Abstract

The high prevalence of cigarette smoking and tobacco related morbidity and mortality in people with chronic mental illness is well documented. This review summarizes results from studies of smoking cessation treatments in people with schizophrenia, depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder. It also summarizes experimental studies aimed at identifying biopsychosocial mechanisms that underlie the high smoking rates seen in people with these disorders. Research indicates that smokers with chronic mental illness can quit with standard cessation approaches with minimal effects on psychiatric symptoms. Although some studies have noted high relapse rates, longer maintenance on pharmacotherapy reduces rates of relapse without untoward effects on psychiatric symptoms. Similar biopsychosocial mechanisms are thought to be involved in the initiation and persistence of smoking in patients with different disorders. An appreciation of these common factors may aid the development of novel tobacco treatments for people with chronic mental illness. Novel nicotine and tobacco products such as electronic cigarettes and very low nicotine content cigarettes may also be used to improve smoking cessation rates in people with chronic mental illness.

Introduction

Rates of cigarette smoking among adults in the United States and United Kingdom are two to four times higher in people with current mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders than in those without mental illness.1 2 For example, a recent study in more than 9000 people with severe psychotic disorders found that these people had a higher risk of having ever smoked 100 cigarettes (odds ratios 4.61, 95% confidence interval 4.3 to 4.9) relative to the general population after controlling for sex, race, age, and geographical region.3

Smokers with chronic mental illness are also more dependent on nicotine and are less likely to quit than those without these disorders.4 5 6 Notably, between 2004 and 2011, after controlling for risk factors such as income, education, and employment, current smoking rates dropped from 19.2% (18.7% to 19.7%) to 16.5% (16.0% to 17.0%) in US residents without mental illness but not in those with mental illness.6 Consequently, about 50% of deaths in patients with chronic mental illness are due to tobacco related cancers, respiratory diseases, and cardiovascular conditions.7 8

This review critically assesses the effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments for people with schizophrenia, unipolar and bipolar depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Because the development of novel treatments for smoking cessation in people with chronic mental illness may be facilitated by the identification of factors that contribute to their smoking, we also critically examine biopsychosocial mechanisms thought to underlie these people’s high smoking rates. Finally, given the current commercial and regulatory interest in electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) and very low nicotine content cigarettes, we describe recent studies of these products in people with chronic mental illness and discuss how such products might be used to improve smoking cessation outcomes for these people.

Sources and selection criteria

This review examines the effects and mechanisms of smoking cessation treatment in adults (≥18 years) with schizophrenia, unipolar or bipolar depression, anxiety disorders, or PTSD. References were identified through searches of publications listed in PubMed and ScienceDirect from inception to 1 December 2014. We used the following keywords: “schizophrenia”, “depression”, “unipolar”, “bipolar”, “anxiety”, “panic” “PTSD”, “smoking”, “smoking cessation”, “clinical trial”, “nicotine replacement”, “bupropion”, “varenicline”, “withdrawal”, “abstinence”, “cigarette”, “electronic cigarette” “very low nicotine cigarette”, and “denicotinized cigarette”. References were also identified from relevant reviews, meta-analyses, and the authors’ files. JWT and MEM independently reviewed the titles retrieved from the search and prepared an initial list of articles to be included in the review. Both authors then reviewed the abstracts and selected the most pertinent studies to include in the review. Because this is not a systematic review, we did not grade the included studies, but rather summarized outcomes. Only peer reviewed articles published in English were reviewed. We examined current guidelines for treating smoking in people with mental illness by searching the websites of international health organizations and by searching Google using the keywords “smoking cessation guidelines”, “tobacco treatment guidelines”, “mental illness”, and “mental disorders”.

Schizophrenia

Interest in the association between schizophrenia and smoking was galvanized by a report published almost 30 years ago indicating that people with chronic mental illness had substantially higher smoking rates than control samples across age, sex, marital, socioeconomic, and alcohol use subgroups. The report also found that the smoking rate was particularly high (88%) in patients with schizophrenia.9

A second finding that triggered intense interest in the schizophrenia-smoking comorbidity was the observation that urinary concentrations of the major nicotine metabolite, cotinine, were 1.6 times higher in smokers with schizophrenia than in control smokers without schizophrenia.10 These findings prompted two parallel lines of research, one aimed at finding potential treatments for tobacco dependence in smokers with schizophrenia and the other aimed at identifying biopsychosocial mechanisms that might account for this comorbidity.

Smoking cessation studies

Nicotine replacement therapy plus psychosocial treatment

Several observational studies of open label nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) plus psychosocial treatment with motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) components have been conducted in smokers with schizophrenia (table 1).

Table 1.

Outcomes of cessation treatment trials of NRT in outpatients with schizophrenia*

| Study | N | Intervention | Abstinence rates | Other outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ziedonis and George 199711 | 24 | 10 week treatment with open label NRT (21 mg patch and gum) plus weekly behavioral, psychoeducational, and motivational enhancement therapy (no control group) | 50% completed the program and 13% were abstinent for 6 months | 40% of patients decreased CPD by half; there were no changes in psychiatric symptoms |

| Addington et al 199812 | 65 | 10 week treatment with open label NRT (21 mg patch), plus 7 weekly group sessions based on the ALA “Freedom from Smoking” program, tailored for people with schizophrenia (no control group) | 77% completed treatment; 42% of completers (32% of enrolled) were abstinent at end of treatment, 16% (12% of enrolled) at 3 month follow-up, and 12% (9% of enrolled) at 6 month follow-up | Group session attendance was associated with abstinence at follow-ups; there were no changes in psychiatric or extrapyramidal symptoms |

| George et al 200013 | 45 | 10 week treatment with open label NRT (21 mg patch) plus randomization to the ALA “Freedom from Smoking” program or a tailored program with motivational, behavioural, and psychoeducational components | 32.1% attained 4 week continuous abstinence at end of treatment in the tailored program v 23.5% in the ALA program (P<0.06); 17.6% abstinent at 6 months in the ALA program v 10.7% in the tailored program (P<0.03) | Use of atypical antipsychotics was associated with longer treatment retention and higher abstinence rates; there were no effects of treatment or abstinence on psychiatric symptoms dyskinesia or extrapyramidal symptoms |

| Chou et al 200414 | 68 | 8 week treatment with open label NRT (14 mg patch) or assessment only control | 26.9% point prevalence abstinence and 23.1% continuous abstinence in the NRT group at 3 months v 0% in the control group (significance level not reported) | Daily smoking rates were reduced by over half at 3 months in the experimental group; no change in the control group |

| Baker et al 200615 | 298 | Randomization to 10 week treatment including open label NRT (21 mg patch), 8 sessions of individual motivational interviewing, and CBT, or to routine care consisting of booklets and access to community treatments | Abstinence rates were nominally but not significantly higher for the intervention group at each assessment (point prevalence abstinence at 6 months 9.5% v 4%, odds ratio 2.54, 99% CI 0.70 to 9.28; at 12 months 10.9% v 6.6%, 1.72, 0.58 to 5.09); those in the active arm who attended all sessions had significantly higher abstinence rates than controls at each follow-up point (point prevalent abstinence at 6 months: 18.6%, 5.51, 1.45 to 20.91) | More patients in the treatment group achieved 50% reductions in smoking rate than those in the control group; atypical medication status did not moderate abstinence or attendance; in both groups, NRT use was associated with smoking reduction; functioning and symptoms improved across time in both groups |

| Horst et al 200517 | 50 | 12 week treatment with open label NRT (up to 63 mg/day patch) plus weekly group psychoeducation; those who quit entered single blind randomization to NRT or placebo for up to 6 additional months, with biweekly psychoeducation | 36% abstinence at the end of the 90 day open label phase; at end of the relapse prevention phase, 67% of the NRT group remained abstinent v 0% of the placebo group (P<0.01) | Conventional v atypical antipsychotic drug type did not affect outcome; no participants on NRT discontinued due to adverse events |

| Williams et al 201033 | 100 | 26 week treatment with a 24 session program combining motivational, cognitive behavioural, and psychoeducational elements or a 9 session medication management program; both groups received NRT (21 mg patch) for 16 weeks; treatment was provided by mental health clinicians | 16% of those in the higher intensity treatment and 26% of those in the lower intensity treatment arm had continuous abstinence at 12 weeks after the target quit day (NS); continuous abstinence rates were 17% at 6 month follow-up and 14% at 12 month follow-up, with no difference between groups | No effects of treatment or abstinence on psychiatric symptoms; higher session attendance was associated with higher cessation rate at 3 month follow-up, regardless of treatment condition |

*Abbreviations: ALA=American Lung Association; CBT=cognitive behavioral therapy; CI=confidence interval; CPD=cigarettes per day; NRT=nicotine replacement therapy; NS=not significant.

Three studies in 24-65 outpatients found quit rates of 9-14% at six month follow-up assessments,11 12 13 and one study in 68 outpatients found a 23% continuous abstinence rate at three month follow-up.14 In the largest smoking study in this population, 298 outpatients with a psychotic disorder (57% with schizophrenia) were randomized to routine care or to 10 weeks of treatment with motivational interviewing and CBT plus NRT.15 At the 12 month follow-up assessment, abstinence was not significantly higher in the treatment group (10.9 v 6.6% for the control condition; odds ratio 1.72, 99% confidence interval 0.58 to 5.09), but significantly more people in the treatment group had reduced the number of cigarettes they smoked each day by half (2.09, 99% confidence interval 1.03 to 4.27). When people in this study were re-contacted four years after treatment, 18% were abstinent. Abstinence at the 12 month follow-up was significantly associated with abstinence at four years, but treatment group did not predict four year outcomes.16 Overall, these studies indicate that average six to 12 month quit rates with treatments that include NRT are about 13% in smokers with schizophrenia. However, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from these studies owing to the lack of a placebo group.

One placebo controlled study investigated the efficacy of NRT for the prevention of relapse in smokers with schizophrenia.17 Fifty outpatients received nicotine patches that delivered 14-63 mg per day for 90 days along with weekly group motivational support. Those who quit (36%) were then randomized to continue receiving nicotine patches (same dose) or to receive placebo patches, along with biweekly group support, for another six months. At the end of this period, significantly more people receiving NRT remained abstinent compared with those receiving placebo (67% v 0%; P<0.01). These results show that prolonged NRT is feasible and reduces relapse in this population.

Bupropion

Bupropion, a weak dopamine and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) reuptake inhibitor and antagonist at α3β2 and α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), attenuates withdrawal symptoms and nicotine reinforcement.18 Table 2 shows the outcomes from open label and placebo controlled trials with bupropion in smokers with schizophrenia.

Table 2.

Outcomes of smoking cessation trials of treatment with bupropion alone or combined with NRT in outpatients with schizophrenia*

| Study | N | Intervention | Abstinence rates | Other outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weiner et al 200119 | 9 | 14 week treatment with open label bupropion (150 mg BID) and 9 weekly group psychoeducational therapy sessions; no control | 89% completed treatment; no patient quit smoking | Average breath CO levels decreased by half during treatment; schizophrenia symptom scores and neurocognitive measures were unchanged |

| Evins et al 200120 | 19 | 12 week randomized double blind placebo controlled trial with bupropion (150 mg/day) and 9 weekly CBT sessions | All of those who received at least one dose of drug completed treatment; continuous abstinence rates at 6 months were 11% for bupropion v 0% for placebo (NS) | 33% of bupropion group and 11% of placebo group had biochemically confirmed 50% reduction in CPD at 6 months (P<0.001); psychiatric symptoms decreased in the bupropion group and increased in the placebo group during treatment; there were no serious adverse events; 2 patients/group increased antipsychotic drug dose during the trial |

| George et al 200222 | 32 | 10 week randomized double blind placebo controlled treatment with bupropion (150 mg BID) and weekly CBT | 78% completed treatment; abstinence rates were significantly higher for bupropion at end of treatment (point prevalent abstinence 50% v 12.5%, P<0.05; continuous abstinence 37.5% v 6.3%, P<0.05) but not at 6 months (18.8% v 6.3%, P=0.29) | End of trial point prevalence abstinence rates were 67% for bupropion v 20% for placebo (P<0.01) in those taking atypical antipsychotics and 0% for both groups in those taking conventional antipsychotics; bupropion was associated with reduced negative symptoms and no effects on positive or other symptoms |

| Evins et al 200523 | 57 | 12 week randomized double blind placebo controlled treatment with bupropion (150 mg BID) and weekly CBT | 81% of those who received at least one week of drug completed treatment; point prevalence and 4 week continuous abstinence rates at end of treatment were higher in the bupropion group than in the placebo group (16% v 0% for both measures; P<0.05); at follow-up 3 months after end of the intervention, abstinence rates were 4% for bupropion and placebo (NS) | Breath CO levels were lower in the bupropion group than the placebo group during treatment, particularly in those taking atypical antipsychotics; the bupropion group tended to have greater reductions in psychiatric symptoms than the placebo group |

| Evins et al 200724 | 51 | 12 week randomized double blind placebo controlled treatment with bupropion (150 mg BID) + NRT (21 mg patch + gum) or placebo + NRT; all received weekly CBT | 71% of those who received at least one week of drug completed treatment; no significant differences between groups in abstinence rates at week 12 (36% v 19%), week 24 (20% v 8%), or week 52 (12% v 8%) | More patients in the bupropion + NRT arm had 50% reduction in CPD at 6 month follow-up (32% v 8%, P<0.05); there were no effects of bupropion or abstinence on psychiatric symptoms |

| George et al 200825 | 59 | 10 week randomized double blind placebo controlled treatment with bupropion (150 mg BID) + NRT (21 mg) or placebo + NRT; all received weekly CBT | 72% of those who received at least one drug dose completed treatment; continuous abstinence rates were higher for bupropion + NRT at end of treatment (27.6% v 3.4%, odds ratio 10.67, 95% CI 1.24 to 91.98) but not significantly higher at 6 month follow-up (13.8% v 0%) | No effects of drug treatment or abstinence on schizophrenia or depression symptoms |

| Weiner et al 201226 | 52 | 12 week randomized double blind placebo controlled treatment with bupropion (150 mg BID) plus psychoeducation and support sessions; nicotine gum was also available but no patient chose to use it | 78% of those who received at least one drug dose completed treatment; continuous abstinence rates (18% for bupropion, 11% for placebo) point prevalence abstinence, and other measures did not differ between groups | No effects of bupropion on psychiatric symptoms or neuropsychological measures |

| Cather et al 201327 | 41 | 12 week open label treatment with bupropion + NRT (21 mg patch with gum or lozenge) and CBT; those abstinent at 3 months received another 12 months of pharmacotherapy and CBT; no control arm | 42% were abstinent at 3 months and entered the relapse prevention phase; at end of the 12 month relapse prevention phase, 65% of patients had biochemically confirmed 7 day point prevalent abstinence and 59% reported 4 week continuous abstinence | No worsening of psychiatric symptoms; one participant had an adjustment in antipsychotic drugs during week 24 |

*Abbreviations: BID=twice a day; CBT=cognitive behavioral therapy; CI=confidence interval; CPD=cigarettes per day; NRT=nicotine replacement therapy; NS=not significant.

An early observational study (2001; n=9) with open label bupropion found that although no patients achieved abstinence, average breath carbon monoxide (CO) levels were reduced by half.19 A placebo controlled trial (n=19) performed at the same time also reported that although bupropion did not significantly increase abstinence, it significantly reduced breath CO levels (P<0.001) at follow-up.20 Furthermore, a follow-up assessment two years later found that those who had reduced smoking initially were more likely to achieve abstinence P<0.005).21

Two placebo controlled trials in 32 and 57 smokers with schizophrenia found that bupropion significantly increased continuous abstinence during treatment (P<0.05), although these effects were not maintained at the three to six month follow-ups.22 23 Similarly, two trials that compared bupropion plus NRT with placebo plus NRT in smokers with schizophrenia found that bupropion plus NRT significantly increased the odds of continuous abstinence during treatment (table 2) but not at the three to 12 month follow-ups.24 25 Somewhat surprisingly, the effects of bupropion plus NRT were not superior to those of bupropion alone seen in an earlier study.22

Finally, a placebo controlled trial of bupropion in 52 patients, in which nicotine gum was also available but no patient chose to use it, found that continuous abstinence rates during the last four weeks of treatment were not significantly different.26

Overall, the results from most placebo controlled studies of bupropion, with or without NRT, in smokers with schizophrenia indicate that bupropion increases initial abstinence but that relapse rates are high after treatment is discontinued. This suggests that smokers with schizophrenia require prolonged treatment.

In an observational study that examined the efficacy of extended open label bupropion plus NRT, 41 smokers with schizophrenia received bupropion plus NRT (patch plus gum or lozenge) and CBT for three months. At the end of this period, those who were abstinent (42%) entered a 12 month relapse prevention phase with bupropion plus NRT and CBT.27 At the 12 month assessment, 59% had achieved four weeks of continuous abstinence. Although this study lacked a placebo group the results, along with those from an earlier study of NRT for relapse prevention,17 support the approach of using prolonged pharmacological treatment to reduce relapse in smokers with schizophrenia.

Varenicline

Varenicline, a partial agonist at α4β2 nAChRs and full agonist at α7 nAChRs,28 substitutes for and blocks the reinforcing effects of nicotine, and is more effective than bupropion or single forms of NRT in the general population.29 Table 3 shows the outcomes from trials of varenicline in smokers with schizophrenia.

Table 3.

Outcomes of smoking cessation trials of treatment with varenicline in outpatients with schizophrenia*

| Study | N | Intervention | Abstinence rates | Other outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weiner et al 201130 | 9 | 12 week randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled treatment (1 mg BID) and individualized counseling based on the ALA “Freedom from Smoking” program | 89% of those randomized completed treatment; 75% of varenicline group and 0% of placebo group achieved continuous abstinence during the last 4 weeks of treatment (P=0.14) | Significant treatment by time interaction on breath CO level (P<0.05); no differences between groups on positive symptoms, anxiety, or depression; no incidence of suicidal ideation; side effects were similar to those reported in the general population |

| Williams et al 201231 | 128 | 12 week randomized double blind placebo controlled treatment (1 mg BID) and weekly counseling | 77% of those who received at least one dose of medication completed the treatment, with no difference between groups; point prevalence abstinence rates were significantly higher for varenicline at end of treatment (19% v 4.7%; P<0.05) but not at 6 month follow-up (11.9% v 2.3%; P=0.09) | Rates of adverse events were similar across conditions; 2 patients in the varenicline group had 3 serious adverse events considered to be related to treatment (1 suicide attempt) versus 0 in the placebo group; there was one unrelated death; rates of suicidal ideation during active treatment did not differ between groups; positive, negative, and extrapyramidal symptoms were stable or reduced in both groups |

| Evins et al 201432 | 247 | 12 week randomized double blind placebo controlled relapse prevention study; those meeting abstinence criteria at the end of a 12 week phase with open label varenicline (1 mg BID) and CBT entered a relapse prevention phase, in which they received varenicline (1 mg BID) or placebo plus CBT from week 12 to week 52 | Of 203 patients who engaged in treatment, 87 patients had ≥2 weeks’ continuous abstinence at the end of the open label phase and entered the relapse prevention phase; point prevalence abstinence rates were higher for varenicline at week 52 (60% v 19%; odds ratio 6.2, 95% CI 2.2 to 19.2); continuous abstinence rates were higher for varenicline during weeks 12-52 (45% v 15%; 4.6, 1.5 to 15.7), weeks 12-64 (40% v 11%; 5.2, 1.6 to 20.4), and weeks 12-76 (30% v 11%; 3.4, 1.02 to 13.6) | No differences between groups on psychiatric symptoms, health, body mass index, or nicotine withdrawal; 11 patients were admitted to hospital during the randomized phase—2 on varenicline and 2 on placebo for medical events, and 2 on varenicline and 5 on placebo for psychiatric events; 4% reported suicidal ideation during the open label phase and 5-6% in the relapse prevention phase, but there were no suicide attempts |

*Abbreviations: ALA=American Lung Association; BID=twice a day; CBT=cognitive-behavioral therapy; CI=confidence interval; CO=carbon monoxide.

A placebo controlled trial (n=9) found that three in four smokers with schizophrenia taking varenicline achieved continuous abstinence during the last four weeks of the treatment period compared with no patients taking placebo (P=0.14). A significant reduction was seen in breath CO levels after four weeks of treatment in the varenicline group compared with the placebo group (P=0.02) and no increases were seen in psychiatric symptoms or suicidal ideation.30

A multi-site placebo controlled trial of varenicline with brief counseling in 128 smokers with schizophrenia found that varenicline significantly increased point prevalence abstinence at the end of treatment (19% v 4.7%; P<0.05) but not at the six month follow-up.31 Rates of adverse events were similar across conditions (see table 3), and schizophrenia symptoms were stable or decreased in both groups.

Finally, a recent 10 site placebo controlled trial investigated whether varenicline reduces smoking relapse.32 In total, 247 patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were enrolled and 203 entered the open label treatment phase. Of these, 87 (43%) attained two weeks of continuous abstinence and entered the relapse prevention phase, in which they were randomized to varenicline or placebo with CBT. At week 52, point prevalence abstinence rates were significantly higher in people taking varenicline (60% v 19%; odds ratio 6.2, 95% confidence interval 2.2 to 19.2), and rates of continuous abstinence from week 12 to 76 were also higher (30% v 11%; 3.4, 1.02 to 13.6). Varenicline had no effect on psychiatric symptoms. Two patients in each group reported suicidal ideation during the maintenance phase but there were no suicide attempts. Thus, among smokers with schizophrenia who attained abstinence, varenicline was well tolerated and increased prolonged abstinence for as long as 76 weeks.32

Studies comparing psychosocial treatments

All of these studies included a psychosocial component, usually CBT, but few studies have compared the efficacy of different psychosocial treatments. One study in 45 people found that smokers with schizophrenia who received tailored treatment tended to have higher continuous abstinence at the end of treatment than those receiving the American Lung Association (ALA) “Freedom from Smoking” program, but these effects were reversed at six month follow-up.13

Another study in 87 people compared higher versus lower intensity behavioral treatment in smokers with schizophrenia who received NRT for 16 weeks and found no difference on abstinence.33 Yet another study in 78 people compared the effects of a 40 minute motivational interviewing session, a 40 minute psychoeducational counseling session, and a five minute advice only session on seeking cessation treatment in smokers with schizophrenia. This study found that those who received motivational interviewing were significantly more likely to seek and attend cessation treatment than those who received the other treatments (P<0.05). This indicates that a single session of motivational interviewing increases the likelihood that these patients will seek cessation treatment.34

Contingency management is an approach in which monetary or other reinforcement is provided when a patient meets an objectively measured therapeutic target, such as biochemical evidence of drug abstinence. The results of proof of concept studies of this approach for smoking cessation in smokers with schizophrenia were promising.35 36 These studies were therefore followed by a study that compared contingency management alone, contingency management plus NRT, and self help (control) in 180 smokers with schizophrenia who were treated in a behavioral healthcare setting.37 Those receiving contingency management were significantly more likely to meet the CO criterion for abstinence than those in the control group (P<0.001) but were not more likely to meet the cotinine criterion, suggesting that they abstained only long enough to earn the monetary incentive. A study that investigated the separate and combined effects of cotinine based contingency management and bupropion over a three week period in smokers with schizophrenia found that contingency management significantly reduced cotinine levels (P<0.01). This suggests that longer trials are warranted to examine whether contingency management is an effective stand alone or adjunctive treatment for smoking cessation in this population.38

Summary of cessation outcomes in smokers with schizophrenia

No trials have directly compared the efficacy of NRT, bupropion, and varenicline in smokers with schizophrenia. However, a systematic review found that bupropion is associated with a threefold increase in cessation in smokers with schizophrenia (risk ratio 3.03, 1.69 to 5.42 at end of treatment; 2.78, 1.02 to 7.58 at six months). It also found that varenicline is associated with an almost fivefold increase in cessation (4.74, 1.34 to 16.71 at end of treatment).39 NRT seems to have a smaller effect in smokers with schizophrenia than in the general population, although no studies have directly compared how these groups respond to NRT. Moreover, although NRT is the recommended first line treatment for smoking cessation in smokers with psychiatric comorbidities,40 no placebo controlled trials of NRT have been carried out in this population, and such studies are long overdue.

Several other findings are also noteworthy. Firstly, several studies noted correlations between treatment attendance and abstinence.12 15 33 Although this could be due to a direct effect of treatment or to underlying characteristics of patients who attend more versus fewer sessions, the provision of small financial incentives for treatment attendance is an effective method of increasing attendance.20 27

Secondly, several studies indicate that long term maintenance on smoking cessation pharmacotherapies is feasible, effective, and safe in this population.17 27 32 Finally, several studies reported that many patients who were not able to quit completely greatly reduced their smoking. The question of whether a reduction in smoking might be an acceptable outcome for smokers with schizophrenia who were unable to quit was posed more than a decade ago,41 and this question is still valid today. Although it is unclear whether a reduction in smoking alone improves health, a large reduction could decrease the severity of nicotine dependence and increase motivation to quit, thereby increasing the likelihood of future abstinence.42 43 This notion is corroborated by a study that found that smokers with schizophrenia who had initially reduced their intake were more likely to have quit at a two year follow-up assessment.21

Mechanisms underlying the schizophrenia-smoking comorbidity

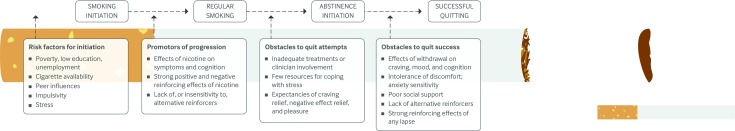

Schizophrenia is associated with social and environmental vulnerability factors for smoking, such as poverty, low education, unemployment, and lack of clinical attention to tobacco use (figure ).44 The contributions of these factors to smoking in people with schizophrenia have not been sufficiently studied, because laboratory studies have focused primarily on neurobiological factors that may contribute to smoking in this population.

Factors involved in the initiation and progression of smoking in patients with schizophrenia and the obstacles to attempts to quit and quit success

The higher nicotine metabolite levels seen in smokers with schizophrenia relative to other smokers10 are the result of more intense cigarette puffing characteristics, particularly short inter-puff intervals.45 46 The functional importance of these patients’ higher nicotine intake is unknown, but it is often attributed to attempts to remediate psychiatric symptoms, cognitive deficits, or the sedating effects of antipsychotic drug.47 48

Nicotine improves sensory gating in smokers with schizophrenia through effects at α7 nAChRs,49 50 and it may improve negative symptoms and cognitive performance through stimulation of β2 nAChRs and downstream effects on cortical dopamine.51 52 53 In support of this idea, smokers with schizophrenia are more sensitive than smokers without psychiatric problems to the effects of nicotine abstinence and replacement with regard to some cognitive performance measures,54 55 although this is not universally observed.56 Smoking initiation generally precedes the onset of schizophrenia, which supports the idea that common neurobiological vulnerability factors underlie this comorbidity, but early initiation may also be a marker of the prodromal phase of schizophrenia.57 58

Reasons for smoking in people with schizophrenia

The neuropathology of schizophrenia might result in smokers with schizophrenia experiencing stronger reinforcing effects of nicotine.59 60 This hypothesis is supported by a study in which smokers with schizophrenia and smokers with depression made twice as many hypothetical choices for smoking over alternative reinforcers, such as receiving candy or seeing a movie, than did controls without psychiatric disorders.61 However, another interpretation of these findings is that smokers with schizophrenia and smokers with depression experience less pleasure from non-smoking activities (anhedonia).

Many studies have asked people with schizophrenia why they smoke in order to gain insight into the mechanisms that underlie the high smoking rates in these people. In a recent analysis of smoking motives from a large combined dataset, smokers with psychotic disorders cited coping motives (smoking to reduce craving and negative affect) as the main reason for smoking and pleasure motives as secondary. Illness motives (smoking to reduce psychiatric symptoms or side effects of antipsychotic drugs) were less commonly cited.62 Smokers with depression ranked these motives in the same order as those with schizophrenia but endorsed them at significantly lower rates (P<0.001-0.05).62 Studies that use ecological momentary assessment techniques to compare antecedents of smoking in patients with these disorders would help to clarify common and unique factors associated with smoking in these groups.

Reasons for relapse

During abstinence the effects of nicotine withdrawal on negative affect, cigarette craving, and cognitive functioning may contribute to early relapse in smokers with schizophrenia (figure). A study that provided high value monetary incentives for abstinence over a three day period to compare the effects of abstinence in smokers with schizophrenia and controls without a psychiatric disorder found that those with schizophrenia reported higher levels of negative affect and craving to relieve negative affect during abstinence.63 Other than a small increase in anergia, psychiatric symptoms were not affected, consistent with a previous study.64

The negative effects of abstinence on cognitive functioning in smokers with schizophrenia, described above, may also contribute to early relapse, because smoking cessation requires considerable task persistence and other executive functions that are impaired in smokers with schizophrenia even before they try to quit.65 66 In addition, patients with schizophrenia experience stronger nicotine reinforcement and a greater increase in positive mood from restarting smoking after abstinence than controls do.63 These studies suggest that high levels of negative affect and craving, along with expectancies that smoking will improve these states; executive functioning deficits that are exacerbated during abstinence; and strong reinforcing effects of smoking after a period of abstinence may contribute to the high rates of relapse in this population.

However, conclusions from studies that examine the mechanisms underlying smoking in people with chronic mental illness are limited. Most laboratory studies do not examine the extent to which social-environmental factors contribute to differences seen between patient and control groups with regard to these biological mechanisms.

Unipolar and bipolar depression

Mood disorders such as unipolar and bipolar depression are generally associated with reduced smoking cessation rates compared with the general population,1 5 although this difference is modest in those who enter formal cessation treatment.67 Smokers with recurrent depression have higher levels of nicotine dependence and make fewer cessation attempts than do smokers with single episode depression,68 and those who have difficulty tolerating distress are particularly vulnerable to early smoking lapse.69

Unipolar depression

A recent narrative review examined the efficacy of smoking cessation treatments in smokers with unipolar depression from 68 studies published between 1990 and 2010.70 Although most studies found no differences in smoking cessation outcomes between people with and without depression, in those studies that did detect a difference, depression was associated with poorer outcomes, particularly in women.70

Regarding the relative effectiveness of particular treatment approaches, a meta-analysis of treatment trials in smokers with unipolar depression published in 2010 found that NRT was more effective than placebo, and that adding behavioral mood management to cessation counseling improved treatment outcomes.71 In addition, bupropion and nortriptyline are effective treatments for smoking in people with unipolar depression.72 73 It is important to note that most studies have focused on lifetime depression; very few have examined the effects of current depression on smoking cessation.70 71 Although relapse rates are high in this population, long term treatment with bupropion reduces relapse rates in those who attain abstinence.74

A recent multisite placebo controlled trial examined the effects of 12 weeks of treatment with varenicline on smoking in 525 people with stable current or past major depression.75 Attrition from the study was high (almost a third) but did not differ between groups. Varenicline significantly increased continuous abstinence during the last four weeks of treatment (35.9% v 15.6%; odds ratio 3.35, 2.16 to 5.21) and up to week 52 (2.36, 1.40 to 3.98), without exacerbating depression or anxiety.75 Thus, although early concerns about associations with suicidality and depression76 led to a Food and Drug Administration black box warning, this study provides evidence that varenicline is a well tolerated and effective treatment for smoking cessation in people with stable current or past depression.

Bipolar depression

Fewer studies have examined smoking cessation treatments for smokers with bipolar disorder. Two placebo controlled trials of bupropion and varenicline with only five patients per study, and an open label trial of varenicline in nine patients, showed promising results and no exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms.77 78 79 These were followed by a placebo controlled trial of varenicline in 60 stable patients with bipolar disorder, which found that varenicline significantly increased abstinence at the end of treatment (48% v 10%; 8.13, 2.03 to 32.53), although this difference was no longer significant at six months (19% v 7%; 3.2, 0.60 to 17.6).80 Varenicline was associated with a higher frequency of abnormal dreams (P=0.04) and a non-significant trend toward more negative mood events (P=0.08), but otherwise the groups did not differ with regard to treatment emergent or serious adverse events. Eight people in the varenicline group and five in the placebo group had suicidal ideation during the trial (not significant).80 Maintenance treatment with varenicline has also been found to reduce relapse in smokers with bipolar disorder who attained abstinence.32

Mechanisms underlying the depression-smoking comorbidity

Associations between unipolar or bipolar depression and cigarette smoking may be due to biological and social-environmental factors that increase the risk of both disorders, smoking to reduce psychiatric symptoms, effects of nicotine or smoke exposure on the development of these disorders, or bidirectional causality.81 82 83 84 85 Like smokers with schizophrenia, smokers with unipolar depression indicate that they smoke primarily to cope with craving and negative affect, and secondarily for pleasure.62 However, they are as worried as smokers without depression about the effects of smoking on their health and equally motivated to quit.86 87

Effects of withdrawal

When they try to quit, smokers with unipolar depression, particularly women, report more severe withdrawal than those without depression and are more likely to attribute the reinitiation of smoking to withdrawal.88 89 90

The effects of smoking and abstinence on mood are regulated through the effects of nicotine on monoamines and the neuroendocrine system.91 Chronic nicotine desensitizes or inactivates nAChRs, and this has an antidepressant effect through actions on dopamine and other monoamines.91 92 Furthermore, abstinence increases levels of monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), an enzyme that metabolizes dopamine and other monoamines, and this is correlated with a shift towards depressed mood.93

Once withdrawal symptoms fade, abstinence does not seem to be associated with exacerbation of depression for most smokers, although considerable heterogeneity exists, and those who do experience worsening of symptoms have poorer cessation outcomes.94 Recent epidemiological studies and systematic reviews have concluded that in people with stable depression successful cessation may be associated with improvement in mood.95 96 However, the direction of causality in this association has not been determined—cessation may improve mood, or those who do not experience mood deterioration while attempting to quit may be more likely to remain abstinent.

Reinforcing effects of smoking

In addition to experiencing stronger withdrawal symptoms during initial abstinence, smokers with depression may experience stronger relative reinforcing effects of smoking. Experimental studies indicate that smokers with a history of depression are more likely than smokers without depression to choose smoking over various alternative reinforcers, such as seeing a movie or receiving candy.61 They are also more likely to smoke more cigarettes in laboratory sessions regardless of mood,97 and they have higher levels of appetitive cigarette craving (craving for the positive reinforcing effects of smoking) shortly after smoking than do controls.98

Depression is associated with low resting levels of intrasynaptic dopamine,99 100 and smokers with depression experience larger increases in striatal dopamine after smoking a cigarette than those without a history of depression, which may underlie these heightened reinforcing effects.101 Regardless of diagnosis, anhedonia, defined as a deficit in positive emotion in response to pleasant stimuli, is associated with enhanced sensitivity to the effects of nicotine on positive mood, appetitive craving during abstinence, and rapid relapse.102 103 104

In addition, people with anhedonia have more difficulty identifying reinforcing activities to substitute for smoking during quit attempts.105 Together, these studies suggest that high levels of withdrawal related negative affect, low tolerance of discomfort, vulnerability to smoking reinforcement, and insensitivity to alternative reinforcers contribute to cessation failure in people with depression (figure). Therefore, in addition to pharmacotherapy and mood management, smokers with depression may benefit from treatments that help them to identify and engage in alternative reinforcing activities.

Other factors that contribute to persistence of smoking

Far fewer human laboratory studies have examined mechanisms that underlie smoking in people with bipolar disorder than in those with schizophrenia or unipolar depression. Smoking is associated with greater severity of mood symptoms, comorbid psychiatric and addictive disorders, and suicidality in people with bipolar disorder.106 107 108 109 110 111 Furthermore, in an online survey of 685 patients with bipolar disorder, almost half reported that they smoked to manage symptoms of their mental illness.112 This study also found that although 74% of the patients surveyed wanted to quit smoking, only 33% had received medical advice to quit, suggesting that lack of clinical attention probably contributes to smoking persistence in this population.112 Unlike some studies in smokers with schizophrenia, smokers with bipolar and unipolar depression do not differ from controls with regard to the effects of smoking status on neuropsychiatric performance. This suggests that pro-cognitive effects of nicotine may not contribute to smoking in this population.113

Anxiety disorders

Whereas smoking rates significantly declined from 2004 to 2011 in people without psychiatric illness, they did not decrease in those with anxiety disorders.6 Consequently, the presence of anxiety disorders among current smokers has significantly increased, more markedly in women.114

A secondary analysis of data collected from a large trial of 1504 smokers that compared monotherapy and combination pharmacotherapies for smoking focused on whether psychiatric disorders moderated treatment response.115 After controlling for treatment, age, sex, and ethnicity, smokers with lifetime anxiety disorder had significantly lower rates of abstinence than those with no psychiatric history at eight weeks (39.9% v 47.4%; odds ratio 0.72, 0.55 to 0.94) and six months (28.7 v 35.4%; 0.72, 0.54 to 0.95) after their target quit date. Lifetime history of anxiety disorder remained a predictor of poorer outcome at both follow-up points after controlling for lifetime mood or substance use disorders.

A more detailed analysis of smoking outcomes and risk factors in patients with specific anxiety diagnoses (panic attacks, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder) indicated that those with social anxiety or generalized anxiety disorders had more severe nicotine dependence at baseline. In addition, patients with any of the three diagnoses had higher negative affect and withdrawal symptoms before quitting than did smokers without anxiety disorders.116

Smokers with anxiety disorder also reported greater increases in cessation fatigue (being tired of trying to quit smoking) before and after the quit day, suggesting that these patients may not have adequate coping resources. Interestingly, although combination pharmacotherapy doubled the likelihood of abstinence compared with placebo in smokers without anxiety disorders, neither monotherapy nor combination pharmacotherapy was more effective than placebo in those with a lifetime history of anxiety disorder.116 Similarly, in smokers with unipolar depression, the presence of comorbid anxiety disorder was associated with poorer response to combined bupropion and NRT.117

Mechanisms underlying the anxiety-smoking comorbidity

Studies suggest that people with anxiety disorder may smoke to reduce anxiety, that smoking or smoke exposure in early life may increase the likelihood of developing an anxiety disorder, and that shared vulnerabilities may increase the risk of both.118 119

Biological mechanisms that have been proposed to underpin the association between anxiety disorders and smoking include effects on several neurotransmitter systems, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and epigenetic effects.120 In particular, given that a reduction in acetylcholine transmission improves affect, dysregulation of this system is probably one of the causes of anxiety disorders.92

Negative reinforcement models

Most research on smoking and anxiety focuses on negative reinforcement models, such as smoking to cope with negative affect or to feel comfortable in social situations.121 122 123 124 For example, a longitudinal study of peer use as a moderator of the associations between anxiety and substance use in adolescence found that girls with high social anxiety were more likely to smoke when they believed that peer approval of smoking was high, and less likely when they believed it was low.125 However, girls with generalized anxiety symptoms responded to perceptions about peer smoking in the opposite direction, highlighting the variability across anxiety diagnoses.125 People who have high anxiety sensitivity, or fear of anxiety or related sensations, are also highly motivated to smoke to reduce negative affect and anxiety related distress.121 122 124

When smokers with anxiety disorder try to quit they report more severe withdrawal symptoms than those without an anxiety disorder,88 90 126 although data on whether increased withdrawal in this population influences relapse to smoking are conflicting.88 127

Reasons for relapse

Laboratory and treatment studies have also found that smokers with anxiety disorder have higher levels of cigarette craving and nicotine withdrawal symptoms during abstinence than those without anxiety disorder.116 126 128 However, these differences are also seen before cessation and may reflect exaggerated tonic levels of withdrawal-like symptoms.116 Taken together, these studies suggest that high levels of negative affect during abstinence, combined with beliefs that these symptoms are associated with harm (anxiety sensitivity129 130) and the expectancy that smoking will reduce negative affect, probably contribute to rapid relapse during cessation attempts (figure).

PTSD

Only four randomized clinical trials have investigated the efficacy of smoking cessation interventions in smokers with PTSD. Two of these studies focused on integrating cessation treatment into ongoing mental healthcare, an approach that leverages pre-existing therapeutic relationships and an established visit schedule. In the first trial, 66 veterans with PTSD were randomized to integrated care modeled on clinical practice guidelines or to standard care. Abstinence was five times higher in the integrated care group nine months after randomization.131 A larger, multi-site trial in 943 smokers with PTSD found that the integrated care group achieved significantly higher abstinence at six months (16.5% v 7.2% for standard care; P<0.001), but more than 90% were not abstinent at 12 months.132

The integrated care interventions offered smoking cessation pharmacotherapy to those who were interested but did not randomize patients to drugs versus placebo. The only randomized placebo controlled trial of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy in smokers with PTSD was a pilot study in 15 veterans who received 12 weeks of treatment with bupropion.133 Bupropion was well tolerated and associated with 40% abstinence, versus 20% for placebo at six months of follow-up (level of significance not reported).

More recently, 22 smokers with PTSD were randomized to a four week contingency management intervention or a control group that received reinforcement independent of abstinence.134 All participants also received two smoking cessation counseling sessions, along with NRT and bupropion. At three months, abstinence rates were not significantly different (55% in the contingency management group v 18% in the control group).134 However, the size of the difference suggests that the lack of significance may be due to the small sample size and that fully powered trials should be conducted to examine whether contingency management is an efficacious cessation treatment for smokers with PTSD.

Mechanisms underlying the PTSD-smoking comorbidity

Smokers with PTSD have higher levels of depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms than non-smokers with PTSD.135 136 Both a diagnosis of PTSD and symptom severity are associated with stronger desire to smoke in order to reduce negative affect.122 136 137 138 Using baseline data from the multi-site study described above,132 the expectancy that smoking would reduce negative affect was found to mediate the association between severity of PTSD and nicotine dependence and the negative association between severity of PTSD and abstinence self efficacy in situations involving affective distress.139 Studies using ecological momentary assessment in the natural environment show that smokers with PTSD smoke in response to negative affect and trauma reminders.140 141 Taken together, these studies strongly suggest that people with PTSD smoke to cope with negative affect and anxiety. Cognitive and attentional deficits associated with PTSD may also contribute to smoking in this population.142 143 Because nicotine enhances cognition and attention, smoking cessation may exacerbate cognitive deficits,144 although one study found that smokers with PTSD did not experience stronger deleterious effects of abstinence on prepulse inhibition than did other smokers.145 Finally, smokers with PTSD report higher craving and withdrawal during abstinence than do smokers without PTSD.146

Emerging treatments

Smoking cessation is clearly the most effective way to reduce the risk of tobacco related disease. However, reductions in smoking or a switch to non-combustible sources of nicotine may be acceptable proximal outcomes for those who are unable to quit, if these reduce exposure to tobacco toxicants or lead to eventual abstinence.41 42

E-cigarettes

E-cigarettes may have fewer cardiovascular and respiratory effects than traditional cigarettes and may help people quit smoking,147 148 although we currently have little empirical evidence about their safety and efficacy. A small uncontrolled study found that 50% of smokers with schizophrenia who were provided with e-cigarettes for 52 weeks reduced their smoking by 50%, and 14% quit, with no increases in psychiatric symptoms.149 These preliminary findings are noteworthy because none of the participants was initially seeking treatment for smoking, and they indicate that randomized controlled trials of the effects of e-cigarettes on smoking in this population are warranted.

Regulatory approaches

One potential regulatory approach to reducing tobacco dependence is to decrease the nicotine content of cigarettes to reduce their addictiveness.150 The 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act gave the US FDA the authority to regulate tobacco products, including the allowable levels of nicotine in cigarettes. Similarly, under Article 9 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the Conference of the Parties is charged with establishing guidelines for measuring and regulating the contents and emissions of tobacco products.151

A reduction in the nicotine content of cigarettes to a non-addictive level could reduce the severity of tobacco dependence, potentially making it easier for smokers to quit.152 153 This approach could be particularly beneficial to those who have inadequate access to and success with cessation treatments. However, one concern about this regulatory approach is that smokers with chronic mental illness may experience dysfunction as a result of nicotine withdrawal or may attempt to compensate for nicotine reduction by increasing their smoking intensity.

An initial study found that acute use of very low nicotine content cigarettes decreased withdrawal symptoms, cigarette craving, and smoking of usual brand cigarettes in smokers with schizophrenia without affecting psychiatric symptoms.154 Trials are under way to examine the effects of extended use of these cigarettes on smoking rates, toxicant exposure, psychiatric symptoms, and cognitive functioning in smokers with schizophrenia and affective disorders.

Conclusions

Treatment for tobacco addiction must be prioritized in clinical practice to reduce the high rates of tobacco related disease and premature death in people with chronic mental illness. The research reviewed here indicates that smokers with chronic mental illness can quit with standard cessation approaches, with minimal effects on psychiatric symptoms. In particular, recent randomized controlled trials have shown that bupropion and varenicline are effective in people with schizophrenia,31 32 39 and that varenicline is effective in people with unipolar and bipolar depression.75 80

Treatments for people with anxiety disorders and PTSD have been less well studied and the effects of these drugs in smokers with these disorders have not been determined using adequately powered randomized controlled trials. Small scale studies suggest that contingency management approaches may be effective in smokers with schizophrenia and PTSD if feasibility challenges associated with extending the duration of these interventions can be overcome.38 134

Most of the studies reviewed enrolled stable patients treated in university affiliated behavioral health programs. Whether similar effects will be seen with less stable patients and in settings with less patient contact remains to be determined. An important next step for treating smoking in people with chronic mental illness will therefore be to promote the adoption, implementation, and assessment of empirically supported smoking treatments within community behavioral healthcare settings.

Researchers who study the comorbidity between psychiatric disorders and tobacco often specialize in a particular psychiatric disorder, yet clinicians treat people with a variety of illnesses and multiple comorbidities. Thus, a goal of this review was to highlight commonalities between the biopsychosocial mechanisms involved in the initiation and persistence of smoking in patients with different disorders. An appreciation of these common factors may facilitate the identification of novel prevention and tobacco treatment approaches for these patients. Finally, given that many patients reduce their smoking rates during treatment and the use of novel tobacco and nicotine products may also reduce smoking rates, it is important to determine whether reductions in smoking increase the likelihood of eventual cessation in people with chronic mental illness.

Treatment guidelines

Treatobacco.net (http://treatobacco.net/en/index.php) is an independent source of evidence based information and support for the treatment of tobacco dependence throughout the world. The site’s resource library contains links to treatment guidelines from more than 30 countries, including the US Public Health Service sponsored Clinical Practice Guideline40 and the 2014 update to the 2011 guideline from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.155 Both of these guidelines include sections on treating smoking in people with mental illness and other vulnerable populations, and the Australian guideline has up to date information on the efficacy and safety of bupropion and varenicline in these populations. Other useful resources provided on the website include slide kits and summaries of efficacy and safety information, with links to relevant research studies.

Research questions

What are the antecedents and consequences of smoking in people with schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety disorders during cessation attempts?

Do reductions in smoking rates reduce biomarkers of tobacco related harm in people with chronic mental illness?

Do reductions in smoking rates increase the likelihood of future cessation attempts or cessation success in people with chronic mental illness?

Contributors: Both authors helped in all aspects of the review, approved the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The preparation of this paper was supported by grants U54DA031659 and P50DA036114 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products, and grant P20GM103644 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the FDA.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: JWT has received a consulting fee from Giner (2013).MEM has no competing interests.

Patient involvement: No patients were involved in the preparation of this article.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;351:h4065

Related links

thebmj.com

References

- 1.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, et al. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA 2000;284:2606-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health 2009;9:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartz SM, Pato CN, Medeiros H, et al. Comorbidity of severe psychotic disorders with measures of substance use. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:248-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the US population. Tob Control 2014;23:e147-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberger AH, Pilver CE, Desai RA, et al. The relationship of major depressive disorder and gender to changes in smoking for current and former smokers: longitudinal evaluation in the US population. Addiction 2012;107:1847-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, et al. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA 2014;311:172-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaghan RC, Veldhuizen S, Jeysingh T, et al. Patterns of tobacco-related mortality among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. J Psychiatr Res 2014;48:102-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly DL, McMahon RP, Wehring HJ, et al. Cigarette smoking and mortality risk in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2011;37:832-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Mitchell JE, et al. Prevalence of smoking among psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry 1986;143:993-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olincy A, Young DA, Freedman R. Increased levels of the nicotine metabolite cotinine in schizophrenic smokers compared to other smokers. Biol Psychiatry 1997;42:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziedonis DM, George TP. Schizophrenia and nicotine use: report of a pilot smoking cessation program and review of neurobiological and clinical issues. Schizophr Bull 1997;23:247-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Addington J, el-Guebaly N, Campbell W, et al. Smoking cessation treatment for patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:974-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George TP, Ziedonis DM, Feingold A, , et al. Nicotine transdermal patch and atypical antipsychotic medications for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:1835-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou K-R, Chen R, Lee J-F, et al. The effectiveness of nicotine-patch therapy for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Nurs Stud 2004;41:321-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker A, Richmond R, Haile M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention among people with a psychotic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1934-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker A, Richmond R, Lewin TJ, et al. Cigarette smoking and psychosis: naturalistic follow up 4 years after an intervention trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:342-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horst WD, Klein MW, Williams D, et al. Extended use of nicotine replacement therapy to maintain smoking cessation in persons with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2005;1:349-55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll FI, Blough BE, Mascarella SW, et al. Bupropion and bupropion analogs as treatments for CNS disorders. Adv Pharmacol 2014;69:177-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiner E, Ball MP, Summerfelt A, et al. Effects of sustained-release bupropion and supportive group therapy on cigarette consumption in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:635-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evins AE, Mays VK, Rigotti NA, et al. A pilot trial of bupropion added to cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Nicotine Tob Res 2001;3:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evins AE, Cather C, Rigotti NA, et al. Two-year follow-up of a smoking cessation trial in patients with schizophrenia: increased rates of smoking cessation and reduction. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:307-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George TP, Vessicchio JC, Termine A, et al. A placebo controlled trial of bupropion for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2002;52:53-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evins AE, Cather C, Deckersbach T, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bupropion sustained-release for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;25:218-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evins AE, Cather C, Culhane MA, et al. A 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study of bupropion SR added to high-dose dual nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation or reduction in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2007;27:380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George TP, Vessicchio JC, Sacco KA, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion combined with nicotine patch for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2008;63:1092-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiner E, Ball MP, Buchholz AS, et al. Bupropion sustained release added to group support for smoking cessation in schizophrenia: a new randomized trial and a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cather C, Dyer MA, Burrell HA, et al. An open trial of relapse prevention therapy for smokers with schizophrenia. J Dual Diagn 2013;9:87-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol 2006;70:801-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cahill K, Stevens S, Lancaster T. Pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation. JAMA 2014;311:193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiner E, Buchholz A, Coffay A, et al. Varenicline for smoking cessation in people with schizophrenia: a double blind randomized pilot study. Schizophr Res 2011;129:94-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams JM, Anthenelli RM, Morris CD, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the safety and efficacy of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:654-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evins AE, Cather C, Pratt SA, et al. Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311:145-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams JM, Steinberg ML, Zimmermann MH, et al. Comparison of two intensities of tobacco dependence counseling in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat 2010;38:384-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinberg ML, Ziedonis DM, Krejci JA, et al. Motivational interviewing with personalized feedback: a brief intervention for motivating smokers with schizophrenia to seek treatment for tobacco dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:723-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roll JM, Higgins ST, Steingard S, et al. Use of monetary reinforcement to reduce the cigarette smoking of persons with schizophrenia: a feasibility study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;6:157-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tidey JW, O’Neill SC, Higgins ST. Contingent monetary reinforcement of smoking reductions, with and without transdermal nicotine, in outpatients with schizophrenia. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2002;10:241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallagher SM, Penn PE, Schindler E, et al. A comparison of smoking cessation treatments for persons with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. J Psychoactive Drugs 2007;39:487-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tidey JW, Rohsenow DJ, Kaplan GB, et al. Effects of contingency management and bupropion on cigarette smoking in smokers with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;217:279-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Interventions for smoking cessation and reduction in individuals with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD007253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:158-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McChargue DE, Gulliver SB, Hitsman B. Would smokers with schizophrenia benefit from a more flexible approach to smoking treatment? Addiction 2002;97:785-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ. Does smoking reduction increase future cessation and decrease disease risk? A qualitative review. Nicotine Tob Res 2006;8:739-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asfar T, Ebbert JO, Klesges RC, et al. Do smoking reduction interventions promote cessation in smokers not ready to quit? Addict Behav 2011;36:764-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:1691-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tidey JW, Rohsenow DJ, Kaplan GB, et al. Cigarette smoking topography in smokers with schizophrenia and matched non-psychiatric controls. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;80:259-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams JM, Gandhi KK, Lu SE, et al. Shorter interpuff interval is associated with higher nicotine intake in smokers with schizophrenia. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011;118:313-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dalack GW, Healey DJ, Meador-Woodruff JH. Nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: clinical phenomena and laboratory findings. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:1490-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumari V, Postma P. Nicotine use in schizophrenia: the self-medication hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005;29:1021-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adler LE, Hoffer LD, Wiser A, et al. Normalization of auditory physiology by cigarette smoking in schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150:1856-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin LF, Freedman R. Schizophrenia and the a7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Int Rev Neurobiol 2007;78:225-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Esterlis I, Ranganathan M, Bois F, et al. In vivo evidence for B2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit upregulation in smokers as compared with nonsmokers with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2013;76:495-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D’Souza DC, Esterlis I, Carbuto M, et al. Lower B2*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor availability in smokers with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:326-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wing VC, Wass CE, Soh DW, et al. A review of neurobiological vulnerability factors and treatment implications for comorbid tobacco dependence in schizophrenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1248:89-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.George TP, Vessicchio JC, Termine A, et al. Effects of smoking abstinence on visuospatial working memory function in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002;26:75-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barr RS, Culhane MA, Jubelt LE, et al. The effects of transdermal nicotine on cognition in nonsmokers with schizophrenia and nonpsychiatric controls. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008;33:480-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hahn B, Harvey AN, Concheiro-Guisan M, et al. A test of the cognitive self-medication hypothesis of tobacco smoking in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2013;74:436-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beratis S, Katrivanou A, Gourzis P. Factors affecting smoking in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry 2001;42:393-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riala K, Hakko H, Isohanni M, et al. Is initiation of smoking associated with the prodromal phase of schizophrenia? J Psychiatry Neurosci 2005;30:26-32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chambers RA, Krystal JH, Self DW. A neurobiological basis for substance abuse comorbidity in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2001;50:71-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brunzell DH, McIntosh JM. Alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors modulate motivation to self-administer nicotine: implications for smoking and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012;37:1134-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spring B, Pingitore R, McChargue DE. Reward value of cigarette smoking for comparably heavy smoking schizophrenic, depressed, and nonpatient smokers. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:316-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thornton LK, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, et al. Reasons for substance use among people with mental disorders. Addict Behav 2012;37:427-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tidey JW, Colby SM, Xavier EM. Effects of smoking abstinence on cigarette craving, nicotine withdrawal, and nicotine reinforcement in smokers with and without schizophrenia. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:326-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dalack GW, Becks L, Hill E, et al. Nicotine withdrawal and psychiatric symptoms in cigarette smokers with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999;21:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moss TG, Sacco KA, Allen TM, et al. Prefrontal cognitive dysfunction is associated with tobacco dependence treatment failure in smokers with schizophrenia. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;104:94-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steinberg ML, Williams JM, Gandhi KK, et al. Task persistence predicts smoking cessation in smokers with and without schizophrenia. Psychol Addict Behav 2012;26:850-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hitsman B, Papandonatos GD, McChargue DE, et al. Past major depression and smoking cessation outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. Addiction 2013;108:294-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strong DR, Cameron A, Feuer S, et al. Single versus recurrent depression history: differentiating risk factors among current US smokers. Drug Alc Depend 2010;109:90-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: a transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion-smoking comorbidity. Psychol Bull 2014;141:176-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weinberger AH, Mazure CM, Morlett A, et al. Two decades of smoking cessation treatment research on smokers with depression: 1990-2010. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:1014-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gierisch JM, Bastian LA, Calhoun PS, et al. Smoking cessation interventions for patients with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2011;27:351-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brown RA, Niaura R, Lloyd-Richardson EE, et al. Bupropion and cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res 2007;9:721-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hall SM, Reus VI, Muñoz RF, et al. Nortriptyline and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of cigarette smoking. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:683-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cox LS, Patten CA, Niaura RS, et al. Efficacy of bupropion for relapse prevention in smokers with and without a past history of major depression. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:828-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anthenelli RM, Morris C, Ramey TS, et al. Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in adults with stably treated current or past major depression: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:390-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.US Food and Drug Administration. Drug safety newsletter. www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugSafetyNewsletter/ucm107318.pdf.

- 77.Frye MA, Ebbert JO, Prince CA, et al. A feasibility study of varenicline for smoking cessation in bipolar patients with subsyndromal depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2013;33:821-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weinberger AH, Vessicchio JC, Sacco KA, et al. A preliminary study of sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2008;28:584-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu BS, Weinberger AH, Mancuso E, et al. A preliminary feasibility study of varenicline for smoking cessation in bipolar disorder. J Dual Diagn 2012;8:131-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chengappa KN, Perkins KA, Brar JS, et al. Varenicline for smoking cessation in bipolar disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:765-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, et al. Smoking and major depression. A causal analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:36-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, et al. Cigarette smoking, major depression, and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;35:1602-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, et al. Major depression and stages of smoking. A longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martínez-Ortega JM, Goldstein BI, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, et al. Temporal sequencing of nicotine dependence and bipolar disorder in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Psychiatr Res 2013;47:858-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hartz SM, Lin P, Edenberg HJ, et al. Genetic association of bipolar disorder with the β(3) nicotinic receptor subunit gene. Psychiatr Genet 2011;21:77-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weinberger AH, George TP, McKee SA. Differences in smoking expectancies in smokers with and without a history of major depression. Addict Behav 2011;36:434-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]