Abstract

Background

Symptoms arising from disease or treatment are subjective experiences. Insight into pediatric oncology treatment side effects or symptoms is ideally obtained from direct inquiry to the ill child. A concept elicitation phase in a patient-reported outcome instrument design provides opportunity to elicit children's voices to shape cancer symptom selection and terminology.

Methods

Symptom data were collected from 96 children with cancer, ages 7-20 years undergoing oncologic treatment at seven pediatric oncology sites in the United States and Canada through semi-structured, one-on-one, voice-recorded interviews.

Results

The mean number of symptoms reported per child over the prior seven days was 1.49 (range 0-7, median 1, SD 1.56). The most common symptoms across all age groups were: feeling tired or fatigue, nausea or vomiting, aches or pains, and weakness. There was not a statistically significant correlation between self-reported wellness and the number of symptoms reported (r= -0.156, n = 65, p = 0.215) or the number of symptoms reported based on age group or diagnosis type. Forty participants reported experiencing a change in their body in the past week with one-third of these changes unanticipated. Only by directly asking about feelings were emotional symptoms revealed, as 90.6% of interviewees who discussed feelings (n=48/53) did so only in the context of direct questioning on feelings. Adolescents were more likely than younger children to discuss feelings as part of the interview.

Conclusion(s)

Concept elicitation, from children and adolescents, has the potential to enable researchers to develop age-appropriate, accurately representative patient-reported outcome measures.

Keywords: Pediatric oncology, patient reported outcomes, adverse events, symptoms, patient communication, instrument development, qualitative research

Introduction

Children and adolescents undergoing cancer-directed treatment have the potential to provide the most insightful perspective for accurate portrayal of how they “feel and function”1 while on therapy, particularly in regard to symptom burden.2 Pediatric patient-reported outcomes (PRO) involve the report of health symptoms directly from the patient's perspective without filtering from proxies, researchers, or clinicians.3 As symptoms during oncology treatment are subjective experiences known best by the patient,4 insight into these symptoms is ideally obtained from PRO instruments. Despite recognized importance of PROs, a study team recently updated a systematic review of the use of symptom assessment scales in pediatric oncology, finding that only three out of over 500 papers published between 2012-2014 utilized child self-reports in the setting of pediatric cancer.5

When children and adolescents are given opportunity to discuss their health status and experiences of health, they serve as effective and reliable experiential symptom content experts,6-8 including children and adolescents with cancer.5, 9, 10 Adult oncology clinicians tend to under-report the quantity and severity of symptoms compared to what their patients report.11-13 Discrepancies between parent and child symptom reporting, particularly for non-observable symptoms,14-17 has compelled researchers and professional organizations to surmise that while proxy symptom report offers family insight, the gold standard in pediatric symptom reporting should be the child directly reporting.18 The FDA has recommended use of pediatric PRO instruments, rather than proxy instruments, to inform regulatory decisions and for use in medical labeling.3 The National Quality Forum has called for inclusion of children in PRO investigation.19 The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR)20 has called for pediatric PRO development, assessment, and implementation. The Institute of Medicine's six dimensions of patient-centeredness have been linked to meaningful investment in PROs for cancer patients of all ages.21

To ensure that a pediatric cancer PRO instrument is comprehensive and meaningful to the target population, children and adolescents with cancer should serve as symptom content experts. This paper presents the findings from semi-structured concept elicitation interviews with 96 children and adolescents ages 7 to 20 years old undergoing treatment for cancer.

Objectives

The purpose of the concept elicitation phase of the Patient-Reported Outcome version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) project was to elicit patient voice to identify meaningful symptoms and to shape the pediatric PRO-CTCAE instrument's accuracy, developmental-applicability, and terminology.

The aims of the concept elicitation phase were threefold, with each aim driven by a consideration for possible clinical application. The first aim was to quantify and categorize the prevalence of symptoms by stratified age group and to capture the terminology used by each age group prior to introduction of symptom vocabulary. The second aim was to compare reported body changes to any reported surprises in body changes (symptoms that the participant had not anticipated). The third aim was to analyze the effectiveness of asking directly about feelings, with the intent of determining if emotions might be missed by not specifically asking about feelings as part of symptom inquiry.

Methods

This prospective qualitative study of concept elicitation was integrated within the National Cancer Institute funded Creating and Validating Child Adverse Event Reporting in Oncology Trials Grant (NIH ID R01CA175759). The study had institutional review board approval at seven geographically diverse pediatric oncology treatment sites: Children National Health System, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute / Boston Children's Hospital, The Hospital for Sick Children, Palmetto Health, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). The primary aim of the overall study is to develop and validate pediatric PRO-CTCAE measures for use in clinical trials and practice. The prospective qualitative phase substudy included a one-timepoint, voice-recorded interview with English-speaking children and adolescents with cancer ages 7-20 years undergoing chemotherapy. Participants were identified by chart reviews and primary team referrals. In order to be eligible for the study, the participant on cancer-directed therapy had to be between the ages 7-20 years at time of enrollment. Both child and caregiver-proxy had to be English-speaking in order to participate in this round of interviews. Participants were selected by purposive and not consecutive sampling. After written consent was obtained from the proxy and written assent obtained from the child, each child was interviewed in a private hospital room or conference room with the goal of interview occurring separate from the caregiver-proxy interview to minimize biasing child report.

To standardize procedures and ensure consistency in interview format across sites, interviewers attended a one-day concept elicitation and cognitive interview trainee workshop at UNC. After extensive piloting, final interview questions for the concept elicitation phase consisted of the following sequence: “How has your body felt over the past seven days?” “Have you had any changes in your body?” “Have you had any changes in your body that maybe surprised you or that you didn't expect?” “How have your feelings been in the past seven days?” Questions targeted a seven-day recall period, as has been used in prior pediatric cancer studies.18 These concept elicitation questions were asked at the beginning of the interviews before any PRO items were shown to them. This was done for two reasons: to remove any possibility that the PRO instrument would inform their answers, and to hear the child's own description of their symptom experiences in their own words. Interview data were summarized and entered into the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)22 software program by each interviewer independently. Interview recordings were uploaded into REDCap and transcribed verbatim by a medical transcriptionist team. A team of six investigators, who were engaged in data entry quality checks, decided to utilize raw transcript reports for accurate data extraction in the concept elicitation phase due to the goal of accessing unfiltered child and adolescent voices. A minimum of two blinded study team members extracted each data point from original transcripts. For the ten missing transcripts (due to voice recorded error or child preference not to be recorded), the interviewer's REDCap data entry was utilized.

For this qualitative study, the primary mode of analysis was qualitative investigation into phrases utilized and symptoms reported. Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic characteristics and symptom prevalence. Spearman's correlation was utilized to analyze continuous variables. Cross-tabulations and Kruskal-Wallis tests were utilized to analyze categorical variables. Variables potentially related to qualitative symptom reporting (age group and cancer type) were a priori determined based on the expert opinion of four pediatric oncologists, three advanced practice nurses, and three researchers and review of prior symptom burden literature. Transcripts were reviewed for wellness words spoken by the interviewee in response to the question “How has your body felt?” with these “good, okay, bad”-phrase words converted into a pre-determined “wellness scale” using Likert-numbers from 1 (very bad) to 9 (very good). Age groups (7-8, 9-12, 13-15, 16-20 year olds) were predetermined based on similarities in cognitive capacities and abilities as postulated in developmental science theory.23, 24 All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (IBM SPSS, Version 23).

Results

Ninety-six participants enrolled in the study between February to November 2014. Child or proxy refusal rate was 24.4% (n=31 refusals/127 approached). For the six sites that allowed data collection on refusal cases, there were no statistically significant differences observed in demographic or diagnostic characteristics between declining participants and consenting participants. Median concept elicitation interview time was 50 minutes. Participants' demographic and clinical data are provided as Table 1.

Table 1. Medical and demographic characteristics of participants.

| Characteristics | n=96 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 40 (41.7%) | |

| Female | 56 (58.3%) | |

| Age Category | ||

| 7-8 years | 20 (20.8%) | |

| 9-12 years | 25 (26.0%) | |

| 13-15 years | 24 (25.0%) | |

| 16-20 years | 27 (28.1%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 51 (53%) | |

| Black | 19 (19.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 16 (16.7%) | |

| Asian | 5 (5.2%) | |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Other | 3 (3.1%) | |

| Diagnostic Category | ||

Leukemia/Lymphoma

|

59 (61.5%) | |

| Solid Tumor | 34 (35.4%) | |

| Neuro-Oncology | 3 (3.1%) | |

| Documented Relapse Status | ||

| Initial Diagnosis | 84 (87.5%) | |

| Relapse | 12 (12.5%) | |

| Treatment Location | ||

| Sick Children | 21 (21.9%) | |

| St Jude | 18 (18.8%) | |

| Children's Hospital Los Angeles | 16 (16.7%) | |

| Childrens National | 15 (15.6%) | |

| Palmetto Health | 9 (9.4%) | |

| University of North Carolina | 9 (9.4%) | |

| Dana Farber / Boston Children's | 8 (8.3%) | |

Aim 1 – Symptom Prevalence and Self-Reported Wellness

The mean number of symptoms (in the past 7 days) reported per patient with a first diagnosis of cancer (n=84/96) was 1.49 symptoms (range 0-7 symptoms per person, SD = 1.56 symptoms) and the mean number of symptoms per patient with a relapsed cancer (n=12/96) was 1.75 (range 0-5 symptoms per person, SD 1.36 symptoms). Of the twelve participants with a relapsed cancer, 2 did not report a symptom in their interview (17%). One third of all 96 participants did not report a symptom in their interviews. Symptom prevalence ranged from 29.2% for “feeling tired or fatigued” to 1% for “difficulty with sleep”, “incontinence”, “swollen gums”, “change in hearing”, and “racing heart.” With a reported prevalence >10%, the most common symptoms across all age groups were: feeling tired or fatigue, nausea or vomiting, aches or pains, and weakness (Table 2).

Table 2. Symptom prevalence report for all-ages.

| Symptom | Number of interviewees reporting symptom (n=96) | Percent of total interviewees reporting symptom (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No symptom | 32 | 33.3 |

| Tired or fatigue | 28 | 29.2 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 17 | 17.7 |

| Aches or pains | 12 | 12.5 |

| Weakness | 11 | 11.5 |

| Weight change | 9 | 9.4 |

| Appetite change | 8 | 8.3 |

| Headache | 7 | 7.3 |

| Skin change | 6 | 6.3 |

| Stomach discomfort | 5 | 5.2 |

| Mucositis/sore throat | 5 | 5.2 |

| Alopecia | 5 | 5.2 |

| Neuropathy | 4 | 4.2 |

| Difficulty ambulating | 4 | 4.2 |

| Energy change or mood change | 4 | 4.2 |

| Temperature change | 4 | 4.2 |

| Pruritis | 3 | 3.1 |

| Pulmonary symptom | 3 | 3.1 |

| Dizzy or lightheaded | 3 | 3.1 |

| Coagulation (bleed/bruise) | 2 | 2.1 |

| Difficulty with sleep | 1 | 1 |

| Incontinence | 1 | 1 |

| Swollen gums | 1 | 1 |

| Change in hearing | 1 | 1 |

| Cardiac symptom | 1 | 1 |

Qualitative interview findings included story-sharing descriptions more often in younger ages (“just wanted to sleep for a whole year” to describe feeling tired or “couldn't eat food” to describe anorexia or “flashes of cold” to describe chills). Older age participants tended to depict cause of symptoms as well as description of symptoms (“anemia” when describing reason for fatigue or naming chemotherapy culprits when describing neuropathy). Frequency of symptoms reported and comprehensive terminology used per age group are available as Supplemental Material 1. There was no significant difference in number of symptoms reported based on age group or diagnosis type. Length of treatment ranged from 1 week to 90 months (mean 10.7 months, median 5 months, SD 14.9 months). There was a weak, negative correlation between length of treatment and number of symptoms reported which was found to not be statistically significant in patients undergoing treatment for initial cancer (r= -0.129, n = 84, p = 0.241) and in patients undergoing treatment for relapsed cancer (r= -0.392, n = 12, p = 0.207); suggesting there was not an association between length of treatment and number of symptoms reported.

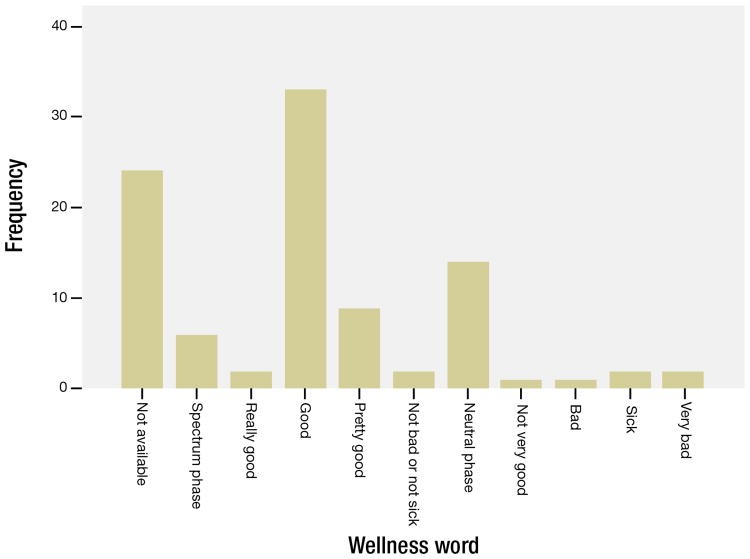

Of the 72/96 interviewees who utilized a wellness word in response to the question on how their body has felt, n=44/72 (61.1%) utilized “pretty good”, “good”, or “really good” terminology; n=16/72 (22.2%) utilizing neutral phrases such as “okay”, “functional”, “normal”; n= 6/72 (8.3%) utilized “sick”, “bad”, or “very bad” terminology; while n=6/72 (8.3%) sharing spectrum phrases such as “better with time” or “sick but now recovered” (Figure 1). There was a weak, negative, not statistically significant correlation between self-reported wellness and the number of symptoms reported (r= -0.156, n = 65, p = 0.215).

Figure 1. Frequency table depicting self-described participant wellness categories.

Aim 2 - Body Changes as Expected and Surprised

Four participants were not asked about body changes due to interview interruption or interviewer decision to skip this question. Of the 92 total interviewees asked about body changes experienced in the past seven days, n=52/92 (56.5%) reported no change. Of the 40/92 participants who experienced a change, n=31 were negative changes and n=9 were positive changes such as hair growing back sooner than anticipated, lymph nodes shrinking, or breathing easier.

Of the 78 interviewees then asked the optional follow-up question of whether they were surprised by these reported body changes, n=49/78 were not surprised (62.8%) while n=24/78 (30.8%) were surprised by a body change (Table 3). Skin changes (rash, peeling, eczema flare, and stretch marks) were the body change most associated with surprise. Five of these 78 interviewees (6.4%) reported although they were surprised by a body change, they had been warned of this potential occurrence and readily associated this warning with a medication side effect: “aches” from leukocyte growth factor injections, “puffiness” from steroids, “red feet” and “peeling palms” from cytarabine, and “dark nails” from “some chemotherapy”.

Table 3. Body changes reported as a surprise symptom.

| Unanticipated body change (n=15 changes, n=24 respondents) | Number of times body change was reported (more than one body change possible per respondent) |

|---|---|

| Skin change | 6 |

| Aches or pains | 5 |

| Difficulty ambulating | 2 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 2 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 |

| Hair change | 2 |

| Headache | 1 |

| Mucositis/sore throat | 1 |

| Pruritis | 1 |

| Pulmonary symptom | 1 |

| Allergic reaction | 1 |

| Edema – circle face | 1 |

| Infection of central line | 1 |

| Lymph node change | 1 |

| Nail change | 1 |

Aim 3 – Feelings and Emotions

Fifty-three out of 96 total interviewees (55.2%) discussed feelings or emotions at some point during the interview. These interviewees most frequently discussed feelings only when asked, “How have your feelings been?” (n=48/53; meaning 90.6% of those who discussed feelings did so only in the context of being directly asked about feelings). Summary of vocabulary used to depict emotions in response to direct feelings inquiry is available as Table 4. Few children or adolescents discussed feelings when asked how their body felt (n=6/53), and even fewer discussed feelings when asked about additional symptoms (n=3/53), or when asked about health problems not listed in the questionnaire (n=3/53). Supplemental Material 2 provides summary of feeling responses using interviewee terminology.

Table 4. Responses to “How have your feelings been?”*.

| Positive feelings (n=22 respondents) | Negative Feelings (n=30 respondents) | Neutral feelings (n=13 respondents) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Includes all feelings mentioned by n=48 participants who were directly asked, “How have your feelings been?”, during the interview Some participants mentioned a combination of feelings or more than one feeling in his/her response.

Fewer younger than older participants reported feelings or emotions. Of 7-8 year olds, 25% reported feelings (5/20); of 9-12 year olds, 52% reported feelings (13/25); of 13-15 year olds, 71% reported feelings (17/24); and of 16-20 year olds, 67% reported feelings (18/27).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that children and adolescents with cancer are able to self-report clinically relevant physical and emotional concerns according to their subjective experience. This population would likely, however, benefit from additional focused questions regarding symptoms and feelings. Content validity for symptom description “is primarily established through qualitative research that includes direct input from the target population.”20 Thus, content expert empowerment begins by engaging in concept elicitation through semi-structured qualitative interviews.20 Prioritizing qualitative methodology allows the target population to state the symptom impact prior to introduction of the study team's predetermined symptom prioritization or terminology.25 As the goal of PRO inquiry is to understand and evaluate impact of disease and treatment, qualitative methodology serves as an essential foundation for PRO instrument design. These interviews enabled the study team to identify, analyze, and report not only symptom prevalence but also the vocabulary these children use to describe their symptoms associated with both illness and treatment for incorporation into the PRO instrument design. Providing children an opportunity to share their chosen words for various symptoms enabled the study team to adapt the pediatric PRO-CTCAE instruments to terms more readily comprehensible to children and adolescents. The data confirm the presence of burdensome symptoms as described by interviewees, although the result of one-third of interviewees not reporting symptoms was a lower prevalence than prior questionnaire-based investigations have reported in children and adolescents undergoing oncologic treatment.5, 26 The lower prevalence may be due to limited recall without the reminder of questionnaire cues or may reflect the child not wanting to burden the medical team with symptom reporting. The lower prevalence may hint that pediatric oncology patients prefer not to think of adverse events and so they may not be carefully tracking symptoms unless they are asked. Or, patients may tend to focus on the most burdensome or troublesome symptoms and thus may not be including the complete symptom experience when qualitatively reporting. The difference in prevalence warrants further research into use of mixed-method PRO approaches (combined questionnaire and open-ended interviews) to evaluate and compare the content pooled by each approach. The real bottom line does appear to be the need for care teams to ask about symptoms directly of each patient and to explore the child's response. The low number of symptoms reported indicates that inquiring will not require an inordinate amount of clinical time.

Members of the study team had previously queried pediatric oncology clinicians, with direct experience treating children and adolescents with cancer, on important observable symptoms for pediatric PRO-CTCAE instrument inclusion.27 Of the 16 core CTCAE items from this initial clinicians survey (Supplemental Material 3), appetite increase and swollen gums were the only two new symptoms raised by concept elicitation phase of the patient interviews which were not on the clinicians' symptom item list. Two items that had been prioritized by clinicians in the PRO-CTCAE core symptom list were not mentioned in the pediatric concept elicitation interviews: constipation and diarrhea. Interestingly, two pediatric interviewees later asked if bowel conversations were polite or socially acceptable to discuss when the core items were reviewed after concept elicitation, lending consideration to whether participants were embarrassed to mention these symptoms upfront in qualitative interviews.

The overarching clinical implication of this study is the privilege and responsibility of utilizing direct patient report for clinical adverse event and symptom reporting. In considering clinical implications for each of the individual aims, the snapshot of current symptom profiles emphasized by patients across sites as offered by Aim 1 data summary lends to prioritization of supportive care opportunities with scale-up of pharmacologic, non-pharmacologic, and complementary interventions for the most prevalent or burdensome symptoms. Aim 1 data analysis revealed that high occurrence of symptoms does not translate into ready self-report of increased personal distress, reminding clinicians to not assume “good” in response to “how are you doing?” translates into an absence of symptom burden. These findings suggest a deeper probe into the child's experienced symptoms are needed as children may respond “good” to be a socially-conditioned response or to put on a brave front with dealing with their cancer. This also points to the need to have a PRO instrument like PRO-CTCAE to directly ask children their experiences with specific symptoms.

The Aim 2 finding that one third of interviewees were surprised by ‘body changes’, suggests potential opportunity to increase symptom education and anticipatory guidance. Reasons for this surprise may be due to the participant's optimism that he or she would not personally experience the expected toxicity, or the participant did not recall having been warned of the toxicity, or the side effect had not been discussed. However, these reasons cannot be inferred from the current data.

The Aim 3 finding that 90.6% of interviewees who discussed emotions (n=48/53) did so only when asked directly about feelings emphasizes the importance of providers inquiring specifically about feelings to prevent missing critical emotional reporting (such as, depression, anxiety, anger), particularly for participants aged 13-20 years who attributed 66% of the feelings responses (35/53). The fact that the interviewees did not discuss feelings when asked about their body wellness may imply this population would be more inclined to respond to psychological wellness questions separate from physical wellness questions. In a study conducted in adults receiving palliative chemotherapy, all patients wanted to discuss their physical symptoms and physical functioning and were also willing to address their emotional functioning and daily activities.28 However, one quarter of the patients were only willing to discuss these latter two issues at the initiative of their physician.28 In our current study, the three adolescents which expressed feelings only after the final question of “any health problems we forgot to ask?” demonstrates that older adolescents may benefit from established conversational trust prior to delving into immediate discussion on feelings as part of psychosocial symptom experiences.

The low number of neuro-oncology participants represents a study limitation, particularly as this population has been noted to have higher symptom burden.5 Included diagnoses were otherwise consistent with North American pediatric and adolescent cancer type statistics.29 A second limitation of the study included possible selection bias, as children with illness severity or language or cognitive functioning impairment may have been excluded due to inability to participate in interviews. The time period of seven days may have led the respondent to narrow his or her scope of recalled experiences. A further limitation in this study is generalizability since the sampling was purposive and not consecutive. By prioritizing interviewing pediatric participants separate from proxies, this study was strengthened by minimizing proxy influence on the child report. By interviewing participants prior to introducing them to the wording of the written PRO-CTCAE instrument draft, this study minimized biasing the participants' vocabulary choices. Finally, this study reported solely on English speaking children. Further data has been collected from children who preferred to conduct the interview in Spanish; these results are planned to be reported in a future publication.

Further work is warranted to edit the next round of interviews, particularly to adapt the feelings question into language more conducive to younger child. Our study team is now pursuing a second phase of cognitive interviewing to further explore terminology for adverse events and wording of symptoms to be certain that these items are accurately interpreted into child-friendly and child meaningful words.

Conclusion

In designing meaningful and rigorous metrics for PRO instruments in the pediatric and adolescent oncology patient population, clinicians and researchers should begin with patient voice. This would reduce the risk of missing symptoms that children or adolescents with cancer are actually experiencing. Systematic symptom inquiry may best be initiated with open-ended questions to enable children to provide personally relevant prioritization of symptom burden for best practice adverse event reporting. Providers should inquire specifically about feelings to prevent missing critical emotional symptomatology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Clinical and Translational Research Center grant support (1UL1TR001111) from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. Funding provided through Grant 1R01CA175759-01 “Creating and Validating Child Adverse Event Reporting in Oncology Trials”.

Footnotes

COI: No known conflict of interest disclosures from any authors.

References

- 1.Basch E, Bennett AV. Patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials of rare diseases. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 3):S801–803. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2892-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeh CH, Wang CH, Chiang YC, Lin L, Chien LC. Assessment of symptoms reported by 10- to 18-year-old cancer patients in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U. S. Department of Health and Human Services F. D. A. Center for Drug Evaluation Research. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2009;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodd M, Janson S, Facione N, et al. Advancing the science of symptom management. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33:668–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Ullrich C, et al. Symptoms and Distress in Children With Advanced Cancer: Prospective Patient-Reported Outcomes From the PediQUEST Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riesch SK, Anderson LS, Angresano N, Canty-Mitchell J, Johnson DL, Krainuwat K. Evaluating content validity and test-retest reliability of the children's health risk behavior scale. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23:366–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart JL, Lynn MR, Mishel MH. Evaluating content validity for children's self-report instruments using children as content experts. Nurs Res. 2005;54:414–418. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200511000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schilling LS, Dixon JK, Knafl KA, Grey M, Ives B, Lynn MR. Determining content validity of a self-report instrument for adolescents using a heterogeneous expert panel. Nurs Res. 2007;56:361–366. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000289505.30037.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomlinson D, Gibson F, Treister N, et al. Understandability, content validity, and overall acceptability of the Children's International Mucositis Evaluation Scale (ChIMES): child and parent reporting. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31:416–423. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31819c21ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedstrom M, Haglund K, Skolin I, von Essen L. Distressing events for children and adolescents with cancer: child, parent, and nurse perceptions. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2003;20:120–132. doi: 10.1053/jpon.2003.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, et al. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1624–1632. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basch E, Iasonos A, McDonough T, et al. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: results of a questionnaire-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:903–909. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70910-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laugsand EA, Sprangers MA, Bjordal K, Skorpen F, Kaasa S, Klepstad P. Health care providers underestimate symptom intensities of cancer patients: a multicenter European study. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2010;8:104. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis E, Nicolas C, Waters E, et al. Parent-proxy and child self-reported health-related quality of life: using qualitative methods to explain the discordance. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:863–871. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cremeens J, Eiser C, Blades M. Factors influencing agreement between child self-report and parent proxy-reports on the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL) generic core scales. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2006;4:58. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajmil L, Lopez AR, Lopez-Aguila S, Alonso J. Parent-child agreement on health-related quality of life (HRQOL): a longitudinal study. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2013;11:101. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upton P, Lawford J, Eiser C. Parent-child agreement across child health-related quality of life instruments: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:895–913. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irwin DE, Gross HE, Stucky BD, et al. Development of six PROMIS pediatrics proxy-report item banks. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2012;10:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Quality Forum. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Performance Measurement. [Accessed 16 May 2015]; Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/12/Patient-Reported_Outcomes_in_Performance_Measurement.aspx.

- 20.Matza LS, Patrick DL, Riley AW, et al. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: report of the ISPOR PRO good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2013;16:461–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tzelepis F, Rose SK, Sanson-Fisher RW, Clinton-McHarg T, Carey ML, Paul CL. Are we missing the Institute of Medicine's mark? A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing quality of patient-centred cancer care. BMC cancer. 2014;14:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D. Enhancing nursing research with children and families using a developmental science perspective. Annual review of nursing research. 2003;21:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerner RW D, Jacobs F. In: Historical and theoretical bases of applied developmental science In Handbook of Applied Developmental Science. Lerner RW D, Jacobs F, editors. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity--establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2--assessing respondent understanding. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2011;14:978–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins JJ, Byrnes ME, Dunkel IJ, et al. The measurement of symptoms in children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:363–377. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeve BB, Withycombe JS, Baker JN, et al. The first step to integrating the child's voice in adverse event reporting in oncology trials: a content validation study among pediatric oncology clinicians. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1231–1236. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Detmar SB, Aaronson NK, Wever LD, Muller M, Schornagel JH. How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients' and oncologists' preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3295–3301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.