Abstract

This review summarizes recent evidence related to the safety, efficacy, and metabolic outcomes of bariatric surgery to guide clinical decision making. Several short term randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of bariatric procedures for inducing weight loss and initial remission of type 2 diabetes. Observational studies have linked bariatric procedures with long term improvements in body weight, type 2 diabetes, survival, cardiovascular events, incident cancer, and quality of life. Perioperative mortality for the average patient is low but varies greatly across subgroups. The incidence of major complications after surgery also varies widely, and emerging data show that some procedures are associated with a greater risk of substance misuse disorders, suicide, and nutritional deficiencies. More research is needed to enable long term outcomes to be compared across various procedures and subpopulations, and to identify those most likely to benefit from surgical intervention. Given uncertainties about the balance between the risks and benefits of bariatric surgery in the long term, the decision to undergo surgery should be based on a high quality shared decision making process.

Introduction

Although the global pandemic of obesity has continued unabated over the past two decades, little progress has been made in its behavioral and drug treatment, especially in patients with severe obesity. By contrast, the evidence base for bariatric surgical procedures has expanded rapidly over this time, and it has yielded important short term and long term data on the efficacy and safety of surgical treatment for obesity and related metabolic disorders. Because trade-offs between the potential risks and benefits of bariatric surgical procedures exist, this review of the evidence for bariatric surgery aims to guide adult patients and their clinicians through a well informed, shared decision making process.

Prevalence

Nationally representative estimates from 2009 to 2010 indicate that 35.5% of the adult population in the United States is obese (defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30).1 About 15.5% of the US adult population has a BMI of 35 or more and 6.3% are severely obese (BMI ≥40).1

Data on the prevalence of severe obesity in other countries is scant, but the health survey of England showed that 1.7% of men and 3.1% of women had a BMI of 40 or more in 2012.2 In Sweden in 2005, 1.3% of men had a BMI of 35 or more,3 and in Australia in 2006, 8.1% of adults had a BMI of 35 or more.4

The total number of bariatric procedures worldwide was estimated at 340 768 in 2011.5 The most commonly performed procedures were Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (46.6%), vertical sleeve gastrectomy (27.8%), adjustable gastric banding (17.8%), and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (2.2%).5 The largest number of operations were performed in the US and Canada together (101 645), followed by Brazil (65 000), France (27 648), Mexico (19 000), Australia and New Zealand (12 000), and the United Kingdom (10 000). No other nation performed 10 000 or more operations in 2011.5

Sources and selection criteria

We based this review on articles found by searching Medline, the Cochrane Collaboration Library, and Clinical Evidence from their inception until September 2013 with the terms “bariatric surgery”, “gastric bypass”, “gastric banding”, “sleeve gastrectomy”, and “biliopancreatic diversion”. Our search was limited to English language articles. Priority was given to evidence obtained from systematic literature reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials when possible.

Obesity related complications

Severe obesity (most often defined as a BMI ≥35 with comorbid health conditions or a BMI ≥40 without such conditions) is a highly prevalent chronic disease,1 which leads to substantial morbidity,6 premature mortality,7 impaired quality of life,8 and excess healthcare expenditures.9 Severely obese adults are disproportionately affected by chronic health conditions, such as type 2 diabetes (28% of severely obese adults),10 major depression (7%),11 coronary heart disease (14-19%),6 and osteoarthritis (10-17%).6

Treatment options

Treatments for severe obesity include lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgical procedures. Evidence from decades of weight loss research indicates that lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapy often fail to help severely obese people lose enough weight to improve their health and quality of life in the long term.12 13 14 However, a growing body of evidence indicates that bariatric surgery can induce sustained reductions in weight, improve comorbidities, and prolong survival.15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

Bariatric procedures were first developed more than 50 years ago. However, in the past 20 years, a dramatic increase in the prevalence of severe obesity combined with improvements in the efficacy and safety of bariatric surgical techniques has led to a 20-fold increase in the number of procedures performed annually in the US.25 Recent improvements in bariatric safety outcomes have been linked to an increase in the volume of cases performed, a shift to the laparoscopic technique, and an increase in the use of the lower risk adjustable gastric banding procedure.26 Current US guidelines recommend consideration of bariatric surgery for people who have not responded to non-surgical treatments if they have a BMI of at least 40 or at least 35 if they also have serious diseases related to obesity.27

Types of bariatric surgery procedures and mechanisms of weight loss

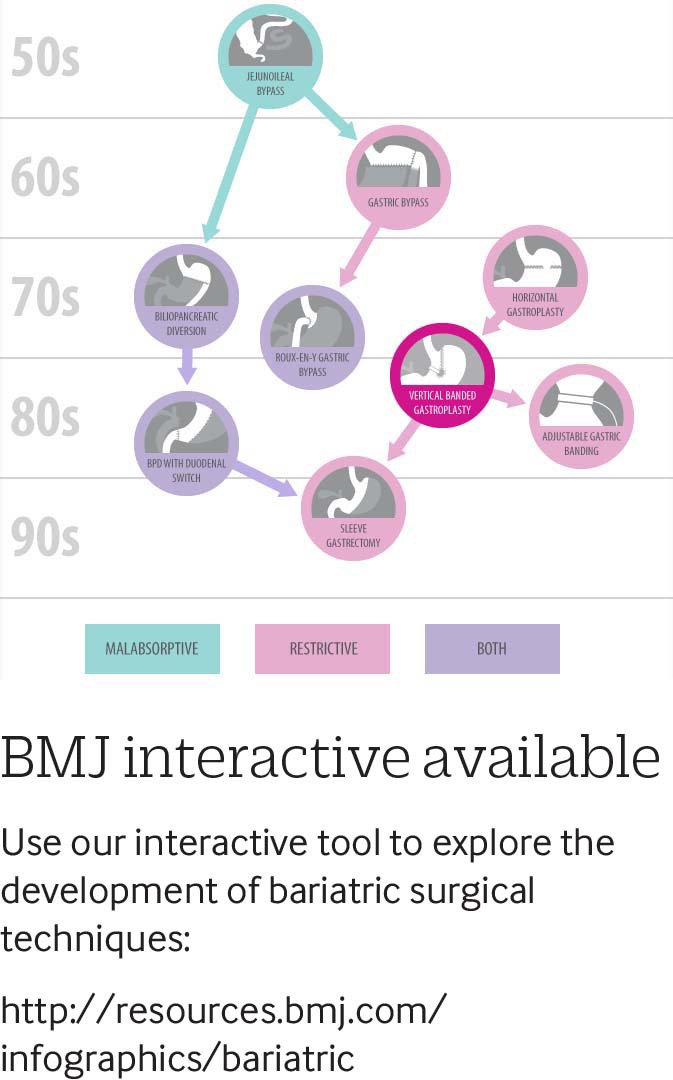

Bariatric surgical procedures have evolved dramatically over the past 50 years (fig 1 ). Modern procedures are most often described in anatomic terms according to their presumed mechanical effect, using phrases like “gastric restrictive” or “intestinal bypass” for ease of understanding, but recent basic science investigations may soon change this characterization to one based on physiology. In addition, since the 1990s the standard surgical technique has shifted from an open incisional approach to a minimally invasive or laparoscopic approach, almost exclusively.28

Fig 1 The evolution of bariatric surgery procedures. Use the interactive tool at:http://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g3961/infographic

The first bariatric procedure in wide use was known as the jejunoileal bypass, and it involved an intestinal bypass in which the proximal jejunum was bypassed into the distal ileum. This resulted in extreme weight loss by way of profound malabsorption and was eventually abandoned some years later after many patients developed severe protein-energy malnutrition.29

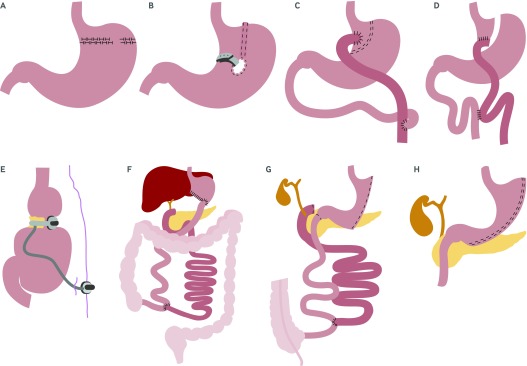

The next major bariatric procedures to be introduced were the horizontal gastroplasty and the vertical banded gastroplasty, which were thought to be purely restrictive procedures made possible through the development of surgical stapling devices. In a horizontal gastroplasty, a pouch was created in the upper stomach by introducing a horizontal suture line with several staples removed (the stoma) to allow for the passage of food (fig 2A ). With vertical banded gastroplasty, a vertical staple line was created parallel to the lesser curvature of the stomach and the outlet or stoma was reinforced with a mesh collar to prevent enlargement (fig 2B). Both procedures have now been abandoned owing to the introduction of newer more effective laparoscopic procedures, and because the stomach staple line often separated or the stoma tended to enlarge, leading to weight regain or severe gastroesophageal reflux, or both.30 31

Fig 2 (A) Horizontal gastroplasty; (B) vertical banded gastroplasty; (C) Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; (D) transected Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; (E) laparoscopic adjustable gastric band; (F) biliopancreatic diversion; (G) biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch; (H) vertical sleeve gastrectomy

The gastric bypass was originally introduced in 1969 by Mason and Ito,32 and it was later modified into a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass configuration for drainage of the proximal gastric pouch to avoid bile reflux (fig 2C).33 Over time, the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has been refined into its current laparoscopic form. This includes a small proximal gastric pouch of 15-20 mL, a measured and smaller gastric-to-intestinal stoma size (with or without cuff restriction), and a complete staple line transection to avoid staple line separation or failure (fig 2D).34

The next major procedure to be introduced was the adjustable form of gastric banding, which has been modified for laparoscopic placement and creates a small superior gastric pouch with an adjustable outlet (fig 2E).35 36 The adjustable gastric band is a silicone belt with an inflatable balloon in the lining that is buckled into a closed ring around the upper stomach. A reservoir port is placed under the skin for adjustments to the stoma size.

Two procedures that use a more extreme intestinal bypass along with some modest gastric reduction are the biliopancreatic diversion and the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch operations, which are most often used for “super” obese patients (usually BMI ≥50).37 38 39 Biliopancreatic diversion combines a subtotal (2/3rds) distal gastrectomy and a very long Roux-en-Y anastomosis with a short common intestinal channel for nutrient absorption (fig 2F). Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch combines a 70% greater curve gastrectomy with a long intestinal bypass, where the duodenal stump is defunctionalized or “switched” to a gastroileal anastomosis (fig 2G).

Finally, the most recent major bariatric procedure to be introduced is the vertical sleeve gastrectomy, and it is rapidly increasing in popularity.40 This technique consists of a 70% vertical gastric resection, which creates a long and narrow tubular gastric reservoir with no intestinal bypass component (fig 2H).

Despite the basic “restrictive” and “intestinal bypass” anatomic conceptualizations of bariatric surgical procedures, there is much research ongoing in animal and human models towards understanding their underlying mechanisms of action. These actions may be more physiological (altered gastrointestinal signals) than nutrient restrictive and are likely to be both endocrine and neuronal in nature.41

Some of the potential candidates for the mechanisms of action of bariatric procedures include alterations in ghrelin, leptin, glucagon-like peptide-1, cholecystokinin, peptide YY, gut microbiota, and bile acids.42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 It may be necessary in the future to group bariatric procedures not on the basis of anatomic surgical similarities but on how they affect key physiological variables, which would provide greater mechanistic insight into how the procedures work.41

Effectiveness of bariatric surgery compared with non-surgical management

Below we summarize key findings from randomized trials and major long term observational studies that compare bariatric procedures with non-surgical management of obesity. Table 1 provides an overview of the results of these studies in terms of weight change, remission from and incidence of type 2 diabetes, as well as long term survival.

Table 1.

Effectiveness of bariatric surgery compared with non-surgical management*

| Study | Study details | Weight change | T2DM remission | T2DM incidence | Mortality and survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis21 | Meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (n=796); cohorts include RYGB, AGB, BPD, VSG v non-surgical treatments | Bariatric surgery treatment: 1-2 year weight change, mean difference −26 kg, 95% CI −31 to −21; P<0.001 v non-surgical treatment | Bariatric surgery treatment: complete case analysis relative risk 22.1, 3.2 to 154.3; P=0.002; conservative analysis 5.3, 1.8 to 15.8; P=0.003 v non-surgical treatment | Not reported | No cardiovascular events or deaths reported after bariatric surgery or in control populations |

| Swedish Obese Subjects study18 24 | Prospective observational with matched controls (n=2010; 68% VBG, 19% banding, 13 % RYGB); 2037 matched controls | Bariatric surgery treatment: 2, 10, 15, 20 year weight change mean −23%, −17%, −16%, and −18%, respectively; matched control treatment: 2, 10, 15, 20 year weight loss mean 0%, 1%, −1%, and −1%, respectively | Bariatric surgery treatment: 2 years 72% remission (odds ratio for remission: 8.4, 5.7 to 12.5; P<0.001); 10 years 36% durable remission (3.5, 1.6 to 7.3; P<0.001) | Bariatric surgery treatment: 2, 10, and 15 years, reduced risk of developing T2DM by 96%, 84%, and 78%, respectively, in people without the condition at baseline |

Bariatric surgery treatment: 16 years, 29% lower risk of death from any cause (hazard ratio 0.71, 0.54 to 0.92; P=0.01) v usual care; common causes of death: cancer and myocardial infarction |

| Utah Mortality study17 | Retrospective observational with matched controls (7925 RYGB; 7925 weight matched controls) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Bariatric surgery treatment: average 7.1 years post-treatment, 40% (hazard ratio 0.60, 0.45 to 0.67; P<0.001), 49% (0.51, 0.36 to 0.73; P<0.001), and 92% (0.08, 0.01 to 0.47; P=0.005) reduction in all cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and T2DM mortality, respectively |

| Utah Obesity study67 | Prospective observational with matched controls; 418 RYGB; 417 bariatric surgery seekers who did not undergo surgery (control 1); 321 population based severely obese matched controls (control 2) | 6 year weight change: −27.7%, +0.2%, and 0% of initial body weight for bariatric surgery, control 1, and control 2, respectively | 6 year remission: 62%, 8%, and 6% for bariatric surgery, control 1, and control 2, respectively | 6 year incident T2DM: 2%, 17%, and 15% for bariatric surgery, control 1, and control 2, respectively | Deaths at 6 years: 12 (2.8%), 14 (3.3%), and 3 (0.93%) for bariatric surgery, control 1, and control 2, respectively |

* AGB=adjustable gastric banding; BPD=biliopancreatic diversion; LABS=Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery study; RCT=randomized controlled trial; RYGB=Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; T2DM=type 2 diabetes; VBG=vertical banded gastroplasty; VSG=vertical sleeve gastrectomy.

Randomized controlled trials

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis summarized all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that have compared bariatric surgery with non-surgical treatments for obesity.21 The review analysed 11 trials comprising 796 people with a BMI of 30-52. These studies generally focused on cohorts with type 2 diabetes with one to two years of follow-up. They provided good evidence of the effectiveness of bariatric procedures, including Roux-en-Y gastric bypass,60 61 62 adjustable gastric banding,63 64 biliopancreatic diversion,61 and vertical sleeve gastrectomy.62 These procedures resulted in greater short term (1-2 years) weight loss (mean difference −26 kg; 95% confidence interval −31 to −21; P<0.001) and greater remission of type 2 diabetes (complete case analysis relative risk of remission: 22.1, 3.2 to 154.3; P=0.002; conservative analysis: 5.3, 1.8 to 15.8; P=0.003) compared with various non-surgical treatments.60 61 62 63 64 Recently, two additional small RCTs have been published that show similar short term results for both weight loss and type 2 diabetes.65 66

In addition, serum triglycerides and high density lipoproteins were significantly reduced by bariatric procedures, but blood pressure and other lipoproteins were not (although some studies showed reduced use of drugs for these conditions).21 The review also noted a lack of evidence from RCTs beyond two years with respect to mortality, cardiovascular diseases, and adverse events.

Another recent systematic review focused on weight loss and glycemic control in class I obese (BMI 30-34.9) adults with type 2 diabetes and identified three RCTs with results similar to those seen in class II (BMI 35-39.9) and severely obese populations. However, the review also noted a lack of long term studies.22

Swedish Obese Subjects study

Given the absence of long term RCTs comparing bariatric procedures with non-surgical treatment of obesity, we must turn to large observational cohort studies to answer important questions about long term outcomes.18 24 67 68 Much of our current knowledge about the long term results of bariatric surgery come from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. This study started in 1987 as a prospective trial of 2010 people undergoing bariatric surgery compared with 2037 usual care controls who were matched on 18 clinical and demographic variables.24

The most common bariatric procedure performed in SOS was the vertical banded gastroplasty (68%), followed by gastric banding (19%), and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (13%). Follow-up rates are reported at 99% for some endpoints (including mortality), but physical and laboratory follow-up rates are lower, with imputation techniques used for sensitivity analysis.24 The SOS investigators have published widely on health outcomes beyond 10 years, including weight loss, mortality, remission from and incidence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular events, incident cancer, psychosocial outcomes, and healthcare use and costs.18 24 68 69 70 71 72

Weight loss among surgical patients in SOS was greater than in controls (mean changes in body weight at 2, 10, 15, and 20 years were −23%, −17%, −16%, and −18% in the surgery group and 0%, 1%, −1%, and −1% in the control group, respectively).24 After 15 years, the mean weight loss by procedure type was 27% (standard deviation 12%) for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 18% (11%) for vertical banded gastroplasty, and 13% (14%) for gastric banding.24

The SOS study also showed major improvements in obesity related comorbidities. In the surgical group there was a 72% remission of type 2 diabetes after two years (odds ratio for remission 8.4, 5.7 to 12.5; P<0.001) and 36% durable remission after 10 years (3.5, 1.6 to 7.3; P<0.001).69

In spite of the considerable recurrence of type 2 diabetes over time, bariatric surgery was associated with a lower incidence of myocardial infarction (hazard ratio 0.56, 0.34 to 0.93; P=0.025) and other complications of type 2 diabetes.68 73 Recently the SOS study showed that bariatric surgery also reduced the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 96%, 84%, and 78% after two, 10, and 15 years in people without the condition at baseline.74 This study also found that bariatric surgery was associated with a reduced incidence of fatal or non-fatal cancer in women but not in men (hazard ratio in women 0.58, 0.44 to 0.77; P<0.001; in men 0.97, 0.62 to 1.52; P=0.90).71 Finally, at 16 years’ follow-up, surgery was associated with a 29% lower risk of death from any cause (0.71, 0.54 to 0.92; P=0.01) compared with usual care.18

Utah obesity studies

Another important long term observational study performed in Utah from 1984 to 2002 comprised 7925 people who had undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and 7925 weight, age, and sex matched controls. This study showed a 40% reduction in all cause mortality (hazard ratio 0.60, 0.45 to 0.67; P<0.001) and a 49% (0.51, 0.36 to 0.73; P<0.001) and 92% (0.08, 0.01 to 0.47; P=0.005) reduction in death from cardiovascular disease and death related to type 2 diabetes, respectively, at an average of 7.1 years later.17

Two other large retrospective observational studies support the findings from the SOS and Utah studies that bariatric surgery is associated with lower mortality than usual care.75 76 However, another retrospective observational study of US veterans found no significant association between bariatric surgery and survival compared with usual care at a mean 6.7 years of follow-up.77 The discrepant findings of this last study are probably a result of its focus on a high risk population as well as insufficient power and duration of follow-up.

A separate ongoing prospective Utah Obesity Study looked at more than 400 people who had undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and two non-randomized matched control groups—each with about 400 severely obese subjects. One control group comprised people who had sought surgery but did not undergo the operation; the other was a population based group. The study found that those in the surgery group lost 27.7% of their initial body weight compared with 0.2% weight gain in the surgery seekers and 0% change in the population based group at six years.67 Diabetes was in remission in 62% of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass group and in only 8% and 6% of the control groups. Incident type 2 diabetes was noted in 2% of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass group and in 17% and 15% of the control groups at six years.67

The LABS-2 study

The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS-2) study deserves mention, despite not including a non-surgical control group, because it is the largest ongoing prospective multicenter observational bariatric cohort study. LABS-2 will assess weight change and comorbid conditions in 2458 participants (1738 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, 610 adjustable gastric banding, and 110 other procedures) recruited between 2005 and 2009 who have been followed for three years to date.78 In the LABS-2 cohort, median weight change was 31.5% for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and 15.9% for adjustable gastric banding after three years, with much variability in response to each surgical treatment. Remission of type 2 diabetes was noted in 67% and 28% of those who had undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and adjustable gastric banding, respectively. The incidence of type 2 diabetes was 0.9% and 3.2%, respectively, over the three years.78

Long term studies of quality of life

Few long term studies have assessed the impact of bariatric surgery on quality of life. However, three studies of six to 10 years’ duration suggest that bariatric procedures are associated with greater improvements in generic and obesity specific measures of quality of life than non-surgical care.72 79 80 Physical functioning domains seem to be more responsive to bariatric procedures than mental health domains, although more research is needed, especially in patients with class I obesity.

Effectiveness of bariatric surgery—comparisons between procedures

In the past 10 years, many systematic reviews of bariatric surgery have attempted to summarize and quantify differences in the efficacy and safety of various procedures.15 16 19 20 23 81 82 83 84 85 86 A major challenge in summarizing this literature is the fact that no single randomized trial has included all of the most common procedures (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, vertical sleeve gastrectomy, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch). Therefore, inference must be made through pooled analysis of data from many disparate randomized and non-randomized studies of bariatric surgery. In addition, no studies have examined differences in long term survival, incident cardiovascular events, and quality of life across procedures.

One of the most comprehensive systematic reviews analysed 136 studies and 22 094 patients undergoing bariatric surgery.16 However, only five of the included studies were randomized trials (28 non-RCTs and 101 uncontrolled case series), and the review did not include data on vertical sleeve gastrectomy. The review found a strong trend towards different weight loss outcomes across procedures. Weighted mean percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL) was 50% (32% to 70%) for adjustable gastric banding, 68% (33% to 77%) for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 69% (48% to 93%) for vertical banded gastroplasty, and 72% (62% to 75%) for biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. The rate of type 2 diabetes remission also varied greatly across procedures. The rate was 48% (29% to 67%) for adjustable gastric banding, 84% (77% to 90%) for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 72% (55% to 88%) for vertical banded gastroplasty, and 99% (97% to 100%) for biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. A similar pattern of disease remission was seen for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea, with the highest rates of remission seen in patients who had undergone biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, followed by Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, vertical banded gastroplasty, and lastly adjustable gastric banding.16

There is an ongoing debate about the comparative effectiveness of two of the most common procedures—adjustable gastric banding and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass—for weight loss and improvement in comorbidity. Consistent with the systematic review presented above, several other systematic reviews have concluded that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is more effective for weight loss than adjustable gastric banding.16 81 82 83 However, there have been only two small head to head RCTs (with follow-up at four and five years).87 88

Insufficient data are available from RCTs to examine differences between adjustable gastric banding and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in improvements in comorbidity. However, systematic reviews of non-randomized studies indicate greater remission of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and sleep apnea with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus adjustable gastric banding.16 81 By contrast, one systematic review of 19 long term observational studies (≥10 years’ duration; no RCTs) found a mean %EWL of 54.2% for adjustable gastric banding versus 54.0% for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.23 These discrepant data suggest that some very experienced, high volume surgical centers with rigorous programs for long term post-surgical care and follow-up may achieve weight loss results with adjustable gastric banding similar to those achieved with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. However, data from these types of centers are not often seen in the surgical literature, and more research is needed to identify the optimal requirements of an adjustable gastric banding program.

Two recent systematic reviews compared the outcomes of vertical sleeve gastrectomy with other procedures.85 86 One review identified 15 RCTs with 1191 patients.85 The %EWL ranged from 49% to 81% for vertical sleeve gastrectomy, from 62% to 94% for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and from 29% to 48% for adjustable gastric banding, with follow-up ranging from six months to three years. The type 2 diabetes remission rate ranged from 27% to 75% for vertical sleeve gastrectomy versus 42% to 93% for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.85

The second review compared only vertical sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. It identified six RCTs and two non-randomized controlled studies with follow-up ranging from three months to two years.86 It found significantly greater improvements in BMI with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass than with vertical sleeve gastrectomy (mean difference in BMI 1.8, 0.5 to 3.2). It also found greater improvements in total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein-cholesterol, and insulin resistance with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus vertical sleeve gastrectomy.86 Longer term comparative effectiveness data on vertical sleeve gastrectomy are clearly needed. However, the effect of vertical sleeve gastrectomy on weight loss and comorbidity improvements seems to be somewhere between those of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and adjustable gastric banding.89

Complications of bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery is not without risks. Perioperative mortality for the average patient is low (<0.3%) and declining,88 but it varies greatly across subgroups, with perioperative mortality rates of 2.0% or higher in some patient populations.90 91 92 93 The incidence of complications in the first 30-180 days after surgery varies widely from 4% to 25% and depends on the definition of complication used, the type of bariatric procedure performed, the duration of follow-up, and individual patient characteristics.15 26 91 94 95

Findings from major studies

Among the 11 RCTs (796 patients) that have compared bariatric surgery with non-surgical care, rates of adverse events were higher in patients having surgery, but follow-up was limited to two years.21 No cardiovascular events or deaths were seen in either group, but the most common adverse events after surgery were iron deficiency anemia (15% with intestinal bypass operations) and reoperations (8%).21 These RCTs were not large enough to compare safety across procedure types, and most of the comparative data on complications come from larger observational studies.

The first phase of the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS-1) study prospectively assessed 30 day complications in 4776 severely obese patients who underwent a first bariatric surgical procedure (25% adjustable gastric banding, 62% laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 9% open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and 3% another procedure) between 2005 and 2007.91 The 30 day mortality rate was 0.3% for all procedures, with a major adverse outcome rate (predefined composite endpoint that included death, venous thromboembolism, reintervention (percutaneous, endoscopic, or operative), or failure to be discharged from the hospital in 30 days) of 4.1%. Major predictors of an increased risk of complications were a history of venous thromboembolism, a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea, impaired functional status (inability to walk 61 m; 1 m=3.28 ft), extreme BMI (≥60), and undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass by the open technique.91

Other large observational studies, such as SOS, have shown higher rates of complications, with 14.5% having at least one non-fatal complication over the first 90 days, including (in order of frequency) pulmonary complications, vomiting, wound infection, hemorrhage, and anastomotic leak.24 However, the SOS included mostly open and vertical banded gastroplasty procedures, which are rarely performed today. Nonetheless, the 90 day mortality rate in SOS was low at 0.25%.

A meta-analysis of 361 studies (97.7% non-randomized observational design) of 85 048 patients reported important differences in mortality up to 30 days across different laparoscopic bariatric procedures. It found 0.06% (0.01% to 0.11%) for adjustable gastric banding, 0.21% (0.00% to 0.48%) for vertical banded gastroplasty, 0.16% (0.09% to 0.23%) for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and 1.11% (0.00% to 2.70%) for biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch.90 The review also found significantly higher mortality with open procedures than with laparoscopic procedures.90 A clinically useful prognostic risk score has been developed and validated in 9382 patients to predict 90 day mortality after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery using five clinical characteristics: BMI 50 or more, male sex, hypertension, known risk factor for pulmonary embolism, and age 45 years or more.96 97 Patients with four to five of these characteristics are at higher risk of death (4.3%) by 90 days than those with none or one of these characteristics (0.26%).98

A systematic review of 15 RCTs of vertical sleeve gastrectomy found no deaths in 795 patients but a 9.2% mean complication rate (range 0-18%).85 In the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Network database, mortality 30 days after vertical sleeve gastrectomy was 0.11%, between that for adjustable gastric banding (0.05%) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (0.14%).89 The 30 day complication (morbidity) rate was 5.6% for vertical sleeve gastrectomy, 1.4% for adjustable gastric banding, and 5.9% for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Reoperation

A worrying trend is the relatively frequent rate of reoperation as a result of complications or insufficient weight loss (or both), especially for adjustable gastric banding. In a prospective cohort of 3227 patients who had undergone this procedure, 1116 (35%) patients underwent revisional procedures. These were performed because of proximal enlargement (26%), port and tubing problems (21%), and erosion (3.4%), with no acute band slippages specifically noted. The need for revision because of proximal enlargement of the gastric pouch decreased dramatically over 17 years as the surgical technique evolved, from 40% to 6.4%, and no acute slippages were specifically noted; however, the band was ultimately removed in 5.6% of all people.23

Other long term cohorts suggest that adjustable gastric banding removal rates may be as high as 50%.99 100 In the LABS-2 cohort study, the rate of revision or reoperation was higher for adjustable gastric banding than for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass at three years of follow-up.101 However, one systematic review of long term studies indicates that the rate of revisional surgery for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is similar to that for adjustable gastric banding (22% for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, range 8-38%; 26% for adjustable gastric banding, 8-60%).23 Many revisions are probably due to weight regain or failure to lose enough weight, but the specific cause for revision is often not indicated. The higher rates of reoperation with adjustable gastric banding may simply reflect the reversible nature of that surgical procedure compared with other relatively permanent procedures. Overall, more long term data are needed for all procedure types to categorize and understand the cause, nature, and severity of these complications.102

Psychosocial risks

Emerging data from observational studies suggest that some bariatric procedures introduce a greater long term risk of substance misuse disorders,103 104 105 suicide,106 and nutritional deficiencies.107 Pharmacokinetic studies indicate that the gastrointestinal anatomy after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and vertical sleeve gastrectomy leads to more rapid absorption of alcohol and marked increases in blood alcohol concentrations per dose. This may inadvertently increase the frequency of physiological binges and subsequent alcohol misuse disorder.108 109 110

In the SOS study, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was associated with increased alcohol consumption and an increase in alcohol misuse events (hazard ratio 4.9) over 20 years, but more than 90% of patients remained below the World Health Organization cut off for low risk alcohol consumption.105 Similarly, in the LABS-2 study, alcohol misuse disorders were more common in the second postoperative year (9.6%) in those undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass than at baseline (7.6%).103

The risk of suicide may be increased after bariatric surgery, although the cause is unclear. The Utah Mortality study showed a 58% increase in all non-disease causes of death in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass group compared with the matched control population, including a small but significant increase in suicides, accidental deaths, and poisonings.17 Similar findings were observed in the second Utah Obesity Study,67 and another observational study found that suicide rates in post-bariatric surgery patients were significantly higher than age and sex matched rates in the US.111 Given the paucity of data on preoperative psychological risk assessment and long term follow-up after bariatric surgery, rigorous research is needed to inform future practice guidelines and care standards in this area.

Nutritional deficiencies

Finally, evidence indicates that vitamin and mineral deficiencies, including deficiencies of calcium, vitamin D, iron, zinc, and copper, are common after bariatric surgery.107 Guidelines suggest screening patients for iron, vitamin B12, folic acid, and vitamin D deficiencies preoperatively. Patients should also be given daily nutritional supplementation postoperatively, including two adult multivitamin plus mineral supplements (each containing iron, folic acid, and thiamine), 1200 to 1500 mg of elemental calcium, at least 3000 IU of vitamin D, and vitamin B12 as needed. In addition, they should receive annual screening for specific deficiencies, including vitamin B12 (table 2).112 Insufficient evidence is available on optimal dietary and nutritional management after bariatric surgery, including how to manage some of the complications of surgery (such as chronic nausea and vomiting, hypoglycemia, anastomotic ulcers and strictures, and failed weight loss).

Table 2.

Recommended postoperative nutritional monitoring* 112

| Recommendation | AGB | VSG | RYGB | BPD-DS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone density (DXA) at 2 years | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 24 hour urinary calcium excretion at 6 months and annually | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Vitamin B12 annually (methylmalonic acid and homocysteine optional) then every 3-6 months if supplemented | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Folic acid (red blood cell folic acid optional), iron studies, vitamin D, intact parathyroid hormone | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Vitamin A initially and every 6-12 months thereafter | No | No | Optional | Yes |

| Copper, zinc, and selenium evaluation with specific findings | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Thiamine evaluation with specific findings | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

*AGB=adjustable gastric banding; BPD-DS=biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch; DXA=dual energy X ray absorptiometry; RYGB=Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; VSG=vertical sleeve gastrectomy.

Guideline supported indications for bariatric surgery and their limitations

The first guidelines for patient selection in bariatric surgery were established in 1991 at a National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference and were based on the limited literature available at that time.113 The initial selection criteria were a BMI of 40 or more, or a BMI of 35.0-39.9 with one or more obesity related comorbidity. In 2004, a Medicare Coverage Advisory Committee concluded that there was enough scientific evidence to support the coverage of open and laparoscopic bariatric surgery for patients who met the NIH criteria, and many private insurers and state Medicaid programs in the US soon followed suit.114

Currently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) covers open and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, and open and laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch for Medicare beneficiaries.115 In addition, in 2012 the CMS determined that local Medicare administrative contractors may individually determine coverage of laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy. In 2009, the CMS added a requirement that, for surgery to be reimbursed, it must be performed in “centers of excellence.”115 However, that requirement was removed in 2013 after the CMS determined that it did not improve health outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries. Although the 1991 NIH guidelines continue to be the most widely accepted standards for selecting patients for bariatric surgery,27 many experts have indicated a need to develop updated guidelines. This is because the criteria do not consider age; race or ethnicity; and, particularly for the lower BMI range, the severity of coexisting comorbidities.114 116

In 2007, a 50 member international, multidisciplinary Diabetes Surgery Summit Consensus Conference concluded that strictly BMI based criteria were inadequate for selecting candidates for diabetes surgery. It was proposed that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery could be considered in carefully selected moderately obese patients (BMI 30-35) with type 2 diabetes who were inadequately controlled by conventional medical and behavioral therapies.117 Consensus was not reached on the use of adjustable gastric banding or other bariatric procedures for this lower BMI population. These recommendations were endorsed by 21 professional and scientific organizations.112 117 118 However, in 2009, the CMS determined that bariatric procedures in patients with type 2 diabetes and a BMI less than 35 were “not reasonable and necessary” and therefore not covered.115 Despite the CMS coverage decision, in 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for adults with a BMI 30-35 and at least one obesity related health condition. The strength of the evidence base for the FDA’s decision has been questioned.119 Finally, in 2013, updated guidelines were released for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and non-surgical support of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery.112

Costs

The ability of bariatric surgery to reduce expenditures sufficiently to achieve cost savings continues to be debated.120 In two early observational studies, bariatric surgery seemed to be cost saving over a relatively short period of time.121 122 More recent observational studies,70 123 including an analysis of 29 820 Blue Cross Blue Shield Association enrollees, show no evidence of cost savings.124

In general, evidence suggests that outpatient costs, including pharmacy costs, are reduced after bariatric surgery. However, long term inpatient costs are increased or unchanged in patients who have undergone bariatric surgery compared with matched non-surgical patients, so no long term net cost benefit is seen. These results from observational cohorts are consistent with previous modeled cost effectiveness evaluations.19 20 125 Such evaluations have shown that bariatric procedures are likely to be cost effective, but not cost saving, compared with usual medical care or intensive lifestyle interventions for the average patient with severe obesity.

Shared decision making in the management of obesity

Given the considerable trade-offs between the risks, benefits, and uncertainties of the long term effects of bariatric procedures, the decision to undergo surgery should be based on a shared decision making process.126 127 The essential components of this process are clear communication of the clinician’s expert judgment, elicitation of the patient’s own values and preferences, and use of a patient decision aid that provides objective information about all clinically appropriate treatment options and encourages the patient to be meaningfully involved in decision making.128 One RCT showed that use of a video based patient decision aid for bariatric surgery led to greater improvements in patient knowledge, decisional conflict, and outcome expectancies than an educational booklet on bariatric surgery produced by the NIH.129

The shared decision making approach was endorsed at the 1991 NIH consensus conference on bariatric surgery.113 It recommended the following:

All patients should have an opportunity to explore with the physician any previously unconsidered treatment options and the advantages and disadvantages of each

-

The physician must fully discuss with the patient:

-The probable outcomes of the surgery

-The probable extent to which surgery will eliminate the patient’s problems

-The compliance that will be needed in the postoperative regimen

-The possible complications from the surgery, both short term and long term

The need for lifelong medical surveillance after surgery should be clear

With all of these considerations, the patient should be helped to arrive at a fully informed independent decision about his or her treatment.113

Looking ahead

Several important studies in the area of bariatric surgery are ongoing, including prospective and retrospective observational studies, and RCTs comparing contemporary procedures with non-surgical care of severely obese patients. The previously mentioned LABS-2 study will answer some questions about the comparative efficacy and safety of surgical procedures as well as the durability of weight loss and health improvements.130 Three year data were recently published, and seven year follow-up is planned.

A parallel Teen-LABS study will answer similar questions in adolescents with severe obesity undergoing bariatric surgery. Seven NIH funded RCTs of bariatric surgery are ongoing or have been recently completed, and at least 13 international RCTs are ongoing. In the next few years, these RCTs will probably provide more definitive answers to questions about the efficacy of bariatric procedures versus usual or intensive medical care or lifestyle interventions in the short term, especially for patients with type 2 diabetes and a BMI of 30.0-39.9. In addition, several of these RCTs are currently planning follow-up for five years or longer, so pooled longer term results will be available.

Ongoing observational studies, including the Utah Obesity Study, the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative, and cohorts in the Health Maintenance Organization Research Network and US Department of Veterans Affairs, are all likely to yield important information in the next five years on the comparative efficacy, safety, and costs of surgical and non-surgical care. They should also provide data on the durability of weight loss and health improvements, including the impact on incident microvascular disease and cancer.

Conclusion

High quality data from RCTs have clearly established that bariatric procedures are more effective than medical or lifestyle interventions for inducing weight loss and initial remission of type 2 diabetes, even in less obese patients with a BMI between 30.0 and 39.9.21 Although evidence from randomized trials does not go beyond two years, a few rigorous observational studies have shown encouraging results. These include an improvement in long term survival,17 18 a reduced risk of incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes,68 74 and more durable improvements in obesity related comorbidities among patients who have undergone bariatric surgery than among matched non-surgical controls.24 67

However, bariatric procedures are not without risks. The perioperative mortality for the average patient is low (<0.3%) and declining,90 but varies across subgroups, with perioperative mortality rates of 2.0% or higher in some patient populations.90 91 92 93 The incidence of complications after surgery varies from 4% to 25% and depends on the duration of follow-up, the definition of complication used, the type of bariatric procedure performed, and individual patient characteristics.15 26 91 94 95

Emerging data from observational studies also show that some procedures are associated with a greater long term risk of substance misuse disorders,103 104 105 suicide,106 and nutritional deficiencies.107 More research is needed to examine differences in long term outcomes across various procedures and heterogeneous patient populations, and to identify those who are most likely to benefit from surgical intervention. Given the persistent uncertainties about the long term trade-offs between the risks and benefits of bariatric surgery, the decision to undergo surgery should be based on a high quality shared decision making process.

Future research questions

What are the specific mechanisms of action responsible for weight loss and the type 2 diabetes response to bariatric surgical procedures?

What patient level factors can predict success (weight loss, health improvements, and cost savings) after bariatric surgical procedures?

Is bariatric surgery more effective than non-surgical care for the long term treatment of type 2 diabetes in people with less severe obesity (body mass index <35)?

On implementation of standardized reporting of complications across bariatric studies, what are the long term complication rates after different bariatric procedures?

What is the effect of bariatric surgery on long term microvascular and macrovascular event rates?

Contributors: Both authors planned, conducted, and prepared for publication all the review work described in this article; they both act as guarantors. Both authors also accept full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work. DEA reports grants from the National Institutes of Health, grants and non-financial support from Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, grants from Department of Veterans Affairs, and grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality outside the submitted work. APC reports other funding from J&J Ethicon Scientific, personal fees from J&J Ethicon Scientific, grants from NIH-NIDDK, grants from Covidien, grants from EndoGastric Solutions, and grants from Nutrisystem outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g3961

Related links

thebmj.com

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA 2012;307:491-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health England. Morbid obesity. 2014. www.noo.org.uk/NOO_about_obesity/Morbid_obesity.

- 3.Neovius M, Teixeira-Pinto A, Rasmussen F. Shift in the composition of obesity in young adult men in Sweden over a third of a century. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:832-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard NJ, Taylor AW, Gill TK, Chittleborough CR. Severe obesity: investigating the socio-demographics within the extremes of body mass index. Obes Res Clin Pract 2008;2:I-II. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg 2013;23:427-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA 1999;282:1523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013;309:71-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarwer DB, Lavery M, Spitzer JC. A review of the relationships between extreme obesity, quality of life, and sexual function. Obes Surg 2012;22:668-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arterburn DE, Maciejewski ML, Tsevat J. Impact of morbid obesity on medical expenditures in adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Narayan KM, Thompson TJ, Williamson DF. The relative contributions of different levels of overweight and obesity to the increased prevalence of diabetes in the United States: 1976-2004. Prev Med 2007;45:348-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma J, Xiao L. Obesity and depression in US women: results from the 2005-2006 national health and nutritional examination survey. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:347-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Z, Maglione M, Tu W, Mojica W, Arterburn D, Shugarman LR, et al. Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:532-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Look Ahead Research Group; Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Clark JM, Coday M, et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013;369:145-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moyer VA; Force US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for and management of obesity in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, Maglione M, Sugarman HJ, Livingston EH, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:547-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;292:1724-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, Halverson RC, Simper SC, Rosamond WD, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2007;357:753-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007;357:741-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Picot J, Jones J, Colquitt JL, Gospodarevskaya E, Loveman E, Baxter L, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2009;13:1-190, 215-357, iii-iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padwal R, Klarenbach S, Wiebe N, Hazel M, Birch D, Karmali S, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review of the clinical and economic evidence. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1183-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL, Kashyap SR, Schauer PR, Mingrone G, et al. Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2013;347:f5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maggard-Gibbons M, Maglione M, Livhits M, Ewing B, Maher AR, Hu J, et al. Bariatric surgery for weight loss and glycemic control in nonmorbidly obese adults with diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA 2013;309:2250-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien PE, MacDonald L, Anderson M, Brennan L, Brown WA. Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: fifteen-year follow-up of adjustable gastric banding and a systematic review of the bariatric surgical literature. Ann Surg 2013;257:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial—a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med 2013;273:219-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2008. Obes Surg 2009;19:1605-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Encinosa WE, Bernard DM, Du D, Steiner CA. Recent improvements in bariatric surgery outcomes. Med Care 2009;47:531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pi-Sunyer FX, Becker DM, Bouchard C, Carleton RA, Colditz GA, Dietz WH, et al. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. Government Printing Office, 1998. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.pdf.

- 28.Nguyen NT, Masoomi H, Magno CP, Nguyen XM, Laugenour K, Lane J. Trends in use of bariatric surgery, 2003-2008. J Am Coll Surgeons 2011;213:261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balsiger BM, Murr MM, Poggio JL, Sarr MG. Bariatric surgery. Surgery for weight control in patients with morbid obesity. Med Clin N Am 2000;84:477-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg S, Rivers P, Smith K, Homan W. Vertical banded gastroplasty: a treatment for morbid obesity. AORN journal 2000;72:988, 91-3, 95-1003; quiz 04-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugerman HJ. Bariatric surgery for severe obesity. J Assoc Acad Minor Phys 2001;12:129-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason EE, Ito C. Gastric bypass. Ann Surg 1969;170:329-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colquitt J, Clegg A, Sidhu M, Royle P. Surgery for morbid obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;2:CD003641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wittgrove AC, Clark GW. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y—500 patients: technique and results, with 3-60 month follow-up. Obes Surg 2000;10:233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Favretti F, Cadiere GB, Segato G, Himpens J, De Luca M, Busetto L, et al. Laparoscopic banding: selection and technique in 830 patients. Obes Surg 2002;12:385-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiner R, Blanco-Engert R, Weiner S, Matkowitz R, Schaefer L, Pomhoff I. Outcome after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding—8 years’ experience. Obes Surg 2003;13:427-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scopinaro N, Marinari GM, Camerini G. Laparoscopic standard biliopancreatic diversion: technique and preliminary results. Obes Surg 2002;12:362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baltasar A, Bou R, Miro J, Bengochea M, Serra C, Perez N. Laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch: technique and initial experience. Obes Surg 2002;12:245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paiva D, Bernardes L, Suretti L. Laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion: technique and initial results. Obes Surg 2002;12:358-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen NT, Nguyen B, Gebhart A, Hohmann S. Changes in the makeup of bariatric surgery: a national increase in use of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stefater MA, Wilson-Perez HE, Chambers AP, Sandoval DA, Seeley RJ. All bariatric surgeries are not created equal: insights from mechanistic comparisons. Endocr Rev 2012;33:595-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Basso N, Capoccia D, Rizzello M, Abbatini F, Mariani P, Maglio C, et al. First-phase insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity, ghrelin, GLP-1, and PYY changes 72 h after sleeve gastrectomy in obese diabetic patients: the gastric hypothesis. Surg Endosc 2011;25:3540-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, Alexandrides TK. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective, double blind study. Ann Surg 2008;247:401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langer FB, Reza Hoda MA, Bohdjalian A, Felberbauer FX, Zacherl J, Wenzl E, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and gastric banding: effects on plasma ghrelin levels. Obes Surg 2005;15:1024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Busetto L, Segato G, De Luca M, Foletto M, Pigozzo S, Favretti F, et al. High ghrelin concentration is not a predictor of less weight loss in morbidly obese women treated with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg 2006;16:1068-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tymitz K, Engel A, McDonough S, Hendy MP, Kerlakian G. Changes in ghrelin levels following bariatric surgery: review of the literature. Obes Surg 2011;21:125-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee H, Te C, Koshy S, Teixeira JA, Pi-Sunyer FX, Laferrere B. Does ghrelin really matter after bariatric surgery? Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006;2:538-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woelnerhanssen B, Peterli R, Steinert RE, Peters T, Borbely Y, Beglinger C. Effects of postbariatric surgery weight loss on adipokines and metabolic parameters: comparison of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy—a prospective randomized trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2011;7:561-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Korner J, Inabnet W, Conwell IM, Taveras C, Daud A, Olivero-Rivera L, et al. Differential effects of gastric bypass and banding on circulating gut hormone and leptin levels. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1553-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Roux CW, Aylwin SJ, Batterham RL, Borg CM, Coyle F, Prasad V, et al. Gut hormone profiles following bariatric surgery favor an anorectic state, facilitate weight loss, and improve metabolic parameters. Ann Surg 2006;243:108-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korner J, Bessler M, Inabnet W, Taveras C, Holst JJ. Exaggerated glucagon-like peptide-1 and blunted glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide secretion are associated with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass but not adjustable gastric banding. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:597-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubino F, Gagner M, Gentileschi P, Kini S, Fukuyama S, Feng J, et al. The early effect of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on hormones involved in body weight regulation and glucose metabolism. Ann Surg 2004;240:236-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kellum JM, Kuemmerle JF, O’Dorisio TM, Rayford P, Martin D, Engle K, et al. Gastrointestinal hormone responses to meals before and after gastric bypass and vertical banded gastroplasty. Ann Surg 1990;211:763-70; discussion 70-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen B, Peters T, Devaux N, Kern B, Christoffel-Courtin C, et al. Improvement in glucose metabolism after bariatric surgery: comparison of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg 2009;250:234-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liou AP, Paziuk M, Luevano JM Jr, Machineni S, Turnbaugh PJ, Kaplan LM. Conserved shifts in the gut microbiota due to gastric bypass reduce host weight and adiposity. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:178ra41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aron-Wisnewsky J, Dore J, Clement K. The importance of the gut microbiota after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;9:590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakatani H, Kasama K, Oshiro T, Watanabe M, Hirose H, Itoh H. Serum bile acid along with plasma incretins and serum high-molecular weight adiponectin levels are increased after bariatric surgery. Metabolism 2009;58:1400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stefater MA, Sandoval DA, Chambers AP, Wilson-Perez HE, Hofmann SM, Jandacek R, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy in rats improves postprandial lipid clearance by reducing intestinal triglyceride secretion. Gastroenterology 2011;141:939-49 e1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patti ME, Houten SM, Bianco AC, Bernier R, Larsen PR, Holst JJ, et al. Serum bile acids are higher in humans with prior gastric bypass: potential contribution to improved glucose and lipid metabolism. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1671-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ikramuddin S, Korner J, Lee WJ, Connett JE, Inabnet WB, Billington CJ, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs intensive medical management for the control of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia: the Diabetes Surgery Study randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309:2240-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Leccesi L, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1577-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP, Pothier CE, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1567-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dixon JB, O’Brien PE, Playfair J, Chapman L, Schachter LM, Skinner S, et al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:316-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Brien PE, Dixon JB, Laurie C, Skinner S, Proietto J, McNeil J, et al. Treatment of mild to moderate obesity with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding or an intensive medical program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:625-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Courcoulas AP, Goodpaster BH, Eagleton JK, Belle SH, Kalarchian MA, Lang W, et al. Surgical vs medical treatments for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2014; published online 4 Jun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Halperin F, Ding SA, Simonson DC, Panosian J, Goebel-Fabbri A, Wewalka M, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery or lifestyle with intensive medical management in patients with type 2 diabetes: feasibility and 1-year results of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2014; published online 4 Jun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, Kolotkin RL, LaMonte MJ, Pendleton RC, et al. Health benefits of gastric bypass surgery after 6 years. JAMA 2012;308:1122-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sjostrom L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, Sjostrom CD, Karason K, Wedel H, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA 2012;307:56-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2683-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neovius M, Narbro K, Keating C, Peltonen M, Sjoholm K, Agren G, et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA 2012;308:1132-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sjostrom L, Gummesson A, Sjostrom CD, Narbro K, Peltonen M, Wedel H, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on cancer incidence in obese patients in Sweden (Swedish Obese Subjects Study): a prospective, controlled intervention trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:653-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Karlsson J, Taft C, Ryden A, Sjostrom L, Sullivan M. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: the SOS intervention study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1248-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Romeo S, Maglio C, Burza MA, Pirazzi C, Sjoholm K, Jacobson P, et al. Cardiovascular events after bariatric surgery in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:2613-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carlsson LM, Peltonen M, Ahlin S, Anveden A, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Bariatric surgery and prevention of type 2 diabetes in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2012;367:695-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Flum DR, Dellinger EP. Impact of gastric bypass operation on survival: a population-based analysis. J Am Coll Surg 2004;199:543-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christou NV, Sampalis JS, Liberman M, Look D, Auger S, McLean AP, et al. Surgery decreases long-term mortality, morbidity, and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surg 2004;240:416-23; discussion 23-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maciejewski ML, Livingston EH, Smith VA, Kavee AL, Kahwati LC, Henderson WG, et al. Survival among high-risk patients after bariatric surgery. JAMA 2011;305:2419-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, Berk PD, Flum DR, Garcia L, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA 2013;310:2416-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kolotkin RL, Davidson LE, Crosby RD, Hunt SC, Adams TD. Six-year changes in health-related quality of life in gastric bypass patients versus obese comparison groups. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012;8:625-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nickel MK, Loew TH, Bachler E. Change in mental symptoms in extreme obesity patients after gastric banding, part II: six-year follow up. Int J Psychiatry Med 2007;37:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tice JA, Karliner L, Walsh J, Petersen AJ, Feldman MD. Gastric banding or bypass? A systematic review comparing the two most popular bariatric procedures. Am J Med 2008;121:885-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chakravarty PD, McLaughlin E, Whittaker D, Byrne E, Cowan E, Xu K, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) with other bariatric procedures; a systematic review of the randomised controlled trials. Surgeon 2012;10:172-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Padwal R, Klarenbach S, Wiebe N, Birch D, Karmali S, Manns B, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes Rev 2011;12:602-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Delaet D, Schauer D. Obesity in adults. Clin Evid (Online) 2011;2011:pii:0604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Guarino S, Cirocchi R, Scalercio V, Noya G, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy compared with other bariatric surgical procedures: a systematic review of randomized trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:816-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang X, Yang G, Wang W, Chen G, Yang H. A meta-analysis: to compare the clinical results between gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy for the obese patients. Obes Surg 2013;23:1001-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Angrisani L, Lorenzo M, Borrelli V. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 5-year results of a prospective randomized trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:127-32; discussion 32-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nguyen NT, Slone JA, Nguyen XM, Hartman JS, Hoyt DB. A prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for the treatment of morbid obesity: outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg 2009;250:631-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, Ko CY, Cohen ME, Merkow RP, et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg 2011;254:410-20; discussion 20-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Sledge I. Trends in mortality in bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery 2007;142:621-32; discussion 32-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium; Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, Wahed AS, Berk P, Chapman W, et al. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2009;361:445-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Flum DR, Salem L, Elrod JA, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L. Early mortality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA 2005;294:1903-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Livingston EH. Obesity, mortality, and bariatric surgery death rates. JAMA 2007;298:2406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Birkmeyer NJ, Dimick JB, Share D, Hawasli A, English WJ, Genaw J, et al. Hospital complication rates with bariatric surgery in Michigan. JAMA 2010;304:435-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Finks JF, Kole KL, Yenumula PR, English WJ, Krause KR, Carlin AM, et al. Predicting risk for serious complications with bariatric surgery: results from the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Ann Surg 2011;254:633-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.DeMaria EJ, Murr M, Byrne TK, Blackstone R, Grant JP, Budak A, et al. Validation of the obesity surgery mortality risk score in a multicenter study proves it stratifies mortality risk in patients undergoing gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg 2007;246:578-82; discussion 83-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.DeMaria EJ, Portenier D, Wolfe L. Obesity surgery mortality risk score: proposal for a clinically useful score to predict mortality risk in patients undergoing gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:134-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thomas H, Agrawal S. Systematic review of obesity surgery mortality risk score—preoperative risk stratification in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2012;22:1135-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Himpens J, Cadiere GB, Bazi M, Vouche M, Cadiere B, Dapri G. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg 2011;146:802-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lanthaler M, Aigner F, Kinzl J, Sieb M, Cakar-Beck F, Nehoda H. Long-term results and complications following adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg 2010;20:1078-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Courcoulas A, Christian NJ, Belle SH, Berk PD, Flum DR, Garcia L, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among patients with severe obesity. 2013;310:2416-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Courcoulas AP, Yanovski SZ, Bonds D, Eggerman TL, Horlick M, Staten MA, et al. Long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery: a National Institutes of Health symposium. JAMA Surg (forthcoming). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.King WC, Chen JY, Mitchell JE, Kalarchian MA, Steffen KJ, Engel SG, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA 2012;307:2516-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ostlund MP, Backman O, Marsk R, Stockeld D, Lagergren J, Rasmussen F, et al. Increased admission for alcohol dependence after gastric bypass surgery compared with restrictive bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg 2013;148:374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Svensson PA, Anveden A, Romeo S, Peltonen M, Ahlin S, Burza MA, et al. Alcohol consumption and alcohol problems after bariatric surgery in the Swedish Obese Subjects study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:2444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Peterhansel C, Petroff D, Klinitzke G, Kersting A, Wagner B. Risk of completed suicide after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2013;14:369-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gletsu-Miller N, Wright BN. Mineral malnutrition following bariatric surgery. Adv Nutr 2013;4:506-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hagedorn JC, Encarnacion B, Brat GA, Morton JM. Does gastric bypass alter alcohol metabolism? Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:543-8; discussion 48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Klockhoff H, Naslund I, Jones AW. Faster absorption of ethanol and higher peak concentration in women after gastric bypass surgery. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2002;54:587-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Maluenda F, Csendes A, De Aretxabala X, Poniachik J, Salvo K, Delgado I, et al. Alcohol absorption modification after a laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy due to obesity. Obes Surg 2010;20:744-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tindle HA, Omalu B, Courcoulas A, Marcus M, Hammers J, Kuller LH. Risk of suicide after long-term follow-up from bariatric surgery. Am J Med 2010;123:1036-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, Garvey WT, Hurley DL, McMahon MM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(suppl 1):S1-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Consensus development conference panel. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:956-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pories WJ, Dohm LG, Mansfield CJ. Beyond the BMI: the search for better guidelines for bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:865-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National coverage determination (NCD) for bariatric surgery for treatment of morbid obesity. 2009. www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/ncd-details.aspx?NCDId=57&bc=AgAAQAAAAAAA&ncdver=3. [PubMed]

- 116.Yermilov I, McGory ML, Shekelle PW, Ko CY, Maggard MA. Appropriateness criteria for bariatric surgery: beyond the NIH guidelines. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rubino F, Kaplan LM, Schauer PR, Cummings DE. The Diabetes Surgery Summit consensus conference: recommendations for the evaluation and use of gastrointestinal surgery to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg 2010;251:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Rubino F, Dixon JB. IDF’s view of bariatric surgery in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2011;378:108-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Arterburn D, Maggard MA. Revisiting the 2011 FDA decision on laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE. Cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery. JAMA 2013;310:742-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cremieux PY, Buchwald H, Shikora SA, Ghosh A, Yang HE, Buessing M. A study on the economic impact of bariatric surgery. Am J Manag Care 2008;14:589-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Finkelstein EA, Allaire BT, Burgess SM, Hale BC. Financial implications of coverage for laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2011;7:295-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Maciejewski ML, Livingston EH, Smith VA, Kahwati LC, Henderson WG, Arterburn DE. Health expenditures among high-risk patients after gastric bypass and matched controls. Arch Surg 2012;147:633-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Weiner JP, Goodwin SM, Chang HY, Bolen SD, Richards TM, Johns RA, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on health care costs of obese persons: a 6-year follow-up of surgical and comparison cohorts using health plan data. JAMA Surg 2013;148:555-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wang BC, Wong ES, Alfonso-Cristancho R, He H, Flum DR, Arterburn DE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgical procedures for the treatment of severe obesity. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15:253-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.O’Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Barry A. Modifying unwarranted variations in health care: shared decision making using patient decision aids. Health Affairs 2004; Suppl Variation:VAR63-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 127.Keirns CC, Goold SD. Patient-centered care and preference-sensitive decision making. JAMA 2009;302:1805-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Weinstein JN, Clay K, Morgan TS. Informed patient choice: patient-centered valuing of surgical risks and benefits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:726-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Arterburn DE, Westbrook EO, Bogart TA, Sepucha KR, Bock SN, Weppner WG. Randomized trial of a video-based patient decision aid for bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1669-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Belle SH, Berk PD, Chapman WH, Christian NJ, Courcoulas AP, Dakin GF, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 (LABS-2) study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:926-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]