Abstract

Pre-mRNA splicing is a fundamental process in mammalian gene expression and alternative RNA splicing plays a considerable role in generating protein diversity. RNA splicing events are key to the pathology of numerous diseases, including cancers. Some tumors are molecularly addicted to specific RNA splicing isoforms making interference with pre-mRNA processing a viable therapeutic strategy. Several RNA splicing modulators have been recently characterized showing promise in pre-clinical studies. While the targets of most splicing modulators are constitutive RNA processing components, with undesirable side effects, selectivity for individual splicing events has been observed. Given the high prevalence of splicing defects in cancer, small molecule modulators of RNA processing represent a novel therapeutic strategy in cancer treatment. Here, we review their reported effects, potential mechanisms, and limitations.

Keywords: splicing modulators, cancer therapy

RNA splicing contributes to cancer vulnerability

Most human genes harbor introns which are removed during pre-mRNA splicing [1]. The splicing reaction is catalyzed by the spliceosome, a multi-subunit complex, comprised of small noncoding RNAs (U1,U2, U4, U5 and U6) and a myriad of associated proteins [2]. The spliceosome orchestrates two transesterification reactions necessary to remove introns and to join the adjacent exons. The spliceosome operates by step-wise formation of sub-complexes that recognize regulatory sequences and promote efficient splicing [2].

While many exons are constitutively spliced together, alternative splicing (AS) is a process during which specific exons are selectively included or excluded [2]. AS is of great physiological relevance as it enables the production of multiple protein isoforms from a single pre-mRNA molecule by the combinatorial use of splice sites [3, 4]. In addition to protein diversity, AS can also lead to reduced translation of mRNAs through introduction of a pre-mature stop codon leading to sequestration and degradation of transcripts in the nucleus; these exons are often referred to as poison exons [5, 6].

Since RNA splicing is an essential process in mammalian cells, splicing defects may affect the ability of cells to proliferate [7] and generation of specific splicing isoforms has recently been found to act as drivers of cancer [8–12]. In addition, global alterations in splicing behavior in cancer can be caused by changes in expression of splicing factors that may dictate an oncogenic splicing pattern [13–16], or by mutations that give rise to a specific splicing isoform with a potential to promote cancer [12].

The involvement of RNA splicing in promoting tumor growth represents a vulnerability which can be exploited for therapeutic purposes. In cases of isoform-specific cancer drivers, elimination of the cancer-associated splicing isoform may halt tumorigenicity or metastasis. Furthermore, cancer cells replicate rapidly and presumably use the splicing machinery more extensively. Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that these cells may be sensitive to global interference of their splicing machinery [17].

Here, we review cases of cancers in which AS isoforms are not merely bystanders in cancer progression but may be oncogenic drivers, and we highlight the use of small molecule modulators of splicing as emerging therapeutic agents. We focus our discussion on the modulation of specific splicing events and do not include approaches to restore global splicing patterns nor the use of antisense-based approaches to splicing regulation [18]. We highlight the emerging finding that many identified splicing modulators target constitutive splicing components, yet trigger gene-specific splicing alterations. The non-specific nature of their action raises the issue that their potential side-effects represent a major obstacle in their application in a clinical setting. Therefore, a complete understanding of their mode of action will be required for their success. Given the urgent need to fully characterize the molecular mechanisms of these under-explored, potentially powerful anti-tumorigenic agents, their development towards clinical use is a paradigm for the complementary interplay between basic and clinical research.

Splicing isoforms in cancer

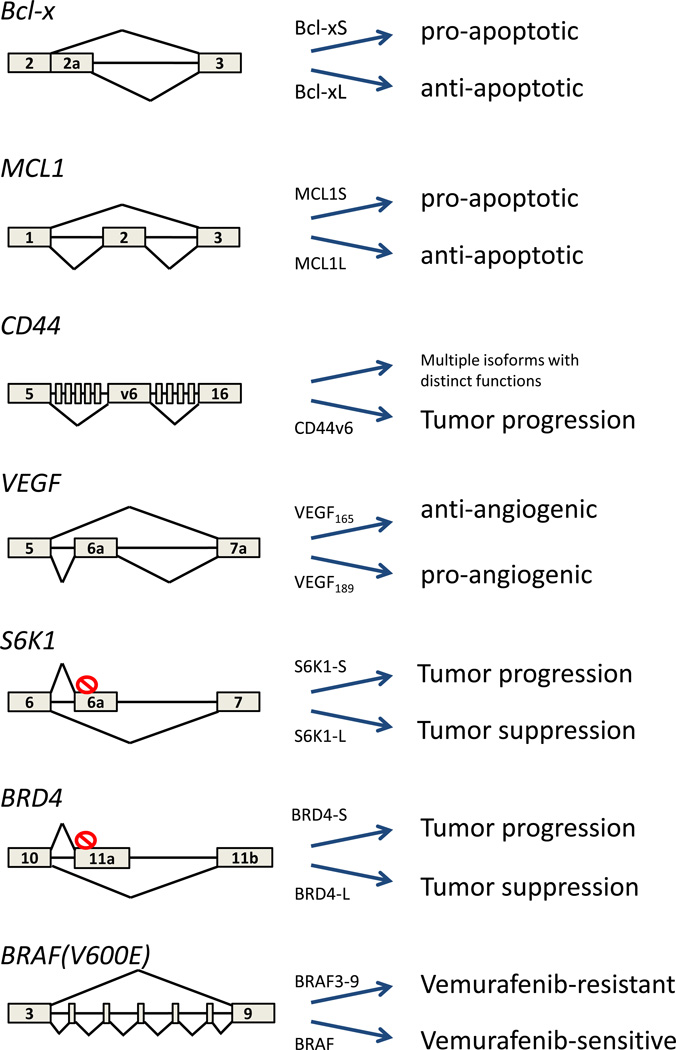

Numerous cases of splicing isoforms that drive or promote cancer progression have been identified over the years. One of the earliest oncogenic AS events described is that of the apoptosis gene Bcl-x [19], which generates two splicing isoforms, a short form (Bcl-xS) with pro-apoptotic properties and a long form (Bcl-xL) with an anti-apoptotic effect [8] (Fig. 1). Apoptosis is one of the hallmarks of cancer and as expected for highly cell-proliferative tissues, a wide range of tumors, including breast, colon and lung, exhibit a high amount of Bcl-xL, resulting in reduced apoptosis potential and providing the cancers with elevated cell survival [8, 20]. In line with a critical role for Bcl-xL in contributing to the proliferation potential of tumor cells, elimination of Bcl-xL by use of an antisense-oligonucleotide targeting the AS site promotes apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells [8]. Another member of the Bcl2 family of apoptotic regulators, MCL1 undergoes cancer-relevant AS similar to Bcl-x, producing a short pro-apoptotic isoform (MCL1S) [21] and a long anti-apoptotic (MCL1L) form [9] (Fig. 1). The use of anti-sense oligonucleotides to lower the MCL1L/1S ratio confers cell death and in this way, impairs cancer progression in skin basal cell carcinoma [22].

Figure 1. Cancer-relevant splicing isoforms.

Rectangles represent exons, lines represent introns and red crossed circles represent stop codons. Splicing outcome of the genes listed in this review.

Other cancer-related splicing patterns are more complex, such as for the transmembrane protein CD44 in tumors. Its pre-mRNA harbors 10 adjacent exons that are included in combinatorial fashion to give rise to multiple isoforms. CD44 isoforms that include the variant-exon 6 (CD44v6) are enriched in different kinds of cancer including colon, ovarian and head and neck [23–27] (Fig. 1). CD44v6 was also found to serve as a marker of colorectal cancer stem cells and to be necessary for migration and generation of metastatic colorectal tumors [10]. The cancer-promoting role of CD44v6 is apparent by the fact that targeting the isoform halts tumor cell adhesion and migration of ovarian cancer cells [28]. In line with a potential therapeutic application, antibodies to CD44v6 have shown promising results in human head and neck cancer in a phase 1 clinical trial [23]. Activation of the mTOR major proliferation pathway by the short isoform of the S6K1 kinase has also been reported to drive breast cancer; breast cancer cell lines and tumors possess high levels of the S6K1 short isoform and promote cancer progression [29] (29) (Fig. 1). In contrast, overexpression of the long isoform blocks transformation and its genetic ablation (knockout) induces tumor formation, suggesting that it harbors tumor suppressor activity [29].

Splicing isoforms also have the potential to affect tumor behavior globally. A relevant example is that of angiogenesis, a prominent hallmark of cancer, and which is affected by AS [30]. VEGF is secreted from cells in need of oxygen, triggering signaling cascades in endothelial cells and directing their growth to form blood vessels that allow nutrient and oxygen transport to the tumor [25]. Inclusion of exon 6a in VEGF promotes the production of the VEGF189 isoform and decreases the production of VEGF165 that excludes exon 6a (Fig. 1). A low VEGF165/VEGF189 ratio is induced following hypoxia to stimulate angiogenesis [30]. The fact that increasing the VEGF165/VEGF189 ratio from chromatin protein G9a silencing is sufficient to impair endothelial cell migration is suggestive of the potential benefits of VEGF isoforms’ ratio modulation in cancer therapy [30].

Splicing isoforms may also contribute to differences in tumor types. The bromodomain-containing gene BRD4 was originally described as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer [31]. However, subsequent studies in non-solid tumors revealed proto-oncogenic properties in lymphoma and leukemia [32] (Fig. 1). The effect of BRD4 is highly tissue-specific and the distinct functions of BRD4 may be attributed to the production of two distinct isoforms, which appear to have opposite functions in cancer. Overexpression of the short isoform, terminating at exon 11a, promotes metastasis and overexpression of the long isoform, terminating at exon 19, has a tumor suppressor effect [33]. It is tempting to speculate that promoting a high ratio of BRD4-L/BRD4-S may have cancer protective effects.

While the cancer promoting effects of these examples are mediated by changes in the ratio of normally occurring splicing isoforms, tumorigenic splicing isoforms may also arise due to oncogenic mutations. A prime example for an isoform-addicted cancer arisen from mutation is the secondary intronic mutation in the BRAF gene that leads to the generation in melanoma of a BRAF3–9 isoform lacking exons 4–8 [12, 34] (Fig. 1). The missense mutation V600E in BRAF is a common cause of melanoma and is found in more than 50% of patients. The mutation constitutively activates the MAPK pathway and promotes cell proliferation and cancer. BRAF(V600E) is the target of the very potent BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib; however, patients rapidly develop resistance to it. One of the resistance mechanisms is the secondary intronic mutation that gives rise to the BRAF3–9 isoform [12]. The production of BRAF3–9 confers vemurafenib-resistance and leads to tumor growth. Conversely, reduction of BRAF3–9 reduces the growth of resistant tumors [12].

Discovery of small molecule splicing modulators

The presence of cancer-specific splicing isoforms, which drive or promote tumor growth, makes them potential therapeutic targets. While RNAi-based methods and the use of antisense oligonucleotides are obvious approaches to control splicing isoform ratios in tumors, the difficulty of delivering RNAi and oligonucleotides in a clinical setting has prompted efforts to discover small molecule modulators of splicing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Small molecule pre-mRNA splicing modulators

| Compound name | Inhibition target | Observations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FR901464 (SSA) | SF3B1 | Inhibition of tumor growth of murine ascetic (P388), murine solid tumors (Colon 38 and Meth A) and human lung adenocarcinoma solid tumor (A549) in a xenograft mouse model | [35–37] |

| Meayamicin B | SF3B1 | Inhibition of tumor growth of human colorectal carcinoma (HCT-116) and PC-3 human prostate tumor (PC-3) in a xenograft mouse model | [49] |

| Sudemycins | SF3B1 | Inhibition of tumor growth of human rhabdomyosarcoma (rh18) in a xenograft mouse model | [50] |

| GEX1 | SF3B1 | Inhibition of tumor growth of SVT2 murine fibrosarcoma (SCT2), murine sarcoma (180) and in human lung adenocarcinoma solid tumor (A549) in a xenograft mouse model | [45, 46] |

| Pladienolides | SF3B1 | Inhibition of tumor growth of human BSY-1, PC-3, OVCAR-3, DU-145, WiDr, and HCT-116 cells and primary cultured cells from three colon cancer patients in a xenograft mouse model | [41–44, 77] |

| E7107 | SF3B1 | Inhibition of tumor growth of human breast (SY-1, MDA-MB-468), NSCLC (LC-6-JCK) and ovary (NIH:OVCAR-3) in a xenograft mouse model and used in a phase one clinical trial of colorectal, esophageal, pancreatic, gastric, renal and uterine solid tumors. | [51] |

| Isoginkgetin | First step of splicing | Prevention of stable recruitment of U4/U5/U6 snRNAs to 32P-labeled adenovirus major late (AdML) pre-mRNA in an in-vitro reaction in HeLa nuclear extract. | [53] |

| Clotrimazole | unknown | Splicing modulation of coilin intron 2 in cultured HeLa cells. | [58] |

| Flunarizine | unknown | Splicing modulation of coilin intron 2 in cultured HeLa cells. | [58] |

| Chlorhexidine | CLK family of SR kinases | Splicing modulation of RON exon 11 in cultured HeLa cells. | [58] |

| 1,4-heterocyclic | Second step of splicing | Prevention of the release of intron lariat and ligation of exons on Ad2 pre-mRNA in vitro in 293T nuclear extract. | [59] |

| 4-naphthoquinones | Second step of splicing | Prevention of the release of intron lariat and ligation of exons on Ad2 pre-mRNA in vitro in 293T nuclear extract. | [59] |

| Tetrocarcin A | First step of splicing | Spliceosome stalling of AdML pre-mRNA in HeLa nuclear extract and RP51A pre-mRNA in yeast extract | [60] |

| Indole | Second step of splicing | Spliceosome stalling of AdML pre-mRNA in HeLa nuclear extract and not RP51A pre-mRNA in yeast extract | [60] |

| naphthazarin | Second step of splicing | Spliceosome stalling of AdML pre-mRNA in HeLa nuclear extract and RP51A pre-mRNA in yeast extract | [60] |

| Madrasin | First step of splicing | Induction of cell cycle arrest in HEK293 and HeLa cultured cells | [57] |

| Inhibitors of protein acetylation (butyrolactone 3, anacardic acid and garcinol) and deacetylases (SAHA, DHC and splitomicin) | Intermediate steps | Stalled splicing complexes on MINX pre-mRNA in HeLa extract are associated with distinct steps of the splicing cycle | [62] |

| Topoisomerase I inhibitor (NB-506) | Prior to step one of splicing | Inhibition of SRSF1 phosphorylation and splicing of Bcl-X, CD44, SC35, and Sty in P388 cultured cells | [78] |

| Small peptides | First step of splicing | Antagonize in vitro binding of CDC5L to PLRG1 in HeLa nuclear cell extract and inhibit splicing of pBSAd1 pre-mRNA | [79] |

| Benzothiazole (TG003) | Clk1/Sty | Inhibition of Clk1/Sty kinase and as a result, SRSF1 phosphorylation and its dependent splicing of beta-globin pre-mRNA in vitro in HeLa and COS-7 cultured cells | [80] |

| Indole derivatives | exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) | Prevention of early splicing events required for HIV splicing mini HIV reporter in cultured HeLa cells | [81] |

| cardiotonic steroid (Digitoxin) | unknown | Depletion of SRSF3 and TRA2B in stable HEK293 expressing TAU dual-color reporter gene | [82, 83] |

| Protein phosphatase inhibitors (okadaic acid, tautomycin, microcystin-LR, sodium vanadate and pseudocantharidins) | PP1 and PP2A First and second steps of splicing | Ser/Thr protein phosphorylation required for both catalytic steps of splicing in vitro using AdML in HeLa nuclear extract | [84, 85] |

| Amiloride | unknown | Inhibition of SRSF1 phosphorylation and splicing of BCL-X, HIPK3 and RON/MISTR1 in Huh-7 cultured cells | [86] |

| N-palmitoyl-L-leucine | After complex A formation | The compound carbon chain length is important for splicing activity of AdML in HeLa nuclear cell extract | [61] |

Early splicing modulators were identified as FR901464, and its acetylated derivate spliceostatin A (SSA) [35–37]. SSA is a natural product extracted from Pseudomonas and was first described as possessing anti-tumor effects on several xenograft models harboring human and murine tumors [35–37]. Only later was it discovered to bind to and inhibit, the spliceosome component SF3B1 [38, 39]. In this way, it interferes with snRNA U2 binding to the branch point, destabilizing it, and preventing the transition of the spliceosome complex A to B [38–40]. This observation encouraged the exploitation of small molecule splicing modulators as cancer therapy drugs.

Other splicing modulators were subsequently extracted from different strains of bacteria, namely, Pladienolides from Streptomyces platensis [41–44] and GEX1, from Streptomyces sp. [45, 46], and both have the same mechanism of action as SSA [47, 48]. The fact that SF3B1 is the target of three different natural products extracted from diverse bacteria strains points to a shared mode of action. More recently, synthetic analogues of SSA, Meayamycin B (MAMB) [49] and Sudemycins [50], and the Pladienolide analogue E7107 [51] have been generated and shown to have similar anti-splicing properties as SSA (Table 1). Similarly, isoginkgetin is a natural component extracted from the leaves of M. glyptostroboides, which was initially described to have anti-cancer activity [52] and later found to be an inhibitor of pre-mRNA splicing [53].

Additional small molecule splicing inhibitors were identified in various high-throughput in vitro screens [54, 55]. Madrasin was isolated from a screen of PM5 pre-mRNA splicing [56] against a library of 71,504 small molecules and also shown to inhibit splicing of endogenous genes in both HeLa and HEK293 cells [57]. Furthermore, a high-throughput screen using a luciferase splicing reporter identified clotrimazole, flunarizine, and chlorhexidine [46, 58] as splicing modulators in cultured HeLa cells. Microarray analysis of cells treated with the three compounds revealed that AS of distinct sets of genes was affected, suggesting target specificity for each. The mechanism of action for chlorhexidine involves inhibition of Cdc2-like kinases (Clks) which phosphorylate the family of serine-arginine-rich (SR) protein splicing factors [58]. Using a splicing-dependent exon-junction complex immunoprecipitation (EJIPT) assay in a high-throughput screen, 1,4-naphthoquinones and 1,4-heterocyclic quinones were identified as splicing inhibitors [59]. As opposed to other known inhibitors blocking the first transesterification reaction, these two compounds were shown to block the second transesterification reaction by preventing intron lariat release and ligation of the two exons in vitro [59]. Tetrocarcin A, indole and naphthazarin were retrieved from an in vitro screen using a sensitive qPCR method to detect in vitro splicing. Each of the compounds was found to inhibit splicing at a different stage of spliceosome assembly with tetrocarcin A blocking the first splicing step, and indole and napthazarin, blocking the second step [60]. Tetrocarcin A and naphthazarin also inhibited spliceosome assembly in yeast, suggesting that their target is a universally conserved component of the spliceosome [60]. A similar screen using the same in vitro construct with a denaturing gel as readout, showed that the natural compound N-palmitoyl-L-leucine derived from the marine bacteria Streptomyces sp. was a splicing modulator [61]. Unlike most other splicing modulators, N-palmitoyl-L-leucine does not affect complex A of the spliceosome, but acts at a later stage of spliceosome assembly [61].

Another class of small molecules that appear to affect RNA processing via stalling of spliceosome assembly is a set of inhibitors of protein acetylation and deacetylation [62]. These molecules were tested for their effect on splicing following observations linking protein acetylation and RNA processing [63, 64]. Three small-molecule inhibitors of histone acetyltransferases (HATs), as well as three small-molecule inhibitors of histone deacetylases (HDACs), were found to block pre-mRNA splicing at intermediate steps of the splicing cycle and detected using mass-spectrometric analysis of affinity-purified stalled spliceosomes [62].

Selectivity of small molecule splicing modulators

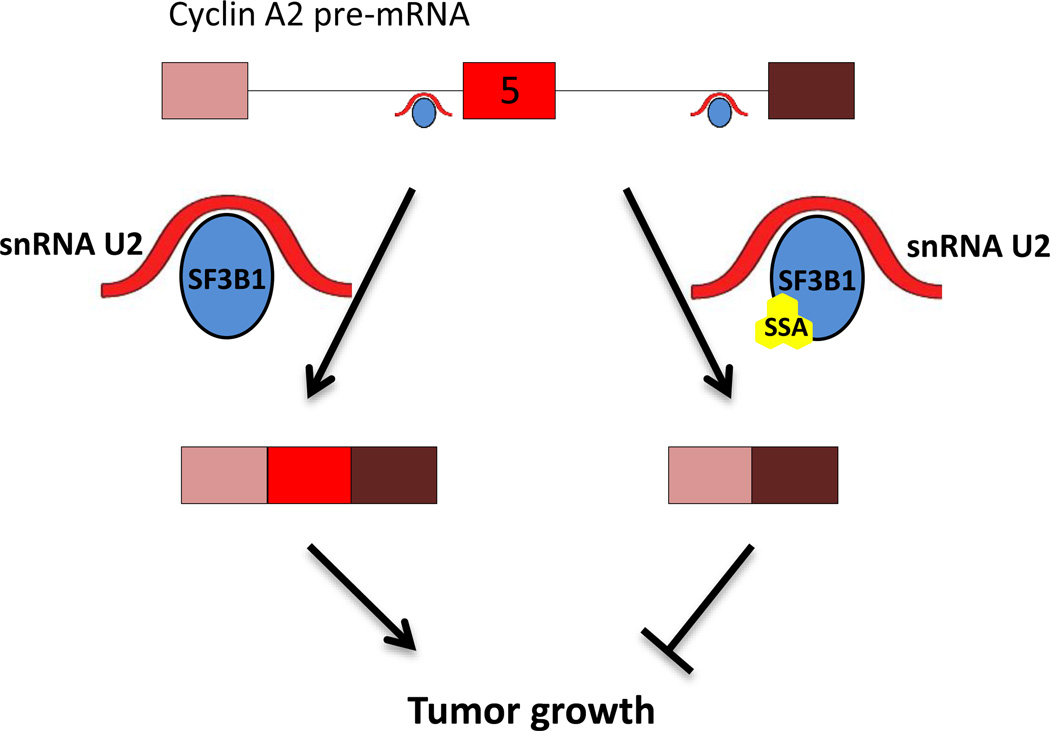

Since many splicing modulators appear to target the basal splicing machinery, one might expect the modulators to act as general pre-mRNA splicing inhibitors and affect splicing globally. However, several observations suggest a certain degree of specificity of action of several of the characterized splicing modulators. For example, in case of SSA, splicing-specific microarray analysis shows extensive effects on AS patterns of genes important for cell division, such as Cyclin A2 and Aurora A kinase (Fig. 2) [39]. Specific splicing isoforms of these genes may halt cell cycle progression and in this way, impede cancer growth. A similar AS pattern is observed upon silencing of the prime SSA target SF3B1 in HeLa cells [39]. How inhibition of SF3B1 leads to AS changes is unknown at present, but one supposition is that the affected genes share similarity at the 3’ splice site sequence that defines the base-pair binding characteristics of U2 snRNA [39]. Interestingly, mutations in the HEAT 5–9 repeats of SF3B1 have been found in patients with breast and pancreatic cancer and in uveal melanoma [65]. Splicing analysis in myelodysplastic syndrome cancer cells harboring SF3B1 mutations has shown that splicing is not broadly affected, but rather, that only some splicing events are disrupted [66–68]. RNA-seq analysis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, breast cancer and uveal melanoma tumor samples harboring SF3B1 mutations has also revealed a preference for cryptic 3’ splice site selection in a group of affected genes [69]. In addition, SF3B1 has also been reported to bind to exonic nucleosomes in a set of genes, allowing the possibility of gene-specific splicing regulation [70]. Rather than the result of global effects on splicing modulation, these findings point to a considerable degree of selectivity (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Small molecule splicing modulation specificity and function.

Despite targeting of generic splicing factors, small molecule modulators of splicing can have gene-specific effects. Rectangles represent exons and lines represent introns. Complex A of the spliceosome is represented here by U2 snRNA and SF3B1. U2 binds to the branch point and is stabilized by SF3B1. Small splicing modulator molecules bind SF3B1 and alter the splicing of cancer-relevant genes. In this specific example, the splicing modulator SSA binds SF3B1 to promote exon 5 skipping of Cyclin A2 [39]. Cyclin A2 plays a key role in cell cycle regulation and its expression is up-regulated in many types of cancer, including breast and liver [87, 88].

Another indication of the specificity of splicing modulators comes from the comparison of splicing events altered by the three compounds obtained from a single screen mentioned earlier [58], namely clotrimazole, flunarizine, and chlorhexidine. Microarray analysis to study the change in splicing following treatment with each of the compounds revealed however, that each compound affected a distinct group of splicing events [58]. This suggests that these compounds do not act as generic splicing inhibitors, but that different RNA substrates have distinct sensitivities to them. How this specificity is established is not known. Regardless, given the selective nature of some of these inhibitors, small molecule inhibitors may have potential as therapeutic agents.

The search for small molecule splicing modulators has been mostly empirical and the mechanisms of action are largely unknown. The finding that several of the characterized splicing modulators appear to target the U2-associated spicing factor SF3B1 points to a pivotal role of this factor in splicing modulation by small molecules. SF3B1 is part of the protein component of splicing complex A, in which the recognition of the branch-point consensus takes place. In a first step, U2 snRNA executes base-pairing to the branch-point in the upstream segment of the 3’ splice site (Fig. 2). The binding is then stabilized by SF3Ba and SF3Bb [2]. As part of the U2 snRNP complex, SF3B1 is involved in the recognition of the branch point consensus sequence required for proper usage of the upstream 5’ splice site, leading to joining of adjacent exons (Fig. 2). Binding of SSA to SF3B1 has been found to disrupt its interaction with pre-mRNA and consequently, to interrupt U2 snRNA branch point recognition [39]. In the absence of proper branch point recognition by U2 snRNA, an alternate branch point is used, which results in an altered splicing pattern [39]. In a similar fashion, E7107 has been found to bind SF3B1 and inhibit ATP-dependent RNA remodeling, thus exposing the branch point recognition region on U2 snRNA. Perturbing U2 snRNA recognition is thought to be the predominant mechanism of splicing modulation by E7107 [51]. The observed selectivity of these compounds for distinct genes and splicing events may be generated by the presence of distinct configurations of alternative branch points in individual genes.

Use of splicing modulators in cancer therapy

Although the precise mechanisms are not yet understood, several splicing modulators have been shown to be effective in cancer therapy.

The first splicing modulator described to have an anti-tumor effect was FR901464 [35–37]. Treatment of xenograft models harboring human and murine tumors for 4 days with FR901464 prolonged the life of mice carrying murine ascites tumors by 40% [35]. For solid tumors, treatment with FR901464 reduced tumor size by 80% [35]. However, the FR901464 analog diminished tumor size by only 20% [71]. In these cases, its analog MAMB was proposed to act by interfering with the splicing of the HPV16 anti-apoptotic E6 isoform and reducing the amount of MCL1L in HPV16-driven head and neck cancer [72]. In addition GEX1A/herboxidiene and Sudemycin D6 decreased tumor size by 80% and 50%, respectively [46, 73]. Similarly, Pladienolide B was effective in reducing xenograft tumors size by 60% [41]. The Pladienolide B synthetic analog, E7107, was tested in a phase 1 clinical trial with patients presenting different types of solid tumors, including colorectal, esophageal, pancreatic, gastric, renal and uterine, and was found to stabilize (or curb) tumor growth [74–76]. Pharmacodynamics analyses were encouraging as pre-mRNA splicing in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients was modulated, as demonstrated by increased intron retention based on microarray analysis [75]. A concern with splicing modulators, particularly globally acting ones, is toxicity. Indeed, at higher doses of E7107 (> 4.3mg/m2) in a clinical trial, patients suffered from diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, and myocardial infarction,, such that the trial was discontinued due to toxicity (in two cases there was vision loss) [74, 75]. Toxicity was also observed in xenograft experiments using FR901464, Pladienolide B, GEX1A and Sudemycin D6 in a dose dependent manner, and was manifested by mouse low weight or death before reaching the experimental end point [35, 41, 46, 73].

Toxicity may be avoided by the use of a lower dose of splicing modulators, albeit at the risk of reduced efficacy. However, lower doses of splicing modulators may be a particularly attractive and effective approach to cancers presenting molecular addiction to a weakly spliced isoform arising from non-canonical splicing motifs. An example of molecular addiction to a weak splicing isoform is the BRAF3–9 isoform in melanoma, conferring resistance to vemurafenib [12]. Characterization of the molecular mechanisms leading to a vemurafenib-resistant BRAF3–9 isoform suggested that weak splicing consensus sequences were being used to generate the BRAF isoform. Consistent with the notion that splicing modulators are most effective on weak splicing events, SSA and MAMB were effective in reducing BRAF3–9 production [12]. They also inhibited proliferation of vemurafenib-resistant cells and caused almost complete tumor-inhibition in xenograft models [12]. Importantly, tumor inhibition occurred without any obvious toxicity and splicing modulators did not affect control tumors lacking the BRAF(3–9) isoform. These observations show that targeting of a specific isoform that is weakly spliced allows the effective use of low doses of a splicing modulator with minimal toxic side effects. Furthermore, effective treatment using a low dose splicing modulator has recently been demonstrated for MYC-driven cancers [17]. The sensitivity in these cancers stems from the elevated production of total mRNA resulting from increased transcription by MYC [17] High levels of mRNA cause a burden on the spliceosome, so partial modulation of the spliceosome using low doses of Sudemycin D6 was sufficient to decrease lung tumor volume by half in a xenograft model [17]. These proof-of-principle results are encouraging and support the use of splicing modulators in cancer therapy.

Concluding Remarks

RNA splicing modulators are attractive, novel therapeutic agents in cancer. However, much work remains in order to demonstrate their clinical potential and usefulness. The molecular mechanism by which splicing modulators antagonize tumor growth is not clear and it will be important to characterize which are the specific targets and molecular mechanisms of action for any splicing modulators to be used in a clinical setting. A particularly attractive application of splicing modulators might be their use in tumors exhibiting molecular addiction to a non-canonically, weak spliced isoform, as this would allow the use of lower modulator concentrations, and possibly alleviate the toxicity that has been observed in clinical trials [75]. Efforts should be made to systematically identify the oncogenic drivers generated by weak splicing events. Other types of cancers that could be specifically treated by the use of low dose splicing modulators are the ones harboring (a) mutation(s) within speciific splicing factors serving as small molecule targets, such as SF3B1 [44], or tumors that are globally capable of increasing the splicing burden [17].

The exact splicing patterns in different types of cancers are yet to be rigorously characterized. The ongoing trend towards molecular analysis of patients during routine clinical treatment will dramatically increase the available information on splicing patterns and on how they relate to a patient’s health history. These datasets will be most valuable in deciphering the functional contribution of RNA splicing in oncogenesis. In-depth analysis of RNA splicing patterns may indeed reveal novel cancer drivers as well as provide mechanistic insight into these pathways.

One can envision that in the near (and hopeful) future, RNA isoform patterns of all cancer patients will be routinely characterized as part of Precision Medicine protocols (see Outstanding Questions). In addition, patients may be screened for somatic or germline mutations in their cellular splicing machinery. Considering the specific effects of individual splicing isoforms, RNA isoform fingerprinting from single patients bears great potential as a highly informative method to select personalized therapeutic interventions in cancer, especially if effective small molecule modulators of RNA splicing can be developed. Indeed, the first steps towards this promising therapeutic strategy have already begun.

Outstanding Questions.

What are the targets and modes of action of currently known chemical RNA splicing modulators?

How do splicing modulators targeting constitutive splicing factors generate gene-specific isoforms?

What are the different mechanisms by which chemical splicing modulators inhibit tumor growth?

Can the mapping of splicing factor mutations and RNA isoforms in individual patients inform treatment choices as part of a Precision Medicine approach?

Trends Box.

Alternatively spliced RNA isoforms and elevated RNA processing activity have been identified in different types of cancer, making RNA processing an attractive therapeutic target worth pursuing.

Several small molecule RNA splicing modulators have been identified as part of intensive ongoing drug screening approaches.

The observation of specificity of chemical splicing modulators for particular RNA isoforms has prompted the investigation of the mechanisms by which splicing specificity occurs.

Molecular addiction to weakly spliced isoforms is a particularly attractive target for the development of chemical splicing modulators in cancer therapy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Venter JC, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291(5507):1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wahl MC, Will CL, Luhrmann R. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell. 2009;136(4):701–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee Y, Rio DC. Mechanisms and Regulation of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:291–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graveley BR. Alternative splicing: increasing diversity in the proteomic world. Trends Genet. 2001;17(2):100–107. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ge Y, Porse BT. The functional consequences of intron retention: alternative splicing coupled to NMD as a regulator of gene expression. Bioessays. 2014;36(3):236–243. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grellscheid S, et al. Identification of evolutionarily conserved exons as regulated targets for the splicing activator tra2beta in development. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(12):e1002390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sveen A, et al. Aberrant RNA splicing in cancer; expression changes and driver mutations of splicing factor genes. Oncogene. 2015 doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takehara T, et al. Expression and role of Bcl-xL in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatology. 2001;34(1):55–61. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bingle CD, et al. Exon skipping in Mcl-1 results in a bcl-2 homology domain 3 only gene product that promotes cell death. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(29):22136–22146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909572199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todaro M, et al. CD44v6 is a marker of constitutive and reprogrammed cancer stem cells driving colon cancer metastasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(3):342–356. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng S, Kim H, Verhaak RG. Silent mutations make some noise. Cell. 2014;156(6):1129–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salton M, et al. Inhibition of vemurafenib-resistant melanoma by interference with pre-mRNA splicing. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7103. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karni R, et al. The gene encoding the splicing factor SF2/ASF is a proto-oncogene. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(3):185–193. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shilo A, et al. Splicing factor hnRNP A2 activates the Ras-MAPK-ERK pathway by controlling A-Raf splicing in hepatocellular carcinoma development. RNA. 2014;20(4):505–515. doi: 10.1261/rna.042259.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh CM, et al. MYC regulates the core pre-mRNA splicing machinery as an essential step in lymphomagenesis. Nature. 2015;523(7558):96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature14351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David CJ, et al. HnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature. 2010;463(7279):364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature08697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu TY, et al. The spliceosome is a therapeutic vulnerability in MYC-driven cancer. Nature. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nature14985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kole R, Krainer AR, Altman S. RNA therapeutics: beyond RNA interference and antisense oligonucleotides. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(2):125–140. doi: 10.1038/nrd3625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boise LH, et al. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74(4):597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xerri L, et al. BCL-X and the apoptotic machinery of lymphoma cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;28(5–6):451–458. doi: 10.3109/10428199809058352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bae J, et al. MCL-1S, a splicing variant of the antiapoptotic BCL-2 family member MCL-1, encodes a proapoptotic protein possessing only the BH3 domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(33):25255–25261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909826199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shieh JJ, et al. Modification of alternative splicing of Mcl-1 pre-mRNA using antisense morpholino oligonucleotides induces apoptosis in basal cell carcinoma cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(10):2497–2506. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orian-Rousseau V. CD44, a therapeutic target for metastasising tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(7):1271–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orian-Rousseau V. CD44 Acts as a Signaling Platform Controlling Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:154. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng C, Yaffe MB, Sharp PA. A positive feedback loop couples Ras activation and CD44 alternative splicing. Genes Dev. 2006;20(13):1715–1720. doi: 10.1101/gad.1430906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann M, et al. CD44 splice variants confer metastatic behavior in rats: homologous sequences are expressed in human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1991;51(19):5292–5297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunthert U, et al. A new variant of glycoprotein CD44 confers metastatic potential to rat carcinoma cells. Cell. 1991;65(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90403-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi J, et al. Correlation of CD44v6 expression with ovarian cancer progression and recurrence. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Ben-Hur V, et al. S6K1 alternative splicing modulates its oncogenic activity and regulates mTORC1. Cell Rep. 2013;3(1):103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salton M, Voss TC, Misteli T. Identification by high-throughput imaging of the histone methyltransferase EHMT2 as an epigenetic regulator of VEGFA alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(22):13662–13673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawford NP, et al. Bromodomain 4 activation predicts breast cancer survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(17):6380–6385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710331105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi J. Bromodomain and extraterminal domain inhibitors (BETi) for cancer therapy: chemical modulation of chromatin structure. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(12):a018663. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alsarraj J, et al. Deletion of the proline-rich region of the murine metastasis susceptibility gene Brd4 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition- and stem cell-like conversion. Cancer Res. 2011;71(8):3121–3131. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poulikakos PI, et al. RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E) Nature. 2011;480(7377):387–390. doi: 10.1038/nature10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakajima H, et al. New antitumor substances, FR901463, FR901464 and FR901465. II. Activities against experimental tumors in mice and mechanism of action. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1996;49(12):1204–1211. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakajima H, et al. New antitumor substances, FR901463, FR901464 and FR901465. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological activities. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1996;49(12):1196–1203. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakajima H, et al. New antitumor substances, FR901463, FR901464 and FR901465. III. Structures of FR901463, FR901464 and FR901465. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1997;50(1):96–99. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaida D, et al. Spliceostatin A targets SF3b and inhibits both splicing and nuclear retention of pre-mRNA. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(9):576–583. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corrionero A, Minana B, Valcarcel J. Reduced fidelity of branch point recognition and alternative splicing induced by the anti-tumor drug spliceostatin A. Genes Dev. 2011;25(5):445–459. doi: 10.1101/gad.2014311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roybal GA, Jurica MS. Spliceostatin A inhibits spliceosome assembly subsequent to prespliceosome formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(19):6664–6672. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizui Y, et al. Pladienolides, new substances from culture of Streptomyces platensis Mer-11107. III. In vitro and in vivo antitumor activities. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2004;57(3):188–196. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakai T, et al. Pladienolides, new substances from culture of Streptomyces platensis Mer-11107. II. Physico-chemical properties and structure elucidation. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2004;57(3):180–187. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakai T, et al. Pladienolides, new substances from culture of Streptomyces platensis Mer-11107. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and screening. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2004;57(3):173–179. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arai K, et al. Total synthesis of 6-deoxypladienolide D and Assessment of Splicing Inhibitory Activity in a Mutant SF3B1 cancer cell line. Org Lett. 2014;16(21):5560–5563. doi: 10.1021/ol502556c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakai Y, et al. GEX1 compounds, novel antitumor antibiotics related to herboxidiene, produced by Streptomyces sp. II. The effects on cell cycle progression and gene expression. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2002;55(10):863–872. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.55.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakai Y, et al. GEX1 compounds, novel antitumor antibiotics related to herboxidiene, produced by Streptomyces sp. I. Taxonomy, production, isolation, physicochemical properties and biological activities. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2002;55(10):855–862. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.55.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hasegawa M, et al. Identification of SAP155 as the target of GEX1A (Herboxidiene), an antitumor natural product. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6(3):229–233. doi: 10.1021/cb100248e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kotake Y, et al. Splicing factor SF3b as a target of the antitumor natural product pladienolide. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(9):570–575. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Albert BJ, et al. Meayamycin inhibits pre-messenger RNA splicing and exhibits picomolar activity against multidrug-resistant cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(8):2308–2318. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan L, et al. Sudemycins, novel small molecule analogues of FR901464, induce alternative gene splicing. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6(6):582–589. doi: 10.1021/cb100356k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Folco EG, Coil KE, Reed R. The anti-tumor drug E7107 reveals an essential role for SF3b in remodeling U2 snRNP to expose the branch point-binding region. Genes Dev. 2011;25(5):440–444. doi: 10.1101/gad.2009411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoon SO, et al. Isoginkgetin inhibits tumor cell invasion by regulating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(11):2666–2675. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Brien K, et al. The biflavonoid isoginkgetin is a general inhibitor of Pre-mRNA splicing. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(48):33147–33154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805556200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tazi J, Durand S, Jeanteur P. The spliceosome: a novel multi-faceted target for therapy. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30(8):469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonnal S, Vigevani L, Valcarcel J. The spliceosome as a target of novel antitumour drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(11):847–859. doi: 10.1038/nrd3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samatov TR, et al. Psoromic acid derivatives: a new family of small-molecule pre-mRNA splicing inhibitors discovered by a stage-specific high-throughput in vitro splicing assay. Chem bio chem. 2012;13(5):640–644. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pawellek A, et al. Identification of small molecule inhibitors of pre-mRNA splicing. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(50):34683–34698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.590976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Younis I, et al. Rapid-response splicing reporter screens identify differential regulators of constitutive and alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(7):1718–1728. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01301-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berg MG, et al. A quantitative high-throughput in vitro splicing assay identifies inhibitors of spliceosome catalysis. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(7):1271–1283. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05788-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Effenberger KA, et al. A high-throughput splicing assay identifies new classes of inhibitors of human and yeast spliceosomes. J Biomol Screen. 2013;18(9):1110–1120. doi: 10.1177/1087057113493117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Effenberger KA, et al. The Natural Product N-palmitoyl-L-leucine Selectively Inhibits Late Assembly of Human Spliceosomes. J Biol Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.673210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuhn AN, et al. Stalling of spliceosome assembly at distinct stages by small-molecule inhibitors of protein acetylation and deacetylation. RNA. 2009;15(1):153–175. doi: 10.1261/rna.1332609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martinez E, et al. Human STAGA complex is a chromatin-acetylating transcription coactivator that interacts with pre-mRNA splicing and DNA damage-binding factors in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(20):6782–6795. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6782-6795.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hnilicova J, et al. Histone deacetylase activity modulates alternative splicing. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoshida K, Ogawa S. Splicing factor mutations and cancer. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2014;5(4):445–459. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gentien D, et al. A common alternative splicing signature is associated with SF3B1 mutations in malignancies from different cell lineages. Leukemia. 2014;28(6):1355–1357. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Visconte V, et al. Distinct iron architecture in SF3B1-mutant myelodysplastic syndrome patients is linked to an SLC25A37 splice variant with a retained intron. Leukemia. 2015;29(1):188–195. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dolatshad H, et al. Disruption of SF3B1 results in deregulated expression and splicing of key genes and pathways in myelodysplastic syndrome hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Leukemia. 2015;29(5):1092–1103. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.DeBoever C, et al. Transcriptome sequencing reveals potential mechanism of cryptic 3' splice site selection in SF3B1-mutated cancers. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11(3):e1004105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kfir N, et al. SF3B1 association with chromatin determines splicing outcomes. Cell Rep. 2015;11(4):618–629. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Osman S, et al. Evaluation of FR901464 analogues in vitro and in vivo. Med chem comm. 2011;2(1):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gao Y, et al. Regulation of HPV16 E6 and MCL1 by SF3B1 inhibitor in head and neck cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6098. doi: 10.1038/srep06098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lagisetti C, et al. Optimization of antitumor modulators of pre-mRNA splicing. J Med Chem. 2013;56(24):10033–10044. doi: 10.1021/jm401370h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eskens FA, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the first-in-class spliceosome inhibitor E7107 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(22):6296–6304. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hong DS, et al. A phase I, open-label, single-arm, dose-escalation study of E7107, a precursor messenger ribonucleic acid (pre-mRNA) splicesome inhibitor administered intravenously on days 1 and 8 every 21 days to patients with solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32(3):436–444. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-0046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dehm SM. Test-firing ammunition for spliceosome inhibition in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(22):6064–6066. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sato M, et al. High antitumor activity of pladienolide B and its derivative in gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(1):110–116. doi: 10.1111/cas.12317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pilch B, et al. Specific inhibition of serine- and arginine-rich splicing factors phosphorylation, spliceosome assembly, and splicing by the antitumor drug NB-506. Cancer Res. 2001;61(18):6876–6884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ajuh P, Lamond AI. Identification of peptide inhibitors of pre-mRNA splicing derived from the essential interaction domains of CDC5L and PLRG1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(21):6104–6116. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Muraki M, et al. Manipulation of alternative splicing by a newly developed inhibitor of Clks. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(23):24246–24254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Soret J, et al. Selective modification of alternative splicing by indole derivatives that target serine-arginine-rich protein splicing factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(24):8764–8769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409829102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Anderson ES, et al. The cardiotonic steroid digitoxin regulates alternative splicing through depletion of the splicing factors SRSF3 and TRA2B. RNA. 2012;18(5):1041–1049. doi: 10.1261/rna.032912.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stoilov P, et al. A high-throughput screening strategy identifies cardiotonic steroids as alternative splicing modulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(32):11218–11223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801661105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mermoud JE, Cohen P, Lamond AI. Ser/Thr-specific protein phosphatases are required for both catalytic steps of pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20(20):5263–5269. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.20.5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang Z, et al. Synthesis and characterization of pseudocantharidins, novel phosphatase modulators that promote the inclusion of exon 7 into the SMN (survival of motoneuron) pre-mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(12):10126–10136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.183970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chang JG, et al. Small molecule amiloride modulates oncogenic RNA alternative splicing to devitalize human cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e18643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bukholm IR, Bukholm G, Nesland JM. Over-expression of cyclin A is highly associated with early relapse and reduced survival in patients with primary breast carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2001;93(2):283–287. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ohashi R, et al. Enhanced expression of cyclin E and cyclin A in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(1B):657–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]