Abstract

In many bacteria, iron homeostasis is controlled primarily by the ferric uptake regulator (Fur), a transcriptional repressor. However, some genes, including those involved in iron storage, are positively regulated by Fur. A Fur-repressed regulatory small RNA (sRNA), RyhB, has been identified in Escherichia coli, and it has been demonstrated that negative regulation of genes by this sRNA is responsible for the positive regulation of some genes by Fur. No RyhB sequence homologs were found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, despite the identification of genes positively regulated by its Fur homolog. A bioinformatics approach identified two tandem sRNAs in P. aeruginosa that were candidates for functional homologs of RyhB. These sRNAs (PrrF1 and PrrF2) are >95% identical to each other, and a functional Fur box precedes each. Their expression is induced under iron limitation. Deletion of both sRNAs is required to affect the iron-dependent regulation of an array of genes, including those involved in resistance to oxidative stress, iron storage, and intermediary metabolism. As in E. coli, induction of the PrrF sRNAs leads to the rapid loss of mRNAs for sodB (superoxide dismutase), sdh (succinate dehydrogenase), and a gene encoding a bacterioferritin. Thus, the PrrF sRNAs are the functional homologs of RyhB sRNA. At least one gene, bfrB, is positively regulated by Fur and Fe2+, even in the absence of the PrrF sRNAs. This work suggests that the role of sRNAs in bacterial iron homeostasis may be broad, and approaches similar to those described here may identify these sRNAs in other organisms.

While virtually all organisms require iron for survival, they also must manage the iron-catalyzed production of reactive oxygen intermediates that could lead to severe cellular damage (1). Consequently, they have evolved tightly regulated systems for both uptake and sequestration of this essential element. The ferric uptake regulator (Fur), a transcriptional repressor, is fundamental for maintaining iron homeostasis in many prokaryotes. Fur and its corepressor, Fe2+, inhibit the transcription of an array of genes that are crucial to iron-acquisition systems (e.g., siderophore synthesis and their uptake) by means of binding to a specific target sequence (Fur box) in their promoters.

Fur also acts as a positive regulator and affects the production of factors [e.g., superoxide dismutase (SodB) and bacterioferritins] that can mitigate iron toxicity under iron-replete conditions, as well as nonessential proteins that contain iron (e.g., aconitase, fumarase, and succinate dehydrogenase) (2, 3). The mechanism for this type of regulation is not as well understood as Fur-mediated repression. Massé and Gottesman (4) identified a Fur-regulated small RNA (sRNA), RyhB, which provides an explanation for the positive regulatory effects of Fur on gene expression in Escherichia coli and other enterobacteriae. RyhB RNA negatively regulates sodB, some tricarboxylic acid cycle genes, and genes encoding bacterioferritins by pairing with their mRNA and causing rapid degradation of the mRNA (5-7). Transcription of ryhB is in turn repressed by Fur. As a result, Fur-mediated inhibition of RyhB synthesis allows for the expression of certain genes (i.e., sodB) under iron-replete conditions but not under iron-limiting conditions. The nucleotide sequences of ryhB, its promoter (i.e., -35 and -10), and its operator (i.e., Fur box) are well conserved in E. coli, Salmonella, Klebsiella, Shigella, Photorhabdus luminescens (insect pathogen), and, to a lesser degree, Yersinia pestis.

In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Fur is an essential regulator that has many of the properties of its homologs in the above organisms (8). That is, Fur negatively regulates a large assortment of genes involved in iron acquisition, as well as those that contribute to virulence (9, 10). Ochsner et al. (11) recently reported that P. aeruginosa Fur also may act as a positive regulatory factor. Yet, no sequence homologous to ryhB could be identified in the annotated genome of P. aeruginosa PAO1.

In this report, we investigate whether sRNAs cause the positive regulation by Fur of certain genes in P. aeruginosa. We describe a bioinformatics approach that led to the identification of two functional homologs of RyhB [PrrF1 and PrrF2, for Pseudomonas regulatory RNA involving iron (Fe)] in this opportunistic pathogen. Notably, their nucleotide sequences are not similar to ryhB. The data suggest that PrrF1 and PrrF2 provide overlapping roles in the negative regulation of genes involved in diverse functions including iron storage, defense against oxidative stress, and intermediary metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Media, and Growth Conditions. P. aeruginosa PAO1 (www.pseudomonas.com, updated January 14, 2004) was the WT strain used in this study (12, 13). The PAO1 C6 mutant encodes Fur with an A10G mutation (14). Deletions were as follows: PAO1 ΔprrF1, base pairs 5283933-5284120 of PAO1 sequence; PAO1 ΔprrF2, base pairs 5284121-5284353; and PAO1 ΔprrF1-F2, base pairs 5283933-5284353. Two double mutants were made: ΔprrF1-F2, which does not have a gentamicin cassette in place of the deletion, and ΔprrF1-F2*, which does. Complementation of the ΔprrF1-F2 mutant was by transformation with pVLT31 containing prrF1-F2 sequence (base pairs 5283788-5284517). The complemented ΔprrF1-F2 strain is termed ΔF1-F2::F1-F2. Chelexed and dialyzed tryptic soy broth containing 1% glycerol and 50 mM glutamate was used as the low-iron medium and supplemented with 50 μg/ml FeCl3 to serve as the high-iron medium (15).

For experiments to examine the kinetics of sRNA action, cultures were diluted in fresh LB to OD600 = 0.02 and grown at 37°C to OD600 = 0.80. The iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl was added to a final concentration of 300 μM. Samples were stabilized and collected by using RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent and the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Deletion/insertion mutations in PAO1 were constructed as described in refs. 16 and 17. Genetic manipulations were verified by using PCR. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: for E. coli, 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 15 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 μg/ml kanamycin, and 15 μg/ml tetracycline; for P. aeruginosa, 750 μg/ml carbenicillin, 75 μg/ml gentamicin, and 150 μg/ml tetracycline.

Identification of the sRNAs. The P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome (GenBank accession no. NC_002516) was partitioned into two data sets, one that included all known (annotated) ORFs and a second that comprised the intergenic (IG) regions defined by the annotated ORFs. The IG data set was queried, by using the program patscan (18), for the presence of sequences that included a consensus Fur box, a spacer of 0-200 bases, and a potential stem-loop structure immediately followed by a series of at least three T nucleotides (U nucleotides in RNA). The Fur-box query required an identity match of at least 14 bases of the 19-base consensus sequence, GATAATGATAATCATTATC. The stem-loop parameters were set to require a stem of 7-12 complementary bases with a loop of 5-9 bases.

Translational Fusions to the lacZ Reporter Gene and β-Galactosidase Assays. PCR products containing regions upstream and within the coding region of pvdS, bfrB, and PA4880 were cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) and sequenced. Translational fusions to LacZ were made by cloning the DNA products into pPZ20 or pPZ30 (19). P. aeruginosa PAO1 and deletion strains were transformed with the resulting plasmids and grown at 32°C for 12 h in low-iron medium (see above). β-Galactosidase activities in soluble cell extracts were determined by using ONPG (Sigma) as the substrate and expressed as units per milligram, as described in ref. 20.

Gel Mobility-Shift Assays. The DNA fragments were end-labeled with [32P]dATP and gel-purified. Various amounts (0-200 nM) of purified Fur were added to 0.1 ng of DNA in binding buffer [10 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.5/40 mM KCl/0.1 mM MnSO4/1 mM MgSO4/100 μg/ml BSA/50 μg/ml poly(dI-dC)/10% glycerol] and incubated at room temperature. After 30 min, the reaction was resolved in acrylamide, and the results were viewed by using a phosphorimager.

RNA Isolation, RNase Protection, Northern Blot, and GeneChip Analysis. Total RNA was isolated by using the hot phenol method, followed by DNase I treatment (14), and RNA integrity was confirmed by RNase protection analysis with a riboprobe specific for the constitutively expressed omlA gene (21). Quantification of the image generated by a Bio-Rad phosphorimager was performed with quantity one software (Version 4.5, Bio-Rad), and expression of PA4880 was normalized to omlA expression. Probes for Northern analysis in Fig. 3 were as follows: PrrF1, GAGTCCGACTGCGTGGGTCTCTCAGCTTACCGGCTG; PrrF2, GAGTCCGACTGCTTGGTCTCTCAGCTTACCTGCTGGCCT.

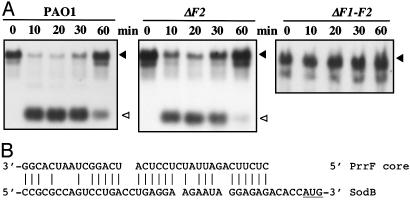

Fig. 3.

Regulation of sodB by PrrF sRNAs. (A) PAO1, ΔprrF2 (ΔF2), and ΔprrF1-F2 (ΔF1-F2) were grown in LB and 2,2′-dipyridyl added to a final concentration of 300 μM; samples were taken at the times indicated and probed for sodB transcripts as described in Materials and Methods. ▴, sodB transcript; ▵, PrrF. (B) A possible pairing of the PrrF core sequence to the sodB ribosome-binding site is shown. The starting AUG is underlined.

For the Northern blots, 8 μg of RNA was resolved in acrylamide or agarose. The RNA was transferred to membrane, cross-linked, and prehybridized for 1 h at 42°C in ULTRAhyb hybridization solution (Ambion, Austin, TX). Probes were added to a final concentration of 200 ng/ml and hybridized overnight at 42°C. Blots were washed, and the nonisotopic probes were visualized by using the BrightStar Biodetect Kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Probes were as follows: PrrFs, AAACCGTGATTAGCCTGATGAGGAGATAATCTGAA; SodB, TTCGGGCTCAGGCAGTTCCAGTAGAAGGTGTGGTT; and BfrB, TTCAGGTCGCACTGCAGCATTTCCTGGGTGTTCTC.

The GeneChip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) probes were prepared according to manufacturer's protocol with the modifications described in ref. 11. Analysis of microarray data was performed with microarray suite (Version 5.0, Affymetrix).

Results

Identification of Potential Fur-Regulated sRNAs in P. aeruginosa. Massé and Gottesman (4) demonstrated that the expression of a Fur-regulated sRNA (RyhB) is responsible for the regulation of various genes in E. coli that are expressed under iron-replete conditions. Sequences homologous to these sRNAs were also identified in other Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Y. pestis). However, this homology did not extend to the genus Pseudomonas. Because the vast majority of sRNAs that have been described in E. coli are encoded in IG regions, one approach to searching for functional homologs to RyhB in Pseudomonas would have been to assay for expression of a transcript within the IG regions under iron-limiting conditions by using microarrays. However, this procedure requires the presence of microarray probes for all of the IG regions, which are not available for P. aeruginosa; only 199 IG regions are present on the available microarray. Instead, we used a bioinformatics approach to look for functional homologs by searching all of the IG regions of P. aeruginosa PAO1 for two predicted properties of such a homolog: regulation by Fur and a ρ-independent terminator, found in many E. coli sRNAs (22, 23). The IG regions of the P. aeruginosa genome were queried for sequences that included a consensus Fur box (with an identity match of at least 14 bases of the 19-base consensus sequence, GATAATGATAATCATTATC), a spacer of 0-200 bases, and a potential stem loop structure (7-12 complementary bases with a loop of 5-9 bases), immediately followed by a series of at least three T nucleotides (U nucleotides in RNA). This analysis yielded only three candidates from the IG data set. One potential sRNA was located between PA1321 and PA1322, and two candidates were located in tandem between PA4704 and phuW (PA4705) (Fig. 1A). By Northern blotting, no transcript was detected from the PA1321/2 IG region (data not shown). However, iron-regulated transcripts from the IG region between PA4704 and phuW had been previously detected (24). In that study, these transcripts' functions were not identified, and they had no detectable effect on the expression of the flanking genes, PA4704 and phuW. Herein, the transcript proximal to PA4704 is termed PrrF1 and the one proximal to phuW, PrrF2. Remarkably, PrrF1 and PrrF2 are >95% identical (Fig. 1B). As required by the algorithm, we identified a consensus Fur box preceding each transcript. Gel mobility-shift assays (Fig. 1C) indicated that Fur bound each Fur box at a biologically relevant concentration of Fur.

Fig. 1.

Genetic organization of Prrf sRNAs. (A) Genetic organization of the locus encoding prrF1 and prrF2 showing the Fur-binding sites. The arrow indicates gene orientation. (B) Alignment of the prrF1 and prrF2 including promoters. The Fur-binding site is in blue. Sequence conserved in all Pseudomonas PrrF sequences identified thus far is in green. The predicted -35 and -10 regions are indicated in yellow and pink, respectively. (C) Gel mobility-shift assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Consensus binding sites for Fur are shown in black, and the Fur box present in the PrrF sequence is shown in blue.

PrrF Homologs in Other Organisms. Various clinical and environmental isolates of P. aeruginosa (n = 49) were examined for sequences similar to prrF. Related sequences were detected in all strains examined, and identically sized PCR products were amplified by using primers within the flanking genes (data not shown). These data indicate that prrF1 and prrF2 are likely to be in the same location in all P. aeruginosa strains examined and that they all contain tandem copies of these genetic elements. Because blast searches revealed that sequences homologous to ryhB are only found in a relatively narrow range of organisms (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae), we asked whether prrF sequence homologs are present in other bacteria. A blast search of completed genomes in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database revealed that sequences closely related to prrF are only found in Pseudomonas spp. Moreover, although two putative prrF sequence homologs were found in Pseudomonas putida, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Pseudomonas syringae, they are considerably distal to each other in these organisms in contrast with their tandem location in P. aeruginosa. However, all copies are preceded by a promoter sequence and conserved Fur box and have a core of identical sequence (shown in green in Fig. 1B for the P. aeruginosa sRNAs).

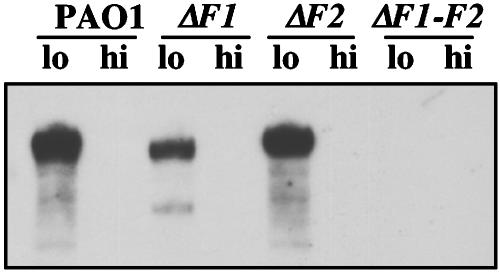

Expression of PrrF1 and PrrF2. PrrF1 and PrrF2 differ by five nucleotides, and a functional Fur-binding site precedes each (Fig. 1 B and C). The iron-regulated expression of these transcripts was confirmed by evaluating their relative levels in iron-replete and -deficient cells. Transcripts of ≈110 nt (Fig. 2) were detected in WT cells cultured in iron-limiting conditions but not in cells cultured under iron-replete conditions. Deletions in prrF1, prrF2, or both were constructed. These mutants were used to further examine the regulation and function of these sRNAs. Detectable transcripts were still produced from growth of ΔprrF1 or ΔprrF2 in low iron, but not in high iron (Fig. 2). The PrrF2 transcript (present in ΔF1) consistently migrated faster than PrrF1 (present in ΔF2), thereby suggesting that PrrF1 is a slightly longer transcript, a conclusion that is consistent with other data (24). No PrrF-related transcripts were detected in ΔprrF1-F2 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Northern blotting of PAO1 ΔprrF1 (ΔF1), ΔprrF2 (ΔF2), and ΔprrF1-F2 (ΔF1-F2). Cells were grown overnight in dialyzed tryptic soy broth in the presence or absence of added FeCl3 (50 μg/ml). RNA was isolated and probed for PrrF1-F2 sequences. Probe sequences are given in Materials and Methods.

PrrF-Regulated Genes in P. aeruginosa. Previously, by using DNA microarray technologies, an assortment of P. aeruginosa genes were identified that are responsive to either iron-limiting or -replete conditions (11). Table 1 lists a subset of the genes found to be positively affected by iron (PAO1 high Fe vs. low Fe). Genes expressed at higher levels under iron-replete conditions than under iron-limiting conditions included bfrB (see below), a gene encoding a probable bacterioferritin (PA4880), sodB, and sdh (encoding succinate dehydrogenase) (Table 1), similar to the set of genes regulated by RyhB in E. coli. In addition, some genes indicated strong regulation in the arrays. For example, expression of the probable transcriptional regulator PA2511 is increased 46-fold when cultured in iron-replete conditions, as compared with when it is cultured in iron-limiting conditions; the adjacent and divergently transcribed genes (PA2512-PA2514) are similarly regulated.

Table 1. GeneChip analyses comparing PAO1 and ΔprrF mutants.

| ORF/operon | Gene | Function | Fold change* PAO1 hi Fe vs. lo Fe | Fold change* ΔF1 vs. PAO1 lo Fe | Fold change* ΔF2 vs. PAO1 lo Fe | Fold change*† ΔF1-F2 vs. PAO1 lo Fe | Fold change* ΔF1-F2::F1-F2 vs. PAO1 lo Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA2512 | antA | Anthranilate dioxygenage, large subunit | 215 | NC | NC | 512 (675) | NC |

| PA2513 | antB | Anthranilate dioxygenase, small subunit | 250 | 1.8 | NC | 137 (90) | NC |

| PA2514 | antC | Anthranilate dioxygenase reductase | 95 | NC | NC | 55 (48) | NC |

| PA2511 | HUU | Probable transcriptional regulator | 46 | NC | NC | 103 (34) | NC |

| PA2682 | HUU | Dienelactone hydrolase | 74 | 1.3 | NC | 29 (21) | NC |

| PA4811 | fdnH | Nitrate inducible formate dehydregenase, b subunit | 12 | 1.3 | NC | 181 (9.1) | NC |

| PA4880 | HUU | Probable bacterioferritin | 5.0 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 14 (16) | NC |

| PA4236 | katA | Catalase | 3.7 | NC | 1.6 | 5.6 (2.0) | NC |

| PA1174 | napA | Periplasmic nitrate reductase | 8.8 | NC | NC | 12.9 (2.3) | NC |

| PA4366 | sodB | Superoxide dismutase | 3.2 | NC | NC | 4.6 (1.8) | NC |

| PA1582 | sdhD | Succinate dehydrogenase, D subunit | 7.1 | NC | NC | 3.2 (1.7) | NC |

| PA1583 | sdhA | Succinate dehydrogenase, A subunit | 3.1 | NC | NC | 3.7 (1.6) | NC |

| PA1584 | sdhB | Succinate dehydrogenase, B subunit | 2.9 | NC | NC | 4.0 (1.6) | NC |

| PA1581 | sdhC | Succinate dehydrogenase, C subunit | 6.0 | NC | NC | NC (NC) | NC |

| PA3531 | bfrB | Bacterioferritin B | 82 | 1.6 | NC | 3.0 (−2.8) | NC |

NC, no change; hi, high; lo, low.

P values for all fold change values except NC were <0.00005.

Number in parentheses reflects the fold change in an independent mutant in which the interrupting antibiotic cassette remains intact.

The contributions of prrF1 and prrF2 individually and collectively were determined by comparing global expression in prrF mutants and the PAO1 parental WT. Cells carrying the single and double mutants were grown under iron-limiting conditions, and the level of expression in the microarrays was compared with the level of expression for WT under the same growth conditions. Data in Table 1 indicate that the prrF1 and prrF2 sequences encode sRNAs with overlapping function because only minimal or no change was detected in the expression of the genes listed when either prrF1 or prrF2 alone was deleted (Table 1, ΔF1 vs. PAO1 and ΔF2 vs. PAO1). When both prrF1 and prrF2 sequences were deleted, expression of some, but not all, of the genes in Table 1 was substantially increased under iron-limiting conditions (Table 1, ΔF1-F2 vs. PAO1), consistent with the loss of iron regulation. In another experiment, the level of expression of the ΔprrF1-F2 mutant in iron-replete and iron-limiting media was compared in microarrays (data not shown). For nearly all of the genes listed in Table 1, the transcript levels were not as highly regulated by iron in the ΔprrF1-F2 mutant as they are in WT PAO1, as expected if the PrrF RNAs are necessary for this regulation. Introduction of a plasmid carrying prrF1-F2 sequences restored expression of all of the genes affected in the ΔprrF1-F2 mutant to the level detected in the WT strain (Table 1).

One exception to this pattern is bfrB. Either in a comparison between the ΔprrF1-F2 mutant and WT (Table 1) or in a comparison of expression in iron-replete and iron-limiting media in the ΔprrF1-F2 mutant (data not shown), bfrB regulation is not perturbed by the deletion of the PrrF sRNAs (see below).

These observations from microarray experiments were confirmed and examined further for two specific targets. SodB mRNA, which is positively regulated by Fur and iron (Table 1), rapidly disappeared after iron chelation in PAO1 (Fig. 3A). A single mutant deleted for PrrF2 (Fig. 3A) or PrrF1 (data not shown) still had iron-regulated expression of sodB, although it was not as stringent as when both PrrF RNAs were present. An examination of the possible pairing of sodB and PrrF indicated a reasonable region of complementarity just before the start of the coding region (Fig. 3B). In experiments done with a probe for sdh, similar effects were observed (data not shown). These results confirm the finding from the microarrays that PrrF1 and PrrF2 both contribute to the regulation of target mRNAs.

The cultures examined by microarrays were grown under different conditions than those used for the Northern blots in Fig. 3. In the Northern blots, cells were grown in LB broth and chelator was added, then samples were taken in the hour immediately after addition of chelator. Cells growing under these conditions lose induction of the PrrF RNAs after 1 h (i.e., the target messages reaccumulate at that time), possibly as a consequence of the limited chelating ability of the 2,2′-dipyridyl. Chelation could be reversed by induction of the Fur-repressed siderophores (e.g., pyoverdine) of P. aeruginosa and removal of iron from 2,2′-dipyridyl and/or by the iron-sparing effect of expressing the PrrF sRNAs and therefore shutting down synthesis of other iron-binding proteins.

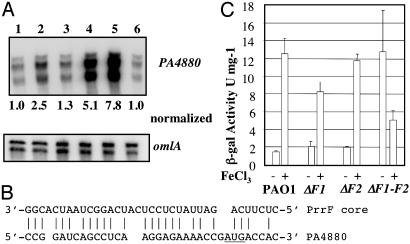

For the microarray experiments, cells were grown to the stationary phase in iron-limiting or iron-replete conditions as described in ref. 11. The regulatory effects of the PrrF sRNAs on expression of a specific gene, PA4880, were examined in more detail under the growth conditions used in the microarray experiments. PA4880 encodes a protein with homology to bacterioferritins. As shown in Fig. 4A, when both prrF1 and prrF2 are deleted (lane 4), the level of PA4880 transcript under iron-limiting conditions is ≈5-fold higher than when either one or both PrrF1-F2 transcripts are present (lanes 1-3). A constitutively expressed gene (omlA) served as a control for total RNA loading. Complementation of ΔprrF1-F2 with a plasmid carrying prrF1-F2 sequences (lane 6) resulted in transcript levels of PA4880 similar to those of WT (lane 1). When the vector alone (lane 5) was used, the relative level of PA4880 transcript remained as it was in the ΔprrF1-F2 mutant. A possible complementarity between PA4880 and PrrF is shown in Fig. 4B. The pattern of regulation we observed from RNase protection assays and from DNA microarray data for PA4880 in WT and the ΔprrF1-F2 mutants also was seen from a PA4880::LacZ translational fusion, even when only the region between the promoter and the ATG was included in the fusions (Fig. 4C). The reason for the decreased levels of β-galactosidase observed in the ΔprrF1-F2 mutant grown in high iron (300 μM) as compared with either the WT or single mutants (Fig. 4C) is unclear at this time, but it may be caused by an increased susceptibility of the double mutant to the toxic effects of iron. Such an effect of this iron concentration was not seen with the PAO1 parental WT or with the single mutants. Moreover, when lower concentrations of iron (i.e., 100 μM) were used, the decreased levels of β-galactosidase observed in the ΔprrF1-F2 double mutant grown in high iron relative to the WT were not observed. The microarray data (Table 1), the RNase protection assays and the translational fusion data with PA4880 confirm that this gene encoding a probable bacterioferritin is regulated by these sRNAs.

Fig. 4.

Regulation of PA4880 by Prrf sRNAs. (A) RNase protection assay. PAO1 was grown in dialyzed tryptic soy broth without added FeCl3. PA4880 transcript levels were measured in RNA from PAO1 (lane 1), ΔprrF1 (lane 2), ΔprrF2 (lane 3), ΔprrF1-F2 (lane 4), ΔprrF1-F2, pVLT (lane 5), and ΔprrF1-F2, pVLT-prrF1-F2 (lane 6). Additionally, the presence of transcripts from omlA, a constitutively expressed gene, was analyzed to verify the integrity of the RNA sample. Numbers given as normalized values are from comparison with omlA. (B) Possible complementarity between core sequence of PrrF RNAs and the ribosome-binding-site region of PA4880. (C) β-galactosidase assays in strains containing pPZ-PA4880. PAO1, ΔprrF1 (ΔF1), ΔprrF2 (ΔF2), and ΔprrF1-F2 (ΔF1-F2) strains were grown in 0 and 300 μM FeCl3 and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity. The data represent the mean ± SE of three different experiments.

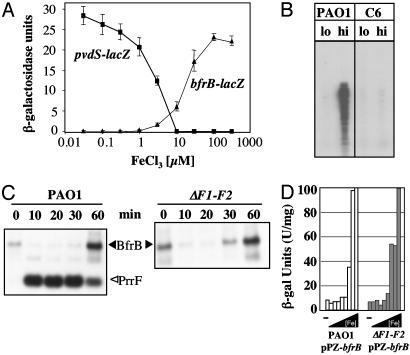

PrrF-Independent Regulation of bfrB Encoding Bacterioferritin. Fig. 5A illustrates the typical negative regulatory effect of Fe2+ on the transcription of genes (i.e., pvdS) involved in iron-acquisition systems. In contrast, characterization of a gene encoding bacterioferritin (bfrB), a subunit of the major iron-storage protein in bacteria, revealed that its regulation is characteristic for those positively regulated by Fur (Fig. 5A). Moreover, this positive regulation depends on a functional Fur (Fig. 5B). Although Fur is essential in P. aeruginosa, a missense mutant (A10G) has been shown to be defective in its ability to specifically bind to its operator (14). This increased expression under iron-replete conditions was confirmed with Northern blots in which the bfrB transcript level was measured in PAO1 after addition of chelator (Fig. 5C). Thus, bfrB is another example of a gene positively regulated by Fur and iron.

Fig. 5.

Regulation of bfrB. (A) P. aeruginosa PAO1 expressing pvdS-lacZ or bfrB-lacZ was cultured for 12 h in dialyzed tryptic soy broth supplemented with various concentrations (0-300 μM) of iron. Protein extracts were collected, and β-galactosidase activity was measured. (B) RNase protection assay. PAO1 and the C6 fur- mutant were grown in iron-limiting and iron-replete media. RNA was isolated and probed with a bfrB-specific probe. (C) Northern blot for BfrB and PrrF RNA isolated from PAO1 and ΔF1-F2 after addition of 2,2′-dipyridyl as for Fig. 3. (D) P. aeruginosa PAO1 (white) and ΔF1-F2 (gray) containing pPZ-bfrB (BfrB::LacZ translational fusion) were grown in various concentrations of iron (0-300 μM) and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity.

However, unlike sodB and PA4880, iron regulation of bfrB does not depend on PrrF1 and PrrF2. In Table 1, neither the single nor double prrF mutants change the expression of bfrB at low iron, compared with WT cells. This observation was confirmed by two other approaches. In a Northern blot in the double-deletion mutant, addition of chelator still leads to loss of bfrB message within 10 min (Fig. 5C) (compare with behavior of sodB transcripts in Fig. 3B). The expression of bfrB also was examined under conditions similar to those used for the microarray experiments of reporter constructs with bfrB fused to lacZ. LacZ activity in the ΔprrF1-F2 mutant was still regulated by iron, as it is in the WT PAO1 (Fig. 5D). No β-galactosidase activity was detected when the strains were transformed with the vector alone (data not shown). Therefore, PrrF1 and PrrF2 are not sufficient to explain all positive regulation by Fur and iron in P. aeruginosa.

Discussion

Studies during the last few years have demonstrated that the IG regions in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, formerly classified as “spacer” or “junk” DNA, frequently harbor sRNAs that play remarkable roles in critical cellular processes [e.g., oncogenesis (25), apoptosis (26), and iron homeostasis (4, 6)]. A large class of these sRNAs act by complementary base-pairing with a target mRNA, leading to a change in the target structure that can positively or negatively affect translation of the target (27, 28).

One of the challenges in understanding the contribution of sRNAs to regulation has been finding them. Comparative sequence analysis alone is not sufficient, and mutations have not been detected in these bacterial sRNAs (reviewed in refs. 27-29), possibly because of the small target size. Various computational and experimental methods have been developed (30-36) and tested in E. coli. Many of the 50 sRNAs now known in E. coli are conserved in near neighbors (Salmonella, Klebsiella, and Yersinia), but very few can be found by sequence comparisons in more distant organisms. In this study, we use the characteristics of one of these E. coli sRNAs to develop a strategy for seeking functional homologs. Two such homologs were found in P. aeruginosa, and the approach should be easily applicable to other organisms and other sRNAs.

Massé and Gottesman (4) identified a role for one well conserved E. coli sRNA, RyhB, in iron metabolism and potentially in defense against oxidative stress. RyhB is repressed by the Fur repressor under iron-replete conditions. Under iron-starvation conditions, RyhB is made and negatively regulates the expression of genes encoding iron-binding proteins (e.g., sdh, sodB, and bfrB) at the posttranscriptional level. This mechanism provided an explanation for the puzzling observation that Fur positively regulates the expression of these genes by repressing the expression of another repressor.

Many studies suggested that pseudomonads also positively regulate some of their iron-binding proteins. Ochsner et al. (11) examined global gene regulation by iron in P. aeruginosa. Although many iron-starvation-induced genes were identified in this study, there were also a significant number of genes specifically induced under iron-replete conditions, including those involved in iron storage, oxidative stress defenses, and intermediary metabolism. P. putida was found to down-regulate sodB transcripts and protein under iron-deficient conditions (37, 38). These data suggested parallels between this regulatory process in P. aeruginosa and P. putida and the positive regulation of gene expression in E. coli and other organisms by Fur via RyhB as described above. Although no RyhB sequence homologs could be detected in the P. aeruginosa genome, we proposed that some of the structural features of RyhB might be conserved and could thereby be identified by a computer algorithm. Thus, we asked whether equivalent sRNAs could be found in Pseudomonas by using three characteristics, two of them common to many sRNAs and the third specific to RyhB. Those characteristics are as follows: (i) RyhB and other sRNAs are present in IG regions; (ii) RyhB and many other sRNAs end with a ρ-independent terminator, a stem-loop followed by a run of T nucleotides; and (iii) RyhB is regulated directly by the Fur repressor. This approach led to the identification of two tandem RyhB-like sRNAs we termed PrrF1 and PrrF2. We demonstrated that both are Furand iron-regulated and are functional homologs of RyhB. This approach can easily be extended to look for sRNAs regulated by any well defined regulatory protein in any sequenced organism that is known to use ρ-independent terminators.

In P. aeruginosa, the PrrF sRNAs are duplicated and tandemly located. In P. putida, P. fluorescens, and P. syringae, two copies are also present, but only one copy is in a context with some similarity to that of P. aeruginosa; the second copy is distal in location in the genome. Intriguingly, duplicated versions of RyhB and its regulatory sequences also have been detected in the genomes of Salmonella and Y. pestis (4). In these organisms, the second copies are not tandemly located. This finding suggests that bacteria frequently have use for two copies of RyhB/PrrF. The basis for the requirement for two copies of PrrF is not clear. Both participate in the functions we have reported here; only deletion of both relieves the positive regulation by Fur and iron (Figs. 3 and 4 and Table 1). However, it seems likely that the two sRNAs are under somewhat different regulation and also may have different preferential targets. Ochsner et al. (24) showed differential regulation by heme of prrF1, but not by prrF2. This finding may reflect a differential sensitivity to low iron levels. We know of one other case of tandem sRNAs, the rygA and rygB RNAs in E. coli. These sRNAs are clearly under somewhat different regulation, although the RNAs themselves are highly conserved (32, 34).

Many organisms respond to iron deprivation by rearranging their metabolism to bypass iron-dependent enzymes, such as sodB and tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes, and to dispense with iron-binding proteins, such as ferritins. Our study extends the role of sRNAs in mediating this change in metabolism from E. coli and its relatives to the pseudomonads. Our findings also demonstrate that the PrrF RNAs do not explain all positive regulation by Fur and iron in P. aeruginosa; bfrB regulation was not affected by mutations in either or both PrrF sRNAs (Fig. 5). Therefore, at least one other mechanism of Fur-mediated positive regulation must exist in this organism. One possibility would be a third, undetected PrrF RNA. A second possibility would be direct regulation by Fur, as is seen in Neisseria (39). A third possibility would be a regulatory protein, rather than a regulatory RNA, repressed by Fur and itself capable of repressing bfrB. We have previously identified such a candidate, PA4570, during a global GeneChip analysis of iron-regulated genes (11). PA4570 expression showed an ≈403-fold expression increase by iron and possessed a strong Fur-box in its promoter region. Although the protein encoded by PA4570 is of unknown function, we noticed a weak similarity to the IclR repressor family. Expression studies with PA4570 mutants and strains hyperexpressing PA4570 may clarify whether PA4570 plays a mediatory role in positive regulation of bfrB by Fur.

In other organisms, positive regulation by Fur has not been investigated sufficiently to identify the mechanism of regulation. Certainly, our findings suggest that sRNAs carry out this important function in various prokaryotic organisms and should be considered potential candidates for positive regulation by Fur in other organisms.

The PrrF sRNAs are previously unrecognized examples in Pseudomonas of a major class of sRNAs that may act by complementary base-pairing. In E. coli, this class of small RNAs uses an RNA chaperone, Hfq (40). P. aeruginosa also carries Hfq, which has been shown to be functional in E. coli (41). Therefore, we would predict that the PrrF sRNAs also will use Hfq and that the many other Hfq-using sRNAs found in E. coli also will have orthologs in Pseudomonas. Another class of regulatory RNAs has previously been described in P. fluorescens; RsmY and RsmZ bind to and inhibit the activity of a translational regulatory protein, RsmA (42, 43); this target protein and these sRNAs are similar to the CsrA protein in E. coli and its two inhibitory RNAs, CsrB and CsrC. Thus, pseudomonads are likely to have all of the major classes of sRNAs defined in E. coli.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratories, Gisela Storz, and Peter Greenberg for their comments on the manuscript and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics for subsidizing the Affymetrix Gene-Chips. This work was supported by National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant AI15940 (to M.L.V.).

Abbreviations: Fur, ferric uptake regulator; IG, intergenic; SodB, superoxide dismutase; sRNA, small RNA.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. NC_002516, BK005485, and BK005486).

References

- 1.Touati, D. (2000) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 373, 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubrac, S. & Touati, D. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 3802-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niederhoffer, E. C., Naranjo, C. M., Bradley, K. L. & Fee, J. A. (1990) J. Bacteriol. 172, 1930-1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massé, E. & Gottesman, S. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 4620-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massé, E., Escorcia, F. E. & Gottesman, S. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 2374-2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geissmann, T. A. & Touati, D. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 396-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vecerek, B., Moll, I., Afonyushkin, T., Kaberdin, V. & Blasi, U. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 50, 897-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pohl, E., Haller, J. C., Mijovilovich, A., Meyer-Klaucke, W., Garman, E. & Vasil, M. L. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 47, 903-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ochsner, U. A. & Vasil, M. L. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 4409-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasil, M. L. & Ochsner, U. A. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 34, 399-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochsner, U. A., Wilderman, P. J., Vasil, A. I. & Vasil, M. L. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1277-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holloway, B. W., Krishnapillai, V. & Morgan, A. F. (1979) Microbiol. Rev. 43, 73-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stover, C. K., Pham, X. Q., Erwin, A. L., Mizoguchi, S. D., Warrener, P., Hickey, M. J., Brinkman, F. S., Hufnagle, W. O., Kowalik, D. J., Lagrou, M., et al. (2000) Nature 406, 959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton, H. A., Johnson, Z., Cox, C. D., Vasil, A. I. & Vasil, M. L. (1996) Mol. Microbiol. 21, 1001-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prince, R. W., Cox, C. D. & Vasil, M. L. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 2589-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoang, T. T., Karkhoff-Schweizer, R. R., Kutchma, A. J. & Schweizer, H. P. (1998) Gene 212, 77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schweizer, H. P. & Hoang, T. T. (1995) Gene 158, 15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dsouza, M., Larsen, N. & Overbeek, R. (1997) Trends Genet. 13, 497-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schweizer, H. P. (1991) Gene 103, 87-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochsner, U. A., Vasil, M. L., Alsabbagh, E., Parvatiyar, K. & Hassett, D. J. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 4533-4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochsner, U. A., Vasil, A. I., Johnson, Z. & Vasil, M. L. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 1099-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wassarman, K. M., Repoila, F., Rosenow, C., Storz, G. & Gottesman, S. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 1637-1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hershberg, R., Altuvia, S. & Margalit, H. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 1813-1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ochsner, U. A., Johnson, Z. & Vasil, M. L. (2000) Microbiology 146, 185-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez, L. A., Naguibneva, I., Lehrmann, H., Vervisch, A., Tchenio, T., Lozano, G. & Harel-Bellan, A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14849-14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zender, L., Hutker, S., Liedtke, C., Tillmann, H. L., Zender, S., Mundt, B., Waltemathe, M., Gosling, T., Flemming, P., Malek, N. P., et al. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 7797-7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gottesman, S. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2829-2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masse, E., Majdalani, N. & Gottesman, S. (2003) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gottesman, S. (2004) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Eddy, S. R. (2001) Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 919-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eddy, S. R. (2002) Cell 109, 137-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wassarman, K. M., Zhang, A. & Storz, G. (1999) Trends Microbiol. 7, 37-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen, S., Lesnik, E. A., Hall, T. A., Sampath, R., Griffey, R. H., Ecker, D. J. & Blyn, L. B. (2002) Biosystems 65, 157-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, A., Wassarman, K. M., Rosenow, C., Tjaden, B. C., Storz, G. & Gottesman, S. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 50, 1111-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rivas, E. & Eddy, S. R. (2001) BMC Bioinformatics 2, 8. Available at www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/2/8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Argaman, L., Hershberg, R., Vogel, J., Bejerano, G., Wagner, E. G., Margalit, H. & Altuvia, S. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 941-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heim, S., Ferrer, M., Heuer, H., Regenhardt, D., Nimtz, M. & Timmis, K. N. (2003) Environ. Microbiol. 5, 1257-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim, Y. C., Miller, C. D. & Anderson, A. J. (1999) Gene 239, 129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delany, I., Rappuoli, R. & Scarlato, V. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 52, 1081-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valentin-Hansen, P., Eriksen, M. & Udesen, C. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 51, 1525-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonnleitner, E., Moll, I. & Blasi, U. (2002) Microbiology 148, 883-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heeb, S., Blumer, C. & Haas, D. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 184, 1046-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valverde, C., Heeb, S., Keel, C. & Haas, D. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 50, 1361-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]