Abstract

In the present study, we jointly employ and integrate variable- and person-centered approaches to identify groups of individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) who have similar profiles of change over a period of 10 years across three critical domains of functioning: maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms, and daily living skills. Two distinct developmental profiles were identified. Above and beyond demographic and individual characteristics, aspects of both the educational context (level of inclusion) and the family context (maternal positivity) were found to predict the likelihood of following a positive pattern of change. Implementing evidence-based interventions that target the school and home environments during childhood and adolescence may have lasting impacts on functioning into adulthood for individuals with ASD.

Keywords: Maladaptive behaviors, Autism symptoms, Daily living skills, Autism spectrum disorders, Adulthood, Longitudinal

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are characterized by qualitative impairments in social interaction and communication as well as restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests and activities (American Psychiatric Association 2013). ASD are typically diagnosed in childhood, yet these disorders are expected to endure indefinitely with challenges continuing throughout adulthood. Adults with ASD constitute a population with growing significance, given the increasing rate of diagnosis (Centers for Disease Control 2014; Charman 2002; Fombonne 2005). Improvements in medicine, public health and education that have resulted in an increased life expectancy for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) living in the United States and abroad (Coppus 2013; Davies and Higginson 2004).

Additional research is needed to understand the life course of ASD in order to develop appropriate interventions and systems of support. The availability of psychosocial interventions for adults with ASD is limited (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al. 2013). A deeper understanding of the phenotype in adulthood, and the contextual factors that may shape it, is necessary to improve the quality of the services provided to this population. Longitudinal research designs are necessary to chart the course of development and to identify antecedents of change (see Seltzer et al. 2004 for a review). By studying within-person change, longitudinal research designs can avoid or reduce the confound of differences in diagnostic and intervention practices across generations, which is often present in crosssectional studies. Many existing longitudinal studies have focused on small, clinically-referred samples, however, which limit the generalizability of the findings to individuals with ASD living in the community more broadly. To reduce this bias, the present study employed a sample of adolescents and adults recruited from community settings.

Adult Outcomes for Individuals with ASD

Historically, outcomes for individuals with ASD in adulthood were poor (Henninger and Taylor 2012; Levy and Perry 2011), but more recent longitudinal studies have documented improvements with age across several domains of functioning (Anderson et al. 2014; Seltzer et al. 2004). There are several domains of functioning that have broader impacts on opportunities for education, work, and independent living, including maladaptive behavior, autism symptom severity, and daily living skills (Lowe et al. 2007). Lifespan changes in these facets of functioning appear to be highly variable across studies and individuals, however, with some evidencing improvement while others show no improvement or even deterioration (Levy and Perry 2011).

Maladaptive behaviors are behaviors that interfere with everyday activities, including self-injurious, withdrawn, uncooperative, aggressive or destructive behaviors. Individuals with ASD have higher levels of maladaptive behaviors than their peers with other IDDs, from childhood through adulthood (Brereton et al. 2006; Totsika et al. 2011). Maladaptive behaviors generally improve with age among individuals with ASD (Einfeld et al. 2006; Howlin 2005; Matson and Horovitz 2010; Murphy et al. 2005; Shea and Mesibov 2005; Totsika et al. 2010), although improvement is not universally observed across studies. Within longitudinal studies, distinct patterns of change in maladaptive behaviors have been reported for individuals with ASD (Gray et al. 2012).

Change in the core symptoms diagnostic of ASD is an important focus of longitudinal research. Although most individuals diagnosed in childhood continue to meet criteria for ASD in adulthood (Billstedt et al. 2007; Howlin et al. 2004), there is longitudinal and crosssectional evidence to suggest age-related improvements in the severity of autism symptoms (Chowdhury et al. 2010; Esbensen et al. 2009; McGovern and Sigman 2005; Seltzer et al. 2004). Similar to maladaptive behaviors, longitudinal studies of autism symptoms have observed heterogeneous change. While many improve, some individuals with ASD show persistent or worsening autism symptoms into adulthood (Chowdhury et al. 2010; Fecteau et al. 2003).

Daily living skills represent a central component of adaptive behavior, a set of skills used on a daily basis that are related to general intelligence but provide a more nuanced representation of the strengths and limitations an individual demonstrates in everyday life (Paskiewicz 2009). The development of daily living skills may be particularly challenging for individuals with ASD, who show significant impairments compared to their peers without diagnosed disabilities (Liss et al. 2001; Perry et al. 2009). Individuals with ASD generally demonstrate improvement in daily living skills with age (Beadle-Brown et al. 2000, 2006; Chadwick et al. 2005a, b), however their rate of improvement may be slowed compared to their peers with other IDDs or no diagnosed disabilities (Beadle-Brown et al. 2000, 2006; Di Nuovo and Buono 2007; Matson et al. 2009).

Developmental Trajectories Among Individuals with ASD

In our previous work, we have examined change in maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms and daily living skills using data from a prospective, longitudinal study of adolescents and adults with ASD (Seltzer et al. 2003). Despite general trends toward improvement, a subset of 12 % of adults worsened (i.e., increased) in autism symptom severity and 11 % worsened (i.e., increased) in maladaptive behaviors over an 8.5 year period (Woodman et al. 2015). Over a 10 year period, rates of improvement in daily living skills in this sample were found to slow as adults reached their late 20s (Smith et al. 2012). Taken together, these studies suggest heterogeneity in patterns of change across adolescence and adulthood.

To date, our studies have relied on variable-centered approaches to describe within-person changes and between-person differences on individual outcomes. These analytic methods are well suited for research questions quantifying the impacts of individual and contextual factors on development, but they do not consider individual profiles across multiple domains of development (Laursen and Hoff 2006). An alternative class of techniques embraces a person-centered approach, which prioritizes a holistic view of an individual’s functioning. Proponents of person-oriented approaches argue that ‘‘the complex, dynamic processes of individual functioning and development cannot be understood by summing results from studies of single variables taken out and investigated in isolation from the context of other, simultaneous operating variables’’ (Magnuson 1998, p. 60). Analytic methods stemming from this view, such as latent profile analysis (LPA), aim to identify groups of individuals with similar values on a variety of outcomes (Schmiege et al. 2012). These approaches identify unique patterns across outcomes, yet are limited to indices of functioning measured at a single time point. Integrating variable-centered and person-centered analyses would provide a more complete understanding of lifespan change in the autism phenotype.

Individual Risk Factors

Several characteristics of individuals with ASD have been highlighted as critical predictors of long-term outcomes. Limitations in verbal abilities, more severe autism symptoms, the presence of ID, and female gender may set the stage for diminished growth in critical areas of functioning throughout adolescence and adulthood. The acquisition of language before age 5 has been found to predict better functioning in adulthood, including autism symptoms, adaptive behaviors and social skills (Magiati et al. 2014; Pickles et al. 2014). Greater autism-related impairments in childhood may predict poorer adult outcomes related to mental health, independent living, employment and social relations (Howlin et al. 2013). Individuals with ASD and comorbid ID are generally reported to have worse outcomes in adulthood than their peers with ASD without ID, including autism symptom severity (McGovern and Sigman 2005; Shattuck et al. 2007; Woodman et al. 2015), maladaptive behaviors (Gray et al. 2012; Shattuck et al. 2007; Woodman et al. 2015), and daily living skills (Beadle-Brown et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2012). Some studies have reported women with ASD to have poorer outcomes in adulthood (e.g., Billstedt et al. 2007), although the findings are mixed (Reinhardt et al. 2015).

Contextual Influences

Systems theories view development as the product of the dynamic relation between individuals and their contexts which changes over time (Sameroff 2010). The developing individual is embedded within multiple layers of context, including family, school, and community (Bronfenbrenner 1979, 1992). A nurturing and supportive family environment is central to promoting optimal outcomes, since many day-to-day interactions occur within this setting. One aspect of the family environment that appears particularly salient to the development of individuals with ASD is the level of maternal expressed emotion. Expressed emotion refers to a construct representing key aspects of interpersonal relationships in everyday life, including criticism, hostility, warmth, positive remarks and emotional overinvolvement (Wearden et al. 2000). Since expressed emotion is measured through parent narrative, this method reduces reliance on parent self-report that may lead to shared variance biases. Researchers have explored links between the components of expressed emotion and outcomes for individuals with ASD (Greenberg et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008; Woodman et al. under review).

Maternal critical and positive remarks are key dimensions of maternal expressed emotion. Criticism captures the extent to which the mother displays disapproval of her son or daughter. Criticism measured through parent narrative is associated with behavioral observations of antagonism, negativity, disgust, harshness and lower responsiveness in parent–child interactions (McCarty et al. 2004). Within families raising children with ASD, maternal criticism is predictive of behavior problems (Baker et al. 2011; Greenberg et al. 2006; Hastings et al. 2006) and autism symptom severity (Greenberg et al. 2006) in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Positive family processes may be equally influential on development. The number of positive remarks, or praise, measured through maternal narrative has been found to have positive impacts on autism-related impairments and maladaptive behaviors among adolescents and adults with ASD (Smith et al. 2008; Woodman et al. 2015).

As children age, the school environment becomes an increasingly salient context for development. Perhaps the most characteristic of the school environment for students with ASD is the extent to which they are included in general academic and social activities within the school. Inclusion in general education classrooms has been found to have positive impacts on adaptive behavior, academic achievement and social interactions for students with IDD (Hunt and McDonnell 2007). Few studies to date have considered the impact of inclusive education practices on the symptoms and behaviors characteristic of ASD. Moreover, the long-term effects of educational context on outcomes in adulthood remains underexplored for this population.

The Present Study

The first goal of this study was to jointly employ and integrate variable-centered and person-centered approaches to identify groups (or classes) of individuals with ASD who have similar profiles of change over a 10 year period on the domains of maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms, and daily living skills. The second goal was to identify individual characteristics and contextual factors that predict class membership. Based on past research, we expected that females with ASD and those who have comorbid ID would be less likely to belong to a class with desirable trajectories than males with ASD and those without comorbid ID. We further hypothesized that individuals who developed verbal language by age 4–5 would be more likely to follow a desirable developmental course through adulthood. As additional controls, we accounted for the influence of age, level of autism symptom severity at age 4–5, and maternal education. With respect to contextual factors, we predicted that, once all of the above characteristics are controlled, individuals who experienced partial or full inclusion in academic and social activities during their school years would be more likely to belong to a class with positive growth trajectories. Individuals with ASD who had mothers rated high in positive remarks and mothers rated low in critical remarks were expected to follow a desirable developmental course.

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from an ongoing, naturalistic observational longitudinal study of 406 individuals with ASD and their families, the Adolescents and Adults with Autism Study (Seltzer et al. 2003). Analyses in the present study used data from five waves of data collection spanning 10 years: wave 1 (1998–2000), wave 2 (2000–2001), wave 3 (2002–2003), wave 4 (2004–2005), wave 7 (2007–2008), and wave 8 (2009–2010). These time points will be referred to as Times 1–6 for the purposes of the present paper. Families were recruited in Massachusetts (N = 204) and Wisconsin (N = 202) through agencies, schools, diagnostic clinics and media announcements. Identical recruitment procedures were used in both states.

Families met three criteria at the start of the study: (1) the family included a child with an ASD diagnosis given by an independent medical, psychological, or educational professional, (2) the child with ASD was 10 years of age or older, and (3) the child’s scores on the research-administered autism diagnostic interview-revised (ADI-R; Lord et al. 1994) were consistent with an ASD diagnosis. Of the 406 participants, 384 (94.6 %) met criteria for autistic disorder on the ADI-R: qualitative impairments in communication and language, qualitative impairments in reciprocal social interaction, repetitive, restrictive, and stereotyped behaviors with an onset of symptoms prior to 36 months. The remaining 22 participants (5.4 %) demonstrated a pattern of impairment on the ADI-R that was consistent with a diagnosis of Asperger’s disorder or pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS).

The present sample consisted of 364 families for which at least two waves of data on the outcome variables were available. The majority of the participants were male (74 %) and 70 % had a comorbid diagnosis of ID. Participants ranged in age from 10 to 52 years (M = 21.85, SD = 9.42) at Time 1. More than half of participants (65 %) lived in the family home at the start of the study. Most parents were married (78 %) at that time. With respect to maternal education, 25 % had a high school degree or less, 22 % had some college, 21 % had an associate’s or bachelor’s degree and the remainder had advanced degrees. Maternal age ranged from 32 to 81 years (M = 50.75, SD = 10.45) at Time 1. More than half of mothers (66 %) were employed. Most mothers (94 %) identified as White. The median household income at the start of the study was $50,000–59,999. Descriptive statistics on adult and family factors measured at the start of the study are provided in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the analytic sample (n = 364) and the remaining families in the original sample (n = 42) with respect to maternal age, state of origin, household income, child age, and child gender.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for predictor variables

| Predictor | N | (%)a | M | (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 21.85 | (9.42) | ||

| Intellectual disability | ||||

| Yes | 256 | 70 | ||

| No | 108 | 30 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 270 | 74 | ||

| Female | 94 | 26 | ||

| Maternal education | ||||

| High school degree or less | 90 | 25 | ||

| Some college | 79 | 22 | ||

| Associates or bachelor’s degree | 76 | 21 | ||

| Post bachelor’s degree or graduate degree | 119 | 33 | ||

| Verbal language at age 4–5 | ||||

| Daily functional use of spontaneous or stereotyped language | 131 | 36 | ||

| No functional use of three word phrases, fewer than five words total, or speech not used daily | 233 | 64 | ||

| Autism symptoms at age 4–5 | 18.86 | (1.58) | ||

| Education context while in school | ||||

| No inclusion | 138 | 38 | ||

| Partial inclusion | 171 | 47 | ||

| Full inclusion | 55 | 15 | ||

| Maternal positive remarks | 2.15 | (2.17) | ||

| Maternal critical remarks | 0.31 | (0.82) |

Categories may not add to 100 % due to rounding

The study spanned over 10 years (1998–2010). Due to attrition, however, the average participant was followed for 8.22 years (SD = 3.07). More than half of families (56 %) participated in all six time points used in the present analyses. An additional 10 % participated in five time points, followed by 14 % with four time points, 10 % with three time points, and 10 % with two time points. Attrition cases and complete cases did not differ in their likelihood of class membership, therefore it does not appear to be the case that individuals with undesirable trajectories were more likely to drop out of the study.

Measures

The present analyses drew data from 6 time points. With respect to outcome variables, maladaptive behaviors and autism symptoms were assessed at each time point and daily living skills was assessed at Times 1, 4, 5, and 6. All of the adult and family factors that were included as predictor variables were measured at the start of the study (Time 1), although some relied on retrospective report. For instance, the extent of inclusion during school, the level of verbal language at age 4–5, and the extent of autism symptoms at age 4–5 were based on maternal retrospective reports at Time 1. Means and standard deviations are reported for outcome variables at each time point in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for outcome variables

| Time point | Age |

Range | Maladaptive behaviors |

Autism symptoms |

Daily living skills |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | ||

| 1 | 21.85 | (9.42) | 10.15–52.08 | 115.43 | (10.87) | 26.15 | (7.51) | 19.64 | (6.78) |

| 2 | 23.55 | (9.53) | 11.32–53.92 | 112.93 | (10.07) | 25.81 | (8.21) | – | – |

| 3 | 24.85 | (9.36) | 12.73–52.41 | 113.05 | (10.50) | 25.28 | (8.20) | – | – |

| 4 | 26.21 | (9.25) | 14.61–53.31 | 111.44 | (10.27) | 24.28 | (9.02) | 20.60 | (7.45) |

| 5 | 29.72 | (9.01) | 18.31–57.10 | 110.71 | (9.62) | 24.94 | (9.07) | 20.57 | (7.88) |

| 6 | 31.07 | (8.85) | 19.79–58.83 | 109.93 | (9.19) | 23.73 | (9.51) | 20.47 | (8.13) |

Family Characteristics

Maternal education was recorded at Time 1. For the present analyses, maternal education was coded as 1 = high school degree or less and 0 = more than high school degree and served as a predictor variable.

Child Characteristics

The age (in years) and gender (1 = female and 0 = male) of the adolescent or adult with ASD was recorded at Time 1. Use of verbal language during early childhood (age 4–5) was based on parent report on the ADI-R at Time 1. Participants were coded as having 1 = daily functional use of spontaneous or stereotyped language or 0 = no functional use of three word phrases, fewer than five words total, or speech was not used daily at age 4–5. Age, gender, and verbal language at age 4–5 served as predictors in this study.

Intellectual Disability

Individuals with standard scores of 70 or below on the Wide Range Intelligence Test (Glutting et al. 2000) and the Vineland Screener (Sparrow et al. 1993) were classified as having ID, consistent with diagnostic guidelines (Luckasson et al. 2002). For individuals with scores between 71 and 75, clinical consensus among three independent raters (one master’s level and two Ph.D. level clinical psychologists) was reached based on available records (e.g., standardized assessments, clinical and school records). Comorbid diagnosis of ID (1 = comorbid ID, 0 = no comorbid ID) was used as a predictor in this study.

Education Context

At Time 1, mothers were asked ‘‘during the time your son or daughter is/was in school, how would you describe his or her level of inclusion with peers who do not have disabilities?’’ Response options included ‘‘no inclusion in school for both academic and non-academic activities’’, ‘‘partial inclusion in school for either academic or non-academic activities’’, and ‘‘full inclusion in school for both academic and non-academic activities’’. Indicator variables were created for partial inclusion and full inclusion, with the reference category as no inclusion, and used as predictor variables.

Family Context

The Five Minute Speech Sample (FMSS) was used to code maternal positive and critical remarks at Time 2 based on the coding manual developed by Magaña et al. (1986). Mothers were asked to speak about their child with ASD for 5 min uninterrupted. The speech sample was taperecorded, transcribed, and coded for various components of expressed emotion. As part of the protocol for coding the FMSS, raters recorded the number of times a mother made a positive remark or a critical remark about her son or daughter. Ratings were performed by a coder blind to the study’s hypotheses with more than 20 years of experience in coding all aspects of expressed emotion. The number of positive remarks and the number of critical remarks were used as predictors in this study. The number of positive remarks ranged from 0 to 11 and the number of critical remarks ranged from 0 to 7. These variables were negatively correlated, r = −.13, p = .01.

Maladaptive Behaviors

Maladaptive behaviors were based on the Problem Behavior subscale of the Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised (Bruininks et al. 1996) at each time point. Mothers indicated the presence of maladaptive behaviors across three domains: internalized (hurtful to self, unusual or repetitive habits, withdrawn or inattentive behavior), externalized (hurtful to others, destructive to property, disruptive behavior) and asocial (socially offensive and uncooperative behavior). Each type of behavior problem was coded as manifested during the past 6 months (1) or not manifested (0). Parents who indicated that their son or daughter displayed a given behavior problem during the past 6 months then rated the frequency of the behavior, from 1 = less than once a month to 5 = one or more times/h, and the severity of the behavior, from 1 = not serious to 5 = extremely serious. Standardized algorithms (Bruininks et al. 1996) were used to translate the frequency and severity ratings into an overall maladaptive behavior score. Reliability and validity have been established by Bruininks et al. (1996). The overall maladaptive behavior score was used as an outcome in this study, with higher values indicating higher levels of maladaptive behavior.

Autism Symptoms

The ADI-R (Lord et al. 1994) was used to measure autism symptoms at each time point. The ADI-R was conducted as a standardized investigator-driven interview with the mother. Items on this measure are based on criteria for an autism diagnosis outlined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association 2000) and the International Classification of Diseases (World Health Organization 1987). Mothers were asked to report on their son or daughter’s current level of impairment at each time point. At time 1, mothers were also asked to retrospectively report on their son or daughter’s level of impairment during childhood. Items were coded as 0 = no abnormality present, 1 = possible abnormality, and 2 = definite abnormality across four primary symptom domains: repetitive behaviors and stereotyped interests, impairments in social reciprocity, impairments in non-verbal communication, and (for verbal participants only) impairments in verbal communication. Some items also contained a possible score of 3 = extreme abnormality.

Items on the verbal communication scale were excluded for this study since not all participants had verbal communication, including the item regarding overall level of verbal language. The count of autism symptoms (0 = absent, 1 = present) at age 4–5 served as a predictor variable in the present analyses, with values reflecting the number of impairments out of 25 total. To calculate level of autism symptoms from Time 1 to Time 6, values of 3 (extreme abnormality) were first recoded to 2 (definite abnormality) to retain consistency in scoring across items. Scores were summed across the 25 items so that greater values on the outcome variable represented greater autism symptom severity.

The interviewers who administered the ADI-R participated in an approved training program. Interrater reliability was high for individual items between two interviewers and two supervising Ph.D. clinical psychologists experienced in the diagnosis of autism and the use of the ADI-R. The ADI-R has demonstrated good test–retest reliability, diagnostic validity, convergent validity and specificity and sensitivity in past research (Hill et al. 2001; Lord et al. 1994).

Daily Living Skills

Independence in activities of daily living was measured at Times 1, 4, 5 and 6 using the Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale (W-ADL; Maenner et al. 2013). Mothers were asked to rate the independence of their son or daughter in 17 activities of daily living (e.g., prepare simple foods, grooming) on a three-point scale (0 = does not do at all, 1 = could do but does not/does with help, 2 = independent). The W-ADL has demonstrated strong internal consistency as well as criterion and construct validity for individuals with ID (Maenner et al. 2013). The total score served as an outcome in this study, with higher values indicating greater independence in activities of daily living.

Analytic Plan

Change in maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms, and daily living skills was first examined through hierarchical linear modeling using HLM software version 6 (Raudenbush et al. 2008). For each of these domains, unconditional growth models were conducted as a function of time in years. Time was centered at the first time point so that the intercepts would represent initial levels of functioning. Change in each domain was not modeled as a function of chronological age because participants were not the same age at the start of the study. Since age would need to be centered at a specific value for the HLM analyses (for example, 21.85 years to represent the mean age at Time 1), this value would not be meaningful for individuals who older or younger (e.g., 16- or 40-year-old). We elected to model change as a function of time so that the intercept would have meaning for all participants. Hierarchical linear modeling allows the number and spacing of observations to vary across individuals (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). Complete data on the outcome variable and equal spacing between observation time points is not required. The intercepts and linear slopes for each participant on each outcome were saved and entered as observed indicators in the LPA, resulting in six parameters total.

The LPA was conducted using MPlus version 7 (Muthén and Muthén 2010). LPA is a type of mixture modeling, a family of techniques in which individuals are classified into subpopulations based on heterogeneity in the data (Schmiege et al. 2012). Unlike cluster analysis, mixture modeling classifies individuals into groups based on latent, unobserved heterogeneity. In LPA, individuals with similar responses across a variety of observed indicators are grouped into the same class, while individuals with different responses are grouped into different classes. LPA provides estimates of each individual’s likelihood of membership in each class, unlike traditional cluster analysis approaches. These posterior probabilities can be used to estimate the precision of classification (Muthén 2001).

Classes were based on the growth parameters for maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms, and daily living skills derived from the unconditional growth models, with two growth parameters (intercept, linear slope) per outcome. Although some outcomes were defined by quadratic change, there was insufficient variability across individuals in rates of acceleration to permit the LPA models to converge. Therefore, each participant’s change over the study period was defined by initial levels and rates of linear change based on an additional set of hierarchical linear growth models. In estimating the LPA models, the intercept and slope within each outcome were permitted to correlate (e.g., intercept for ADI-R with slope for ADI-R). Growth parameters were not permitted to correlate across outcomes, such that neither the intercepts (e.g., intercept for ADI-R with intercept for SIB-R) nor slopes (e.g., slope for W-ADL with slope for ADI-R) across outcomes was permitted to correlate, as this reduced model fit. Model fit was determined using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the adjust Bayesian information criterion (ABIC), the Lo Mendell Rubenstein likelihood ratio test (LMR LRT), and entropy (Pastor et al. 2007).

Individuals were classified based on their posterior probabilities of membership. In other words, individuals were assigned to the class for which they had the highest posterior probability of membership. The likelihood of assignment to the class with the most desirable profile of change in functioning across the study period was compared to the likelihood of membership in other classes using logistic regression.

A variety of adult and family factors measured at the start of the study were included as predictor variables. Differences in the chronological age of the participants was statistically controlled. Additional predictors included demographic control variables (comorbid ID, gender, maternal education), controls for level of functioning in childhood (verbal language at age 4–5, autism symptoms at age 4–5), and variables related to the educational (level of inclusion while in school) and family (maternal positive remarks, maternal critical remarks) context. Missing data on predictor variables were imputed using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo procedure in SPSS version 19. Data were found to be missing completely at random (MCAR) using Little’s MCAR test, χ2 = 1.99, df = 3, p = .57. Overall, 5 % of values were missing. Results present estimates pooled across five imputed data sets, since it is recommended in the literature to impute at least one data set per percentage of data missing (White et al. 2011). Pooling results across multiple imputed data sets is recommended since excluding cases with missing data biases estimates and reduces statistical power (Widaman 2006).

Results

Unconditional Growth Models

Change in maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms, and daily living skills was first examined through hierarchical linear modeling. As seen in Table 3, trajectories of maladaptive behaviors followed a curvilinear pattern. Improvement was observed over the course of the study, as evidenced by declines in maladaptive behaviors, but rates of improvement slowed over time. There was significant variability between individuals in initial levels, linear, and quadratic change. Trajectories of autism symptoms were observed to follow a linear pattern, with rates of improvement constant across the study period. There was significant variability in initial levels and linear change in autism symptoms. Lastly, trajectories of daily living skills followed a curvilinear pattern. Overall, individuals improved over the course of the study, but rates of improvement slowed over time. There was significant variability between individuals in initial levels, linear, and quadratic change for daily living skills.

Table 3.

Unconditional growth models for maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms, and daily living skills

| Maladaptive behaviors b (SE) |

Autism symptoms b (SE) |

Daily living skills b (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | |||

| Intercept | 115.11 (0.55)*** | 26.08 (0.39)*** | 19.67 (0.36)*** |

| Linear slope | −1.00 (0.16)*** | −0.17 (0.04)*** | 0.34 (0.08)*** |

| Quadratic slope | 0.05 (0.01)*** | - | −0.03 (0.01)*** |

| Variance (SD) | Variance (SD) | Variance (SD) | |

| Random effects | |||

| Intercept | 85.30 (9.24)*** | 49.48 (7.03)*** | 42.11 (6.49)*** |

| Linear slope | 1.73 (1.32)*** | 0.23 (0.48)*** | 0.67 (0.82)*** |

| Quadratic slope | 0.01 (0.08)* | - | <0.01 (0.07)*** |

| Level-1 | 29.55 (5.44) | 12.79 (3.58) | 4.04 (2.01) |

p< .05;

p< .01;

p< .001

Latent Profile Analysis

Individuals were grouped into classes based on the parameters derived from the unconditional growth models (intercept, linear slope) for maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms, and daily living skills. A three-class solution based on these 6 indicators was marginally better than a two-class solution according to BIC (7657.85 vs. 7702.05) and AIC (7498.06 vs. 7592.93) values, but not entropy values (0.75 vs. 0.75). The LMR LRT indicated that a three-class solution did not significantly improve model fit compared to a two-class solution (p = .47), therefore a two-class solution was selected. A four-class solution included a group too small for meaningful analysis (<5 % of the sample). Overall, individuals were classified with high levels of precision in the two-class solution. The average posterior probability was 0.93 for the assigned class and 0.07 for the unassigned class. In other words, individuals were classified with 93 % confidence on average.

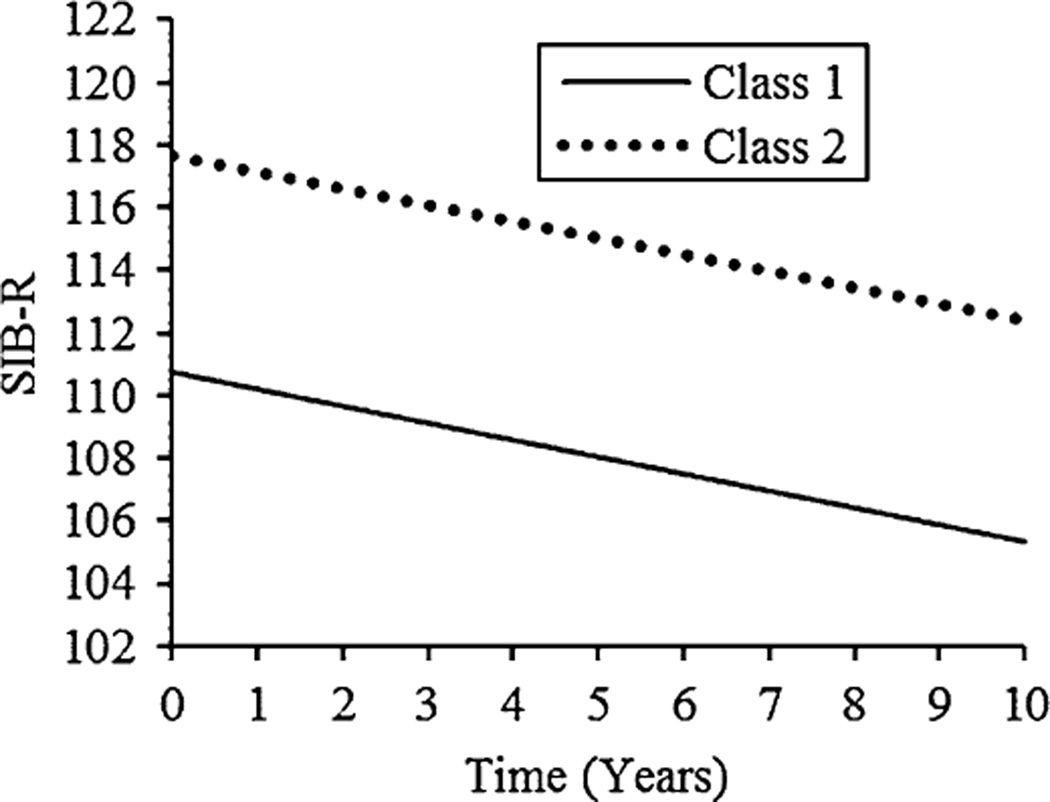

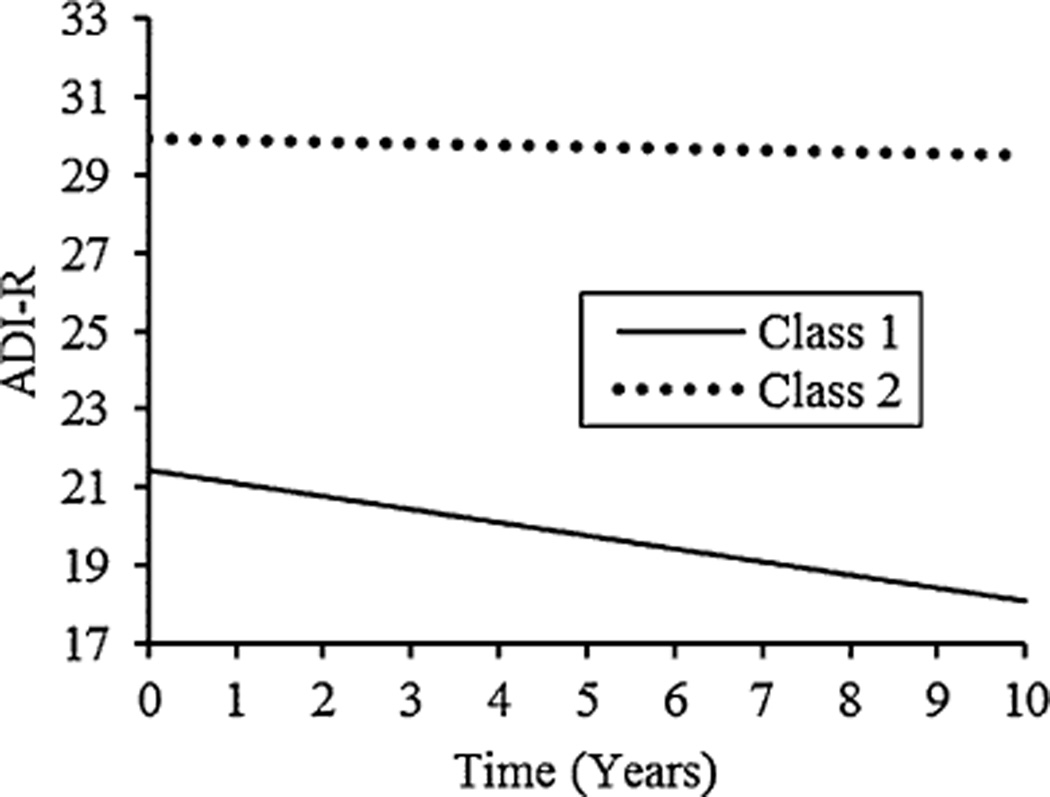

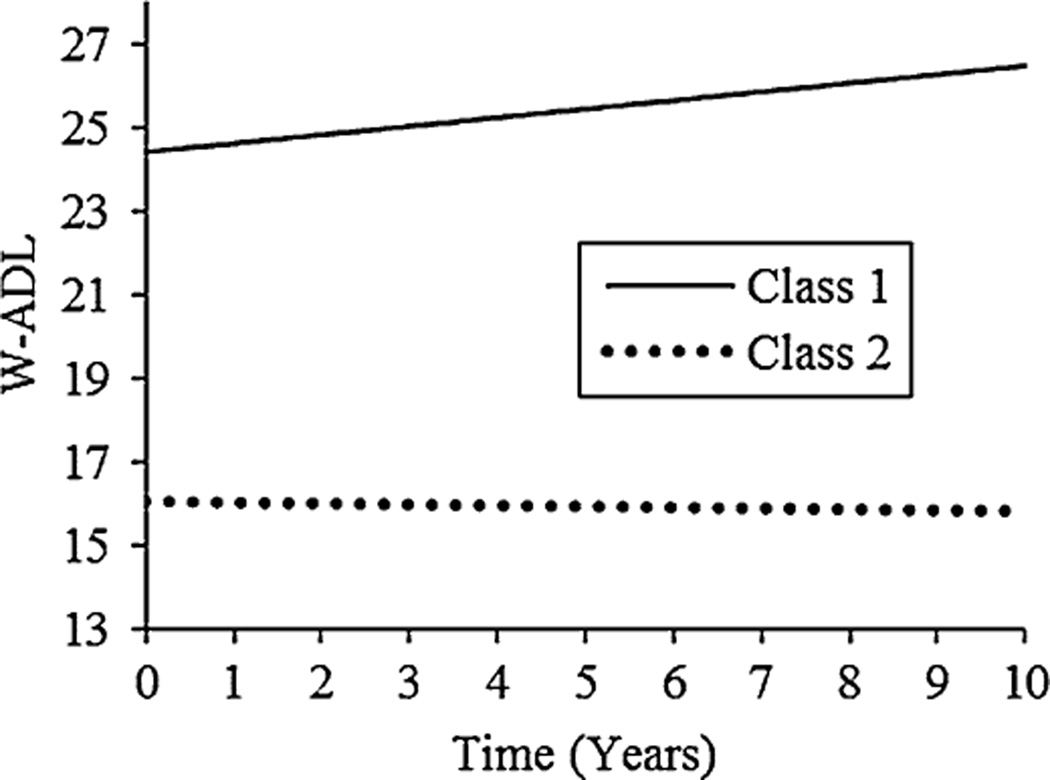

The results for the two-class solution are presented in Table 4. Individuals in Class 1 had significantly lower levels of maladaptive behaviors than individuals in Class 2 at the start of the study. Rates of change in maladaptive behaviors over the course of the study did not differ between classes. Autism symptoms at the start of the study were significantly lower (i.e., fewer symptoms) for individuals in Class 1 than Class 2. Individuals in Class 1 also displayed greater improvements in autism symptoms over time, as evidenced by a significantly faster rate of decline than Class 2. Lastly, individuals in Class 1 had significantly higher levels of daily living skills at the start of the study. These individuals also evidenced faster improvements in daily living skills, as seen by a significantly higher rate of growth for Class 1 than Class 2. The average trajectory for each class was plotted for maladaptive behaviors (Fig. 1), autism symptoms (Fig. 2), and daily living skills (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Growth parameters for maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms, and daily living skills by class

| Domain | Class 1 (N = 165) |

Class 2 (N = 199) |

Group comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | t | |

| Maladaptive behaviors | |||||

| Intercept | 110.78 | (6.26) | 117.65 | (8.97) | −8.57*** |

| Linear slope | −0.54 | (0.38) | −0.53 | (0.50) | −0.31 |

| Autism symptoms | |||||

| Intercept | 21.42 | (5.59) | 29.93 | (4.88) | −15.51*** |

| Linear slope | −0.33 | (0.31) | −0.04 | (0.24) | −9.91*** |

| Daily living skills | |||||

| Intercept | 24.44 | (4.36) | 16.06 | (4.65) | 17.61*** |

| Linear slope | 0.20 | (0.28) | −0.03 | (0.23) | 8.44*** |

p< .05;

p< .01;

p< .001

Fig. 1.

Maladaptive behaviors

Fig. 2.

Autism symptoms

Fig. 3.

Daily living skills

Predictors of Class Membership

The likelihood of membership in Class 1, the class with the more desirable profile of change, was predicted based on contextual factors measured at the start of the study, net of control variables (Table 5). Several control variables significantly related to class membership. Given the range of ages represented in the sample, age at the start of the study was included as a control variable. Older individuals were found to be significantly more likely to be in Class 1. Individuals with comorbid ID were 85 % less likely to be Class 1. Follow-up descriptive statistics indicated that 30 % of individuals with ID in the sample were assigned to Class 1 based on their posterior probabilities of trajectory group membership. Gender and maternal education did not relate to class membership. Level of functioning in childhood predicted the likelihood of membership in Class 1. There was a trend toward an increased likelihood for individuals with daily functional use of language at age 4–5 to belong in Class 1. The number of autism symptoms at age 4–5 was significantly predictive of class membership, with higher levels of impairment in childhood associated with a reduced likelihood of membership in Class 1. For each additional impairment present, the likelihood of membership in Class 1 was reduced by 26 %.

Table 5.

Logistic regression predicting membership in class 1

| Predictor | b | (SE) | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables | |||

| Age | 0.08 | (0.02)*** | 1.08 |

| Intellectual disability | −1.92 | (0.35)*** | 0.15 |

| Gender (female) | 0.17 | (0.31) | 1.19 |

| Maternal educationa | −0.54 | (0.34) | 0.58 |

| Verbal language at age 4–5 | 0.57 | (0.31)† | 1.76 |

| Autism symptoms at age 4–5 | −0.30 | (0.11)** | 0.74 |

| Family context | |||

| Maternal positive remarks | 0.25 | (0.07)*** | 1.29 |

| Maternal critical remarks | 0.00 | (0.21) | 1.00 |

| Education context while in school | |||

| Full inclusionb | 1.67 | (0.49)*** | 5.33 |

| Partial inclusionb | 1.24 | (0.33)*** | 3.46 |

| Constant | 3.61 | (2.17)† | 36.93 |

p< .10;

p< .05;

p< .01;

p< .001

1 = high school degree or less, 0 = more than high school degree

Reference category is no inclusion

Next, we examined the extent to which family and educational context factors predicted class membership. With respect to the family context, the number of positive remarks coded from maternal speech samples was predictive of class membership, net of other factors. For each additional positive remark made during the FMSS, the likelihood of membership in Class 1 was increased by 29 %. The number of critical remarks coded from maternal speech samples was not associated with class membership. Concerning the educational context, the level of inclusion experienced while in school predicted the likelihood of membership in Class 1. Net of other factors, individuals who experienced partial inclusion were nearly 4 times more likely to be in Class 1 as individuals who experienced no inclusion. Individuals who experienced full inclusion were over 5 times more likely to be in Class 1 compared to individuals who experienced no inclusion.

Although age at the start of the study was statistically controlled in the logistic regression analysis, we conducted follow up analyses to confirm the pattern of results in two subsamples of varying ages. First, we excluded the oldest quartile of the sample (age 26.06 or older at Time 1). The results of the logistic regression model were replicated in this subsample. Second, we excluded the youngest quartile of the sample (age 14.88 or younger at Time 1). Again, these results were replicated in the subsample.

Discussion

Using data from a prospective, longitudinal study, the present research provided a comprehensive and integrative understanding of changes in the autism phenotype into adulthood and the contextual factors that predict that change. Given the age range of the sample, this study captured changes during the critical transition from adolescence to adulthood (Seltzer et al. 2011). This study integrated variable- and person-centered approaches to identify groups of individuals with ASD with similar profiles of change across a variety of domains of functioning. Importantly, above and beyond individual characteristics and early childhood functioning, aspects of both family and school contexts were found to predict developmental pathways for the adolescents and adults in this sample. The findings highlight contextual factors that may be targeted for intervention to promote adaptation in individuals with ASD into adulthood. This study also demonstrated the value of integrating a variety of methodological approaches to studying change.

On average, autism symptoms, maladaptive behaviors, and daily living skills were observed to improve for the adolescents and adults in this sample over the course of the study. These findings replicated and extended results from our previous work with this sample and support the existing literature base on each of these individual areas of functioning. Age-related improvements in this population have been documented for maladaptive behaviors (Einfeld et al. 2006; Howlin 2005; Matson and Horovitz 2010; Murphy et al. 2005; Shea and Mesibov 2005; Totsika et al. 2010), autism symptoms (Chowdhury et al. 2010; Esbensen et al. 2009; McGovern and Sigman 2005; Seltzer et al. 2004), and daily living skills (Beadle-Brown et al. 2000, 2006; Chadwick et al. 2005a, b).

Research examining individual areas of functioning has led to important knowledge about changes in the autism phenotype over time as well as the contribution of individual and contextual risk and protective factors. Considering these outcomes in isolation of each other, however, limits our understanding of patterns of functioning for individuals throughout the life course. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that jointly considered age-related changes across multiple domains of functioning in this population. Using person-centered analytic methods, we identified two classes of individuals with distinct profiles of change over time. One class of individuals revealed a desirable pattern of consistent improvement in maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms and daily living skills over time, while the other class showed considerably less improvement in autism symptoms and daily living skills but similar levels of improvement in maladaptive behaviors over the study period. Of note, no class was identified with a pattern of global deterioration over time. The significant degree of change, especially by individuals in Class 1, speaks to the behavioral plasticity of individuals with ASD during adolescence and adulthood.

Above and beyond characteristics of the individual with ASD, aspects of the family and school environment influenced the likelihood of following the developmental course characterized by improvement. Mothers who made more positive remarks about their son or daughter with ASD during a short speech sample provided early in the study were significantly more likely to have adult children who subsequently followed a desirable trajectory of global improvement across adolescence and adulthood. By contrast, the number of critical remarks made during this speech sample did not separately relate to later trajectories of functioning. This finding speaks to the power of positive family processes in promoting behavioral plasticity and shaping outcomes for individuals with ASD. Even into adolescence and adulthood, maternal praise and positivity may continue to impact the functioning of individuals with ASD. Interventions that promote maternal positivity may confer indirect benefits to individuals with ASD, although further research is needed.

The level of inclusion experienced in academic and social activities is a defining characteristic of the school experience for youth with ASD. Our findings extended the understanding of the effects of inclusive education, as the experience of partial and full inclusion during the school years had strong associations with the likelihood of an individual demonstrating positive developmental trajectories of autism symptoms, maladaptive behaviors and daily living skills into adulthood. This association was found even after accounting for earlier levels of functioning, specifically the number of autism symptoms present in childhood as well as ID status. These findings underscored the importance of inclusive educational practices. Within inclusive classrooms, students with ASD can be meaningfully integrated into the general academic and social activities (Hunt and McDonnell 2007). Successful inclusion of students with ASD is aided by strategies such as collaborative teaching, where general and special education teachers work together to support the academic progress and social participation of all students (Hunt et al. 2003). Curricula developed with principles of universal design for learning (UDL) in mind also serve to promote the inclusion of students with ASD. Providing students with multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement renders general education curricula more accessible to a wider variety of learners, including students with IDD (Meyer et al. 2013). Although federal law mandates a free, appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act 1997), only 39 % of students with autism spent most (80 % or more) of their school day in general education settings in 2011 (U.S. Department of Education 2015). In the present sample, 47 % received at least part-time inclusion while only 15 % received full-time inclusion. Our findings suggested that early investment and commitment to inclusive education may yield long-term benefits to critical domains of adult functioning for individuals with ASD, although more longitudinal research in this area is necessary.

Although we propose that maternal positive remarks and inclusive educational settings led to improved functioning over the long term for individuals with ASD, these results should be interpreted with caution since the reverse direction of effects could also be true. It is possible that higher levels of functioning early on set the stage for a more positive family climate and a more inclusive educational experience, however we attempted to control for early levels of functioning through verbal language ability and level of autism symptoms at age 4–5. As an additional limitation, we did not examine change in contextual factors over time. Future research will need to confirm and extend our findings.

Certain characteristics of the individuals with ASD predicted the likelihood of following a positive developmental trajectory, in line with previous research with this population. The likelihood of following trajectories of improvement in autism symptoms, maladaptive behaviors and daily living skills was reduced by 85 % for individuals with comorbid ID, net of other individual and contextual factors. Gender, however, was not predictive of long-term outcomes in this study. Limitations in the development of language is generally associated with worse functioning (Howlin et al. 2004; Liss et al. 2001; Park et al. 2012; Shea and Mesibov 2005), however the importance of verbal language abilities at age 4–5 was diminished by other individual and contextual factors in the present study. Beyond simple verbal ability, individuals with more autism-related impairments in childhood were less likely to follow a trajectory of improvement later in adulthood.

This study is not without its limitations. First, the majority of participants identified as White (94 %). This percentage was slightly higher than US census estimates for Massachusetts (86 %) and Wisconsin (90 %) in 2000 when the study began (Grieco 2001). The generalizability of the results to other racial and ethnic groups is therefore limited. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to high quality health care may be exacerbated by a diagnosis of autism (Magaña et al. 2012), which could impact the developmental course of autism symptoms, maladaptive behaviors and daily living skills. The ability to identify a group of individuals with a pattern of global deterioration over time may have been limited by the small sample size of those who deteriorated, or age of the sample. It may be the case that declines are not observed until later in adulthood. Significant declines in neurocognitive function implicated in ASD, such as social cognition, executive functioning, local–global processing, and memory, may not be evident until individuals age into their 60s and beyond (Happé and Charlton 2011). An additional limitation is the reliance on mother report for measures related to childhood and adult functioning. The information about level of inclusion while in school, provided by the mothers, did not capture variability in the level of inclusion across schooling or the quality of the inclusion experience for these individuals. Future research should incorporate teacher-report or observational measures. Lastly, although we selected outcome measures that are sensitive to changes across a wide age range of children, adolescents, and adults, we did not confirm the validity of instruments in the analytic sample.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the limited literature on adult outcomes in ASD. Adults with ASD have ongoing needs for services and supports, yet little research on the autism phenotype in adulthood exists to inform the nature of these interventions (Shattuck et al. 2012). The present study highlighted two critical spheres of influence on development within a community-based sample of adolescents and adults with ASD. The positivity of the family emotional climate and the level of inclusion in the classroom setting represent potential points of intervention in childhood and adolescence that may have lasting impacts on functioning into adulthood. The core domains of autism symptoms, maladaptive behaviors and daily living skills have widespread implications for opportunities for education, work, and independent living (Lowe et al. 2007).

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was prepared with support from the National Institute on Aging (Grant R01 AG08768, M. R. Mailick, principal investigator) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P30 HD03352, A. Messing, principal investigator). We also thank the families who participated in this research.

Footnotes

Author contribution Dr. Woodman conceptualized the analytic method, conducted the statistical analyses, wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and revised the manuscript to address reviewer concerns. Dr. Smith provided guidance on the design of the study and the statistical analyses and participated in manuscript development and revisions. Drs. Greenberg and Mailick formulated the research questions, provided guidance on the design of the study and the statistical analyses and participated in manuscript development and revisions.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Ashley C. Woodman, Email: awoodman@psych.umass.edu.

Leann E. Smith, Email: lsmith@waisman.wisc.edu.

Jan S. Greenberg, Email: greenberg@waisman.wisc.edu.

Marsha R. Mailick, Email: mailick@waisman.wisc.edu.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DK, Liang JW, Lord C. Predicting young adult outcome among more and less cognitively able individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55(5):485–494. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JK, Smith LE, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Taylor JL. Change in maternal criticism and behavior problems in adolescents and adults with autism across a 7-year period. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(2):465–475. doi: 10.1037/a0021900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadle-Brown J, Murphy G, Wing L. The Camberwell cohort 25 years on: Characteristics and changes in skills over time. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2006;19:317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Beadle-Brown J, Murphy G, Wing L, Gould J, Shah A, Holmes N. Changes in skills for people with intellectual disability: A follow-up of the Camberwell cohort. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2000;44(1):12–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2000.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billstedt E, Gillberg IC, Gillberg C. Autism in adults: Symptom patterns and early childhood predictors. Use of the DISCO in a community sample followed from childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(11):1102–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Minshew NJ, Eack SM. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(3):687–694. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1615-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brereton AV, Tonge BJ, Einfeld SL. Psychopathology in children and adolescents with autism compared to young people with intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36(7):863–870. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0125-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist. 1979;34(10):844. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. London: Jessica Kingsley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bruininks RH, Woodcock RW, Weatherman RF, Hill BK. Scales of independent behaviour-revised. Itasca, IL: Riverside; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63(2):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick O, Cuddy M, Kusel Y, Taylor E. Handicaps and the development of skills between childhood and early adolescence in young people with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005a;49(12):877–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick O, Kusel Y, Cuddy M, Taylor E. Psychiatric diagnoses and behaviour problems from childhood to early adolescence in young people with severe intellectual disabilities. Psychological Medicine. 2005b;35(5):751–760. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T. The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders. Recent evidence and future challenges. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;11(6):249–256. doi: 10.1007/s00787-002-0297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury M, Benson BA, Hillier A. Changes in restricted repetitive behaviors with age: A study of high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2010;4(2):210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Coppus AMW. People with intellectual disability: What do we know about adulthood and life expectancy? Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2013;18(6):6–16. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies E, Higginson IJ. The solid facts: Palliative care. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nuovo SF, Buono S. Psychiatric syndromes comorbid with mental retardation: Differences in cognitive and adaptive skills. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41(9):795–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einfeld SL, Piccinin AM, Mackinnon A, Hofer SM, Taffe J, Gray KM, et al. Psychopathology in young people with intellectual disability. Journal of American Medical Association. 2006;296(16):1981–1989. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen AJ, Seltzer MM, Lam KSL, Bodfish JW. Age-related differences in restricted repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39(1):57–66. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0599-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecteau S, Mottron L, Berthiaume C, Burack JA. Developmental changes of autistic symptoms. Autism. 2003;7(3):255–268. doi: 10.1177/1362361303007003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Epidemiological studies of pervasive developmental disorders. In: Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders: Diagnosis, development, neurobiology, and behavior. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. pp. 42–69. [Google Scholar]

- Glutting J, Adams W, Sheslow D. Wide range intelligence test. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gray K, Keating C, Taffe J, Brereton A, Einfeld S, Tonge B. Trajectory of behavior and emotional problems in autism. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;117(2):121–133. doi: 10.1352/1944-7588-117-2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Hong J, Orsmond GI. Bidirectional effects of expressed emotion and behavior problems and symptoms in adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2006;111(4):229–249. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[229:BEOEEA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco EM. The white population: 2000. 2001 http://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/briefs/

- Happé F, Charlton RA. Aging in autism spectrum disorders: A mini-review. Gerontology. 2011;58(1):70–78. doi: 10.1159/000329720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Daley D, Burns C, Beck A. Maternal distress and expressed emotion: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with behavior problems of children with intellectual disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2006;111(1):48–61. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[48:MDAEEC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henninger NA, Taylor JL. Outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: A historical perspective. Autism. 2012;17(1):103–116. doi: 10.1177/1362361312441266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A, Bölte S, Petrova G, Beltcheva D, Tacheva S, Poustka F. Stability and interpersonal agreement of the interview-based diagnosis of autism. Psychopathology. 2001;34(4):187–191. doi: 10.1159/000049305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P. Outcomes in autism spectrum disorders. In: Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders, diagnosis, development, neurobiology, and behavior. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. pp. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Moss P, Savage S, Rutter M. Social outcomes in mid to later adulthood among individuals diagnosed with autism and average nonverbal IQ as children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(6):572–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P, McDonnell J. Inclusive education. In: Odom SL, Horner RH, Snell ME, Blacher J, editors. Handbook on developmental disabilities. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P, Soto G, Maier J, Doering K. Collaborative teaming to support students at risk and students with severe disabilities in general education classrooms. Exceptional Children. 2003;69(3):315–332. [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with Disability Education Act Amendments of 1997 [IDEA] 1997 Retrieved from http://thomas.loc.gov/home/thomas.php.

- Laursen BP, Hoff E. Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52(3):377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Levy A, Perry A. Outcomes in adolescents and adults with autism: A review of the literature. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(4):1271–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Liss M, Harel B, Fein D, Allen D, Dunn M, Feinstein C, et al. Predictors and correlates of adaptive functioning in children with developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001;31(2):219–230. doi: 10.1023/a:1010707417274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism diagnostic interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe K, Allen D, Jones E, Brophy S, Moore K, James W. Challenging behaviours: Prevalence and topographies. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2007;51(8):625–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckasson R, Borthwick-Duffy SEH, Coulter DL, Craig EM, Reeve A, et al. Mental retardation: Definition, classification, and systems of supports. 10th ed. xiii. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maenner MJ, Smith LE, Hong J, Makuch R, Greenberg JS, Mailick MR. Evaluation of an activities of daily living scale for adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities. Disability and Health Journal. 2013;6(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña AB, Goldstein MJ, Karno M, Miklowitz DJ, Jenkins J, Falloon IR. A brief method for assessing expressed emotion in relatives of psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Research. 1986;17(3):203–212. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña S, Parish SL, Rose RA, Timberlake M, Swaine JG. Racial and ethnic disparities in quality of health care among children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;50(4):287–299. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiati I, Tay XW, Howlin P. Cognitive, language, social and behavioural outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review of longitudinal follow-up studies in adulthood. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson D. The logic and implications of a person-oriented approach. In: Cairns RB, Bergman LR, Kagan J, editors. Methods and models for studying the individual. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Dempsey T, Fodstad JC. The effect of autism spectrum disorders on adaptive independent living skills in adults with severe intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30(6):1203–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Horovitz M. Stability of autism spectrum disorders symptoms over time. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2010;22(4):331–342. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Lau AS, Valeri SM, Weisz JR. Parent-child interactions in relation to critical and emotionally overinvolved expressed emotion (EE): Is EE a proxy for behavior? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(1):83–93. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000007582.61879.6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern CW, Sigman M. Continuity and change from early childhood to adolescence in autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(4):401–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Rose DH, Gordon D. Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GH, Beadle-Brown J, Wing L, Gould J, Shah A, Holmes N. Chronicity of challenging behaviours in people with severe intellectual disabilities and/or autism: A total population sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35(4):405–418. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-5030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Second-generation structural equation modeling with a combination of categorical and continuous latent variables: New opportunities for latent class–latent growth modeling. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 91–322. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus user’s guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Park CJ, Yelland GW, Taffe JR, Gray KM. Brief report: The relationship between language skills, adaptive behavior, and emotional and behavior problems in pre-schoolers with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(12):2761–2766. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1534-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskiewicz TL. A comparison of adaptive behavior skills and IQ in three populations: Children with learning disabilities, mental retardation, and autism (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) Philadelphia, PA: Temple University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor DA, Barron KE, Miller BJ, Davis SL. A latent profile analysis of college students’ achievement goal orientation. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2007;32(1):8–47. [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Flanagan HE, Geier JD, Freeman NL. Brief report: The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales in young children with autism spectrum disorders at different cognitive levels. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39(7):1066–1078. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0783-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles A, Anderson DK, Lord C. Heterogeneity and plasticity in the development of language: A 17-year follow-up of children referred early for possible autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55(12):1354–1362. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Congdon R. HLM (version 6) Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt VP, Wtherby AM, Schatschneider C, Lord C. Examination of sex differences in a large sample of young children with autism spectrum disorder and typical development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45:697–706. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2223-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development. 2010;81(1):6–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiege SJ, Meek P, Bryan AD, Petersen H. Latent variable mixture modeling: A flexible statistical approach for identifying and classifying heterogeneity. Nursing Research. 2012;61(3):204–212. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182539f4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Taylor JL, Smith L, Orsmond GI, Esbensen A, Hong J. Adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. In: Amaral DG, Dawson G, Geschwind D, editors. Autism spectrum disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Shattuck PT, Orsmond G, Swe A, Lord C. The symptoms of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33(6):565–581. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000005995.02453.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Shattuck P, Abbeduto L, Greenberg JS. Trajectory of development in adolescents and adults with autism. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2004;10(4):234–247. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Roux AM, Hudson LE, Taylor JL, Maenner MJ, Trani JF. Services for adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;57(5):284–291. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Orsmond GI, Bolt D, Kring S, et al. Change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors in adolescents and adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(9):1735–1747. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0307-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea V, Mesibov GB. Adolescents and adults with autism. In: Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. pp. 288–311. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LE, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Hong J. Symptoms and behavior problems of adolescents and adults with autism: Effects of mother-child relationship quality, warmth, and praise. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113(5):378–393. doi: 10.1352/2008.113:387-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LE, Maenner MJ, Seltzer MM. Developmental trajectories in adolescents and adults with autism: The case of daily living skills. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(6):622–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Carter AS, Cicchetti DV. Vineland screener: Overview, reliability, validity, administration, and scoring. New Haven, CT: Yale University Child Study Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Totsika V, Felce D, Kerr M, Hastings RP. Behavior problems, psychiatric symptoms, and quality of life for older adults with intellectual disability with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40(10):1171–1178. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0975-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totsika V, Hastings RP, Emerson E, Lancaster GA, Berridge DM. A population-based investigation of behavioural and emotional problems and maternal mental health: Associations with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(1):91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Digest of education statistics, 2013 (NCES 2015-011) 2015 Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_204.60.asp.

- Wearden AJ, Tarrier N, Barrowclough C, Zastowny TR, Rahill AA. A review of expressed emotion research in health care. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):633–666. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF. Best practices in quantitative methods for developmentalists: III. Missing data: What to do with or without them. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71(3):42–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2006.07103001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman AC, Mailick MR, Greenberg JS. Trajectories of psychopathology in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Development & Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/S095457941500108X. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman AC, Smith LE, Greenberg JS, Mailick MR. Change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors in adolescence and adulthood: The role of positive family processes. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(1):111–126. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2199-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10 1986 draft of chapter 5 categories F00–F99. Mental, behavioural and developmental disorders. Geneva: Author; 1987. [Google Scholar]