Abstract

Objective

Previous research has shown relatively high use of out-of-network mental health providers, although direct comparisons with rates among general health providers are not available. We aimed to (1) estimate the proportion of privately insured adults using an out-of-network mental health provider in the past 12 months; (2) compare rates of out-of-network mental health provider use with out-of-network general medical use; (3) determine reasons for out-of-network mental health care use.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of privately insured US adults was surveyed using the internet in February 2011. Screener questions identified if the participant had used either a general medical physician or a mental health professional within the past 12 months. Respondents using either type of out-of-network provider completed a 10-minute survey on details of their out-of-network care experiences.

Results

Eighteen percent of individuals who used a mental health provider reported at least 1 contact with an out-of-network mental health provider, compared to 6.8% who used a general health provider (P < 0.01). The most common reasons for choosing an out-of-network mental health provider were the physician was recommended (26.1%), continuity with a previously known provider (23.7%), and the perceived skill of the provider (19.3%).

Conclusions

Out-of-network provider use is more likely in mental health care than general health care. Most respondents chose an out-of-network mental health provider based on perceived provider quality or continuing care with a previously known provider rather than issues related to the availability of an in-network provider, convenient location, or appointment wait time.

Keywords: mental health care, out-of-network care, managed care

Health insurance plans offering out-of-network mental health coverage contract with a group of “preferred” or “in-network” providers who agree to accept a negotiated fee schedule. Patients can use out-of-network mental health providers but at higher out-of-pocket cost sharing. Use of an out-of-network provider is intended to be a deliberate choice, yet several recent news reports cite anecdotal evidence that out-of-network mental health care use is often involuntary and thus identify high out-of-network mental health care use as problematic.1,2 However, there is little empirical data available on why individuals use out-of-network mental health care.

Out-of-network mental health care was addressed in part with the passage of the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. In addition to requiring equivalent out-of-network cost-sharing (including copayment, coinsurance, or deductibles) for behavioral health and for medical/surgical services, plans must also have parity with respect to nonquantitative treatment limitations, which include standards for provider admission to participate in a network and plan methods for determining usual, customary, and reasonable charges.

Understanding the reasons for out-of-network mental health care use is critical to determine whether additional policy intervention is necessary and, if so, to identify adequate policy solutions. Out-of-network use may be higher for mental health services compared to general health services for several reasons. From a provider’s perspective, provider shortages may give mental health providers the market power to opt not to participate in networks. In a survey of physicians, approximately 35% of psychiatrists did not contract with managed care organizations, compared to rates of 8%–12% for other specialties.3 Mental health providers cite low reimbursement levels and unacceptable limits on care receipt as reasons for lack of network participation.3-5 From a patient perspective, continuity of care may be more valued for mental health treatment compared to general medical treatments, particularly for patients being treated with psychotherapy. Patients may be willing to pay more out-of-pocket to complete treatment with a trusted provider who may no longer have in-network status. Finally, from an insurer’s perspective, mental health disorders are often chronic and individuals with these disorders tend to have particularly high health care costs, suggesting that insurers may benefit from not enrolling such individuals.6,7 Restrictive mental health provider networks may be one mechanism to dissuade these individuals from choosing a plan.

Previous research has shown high rates of out-of-network use of mental health providers, although to our knowledge no studies have made direct comparisons with rates among general health providers. For example, Stein et al8 found that 15.4% of individuals using outpatient mental health service care used some out-of-network care. Another study examined rates of out-of-network mental health care use in the Washington, DC, area after implementation of the Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) parity initiative and found that only 43% of the FEHB-insured caseload was treated by an in-network provider during the sampled visit.5 Given the lack of recent information on national rates of out-of-network mental health care use, we sought to (1) estimate the proportion of privately insured adults using an out-of-network mental health provider in the past 12 months; (2) compare rates of out-of-network mental health provider use with general medical out-of-network use; and (3) determine reasons for out-of-network mental health care use. We specifically examine whether individuals reported reasons related to network size and composition or provider quality.

DATA AND METHODS

A nationally representative sample of privately insured US adults was surveyed using the internet in February 2011 on details of their out-of-network care experiences. Survey methods have been described in depth elsewhere.9 Briefly, a novel survey (see Supplemental Appendix A, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/A501) was constructed, and cognitive interviews using established methods10 were performed to assess relevance of content, as well as language and structure of items. The survey was administered via the internet by Knowledge Networks, with an online research panel (KnowledgePanel) consisting of approximately 50,000 US households sampled by random-digit-dialing and address-based sampling.11 The probability-based sampling used to construct the panel and its representativeness of the US population have been validated.12 Poststratification weights were applied to match the sample to the US population based on Current Population Survey data on sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, metropolitan area, census region, and internet access, and to adjust for survey nonresponse and oversampling.

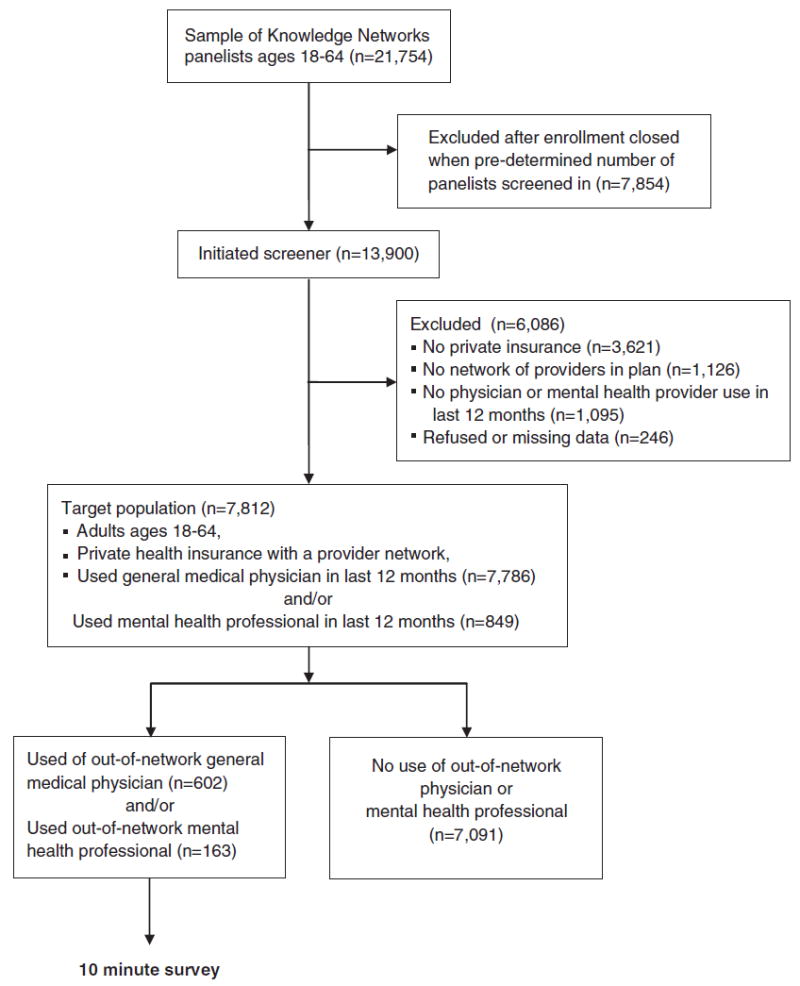

Screener questions were sent to 21,754 English-speaking panelists aged 18–64. These screener questions identified respondents enrolled in a private health insurance plan with a provider network who had seen a physician and/or mental health professional in the past 12 months (Fig. 1). Panelists who had seen an out-of-network physician or mental health professional were asked to complete the survey. We defined a mental health professional as, “A person trained to diagnose and treat emotional or mental health problems: including, psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, social workers.” Enrollment was closed when a predetermined number of panelists screened in and began the 10-minute survey, resulting in a completion rate of 64% (13,900 panelists).

Figure 1.

Selection of survey respondents.

Respondents were asked to identify the first out-of-network physician (or mental health professional) seen in the past 12 months, and their first contact with that physician, to create a representative sample of outpatient, and inpatient out-of-network contacts. A maximum of 3 out-of-network contacts were assessed.

If the respondent reported using a general medical physician or mental health professional within the last 12 months (either in-network or out-of-network), they were included in the general medical or mental health sample, respectively. These samples are not mutually exclusive; 96.3% (821/849) of respondents that used a mental health provider also used a general health provider.

Respondents were asked a series of questions regarding each out-of-network contact, including the type of physician and when the respondent first learned the out-of-network status of the physician. If it was known that the physician was out-of-network at the time of the first contact, the respondent was asked to select from a list of reasons the primary reason why they decided to use the physician. Free text answers were also allowed. We grouped reasons into 2 broad categories: issues related to provider quality and issues related to network size and composition. We considered the reason, “continuity with previously known provider” to relate to provider quality because the desire to continue with a provider suggests either the patient perceived the provider to be of high quality or believed that the patient-provider dyad would lead to improved health outcomes.

Apart from overall health status, patient demographic information was previously collected by Knowledge Networks and not reassessed, limiting the specific demographic information available for analysis. The number of psychiatrists and psychologists per county were obtained from the Health Resources and Services Administration Area Resource File. These were used to categorize respondents into quartiles based on the number of mental health providers per 100,000 persons for each participant’s county.13

All reported analyses were weighted. Reported sample sizes were unweighted. Simple frequencies and χ2 tests were used for categorical variables and logistic regression was used to calculate the odds of any mental health or general medical out-of-network use controlling for available demographic variables. We did not include the number of psychologists in the preferred model because of the high prevalence of missing data and colinearity (Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.51) with number of psychiatrists. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Survey design, cognitive interviewing, and pretesting were conducted by the authors. The contracted company, Knowledge Networks, provided the infrastructure for sampling and distribution of the survey to their online panelists. Completed survey data were weighted and deidentified by Knowledge Networks, then delivered to the authors. Data analysis and interpretation were completed by the authors. The Yale University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

The sample included 849 respondents aged 18–64 enrolled in private health plans with provider networks who had at least 1 mental health professional contact within the last 12 months. Approximately 18% (n = 163) used an out-of-network mental health professional (Table 1). The rate of out-of-network use among individuals with at least 1 general medical contact was 6.8%, which was significantly different than the rate for the mental health population (P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Total Sample and Out-of-Network Use by Demographic Characteristics for Mental Health and General Medical Populations

| Characteristics | Total General Medical Sample Unweighted n (Weighted % of Total Sample) | General Medical Out-of-Network Use* Unweighted n (Weighted % of Row Characteristics) | P** | Total Mental Health Sample Unweighted n (Weighted % of Total Sample) | Mental Health Out-of-Network Use* Unweighted n (Weighted % of Row Characteristic) | P** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 7786 (100%) | 602 (6.8%) | 849 (100%) | 163 (18.1%) | ||

| Age | 0.007 | 0.67 | ||||

| 18–29 | 528 (18.1%) | 51 (9.2%) | 73 (20.1%) | 12 (14.6%) | ||

| 30–49 | 2742 (43.8%) | 165 (5.3%) | 329 (46.0%) | 66 (19.4%) | ||

| 50–64 | 4516 (38.2%) | 386 (7.3%) | 447 (33.9%) | 85 (18.4%) | ||

| Sex | 0.002 | 0.02 | ||||

| Male | 2041 (43.7%) | 132 (5.2%) | 209 (41.9%) | 26 (12.9%) | ||

| Female | 5745 (56.3%) | 470 (8.0%) | 640 (58.1%) | 137 (21.9%) | ||

| Race | 0.98 | 0.24 | ||||

| White | 6498 (75.1%) | 514 (6.8%) | 731 (76.0%) | 148 (19.8%) | ||

| Nonwhite | 1288 (24.9%) | 88 (6.8%) | 118 (24.0%) | 15 (12.8%) | ||

| Marital status | 0.02 | 0.27 | ||||

| Married/living with partner | 5840 (71.9%) | 426 (6.1%) | 572 (60.6%) | 104 (15.5%) | ||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 1063 (10.6%) | 84 (7.0%) | 146 (14.1%) | 34 (21.5%) | ||

| Never married | 883 (17.5%) | 92 (9.6%) | 131 (25.3%) | 25 (22.5%) | ||

| Education | 0.20 | 0.36 | ||||

| High school or less | 881 (26.4%) | 47 (5.5%) | 83 (22.7%) | 8 (12.1%) | ||

| Some college | 2758 (31.0%) | 207 (7.7%) | 285 (31.7%) | 54 (19.4%) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 4147 (42.6%) | 348 (6.9%) | 481 (45.6%) | 101 (20.2%) | ||

| Income (per year) | < 0.0001 | 0.005 | ||||

| < $35,000 | 822 (14.0%) | 68 (10.9%) | 113 (19.0%) | 20 (16.9%) | ||

| $35,000–$59,000 | 1848 (27.5%) | 103 (4.4%) | 199 (29.2%) | 26 (8.6%) | ||

| $60,000–$100,000 | 2847 (34.5%) | 218 (6.0%) | 299 (30.0%) | 54 (21.2%) | ||

| > $100,000 | 2269 (23.9%) | 213 (8.4%) | 238 (21.8%) | 63 (27.5%) | ||

| Residence in metropolitan area | 0.34 | 0.52 | ||||

| Yes | 6798 (86.4%) | 533 (7.0%) | 767 (89.3%) | 148 (18.5%) | ||

| No | 988 (13.6%) | 69 (5.7%) | 82 (10.7%) | 15 (15.0%) | ||

| Region of country | 0.48 | 0.20 | ||||

| Northeast | 1429 (20.8%) | 126 (7.4%) | 177 (25.2%) | 44 (20.6%) | ||

| Midwest | 2290 (24.0%) | 151 (5.8%) | 226 (22.4%) | 25 (10.6%) | ||

| South | 2277 (33.4%) | 182 (7.3%) | 245 (32.4%) | 52 (20.9%) | ||

| West | 1790 (21.8%) | 143 (6.4%) | 201 (19.9%) | 42 (18.8%) | ||

| Health status (self-reported) | 0.03 | 0.92 | ||||

| Excellent, very good or good | 7146 (91.5%) | 539 (6.5%) | 748 (86.3%) | 148 (18.2%) | ||

| Fair or poor | 625 (8.5%) | 63 (10.4%) | 101 (13.7%) | 15 (17.5%) | ||

| No. psychiatrists per 100,000 | 0.07 | |||||

| < 7 | — | — | 200 (23.6%) | 27 (15.6%) | ||

| 7–12 | — | — | 195 (26.1%) | 39 (28.8%) | ||

| 13–18 | — | — | 202 (27.7%) | 36 (23.1%) | ||

| ≥ 19 | — | — | 206 (22.6%) | 51 (32.6%) |

n’s may not sum to total due to missing data. Mental health and general medical samples are not mutually exclusive as some participants may have accessed both types of providers.

Outcomes include at least one inpatient or outpatient mental health or general medical out-of-network contact for the mental health and general health samples, respectively.

P-value is for chi-squared test. Bold numbers indicate significance at 5 percent level.

In adjusted logistic regression (Table 2, Model 1), a significantly greater proportion of never married individuals than those married or living with a partner had contact with out-of-network mental health professionals (odds ratio, 3.03; 95% confidence interval, 1.41–6.51). Individuals residing in a county with the highest quartile density of psychiatrists (19 or higher per 100,000 residents) were more likely than individuals residing in a county with the lowest quartile density of psychiatrists (< 7 per 100,000 residents) to use an out-of-network mental health provider (odds ratio, 2.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.10–4.93).

Table 2.

Predictors of Out-of-Network Use among Mental Health and General Medical Populations

| Characteristics | Out-of-Network Use† Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health n = 849

|

|||

| General Medical n = 7786 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Age | |||

| 18–29 | 1.12 (0.73–1.71) | 0.48 (0.19–1.25) | 0.59 (0.22–1.54) |

| 30–49 | 0.72* (0.55–0.94) | 1.17 (0.70–1.97) | 1.16 (0.67–1.99) |

| 50–64 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Female | 1.50* (1.11–2.04) | 1.66 (0.96–2.89) | 1.51 (0.84–2.73) |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Nonwhite | 0.96 (0.67–1.38) | 0.59 (0.28–1.27) | 0.57 (0.26–1.28) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/living with partner | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 0.99 (0.65–1.52) | 1.88 (0.95–3.71) | 1.88 (0.91–3.89) |

| Never married | 1.42 (0.94–2.14) | 3.03* (1.41–6.51) | 2.87* (1.35–6.12) |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Some college | 1.33 (0.86–2.07) | 1.33 (0.50–3.52) | 1.15 (0.42–3.16) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 1.26 (0.81–1.97) | 1.21 (0.47–3.11) | 1.06 (0.40–2.80) |

| Income (per year) | |||

| < $35,000 | 1.21 (0.76–1.95) | 0.47 (0.20–1.08) | 0.47 (0.20–1.12) |

| $35,000–$59,000 | 0.48* (0.33–0.72) | 0.22* (0.10–0.49) | 0.22* (0.09–0.51) |

| $60,000–$100,000 | 0.71* (0.52–0.97) | 0.67 (0.36–1.25) | 0.80 (0.41–1.55) |

| > $100,000 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Residence in metropolitan area | |||

| Yes | 1.12 (0.72–1.74) | 1.02 (0.43–2.42) | 0.69 (0.22-2.17) |

| No | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Region of country | |||

| Northeast | 1.19 (0.80–1.77) | 1.01 (0.50–2.04) | 0.90 (0.44–1.87) |

| Midwest | 0.96 (0.66–1.39) | 0.42* (0.20–0.89) | 0.34* (0.15–0.81) |

| South | 1.18 (0.81–1.71) | 1.19 (0.60–2.35) | 1.29 (0.67–2.51) |

| West | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Health status (self-reported) | |||

| Excellent, very good or good | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Fair or poor | 1.74* (1.11–2.73) | 1.27 (0.56–2.86) | 1.39 (0.59–3.31) |

| No. psychiatrists per 100,000 | |||

| < 7 | — | — | 1 (reference) |

| 7–12 | — | — | 1.66 (0.77–3.56) |

| 13–18 | — | — | 1.46 (0.65–3.27) |

| ≥ 19 | — | — | 2.33* (1.10–4.93) |

Model 2 includes number of psychiatrists per 100,000.

P < 0.05.

Models predict any out-of-network use and include either inpatient or outpatient contacts.

For both mental health and general health care, the most common reasons respondents reported for using out-of-network mental and general health care related to provider quality or perceived provider quality (Table 3). The 3 most common reasons reported related to mental health care were, the physician was recommended (26.1%), continuity with previous known provider (23.7%), and skill of physician (19.3%). Fewer respondents noted reasons related to network size and composition, such as appointment wait time, convenient location, service or specialty not covered by insurance, needed care right away, or no in-network availability. In aggregate, network size and composition reasons were much less commonly cited as reasons for going out-of-network for mental health care (7.5%) than for general health care (19.6%).

Table 3.

Reasons for Voluntary Outpatient Out-of-Network Use

| Primary Reason*§ | General Medical Contacts Unweighted n (Weighted%) | Mental Health Contacts Unweighted n (Weighted %) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 494 (100%) | 161 (100.0%) |

| Issues related to provider quality | ||

| Recommendation of another doctor, family, or friends | 72 (12.9%) | 39 (26.1%) |

| Continuity with previously known provider | 140 (21.9%) | 35 (23.7%) |

| Physician skill | 85 (13.7%) | 38 (19.3%) |

| Second opinion | 6 (0.8%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| Issues related to provider network size and composition | ||

| Could schedule appointment sooner | 5 (1.0%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Convenient location | 13 (3.7%) | 3 (1.9%) |

| Service or specialty not covered by insurance | 11 (1.4%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| Illness that needed care right away | 27 (9.0%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| No in-network physician available in area | 14 (4.5%) | 2 (0.6%) |

| Other | 39 (12.0%) | 20 (11.4%) |

| Refused | 1 (0.3%) | — |

| Missing | 81 (18.9%) | 15 (11.8%) |

Unit of analysis is contacts between the respondents and out-of-network providers. A respondent could report contacts with up to 2 different outpatient out-of-network providers.

Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

Participants were asked to indicate 1 main reason among all reasons selected for why they used an out-of-network physician.

P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

We found that 18.1% of individuals who used a mental health provider in the past year had at least 1 contact with an out-of-network mental health provider. This differs notably from general medical care, where the rate of out-of-network service use was 6.8%.

In adjusted analyses, residence in a county with a relatively high number of psychiatrists per capita was positively associated with out-of-network use. This was unexpected. We hypothesized that psychiatrists in areas with constrained provider supply would be less likely to participate in networks, resulting in more out-of-network use. We note that this finding is consistent with Cunningham (2009) who found that greater psychiatrist supply was associated with primary care providers’ report of health plan barriers to referring patients to outpatient mental health providers. He hypothesized that this was because residents of areas with greater provider supply used more mental health care, leading plans to restrict use with tighter management controls.14

Most respondents reported choosing an out-of-network mental health provider based on issues related to provider quality. Fewer than 10% of respondents who used out-of-network mental health services reported that they went to an out-of-network mental health provider due to problems with the size or general composition of the network (as opposed to inclusion of a specific provider). We were unable to obtain information on whether individuals stayed in-network or did not seek care due to network constraints. Consequently, it is not possible from our data to determine whether or not mental health networks are generally adequate. Yet, we found no evidence that mental health networks were substantially less adequate than general medical networks.

The desire to maintain continuity of care was one of the most commonly cited reasons for choosing to go out-of-network. This is worrisome; although use of an out-of-network provider to maintain continuity of care reflects patient perceptions of provider quality, it may also reflect issues related to network size and composition. A network with greater provider turnover will be less adequate for patients interested in continuity of care compared with a network with less turnover. To the extent that having a continuous relationship with a mental health provider leads to better health outcomes,15 networks may reduce quality of care along dimensions not captured by our survey.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this cross-sectional study. First, the survey relied on self-report. Several measures were taken to mitigate recall bias: the reference period was limited to the last 12 months, cognitive interviewing was used, and hyperlinks to definitions for potentially confusing terms were available in the online survey. Second, because we used an internet survey, our results may not be representative. Yet, the probability-based sampling used by Knowledge Networks includes noninternet households and poststratification weights adjusted for internet use, as well as nonresponse.

Third, our data only indicate if the patient used a mental health provider and do not specify the type of provider (eg, psychiatrist, social worker) or the type of service provided (eg, medication management, psychotherapy). Furthermore, some mental health services may have been included under general health care if delivered by primary care providers. Future studies should clarify the effects of these specifics as they may elucidate reasons for high rates of out-of-network care in mental health and have important implications for network adequacy requirements.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that almost 1 in 5 individuals using mental health care saw an out-of-network provider in the past year, more than double the rate found in the general medical population. This discrepancy may be due to a variety of factors, including patient preferences, issues related to the construction of mental health provider networks, or lack of transparency in the out-of-network status of mental health providers. However, although we are unable to fully describe network adequacy from our survey, we did not find evidence to suggest that provider network access for mental health care was more problematic than provider access in general health care.

Our findings suggest that mental health patients were willing to pay more for an out-of-network provider who the patient perceived was high quality and with whom they already had an established relationship. This has important implications for the management of health plans. Continuity and the therapeutic relationship cultivated between provider and patient are valued by patients and the additional costs of seeing a previously in-network provider on an out-of-network basis perhaps could be mitigated with either more stable networks or more consistent plan options. Insurers and providers could limit frequent changes and discontinuation of contracts. Employers could minimize yearly changes in plans offered. These efforts may decrease out-of-network use and allow for continuity of care at lower out-of-pocket costs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the Women’s Health Research at Yale Pilot Project Program and funding from the Yale Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. The sponsors were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

K.A.K. has accepted consulting fees from the Consumers Union, a nonprofit organization dedicated to consumer protection and FAIR Health Inc., an independent, nonprofit organization with the mission to ensure fairness of out-of-network reimbursement. These consulting activities are in topic areas outside of the submitted manuscript, but both entities may be perceived to have interest in the manuscript content. S.H.B. serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of FAIR Health Inc., and has received payment for that service.

Footnotes

Presented as an abstract for poster presentation at the 23rd Annual United Hospital Fund Symposium on Health Care Services in New York: Research and Practice, October 24, 2012.

L.A.C. declares no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

References

- 1.Cunningham PW. Loophole for mental health care. Politico. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieber R. Walking the tightrope on mental health coverage. New York Times. 2012:B1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Malley AS, Reschovsky JD. No Exodus: Physicians and Managed Care Networks. Center for Studying Health System Change; 2006. p. 14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albizu-Garcia CE, Rios R, Juarbe D, et al. Provider turnover in public sector managed mental health care. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31:255–265. doi: 10.1007/BF02287289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regier DA, Bufka LF, Whitaker T, et al. Parity and the use of out-of-network mental health benefits in the FEHB program. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:w70–w83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.w70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank RG, Glazer J, McGuire TG. Measuring adverse selection in managed health care. J Health Econ. 2000;19:829–854. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(00)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis R. The Effect of Prior Year Health Expenditures on Health Coverage Plan Choice, in Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein BD, Meili R, Tanielian TL, et al. Outpatient mental health utilization among commercially insured individuals: in- and out-of-network care. Med Care. 2007;45:183–186. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244508.55923.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyanko KA, Curry LA, Busch SH. Out-of-network physicians—how prevalent are involuntary use and cost transparency? Health Serv Res. 2013;48:1154–1172. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.KnowledgeNetworks. [April 13, 2013];Methodological Papers, Presentations, and Articles on KnowledgePanel 2012. Available at: http://www.knowl-edgenetworks.com/ganp/reviewer-info.html.

- 12.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Singer S, et al. Validity of the Survey of Health and Internet and Knowledge Network’s Panel and Sampling. Stanford, CA: Standford University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Resources and Service Administration. [April 30, 2012];Area Resource File. 2012 Availavle at: http://arf.hrsa.gov/

- 14.Cunningham P. Beyond parity: primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Aff (Project Hope) 2009;28:w490–w501. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adair CEMG, Mitton CR, Joyce AS, et al. Psychiatr Serv. Vol. 56. Washington, DC: 2005. Continuity of care and health outcomes among persons with severe mental illness; pp. 1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.