clinically significant difference: scientific considerations, challenges and solutions. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2005;2:57–62. doi: 10.1081/copd-200053374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So WK, Marsh G, Ling WM, Leung FY, Lo JC, Yeung M, Li GK. Anxiety, depression and quality of life among Chinese breast cancer patients during adjuvant therapy. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010;14:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CG, Gorsuch RL, Suchene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Anxiety (Form Y): Self Evaluation Questionnaire. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS . IBM SPSS for Windows (Version 21) Armonk; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Krupnick JL, Sears SR. Promoting adjustment after treatment for cancer. Cancer. 2005;104:2608–2613. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BC, NandaMohan V, Nair MK, Pandey M. Gender, age and surgery as a treatment modality leads to higher distress in patients with cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2010;19:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0810-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, Enders CK. Identifying the correct number of classes in growth mixture models. Information Age Publishing; Charlotte, NC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Torres MA, Pace TW, Liu T, Felger JC, Mister D, Doho GH, Kohn JN, Barsevick AM, Long Q, Miller AH. Predictors of depression in breast cancer patients treated with radiation: Role of prior chemotherapy and nuclear factor kappa B. Cancer. 2013;1198:1951–1959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van't Spijker A, Trijsburg RW, Duivenvoorden HJ. Psychological sequelae of cancer diagnosis: a meta-analytical review of 58 studies after 1980. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:280–293. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Esch L, Roukema JA, Ernst MF, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, De Vries J. Combined anxiety and depressive symptoms before diagnosis of breast cancer. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Onselen C, Paul SM, Lee K, Dunn L, Aouizerat BE, West C, Dodd M, Cooper B, Miaskowski C. Trajectories of sleep disturbance and daytime sleepiness in women before and after surgery for breast cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2013;45:244–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo GJ, Levine EG, Pasick R. Breast cancer and coping among women of color: a systematic review of the literature. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22:811–824. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2057-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zbozinek TD, Rose RD, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Sherbourne C, Sullivan G, Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG. Diagnostic overlap of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder in a primary care sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:1065–1071. doi: 10.1002/da.22026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]