Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall glycolipid, Lipoarabinomannan, can inhibit CD4+ T cell activation by down-regulating phosphorylation of key proximal TCR signaling molecules Lck, CD3ζ, ZAP70 and LAT. Inhibition of proximal TCR signaling can result in T cell anergy, in which T cells are inactivated following an antigen encounter, yet remain viable and hyporesponsive. We tested whether LAM-induced inhibition of CD4+ T cell activation resulted in CD4+ T cell anergy. The presence of LAM during primary stimulation of P25TCR-Tg murine CD4+ T cells with M. tuberculosis Ag85B peptide resulted in decreased proliferation and IL-2 production. P25TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells primed in the presence of LAM also exhibited decreased response upon re-stimulation with Ag85B. The T cell anergic state persisted after the removal of LAM. Hypo-responsiveness to re-stimulation was not due to apoptosis, generation of FoxP3-positive regulatory T cells or inhibitory cytokines. Acquisition of the anergic phenotype correlated with up-regulation of GRAIL (gene related to anergy in lymphocytes) protein in CD4+ T cells. Inhibition of human CD4+ T cell activation by LAM also was associated with increased GRAIL expression. Small interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of GRAIL before LAM pre-treatment abrogated LAM induced hypo-responsiveness. In addition, exogenous IL-2 reversed defective proliferation by down-regulating GRAIL expression. These results demonstrate that LAM up-regulates GRAIL to induce anergy in Ag-reactive CD4+ T cells. Induction of CD4+ T cell anergy by LAM may represent one mechanism by which M. tuberculosis evades T cell recognition.

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is an intracellular pathogen and leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Most individuals require adaptive T cell immunity to control Mtb but fail to eradicate the bacilli. T cells and infected antigen presenting cells (APC) are central for control of Mtb but also targets of its immune evasion strategies. Mtb infection results in the activation of multiple T cell subsets that recognize a very diverse repertoire of antigens. Paradoxically, despite this extensive T cell repertoire, small numbers of Mtb bacilli survive and persist in granulomas by evading immune recognition and elimination.

Major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecule-restricted CD4+ T cells have a central role in the T cell response to Mtb. Recent studies have demonstrated that CD4+ T cells from persons who have controlled Mtb infection recognize a very diverse range of antigens (1–4). Antigenic variation among Mtb strains for CD4+ T cells is minimal and an unlikely mechanism of immune evasion (5). In light of these broad responses, it is likely that Mtb’s T cell immune evasion strategies involve direct effects on APC and/or CD4+ T cell function. Earlier studies determined that Mtb can inhibit MHC-II antigen processing in macrophages in a TLR-2 dependent manner and thus indirectly affect memory and effector CD4+ T cell function (6–11).

Exosomes and microbial microvesicles provide a mechanism for Mtb molecules to be directly delivered to CD4+ T cells in the immediate microenvironment of Mtb infection. Mannose-Capped Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) is one of the most abundant glycolipids in the Mtb cell wall and readily found in Mtb microvesicles (12). Our earlier studies showed that LAM can inhibit CD4+ T cell activation by down-regulating phosphorylation of the key proximal TCR signaling molecules Lck, CD3ζ, ZAP-70 and LAT in a TLR-2 independent manner (13, 14). LAM can interact with host cells by directly inserting into cell membranes, in addition to binding to host receptors (MR, DC-SIGN, Dectin-2, CD14) expressed on APC (15–18).

Assays used to measure effects of LAM on CD4+ T cell activation were short-term and did not address long-term effects of LAM on T cell function. Was LAM inhibition a transient phenotype, were Tregs activated, was there evidence for apoptosis or anergy? Anergy is characterized by persistent defective proliferation and IL-2 production by previously activated T cells upon re-stimulation (19, 20). Different biochemical pathways initiate and maintain the anergic state, including blockade of the Ras-MAPK pathway, and defects in ZAP70 and LAT phosphorylation (19–21). Gene related to anergy in lymphocytes (GRAIL) negatively regulates IL-2 transcription (22–25) and up-regulation of GRAIL is associated with induction and maintenance of anergy (24, 26). Anergy also occurs when T cells are stimulated either in the presence of TGFbeta and IL-10, or suppression by regulatory T cells (Treg) (24, 26, 27). Anergy induction may be a mechanism of immune evasion in chronic infections by SIV, HIV-1 and Schistosoma mansoni mostly due to manipulation of co-stimulatory molecules or up-regulated inhibitory cytokine production by APC (28–32).

Using an antigen specific system we determined the longer-term functional implication of LAM inhibition of CD4+ T cell activation. P25 TCR Tg CD4+ T cells activated in the presence of LAM were anergized. Once anergy was established, LAM was no longer required. After 5 days of rest, LAM was no longer detectable in T cells, yet CD4+ T cells previously treated with LAM proliferated poorly. Proliferation of anergic T cells was rescued by IL-2. The induction of anergy correlated with up-regulation of GRAIL in CD4+ T cells. LAM treatment of human CD4+ T cells also induced GRAIL protein. Inhibition of GRAIL mRNA with siRNA before LAM pre-treatment reduced T cell inhibition in naïve and Th1 polarized effector CD4+ T cells. Moreover, exogenous IL-2 reversed defective proliferation in LAM-anergized CD4+ T cells by down-regulating GRAIL expression. We conclude that LAM up-regulates GRAIL expression to induce anergy in Mtb-reactive CD4+ T cells. Anergy induction by LAM is another mechanism by which Mtb can evade CD4+ T cell recognition.

Materials and Methods

Antigens and Antibodies

Mtb Ag85B encompasses the major epitope (aa 240–254) recognized by P25 TCR-Tg T cells (peptide 25). Peptide 25 (NH2-FQDAYNAAGGHNAVF-COOH) was purchased from Invitrogen. LAM, anti-LAM Ab (Cs-35, 1:250 titer) and biotinylated Cs-35 (anti-LAM) from M. tuberculosis H37Rv were obtained from the Tuberculosis Vaccine Testing and Research Materials contract (NIAID HHSN266200400091C) at Colorado State University (CSU). The following mAbs and isotype controls were purchased for analysis of receptor expression: anti-CD3-PE, anti-CD4-APC, anti-CD28-APC, anti-Tim3-PE, anti-CTLA4-PE, anti-CD25-alexa Fluor-488, anti-FoxP3-PE, anti-Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 450, anti-cholera toxin subunit B-Alexa Fluor 647, anti-CD3-Alexa Fluor 647, anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 488, and LIVE/DEAD violet and yellow cell stain (all from ebioscience); anti-PD1-PE (BD Pharmingen); anti-Lag3-APC (Biolegend); anti-TCR-Vβ-PE and anti-CD40L-PE (Miltenyi Biotech).

For T-cell activation, hamster anti-mouse CD3ε (145-2C11), anti-mouse CD28 (clone 37.51), mouse anti-human CD3 (clone HIT3a), mouse anti-human CD28 and mouse anti-hamster secondary immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) were purchased from BD Biosciences. For Western blotting and intracellular staining for GRAIL, rabbit anti-GRAIL antibodies were purchased from Thermoscientific and Abcam and goat anti-rabbit IgG-FITC from Southern Biotech. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit mAb (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used for detection. For mouse and human IL-2 ELISA, primary and biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from ebioscience. Recombinant mouse IL-7 (407-ML-005) was purchased from R&D systems. Ionomycin (I3909) and dexamethasone were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Mice

Eight to ten-week-old female C57BL/6J were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Mycobacterial Ag85B-specific TCR transgenic (P25 TCR-Tg) mice were provided by Kiyoshi Takatsu (University of Tokyo, Japan) (33). P25TCR-Tg T cells recognize peptide (NH2-FQDAYNAAGGHNAVF-COOH) derived from Mtb Ag85B in the context of MHC II I-Ab (33). Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. All experiments were performed in compliance with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Guide for the care and use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University (protocol number: 2012-0020).

Isolation of mouse CD4+T cells

Mouse CD4+ T cells were isolated from spleens of 8- to 10-week old P25 TCR Tg mice or from the spleens of wild-type C57BL/6J mice. Tissues were dissociated, and RBC lysed in hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 0.83% ammonium chloride). Splenocytes were plated in 100-mm tissue culture plates and allowed to adhere for 1 h at 37° C. Untouched CD4+ T cells were purified from non-adherent splenocytes using a CD4+ T-cell-negative isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) by following manufacturer’s instructions (purity > 95%). For purification of CD4+CD25−T cells, negatively selected CD4+ T cells were positively selected for CD4 and then sorted by CD25 surface levels by flow sorting. For some experiments, highly purified naïve (CD25− CD44− CD62L+) CD4+ T cells were isolated from spleens using a combination of immune-MACS followed by FACS as described with some modifications (34). The average purity was 98 to 99%. CD4+ T cells were rested overnight in complete DMEM (BioWhittaker, East Rutherford, NJ) supplemented with 1 μM 2-merchatoethanol, 10 mM HEPES buffer, nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum prior to use in assays. The primary stimulation and re-stimulation of CD4+ T cells were performed in serum-free HL-1 medium (BioWhittaker, East Rutherford, NJ) supplemented with 1 μM 2-merchatoethanol, 10 mM HEPES buffer, nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin). For re-stimulation experiments, primed CD4+ T cells were rested for 5 days in complete DMEM as above, containing 20 ng/ml IL-7 to maintain viability.

Cultures of bone marrow-derived macrophages

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) were generated by culturing bone marrows from C57BL/6J mice in complete DMEM containing 20% L929 culture supernatant for 7–10 days. At day 8, BMM were matured by treating with IFNγ (4 ng/ml) for 48 h before use in assays. 2 ×106 BMM per well in 6-well plates or 1 ×105 BMM per well in 96-well plates were washed three times, lightly fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in medium for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were washed extensively, and pulsed with Ag85B peptide for 4 h at 37°C before incubation with untreated, LAM-treated or ionomycin-treated P25 TCR Tg CD4+ T cells.

CD4+ T cell stimulation (priming) and re-stimulation assays

To prime, 1×106 P25TCR Tg CD4+ T cells were left untreated (none) or pretreated with LAM (1 μM) or lonomycin (Iono) [1 μM] (positive control for anergy induction), and incubated for 1 h or 24 h at 37°C. T cells were washed and initially stimulated by co-culturing with 2 ×106 paraformaldehyde-fixed BMM pulsed with 1 μg/ml of Mtb Ag 85B peptide (APC + peptide) in 6-well plates for 48 h. After 24 h, supernatants were collected and IL-2 levels measured by ELISA as described previously (14). After 48 h, primed CD4+ T cells were collected from culture by vigorous pipetting and extensively washed in DMEM (3 times). For polyclonal stimulation, CD4+ T cells pretreated with and without LAM were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε (1 μg/ml) and soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) for 24 h to 48 h. After 24 h of stimulation, supernatants were collected, and IL-2 levels measured by ELISA. T cell proliferation was measured after 48 h by [3H]-thymidine incorporation.

For re-stimulation, primed P25TCR Tg or polyclonal CD4+ T cells were washed and rested for 5 additional days in IL-7 to maintain viability. T cells were harvested, washed and live cells separated by density gradient centrifugation before re-stimulation. To re-stimulate, 5×104 P25TCR Tg CD4+ T cells per well were co-cultured with 1×105 Ag85B-pulsed fixed-BMM in triplicate wells in 96-well plates for 48 h. Polyclonal CD4+ T cells (5×104/well) were re-stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3e and soluble anti-CD28 as described above. After 24 h of re-stimulation, supernatants were collected, and IL-2 levels measured by ELISA. T cell proliferation was measured after 48 h by [3H]-thymidine incorporation.

siRNA experiments required proliferating cells and were performed with pre-activated naïve CD4+ T cells and in vitro generated Th1 effector cells. In brief, naïve (CD25− CD44− CD62L+) CD4+ T cells were stimulated with plate bound anti-CD3e and soluble anti-CD28 for 3 days. Cells were washed and rested in IL-7 containing media for 48 hours before transfection with anti-GRAIL siRNA or non-target negative control. For Th1 effector CD4+ T cell generation, naïve (CD25− CD44− CD62L+) CD4+ T cells were stimulated with plate bound anti-CD3e and soluble anti-CD28 for 3 days in the presence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml) and anti-IL-4 (5 μg/ml). Cells were washed and rested in IL-7 containing media for 48 hours before transfection with anti-GRAIL siRNA or non-target negative control.

Isolation and stimulation of human CD4+ T cells

Primary human CD4+ T cells from healthy donors were isolated as described previously (34). Briefly, peripheral blood was obtained from healthy donors and the T cells isolated from the buffy coat following Hypaque-Ficoll (Amersham Biosciences) density gradient centrifugation, followed by isolation with miltenyi beads. Where required, flow sorting was used. T cells (> 95% purity) were cultured/rested in complete ex vivo media (Life Technologies) until use. CD4+ T cells pretreated with or without LAM were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε (10 μg/ml) and soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml). All human cell studies were approved by the Case Western Reserve University Institutional Review Board and the National Institutes of Health (IRB number: 03-88-63). All adult subjects provided informed written consents, and a parent or guardian of any child participant provided informed consent on their behalf.

IL-2 secretion and T cell proliferation

Supernatants were assayed for IL-2 production in Immulon 4HBX flat-bottomed microtiter plates (Thermo) coated with purified capture IL-2 mAb (1 μg/ml) and detected with biotinylated IL-2 mAb (1 μg/ml), followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and phosphatase substrate (Sigma-Aldrich). Plates were read with a versa Max turntable microplate reader and data analyzed with soft Max Pro LS analysis software. Cells were pulsed during the final 16 h of culture with 1 μCi of [3H] thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ)/well. [3H] thymidine incorporation was measured by liquid scintillation counting, and the results expressed as mean counts per minute (cpm) of triplicate values.

Flow cytometry

For surface receptor expression, cells were stained with mAbs for the following receptors: CD3, CD4, CD28, CD25, TCR Vβ, CTLA4, PD1, Lag-3, Tim-3 and CD40L (Biolegend). Live cell staining was performed with LIVE DEAD fixable violet or yellow dead cell stain (eBioscience). Cells were fixed and permeabilized with BD Cytofix Cytoperm kit (BD PharMingen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions before flow cytometry. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed with anti-FoxP3 and anti-CTLA4. For apoptosis assays, cells were stained with Annexin V eFluor 450 and LIVE DEAD yellow fixable dead cell stain. For LAM staining assays, CD4+ T cells pretreated with LAM were harvested and stained with anti-LAM mAb (Cs35-biotin) or biotin mouse IgG3, k isotype control (BD Biosciences) for 30 min, followed by streptavidin-alexafluor-488 for 30 min on ice. For GRAIL expression, cells were stained for intracellular GRAIL using rabbit anti-GRAIL primary antibody (Abcam) followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-FITC secondary antibody (southern Biotech). After staining, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on an LSR II (BD Biosciences) and data analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Confocal microscopy

Human CD4+ T cells were incubated with LAM (2 μM) for 30 min. at 37°C with gentle shaking. After incubation with LAM, lipid rafts in the T cell membrane were labeled by incubating with Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated-cholera toxin subunit B (CT-B, 1 μg/ml) for 20 min. on ice, washed extensively, labeled with anti-LAM mAb (clone Cs35) followed by Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated IgG and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. To label CD3-TCR complex, after incubation with LAM, cells were labeled on ice with anti-LAM mAb (clone Cs35) followed by Alexa Fluor 488 congugated-anti-mouse IgG. Then, Alexa Fluor 647 congugated-anti-CD3 mAb was used to label the CD3-TCR complex. Cells were visualized in a Leica DM16000B confocal microscope (100x oil immersion lens) and images acquired.

Knockdown of GRAIL expression by small interfering RNA (siRNA)

Knockdown of GRAIL was performed as described previously (22). Briefly, preactivated naïve or in vitro differentiated Th1 CD4+ T cells were transfected with a solution of four GRAIL (i.e. ring finger protein-128, gene ID 66889) or one control siRNAs [Qiagen, Valencia, CA] to knockdown GRAIL expression by using the HiPerfect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The target sequences for the mouse GRAIL siRNAs are: 1) 5′-CTCGAAGATTACGAAATGCAA-3′, 2) 5′-CAGGATAGAAACTACCATCAA-3′, 3) 5′-CTCTAATTACATGAAATTTAA-3′, 4) 5′-CAGGGCCTCCTAGTTTACTATGAA-3′. For transfection of siRNA, a total of 3×106 CD4+ T cells plated at 3×105 cells per well in a 24-well plate were transfected with 75 nM or 100 nM each of these GRAIL siRNAs altogether using 6 μl HiPerfect dissolved in serum-free Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 6 h of transfection, an additional 400 μl DMEM medium with 10% FBS was added and cells allowed to incubate at 37°C for 24 h. A non-target negative control (NC)-siRNA (5′-AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was transfected into CD4+ T cells to serve as experimental control for non-specific effects. After 24 h, levels of remaining protein were evaluated by Western blot with β-actin as loading control. GRAIL knocked down or control CD4+ T cells were left untreated or treated with LAM for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed and stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε and soluble anti-CD28 for 24 h to 48 h. After 24 h and 48 h of stimulation, supernatants were collected, and IL-2 and IFN-γ measured by ELISA. T cell proliferation was measured after 48 h by [3H]-thymidine incorporation.

Western blotting

For analysis of GRAIL protein expression, T cell lysates obtained from primed, re-stimulated or knocked down CD4+ T cells were suspended in 2X sample buffer and heated to 95°C. Proteins (20 μg/well were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% ready-to-use gels (Invitrogen) under reducing conditions and electro-transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). After transfer, membranes were incubated at room temperature for 1 h in blocking buffer (1XPBS, 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween-20). Primary (rabbit anti-GRAIL, Thermoscientific) and mouse anti-rabbit HRP conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were diluted in same buffer containing 1XPBS, 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween-20 and incubated for 16 h and 1 h, respectively. Western blots were analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH).

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as mean +/− SEM or +/− SD. Statistical analyses were performed as either student t test or two-way ANOVA (Graph-Pad Prism software, version 6.0 for Mac). A p value of <0.05 was considered significant, and represented as *.

Results

Association of LAM with CD4+ T cell membrane correlates with inhibition of CD4+ T cell activation during priming

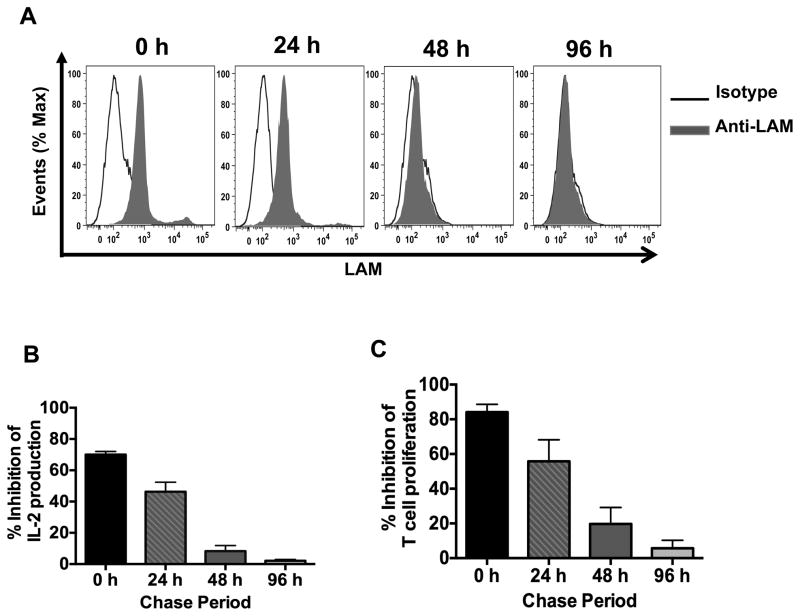

LAM can incorporate into the membranes of murine and human T cells within 30 min, with maximal incorporation occurring within several hours (16, 17). We reported previously that pretreatment of CD4+ T cells with LAM inhibits activation upon stimulation (14). However, the correlation between LAM association with the T cell membrane and inhibition of T cell function has not been analyzed. CD4+ T cells pretreated with LAM for 1 h and washed were cultured for different intervals before activation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 and LAM binding to the cell membrane determined in parallel by flow cytometry. Because more than 40% of mouse CD4+ T cells ex-vivo will die within 24 h, unless stimulated or maintained viable by addition of cytokines, IL-7 was used to maintain a CD4+ T cell viability of more than 80% (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Eighty percent of LAM-pretreated CD4+ T cells also remained viable in IL-7 at 0, 24 and 48 h time points and over 70% at 96 h after LAM pretreatment (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Treatment with IL-7 did not render CD4+ T cells refractory to LAM-inhibition of T cell activation (Supplemental Fig. 1C). LAM was detectable in the T cell membrane at 0 and 24 h after pretreatment, but did not remain associated with the cell membrane for more than 24 h, as demonstrated by the time-dependent loss of anti-LAM mAb staining (Fig. 1A). Whereas, 50–70% inhibition of IL-2 secretion and proliferation was observed for CD4+ T cells stimulated at 0 and 24 h after LAM pretreatment, T cells stimulated 48 and 96 h after LAM pretreatment were not inhibited (Fig. 1B and 1C), demonstrating a correlation between the period when LAM was present in the membrane and the period when inhibition of T cell responses was observed. The viability of untreated and LAM-treated T cells were similar (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Untreated CD4+ T cells were analyzed in parallel, stained negative for LAM and activated normally (data not shown). These results indicate that LAM has to be associated with the CD4+ T cell membrane at the time of primary TCR/CD3 stimulation for LAM to inhibit T cell activation.

FIGURE 1.

Presence of LAM on CD4+ T cell membranes is required for inhibition of CD4+ T cell activation after primary stimulation. (A) CD4+ T cells (1×106) were pre-treated with LAM (1 μM) or media (untreated) for 1 h at 37°C, washed and incubated with IL-7 (20 ng/ml). Cells were chased for 0, 24, 48 and 96 h. At the end of each chase period, cell aliquots were removed and washed with media, prior to LAM staining. LAM-treated T cells were stained with anti-LAM mAb or isotype control and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B, C) LAM-treated and untreated CD4+ T cells at the end of each chase period were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml) and soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml). IL-2 was measured in 24 h culture supernatants by ELISA (B) and T cell proliferation was measured after 48 h by [3H] thymidine incorporation (C). Percent inhibition reflects the ratio of IL-2 (B) or proliferation (C) between LAM-treated and untreated T cells x 100. Error bars indicate mean +/− SD of triplicate wells of one representative experiment (n=3).

LAM induces CD4+ T cell anergy

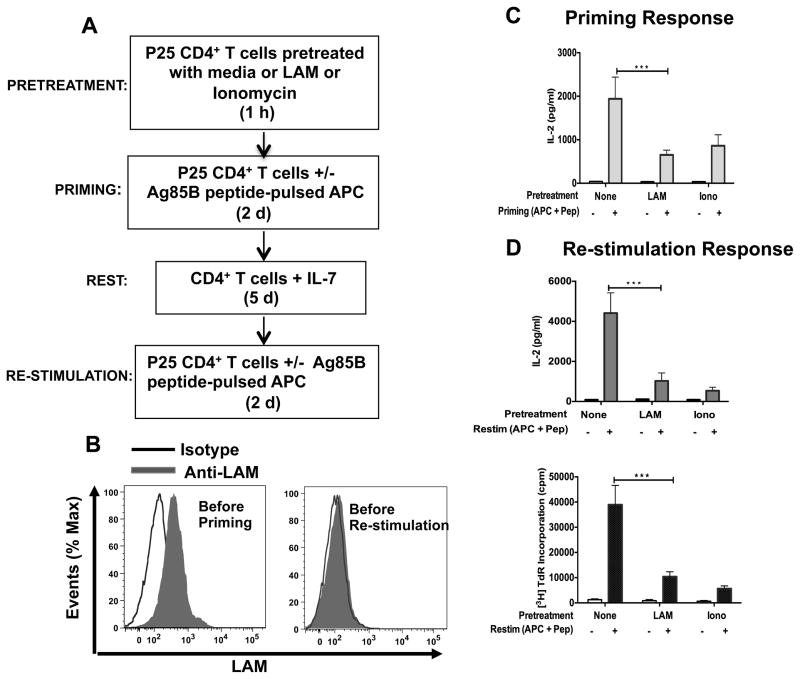

Because suppression of IL-2 expression and T cell proliferation are associated with induction of anergy, we next determined if LAM-induced inhibition during primary stimulation of CD4+ T cells (priming in our experimental system) resulted in anergy. We utilized an in vitro T cell-and APC-based system to induce functional anergy (35) (Fig. 2A). LAM has inhibitory effects on BMM that could indirectly inhibit T cell proliferation and cytokine production (18). In addition, activated viable Mtb-infected BMM can secrete cytokines that are inhibitory and T cell anergizing such as IL-10 and TGFβ. To rule out these inhibitory effects, BMM were fixed before use in priming and re-stimulation experiments (see methods). Fixed BMM were pulsed with Mtb Ag85B peptide (APC + peptide) and used to prime LAM-pretreated P25 TCR Tg CD4+ T cells. Calcium ionophore ionomycin served as a positive control for anergy induction (29). As shown before, CD4+ T cells primed by Ag85B peptide-pulsed BMM in the presence of LAM secreted lower amounts of IL-2 (Fig. 2C), and this correlated with detection of LAM on the cell surface (Fig. 2B, left histogram). More importantly, T cells primed in the presence of LAM produced significantly lower amounts of IL-2 and proliferated less compared to control cells after antigenic re-stimulation 7 days later (Fig. 2D, upper and lower panels), even though LAM was not present on the cell membrane at this point (Fig. 2B, right histogram). The level of inhibition by LAM during priming upon re-stimulation was similar to that measured by the positive control, ionomycin. Because suboptimal or high antigen concentrations are an alternative potential cause of hypo-responsiveness upon TCR stimulation (36), we stimulated CD4+ T cells over a range of Ag85B peptide concentrations in the presence of LAM, and observed LAM-induced inhibition over a wide range of antigen concentrations, indicating that exposure to higher concentrations of antigen did not affect LAM-induced anergy (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Maximum anergy induction was observed with concentrations of LAM as low as 0.62 μM based on LAM response experiments (Supplemental Fig. 2B). These data suggest that defective proliferation in cells stimulated in the presence of LAM is a result of functional anergy. The results also suggest that the presence of LAM in the CD4+ T cell membrane is required during priming to induce functional T cell anergy, but once anergy is induced, the presence of LAM is no longer required to maintain anergy.

FIGURE 2.

LAM induces anergy in P25 CD4+ T cells. (A) Experimental design. (B) P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells (1×106) pretreated with LAM for 1 h were stained with anti-LAM mAb or with an isotype control mAb before priming (left histogram) or 5 d after priming and before re-stimulation (right histogram), and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) 1 h after pretreatment, untreated (none), LAM-treated or ionomycin-treated T cells were primed with Ag 85B peptide-pulsed APC for 48 h. IL-2 was measured in 24-h culture supernatants by ELISA. (D) Primed P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells (in C) were cultured for 5 d in IL-7. Cells were washed and re-stimulated with Ag85B peptide-pulsed APC. IL-2 was measured in 24 h-culture supernatants by ELISA (upper panel) and cell proliferation was determined after 48 h by [3H] thymidine incorporation (lower panel). Data in C through D are means +/− SEM of three independent experiments conducted in triplicate. ***P<0.001 (paired t test)

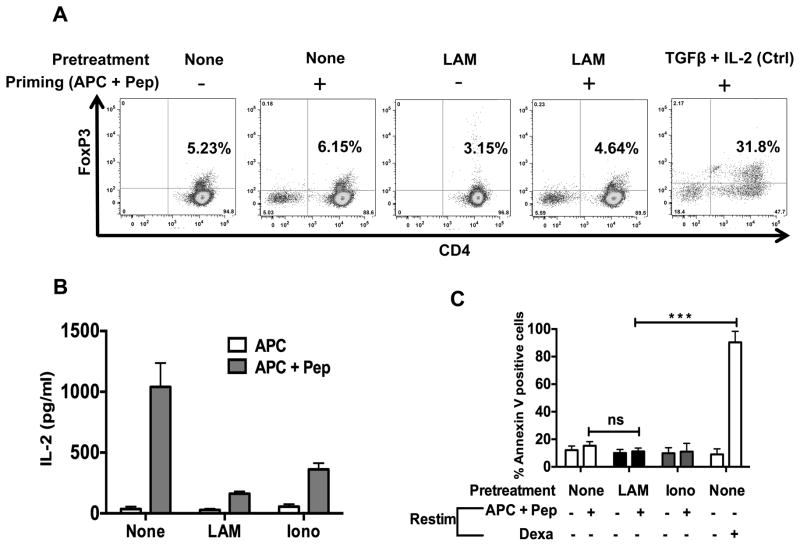

Tregs or apoptosis is not responsible for LAM-induced CD4+ T cell anergy

Other mechanisms responsible for defective T cell proliferation are inactivation of antigen-reactive CD4+ T cells by Tregs or apoptosis (27, 37–39). We used flow cytometry to measure the number of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells 48 hours after primary stimulation and 5 days of rest. The number of FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells detected in both LAM-treated and untreated CD4+ T cells ranged from 3–6% (Fig. 3A). This falls within the 5–15% level of natural Tregs found in spleens of healthy mice, and is not sufficient to suppress conventional CD4+ T cells (27). In flow purified CD3+CD4+CD25− T cells, anergy was still induced by LAM and ionomycin, even though nTregs had been depleted (Fig. 3B). There also was no increase in IL-10 production by LAM treated CD4+ T cells (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

LAM does not induce FoxP3-positive regulatory T cells and/or increase activation-Induced cell death (apoptosis). (A) 1×106 P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells left untreated (none) or treated with LAM (as described in Fig. 2) were primed with APC-Ag85B peptide for 48 h. Cells were washed and cultured in IL-7 for 5 d. Cells were washed, and Foxp3-positive T cells were determined by intracellular staining and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) 1×106 T reg depleted P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells were left untreated (none) or pre-treated with LAM (1 μM) for 1 h. Cells were washed and primed with Ag 85B peptide-pulsed (APC + Pep) or mock-pulsed APC (APC). After 48 h cells were washed and rested in media containing IL-7 for 5 days. CD4+ T cells were then washed and re-stimulated for 24 h. IL-2 was measured in 24-h culture supernatants by ELISA. (C) P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells suppressed through treatment with LAM or ionomycin (as described in Fig. 2) were re-stimulated with APC-Ag85B peptide. After 24 h, T cells were stained with Annexin V eFluor 450 and apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry analysis of annexin V-positive T cells. At re-stimulation, T cells treated with 1 μM of dexamethasone (Dexa) were used as a positive control for apoptosis. Error bars indicate means +/− SD of triplicate wells of one representative experiment (n=3). ***P<0.001 (paired t test).

To determine whether LAM induced apoptosis and whether apoptosis accounted for hypo-responsiveness upon re-stimulation, Annexin V was measured by flow cytometry 48 h after re-stimulation. Eight to12% of CD4+ T cells were Annexin V-positive (Fig. 3C), with similar levels in LAM-treated and untreated T cells. Moreover, LAM-induced anergy was not related to cell death (Supplemental Fig. 3), indicating that decreased IL2 production and proliferation upon re-stimulation of LAM-treated CD4+ T cells was not due to loss of T cell viability. Altogether these results exclude involvement of newly generated FoxP3+ cells, Tregs, secretion of inhibitory anergy-inducing cytokines, and apoptosis as causes of LAM-induced T cell anergy.

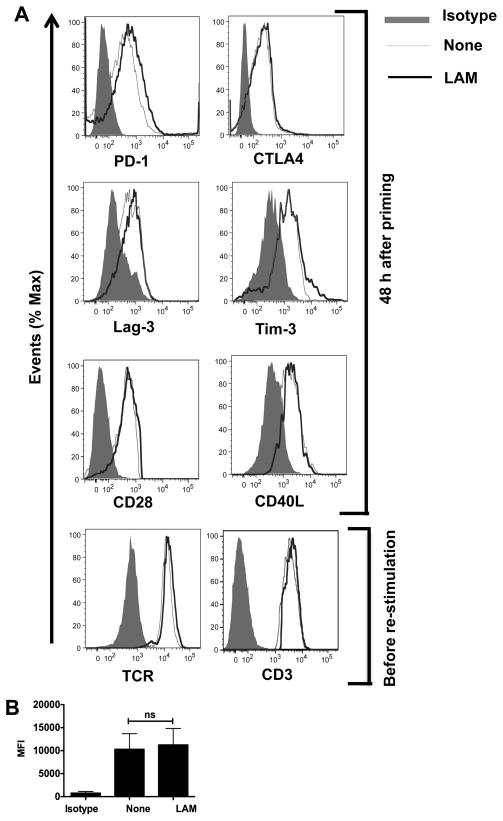

LAM does not affect TCR/CD3 and co-signaling receptor expression

Other pathways that have been associated with the initiation and/or promotion of T cell anergy are inhibitory receptors PD-1, CTLA-4, Lag-3 and Tim-3, that are induced after 48 h of T cell priming (20, 40–44). Previous reports have shown that intracellular pathogens can manipulate co-signaling molecules to evade the immune response (30). To determine if there was a role for these receptors in LAM-induced anergy, primary P25TCR-Tg T cells were stimulated with Ag85-pulsed BMM for 48 hours. This was followed by measurement of proliferation and surface expression of the aforementioned receptors. Although LAM-treated CD4+ T cells exhibited the expected decrease in proliferation, there was no significant increase in the expression of PD-1, CTLA-4, Lag-3 or Tim-3 in LAM-treated compared to non-treated T cells (Fig. 4A, upper histograms). CD28 is the co-stimulatory molecule essential for productive T cell activation, while CD40L also regulates T cell function and has been associated with up-regulation of the gene related to anergy in lymphocytes (GRAIL) (45). No differences in CD28 or CD40L expression in LAM treated vs. non-treated T cells were observed (Fig. 4A, lower histograms).

FIGURE 4.

LAM does not affect receptor expression on LAM-anergized P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells. (A) 1×106 CD4+ T cells were pre-treated with either LAM or left untreated (none) and co-cultured with Ag85B-pulsed APCs. After 48 h, cells were collected, washed and labeled with anti-PD1, anti-Lag3 or anti-Tim 3, anti-CD28, anti-CD40L mAbs. Intracellular staining was performed for CTLA4. Gating was performed on live CD4+ T cells. Alternatively, after 48 h cells were collected, washed and cultured in IL-7 for 5 d. Cells were then stained for surface expression of TCR and CD3. Gating was performed on live CD4+ T cells. Representative histograms of at least three independent experiments are shown. (B) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PD-1 staining in LAM-treated (LAM) and untreated (none) T cells was quantified after 48 h of primary stimulation. Data are means +/− SEM of three independent experiments.

An inhibitory environment may induce down-regulation of TCR-CD3 expression after priming, which could result in hypo-responsiveness at re-stimulation (46). At the time of Ag85B re-challenge, LAM-treated and non-treated CD4+ T cells had equivalent TCR and CD3 levels (Fig. 4A, lower histograms), indicating that decreased IL-2 production and proliferation upon re-stimulation in LAM-treated T cells was not due to endocytosis or internalization of the TCR-CD3 complex. The levels of IL-2Rα expression in LAM-treated and untreated T cells at re-stimulation were similar (data shown). Although we observed a small increase in PD-1 expression in LAM-treated T cells, the difference as compared to untreated T cells was not significant (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the slight increase in PD-1 expression cannot account for LAM-induced anergy.

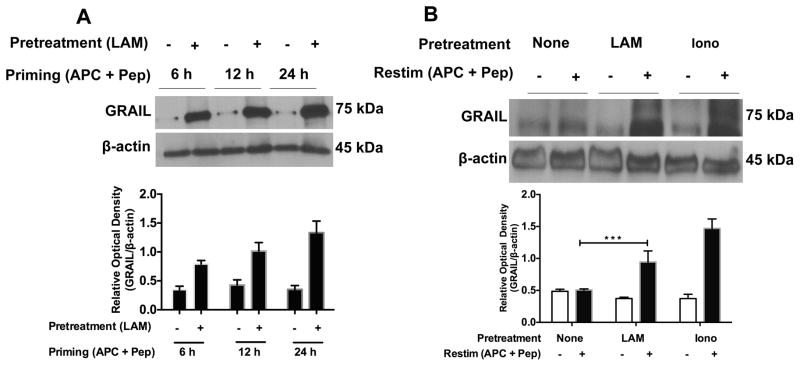

LAM-induced anergy correlates with up-regulation of GRAIL protein expression

The initiation and maintenance of CD4+ T cell anergy has been associated with increased expression of anergy-related genes, including GRAIL (24–26, 32, 45). GRAIL is a protein involved in induction and maintenance of CD4+ T cell anergy by negatively regulating IL-2 transcription (22, 24, 26, 27). GRAIL is inducible upon stimulation of peripheral CD4+ T cells, and increased expression may occur as early as 3 to 6 h (26). Therefore, we examined whether LAM-treated CD4+ T cells display elevated expression levels of GRAIL 6, 12 and 24 h after priming and 24 h after re-stimulation. Significant up-regulation of GRAIL protein in LAM-treated T cells was observed both after priming (Fig. 5A) and upon re-stimulation (Fig. 5B), which correlated inversely with the ability of the T cells to produce IL-2 (data not shown). These data suggest that the initiation and maintenance of anergy in LAM-treated T cells is associated with increased expression of GRAIL upon T cell activation.

FIGURE 5.

LAM induces increased GRAIL protein expression both during priming and upon re-stimulation. (A) Untreated and LAM-pre-treated P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells were stimulated with Ag85B peptide-pulsed APC for the indicated times. GRAIL protein expression was measured in cell lysates from re-purified CD4+ T cells by Western blot. Blots were analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH) and the ratios of band intensities of GRAIL/beta-actin expressed as relative densities (bar graph). (B) P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells were left untreated (none) or pretreated with LAM or ionomycin and primed with Ag85B peptide-pulsed APC. Cells were washed and cultured in IL-7 for 5 d. Cells were re-stimulated with Ag85B peptide-pulsed APC for 24 h. T cell lysates were obtained from re-stimulated CD4+ T cells, and Western blot performed for GRAIL protein. Data presented are the means +/− SEM of three independent experiments conducted in triplicate. ***P<0.001 (paired t test).

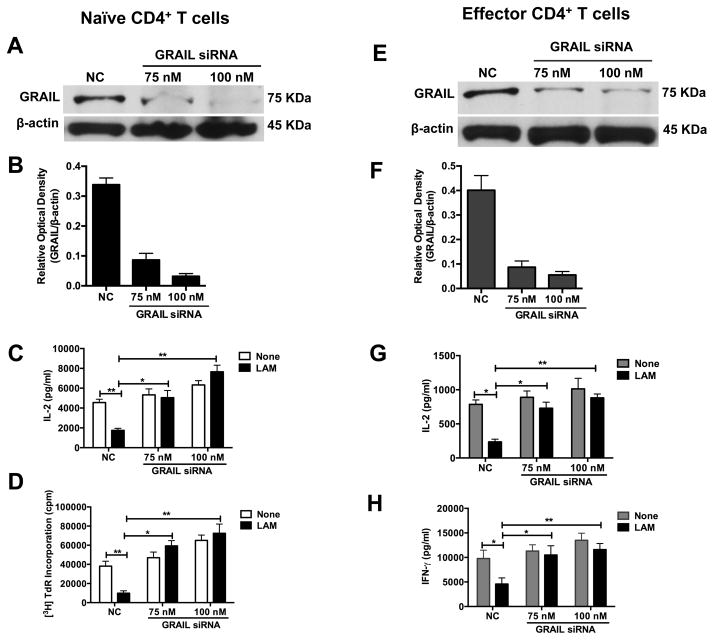

Knockdown of GRAIL expression reduces LAM’s ability to inhibit CD4+ T cell activation

GRAIL deficient T cells hyper-proliferate upon stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 and are defective in anergy induction (22, 24, 32). Optimal up-regulation of GRAIL occurred within 6 h to 24 h after LAM pretreatment and primary T cell stimulation (Fig. 5A). To test if GRAIL up-regulation was responsible for LAM-induced anergy, we knocked down GRAIL expression in pre-activated naïve CD4+ T cells before LAM pretreatment and anti-CD3/CD28 re-stimulation. As shown in Fig. 6A and 6B, the knockdown efficiency of GRAIL siRNA was approximately 75 to 92%. As a result of GRAIL knockdown, LAM’s ability to induce anergy was significantly reduced as shown by the reversal of the IL2 (Fig. 6C) and proliferation (Fig. 6D) defects in cells transfected with GRAIL siRNA compared to cells transfected with non-targeting siRNA (NC). GRAIL knockdown also resulted in an increase in IL-2 and cell proliferation in untreated cells, although the effect was not as significant as that observed in LAM-treated cells.

FIGURE 6. Knockdown of GRAIL expression by siRNA prevents inhibition of CD4+ T cell activation by LAM.

(A, B) A total of 3×106 pre-activated naïve CD4+ T cells plated at 3×105 cells per well in a 24-well plate were transfected with 75 nM or 100 nM of siRNAs targeting GRAIL (GRAIL siRNA) or non-targeting control siRNA (NC) using 6 μl HiPerfect dissolved in serum-free Opti-MEM medium. After 6 h of transfection, an additional 400 μl DMEM medium with 10% FBS was added and cells allowed to incubate at 37°C for 24 h. After 24 h, GRAIL was measured by Western blot with β-actin as loading control. (C, D) GRAIL knocked-down or control naïve CD4+ T cells were left untreated (None) or treated with LAM for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed and re-stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε and soluble anti-CD28 for 48 h. IL-2 was measured in 24 h culture supernatants by ELISA (C) and T cell proliferation after 48 h by [3H] thymidine incorporation (D). For A-D, representative blots and densitometry data are shown. (E, F) A total of 3×106 Th1 effector CD4+ T cells plated at 3×105 cells per well in a 24-well plate were transfected and cultured as in (A, B) above. After 24 h, GRAIL was measured by Western blot. (G, H) GRAIL knocked down or control Th1 effector CD4+ T cells were left untreated (None) or treated with LAM for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed and re-stimulated as above for 48 h. IL-2 (G) and IFN-γ (H) were measured in 24 h and 72 h culture supernatants respectively by ELISA. IL-2 and proliferation data shown are means +/− SEM of three independent experiments. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 (paired t test)

GRAIL is not only expressed in naïve T cells, but also in effector T cell subsets and controls their activation. Kriegel et al reported that Grail knockout Th1 effector CD4+ T cells overproduce IFN-γ. We reported previously that LAM inhibits activation of effector T cells (13). To determine whether LAM can induce anergy in effector T cells, GRAIL expression was knocked down by siRNA in in vitro differentiated Th1 effector CD4+ T cells. The knockdown efficiency of GRAIL siRNA in Th1 effector CD4+ T cells was 75 to 86% (Fig. 6E and Fig. 6F). After GRAIL knockdown Th1 cells and control cells were pre-treated with LAM before anti-CD3/CD28 re-stimulation. There was reversal of IL-2 and IFN-γ inhibition by LAM in GRAIL deficient-T cells compared to control Th1 cells (Fig. 6G and Fig. 6H). As observed with naïve T cells, there was a modest effect of GRAIL knockdown on spontaneous IL-2 and IFN-γ production in untreated T cells compared to the large effect on LAM-treated cells. These results indicate that GRAIL is not only a gatekeeper of T cell activation, but GRAIL expression is essential for LAM-induced inhibition of primary activation of naïve and effector CD4+ T cells and thus anergy.

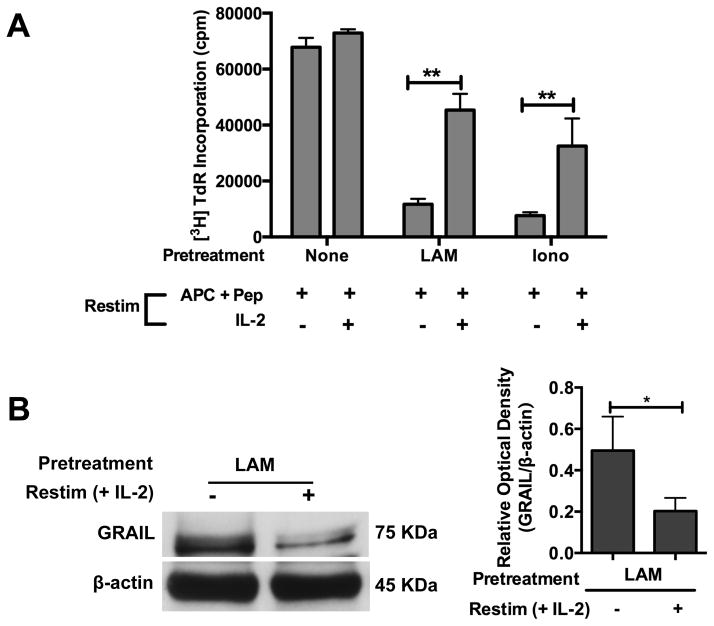

Exogenous IL-2 reverses LAM-induced anergy and down-regulates GRAIL in antigen-specific CD4+ T cells

Anergy in CD4+ T cells can be reversed by the addition of high concentrations of exogenous IL-2 at the time of re-stimulation (20, 47). P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells pretreated with LAM (1 μM) or ionomycin (1 μM) were primed and rested for 5 days in media containing IL-7. Cells were re-stimulated with Ag85B peptide-pulsed paraformaldehyde-fixed APC with or without exogenous IL-2. Exogenous IL-2 at time of re-stimulation partially restored proliferation in LAM-anergized CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7A), and this was comparable to reversal of ionomycin-induced anergy.

FIGURE 7. Exogenous IL-2 down-regulates GRAIL expression and restores T cell proliferation in LAM-anergized CD4+ T cells.

(A) P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells (1×106) were left untreated (none) or treated with LAM (1 μM) or ionomycin (1 μM) for 1 h. Cells were washed and primed with Ag85B peptide-pulsed APC. After 48 h, cells were washed and rested in media containing IL-7 for 5 days. CD4+ T cells were washed and re-stimulated with Ag85B peptide-pulsed APC with or without addition of exogenous rIL-2 (20 ng/ml). Cell proliferation was measured after 48 h by [3H] thymidine incorporation. Data are means +/− SEM of three independent experiments conducted in triplicates. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 (paired t test). (B) P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells were pretreated with LAM and primed with Ag85B peptide-pulsed APC. Cells were washed and cultured in IL-7 for 5 d. Cells were re-stimulated with Ag85B peptide-pulsed APC with or without addition of exogenous rIL-2 (20 ng/ml) for 48 h. T cell lysates were obtained and GRAIL protein measured by Western blot. A representative blot and densitometry for 3 experiments is shown.

IL-2 can down-regulate GRAIL expression (22). We determined the effect of exogenous IL2 on GRAIL expression in LAM-anergized T cells. P25 TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells pretreated with LAM were primed and rested as described above. Cells were re-stimulated with Ag85B peptide-pulsed paraformaldehyde-fixed APC with or without exogenous IL-2. Addition of IL2 resulted in decreased GRAIL expression by Western blot (Fig. 7B), which correlated with reversal of defective proliferation. Thus exogenous IL2 reversed LAM-induced anergy by down-regulating GRAIL expression.

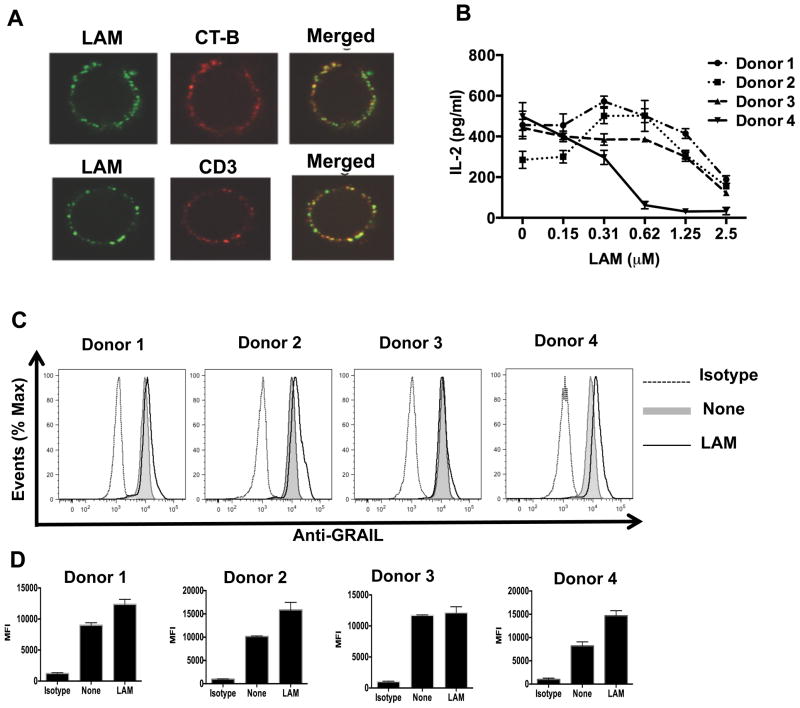

LAM pretreatment up-regulates GRAIL expression in activated human CD4+ T cells

Anergy-inducing proteins have been reported in both mouse and human anergized CD4+ T cells (29, 26). Since LAM also inhibits human CD4+ T cell activation (14), we first determined if LAM binds to resting human CD4+ T cell membranes. We used confocal microscopy to analyze LAM pretreated T cells labeled with anti-LAM mAb and with either lipid raft marker, Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated cholera toxin subunit B or CD3-TCR complex marker, Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated anti-CD3 mAb. This revealed that LAM was not only bound to the T cell membrane, but also associated with lipid rafts and the CD3-TCR complex (Fig. 8A). We next determined if LAM pretreatment of human CD4+ T cells induces GRAIL expression upon stimulation. One hour after LAM pretreatment, CD4+ T cells from four different donors were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 in the presence of a wide range of LAM concentrations for 24 h, followed by measurement of IL-2 levels by ELISA and flow cytometry for intracellular GRAIL protein expression. As shown (Fig. 8B), all individuals were inhibited albeit with variable sensitivity to LAM. GRAIL expression also was clearly up-regulated in LAM-treated T cells compared to untreated T cells from 3 donors (Fig. 8C and 8D) and minimally in 1 donor, indicating that LAM may induce anergy in human CD4+ T cells. These results suggest in this small pool of donors that there may be variable sensitivity of human CD4+ T cells to LAM’s inhibitory effect and ability to up-regulate GRAIL.

FIGURE 8.

LAM associates with lipid rafts and CD3 on human CD4+ T cells, and up-regulates GRAIL upon activation with anti-CD3/CD28. (A) Human CD4+ T cells were incubated with LAM for 1 h at 37°C. Top panels, after incubation with LAM, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated-cholera toxin subunit B (CT-B, 1 μg/ml) for 20 min on ice, washed extensively, labeled with anti-LAM mAb (clone Cs35) followed by Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated anti-mouse IgG and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Lower panels, after incubation with LAM, cells were labeled on ice with anti-LAM mAb (clone Cs35) followed by Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated-anti-mouse IgG. Then, Alexa Fluor 647 congugated-anti-CD3 mAb was used to label the CD3-TCR complex. Cells were visualized and images merged in a Leica DM16000B confocal microscope (100X oil immersion lens). (B) Human CD4+ T cells isolated from four different Mtb uninfected adult donors were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 in the presence of indicated LAM concentrations for 24 h, followed by measurement of IL-2 levels by ELISA. (C) Human CD4+ T cells (1×106) were left untreated (none) or pretreated with LAM (1 μM), followed by stimulation as above. Cells were stained for surface CD4 and intracellular GRAIL using APC-CD4 mAb and rabbit anti-GRAIL primary antibody, respectively. FITC-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used, followed by FACS analysis. (D) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of GRAIL staining in LAM-treated (LAM) and untreated (none) T cells was quantified after 48 h of primary stimulation. Error bars indicate mean +/− SD of triplicate wells of one representative experiment.

Discussion

LAM can incorporate itself into the membrane of CD4+ T cells within 30 min of exposure to soluble LAM (16, 17). We have reported before that Mtb LAM directly inhibits early TCR signaling in CD4+ T cells by blocking ZAP-70, CD3ζ Lck and LAT phosphorylation and that this inhibition is rapid (14). In this study, we established that LAM-induced inhibition of CD4+ T cell activation is not an isolated event from which T-cells easily recover, but rather a powerful anergizing stimulus with long-term functional consequences. As shown with other T-cell anergy inducing molecules, anergy induction required the presence of LAM in the T cell membrane at the time of primary stimulation, but LAM was not required during the re-stimulation step that revealed the T-cell anergic state. While several T-cell anergy models have been described before, this study is the first demonstration of anergy induction by a microbial glycolipid in the context of primary T-cell activation by a strong agonist antigen.

Anergy induction is thought to occur in two steps: First, an anergizing molecule elicits suboptimal or partial activation of the T cell. Second, the sub-optimally activated T cell undergoes a state of hypo-responsiveness and becomes refractory to re-stimulation (47, 48). Our results demonstrate that LAM first inhibits primary activation, which is followed by hypo-responsiveness upon optimal re-stimulation with an immunogenic antigen. Anergy induction and maintenance correlated with increased expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase, GRAIL in both mouse and human CD4+ T cells. GRAIL is an anergy-related gene whose increased expression has been shown to down-regulate IL-2 transcription (22, 24, 26). These findings indicate that following blockade of proximal TCR signaling and activation, as reported previously, LAM inhibition of T cells facilitates induction of anergy-related genes that render T cells hypo-responsive to optimal re-stimulation, resulting in long-term CD4+ T cell dysfunction. Whether such a biological phenomenon occurs in vivo and could be responsible for the delayed response to mycobacterial antigens characteristic of Mtb infection needs to be determined.

A previous study demonstrated that LAM can be detected by immuno-histochemical staining on macrophages and lymphocytes isolated from the lungs and spleens of Mtb infected mice (49). Moreover, exogenous administration of LAM by intravenous injection of mice revealed that LAM was distributed to splenic immune cells (50). In further support of LAM association with immune cells, our results demonstrated that LAM pretreatment of human CD4+ T cells not only results in LAM binding to T cell membranes, but also associates with lipid rafts and the CD3-TCR complex. This strengthens the model of LAM insertion into the T-cell membrane via its lipid moieties, although further studies are necessary to exclude a specific receptor for LAM on T cells. A recent report suggests that the lack of mannose cap in M. tuberculosis LAM does not affect its virulence in vivo or its interaction with macrophages in vitro (51). Although we did not examine the molecular structure of LAM to determine which parts of the molecule are necessary for its interaction and/or inhibitory effects on T cells, we assessed the effects of related mycobacterial lipolgycans including PILAM from M. smegmatis and lipomannan (LM) which lack a mannose cap, but have a similar lipid structure as LAM from M. tuberculosis. Whereas PILAM exhibited slight inhibition at high concentrations, LM was stimulatory for CD4+ T cells (unpublished data), suggesting that the lipid moieties are necessary, but not sufficient for LAM’s interaction with and inhibitory effects on T cells.

Most studies of T cell anergy established that anergy results from TCR stimulation in an inhibitory environment including increased co-inhibition or decreased co-stimulation, or TCR engagement with a weak agonist peptide such as altered- or self-peptides (20). Others have shown that T cell anergy results from persistent agonist antigen stimulation (36). We did not observe differences in expression of co-stimulatory receptor, CD28 or co-inhibitory receptors, PD1, CTLA4, Lag-3 and Tim-3 between LAM-treated and untreated T cells. Therefore, modulation of the aforementioned co-signaling receptors were not responsible for T-cell anergy induction in our model. Instead, our results reveal a novel mechanism of T-cell anergy induction in which the association of LAM with the T cell membrane at the time of primary TCR engagement by strong agonistic antigen triggers a hypo-responsive state. At the moment, it is not clear if LAM-induced anergy results from direct interference with TCR signaling, TCR membrane mobility, T cell-APC conjugate formation or a combination of effects. Further studies will establish if the presence of LAM in T cell membranes physically interferes with the formation of an effective immunological synapse upon stimulation, resulting in incomplete activation.

Additional studies are needed to understand how LAM inhibition of T-cell activation leads to anergy via GRAIL. A separate study in our laboratory using proteomics to determine the effects of LAM on CD4+ T cell activation revealed down-regulation of Otub-1 in LAM-treated T cells (Karim AF, unpublished). Otub-1, regulated by the Akt-mTOR pathway, is a known negative regulator of GRAIL function (25, 26). This suggests that LAM may disrupt the Akt-mTOR pathway resulting in Otub-1 down-regulation, which in turn may induce GRAIL. CD3 and CD40L are targets of GRAIL regulation. Up-regulation of GRAIL in T cells led to degradation of CD3 (46), whereas ectopic expression of GRAIL in naïve T cells from CD40−/− mice resulted in down-regulation of CD40L (45). However, we did not find differences in CD3− or CD40L- expression between LAM-treated and non-treated T cells. Our data do not support a model of LAM anergy induction by GRAIL-mediated- CD3− or CD40L- down-regulation, which may be due to differences in experimental set-up and/or the ligand used to induce anergy. GRAIL can be upregulated in FoxP3-positive regulatory cells, and is sufficient to convert T cells to a regulatory phenotype. Tregs also can mediate suppression by inducing anergy in conventional CD4+ T cells through secretion of anergizing cytokines such as IL-10 (25, 52). We found no evidence for up-regulation of FoxP3 or induction of Tregs by LAM during priming and re-stimulation of purified CD4+ T cells. Removal of nTregs had no impact on LAM’s ability to induce CD4+ T cell anergy. Thus, Tregs were not responsible for the T-cell anergy induction observed. We did demonstrate that exogenous IL2 down-regulates GRAIL expression in LAM anergized CD4+ T cells and restores the proliferative ability of these anergized T cells. This is consistent with a recent report by Aziz et al. demonstrating inhibition of GRAIL by IL-2 in anergized T cells (22).

We have shown previously that LAM inhibits activation of naïve and effector CD4+ T cells, in addition to pre-activated T cells (13, 14). Our current studies demonstrate the development of anergy when LAM is present during priming of naïve T cells, which may occur in secondary lymphoid tissues where the bacteria may be few. In addition we also show that effector T cells are similarly affected, suggesting that such an event may happen at the site of infection in the lungs where the bacterial loads are higher. Altogether, these findings suggest that LAM can interfere with CD4+ T cell function at different differentiation and activation states during Mtb infection and disease.

Previous and current results demonstrate T cell inhibition over a wide range of LAM concentrations down to 100 nM. The concentration of LAM in the immediate microenvironment of extracellular or intracellular Mtb is difficult to determine. However recent studies by others and our group indicate that small vesicles produced by Mtb alone (microvesicles) or released by infected cells (exosomes) contain large amounts of LAM in addition to other mycobacterial molecules (12, 53, 54). These microvesicles may represent efficient means to deliver LAM to T cells in the immediate environment of Mtb infected cells.

In addition to its importance in cancer, autoimmunity and organ transplantation, T cell anergy is a mechanism of immune evasion in chronic infections due to HIV-1 and Schistosoma mansoni (29, 31). In these infections T cell anergy was caused by protein antigens. Modulation of host immunity by glycolipids is rare except among intracellular pathogens such as trypanosomes and leishmanial species. Besides LAM, the only other microbial glycolipid known to directly inhibit T cell activation is trypanosomal glycoinositolphospholipids (GIPL) (55). Whether these pathogen glycolipids induce anergy is unknown. To our knowledge we are the first to show that a microbial glycolipid directly induces CD4+ T cell anergy by interfering with proximal TCR signaling.

In summary, we established a novel link between LAM association with the T cell membrane, LAM-induced T cell anergy and the expression of GRAIL in CD4+ T cells. It would be important to extend these studies to answer the following questions: 1) What are GRAIL’s targets in LAM-anergized T cells? 2) Can LAM be detected on T cells in vivo, and on T cells from active or latent TB patients, and are these T cells anergic? 3) How efficient are LAM-laden Mtb microvesicles from Mtb-infected macrophages in transferring LAM to T cells? 4) Could differential sensitivity to LAM inhibition of T cells explain the heterogeneous clinical manifestations of Mtb infection or the differential susceptibility to TB reactivation among humans? A recent report suggests that anergy induction in CD4+ T cells favors HIV-1 replication (29). It will be important to explore the biology and implications of LAM-anergized CD4+ T cells in Mtb infection or disease, and TB/HIV co-infection. Finally, these data provide novel insight into how CD4+ T cells despite sensitization to a broad repertoire of Mtb antigens may not respond optimally to their cognate antigens. T cell immune evasion strategies likely contribute to the host’s inability to eliminate Mtb and allow it to survive in the heart of a robust cellular immune system of macrophages and T cells such as the granuloma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Reba for technical assistance. We appreciate core facility support from Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals Center for AIDS Research and Case Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Grant Support

This work was supported by the following National Institutes of Health grants: D43-TW000011 and D43-TW00970 (Fogarty International Center; to OJS); R21 AI099494 (to RER); R01 AI069085 and R01 AI034343 (to CVH); D43-TW009780, AI027243, HL055967, and Contract No. HHSN266200700022C/NO1-AI-70022 for the Tuberculosis Research Unit (TBRU) (to WHB). Portions of this research were made possible with the resources of the Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals Center for AIDS Research (CWRU/UH-CFAR) NIH P30 AI036219, and Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, NIH P30 CA043703.

References

- 1.Commandeur S, van Meijgaarden KE, Prins C, Pichugin AV, Dijkman K, van den Eeden SJ, Friggen AH, Franken KL, Dolganov G, Kramnik I, Schoolnik GK, Oftung F, Korsvold GE, Geluk A, Ottenhoff TH. An unbiased genome-wide Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene expression approach to discover antigens targeted by human T cells expressed during pulmonary infection. J immunol. 2013;190:1659–1671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindestam Arlehamn CS, Gerasimova A, Mele F, Henderson R, Swann J, Greenbaum JA, Kim Y, Sidney J, James EA, Taplitz R, McKinney DM, Kwok WW, Grey H, Sallusto F, Peters B, Sette A. Memory T cells in latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection are directed against three antigenic islands and largely contained in a CXCR3+CCR6+ Th1 subset. PLoS Pathogens. 2013;9:e1003130. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindestam Arlehamn CS, Paul S, Mele F, Huang C, Greenbaum JA, Vita R, Sidney J, Peters B, Sallusto F, Sette A. Immunological consequences of intragenus conservation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis T-cell epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E147–155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416537112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutherland JS, Lalor MK, Black GF, Ambrose LR, Loxton AG, Chegou NN, Kassa D. Analysis of Host Responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis Antigens in a Multi-Site Study of Subjects with Different TB and HIV Infection States in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e74080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comas I, Chakravartti J, Small PM, Galagan J, Niemann S, Kremer K, Ernst JD, Gagneux S. Human T cell epitopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are evolutionarily hyperconserved. Nat Genet. 2010;42:498–503. doi: 10.1038/ng.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatt K, Salgame P. Host innate immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J clin immunol. 2007;27:347–362. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gehring AJ, Dobos KM, Belisle JT, Harding CV, Boom WH. Mycobacterium tuberculosis LprG (Rv1411c): A Novel TLR-2 Ligand That Inhibits Human Macrophage Class II MHC Antigen Processing. J Immunol. 2004;173:2660–2668. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harding CV, Boom WH. Regulation of antigen presentation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a role for Toll-like receptors. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:296–307. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs M, Togbe D, Fremond C, Samarina A, Allie N, Botha T, Carlos D, Parida SK, Grivennikov S, Nedospasov S, Monteiro A, Le Bert M, Quesniaux V, Ryffel B. Tumor necrosis factor is critical to control tuberculosis infection. Microbes infect. 2007;9:623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noss EH, Pai RK, Sellati TJ, Radolf JD, Belisle J, Golenbock DT, Boom WH, Harding CV. Toll-Like Receptor 2-Dependent Inhibition of Macrophage Class II MHC Expression and Antigen Processing by 19-kDa Lipoprotein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2001;167:910–918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pecora ND, Gehring AJ, Canaday DH, Boom WH, Harding CV. Mycobacterium tuberculosis LprA Is a Lipoprotein Agonist of TLR2 That Regulates Innate Immunity and APC Function. J Immunol. 2006;177:422–429. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Athman JJ, Wang Y, McDonald DJ, Boom WH, Harding CV, Wearsch PA. Bacterial Membrane Vesicles Mediate the Release of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Lipoglycans and Lipoproteins from Infected Macrophages. J immunol. 2015;195:1044–1053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahon RN, Rojas RE, Fulton SA, Franko JL, Harding CV, Boom WH. Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall glycolipids directly inhibit CD4+ T-cell activation by interfering with proximal T-cell-receptor signaling. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4574–4583. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00222-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahon RN, Sande OJ, Rojas RE, Levine AD, Harding CV, Boom WH. Mycobacterium tuberculosis ManLAM inhibits T-cell-receptor signaling by interference with ZAP-70, Lck and LAT phosphorylation. Cell Immunol. 2012;275:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briken V, Porcelli SA, Besra GS, Kremer L. Mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan and related lipoglycans: from biogenesis to modulation of the immune response. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:391–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shabaana AK, Kulangara K, Semac I, Parel Y, Ilangumaran S, Dharmalingam K, Chizzolini C, Hoessli DC. Mycobacterial lipoarabinomannans modulate cytokine production in human T helper cells by interfering with raft/microdomain signalling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4404-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subburaj I, Ami S, Poincelet M, Jean-Marc T, Brennan Nasir-ud-Din PJ, Hoessli DC. Integration of Mycobacterial Lipoarabinomannans into Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Rich Domains of Lymphomonocytic Cell Plasma Membranes. J Immunol. 1995;155:1334–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welin A, Winberg ME, Abdalla H, Sarndahl E, Rasmusson B, Stendahl O, Lerm M. Incorporation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan into macrophage membrane rafts is a prerequisite for the phagosomal maturation block. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2882–2887. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01549-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chappert P, Schwartz RH. Induction of T cell anergy: integration of environmental cues and infectious tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz RH. T cell anergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiodetti L, Choi S, Barber DL, Schwartz RH. Adaptive Tolerance and Clonal Anergy Are Distinct Biochemical States. J Immunol. 2006;176:2279–2291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aziz M, Yang WL, Matsuo S, Sharma A, Zhou M, Wang P. Upregulation of GRAIL is associated with impaired CD4 T cell proliferation in sepsis. J Immunol. 2014;192:2305–2314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi S, Schwartz RH. Molecular mechanisms for adaptive tolerance and other T cell anergy models. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:140–152. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kriegel MA, Rathinam C, Flavell RA. E3 ubiquitin ligase GRAIL controls primary T cell activation and oral tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16770–16775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908957106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whiting CC, Su LL, Lin JT, Fathman CG. GRAIL: a unique mediator of CD4 T-lymphocyte unresponsiveness. The FEBS J. 2011;278:47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07922.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin JT, Lineberry NB, Kattah MG, Su LL, Utz PJ, Fathman CG, Wu L. Naive CD4 t cell proliferation is controlled by mammalian target of rapamycin regulation of GRAIL expression. J Immunol. 2009;182:5919–5928. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ermann J, Szanya V, Ford GS, Paragas V, Fathman CG, Lejon K. CD4+CD25+ T Cells Facilitate the Induction of T Cell Anergy. J Immunol. 2001;167:4271–4275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bostik P, Mayne AE, Villinger F, Greenberg KP, Powell JD, Ansari AA. Relative Resistance in the Development of T Cell Anergy in CD4+ T Cells from Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Disease-Resistant Sooty Mangabeys. J Immunol. 2001;166:506–516. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dominguez-Villar M, Gautron AS, de Marcken M, Keller MJ, Hafler DA. TLR7 induces anergy in human CD4(+) T cells. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:118–128. doi: 10.1038/ni.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nargis K, Gowthaman U, Pahari S, Agrewala JN. Manipulation of Costimulatory Molecules by Intracellular Pathogens: Veni, Vidi, Vici!! PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8:e1002676. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith P, Walsh CM, Mangan NE, Fallon RE, Sayers JR, McKenzie ANJ, Fallon PG. Schistosoma mansoni Worms Induce Anergy of T Cells via Selective Up-Regulation of Programmed Death Ligand 1 on Macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;173:1240–1248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor JJ, Krawczyk CM, Mohrs M, Pearce EJ. Th2 cell hyporesponsiveness during chronic murine schistosomiasis is cell intrinsic and linked to GRAIL expression. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1019–1028. doi: 10.1172/JCI36534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura T, Ariga H, Kinashi T, Uehara S, Kikuchi T, Nakada M, Tokunaga T, Xu W, Kariyone A, Saito T, Kitamura T, Maxwell G, Takaki S, Takatsu K. The role of antigenic peptide in CD4+ T helper phenotype development in a T cell receptor transgenic model. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1691–1699. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lancioni CL, Li Q, Thomas JJ, Ding X, Thiel B, Drage MG, Pecora ND, Ziady AG, Shank S, Harding CV, Boom WH, Rojas RE. Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoproteins directly regulate human memory CD4(+) T cell activation via Toll-like receptors 1 and 2. Infect Immun. 2011;79:663–673. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00806-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hundt M, Tabata H, Jeon MS, Hayashi K, Tanaka Y, Krishna R, De Giorgio L, Liu YC, Fukata M, Altman A. Impaired activation and localization of LAT in anergic T cells as a consequence of a selective palmitoylation defect. Immunity. 2006;24:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolchinsky R, Hod-Marco M, Oved K, Shen-Orr SS, Bendall SC, Nolan GP, Reiter Y. Antigen-dependent integration of opposing proximal TCR-signaling cascades determines the functional fate of T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2014;192:2109–2119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barron L, Knoechel B, Lohr J, Abbas AK. Cutting Edge: Contributions of Apoptosis and Anergy to Systemic T Cell Tolerance. J Immunol. 2008;180:2762–2766. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Getts DR, McCarthy DP, Miller SD. Exploiting apoptosis for therapeutic tolerance induction. J Immunol. 2013;191:5341–5346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahic M, Henjum K, Yaqub S, Bjornbeth BA, Torgersen KM, Tasken K, Aandahl EM. Generation of highly suppressive adaptive CD8(+)CD25(+)FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells by continuous antigen stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:640–646. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chemnitz JM, Parry RV, Nichols KE, June CH, Riley JL. SHP-1 and SHP-2 Associate with Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-Based Switch Motif of Programmed Death 1 upon Primary Human T Cell Stimulation, but Only Receptor Ligation Prevents T Cell Activation. J Immunol. 2004;173:945–954. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chikuma S, Terawaki S, Hayashi T, Nabeshima R, Yoshida T, Shibayama S, Okazaki T, Honjo T. PD-1-mediated suppression of IL-2 production induces CD8+ T cell anergy in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;182:6682–6689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanchez-Fueyo A, Tian J, Picarella D, Domenig C, Zheng XX, Sabatos CA, Manlongat N, Bender O, Kamradt T, Kuchroo VK, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Coyle AJ, Strom TB. Tim-3 inhibits T helper type 1-mediated auto- and alloimmune responses and promotes immunological tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsushima F, Yao S, Shin T, Flies A, Flies S, Xu H, Tamada K, Pardoll DM, Chen L. Interaction between B7-H1 and PD-1 determines initiation and reversal of T-cell anergy. Blood. 2007;110:180–185. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-060087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lineberry NB, Su LL, Lin JT, Coffey GP, Seroogy CM, Fathman CG. Cutting Edge: The Transmembrane E3 Ligase GRAIL Ubiquitinates the Costimulatory Molecule CD40 Ligand during the Induction of T Cell Anergy. J Immunol. 2008;181:1622–1626. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nurieva RI, Zheng S, Jin W, Chung Y, Zhang Y, Martinez GJ, Reynolds JM, Wang SL, Lin X, Sun SC, Lozano G, Dong C. The E3 ubiquitin ligase GRAIL regulates T cell tolerance and regulatory T cell function by mediating T cell receptor-CD3 degradation. Immunity. 2010;32:670–680. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macian F, Garcıa-Cozar F, Sin-Hyeog I, Horton HF, Byrne MC, Rao A. Transcriptional Mechanisms Underlying Lymphocyte Tolerance. Cell. 2002;109:719–731. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00767-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wells AD, Walsh MC, Sankaran D, Turka LA. T Cell Effector Function and Anergy Avoidance Are Quantitatively Linked to Cell Division1. J Immunol. 2000;165:2432–2443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mustafa T, Phyu S, Nilsen R, Jonsson R, Bjune G. A Mouse Model for Slowly Progressive Primary Tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 1999;50:127–136. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glatman-Feedman A, Mednick AJ, Lendvai N, Casadevall A. Clearance and Organ Distribution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) in the Presence and Absence of LAM-Binding Immunoglobulin M. Infect Immun. 2000;68:335–341. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.335-341.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Afonso-Barroso A, Clark SO, Williams A, Rosa GT, Nobrega C, Silva-Gomes S, Vale-Costa S, Ummels R, Stoker N, Movahedzadeh F, van der Ley P, Sloots A, Cot M, Appelmelk BJ, Puzo G, Nigou J, Geurtsen J, Appelberg R. Lipoarabinomannan mannose caps do not affect mycobacterial virulence or the induction of protective immunity in experimental animal models of infection and have minimal impact on in vitro inflammatory responses. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:660–674. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vassiliki AB, Tsai EY, Yunis EJ, Thim S, Delgado JC, Dascher CC, Berezovskaya A, Rousset D, Jean-Marc R, Goldfeld AE. IL-10–producing T cells suppress immune responses in anergic tuberculosis patients. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1317–1325. doi: 10.1172/JCI9918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhatnagar S, Shinagawa K, Castellino FJ, Schorey JS. Exosomes released from macrophages infected with intracellular pathogens stimulate a proinflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2007;110:3234–3244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schorey JS, Cheng Y, Singh PP, Smith VL. Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO rep. 2015;16:24–43. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nitza AG, Poreviato JO, Zaingales B, Mendonca-Previato L, DosReis GA. Down-Regulation of T Lymphocyte Activation In Vitro and In Vivo Induced by Glycoinositolphospholipids from Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 1996;156:628–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.