Abstract

Invertebrates can be primed to enhance their protection against pathogens they have encountered before. This enhanced immunity can be passed maternally or paternally to the offspring and is known as transgenerational immune priming. We challenged larvae of the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum by feeding them on diets supplemented with Escherichia coli, Micrococcus luteus or Pseudomonas entomophila, thus mimicking natural exposure to pathogens. The oral uptake of bacteria induced immunity-related genes in the offspring, but did not affect the methylation status of the egg DNA. However, we observed the translocation of bacteria or bacterial fragments from the gut to the developing eggs via the female reproductive system. Such translocating microbial elicitors are postulated to trigger bacterial strain-specific immune responses in the offspring and provide an alternative mechanistic explanation for maternal transgenerational immune priming in coleopteran insects.

Keywords: transgenerational immune priming, innate immunity, parental investment, fitness costs, maternal inheritance, Tribolium castaneum

1. Introduction

Invertebrates can mount specific immune responses against previously encountered pathogens [1,2], although this phenomenon varies in its specificity [3,4]. The priming effect can even be transferred to the next generation to increase offspring survival following exposure to the same pathogen. This effect, known as transgenerational immune priming (TGIP), has been described for crustaceans [1], insects [5] and molluscs [6]. Both males and females can deliver information about the pathogens they have encountered to their offspring, but maternal and paternal TGIP in beetles differs in terms of specificity and the investment of resources [6–9].

The mechanisms underlying TGIP are not clearly understood. Passive mechanisms such as the transfer of antimicrobial peptides or mRNAs encoding immunity-related proteins would confer transient immunity, but full protection would require a more stable mechanism, and epigenetic modifications have been proposed. The latter include, for example, changes in DNA methylation in the parental genome caused by the first encounter with a pathogen that is transferred to the offspring as a methylation imprint in the eggs and sperm, allowing the pre-emptive activation of immunity-related genes [10,11]. Recently, a new TGIP mechanism was identified in the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella involving the transfer of ingested bacteria from the maternal gut to the eggs [12].

To determine whether similar TGIP mechanisms may be involved in T. castaneum, an insect that is now established as a model for bacterial oral infections [13] and in which both maternal and paternal TGIP have already been confirmed [14], we investigated the transfer of bacterial particles ingested by female beetles and the methylation status of DNA in the offspring.

2. Material and methods

(a). Insect rearing and treatment

Wild-type Tribolium castaneum San Bernardino beetles were reared as described elsewhere [15]. Neonate larvae were fed until the adult stage on diets supplemented with 0.3% lyophilized Escherichia coli, Micrococcus luteus or Pseudomonas entomophila. A non-supplemented diet was used as a control treatment. The adults were removed at 10 days old and transferred to the control diet. Eggs were collected by sieving after 24 h.

(b). RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from pooled eggs (50 mg, three biological replicates) using Direct-zol™ RNA MiniPrep (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quality and quantity of RNA were determined using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE). We reverse transcribed 50 ng total RNA using the first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and carried out quantitative real-time PCR using the Power SYBR® Green PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a StepOne plus real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primers were designed using primer3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/) and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO).

Three biological replications, each with two technical replications and no template controls, were run in parallel. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [16] with the ribosomal protein gene Rps3 as a reference. Statistical analysis was carried out using SigmaPlot v. 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). Significant differences between groups of parametric data were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a subsequent Holm–Sidak test (p < 0.05). Non-parametric data were analysed by ANOVA on-ranks with a subsequent Tukey's test.

(c). Methylation assay

Eggs (50 mg, three biological replicates) from adults (5–7 days old) raised on white flour supplemented with bacteria (see above) were collected for DNA isolation using the ZR Tissue and Insect MicroPrep kit (ZymoResearch), and the global DNA methylation status was determined using the colorimetric MethylFlash methylated DNA quantification kit (Epigentek, Farmingdale, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absolute amount of methylated DNA was calculated from 100 ng total DNA using a standard curve.

(d). Analysis of fluorescent BioParticles®

Animals were fed on an artificial agar-based diet containing 5% whole wheat flour, 15% yeast, 3% agar and 0.4% methyl hydroxybenzoate. The artificial diet was supplemented with E. coli (K-12 strain) cells (3 × 106 E. coli µl−1) conjugated with 25 µl Texas Red® BioParticles® (Thermo Fisher Scientific) per 1 ml agar, suspended at a concentration of 10 mg ml−1 in 10 mM PBS. Decapitated last-instar larvae and adult females, as well as dissected reproductive tissue and ovipositioned eggs, were embedded in Tissue-Tek® OCT™ (Sakura® Finetek). Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C. A cryostat microtome CM 1850 (Leica Microsystems) was used to prepare 10 µm sections at –20°C and these were mounted with Fluoromount-GTM (Southern Biotech) and observed under a DM5000 B fluorescence microscope (Leica; see the electronic supplementary material).

3. Results

(a). Expression of immunity- and stress-related genes

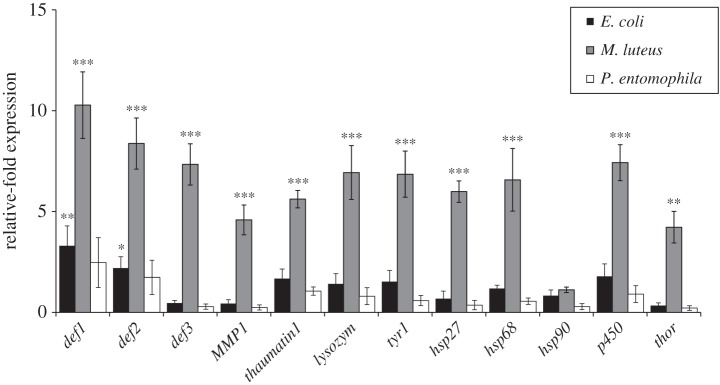

We compared the expression profiles of immunity- and stress-related genes in eggs laid by naive parents, and adults reared on diets supplemented with E. coli, M. luteus or P. entomophila. Quantitative real-time PCR data for seven immunity-related genes and five stress-related genes (encoding cytochrome p450, Thor and heat shock proteins (hsp) 27, 68 and 90) showed that the offspring of beetles ingesting M. luteus displayed by far the highest expression levels. With the exception of hsp90, all genes were induced by more than fourfold compared with the control treatment (figure 1). Defensin 1 was induced most strongly, with expression levels increasing by more than 10-fold (mean fold change = 10.27). Contamination of the larval diet with E. coli induced the expression of defensin 1 (mean fold change = 3.31) and defensin 2 (mean fold change = 2.2) in the eggs, whereas genes encoding thaumatin 1, p450, lysozyme and polyphenoloxidase were only marginally upregulated. Surprisingly, the oral uptake of P. entomophila had a much lower impact on gene expression, resulting in the slight induction of defensin 1 (mean fold change = 2.47).

Figure 1.

Relative expression levels of immunity- and stress-related genes in naive Tribolium castaneum eggs. RNA was isolated from pooled 50 mg samples of eggs laid by parents fed on bacterial diets. Expression levels are presented relative to eggs from non-supplemented diet and normalized against the endogenous housekeeping gene Rps3. The data represent means (±s.d.) of three independent biological replicates (one-way ANOVA, Holm–Sidak, ***p < 0.001).

(b). Maternal transfer of bacteria

The underlying physiological mechanisms of TGIP are not well understood, and several hypotheses have been proposed to explain how such information might be transferred to the offspring. One hypothesis involves the epigenetic modification of germline DNA [17]. We therefore analysed the global DNA methylation status of eggs laid by parents ingesting diets supplemented with P. entomophila, E. coli or M. luteus, compared with DNA from eggs laid by naive parents. We found no significant differences among the treatments. The average level of global methylation was approximately 10% (10.17% ± 0.75) under all treatment regimens (electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

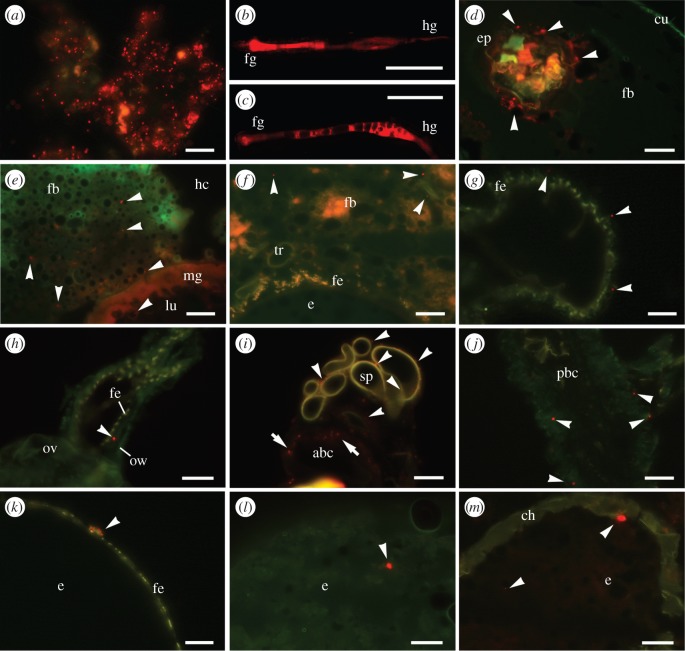

We investigated whether ingested bacteria are translocated from the gut into the developing eggs in T. castaneum by determining the fate of non-viable E. coli bioparticles after larval ingestion (figure 2). We established an artificial feeding assay to administer high doses of bioparticles to the larvae (electronic supplementary material, figures S2 and S3). Cryosections of last-instar larvae confirmed the translocation of fluorescent bacterial particles from the midgut epithelium into the surrounding fat body cells in the haemocoel following oral uptake (figure 2e and electronic supplementary material, figure S4). The genital regions of adult females fed on a diet supplemented with bacteria also contained bacterial particles attached to the fat body (figure 2f), and particles were also detected between the ovariole wall and the follicular epithelium of the developing eggs (figure 2k–l and electronic supplementary material, figure S5). Ultimately, we confirmed the presence of bacterial particles in the ovipositioned eggs (figure 2m and electronic supplementary material, figure S6).

Figure 2.

Analysis of the maternal transfer of fluorescent bacteria (BioParticles®). (a) Artificial diet mixed with BioParticles® (scale bar, 50 µm). (b,c) BioParticles® in the dissected larval gut after the ingestion of the artificial diet, show (b) the foregut and midgut region and (c) the hindgut (scale bars, 1 mm). (d) BioParticles® beneath the cuticle of the larval foregut (scale bar, 100 µm). (e) Larval midgut containing translocated BioParticles® in the lumen and surrounding fat body cells (scale bar, 50 µm). (f) Female genital region with BioParticles® attached to the fat body (scale bar, 50 µm). (g,h) BioParticles® between the ovariole wall and the follicular epithelium of eggs in (g) the proximal region (scale bar, 50 µm) and (h) the distal region close to the lateral oviduct (scale bar, 150 µm). (i,j) BioParticles® associated with (i) spermatheca and the anterior bursa copulatrix, and (j) the posterior bursa copulatrix (scale bars, 50 µm). (k,l) BioParticles® attached to (k) the follicular epithelium (scale bar, 50 µm) and (l) incorporated into the yolk of dissected eggs (scale bar, 150 µm). (m) Ovipositioned egg containing BioParicles® (scale bar, 150 µm). Further details are provided in the electronic supplementary material. Arrowheads indicate fluorescent BioParticles® (red spots). abc, anterior bursa copulatrix; ch, chorion; cu, cuticle; e, egg; ep, epithelium; fb, fatbody; fe, follicular epithelium; fg, foregut; hc, haemocoel; hg, hindgut; lu midgut lumen; mg, midgut; ov, oviduct, ow ovariole wall; pbc posterior bursa copulatrix; sp, spermatheca; tr, tracheole.

4. Discussion

We investigated the processes underlying maternal TGIP in T. castaneum, focusing on two proposed mechanisms: the transfer of ingested bacterial particles from the larval gut to the eggs of adult female beetles and the methylation status of the maternal and offspring DNA. We found that the oral administration of bacteria to T. castaneum larvae was sufficient to induce an immune response in the next generation. Similar TGIP effects have been observed in lepidopteran species ingesting a diet supplemented with bacteria [12] and in the offspring of mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) injected with bacterial lipopolysaccharides [18]. The gene expression profiles in the eggs T. castaneum larvae fed with contaminated diet suggested that the immune response differs between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

The physiological processes underlying TGIP remain elusive. Microbial pathogens can modulate host epigenetic regulatory factors such as the acetylation or deacetylation of histones and the expression of miRNAs, suggesting that transgenerational inheritance may be associated with epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation [11,19]. However, T. castaneum larvae reared on a bacteria-supplemented diet did not transmit changes in the overall level of DNA methylation to the next generation, but this does rule out the possibility that differences in DNA methylation pattern may pass to the offspring. Further research is necessary to determine whether other epigenetic mechanisms such as histone acetylation are involved.

We therefore monitored the fate of bacterial particles orally administered to T. castaneum larvae and found that they crossed the gut epithelium and were translocated into the developing egg. Such a transfer of bacteria to the germline necessitates the protection of the eggs against pathogens. Indeed, the extraembryonic serosa of T. castaneum eggs is described as a frontier epithelium that expresses nearly 90% of the immunity-related genes in the egg genome, providing a full range of immune responses [20]. Such an investment in the immune competence of the serosa makes sense if bacteria from the gut can translocate into the developing eggs. Indeed, a recent study shows that the egg yolk protein vitellogenin is involved in the internalization of bacteria during oogenesis [21]. Our data provide a plausible explanation for maternal strain-specific TGIP in the model beetle T. castaneum and confirm the mechanism identified in lepidopteran species, suggesting that it may be a general strategy used by diverse insects. However, the maternal transfer of bacterial fragments does not explain paternal TGIP in T. castaneum [8], and the latter will therefore be addressed in our future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Richard M. Twyman for editing the manuscript.

Data accessibility

Additional data and control experiments for the microscopic studies are accessible in the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

E.K., L.B., H.S. and D.A. carried out the molecular laboratory work, participated in data analysis, carried out sequence alignments, participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript; E.K. carried out the statistical analyses; H.S. did the microscopic analyses, A.V. conceived, designed and coordinated the study and helped draft the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for the content and gave approval for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest, and all data are accessible in the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

A.V. acknowledges generous funding by the Hessen State Ministry of Higher Education, Research and the Arts (HMWK) via the ‘LOEWE Center for Insect Biotechnology and Bioresources’ by the German Research Foundation for the project ‘the role of epigenetics in host-parasite-coevolution’ (VI 219/3-2) which is embedded within the DFG Priority Programme 1399 ‘Host-parasite coevolution—rapid reciprocal adaptations and its genetic basis’.

References

- 1.Little TJ, O'Connor B, Colegrave N, Watt K, Read AF. 2003. Maternal transfer of strain-specific immunity in an invertebrate. Curr. Biol. 13, 489–492. ( 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00163-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmid-Hempel P. 2005. Natural insect host–parasite systems show immune priming and specificity: puzzles to be solved. Bioessays 27, 1026–1034. ( 10.1002/bies.20282) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadd BM, Schmid-Hempel P. 2006. Insect immunity shows specificity in protection upon secondary pathogen exposure. Curr. Biol. 16, 1206e10. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.047) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanchi C, Troussard JP, Moreau J, Moret Y. 2012. Relationship between maternal transfer of immunity and mother fecundity in an insect. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 3223–3230. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.0493) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadd BM, Kleinlogel Y, Schmid-Hempel R, Schmid-Hempel P. 2005. Trans-generational immune priming in a social insect. Biol. Lett. 1, 386–388. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0369) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yue F, Zhou Z, Wang L, Ma Z, Wang J, Wang M, Zhang H, Song L. 2013. Maternal transfer of immunity in scallop Chlamys farreri and its trans-generational immune protection to offspring against bacterial challenge. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 41, 569–577. ( 10.1016/j.dci.2013.07.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher J, Hajek A. 2015. Maternal exposure of a beetle to pathogens protects offspring against fungal diseases. PLoS ONE 10, e0125197 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0125197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth O, Joop G, Eggert H, Hilbert J, Daniel J, Schmid-Hempel P, Kurtz J. 2010. Paternally derived immune priming for offspring in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. J. Anim. Ecol. 79, 403–413. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01617.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanchi C, Troussard JP, Martinaud G, Moreau J, Moret Y. 2011. Differential expression and costs between maternally and paternally derived immune priming for offspring in an insect. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1174–1183. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01872.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richards EJ. 2006. Inherited epigenetic variation - revisiting soft inheritance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 395–401. ( 10.1038/nrg1834) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukherjee K, Twyman RM, Vilcinskas A. 2015. Insects as models to study the epigenetic basis of disease. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 118, 69–78. ( 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.02.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freitak D, Schmidtberg H, Dickel F, Lochnit G, Vogel H, Vilcinskas A. 2014. The maternal transfer of bacteria can mediate trans-generational immune priming in insects. Virulence 5, 547–554. ( 10.4161/viru.28367) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milutinović B, Fritzlar S, Kurtz J. 2014. Increased survival in the red flour beetle after oral priming with bacteria-conditioned media. J. Innate Immun. 6, 306–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eggert H, Kurtz J, Diddens-de Buhr MF. 2014. Different effects of paternal trans-generational immune priming on survival and immunity in step and genetic offspring. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20142089 ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.2089) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knorr E, Schmidtberg H, Vilcinskas A, Altincicek B. 2009. MMPs regulate both development and immunity in the Tribolium model insect. PLoS ONE 4, e4751 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0004751) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, e45 ( 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gómez-Díaz E, Jordà M, Peinado MA, Rivero A. 2012. Epigenetics of host-pathogen interactions: the road ahead and the road behind. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1003007 ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moret Y. 2006. Trans-generational immune priming: specific enhancement of the antimicrobial immune response in the mealworm beetle, Tenebrio molitor. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1399–1405. ( 10.1098/rspb.2006.3465) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freitak D, Knorr E, Vogel H, Vilcinskas A. 2012. Gender- and stressor-specific microRNA expression in Tribolium castaneum. Biol. Lett. 8, 860–863. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0273) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs CG, Spaink HP, van der Zee M. 2014. The extraembryonic serosa is a frontier epithelium providing the insect egg with a full-range innate immune response. eLife 3, e04111 ( 10.7554/eLife.04111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salmela H, Amdam GV, Freitak D. 2015. Transfer of immunity from mother to offspring is mediated via egg-yolk protein vitellogenin. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005015 ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Additional data and control experiments for the microscopic studies are accessible in the electronic supplementary material.