Abstract

Purpose. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the regional synchronization of brain in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME). Methods. Resting-state fMRI data were acquired from twenty-one patients with JME and twenty-two healthy subjects. Regional homogeneity (ReHo) was used to analyze the spontaneous activity in whole brain. Two-sample t-test was performed to detect the ReHo difference between two groups. Correlations between the ReHo values and features of seizures were calculated further. Key Findings. Compared with healthy controls, patients showed significantly increased ReHo in bilateral thalami and motor-related cortex regions and a substantial reduction of ReHo in cerebellum and occipitoparietal lobe. In addition, greater ReHo value in the left paracentral lobule was linked to the older age of onset in patients. Significance. These findings implicated the abnormality of thalamomotor cortical network in JME which were associated with the genesis and propagation of epileptiform activity. Moreover, our study supported that the local brain spontaneous activity is a potential tool to investigate the epileptic activity and provided important insights into understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of JME.

1. Introduction

Idiopathic generalized epilepsies (IGE) are a group epilepsy syndrome clinically characterized by generalized tonic-clonic, myoclonic, and absence seizures [1]. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) is a common subtype of IGE with an age-related onset of seizures, characterized by myoclonic jerks, tonic-clonic seizures, and less frequently absence seizures [2]. Standard interictal electroencephalography (EEG) features of JME consist of 4–6 Hz generalized spike-wave or polyspike-wave discharges (GSWDs) with a frontocentral predominance [2]. The corticothalamus circuit was considered a contributing factor in the propagation of GSWDs. Recently, simultaneous EEG-fMRI has been broadly used in epilepsy research, which demonstrated the metabolic alteration related to the GSWDs at the thalamus and wide cortex [3, 4]. Also, the myoclonic jerks, as a character of JME, may be caused by the motor circuitry hyperexcitability in EEG and fMRI studies [5, 6]. Thus, the thalamus and motor-related cortex may play an important role in JME. Resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) is extensively used to reflect spontaneous neuronal synchronization and intrinsic neurophysiologic process of the brain [7]. Many valuable findings of rs-fMRI were observed in neuropsychological diseases such as epilepsy [8–10], schizophrenia [11], and Alzheimer's disease [12].

As a data-driven method, regional homogeneity (ReHo) is able to measure the synchronization of activity in different brain regions by calculating the similarity of the time series of a given voxel with those of its nearest neighbors in a voxel-wise way [13]. This method has been applied to various clinical populations to investigate the functional modulations in the resting state [14–17]. Growing evidence have indicated increased synchronization in the epileptogenic zones during seizures and interictal state [18], which is believed to be involved in the generation of interictal activity [19]. In 2013, Zeng et al. observed that the significantly increased ReHo in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy might be related to the seizure genesis [20]. It is also interesting to note that, in generalized epilepsy with absence seizures [21] and generalized tonic clonic seizures [22], the ReHo features implicated the abnormality in striatothalamocortical network and default mode network. We wish to state here that, to best of our knowledge, there is not study focused on the local spontaneous activity according to the ReHo in JME. We, therefore, hypothesized that the ReHo characters would be altered between patients with JME and healthy controls, and the altered spontaneous brain activity may involve motor-related regions to response the myoclonic jerks in JME.

To evaluate the alterations of spontaneous brain activity in patients with JME, we investigated the ReHo features in a group of patients and healthy controls using rs-fMRI. We further assessed the influence of the ReHo alterations on the clinical factors in JME.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Twenty-one (21) patients (mean age: 22.3 ± 5.7 years; mean years of duration: 10.9 ± 5.4; 14 females) with JME were recruited in Center for Information in Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China. All patients were diagnosed as JME based on the clinical and seizure semiology information consistent with the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) guidelines [23] by epileptologists (P. Wang and C. Zhong). All the routine brain neuroimaging including CT and MRI scanning showed no structural abnormalities; and scalp EEG demonstrated 4–6 Hz generalized spike-wave or polyspike-wave discharges. Twenty-two healthy controls were recruited as sex- and age-matched control group (mean age: 23.1 ± 8.7 years; 15 female). All the controls were free of neurological or psychiatric disorders. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Science and Technology of China according to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

2.2. Data Acquisition

All subjects underwent MRI scanning in 3 T GE scanner with an eight-channel-phased array head coil (MR750; GE Discovery, Milwaukee, WI) in the MRI research center of University of Electronic Science and Technology of China. The resting-state functional data were collected using an echo-planar imaging sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, flip angle (FA) = 90, field of view (FOV) = 24 × 24 cm2, matric = 64 × 64, and slice thickness = 4 mm with 0.4 mm gap and 255 volumes in each run. Axial anatomical T1-weighted images were acquired using a 3-dimensional fast spoiled gradient echo (T1-3D FSPGR) sequence (TR = 6.008 ms, TE = 1.984 ms, FA = 90, matrix = 256 × 256, FOV = 25.6 × 25.6 cm2, and slice thickness = 1 mm (no gap)) to generate 152 slices. During the examination, all subjects were instructed to be “relaxed, eyes closed” and kept awake and not to think of anything in particular.

2.3. Data Preprocessing

Preprocessing of fMRI dataset was conducted using the SPM8 software package (statistical parametric mapping available at http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The first five volumes of each run was discarded to ensure magnetic field stabilization. The remaining 250 volumes were slice-time corrected and realigned. Any subject whose head motion exceeded 1.5 mm or/and 1.5 degrees was excluded in the following steps. We also assessed translation and rotation in both groups using the following formula [24, 25]: head motion/rotation = , where M is the length of the time courses (M = 250 in this study); x i, y i, and z i are translations/rotations at the ith time point in the x, y, and z directions, respectively, and Δd xi = x i − x i−1, and similar formula for y i and z i. The realigned images were spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template using a 12-parameter affine transformation and resliced with voxel size of 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm. Then the images were smoothed with Gaussian kernel (8 mm full width at half maximum, FWHM). No temporal filtering was performed in this processing in consideration of the following analyses in full frequency band.

2.4. ReHo Analysis

The value of ReHo, which reflected the Kendall's coefficient of concordance of the Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) singles in local regions, was calculated using REST software (http://www.restfmri.net/forum/REST). We measured the homogeneity of time series of a center voxel in the cluster consisted of 27 nearest neighboring voxels. Then the resulted ReHo map was normalized by the mean ReHo value within the brain mask. Lastly, the map was smoothed with an isotropic Gaussian kernel (6 mm full width at half maximum).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

First, one-sample t-test was used in the ReHo value to evaluate the local spontaneous brain activity in both groups. Then, two-sample t-test was utilized to obtain the difference between JME and control group. The significance was set at P < 0.05 with FDR correction for multicompares and the cluster correction with a minimum cluster size of 23 voxels. Furthermore, the partial correlation analysis was performed to detect the relation between the value of ReHo of brain regions with significant difference and the clinical features including onset age and duration of epilepsy, with controlling effects of gender and age.

3. Results

Two of the recruited 21 patients were excluded from the ReHo analysis because of excessive head motion. There were no significant differences between the two groups in head motion and rotation (two-sample two-tailed t-test; T = 1.50, P = 0.14 for translational motion; and T = 1.15, P = 0.25 for rotational motion). The detailed demographic data of patients is shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of 19 juvenile myoclonic epilepsy patients.

| Number | Gender | Age (year) | Age at seizure onset (year) | Frequency of GSWDs (Hz) | History/family history | Antiepileptic drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 17 | 13 | 2 | Sister with JME | VPA |

| 2 | F | 17 | 3 | 3~3.5 | Sister with JME | VPA |

| 3 | M | 26 | 8 | 6 | — | MVP |

| 4 | F | 20 | 6 | 2 | — | VPM, LTG |

| 5 | F | 27 | 16 | 4 | Daughter with GTCS | VPA |

| 6 | F | 16 | 13 | 3 | — | LTG |

| 7 | F | 22 | 14 | 3 | — | VPA |

| 8 | F | 23 | 7 | 5 | — | VPA |

| 9 | M | 15 | 5 | 3~3.5 | — | — |

| 10 | F | 17 | 10 | 4~4.5 | — | VPA |

| 11 | F | 29 | 10 | 3~3.5 | — | VPM |

| 12 | F | 33 | 20 | 6.5~7 | — | VPM, LTG |

| 13 | M | 18 | 14 | 5 | — | VPM |

| 14 | M | 22 | 8 | 4 | — | VPM |

| 15 | F | 21 | 11 | 2 | — | VPM |

| 16 | F | 19 | 12 | 2 | — | MVP |

| 17 | M | 34 | 14 | 3 | — | VPM, TCD |

| 18 | F | 25 | 21 | 3~3.5 | Uncle with GTCS | VPM |

| 19 | M | 30 | 9 | 3.5~4 | — | TOP, CBZ |

M: male; F: female; VPA: valproic acid; VPM: valpromide; MVP: magnesium valproate; LTG: lamotrigine; TOP: topiramate; CBZ: carbamazepine.

3.1. Within-Group and Between-Group ReHo Values

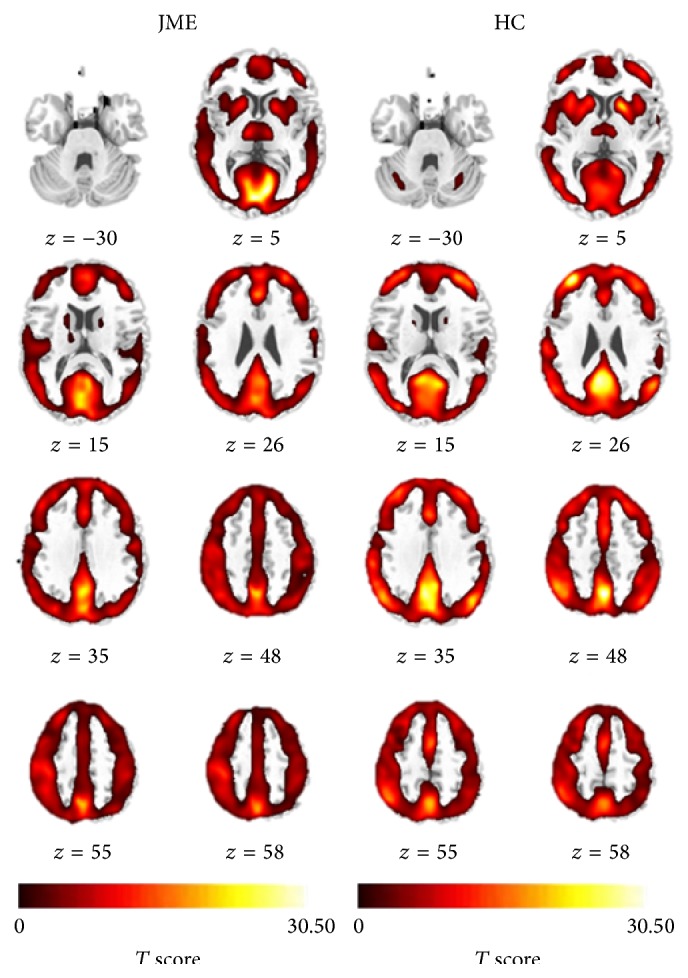

The results of one-sample t-test in both groups was shown in Figure 1, respectively. The voxels with high ReHo value was found in bilateral distributed brain regions, including the major regions of the DMN, such as the medial frontal lobe, posterior cingulate cortex, and other regions including the thalami, putamen, caudate, insula, visual cortex, and cerebellum.

Figure 1.

The ReHo results for patients with JME and healthy controls. The T values of one-sample t-test were showed in each group, respectively. HC: healthy control group.

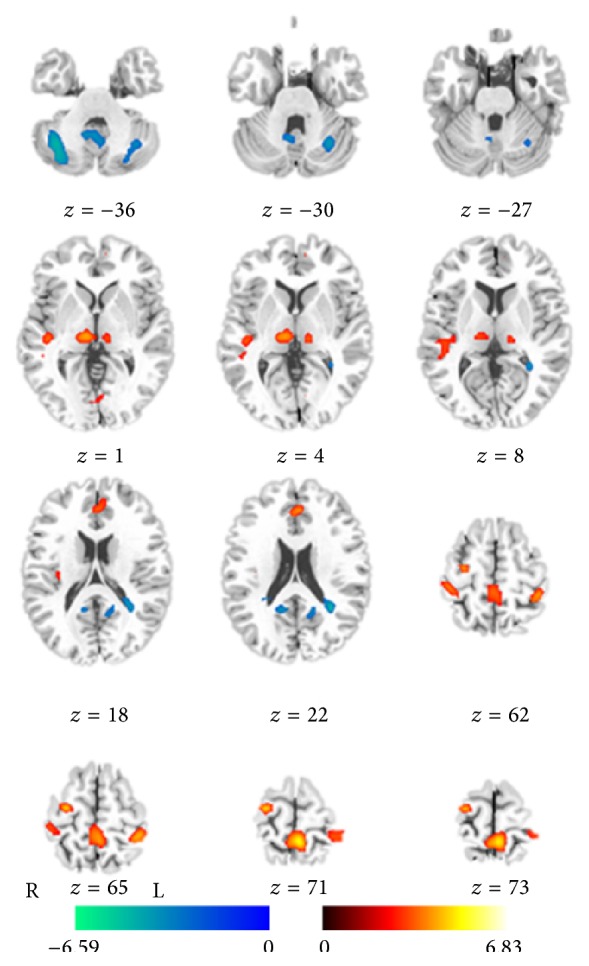

The significant differences of ReHo between two groups (P < 0.05, FDR corrected) were demonstrated in the Figure 2; and detailed information of clusters with difference was recorded in Table 2. Compared with the healthy controls, JME patients showed significantly increased ReHo values at left paracentral lobule, right precentral gyrus, bilateral postcentral gyrus, left anterior cingulate gyrus, right posterior insular/superior temporal gyrus, and bilateral thalami. Significantly decreased ReHo values were also shown in bilateral cerebellum, right cuneus, right precuneus, left middle frontal gyrus, and left superior marginal gyrus.

Figure 2.

Statistic t-map showing the difference between the JME group and healthy control (two-sample t-test, P < 0.05 with FDR correction). The T scores were showed with hot color for positive values (JME > healthy controls) and cool colors for negative values (JME < healthy controls).

Table 2.

Brain regions showing abnormal regional homogeneity in patients with JME.

| Brain region | MNI coordinates (x, y, z) |

BA | T value | Voxel number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients > controls | ||||

| Paracentral lobule L | −3, −45, 69 | 5 | 6.08 | 151 |

| Precentral gyrus R | 27, −15, 66 | 6 | 5.61 | 45 |

| Thalamus R | 9, −21,0 | — | 5.15 | 48 |

| Thalamus L | −8, −23,1 | — | 4.98 | 38 |

| Postcentral gyrus L | −39, −39,63 | 2 | 4.38 | 48 |

| Anterior cingulate gyrus L |

−3, 36, 24 | 32 | 4.69 | 34 |

| Posterior insular/superior temporal lobule R |

45, −33, 9 | 41 | 4.03 | 32 |

| Patients < controls | ||||

| Cerebellum_Crus2 R | 33, −75, −42 | — | 6.57 | 298 |

| Middle occipital L | −36, −66,30 | 19/39 | 4.71 | 228 |

| Cuneus R | 15, −66,36 | 7 | 5.16 | 190 |

| Cerebellum_Crus1 L | −30, −63, −33 | — | 4.82 | 208 |

| Calcarine L | −12, −57,18 | 23/30 | 4.40 | 47 |

| Supramarginal R | 66, −24,27 | 2/48 | 4.03 | 54 |

MNI: Montreal Neurological Institute; BA: Brodmann area; L: left; R: right.

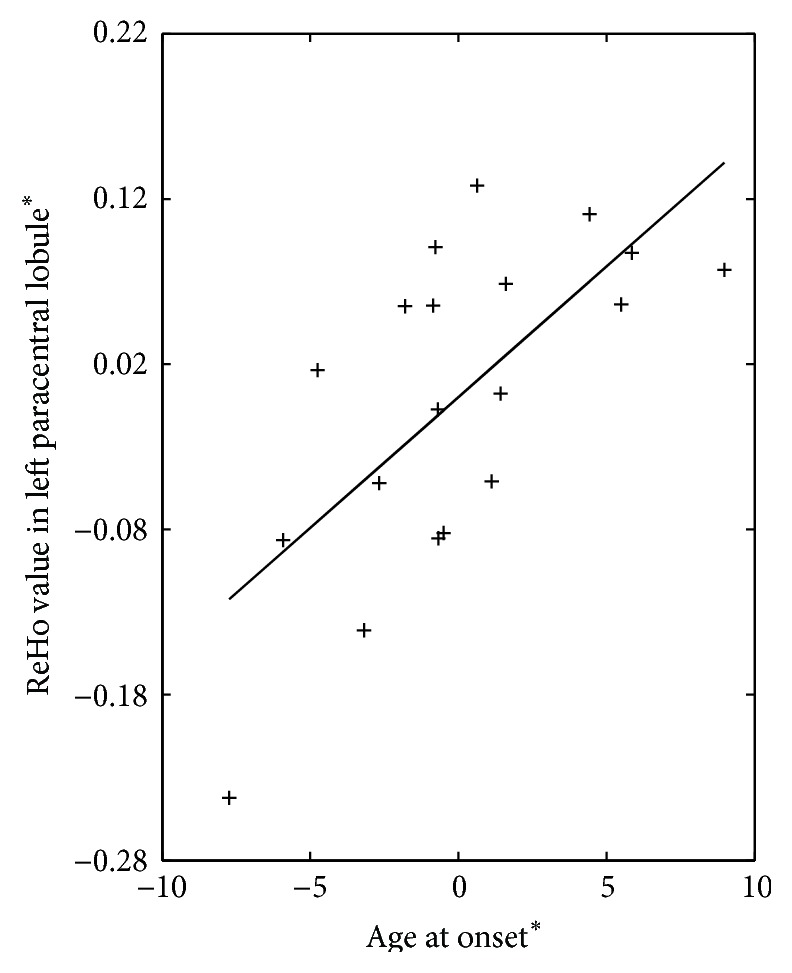

3.2. Correlation Analyses

The relation analysis of mean ReHo in JME patients and clinical features revealed a significant positive correlation between age of onset and ReHo value in left paracentral lobule (r = 0.68, P = 0.002) (Figure 3). No significant correlations were observed between duration of disease and ReHo value in all regions with difference between groups.

Figure 3.

The relation between ReHo value in left paracentral lobule and age at onset in patients with JME. +: the coordinate value implicates the residuals after controlling for the influence of the gender and age (linear regression with covariates including gender and age).

4. Discussion

The current study originally investigated the alterations of regional synchronization in patients suffering from JME compared with a group of age and gender-matched controls using the resting-state fMRI. We performed a voxel-based comparison of ReHo value to identify the alterations in local spontaneous brain activity. Compared to healthy controls, patients with JME showed a significant increased ReHo value in bilateral thalami and some cortex regions related to motor function, including primary motor and sensory cortex, insula, and anterior cingulate cortex; the significant reduction of ReHo was also observed in cerebellum and occipitoparietal lobe. Furthermore, our study showed that the high ReHo value in the left paracentral lobule was linked to the older age of onset in patients. ReHo represents the temporal similarity of the signals in a given local region, which may reflect spontaneous brain activity [13]. The epileptogenic zones might be related to the abnormal synchronization of neural electrical activity [26]. Consistent with the previous researches, which suggested abnormalities in frontal lobe and thalamus in JME [27], our investigation suggests the abnormality of thalamomotor cortical network in JME which were associated with the genesis and propagation of epileptiform activity. We, hence, provided important insights into understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of JME.

The regions related to motor function and bilateral thalami had increased ReHo values in JME patients compared to controls in this study. In fact, more and more structural and functional evidences supported that the thalami and motor regions play important role in JME [27–29]. Thalami in functional level are proposed to be involved in the propagation of generalized epileptic discharges in JME [27]. It is important to state that recent studies of simultaneous EEG and fMRI have consistently shown altered metabolic activity at cortical and subcortical regions, especially the thalami, in generalized epilepsy [3]. A study of MRS showed an absolute reduction of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) value in the thalamus in JME [30], which may reflect the abnormality of metabolite at the thalami. This observation may result from a reflection of neuronal marker by NAA in the injured neuron [31]. In addition to the functional abnormalities in JME patients, structural changes were revealed in many studies. The structural researches centered on voxel-based morphometry demonstrated reductions in gray matter volume of the thalami [32] and a negative correlation between thalamic gray matter volume and the duration of epilepsy [33]. Diffused tensor imaging studies of patients with JME particularly in thalamocotical fiber white matter indicated a significant decreased diffusion feature and fractional anisotropy [34]. Recently, MRI studies in JME illustrated structural and functional abnormality in the motor cortex in patients with JME [5, 35]; in particular, the functional changes were observed in the unaffected siblings of patients, suggesting the underlying genetic risk of JME [35]. In addition, ReHo was identified with a neuroimaging marker to investigate the neural activity [36]. The increased ReHo value was responsible for seizure genesis and propagation, such as increased ReHo in the ipsilateral mesial temporal structure in patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy [37] and in the central, premotor, and prefrontal regions in patients with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal region spikes [38]. Together with our findings of increased ReHo in thalami and motor-related cortex, we inferred that these findings may reflect dysfunction of the thalamocortical network associated with epileptic activity in JME.

Furthermore, patients with JME also exhibited a stronger magnitude of the regional spontaneous activity in left paracentral lobule, and was positively correlated with the age of onset. These findings would reflect the influence of seizures on neural plasticity in JME patients. We presumed that patients with earlier age of seizures have more compensatory mechanisms of maturation, as the younger brain is more plastic and can accommodate more easily than an adult mature brain [39]. In addition, recent research observed that ReHo across the entire brain was higher in children than in adolescents and adults in healthy controls [40]. Thus, based on the enhanced influence of myoclonic seizures on the ReHo magnitude at left paracentral lobule, the positive relation might indicate that patients with the later onset age, who illustrated higher ReHo value, have low effect resulting from development.

Meanwhile, the alterations of local regional synchronization of brain activity may provide a possible measurement to assess the potential epileptogenic region. The increased ReHo in ipsilateral parahippocampal gyrus was found in the mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, suggesting an important implication for the seizure genesis and propagation [20]. Functional abnormality at motor cortex is considered to play a critical role for jerks during myoclonic seizures. Thus, the increased ReHo at the primary motor and sensory cortex may imply that the local brain spontaneous activity contributed to localize the epileptogenic zone in JME.

Another remarkable finding in our study is the decreased ReHo in cerebellum and occipitoparietal lobe. In fact, there are more and more studies showing that cerebellum may be important for cognitive beyond classical involvement of motor coordination [41]. In addition, the cerebellum plays a role in multiple functional domains: cognitive, affective, and sensory function [42, 43]. It was also observed that the altered ReHo value was present in patients with absence seizures and generalized tonic clonic seizures. In line with these studies, our finding of decreased ReHo in the cerebellum in JME patients may hint the potential spontaneous neural activity in cerebellum related partially to the neurological JME. Also, decreased ReHo was observed in the occipitoparietal lob, especially at right precuneus lobe. As acknowledged by us, these regions are the salient posterior nodes of default mode network (DMN), which maintains the baseline of spontaneous neuronal activities related to self-awareness, episodic memory, and interactive modulation between internal mental activities and external tasks [44]. The altered spontaneous BOLD fluctuation in DMN has been observed in patients with epilepsy [22, 45, 46]. In this study, we noted that the decreased ReHo in DMN may be associated with the functional impairments in cognitive processes in patients with JME. However, further study and analysis of DMN would be considered in the future.

Notwithstanding the results of this study, there are several limitations inherent in our research. One limitation concerns the sample size which is relatively small. A second limitation is in regard to the possibility of interictal epileptic discharges influencing the resting-state functional connectivity in patients with epilepsy. The EEG, however, was not recorded during fMRI scans, so it is impossible to rule out the effect of confounding epileptic discharges. Therefore, simultaneous EEG-fMRI would be considered in the further study to clarify the relationship between ReHo and the interictal epileptic discharges. Third, the antiepileptic drugs taken by some patients may confound the finding in this study. In general, the antiepileptic drugs may directly act on the neurotransmitters in brain, so the spontaneous activity might be influenced directly by antiepileptic drugs. In addition, the cognitive impairment of antiepileptic drugs have been found in many studies; the abnormal cognition related to the antiepileptic drugs might contribute to the altered spontaneous brain activity in epilepsy.

5. Conclusion

In this research, we studied the patter of regional hemodynamic synchronization in the JME patients by using ReHo analysis in resting-state fMRI. Patients with JME demonstrated altered regional synchronization in bilateral thalami, motor-related cortex, the posterior DMN regions, and cerebellum. In addition, the enhancing magnitude of the regional spontaneous activity with increasing age of onset was observed in the left paracentral lobule in patients. The increased ReHo composed in the thalamomotor cortical network might indicate that the local brain spontaneous activity contributed to localize the epileptogenic zone in JME. These results, which would support ReHo methods as a potential tool to detect intrinsic epileptic activity, provide important insights into understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of JME.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by Grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81330032, 81271547, 81371636, 81471638, and 81160166), the 863 Project (2015AA020505), the Special-Funded Program on National Key Scientific Instruments and Equipment Development of China (2013YQ490859), the PCSIRT Project (IRT0910), and the “111” Project (B12027). The authors thank Dr. Benjamin Klugah-Brown for his English language assistance.

Conflict of Interests

The authors confirm that they have read the journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines. None of the authors have any conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Genton P., Thomas P., Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenite D. G., et al. Clinical aspects of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2013;28(supplement 1):S8–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janz D. Epilepsy with impulsive petit mal (juvenile myoclonic epilepsy) Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1985;72(5):449–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1985.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotman J., Grova C., Bagshaw A., Kobayashi E., Aghakhani Y., Dubeau F. Generalized epileptic discharges show thalamocortical activation and suspension of the default state of the brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(42):15236–15240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504935102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Q., Luo C., Yang T., et al. EEG-fMRI study on the interictal and ictal generalized spike-wave discharges in patients with childhood absence epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2009;87(2-3):160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vollmar C., O'Muircheartaigh J., Barker G. J., et al. Motor system hyperconnectivity in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a cognitive functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain. 2011;134(6):1710–1719. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panzica F., Rubboli G., Franceschetti S., et al. Cortical myoclonus in Janz syndrome. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2001;112(10):1803–1809. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00634-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox M. D., Raichle M. E. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(9):700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo C., Li Q., Xia Y., et al. Resting state basal ganglia network in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Human Brain Mapping. 2012;33(6):1279–1294. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo C., Qiu C., Guo Z., et al. Disrupted functional brain connectivity in partial epilepsy: a resting-state fMRI study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028196.e28196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo C., Yang T., Tu S., et al. Altered intrinsic functional connectivity of the salience network in childhood absence epilepsy. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2014;339(1-2):189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Heuvel M. P., Mandl R. C. W., Stam C. J., Kahn R. S., Hulshoff Pol H. E. Aberrant frontal and temporal complex network structure in schizophrenia: a graph theoretical analysis. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(47):15915–15926. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2874-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greicius M. D., Srivastava G., Reiss A. L., Menon V. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer's disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(13):4637–4642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308627101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zang Y., Jiang T., Lu Y., He Y., Tian L. Regional homogeneity approach to fMRI data analysis. NeuroImage. 2004;22(1):394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z., Xu C., Xu Y., et al. Decreased regional homogeneity in insula and cerebellum: a resting-state fMRI study in patients with major depression and subjects at high risk for major depression. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2010;182(3):211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Q.-Z., Li D.-M., Kuang W.-H., et al. Abnormal regional spontaneous neural activity in treatment-refractory depression revealed by resting-state fMRI. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32(8):1290–1299. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu T., Long X., Zang Y., et al. Regional homogeneity changes in patients with Parkinson's disease. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30(5):1502–1510. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paakki J.-J., Rahko J., Long X., et al. Alterations in regional homogeneity of resting-state brain activity in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Research. 2010;1321:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bettus G., Wendling F., Guye M., et al. Enhanced EEG functional connectivity in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2008;81(1):58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ortega G. J., Menendez De La Prida L., Sola R. G., Pastor J. Synchronization clusters of interictal activity in the lateral temporal cortex of epileptic patients: intraoperative electrocorticographic analysis. Epilepsia. 2008;49(2):269–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng H. W., Pizarro R., Nair V. A., La C., Prabhakaran V. Alterations in regional homogeneity of resting-state brain activity in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2013;54(4):658–666. doi: 10.1111/epi.12066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang T., Fang Z., Ren J., et al. Altered spontaneous activity in treatment-naive childhood absence epilepsy revealed by Regional Homogeneity. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2014;340(1-2):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong Y., Lu G., Zhang Z., Jiao Q., Li K., Liu Y. Altered regional synchronization in epileptic patients with generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Epilepsy Research. 2011;97(1-2):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel J., Jr. A proposed diagnostic scheme for people with epileptic seizures and with epilepsy: report of the ILAE task force on classification and terminology. Epilepsia. 2001;42(6):796–803. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.10401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue K., Luo C., Zhang D., et al. Diffusion tensor tractography reveals disrupted structural connectivity in childhood absence epilepsy. Epilepsy Research. 2014;108(1):125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao W., Luo C., Zhu B., et al. Resting-state functional connectivity in anterior cingulate cortex in normal aging. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2014;6, article 280 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghosh-Dastidar S., Adeli H. Improved spiking neural networks for EEG classification and epilepsy and seizure detection. Integrated Computer-Aided Engineering. 2007;14(3):187–212. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson J., Hamandi K. Understanding juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: contributions from neuroimaging. Epilepsy Research. 2011;94(3):127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caeyenberghs K., Powell H. W. R., Thomas R. H., et al. Hyperconnectivity in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a network analysis. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2015;7:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koepp M. J., Woermann F., Savic I., Wandschneider B. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy—neuroimaging findings. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2013;28(supplement 1):S40–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haki C., Gümüştaş O. G., Bora I., Gümüştaş A. U., Parlak M. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of bilateral thalamus in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Seizure. 2007;16(4):287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuff N., Meyerhoff D. J., Mueller S., et al. N-acetylaspartate as a marker of neuronal injury in neurodegenerative disease. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2006;576:241–263. doi: 10.1007/0-387-30172-0_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mory S. B., Betting L. E., Fernandes P. T., et al. Structural abnormalities of the thalamus in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2011;21(4):407–411. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J. H., Lee J. K., Koh S.-B., et al. Regional grey matter abnormalities in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a voxel-based morphometry study. NeuroImage. 2007;37(4):1132–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deppe M., Kellinghaus C., Duning T., et al. Nerve fiber impairment of anterior thalamocortical circuitry in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Neurology. 2008;71(24):1981–1985. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336969.98241.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wandschneider B., Centeno M., Vollmar C., et al. Motor co-activation in siblings of patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: an imaging endophenotype? Brain. 2014;137(9):2469–2479. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuo X.-N., Xu T., Jiang L., et al. Toward reliable characterization of functional homogeneity in the human brain: preprocessing, scan duration, imaging resolution and computational space. NeuroImage. 2013;65:374–386. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng H., Pizarro R., Nair V. A., La C., Prabhakaran V. Alterations in regional homogeneity of resting-state brain activity in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2013;54(4):658–666. doi: 10.1111/epi.12066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang Y., Ji G., Yu Y., et al. Altered regional homogeneity in rolandic epilepsy: a resting-state FMRI Study. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:8. doi: 10.1155/2014/960395.960395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Helmstaedter C., Sonntag-Dillender M., Hoppe C., Elger C. E. Depressed mood and memory impairment in temporal lobe epilepsy as a function of focus lateralization and localization. Epilepsy and Behavior. 2004;5(5):696–701. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dajani D. R., Uddin L. Q. Local brain connectivity across development in autism spectrum disorder: a cross-sectional investigation. Autism Research. 2015 doi: 10.1002/aur.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diamond A. Close interrelation of motor development and cognitive development and of the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex. Child Development. 2000;71(1):44–56. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Townsend J., Courchesne E., Covington J., et al. Spatial attention deficits in patients with acquired or developmental cerebellar abnormality. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19(13):5632–5643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05632.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmahmann J. D., Sherman J. C. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain. 1998;121(4):561–579. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox M. D., Snyder A. Z., Vincent J. L., Corbetta M., Van Essen D. C., Raichle M. E. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(27):9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z., Lu G., Zhong Y., et al. Altered spontaneous neuronal activity of the default-mode network in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Research. 2010;1323:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Q., Cao W., Liao X., et al. Altered resting state functional network connectivity in children absence epilepsy. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2015;354:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]