SUMMARY

Histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) is known to correlate with both active and poised genomic loci, yet many questions remain regarding its functional roles in vivo. We identify functional genomic targets of two H3K4 methyltransferases, Set1 and MLL1/2, in both the stem cells and differentiated tissue of the planarian flatworm Schmidtea mediterranea. We show that, despite their common substrate, these enzymes target distinct genomic loci in vivo, which are distinguishable by the pattern each enzyme leaves on the chromatin template, i.e., the breadth of the H3K4me3 peak. Whereas Set1 targets are largely associated with the maintenance of the stem cell population, MLL1/2 targets are specifically enriched for genes involved in ciliogenesis. These data not only confirm that chromatin regulation is fundamental to planarian stem cell function, but also provide evidence for post-embryonic functional specificity of H3K4me3 methyltransferases in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Genomic DNA is precisely intertwined with histone proteins to form a chromatin template that functions as both a packaging structure and a gatekeeper of genetic information. These functions are in part regulated by post-translational modifications that are enzymatically added to histone proteins. Such modifications can serve as a record of past genetic activity and also predispose genomic regions to a particular functional activity, such as active transcription. Trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) is an example of a chromatin modification with a well-established relationship to genomic function. Originally identified in the active macronucleus of the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila (Strahl et al., 1999), H3K4me3 has been shown to correlate with active transcription in many multicellular organisms and biological contexts (Eissenberg and Shilatifard, 2010; Ruthenburg et al., 2007).

Two of the major enzymes responsible for H3K4me3 are Set1 and MLL1. Despite their common substrate and core subunits, loss of individual lysine methyltransferases (KMTases) often produces different phenotypes within an organism. For example, embryonic mutations in the Drosophila homolog of MLL1 (i.e. Trithorax, Trx) produce characteristic homeotic patterning defects (Ingham and Whittle, 1980; Kuzin et al., 1994) whereas embryonic deletion of Drosophila Set1 results in lethality (Hallson et al., 2012). Individual mutation of the mammalian counterparts of these enzymes, MLL1 and Setd1a, also results in distinctive phenotypes (Bledau et al., 2014; Terranova et al., 2006; Yu et al., 1998). Moreover, deletion of additional mammalian-specific H3K4 KMTases (mll2 and setd1b) lead to independent phenotypes, indicating that the function of specific enzymes is non-redundant (Bledau et al., 2014; Glaser, 2006).

Despite the evidence for their non-redundant biological roles, there is a surprising lack of clarity about the totality and nature of specific genomic loci targeted by Set1 and MLL in vivo. Several studies have focused on specific enzymes and/or subunits but often find an inconsistent relationship between loss of H3K4me3 and loss of gene expression (Clouaire et al., 2012; Greer et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2009; Tanny et al., 2007). Although studies in mll2-/- mouse embryonic stem cells have identified >2500 functional genomic targets (Denissov et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2013), the practicality of functionally validating these in an organismal context is daunting. However, organismal studies are necessary to understand fully the in vivo functional roles of H3K4me3.

We sought to resolve some of these outstanding issues by studying the targets of conserved H3K4 KMTases in the understudied Lophotrochozoa/Spiralia super clade, a sister group to the Ecdysozoans (e.g., Drosophila and C. elegans) and the Deuterostomes (e.g., vertebrates). Here we identify functional in vivo genomic targets of Set1 and MLL1/2 in a member of this group, the planarian species S. mediterranea. Although this organism is well established as a model for studying regeneration and stem cell biology (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Reddien et al., 2005; Wagner et al., 2012), its use in biochemical studies is relatively unexplored. We used chromatin-immunoprecipitation followed by DNA-sequencing (ChIP-seq) for the first time in this animal and show that Set1 and MLL1/2 target markedly different genomic loci in vivo. These loci are not only distinct from each other but also distinguishable by the breadth of their H3K4me3 peaks. Moreover, the target genes we identify also show clear functional and biological relevance to the RNAi phenotypes observed for each enzyme. Our findings not only inform the specific functions of H3K4 KMTases in multicellular organisms, but also establish planarians as a unique experimental system in which to study chromatin-based mechanisms of developmental regulation in an adult organism.

RESULTS

Planarians exhibit morphologically distinct phenotypes upon RNAi-knockdown of set1 versus mll1/2

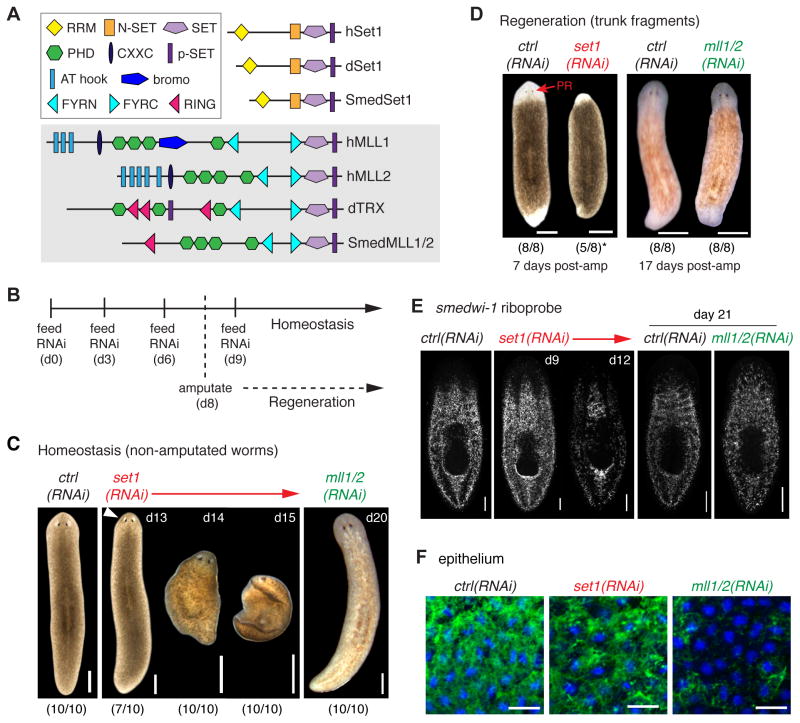

We first identified genes encoding histone H3K4 methyltransferases in the genome of S. mediterranea using reciprocal BLAST searches. In keeping with the conservation of Set1 from yeast to man (Eissenberg and Shilatifard, 2010), the domain structure of planarian Set1 (SmedSet1) is highly conserved (Figure 1A). Planarian MLL1/2 (SmedMLL1/2) also shares key domains and features with both mammalian MLL1 and MLL2 and Drosophila Trithorax. Although there are additional H3K4 methyltransferases in the planarian genome (Hubert et al., 2013), here we focus on Set1 and MLL1/2 since RNAi knockdown of their genes resulted in fully penetrant and morphologically distinct phenotypes, providing a clear basis to test the hypothesis that the different in vivo functionality of these KMTases is linked to their specific genomic targets.

Figure 1. Planarian Set1 and MLL1/2 are highly conserved proteins with distinct RNAi-knockdown phenotypes.

A) Schematic of the domain structure of the planarian proteins Set1 (SmedSet1) and MLL1/2 (SmedMLL1/2) in comparison to those of Drosophila (dSet1, dTrx) and human (hSet1 hMLL1/2). B) Timeline detailing the RNAi feeding schedule used in all experiments, unless stated otherwise. C) Live images of non-amputated control(RNAi), set1(RNAi) and mll1/2(RNAi) worms and D) those at 7 days (left) and 17 days (right) post-amputation. Scoring of morphological phenotype is for a single representative experiment. *indicates 3/8 fragments lysed before RD7. White arrowhead indicates early head regression. PR = photoreceptors. E) in situ hybridization for the smedwi-1 stem cell marker in both set1(RNAi) and mll1/2(RNAi) non-amputated worms. F) Confocal projections of the ciliated epithelium; cilia are labeled with antibody to acetylated-tubulin (green); nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars in C–D = 500μm, E = 200μm, F = 20μm. See also Movies S1–S2.

We then constructed RNAi vectors for planarian set1 and mll1/2 (Figure S1A, S1C) and a non-planarian control gene (unc-22)(Reddien et al., 2005), fed animals regularly with dsRNA generated from each construct (Figure 1B), and scored animals for phenotype with and without amputation. As previously described (Hubert et al., 2013) and shown here (Figure 1C and Movies S1, S2), worms dosed regularly with RNAi to set1 or mll1/2 show distinct homeostasis phenotypes in comparison to both each other and control(RNAi) worms; set1(RNAi) worms develop head regression, ventral curling and lysis within 2.5 weeks of first RNAi exposure, whereas mll1/2(RNAi) worms develop a progressive motility defect in which they gradually lose their normal gliding motion and revert to “inch-worming” when induced to move. Set1(RNAi) and mll1/2(RNAi) worms also respond differently to amputation; set1(RNAi) fragments fail to regenerate significant blastema tissue or photoreceptors (PRs) and lyse within 10 days. In contrast, mll1/2(RNAi) fragments regenerate a blastema of comparable size to that of control worms and form new photoreceptors (Figure 1D). However, regenerating mll1/2(RNAi) worms do exhibit significant developmental defects, including abnormally small pharyngeal cavities in the regenerated gut tissue (Figure S1D).

Since the morphology of the set1(RNAi) phenotype is highly similar to previously described stem cell deficiency phenotypes (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Wagner et al., 2012), we next assessed the status of the stem cell population in set1(RNAi), mll1/2(RNAi) and control(RNAi) worms by in situ hybridization with the smedwi-1 stem cell marker (Figure 1E). Predictably, set1(RNAi) worms showed significant loss of smedwi-1+ cells around the time of phenotype onset (day 15), although they did not show gross loss of stem cells in the first ≤10 days post-RNAi. In comparison, mll1/2(RNAi) worms did not show significant loss of smedwi-1+ stem cells (assessed at day 21, when motility defect is severe). On the other hand, when we labeled the cilia of all RNAi animals, mll1/2(RNAi) worms displayed a striking loss of cilia on their ventral surface whereas the cilia of set1(RNAi) worms were comparable to that of control animals (Figure 1F). We also confirmed the epithelial cilia defect in mll1/2(RNAi) worms by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Figure S1E). Interestingly, we did not see major defects in the ciliated flame cells of the planarian excretory system (Thi-Kim Vu et al., 2015) or obvious edema in mll1/2(RNAi) worms (Figure S1F–G), even though these phenotypes often correlate with motility defects (Rink et al., 2009). Together, these data show that loss of set1 leads to a distinctly different phenotype than that of mll1/2 during both homeostasis and regeneration in planarians.

H3K4me3-ChIP from whole worms identifies functional genomic targets of Set1 and MLL1/2

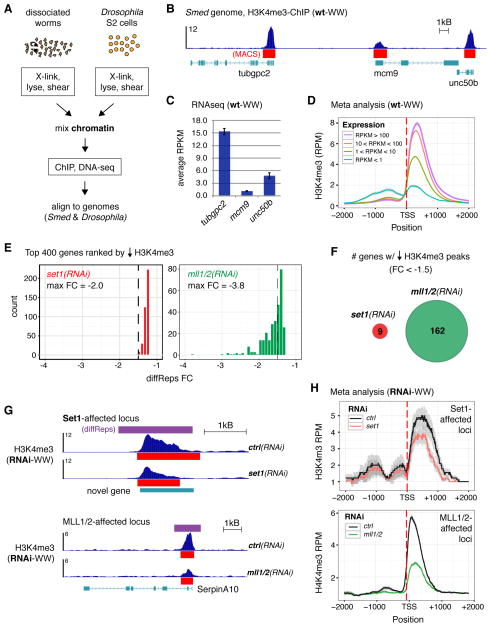

To identify the functional genomic targets of Set1 and MLL1/2 in planarians, we developed a chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq) protocol starting from dissociated whole worms (Figure 2A). Since genome-wide ChIP-seq has not been reported previously in planarians, we used Drosophila S2 cell chromatin as an internal spike-in control (Figure S2A and S2B). After validating ChIP experiments by qPCR at test Drosophila loci (Kharchenko et al., 2011), we sequenced the immunoprecipitated DNA and mapped the resulting reads to the Drosophila and S. mediterranea genomes (dos Santos et al., 2015; Robb et al., 2015; Robb et al., 2008).

Figure 2. H3K4me3 correlates with transcription in planarian whole worm tissue and is reduced at distinct loci upon RNAi of set1 versus mll1/2.

A) Schematic of ChIP-seq from dissociated whole worm tissue; Drosophila S2 chromatin was 25% of total/ChIP. B) Representative track of H3K4me3-ChIP DNA reads from wild-type whole worm tissue (wt-WW) aligned to the Schmidtea mediterranea genome. Red bars indicate MACS2-called peaks. C) RNAseq data from wt-WW for genes shown in B. Error bars indicate standard deviation across four biological replicates. D) Meta analysis of H3K4me3-ChIP data from wt-WW at all genes in the Schmidtea mediterranea genome with a MACS2-called peak; genes were binned according to the expression values indicated. E) Histograms showing the distributions of the top 400 genes associated with H3K4me3 peak reductions in whole worms after set1(RNAi) (left) or mll1/2(RNAi) (right), each compared to control(RNAi); dashed line indicates −1.5 fold-change (FC). F) Venn diagram of genes associated with < −1.5 FC reductions in H3K4me3 upon set1(RNAi) (red circle) and mll1/2(RNAi) (green circle) in whole worms tissue. G) Representative tracks of H3K4me3-ChIP from RNAi-WW at gene loci with comparable H3K4me3 reductions (−2.0 FC). H) Meta analyses of H3K4me3 signal from set1(RNAi) or mll1/2(RNAi) WW-ChIP at Set1-affected loci (top plot) and MLL1/2-affected loci (bottom plot). Gray indicates standard error in meta analyses (D, H). ChIP signal scale units are reads-per million (B, G).

Predictably, analysis of H3K4me3 ChIP-seq from wild-type whole worms (wt-WW) showed an enrichment of this modification at the 5′ end of many genes (Figure 2B). Moreover, the majority of H3K4me3 peaks are within 200bp of a gene TSS (Figure S2C). We then asked whether this modification is conserved in its correlation with transcription (Barski et al., 2007). As shown in Figure 2B–D, this relationship is indeed conserved; both individual gene (Figure 2B, 2C) and genome-wide (Figure 2D) analyses showed a positive correlation between RNAseq expression and the average maximum H3K4me3 enrichment. Together these data demonstrate that both the hallmark of H3K4me3 at gene TSSs and its correlation with transcription is conserved in planarians.

We then used this WW-ChIP approach to identify genomic loci at which H3K4me3 is lost in set1(RNAi) and mll1/2(RNAi) animals. After processing RNAi-treated worms for ChIP-seq as described above, we compared the aligned DNA reads from control(RNAi) worms with those from set1(RNAi) or mll1/2(RNAi) whole-worm (WW) samples using diffReps, a program designed to detect differential chromatin modification sites from ChIP-seq data (Shen et al., 2013). Differential H3K4me3 windows reported by diffReps were mapped to genes and then filtered to include those with a MACS2-called peak within 500bp of its TSS. Surprisingly, since Set1 is responsible for the majority of H3K4me3 signal in planarians (Figure S2D) and other organisms (Bledau et al., 2014; Hallson et al., 2012; Mohan et al., 2011), we detected very few loci with robust differential H3K4me3 changes (i.e. < −1.5 fold change, FC) in set1(RNAi) worms (Figure 2E and Table S1). In contrast, we identified >150 robust differential gene loci in mll1/2(RNAi) worms. Notably, we found no overlap between the genes near set1(RNAi) affected H3K4me3 peaks and those affected by mll1/2(RNAi) in whole worm H3K4me3-ChIP (Figure 2F), suggesting that Set1 and MLL1/2 operate at distinct loci in planarians. Although we acknowledge the small sample size of the set1(RNAi) results using a −1.5FC cutoff, this disunion also exists at a −1.3FC cutoff (at which there are 115 Set1-WW targets and 342 MLL1/2-WW targets).

We then analyzed the differential peaks more closely by visualizing the ChIP-DNA enrichment at individual loci (Figure 2G) and by meta analysis of all set1(RNAi) or mll1/2(RNAi) affected loci (Figure 2H). These analyses suggest that loss of Set1 reduced the width of the signal distribution more significantly than the height, while loss of MLL1/2 reduced the overall signal. However, as evident by the broad standard error (gray) in the Set1-affected gene meta gene plot (Figure 2H, top panel), the small number of Set1 targets affects the significance of this analysis. We hypothesized that performing ChIP-seq across all cell types of dissociated worms dampened the loss of H3K4me3 in any particular cell population. Because the set1(RNAi) phenotype indicates a defect and/or deficiency in the stem cell population, we next focused on the function and genomic targets of Set1 and MLL1/2 in these cells.

Stem cells exhibit distinct functional responses to RNAi of set1 versus mll1/2

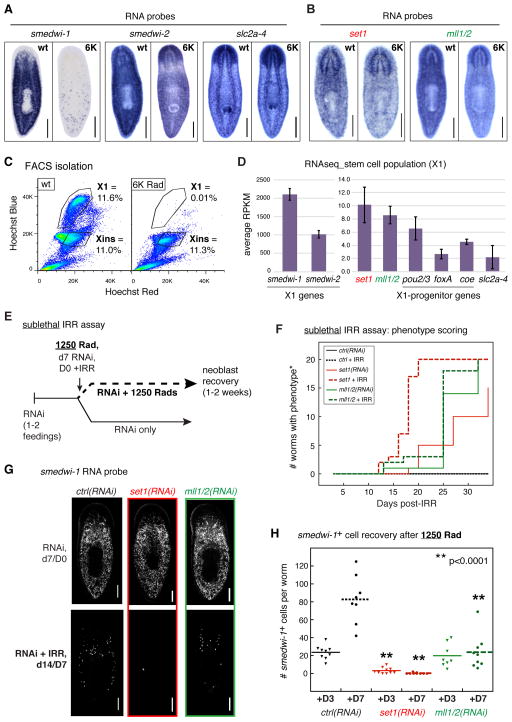

To address the possibility that the differences between set1(RNAi) and mll1/2(RNAi) worms are due to their differential expression, we performed in situ hybridization with probes to these genes. Since stem cells are eliminated after 24 hours of lethal (>6K Rads) ionizing radiation (Eisenhoffer et al., 2008; Wagner et al., 2012), loss of in situ signal in irradiated worms indicates gene expression in those cells. As shown in Figure 3A, the in situ pattern of the smedwi-1 stem cell marker (left) is completely abolished in 6K Rad irradiated worms, whereas a stem cell enriched gene (smedwi-2, middle) showed signal loss in areas of stem cell enrichment (e.g. tail stripe) but maintained signal in differentiated tissues (e.g., CNS, epithelium) in 6K worms. In contrast, a probe to the solute carrier gene slc2a-4 (right) showed strong expression in differentiated tissue (e.g., CNS, protonephridia) that was not affected by 6K Rad. When we examined the in situ patterns of set1 and mll1/2, we found that both genes were broadly expressed in many cell types/tissues and both showed moderate loss of signal upon stem cell ablation with 6K Rad (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. set1 and mll1/2 show comparable expression levels and patterns yet measurably different function in stem cells.

in situ hybridization in both wild-type (wt) untreated and 6K Rad irradiated (6K) worms with RNA probes to A) control genes (smedwi-1, stem cell marker; smedwi-2, stem cell enriched gene; slc2a-4, marker of differentiated tissue) and B) set1 and mll1/2. C) FACS scatter plots of dissociated cells from wt and 6K Rad worms after Hoechst Blue staining. The “X1” stem cell population disappears upon 6K Rad (right plot), while cells in the “Xins” population do not. D) Average RNAseq expression levels (RPKM) for representative stem cell marker and progenitor genes in the X1 stem cell population. E) Schematic of the modified sublethal irradiation assay used to measure stem cell population response to 1,250 Rads after RNAi. F) Phenotype scoring curves for sublethal assay; *indicates that set1(RNAi) and mll1/2(RNAi) phenotypes scored are distinct and those described in Figure 1; see also Figure S3. G) Representative images of in situ hybridization with smedwi-1 probe in worms 7 days post-RNAi but prior to radiation treatment (d7/D0) and at Day 7 post 1,250 Rads (14 days post-RNAi; d14/D7). H) Quantitation of smedwi-1+ cells in all worms labeled as in G; ** indicates significant difference (p <0.0001) from control(RNAi) at same time point. Scale bars in A, B, G = 200μm.

Recent studies have elegantly demonstrated that subsets of genes marking differentiated tissue may also have important roles in regulating stem cell function (Adler et al., 2014; Cowles et al., 2013; Lapan and Reddien, 2012; Scimone et al., 2011). To compare the expression levels of set1 and mll1/2 in the stem cell population with these genes, we isolated cycling planarian stem cells by flow cytometry (“X1” gated cells, Figure 3C)(Kang and Alvarado, 2009) and performed RNAseq to establish their transcriptional profile. As shown in Figure 3D, the relative RPKM levels of smedwi-1, smedwi-2, and slc2a-4 were as predicted by their in situ patterns, with smedwi-1 showing the highest relative expression and slc2a-4 the lowest. Both set1 and mll1/2 showed modest but robust levels of expression in the X1 stem cell population, on par with other genes (i.e., pou2/3, foxA, coe) that have important stem cell functions in addition to their expression in other cell types. We note, however, that RPKM levels may not accurately reflect protein or activity levels, particularly for enzymes.

Since expression level is not exclusively a determinant of gene function, we also asked how loss of set1 and mll1/2 affects stem cell function. We modified a previously established assay (Wagner et al., 2012) in which stem cells are subjected to a challenge of sub-lethal ionizing radiation (1,250 Rads) and then allowed to recover (Figure 3E). We hypothesized that if set1 and/or mll1/2 were required for proper stem cell function and if loss of that function contributes to their RNAi phenotype, then challenging stem cells with sub-lethal irradiation should hasten its appearance (i.e., head regression etc. in set1(RNAi) animals and motility defects in mll1/2(RNAi) worms). Indeed, after a single exposure to RNAi, set1(RNAi) + IRR (1250 Rad) worms exhibited head regression > 9 days prior to set1(RNAi)-only worms (Figure 3F, dashed red line versus solid red line; based on when 50% of assayed worms showed phenotype). In contrast, mll1/2(RNAi) worms showed no appreciable difference in the appearance of their phenotype with and without radiation (Figure 3F, dashed green line versus solid green line). Notably, mll1/2(RNAi) + IRR worms also did not develop head regression or other characteristic signs of neoblast deficiency even after > 4 weeks of observation (Figure S3).

In order to assess the stem cell response directly, we then quantitated the number of smedwi1+ stem cells in worms at days 3 and 7 post 1250 Rads radiation (+D3 and +D7). Importantly, worms from all three RNAi conditions show comparable smedwi-1 staining patterns prior to sub-lethal radiation (Figure 3G, d7/D0). As expected, control(RNAi) + IRR worms showed a dramatic loss of smedwi1+ stem cells at +D3 and significant recovery by +D7 (Figure 3G-H). In contrast, set1(RNAi) worms showed a greater decrease of smedwi-1+ cells than control(RNAi) at +D3 and no recovery at +D7 (Figure 3H, red dots), suggesting that set1(RNAi) stem cells are more sensitive to radiation. Interestingly, the number of smedwi-1+ cells in mll1/2(RNAi) worms was comparable to control at +D3 but diminished at +D7 (Figure 3H, green dots). The latter result is surprising, given that mll1/2(RNAi) + IRR worms did not show signs of stem cell deficiency (i.e., lesions/head regression) through +D32. These results indicate that loss of MLL1/2 not only leads to a very different morphological phenotype than that of Set1, but also affects the stem cell population in a measurably distinct way.

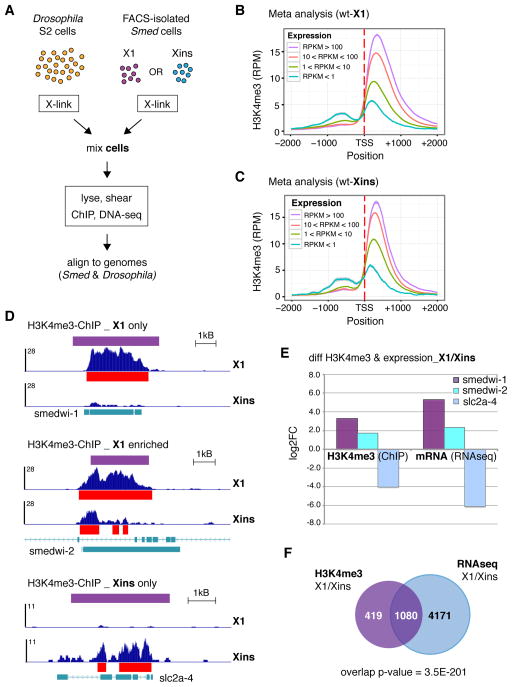

ChIP-seq from isolated cell populations confirms a strong and biologically meaningful correlation between H3K4me3 and transcription

After observing that set1(RNAi) and mll1/2(RNAi) each led to impaired stem cell function, we then sought to establish a ChIP-seq protocol starting from isolated planarian stem cells. Again, we chose to use Drosophila S2 cells as a positive internal ChIP control (Figure 4A). Here we use Drosophila S2 cells as a “carrier” in which they are in excess of the cells of interest (i.e., FACS-isolated planarian cells) and provide the molecular mass needed for ChIP (i.e. < 106 planarian cells mixed with 107 S2 cells). We validated this method by comparing H3K4me3-ChIP from FACS-isolated stem cells (“X1” gated cells, see above) with that from a mixed differentiated cell population isolated in parallel (“Xins” cells, Figure 3C) and correlating the differences with RNAseq data from both cell populations.

Figure 4. Differences in H3K4me3 correlate significantly with differences in the transcriptional profiles of stem cell and differentiated cell populations.

A) Schematic of ChIP-seq starting from FACS-isolated Smed cell populations; Drosophila S2 cells were >90% cells/ChIP. B) Meta analyses of H3K4me3-ChIP data from wild-type X1 stem cells (wt-X1) and C) Xins differentiated cells (wt-Xins) at all genes in the Schmidtea mediterranea genome with a MACS2-called peak in either population; genes are binned according to the expression values indicated. Standard error is in gray. D) Representative tracks of H3K4me3-ChIP from wt-X1 and wt-Xins cells at gene loci with the indicated categories of H3K4me3 enrichment. Red bars indicate MACS2-called peaks, purple bars indicated diffReps-called differential windows. ChIP signal scale units are reads-per million. E) Comparison of differential H3K4me3 and differential transcript expression at the gene loci in D. F) Venn diagram of all gene loci with enriched H3K4me3 (purple circle) and expression (blue circle) in X1 stem cells compared to Xins differentiated cells (pAdj < 0.01). The overlap (1080) is significantly greater than the number expected by chance (317), p = 3.5E-201 (hypergeometric test).

Importantly, H3K4me3-ChIP from both cell types showed the expected correlation with gene expression (Figure 4B–C) as seen in whole worms (Figure 2). We then used diffReps to identify differences in H3K4me3 enrichment between the two cell populations (Table S2). Notably, we detected significant differences in H3K4me3 enrichment at several control genes (Figure 4D–E). Moreover, diffReps reported both regions and degrees of fold change in H3K4me3 that correlated well with visible differences in ChIP-DNA enrichment and MACS2-called peaks at these control loci. For example, the smedwi-1 and slc2a-4 gene loci each showed H3K4me3 enrichment and MACS2-called peaks in a single cell type, whereas the smedwi-2 gene locus showed broader H3K4me3 enrichment and a wider MACS2-called peak in X1 cell ChIP (Figure 4D). Fittingly, diffReps called wide windows of differential H3K4me3 at the smedwi-1 and slc2a-4 loci and a narrower, 3′-shifted differential window at the smedwi-2 locus. The fold-change reported by diffReps also correlated well with the expression changes at these loci as measured by RNAseq (Figure 4E). Furthermore, when we compared all gene loci at which diffReps analysis identified significant H3K4me3 enrichment in X1 cells with all genes showing significantly increased expression in X1 cells, the correlation was highly significant (p = 3.5E-201, Figure 4F). There was also a significant correlation between gene loci with the opposite enrichment (genes with increased H3K4me3 and gene expression in Xins cells, Figure S4A). In contrast, there was no significant correlation between genes enriched for H3K4me3 in X1 cells and those with increased expression in Xins cells (Figure S4B) or the reverse (Figure S4C).

H3K4me3-ChIP from isolated stem cells identifies distinct classes of Set1 and MLL1/2-affected gene loci

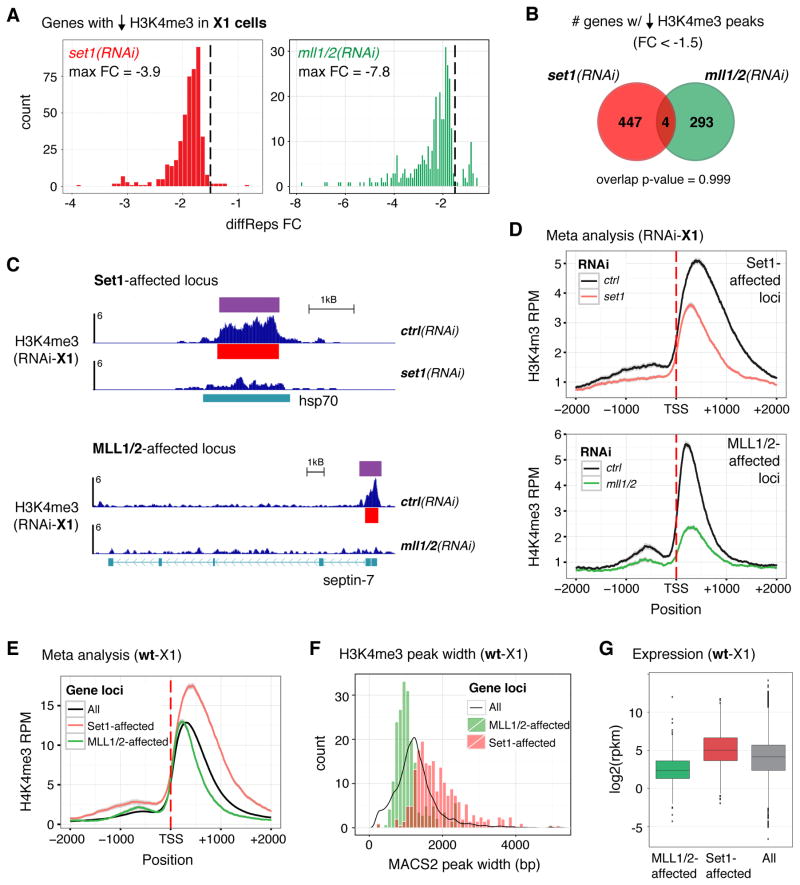

We then used the above approach to identify gene loci at which H3K4me3 was significantly reduced in X1 stem cells isolated from set1(RNAi) and mll1/2(RNAi) animals (each compared to control(RNAi) stem cells). As shown in Figure 5A (and Table S3), H3K4me3 ChIP-seq from set1(RNAi) stem cells revealed many more robust changes than seen in whole worms (Figure 2E). We also observed many robust changes in H3K4me3 enrichment on the stem cell genome after mll1/2(RNAi); as in the whole worm ChIP-seq results, these changes showed a broader distribution and greater maximum fold change than those seen in set1(RNAi) stem cells. Still, we found that there was no significant overlap between Set1 and MLL1/2-affected loci (Figure 5B). In fact, the number of overlapping genes (n=4) is significantly less than that expected by chance (n=15), indicating that these two enzymes target distinct genomic loci.

Figure 5. RNAi of set1 and mll1/2 each affect H3K4me3 in stem cells and at distinct gene loci.

A) Histograms showing the distributions of all H3K4me3 reductions in X1 stem cells after set1(RNAi) (left) or mll1/2(RNAi) (right), each in comparison to control(RNAi); dashed line indicates −1.5 fold-change (FC). B) Venn diagram of genes with differential H3K4me3 peaks (<−1.5FC) in X1 stem cells upon set1(RNAi) (red circle) and mll1/2(RNAi) (green circle). Similarity between these gene loci is not significant (p = 0.999, hypergeometric test). C) Representative tracks of H3K4me3-ChIP from RNAi X1 stem cells (RNAi-X1) at gene loci affected by set1(RNAi) (top) and mll1/2(RNAi) (bottom). Red bars indicate MACS2-called peaks, purple bars indicated diffReps-called differential windows. ChIP signal scale units are reads-per million. D) Meta analyses of H3K4me3-ChIP from RNAi-X1 stem cells at loci affected by set1(RNAi) (Set1-affected, top plot) and mll1/2(RNAi) (MLL1/2-affected, bottom plot). Standard error is in gray. E) Meta analysis of H3K4me3 signal in wt-X1 cells at Set1-affected loci (red line) and MLL1/2-affected loci (green line) in comparison to all gene loci with a MACS2-called peak (black line). F) Histogram of MACS2-called H3K4me3 peak widths (bp) in wt-X1 cells at gene loci affected by each RNAi condition; the populations are significantly different (p < 2 E-16, Wilcox test). A density plot averaging “all” wt-X1 H3K4me3-ChIP peak widths is shown for comparison (black line). G) Box plot of average wt-X1 expression (RNAseq) for “all” genes (All) compared with those at Set1-affected loci (red) or MLL1/2-affected loci (green). Separate comparisons between “All” and RNAi conditions each show a significant difference, p < 2 E-16.

We then examined the H3K4me3 enrichment patterns at Set1 and MLL1/2-affected genes more closely. We found that the average Set1-affected locus showed a broader distribution of H3K4me3 than that seen at MLL1/2-affected genes (compare control signal, Figure 5C-D). As suggested in the whole worm ChIP-seq data, we also observed that Set1-affected peaks lost significant H3K4me3 signal from both the summit and 3′ shoulder upon set(RNAi) whereas MLL1/2-affected peaks showed more uniform loss of H3K4me3 signal upon mll1/2(RNAi) (Figure 5D). To verify these differences, we then analyzed their patterns using an independently generated H3K4me3-ChIP-seq dataset from wild-type stem cells (Figure 5E). Again, we saw that Set1-affected gene loci were marked with broader distributions of H3K4me3 signal than those affected by MLL1/2. Interestingly, we also found that H3K4me3 signal at Set1-affected genes was not only wider but also higher than H3K4me3 signal at the average locus (i.e. average H3K4me3 signal at “all” loci with MACS2-called peaks within 500bp of TSSs, n=8820). In contrast, H3K4me3 enrichment at MLL1/2-affected genes was narrower than both Set1-affected genes and the average locus but its height was comparable to average.

Another way to measure differences in H3K4me3 peak width is by comparing MACS2-called peaks. As shown in the histogram of MACS2-called peak widths at Set1 and MLL1/2-affected loci (Figure 5F), we found that they fall into two significantly distinct populations (p-value = < 2E-16). Moreover, when we add a density plot averaging “all” MACS2-called H3K4me3 peaks in stem cells, we observed that Set1-affected loci have wider peak widths than average and MLL1/2-affected loci have narrower peaks widths (mean/median for Set1-affected genes = 1901/1747bp, for MLL1/2-affected genes = 1111/1000bp, for “all” = 1274/1212bp). Notably, the breadth of H3K4me3 is not significantly different in H3K4me3-ChIP from wt-WW for MLL1/2-affected genes identified in stem cells (Figure S5A) nor do those genes targeted by MLL1/2 in RNAi-WW differ in breadth to those targeted in stem cells (Figure S5B). These data support the observation that Set1 and MLL1/2-affected gene loci can be distinguished by their H3K4me3 peak width and that the meta gene analyses highlight differences between truly separate classes of loci.

We then asked if these two populations of loci also differed in gene expression. We found that Set1-affected genes showed significantly higher expression levels in wild-type stem cells than the average for all stem cell expressed genes (p-value = < 2E-16, Figure 5G). MLL1/2-affected genes, on the other hand, showed significantly lower expression in comparison to “all” genes (p-value = < 2E-16), despite their comparably tall average H3K4me3 peak. In addition, ChIP-seq for H3K36me3, another mark of active chromatin, shows enrichment at Set1-affected genes but significantly less signal at MLL1/2-affected genes (Figure S5F). In all, we conclude from these data that Set1 and MLL1/2 target distinct and distinguishable genomic loci in stem cells in vivo.

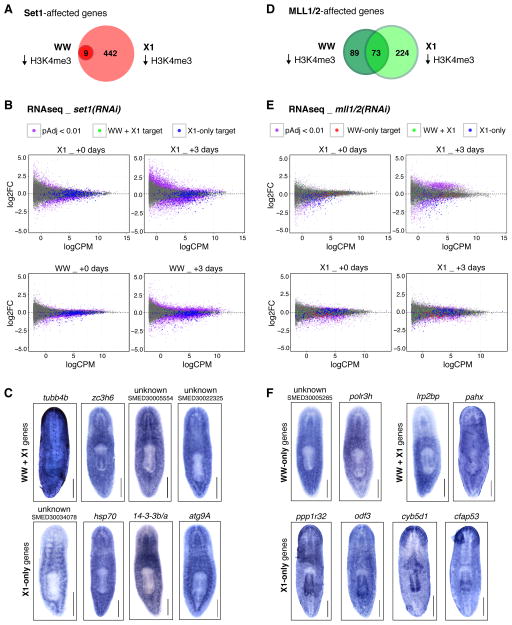

Both Set1- and MLL1/2-affected loci are functionally and biologically relevant

We then asked if the identified Set1 and MLL1/2-affected loci are functionally and biologically relevant to the individual phenotypes observed. Notably, all Set1-affected loci identified in whole-worm tissue were included in the list of stem cell targets (Figure 6A, Tables S1 and S3), suggesting that H3K4me3 at Set1 target genes is first established in the stem cell population. Additionally, genes identified as Set1 targets include many known stem cell markers, e.g. histone genes, smedwi-1 and soxP-2 (Sánchez Alvarado et al., 2002; Solana et al., 2012; Wagner et al., 2012). When we analyzed Set1 target genes for the enrichment of specific gene ontology (GO term), we found significant enrichment of many terms pertaining to transcription, RNA/DNA binding, and chromatin-modifying activities (Table S5), revealing that Set1 and its targets may operate in feedback loops to maintain open and active chromatin.

Figure 6. Gene loci affected by RNAi of set1 and mll1/2, respectively, are functionally and biologically relevant.

A) Venn diagram of gene loci affected by set1(RNAi) in whole worm tissue (WW, dark red circle) and X1 stem cells (X1, light red circle). B) MA plots of expression changes in set1(RNAi) WW tissue and X1 stem cells (each in comparison to control(RNAi)) at both the time point when H3K4me3-ChIP was performed (+0 days) and 3 days later (+3 days). Data points are highlighted according to their significance (pAdj < 0.01) and loss of H3K4me3 (in WW-ChIP, X1-ChIP, or both). C) Colorometric in situ hybridization with RNA probes to representative genes affected by set1(RNAi). D) Venn diagram of gene loci affected by mll1/2(RNAi) in WW (dark green circle) and X1 stem cells (light green circle). E) MA plots of expression changes in mll1/2(RNAi) WW and X1 stem cells at +0 and +3 days post-ChIP. Data points are highlighted as in B. F) Colorometric in situ hybridization with RNA probes to representative genes affected by mll1/2(RNAi). Scale bars in C, F = 200μm.

To assess transcriptional changes upon set1(RNAi) and their correlation with H3K4me3 loss, we next performed RNAseq on set1(RNAi) whole worms and stem cells. Knockdown of set1 leads to significant down-regulation of transcripts (Figure 6B and Table S4) at both the time point when H3K4me3-ChIP was performed (+0 days) and 3 days post-ChIP (+3 days) in both whole worm tissue (WW) and X1 stem cells (X1). Importantly, genes with loss of H3K4me3 and those with loss of expression overlapped significant for each RNAseq time point and cell/tissue type (Figure S6A, p-value ≤ 5.1e-12). Interestingly, this correlation was stronger when comparing genes with Set-dependent loss of H3K4me3 and genes down-regulated in WW-RNAi (Figure S6A), even though the overwhelming majority of Set1 targets were identified in stem cells. We also noted that the correlation between H3K4me3 loss and decreased transcription grew more significant at the later (+3 day) time point, a temporal relationship that held for both set1(RNAi) stem cells and whole worms.

We then used in situ hybridization to determine the expression patterns of representative Set1-affected genes (Figure 6C). As predicted by their high average expression, many Set1-affected genes showed qualitatively strong expression by in situ hybridization (e.g. tubb4b). Genes identified in whole worm H3K4me3-ChIP (first row, “WW + X1 genes”) showed expression in a broad range of tissues and/or ubiquitously. Unsurprisingly, some targets identified specifically in stem cells (second row, “X1-only genes”) had stem cell enrichment patterns similar to smedwi-1 and smedwi-2 (e.g. SMED30034078, hsp70 and 14-3-3b/a). However, many genes in the X1-only target list also exhibited expression in differentiated tissues (e.g. atg9A signal in CNS and gut tissue).

In contrast, mll1/2(RNAi) affects H3K4me3 at unique gene loci in both whole worm tissue and X1 stem cells (Figure 6D). Interestingly, when we examined the top 10% of WW-only target loci in H3K4me3-ChIP from stem cells, we found they all had robust H3K4me3 peaks but with non-significant and/or non-consistent reduction in H3K4me3 (i.e. below the diffReps threshold) upon mll1/2(RNAi). This suggests that other HMTases may be operating at these loci in stem cells before ceding the role to MLL1/2 in differentiated tissues. RNAseq analysis revealed that MLL1/2 target genes also showed the expected correlation between loss of H3K4me3 and decreased gene expression (Figure S6B and Figure 6E). Different from that in set1(RNAi) worms, we found that the relationship between loss of H3K4me3 and decreased expression was significantly more tissue/cell restricted upon mll1(RNAi). For example, targets identified in WW-only ChIP correlated significantly with decreased expression in WW-RNAi at the same time point (p-value = 3.9e-10), but did not correlate significantly with decreased gene expression in X1 stem cells at that time point (Figure S6B and Figure 6E, red versus blue data points). The MLL1/2 data did, however, show the same temporal correlation between H3K4me3 loss and decreased gene expression at the later RNAseq time point.

We then performed in situ hybridization on representative MLL1/2-affected genes (Figure 6F). Many target loci identified in WW-only ChIP showed broad expression throughout the worm but with a similar pattern between genes. Targets identified in both whole worm tissue and stem cells (“WW+X1”) showed patterns similar to those seen with WW-only gene probes but also included epithelial expressed genes (e.g., pahx). Intriguingly, the MLL1/2-affected genes that presented the most biologically relevant expression patterns were those identified exclusively in X1 stem cells (“X1-only”); > 60% (12/18) of genes screened from this list showed patterns of expression in ciliated tissues, including the outer epithelial layer, peripheral neurons, and pharynx. When we examined their annotations and known roles of their homologs, we found that many of these genes are involved in ciliogenesis (e.g., radial spoke head protein 6A, dynein heavy chain 5, intraflagellar transport protein 57). We then asked if this gene ontology was statistically significant; indeed, when we analyzed GO term enrichment across the entire list of genes affected by mll1/2(RNAi) in X1 stem cells, both the “cilium” and “cell projection” terms showed significant enrichment (BH corrected p-value = 8.6E-03; Table S5). As with the finding that many Set1-affected genes have known stem cell roles, these data strongly suggest that the identified MLL1/2 targets are both functionally and biologically relevant to mll1/2(RNAi)-induced pathologies.

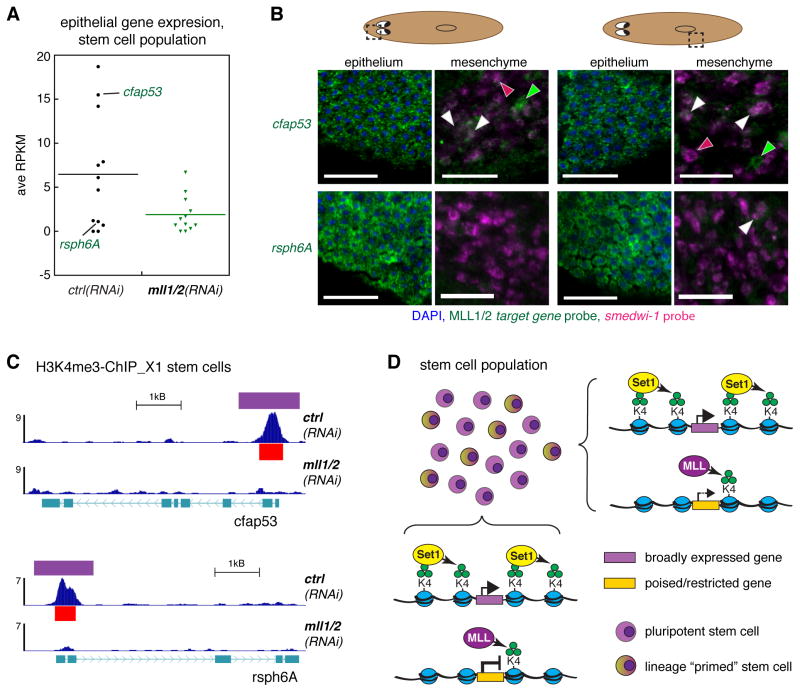

MLL1/2 methylation in stem cells marks specific genes for later activation

We were struck by the fact that many biologically relevant MLL1/2 target genes were identified specifically in H3K4me3-ChIP from stem cells. Importantly, previous work has shown that there is no evidence of cilia in planarian stem cells (Azimzadeh et al., 2012). When we plotted the average expression for the 12/18 assayed MLL1/2 target genes with epithelial expressed patterns, we found that their expression in the X1 stem cell population was generally low (Figure 7A). Those genes with RPKM levels > 5 in ctrl(RNAi) stem cells did show significant loss of expression upon mll1/2(RNAi). Since low expression levels could indicate either low overall expression or a small number of normally expressing cells within the sampled population, we then performed double in situ hybridization for individual target genes and the smedwi-1 stem cell marker (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. RNAi of mll1/2 affects transcriptionally poised gene loci in stem cells.

A) Dot plot of average RNAseq expression in the wt-X1 stem cell population for representative MLL1/2 target genes identified in stem cells. B) Confocal images of double fluorescent in situ hybridization with RNA probes to the indicated MLL1/2 target gene and smedwi-1 (MLL1/2 target genes in green, smedwi-1 in magenta, DAPI in blue); first and third column images are Z-projections of the epithelial layer at the head and pharynx regions of the worm, respectively. Second and fourth column images are single, deeper confocal slices from the same worm (where smedwi-1+ cells are detectable). Scale bars = 50μm. C) Representative tracks of H3K4me3-ChIP from RNAi-X1 cells at the gene loci described in B. Red bars indicate MACS2-called peaks, purple bars indicated diffReps-called differential windows. ChIP signal scale units are reads-per million. D) Model describing the different roles of Set1 and MLL1/2 in the stem cell population.

Consistent with the single in situ patterns described above (Figure 6F), we observed strong expression of representative MLL1/2 stem cell target genes (i.e. cfap53 and rhsp6A) in the epithelial layer (Figure 7B). When we looked at deeper confocal slices in which we observed strong smedwi-1+ stem cells (magenta), we did identify some cells that were potentially positive for cfap53 or rsph6A (overlapping signal in white and indicated by white arrowheads); however, their expression was much weaker in these double positive stem cells than in the cells of the epithelial layer or other (smedwi-1−) cell types in the mesenchyme (green arrows). Nevertheless, both cfap53 and rsph6A gene loci bear a robust H3K4me3 peak (Figure 7C) with ChIP signal that compares to that at gene loci with much greater expression in the stem cell population (Figure S5D). Together, these data suggest that MLL1/2 methylates specific, inactive gene loci in the stem cell population in order to poise them for activation later in development.

DISCUSSION

Set1 and MLL1/2 target distinct loci in a complex, multicellular organism

H3K4me3 and the enzymes that catalyze it are highly conserved throughout evolution and have well-documented roles in the regulation of the chromatin template. Specific loss of Set1 and MLL1/MLL2 has also been shown to cause H3K4me3 loss and non-redundant morphological phenotypes (Bledau et al., 2014; Greer et al., 2010; Hallson et al., 2012; Yan et al., 2014; Yu et al., 1998). Although there are many elegant studies detailing the regulation of Hox loci by Set1 and MLL1/MLL2, evidence linking additional enzyme-specific genomic targets to particular in vivo phenotypes has been lacking. Although studies have identified gene loci at which H3K4me3 is affected upon loss of MLL1 and MLL2 in mouse ESCs (Denissov et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2013), their in vivo specificity has not been determined. In contrast, our studies uncovering the Set1 and MLL1/2-affected genes in planarians were informed by a biology-driven question: can the distinct phenotypes observed upon knockdown of each enzyme be explained by their targeting of distinct genomic targets? By establishing a ChIP-seq protocol using isolated planarian stem cells, we answered this question affirmatively.

When we examined the loss of H3K4me3 caused by RNAi knockdown of set1, we found that planarian Set1 generally behaves as expected: H3K4me3 peaks are higher at its target genes than the “average” gene and these genes show correspondingly higher than average expression (Figure 5). Interestingly, loss of H3K4me3 was detected much more robustly in ChIP from set1(RNAi) stem cells even though Set1 target genes showed greater correlation to decreased gene expression in set1(RNAi) whole worms (Figure S6). MLL1/2 target genes also show a strong correlation between H3K4me3 and gene expression in planarians, yet MLL1/2 appears to exhibit much greater specificity and target gene regulation than Set1 in that it has unique targets in both stem cells and differentiated tissue. Moreover, MLL1/2 not only catalyzes H3K4me3 at different loci than Set1, but also targets loci with narrower than average H3K4me3 peak widths in a cell population where many loci have a tendency to be wider (i.e. meta gene analyses of H3K4me3-ChIP in X1 stem cells shows wider signal distribution than that seen in Xins differentiated cells; Figure 4B-C). The mechanisms through which such specificity is achieved are presently unknown but will be addressed in future experiments.

Chromatin organization plays a functional role in stem cell biology

One intriguing yet poorly understood role of H3K4me3 is in transcriptional poising, particularly at developmental gene loci (Azuara et al., 2006; Bernstein et al., 2006; Lindeman et al., 2011; Vastenhouw et al., 2010). To date, most studies examining this function have been done in cultured embryonic stem cell (ESCs). Although ESCs have many obvious advantages, it is non-trivial to identify and validate a true in vivo counterpart in which to test the biological relevance of such findings. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that exact culture conditions can dramatically impact the observed biology of these cell types (Dunn et al., 2014; Theunissen et al., 2014; Ying et al., 2008). Here we show that ChIP-seq in isolated planarian stem cells can identify biologically relevant targets with direct connections to organismal biology. Moreover, many of the biologically relevant MLL1/2 target genes were identified in ChIP from the stem cell population, in which they show little to no detectable expression, suggesting that MLL1/2 may be regulating their differentiation through an epigenetic poising mechanism.

Our work also offers insight into the stem cell biology of planarian neoblasts. Recent focus in the planarian field has been on the heterogeneity of these cells at the transcript level (Scimone et al., 2014; van Wolfswinkel et al., 2014). In several cases, there is evidence that specific “differentiated” tissue transcripts label stem cells that contribute directly to those tissues (Adler et al., 2014; Cowles et al., 2013; Lapan and Reddien, 2012; Scimone et al., 2011). However, in other cases it is still unclear if or how the presence of such transcripts affects the developmental fate of these cells. Here we present evidence that some tissue-restricted gene loci are decorated with robust H3K4me3 peaks in the stem cell population yet do not produce many transcripts in these cells. Additionally, we show that the distribution of H3K4me3 often changes at key stem cell loci upon differentiation. These data strongly suggest that the chromatin state at specific genomic loci plays a critical role in regulating the biology of planarian stem cells.

We propose a model (Figure 7D) in which Set1 and MLL1/2 act at specific target loci to influence cell identity and/or lineage potential. Although transcription clearly plays an important deterministic role in the fate-choice of these cell, we propose a probabilistic model in which the chromatin state establishes the fundamental expression potential of a given locus that can then be further activated (or silenced) by other factors. This model posits that chromatin state contributes to lineage choices in ways that do not necessarily correlate with active transcription (i.e. at poised genes). This model raises many questions, particularly in regard to the molecules and mechanisms involved in achieving and maintaining such distinguishable H3K4me3 patterns and regulation. By taking advantage of the developmental plasticity of planarians and our ability to distinguish chromatin modification events between undifferentiated and differentiated cells within them, we aim to address these questions and others in future studies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chromatin-immunoprecipitation plus DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Chromatin-immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described (Lee et al., 2006) with some modifications. Briefly, whole worms were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, minced, cross-linked in 4% PFA for 10 minutes (RT), quenched with glycine, filtered, pelleted, and washed twice with 0.4X PBS/10% FBS. FACS-isolated planarian cells and Drosophila S2 cells were cross-linked in suspension. Pellets were lysed, sheared in the S220 Focused Ultrasonicator (Covaris), cleared by centrifugation and used for immunoprecipitations. Antibodies to H3K4me3 (Millipore 07-473) or H3K36me3 (Abcam ab9050) were used added to chromatin overnight and then captured with ProteinA/G magnetic beads (Life Technologies). ChIPs were then washed, eluted, and incubated overnight at 65°C to reverse cross-links. After digestion with RNase and ProteinaseK, DNA was isolated by column purification (Qiagen) and used for either qPCR or DNAseq library preparation (Illumina TruSeq RNA kit). Further details can be found in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the ASA laboratory for discussion and advice, K. Gotting for assistance in analysis, A. Ruthenburg for input on ChIP experiments, and L.A. Banaszynski and C.D. Allis for valuable input on the manuscript. We also thank the Cytometry, Molecular Biology, Histology and Tissue Culture core facilities at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research. E.M. Duncan is a Damon Runyon HHMI fellow. ASA is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Stowers Institute for Medical Research investigator. This work was supported by NIH R37GM057260.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

All RNAseq and ChIPseq datasets can be referenced from SuperSeries GSE74169. Individual datasets have specific GEO accession numbers: RNAseq from wild-type X1 and Xins cells (GSE73027), RNAseq from RNAi worms/cells (GSE74153), all H3K4me3 ChIP-seq (GSE74054), H3K36me3 ChIP-seq from wild-type X1 cells (GSE74419).Original data underlying this manuscript can be accessed from the Stowers Original Data Repository at http://www.stowers.org/research/publications/libpb-1017.

Supplemental information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, six figures, and five tables and two movies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.M.D. designed most and performed most experimental work and wrote the manuscript; A.D.C. and C.W.S. performed all bioinformatics analyses and contributed extensively to discussions of results and interpretation of findings. A.S.A. advised and contributed to all experimental design, interpretation of results, and preparing of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler CE, Seidel CW, McKinney SA, Sánchez Alvarado A. Selective amputation of the pharynx identifies a FoxA-dependent regeneration program in planaria. Elife. 2014;3:e02238. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimzadeh J, Wong ML, Downhour DM, Sánchez Alvarado A, Marshall WF. Centrosome loss in the evolution of planarians. Science. 2012;335:461–463. doi: 10.1126/science.1214457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuara V, Perry P, Sauer S, Spivakov M, Jørgensen HF, John RM, Gouti M, Casanova M, Warnes G, Merkenschlager M, et al. Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:532–538. doi: 10.1038/ncb1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. High-Resolution Profiling of Histone Methylations in the Human Genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, et al. A Bivalent Chromatin Structure Marks Key Developmental Genes in Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledau AS, Schmidt K, Neumann K, Hill U, Ciotta G, Gupta A, Torres DC, Fu J, Kranz A, Stewart AF, et al. The H3K4 methyltransferase Setd1a is first required at the epiblast stage, whereas Setd1b becomes essential after gastrulation. Development. 2014;141:1022–1035. doi: 10.1242/dev.098152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouaire T, Webb S, Skene P, Illingworth R, Kerr A, Andrews R, Lee JH, Skalnik D, Bird A. Cfp1 integrates both CpG content and gene activity for accurate H3K4me3 deposition in embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1714–1728. doi: 10.1101/gad.194209.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles MW, Brown DD, Nisperos SV, Stanley BN, Pearson BJ, Zayas RM. Genome-wide analysis of the bHLH gene family in planarians identifies factors required for adult neurogenesis and neuronal regeneration. Development. 2013;140:4691–4702. doi: 10.1242/dev.098616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denissov S, Hofemeister H, Marks H, Kranz A, Ciotta G, Singh S, Anastassiadis K, Stunnenberg HG, Stewart AF. Mll2 is required for H3K4 trimethylation on bivalent promoters in embryonic stem cells, whereas Mll1 is redundant. Development. 2014;141:526–537. doi: 10.1242/dev.102681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos G, Schroeder AJ, Goodman JL, Strelets VB, Crosby MA, Thurmond J, Emmert DB, Gelbart WM, FlyBase C. FlyBase: introduction of the Drosophila melanogaster Release 6 reference genome assembly and large-scale migration of genome annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D690–697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn SJ, Martello G, Yordanov B, Emmott S, Smith AG. Defining an essential transcription factor program for naive pluripotency. Science. 2014;344:1156–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1248882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhoffer GT, Kang H, Sánchez Alvarado A. Molecular Analysis of Stem Cells and Their Descendants during Cell Turnover and Regeneration in the Planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg JC, Shilatifard A. Histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation in development and differentiation. Developmental Biology. 2010;339:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser S. Multiple epigenetic maintenance factors implicated by the loss of Mll2 in mouse development. Development. 2006;133:1423–1432. doi: 10.1242/dev.02302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Maures TJ, Hauswirth AG, Green EM, Leeman DS, Maro GS, Han S, Banko MR, Gozani O, Brunet A. Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans. Nature. 2010;466:383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature09195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Maures TJ, Ucar D, Hauswirth AG, Mancini E, Lim JP, Benayoun BA, Shi Y, Brunet A. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2011:1–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallson G, Hollebakken RE, Li T, Syrzycka M, Kim I, Cotsworth S, Fitzpatrick KA, Sinclair DAR, Honda BM. dSet1 Is the Main H3K4 Di- and Tri-Methyltransferase Throughout Drosophila Development. Genetics. 2012;190:91–100. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.135863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Garruss AS, Gao X, Morgan MA, Cook M, Smith ER, Shilatifard A. The Mll2 branch of the COMPASS family regulates bivalent promoters in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert A, Henderson JM, Ross KG, Cowles MW, Torres J, Zayas RM. Epigenetic regulation of planarian stem cells by the SET1/MLL family of histone methyltransferases. Epigenetics. 2013;8 doi: 10.4161/epi.23211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham PW, Whittle R. Trithorax: a new homeotic mutation of Drosophila melanogaster causing transformations of abdominal and thoracic imaginal segments. Molecular and General Genetics. 1980;179:607–614. [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Alvarado AS. Flow cytometry methods for the study of cell-cycle parameters of planarian stem cells. Developmental Dynamics. 2009;238:1111–1117. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharchenko PV, Alekseyenko AA, Schwartz YB, Minoda A, Riddle NC, Ernst J, Sabo PJ, Larschan E, Gorchakov AA, Gu T, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2011;471:480–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzin B, Tillib S, Sedkov Y, Mizrokhi L, Mazo A. The Drosophila trithorax gene encodes a chromosomal protein and directly regulates the region-specific homeotic gene fork head. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2478–2490. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapan SW, Reddien PW. Transcriptome Analysis of the Planarian Eye Identifies ovo as a Specific Regulator of Eye Regeneration. CellReports. 2012;2:294–307. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Johnstone SE, Young RA. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray-based analysis of protein location. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:729–748. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim DA, Huang YC, Swigut T, Mirick AL, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Wysocka J, Ernst P, Alvarez-Buylla A. Chromatin remodelling factor Mll1 is essential for neurogenesis from postnatal neural stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman LC, Andersen IS, Reiner AH, Li N, Aanes H, Østrup O, Winata C, Mathavan S, Müller F, Aleström P, et al. Prepatterning of Developmental Gene Expression by Modified Histones before Zygotic Genome Activation. Developmental Cell. 2011:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan M, Herz HM, Smith ER, Zhang Y, Jackson J, Washburn MP, Florens L, Eissenberg JC, Shilatifard A. The COMPASS Family of H3K4 Methylases in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4310–4318. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06092-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien P, Bermange A, Murfitt K, Jennings J, Sánchez Alvarado A. Identification of Genes Needed for Regeneration, Stem Cell Function, and Tissue Homeostasis by Systematic Gene Perturbation in Planaria. Developmental Cell. 2005;8:635–649. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink JC, Gurley KA, Elliott SA, Sanchez Alvarado A. Planarian Hh Signaling Regulates Regeneration Polarity and Links Hh Pathway Evolution to Cilia. Science. 2009;326:1406–1410. doi: 10.1126/science.1178712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb SM, Gotting K, Ross E, Sánchez Alvarado A. SmedGD 2.0: The Schmidtea mediterranea genome database. Genesis. 2015 doi: 10.1002/dvg.22872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb SM, Ross E, Sánchez Alvarado A. SmedGD: the Schmidtea mediterranea genome database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36:D599–606. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. Methylation of Lysine 4 on Histone H3: Intricacy of Writing and Reading a Single Epigenetic Mark. Molecular cell. 2007;25:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Alvarado A, Newmark PA, Robb SM, Juste R. The Schmidtea mediterranea database as a molecular resource for studying platyhelminthes, stem cells and regeneration. Development. 2002;129:5659–5665. doi: 10.1242/dev.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scimone ML, Kravarik KM, Lapan SW, Reddien PW. Neoblast specialization in regeneration of the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Stem cell reports. 2014;3:339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scimone ML, Srivastava M, Bell GW, Reddien PW. A regulatory program for excretory system regeneration in planarians. Development. 2011;138:4387–4398. doi: 10.1242/dev.068098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Shao NY, Liu X, Maze I, Feng J, Nestler EJ. diffReps: detecting differential chromatin modification sites from ChIP-seq data with biological replicates. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solana J, Kao D, Mihaylova Y, Jaber-Hijazi F, Malla S, Wilson R, Aboobaker A. Defining the molecular profile of planarian pluripotent stem cells using a combinatorial RNA-seq, RNAi and irradiation approach. Genome Biology. 2012;13:R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-3-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl BD, Ohba R, Cook RG, Allis CD. Methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 is highly conserved and correlates with transcriptionally active nuclei in Tetrahymena. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14967–14972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanny JC, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Allis CD. Ubiquitylation of histone H2B controls RNA polymerase II transcription elongation independently of histone H3 methylation. Genes Dev. 2007;21:835–847. doi: 10.1101/gad.1516207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terranova R, Agherbi H, Boned A, Meresse S, Djabali M. Histone and DNA methylation defects at Hox genes in mice expressing a SET domain-truncated form of Mll. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6629–6634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507425103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theunissen TW, Powell BE, Wang H, Mitalipova M, Faddah DA, Reddy J, Fan ZP, Maetzel D, Ganz K, Shi L, et al. Systematic identification of culture conditions for induction and maintenance of naive human pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:471–487. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thi-Kim Vu H, Rink JC, McKinney SA, McClain M, Lakshmanaperumal N, Alexander R, Sánchez Alvarado A. Stem cells and fluid flow drive cyst formation in an invertebrate excretory organ. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.07405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wolfswinkel JC, Wagner DE, Reddien PW. Single-cell analysis reveals functionally distinct classes within the planarian stem cell compartment. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vastenhouw NL, Zhang Y, Woods IG, Imam F, Regev A, Liu XS, Rinn J, Schier AF. Chromatin signature of embryonic pluripotency is established during genome activation. Nature. 2010;464:922–926. doi: 10.1038/nature08866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DE, Ho JJ, Reddien PW. Genetic Regulators of a Pluripotent Adult Stem Cell System in Planarians Identified by RNAi and Clonal Analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D, Neumuller RA, Buckner M, Ayers K, Li H, Hu Y, Yang-Zhou D, Pan L, Wang X, Kelley C, et al. A regulatory network of Drosophila germline stem cell self-renewal. Dev Cell. 2014;28:459–473. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying QL, Wray J, Nichols J, Batlle-Morera L, Doble B, Woodgett J, Cohen P, Smith A. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu BD, Hanson RD, Hess JL, Horning SE, Korsmeyer SJ. MLL, a mammalian trithorax-group gene, functions as a transcriptional maintenance factor in morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10632–10636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.