Abstract

We report the fabrication of enthalpy arrays and their use to detect molecular interactions, including protein–ligand binding, enzymatic turnover, and mitochondrial respiration. Enthalpy arrays provide a universal assay methodology with no need for specific assay development such as fluorescent labeling or immobilization of reagents, which can adversely affect the interaction. Microscale technology enables the fabrication of 96-detector enthalpy arrays on large substrates. The reduction in scale results in large decreases in both the sample quantity and the measurement time compared with conventional microcalorimetry. We demonstrate the utility of the enthalpy arrays by showing measurements for two protein–ligand binding interactions (RNase A + cytidine 2′-monophosphate and streptavidin + biotin), phosphorylation of glucose by hexokinase, and respiration of mitochondria in the presence of 2,4-dinitrophenol uncoupler.

Understanding the thermodynamics of molecular interactions is central to biology and chemistry. Although a number of methods are available, calorimetry is the only universal assay for the complete thermodynamic characterization of these interactions. Under favorable circumstances, the enthalpy, entropy, free energy, and stoichiometry of a reaction can be determined (1, 2). In addition, calorimetry does not require any labeling or immobilization of the reactants and hence offers a completely generic method for characterizing the interactions. Indeed, titration calorimetry is widely used in both drug discovery and basic science, but its use is severely constrained to a small number of very high-value measurements by the large sample requirements and long measurement times. No currently available methods for calorimetric measurements lend themselves to modern approaches in which large libraries of compounds, ranging from small molecules in combinatorial libraries to proteins and other macromolecules, are studied.

Here we report a low-cost nanocalorimetry detector that can be used as a high-throughput assay tool to detect enthalpies of binding interactions, enzymatic turnover, and other chemical reactions. The detectors are made by using microscale fabrication technology, resulting in a nearly 3 orders of magnitude reduction in both the sample quantity and the measurement time over conventional microcalorimetry. The fabrication technology is low-cost and enables fabrication of 96-detector arrays, which we call enthalpy arrays, on large substrates. Accordingly, the technology will scale to high-volume production of disposable arrays. This increase in performance and reduction in cost promises to enable calorimetry to be used to investigate a substantial number of samples. Nanocalorimetry in the enthalpy array format has valuable applications in proteomics for protein interaction and protein chemistry research and in high-throughput screening and lead optimization for drug discovery.

Materials and Methods

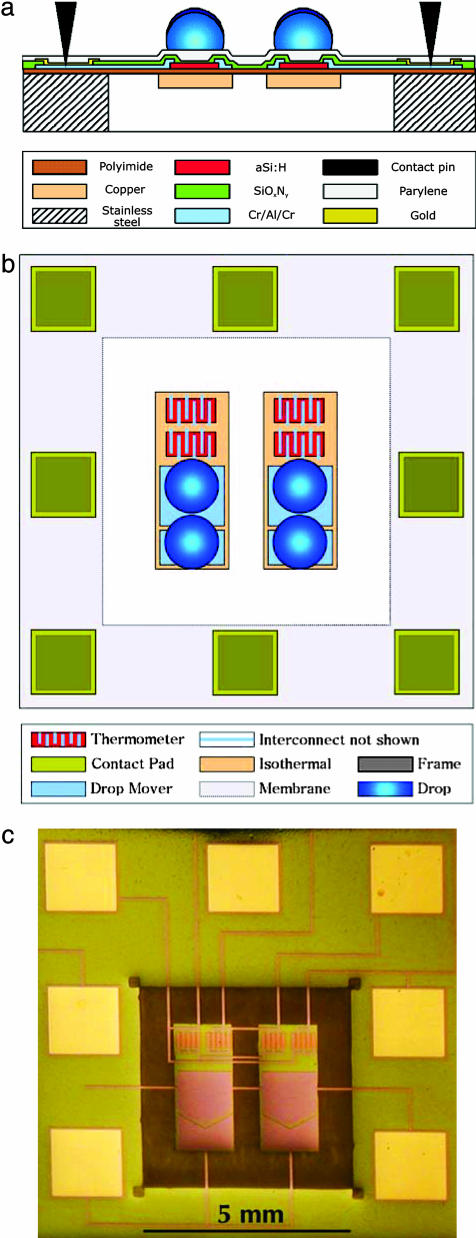

Device Fabrication. The schematic cross section of a nanocalorimeter detector is shown in Fig. 1a. The device consists of a thin (12.5-μm) polyimide membrane suspended over a cavity in a rigid stainless-steel support plate. The center region of the membrane contains two rectangular thermal equilibration areas consisting of 9-μm-thick copper islands etched on the bottom of the polyimide membrane. The measurement and reference regions of the detector are fabricated over these two areas. These regions are surrounded by electrical contact pads placed on top of the support plate, as shown in Fig. 1 b and c. Electrical connection is made through thin (0.91-mm) pogo pins that contact these pads.

Fig. 1.

Nanocalorimeter detector. (a) Detector fabrication schematic: cross-section view. (b) Design principle of the nanocalorimeter detector (with electrical interconnects not shown). (c) Single detector set from a 96-format array, photographed and enlarged. The adjacent measurement and reference regions are in the center of the polyimide isolation membrane, surrounded by electrical contact pads supported by an underlying frame.

Thermometers, metallization features, and interconnect metallization are located on the top of the polyimide membrane. The thermometers are fabricated from an n+ amorphous silicon film (200 nm thick) deposited by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition using silane and phosphine at 230°C. These films have a resistivity of 1.4 Ω·m. The metallization features and interconnect lines are made from an etched Cr/Al/Cr composite metal film. The arrays are coated with a 300-nm silicon oxynitride protective layer deposited by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition at 200°C using silane, ammonia, and nitrous oxide, and they are further coated with a 2-μm parylene film. Three of the materials, amorphous silicon, Cr/Al/Cr, and silicon oxynitride, are patterned by using photolithography with 50-μm design rules. This process requires dimensional stability of 50 μm and planarity of 300 μm for optical alignment and registration. The mechanical rigidity is accomplished by stretching the polyimide membrane over the rigid frame under tensile stress.

Measurement Protocols. We have measured enthalpies of reaction for several different types of biological interactions, including protein–ligand binding reactions, enzymatic reactions, and organelle activity. In each measurement, two drops (≈250 nl) are merged on a detector region to initiate a reaction. At the same time, two similar nonreacting drops are merged on the other detector region to provide a reference for the differential measurement. All measurements were performed at 21°C.

For the first protein–ligand binding reaction, a 250-nl drop containing 61 μM RNase A protein was mixed with a 250-nl drop containing 100 μM of the ligand 2′-cytidine 2′-monophosphate (CMP). After combining the drops, the final concentrations were 30.5 μM RNase A and 50 μM 2′-CMP. The buffer was 50 mM potassium acetate, pH 5.5. The RNase A and 2′-CMP solutions were purchased from Microcal (Amherst, MA) in a test kit sold for calibrating their microcalorimeters. The samples in the test kit were prepared by Microcal according to the procedure specified by Wiseman et al. (3). In the reference region, two 2′-CMP ligand drops were merged.

For the second protein–ligand binding reaction, a 240-nl drop containing 36 μM active streptavidin protein (1.25 mg/ml at 14 units/mg) was mixed with a 240-nl drop containing 377 μM d-biotin, a known ligand for streptavidin. The buffer was 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.0). After combining the drops, the final concentrations were 18 μM streptavidin and 190 μM biotin. The streptavidin and biotin were purchased from Sigma and used without additional purification. In the reference region, two biotin ligand drops were merged.

For the enzymatic reaction, a 250-nl drop containing an enzyme, 50 units/ml hexokinase, was mixed with a 250-nl drop containing 1 μM glucose substrate. The hexokinase activity level is based on the activity of the enzyme sample as reported by the supplier. Each drop contained 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.8) and 10 mM MgCl2 (4) as well as ≈100 μM ATP. (All materials were purchased from Sigma.) Before measurement, the hexokinase solution was dialyzed against the buffer/ATP solution (20 mM Tris·HCl at pH 7.8/10 mM MgCl2/100 μM ATP) to minimize heats of mixing in the measurements. The glucose solution was prepared by dissolving anhydrous glucose in an aliquot of the buffer/ATP solution in which the hexokinase had been dialyzed (after the dialysis). It was not possible to dialyze the glucose solution against the buffer solution because glucose has a lower molecular weight than ATP. In the measurement region, one enzyme drop was merged with one substrate drop, and in the reference region one buffer drop was merged with one substrate drop. After combining hexokinase and substrate drops, the hexokinase concentration was 25 units/ml, and the glucose concentration was 500 μM.

For the organelle reaction, we used 15.75 mg/ml of bovine heart mitochondria in 1.2 mM of 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) uncoupler (5), the buffer consisting of 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 2 mM KH2PO2, 10 mM succinate (respiratory substrate), 100 μM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCl2. All materials were prepared and supplied by MitoKor (San Diego). In the measurement region, one drop of 15.75 mg/ml mitochondria (including buffer and 1.2 mM DNP) was merged with one drop of 1.6 mM DNP plus buffer, and on the reference region, one drop of buffer was merged with one drop of 1.6 mM DNP plus buffer.

In each measurement, the baseline temperature drift was measured and subtracted from the data to yield the net temperature signal. In addition, the baseline temperature data was used to determine the noise of each signal. Specifically, the noise at 1 Hz bandwidth is reported by using a 1-sec running average of the baseline. The 1 Hz frequency corresponds approximately to the signal duration times.

Results and Discussion

Detector Design and Operation. As shown in Fig. 1, a detector cell consists of two identical adjacent detector regions that provide a differential temperature measurement. Each region contains two thermistors that are combined in an interconnected Wheatstone bridge. Each region also contains an electrostatic merging and mixing mechanism. The detector measures the temperature change arising from a chemical interaction after mixing of two small (≈250-nl) drops. The differential measurement enables very precise detection of the temperature rise in a sample under study because the temperature is measured relative to a reference specimen. The reference specimen interacts with the environment in concert with the sample under study, and it also undergoes mixing in concert with the sample under study, effectively subtracting out correlated background drifts in temperature and other common-mode artifacts. Amorphous silicon thermistors with a measured temperature coefficient of resistance of 0.028°C-1 are used to detect the small temperature changes.

The devices are fabricated on a thin polyimide membrane, which provides thermal isolation, reduces cost, and enables large-scale fabrication. For the current design, the thermal dissipation time is ≈1.3 sec, and we expect future improvements to increase this time by a factor of 3–5.

In a measurement, two drops containing materials of interest are placed on one of the detector regions in Fig. 1. Two drops of reference material are placed on the other region. After the drops come to thermal equilibration, they are isothermally merged and mixed in both regions at the same time. If any heat is evolved because of a chemical interaction in the merged drops, the temperature of that region changes relative to the temperature of the reference region, resulting in a change in the voltage output of the bridge.

To cancel the effects of heats of dilution and variations in the environment around the drops as much as possible, the reference drops are chosen to be similar to the measurement drops. To test the level of common mode rejection, we performed control experiments by using water drops on both sides of the detector. Ideally, the signal should be zero for such a measurement. In the control experiments, the differential temperature is within the noise of the n+ amorphous silicon thermistors, which is 50–100 μ°C rms. Thus, these results show that the differential measurement provides successful common mode rejection.

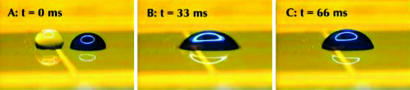

An essential component of the detection system is the electrostatic merging and mixing method. Here, one of the drops is placed asymmetrically across a 50-μm gap between two electrodes on the device surface, as shown in Fig. 2. With the application of a voltage (100 V) across the electrodes, an electrostatic force moves the drop until it covers equal amounts of both electrodes. The second drop is placed within the range of this motion and merges with the first drop when they touch. The electrostatic energy from the drop-merging device, coupled with the surface tension of the drops, causes the necessary mixing of materials. The mixing of blue dye shown in Fig. 2 demonstrates good mixing of the drops. Reaction data shown in later sections further support the premise that drop mixing is adequate because data show signals with magnitudes that would only be achieved with drops mixed well enough to achieve complete reactions. A hydrophobic surface is needed to minimize the adhesion of the drop. In addition to providing a protective barrier, the parylene layer provides the required hydrophobicity, enabling proper drop shape and movement.

Fig. 2.

Electrostatic merging/mixing of two 500-nl droplets of water at three different times, starting when a voltage is applied across the gap. One drop has blue coloring to visualize mixing. The noncolored drop is placed asymmetrically across the gap between two electrodes. The mixing started within the first 33 msec, even before surface tension caused the drop to take its final shape.

Each detector in the array is capable of detecting a 500 μ°C temperature change with a signal-to-noise ratio of 6, resulting from 250 ncal of heat released in a reaction volume of 500 nl. This level of sensitivity permits monitoring a ligand-binding reaction with a nominal binding enthalpy of -10 kcal/mol at a nominal concentration of 50 μM, which corresponds to 25 pmol of material. The sensitivity of the detector is limited by flicker noise in the n+ amorphous silicon thermometers, which is 1 order of magnitude higher than the intrinsic thermal (i.e., kBT) noise. A possible replacement for the n+ material is highly doped p+ amorphous silicon, which potentially has lower flicker noise (6, 7).

To validate the performance of the nanocalorimeter detector, we chose to measure some simple model systems that had been characterized previously by using microcalorimetry. As examples of small-molecule ligand binding to protein, the binding of 2′-CMP to RNase A and the binding of biotin to streptavidin were measured. As an example of an enzymatic reaction, the phosphorylation of glucose by hexokinase was measured. In addition, the power output of respiring, uncoupled mitochondria was monitored.

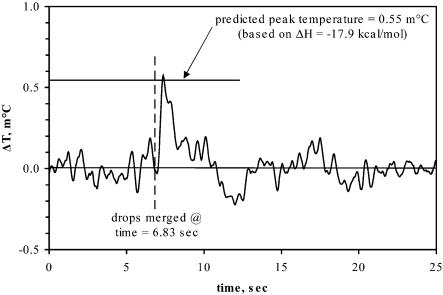

Binding Reactions. The binding of 2′-CMP to RNase A is well characterized (3). The sample used here had a Kd of 1.1 μM and a stoichiometry of 1:1, based on VP-ITC measurements provided with the test kit (Microcal). Fig. 3 shows the measured temperature change for the RNase–2′-CMP reaction using our nanocalorimeter, and it is in reasonable accord with the predicted height based on the enthalpy of reaction of ΔH = -17.9 kcal/mol, measured independently by using a Microcal VP-ITC microcalorimeter.

Fig. 3.

RNase A–2′-CMP reaction. Data are plotted as the differential change in temperature versus time. The time at which the RNase A and 2′-CMP drops were merged and the expected peak height based on the enthalpy of the reaction are indicated. The rms noise at a 1 Hz bandwidth is 64 μK.

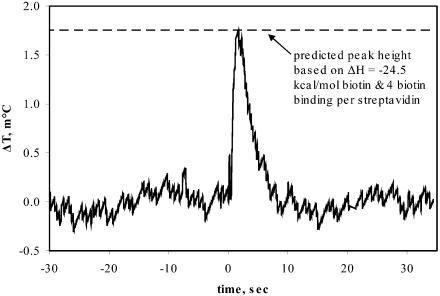

The binding of biotin to streptavidin is also well characterized (8, 9). The binding stoichiometry is 4:1, and the binding is very tight. According to Green (8), Kd = 4 × 10-14 M. Fig. 4 shows the measured temperature change for the streptavidin–biotin reaction using our nanocalorimeter, and it is in accord with the predicted height based on the enthalpy of reaction of ΔH = -24.5 kcal/mol from the literature (9).

Fig. 4.

Streptavidin–biotin reaction. Data are plotted as the differential change in temperature versus time. The streptavidin and biotin drops were merged at t = 0. The expected peak height based on the enthalpy of the reaction and the concentration of active protein is indicated. The rms noise at a 1 Hz bandwidth is 96 μK.

Screening large libraries of compounds for binding to drug targets has become an important activity in drug discovery and life science research. However, the large number of measurements required in combinatorial chemistry-based drug discovery or basic research in functional proteomics requires much higher throughput than can be achieved by traditional calorimetric measurements of the heat of reaction. Consequently, investigators have focused on other approaches, and they have been successful in developing a number of biochemical assays for high-throughput screening of molecular interactions. Presently, however, the biochemical assays being used for highthroughput studies generally require labeling or immobilization of at least one of the molecules under study (10). Although those assays can be implemented with low reagent consumption and can provide low-cost screening, the labeling of the reagents or modification of the biological system (e.g., immobilization) is time-consuming to develop, can have adverse effects with regards to the quality of the results, and does not enable a complete thermodynamic characterization of the interaction. The enthalpy array technology reported here addresses the need to investigate interactions without the substantial investment in assay development, without the risk of adversely affecting the result by modifying the reagents, and provides a more complete characterization. Furthermore, although the assay can be used for screening interactions with a well characterized target having a known ligand, it is especially valuable in cases in which no ligand is known for competitive assay development.

The nanocalorimeter can be used also for titration calorimetry to provide a more complete thermodynamic characterization of the interaction. In titration calorimetry, the concentration of one component is titrated against a fixed concentration of the other component, enabling the determination of the equilibrium constant (and, therefore, Gibbs free energy) of the reaction as well as the enthalpy. Indeed, conventional microcalorimetry has been used to characterize binding reactions, but it requires much larger sample sizes (1–2 ml) and much longer measurement times than the system described here. Approaches to nanocalorimetry reported by other investigators aim to overcome these same issues, but they do not include methods for isothermally merging and mixing drops and, consequently, are only able to make measurements after the temperature transients from mixing have dissipated (11–13). This limitation prevents measurement of fast binding reactions. Although those nanocalorimetry systems have been used effectively as physiometers, provided that the enzymatic reactions are sufficiently long, there have not been reports of the use of these systems to measure fast binding reactions similar to those in Figs. 3 and 4.

Enzymatic Reactions. The phosphorylation of glucose by hexokinase with ATP serves as a useful demonstration of an enzymatic reaction. To measure this reaction, a drop containing hexokinase was mixed with a drop containing glucose on the measurement region, and on the reference region a drop of buffer was mixed with a drop containing glucose. All drops also contained ATP, which is the limiting substrate because it is present in a smaller concentration than glucose. The hexokinase solution was dialyzed against the buffer to minimize heats of mixing in the measurements. Before use in the nanocalorimeter, the solutions were tested with a Microcal ITC calorimeter to verify the viability of the enzyme and to confirm that there was no appreciable heat of solution after mixing the glucose solution and buffer.

Fig. 5 shows the temperature change resulting from the reaction. With the concentrations used, the reaction completed very quickly, as expected based on the values of kcat = 270–450 sec-1 from the literature (14, 15). Although the duration could be extended by increasing the concentration of glucose and ATP to provide a longer-lived and thereby easier-to-measure reaction, it is worth noting that extending the reaction in this manner is not necessary with our detectors. Because other nanocalorimetry approaches have not reported the capability to detect the short-time behavior (11–13) that we can detect, to study this reaction, they would need to provide much more substrate, which is not always preferred.

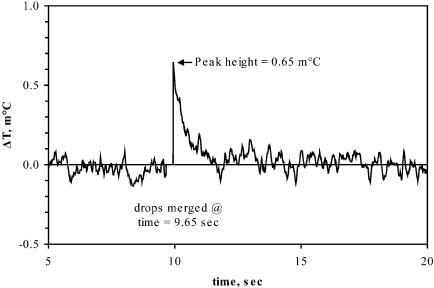

Fig. 5.

Enzymatic phosphorylation of glucose by hexokinase. Data are plotted as the differential change in temperature versus time. The time at which the hexokinase and glucose drops were merged is indicated. The maximum peak height is indicated. The rms noise at a 1 Hz bandwidth is 50 μK.

For comparison, we also performed a simulation of the heating from this reaction by using Michaelis–Menten kinetics for the enzymatic turnover and the empirically observed thermal decay time. The simulations predicted a peak temperature of 0.77 m°C at 0.9 sec after merging, whereas the data show a lower peak temperature and a faster decay. We attribute these discrepancies to hydrolysis of ATP before the reaction, which reduces the amount of phosphorylation that occurs in the measurement. One must also consider that there is some uncertainty in the values for parameters used in calculating the reaction kinetics. We used literature values of the enthalpy of reaction (-15 kcal/mol) and Km for ATP (180 μM) (16). These values are averages for types I and II hexokinase, which is appropriate because the sample used in this study was a mixture of the two isoenzymes. Because glucose is present in excess and at a relatively high concentration, we assumed it was present at saturating conditions at all times and, therefore, not important in terms of the reaction kinetics. We derived kcat[E], where [E] is the enzyme concentration, from the enzyme activity of 25 units/ml, stated in Measurement Protocols.

Mitochondrial Respiration. To demonstrate the application of the approach to measuring complex pathways, uncoupled mitochondrial respiration was measured (5). The samples and protocol were generously provided by MitoKor. This particular experiment was designed to measure respiration of mitochondria in the presence of DNP uncoupler (17). Uncoupled mitochondrial respiration generates sufficient heat [several mW/mg (personal communication with MitoKor based on their measurements for these specific reagents)] to produce a temperature change exceeding the device sensitivity at moderate concentrations of material.

On the measurement region of the detector, a drop of bovine heart mitochondria and DNP was merged with a drop containing DNP. Before merging, the drop containing the mitochondria was naturally depleted in O2 because of the high consumption rate by mitochondria relative to the rate of O2 diffusion into the drop. The drop of DNP, however, was saturated with oxygen. After merging, the mitochondria resumed uncoupled respiration as a result of the fresh supply of dissolved O2, as shown in Fig. 6. After ≈25 sec, the respiration reaches a maximum and then declines over time, consistent with the mitochondria consuming the dissolved O2 faster than it can diffuse into the drop from the surrounding air.

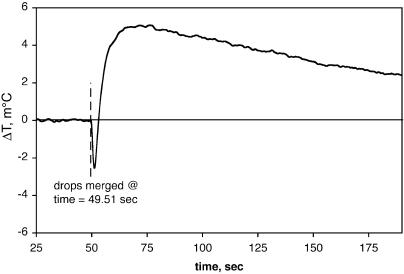

Fig. 6.

Mitochondrial respiration in the presence of DNP uncoupler. Data are plotted as the differential change in temperature versus time. The time at which mitochondria in the presence of DNP were mixed with additional DNP is indicated. The rms noise at a 1 Hz bandwidth is 69 μK.

Immediately after the drop-merging time, the temperature actually drops for ≈3 sec before rising. This result was unexpected and needs additional study, but the ability of the nanocalorimeter to detect such a response indicates again that it will provide a productive platform for studying details of interactions that would not be detectable with conventional microcalorimeters or other reported nanocalorimeter approaches (11–13).

Mitochondrial respiration is a process that involves a number of proteins and reactions as well as transport of species through membranes. This successful experiment validates not only the sensitivity of the system but also demonstrates that the electrostatic merging and mixing can be performed without causing adverse effects in systems as complicated as an organelle pathway.

Manufacturing Technology. As previously described, the application of calorimetry to large molecular systems requires a lowcost, fast method that can be performed with small amounts of material. The enthalpy array technology described here is designed to accomplish all three requirements.

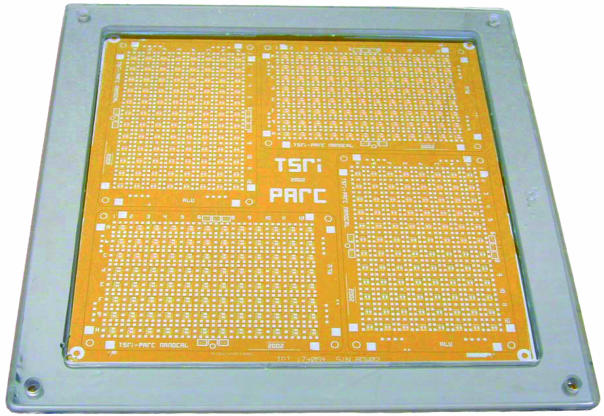

The technology enables the enthalpy arrays to be built by using low-cost fabrication processes. Enthalpy arrays are currently fabricated with the standard 96-detector format on 9-mm centers to interface with automated laboratory equipment. As shown in Fig. 7, the metallization patterning is done for four enthalpy arrays simultaneously on 26.6-cm square substrates. In the future, all of the process steps will be done with such multiarray processing on even larger substrates to further lower fabrication costs. Low costs enable disposable arrays to eliminate the possibility of contamination.

Fig. 7.

A four-array substrate undergoing outsourced processing.

Calorimetry provides a nearly universal assay for molecular interactions that previously has been too expensive in both time and required sample quantity for application to modern, large-scale investigations. The enthalpy array addresses both of these shortcomings. The large reduction in scale compared with conventional microcalorimetry reduces the sample requirements by nearly 1,000 times, and the highly parallel array design reduces the measurement times by a similar factor. As the reactions reported here illustrate, the enthalpy array can be applied to a very large range of biomolecular interactions of interest in biomedical research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Profs. Ray Stevens and Jeff Kelly for early helpful discussions.

Abbreviations: CMP, cytidine 2′-monophosphate; DNP, 2,4-dinitrophenol.

References

- 1.Weber, P. C. & Salemme, F. R. (2003) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13, 115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leavitt, S. & Freire, E. (2001) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11, 560-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiseman, T., Williston, S., Brandts, J. F. & Lin, L. (1989) Anal. Biochem. 179, 131-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott, L. G., Tolbert, T. J. & Williamson, J. R. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 317, 18-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stryer, L. (1995) Biochemistry (Freeman, New York), 4th Ed., p. 553.

- 6.Khera, G. M. & Kakalios, J. (1997) Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 56, 1918-1927. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johanson, R. E., Güneç, M. & Kasap, S. O. (2000) J. Non-Cryst. Solids 266–269, 242-246. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green, M. N. (1990) in Methods in Enzymology: Volume 184, Avidin-Biotin Technology, eds. Wilchek, M. & Bayer, E. A. (Academic, San Diego), pp. 51-67.

- 9.Wong, J., Chilkoti, A. & Moy, V. T. (1999) Biomol. Eng. 16, 45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seethala, R. & Fernandes, P. B., eds. (2001) Handbook of Drug Screening (Dekker, New York).

- 11.Johannessen, E. A., Weaver, J. M. R., Cobbhold, P. H. & Cooper, J. M. (2002) Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 2029-2031. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verhaegen, K., Van Gerwen, P., Baert, K., Hermans, L., Mertens, R. & Luyten, W. (1998) in Biocalorimetry: Applications of Calorimetry in the Biological Sciences, eds. Ladbury, J. E. & Chowdhry, B. Z. (Wiley, West Sussex, U.K.), pp. 225-231.

- 13.Verhaegen, K., Baert, K., Simaels, J. & Van Driessche, W. (2000) Sens. Actuators A Phys. 82, 186-190. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaji, A., Trayser, K. A. & Colowick, S. P. (1961) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 94, 798-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todd, M. J. & Gomez, J. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 296, 179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianconi, M. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 18709-18713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheffler, I. E. (1999) Mitochondria (Wiley–Liss, New York), pp. 225-229.