Abstract

The Rickettsia bacteria include the aetiological agents for the human spotted fever (SF) disease. In the present study, a SF groupRickettsia amblyommii related bacterium was detected in a field collected Amblyomma sculptum (Amblyomma cajennense species complex) tick from a Brazilian SF endemic site in southeastern Brazil, in the municipality of Juiz de Fora, state of Minas Gerais. Genetic analysis based on genes ompA,ompB and htrA showed that the detected strain, named R. amblyommii str. JF, is related to the speciesR. amblyommii.

Keywords: Rickettsia amblyommii, Amblyomma sculptum, southeastern Brazil -, ticks

Over the past 14 years, the number of rickettsial species identified in South America increased from three to more than 10. Initially, only occurrences of Rickettsia prowazekii, Rickettsia typhi, and Rickettsia rickettsii were historically reported, followed by most recent detection ofRickettsia felis, Rickettsia parkeri,Rickettsia belli, Rickettsia massiliae,Rickettsia rhipicephali, and Rickettsia amblyommiifrom different environmental samples (Labruna 2009).

Among those cited, six species belong to the spotted fever group (SFG), including the known human pathogens R. rickettsii, R. felis,R. Parkeri, and R. massiliae, each causing specific rickettsiosis, whereas R. rhipicephali and R. amblyommii are classified as with still unknown/unclear pathogenicity (Merhej et al. 2014).

R. rickettsii is the aetiologic agent of the Rocky Mountain SF, the most severe of all tick-borne rickettsiosis (Parola et al. 2005). In Brazil this species causes the Brazilian SF (BSF), a disease that in the last 14 years was reported in 1,421 cases throughout Brazil, according to official data of the Information System on Notifiable Diseases (dtr2004.saude.gov.br/sinanweb/). During the period of 1995-2004, there were 334 laboratory-confirmed cases of BSF with a 31% lethality rate in the Southeast Region of Brazil. Additional 128 cases, with lethality of 29%, were confirmed from 2005-2007 only in the state of São Paulo (Labruna 2009). In the state of Minas Gerais other BSF cases were also confirmed and in the endemic area of the city of Juiz de Fora, 24 cases were actually confirmed between 2001-2014 (dtr2004.saude.gov.br/sinanweb/). According to Pacheco et al. (2011), 17 cases were notified between 1995-2008, with a lethality of 29%.

Ticks are the most important vectors for SF transmission. In South America, the tickAmblyomma cajen- nense has been considered to be the most frequent vector related with SF cases. Interestingly recent genetic and morphological/microscopic analyses showed evidence that A. cajennense in fact represents a complex grouping six tick species (A. cajennensesensu lato ors.l.) (Beati et al. 2013,Nava et al. 2014).

The endemicity of BSF leads Juiz de Fora Health Office to promote a constant environmental monitoring of ticks. Forty-eight horses fed A. sculptumticks were obtained during this vigilance and the specimens were identified according to the new description of species that belong to the A. cajennense complex (Nava et al. 2014). The neighbourhoods known as Previdenciários and Monte Castelo were visited and both areas had confirmed human BSF cases. Sampled ticks were processed for molecular analysis and initially submitted to DNA extraction as described elsewhere [method with NaCl (Aljanabi & Martinez 1997)].

Rickettsia infected ticks were identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening for the rickettsial ompA, ompB andhtrA genes in 25 μL conventional PCR reactions under the temperature/time cycle: 94ºC 3 min and 30 s (94ºC 30 s, 55ºC 30 s, 72ºC 1 min/Kb] 40X, 72ºC 7 min, 20ºC ∞. R. parkeri str. AT#24 DNA was used as a positive control. The primers used were Rr190.70F and Rr190.602R (Regnery et al. 1991) for ompA gene, Rr1175F and Rr2608R (Blair et al. 2004) for htrAgene and ompB3064-F (5’ggtatagccggaataggttttgacg, present study) and ompB4271-R (5’tcagttttagtgataccgatagcagc, present study) for ompB gene. PCR products were purified using HiYieldTM Gel/PCR DNA Mini Kit according to manufacturer (Real GenomicsTM, New Zealand), sequenced in both directions on an automated ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems®, USA) and using the same primers applied for the initial PCR amplifications. Sequence edition was performed with Lasergene software packages (DNASTAR, USA).

One A. sculptum female was positive for Rickettsiainfection as determined by the PCR tests. PCR amplicons of 512 bp, 1,208 bp, and 434 bp were obtained using the primer sets for ompA, ompB andhtrA, respectively.

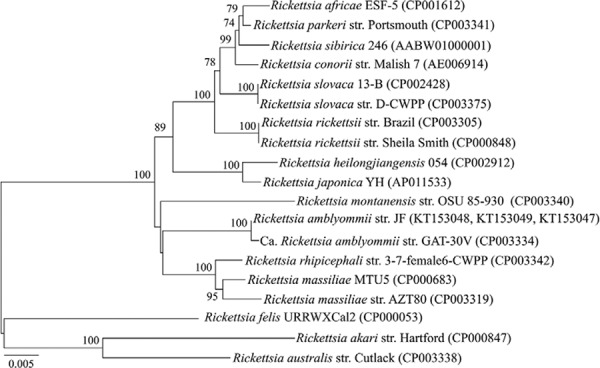

A phylogenetic tree was constructed with concatenated ompA,ompB and htrA sequences, neighbour-joining methods [MEGA 5.2 (Tamura et al. 2011)], and Kimura two-parameter model to estimate genetic divergence (Kimura 1980) and bootstrap values were obtained from 1,000 randomly generated trees. The resulting tree showed that the presently identified strain, here named R.amblyommii str. JF, is most closely related to R. amblyommii (Figure).

Phylogenetic tree of concatenated spotted fever group rickettsiaeompA, ompB and htrAgenes constructed by neighbour-joining method with Kimura two-parameter as evolution model and based on the nucleotide sequences. The GenBank accession codes are presented in parenthesis. The numbers at nodes are the bootstrap values obtained from 1,000 re-samplings. Bootstrap values bellow 70% are not present.

The first detection of R. amblyommii occurred after analysis ofAmblyomma americanum ticks in the United States of America (Burgdorfer et al. 1981). After that, R. amblyommii and other genetically related species were found in a wide variety of tick species in different countries in the New World (Labruna et al. 2007, Zanettii et al. 2008, Hun et al. 2011, Saraiva et al. 2013). In the present study, aR. amblyommii related infection was characterised in an A. sculptum sample, an A. cajennense-complex species abundantly observed in Juiz de Fora. Other bacteria genetically related to R. amblyommii was previously found associated with A. cajennenses.l. from Brazil (Labruna et al. 2004, Soares et al. 2015) and Alves et al. (2014) provided the first description of R. amblyommii-like infection in A. sculptumtick.

Despite the amount of studies on Rickettsia performed in thousands of ticks sampled in southeastern Brazil (Guedes et al. 2005, Gehrke et al. 2009, Pacheco et al. 2009), the present paper is the first report of a R. amblyommii related SFG infecting A. sculptum in this region.

Several reports indicate that R. amblyommii is commonly found in ticks parasitising human (Jiang et al. 2010, Lee et al. 2014) and the observed R. amblyommii in Juiz de Fora could distinctly represent an unusual rickettsiosis agent. Primarily nonpathogenic Rickettsia is able to cause disease under some circumstances, as reported for R. parkeri(Paddock et al. 2004). The pathogenic potential of R. amblyommii and genotypically similar strains is still speculative, but increasingly studies have associate these bacteria to rickettsiosis cases (Taylor et al. 1985, Yevich et al. 1995, Billeter et al. 2007, Apperson et al. 2008).

The potential pathogenic capacity of R. amblyommii would bring major concerns in terms of public health since this bacterium can infect a variety of vertebrate hosts with wide distribution, including species with dense populations and commonly found in parks or recreational areas (Blanton et al. 2014).

Despite that not all ticks can actively feed and parasitise humans, serological data obtained from dogs and horses showed the circulation of R. amblyommiiin domestic animals (Barrett et al. 2014). Frequent infestation of these animals with specific tick species could facilitate the transmission of this bacterium to humans. Indeed, ticks frequently found on dogs and horses have been reported to be able to support R.amblyommii infection (Bermúdez et al. 2009, Eremeeva et al. 2009) and this bacterium seems to be well adapted to its hosts, presenting highly successful transmission rates (Burgdorfer et al. 1981, Saraiva et al. 2013).

Taking together, these observations suggest that this bacterium may be involved in cases of atypical SF cases and show the need for further studies to elucidate its real pathogenic potential. Although the R. amblyommii pathogenic status remains unclear, the present study brings new contribution to the understanding of its complex vector/host network.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To the vectors collection maintained at Oswaldo Cruz Institute, Collection of Apterous Arthropod Vectors of Community Health Importance, for tick specimens.

REFERENCES

- Aljanabi SM, Martinez I. Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high quality genomic DNA for PCR-based techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4692–4693. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves AS, Melo ALT, Amorim MV, Borges AMCM, Gaiva e Silva L, Martins TF, Labruna MB, Aguiar DM, Pacheco RC. Seroprevalence of Rickettsia spp in equids and molecular detection of Candidatus Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma cajennense sensu lato ticks from the Pantanal region of Mato Grosso, Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2014;51:1242–1247. doi: 10.1603/ME14042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apperson CS, Engber B, Nicholson WL, Mead DG, Engel J, Yabsley MJ, Dail K, Johnson J, Watson DW. Tick-borne diseases in North Carolina: is Rickettsia amblyommii a possible cause of rickettsiosis reported as Rocky Mountain spotted fever? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:597–606. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A, Little SE, Shaw E. Rickettsia amblyommii and R. montanensis infection in dogs following natural exposure to ticks. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:20–25. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beati L, Nava S, Burkman EJ, Barros-Battesti DM, Labruna MB, Guglielmone AA, Cáceres AG, Guzmán-Cornejo CM, León R, Durden LA, Faccini JL. Amblyomma cajennense (Fabricius, 1787) (Acari: Ixodidae), the Cayenne tick: phylogeography and evidence for allopatric speciation, Panama. 267BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez SE, Eremeeva ME, Karpathy SE, Samudio F, Zambrano ML, Zaldivar Y, Motta JA, Dasch GA. Detection and identification of rickettsial agents in ticks from domestic mammals in eastern Panama. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:856–861. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billeter SA, Blanton HL, Little SE, Levy MG, Breitschwerdt EB. Detection of Rickettsia amblyommii in association with a tick bite rash. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:607–610. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair PJ, Jiang J, Schoeler GB, Moron C, Anaya E, Cespedes M, Cruz C, Felices V, Guevara C, Mendoza L, Villaseca P, Sumner JW, Richards AL, Olson JG. Characterization of spotted fever group rickettsiae in flea and tick specimens from northern Peru. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4961–4967. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.4961-4967.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton LS, Walker DH, Bouyer DH. Rickettsiae and ehrlichiae within a city park: is the urban dweller at risk? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:168–170. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorfer W, Hayes SF, Thomas LA, Lancaster JL. A new spotted fever group Rickettsia from the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum. In: Rickettsiae and rickettsial diseases. Academic Press; New York: 1981. pp. 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Eremeeva ME, Karpathy SE, Levin ML, Caballero CM, Bermudez S, Dasch GA, Motta JÁ. Spotted fever rickettsiae, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma in ticks from peridomestic environments in Panama. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;2:12–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke FS, Gazeta GS, Souza ER, Ribeiro A, Marrelli MT, Schumaker TT. Rickettsia rickettsii, Rickettsia felis and Rickettsia sp. TwKM03 infecting Rhipicephalus sanguineus and Ctenocepha- lides felis collected from dogs in a Brazilian spotted fever focus in the state of Rio de Janeiro/Brazil. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;2:267–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedes E, Leite RC, Prata MCA, Pacheco RC, Walker DH, Labruna MB. Detection of Rickettsia rickettsii in the tick Amblyomma cajennense in a new Brazilian spotted fever-endemic area in the state of Minas Gerais. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:841–845. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762005000800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hun L, Troyo A, Taylor L, Barbieri AM, Labruna MB. First report of the isolation and molecular characterization of Ricket- tsia amblyommii and Rickettsia felis in Central America. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:1395–1397. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Yarina T, Miller MK, Stromdahl EY, Richards AL. Molecular detection of Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma americanum parasitizing humans. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:329–340. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labruna MB. Ecology of Rickettsia in South America. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1166:156–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labruna MB, Pacheco RC, Nava S, Brandão PE, Richtzenhain LJ, Guglielmone AA. Infection by Rickettsia bellii and Candidatus Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma neumanni ticks from Argentina. Microb Ecol. 2007;54:126–133. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labruna MB, Whitworth T, Bouyer DH, McBride JW. Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma ticks from the state of Rondônia, western Amazon, Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2004;41:1073–1081. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.6.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kakumanu M, Ponnusamy L, Vaughn M, Funkhouser S, Thornton H, Meshnick SR, Apperson CS. Prevalence of rickettsiales in ticks removed from the skin of outdoor workers in North Carolina. 607Parasit Vectors. 2014;7 doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0607-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merhej V, Angelakis E, Socolovschi C, Raoult D. Genotyping, evolution, and epidemiological findings of Rickettsia species. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;25:122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nava S, Beati L, Labruna MB, Cáceres AG, Mangold AJ, Guglielmone AA. Reassessment of the taxonomic status of Amblyomma cajennense (Fabricius, 1787) with the description of three new species, Amblyomma tonelliae n. sp., Amblyomma interandinum n. sp. and Amblyomma patinoi n. sp., and reinstatement of Amblyomma mixtum Koch, 1844, and Amblyomma sculptum Berlese, 1888 (Ixodida: Ixodidae) Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:252–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco RC, Horta MC, Pinter A, Moraes J, Filho, Martins TF, Nardi MS, Souza SS, Souza CE, Szabó MP, Richtzenhain LJ, Labruna MB. Survey of Rickettsia spp in the ticks Amblyomma cajennense and Amblyomma dubitatum in the state of São Paulo. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2009;42:351–353. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822009000300023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco RC, Moraes J, Filho, Guedes E, Silveira I, Richtzenhain LJ, Leite RC, Labruna MB. Rickettsial infections of dogs, horses, and ticks in Juiz de Fora, southeastern Brazil, and isolation of Rickettsia rickettsii from Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks. Med Vet Entomol. 2011;25:148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2010.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Comer JA, Zaki SR, Goldsmith CS, Goddard J, McLellan SL, Tamminga CL, Ohl CA. Rickettsia parkeri: a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:805–811. doi: 10.1086/381894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola P, Paddock CD, Raoult D. Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:719–756. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.719-756.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnery RL, Spruill CL, Plikaytis BD. Genotypic identification of rickettsiae and estimation of intraspecies sequence divergence for portions of two rickettsial genes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1576–1589. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1576-1589.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva DG, Nieri-Bastos FA, Horta MC, Soares HS, Nicola PA, Pereira LC, Labruna MB. Rickettsia amblyommii infecting Amblyomma auricularium ticks in Pernambuco, northeastern Brazil: isolation, transovarial transmission, and transstadial perpetuation. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:615–618. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2012.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares HS, Barbieri AR, Martins TF, Minervino AH, Lima JT, Marcili A, Gennari SM, Labruna MB. Ticks and rickettsial infection in the wildlife of two regions of the Brazilian Amazon. Exp Appl Acarol. 2015;65:125–140. doi: 10.1007/s10493-014-9851-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JP, Tanner WB, Rawlings JA, Buck J, Elliott LB, Dewlett HJ, Taylor B, Betz TG. Serological evidence of subclinical Rocky Mountain spotted fever infections in Texas. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:367–369. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yevich SJ, Sánchez JL, Fraites RF, Rives CC, Dawson JE, Uhaa IJ, Johnson BJ, Fishbein DB. Seroepidemiology of infections due to spotted fever group rickettsiae and Ehrlichia species in military personnel exposed in areas of the United States where such infections are endemic. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1266–1273. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanettii AS, Pornwiroon W, Kearney MT, Macaluso KR. Characterization of rickettsial infection in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:267–275. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[267:coriia]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]