Abstract

The field of the “epidemiology of longevity” has been expanding rapidly in recent years. Several long-term cohort studies have followed older adults long enough to identify the most long-lived and to define many factors that lead to a long life span. Very long-lived people such as centenarians have been examined using case-control study designs. Both cohort and case-control studies have been the subject of genome-wide association studies that have identified genetic variants associated with longevity. With growing recognition of the importance of rare variations, family studies of longevity will be useful. Most recently, exome and whole-genome sequencing, gene expression, and epigenetic studies have been undertaken to better define functional variation and regulation of the genome. In this review, we consider how these studies are leading to a deeper understanding of the underlying biologic pathways to longevity.

Keywords: aging, exome, genetics, genome, longevity

DEMOGRAPHY OF LONGEVITY

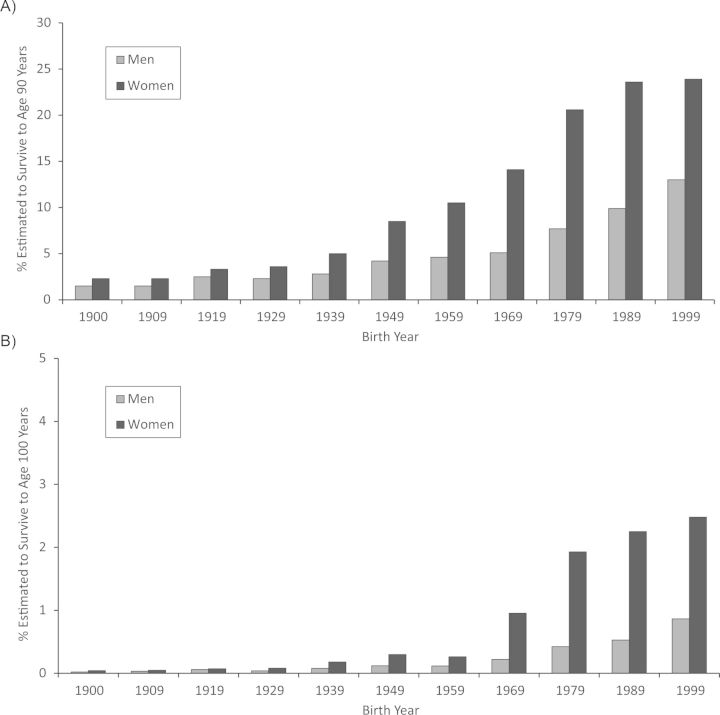

An epidemic is said to occur when new cases of a health outcome substantially exceed what is expected for a given time period. Longevity can be described as an epidemic, in that rates of survival to advanced old age have increased dramatically over the past century. There is no single accepted age threshold for longevity. The age of 85 years is often used to define the oldest old (1). However, with ongoing progress in improving the health of older adults, 2006–2008 survey data from the US Census Bureau demonstrated that the population aged ≥90 years, especially the subgroup aged ≥100 years, is now the largest growing group in the population aged ≥65 years (2). Of the 1910 birth cohort, fewer than 3% made it to age 90 years, whereas of those born in the year 2000, at least 15% of men and 20% of women are projected to reach age 90 years (3). Although the proportion of persons reaching old age has increased, the maximum recorded human life span has changed relatively little, with a few hundred individuals currently living to 110 years, fewer still approaching 120 years, and just 1 person, Jeanne Calment, making it to 122 years (4). Whether the maximal life span is fixed remains controversial (5).

These increases in life expectancy have not been uniform across ethnic and socioeconomic status groups (6). Persons achieving age ≥90 years remain overwhelmingly white, at 88.1%, with African Americans making up 7.6% and Asians 2.2% of the over-90 population. Approximately 4% of persons over 90 have reported Hispanic ethnicity (of any race) (2, 7). In 2006–2008, more than 60% of the population achieving age ≥90 years had at least a high school education, which is higher than expected for that birth cohort.

The older a person becomes, the more extreme is the longevity phenotype. Whereas age 85 years is beyond the average life expectancy, age 90 years is closer to the 90th percentile and age 100 years is beyond the 99th percentile for contemporary birth cohorts. The increases in the proportions of individuals in a given birth cohort projected to reach ages 90 and 100 years are shown in Figure 1 (3). The figure illustrates that the proportion of persons who survive to age 90 years has been increasing dramatically over the past century in both men and women. As a health outcome, reaching age 90 years is still relatively rare, and reaching age 100 years is an order of magnitude rarer. For example, fewer than 10% of women from the 1959 birth cohort are projected to reach age 90 years, and only 0.3% are projected to reach age 100 years. Another way of expressing this is that the likelihood of making it from birth to age 90 years is similar to the likelihood of making it from age 90 to 100 years. Thus, every year of survival into very old age is substantially more exceptional than the last. This has proven to be very important for genetic studies, as heritability of age at death is greater at more exceptional thresholds for longevity (8). Centenarian status is an easily understood and well-accepted criterion for longevity and is sufficiently rare yet practical for case-control studies. Lists of centenarians have been assembled in numerous countries around the world, including Italy, Germany, Japan, and the United States. Many prospective cohort studies focus on the achievement of less extreme ages, such as 85, 90, or 95 years, because few persons in any one cohort study have survived to these advanced ages.

Figure 1.

Survivorship to ages 90 years (A) and 100 years (B) for the 1900–1999 birth cohorts, by sex, United States. Data were obtained from Arias (3).

The rapid increase in life expectancy over the past century is largely environmental. Improvements in public health, nutrition, education, living conditions, and medicine have mitigated many causes of premature death, including infant and maternal mortality, accidents, infections (including epidemics), climate changes, and famine (5, 9). In the second half of the 20th century, gains in life expectancy were achieved for persons who had already reached old age. These gains were due largely to improvements in prevention and treatment of chronic disease in old age (10). Still, concern exists that, unless effective interventions are developed to address the obesity epidemic, continued gains in life expectancy could end, and younger generations could live less healthy and even shorter lives than their parents (11).

Among the exceptionally aged, at older and older ages, onset of disease and decline in physical and cognitive function occur later, such that for many supercentenarians (age 110–119 years), health span approaches life span (12). Thirty percent of centenarians, 56% of semi-supercentenarians, and nearly 70% of supercentenarians escape major age-related disease, including dementia. A further 53% of centenarians delay the onset of major age-related disease until age ≥80 years. Male centenarians have better physical and cognitive functional status than female centenarians, despite the greater probability of survival to extreme old age among women. Recent work from the Georgia Centenarian Study (13) provides an alternative model of successful aging focusing on psychosocial aspects of health, including components of subjective health (quality of life), economic well-being (access to services for basic needs), and happiness (emotional well-being). Remarkably, 47.5% of centenarians met the criteria for this alternative model of successful aging (13).

Data from both the New England Centenarian Study and the Okinawa Centenarian Study demonstrate that siblings of centenarians have a significantly greater likelihood of attaining age ≥90 years than their respective birth cohorts (15, 126). Similarly, according to genealogy databases in Utah (16) and Iceland (17), first-degree relatives of persons with excess longevity have twice the recurrence risk of longevity as controls. Offspring of centenarians also have significantly delayed onset of chronic conditions, including coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and stroke—by 5.0, 2.0, 8.5, and 8.5 years, respectively—as well as lower overall cardiovascular and cancer mortality than age-matched controls with at least 1 parent who died at average life expectancy (18, 19). Centenarian studies carried out both in the United States (among Ashkenazi Jews and in Georgia and New England) and internationally (in Okinawa, Japan, and other areas) have established biorepositories of clinical, biochemical, and genetic data and will continue to make important contributions to our understanding of longevity (20). Similar findings have been observed in the Leiden Longevity Study, in which nonagenarian siblings and their offspring have a lower prevalence of several age-related diseases and a lower mortality risk than sporadic nonagenarians (21). More recently, the Long Life Family Study, in which families were recruited for longevity, showed that probands and their offspring had more optimal levels of cardiovascular risk factors, higher physical function, and later onset of decline than similar-aged individuals participating in longitudinal cohort studies (22). Surprisingly, a recent study showed that Ashkenazi Jews achieving age ≥95 years and living independently did not appear to be different from the general population of the same birth cohort with regard to lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, and body mass index (weight (kg)/height (m)2) (23); this perhaps suggests that persons achieving exceptional longevity interact differently with the environment or that stronger genetic influences are in play.

BEHAVIORAL AND CARDIOVASCULAR RISK AND LONGEVITY

Numerous prospective population-based cohorts have been examined to describe the characteristics of persons with long-term survival. These studies also have defined the rates and risk factors for survival with intact health or function, such as survival free of chronic disease or survival with high levels of physical and cognitive function (Table 1). Survival with intact health and function has been termed “healthy aging,” “successful aging,” or “exceptional aging.” Together, these phenotypes have been called “exceptional survival” phenotypes and are thought to be important health outcomes in their own right but also intermediate phenotypes on the path to longevity. Within long-term cohort studies, the proportion of individuals surviving to age 100 years is too small to permit study of longevity per se, but continued follow-up of these cohorts will soon provide adequate sample sizes for study in a cohort design. It is also important to note that when centenarians are first enrolled for study only after having achieved this advanced age, they often have developed dementia and disability, making it difficult to assess them biologically. As ongoing cohorts are followed up for longevity, past data can be used to determine their prior rates of aging and resilience to disease and will provide important opportunities for birth cohort matching. The absence of these design features is a limitation of many case-control studies of centenarians.

Table 1.

Findings From Prospective Cohort Studies of Predictors of Longevity and Healthy Aging

| First Author, Year (Reference No.) | Study |

Duration of Follow-up, years | Exposure | Longevity Outcome | Predictors of Longevity Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | No. of Participants | Characteristics | |||||

| Guralnik, 1989 (109) | Alameda County Study | 841 | Persons born in 1895–1919; survivors aged 65–89 years at follow-up | 19 | Baseline variables | High levels of physical functioning (top 20%) | Race, higher family income, absence of hypertension, absence of smoking, normal weight, moderate alcohol intake, absence of arthritis and back pain |

| Strawbridge, 1996 (110) | Alameda County Study | 356 | Mean age = 72 years | 6 | Early-old-age risk factors | Successful aging: 35% (definition: minimal interruption of usual function, needing no assistance or having no difficulty with 13 activity/mobility measures, having little or no difficulty on 5 performance measures) | Higher income; high education; white ethnicity; absence of diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis, and hearing loss; and psychosocial predictors, including absence of depression, having close personal contacts, and often walking for exercise |

| Reed, 1998 (111) | Honolulu Heart Program/Honolulu-Asia Aging Study | 6,505 | Japanese-American men who were free of chronic disease | 28 | Midlife risk factors | Healthy aging: 19% (definition: surviving free of major disease and physical and cognitive impairment) | Age, low blood pressure, low serum glucose level, not smoking cigarettes, not being obese, high grip strength |

| Stamler, 1999 (25) | MRFIT and CHA | MRFIT: 72,144 men aged 35–39 years and 270,671 men aged 40–57 years CHA: 10,025 men aged 18–39 years, 7,490 men aged 40–59 years, and 6,229 women aged 40–59 years |

18 US cities; excluded persons with diabetes, myocardial infarction, or electrocardiographic abnormality | 16–22 | Low risk: cholesterol level <200 mg/dL, blood pressure <120/80 mm Hg, no smoking | Cause-specific death; estimated greater life expectancy | Low-risk persons: young adult men—MRFIT 9.9%, CHA 9.4%; middle-aged men—MRFIT 6.0%, CHA 4.8%; middle-aged women—6.8% Low-risk groups: markedly lower coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease death rates Estimated greater life expectancy for lower-risk groups than for others, ranging from 5.8 years and 6.0 years for CHA women and men aged 40–59 years, respectively, to 9.5 years for CHA men aged 18–39 years |

| Fried, 1998 (28) | Cardiovascular Health Study | 5,201 | Age ≥65 years, 57% female | 5 | Early-old-age disease, functional, personal factors | Mortality rate: 12% | Of 78 factors, 20 characteristics were significantly and independently associated with death, including: objective measures of subclinical disease and disease severity, age, male sex, relative poverty, lack of physical activity, smoking, low weight, and indicators of frailty and disability. Risk prediction score for quintiles of risk: 5-year mortality rate ranging from 1.9% for quintile 1 to 38.9% for quintile 5 |

| Burke, 2001 (32) | Cardiovascular Health Study | 3,342 | Age ≥65 years and disease-free (no cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or self-reported cancer) | 6.5 | Early-old-age risk factors | Healthy aging (definition: free of chronic disease); ranged from 79% of women initially aged 65–69 years to 48% of women initially aged ≥85 years and from 69% of men at ages 65–69 years to 34% of men at age ≥85 years | Physical activity; wine consumption (women); higher educational level; absence of smoking, obesity, and diabetes; higher high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; and lower blood pressure and C-reactive protein levels Subclinical disease measures: lower carotid intima-media thickness, absence of electrocardiographic abnormalities, higher ankle-brachial index |

| Newman, 2003 (33) | Cardiovascular Health Study | 2,932 | Age ≥65 years, “successfully” aged at study entry | 8 | Early-old-age risk factors | Successful aging: 48% at follow-up (definition: years free of chronic disease with intact physical and cognitive function) Years free of physical and cognitive impairment |

Successful aging: absence of diabetes and smoking, lower extent of subclinical cardiovascular disease, lower C-reactive protein level, and greater physical activity were associated with successful aging. Absence of subclinical disease corresponded to 6.5 more successful years in women and 5.6 more successful years in men. Years free of physical and cognitive impairment: women—absence of smoking, diabetes, greater exercise, minimal carotid wall thickness; men—low systolic blood pressure, higher ankle-brachial index |

| Terry, 2005 (27) | Framingham Heart Study | 2,531 (1,422 women) | Two examinations were conducted between ages 40 and 50 years | Midlife risk factors | Survival to age 85 years: 35.7% Survival to age 85 years free of morbidity: 22% |

Both outcomes: lower blood pressure and total cholesterol, absence of glucose intolerance, nonsmoking status, high educational level, female sex Probability of survival to age 85 years ranged from a high of 37% for men with no risk factors to 2% for men with all 5 risk factors and from 65% for women with no risk factors to 14% for women with all 5 risk factors. |

|

| Willcox, 2006 (14) | Honolulu Heart Program/ Honolulu-Asia Aging Study | 5,820 | Japanese-American men who were free of chronic disease; mean age = 54 years; birth cohorts 1900–1919 | 40 | Midlife risk factors | Overall survival to age 85 years: 42% Exceptional survival at age 85 years: 11% (definition: survival free of major disease with intact physical and cognitive function) |

Both outcomes: high handgrip strength; avoidance of overweight, hyperglycemia, hypertension, smoking, excessive alcohol intake Overall survival: marital status, high educational level Exceptional survival: avoidance of hypertriglyceridemia Probability of survival to oldest age ranged from a high of 69% for persons with no risk factors to a low of 22% for persons with ≥6 risk factors; probability of exceptional survival to age 85 years ranged from 55% for persons with no risk factors to 9% for persons with ≥6 risk factors. |

| Yates, 2008 (34) | Physicians' Health Study | 2,357 | Men; mean age = 72 years | 25 | Early-old-age risk factors | Survival to age ≥90 years: 41% Late-life function (Short Form 36 Health Survey) |

Survival to age 90 years: absence of smoking, diabetes, hypertension, regular exercise Late-life function: regular exercise, absence of smoking and overweight Decrement in mental function: smoking |

| Britton, 2008 (112) | Whitehall II Study | 4,140 men and 1,823 women | 20 London-based civil service departments; mean age = 44 years | 17 | Early-life factors and midlife social, behavioral, and psychosocial factors | Successful aging: 12.8% for men and 14.6% for women (definition: free of major disease, top tertile of physical and cognitive functioning) | Midlife socioeconomic position, height, education (men), not smoking, diet, exercise, alcohol (women), and work support (men) |

| Sun, 2009 (113) | Nurses' Health Study | 17,065 | Free of chronic disease at midlife (mean age = 50 years) | BMIa at midlife; BMI at age 18 years; weight change since age 18 years | Healthy survival to age 70 years: 9.9% (definition: lack of 11 chronic diseases, no cognitive or physical impairment) | Baseline BMI (obesity) and adult weight gain; the more weight gained from age 18 years to midlife, the less likely the participant was to attain healthy survival. | |

| Swindell, 2010 (114) | Study of Osteoporotic Fractures | 4,097 | Women aged 65–69 years | 19 | 377 measures screened in early old age; individual predictors and combinations | “Healthy aging”; long-term survival: 60% | Long-term survival, multiple outcomes: 13-variable model including age, physical function (number of step-ups completed in 10 seconds), current smoking, past smoking, diabetes, self-reported health, contrast sensitivity (vision), blood pressure, pulse, thiazide use, height loss, marital status, clinic indicator |

| Dutta, 2011 (115) | Established Populations for Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly | 2,890 (1,698 women) | 2 counties in Iowa; ages 65–85 years | 26 | Old-age risk factors | Extraordinary survivors: n = 253 (99 men) (definition: 10% of the longest survivors in each sex group (men aged ≥94 years; women aged ≥97 years)) | Earlier-life predictors: parental longevity, birth order (women only), BMI at age 50 years Predictors at age 65–85 years: self-reported health, fewer chronic diseases, better mobility and memory, positive attitude toward life |

| Baer, 2011 (26) | Nurses' Health Study | 50,112 | Mean age = 52.5 years | 18 | Lifestyle and dietary factors | Mortality: n = 4,893 deaths | Age, BMI at age 18 years, weight change, smoking, glycemic load, cholesterol, systolic blood pressure and use of blood pressure medication, diabetes, parental history of early myocardial infarction, time since menopause, physical activity, and intakes of nuts, polyunsaturated fat, and cereal fiber |

| Walter, 2012 (30) | The Rotterdam Study | 5,974 | Men and women; mean age 69 years; 59% women | 15 | 162 old-age risk factors, including genetic markers | Mortality: n = 3,174 deaths | 36 predictors (31 nongenetic, 5 genetic): age, sex, physiologic markers (such as blood pressure and BMI), prevalent diseases, general health, socioeconomic factors, lifestyle (including smoking), risk indicators assessed in blood and with imaging Genetic factors (including APOE, IGF1R, and WRN genotype) independently contributed to death but jointly contributed little to mortality risk prediction. |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CHA, Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry; MRFIT, Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial.

a Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

Several studies have emphasized the importance of cardiovascular risk factors for achieving long-term survival and exceptional survival. Each study defines the specific survival outcomes somewhat differently. Most investigators consider the most common fatal illnesses of heart disease, cancer, stroke, and chronic obstructive lung disease in defining healthy aging. To date, there has not been a careful comparison of these various outcomes within a cohort. Additionally, follow-up to date has not been long enough to demonstrate the precise correspondence between various definitions of exceptional survival phenotypes and longevity per se, though the life histories of centenarians validate the relevance of these outcomes for longevity (15, 24).

The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial and the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry Study permitted the examination of mortality rate and estimated life expectancy for young and middle-aged adults, primarily men, with low levels of total cholesterol and blood pressure and absence of smoking (25). The low-risk groups had markedly lower coronary and cardiovascular mortality rates than the others, as well as a greater life expectancy that ranged from 5.8 years for women aged 40–59 years to 9.5 years for men aged 18–39 years. The Nurses' Health Study followed more than 50,000 middle-aged nurses for up to 18 years and identified strong associations between risk factors, diet and lifestyle factors (smoking, physical activity, body mass index), and risk of death (26).

In the original Framingham Heart Study cohort, survival to age 85 years and morbidity-free survival to age 85 years were found to be related to more optimal levels of cardiovascular risk factors measured in midlife between the ages of 40 and 50 years (27). Survival to age 85 years decreased with increasing number of midlife risk factors (higher levels of blood pressure and total cholesterol, the presence of glucose intolerance, current cigarette smoking, and lower educational attainment), such that among men, 37% of persons with no risk factors survived to age 85 years as compared with 2% of persons with all 5 risk factors; in women, 65% of those with no risk factors and 14% of those with all 5 risk factors survived to age 85 years. In the Honolulu Heart Program/Honolulu-Asia Aging Study, Willcox et al. (14) reported similar findings among nearly 6,000 middle-aged Japanese-American men who were free of chronic disease and functional limitation at baseline and were followed for up to 40 years. The probability of survival and exceptional survival, defined as survival free of major disease with intact physical and cognitive function, to age 85 years was a function of the cumulative number of midlife risk factors, including high handgrip strength and avoidance of overweight, hyperglycemia, hypertension, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption. The probability of exceptional survival to old age was as high as 55% in men with no risk factors and as low as 9% in men with 6 or more risk factors.

Risk factors measured in early old age continue to predict longevity in later old age, though the relative risk tends to diminish, especially for cholesterol and body weight. In the Cardiovascular Health Study, 5,201 men and women aged ≥65 years were followed for 5 years to determine the sociodemographic, lifestyle, risk factor, disease, and functional predictors of death (28). Of 78 characteristics examined, 20 were significantly and independently associated with death. The strongest predictors of death reflected objective measures of subclinical disease and disease severity, with additional predictors including age, sex, cigarette smoking, low levels of physical activity, relative poverty, and indicators of frailty and disability. A risk prediction score demonstrated a steep gradient of increasing mortality with increasing risk quintile, ranging from 1.9% in the lowest risk quintile to 38.9% in the highest.

Long-term, 16-year survival was also examined in the Cardiovascular Health Study but from the perspective of investigating the unique and shared risk factors for specific categories of causes of death (29). For total deaths and for cardiovascular deaths, cardiovascular risk factors were most prominent, including cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and measures of the extent of vascular disease on noninvasive testing. Notably, the higher rates of mortality and cardiovascular mortality in men were not explained by their higher levels of cardiovascular risk factors. In other words, although men had higher levels of smoking, cholesterol, and blood pressure, the risk ratio for men versus women was not attenuated with adjustment for their higher risk. Few factors were common risk factors for all causes of death, and none were as strong as age itself. Dysfunction of 2 organ systems (the kidney and lung), lower weight, and markers of inflammation and cognitive function were associated with death from more than one cause.

Long-term mortality was also examined in the Rotterdam Study among more than 5,000 participants who were aged ≥55 years at enrollment and were followed up for a median of 15 years, with a focus on genetic markers in addition to lifestyle, risk factors, and prevalent diseases (30). Although genetic factors independently contributed to mortality risk, the joint contribution to risk prediction was modest. Beyond age and sex, physiologic parameters, prevalent disease, lifestyle, general health, and socioeconomic factors contributed to mortality risk (30). Six longitudinal studies of older persons from Europe and Israel found similar predictors of death across countries, including age, male sex, smoking, prevalent diseases, and disability (31).

Survival free of chronic disease has been investigated among Cardiovascular Health Study participants who were free of chronic disease at enrollment. Healthy aging after an average of 6.5 years of follow-up was common, with rates ranging from 79% of women initially aged 65–69 years to 48% of women initially aged ≥85 years and from 69% of men initially aged 65–69 years to 34% of men initially aged ≥85 years (32). In addition to cardiovascular risk factors, subclinical disease measures, including absence of electrocardiographic abnormalities, higher ankle-brachial index, and lower carotid intima-medial thickness, were important determinants of survival free of chronic disease. Early-old-age risk factors were also found to predict years free of chronic disease with intact physical and cognitive function (successful aging). The absence of subclinical cardiovascular disease in early old age corresponded to 6.5 more successful years of living in women and 5.6 more successful years of living in men (33). In the Physicians' Health Study, the modifiable risk factors of smoking, blood pressure, physical activity, and obesity, measured in men in early old age (mean age 72 years), were associated with longevity (defined as survival to age ≥90 years) and late-life function (34). Regular exercise was associated with significantly better late-life physical function and being overweight was associated with worse physical function, whereas smoking was associated with impairments in both physical and cognitive function. In the Iowa Established Populations for Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly, extraordinary survivors, defined as the 10% with the longest survival in each sex group, had fewer established cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, at older ages (65–85 years), extraordinary survivors reported excellent health, fewer chronic diseases, and better mobility and memory.

Taken together, these prospective studies demonstrate the importance of engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors across the adult life span to achieving longevity and maintaining late-life function (115). These factors are important behavioral and environmental candidates that will need to be considered to understand gene-by-behavior and gene-by-environment interactions in achieving longevity.

Attention recently has turned to applying new insights in the biology of aging to epidemiologic studies. Once cardiovascular and lifestyle factors are accounted for, age remains a strong risk factor for death (29). Biomarkers of aging potentially could explain the risk of chronologic age. Markers from pathways that influence longevity in animal models are of interest in understanding the role of biologic aging in longevity (35). Caloric restriction is the most robust manipulation that influences longevity in lower organisms, and it appears to influence several pathways, including oxidative stress, markers of inflammation, growth hormone, and insulin signaling. Genetic mutations that influence longevity in the worm and mouse models are found largely in this pathway (36, 37). Currently, levels of inflammation markers such as interleukin-6 (38), oxidative damage (oxidized low-density lipoprotein), glycosylation (carboxymethyl-lysine) (39), and levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (40) are being examined for their associations with earlier death. These markers are reviewed elsewhere (35, 40). More work is needed to understand which of them is most important in influencing longevity versus indicating risk of earlier onset of disease.

REPRODUCTIVE PHENOTYPES AND LONGEVITY

The female advantage for longevity has been apparent from at least the late 1800s (41). The female advantage is well known to be present from the time of conception, with greater loss of males during pregnancy and throughout the life span. The reasons for this are not well understood (42). Women have better survival at every age and thus appear to be more robust rather than to age more slowly (41). Currently, a female life expectancy advantage is nearly universal, except in some southern Asian and sub-Saharan African societies where cultural factors (low female social status and stronger preference for male offspring) or a differential impact of the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome pandemic favor men (43). In one unique long-lived population in Sardinia, it seems that men achieve longevity as often as do women. Careful reconstruction and follow-up of birth cohorts from 1876–1921 show that this is not a demographic artifact, although the environmental and genetic factors that might explain it have yet to be discovered (44).

Potential hypotheses for the female advantage include unmeasured confounding in studies of mortality rate differences between men and women, antagonistically pleiotropic effects of male hormones, and protective effects of the estrogen and reproductive process. In a very comprehensive study of mortality risk in older men and women, there was little attenuation of the sex difference by potential confounders, and it is difficult to think of additional unmeasured confounders that might explain it (29). The absence of a second X chromosome in men is thought to allow the expression of deleterious genetic variation that would be recessive in females. Differences in the growth hormone and insulin signaling pathways or in oxidative stress also could be important. Differences in immune function that allow a genetically distinct pregnancy to continue are also hypothesized to play a role. To date, there is no strong support for any one mechanism.

In epidemiologic studies, the timing of menarche and menopause have been associated with longevity and important age-related diseases. These findings are supported by numerous studies in animal models (45). In several cohort studies carried out in the United States, Europe, and Australia, early menarche was associated with a higher risk of breast cancer, cardiovascular disease and its risk factors, and total mortality (46–53). For example, women who recalled undergoing menarche prior to age 12 years were 30% more likely to die than those with later menarche (49). Early death was driven predominantly by higher rates of cardiovascular death. There also could be a higher risk of diabetes (50, 52). Mechanisms for this association might include a longer lifetime exposure to estrogen, but it also could be due to the risk factors for early menarche, including greater weight gain in childhood and socioeconomic factors (54). Associations between menarche, weight gain, and possibly higher insulin-like growth factor 1 (55) in early life suggest a link between menarche and the insulin signaling pathway, which supports the idea that age at menarche might be a useful phenotype in the study of longevity. Furthermore, recent work in inbred mice demonstrated a link between earlier sexual maturation and life span that could be genetically co-regulated through the insulin-like growth factor 1 pathway (56). Although early menarche is a risk factor for earlier disease onset, it cannot be assumed that later menarche is especially protective, inasmuch as current studies have not specifically tested this.

Later menopause is also related to longer life. In a study of 19,731 older Norwegian women, older age at natural menopause was associated with a lower risk of death (57). In a cohort of 12,134 Dutch women, this same association was found, was related predominantly to lower risk of cardiovascular disease, and was minimally offset by a higher risk of uterine and ovarian cancer (58). Notably, the age-adjusted mortality rate decreased by 2% with each increasing year of menopausal age. Another study of 68,154 American women found that early menopause was associated with several causes of death, including predominantly coronary heart disease death but also respiratory disease, genitourinary disease, and external causes of death (59). Similar associations have been reported for other cohort studies in the United States (60), as well as in Japan (61, 62) and South Korea (63).

Reproductive aging phenotypes could serve as important endophenotypes for genetic studies of longevity. Evolutionary theories of aging support a tradeoff between fertility and survival (64), with associations between reproduction and life span being observed in both animal models (37, 65, 66) and humans. Centenarian women, for example, are more likely to have borne children late in life than women who died at an earlier age (67, 68). Furthermore, according to data from historical population databases, late ability to reproduce is associated with improved survival not only in the women (69) but also in their male family members (70), which supports the hypothesis that late fertility and slower somatic aging might share underlying genetic determinants.

GENETIC FACTORS

Genetic studies of longevity and other aging phenotypes, including healthy aging and reproductive phenotypes, were recently reviewed by Murabito et al. (71). Studies of longevity have included case-control designs and cohort study designs. The genotypes of centenarians and supercentenarians have been compared with those of control groups, such as the offspring of persons not reaching exceptional old age or general population controls. A strength of these studies is that the more extreme age of 100 years is likely to have a greater genetic basis, but a limitation is the lack of a birth cohort-matched comparison. The life experience of today's centenarians preceded the influenza epidemic of 1917 and the antibiotic era. Survival through their childhood years might have depended on a different set of genetic advantages than would be true for more recent birth cohorts (72). Long-term cohort studies have followed enough individuals over many years to be able to examine the longest-term survivors in comparison with persons in those same cohorts who did not reach old age. The latter study design offers better control for environmental differences, but it is limited in that the total number of persons in these cohorts who have reached advanced old age is not large. For example, in the 4 cohorts participating in a recent analysis of the CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology) Consortium (73), only 1,800-plus had reached age ≥90 years at the time of the analysis. With more follow-up and expansion of the CHARGE Consortium to include additional cohorts with long-lived participants with genotyping, many more will have had the opportunity to reach age ≥90 years, providing an opportunity to update these analyses.

The findings from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of longevity and the candidate gene studies have implicated several genes and pathways (Table 2). To date, findings have been replicated in multiple studies for only a few genes: the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE) and the forkhead box O3A gene (FOXO3A) in the insulin signaling pathway. Genetic variants in the FOXO3A gene were selected a priori for study with human longevity because the gene lies in the insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling pathway, a key evolutionarily conserved biologic pathway known to extend life span in animal models. In a case-control study nested within the Honolulu Heart Program/Honolulu-Asia Aging Study, men of Japanese descent who lived to age ≥95 years (longevity) were compared with men who died before age 81 years (average age) (74). A strong and significant association between longevity and FOXO3A was detected; men with 2 copies of the minor allele of the genetic variant had nearly 3 times the odds of living to nearly 100 years of age. The FOXO3A-longevity association has since been extended to samples that include women and has been replicated in diverse ethnic groups (75–79). The exact biologic mechanism mediating the association remains to be elucidated but could be related to oxidative stress, maintenance of insulin sensitivity, and cell-cycle progression. Interestingly, FOXO3A has not been identified in GWAS of longevity, an approach that is hypothesis-free and unconstrained by genetic variants chosen a priori.

Table 2.

Genetic Factors Associated With Longevity in Association Studies

| First Author, Year (Reference No.) | Sample | Gene | SNP/Variant | Study Design | Replication/ Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schachter, 1994 (81) | French centenarians | ApoE | ɛ4 allele | Candidate gene | Danish centenarians (116) Danish 1905 cohort (82, 117)/subsequent studies (118) |

| Barzilai, 2003 (88) | Ashkenazi Jews; mean age = 98 years | CETP | I405V | Candidate gene | No replication in Italian centenarian sample (119); subsequent supportive evidence in Danish and German oldest old (120) |

| Koropatnick, 2008 (89) | Men of Japanese descent; mean age = 78 years | CETP | Int 14A | Candidate gene | |

| Willcox, 2008 (74) | Men of Japanese descent; age ≥95 years | FOXO3A | rs2802292 | Candidate gene | German centenarian study (76) Southern Italian Centenarian Study (75) Han Chinese study of centenarians (77) Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, Cardiovascular Health Study, study of Ashkenazi Jewish centenarians (79) Danish 1905 cohort (78)/subsequent publications |

| Arking, 2005 (121) | Ashkenazi Jews aged >95 years; controls were unrelated persons aged 51–94 years | KL | KL-VS | Candidate gene | Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses demonstrate a longevity advantage Concordance with previous data in Czechs aged ≥79 years |

| Atzmon, 2006 (122) | Ashkenazi Jewish centenarians and their offspring and age-matched Ashkenazi controls | APOC3 | rs2542052 | Candidate gene | |

| Suh, 2008 (123) | Ashkenazi Jewish centenarians and their offspring and offspring-matched controls | IGF1R | Nonsynonymous mutations: 244G>A and 1355G>A | Candidate gene | Female offspring of centenarians demonstrated higher insulin-like growth factor 1 levels than controls; this finding was sex-specific and associated with shorter height. |

| Pawlikowska, 2009 (79) | Study of Osteoporotic Fractures; women aged ≥92 years, average life-span controls defined as age <79 years | AKT1 | rs3803384 | Candidate gene | Replicated in meta-analysis including the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, the Cardiovascular Health Study, and Ashkenazi Jewish centenarians (79) |

| Nebel, 2009 (92) | German centenarians | EXO1 | rs1776180 | Candidate gene | Discovery finding was identified in female centenarians and replicated in a sample of female French centenarians |

| Conneely, 2012 (93) | Long-lived US Caucasians aged ≥95 years and younger controls | LMNA | Haplotype of 4 SNPs | Candidate gene meta-analysis | 4 independent replication samples (n = 3,619) of long-lived individuals and controls: New England Centenarian Study, Southern Italian Centenarian Study, France, Einstein Ashkenazi Longevity Study |

| Newman, 2010 (124) | CHARGE cohort members aged ≥90 years | MINPPI | rs9664222 | GWAS meta-analysis with replication | Leiden Longevity Study, Danish 1905 cohort, younger Danish twins |

| Nebel, 2011 (83) | Germans; mean age = 100 years | APOC1 (explained by linkage disequilibrium with ApoE) | rs4420638 | GWAS with replication | Long-lived Germans |

| Deelen, 2011 (80) | Leiden Longevity Study | TOMM40 (tagging ApoE) | rs2075650 | GWAS with replication | Leiden 85+ Study, Rotterdam Study, Danish 1905 cohort |

| Malovini, 2011 (125) | Southern Italians | CAMKIV | rs10491334 | GWAS with replication | Southern Italians |

| Walter, 2011 (127) | Time to death in CHARGE cohortsa | OTOL1 | rs1425609 | GWAS meta-analysis with replication | 4 European cohorts |

| Sebastiani, 2012 (84) | New England centenarians (median age at death, 104 years) and genetically matched healthy controls | TOMM40/ApoE | rs2075650 | GWAS (single-SNP analysis) | Independent replication set that included 253 and 60 centenarians and more than 3,000 population controls |

| Sebastiani, 2009 (94) | New England Centenarian Study; men aged 90–119 years | ADARB1 and ADARB2 | SNPs | Candidate genes in RNA editing pathway selected from genome-wide screening with pooled DNA | Replication in 3 independent centenarian samples from different backgrounds: Southern Italians, Ashkenazi Jews, and Japanese in same publication |

Abbreviations: CHARGE, Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology; GWAS, genome-wide association study; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

a Studies included: Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik Study; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study; Cardiovascular Health Study; Framingham Heart Study; Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study; Rotterdam Study; Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; Invecchiare in Chianti Study; and Study of Health in Pomerania.

GWAS for longevity conducted in nonagenarians and population controls identified 1 genome-wide significant single-nucleotide polymorphism, rs2075650, in the TOMM40 gene (translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 homolog (yeast)) close to APOE, which was associated with a nearly 30% decreased probability of reaching age 90 years (80). This association was not independent of the single-nucleotide polymorphism defining the APOE ɛ4 isoform. The APOE-longevity association had been identified previously in candidate gene association studies (81, 82) and has since been confirmed in additional GWAS of long-lived samples, including centenarians (83, 84). The exact mechanisms underlying the longevity association are unknown; however, rs2075650 was associated with metabolic phenotypes (lipids and C-reactive protein) and insulin-like growth factor 1 levels in women in the initial GWAS report (80). These findings are consistent with what is known about rs2075650/TOMM40 and the APOE ɛ4 isoform from GWAS of cardiovascular risk factors and Alzheimer's disease (85–87). It is unclear whether the association is mediated through increased mortality risk, increased risk of age-related diseases (cardiovascular disease, dementia, and Alzheimer's disease), perturbed metabolic pathways, or other mechanisms.

Other notable findings relate to pathways in lipid metabolism, DNA repair, and RNA regulation. The cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene (CETP) was found to be related to a phenotype of larger high-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein particle sizes and lower rates of hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease in a case-control study of 213 Ashkenazi Jewish probands with exceptional longevity and their offspring (n = 216) (88). The CETP gene may also increase the odds of healthy aging in older Japanese-American men participating in the Honolulu Heart Program (89). However, the genetic variants in the CETP gene involved in the two studies were different. Some of the lack of replication across studies could be due to population-specific findings—some variants are very rare or might not exist in some populations. Cardiovascular protection is essential for longevity, because cardiovascular disease is the primary cause of mortality in older adults. However, it is interesting to note that deleterious alleles identified in recent GWAS are no less common in familial cases of longevity than in sporadic cases (90).

In a recent meta-analysis of all compiled human GWAS conducted to examine broadly the genetics of resistance to age-related disease, Jeck et al. (91) identified 10 locations (“bins”) across the genome that were enriched for susceptibility to multiple age-related diseases. Two of the locations were highly significant, including the chromosome 9p21 locus previously found to be associated with longevity and several age-related diseases, including atherosclerosis (myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease), type 2 diabetes, and cancer. Moreover, all 10 genomic locations were linked to genes associated with cellular senescence or inflammation pathways, which suggests that these biologic pathways influence the human health span. Many progeroid models are characterized by deficits in DNA repair, making genes in DNA repair pathways strong candidates for longevity genes (92). Of interest, several single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the lamin A/C gene (LMNA) identified as causing Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome have been genotyped in long-lived samples and younger controls to explore the effect on normal aging (93). According to data from the New England Centenarian Study, the Southern Italian Centenarian Study, a long-lived sample from France, and the Einstein Ashkenazi Longevity Study, it appears that variants in the LMNA gene could play a role in the human life span. In addition to pointing to RNA editing genes (94), Sebastiani et al. (84) show that it is important to consider joint effects of multiple common variants in a region.

Other findings from previous studies, as reviewed in 2006 by Christensen et al. (82) and in 2010 by Barzilai et al. (95), have not been replicated in recent GWAS or have been inconsistent, but they also represent important candidate pathways, including the growth hormone axis, insulin signaling/insulin-like growth factor 1, and DNA repair.

Interestingly, a GWAS of age at natural menopause identified 17 genetic variants (96), many involved in biologic pathways of DNA replication and repair and immune function that are also pathways important to aging and longevity. One of the DNA repair genes identified in the menopause GWAS, exonuclease 1 (EXO1), was previously reported to be associated with prolonged life expectancy in female centenarians (92). Examination of other exceptional survival phenotypes could speed discovery of longevity genes. In the Cardiovascular Health Study, Newman et al. (97) developed a physiologic index of aging by combining information across 5 major organ systems known to predict death and disability. The index was constructed with the use of noninvasive testing from the vascular, lung, brain, kidney, and metabolic systems and resulted in a wide range of values, from 0 (all systems normal) to 10 (clinical disease). The physiologic index was able to identify a very low-risk group of healthy agers. Lack of decline in an organ system might be another important endophenotype of longevity. Endophenotypes are defined as important intermediate components of the phenotype of interest. In a longitudinal cohort study of more than 2,700 participants with a mean age of 74 years at baseline and 80 years at follow-up, participants who maintained cognitive function had a lower mortality risk and less decline in physical function (98). Similarly, in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, successful skeletal aging, defined as maintenance of bone mineral density for up to 15 years, was a marker of longevity (99). Development of endophenotypes of preservation of function across multiple systems likely will be needed to define health with intact physical and cognitive function into old age (100).

Experience with GWAS for complex traits suggests that common variants explain only a small fraction of the estimated 20%–35% heritability of longevity. It is possible that it is the joint effect of multiple common variants that explains the effects of genotypes on phenotypes (84). Alternatively or additionally, rare variants, with frequencies of less than 0.5%, could explain some of this missing heritability. Several projects are under way to characterize rare variants in existing cohorts and in family studies. The whole genomes of 2 supercentenarians (>110 years of age) were recently sequenced. The supercentenarians were shown to have genomes comparable to published human genomes, did not carry most of the longevity-enabling variants identified in the literature to date, and had comparable rates of disease variants, but they also had a number of novel variations that will need to be further examined for longevity associations (128). Other sequencing projects have now shown us that the cumulative total number of rare variations is surprisingly high (101), but individual variation is difficult to distinguish from genotyping error because individual variants that are very rare in the population might appear only once in even a very large sample of unrelated individuals. Family samples make it easier to statistically characterize and distinguish such very rare variants from genotyping error, because they will tend to be found in multiple members of a given lineage/pedigree. Family studies such as the Long Life Family Study (22), which is under way in the United States and Denmark, likely will complement the ongoing efforts in sequencing in large cohort studies.

Additional genomics projects are under way to examine the role of gene expression in human aging and longevity. The Ashkenazi Jewish Centenarian Study used microRNA profiling in 3 centenarians and 3 controls and identified enrichment of functional pathways involved in cell metabolism, cell cycle, cell signaling, and cell differentiation (102). Although very few individuals were studied, the differences were very large and were significant with adjustment for multiple comparisons. Investigators in several longitudinal cohort studies are measuring gene expression by using commercially available arrays that could uncover a variety of age-associated biologic pathways that ultimately will provide insights into aging and longevity. For example, in the Invecchiare in Chianti Study and the San Antonio Family Heart Study, expression of genes in the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, a pathway associated with life span in animal models, was associated with advancing age (103). Furthermore, the expression pattern in humans was generally consistent with mTOR inhibition interventions associated with increased life span in animal models.

It also has become increasingly apparent that the control of gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms could play a role in understanding heritability. In the Dutch Famine Studies, investigators assessed the propensity for diabetes and heart disease among children of women subjected to famine during pregnancy during World War II in the Netherlands. These children were more likely to develop heart disease and diabetes, which suggests preprogramming in utero (104). Studies of global DNA methylation patterns in adults have not shown any overall differences in famine exposure births compared with controls (105), but one very small study did find that the insulin-like growth factor 2 gene (IGF2) was differently methylated in persons with periconceptional exposure to famine (106, 107). These studies illustrate the increasing complexity of genetic studies, with heritability varying with gene-environment interactions and the epigenetics of environmental exposure being heritable.

Together, these epidemiologic studies of the risk and protective factors for longevity have come into alignment with the well-established evidence in model systems that the aging process is linked to growth and metabolism. Mutations in homologues of the insulin signaling pathway often are linked to longevity phenotypes in diverse species, including yeast, worms, and flies (37). These same pathways are involved in the caloric restriction model, which produces life extension in these various organisms, as well as in mammals (36). Decades of archived data on Okinawans demonstrated low calorie intake, lifelong low body mass index, a low mortality rate from age-related disease, and survival patterns consistent with extended mean and maximum life span, which lends epidemiologic support to calorie restriction as a contributor to healthy aging in humans (108). The mechanism of the benefit of caloric restriction appears to involve a reduction in growth factor signaling in response to nutrient deprivation. These findings are controversial, as it is clear from existing studies that caloric restriction is not essential for longevity and that the longest-lived older adults often have body mass indices in the overweight range (i.e., 25–30).

CONCLUSION

Epidemiologic studies of longevity are likely to have enormous implications for aging and public health. The aging process itself is clearly linked to lifelong behaviors. Current efforts to reduce disparities in known risk factors can have a great impact on continued improvements in life expectancy and healthy life span. Longevity seems to be heritable yet plastic. The heritable component of longevity and research in animal models have revealed key pathways that can be targeted to decrease the risk of late-life chronic disease and increase disease-free and disability-free survival. These efforts likely will translate into lower morbidity and improved physical and cognitive function in old age—worthy goals for longevity research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Epidemiology, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Anne B. Newman); Division of Geriatric Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Anne B. Newman); Section of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts (Joanne M. Murabito); and Framingham Heart Study, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Framingham, Massachusetts (Joanne M. Murabito).

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U01 AG023744, R01 AG023629 (Anne B. Newman), and R01 AG029451 (Joanne M. Murabito).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Suzman R, Riley MW. Introducing the “oldest old. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1985;63(2):177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He W, Muenchrath MN. 90+ in the United States: 2006–2008. (American Community Survey Reports, no. ACS-17) Washington, DC: US GPO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias E. United States life tables, 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002;51(3):1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robine JM, Allard M. The oldest human. Science. 1998;279(5358):1834–1835. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1831h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oeppen J, Vaupel JW. Broken limits to life expectancy. Science. 2002;296(5570):1029–1031. doi: 10.1126/science.1069675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2012: Key Indicators of Well-Being. Washington, DC: US GPO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hjelmborg JVB, Iachine I, Skytthe A, et al. Genetic influence on human lifespan and longevity. Hum Genet. 2006;119(3):312–321. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0144-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilmoth JR. The future of human longevity: a demographer's perspective. Science. 1998;280(5362):395–397. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried L. What are the roles of public health in an aging society? In. In: Prohaska TR, Anderson LA, Binstock RH, editors. Public Health for an Aging Society. 1st. Vol. 26. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1138–1145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr043743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen SL, Sebastiani P, Dworkis DA, et al. Health span approximates life span among many supercentenarians: compression of morbidity at the approximate limit of life span. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(4):395–405. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho J, Martin P, Poon LW. The older they are, the less successful they become? Findings from the Georgia Centenarian Study. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:695854. doi: 10.1155/2012/695854. doi:10.1155/2012/695854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willcox BJ, He Q, Chen R, et al. Midlife risk factors and healthy survival in men. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2343–2350. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perls TT, Wilmoth J, Levenson R, et al. Life-long sustained mortality advantage of siblings of centenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(12):8442–8447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122587599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerber RA, O'Brien E, Smith KR, et al. Familial excess longevity in Utah genealogies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):B130–B139. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.b130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudmundsson H, Gudbjartsson DF, Frigge M, et al. Inheritance of human longevity in Iceland. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8(10):743–749. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terry DF, Wilcox MA, McCormick MA, et al. Cardiovascular disease delay in centenarian offspring. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(4):385–389. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.4.m385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terry DF, Wilcox MA, McCormick MA, et al. Lower all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in centenarians' offspring. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):2074–2076. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willcox DC, Willcox BJ, Poon LW. Centenarian studies: important contributors to our understanding of the aging process and longevity. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2010;2010:484529. doi: 10.1155/2010/484529. doi:10.1155/2010/484529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westendorp RGJ, Van Heemst D, Rozing MP, et al. Nonagenarian siblings and their offspring display lower risk of mortality and morbidity than sporadic nonagenarians: the Leiden Longevity Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1634–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman AB, Glynn NW, Taylor CA, et al. Health and function of participants in the Long Life Family Study: a comparison with other cohorts. Aging (Albany NY). 2011;3(1):63–76. doi: 10.18632/aging.100242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajpathak SN, Liu Y, Ben-David O, et al. Lifestyle factors of people with exceptional longevity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1509–1512. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perls T, Shea-Drinkwater M, Bowen-Flynn J, et al. Exceptional familial clustering for extreme longevity in humans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(11):1483–1485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD, et al. Low risk-factor profile and long-term cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality and life expectancy: findings for 5 large cohorts of young adult and middle-aged men and women. JAMA. 1999;282(21):2012–2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baer HJ, Glynn RJ, Hu FB, et al. Risk factors for mortality in the Nurses' Health Study: a competing risks analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(3):319–329. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terry DF, Pencina MJ, Vasan RS, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors predictive for survival and morbidity-free survival in the oldest-old Framingham Heart Study participants. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):1944–1950. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fried LP, Kronmal RA, Newman AB, et al. Risk factors for 5-year mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA. 1998;279(8):585–592. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman AB, Sachs MC, Arnold AM, et al. Total and cause-specific mortality in the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(12):1251–1261. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter S, Mackenbach J, Vokó Z, et al. Genetic, physiological, and lifestyle predictors of mortality in the general population. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(4):e3–e10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noale M, Minicuci N, Bardage C, et al. Predictors of mortality: an international comparison of socio-demographic and health characteristics from six longitudinal studies on aging: the CLESA project. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40(1-2):89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burke GL, Arnold AM, Bild DE, et al. Factors associated with healthy aging: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(3):254–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4930254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman AB, Arnold AM, Naydeck BL, et al. “Successful aging”: effect of subclinical cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(19):2315–2322. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yates LB, Djoussé L, Kurth T, et al. Exceptional longevity in men: modifiable factors associated with survival and function to age 90 years. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(3):284–290. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders JL, Boudreau RM, Newman AB. Understanding the aging process using epidemiologic approaches. In: Newman AB, Cauley JA, editors. The Epidemiology of Aging. 2012 ed. Vol. 187. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span—from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328(5976):321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenyon CJ. The genetics of ageing. Nature. 2010;464(7288):504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh T, Newman AB. Inflammatory markers in population studies of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(3):319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Semba RD, Bandinelli S, Sun K, et al. Plasma carboxymethyl-lysine, an advanced glycation end product, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in older community-dwelling adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(10):1874–1880. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cappola AR, Xue Q-L, Ferrucci L, et al. Insulin-like growth factor I and interleukin-6 contribute synergistically to disability and mortality in older women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(5):2019–2025. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Austad SN. Why women live longer than men: sex differences in longevity. Gend Med. 2006;3(2):79–92. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(06)80198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newman AB, Brach JS. Gender gap in longevity and disability in older persons. Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23(2):343–350. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinsella K, He W. An Aging World: 2008. (International Population Reports, no. P95/09-1) Washington, DC: US GPO; 2009:196. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poulain M, Pes G, Salaris L. A population where men live as long as women: Villagrande Strisaili, Sardinia. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:153756. doi: 10.4061/2011/153756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finch CE, Kirkwood TB. Chance, Development, and Aging. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lakshman R, Forouhi NG, Sharp SJ, et al. Early age at menarche associated with cardiovascular disease and mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(12):4953–4960. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobsen BK, Heuch I, Kvåle G. Association of low age at menarche with increased all-cause mortality: a 37-year follow-up of 61,319 Norwegian women. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(12):1431–1437. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobsen BK, Oda K, Knutsen SF, et al. Age at menarche, total mortality and mortality from ischaemic heart disease and stroke: the Adventist Health Study, 1976–88. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(1):245–252. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giles LC, Glonek GFV, Moore VM, et al. Lower age at menarche affects survival in older Australian women: results from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:341. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-341. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Remsberg KE, Demerath EW, Schubert CM, et al. Early menarche and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors in adolescent girls: the Fels Longitudinal Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(5):2718–2724. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He C, Zhang C, Hunter DJ, et al. Age at menarche and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from 2 large prospective cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(3):334–344. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feng Y, Hong X, Wilker E, et al. Effects of age at menarche, reproductive years, and menopause on metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196(2):590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, et al. The relation of menarcheal age to obesity in childhood and adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. BMC Pediatr. 2003;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-3. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sloboda DM, Hart R, Doherty DA, et al. Age at menarche: influences of prenatal and postnatal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(1):46–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thankamony A, Ong KK, Ahmed ML, et al. Higher levels of IGF-I and adrenal androgens at age 8 years are associated with earlier age at menarche in girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(5):E786–E790. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yuan R, Meng Q, Nautiyal J, et al. Genetic coregulation of age of female sexual maturation and lifespan through circulating IGF1 among inbred mouse strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(21):8224–8229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121113109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jacobsen BK, Heuch I, Kvåle G. Age at natural menopause all-cause mortality: a 37-year follow-up of 19,731 Norwegian women. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):923–929. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ossewaarde ME, Bots ML, Verbeek ALM, et al. Age at menopause, cause-specific mortality and total life expectancy. Epidemiology. 2005;16(4):556–562. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000165392.35273.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mondul AM, Rodriguez C, Jacobs EJ, et al. Age at natural menopause and cause-specific mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(11):1089–1097. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cooper GS, Sandler DP. Age at natural menopause and mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 1998;8(4):229–235. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amagai Y, Ishikawa S, Gotoh T, et al. Age at menopause and mortality in Japan: the Jichi Medical School Cohort Study. J Epidemiol. 2006;16(4):161–166. doi: 10.2188/jea.16.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cui R, Iso H, Toyoshima H, et al. Relationships of age at menarche and menopause, and reproductive year with mortality from cardiovascular disease in Japanese postmenopausal women: the JACC study. J Epidemiol. 2006;16(5):177–184. doi: 10.2188/jea.16.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hong JS, Yi S-W, Kang HC, et al. Age at menopause and cause-specific mortality in South Korean women: Kangwha Cohort Study. Maturitas. 2007;56(4):411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirkwood TB, Austad SN. Why do we age? Nature. 2000;408(6809):233–238. doi: 10.1038/35041682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kenyon C. A pathway that links reproductive status to lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1204:156–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller RA, Harper JM, Dysko RC, et al. Longer life spans and delayed maturation in wild-derived mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2002;227(7):500–508. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perls TT, Alpert L, Fretts RC. Middle-aged mothers live longer. Nature. 1997;389(6647):133. doi: 10.1038/38148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tabatabaie V, Atzmon G, Rajpathak SN, et al. Exceptional longevity is associated with decreased reproduction. Aging (Albany NY). 2011;3(12):1202–1205. doi: 10.18632/aging.100415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gagnon A, Smith KR, Tremblay M, et al. Is there a trade-off between fertility and longevity? A comparative study of women from three large historical databases accounting for mortality selection. Am J Hum Biol. 2009;21(4):533–540. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith KR, Gagnon A, Cawthon RM, et al. Familial aggregation of survival and late female reproduction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(7):740–744. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murabito JM, Yuan R, Lunetta KL. The search for longevity and healthy aging genes: insights from epidemiological studies and samples of long-lived individuals. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(5):470–479. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Browner WS, Kahn AJ, Ziv E, et al. The genetics of human longevity. Am J Med. 2004;117(11):851–860. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Psaty BM, O'Donnell CJ, Gudnason V, et al. Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Consortium: design of prospective meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies from 5 cohorts. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2(1):73–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.829747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Willcox BJ, Donlon TA, He Q, et al. FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(37):13987–13992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anselmi CV, Malovini A, Roncarati R, et al. Association of the FOXO3A locus with extreme longevity in a southern Italian centenarian study. Rejuvenation Res. 2009;12(2):95–104. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Flachsbart F, Caliebe A, Kleindorp R, et al. Association of FOXO3A variation with human longevity confirmed in German centenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(8):2700–2705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809594106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li Y, Wang W-J, Cao H, et al. Genetic association of FOXO1A and FOXO3A with longevity trait in Han Chinese populations. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(24):4897–4904. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Soerensen M, Dato S, Christensen K, et al. Replication of an association of variation in the FOXO3A gene with human longevity using both case-control and longitudinal data. Aging Cell. 2010;9(6):1010–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00627.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pawlikowska L, Hu D, Huntsman S, et al. Association of common genetic variation in the insulin/IGF1 signaling pathway with human longevity. Aging Cell. 2009;8(4):460–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deelen J, Beekman M, Uh H-W, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a single major locus contributing to survival into old age; the APOE locus revisited. Aging Cell. 2011;10(4):686–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00705.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schächter F, Faure-Delanef L, Guénot F, et al. Genetic associations with human longevity at the APOE and ACE loci. Nat Genet. 1994;6(1):29–32. doi: 10.1038/ng0194-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Christensen K, Johnson TE, Vaupel JW. The quest for genetic determinants of human longevity: challenges and insights. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(6):436–448. doi: 10.1038/nrg1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nebel A, Kleindorp R, Caliebe A, et al. A genome-wide association study confirms APOE as the major gene influencing survival in long-lived individuals. Mech Ageing Dev. 2011;132(6-7):324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sebastiani P, Solovieff N, Dewan AT, et al. Genetic signatures of exceptional longevity in humans. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1):e29848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029848. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Seshadri S, Fitzpatrick AL, Ikram MA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1832–1840. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aulchenko YS, Ripatti S, Lindqvist I, et al. Loci influencing lipid levels and coronary heart disease risk in 16 European population cohorts. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):47–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Reiner AP, Barber MJ, Guan Y, et al. Polymorphisms of the HNF1A gene encoding hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 alpha are associated with C-reactive protein. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(5):1193–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barzilai N, Atzmon G, Schechter C, et al. Unique lipoprotein phenotype and genotype associated with exceptional longevity. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2030–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Koropatnick TA, Kimbell J, Chen R, et al. A prospective study of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene variants, and healthy aging in very old Japanese-American men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(11):1235–1240. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.11.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Beekman M, Nederstigt C, Suchiman HED, et al. Genome-wide association study (GWAS)-identified disease risk alleles do not compromise human longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(42):18046–18049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003540107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jeck WR, Siebold AP, Sharpless NE. Review: a meta-analysis of GWAS age-associated diseases. Aging Cell. 2012;11(5):727–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nebel A, Flachsbart F, Till A, et al. A functional EXO1 promoter variant is associated with prolonged life expectancy in centenarians. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130(10):691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Conneely KN, Capell BC, Erdos MR, et al. Human longevity and common variations in the LMNA gene: a meta-analysis. Aging Cell. 2012;11(3):475–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sebastiani P, Montano M, Puca A, et al. RNA editing genes associated with extreme old age in humans and with lifespan in C. elegans. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(12):e8210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008210. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barzilai N, Gabriely I, Atzmon G, et al. Genetic studies reveal the role of the endocrine and metabolic systems in aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(10):4493–4500. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stolk L, Perry JRB, Chasman DI, et al. Meta-analyses identify 13 loci associated with age at menopause and highlight DNA repair and immune pathways. Nat Genet. 2012;44(3):260–268. doi: 10.1038/ng.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Newman AB, Boudreau RM, Naydeck BL, et al. A physiologic index of comorbidity: relationship to mortality and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(6):603–609. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.6.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Vittinghoff E, et al. The effect of maintaining cognition on risk of disability and death. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(5):889–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cauley JA, Lui L-Y, Barnes D, et al. Successful skeletal aging: a marker of low fracture risk and longevity. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(1):134–143. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]