Abstract

Background

Social and family factors can influence health outcomes and quality of life of informal caregivers. Little is known about the distribution and correlates of such factors in caregivers of cancer patients. This study sought to fill this gap using data from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research & Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS).

Methods

Lung and colorectal cancer patients nominated an informal caregiver to participate in a caregiving survey. Caregivers reported their sociodemographic and caregiving characteristics, social stress, relationship quality with the patient, and family functioning. Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations assessed the distribution of caregivers’ social factors. Multivariable linear regressions assessed the independent correlates of each social factor.

Results

Most caregivers reported low-to-moderate levels of social stress and good relationship quality and family functioning. In multivariable analyses older age was associated with less social stress and better family functioning, but worse relationship quality, with effect sizes (Cohen’s D) up to 0.40 (p<0.05). Caring for a female patient was associated with less social stress and better relationship quality, but worse family functioning (effect sizes up to 0.16, p<0.05). Few caregiving characteristics were associated with social stress, while several were significant independent correlates of relationship quality. Finally, social factors were important independent correlates of one another.

Conclusions

The results indicate the importance of personal and caregiving-related characteristics and the broader family context to social factors. Future work is needed to better understand these pathways and assess whether interventions targeting social factors can improve health or quality of life outcomes for informal cancer caregivers.

MeSH Keywords: Caregivers, Interpersonal Relations, Neoplasms, Family Relations, Humans

Other Keywords: social stress, negative social interaction, relationship quality, family functioning, cancer, CanCORS

INTRODUCTION

The burden of cancer affects both individuals and their families. Informal cancer caregivers (predominantly family members or in some cases friends who provide unpaid, supportive care) play a critical role in the functional, emotional, financial, and medical well-being of individuals with cancer.1 Informal caregivers of cancer patients are a diverse group, with broad representation across ages, generations (e.g., spouse/partner, adult child, sibling), and both genders.2, 3 Despite the prevalence of cancer and the demands placed on informal caregivers during and after cancer treatment, cancer caregiver experiences – especially in life areas such as social relationships – have not been well studied.4

Social factors are important contextual elements that may be influenced by the caregiving role.5 While social support has been well characterized in informal cancer caregivers (e.g., refs.6-8), other social factors such as social stress (i.e., negative social interactions9) and relationship quality have not received the same attention in this population. Family functioning, another important social factor, has been explored among breast cancer survivors and their families, and increasingly in other cancer populations.10-14 Research across various types of informal caregivers indicates that detriments in these social factors are associated with greater psychological stress,15 caregiver burden,16-19 depressive symptoms,10, 11, 17, 20-22, anxiety,10, 11 less benefit finding,17 and prolonged grief23 among caregivers and worse emotional functioning,24 depression and anxiety10, 11 among patients, as well as other psychological outcomes.25, 26 Despite the evidence of the importance of these social factors, their prevalence and role in caregivers of adult cancer patients, specifically, has been relatively sparsely examined, such studies have often been conducted in small convenience samples of caregivers, and the interrelationships among these factors and their correlates have not been explored.

Therefore, in this hypothesis-generating, descriptive study we sought to characterize the distribution of social factors (social stress, relationship quality, and family functioning) in a sample of caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients. We evaluated the independent sociodemographic, cancer-related, and caregiving-related correlates of these factors. Better understanding of the perceived social factors characterizing informal cancer caregivers is expected to facilitate future research examining the role of these factors in caregiver outcomes, which in turn may aid in the refinement of interventions to improve cancer patient and caregiver well-being.

METHODS

This study used data from the “Share Thoughts on Care Caregiver Study” conducted by the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) consortium as an ancillary to data collection on lung and colorectal cancer patients. Detailed information about the CanCORS study protocols has been previously published7, 27, 28 and is available at https://www.cancors.org/public. Briefly, the CanCORS consortium consisted of seven study sites ascertaining patients from either cancer registries (5 sites) or healthcare systems (2 sites); the resulting sample was demographically representative within the CanCORS regions.29 Caregivers were nominated by the cancer patients in the core CanCORS survey, and contacted for participation via mail (including a self-administered questionnaire, information about the study, a postage-paid return envelope, and a $20 incentive). Caregivers were identified shortly after the baseline (n=825) or follow-up (n=802) interviews with the patient. Caregivers completed the self-administered questionnaire on average 7.3 or 15.6 months after the patients’ diagnosis, respectively.

Measures

Social stressors

Social stressors (i.e., negative social interactions) were measured with four items adapted from the work of Neal Krause (e.g., ref30 and others) asking how often others have: 1) made too many demands on them; 2) been critical of them; 3) pried into their affairs; and 4) taken advantage of them. These items were measured on a four-point Likert scale (never [1] to always [4]) and summed (range: 4-16). Higher scores correspond to more social stress. For participants missing response to one or two items (n=33), the mean of the other items was imputed for the missing item(s); the scale was unscored for those missing more items. Cronbach’s alpha for the raw items in this sample was 0.83.

Relationship quality

Current relationship quality was measured with three items assessing current closeness, communication, and overall relationship with the care recipient. Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale (not at all [1] to very well [4]) and summed (range: 3-12). Higher scores correspond to better relationship quality. For those missing responses to one item (n=27), the mean of the other items was imputed for the missing item; the scale was unscored for those missing more items. Cronbach’s alpha for the raw items in this sample was 0.83.

Prior relationship quality (before the cancer diagnosis, reported retrospectively) was also measured as a control variable using the Mutual Communal Behaviors Scale31 (range: 10-40). Higher scores correspond to better relationship quality. For those missing responses to three or fewer items (n=46), the mean of the other items was imputed for the missing item(s); the scale was unscored for those missing more items. Cronbach’s alpha for the raw items in this sample was 0.91.

Family Functioning

Family functioning was measured using the General Functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device.32, 33 This 11-item scale assesses the overall health of the family. Items were reverse coded as needed, scored on a 4-point Likert scale (Definitely False [1] to Definitely True [4]), and the mean was calculated (range: 1-4). Higher scores were coded to indicate better functioning. Cronbach’s alpha for the raw items in this sample was 0.90.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Caregivers reported their age, gender, race/ethnicity (white-non-Hispanic versus other), household income (categorized into quartiles), education status (collapsed to high school or less versus some college/trade school or more), employment status (does not work for pay, works for pay <35 hours/week, works for pay 35+ hours/week) and marital status (married/partnered versus divorced/widowed/separated/never married) in the questionnaire.

Cancer Characteristics

Patients’ age, gender, type of cancer and stage at diagnosis were obtained from the CanCORS core data. Patients self-reported the type(s) of treatment they had received by the time of the survey (surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy).

Caregiving Characteristics

Amount of care provided to the care recipient (half or less than half; most; all or almost all), relationship to the cancer patient (spouse/partner, child, parent/sibling, or other), co-residence with the patient, hours per week of care, and number of household tasks for which help was provided (including basic or instrumental activities of daily living: ADL/IADLs) were collected in the caregiver questionnaire.

Missing data were treated as follows: variables with >3% missing/unreported were recoded to include a “missing/unknown” category. Those caregivers missing data on other variables (i.e., age, gender, education, marital status, cancer type, relationship with the care recipient, coresidential status with the care recipient, and social factors) were dropped from the analysis as missing/unknown categories for these variables were too small to allow meaningful analysis. This resulted in a final sample of 1500 caregivers. Compared to those in the final sample, those dropped due to missing data (n=127, 7.8% of the full sample of caregivers) were older (31% vs 20% 71 years of age or more, p=0.03), more likely to be male (34% vs 24%, p=0.04) or non-white (51% vs 28%, p<0.001), had lower education (51% vs 24%, p<0.001) and were less likely to report their income (65% vs 43%, p<0.001) or work for money (54% vs 45%, p<0.001), more likely to not report how much care they provided (15% vs 5%, p<0.001), less likely to be caring for a child, parent, or sibling (more likely to be caring for a spouse/partner or other relative or friend; 68% vs 63%, p=0.04), more likely to provide more than 35 hours per week of care (32% vs 20%, p<0.001), and were more likely to take care of a male patient (72% vs 62%, p<0.001).

Statistical Analyses

Characteristics of the total sample were examined using descriptive statistics; the distribution of the social factors (social stress, relationship quality, and family functioning) were examined using descriptive statistics and histograms. Pearson correlations among the social factors were calculated. Finally, multivariable linear regression analyses assessed the sociodemographic, cancer-related, caregiving, and social correlates of social stress, relationship quality, and family functioning. Three linear regression models were constructed, with 1) social stress, 2) relationship quality, and 3) family functioning as the dependent variable, and participant characteristics (sociodemographic, cancer-related and caregiving, as detailed above) included as independent variables. The other social factors (those not included as the dependent variable) and relationship quality prior to the cancer diagnosis were also included in each regression model. The models explained 19.8%, 35.0%, and 30.0% of the variability in the respective dependent variables. Multicollinearity of participant characteristics was assessed using Cramer’s V. Cramer’s V was <0.50 for all variable pairs with the exception of 1) relationship type and coresidential status (Cramer’s V=0.75), and 2) the three treatment types (Cramer’s V between 0.65 and 0.76). The results of the multivariable models with relationship type and coresidential status combined into a single variable and with receipt of chemotherapy (dropping the variables for radiation and surgical treatment) were substantively unchanged and model fits were nearly identical; therefore results from the models including all variables are reported here. Effect sizes (ES) were calculated using Cohen’s d.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the caregivers. The majority were older (>50 years), female, had greater than a high school education, and were married or partnered. By design, the sample was evenly split among caregivers providing care for lung and colorectal cancer patients. Most caregivers were the primary caregiver, providing all or almost all of the help their care-recipient needed. The majority provided care to a spouse/partner (63%) and lived with the patient (73%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients (CanCORS 2005-2006)

| Total | |

|---|---|

| N= 1500 | |

| % or mean (SD) | |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | |

| Age (years) | |

| 20 to 50 | 27.13 |

| 51 to 60 | 28.67 |

| 61 to 70 | 24.27 |

| 71+ | 19.93 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 24.13 |

| Female | 75.87 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 72.4 |

| Other | 27.6 |

| Annual Household Income | |

| <$12,000 | 13.33 |

| $12,000-26,999 | 14.2 |

| $27,000-47,999 | 14.2 |

| $48,000+ | 15.47 |

| Unknown/Unreported | 42.8 |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 24.07 |

| Some college or more | 75.93 |

| Employment Status | |

| Does not work for money | 44.93 |

| Works for money, <35 hrs/wk | 15.53 |

| Works for money, 35+ hrs/wk | 34.27 |

| Unknown/Unreported | 5.27 |

| Marital Status | |

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated/Never Married | 17.8 |

| Married/Partnered | 82.2 |

| Cancer Characteristics | |

| Type of Cancer | |

| Lung | 46.67 |

| Colorectal | 53.33 |

| Stage at Diagnosis | |

| 0-I | 34.33 |

| II-III | 48.2 |

| IV | 17.47 |

| Treatment Received (not mutually exclusive) | |

| Surgery | 68.47 |

| Radiation Therapy | 25.8 |

| Chemotherapy | 58.4 |

| Caregiving Characteristics | |

| Amount of care provided | |

| Half or less | 21.73 |

| Most | 21.47 |

| All or almost all | 52.07 |

| Unknown/unreported | 4.73 |

| Relationship to patient | |

| Spouse/partner | 63.33 |

| Child | 14.8 |

| Parent/sibling | 15.13 |

| Other | 6.73 |

| Live with patient | |

| No | 26.87 |

| Yes | 73.13 |

| Hours per week of care | |

| 1 or fewer | 22.53 |

| 1 to 10 | 25.4 |

| 11 to 35 | 26 |

| More than 35 | 20.07 |

| Unknown/unreported | 6 |

| Number of care tasks | 4.35 (3.87) |

| Age of Care Recipient | |

| 0-54 | 17.73 |

| 55-64 | 28.93 |

| 65-74 | 29.33 |

| 75+ | 24 |

| Gender of Care recipient | |

| Male | 61.93 |

| Female | 38.07 |

SD: Standard deviation

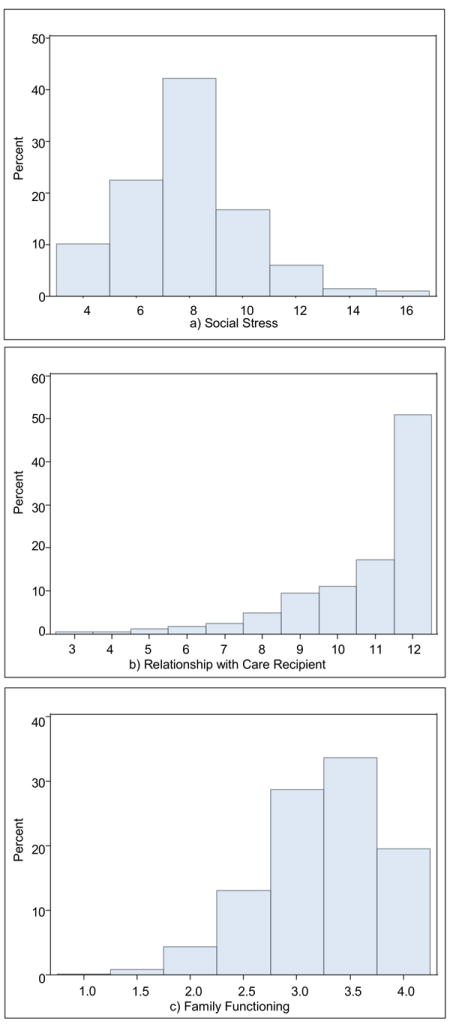

Figure 1 shows the distribution of social factors in the sample (for means and standard deviations, see Supplemental Table 1 in the online material). Most caregivers reported a low or moderate amount of social stress (right skewed distribution) (Figure 1.a); on average participants reported “sometimes” experiencing each social stressor. Current relationship quality was left skewed (Figure 1.b) and displayed a ceiling effect, in which more than 50% of the caregivers reported highest level (best relationship quality). Family functioning was somewhat left skewed (Figure 1.c), with most caregivers reporting good functioning. The social factors show small to moderate correlations ranging from -0.16 to 0.45 (p<0.0001; Supplemental Table 2, online).

Figure 1. Distribution of Social Factors Experienced by Informal Caregivers in the CanCORS (2005-2006).

Panels depict the distribution of (a) social stress (negative social interactions; questions adapted from Neal Krause, higher scores indicate more social stress), (b) quality of the relationship with the care recipient (sum of three items assessing closeness, communication, and overall relationship with the care recipient; higher scores indicate better relationship quality), and (c) family functioning (General Functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device; higher scores indicate better family functioning) among informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer survivors.

Multivariable analyses (Table 2) indicate that some sociodemographic characteristics and caregiving characteristics, but no cancer characteristics, were associated with social factors. Bivariate results of the association between the caregiver characteristics and social factors are available online (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 2.

Multivariable linear regressions of social factors on caregiver characteristics (CanCORS 2005-2006, n=1,500)

| Social Stress | Relationship Quality | Family Functioning | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | p-value | Beta | SE | p-value | Beta | SE | p-value | |

| Intercept | 7.51 | 0.68 | <.0001 | 10.21 | 0.43 | <.0001 | 2.05 | 0.14 | <.0001 |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | |||||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 20 to 50 (REF) | |||||||||

| 51 to 60 | -0.33 | 0.15 | 0.03 | -0.09 | 0.11 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.69 |

| 61 to 70 | -0.79 | 0.18 | <.0001 | -0.45 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 71+ | -0.91 | 0.21 | <.0001 | -0.30 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male (REF) | |||||||||

| Female | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.22 | -0.12 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.91 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | -0.13 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.38 | -0.04 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Other (REF) | |||||||||

| Annual Household Income | |||||||||

| <12,000 | -0.16 | 0.23 | 0.49 | -0.03 | 0.16 | 0.87 | -0.02 | 0.05 | 0.69 |

| 12,000-26,999 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.83 | -0.25 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.75 |

| 27,000-47,999 | -0.06 | 0.20 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.79 | -0.05 | 0.04 | 0.24 |

| 48,000+ (REF) | |||||||||

| Unknown/Unreported | -0.29 | 0.19 | 0.13 | -0.02 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.94 |

| Education | |||||||||

| High school or less (REF) | |||||||||

| Some college or more | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.05 | -0.09 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.32 |

| Employment Status | |||||||||

| Does not work for money | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.11 | -0.06 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Works for money, <35 hrs/wk | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| Works for money, 35+ hrs/wk (REF) | |||||||||

| Unknown/Unreported | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.03 | -0.08 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated/Never Married (REF) | |||||||||

| Married/Partnered | -0.17 | 0.16 | 0.29 | -0.17 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Cancer Characteristics | |||||||||

| Type of Cancer | |||||||||

| Lung (REF) | |||||||||

| Colorectal | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.76 |

| Stage at Diagnosis | |||||||||

| 0-I (REF) | |||||||||

| II-III | -0.13 | 0.13 | 0.33 | -0.15 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.38 |

| IV | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.98 | -0.03 | 0.12 | 0.81 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.73 |

| Received Surgery | |||||||||

| No (REF) | |||||||||

| Yes | -0.26 | 0.16 | 0.12 | -0.10 | 0.12 | 0.38 | -0.07 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Unknown/Unreported | 0.34 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 0.26 | 0.57 | 0.64 | -0.07 | 0.18 | 0.71 |

| Received Radiation | |||||||||

| No (REF) | |||||||||

| Yes | -0.23 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.42 | -0.05 | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Unknown/Unreported | -0.46 | 0.82 | 0.58 | -0.96 | 0.58 | 0.10 | -0.02 | 0.19 | 0.91 |

| Received Chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No (REF) | |||||||||

| Yes | -0.11 | 0.14 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.26 | -0.04 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Unknown/Unreported | -0.44 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.06 | -0.02 | 0.11 | 0.86 |

| Caregiving Characteristics | |||||||||

| Amount of care provided | |||||||||

| Half or Less than half (REF) | |||||||||

| Most | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.61 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.66 |

| All or almost all | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.64 |

| Unknown/unreported | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.84 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.22 |

| Relationship to patient | |||||||||

| Spouse/partner (REF) | |||||||||

| Child | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.34 |

| Parent/Sibling | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.30 |

| Other | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Live with patient | |||||||||

| No (REF) | |||||||||

| Yes | -0.21 | 0.19 | 0.27 | -0.14 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.80 |

| Hours per week | |||||||||

| 1 or fewer (REF) | |||||||||

| 1 to 10 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.71 |

| 11 to 35 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.26 |

| More than 35 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.77 | -0.15 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.94 |

| Unknown/unreported | -0.11 | 0.25 | 0.65 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.89 |

| Number of care tasks | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.77 |

| Age of care recipient | |||||||||

| 0-54 (REF) | |||||||||

| 55-64 | -0.29 | 0.17 | 0.08 | -0.02 | 0.12 | 0.87 | -0.01 | 0.04 | 0.87 |

| 65-74 | -0.15 | 0.18 | 0.41 | -0.04 | 0.13 | 0.74 | -0.05 | 0.04 | 0.25 |

| 75+ | -0.23 | 0.20 | 0.24 | -0.01 | 0.14 | 0.92 | -0.06 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Gender of care recipient | |||||||||

| Male (REF) | |||||||||

| Female | -0.35 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.02 | -0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Time of interview | |||||||||

| Baseline | -0.11 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.76 |

| Follow-up (REF) | |||||||||

| Social Factors | |||||||||

| Social Stress | -0.07 | 0.02 | 0.00 | -0.06 | 0.01 | <.0001 | |||

| Prior Relationship Quality | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.01 | <.0001 | 0.01 | 0.00 | <.0001 |

| Current Relationship Quality | -0.14 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.01 | <.0001 | |||

| Family Functioning | -1.13 | 0.11 | <.0001 | 1.04 | 0.08 | <.0001 | |||

SE: Standard error; REF: Reference group

Sociodemographic characteristics

Older age (>50 years) was associated with less social stress (ES up to 0.40, p<0.05) and better family functioning (>60 years, ES up to 0.23, p<0.05), but worse relationship quality (>60 years, ES up to 0.25, p<0.05), controlling for covariates, compared to caregivers 20-50 years of age. Having some college or more education was associated with greater social stress compared to those with less education (ES=0.10, p=0.05). Being married/partner was associated with better family functioning compared to those who were divorced, widowed, separated, or never married (ES=0.26, p<0.001).

Cancer characteristics

None of the characteristics of the patient’s cancer diagnosis or treatment were significantly associated with caregivers’ reports of social stress, relationship quality, or family functioning (p>0.05).

Caregiving characteristics

Primary caregivers reported better relationship quality (ES=0.21, p<0.001), but not social stress or family functioning, compared to those who provided half of the care or less. Those caring for a spouse or partner reported worse relationship quality than other types of caregivers (ES up to 0.25, p=0.02); those providing care to some “other” family member or friend reported better family functioning than those providing care to a spouse/partner (ES=0.24, p=0.03). Those with more caregiving tasks reported slightly greater social stress and slightly worse relationship quality (p<0.05), although the effect sizes were quite small.

Social factors

Finally, the social factors were interrelated, even after controlling for sociodemographic, cancer, and caregiving characteristics. Better current relationship quality and family functioning were associated with less social stress (ES=0.06 and 0.50, p<0.001); lower social stress and better family functioning and prior relationship quality were associated with better current relationship quality (ES=0.04, 0.06, and 0.58, p<0.001); and less social stress and better relationship quality were associated with better family functioning (ES=0.10, 0.03, and 0.19, p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the distribution and correlates of social factors among informal caregivers of individuals with lung or colorectal cancer from a multi-center study. Overall, many caregivers reported low-to-moderate levels of social stress, although levels were higher than those reported in the general population.34 Caregivers also reported good relationship quality and family functioning. Of note, caregiver age and caregiving characteristics (e.g., gender of the care recipient) were important correlates of social factors reported by informal caregivers. The findings also highlight the importance of considering the broader social milieu in evaluating caregiver and family well-being, as social stress, relationship quality, and family functioning were strong correlates of one another, even after controlling for covariates.

The multivariable analyses revealed several patterns that may spur future research directions. First, caregiver age was consistently associated with social factor outcomes. Specifically, older age was associated with less social stress and better family functioning. This is consistent with other research: older individuals in the general population also experience fewer negative social interactions,9 and older caregivers have less general psychological stress than younger caregivers;35, 36 as individuals age, they may also become better at dealing with social tensions.37 Younger caregivers may have more competing roles (e.g., work and/or child care expectations in addition to caregiving) that may be detrimental for social stress and family functioning.38 However, older age was also associated with worse relationship quality, a finding that deserves additional study.

Second, caring for a female patient was associated with less social stress and better relationship quality, but worse family functioning than caring for a male patient. This effect was independent of the gender of the caregiver, the type of relationship between the caregiver and care recipient, whether the caregiver was the primary caregiver, and other elements of the caregiving relationship. The reasons for this are unclear, and future research will be needed to confirm and clarify this pattern. Women are more likely to be family organizers than men;39 therefore a cancer diagnosis in a female may destabilize family functioning as roles shift. However female patients may have more caregivers than male patients (in this study, caregivers of females were much less likely to be a primary caregiver), which could feasibly contribute to lower social stress, although other explanations are also possible and deserve future study.

Third, several caregiving characteristics were found to be correlates of relationship quality, while fewer were related to social stress or family functioning. Previous research among breast cancer survivors suggests that the amount of care tasks or illness demands are associated with family functioning,12 although this association was not observed in this study. Factors internal to the caregiving role may have a larger influence on relationship quality, while intrapersonal and interpersonal factors may be more important for social stress and family functioning.

Fourth, while both sociodemographic and caregiving-related variables were associated with social factors, cancer-related factors were not. This is in spite of the fact that those with lung cancer and advanced disease often require more caregiver support than other types of cancer or at earlier disease stages.40, 41 This indicates that it may be individual factors (e.g., age) and contextual factors (e.g., caregiving factors) that contribute to these outcomes, rather than the disease or treatment itself. Adjustment to the disease may also be a more important predictor of social factors than diagnosis- or treatment-related factors, especially in relation to family functioning.12, 13

Finally, the social factors examined in this study were moderately strong correlates of one another, with effect sizes up to 0.6. This indicates that the broader familial context – the quantity and quality of social interactions, relationship quality and functioning between the caregiver and care recipient, and broader family functioning – is important to consider jointly in research and in caring for cancer patients and their families.

This study had several potential limitations. This was a cross-sectional study – we were therefore unable to determine temporality or directionality. All factors were self-reported; therefore, over or under reporting is a possibility, especially of social factors. There were several sociodemographic differences between those who were included in the final sample and those who were dropped due to missing data (7.8% of the full sample of caregivers), as described in the methods. Finally, caregivers were enrolled between 2005 and 2006; however, the age of the data is outweighed by the benefits of the large, multi-site sample and the detailed caregiving and cancer-related data, which are not available in most large existing datasets.

Research suggests that social, relationship, and family-related problems play an important role in adverse outcomes for informal caregivers.15-23 These factors may also directly influence patients: when cancer patients in one study had better relationships with their partners, this lessened the negative impact of pain on their quality of life.42 Interventions targeting these social factors have been effective in some populations,43, 44 although this has not been adequately tested in cancer caregiving populations. The findings from this study suggest the potential importance of targeting interventions at caregivers who may be high risk. For example, including family functioning components may be particularly effective in interventions for caregivers who are younger, caring for an immediate family member or a female patient, or who have high levels of social stress, as this study showed these individuals to have worse family functioning. Additional screening of social or relationship problems for such caregivers may also be warranted.

This study also highlights several directions for future research. Given the inter-related nature of the social factors examined in this study, does improving a single social factor (e.g., family functioning) have an ameliorative effect on other social factors? Alternatively, could targeting multiple social factors simultaneously have a synergistic effect on caregiver and/or patient health outcomes? Current interventions in informal caregivers often focus on assessing caregiver needs and fixing problems once they arise. Could preventing social issues via early intervention or family education prove even more effective? Finally, the extent to which better social factors may buffer the development of poor psychosocial, health or quality of life outcomes among caregivers deserves study. Some research supports mediation,45 suggesting the potential importance of exploring such pathways in other caregiving populations. Better understanding of the mediating and moderating effects of social factors on cancer caregiver outcomes may improve the development or delivery of interventions.

In conclusion, this study sought to examine the distribution and independent correlates of social factors among informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients using data from a large, multi-site study. Reassuringly, the findings show that many caregivers experience low-to-moderate levels of social stress and good relationship quality and family functioning, and highlight the interconnected nature of these factors. Nevertheless, a subset of individuals report poor social functioning, which may put them at risk for poor health or quality of life outcomes. Future research will be needed to explore the pathways connecting social factors to caregiver and patient outcomes in a cancer population, and whether intervening on social factors can improve these outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The CanCORS data were collected with funding from the National Cancer Institute (U01 CA93324, U01 CA93326, U01 CA93329, U01 CA93332, U01 CA93339, U01 CA93344, and U01 CA93348) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (CRS 02-164). The manuscript was prepared as part of the authors’ official duties as United States Federal Government employees.

Footnotes

COI: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The views expressed represent those of the authors and not those of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Given BA, Given CW, Sherwood PR. Family and caregiver needs over the course of the cancer trajectory. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y, Spillers RL. Quality of life of family caregivers at 2 years after a relative’s cancer diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2010;19:431–440. doi: 10.1002/pon.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Kaw CK, Smith T, Spillers RL. Sampling in population-based cancer caregivers research. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:981–989. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9518-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romito F, Goldzweig G, Cormio C, Hagedoorn M, Andersen BL. Informal caregiving for cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119(Suppl 11):2160–2169. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott G, Whyler N, Grant G. A study of family carers of people with a life-threatening illness 1: the carers’ needs analysis. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2001;7:290–291. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2001.7.6.9027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong AG, Ki P, Maharaj A, Brown E, Davis C, Apolinsky F. Social support sources, types, and generativity: a focus group study of cancer survivors and their caregivers. Soc Work Health Care. 2014;53:214–232. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2013.873515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, et al. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: a hidden quality issue? Psychooncology. 2011;20:44–52. doi: 10.1002/pon.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung HC, Tsai MC, Chen SC, Liao CT, Chen YR, Liu JF. Change and predictors of social support in caregivers of newly diagnosed oral cavity cancer patients during the first 3 months after discharge. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:E17–24. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31826c79d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lincoln KD. Social Support, Negative Social Interactions, and Psychological Well-Being. Social Service Review. 2000;74:231–252. doi: 10.1086/514478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mantani T, Saeki T, Inoue S, et al. Factors related to anxiety and depression in women with breast cancer and their husbands: role of alexithymia and family functioning. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:859–868. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards B, Clarke V. The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis on families: the influence of family functioning and patients’ illness characteristics on depression and anxiety. Psychooncology. 2004;13:562–576. doi: 10.1002/pon.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis FM, Hammond MA, Woods NF. The family’s functioning with newly diagnosed breast cancer in the mother: the development of an explanatory model. J Behav Med. 1993;16:351–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00844777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Northouse LL, Mood D, Templin T, Mellon S, George T. Couples’ patterns of adjustment to colon cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kissane DW, McKenzie M, McKenzie DP, Forbes A, O’Neill I, Bloch S. Psychosocial morbidity associated with patterns of family functioning in palliative care: baseline data from the Family Focused Grief Therapy controlled trial. Palliat Med. 2003;17:527–537. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm808oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollock EA, Litzelman K, Wisk LE, Witt WP. Correlates of physiological and psychological stress among parents of childhood cancer and brain tumor survivors. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodakowski J, Skidmore ER, Rogers JC, Schulz R. Role of social support in predicting caregiver burden. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:2229–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lum HD, Lo D, Hooker S, Bekelman DB. Caregiving in heart failure: relationship quality is associated with caregiver benefit finding and caregiver burden. Heart Lung. 2014;43:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon SJ, Kim JS, Jung JG, Kim SS, Kim S. Modifiable factors associated with caregiver burden among family caregivers of terminally ill Korean cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1243–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francis LE, Worthington J, Kypriotakis G, Rose JH. Relationship quality and burden among caregivers for late-stage cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1429–1436. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0765-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodakowski J, Skidmore ER, Rogers JC, Schulz R. Does social support impact depression in caregivers of adults ageing with spinal cord injuries? Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:565–575. doi: 10.1177/0269215512464503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haley WE, LaMonde LA, Han B, Burton AM, Schonwetter R. Predictors of depression and life satisfaction among spousal caregivers in hospice: application of a stress process model. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:215–224. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Triemstra M, van den Bos GA, Sanderman R. The role of social and psychologic resources in caregiving of cancer patients. Cancer. 2001;91:1029–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas K, Hudson P, Trauer T, Remedios C, Clarke D. Risk factors for developing prolonged grief during bereavement in family carers of cancer patients in palliative care: a longitudinal study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green HJ, Wells DJ, Laakso L. Coping in men with prostate cancer and their partners: a quantitative and qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:237–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hubbard G, Menzies S, Flynn P, et al. Relational mechanisms and psychological outcomes in couples affected by breast cancer: a systematic narrative analysis of the literature. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3:309–317. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rottmann N, Hansen DG, Larsen PV, et al. Dyadic coping within couples dealing with breast cancer: A longitudinal, population-based study. Health Psychol. 2015;34:486–495. doi: 10.1037/hea0000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malin JL, Ko C, Ayanian JZ, et al. Understanding cancer patients’ experience and outcomes: development and pilot study of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance patient survey. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catalano PJ, Ayanian JZ, Weeks JC, et al. Representativeness of participants in the cancer care outcomes research and surveillance consortium relative to the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Med Care. 2013;51:e9–15. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318222a711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krause N, Borawski-Clark E. Social class differences in social support among older adults. Gerontologist. 1995;35:498–508. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.4.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson GM, Schulz R. Caring for a Family Member With Cancer: Past Communal Behavior and Affective Reactions1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1995;25:93–116. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The Mcmaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller IW. The McMaster Family Assessment Device: Reliabilty and Validity. J Marital Fam Ther. 1985;11:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sneed RS, Cohen S. Negative social interactions and incident hypertension among older adults. Health Psychol. 2014;33:554–565. doi: 10.1037/hea0000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Evans TV. Age and attachment style impact stress and depressive symptoms among caregivers: a prospective investigation. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Litzelman K, Skinner HG, Gangnon RE, Nieto FJ, Malecki K, Witt WP. Role of global stress in the health-related quality of life of caregivers: evidence from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1569–1578. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0598-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birditt KS, Fingerman KL. Do we get better at picking our battles? Age group differences in descriptions of behavioral reactions to interpersonal tensions. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:P121–P128. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.p121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Do EK, Cohen SA, Brown MJ. Socioeconomic and demographic factors modify the association between informal caregiving and health in the Sandwich Generation. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:362. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmerman TS, Haddock SA, Ziemba S, Rust A. Family organizational labor: Who’s calling the plays? J Fem Fam Ther. 2002;13:65–90. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim Y, Spillers RL, Hall DL. Quality of life of family caregivers 5 years after a relative’s cancer diagnosis: follow-up of the national quality of life survey for caregivers. Psychooncology. 2012;21:273–281. doi: 10.1002/pon.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:4362–4373. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan MA, Small BJ, Donovan KA, Overcash J, McMillan S. Cancer patients with pain: the spouse/partner relationship and quality of life. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:13–23. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181efed43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Svavarsdottir EK, Sigurdardottir AO. Benefits of a brief therapeutic conversation intervention for families of children and adolescents in active cancer treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40:E346–357. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.E346-E357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moon H, Adams KB. The effectiveness of dyadic interventions for people with dementia and their caregivers. Dementia (London) 2013;12:821–839. doi: 10.1177/1471301212447026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rauktis ME, Koeske GF, Tereshko O. Negative social interactions, distress, and depression among those caring for a seriously and persistently mentally ill relative. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:279–299. doi: 10.1007/BF02506939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.