Abstract

Multiple studies have shown correlates of immune activation with microbial translocation and plasma LPS during HIV infection. It is unclear whether this activation is due to LPS, residual viral replication, or both. Few studies have addressed the effects of persistent in vivo levels of LPS on specific immune functions in humans in the absence of chronic viral infection or pathological settings such as sepsis. We previously reported on a cohort of HIV negative men with subclinical endotoxemia linked to alterations in CD4/CD8 T cell ratio and plasma cytokine levels. This HIV negative cohort allowed us to assess cellular immune functions in the context of different subclinical plasma LPS levels ex vivo without confounding viral effects. By comparing 2 samples of differing plasma LPS levels from each individual, we now show that subclinical levels of plasma LPS in vivo significantly alter T cell proliferative capacity, monocyte cytokine release and HLA-DR expression, and induce TLR cross-tolerance by decreased phosphorylation of MAPK pathway components. Using this human in vivo model of subclinical endotoxemia, we furthermore show that plasma LPS leads to constitutive activation of STAT1 through autocrine cytokine signaling, suggesting that subclinical endotoxemia in healthy individuals might lead to significant changes in immune function that have thus far not been appreciated.

Introduction

LPS is an abundant and potently pro-inflammatory constituent of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Systemic LPS exposure (endotoxemia) has been linked to inflammation and immune activation in a range of pathologies, including inflammatory bowel disease (1) and HIV infection (2). Increasing evidence suggests that low-grade inflammation linked to LPS significantly slows or prevents wound healing and resolution of inflammation (3). However, pre-treatment with very low doses of LPS can have opposite effects and increase subsequent immune responses (4, 5). Although multiple studies have shown correlates of immune activation with microbial translocation in HIV infection (2, 6), it is difficult to dissociate immune activation linked to residual viral replication (7, 8) from that linked to microbial translocation and endotoxemia (2). Consequently, the causality and directionality of these correlations remain unclear (9).

LPS is recognized by TLR4 in conjunction with several accessory proteins that enable recognition of LPS to induce pro-inflammatory responses (10, 11). Activation of TLRs can alter subsequent TLR responses by inducing tolerance or priming (12). In vitro studies in human monocytes showed that exposure to LPS (TLR4) led to subsequent increased responses to ssRNA and inactivated HIV-1 (TLR8) and vice versa, suggesting cross-priming between TLRs 4 and 8 (13). These effects appear to be TLR-specific, as no effects were observed for TLR2 (13). Furthermore, in vitro studies in human dendritic cells showed synergistic and tolerizing interactions between TLRs 3, 4, and 8 depending on stimulus combinations and timing (14). In addition, intraperitoneal injections of LPS resulted in long-term hematopoietic stem cell senescence and compromised immunity in mice (15), suggesting that interdependent effects of TLR activation are likely to alter immune functions in the context of constant/repeated TLR stimulation, as might be the case in chronic infections and recurrent subclinical endotoxemia.

Endotoxin tolerance has been extensively studied in vitro and in animals, and is observed in humans during sepsis, septic shock, trauma, and meningococcal infections (16). Less is known about the immunological response to subclinical doses of LPS (3), and few studies have addressed the effects of different in vivo levels of endotoxemia on immune function in humans in the absence of pathologies or infections. Intravenous administration of LPS in healthy volunteers decreased the number of circulating lymphocytes in peripheral blood (17). However, the study assessed the effects of a single, high dose of LPS that caused clinical symptoms including headache, chills, vomiting, myalgia and fever, and therefore likely recapitulates the effects of acute bacteremia (18), rather than frequent subclinical endotoxemia as has been observed in HIV infection and inflammatory bowel disease (1, 2). A later study enrolled healthy male volunteers to establish a human in vivo model of endotoxin tolerance by intravenous administration of low doses of LPS for 5 consecutive days (19). Although clinical symptoms (increased body temperature and heart rate) observed after LPS administration were significantly lower at day 5 compared to day 1 post injection, symptoms at day 5 remained elevated above pre-injection measurements on that day, suggesting this model does not completely recapitulate subclinical levels of endotoxin exposure.

We previously reported on a cohort of HIV negative men with subclinical endotoxemia that correlated with decreased CD4/CD8 T cell ratio, elevated plasma cytokine levels and markers of T cell exhaustion (20). Using this HIV negative population as an in vivo model of subclinical endotoxemia in the absence of confounding HIV infection and associated viral effects, we assessed the effects of subclinical endotoxemia on cellular immune functions ex vivo. Specifically, we characterized the effects of different in vivo endotoxemia levels at 2 different sample points on ex vivo T cell proliferation, monocyte cytokine secretion, TLR and HLA-DR expression, and TLR-induced phosphorylation of signaling pathways. In this study, we provide evidence that subclinical endotoxemia in HIV negative subjects significantly alters T cell proliferative capacity, monocyte cytokine production and HLA-DR expression, and induces TLR cross-tolerance by decreasing phosphorylation of MAPK pathway components. Furthermore, we show that LPS-driven constitutive cytokine production leads to activation of STAT1, suggesting that recurrent subclinical endotoxemia in healthy individuals might lead to significant changes in immune function that have thus far not been appreciated.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects and sample collection

HIV negative subjects were enrolled on IRB approved protocols at Fenway Health Boston and Massachusetts General Hospital. Peripheral blood samples were drawn into acid citrate dextrose vacutainer tubes (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). HIV-negative status was confirmed by OraQuick® Advance HIV1/2 Rapid Antibody Test (OraSure Technologies, Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA) and Alere Determine™ HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo (Alere Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Blood was centrifuged and plasma collected and cryopreserved at −80°C. PBMC were isolated by density gradient centrifugation as previously described (21) and either cryopreserved or processed for analysis by flow cytometry immediately after isolation. Subjects were grouped according to relative fold differences in plasma LPS at different time points. Subject characteristics are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Subject Demographics

| Subject Characteristics | Total | Group 1 (hi-lo) | Group 2 (med-lo) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Subjects (n) | 30 | 7 | 7 |

| Age Range (years, min-max) | 21–53 | 22–51 | 21–48 |

| Average Age (years ± StDev) | 36 ± 11 | 36 ± 12 | 32 ± 12 |

| Race/ethnicity (n, %) | |||

| African American | 5, 17% | 2, 29% | 2, 29% |

| Caucasian | 17, 57% | 4, 57% | 4, 57% |

| Hispanic | 7, 23% | 0 | 0 |

| Other/Unknown | 1, 3% | 1, 14% | 1, 14% |

| Plasma endotoxin levels (EU/ml) | |||

| Average high/medium sample | 17.31 | 72.92 | 0.54 |

| Average low sample | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.1 |

| Range (min-max) | 0.01–125.33 | 0.03–125.33 | 0.0–2.24 |

| Average fold difference | 143.6 | 543.22 | 34.1 |

Subject demographics for all subjects (n=30), and for subjects in Group 1 (n=7) and Group 2 (n=7) are shown. Demographics shown include minimum, maximum and average age (years) per group, distribution of ethnicities within each group, as well as plasma endotoxin data. Endotoxin data shown are average levels (EU/ml) per sample point for each group, as well as the overall range within each group (EU/ml) and average fold difference between matches sample points within each group.

Tissue culture reagents

Cells were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% [v/v] heat inactivated FBS (R102) (both Sigma-Aldrich). Human rIL-2 was obtained from the National Institute of Health AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program. The following reagents and stimuli were used in tissue culture: LPS from Escherichia coli, CL097 Imidazoquinoline, HKLM3 and ssRNA40/LyoVec™ (all InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA), Dynabeads® Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 beads (LifeTechnologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) and GolgiStop™ (BD). Cell proliferation was assessed by addition of CellTrace™ Violet BMQC dye (LifeTechnologies).

Flow cytometry staining and gating

Fresh or cryopreserved PBMC were stained with the following reagents, depending on the panel: LIVE/DEAD® Fixable Red Dead Cell Stain and CellTracker™ Violet BMQC (both LifeTechnologies), anti-CD4 PE-Cy7, anti-CD16 Brilliant Violet 510™, anti-TLR4 BV421, anti-HLA-DR BV785 (all BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-CD8 FITC, anti-CD3 BUV395, anti-CD3 FITC, anti-CD14 BUV395, anti-CD4 Brilliant Violet 605™ (all BD), Fixable Viability Dye eFluor®780, and anti-TLR2 PE-Cy7 (all eBioscience). Following extracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Fix/Perm Medium (LifeTechnologies) and stained for intracellular anti-Ki67 Alexa Fluor®647 (BD), anti-TLR9 APC (eBioscience), anti-TLR7 FITC (Thermo Scientific, Tewksbury, MA, USA), and anti-TLR8 PE (abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were acquired on a BD™ LSRII flow cytometer using BD FACSDiva™ software (BD). Cytometer settings were kept consistent by tracking laser voltages using UltraRainbow Fluorescent Particles (Spherotech, Inc., Lake Forest, IL). Compensation settings were assessed using BD™ CompBead particles (BD) and compensation calculated and applied in FACSDiva™ software. Samples were analyzed using FlowJo Flow Cytometry Analysis Software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). Gating strategies: 1) Confirmation of CD33 enrichment/depletion: PBMC were gated on FSC versus SSC, followed by CD3 negative or positive cells, and CD14 versus CD16 (for CD3 negative) and CD4 versus CD8 (for CD3 positive) as shown in Supplemental Figure S2. 2) Proliferation assessed by expression of Ki67: Lymphocytes were gated by FSC versus SSC, live cells by exclusion dye, singlets by FSC-W versus SSC-W, and T cells by CD3 positive cells followed by CD4 versus CD8. Ki67 positive gates were set for either CD3+CD4+ or CD3+CD8+ T cells. 3) Proliferation following stimulation and staining with CellTrace™ Violet BMQC dye: Lymphocytes were gated by FSC versus SSC, live cells by exclusion dye, singlets by FSC-W versus SSC-W, and T cells by CD3 positive cells followed by CD4 versus CD8. Levels of proliferation (CellTrace, BV421 channel) for CD3+CD4+ or CD3+CD8+ T cells were assessed as outlined below. 4) Surface expression of TLRs and HLA-DR on monocyte subsets: Non-lymphocytes were gated by FSC versus SSC, live cells by exclusion dye, and singlets by FSC-W versus SSC-W. Total monocytes were gated by excluding CD14 and CD16 double-negative cells, and monocyte populations gated for classical (CD14+CD16−), intermediate (CD14+CD16+) and inflammatory (CD14dimCD16+) monocytes. TLR and HLA-DR expression levels were assessed by MFI4 for each monocyte population.

Monocyte enrichment and stimulation

Cryopreserved PBMC were thawed, washed twice with R10 and enriched/depleted for monocytes using the EasySep™ Human CD33 Positive Selection Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (STEMCELL Technologies Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada) and as previously described (22). CD33enr5 cells were plated at 106 cells/ml in flat bottom tissue culture plates (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and stimulated with R10 (vehicle), LPS (10 ng/ml), CL097 (1μg/ml), HKLM (108 cells/ml), or ssRNA (5μg/ml) for 18h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Supernatants were removed and stored at −80°C.

T cell proliferation assay

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed and washed twice with R10 and re-suspended at 106cells/ml in R10 supplemented with rIL-2 (50 U/ml). Cells were stained with 0.5 μM CellTrace™ Violet dye according to the manufacturer’s instructions and subsequently stimulated with R10 (vehicle) or anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads® (cell:bead ratio = 1:1) for 3, 4, or 5 days at 37°C, 5% CO2. Following stimulation, cells were washed, stained and fixed for flow cytometry as outlined above. Division cycles were calculated using FlowJo software and proliferation levels were adjusted for cell number per division at each time point as previously described (23).

Cytokine multi-analyte assays

Cytokine and chemokine expression levels in supernatants were measured in duplicate using a Milliplex® Human Cytokine/Chemokine 29-Plex Magnetic Bead Panel according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore, Chicago, IL, USA). Samples were acquired on a Bio-Plex® 3D Suspension Array System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and xPonent® software (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) and analyzed using Bio-Plex Manager software version 6.0 (Bio-Rad). Samples where technical duplicates had a differential of the mean/standard deviation ≤ 2 were excluded and cytokine measurement repeated. Extrapolated values below the range of the standard curve were set at assay detection minimum (=3.2 pg/ml).

Analysis of phosphorylation patterns following TLR stimulation

Levels of phosphorylation in cell lysates following stimulation were analyzed using a 10-plex MAPK/SAPK Signaling Magnetic Bead Panel (Millipore) measuring ERK1/2 MAPK (Thr185/Tyr187), STAT1 (Tyr701), JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), MEK1 (Ser217/221), MSK1 (Ser212), ATF2 (Thr71), p53 (Ser15), HSP27 (Ser78), c-Jun (Ser73), and p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, CD33enr monocytes were isolated as described above and stimulated with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 0, 15, 30 and 60 min following overnight rest in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml Brefeldin A and 50 ng/ml GolgiStop™. Cell supernatants were removed and cells lysed in kit specific lysis buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors (Millipore) with 1:100 protease inhibitor cocktail added (Millipore). Cell lysates were stored at −80°C. Samples were acquired on a Bio-Plex® 3D Suspension Array System (Bio-Rad) and xPonent® software (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) and median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of bound antibodies used as a readout for levels of phosphorylation.

Plasma endotoxin quantification

Plasma endotoxin levels were assessed using the Pierce LAL Chromogenic Endotoxin Quantitation Kit (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Endotoxin-masking plasma factors were deactivated by sonication and heat inactivation at 75°C. Optical density was measured at 405 nm using a Sunrise™/Magellan™ plate reader data analysis software (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland). Standard curve calculations and EU6 extrapolations were performed in Prism® (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) with background levels subtracted. Endotoxin negative values of zero were set to 0.01 EU/ml to allow graphing on a logarithmic scale.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses and graphic outputs were generated using Prism®, Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), and JMP® 11.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Gaussian sample distributions were assessed by Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Results were considered significant at p<0.05, and indicated as follows: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Contingency distributions were analyzed by Chi-square test for trend or two-sided Fisher’s exact test. Two-way comparisons were performed using paired or unpaired 2-tailed t-test or Mann Whitney test. Group comparisons were performed by 1-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test or by 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures with Holm-Sidak’s post-test. For 2-way ANOVA analyses, significant differences within group to baseline are signified as follows: ‡p<0.05, ‡‡p<0.01, ‡‡‡p<0.001. Correlation analyses were performed using Spearman rank correlations. PLSDA7 (24) with stepwise variable selection was used to determine multivariate cytokine profiles comparing different time points. Partial least squares regression transforms a set of correlated explanatory variables into a new set of uncorrelated ‘latent’ (i.e., combined) variables and determines a multi-linear regression model by projecting the predicted variables and their corresponding observed values into the resulting new space. Accordingly, each sample is assigned a score that can be visualized using score plots. Latent variable loading plots can then be used to identify cytokine profiles that associate with the different time points. Prior to multivariate analysis, all data were normalized with mean centering and variance scaling. This involves subtracting the mean from each data column and dividing each column by its standard deviation, respectively. These normalization approaches are designed to reduce bias towards variables with naturally higher raw values or variance. Cross-validation was performed by iteratively excluding random subsets during model calibration and then using those data samples to test model predictions.

Results

In vivo levels of endotoxin alter CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation

We recently reported a high incidence of subclinical endotoxemia in a cohort of HIV negative men (20). Endotoxin levels detected in this particular cohort were comparable to those observed in HIV-positive individuals (Supplemental Figure S1), making this study population ideal for modeling in vivo effects of subclinical endotoxemia on immune cell function in the absence of HIV infection and associated viral effects. Presence of plasma endotoxin was associated with significantly decreased frequencies of CD4+Ki67+ and CD8+Ki67+ T cells (Figure 1A and B), suggesting decreased in vivo proliferation in subjects with detectable plasma LPS. This effect was dose-dependent, as levels of plasma LPS (EU/ml) correlated negatively with both CD4+Ki67+ and CD8+Ki67+ T cells in freshly isolated PBMCs (Figure 1C). In order to study the effects of subclinical endotoxemia in these HIV negative subjects in more detail, we divided the subjects into 2 groups based on differences in plasma LPS levels collected 1 month apart (Figure 1D and E). Group 1 included 7 subjects with >10 EU/ml in one sample (LPS hi) and <10 EU/ml in the other sample (LPS lo time point), while Group 2 contained subjects with similar levels of plasma LPS (<10 EU/ml) in both samples (termed LPS med and lo; Figure 1D and E, Table I). We next assessed the proliferative capacity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in both groups following stimulation.

Figure 1. Reduced Ki67 expression with increasing levels of plasma LPS.

Freshly isolated PBMCs from HIV negative males with and without detectable plasma LPS (limit of detection 0.01 EU/ml) were analyzed by flow cytometry. A) Frequencies of CD4+CDKi67+ T cells with group median are shown for subjects with no detectable plasma LPS (n=10, light grey squares) and those with detectable plasma LPS (n=25, dark grey squares). B) Frequencies of CD8+CDKi67+ T cells with group median are shown for subjects with no detectable plasma LPS (n=10, light grey circles) and those with detectable plasma LPS (n=25, dark grey circles). C) Spearman correlation of frequencies of CD4+CDKi67+ T cells (black squares) and CD8+CDKi67+ T cells (clear circles) with plasma LPS (EU/ml). D) Plasma LPS levels (EU/ml) for each subject (n=30) at two different sample points are shown. Subjects with EU/ml >10 in one of the two samples were assigned to Group 1 (n=7), subjects with EU/ml <10 in both samples and with minimal difference in LPS levels were assigned to Group 2 (n=7). E) Schematic illustration of sample allocation into groups 1 and 2 using individuals #2 and #27 (from 1D) as examples. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired Mann Whitney test and Spearman rank correlation. Significance is indicated as *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

Ex vivo proliferative capacity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is altered by plasma LPS levels

PBMCs were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads® in vitro for 3,4 and 5 days, and proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was assessed. Division cycles of the parent population were calculated and adjusted for cell number per division at each time point as previously described (23). At day 3 post stimulation, CD4+ T cells from LPS hi samples (Group 1) had undergone fewer division cycles compared to the matching LPS lo samples (Chi-square test: p<0.05, Figure 2 A). This difference was increased by day 4, where 39.1%, 7.1%, 2.4% and 1% of CD4+ T cells from the LPS hi samples had gone through 1, 2, 3 and 4 division cycles, respectively, compared to the LPS lo samples, where 20.6%, 16.4%, 8.7% and 2.3% of CD4+ T cells had divided 1, 2, 3 and 4 times, respectively (Chi-square test: p<0.01, Figure 2A). This difference was lost at day 5, where both LPS hi and LPS lo samples in Group 1 had gone through similar numbers of division cycles following stimulation (Figure 2A). In contrast, CD4+ T cells from Group 2 (LPS med versus LPS lo) divided at similar rates upon stimulation by day 3, with a transient increase in division cycles observed for the LPS med samples at day 4 (Chi-square test: P<0.01, Figure 2B), which was lost by day 5 post stimulation. No significant differences in proliferation of CD8+ T cells were observed between LPS hi and LPS lo samples from Group 1 at days 3, 4, or 5 post stimulation (Figure 2C). Similarly to patterns observed for CD4+ T cells from Group 2, CD8+ T cells from Group 2 (LPS med versus LPS lo) divided at similar rates upon stimulation by day 3, but CD8+ T cells exposed to slightly elevated levels of LPS in vivo (LPS med) proliferated at increased rates compared to CD8+ T cells from matched LPS lo samples at days 4 (Chi-square test: p<0.05, Figure 2D) and 5 (Chi-square test: p<0.05, Figure 2C). Taken together, these data indicate that higher levels of subclinical LPS can delay initial levels of CD4+ T cell proliferation upon stimulation, while intermediate levels of subclinical LPS can reduce proliferation of stimulated CD8+ T cells at later time points. Changes in the proliferating capacity of T cells might be due in part to alterations in cytokine environment in vivo, and therefore we looked at the impact of LPS on monocyte cytokine responses in vitro.

Figure 2. LPS affects CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferative capacity.

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed, washed and re-suspended at 106cells/ml in R10 supplemented with rIL-2 (50 U/ml). Cells were stained with 0.5μM CellTrace™ Violet dye and subsequently stimulated with R10 (vehicle) or anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads® for 3, 4, or 5 days. Proliferation was assessed by flow cytometry and division cycles calculated and adjusted for cell number per division at each time point as previously described (see methods). Division cycles are depicted as <1 (no proliferation, clear), >1, >2, >3 and >4 completed cycles of proliferation (shades of grey). A) Pie chart depicting percent of CD4+ T cells in each division cycle following stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads® at the LPS hi (left panel) and LPS lo (right panel) samples from Group 1. B) Pie chart depicting percent of CD4+ T cells in each division cycle following stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads® at the LPS med (left panel) and LPS lo (right panel) samples from Group 2. C) Pie chart depicting percent of CD8+ T cells in each division cycle following stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads® at the LPS hi (left panel) and LPS lo (right panel) samples from Group 1. D) Pie chart depicting percent of CD8+ T cells in each division cycle following stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads® at the LPS med (left panel) and LPS lo (right panel) samples from Group 2. Contingency analyses comparing samples within each group were performed by Chi-square test. Significance is indicated as *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

Subclinical endotoxemia levels dictate ex vivo monocyte cytokine secretion profiles and induce cross-tolerance to TLR2, TLR7 and TLR8

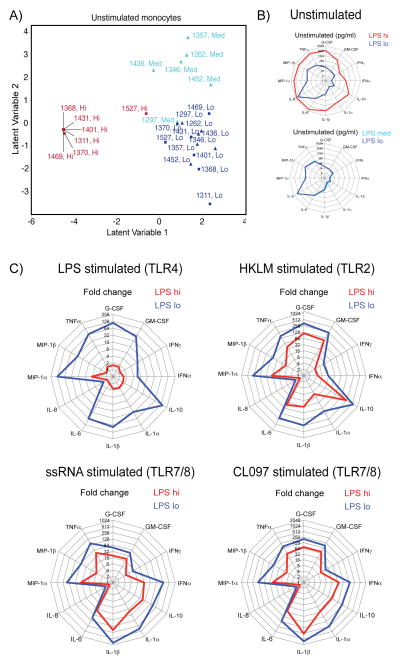

One of the hallmarks of LPS tolerance is altered cytokine production by monocytes upon stimulation, and monocytes from sepsis patients show drastically decreased production of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL-6, IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-12 upon ex vivo LPS challenge (16). Monocytes were isolated using a CD33 antibody (22), which resulted in significant enrichment of CD14+ and CD16+ monocyte populations in the CD33enr fraction (Supplemental Figure S2). CD33enr monocytes were cultured with or without stimuli, and cytokine secretion and supernatants assessed by multiplex assay for 29 human cytokines and chemokines. PLSDA revealed distinct separation between monocytes from LPS hi and lo samples in Group 1 (red and navy blue squares), as well as between LPS med and lo samples for Group 2 (light blue and navy blue triangles; Figure 3A), suggesting significantly different cytokine secretion profiles ex vivo in the absence of stimulation which are dictated by the LPS levels the cells were exposed to in vivo. Separation of LPS samples by PLSDA was driven by secretion of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IFNα2, and TNFα (Table II). Accordingly, monocytes from LPS hi samples (Group 1) secreted significantly elevated levels of IL-6, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IFNα2, TNFα, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFNγ, IL-10, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-8 compared to matched LPS lo samples (Figure 3B). In contrast, monocytes from LPS med and LPS lo samples in Group 2 produced similar levels of cytokines (Figure 3B). All LPS groups secreted similar levels of IP-10, IL-7, IL-12p70, IL-12p40, MCP-1, Eotaxin, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, and TNF-β (data not shown). Next, monocyte cytokine secretion after stimulation with different TLR ligands was analyzed. Analysis of cytokine secretion patterns following stimulation with LPS (TLR4), HKLM (TLR2), CL097 (TLR7/8) and ssRNA (TLR7/8) by PLSDA revealed separation of the different samples in both groups according to the in vivo plasma LPS levels they were exposed to (Supplemental Figure S3A). Monocyte cytokine secretion levels above those observed in unstimulated cells (shown in Figure 3B) were assessed as fold change for each sample. In line with previous reports from in vitro LPS tolerance models and monocytes from sepsis patients (16), monocytes from LPS hi samples did not significantly increase cytokine production after LPS stimulation, whereas monocytes from the matching LPS lo samples (Group 1) increased cytokine production (except for IL-8) by ~8 to ~150-fold (Figure 3C). Interestingly, production of anti-inflammatory IL-10 in response to LPS stimulation did not increase in monocytes from LPS hi samples (Figure 3C), which is contradictory to previous observations in LPS tolerance (16). Changes in cytokine production (other than IL-8) following stimulation with HKLM, CL097 and ssRNA were also lower in monocytes from LPS hi samples compared to matched monocytes from LPS lo samples (Figure 3C). Induction of cytokines following stimulation with LPS, HKLM, CL097 and ssRNA was similar in monocytes from matched LPS med and lo samples from Group 2 (Supplemental Figure S3B). These data suggest that monocytes exposed to higher levels of subclinical LPS in vivo produce high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and are refractory to further stimulation through different TLRs.

Figure 3. Effects of endotoxemia on monocyte cytokine secretion patterns before and after in vitro TLR stimulation.

CD33enr monocytes were cultured for 18h in media (unstimulated), or with LPS (10ng/ml), heat killed Listeria monocytogenes (HKLM; 108 bacteria/ml), ssRNA (5μg/ml), or CL097 (1μg/ml). A) Cytokine expression profiles of unstimulated monocytes were analyzed by PLSDA. Separation of individuals and samples by latent variables are shown for Group 1 with LPS hi (red squares) and LPS lo (navy blue squares) samples, and for Group 2 with LPS med (light blue triangle) and LPS lo (navy blue triangle) samples. B) Radar plots showing median cytokine concentration (pg/ml) for unstimulated CD33enr monocytes from Group 1 (upper plot) for LPS hi (red) and LPS lo (navy blue) samples, and for Group 2 (lower plot) for LPS med (light blue) and LPS lo (navy blue) samples. C) Radar plots showing median cytokine secretion levels (fold change over unstimulated) for CD33enr monocytes stimulated with LPS (upper left plot), HKLM (upper right plot), ssRNA (lower left plot), or CL097 (lower right plot) for 18h for LPS hi (red) and LPS lo (navy blue) samples from Group 1.

Table II.

PLSDA variable ranking of plasma cytokines

| Immune marker | F-ratio | Prob>F |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 39.771 | 0.0000001 |

| MIP-1α | 25.226 | 0.0000016 |

| MIP-1β | 22.24 | 0.0000042 |

| IFNα2 | 18.764 | 0.0000147 |

| TNFα | 17.183 | 0.0000273 |

| G-CSF | 15.143 | 0.0000636 |

| IL-10 | 14.598 | 0.0000807 |

| GM-CSF | 11.708 | 0.0003113 |

| IL-12p70 | 8.412 | 0.0018118 |

| IL-1β | 6.146 | 0.0072717 |

| Eotaxin | 6.134 | 0.0073284 |

| IL-7 | 5.035 | 0.0153599 |

| IL-12p40 | 4.222 | 0.0274282 |

| EGF | 4.128 | 0.0293934 |

| IL-1α | 3.658 | 0.0417546 |

| IL-8 | 2.731 | 0.0862357 |

| IFNγ | 2.625 | 0.0940036 |

| IP-10 | 1.589 | 0.2257848 |

Plasma cytokine data obtained by multi-analyte assay were analyzed by PLSDA and variables ranked by F-ratio (highest to lowest, middle column) and p-values (right column, Prob>F).

In vivo LPS levels induce changes in HLA-DR, but not TLR, expression on monocyte subsets

Tolerance to LPS has been linked to changes in TLR surface expression, transient reductions in circulating monocytes, and decreased surface expression of HLA-DR (16, 25), which in turn can lead to decreased antigen presentation and impaired T cell proliferation (26). We therefore assessed whether in vivo LPS levels had altered circulating monocyte populations and their TLR and HLA-DR expression levels. Monocyte populations were defined as CD14+CD16−, CD14+CD16+, and CD14dimCD16+ monocytes as previously described (27) (Figure 4A). No differences in monocyte population frequencies between samples were observed (data not shown). Furthermore, analyses of surface expression levels of TLRs 2 and 4, and intracellular expression levels of TLRs 7 and 8 assessed by flow cytometry (MFI) revealed similar levels of TLR expression on all monocyte subsets (Supplemental Table SI). We subsequently analyzed levels of HLA-DR expression on monocyte populations by flow cytometry (Figure 4B). CD14dimCD16+ monocytes from LPS hi samples (Group 1) expressed significantly lower levels of surface HLA-DR compared to CD14dimCD16+ monocytes from matched LPS lo samples (Figure 4C), while HLA-DR expression levels on CD14dimCD16+ monocytes remained similar between samples in Group 2 (Figure 4C). No differences in HLA-DR expression were observed on CD14+CD16+ monocytes (data not shown). In contrast, HLA-DR expression levels were significantly higher in CD14+CD16− monocytes from LPS hi samples compared to those from matched LPS lo samples in Group 1 (Figure 4D). No differences in HLA-DR expression on CD14+CD16− monocytes were observed between samples in Group 2 (Figure 4D). Overall, these data suggest that in vivo LPS levels alter monocyte MHC class II expression levels on CD14+CD16− and CD14dimCD16− monocytes, but do not alter monocyte expression of TLRs 2, 4, 7, 8 and 9, implying that differences in cytokine expression in response to TLR stimulation likely involve mechanisms downstream of TLR-ligand binding.

Figure 4. Differential HLA-DR surface expression in monocyte subsets exposed to LPS in vivo.

CD33enr monocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry and monocyte populations defined according to CD14 and CD16 expression levels. A) Representative flow plot showing gating for classical (CD14+CD16−), intermediate (CD14+CD16+), and inflammatory (CD14dimCD16+) monocytes. B) Representative histogram showing relative expression levels of HLA-DR on monocyte subsets. C) Tukey box and whiskers plot (median, 5–95 percentiles and individual outliers) of HLA-DR levels (MFI) on inflammatory monocytes from individuals in Group 1 (grey boxes) and Group 2 (clear boxes) comparing LPS samples. D) Tukey box and whiskers plot (median, 5–95 percentiles and individual outliers) of HLA-DR levels (MFI) on classical monocytes from individuals in Group 1 (grey boxes) and Group 2 (clear boxes) comparing LPS samples. Statistical analyses were performed using paired Mann Whitney test. Significance is indicated as *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

Elevated plasma endotoxin levels alter MAPK and transcription factor phosphorylation patterns, and result in constitutive STAT1 phosphorylation through autocrine cytokine feedback mechanisms

Several studies have shown decreased activation of MAPK and NFκB signaling pathways in LPS tolerant monocytes (16, 25). Phosphorylation patterns of signaling molecules downstream of TLR4 were analyzed by multiplex assay (28) in CD33enr monocytes stimulated with LPS for 0, 15, 30 and 60 minutes. Following LPS stimulation, phosphorylation of MAPK pathway components MEK1, p38 and MSK1 increased significantly over unstimulated cells within 30–60 minutes in monocytes from LPS lo samples in Group 1 and both samples in Group 2 (Figure 5A), while monocytes from LPS hi samples (Group 1) were refractory to LPS stimulation, and no significant increases in phosphorylation were observed (Figure 5A). Phosphorylation of HSP27 was significantly increased within 30 minutes of stimulation in monocytes from Group 2 and in monocytes from LPS lo samples in Group 1, but not in monocytes from LPS hi samples in Group 1 (Figure 5B). Furthermore, HSP27 phosphorylation at 60 min was significantly higher in LPS lo compared to LPS hi monocytes (Group 1, Figure 5B). Similarly, monocytes from LPS hi samples (Group 1) did not increase phosphorylation of transcription factors ATF2 and c-JUN in response to LPS stimulation, and ATF2 phosphorylation at 60min was significantly higher in LPS lo monocytes compared to LPS hi monocytes (Group 1, Figure 5C). Remarkably, baseline phosphorylation of STAT1 was significantly elevated in monocytes from LPS hi samples compared to monocytes from LPS lo samples in Group 1, as well as compared to baseline levels of LPS med and LPS lo monocytes from Group 2 (Figure 5C). Levels of STAT1 phosphorylation in monocytes from LPS hi samples did not change and remained significantly elevated above all other groups at 15, 30 and 60 min post stimulation (Figure 5C). Since STAT1 phosphorylation is not driven directly by TLR4 signaling, we investigated whether constitutive activation of STAT1 in the LPS hi monocytes was due to autocrine signaling in response to elevated cytokine secretion observed in these cells (Figure 3). Monocytes were cultured in the presence of Brefeldin A and GolgiStop™ overnight to inhibit cytokine secretion and subsequently stimulated with LPS. In line with our hypothesis, inhibition of cytokine secretion significantly reduced STAT1 phosphorylation in LPS hi monocytes at baseline and following LPS stimulation (Figure 6). Taken together, these data suggest that elevated in vivo LPS levels significantly reduce phosphorylation of signaling pathways downstream of TLR4 in monocytes, and lead to constitutive activation of STAT1 through autocrine cytokine signaling in these cells.

Figure 5. Phosphorylation patterns of signaling pathways downstream of TLR4 are altered by levels of in vivo endotoxemia.

CD33enr monocytes were cultured in media (unstimulated), or stimulated with LPS (10ng/ml) for 15, 30, or 60 minutes. Cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylation of signaling pathways by multiplex assay. A) Relative levels of phosphorylation (MFI) of MAPK signaling components are shown for Group 1 (no pattern) and Group 2 (hashed bars) comparing changes in phosphorylation of MEK, p38, JNK and MSK1 over time for LPS hi (clear bars), LPS lo (grey bars), LPS med (hashed clear bars), and LPS lo (hashed grey bars). B) Relative levels of phosphorylation (MFI) of HSP27 are shown for Group 1 (no pattern) and Group 2 (hashed bars) comparing changes in phosphorylation over time for LPS hi (clear bars), LPS lo (grey bars), LPS med (hashed clear bars), and LPS lo (hashed grey bars). C) Relative levels of phosphorylation (MFI) of transcription factors are shown for Group 1 (no pattern) and Group 2 (hashed bars) comparing changes in phosphorylation of ATF2, c-JUN and STAT1 over time for LPS hi (clear bars), LPS lo (grey bars), LPS med (hashed clear bars), and LPS lo (hashed grey bars). Statistics: Group comparisons were performed by 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures with Holm-Sidak’s post-test. Significant differences for comparisons to baseline within each group (e.g. 60 min LPS hi versus 0 min LPS hi) are indicated as ‡p<0.05, ‡‡p<0.01, ‡‡‡p<0.001. Significant differences for comparisons between groups at the same stimulation time point (e.g. 60 min LPS hi versus 60 min LPS lo for Group 1) are indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001.

Figure 6. STAT1 phosphorylation in LPS hi monocytes is driven by autocrine cytokine signaling.

CD33enr monocytes were cultured in in the presence (+) of absence (−) of Brefeldin A (BFA; 1μg/ml) and GolgiStop™ (GS; 50ng/ml), and left unstimulated or stimulated with LPS (10ng/ml) for 60 minutes. Cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylation of STAT1 by multiplex assay. Fold changes in STAT1 phosphorylation relative to unstimulated, untreated LPS hi monocytes are shown for Group 1 (no pattern) and Group 2 (hashed bars) comparing LPS hi (clear bars), LPS lo (grey bars), LPS med (hashed clear bars), and LPS lo (hashed grey bars). Statistics: Paired comparisons were performed by 1-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparison post-test. Significant differences are indicated as **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we characterized the effects of different levels of naturally occurring subclinical endotoxemia on immune function in HIV negative subjects. Previous studies have used animal and human models of LPS tolerance by administration of one or several doses of LPS (15, 17, 19) associated with clinical symptoms. Little is known about the effects of low doses of LPS on immune function in humans without clinical symptoms (3), and this is the first report using a cohort with naturally occurring subclinical endotoxemia. We herein show that subclinical endotoxemia alters T cell proliferation, monocyte cytokine production and HLA-DR expression. The levels of plasma LPS that cells were exposed to furthermore induced tolerance to TLR4, TLR2, and TLR7/8 stimulation by decreasing phosphorylation of MAPK pathway components and transcription factors ATF2 and c-JUN. Moreover, our data indicate that LPS-induced cytokine production contributes to constitutive activation of STAT1, suggesting that frequent exposures to subclinical LPS in otherwise healthy individuals might lead to significant changes in immune function.

Frequencies of Ki67+ T cells correlated negatively with plasma LPS levels, suggesting that levels of LPS were associated with reduced T cell proliferation in vivo. Our data are discordant with a study reporting a positive correlation between Ki67+CD38+CD4+ and Ki67+CD38+CD8+ T cells and plasma LPS in HIV positive immunologic non-responders on antiretroviral therapy (29), and further highlight the need to study endotoxemia effects in HIV negative subjects, allowing delineation of LPS effects in the absence of co-infections or other pathologies. This, in turn, will provide better insight into the possible contribution of low-level LPS to immune activation observed in HIV positive patients (as opposed to effects of ongoing low level viral replication). We hypothesize that the observed discrepancy between this study and ours is due to viral or treatment effects in the cohort described by Marchetti et al., which are not present in our HIV negative cohort. We further showed that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells exposed to intermediate levels of LPS in vivo proliferated at higher levels following stimulation in vitro compared to those exposed to lower LPS levels. Such differential effects of LPS have been reported previously, where pre-treatment with high or low doses of LPS lead to reduced or augmented responses to a second dose, respectively (4, 5). Our data suggest that different levels of subclinical endotoxemia might have substantial effects on T cell responses to infections, depending on the type and timing of stimulus and endotoxin levels present.

Our results showing refractory cytokine responses following TLR4 stimulation of monocytes exposed to LPS in vivo are in line with the literature (16). We further showed tolerization of monocytes stimulated with TLR2 and TLR7/8 ligands, supporting previous reports of LPS-induced cross-tolerance (13, 14). A more remarkable observation was that even though monocytes from LPS hi samples were refractory to further stimulation, they produced very high levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the absence of stimulus, even though these cells had not been exposed to LPS since isolation. In fact, plasma (and any LPS present) was removed during isolation of PBMCs from fresh blood, and cells were subsequently washed multiple times during cryopreservation, thawing, enrichment for CD33+ cells, and before culture in sterile media for 18 hours. These observations suggest that cells retained their “LPS stimulated” state for a considerable amount of time in the absence of contemporaneous TLR signaling. This is in line with studies showing that exposure to LPS for 1 hour was sufficient to induce a refractory state to further LPS challenges in human monocytes for at least 5 days in vitro (30). Such long-lasting phenotypic changes suggest substantial effects on monocyte function, as further evidenced by changes in HLA-DR expression on monocyte subsets, which in turn has been linked to decreased antigen presentation and impaired T cell proliferation in human monocytes tolerized to LPS in vitro (26).

LPS tolerance in murine cells has been linked to changes in TLR4 transcripts (31) and TLR surface expression (32). Another study reported changes in NF-κB and c-JUN phosphorylation, but not downregulation of surface TLR4 (33). In the current study, signaling through the MAPK pathway and downstream transcription factors was impaired in refractory monocytes, while TLR expression levels remained unchanged. Interestingly, elevated levels of cytokine secretion in the absence of stimulus did not translate to increased baseline MAPK signaling. However, monocytes exposed to higher levels of LPS in vivo had significantly increased baseline phosphorylation of STAT1, suggesting constitutive activation of this transcription factor in the refractory monocytes. This activation is not driven directly by TLR4 signaling, but due to autocrine signaling in response to LPS-driven cytokine production. STAT1 is phosphorylated in response to interferons, growth factors, and other cytokines, including IL-6 (34) and IL-13 (35). However, since we did not observe any differences in IL-13 production between LPS hi and lo monocytes, it is unlikely that increased STAT1 phosphorylation in this cohort is due to IL-13 signaling. Activation of STAT1 is critical for immunity against both viral and mycobacterial infections, but constitutive phosphorylation of STAT1 has been linked to both autoimmunity as well as impaired development of IL-17-producing T cells and increased susceptibility to Candida albicans (34).

Recent studies have introduced the concept of ‘trained immunity’, whereby pre-treatment with small doses of LPS prime the innate immune system for subsequent challenge, leading to beneficial outcomes in subsequent infections (36, 37). However, this process is thought to involve changes in circulating monocyte subpopulations from CD14+CD16− to CD14dimCD16+, changes in expression levels of pattern recognition receptors such as TLRs, and different functional phenotypes characterized by a switch in cytokine expression profiles rather than changes in overall amounts of the same cytokines (36), none of which was evident in this cohort exposed to different levels of subclinical LPS. Circulating monocytes have important effector functions during homeostasis (38) and during infections (39), and our data indicate that elevated levels of subclinical LPS may induce an inflammatory state characterized by increased cytokine production and consequent STAT1 activation rather than a beneficial ‘priming’ state which might be promoted by lower levels of subclinical endotoxemia. This in turn has been postulated to contribute to reduced wound healing and multiple pathologies, including atherosclerosis, diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis in populations with frequent elevated levels of plasma endotoxin (3). Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that exposure to LPS and IFNγ (which is produced by the LPS hi monocytes), enhances MDSC8 function, which in turn leads to suppression of CD8+ T cell proliferation in mice (40). This is in line with our observations of decreased ex vivo CD8+Ki67+ T cell frequency with subclinical endotoxemia (Figure 1). Finally, STAT1 inhibition was shown to increase MDSC infiltration into lungs after bacterial infections (41), suggesting an important role for this signaling pathway in the resolution of inflammation. This in turn indicates that constitutive activation of STAT1 observed in LPS hi monocytes could have detrimental effects for the resolution of inflammation in response to pathogens or allergens in these subjects, warranting further investigations into LPS effects and possible treatment with LPS-neutralizing agents (42).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all blood donors, study participants and clinical staff and coordinators at Fenway Health, the Ragon Institute, and Massachusetts General Hospital. We are grateful to Dr. Eileen Scully for helpful discussions. We also thank the Ragon Institute Flow Cytometry Core.

Footnotes

Funding for this study was provided by the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard and the NIH [grant number R01 AI078784].

R10: RPMI with 10% [v/v] heat inactivated FBS

HKLM: Heat killed Listeria monocytogenes

MFI: Median Fluorescence Intensity

CD33enr: CD33-enriched

EU: endotoxin unit

PLSDA: Partial least square discriminant analysis

MDSC: myeloid-derived suppressor cell

References

- 1.Caradonna L, Amati L, Magrone T, Pellegrino NM, Jirillo E, Caccavo D. Enteric bacteria, lipopolysaccharides and related cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease: biological and clinical significance. Journal of endotoxin research. 2000;6:205–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nature medicine. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris MC, Gilliam EA, Li L. Innate immune programing by endotoxin and its pathological consequences. Frontiers in immunology. 2014;5:680. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heremans H, Van Damme J, Dillen C, Dijkmans R, Billiau A. Interferon gamma, a mediator of lethal lipopolysaccharide-induced Shwartzman-like shock reactions in mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1990;171:1853–1869. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.6.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shwartzman G. Studies on Bacillus Typhosus Toxic Substances : I. Phenomenon of Local Skin Reactivity to B. Typhosus Culture Filtrate. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1928;48:247–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.48.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang W, Lederman MM, Hunt P, Sieg SF, Haley K, Rodriguez B, Landay A, Martin J, Sinclair E, Asher AI, Deeks SG, Douek DC, Brenchley JM. Plasma levels of bacterial DNA correlate with immune activation and the magnitude of immune restoration in persons with antiretroviral-treated HIV infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2009;199:1177–1185. doi: 10.1086/597476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buzon MJ, Massanella M, Llibre JM, Esteve A, Dahl V, Puertas MC, Gatell JM, Domingo P, Paredes R, Sharkey M, Palmer S, Stevenson M, Clotet B, Blanco J, Martinez-Picado J. HIV-1 replication and immune dynamics are affected by raltegravir intensification of HAART-suppressed subjects. Nature medicine. 2010;16:460–465. doi: 10.1038/nm.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatano H, Jain V, Hunt PW, Lee TH, Sinclair E, Do TD, Hoh R, Martin JN, McCune JM, Hecht F, Busch MP, Deeks SG. Cell-based measures of viral persistence are associated with immune activation and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)-expressing CD4+ T cells. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;208:50–56. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatano H. Immune activation and HIV persistence: considerations for novel therapeutic interventions. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2013;8:211–216. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32835f9788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gioannini TL, Teghanemt A, Zhang D, Coussens NP, Dockstader W, Ramaswamy S, Weiss JP. Isolation of an endotoxin-MD-2 complex that produces Toll-like receptor 4-dependent cell activation at picomolar concentrations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:4186–4191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306906101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gioannini TL, Weiss JP. Regulation of interactions of Gram-negative bacterial endotoxins with mammalian cells. Immunol Res. 2007;39:249–260. doi: 10.1007/s12026-007-0069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagchi A, Herrup EA, Warren HS, Trigilio J, Shin HS, Valentine C, Hellman J. MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways in synergy, priming, and tolerance between TLR agonists. J Immunol. 2007;178:1164–1171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mureith MW, Chang JJ, Lifson JD, Ndung’u T, Altfeld M. Exposure to HIV-1-encoded Toll-like receptor 8 ligands enhances monocyte response to microbial encoded Toll-like receptor 2/4 ligands. AIDS. 2010;24:1841–1848. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ad89a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Napolitani G, Rinaldi A, Bertoni F, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Selected Toll-like receptor agonist combinations synergistically trigger a T helper type 1-polarizing program in dendritic cells. Nature immunology. 2005;6:769–776. doi: 10.1038/ni1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esplin BL, Shimazu T, Welner RS, Garrett KP, Nie L, Zhang Q, Humphrey MB, Yang Q, Borghesi LA, Kincade PW. Chronic exposure to a TLR ligand injures hematopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5367–5375. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends in immunology. 2009;30:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juffermans NP, Paxton WA, Dekkers PE, Verbon A, de Jonge E, Speelman P, van Deventer SJ, van der Poll T. Up-regulation of HIV coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4(+) T cells during human endotoxemia and after stimulation with (myco)bacterial antigens: the role of cytokines. Blood. 2000;96:2649–2654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pers C, Gahrn-Hansen B, Frederiksen W. Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicemia in Denmark, 1982–1995: review of 39 cases. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1996;23:71–75. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Draisma A, Pickkers P, Bouw MP, van der Hoeven JG. Development of endotoxin tolerance in humans in vivo. Critical care medicine. 2009;37:1261–1267. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819c3c67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer CD, Tomassilli J, Sirignano M, Tejeda MR, Arnold KB, Che D, Lauffenburger DA, Jost S, Allen T, Mayer KH, Altfeld M. Enhanced immune activation linked to endotoxemia in HIV-1 seronegative MSM. AIDS. 2014 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naranbhai V, Bartman P, Ndlovu D, Ramkalawon P, Ndung’u T, Wilson D, Altfeld M, Carr WH. Impact of blood processing variations on natural killer cell frequency, activation, chemokine receptor expression and function. Journal of immunological methods. 2011;366:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dowling DJ, Tan Z, Prokopowicz ZM, Palmer CD, Matthews MA, Dietsch GN, Hershberg RM, Levy O. The ultra-potent and selective TLR8 agonist VTX-294 activates human newborn and adult leukocytes. PloS one. 2013;8:e58164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkins ED, Hommel M, Turner ML, Battye FL, Markham JF, Hodgkin PD. Measuring lymphocyte proliferation, survival and differentiation using CFSE time-series data. Nature protocols. 2007;2:2057–2067. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau KS, Juchheim AM, Cavaliere KR, Philips SR, Lauffenburger DA, Haigis KM. In vivo systems analysis identifies spatial and temporal aspects of the modulation of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis and proliferation by MAPKs. Science signaling. 2011;4:ra16. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van ‘t Veer C, van den Pangaart PS, van Zoelen MA, de Kruif M, Birjmohun RS, Stroes ES, de Vos AF, van der Poll T. Induction of IRAK-M is associated with lipopolysaccharide tolerance in a human endotoxemia model. J Immunol. 2007;179:7110–7120. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.7110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolk K, Docke WD, von Baehr V, Volk HD, Sabat R. Impaired antigen presentation by human monocytes during endotoxin tolerance. Blood. 2000;96:218–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong KL, Yeap WH, Tai JJ, Ong SM, Dang TM, Wong SC. The three human monocyte subsets: implications for health and disease. Immunol Res. 2012;53:41–57. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kano G, Almanan M, Bochner BS, Zimmermann N. Mechanism of Siglec-8-mediated cell death in IL-5-activated eosinophils: role for reactive oxygen species-enhanced MEK/ERK activation. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2013;132:437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchetti G, Bellistri GM, Borghi E, Tincati C, Ferramosca S, La Francesca M, Morace G, Gori A, Monforte AD. Microbial translocation is associated with sustained failure in CD4+ T-cell reconstitution in HIV-infected patients on long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2008;22:2035–2038. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283112d29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.del Fresno C, Garcia-Rio F, Gomez-Pina V, Soares-Schanoski A, Fernandez-Ruiz I, Jurado T, Kajiji T, Shu C, Marin E, Gutierrez del Arroyo A, Prados C, Arnalich F, Fuentes-Prior P, Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Potent phagocytic activity with impaired antigen presentation identifying lipopolysaccharide-tolerant human monocytes: demonstration in isolated monocytes from cystic fibrosis patients. J Immunol. 2009;182:6494–6507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medvedev AE, Kopydlowski KM, Vogel SN. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction in endotoxin-tolerized mouse macrophages: dysregulation of cytokine, chemokine, and toll-like receptor 2 and 4 gene expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:5564–5574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomura F, Akashi S, Sakao Y, Sato S, Kawai T, Matsumoto M, Nakanishi K, Kimoto M, Miyake K, Takeda K, Akira S. Cutting edge: endotoxin tolerance in mouse peritoneal macrophages correlates with down-regulation of surface toll-like receptor 4 expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:3476–3479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato S, Nomura F, Kawai T, Takeuchi O, Muhlradt PF, Takeda K, Akira S. Synergy and cross-tolerance between toll-like receptor (TLR) 2- and TLR4-mediated signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2000;165:7096–7101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boisson-Dupuis S, Kong XF, Okada S, Cypowyj S, Puel A, Abel L, Casanova JL. Inborn errors of human STAT1: allelic heterogeneity governs the diversity of immunological and infectious phenotypes. Current opinion in immunology. 2012;24:364–378. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doucet C, Jasmin C, Azzarone B. Unusual interleukin-4 and -13 signaling in human normal and tumor lung fibroblasts. Oncogene. 2000;19:5898–5905. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Netea MG, Quintin J, van der Meer JW. Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell host & microbe. 2011;9:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saeed S, Quintin J, Kerstens HH, Rao NA, Aghajanirefah A, Matarese F, Cheng SC, Ratter J, Berentsen K, van der Ent MA, Sharifi N, Janssen-Megens EM, Ter Huurne M, Mandoli A, van Schaik T, Ng A, Burden F, Downes K, Frontini M, Kumar V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Ouwehand WH, van der Meer JW, Joosten LA, Wijmenga C, Martens JH, Xavier RJ, Logie C, Netea MG, Stunnenberg HG. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science. 2014;345:1251086. doi: 10.1126/science.1251086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327:656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Auffray C, Sieweke MH, Geissmann F. Blood monocytes: development, heterogeneity, and relationship with dendritic cells. Annual review of immunology. 2009;27:669–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greifenberg V, Ribechini E, Rossner S, Lutz MB. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell activation by combined LPS and IFN-gamma treatment impairs DC development. European journal of immunology. 2009;39:2865–2876. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poe SL, Arora M, Oriss TB, Yarlagadda M, Isse K, Khare A, Levy DE, Lee JS, Mallampalli RK, Chan YR, Ray A, Ray P. STAT1-regulated lung MDSC-like cells produce IL-10 and efferocytose apoptotic neutrophils with relevance in resolution of bacterial pneumonia. Mucosal immunology. 2013;6:189–199. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guinan EC, Barbon CM, Kalish LA, Parmar K, Kutok J, Mancuso CJ, Stoler-Barak L, Suter EE, Russell JD, Palmer CD, Gallington LC, Voskertchian A, Vergilio JA, Cole G, Zhu K, D’Andrea A, Soiffer R, Weiss JP, Levy O. Bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (rBPI21) and fluoroquinolone mitigate radiation-induced bone marrow aplasia and death. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:110ra118. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.