Abstract

African American adolescents report more depressive symptoms than their European American peers, but the reasons for these differences are poorly understood. This study examines whether risk factors in individual, family, school, and community domains explain these differences. African American and European American adolescents participating in the Birmingham Youth Violence Study (N=594; mean age 13.2 years) reported on their depressive symptoms, pubertal development, aggressive and delinquent behavior, connectedness to school, witnessing violence, and poor parenting. Primary caregivers provided information on family income and their education level, marital status, and depression, and the adolescents’ academic performance. African American adolescents reported more depressive symptoms than European American participants. Family socioeconomic factors reduced this difference by 29%; all risk factors reduced it by 88%. Adolescents’ exposure to violence, antisocial behavior, and low school connectedness, as well as lower parental education and parenting quality, emerged as significant mediators of the group differences in depressive symptoms.

Keywords: racial differences, depression, early adolescence, violence

Although the findings are somewhat mixed across studies (Anderson & Mayes, 2010), a number of investigations have found higher levels of depression among African American adolescents compared to their European American peers, with effect sizes ranging from small to medium (Emslie, Weinberg, Rush, Adams, & Rintelmann, 1990; Kistner, David-Ferdon, Lopez, & Dunkel, 2007). Multiple reasons for these differences have been proposed, but few have been empirically tested.

Theoretical models of depression point to key roles of individual vulnerabilities and environmental stress in the etiology of depression (Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1998). Because African American families are more likely to experience socioeconomic disadvantage, lower socioeconomic status (SES) may serve as a general marker of environmental stress that may explain higher levels of depressive symptoms in African American adolescents. However, low SES contributes to more specific stressors that may play a more proximal role in racial differences in adolescent depression, while being more amenable to interventions than SES. Ecological theories posit that socioeconomic disadvantage will affect child development through its impact on multiple domains, including families, neighborhoods, and schools, as well as the individual children (McLoyd, 1998). Indeed, African American adolescents experience greater risks for depression across all these domains, including more parental depression and less nurturing and consistent parenting within the family, greater exposure to violence in their communities, poor academic functioning and low connectedness in the school context, and early puberty and greater antisocial behavior within the individual (Mrug, Loosier, & Windle, 2008; Pinderhughes, Nix, Foster, Jones, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2007; Swanson, 2003). The purpose of this study was to examine whether family SES, as well as these more specific risk factors, explain differences in depressive symptoms between African American and European American early adolescents.

Method

This cross-sectional study uses data from Wave 2 of the Birmingham Youth Violence Study (Mrug et al., 2008) conducted in Birmingham, Alabama, USA in 2004–2005. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The sample included 594 early adolescents (M age 13.2 years, SD=0.9) and their parents; 469 youth (79%) were identified by their parents as African American and 125 (21%) as European American; 52% were males. Additional 9 participants were identified as another race/ethnicity; these youth were excluded from this report. Adolescents were initially recruited from 17 Birmingham area schools selected through a school-based probability sampling procedure (42% participation rate), yielding a sample whose demographic composition (including racial distribution) was representative of the sampled population. Parents and adolescents provided informed consent and assent. During individual interviews, adolescents and parents provided information on the following variables.

Adolescents’ depressive symptoms were measured with self-report on six items from the Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) scale of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Predictive Scales (DPS; Lucas et al., 2001). Items included loss of pleasure and interest in activities, low energy level, low self-worth, suicidal ideation, fatigue, and concentration difficulties. The six dichotomous items were summed (Cronbach’s α =.68).

Family SES was measured with parents’ report of family income (13-item scale), their education level (8-item scale) and single parent status (vs. married).

More specific family risk factors included parental depression and parenting quality. Parental depression was measured with self-report on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) with the 20 items rated 1 (rarely) to 4 (most or all the time) and summed (Cronbach’s α=.76). Parenting quality was based on adolescent report of parental nurturance (5 items; Barnes & Windle, 1987), and harsh and inconsistent discipline (4 items each; Ge, Conger, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994). All scales were coded with higher scores indicating poorer parenting, standardized to z-scores and averaged (all items α=.64).

Community risk included witnessing violence, measured with adolescent report of whether they witnessed a threat of violence, actual violence, or violence involving a weapon in their neighborhood, school, or home in the last 12 months (Mrug et al., 2008). The nine indicators (type of violence in each context) were summed.

School risks involved academic achievement and school connectedness. Academic achievement was assessed with parent report of adolescents’ grades, ranging from 1 (mostly D’s and F’s) to 5 (mostly A’s and B’s). School connectedness was evaluated with adolescent self-report on 8 items from the School Connectedness Scale (Sieving et al., 2001), rated 1 (ztrongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) and summed (Cronbach’s α=.77).

Individual risks included pubertal development and two forms of antisocial behavior –aggression and delinquency. Pubertal development was measured with adolescent self-report of Tanner stages of pubic hair and breast (for girls) or penis/scrotum (for boys), using descriptions and pictures. The two pubertal variables were rated 1 (prepubertal) to 5 (fully developed) and averaged. Aggressive behavior was assessed with adolescent self-report using the 18-item overt aggression scale from the Form and Functions of Aggression measure (Little, Jones, Henrich, & Hawley, 2003). Items were rated on a 4-point scale (Not at all true = 1) to (Completely true = 4) and summed (Cronbach’s α=.88). Delinquency was measured with self-report asking about engagement in 27 different delinquent acts in the last 12 months (Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985), including status offenses, theft, destruction of property, assaults, selling illegal substances, public disorder and robbery. The dichotomous items were summed (Cronbach’s α =.80).

Bivariate statistics were used to determine which adolescent and parent reported variables related to both race and adolescents’ depression. These variables were then examined as mediators of differences between African American and European American adolescents’ depressive symptoms using path analyses in Mplus 7. Initially, a direct effect model tested group differences in depressive symptoms. The analyses of indirect effects were then conducted in three steps. First, each risk factor was examined in a separate model, so results would not be confounded by its associations with other risk factors. The second model then included the three family SES indicators (income, education and single parent status) to evaluate the extent to which family SES explained racial differences in depressive symptoms. Finally, all risk factors that have been associated with both race and depressive symptoms were included in the third model. In each analysis, all paths were adjusted for adolescent gender and age, and the residuals of all mediators in the second and third models were allowed to covary. Significance of indirect effects was tested with boas-corrected bootstrapping using 1,000 bootstrap samples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Results

Racial differences emerged for all variables (Table 1). Compared to European American adolescents, African American adolescents experienced more depressive symptoms (Cohen’s d=0.33). In addition, parents of African American adolescents reported lower levels of family income and education, were more likely to be unmarried, and experienced more depressive symptoms themselves. African American adolescents reported lower parenting quality, greater witnessing of violence, lower academic achievement and school connectedness, more advanced pubertal development, and higher levels of aggression and delinquency than European American adolescents.

Table 1.

Racial Differences and Correlations with Depressive Symptoms of All Variables

| European American M (SD) | African American M (SD) | Group p | r with depressive symptoms | Indirect effect b [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | 2.16 (1.67) | 2.72 (1.70) | <.001 | -- | -- |

| Family income | 8.78 (3.81) | 5.71 (3.68) | <.001 | −.13*** | .11 [.02 to .22] |

| Parental education | 4.83 (1.91) | 3.93 (1.54) | <.001 | −.15*** | .09 [.02 to .18] |

| Single parent | 28% | 65% | <.001 | −.10* | .11 [−.05 to .29] |

| Parental depression | 30.18 (8.03) | 33.22 (10.18) | <.001 | .13** | .04 [.002 to .10] |

| Poor parenting | −0.17 (0.62) | 0.05 (0.73) | .003 | .26*** | .09 [.01 to .19] |

| Witnessing violence | 1.11 (0.86) | 1.64 (0.88) | <.001 | .33*** | .30 [.17 to .46] |

| Academic achievement | 4.15 (1.16) | 3.78 (1.15) | .002 | −.11** | .04 [−.001 to .11] |

| School connectedness | 27.15 (3.74) | 25.44 (4.71) | <.001 | −.24*** | .14 [.07 to .25] |

| Pubertal development | 2.76 (0.84) | 3.56 (0.88) | <.001 | .08 | -- |

| Aggression | 46.50 (10.39) | 51.22 (12.42) | <.001 | .32*** | .17 [.06 to .30] |

| Delinquency | 1.47 (2.13) | 2.56 (2.89) | <.001 | .30*** | .16 [.07 to .28] |

Note:

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Adolescents’ depressive symptoms were associated with most of the hypothesized mediators (Table 1): lower family income and parental education, single parent family, parental depression, poorer parenting, greater witnessing of violence, lower academic achievement and school connectedness, and greater aggression and delinquency. Thus, all variables except pubertal development were associated with both race and depressive symptoms and were tested as mediators.

All path models were just identified (df=0) and thus had perfect fit. The direct effect model confirmed higher levels of depressive symptoms among African American adolescents (β=.12, p<.01) after adjusting for gender and age. When examined in isolation from other risk factors, higher levels of depressive symptoms among African American adolescents were partly explained by lower family income, lower parental education, greater parental depression, poorer parenting, greater witnessing violence, lower school connectedness, and more aggressive and delinquent behavior, respectively (i.e., these indirect effects were significant at p<.05; see Table 1).

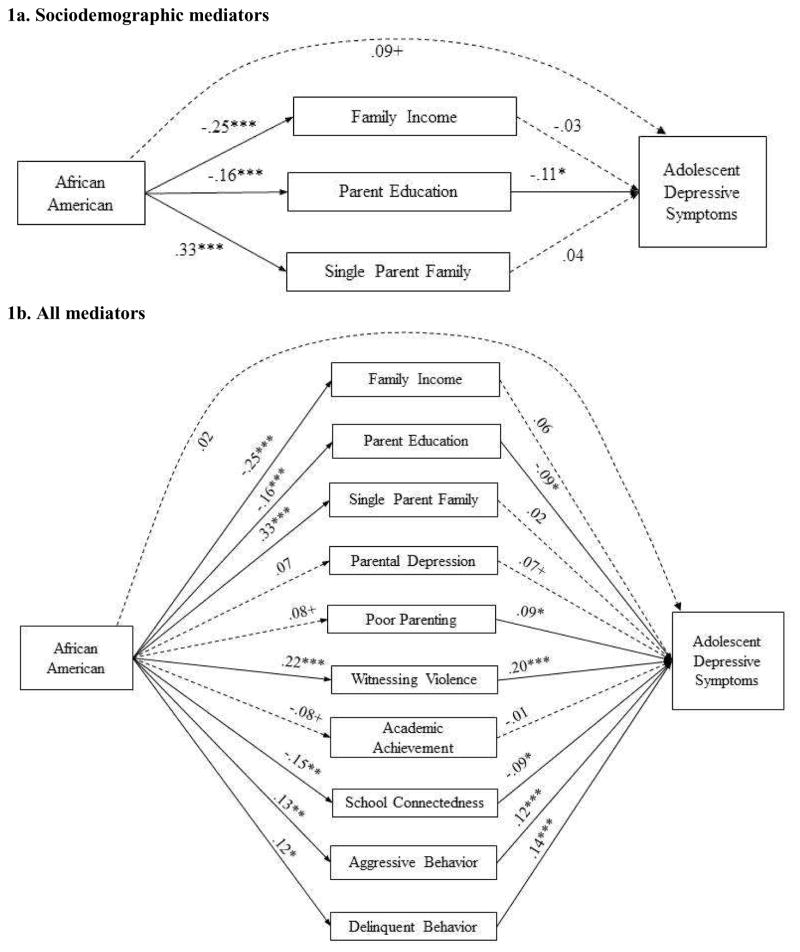

The model with all three family SES risk factors (Figure 1a) revealed that only parental education significantly mediated racial differences in depressive symptoms (b=.07, p<.05, 95% CI [.01 to .17]). The direct effect of African American race (β=.09, p=.064) was reduced by 29% and the model explained 4% of variance in depressive symptoms. The final indirect effects model, containing all risk factors (Figure 1b), yielded six significant indirect effects: greater depressive symptoms among African American adolescents were partly explained by lower parental education (b=.06, p<.05, 95% CI [.01 to .16]), poorer parenting (b=.03, p<.05, 95% CI [.001 to .10]), greater witnessing violence (b=.19, p<.01, 95% CI [.09 to .31]), lower school connectedness (b=.06, p<.05, 95% CI [.01 to .14]), more aggressive behavior (b=.07, p<.05, 95% CI [.01 to .16]), and greater delinquency (b=.07, p<.01, 95% CI [.02 to .15]). The direct effect of African American race on depressive symptoms was reduced by 88% from the direct effect model and was no longer significant (β=.02, p=.724), indicating full mediation. This model explained 22% of variance in depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Sociodemographic (a) and all (b) mediators of differences in depressive symptoms between African American and European American adolescents. All paths are adjusted for age and gender. Dashed lines indicate non-significant paths (p>.05). +p<.10; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Discussion

The results replicate previous findings of elevated depressive symptoms in African American early adolescents, with the small-to-medium effect size consistent with prior work (Emslie et al., 1990; Kistner et al., 2007). This difference was not surprising given higher levels of multiple risk factors for depression present among African American adolescents. In particular, African American adolescents were growing up with fewer financial resources and less educated parents who were more likely to be unmarried, experiencing depressive symptoms themselves, and utilizing less optimal parenting strategies (i.e., more harsh and inconsistent discipline and less nurturance). African American adolescents were also exposed to more violence, less academically successful and less connected to school, and they engaged in more aggressive and delinquent behavior. Path analyses indicated that 29% of the racial difference in depressive symptoms could be explained by sociodemographic factors and additional 59% by other risk factors for depression that were elevated among African American adolescents. Consistent with theories describing the etiology of adolescent depression (Lewinsohn et al., 1998), the risk factors that uniquely explained higher levels of depressive symptoms in African American adolescents included environmental stressors, such as witnessing violence (which had the largest mediating effect), lower parental education, and poorer parenting, as well as individual vulnerabilities, such as lower school connectedness and more aggressive and delinquent behavior.

Our findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating that socioeconomic factors attenuate, but not eliminate heightened emotional distress experienced by African American adolescents (McLoyd, 1990). Among SES indicators, lower parental education played the most important role in explaining higher depressive symptoms in African American adolescents, whereas family income and single parent status were no longer related to depressive symptoms when parental education was included in the model. These results likely reflect overlap among the SES indicators, but they are also consistent with other literature on the prominent role of parental education in adolescent depression (Eley et al., 2004). Although all SES indicators imply the availability of resources, parental education may be unique in signifying the ability to teach effective problem solving to children, thus emerging as the only significant SES mediator.

The common thread among other risk factors that helped explain higher depressive symptoms among African American adolescents is a negative impact on social relationships, which are central in protecting against depression (Lewinsohn et al., 1998). Indeed, low school connectedness and poor parenting (which included a measure of nurturance) directly indicate lower quality of adolescents’ relationships with teachers and parents, and the negative impact of antisocial behavior and violence exposure on interpersonal relationships has been well documented (Laird, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, 2003; Lynch & Cicchetti, 2002). Thus, it is possible that these variables may contribute to increased depressive symptoms through lower quality of relationships, as well as other mechanisms (e.g., trauma or low self-esteem resulting from exposure to violence and antisocial behavior). By contrast, academic achievement did not emerge as a mediator of racial differences in depressive symptoms (not even in analyses involving no other mediators), likely due to its weak relationship with depressive symptoms.

Although our cross-sectional results cannot establish causality, it is possible that interventions for socioeconomically disadvantaged African American adolescents aimed at reducing exposure to violence and aggressive and delinquent behavior, improving school connectedness, and providing education and support to families may help diminish differences in depressive symptoms between African American and European American adolescents. Indeed, universal violence prevention programs reduce adolescents’ depressive symptoms in addition to youth violence (Wolfe et al., 2003). Future research should examine whether the addition of intervention components directly targeting depression further improves effectiveness of violence prevention programs for emotional distress. The widespread implementation of evidence-based intervention programs among disadvantaged youth may reduce group differences in depression, and remains a priority for policy and practice.

Although the results are limited by the single geographic location and thus may not generalize to other geographic and cultural settings, this multi-informant study provides novel insights into the mechanisms that may play a role in racial differences in adolescent depression. Future research should replicate these findings, particularly for poor parenting which had low internal consistency and was only marginally associated with race in the full mediation model.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01MH098348) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R49-CCR418569).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sylvie Mrug, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Vinetra King, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Michael Windle, Emory University.

References

- Anderson ER, Mayes LC. Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Windle M. Family factors in adolescent alcohol and drug abuse. Pediatrician. 1987;14:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Eley TC, Liang H, Plomin R, Sham P, Sterne A, Williamson R, Purcell S. Parental familial vulnerability, family environment, and their interactions as predictors of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:289–298. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie GJ, Weinberg WA, Rush AJ, Adams RM, Rintelmann JW. Depressive symptoms by self-report in adolescence: Phase 1 of the development of a questionnaire for depression by self-report. Journal of Child Neurology. 1990;5:114–21. doi: 10.1177/088307389000500208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Parents’ stressful life events and adolescent depressed mood. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1994;35:28–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Parents’ monitoring-relevant knowledge and adolescents’ delinquent behavior: Evidence of correlated developmental changes and reciprocal influences. Child Development. 2003;74:752–768. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Jones SM, Henrich CC, Hawley PH. Disentangling the ‘whys’ from the ‘whats’ of aggressive behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW, Shaffer D, Regier DA, Narrow WE, Bourdon K, Dulcan MK, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Lahey BB, Friman P. The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): Efficiently screening for diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):443–449. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner JA, David-Ferdon CF, Lopez CM, Dunkel SB. Ethnic and sex differences in children’s depressive symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:171–181. doi: 10.1080/15374410701274942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18:765–794. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW, Shaffer D, Regier DA, Narrow WE, Friman P. The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): Efficiently screening for diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:443–449. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Cicchetti D. Links between community violence and the family system: Evidence from children’s feelings of relatedness and perceptions of parent behavior. Family Process. 2002;41:519–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Loosier PS, Windle M. Violence exposure across multiple contexts: Individual and joint effects on adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78:70–84. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, Jones D the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;63:941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, Beuhring T, Resnick MD, Bearinger LH, Shew M, Ireland M, Blum RW. Development of adolescent self-report measures from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson CB. Who Graduates? Who Doesn’t? A Statistical Portrait of Public High School Graduation, Class of 2001. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman AL, Grasley C, Reitzel-Jaffe D. Dating violence prevention with at-risk youth: A controlled outcome evaluation. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:279–291. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]