Abstract

The dentate gyrus (DG), a part of the hippocampal formation, has important functions in learning, memory, and adult neurogenesis. Compared to homologous areas in sauropsids (birds and reptiles), the mammalian DG is larger and exhibits qualitatively different phenotypes: (1) folded (C- or V-shaped) granule neuron layer, concave towards the hilus, delimited by a hippocampal fissure; (2) non-periventricular adult neurogenesis; and (3) prolonged ontogeny involving extensive abventricular (basal) migration and proliferation of neural stem and progenitor cells (NSPCs). Although gaps remain, available data indicate that these DG traits are present in all orders of mammals, including monotremes and marsupials. The exception is Cetacea (whales, dolphins, and porpoises), in which DG size, convolution, and adult neurogenesis have undergone evolutionary regression. Parsimony suggests that increased growth and convolution of the DG arose in stem mammals, concurrently with non-periventricular adult hippocampal neurogenesis, and basal migration of NSPCs during development. These traits could all result from an evolutionary change that enhanced radial migration of NSPCs out of the periventricular zones, possibly by epithelial-mesenchymal transition, to colonize and maintain non-periventricular proliferative niches. In turn, increased NSPC migration and clonal expansion might be a consequence of growth in the cortical hem (medial patterning center), which produces morphogens such as Wnt3a, generates Cajal-Retzius neurons, and is regulated by Lhx2. Finally, correlations between DG convolution and neocortical gyrification (or capacity for gyrification) suggest that enhanced abventricular migration and proliferation of NSPCs played a transformative role in growth and folding of neocortex, as well as archicortex.

Graphical abstract

Comparative analysis of amniotes shows that the mammalian dentate gyrus is distinguished by convolution and non-periventricular adult neurogenesis. Both features arose in stem mammals, by enhanced migration of intermediate progenitors (IPs) and radial glial progenitors (RGPs) in the embryonic dentate migration stream.

1. Introduction

The dentate gyrus (DG) is a trilaminar, semilunar (C-shaped) gyrus in the medial cortex (hippocampal formation) of mammals (Carpenter, 1976; Gall, 1990; Treves et al., 2008). Along with other areas of the hippocampal formation, the DG mediates important functions in learning and memory (Treves et al., 2008). The DG is the most medial area of the hippocampal formation, and therefore of the entire cerebral cortex (Nieuwenhuys, 1998; Puelles, 2001; Striedter, 2005; Medina and Abellán, 2009). The DG is also the central link in the classic hippocampal “trisynaptic circuit” that relays information from entorhinal cortex to DG to CA3 (Sloviter and Lømo, 2012). In the perforant path, first discerned by Cajal (1901–1902), axons from entorhinal cortex cross the partially fused hippocampal fissure and terminate in the DG molecular layer to synapse on granule neuron dendrites. In turn, DG efferent axons, known as mossy fibers, form prominent bundles that synapse on CA3 pyramidal neurons.

While the DG is in some ways well studied, its evolution to the mammalian form is poorly understood (Lindsey and Tropepe, 2006; Treves et al., 2008; Kempermann, 2012). In the classification of mammalian cortical regions, DG is designated as an area of archicortex, on the basis of its resemblance to reptilian medial cortex (Ariëns Kappers et al., 1936–1965; Carpenter, 1976; Striedter, 2005). Along with paleocortex (likewise 3-layered), archicortex is one form of allocortex (non-neocortex). In mammals, allocortex surrounds the neocortex, which arose from reptilian dorsal cortex like an island (Puelles, 2001, 2011; Medina and Abellán, 2009). While evolutionary growth and transformation of the neocortex are well known, it is less appreciated that evolution also transformed the mammalian archicortex, which came to contain a large, convoluted gyrus: the DG.

DG homolog areas have been identified on the basis of various criteria in lizard medial cortex (Marchioro et al., 2005), and in avian medial pallium (Gupta et al., 2012; Abellán et al., 2014). However, certain unique features of the mammalian DG suggest it underwent a transformative change in evolution from the primitive sauropsid form (Treves et al., 2008; Kempermann, 2012). The DG is larger and convoluted in mammals, but that is not the only difference. In addition, adult neurogenesis is a special DG phenotype that may have evolved in mammals (Treves et al., 2008; Kempermann, 2012; Aimone et al., 2014; Christian et al., 2014). Ontogeny of the mammalian DG is also unique (Li and Pleasure, 2007), and changes in ontogeny can be decisive in evolution (Striedter, 2005).

Considered together, the array of DG traits in development and adulthood present the opportunity for an integrated analysis of DG evolution. Using a comparative approach (Striedter, 2005; Kaas, 2013), this review defines multiple specific mammalian DG traits. From the results, a unifying hypothesis of DG evolution is proposed: that defining traits of the mammalian DG (convolution, adult neurogenesis, migration streams in ontogeny) evolved concurrently by a shared underlying mechanism, involving translocation of NSPCs to non-periventricular niches, possibly under the influence of increased cortical hem activity. Finally, it is observed that abventricular migration of NSPCs evolved concurrently in DG and neocortex of early mammals. Thus, DG morphogenesis may be an archetype of cortical gyrogenesis (Welker, 1990; Striedter, 2005; Sun and Hevner, 2014).

2. Laminar structure and axonal connections of the dentate gyrus (DG)

The DG and other hippocampal areas are classified as archicortex because of their trilaminar morphology, thought to resemble the primitive medial cortex of sauropsids. Indeed, mammalian DG bears striking similarities to lizard medial cortex (less so to avian medial pallium). Here, mammalian DG structure is briefly compared to reptile and bird medial cortex, in the context of evolutionary relationships (Fig. 1) defined by current understanding of phylogeny (O’Leary et al., 2013; Suzuki and Hirata, 2013; Striedter, 2015).

Figure 1.

Evolutionary history of amniotes and mammals. (A) Amniotes. Sauropsids (birds and reptiles) diverged from mammals approximately 350 million years ago. Adapted from Striedter (2015). (B) Mammals. Monotremes, marsupials, and placentals are the three main branches of mammals. After the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) meteor event ~65 million years ago, placental mammals radiated rapidly and diversely (O’Leary et al., 2013). Adapted from Suzuki and Hirata (2013).

2a. Organization of the mammalian DG

The mammalian DG has three histological layers, as seen in mouse (Fig. 2A). From superficial (nearest the pial surface or hippocampal fissure) to deep, they are: the molecular layer, the granule neuron layer, and the hilus, or polymorphic layer (Carpenter, 1976; Gall, 1990; Treves et al., 2008). The molecular layer and granule neuron layer together form the fascia dentata. This laminar pattern appears conserved among mammals (Gall, 1990; Treves et al., 2008; Patzke et al., 2015).

Figure 2.

Histology of the hippocampal region (medial pallium) in mammal, bird, and reptile. (A) The mouse DG is V-shaped, with suprapyramidal (SPB) and infrapyramidal (IPB) blades enclosing the hilus (hi). The molecular layer (ml) and granule neuron layer (gnl) together make up the fascia dentata. The fused hippocampal fissure (white arrow at pial surface) runs along the SPB (dashed line). Image from Allen Institute for Brain Science reference atlas (developingmouse.brain-map.org), P56. (B) The chick medial pallium is non-laminar. The proposed DG homolog in medial pallium is demarcated by lines. Image from Puelles et al. (2007). (C) The snake medial cortex (M) is trilaminar, with a middle layer of granule neurons. Among amniotes, the reptile medial cortex may resemble the primitive form most closely. Image from Ulinski (1990). (A–C): Coronal sections; Nissl stains; midline left, superior top. Scale bar, 0.5 mm (A–C).

While the laminar organization of DG seems simple, substratification and neuronal heterogeneity add complexity. The molecular layer contains few neurons (mainly inhibitory), but is comprised mainly of neuropil from granule neuron dendrites and afferent axons (Gall, 1990). Major afferent glutamatergic pathways innervate the outer two-thirds of the molecular layer from entorhinal cortex (perforant path), and the inner one-third from intrinsic DG hilar neurons (ipsilateral and contralateral association paths). The perforant and associational-commissural paths seem conserved among mammals (Gall, 1990).

The morphology of DG granule neurons is often described with one main dendrite that branches in the molecular layer, but more complex forms, including bipyramidal, are also seen (Gall, 1990; Treves et al., 2008). While granule neurons show limited morphologic variation, molecular expression levels (e.g., Prox1, calretinin, and calbindin) vary by cell age and position in the granule neuron layer (Hodge et al., 2013). Furthermore, the inner margin of the granule neuron layer, known as the subgranular zone (SGZ), is the site of adult neurogenesis, and contains neural stem cells (NSCs) in a specialized neurogenic niche (Ma et al., 2005; Christian et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014). Interneurons are also scattered in the granule neuron layer. The granule neurons in turn give rise to axons, descriptively called mossy fibers, which end in CA3 stratum lucidum and release glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter in this context.

The DG polymorph layer (hilus) contains excitatory (glutamatergic) and inhibitory (GABAergic) neurons. In some species, the hilus appears substratified, and it has been suggested that “the most conspicuous comparative differences in the organization of the dentate gyrus are to be found in the relative degree of stratification within the hilus” (Gall, 1990).

2b. The putative DG homolog in birds

In pioneering studies of bird telencephalon, Cajal (1904) noted “the absence of an Ammon’s horn or at least of a gray territory capable of being easily homologized with this center of the mammals.” More than a century later, Treves et al. (2008) likewise surmised that “the avian hippocampus seems to have taken a different evolutionary path,” reflecting ongoing uncertainties about homologies to mammalian hippocampal areas. Indeed, the medial pallium in birds (Fig. 2B) has no area with a compact granular cell layer, and many neurons are periventricular, unlike in mammals (Dubbeldam, 1998). Throughout the bird forebrain, areas of laminated cortex are small, and much of the avian pallium instead forms nuclear (non-laminar) aggregates (Ulinski and Margoliash, 1990; Puelles, 2001; Puelles et al., 2007). Confusingly, comparisons focusing on different neuronal features of the avian medial pallium (dendrite structure, axon connections, etc.) have produced sometimes conflicting interpretations (Kahn et al., 2003; Atoji and Wild, 2004, 2006; Puelles et al., 2007; Striedter, 2015). In the atlas of Puelles et al. (2007), the chick “DG primordium” was interpreted as “the simplified corticoid appendage at the fimbrial tip of the classical avian hippocampus,” which “is not displaced radially towards the pial surface as in mammals.”

Lately, new evidence of an avian DG homolog has come from molecular expression studies in developing chicks. Gene expression analyses determined that the bird medial pallium is broadly homologous to hippocampus (Puelles, 2001, 2011; Belgard et al., 2013). Furthermore, some areas of medial pallium were found to contain neurons with molecular properties of DG granule neurons, including specific Prox1 expression (Gupta et al., 2012; Abellán et al., 2014). On the basis of molecular data, the avian DG homolog was interpreted by one group as “the ventral V-shaped region” of medial pallium (Gupta et al., 2012), and by another as “a large part of the so-called avian hippocampus” excluding the dorsalmost V-shaped region (Abellán et al., 2014). While current evidence seems to point to a DG homolog in avian medial pallium, its precise boundaries and structure remain to be clarified, especially in adult birds.

2c. Medial cortex of reptiles

In contrast to birds, reptiles have prominent areas of laminar cortex. According to Ulinski (1990), “It is only in reptiles and mammals that the telencephalic roof develops into extensive and multilayered cortices.” The lizard medial cortex (or small celled part of mediodorsal cortex) was recognized as the DG homolog many years ago (Ariëns Kappers et al., 1936–1965), and is still sometimes referred to as the “reptilian fascia dentata” (Marchioro et al., 2005). The homology to DG has indeed been supported by many different authors using a variety of techniques (Ulinski, 1990; Luis de la Iglesia et al., 1994; Luis de la Iglesia and Lopez-Garcia, 1997a,b; ten Donkelaar, 1998; Marchioro et al., 2005).

The medial cortex in lizards, crocodiles, and snakes (Fig. 2C) has three layers (external plexiform, cellular, and inner plexiform) that histologically resemble the three layers of mammalian DG (Ulinski, 1990; Marchioro et al., 2005). Strikingly, principal neurons in the cellular layer exhibit “candelabra” and bipyramidal dendrite morphologies (Ulinski, 1990), remarkably similar to the dendrite morphologies of DG granule neurons in rodents and primates (Cajal, 1901–1902; Gall, 1990). The polymorphic neuronal composition of the medial cortex inner plexiform layer also resembles that of the DG hilus layer, even exhibiting stratification (Luis de la Iglesia and Lopez-Garcia, 1997b). The similarities do not end there: “on the grounds of their morphology, connectivity, immunocytochemical and histochemical properties, and late ontogenesis, medial cortex projection neurons closely resemble dentate granule cells” (Luis de la Iglesia and Lopez-Garcia, 1997a). [On the other hand, a new comparative analysis of axon connections finds less convincing evidence for a DG homolog in sauropsids (Striedter, 2015).]

Overall, the neuronal morphology and cytoarchitecture of reptilian medial cortex appear similar enough to mammalian DG that a common ancestral form with conserved neuronal composition and trilaminar organization can be inferred. These considerations support the conclusion that a DG precursor was present in the cortical bauplan of early amniotes, and retained certain recognizable features (morphologic and molecular) in derived lineages of reptiles, birds, and mammals.

3. Convolution of the DG

Convolution is a prominent histological feature of the DG in many mammals, such as rodents (Fig. 2A). Recent reviews have observed that this morphology is not present “below monotremes” (Kempermann, 2012), and have furthermore proposed that DG convolution is a mammalian innovation linked to evolutionary expansion of the DG and its functions (Treves et al., 2008). As shown in the following analysis, convolution of the DG is not only specific, but also characteristic of all mammals.

3a. The DG is convoluted in all mammals except cetaceans

In widely studied mammals such as rodents (Fig. 2A), convolution of the DG typically manifests as C- or V-shaped morphology, concave towards the hilus, bounded by the hippocampal fissure (Fig. 2A). How widespread are these features among different mammals, and what can DG convolution tell us about mammalian evolution?

Previous studies have documented DG convolution in monotremes, marsupials, and many placental mammals, suggesting that convolution arose in the earliest mammals (Ariëns Kappers et al., 1936–1965; Welker, 1990; Kempermann, 2012). On the other hand, very small DG size, relatively flat (unfolded) DG morphology, and rudimentary hippocampal fissure have been observed in cetaceans (dolphins, porpoises, and whales), raising the possibility of a simpler ancestral form of DG (Jacobs et al., 1979; Hof et al., 2005; Patzke et al., 2015). To evaluate the origins of DG convolution, a systematic analysis across mammalian orders is necessary.

Examination of coronal brain sections from diverse species in the Comparative Mammalian Brain Collections (CMBC) database (www.brainmuseum.org) revealed that DG convolution is prominent in mammals from all orders, except cetaceans. Among 17 main lineages of placental mammals (Fig. 1B), the CMBC data show that 15 exhibit prominent DG convolution (the DG of zebra, a Perissodactyla, shows convolution but is not included in this figure), 1 (Proboscidea) is not represented with brain sections in the CMBC, and 1 (Cetacea) displays a small DG with minimal convolution (Fig. 3). Separately, marked convolution of the proboscidean DG has been demonstrated in a study of African elephant hippocampus (Patzke et al., 2014). Thus, cetaceans appear to be an outlier among all placental mammals, as they are the only group with very small, minimally folded DG. Because of its unique structure, the cetacean DG is worth considering in more detail.

Figure 3.

Dentate gyrus convolution in diverse orders of placental mammals. For each panel, the major clade (bold) and name of each species are indicated. In different species, the hippocampus grows mainly in medial temporal (A, B, D, H, K, L), occipito-parietal (E, F, I, M, N), or combined (C, G, J, O) lobes. The dentate gyrus is much smaller in cetaceans (A) than in other orders. Scale bar: 5 mm (A–O). Nissl stained sections. Images in (B–O) from CMBC (www.brainmuseum.org); image in (A) courtesy of Dr. Patrick Hof.

The principal cetacean DG phenotypes of relatively small size and decreased convolution (Fig. 3A) have been documented in several species. Generally, the granule neuron layer is thin, has decreased surface area, and exhibits reduced or absent curvature (Jacobs et al., 1979; Hof et al., 2005; Patzke et al., 2015). In bottlenose dolphin, “the dentate gyrus (DG) appears unfolded compared to the situation in other mammals,” and the hippocampal fissure appears open, not fused (Hof et al., 2005). In harbor porpoise, the DG is small but slightly convoluted, and the hippocampal fissure appears open (Patzke et al., 2015). In minke whale, the small DG is slightly convoluted, and the hippocampal fissure appears closed (Patzke et al., 2015). Quantitatively, DG volume in cetaceans is much less than expected for brain size, by at least an order of magnitude (Patzke et al., 2015). Thus, despite its small size, rudimentary features of DG convolution and hippocampal fissure closure are nevertheless visible in some cetaceans.

The CMBC also contains brain sections from two monotremes (platypus and echidna), as well as more than a dozen marsupials (opossums, kangaroos, tasmanian devil), all of which exhibit DG convolution identical to that in placentals (Fig. 4). In the context of mammalian phylogeny (Fig. 1B), the presence of DG convolution in monotremes, marsupials, and all placental mammals (except cetaceans) indicates that the DG was convoluted in stem mammals. Since cetaceans are an infraorder of Artiodactyla (goats, camels, pigs, hippos, giraffes, deer), it seems likely that the DG regressed early in cetacean evolution, from the larger and more typical ancestral DG morphology seen in Artiodactyla and other mammals (Figs. 3, 4).

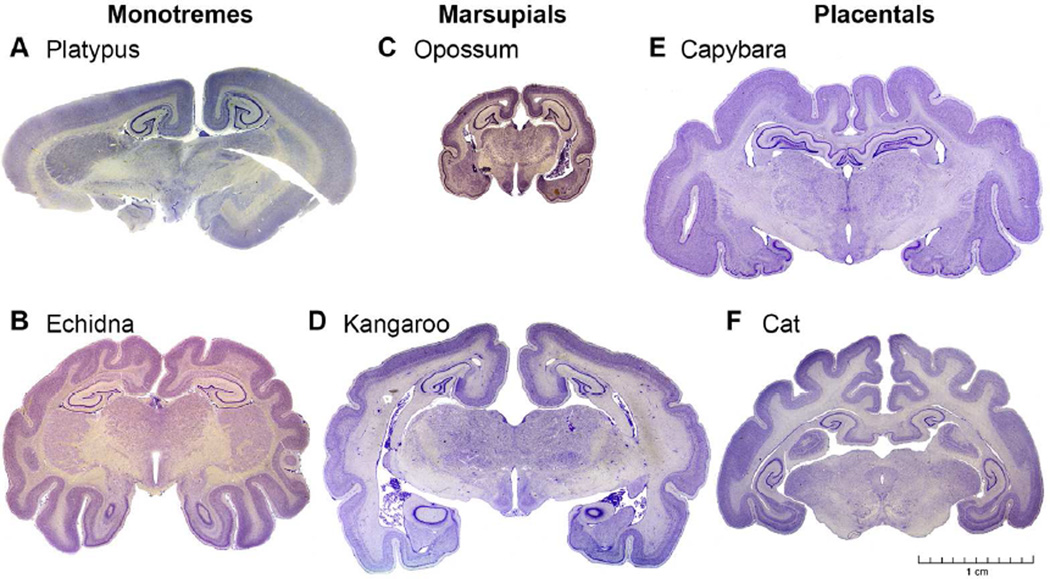

Figure 4.

Dentate gyrus convolution in monotremes, marsupials, and placental mammals. (A, B) Monotremes: platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) and echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus). (C, D) Marsupials: opossum (Didelphis virginiana) and kangaroo (Macropus fuliginosus). (E, F) Placentals: capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) and cat (Felis catus). Note that the neocortex is also convoluted in some representatives of each main branch of mammals. Scale bar: 1 cm (A–F). Nissl stained sections. Images from CMBC (www.brainmuseum.org).

3b. Sauropsid cortex lacks convolutions

After more than a century of comparative studies, no evidence of a convoluted medial cortex has been reported in birds, lizards, or other sauropsids. More specifically, none of the defining features associated with mammalian DG convolution (C/V-shaped, convex towards the hilus, present hippocampal fissure) are evident in non-mammals. The larger size, displacement towards the pial surface, and novel curvature of the mammalian DG indicate that medial cortex underwent a major expansion and reorganization in the transition to stem mammals from reptile-like ancestral amniotes. These comparative observations suggest that DG convolution arose in early mammals, prior to the divergence of monotremes and marsupials.

3c. Convolution evolved concurrently in DG and neocortex

Gyrification of the neocortex (gyrencephaly) is a salient anatomic feature of large mammalian brains, which serves to increase cortical surface area within the limited volume of the intracranial space (Zilles et al., 2013; Sun and Hevner, 2014). The amount of cortical folding (or gyrification index) is directly related to brain mass, although sulcal patterns also reflect phylogenetic relationships (Zilles et al., 2013). Outside mammals, convolutions are absent from any cortical regions, in even the largest sauropsid brains (Striedter, 2005).

Among diverse species, neocortical gyrification is much more variable than DG convolution, varying from smooth (lissencephaly) to extreme (gyrencephaly). Examples of gyrencephaly and lissencephaly are found in different species of most placental orders including primates, and in marsupials and monotremes (Rowe, 1990; Welker, 1990; Sun and Hevner, 2014). Indeed, examples of neocortical gyrencephaly in a monotreme, a marsupial, and a placental mammal are seen in Figure 4. Interestingly, the cetacean neocortex is extremely convoluted, and indeed cetaceans have the highest gyrification indices of all mammals, including primates (Zilles et al., 2013; Sun and Hevner, 2014).

The presence of gyrencephaly in monotremes, marsupials, and diverse placental mammals suggests that the capacity for neocortical gyrogenesis arose in stem mammals. One possibility is that stem mammals actually had a gyrified neocortex (Lewitus et al., 2014), as also proposed for the hypothetical placental ancestor (O’Leary et al., 2013). However, since lissencephaly is also common in extant mammals, another possibility might be that the key developmental mechanism(s) for gyrogenesis arose in stem mammals, which nevertheless remained lissencephalic, with actual gyrification evolving independently in diverse branches of mammals. Either way, stem mammals are directly implicated in the evolution of neocortical gyrification, which became a highly regulable trait linked to brain mass. Since neocortical gyrification has some structural and developmental similarities to DG convolution, the possibility of an overlapping evolutionary mechanism should be considered.

4. Adult neurogenesis in the DG

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is a type of structural and functional plasticity in the DG. First documented in rats (Altman and Das, 1965), adult hippocampal neurogenesis has since been confirmed in many species, including humans (Eriksson et al., 1998). Since adult neurogenesis is spatially restricted in mammals, and NSCs might serve purposes such as brain repair, much research has focused on mechanisms, functions, and disorders of adult hippocampal neurogenesis (Aimone et al., 2014; Christian et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014).

Adult neurogenesis is not unique to mammals, but occurs in the forebrain of many diverse vertebrate species, including reptiles and birds (Lindsey and Tropepe, 2006). Nevertheless, the subgranular zone (SGZ) niche in mammalian adult hippocampus is an evolutionary innovation that probably arose in stem mammals.

4a. Adult DG neurogenesis is conserved in mammals except cetaceans

The SGZ niche is located at the interface of granule cell and hilus layers (Ming and Song, 2005; Yu et al., 2014). The adult SGZ contains neural stem cells (NSCs) that resemble radial glial progenitors (RGPs) in the developing brain (Seri et al., 2004). The NSCs divide to produce new granule neurons or glia, through mechanisms that are regulated by diverse factors including physical activity, environmental enrichment, drugs, and hormones (Seri et al., 2004; Ming and Song, 2005). In contrast to the other niche for adult neurogenesis in mammals, known as the adult subventricular zone (SVZ), the SGZ is remote from the ventricular surface. NSCs in the SGZ do not contact the ventricles with a cytoplasmic process, as do NSCs in the SVZ (Alvarez-Buylla and Lim, 2004; Ma et al., 2005).

Recent studies have found that adult SGZ neurogenesis is widely present in diverse orders of marsupial and placental mammals, with the exception of cetaceans (Patzke et al., 2015). Adult neurogenesis has not been studied in monotremes. In the case of cetaceans, regression of DG size and convolution was evidently accompanied by loss of adult neurogenesis. This correlation suggests that DG growth and convolution are somehow linked to adult hippocampal neurogenesis. (Indeed, these traits may have a common developmental basis, as suggested below.) Since it is unknown if monotremes have adult DG neurogenesis, further studies will be necessary to confirm whether adult neurogenesis is present in all branches of mammals, and to confirm the proposed evolutionary linkage between DG convolution and adult SGZ neurogenesis. Currently, it is at least possible to say that the SGZ emerged as a niche for adult neurogenesis prior to the divergence of marsupial and placental lineages, more than 150 million years ago.

4b. Adult neurogenesis is periventricular in sauropsids

Adult neurogenesis has been widely documented in the forebrains of birds and reptiles, prompting some discussion of whether adult neurogenesis might be a primitive trait retained in the mammalian DG (García-Verdugo et al., 2002; Lindsey and Tropepe, 2006; Kaslin et al., 2008; Grandel and Brand, 2013). Adult neurogenesis in sauropsids can have impressive consequences: in some lizards, adult neurogenesis accounts for significant postnatal brain growth, and confers a remarkable capacity for medial cortex regeneration after injury (Molowny et al., 1995; Lopez-Garcia et al., 2002). However, considerations about the distinct sites of adult neurogenesis — periventricular and non-periventricular — have resurrected the idea that adult SGZ neurogenesis might be a novel adaptation in mammals after all (Lindsey and Tropepe, 2006).

In seminal studies of adult neurogenesis in songbirds, Alvarez-Buylla et al. (1990) found that cell proliferation “occurred almost exclusively in the walls of the lateral ventricle (telencephalon).” Further studies, including ultrastructure, showed that NSCs in adult birds physically contact the ventricular surface (Alvarez-Buylla et al., 1998). In lizards, postnatal and adult neurogenesis have been studied in forebrain areas such as the medial cortex (DG homolog), under a variety of conditions including regeneration after lesion. Under all conditions, the NSC niche in lizards is located in the ventricular wall (Lopez-Garcia et al., 1988; Molowny et al., 1995; Marchioro et al., 2005). These and other studies indicate that forebrain neurogenesis in sauropsids is restricted to the periventricular niche, in adult as well as developing brains (Lindsey and Tropepe, 2006).

Since the mammalian SGZ is non-periventricular, and sauropsids have only periventricular neurogenesis, it follows that the SGZ evolved as a new adult neurogenic niche in mammals. (In contrast, the adult mammalian SVZ is periventricular, and presumably homologous to the sauropsid periventricular niche.) Structurally, evolution of the SGZ represents a seismic dislocation of the neurogenic niche, to a distant site entirely within neural tissue, lacking the key neuroepithelial property of ventricular surface contact. One possible mechanism to explain how the SGZ evolved could be that NSPCs, perhaps accompanied by support cells, migrated away from the ventricular surface to colonize novel, non-periventricular niche compartments during development. As discussed in the next section, mammalian DG ontogeny involves just such migrations.

5. Ontogeny of the DG

Another salient trait of the mammalian DG is its unique, complex ontogeny. Although our knowledge of DG and medial cortex development is incomplete, especially among sauropsids, monotremes, and marsupials, enough is known to suggest that DG development was transformed in early mammals, by a novel process of NSPC migration out of the periventricular zone, and towards the basal (pial) surface. As changes in ontogeny may have fundamental consequences in brain evolution (Striedter, 2005), comparative studies of development may hold the key to understanding the evolution of adult DG phenotypes.

5a. DG development in mammals

Although unique in many ways, DG development shares some mechanisms with neocortical development. For example, GABAergic interneurons migrate to DG, as to neocortex, from subcortical progenitor compartments (Pleasure et al., 2000). Also in DG as in neocortex, glutamatergic projection neurons are produced locally from two main types of NSPCs, defined by distinct cellular and molecular properties: NSC-like RGPs, and transit-amplifying intermediate progenitors (IPs) committed to produce glutamatergic neurons (Rickmann et al., 1987; Hevner et al., 2006; Hodge et al., 2013; Sugiyama et al., 2013; Seki et al., 2014). Another commonality is that Reelin signaling regulates laminar organization of neurons in developing DG, as in neocortex (Stanfield and Cowan, 1979).

Despite the general similarities, specific features of DG development appear to be unique, including: (1) molecular expression, (2) migration of NSPCs in a histological stream, (3) hippocampal fissure formation, (4) extreme dependence on cortical hem signaling and Cajal-Retzius (C–R) neurons, and (5) prolonged neurogenesis. These developmental features, many visible from patterns of cell type-specific gene expression (Fig. 5), may provide clues to evolution of DG growth and convolution.

Figure 5.

DG ontogeny: migration of NSPCs in developing mouse DG, as revealed by cell type-specific markers. (A-F) E15.5 sagittal sections. (A) Nissl stain. (B) Tbr2 (marker of IPs and C-R neurons) is highly expressed in DNe and DMS (IPs), and in cortical hem (new C-R neurons). (C) Pax6 (RGPs) is expressed in the DNe and DMS, but not in cortical hem. (D) Reln (C-R neurons) is expressed in the cortical hem and hippocampal fissure, but not DNe or DMS. (E) Prox1 (granule neurons) is expressed in the primordium of granule neuron layer. (F) Summary diagram indicates cell types, DMS (green arrow), and C-R neuron migration (orange arrow). The data suggest that RGPs and IPs may both migrate in the DMS (see text for details). Scale bar (A): 200 µm (A–F). Images in (A–F) from Allen Institute for Brain Sciences (developingmouse.brain-map.org). (G) Postnatally, the DMS leads from the DNe to contiguous non-periventricular niches. P3 sagittal section, Tbr2 immunofluorescence (yellow) with DAPI counterstain (blue), produced as described (Hodge et al., 2013). During the peak of DG neurogenesis (P0-P7), Tbr2 is specifically expressed by IPs, which divide and migrate in multiple non-periventricular niches, including the DMS, fimbriodentate junction (FDJ), hilus (Hi), subpial neurogenic zone (SPNZ), and subgranular zone (SGZ).

Gene expression

Several region- or cell type-specific genes are expressed during sequential stages of DG development. In early stages, from embryonic day (E) 9.5 to E12.5 in mice, DG identity is specified in a narrow strip of pallium, known as the dentate neuroepithelium (DNe). The DNe exhibits high expression of Lef1, an important transcription factor downstream of Wnt signaling (Galceran et al., 2000). In Lef1 null mice, cortical patterning is defective, no DNe is specified, and no granule neurons are produced (Galceran et al., 2000). This phenotype illustrates the crucial importance of Wnt signaling in DG development (to be further discussed below). During later stages, granule neurons and precursors highly express Prox1 and Neurod1, transcription factor genes that regulate granule neuron differentiation (Liu et al., 2000; Iwano et al., 2012). Many other genes also contribute to the molecular code of hippocampal patterning and DG development (Mangale et al., 2008; Subramanian and Tole, 2009).

The dentate migration stream (DMS)

Shortly after the onset of neurogenesis (beginning ~E13.5 in mice), numerous mitotically active NSPCs exit the ventricular zone (VZ) and SVZ of the DNe, and migrate towards the nascent hippocampal fissure, where the DG will form. The migrating cells, which appear to be guided by a compact bundle of radial glial fibers at the medial edge of the DNe (Rickmann et al., 1987), align to form the histologically recognizable dentate migration stream (DMS), where migration and proliferation remain highly active during the first postnatal week in rodents (Altman and Bayer 1990a, 1990b). Due to increasing curvature and length of the radial glial guide fibers, the initially radial DMS acquires a tangential subpial component that is most prominent during late stages of DG morphogenesis (Rickmann et al., 1987).

In turn, the DMS feeds into other proliferation “matrices” (niches) that form at a distance from the VZ and SVZ of the DNe (Altman and Bayer, 1990a, 1990b; Sievers et al., 1992). Some of these niches include the fimbriodentate junction, the hilus, and the subpial neurogenic zone (SPNZ) in the prospective DG molecular layer (Sievers et al., 1992; Li et al., 2009; Hodge et al., 2013). Extensive migration of NSPCs in a stream, and seeding of non-periventricular niches for adult neurogenesis, are unique processes in DG development not found in any other cortical areas. The DMS and other niches contain both gliogenic and neurogenic progenitors, and are thought to produce “secondary” radial glial fibers that contribute to tangential DG growth and convolution by organizing the addition of radial columns (Rickmann et al., 1987; Sievers et al., 1992).

Another cell migration of potential significance in DG development and evolution, recently described by genetic lineage tracing in mice, involves NSC migration from a source in ventral hippocampus to dorsal hippocampus (Li et al., 2013). This migration is thought to seed the SGZ with NSCs for adult neurogenesis. This ventral-to-dorsal migration may augment NSC numbers in the dorsal DG. Hypothetically, if this migration arose in stem mammals, it could even be a main driver in the evolution of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. However, little is known about this ventral-to-dorsal NSC migration, and it has so far been described only in mice.

The hippocampal fissure

A key structure in DG morphogenesis, the hippocampal fissure has unique ontogeny and histology. Like other sulci, the hippocampal fissure has a pial surface and forms a morphological groove (Fig. 2). However, differently from other sulci, the hippocampal fissure is partially closed or “fused” with no free pial surface in its depths (except in some cetaceans with “open” hippocampal fissure; see above). Neural tissues are continuous in the fused depths of the hippocampal fissure, and perforant path axons from entorhinal cortex actually pass through the fused hippocampal fissure into the DG molecular layer (Cajal, 1901–1902).

Ontogeny of the hippocampal fissure has been studied mainly in humans and rodents. The hippocampal fissure in humans is visible beginning at 10 gestational weeks (Humphrey, 1967). By 13.5 gestational weeks, the subpial zone of the prospective hippocampal fissure thickens to form a “diffuse zone” with few cell bodies, also seen in some other species (Humphrey, 1967). As the hippocampal fissure grows, its “fused” or compact portion lengthens to extend progressively farther from the subpial diffuse zone (Humphrey, 1967). C-R neurons migrate into subpial (diffuse) and compact zones of the hippocampal fissure, and are essential for hippocampal fissure lengthening (Li et al., 2009; Hodge et al., 2013).

Some uncertainty remains about whether the hippocampal fissure is physically obliterated by fusion of opposing walls (potentially entrapping meningeal cells), or elongates by another process, such as progressive changes in the diffuse and compact zones. Favoring the latter hypothesis, the hippocampal fissure contains few meningeal cells, which are mainly associated with blood vessels (Humphrey, 1967), and radial glial end-feet do not terminate at the hippocampal fissure (Eckenhoff and Rakic, 1984; Rickmann et al., 1987). Although its development is still poorly understood, the hippocampal fissure plays an essential part in DG ontogeny, and perhaps evolution as well.

The cortical hem and C-R neurons

During early stages of cortical development, the neuroepithelium is patterned by signals from the cortical hem, an organizer located along the edge of the telencephalic vesicle, immediately adjacent and medial to the DNe (Subramanian and Tole, 2009). The cortical hem produces Wnt and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) factors that are required to promote DG identity, and to pattern areas of hippocampus and neocortex in conjunction with other signaling centers (Shimogori et al., 2004; Caronia et al., 2010; Caronia-Brown et al., 2014).

The cortical hem is not only a patterning center, but also a primary source of Cajal-Retzius (C–R) neurons. The C-R neurons migrate from the hem and into the marginal zone, where they disperse widely throughout the cortex and produce Reelin, an extracellular signaling protein (Yoshida et al., 2006). Initially, the DMS runs parallel to, and mixes with the tangential subpial migration of C-R neurons (Hodge et al., 2013). C-R neurons disperse throughout the hippocampal fissure, and promote DG morphogenesis by Reelin-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Li et al., 2009; Hodge et al., 2013). Thus, while all cortical areas are influenced by the cortical hem and C-R neurons, the DG is especially dependent on these elements for patterning, growth, and morphogenesis. So, evolutionary changes in the cortical hem and C-R neurons should be considered candidate factors in DG evolution.

Prolonged neurogenesis and clonal expansion

In mice, neurogenesis of DG granule neurons begins as early as E10.5 or E11.5 (Angevine, 1965; Stanfield and Cowan, 1979), almost simultaneously with neocortical neurogenesis which begins on E10.5 (Hevner et al., 2003). However, DG granule cell neurogenesis is minimal during early stages, and increases massively in later stages representing the peak of DG neurogenesis (during the first postnatal week in rodents), which occurs after neocortical neurogenesis has already ceased. Thereafter, developmental DG neurogenesis merges seamlessly into juvenile and adult SGZ neurogenesis, making DG neurogenesis a late-peaking, protracted process (Li and Pleasure, 2007; Yu et al., 2014). The prolonged genesis of DG granule neurons is associated with tremendous clonal expansion from DG progenitors, at least 10-fold greater than the expansion of progenitors for hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Martin et al., 2002).

During DG neurogenesis, several non-periventricular niches (such as the SPNZ) become visible histologically, and remain active until several weeks of age, when neurogenesis finally becomes restricted to the SGZ. The SGZ first becomes distinct as a neurogenic niche around the time of birth in rodents (Altman and Bayer, 1990b; Yu et al., 2014), or in the last quarter of gestation in monkeys (Eckenhoff and Rakic, 1988). Thus, although linked to adult neurogenesis, the SGZ originates as a developmental niche.

In sum, the mammalian DG exhibits unique traits during ontogeny, which can be compared between mammalian and non-mammalian species to understand DG evolution.

5b. Ontogeny of sauropsid medial cortex

Studies of medial cortex development in birds and reptiles, though few, have begun to reveal similarities and differences from mammalian hippocampal development. In birds, patterns of specific developmental gene expression have been instrumental in identifying DG homologous regions. For example, expression of Prox1, a specific marker of DG granule neurons in mice, was specifically detected in areas of chick medial pallium (Gupta et al., 2012; Abellán et al., 2014). Interestingly, Lef1, a transcription factor gene important in Wnt signaling and DG development in mice (Galceran et al., 2000), is also highly expressed in chick medial pallium (Abellán et al., 2014).

Despite some similarities of gene expression, development of the medial pallium in sauropsids appears otherwise quite different from the DG in mammals. The DG homolog in birds and reptiles is overall smaller (Cabrera-Socorro et al., 2007; Abellán et al., 2014), the pool of NSPCs is fewer (Charvet, 2010), and neurogenesis is strictly periventricular, with no DMS or other sign of NSPC migration (Gupta et al., 2012). Also, in contrast to developing mammalian DG, radial glial fibers in chick DNe do not curve tangentially along the hippocampal fissure (which does not form in sauropsids), but instead show short radial organization (Gupta et al., 2012; Abellán et al., 2014).

The cortical hem in lizards and birds has been described as “rudimentary” (Cabrera-Socorro et al., 2007) and “very tiny” (Medina and Abellán, 2009), respectively. Cortical hem-specific markers, such as cWnt8b, are expressed in chicks but demonstrate a smaller cortical hem (Abellán et al., 2014). Also, C-R neurons, which are produced by the cortical hem in mammals (Yoshida et al., 2006), seem much less developed in sauropsids than in mammals. Cells with typical C-R neuron morphology are present in bird and reptile cortex, but express lower levels of Reelin, and are less abundant than in mammalian cortex (Tissir et al., 2003; Cabrera-Socorro et al., 2007; Nomura et al., 2008; Medina and Abellán, 2009; Martínez-Cerdeño and Noctor, 2014).

6. Hypotheses of DG evolution

The evidence from comparative analysis suggests that principal traits of the mammalian DG (convolution, non-periventricular neurogenesis, and developmental migration of NSPCs) evolved rapidly and jointly in the transition from “reptilian” ancestors to stem mammals (Table 1). Furthermore, the adult DG phenotypes of convolution and adult neurogenesis may be functionally linked to the establishment of non-periventricular niches during development, in turn a consequence of enhanced NSPC migration (Fig. 6). From these observations, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that, in the medial cortex (DNe homolog) of stem mammals, NSPCs gained a new ability to detach from the ventricular surface (possibly by EMT), migrate towards the pial surface, and maintain non-periventricular, NSC-containing niches. By establishing a series of transient and persistent niches, NSPCs would be able to proliferate longer, produce cortex farther from the ventricular surface, and generate curved cortex (Fig. 6C). According to this model, abventricular migration and prolonged proliferation of NSPCs would have potentiated DG growth and convolution, by providing a mechanism for the DG to “mushroom” away from the ventricular surface (Welker, 1990). In turn, fundamental changes to NSPC migration may have been accompanied, and perhaps driven, by evolutionary expansion of the cortical hem, and by ensuing increased migration and activity of C-R neurons in the hippocampal fissure.

Table 1.

Dentate gyrus traits in reptiles, birds, and main groups of mammals

| Trait | Reptiles (medial cortex) |

Birds (medial pallium) |

Monotremes | Marsupials | Placentals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult DG | |||||

| Trilaminar | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Granule neurons | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Convolution (incl. HFi) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Non-PV neurogenesis | No | No | ? | Yes | Yes |

| DG ontogeny | |||||

| Basal migration NSPCs | No | No | ? | ? | Yes |

| Non-PV niches | No | No | ? | ? | Yes |

| Prox1, other genes | ? | Yes | ? | ? | Yes |

| Cortical hem | Tiny | Tiny | ? | ? | Prominent |

| Cajal-Retzius neurons | Few | Few | ? | ? | Abundant |

| Clonal expansion | Low | Low | ? | ? | High |

Abbreviations: HFi, hippocampal fissure; Non-PV, non-periventricular. Other abbreviations as in text.

Figure 6.

Proposed evolutionary changes in development of the mammalian DG, which led to principal phenotypes of convolution and adult neurogenesis. (A) Early embryonic DG development (mouse E11.5, coronal forebrain): Increased size of the cortical hem (Cx Hem) patterning center, and increased potential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) throughout cortical neuroepithelium, especially DNe. (B) Late embryonic DG development (mouse E16.5, sagittal hippocampus): Stream migration of NSPCs [including IPs (green) and RGPs (red)] in the DMS (light green shading), and increased abundance of C-R neurons (orange). (C) Postnatal DG development (mouse P4, sagittal hippocampus): Prolonged neurogenesis and maintenance of non-periventricular niches, with continued insertion of radial glial fibers (red lines) to organize the addition of new DG columns and thus promote convolution.

NSPC migration as a type of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

The pallial neuroepithelium exhibits classic epithelial properties, such as apical-basal polarity (Taverna et al., 2014; Singh and Solecki, 2015). Migration of epithelial cells is typically accomplished by epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which has indeed been implicated in basal migration of IPs in neocortex (Itoh et al., 2013). Basal migration of IPs is induced by upregulation of Scrt2, a transcription factor gene that promotes EMT (Itoh et al., 2013). In the developing DG, it appears that not only IPs, but also basal RGPs may undergo a form of partial EMT, involving loss of apical adherens junctions in the VZ to permit abventricular migration. So, it seems possible that an enhanced capacity for EMT by cortical NSPCs may have been a key factor in mammalian DG evolution.

The abventricular migration of NSPCs may have been driven by increased Wnt signaling, known to induce basal progenitors in neocortex (Kuwahara et al., 2010). Since the DNe is adjacent to the cortical hem, which secretes multiple Wnt molecules (Shimogori et al., 2004; Subramanian and Tole, 2009), evolutionary expansion of the cortical hem in mammals may have augmented differentiation and basal migration of NSPCs, especially in conjunction with an enhanced underlying proclivity for EMT.

Expansion of the cortical hem and C-R neurons, and the role of Lhx2

Increased size of the mammalian cortical hem (Cabrera-Socorro et al., 2007; Medina and Abellán, 2009) appears to be a critical factor that might control multiple DG phenotypes. First, patterning influences from the cortical hem may have led to larger areas of hippocampus being specified as DNe in the pallial primordium, thus augmenting growth (although the DNe is still relatively small in mammals). Second, higher levels of Wnt signaling may have promoted basal migration of NSPCs (Kuwahara et al., 2010; Itoh et al., 2013). Third, increased production and enhanced migration of specialized C-R neurons from the mammalian cortical hem may have had multiple effects on DG morphogenesis as well. In mammals, C-R neurons migrate from the cortical hem, accumulate in the expanding hippocampal fissure, and promote DG convolution (Li et al., 2009; Hodge et al., 2013). Furthermore, the C-R neuron migration path runs parallel to, and overlaps with, the early DMS, suggesting that C-R neurons may help create a supportive environment for NSPC migration. Abundance of C-R neurons in mammals may promote migration of neurons as well. In birds, experimentally induced augmentation of Reelin+ C-R neurons promotes radial migration of neurons (Nomura et al., 2008). Thus, the evolution of C-R neurons may have profoundly influenced not only laminar organization of neocortex (Cabrera-Socorro et al., 2007), but also several aspects of DG morphogenesis.

How might expansion of the cortical hem have occurred during early mammalian evolution? A possible genetic regulatory mechanism is suggested by studies of Lhx2, a LIM-homeobox transcription factor gene expressed in the developing cerebral cortex during patterning. In mice lacking Lhx2, the cortical hem is vastly expanded, indeed at the expense of medial and dorsal cortex, indicating “a role for Lhx2 in the regulation of the extent of the cortical hem” (Bulchand et al., 2001). Furthermore, timed inactivation of Lhx2 causes partial, sometimes patchy expansion of the cortical hem, leading to ectopic and expanded hippocampal fields (Mangale et al., 2008). The latter studies confirmed that “the cortical hem is a hippocampal organizer” regulated by Lhx2. In chicks, cLhx2 is likewise expressed throughout pallial cortex, but little or not at all in the cortical hem (Abellán et al., 2014). Thus, in mammals, increased growth of the cortical hem might have evolved by shifting the boundary of high Lhx2 expression to slightly more lateral positions in the telencephalic vesicle, thereby expanding the area of Lhx2-negative cortical hem. Genes that regulate or interact with Lhx2 might be important in this process.

Prolonged neurogenesis and niche maintenance

Mammalian DG evolution was linked to prolongation of NSPC proliferation and clonal expansion, in non-periventricular niches that may be transient or persist into adulthood. This radical transformation of DG neurogenesis presumably involved some evolutionary changes to NSPCs themselves (e.g., enhanced self-renewal and proclivity for EMT), but changes in other cell types and tissue components may have been equally necessary, especially for the purpose of establishing and maintaining supportive NSC niches outside the periventricular zone. Thus, it may be worthwhile to examine how basal (non-periventricular) niches in the developing DG differ from basal compartments in the developing neocortex, where migration out of the periventricular zones is usually accompanied by cell cycle exit and neuronal fate commitment — at least in mice (Itoh et al., 2013; Taverna et al., 2014).

Delta-Notch signaling and niche maintenance

Of central importance in NSC maintenance, Delta-Notch signaling is mediated by cell-cell contacts between NSCs and other niche cells, such as neurons and IPs (Kageyama et al., 2009; Imayoshi and Kageyama, 2011; Pierfelice et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2013). NSCs express Notch receptor proteins at the cell surface, and require Delta-like ligands from the surface of adjacent cells to bind and activate Notch, and thereby maintain NSC identity. In developing neocortex, one important source of Delta-like ligands is IPs, which express Delta-like genes Dll1 and Dll3, as well as the Delta activating gene mindbomb-1 (Mib1) (Kawaguchi et al., 2008; Yoon et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2013). Furthermore, cytoplasmic processes from IPs contact RGPs dividing at the ventricular surface to mediate Delta-Notch signaling and maintain NSC fates in the VZ (Nelson et al., 2013). In the developing and adult DG, IPs are abundant in the DMS and other non-periventricular niches, including the SGZ (Hodge et al., 2008, 2013), where they could be important sources of Delta-like signals. According to this model, extensive basal migration of IPs in the DMS may “pave the way” for NSCs to exit the periventricular niche, by providing supportive non-periventricular environments rich in Delta-like signals. Other factors in prolonged neurogenesis and niche maintenance might include signals from the cortical hem, and other neural or vascular elements.

Outer (basal) radial glia in DG evolution

Radial glial fibers are an essential organizing principle in cortical evolution and development (Rakic, 1988). During DG development, radial glial fibers not only curve, but also increase numerically within the expanding fascia dentata, by a process of new radial fiber intercalation or accretion among existing fibers (Eckenhoff and Rakic, 1984; Rickmann et al., 1987; Sievers et al., 1992; Brunne et al., 2010). During DG development, many RGPs divide in the DMS and other non-periventricular DG niches (Rickmann et al., 1987; Sievers et al., 1992), and thus resemble NSC-like outer (basal) RGPs as described in developing neocortex, both morphologically and molecularly (Lui et al., 2011; Shitamukai et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). The basal RGPs appear to produce “secondary” radial glia that help organize the DG scaffold (Sievers et al., 1992; Brunne et al., 2010). Thus, basal RGP-like cells not only produce IPs and neurons, but also new glial fibers to organize new radial columns for tangential expansion of the DG. In this way, basal migration of NSPCs provides all of the cellular elements necessary for gyral growth and expansion at the pial and hippocampal fissure surfaces.

In sum, evolution of the DG in stem mammals involved a fundamental transformation of neurogenesis, with extensive basal migration of NSPCs to establish non-periventricular niches and prolonged neurogenesis, while new radial columns were added to the granule neuron layer by intercalation and accretion of radial glia and neurons. Changes in NSPC migration and DG growth were augmented by expansion of the cortical hem and C-R neurons, potentially as a result of restricted Lhx2 expression.

7. Is DG convolution relevant to neocortical gyrification?

As discussed above, neocortical gyrification appears to have evolved at about the same time as DG convolution in stem mammals. The evolution of folding in different regions of cortex at the same time could be parallel evolution, but might also reflect a novel mechanism of development arising in pallial regions that generate both archicortex and neocortex. The latter explanation seems more parsimonious, because a single evolutionary change is postulated, rather than two independent changes in different cortical regions. So, what developmental innovation in stem mammals could account for the evolution of folding in multiple cortical regions?

One developmental mechanism that may have evolved concurrently in DG and neocortex is abventricular migration of NSPCs. As in developing DG, abventricular migration of IPs and outer/basal RGPs has also been described in developing neocortex, and such migrations appear especially prominent beneath prospective gyri (Kriegstein et al., 2006; Lui et al., 2011). Outer/basal RGPs are abundant in gyrus-forming neocortex, but are also present (in fewer numbers) in lissencephalic neocortex, such as mouse (Shitamukai et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). In contrast, basal IPs are abundant in lissencephalic as well as gyrencephalic cortex, but migrate farther from the ventricular surface beneath prospective gyri in gyrencephalic brains (Kriegstein et al., 2006). Basal IPs also appear to be more abundant in mammals than in sauropsids (Martínez-Cerdeño et al., 2006; Cheung et al., 2007; Molnár, 2011; Martínez-Cerdeño et al., 2015).

Based on such findings, recent hypotheses have proposed that neocortical gyri develop by enhanced local proliferation and basal migration of NSPCs (Kriegstein et al., 2006; Martínez-Cerdeño et al., 2006; Lui et al., 2011; Borrell and Götz, 2014; Lewitus et al., 2014). Migrating NSPCs in neocortex do not form histological streams like the DMS, but are rather more dispersed in the outer SVZ. Nevertheless, outer/basal RGPs in neocortex appear to migrate and proliferate in close proximity to IPs, as in developing DG. Neocortical IPs may have a role maintaining transient NSC niches in the outer SVZ, as in periventricular zones (VZ and SVZ) of developing neocortex (Nelson et al., 2013), and as proposed in developing DG. Like DG, neocortical gyri require the addition of new radial glial fibers as the cortical surface expands, and existing fibers diverge (Welker, 1990; Borrell and Götz, 2014).

Taken together, the available data suggest that the capacity for well-regulated abventricular migration and proliferation of NSPCs evolved concurrently in DG and neocortex, thus creating a new, non-periventricular mechanism for radial and tangential growth of cortex to produce gyri and sulci, and thereby increase the cortical surface area efficiently within the constrained intracranial volume. Theoretically, further elaboration of this mechanism could increase branching of gyri to produce neocortical lobules and lobes, consistent with the view that neocortical gyrification is regulable and can be rapidly increased or decreased in evolution (Welker, 1990). While DG convolution is more consistent than neocortical gyrencephaly across different species of mammals, the apparent regression of hippocampal size and DG folding in cetaceans indicates that archicortical folding and surface area are likewise regulable evolutionarily.

8. Future directions for research on DG evolution

Additional comparative studies of DG (or medial cortex/pallium) development in mammalian and sauropsid brains are needed, with particular attention to NSPC migrations, EMT, and cortical hem regulation. Because of their ancient divergence from placental mammals, marsupials and monotremes have special importance in comparative studies, yet little is known about the cortical hem and DG development in non-placental mammals. Comparative studies in adult animals will also be valuable, especially to study the SGZ niche and adult neurogenesis. For example, it remains unknown whether monotremes have adult SGZ neurogenesis.

Experimentally, it would be interesting to examine links between Wnt signaling, DG specification, NSPC migration, and non-periventricular neurogenesis. For example, might it be possible to induce some features of mammalian DG development in chick or lizard medial cortex, by treating the developing brain with Wnt or other molecules to mimic increased size of the cortical hem? Methodologically, this might be accomplished by implanting beads soaked with diffusible Wnt molecules (or agonists) at different sites around the developing sauropsid cortex (especially in the midline interhemispheric fissure), or by focal electroporation of Wnt expression plasmids. Since the cortical hem produces multiple factors in the Wnt and BMP families, it might be necessary to use combinations of factors to emulate signaling from the cortical hem. Along the same lines, might increased size of the cortical hem, and some features of DG growth, be induced in sauropsids by focal knockdown of Lhx2?

Finally, we are only beginning to understand the implications of DG evolution and development for human brain functions and disorders. For example, malformations of hippocampal development are associated with epilepsy and cognitive problems, but little is known about how hippocampal malformations occur, or the potential for repair by regulation of endogenous NSPCs. The potential for neuroregeneration using endogenous NSPCs needs to be further developed, to ultimately see if areas of human cortex can be stimulated to regenerate, perhaps even to the remarkable potential seen in lizards (Molowny et al., 1995; Lopez-Garcia et al., 2002). By comparing neurogenesis in our own species and others, we may learn how to enhance the process for treatment purposes.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Patrick Hof (Mount Sinai School of Medicine) provided the image of dolphin hippocampus (Fig. 3A).

Supported by NIH grants R21MH087070, R01MH080766, and R01NS085081.

Literature Cited

- Abellán A, Desfilis E, Medina L. Combinatorial expression of Lef1, Lhx2, Lhx5, Lhx9, Lmo3, Lmo4, and Prox1 helps to identify comparable subdivisions in the developing hippocampal formation of mouse and chicken. Front. Neuroanat. 2014;8:59. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimone JB, Li Y, Lee SW, Clemenson GD, Deng W, Gage FH. Regulation and function of adult neurogenesis: from genes to cognition. Physiol. Rev. 2014;94:991–1026. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Mosaic organization of the hippocampal neuroepithelium and the multiple germinal sources of dentate granule cells. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990a;301:325–342. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Migration and distribution of two populations of hippocampal granule cell precursors during the perinatal and postnatal periods. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990b;301:365–381. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1965;124:319–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA. For the long run: maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron. 2004;41:683–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Theelen M, Nottebohm F. Proliferation “hot spots” in adult avian ventricular zone reveal radial cell division. Neuron. 1990;5:101–109. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90038-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, García-Verdugo JM, Mateo AS, Merchant-Larios H. Primary neural precursors and intermitotic nuclear migration in the ventricular zone of adult canaries. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:1020–1037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-01020.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angevine JB., Jr Time of neuron origin in the hippocampal region. An autoradiographic study in the mouse. Exp. Neurol. 1965;2(Suppl.):1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariëns Kappers CU, Huber GC, Crosby EC. The Comparative Anatomy of the Nervous System of Vertebrates, Including Man. New York: Hafner Publishing; 1936–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Atoji Y, Wild JM. Fiber connections of the hippocampal formation and septum and subdivisions of the hippocampal formation in the pigeon as revealed by tract tracing and kainic acid lesions. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004;475:426–461. doi: 10.1002/cne.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atoji Y, Wild JM. Anatomy of the avian hippocampal formation. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;17:3–15. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2006.17.1-2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgard TG, Montiel JF, Wang WZ, García-Moreno F, Margulies EH, Ponting CP, Molnár Z. Adult pallium transcriptomes surprise in not reflecting predicted homologies across diverse chicken and mouse pallial sectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:13150–13155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307444110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell V, Götz M. Role of radial glial cells in cerebral cortex folding. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2014;27:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunne B, Zhao S, Derouiche A, Herz J, May P, Frotscher M, Bock HH. Origin, maturation, and astroglial transformation of secondary radial glial cells in the developing dentate gyrus. Glia. 2010;58:1552–1569. doi: 10.1002/glia.21029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulchand S, Grove EA, Porter FD, Tole S. LIM-homeodomain gene Lhx2 regulates the formation of the cortical hem. Mech. Dev. 2001;100:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00515-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Socorro A, Hernandez-Acosta NC, Gonzalez-Gomez M, Meyer G. Comparative aspects of p73 and Reelin expression in Cajal-Retzius cells and the cortical hem in lizard, mouse and human. Brain Res. 2007;1132:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajal SRy. Studies on the human cerebral cortex IV: Structure of the olfactory cerebral cortex of man and mammals. In: DeFelipe J, Jones EG, editors. Cajal on the Cerebral Cortex: An Annotated Translation of the Complete Writings. New York: Oxford University Press; 1901–1902. pp. 289–362. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cajal SRy. Comparative structure of the cerebral cortex: Cortex of small mammals; cortex of birds, reptiles, batrachians, [and fish] In: DeFelipe J, Jones EG, editors. Cajal on the Cerebral Cortex: An Annotated Translation of the Complete Writings. New York: Oxford University Press; 1904. pp. 437–452. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Caronia G, Wilcoxon J, Feldman P, Grove EA. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling in the developing telencephalon controls formation of the hippocampal dentate gyrus and modifies fear-related behavior. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:6291–6301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0550-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caronia-Brown G, Yoshida M, Gulden F, Assimacopoulos S, Grove EA. The cortical hem regulates the size and patterning of neocortex. Development. 2014;141:2855–2865. doi: 10.1242/dev.106914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MB. Chapter 18: Olfactory Pathways, Hippocampal Formation and Amygdala. 7th Ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1976. Human Neuroanatomy; pp. 521–546. [Google Scholar]

- Charvet CJ. A reduced progenitor pool population accounts for the rudimentary appearance of the septum, medial pallium and dorsal pallium in birds. Brain Behav. Evol. 2010;76:289–300. doi: 10.1159/000322102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AF, Pollen AA, Tavare A, DeProto J, Molnár Z. Comparative aspects of cortical neurogenesis in vertebrates. J. Anat. 2007;211:164–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian KM, Song H, Ming GL. Functions and dysfunctions of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;37:243–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbeldam JL. Birds. In: Nieuwenhuys R, ten Donkelaar HJ, Nicholson C, editors. The Central Nervous System of Vertebrates, Vol. 3: Chapter 21. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1998. pp. 1525–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Eckenhoff MF, Rakic P. Radial organization of the hippocampal dentate gyrus: a Golgi, ultrastructural, and immunocytochemical analysis in the developing rhesus monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 1984;223:1–21. doi: 10.1002/cne.902230102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenhoff MF, Rakic P. Nature and fate of proliferative cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus during the life span of the rhesus monkey. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:2729–2747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02729.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Bjork-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galceran J, Miyashita-Lin EM, Devaney E, Rubenstein JL, Grosschedl R. Hippocampus development and generation of dentate gyrus granule cells is regulated by LEF1. Development. 2000;127:469–482. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall C. Comparative anatomy of the hippocampus: with special reference to differences in the distributions of neuroactive peptides. In: Jones EG, Peters A, editors. Cerebral Cortex, Volume 8B: Comparative Structure and Evolution of the Cerebral Cortex, Part II: Chapter 12. New York: Plenum; 1990. pp. 167–213. [Google Scholar]

- García-Verdugo JM, Ferrón S, Flames N, Collado L, Desfilis E, Font E. The proliferative ventricular zone in adult vertebrates: a comparative study using reptiles, birds, and mammals. Brain Res. Bull. 2002;57:765–775. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandel H, Brand M. Comparative aspects of adult neural stem cell activity in vertebrates. Dev. Genes Evol. 2013;223:131–147. doi: 10.1007/s00427-012-0425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Maurya R, Saxena M, Sen J. Defining structural homology between the mammalian and avian hippocampus through conserved gene expression patterns observed in the chick embryo. Dev. Biol. 2012;366:125–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Daza RA, Rubenstein JL, Stunnenberg H, Olavarria JF, Englund C. Beyond laminar fate: toward a molecular classification of cortical projection/pyramidal neurons. Dev. Neurosci. 2003;25:139–151. doi: 10.1159/000072263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Hodge RD, Daza RA, Englund C. Transcription factors in glutamatergic neurogenesis: conserved programs in neocortex, cerebellum, and adult hippocampus. Neurosci. Res. 2006;55:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge RD, Kowalczyk TD, Wolf SA, Encinas JM, Rippey C, Enikolopov G, Kempermann G, Hevner RF. Intermediate progenitors in adult hippocampal neurogenesis: Tbr2 expression and coordinate regulation of neuronal output. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:3707–3713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4280-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge RD, Garcia AJ3rd, Elsen GE, Nelson BR, Mussar KE, Reiner SL, Ramirez JM, Hevner RF. Tbr2 expression in Cajal-Retzius cells and intermediate neuronal progenitors is required for morphogenesis of the dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:4165–4180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4185-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof PR, Chanis R, Marino L. Cortical complexity in cetacean brains. Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 2005;287:1142–1152. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey T. The development of the human hippocampal fissure. J. Anat. 1967;101:655–676. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imayoshi I, Kageyama R. The role of Notch signaling in adult neurogenesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2011;44:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Moriyama Y, Hasegawa T, Endo TA, Toyoda T, Gotoh Y. Scratch regulates neuronal migration onset via an epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like mechanism. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:416–425. doi: 10.1038/nn.3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwano T, Masuda A, Kiyonari H, Enomoto H, Matsuzaki F. Prox1 postmitotically defines dentate gyrus cells by specifying granule cell identity over CA3 pyramidal cell fate in the hippocampus. Development. 2012;139:3051–3062. doi: 10.1242/dev.080002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MS, McFarland WL, Morgane PJ. The anatomy of the brain of the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). Rhinic lobe (Rhinencephalon): The archicortex. Brain Res. Bull. 1979;4(Suppl 1):1–108. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(79)90299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. The evolution of brains from early mammals to humans. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2013;4:33–45. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T, Shimojo H, Imayoshi I. Dynamic regulation of Notch signaling in neural progenitor cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn MC, Hough GE, ten Eyck GR, Bingman VP. Internal connectivity of the homing pigeon (Columba livia) hippocampal formation: an anterograde and retrograde tracer study. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;459:127–141. doi: 10.1002/cne.10601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslin J, Ganz J, Brand M. Proliferation, neurogenesis and regeneration in the non-mammalian vertebrate brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008;363:101–122. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi A, Ikawa T, Kasukawa T, Ueda HR, Kurimoto K, Saitou M, Matsuzaki F. Single-cell gene profiling defines differential progenitor subclasses in mammalian neurogenesis. Development. 2008;135:3113–3124. doi: 10.1242/dev.022616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G. New neurons for 'survival of the fittest'. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;13:727–736. doi: 10.1038/nrn3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegstein A, Noctor S, Martínez-Cerdeño V. Patterns of neural stem and progenitor cell division may underlie evolutionary cortical expansion. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:883–890. doi: 10.1038/nrn2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara A, Hirabayashi Y, Knoepfler PS, Taketo MM, Sakai J, Kodama T, Gotoh Y. Wnt signaling and its downstream target N-myc regulate basal progenitors in the developing neocortex. Development. 2010;137:1035–1044. doi: 10.1242/dev.046417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewitus E, Kelava I, Kalinka AT, Tomancak P, Huttner WB. An adaptive threshold in mammalian neocortical evolution. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1002000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Pleasure SJ. Genetic regulation of dentate gyrus morphogenesis. Prog. Brain Res. 2007;163:143–152. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Kataoka H, Coughlin SR, Pleasure SJ. Identification of a transient subpial neurogenic zone in the developing dentate gyrus and its regulation by Cxcl12 and reelin signaling. Development. 2009;136:327–335. doi: 10.1242/dev.025742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Fang L, Fernández G, Pleasure SJ. The ventral hippocampus is the embryonic origin for adult neural stem cells in the dentate gyrus. Neuron. 2013;78:658–672. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey BW, Tropepe V. A comparative framework for understanding the biological principles of adult neurogenesis. Prog. Neurobiol. 2006;80:281–307. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Pleasure SJ, Collins AE, Noebels JL, Naya FJ, Tsai MJ, Lowenstein DH. Loss of BETA2/NeuroD leads to malformation of the dentate gyrus and epilepsy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:865–870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Garcia C, Molowny A, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Ferrer I. Delayed postnatal neurogenesis in the cerebral cortex of lizards. Brain Res. 1988;471:167–174. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Garcia C, Molowny A, Nacher J, Ponsoda X, Sancho-Bielsa F, Alonso-Llosa G. The lizard cerebral cortex as a model to study neuronal regeneration. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2002;74:85–104. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652002000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui JH, Hansen DV, Kriegstein AR. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell. 2011;146:18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis de la Iglesia JA, Martinez-Guijarro FI, Lopez-Garcia C. Neurons of the medial cortex outer plexiform layer of the lizard Podarcis hispanica: Golgi and immunocytochemical studies. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994;341:184–203. doi: 10.1002/cne.903410205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luisde la Iglesia JAL, Lopez-Garcia C. A Golgi study of the principal projection neurons of the medial cortex of the lizard Podarcis hispanica . J. Comp. Neurol. 1997a;385:528–564. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970908)385:4<528::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis de la Iglesia JAL, Lopez-Garcia C. A Golgi study of the short-axon interneurons of the cell layer and inner plexiform layer of the medial cortex of the lizard Podarcis hispanica . J. Comp. Neurol. 1997b;385:565–598. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970908)385:4<565::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma DK, Ming GL, Song H. Glial influences on neural stem cell development: cellular niches for adult neurogenesis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005;15:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangale VS, Hirokawa KE, Satyaki PR, Gokulchandran N, Chikbire S, Subramanian L, Shetty AS, Martynoga B, Paul J, Mai MV, Li Y, Flanagan LA, Tole S, Monuki ES. Lhx2 selector activity specifies cortical identity and suppresses hippocampal organizer fate. Science. 2008;319:304–309. doi: 10.1126/science.1151695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchioro M, Nunes JM, Ramalho AM, Molowny A, Perez-Martinez E, Ponsoda X, Lopez-Garcia C. Postnatal neurogenesis in the medial cortex of the tropical lizard Tropidurus hispidus . Neuroscience. 2005;134:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LA, Tan SS, Goldowitz D. Clonal architecture of the mouse hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:3520–3530. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03520.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cerdeño V, Noctor SC, Kriegstein AR. The role of intermediate progenitor cells in the evolutionary expansion of the cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2006;16(Suppl. 1):i152–i161. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cerdeño V, Cunningham CL, Camacho J, Keiter JA, Ariza J, Lovern M, Noctor SC. Evolutionary origin of Tbr2-expressing precursor cells and the subventricular zone in the prenatal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cne.23879. (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cerdeño V, Noctor SC. Cajal, Retzius, and Cajal-Retzius cells. Front. Neuroanat. 2014;8:48. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina L, Abellán A. Development and evolution of the pallium. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009;20:698–711. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;28:223–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.051804.101459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár Z. Evolution of cerebral cortical development. Brain Behav. Evol. 2011;78:94–107. doi: 10.1159/000327325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molowny A, Nacher J, Lopez-Garcia C. Reactive neurogenesis during regeneration of the lesioned medial cerebral cortex of lizards. Neuroscience. 1995;68:823–836. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00201-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BR, Hodge RD, Bedogni F, Hevner RF. Dynamic interactions between intermediate neurogenic progenitors and radial glia in embryonic mouse neocortex: potential role in Dll1-Notch signaling. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:9122–9139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0791-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R. Mammals: Telencephalon. In: Nieuwenhuys R, ten Donkelaar HJ, Nicholson C, editors. The Central Nervous System of Vertebrates, Vol. 3: Chapter 22. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1998. pp. 1871–2023. [Google Scholar]