Abstract

Objective

Psychosis, like other neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, has many features that make predictive modeling of its onset difficult. For example, psychosis onset is associated with both the absolute degree of cognitive impairment and the rate of cognitive decline. Moreover, psychotic symptoms, while more likely than not to persist over time within individuals, may remit and recur. To facilitate predictive modeling of psychosis for personalized clinical decision making, including evaluating the role of risk genes in its onset, we have developed a novel Bayesian model of the dual trajectories of cognition and psychosis symptoms.

Methods

Cognition was modeled as a four-parameter logistic curve with random effects for all four parameters and possible covariates for the rate and time of fall. Psychosis was modeled as a continuous-time hidden Markov model with a latent never-psychotic class and states for pre-psychotic, actively psychotic and remitted psychosis. Covariates can affect the probability of being in the never-psychotic class. Covariates and the level of cognition can affect the transition rates for the hidden Markov model.

Results

The model characteristics were confirmed using simulated data. Results from 434 AD patients show that a decline in cognition is associated with an increased rate of transition to the psychotic state.

Conclusions

The model allows declining cognition as an input for psychosis prediction, while incorporating the full uncertainty of the interpolated cognition values. The techniques used can be used in future genetic studies of AD and are generalizable to the study of other neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, cognitive impairment, neuropsychiatric symptoms

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by a progressive decline in cognition. We have previously published a Bayesian methodology for modeling the changes in cognition which realistically accounts for an initial period of stable cognition, subject-to-subject variability in trajectories, and available demographic and genetic covariates (Sweet et al., 2012). Psychotic symptoms emerge during the course of cognitive decline in approximately half of AD patients, contributing to patient and family distress, and identifying a subgroup at risk for greater morbidity and mortality (Murray et al., 2014). The risk for psychosis in AD is heritable, and its onset is influenced strongly by the preceding degree of cognitive decline (Murray et al., 2014). Ultimately, identifying subjects at risk for psychosis during AD may allow the implementation of preventative non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions (Geda et al., 2013).

Thus the genesis of this paper is the desire to model individual psychosis symptom trajectories, including prediction of psychosis, both to enhance clinical prognosis and to increase the power to detect associations with genetic variations that increase the risk for these deleterious symptoms. We use the psychosis items on the Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia (BRSD) of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD) to measure psychosis (Tariot et al., 1995). This gives a discrete outcome over a wide scale. Clinical observations have indicated that small scores can occur in patients without psychosis, so a non-zero value is not a strong indication of psychosis (e.g. phenocopies). We would like to characterize patients into two main groups: never psychotic and psychotic. Although psychosis symptoms, once present, are largely persistent, some fluctuation occurs, so that the psychotic group is comprised of patients who experience both “active” periods of psychosis, with higher psychosis scores alternating with periods of lower scores, which we call “remission”. In addition, the cognition score may influence the timing of the development of psychosis (Murray et al., 2014). Finally demographic (Ropacki and Jeste, 2005) and genetic (DeMichele-Sweet and Sweet, 2014) covariates may affect both the chance of ever developing psychosis as well as the timing of the development of psychosis.

With all of these clinical observations in mind, we developed a dual trajectory approach that simultaneously models the decline in cognition and the pattern of psychosis symptoms. We model the decline in cognition across subjects over time using a four-parameter logistic curve with random effects to reflect individual differences in the shape of the cognition trajectories as well as including appropriate covariates (Sweet et al., 2012) that may affect the shapes of the individual curves. The observed psychosis symptoms are considered to be an overt manifestation of underlying latent (hidden) states. Based on the clinical information, the psychosis portion of our dual model includes the following latent states: a never-psychotic state, a pre-psychotic state, an active psychosis state, and a “remission” state (relatively asymptomatic, but occurring after at least one active psychosis period). This is implemented as a hidden Markov model (HMM), with transitions allowed from pre-psychotic to active psychosis, and between active and remission. The observed psychosis scores are modeled as following a Poisson distribution with the mean dependent on the latent state. The model allows demographic and genetic covariates to affect the probability of being in the never-psychotic state. In addition, demographic and genetic covariates as well as the concurrent cognition state may affect the transition rate from pre-psychotic to active psychosis.

This dual trajectory approach flexibly models many important clinical features of Alzheimer's disease while incorporating random effects to appropriately account for unmeasured individual characteristics. The most useful model outputs are estimates of the effects of covariates on being in the never-psychotic state, estimates of the effects of covariates on the transition to active psychosis, and prediction of future psychotic states of individual subjects.

Data and modeling framework

All subjects participated in the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC), using a protocol approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. All subjects were assessed at baseline with standardized neurological, neuropsychological, psychiatric evaluations, cognitive testing, laboratory studies, and brain imaging as previously described (Becker et al., 1994; Lopez et al., 1997; Sweet et al., 1998; Wilcosz et al., 2006). Subjects diagnosed with Possible or Probable AD (McKhann et al., 1984; Lopez et al., 2000a; Lopez et al., 2000b) or MCI (Lopez et al., 2003) without psychosis at baseline were included in the analyses.

All subjects underwent a neuropsychological battery assessing global cognitive functioning that included the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975). Neurological evaluation, cognitive testing, and diagnostic re-evaluation were conducted on an annual basis. Subjects were followed longitudinally until study completion, loss to follow-up, or until the subject became too impaired to return to clinic for assessments. Psychosis was assessed using the CERAD BRSD, administered at baseline and annual assessments, and between assessments at approximately six month intervals via telephone, an approach yielding excellent reliability of psychosis ratings (Weamer et al., 2009).

There were 434 subjects with at least two MMSE observations for cognition and at least two CERAD BRSD observations for psychosis. We scored psychosis as the total number of symptoms observed for at least 3 days in the past month. The range is 0 to 11 with a mean of 0.24 and 86% of the scores are zero. The mean number of MMSE observations is 3.56, and the mean number of psychosis observations is 6.89.

Thirty-nine percent of the subjects are male, 51% have greater than a high school education, and 7% are African American.

Modeling is carried out in the Bayesian framework using open source software. Key parameters indicate the log odds of never becoming psychotic (λ), the transition rate from pre-psychotic to active psychosis (a), and transition rates from active to remission and the reverse (β and γ). In addition there are parameters for the effects of covariates on these rates, with special interest in the effect of cognition on the pre-psychotic to active transition (ρ). Additional modeling details may be found in the appendix.

Simulation results

We first evaluated the methodology using simulated data. The simulations were based on generating scores for cognition and psychosis with characteristics similar to that of the Alzheimer's subjects but using a variety of patterns of arbitrarily chosen parameter values. This includes simulated data sets with both zero and nonzero values of the “ρ” parameter, which represents the effect of the level of the cognition score on the rate of transition to active psychosis. The simulated data sets each contained 500 subjects with covariates similar to the clinical subjects. The ability to recover the true parameter values in the analysis results is one good way to validate the model.

Results are provided for ten simulated datasets. Rather than duplicating our previous work on cognition, we report here only on the psychosis portion of the model.

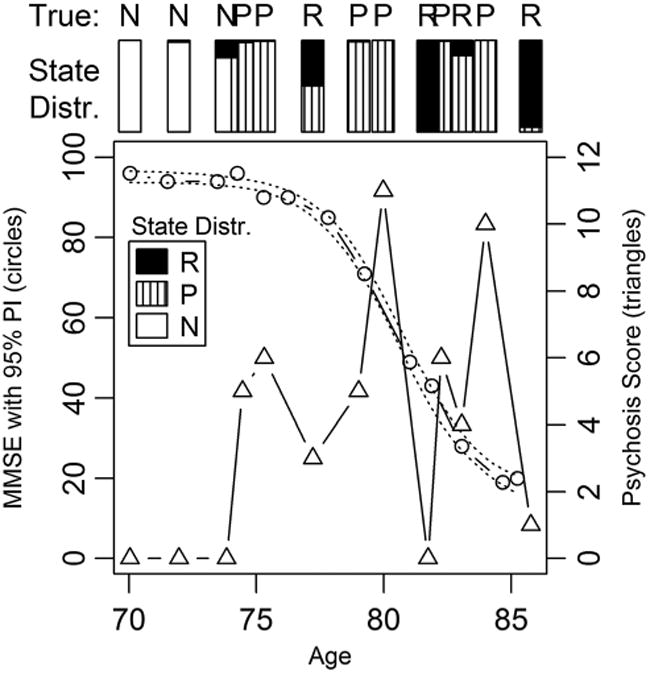

To begin the evaluation of the simulations, we made plots for individual subjects showing the observed psychosis scores, the true values of the states, and the posterior probability distributions of the states. An example plot for one subject is shown in Figure 1, which displays the observed MMSE scores with the 95% posterior interval, the observed psychosis scores, the posterior distributions of the latent states (where “N” = not psychotic (pre-plus never), “P” is actively psychotic, and “R” is remission), as well as the true latent states for the simulated data.

Figure 1.

Simulated MMSE and psychosis scores with true and inferred latent states (N = not psychotic, P = psychotic, and R = remission).

These plots qualitatively demonstrate that the model performs appropriately in several ways. For subjects truly assigned to never being psychotic, there is always some probability assigned to the chance that they will become psychotic in the future, and the longer they are observed, the less the chance that they will ever become psychotic. For subjects who are truly assigned to eventually becoming psychotic, those whose true state is pre-psychotic for the duration of the observation period show a moderate chance of being never psychotic, particularly when the observation period is long. For subjects who truly become psychotic during the observation period, the posterior probability of being never psychotic is near zero, and the probability distributions of the three states at each observation period are as expected: nearly 100% pre-psychotic initially; most of the probability on active psychosis during the first period of psychosis; and a mixed distribution of active and remission after the first psychosis with near 100% probability of active for the highest psychosis scores, and near 100% chance of remission for those with the lowest scores

Quantitatively, we examine the 95% posterior intervals for a variety of simulations. Table 1 shows the coverage of the 95% posterior intervals broken down by model section: parameters for modeling the effects of cognition and demographic covariates of the rate of transition from pre-psychotic to active psychosis (α), parameters for modeling the transition from active psychosis to latent and vice versa (β and γ), and parameters for modeling effects of covariates on the log of the odds of the never-psychotic state. The appropriate coverage of the true parameter values by the posterior intervals is a good confirmation of the model.

Table 1. Coverage of 95% posterior intervals for simulated data.

| Model section | Number of simulated data sets | Number of parameters fit | Number of 95% posterior intervals containing the true parameter value | Percent coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log of alpha | 10 | 50 | 46 | 92 |

| Beta/gamma | 10 | 20 | 20 | 100 |

| Never psychotic | 10 | 40 | 37 | 92 |

| Poisson means | 10 | 30 | 29 | 97 |

Additional simulations show that the model behaves appropriately when misspecified, e.g. showing a posterior interval equal to zero when an effect is not included in the simulation. We also validated the appropriateness of the Poisson distribution for the psychosis scores.

To evaluate prediction, models were run after replacing the last cognition and psychosis scores with missing values. For simplicity, we made the timing of the missing values exactly 0.5, 1, or 2 years after the last observed values. To evaluate the effectiveness of individual predictions, groups were formed of observations with similar predicted state probabilities, and the observed state distributions were compared to the true state distributions for those observations. This was performed for probability of being a never-psychotic subject, probability of being in active psychosis, and probability of being in either the psychotic or latent states. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals based on the binomial distribution are computed to aid in evaluation of the match between expected and observed probability. None of these analyses have more than a single group outside of the 95% confidence interval for the desired probability, implying accurate predictions intervals.

Results on patients with Alzheimer's disease

We ran the model on our Alzheimer subjects, and the results are shown in Table 2. The intercept for the log of alpha refers to the log of the rate of transition from pre-psychotic to psychotic for a subject with the maximum cognition level and baseline values of the covariates (female, no higher education, and white race). To better explain the estimate, we compute the expected percentage of subjects who leave the pre-psychotic state after one year (Norris, 1997) before observing a drop in cognition. This is estimated to be 3.17% (95% posterior interval= [1.92, 5.38]). None of the coefficients for the demographic covariates show evidence of an effect on the rate of transition to psychosis, but cognition does have an effect. The estimate of the expected percentage of subjects who leave the pre-psychotic state after one year for a baseline subject with, say, a 40% drop in cognition (based on the estimate of ρ) is 19.0% [13.6, 26.1].

Table 2. Posterior statistics for parameters for HMM for AD subjects.

| Model section | Parameter | Posterior mean and 95% posterior interval |

|---|---|---|

| Log of alpha | Intercept | −3.43 [−3.94, −2.90] |

| Cognition level (ρ) | 4.43 [3.46, 5.42] | |

| Higher Education | −0.14 [−0.64, 0.41] | |

| African American | 0.04 [−0.86, 0.78] | |

| Male | −0.08 [−0.59, 0.40] | |

| Beta/gamma | Beta (transition from | 1.64 [0.84, 3.12] |

| active to remission) | ||

| Gamma (transition from remission to active) | 0.45 [0.12, 1.08] | |

| Never psychotic (λ) | Intercept | −1.73 [2.78, −0.89] |

| Higher education | −0.54 [−2.13, 0.91] | |

| African American | −0.45 [−2.04, 1.02] | |

| Male | 0.26 [−1.14, 1.49] | |

| Poisson means | Pre-psychotic | 0.029 [0.020, 0.039] |

| Active psychosis | 2.44 [2.01, 2.98] | |

| Remission | 0.786 [0.602, 0.982] |

The β and γ parameters (see appendix for more details) can be used to estimate the percentage of the time that subjects spend in the active psychosis state once they leave the pre-psychotic state. The estimate is 20.6% [7.8, 37.1].

We can express the results for the never-psychotic parameters as the percentage of subjects who are expected to never become psychotic. For the baseline group, this is 16.7% [6.6, 32.2]. For those with higher education, e.g. this estimate is 10.3% [1.6, 39.8], and the large amount of overlap with the baseline group is because of the fact that zero is well inside the 95% posterior interval for the higher education parameter. The latter negative result also applies to race and gender.

Our model uses probability distributions of psychosis scores rather than hard cutoffs to distinguish the psychosis states. As is clinically expected, the Poisson posterior mean for the pre-psychotic state is very low, and it shows that such subjects in that state have a 97.1% probability of a zero psychosis score, a 2.8% probability of a one, and a very small probability of higher scores. In the active state we find 95% of psychosis scores between zero and six with 8.5% zeroes and 21.0% ones. The remission state corresponds to percentages for scores 0 to 3 equal to 45.0, 35.9, 14.4, and 3.8% respectively. The overlaps among the possible psychosis scores for these latent states imply that a clear definition of psychosis state based on psychosis scores is not ideal, and a probabilistic, model-based definition will perform better.

Discussion

The custom Bayesian model described here allows us to model the complex trajectory of psychosis symptomatology in Alzheimer's disease. It provides for realistic clinical features including a hidden state that never transitions to psychosis, the transition to psychosis with alternative periods of symptom remission, the effect of cognition on psychosis, and the effects of covariates, such as demographics. Moreover, the model allows for the introduction of other covariates, such as genetic variants, to influence psychosis risk via effects on the chance of being in the never-psychotic state and on the rate of transition to psychosis. Our model is based on freely available software and is easily adapted to other measures of cognition and/or psychosis as well as choice of covariates.

In terms of learning about psychosis in Alzheimer's disease, our findings lead to several conclusions. Because of the apparent overlap in possible psychosis scores among the different clinically apparent latent states, a fixed definition of psychosis based on observed psychosis scores is not realistic, and our trajectory-based latent class modeling framework is needed to assign probability distributions for the states at any moment in time. In addition we have estimated the proportion of subjects who are likely to never become psychotic, and can assign probabilities of being in this class to individual subjects based on the observed data to date. We have also tested the effects of available demographics and cognition on psychosis. None of our demographics show an effect on the probability of being never psychotic, nor on the mean time spent in the pre-psychotic state before transition to psychosis. Lower cognition scores are strongly associated with a more rapid transition to psychosis. These observations comport well with existing data on the relationship of these variables to the presence of psychosis (Murray et al., 2014).

Currently, no genetic variants have been definitively associated with the risk of psychosis in AD (Murray et al., 2014). However, this model can be readily used to evaluate either strong individual genetic factors associated with psychosis in AD or a composite psychosis score that reflects the combined effects of multiple genetic markers. This will allow us to determine whether these genetic effects on psychosis risk are mediated by their effects on cognitive trajectory, or whether they directly impact the likelihood of the never psychosis state or the rate of conversion to psychosis. In addition, with sufficiently strong demographic and genetic inputs, this Bayesian model is capable of making useful predictions about individual subjects, e.g. the probability of transitioning to psychosis at a particular future time—a form of personalized medicine.

The statistical contributions of this paper include demonstration of incorporating an isolated state (never psychotic) into a HMM using JAGS with its msm module, and demonstration of the use of dual trajectory modeling to fully incorporate the uncertainty of one trajectory as an input to another trajectory. The Bayesian model is ideal for prediction, as demonstrated with simulated data. It is easy to demonstrate that the four-parameter-logistic model for cognition appropriately increases the uncertainty as we predict farther into the future, and therefore using a single Bayesian model that incorporates both the cognition trajectory and the hidden Markov model for psychosis is able to account for the uncertainty appropriately for predictions. This would not be true, e.g. for a two stage model where cognition is fit with one model, and the predicted values are used as input for the psychosis model.

Potential future work includes adding covariates to the beta and gamma components to the model to see if any affect the time spent in active psychosis vs. remission, but this will probably require larger number of subjects who transition to psychosis. We would also like to investigate the effects of anti-psychotic and anti-dementia medications on the rate parameters of the HMM, and these time varying covariates will be well represented by a step function. Finally, we would like to investigate other measures of psychosis, e.g. incorporating frequency and count of symptoms instead of just count.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Joint modeling of cognition and psychosis in AD can account for the association between the two. A drop in cognition score is associated with an increase transition to psychosis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grant AG 027224. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

Appendix: Technical modeling details

We implement our Bayesian dual trajectory model using JAGS (http://mcmc-jags.sourceforge.net/) running in rube (http://www.stat.cmu.edu/∼hseltman/rube/) within R (http://www.r-project.org/). Our rube package includes many convenience functions that improve the efficiency of working with JAGS (or WinBUGS). These include conditional model elements, named model hyperparameters to facilitate testing sensitivity to prior distributions, and automatic model code generation with covariate specification at run time. The continuous-time hidden Markov model is accommodated by the msm module of JAGS. All of this software is open source and freely available.

Typical run times for the Bayesian dual trajectory model on a 2.4 GHz PC running Windows 7 were 20 to 30 h based on three parallel MCMC chains, each with 8000 iterations after a burn in of 2000 iterations. We visually evaluated all parameters for convergence and mixing, supplementing this with Gelman R-hat scores (Ntzoufras, 2009).

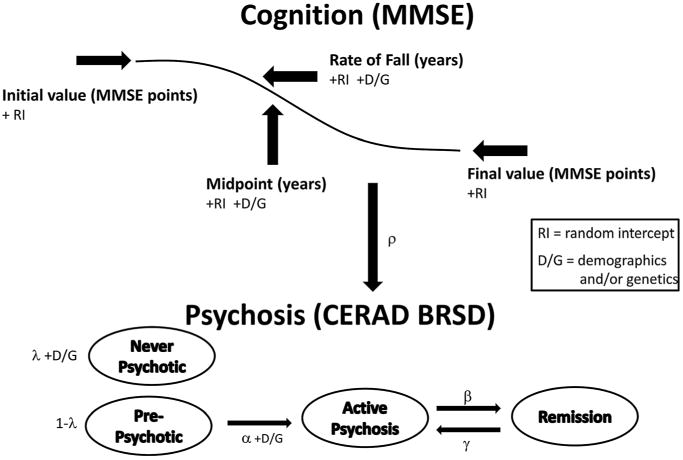

All details of the cognition trajectory modeling may be found in our prior paper (Sweet et al., 2012). The psychosis score trajectories are modeled as a hidden Markov model, where the hidden part refers to the true unobserved (latent) psychosis states. Given a latent state, the observed psychosis scores are modeled using the Poisson distribution with a common mean for the never-psychotic and pre-psychotic latent states and separate means for the active and the remission latent states. A graphical summary of the model is shown in Figure A1.

Limitations of the multi-state modeling of the msm module preclude an isolated state such as our “never-psychotic” state. Therefore we implement the never-psychotic state using a latent class mixture (mimicking the method of Ghosh (Ghosh et al., 2006)) of the never-psychotic state with a three-state HMM for the other states. The log of the odds of the never-psychotic state (parameter λ) is modeled as a linear combination of baseline covariates in the model.

Figure A1.

Graphical model summary.

The continuous time three-state hidden Markov chain is parameterized with the following notation for the transition rates:

The transition rate from pre-psychotic to active psychosis, α, includes covariates by modeling the log of α as a linear combination of covariates. We call the effect of the current level of cognition (coded as fraction dropped from the highest possible score) on the α transition rate ρ. Covariates are not currently included for β and γ, because of the relatively limited information provided by the available data about these parameters.

Weak proper priors are used for all of the log-transition and covariate parameters (Gaussian distributions with a large variance). For the Poisson means, weakly informative gamma distributions are used to help maintain the ordering of the hidden states. Specifically we used mean = 0.5, sd = 0.7 for non/pre-psychotic, mean = 8.3, sd = 3.7 for active psychosis, and mean= 1.3, sd = 0.9 for remission.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no personal or financial conflicts of interest that might bias this work.

Supporting information: Additional supporting information maybe found on the online version of this article at the publisher's web site.

References

- Becker JT, Boller F, Lopez O, Saxton J, McGonigle KL. The natural history of Alzheimer's disease: description study of cohort and accuracy of diagnosis. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:585–594. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540180063015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMichele-Sweet MA, Sweet RA. Genetics of psychosis in Alzheimer disease. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2014;2(1):30–38. doi: 10.1007/s40142-014-0030-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geda YE, Schneider LS, Gitlin LN, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: past progress and anticipation of the future. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh SK, Mukhopadhyay P, Lu JC. Bayesian analysis of zero inflated regression models. J Stat Plan Inference. 2006;136:1360–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jspi.2004.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Kamboh MI, Becker JT, Kaufer DI, DeKosky ST. The Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele is not associated with psychiatric symptoms or extrapyramidal signs in probable Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1997;49:794–797. doi: 10.1212/WNL.49.3.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Becker JT, Klunk WE, et al. Research evaluation and diagnosis of possible Alzheimer's disease over the last two decades: I. Neurology. 2000a;55(12):1854–1862. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.12.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Becker JT, Klunk WE, et al. Research evaluation and diagnosis of possible Alzheimer's disease over the last two decades: II. Neurology. 2000b;55(12):1863–1869. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.12.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Jagust WJ, DeKosky ST, et al. Prevalence and classification of mild cognitive impairment in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study part 1. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(10):1385–1389. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PS, Kumar S, DeMichele-Sweet MA, Sweet RA. Psychosis in Alzheimer disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75(7):542–552. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris JR. Markov Chains. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1997. pp. 60–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ntzoufras I. Bayesian Modeling Using WinBUGS. Wiley; New York: 2009. pp. 132–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ropacki SA, Jeste DV. Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer's disease: a review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2022–2030. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet RA, Nimgaonkar VL, Kamboh MI, et al. Dopamine receptor genetic variation, psychosis, and aggression in Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(10):1335–1340. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.10.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet RA, Seltman H, Emanuel JE, et al. Effect of Alzheimer disease risk genes on trajectories of cognitive function in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):954–962. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11121815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariot PN, Mack JL, Patterson MB, et al. The Behavior Rating Scale for dementia of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's Disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(9):1349–1357. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weamer EA, Emanuel JE, Miyahara S, et al. The relationship of excess cognitive impairment in MCI and early Alzheimer's disease to the subsequent emergence of psychosis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(1):78–85. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208007734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcosz PA, Miyahara S, Lopez OL, DeKosky ST, Sweet RA. Prediction of psychosis onset in Alzheimer disease: the role of cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and further evidence for psychosis subtypes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(4):352–356. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192500.25940.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.